1. Introduction

Engagement in music is intrinsically pleasurable and associated with positive health outcomes throughout the lifespan (see [

1] for a review). Musical engagement can help regulate and express emotions (e.g., [

2]), reduce stress-related symptoms (e.g., [

3]), and promote social connection and prosocialness (e.g., [

4,

5]), among many other benefits. As music is cost-effective, easily accessible, and very personalizable, there has been a rise in music-based interventions and music therapy for various health and neurological conditions, such as stroke, dementia, and Parkinson's disease (see [

6] for a review). A mechanistic understanding of how music engages regions and networks throughout the brain is necessary in order to fully leverage the therapeutic potential of music for brain rehabilitation and overall well-being.

Music listening involves numerous complex neurobiological mechanisms that engage multiple brain regions, including those involved in the auditory, reward, and motor networks. Musical stimuli, including monophonic and harmonized auditory sequences as well as instrumental and vocal music, activate various auditory regions, such as the superior temporal gyri (STG) and Heschl's gyri (HG) [

7,

8]. As motor control plays a crucial role in music production (see [

9,

10] for a review), music involves a tight coupling between the auditory and motor networks. Listening to music and attuning to its rhythm and beat will spontaneously activate multiple regions of the motor network, including the premotor cortex, supplementary motor area (SMA), and basal ganglia [

11,

12]. Through the process of neuronal entrainment, it couples the motor and auditory networks with shared rhythmic oscillatory activity resembling the rhythm of the attuned musical stimulus [

13,

14,

15].

Auditory-motor coupling is strongest when listening to music that inspires movement [

16,

17]. Music that is groovy (i.e. that is perceived as having the pleasurable urge to move) elicits increased activity in the motor network, including the putamen and SMA, which are involved in movement and beat perception, as well as the prefrontal and parietal cortex, which are involved in movement initiation and preparation [

18]. Similarly, listening to reggaeton, a genre known for its groovy dembow rhythmic patterns, elicited the highest auditory-motor activation compared to classical, electronic, and folk music [

19]. Thus, motor system activity reflects the subjective feeling of grooviness and the simulation of covert body movement when listening to rhythms and beats [

20].

Listening to enjoyable music generally stimulates and enhances the connectivity of the auditory-reward network, irrespective of a person's musical expertise [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Changes in functional connectivity (FC) induced by TMS between the NAcc and both the frontal and auditory cortices predicted the degree of modulation in hedonic responses to music, suggesting that the NAcc plays a crucial role in music-induced reward and motivation [

26]. Increased FC between the NAcc and the auditory cortices, amygdala, and ventromedial prefrontal regions predicted how rewarding a piece of music would be [

27]. Individuals with music anhedonia (i.e., individuals who do not find music pleasurable) exhibited lower activity in the NAcc and reduced FC between the right auditory cortex and the ventral striatum, including the NAcc [

28]. Additionally, white matter connectivity between the STG and areas were associated with emotional and social processing in the insula and medial prefrontal cortex to individual differences in musical reward sensitivity [

29]. Even in the absence of music, these two networks are intrinsically connected, and this between-network connectivity is preserved in healthy older adults and those with mild cognitive impairment ([

30]; but also see [

31]).

While we recognize the roles of the auditory, reward, and motor networks during music listening, much remains unknown about how these three networks interact with each other. The few studies that have examined FC during music listening have predominantly focused on the connectivity between pairs of networks rather than all three simultaneously. By investigating the interactions among all three networks, we can gain a better understanding of the overall organization of the brain while processing music, particularly how the motor regions contribute to both the pleasurable nature of music and the auditory-reward circuitry.

Moreover, music is experienced in various contexts—sometimes as the primary focus, sometimes accompanying other activities. Understanding network connectivity in these different contexts is essential for understanding the neural basis of music listening. Prior work in EEG has observed differences in the onset and amplitude of Event-Related Potential (ERP) components between foreground and background music listening [

32], suggesting that attention influenced the underlying neural processing of complex musical stimuli. One study [

33] found differences in event-related synchronization between passive and active listening conditions, but only for a well-known pop song and not for an unfamiliar classical music piece. Using behavioral and neuroimaging methods, another study [

34] investigated how background music with fast and slow amplitude modulations affected sustained attention, measured by performance on the Sustained Attention Response Task (SART). Participants who listened to music with fast amplitude modulations first outperformed those who listened to music with slow amplitude modulations and pink noise. Results suggest a complex relationship between music, attention, and the brain.

By characterizing functional connectivity within and between brain networks under conditions of foreground and background music listening, the current work seeks to uncover the interactions across auditory, motor, and reward networks across a few different task settings under which music is commonly experienced. In one setting, participants were listening to musical excerpts (in the foreground) and evaluating them for liking and familiarity. In another setting, participants were completing attention and working memory tasks while music was playing (in the background). In both settings, participants also completed resting state functional MRI scans in which there was no task; these resting state scans served as a no-music control across all participants.

In this present study, we conduct a preregistered secondary analysis of fMRI data for FC under different music listening contexts relative to resting state data obtained from the same participants. We aim to identify FC patterns of the auditory, reward, and motor networks underlying music listening. As limited fMRI studies have explicitly examined variations in functional connectivity during attentive foreground versus inattentive background music listening, another goal of this current work is to identify potential FC differences in the three networks of interest that could be associated with foreground versus background listening. We hypothesize that there will be i) increased FC within and between reward-associated brain regions and auditory and motor networks during music listening compared to rest and ii) different FC patterns between the three networks across different music listening contexts. This secondary analysis examines existing datasets from two independent studies involving music listening. While this prevents controlled comparison of attention effects, it provides ecological validity in examining music processing across naturalistic contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We analyzed two samples of Northeastern University students from two separate studies. The first sample (foreground music group) consisted of N = 39 young adults aged 18 to 25 (M = 20.18 years, SD = 3.09 years; 29 identified as female, 9 as male, and 1 as non-binary). We excluded one participant due to extremely high mean motion values. The second sample (background music group) consisted of N = 39 young adults aged 18 to 25 (M = 19.21, SD = 1.88; 29 identified as female, 7 as male, and 3 as non-binary). We excluded one participant due to extremely high maximum global signal change values. All participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) were 18 years of age or older, (2) had normal hearing, and (3) passed an MRI safety screening. They were compensated with either payment or course credit. Both studies were approved by the Northeastern University institutional review board and preregistered at

https://osf.io/d6j7e/?view_only=a17c8258fa384b92b98606732042026f.

2.2. Procedures

Study 1: Foreground Music Group

Participants took part in a music-listening fMRI task, where they listened to 20-second musical clips. These clips included participant-selected music (6 out of 24 stimuli), well-known songs from various genres chosen by the researchers (10 out of 24 stimuli), and music based on a novel scale (8 out of 24 stimuli). The order of the clips was randomized. After listening, participants had two seconds to rate each clip based on how much they liked and were familiar with it using a 4-point scale (for more details, see [

21]).

They also completed a face-name association memory test [

35] without any music. They learned the faces and names of 30 individuals (16 females and 14 males) and were then tested on 14 of these individuals (7 females and 7 males). Each face-name pair was shown once for 4.75 seconds, followed by a 1.9-second central fixation crosshair, except for one female and one male, whose pairs were presented four times across the four trial blocks. During the testing phase, participants saw one of the 30 previously-presented individuals' faces alongside two names: the correct associated name and a distractor name linked to another face from the learning phase. The placement of the correct and distractor names was randomized across trials.

