Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

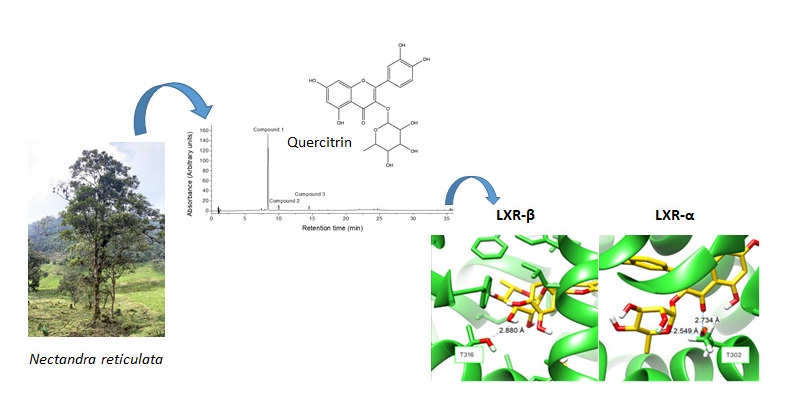

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

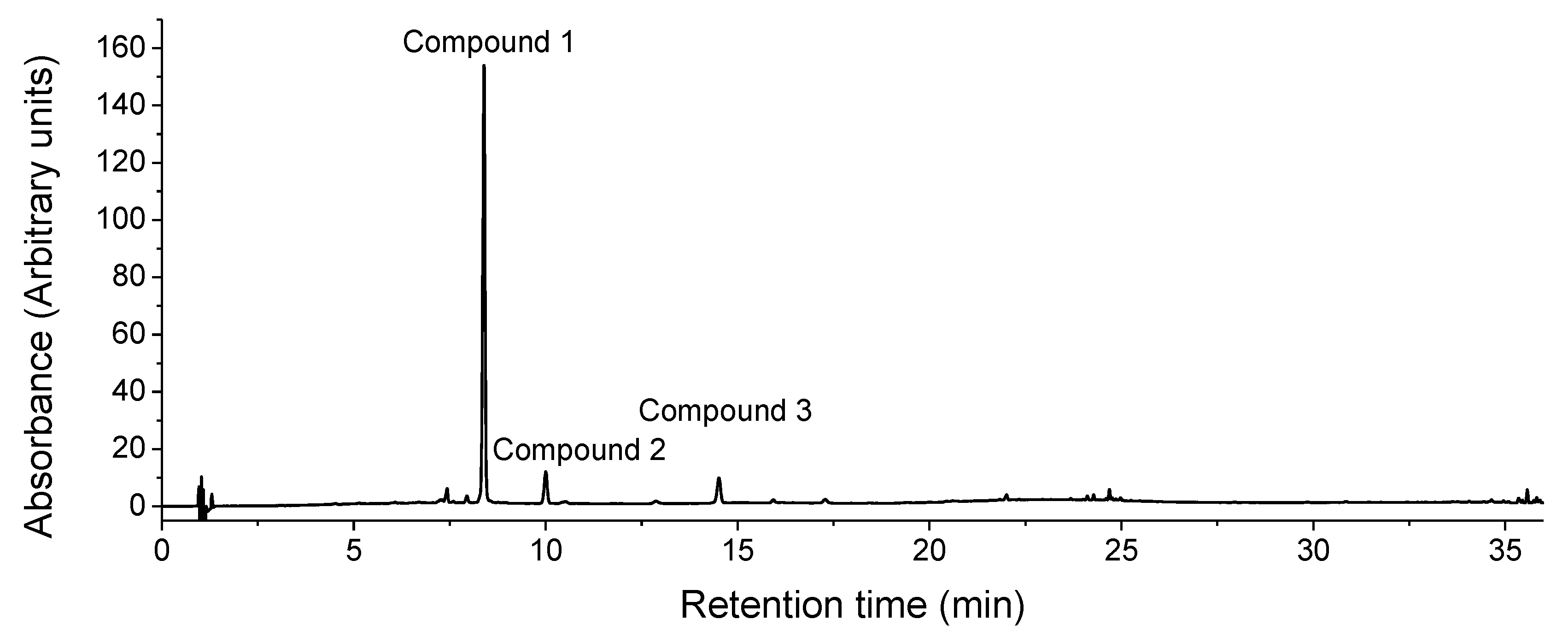

