1. Introduction

Patients with advanced metastatic radioiodine refractory non-medullary thyroid carcinoma (TC), particularly those with poorly differentiated (PDTC) and anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC), have a poor prognosis [

1]. ATC is one of the most aggressive human cancers, with rapid disease progression, a median survival of six months from diagnosis, and very limited treatment options [

2]. Understanding the pathogenesis of aggressive TC is essential for identifying novel treatment targets.

Tumor-related inflammation is fundamental in cancer pathogenesis, with numerous studies showing the role of inflammation in the initiation, growth, and development of tumors in various cancer models [

3]. This is also the case for TC. Abundant tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration in aggressive TC correlates with the presence of lymph node metastases, invasive disease, and poor prognosis [

4] and aggressive forms of TC showed higher inflammatory parameters such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and C-reactive protein compared to healthy volunteers [

5,

6]. Additionally, an association of genetic variants linked to increased proinflammatory markers such as interleukin-1β, with a higher susceptibility to develop TC and a reduced response to radioiodine treatment was reported [

7]. We have shown that the proinflammatory cellular program of TAMs interacts with TC cells and that tumor cell-derived metabolites induce epigenetic and metabolic changes responsible for these interactions. Moreover, we have shown that the transcriptional and functional phenotype of TAMs is programmed even before these myeloid cells infiltrate the tumor and are present even at the level of the bone marrow progenitors [

8].

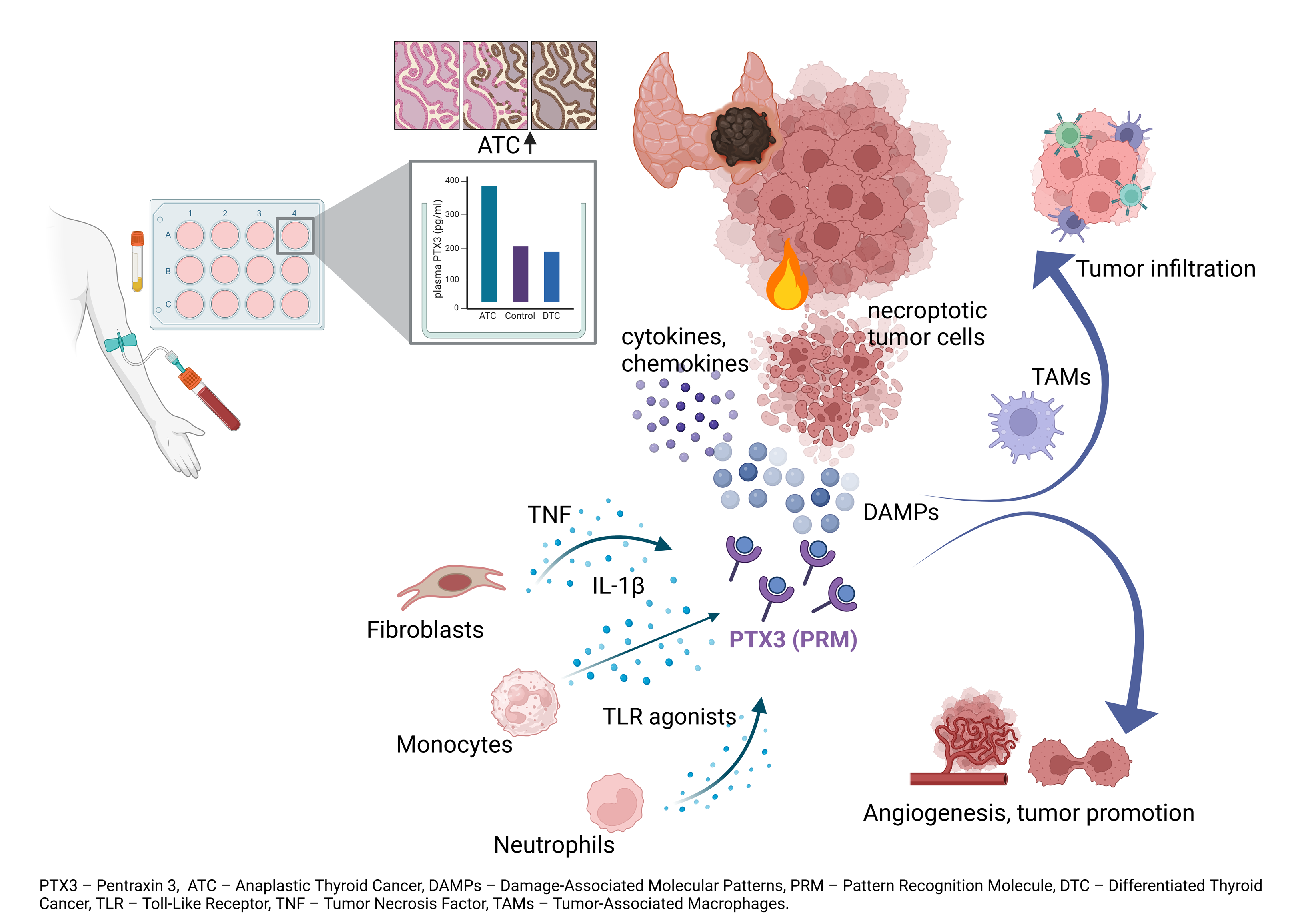

Innate immune responses are triggered when damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), are recognized by pattern recognition molecules (PRMs) [

9]. One notable group of soluble PRMs is represented by pentraxins, evolutionarily conserved molecules with roles in innate immunity and inflammation, including the regulation of complement activation and pathogen opsonization [

10].