Study 2: Background Music Group

Participants completed the 2-Back Working Memory (WM) and Sustained Attention to Response tasks (SART) while listening to either theta-frequency amplitude-modulated or unmodulated background music. Each participant was randomly assigned a song list with 3 modulated and 3 unmodulated songs for each task, with a total of 6 modulated songs and 6 unmodulated songs over the course of both tasks. Each song clip lasted 60 seconds, with task stimuli presented at the beat rate of each song. Each trial lasted between 975ms to 1250ms depending on the song’s inter-onset interval. Task order (i.e., WM or SART first) and type of music (i.e., modulated or unmodulated music first) were counterbalanced.

In the WM task, participants were presented with a sequence of 15 letters (from A to T) one at a time, and their task was to indicate with a button press whether the current letter was the same as the letter presented two trials earlier. For SART, participants saw a sequence of numbers (0 through 9), and their task was to click the button for every number except for a specified target number (3).

2.3. fMRI Data Acquisition and Analysis

All images were acquired using a Siemens Magnetom 3T MR scanner with a 64-channel head coil at the Northeastern University Biomedical Imaging Center. For the foreground music group, task fMRI data used continuous acquisition with a repetition time (TR) of 475ms. Specifically, 672 and 196 volumes were collected for the learning and testing phase of the face-name task, for a total acquisition time of 5 min 26 sec and 1 min 40 sec, respectively. For the music-listening task, 1440 volumes were collected, for a total acquisition time of 11 min 31 sec. Forty-eight interleaved transverse slices (slice thickness = 3mm, phase encoding [PE] direction = anterior to posterior) were acquired as multiband gradient echoplanar images (EPI) functional volumes covering the whole brain (field of view = 240mm, resolution = 3mm isotropic, TR = 475ms, time echo [TE] = 30ms, flip angle = 40° [face-name tasks]/60° [music-listening task]). The resting-state scan followed the same parameters (flip angle = 60°) and included 947 continuous scans, for a total scan length of 7 min 37 sec. Structural images were acquired using a high-resolution magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence, with one T1 image acquired every 2500 ms, for a total task time of 8 min 22 sec. Sagittal slices (0.8 mm thick, PE direction = anterior to posterior) were acquired covering the whole brain (field of view = 256mm, resolution = 0.8mm isotropic, TR = 2500 ms, TE 1 = 1.81 ms, TE 2 = 3.6 ms, TE 3 = 5.39 ms, TE 4 = 7.18 ms, flip angle = 8°, IPAT mode = GRAPPA 2×; as described in [

21]. Spin-echo volume pairs were also acquired matching the BOLD EPI slice prescription and resolution in opposing PE directions (anterior to posterior and posterior to anterior) for susceptibility distortion correction (TR = 8290 ms, TE = 69.0 ms, acquisition time = 33 s each).

For the background music group, task fMRI data used continuous acquisition for 768 volumes per task (1536 volumes in total), with the same TR (475ms), for an acquisition time of 6 min 12 sec per task (12 min 24 sec in total). Forty-eight interleaved transverse slices (slice thickness = 3mm, PE direction = anterior to posterior, multiband acceleration factor = 8) were acquired as EPI functional volumes covering the whole brain (field of view = 240mm, resolution = 3mm isotropic, TR = 475ms, TE = 30ms, flip angle = 41°). The resting-state scan followed the same parameters and included 947 continuous scans, for a total scan length of 7 min 37 sec. Structural images were also acquired using a high-resolution MPRAGE sequence, with one T1 image acquired every 2500 ms, for a total task time of 8 min 22 sec. Sagittal slices (0.8 mm thick, PE direction = anterior to posterior) were acquired covering the whole brain (field of view = 256 mm, resolution = 0.8 mm isotropic, 208 slices, TR = 2500 ms, TE 1 = 1.81 ms, TE 2 = 3.6 ms, TE 3 = 5.39 ms, TE 4 = 7.18 ms, flip angle = 8°, IPAT mode = GRAPPA 2×). Lastly, spin-echo volume pairs were acquired matching the BOLD EPI slice prescription and resolution in opposing PE directions (anterior to posterior and posterior to anterior) for susceptibility distortion correction (TR = 8290 ms, TE = 69.0 ms, acquisition time = 33 s each).

All fMRI data were preprocessed using FMRIPrep [

36] and the CONN Toolbox [

37]. Functional and anatomical data were preprocessed using a modular preprocessing pipeline [

38], including functional realignment and unwarp with correction of susceptibility distortion interactions, functional centering, functional slice time correction, functional outlier detection using the ARtifact detection Tools (ART) software package, functional direct segmentation and normalization to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template, structural centering, and structural segmentation and normalization to MNI template, and functional smoothing using spatial convolution with a Gaussian kernel of 8 mm full width half maximum [

39]. Functional data was further denoised using a standard pipeline [

38], including the regression of potential confounding effects characterized by white matter and CSF timeseries (10 CompCor noise components each), motion parameters and their derivatives (12 factors), outlier scans and their derivatives (below 14 factors), session and task effects and their derivatives (2 factors each), and linear trends within each functional run (2 factors), followed by high-pass frequency filtering of the BOLD timeseries above 0.008 Hz.

2.4. ROI-to-ROI Analyses

Using the CONN Toolbox, ROI-to-ROI connectivity matrices were estimated characterizing the patterns of functional connectivity with 46 ROIs of the auditory, reward, and motor networks. Specifically, we included 18 auditory ROIs (all subdivisions of bilateral superior temporal gyri [STG], middle temporal gyrus [MTG], inferior temporal gyri [ITG], and Heschl’s gyri [HG]) and 18 reward ROIs (anterior cingulate [ACC], posterior cingulate [PCC], bilateral insular cortex [IC], frontal orbital cortex [FOrb], caudate, putamen, pallidum, hippocampus, amygdala, and NAcc), as defined by [

30]. We chose 10 ROIs for the motor network, including bilateral precentral (preCG) and postcentral gyri (postCG), SMA, and superior and middle frontal gyri (SFG and MFG). For further exploratory analyses, we also included 32 asymmetrical cerebellar region parcellation ROIs from [

40].

We contrasted each task with rest and between each other (Foreground music group: Music-listening>Rest, Music-listening>Face-name task, Face-name>Rest; Background music group: SART>Rest, WM>Rest, SART>WM). To examine potential effects of using modulated versus unmodulated background music on functional connectivity, we also compared the two background music tasks within and between each other (i.e., SARTmod>SARTunmod, WMmod>WMunmod, SARTmod>WMmod, SARTunmod>WMunmod, SARTmod>WMunmod, SARTunmod>WMmod) in an exploratory manner. All these main effect contrast analyses included participant age, gender, and musical reward sensitivity measured by the Barcelona Musical Reward Questionnaire (BMRQ) as covariates of no interest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 (False Discovery Rate [FDR] corrected), and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network-Based Statistics [NBS]).

2.5. Seed-Based Connectivity Analyses

We also conducted seed-based connectivity analyses using CONN, using the above defined task versus rest contrasts and auditory, reward, and motor network ROIs as seeds. Specifically, we examined the STG and HG for the auditory network, the NAcc and IC for the reward network, and all 10 ROIs for the motor network. Just like the ROI-to-ROI analyses described above, we ruled out confounding effects of within-group age, gender, and musical reward sensitivity by including them as covariates of no interest. All voxel and cluster thresholds were set at p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

2.6. Graph Theory Analyses

Additionally, to assess how music listening modulates the topological organization of functional brain networks, we looked at within- and between-task graph theory measures for all our chosen ROIs, including

degree (i.e., the number of connections from a node),

clustering coefficient (i.e., the cliquishness of a node, or the number of shared neighboring nodes each node has),

betweenness centrality (i.e., the number of shortest paths that contains a given node), and local (i.e., the average inverse shortest path length of node neighborhoods) and

global efficiency (i.e., the average inverse shortest path length in the network) [

41]. We selected adjacency matrix thresholds of cost = 0.15 for between-task measures and correlation coefficient = 0.45 for within-task measures.