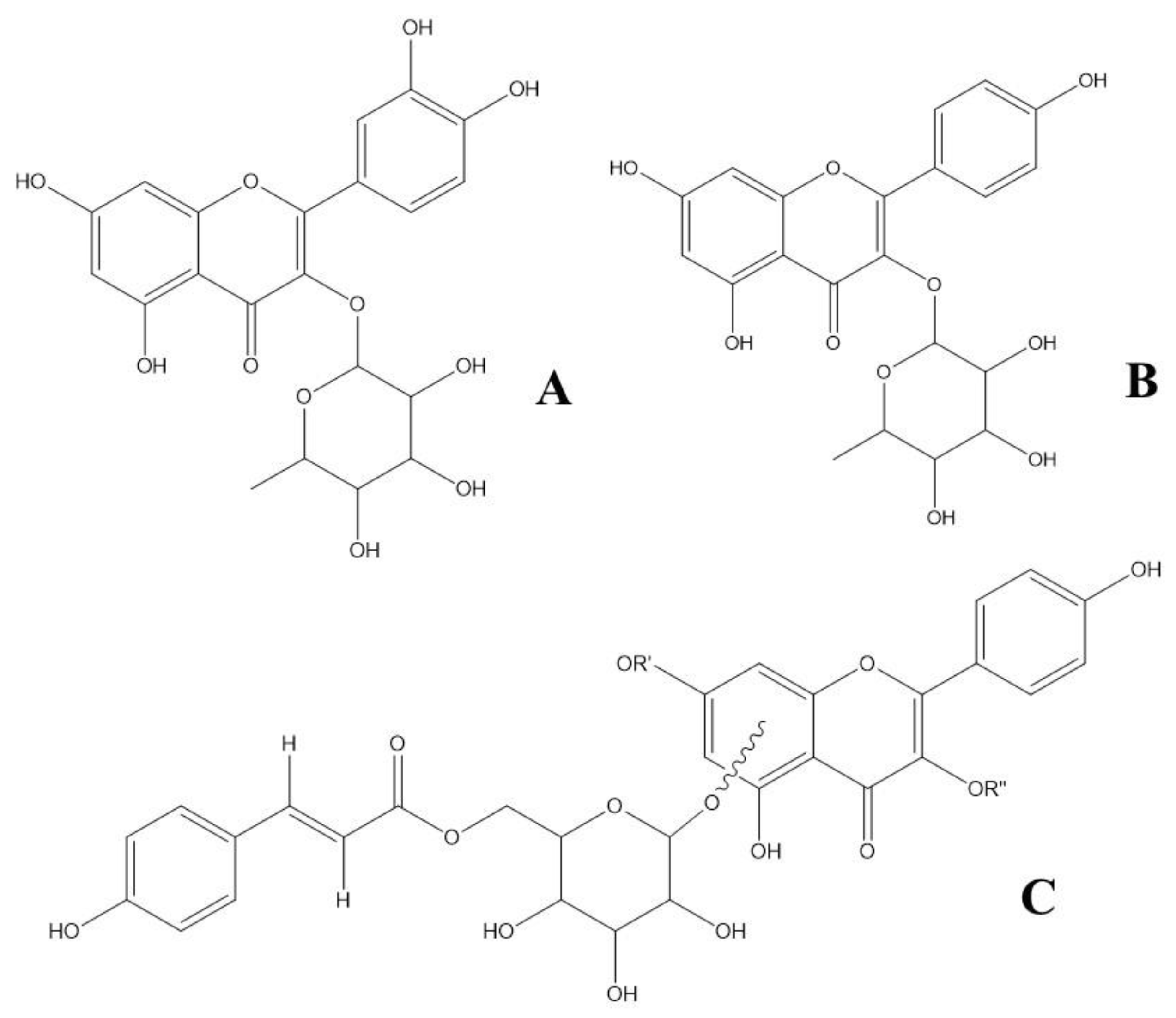

2.1. Identification of the Metabolites

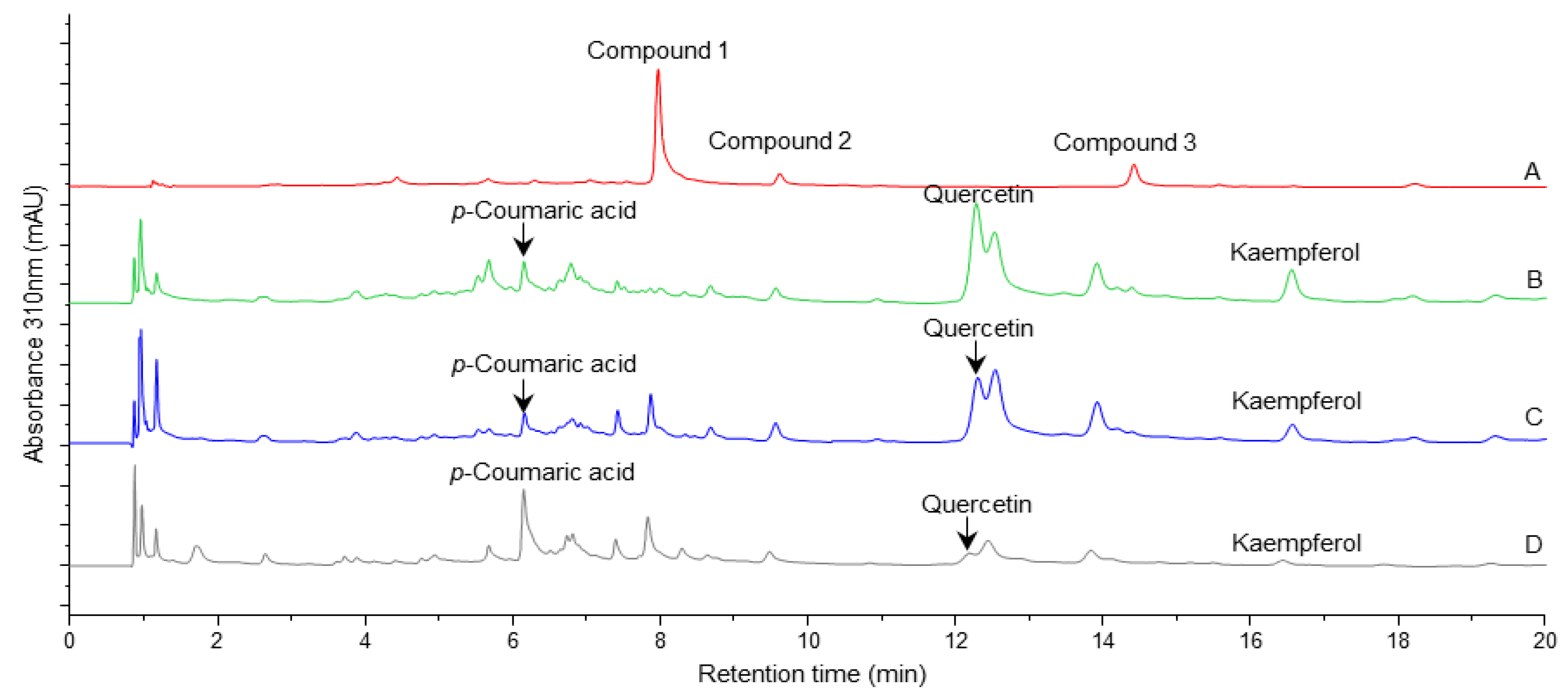

2.2. Evaluation of Hydrolysis Conditions.

2.3. Molecular Docking into the Agonist Binding Sites of LXRα and LXRβ Receptors.

2.4. In Vitro Upregulation of LXRs Target Genes by N. reticulata Extracted Compounds.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Standards.