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3), also known as Tumor Necrosis Factor-Stimulated Gene 14 protein (TSG-14), is a pleiotropic member of the long-pentraxin subfamily. It is produced locally at inflammation sites by various cell types, including myeloid, vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells, and mesenchymal and epithelial cells, in response to diverse inflammatory signals [

11]. The human

PTX3 expression is induced by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and toll-like receptors (TLR) agonists [

9,

11].

Recent in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that PTX3 is involved in cancer-related inflammation and plays a role in various aspects of cancer progression, including tumor onset, angiogenesis, metastatic spread, and cancer immune modulation [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing activities have been reported for PTX3, with its function possibly varying depending on tumor type, cellular source, and surrounding environment [

11]. The expression of the

PTX3 gene has been reported to be upregulated in different solid tumors, including ATC [

11,

15]. Higher circulating PTX3 concentrations have been reported in patients with malignant tumors, particularly in more advanced disease stages [

13,

16,

17]. Intratumoral expression of PTX3 was increased in lung cancer, primary brain tumors, and hepatocellular carcinoma versus non-neoplastic tissue, and this was also associated with worse prognosis [

17,

18,

19]. Overall, PTX3 appears to promote tumor progression in various models. However, the exact mechanism is not fully understood.

This study aims to evaluate the circulating concentrations of PTX3 in patients with TC compared to patients with benign thyroid diseases and to investigate whether these correlate with the histological TC forms, clinical parameters, and with PTX3 expression in representative tissue samples from these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

In this prospective observational cohort study, we included two sets of consecutive patients: a group of patients with various histologic subtypes of TC (papillary, follicular, oncocytic, PDTC, and ATC), and a control group consisting of patients with benign thyroid pathology (chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and multinodular goiter).

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The National Institute of Endocrinology "C. I. Parhon" (No. 08/20.04.2022) and Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands (2022-16025 & 2017-3628). All patients provided informed consent for participation.

The TC group included patients who were either newly diagnosed with TC or who were under regular follow-up for recurrent disease with locoregional or distant metastases in two tertiary centers - National Institute of Endocrinology "C. I. Parhon", Bucharest, Romania and Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Blood samples were collected prospectively between 2018 and early 2023 before surgical resection in newly diagnosed TC patients or during a follow-up visit in patients with structurally recurrent TC.

The patients in the control group were selected at the National Institute of Endocrinology C. I. Parhon, Bucharest, between November 2022-June 2023, based on their medical records, euthyroid status presently under follow-up, benign pathology on cytology, no suspicious ultrasound characteristics ultrasound, and assigned to the control group after total thyroidectomy, matched by age and sex with the TC patients.

Patients with Graves’ disease, chronic systemic inflammatory diseases, other active neoplasms, active known infections, medication interfering with the immune system, systemic anti-cancer treatment, surgery <3 months before blood withdrawal, liver or renal failure, self-reported alcohol consumption of >21 units per week or pregnancy were excluded.

Patients' demographics, type and extent of surgical resection, pathology reports, and disease staging were collected from electronic medical records and primary data collection.

2.2. Definitions, Outcome, and Measurements

In patients with lymphocytic thyroiditis, the diagnosis was documented by high anti-TPO serum concentrations or histologic confirmation after surgery.

All patients with TC had active structural disease at the time of blood collection. The extent of TC was classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for differentiated and poorly differentiated thyroid cancer, 8th edition/TNM Classification System [

20]. Radioiodine resistance (RAIR) was defined according to previously proposed criteria [

21].

2.3. PTX3 Concentration in Circulation and Tissue Expression

Plasma PTX3 concentrations were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in blood samples collected in EDTA vacutainers from fasting patients in the morning. Samples were centrifuged at 3000g for 15 minutes within one hour of collection and stored at -80°C until analysis. PTX3 expression in tissue was assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) on paraffin-embedded samples. Single and double staining were performed to evaluate PTX3 expression and its potential co-localization with CD68-positive macrophages (

Supplementary Table S1).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In the main analysis, plasma PTX3 concentrations were compared between patients with benign thyroid disease and TC, and between subgroups of TC patients based on clinicopathological factors. Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Parametric (t-test, ANOVA) and non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis) were used as appropriate. Correlations between PTX3 concentrations and demographic variables were evaluated using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (Supplementary File S1).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

In total, 87 patients were included: 32 in the control group (20 benign goiter and 12 chronic autoimmune thyroiditis) and 55 in the TC group (41 preoperatively, 14 with recurrent active disease) (

Table 1). There was no significant difference in sex distribution (60.0% vs 81.2% female, p=0.650), age at the time of blood collection (55 years (48-79) vs 62 years (49-81), p=0.173) and BMI (27.5 ± 4.6 vs 30.4 ± 6.7, p=0.252) in the TC vs control group.