3. Results

3.1. ROI-to-ROI Analyses

We first looked at within-task functional connectivity for both resting states and all tasks (i.e., music listening task, SART and WM combined, and face-name task) to ensure that our chosen ROIs for each network are intrinsically connected. As expected, most ROIs were positively connected to other within-network ROIs (see

Supplementary Materials 1 for all within-task ROI-to-ROI connectivity matrices).

Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

First looking at the contrast between the music-listening task and rest, we found similar patterns of positive correlations between bilateral STG and HG. However, bilateral MTG and ITG were mostly negatively correlated to other auditory ROIs. Bilateral IC again was negatively correlated with HG but positively correlated with bilateral anterior and left posterior MTG. ACC was negatively correlated with bilateral HG, and PCC was negatively correlated with left anterior STG, but they were both positively correlated with MTG and ITG. Bilateral amygdala was positively correlated with anterior and posterior STG and bilateral HG and negatively correlated with temporooccipital ITG. Bilateral hippocampus was positively correlated with bilateral HG and negatively correlated with temporooccipital ITG. Bilateral putamen was negatively correlated with bilateral posterior STG. Bilateral FOrb was positively correlated with STG, MTG, and left HG while negatively correlated with anterior and temporooccipital ITG. Most motor ROIs were negatively correlated with auditory and reward ROIs, except for: bilateral precentral gyri with temporooccipital ITG, bilateral midFG with left anterior ITG, bilateral SFG with left IC, bilateral precentral gyri with ACC and PCC, and right postcentral gyrus with PCC. All ROI-to-ROI results are displayed in

Figure 1.

Then, we contrasted the music-listening task with the face-name task. Despite having fewer significant ROI-to-ROI connections, there is a similar trend of enhanced FC within the auditory network and reduced FC outside of the auditory network (particularly the auditory and motor networks with no positive correlations), as well as reduced reward-motor FC during the music listening task compared to the face-name task. One prominent difference is the bilateral hippocampus being positively correlated with the right posterior STG, MTG, and right HG. The left hippocampus was also positively correlated with the right midFG. All ROI-to-ROI results are displayed in

Figure 2.

Study 2: Background Listening Group

We first contrasted SART with WM but found no significant differences, so we decided to statistically treat them as one task (i.e., by taking the average of both SART and WM) to contrast with rest. We found statistically positive T-values of bivariate correlations within all regions of the auditory network, including the bilateral anterior and posterior STG, MTG, and HG, except for the ITG ROIs. Bilateral STG and HC were negatively correlated to bilateral IC. MTG was negatively correlated to the left NAcc and caudate but positively correlated to the PCC, ACC, and bilateral IC. ITG ROIs were negatively correlated to the hippocampus and caudate but positively correlated to the ACC and PCC. The temporooccipital ITG were also positively correlated to the pallidum, putamen, caudate, and FOrb. Bilateral STG and HG were negatively correlated with bilateral SMA. The bilateral precentral and postcentral gyri were also negatively correlated with STG and MTG. The left SFG and midFG were positively correlated with bilateral HG, posterior MTG, and temporooccipital ITG. The right SFG was negatively correlated with anterior MTG and positively correlated with temporooccipital ITG, and the right midFG was negatively correlated with left HG and right posterior ITG. The reward ROIs, especially the NAcc and caudate, were also mostly positively correlated to the motor ROIs. There were no significant differences between the two modulation conditions. All ROI-to-ROI results are displayed in

Figure 3.

In all, these findings suggest that when individuals listen to background music while concurrently completing cognitive tasks, the auditory network had higher within-network connectivity and reduced out-of-network connectivity (auditory-reward and auditory-motor) compared to rest.

3.2. Seed-Based Connectivity Analyses

Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

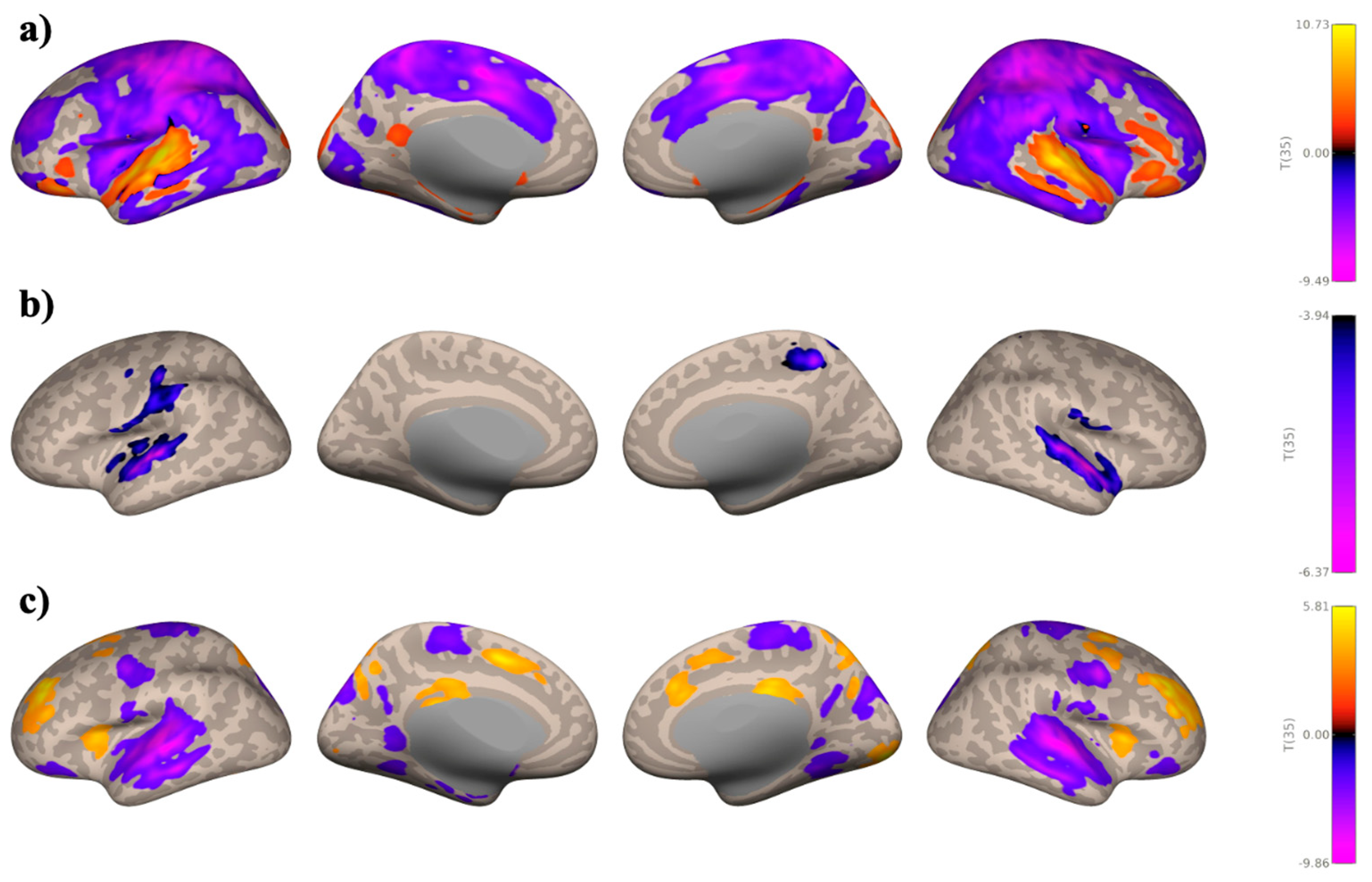

There were similar seed-based connectivity trends in the Music Listening Task > Rest (