3.2. Plant Material and Extraction.

3.3. Acid Hydrolysis of the Plant Extract.

3.4. Identification of Metabolites

3.5. Molecular Docking.

3.6. In Vitro Upregulation of LXRs Target Genes by N. reticulata Extracted Compounds

3.7. Cell Culture and Viability.

3.8. Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LXRs | Liver X Receptors |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| ABCA1 | ABC transporter protein member 1 |

| AD | Alzheimer Diseases |

| RP | Reversed Phase |

| UHPLC | Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| DAD | Diode array detector |

| ESI-HR-MS | High Resolution Mass Spectrometry with Electrospray ionization |

| qRT-PCR | Real Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| LXRα | Liver X Receptors alpha |

| LXRβ | Liver X Receptors beta |

| a.m.u. | Atomic Mass Unit |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HCl | Hydrocloryc acid |

| Q-TOF | Quadrupole Time of Flight |

References

- World Health Organization, Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia, (accessed November 16, 2024).

- B. Duthey, A public health approach to innovation, 2013, 6, 74. https://www.medbox.org/pdf/5e148832db60a2044c2d5489, (accessed January 9, 2025).

- M. Calabrò, C. Rinaldi, G. Santoro and C. Crisafulli, AIMS Neurosci., 2020, 8, 86–132. [CrossRef]

- E. Mohandas, V. Rajmohan and B. Raghunath, Indian J. Psychiatry, 2009, 51, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Sandoval-Hernández, L. Buitrago, H. Moreno, G. P. Cardona-Gómez and G. Arboleda, PLoS One, 2015, 10, e0145467. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Riddell, H. Zhou, T. A. Comery, E. Kouranova, C. F. Lo, H. K. Warwick, R. H. Ring, Y. Kirksey, S. Aschmies, J. Xu, K. Kubek, W. D. Hirst, C. Gonzales, Y. Chen, E. Murphy, S. Leonard, D. Vasylyev, A. Oganesian, R. L. Martone, M. N. Pangalos, P. H. Reinhart, and J. S. Jacobsen, Mol. Cell. Neurosci., 2007, 34, 621–628. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Sodhi and N. Singh, Pharmacol. Res., 2013, 72, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- R. Koldamova and I. Lefterov, Current Alzheimer Research, 2007, 4, 171–178. [CrossRef]

- A. Bustos-Rangel, J. Muñoz-Cabrera, L. Cuca, G. Arboleda, M. Ávila-Murillo, and A.G. Sandoval-Hernández, Front. Nat. Prod, 2023, 2, 1169182. [CrossRef]

- J. Pulido-Teuta, C.E. Narváez-Cuenca, and M. Avila-Murillo, RSC Adv., 2024,14, 21874-21886. [CrossRef]

- 11.S. S. Grecco, H. Lorenzi, A. G. Tempone and J. H. G. Lago, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2016, 27, 793–810. [CrossRef]

- V. E. Macías-Villamizar, L. E. Cuca-Suárez, and E. D. Coy-Barrera, Bol. Latinoam. y del Caribe de Plantas Med. y Aromáticas, 2015, 14, 317-342, URL: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85641104007.

- S. Rattanajarasroj and S. Unchern, Neurochem Res., 2010, 35, 1196–1205. [CrossRef]

- G. Rajamanickam and S.L. Manju, Research Square, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, J. Sun, Z. Miao, X. Jiang, Y. Zheng, and G. Yang, NeuroReport, 2022, 33, 327-335. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Tolosa, H. Rogez, E. M. Silva and J. N. S. Souza, J. Braz. Chem. Soc., 2018, 29, 2475–2481. [CrossRef]

- M. Taniguchi, C. A. LaRocca, J. D. Bernat and J. S. Lindsey, J. Nat. Prod., 2023, 86, 1087–1119. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Mabry, K. R. Markham and M. B. Thomas, in The Systematic Identification of Flavonoids, eds. T. J. Mabry, K. R. Markham and M. B. Thomas, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1970, pp. 41–164.

- J. Greenham, J.B. Harborne, and C.A. Williams, Phytochem. Anal., 2003, 14,100-118. [CrossRef]

- N. Fabre, I. Rustan, E. de Hoffmann and J. Quetin-Leclercq, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom., 2001, 12, 707–715. [CrossRef]

- S. Kazuno, M. Yanagida, N. Shindo and K. Murayama, Anal. Biochem., 2005, 347, 182–192. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Barbosa-Filho, M. Yoshida and O. R. Gottlieb, Phytochem., 1989, 28, 2209-221. [CrossRef]