Figure 4) and Music Listening Task > Face-name Task (

Figure 5) contrasts. Seed-based connectivity patterns from the auditory network are shown in

Figure 4a and

Figure 5a below. Large negative clusters were found within the motor network, including the precentral and postcentral gyri and midFG, followed by the lateral occipital cortex, precuneous cortex, ACC, PCC, and smaller negative clusters within the frontal pole. Large positive clusters were seen in the lingual gyrus, planum temporale, FOrb, STG, and HG. There were smaller and fewer clusters for the reward network overall, with negative clusters predominantly in the temporal pole, planum temporale, planum polare, anterior STG, HG, and supramarginal gyrus. There were also negative clusters in the postcentral gyrus for the Music Listening Task > Face-name Task contrast. Very small positive clusters were found in the lateral occipital cortex and anterior MTG, but only for the Music Listening Task > Rest contrast (see

Figure 4b and

Figure 5b). As for the motor network, there were large positive clusters in the precuneous cortex, superior parietal lobule, lateral occipital cortex, postcentral gyrus, SFG, ACC, and paracingulate gyrus. Other motor areas had smaller positive clusters, such as the midFG, precentral gyrus, and SMA. Negative clusters were found in the MTG, temporal pole, planum temporale, anterior STG, HG, central opercular cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala (see

Figure 4c and

Figure 5c).

Study 2: Background Listening Group

Seed-based connectivity patterns from the auditory network are shown in

Figure 6a below for the SART and WM combined > Rest contrast. Overall, there was more connectivity within auditory regions including the STG, MTG, and HG, and less connectivity with reward and motor regions including the IC, precentral and postcentral gyri, and SMA. Very small significant positive clusters were found within the SFG and midFG. As for the reward network, we found large positive clusters covering the superior and inferior lateral occipital cortex and SFG, and slightly smaller clusters in the ITG and MTG. Negative clusters were found in the IC, central opercular cortex, frontal and temporal pole, planum temporale, and putamen (see

Figure 6b below). Lastly, for the motor network, there were large positive clusters in the lateral occipital cortex, precuneous cortex, supramarginal gyrus, and occipital fusiform gyrus. There were smaller positive clusters within the motor and reward networks. Most negative clusters were found in the auditory network, including the STG, MTG, and HG (see

Figure 6c below).

3.3. Graph Theory Analyses

Lastly, we computed graph theory measures of degree, clustering coefficient, betweenness centrality, local efficiency, and global efficiency. We only reported between-task contrasts due to length constraints, but within-task graph theory statistics are available in

Supplementary Materials 2.

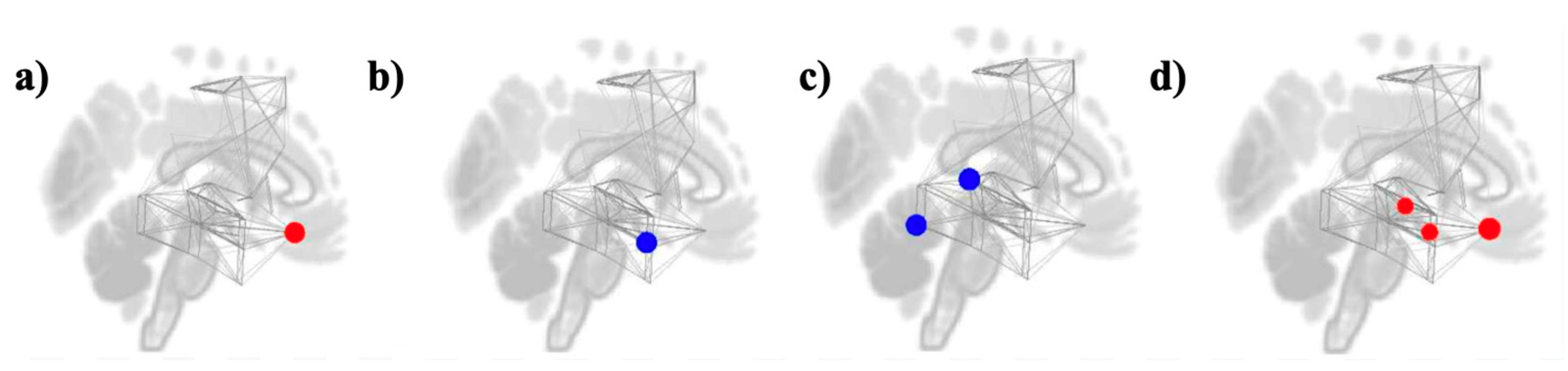

Study 1: Foreground Listening Group

For the Music Listening Task > Rest contrast, we only see a significant increase in node degree for the right FOrb (see

Figure 7a). The left pSTG and left temporooccipital ITG had significant decreases in betweenness centrality (see

Figure 7b). Clustering coefficient was significantly decreased in the left aMTG (see

Figure 7c). Lastly, global efficiency was significantly increased in the right FOrb, right amygdala, right pSTG, and left amygdala (see

Figure 7d). Results are shown in

Table 1 below.

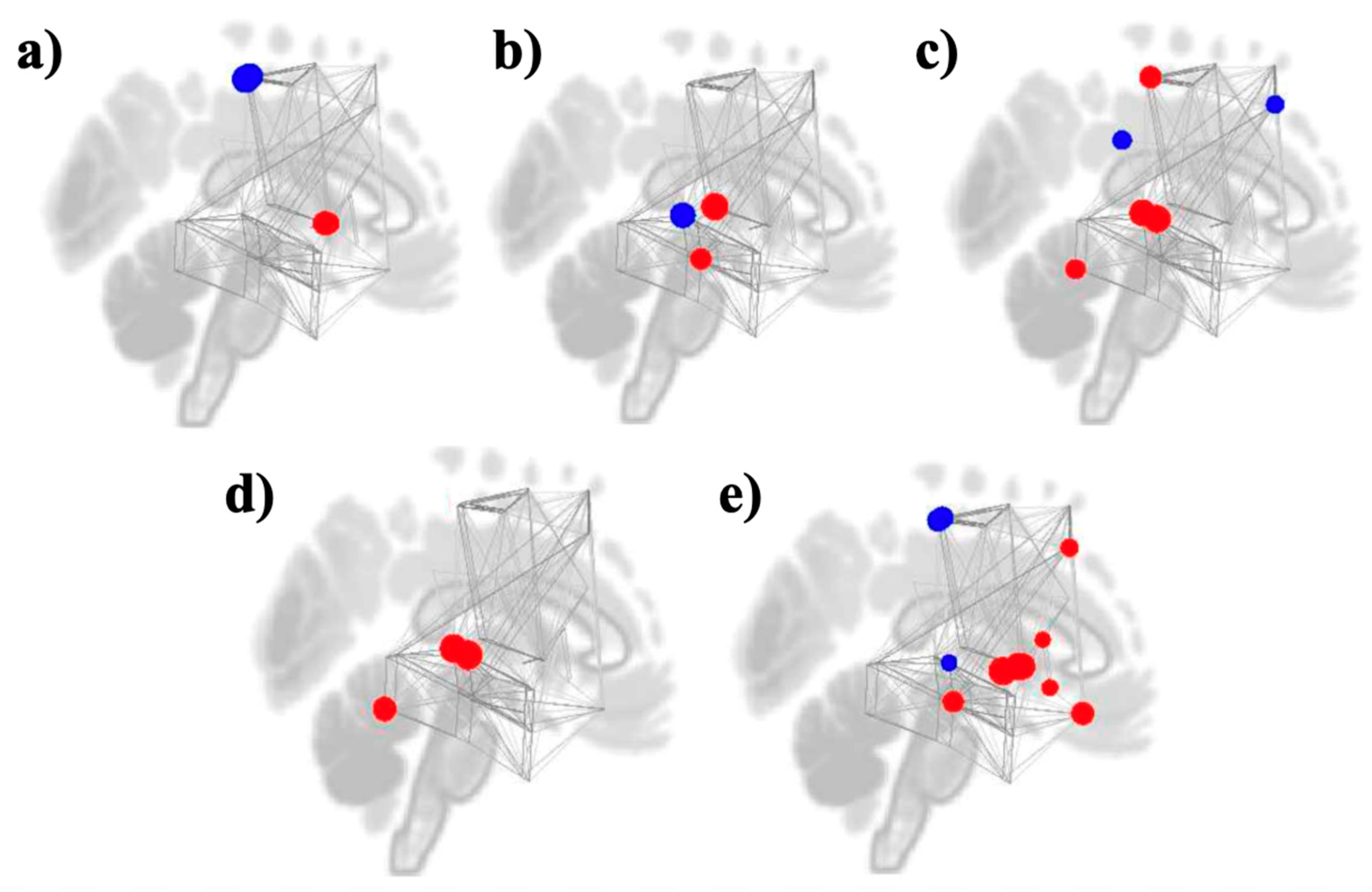

As for the Music Listening Task > Face-name Task contrast, significant increases in node degree were seen in the bilateral putamen, while decreases in degree were seen in the bilateral postCG (see

Figure 8a). Betweenness centrality was increased in the right HG and right pMTG and reduced in the left pSTG (see

Figure 8b). Clustering coefficient was increased in mostly auditory ROIs (bilateral pSTG and right temporooccipital ITG) and the right postCG, but reduced in the PCC and right midFG (see

Figure 8c). Local efficiency was increased in the bilateral pSTG and left temporooccipital ITG (see

Figure 8d). There was an increase in global efficiency for reward ROIs (left NAcc, left caudate, and bilateral putamen, pallidum, and FOrb) as well as the right pMTG and left midFG, but a decrease was seen in the bilateral postCG and right pSTG (see

Figure 8e). Results are shown in

Table 2 below.

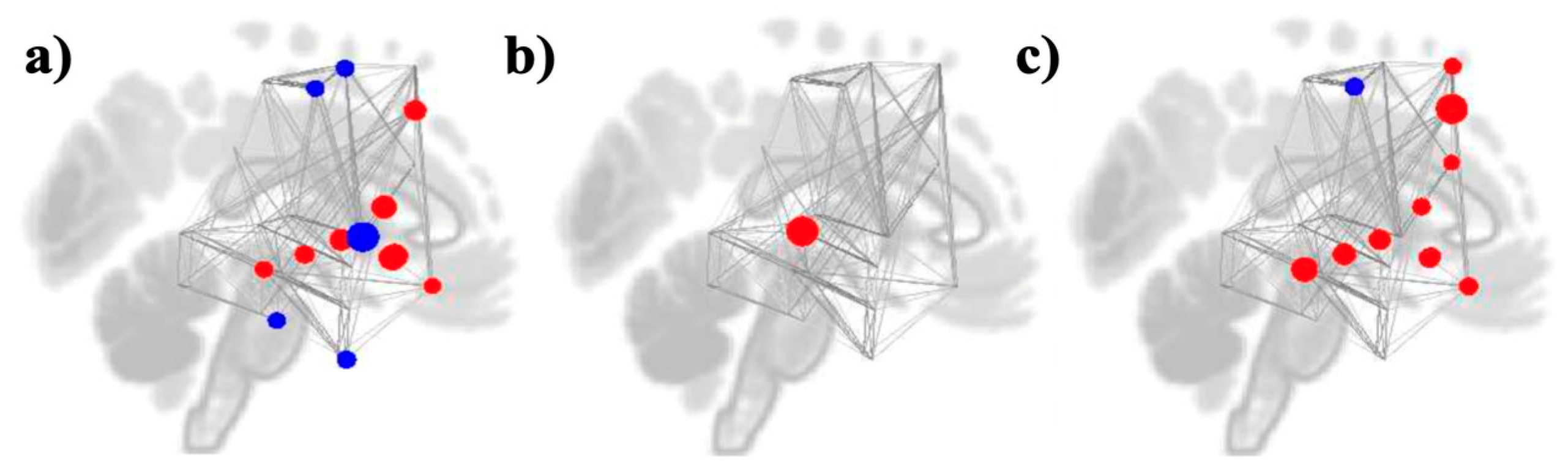

Study 2: Background Listening Group

Compared to rest, cognitive task performance (SART and WM) with music was associated with significant decreases in node degree in several regions within the reward and auditory networks. Notable reductions were observed in the right IC, left IC, and left aITG. Additional decreases were found in the left SMA, left PreCG, and right pITG. However, several reward ROIs showed significant increases in degree during music listening. These included the left NAcc, right NAcc, left caudate, right pallidum, and left FOrb. The left midFG, right pSTG, and left pMTG also showed significant increases in degree (see

Figure 9a).

Clustering coefficient and local efficiency were significantly increased in the right pSTG during music listening relative to rest. No other regions showed significant changes (see

Figure 9b). Significant increases were also observed for global efficiency. Specifically, the left midFG, right midFG, and left SFG for the motor network; the left pMTG and right pSTG for the auditory network; and the right pallidum, left NAcc, left FOrb, left caudate, right NAcc, and ACC for the reward network. Only one ROI, the left preCG, saw decreases in global efficiency (see

Figure 9c). Results are shown in

Table 3 below.

4. Discussion

We characterized functional connectivity patterns among auditory, motor, and reward networks during music engagement in two ecological contexts: music listening during cognitive task performance and focused music listening. While both contexts revealed enhanced within-auditory network connectivity during music processing, they showed distinct patterns of between-network interactions that likely reflect the combined influence of task demands, cognitive load, motor requirements, and music processing itself. These findings provide novel insights into the tripartite interaction of these networks during music engagement and demonstrate how different listening contexts shape neural organization.

Both foreground and background listening contexts showed robust enhancement of within-auditory network connectivity compared to rest, suggesting that this may be a fundamental characteristic of music processing regardless of context. However, the between-network patterns diverged substantially between contexts. During concurrent cognitive task performance with background music, we observed preserved reward-motor coupling alongside reduced auditory connections to both other networks. During focused music listening, we found widespread negative correlations between motor regions and both auditory and reward networks. These patterns represent the first systematic examination of all three networks simultaneously during music engagement, revealing complex context-dependent reorganizations that were not captured by previous studies that featured pairwise networks.

4.1. Music Enhances Intrinsic Auditory Network Connectivity

The enhanced within-auditory network connectivity observed across both contexts aligns with increased processing demands for complex musical stimuli, extending previous findings [

7,

8]. This consistent finding suggests that internal auditory network coherence is a core feature of music processing. However, the between-network connectivity patterns differed markedly between contexts. During cognitive task performance with music, the auditory network showed selective decoupling from motor and reward networks, potentially reflecting efficient parallel processing that minimizes interference with concurrent task demands.

The differential connectivity patterns between MTG/ITG regions and other auditory areas during focused listening suggest hierarchical processing differences when music is the primary stimulus. These regions showed negative correlations with primary auditory areas, potentially reflecting specialized processing streams for different musical features or top-down modulation based on the listening context.