- F. R. Garcez, W. S. Garcez, M. Martins and A. C. Cruz, Planta Med., 1999, 65, 775. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Ribeiro, V. da S. Bolzani, M. Yoshida, L. S. Santos, M. N. Eberlin and D. H. S. Silva, J. Braz. Chem. Soc., 2005, 16, 526–530. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Felipe, L. Z. S. Brambilla, C. Porto, E. J. Pilau and D. A. G. Cortez, Molecules, 2014, 19, 15720–15734. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Conserva, T. A. Costa-Silva, L. M. Quirós-Guerrero, L. Marcourt, J.-L. Wolfender, E. F. Queiroz, A. G. Tempone and J. H. G. Lago, Chem-Biol. Interact., 2021, 349, 109661. [CrossRef]

- J. Xiao, T. S. Muzashvili and M. I. Georgiev, Biotechnol. Adv, 2014, 32, 1145–1156. [CrossRef]

- R. Yin, B. Messner, T. Faus-Kessler, T. Hoffmann, W. Schwab, M.-R. Hajirezaei, V. von Saint Paul, W. Heller and A. R. Schäffner, J. Exp. Bot., 2012, 63, 2465–2478. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jia, M. H. Hoang, H.-J. Jun, J. H. Lee and S.-J. Lee, Bioorg. & Med. Chem. Lett., 2013, 23, 4185–4190. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, Y. Yang, Y. Yu, G. Wen, N. Shang, W. Zhuang, D. Lu, B. Zhou, B. Liang, X. Yue, F. Li, J. Du and X. Bu, J. Med. Chem., 2013, 56, 6033–6053. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Harris and A. S. Mildvan, Proteins: Struct., Funct., and Bioinform., 1999, 35, 275–282. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Nuutila, K. Kammiovirta, and K.-M. Oksman-Caldentey, Food Chem., 2002, 76, 519–525. [CrossRef]

- Fouache, N. Zabaiou, C. De Joussineau, L. Morel, S. Silvente-Poirot, A. Namsi, G. Lizard, M. Poirot, M. Makishima, S. Baron, J.-M. A. Lobaccaro and A. Trousson, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 2019, 190, 173–182. [CrossRef]

- S. Mallick, P. A. Marshall, C. E. Wagner, M. C. Heck, Z. L. Sabir, M. S. Sabir, C. M. Dussik, A. Grozic, I. Kaneko and P. W. Jurutka, ACS Chem. Neurosci., 2021, 12, 857–871. [CrossRef]

| Peak no. | Retention time (min) | UVmax λ (nm) | MS | MS2 | Molecular formula | AME (ppm) |

Tentative annotation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.80 | 260; 349 | 447.0936 | 300.0273 | C21H20O11 | 1.8 | Quercitrin | ||

| [M-H]- | [M-rhamnose-H]-● | ||||||||

| 303.0509 | |||||||||

| [M-rhamnose+H]+ | |||||||||

| 2 | 9.44 | 266; 341 | 431.0980 | 284.0323 | C21H20O10 | -0.5 | Afzelin | ||

| [M-H]- | [M-rhamnose-H]-● | ||||||||

| 287.0561 | |||||||||

| [M-rhamnose+H]+ | |||||||||

| 3 | 14.26 | 229; 268; 314 |

593.1296 | 285.0396 | C30H26O13 | -0.2 | Kaempferol 3-(6''-p- coumarylglucoside) or Kaempferol 7-(6''- p-coumarylglucoside) | ||

| [M-H]- | [M-coumarylglucoside-H]- | ||||||||

| 595.1464 | 309.0981 | ||||||||

| [M+H]+ | [M-kaempferol+H]+ | ||||||||

| 287.0559 | |||||||||

| [M-coumarylglucoside+H]+ | |||||||||

| Compound | Standard retention time (min) |

Standard UV λ (nm) | Hydrolyzed extract retention time (min) |

UV λ (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | 12.30 | 202; 257; 368 | 12.29 | 203; 257; 368 |

| Kaempferol | 16.59 | 197; 267; 367 | 16.57 | 197; 267; 366 |

| Luteolin | 12.63 | 208; 256; 348 | 12.54* | 230; 310* |

| p-Coumaric acid | 6.15 | 227; 310 | 6.16 | 229; 311 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).