4.2. Context-Specific Motor and Reward Network Patterns During Music Listening

Our findings revealed predominantly negative motor-auditory and motor-reward correlations, particularly during focused music listening. This pattern appears contradictory to literature demonstrating motor activation during music listening [

18,

42]. However, this apparent contradiction likely reflects the specific experimental context where participants remained still during scanning. The observed patterns may represent active motor suppression rather than the absence of motor engagement with music [

43].

During cognitive task performance with background music, motor suppression was more selective, primarily affecting the SMA and precentral gyri while preserving some motor-reward coupling. This preserved coupling might support implicit rhythm processing while maintaining task performance. These context-specific patterns highlight how experimental constraints and concurrent task demands fundamentally shape motor network involvement during music processing.

4.3. Network Analyses Support Reward System Integration

Graph theory analyses revealed that reward regions demonstrated hub-like properties during music engagement, particularly during concurrent task performance. The increased degree, global efficiency, and betweenness centrality of regions like the NAcc, caudate, and pallidum together suggest that these areas serve as integration points during music processing. This aligns with previous findings linking NAcc connectivity to musical pleasure [

26,

27]. During focused music listening, the selective enhancement of amygdala and frontal orbital cortex connectivity indicates that different reward system components may be engaged depending on the listening context. The bilateral amygdala has positive correlations with auditory regions during focused listening, likely supporting its role in processing and/or evaluating the emotional content of music [

23].

The distinct connectivity patterns between contexts likely reflect a combination of attentional allocation, cognitive load, motor suppression requirements, and task-specific processing demands. During cognitive task performance with music, the brain must balance multiple processing streams, potentially explaining the preserved reward-motor coupling that might facilitate dual-task coordination. The network segregation observed during focused listening could optimize music-specific processing when cognitive resources are not divided. These findings extend beyond simple attention effects, revealing how the broader cognitive and behavioral context shapes music processing networks. The differences between contexts cannot be attributed to attention alone but rather represent the complex interplay of multiple cognitive and sensory processes operating simultaneously.

4.4. Rethinking the Role of Auditory Connectivity in Neurorehabilitation

Our findings have implications for understanding how music functions in various real-world contexts. The preserved motor-reward coupling during cognitive task performance suggests that background music might support certain types of activities through implicit motivational and rhythmic processes. However, the reduced cross-network connectivity in this context also suggests potential limitations in music's emotional or aesthetic impact when attention is divided.

For therapeutic applications, these context-dependent patterns suggest that intervention design should consider not just musical content but also the cognitive and behavioral context of delivery. Music presented during movement therapy might engage different neural mechanisms than music used for focused listening in emotional regulation interventions. Future reports of music-based intervention research should include the setting, delivery method, and intervention strategy [

44]. For example, music presented during movement therapy [

45] might engage different neural mechanisms than music used for focused listening in attention interventions [

34].

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

As a secondary analysis of existing datasets, the current manuscript alone cannot definitively isolate specific factors driving the observed differences between contexts, as the contexts differed not only in attentional focus but also in concurrent cognitive demands, task requirements, and potentially participant engagement.

Future research should systematically manipulate individual factors—attention, cognitive load, motor requirements, and musical features—within subjects to isolate their specific contributions to network connectivity. Studies could parametrically vary cognitive load while keeping music constant or manipulate musical features while maintaining consistent task demands. Understanding how individual factors such as age, clinical status, musical training, reward sensitivity, and cognitive capacity influence these context-dependent patterns would also be crucial for personalized applications.

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates that music engagement involves complex reorganization of auditory, motor, and reward networks, with patterns varying substantially across listening contexts. While enhanced within-auditory connectivity appears to be a consistent feature of music processing, between-network interactions depend on the broader cognitive and behavioral context. These findings highlight the importance of considering ecological context when studying music processing and designing music-based interventions. Rather than revealing simple attention effects, our results demonstrate that music's neural basis is fundamentally shaped by the complex interplay of concurrent cognitive demands, motor requirements, and listening goals. This context-dependent flexibility may underlie music's versatility as a tool for diverse applications from cognitive enhancement to emotional regulation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Supplementary 1: Within-Task ROI-to-ROI Connectivity Matrices, Supplementary 2: Within-Task Graph Theory Statistics

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, K.H. and P.L.; methodology, K.H. and J.W.; software, K.H.; validation, B.K., C.P. and J.W.; formal analysis, K.H.; investigation, K.H.; resources, P.L.; data curation, J.W. and B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H.; writing—review and editing, P.L.; visualization, K.H.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, C.P.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH R01AG078376, NIH R21AG075232, NSF-BCS 2240330 and NSF-CAREER 1945436, and Sony Faculty Innovation Award to PL.”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northeastern University (IRB#: 18-12-13 approved since May 2020 and IRB#: 19-03-20 approved since March 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alfonso Nieto-Castanon for advice through the CONN fMRI workshop, which enabled this secondary analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dingle, G.A.; Sharman, L.S.; Bauer, Z.; Beckman, E.; Broughton, M.; Bunzli, E.; Davidson, R.; Draper, G.; Fairley, S.; Farrell, C.; et al. How do music activities affect health and well-being? A scoping review of studies examining Psychosocial Mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, T.; Roy, A.R.K.; Welker, K.M. Music as an emotion regulation strategy: An examination of genres of music and their roles in emotion regulation. Psychology of Music 2017, 47, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, M.V.; La Marca, R.; Brönnimann, R.; Finkel, L.; Ehlert, U.; Nater, U.M. The effect of music on the Human Stress Response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarr, B.; Launay, J.; Dunbar, R.I.M. Silent disco: Dancing in synchrony leads to elevated pain thresholds and social closeness. EVOLUTION AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR 2016, 37, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Mason-Bertrand, A.; Fancourt, D.; Baxter, L.; Williamon, A. How participatory music engagement supports mental well-being: A meta-ethnography. Qualitative Health Research 2020, 30, 1924–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvonen, A.J.; Särkämö, T.; Leo, V.; Tervaniemi, M.; Altenmüller, E.; Soinila, S. Music-based interventions in neurological rehabilitation. The Lancet Neurology 2017, 16, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Perry, D.W.; Beckett, C.A.; Westbury, C.F.; Evans, A.C. Functional anatomy of musical processing in listeners with absolute pitch and relative pitch. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 3172–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Armony, J.L. Singing in the brain: Neural representation of music and voice as revealed by fmri. Human Brain Mapping 2018, 39, 4913–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Chen, J.L.; Penhune, V.B. When the brain plays music: Auditory–motor interactions in music perception and production. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2007, 8, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Florian, I.A.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Bratu, B.G.; Glavan, L.A.; Bordeianu, A.; Dumitrascu, D.I.; Ciurea, A.V. Cognitive Crescendo: How Music Shapes the Brain's Structure and Function. Brain sciences 2023, 13, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, J.A.; Brett, M. Rhythm and beat perception in motor areas of the brain. Journal of cognitive neuroscience 2007, 19, 893–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.D.; Iversen, J.R. The evolutionary neuroscience of musical beat perception: The Action Simulation for Auditory Prediction (ASAP) hypothesis. Frontiers in systems neuroscience 2014, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, T.; Ross, B.; Trainor, L.J. Beta-Band Oscillations Represent Auditory Beat and Its Metrical Hierarchy in Perception and Imagery. The Journal of neuroscience : The official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2015, 35, 15187–15198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-H.Z.; Creel, S.C.; Iversen, J.R. How do you feel the rhythm: Dynamic motor-auditory interactions are involved in the imagination of hierarchical timing. The Journal of Neuroscience 2021, 42, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, E.E.; Kim, J.C.; Demos, A.P.; Roman, I.R.; Tichko, P.; Palmer, C.; Large, E.W. Musical neurodynamics. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2025, 26, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janata, P.; Tomic, S.T.; Haberman, J.M. Sensorimotor coupling in music and the psychology of the groove. Journal of Experimental Psychology 2012, 141, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senn, O.; Kilchenmann, L.; Bechtold, T.; Hoesl, F. Groove in drum patterns as a function of both rhythmic properties and listeners’ attitudes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.E.; Witek, M.A.G.; Lund, T.; Vuust, P.; Penhune, V.B. The sensation of groove engages motor and reward networks. NeuroImage 2020, 214, 116768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, J.; Burunat, I.; Modroño, C.; González-Mora, J.L.; Plata-Bello, J. Music style not only modulates the auditory cortex, but also motor related areas. Neuroscience 2021, 457, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etani, T.; Miura, A.; Kawase, S.; Fujii, S.; Keller, P.E.; Vuust, P.; Kudo, K. A review of psychological and neuroscientific research on Musical Groove. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2024, 158, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belden, A.; Quinci, M.A.; Geddes, M.; Donovan, N.J.; Hanser, S.B.; Loui, P. Functional organization of auditory and reward systems in aging. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2023, 35, 1570–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfi, A.M.; Loui, P. Musical anhedonia and rewards of music listening: Current advances and a proposed model. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019, 1464, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alluri, V.; Brattico, E.; Toiviainen, P.; Burunat, I.; Bogert, B.; Numminen, J.; Kliuchko, M. Musical expertise modulates functional connectivity of limbic regions during continuous music listening. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain 2015, 25, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S.; Fritz, T.; v. Cramon, D.Y.; Müller, K.; Friederici, A.D. Investigating emotion with music: An fmri study. Human Brain Mapping 2005, 27, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Martinez, M.J.; Parsons, L.M. Passive music listening spontaneously engages limbic and paralimbic systems. NeuroReport 2004, 15, 2033–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Herrero, E.; Dagher, A.; Farrés-Franch, M.; Zatorre, R.J. Unraveling the Temporal Dynamics of Reward Signals in Music-Induced Pleasure with TMS. The Journal of neuroscience : The official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2021, 41, 3889–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimpoor, V.N.; van den Bosch, I.; Kovacevic, N.; McIntosh, A.R.; Dagher, A.; Zatorre, R.J. Interactions between the nucleus accumbens and auditory cortices predict music reward value. Science 2013, 340, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Molina, N.; Mas-Herrero, E.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A.; Zatorre, R.J.; Marco-Pallarés, J. Neural correlates of specific musical anhedonia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M.E.; Ellis, R.J.; Schlaug, G.; Loui, P. Brain connectivity reflects human aesthetic responses to music. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2016, 11, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Belden, A.; Hanser, S.B.; Geddes, M.R.; Loui, P. Resting-state connectivity of auditory and reward systems in alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Zatorre, R. State-dependent connectivity in auditory-reward networks predicts peak pleasure experiences to music. PLoS biology 2024, 22, e3002732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loui, P.; Grent-’t-Jong, T.; Torpey, D.; Woldorff, M. Effects of attention on the neural processing of harmonic syntax in western music. Cognitive Brain Research 2005, 25, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäncke, L.; Leipold, S.; Burkhard, A. The neural underpinnings of music listening under different attention conditions. NeuroReport 2018, 29, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, K.J.; Sampaio, G.; James, T.; Przysinda, E.; Hewett, A.; Spencer, A.E.; Morillon, B.; Loui, P. Rapid modulation in music supports attention in listeners with attentional difficulties. Communications Biology 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcher, A.; Frommann, I.; Koppara, A.; Wolfsgruber, S.; Jessen, F.; Wagner, M. Face-name associative recognition deficits in subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2017, 56, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, O.; Markiewicz, C.J.; Blair, R.W.; Moodie, C.A.; Isik, A.I.; Erramuzpe, A.; Kent, J.D.; Goncalves, M.; DuPre, E.; Snyder, M.; Oya, H.; Ghosh, S.S.; Wright, J.; Durnez, J.; Poldrack, R.A.; Gorgolewski, K.J. FMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nature Methods 2018, 16, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain connectivity 2012, 2, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Castanon, A. (2020). Handbook of Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods in CONN. Hilbert Press. [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Ashburner, J.; Frith, C.D.; Poline, J.B.; Heather, J.D.; Frackowiak, R.S. Spatial registration and normalization of images. Human Brain Mapping 1995, 3, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettekoven, C.; Zhi, D.; Shahshahani, L.; Pinho, A.L.; Saadon-Grosman, N.; Buckner, R.L.; Diedrichsen, J. A hierarchical atlas of the human cerebellum for functional precision mapping. Nature communications 2024, 15, 8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinov, M.; Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. NeuroImage 2010, 52, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupacher, J.; Hove, M.J.; Novembre, G.; Schütz-Bosbach, S.; Keller, P.E. Musical groove modulates motor cortex excitability: A TMS investigation. Brain and cognition 2013, 82, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodal, H.P.; Osnes, B.; Specht, K. Listening to Rhythmic Music Reduces Connectivity within the Basal Ganglia and the Reward System. Frontiers in neuroscience 2017, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.L.; Story, K.M.; Harman, E.; Burns, D.S.; Bradt, J.; Edwards, E.; Golden, T.L.; Gold, C.; Iversen, J.R.; Habibi, A.; Johnson, J.K.; Lense, M.; Perkins, S.M.; Springs, S. Reporting guidelines for music-based interventions checklist: Explanation and elaboration guide. Frontiers in Psychology 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenmüller, E.; Marco-Pallares, J.; Münte, T.F.; Schneider, S. Neural reorganization underlies improvement in stroke-induced motor dysfunction by music-supported therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2009, 1169, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity graphs with the contrast Music Listening Task > Rest in matrix-form (a) and ring-form (b). For both graphs, warmer colors (red-yellow) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during task, and cooler colors (green-blue) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during rest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 FDR corrected, and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network Based Statistics [NBS]).

Figure 1.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity graphs with the contrast Music Listening Task > Rest in matrix-form (a) and ring-form (b). For both graphs, warmer colors (red-yellow) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during task, and cooler colors (green-blue) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during rest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 FDR corrected, and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network Based Statistics [NBS]).

Figure 2.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity graphs with the contrast Music Listening Task > Face-name Task in matrix-form (a) and ring-form (b). For both graphs, warmer colors (red-yellow) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during task, and cooler colors (green-blue) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during rest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 FDR corrected, and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network Based Statistics [NBS]).

Figure 2.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity graphs with the contrast Music Listening Task > Face-name Task in matrix-form (a) and ring-form (b). For both graphs, warmer colors (red-yellow) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during task, and cooler colors (green-blue) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during rest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 FDR corrected, and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network Based Statistics [NBS]).

Figure 3.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity graphs with the contrast SART and WM combined > Rest in matrix-form (a) and ring-form (b). For both graphs, warmer colors (red-yellow) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during task, and cooler colors (green-blue) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during rest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 FDR corrected, and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network Based Statistics [NBS]).

Figure 3.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity graphs with the contrast SART and WM combined > Rest in matrix-form (a) and ring-form (b). For both graphs, warmer colors (red-yellow) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during task, and cooler colors (green-blue) indicate higher FC between two given ROIs during rest. The connection threshold was p < 0.05 FDR corrected, and the cluster threshold was p < 0.05 (FDR corrected based on Network Based Statistics [NBS]).

Figure 4.

Seed-based connectivity maps with the contrast Music Listening Task > Rest, taking the average of seeds within the auditory network (a), the reward network (b), and the motor network (c). All voxel and cluster significance thresholds were set to p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

Figure 4.

Seed-based connectivity maps with the contrast Music Listening Task > Rest, taking the average of seeds within the auditory network (a), the reward network (b), and the motor network (c). All voxel and cluster significance thresholds were set to p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

Figure 5.

Seed-based connectivity maps with the contrast Music Listening Task > Face-name Task, taking the average of seeds within the auditory network (a), the reward network (b), and the motor network (c). All voxel and cluster significance thresholds were set to p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

Figure 5.

Seed-based connectivity maps with the contrast Music Listening Task > Face-name Task, taking the average of seeds within the auditory network (a), the reward network (b), and the motor network (c). All voxel and cluster significance thresholds were set to p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

Figure 6.

Seed-based connectivity maps with the contrast SART and WM combined > Rest, taking the average of seeds within the auditory network (a), the reward network (b), and the motor network (c). All voxel and cluster significance thresholds were set to p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

Figure 6.

Seed-based connectivity maps with the contrast SART and WM combined > Rest, taking the average of seeds within the auditory network (a), the reward network (b), and the motor network (c). All voxel and cluster significance thresholds were set to p < 0.05 FDR corrected.

Figure 7.

Node graphs for the the Music Listening Task > Rest contrast depicting graph theory measures of degree (a), betweenness centrality (b), clustering coefficient (c), and global efficiency (d).

Figure 7.

Node graphs for the the Music Listening Task > Rest contrast depicting graph theory measures of degree (a), betweenness centrality (b), clustering coefficient (c), and global efficiency (d).

Figure 8.

Node graphs for the Music Listening Task > Face-name Task contrast depicting graph theory measures of degree (a), betweenness centrality (b), clustering coefficient (c), local efficiency (d), and global efficiency (e).

Figure 8.

Node graphs for the Music Listening Task > Face-name Task contrast depicting graph theory measures of degree (a), betweenness centrality (b), clustering coefficient (c), local efficiency (d), and global efficiency (e).

Figure 9.

Node graphs for the SART and WM combined > Rest contrast depicting graph theory measures of degree (a), betweenness centrality and clustering coefficient (b), and global efficiency (c).

Figure 9.

Node graphs for the SART and WM combined > Rest contrast depicting graph theory measures of degree (a), betweenness centrality and clustering coefficient (b), and global efficiency (c).

Table 1.

Music Listening Task > Rest.

Table 1.

Music Listening Task > Rest.

| Measures |

Networks |

ROIs |

Beta |

T (DF = 35) |

p-FDR |

| Degree |

Reward |

FOrb r |

3.04 |

4.64 |

0.002315 |

| Betweenness Centrality |

Auditory

Auditory |

pSTG l (Cluster 1)

toITG l |

-0.02

-0.02 |

-3.51

-3.37 |

0.045299

0.045299 |

| Clustering Coefficient |

Auditory |

aMTG l |

-0.10 |

-3.58 |

0.04877 |

| Global Efficiency |

Reward

Reward

Auditory

Reward |

FOrb r

Amygdala r

pSTG r (Cluster 2)

Amygdala l |

0.08

0.09

0.03

0.05 |

4.24

3.23

3.17

3.15 |

0.007624

0.041181

0.041181

0.041181 |

Table 2.

Music Listening Task > Face-name Task.

Table 2.

Music Listening Task > Face-name Task.

| MEASURES |

NETWORKS |

ROIS |

BETA |

T (DF = 35) |

P-FDR |

| DEGREE |

Motor

Motor

Reward

Reward |

PostCG l

PostCG r

Putamen l

Putamen r |

-2.75

-2.62

1.81

1.51 |

-4.29

-4.06

3.76

3.32 |

0.006487

0.006487

0.010042

0.025535 |

| BETWEENNESS CENTRALITY |

Auditory

Auditory

Auditory |

HG r

pSTG l (Cluster 1)

pMTG r |

0.03

-0.04

0.03 |

4.21

-4.00

3.31 |

0.007574

0.007574

0.035887 |

| Clustering Coefficient |

Auditory

Auditory

Motor

Auditory

Reward

Motor |

pSTG r (Cluster 1)

pSTG l (Cluster 1)

PostCG r

toITG l

PCC

midFG r |

0.13

0.13

0.12

0.14

-0.28

-0.09 |

4.39

4.28

3.58

3.19

-3.13

-2.99 |

0.003256

0.003256

0.016496

0.037092

0.039538

0.039538 |

| Local Efficiency |

Auditory Auditory Auditory |

pSTG r (Cluster 1)

pSTG l (Cluster 1)

toITG l |

0.08

0.08

0.17 |

4.18

4.07

3.48 |

0.005991

0.005991

0.023270 |

| Global Efficiency |

Reward

Reward

Reward

Reward

Reward

Motor

Motor

Auditory

Motor

Reward

Reward

Auditory

Reward |

Pallidum l

Putamen l

Putamen r

Pallidum r

FOrb r

PostCG r

PostCG l

pMTG r

midFG l

FOrb l

NAcc l

pSTG r (Cluster 1)

Caudate l |

0.09

0.09

0.08

0.07

0.04

-0.06

-0.05

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.08

-0.03

0.07 |

4.55

4.36

4.22

3.79

3.71

-3.64

-3.59

3.41

2.97

2.93

2.74

-2.72

2.62 |

0.002675

0.002675

0.002714

0.006949

0.006949

0.006979

0.006979

0.010164

0.029074

0.029074

0.041247

0.041247

0.049220 |

Table 3.

Music Listening Task > Face-name Task.

Table 3.

Music Listening Task > Face-name Task.

| Measures |

Networks |

ROIs |

Beta |

T (DF= 35) |

P-FDR |

| Degree |

Reward

Reward

Reward

Reward

Reward

Reward

Motor

Auditory

Auditory

Motor

Motor

Auditory

Auditory

Reward |

IC r

NAcc l

NAcc r

Caudate l

Pallidum r

IC l

MidFG l

pSTG r (Cluster 1)

aITG r

SMA l

PreCG l

pMTG l (Cluster 1)

pITG r

FOrb l |

-2.41

0.57

0.46

1.08

0.18

-1.71

1.47

0.95

-1.32

-1.21

-1.20

0.99

-1.29

1.40 |

-4.92

4.14

4.01

3.83

3.55

-3.40

3.36

3.03

-2.97

-2.88

-2.81

2.80

-2.76

2.70 |

0.000993

0.005005

0.005005

0.006186

0.010870

0.013082

0.013082

0.027960

0.029412

0.032720

0.033910

0.033910

0.034359

0.037307 |

| Clustering Coefficient |

Auditory |

pSTG r (Cluster 1) |

0.13 |

4.88 |

0.000971 |

| Local Efficiency |

Auditory |

pSTG r (Cluster 1) |

0.10 |

4.22 |

0.007008 |

| Global Efficiency |

Motor

Auditory

Auditory

Reward

Reward

Motor

Motor

Reward

Reward

Reward

Motor

Reward |

midFG l

pMTG l (Cluster 1)

pSTG r (Cluster 2)

Pallidum r

NAcc l

midFG r

PreCG l

FOrb l

Caudate l

NAcc r

SFG l

ACC |

0.04

0.02

0.09

0.05

0.05

0.02

-0.02

0.03

0.07

0.05

0.02

0.02 |

5.14

4.26

3.71

3.54

3.47

3.33

-3.13

3.08

2.96

2.93

2.86

2.69 |

0.000517

0.003560

0.011548

0.013819

0.013819

0.016608

0.024366

0.024437

0.029337

0.029337

0.031560

0.044730 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).