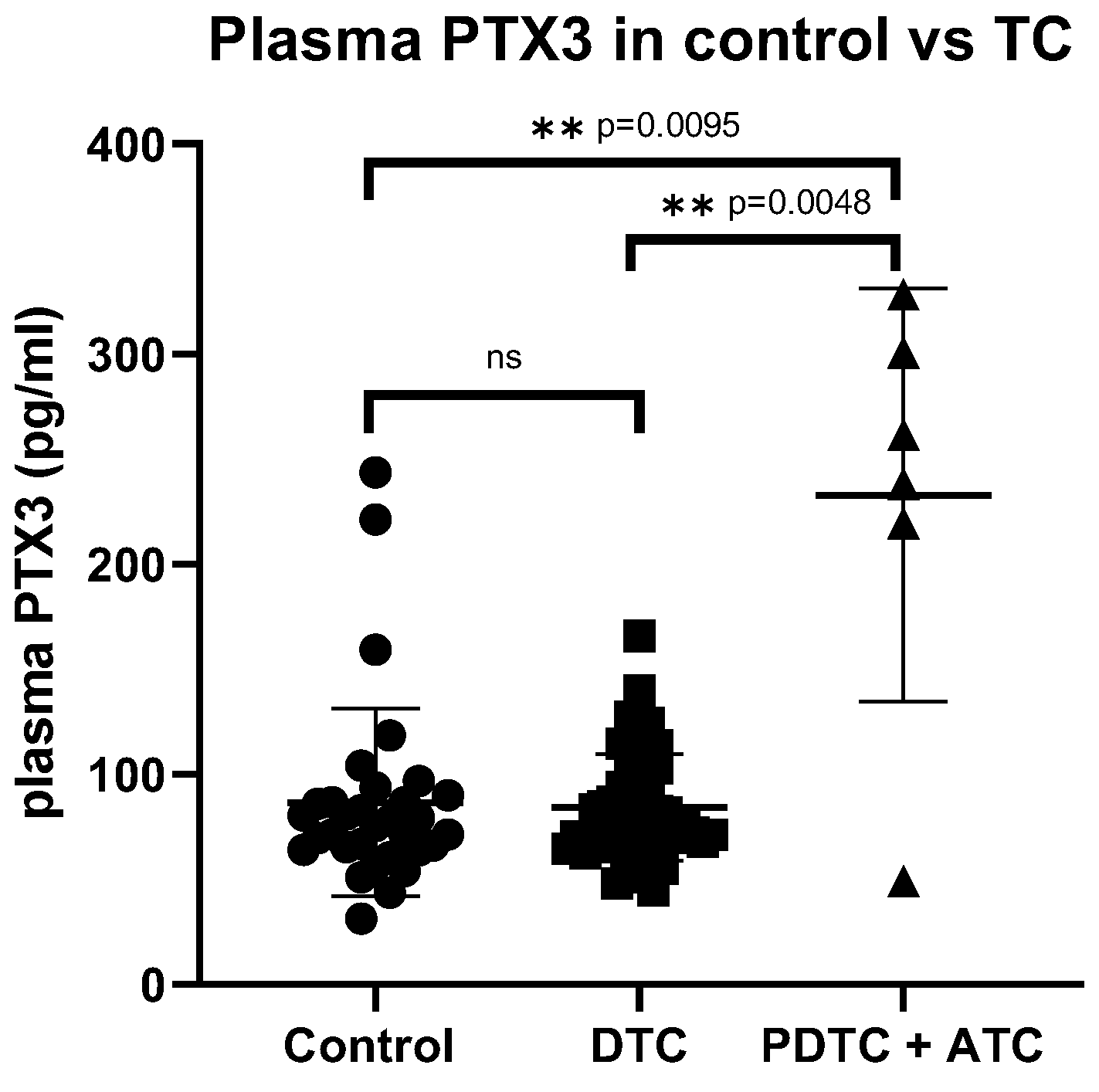

3.2. PTX3 Plasma Concentrations

The PTX3 plasma concentrations in patients with ATC (269.4 pg/ml (224.2, 321.4)) and PDTC (155.5 pg/ml (49.3, 261.7)) were significantly higher than those of patients with differentiated TC (76.6 pg/ml (69.3, 103.2)) and control patients (73.5 pg/ml (64.4, 89.1)) (p=0.004 and p=0.009, respectively) (

Figure 1). Overall, there was no significant difference in PTX3 concentrations between patients with TC and controls (p=0.275). Demographic characteristics, including age, BMI, sex, histological subtypes within differentiated tumors, disease extent, and sensitivity to RAI treatment had no significant effect on PTX3 concentrations (

Table 1).

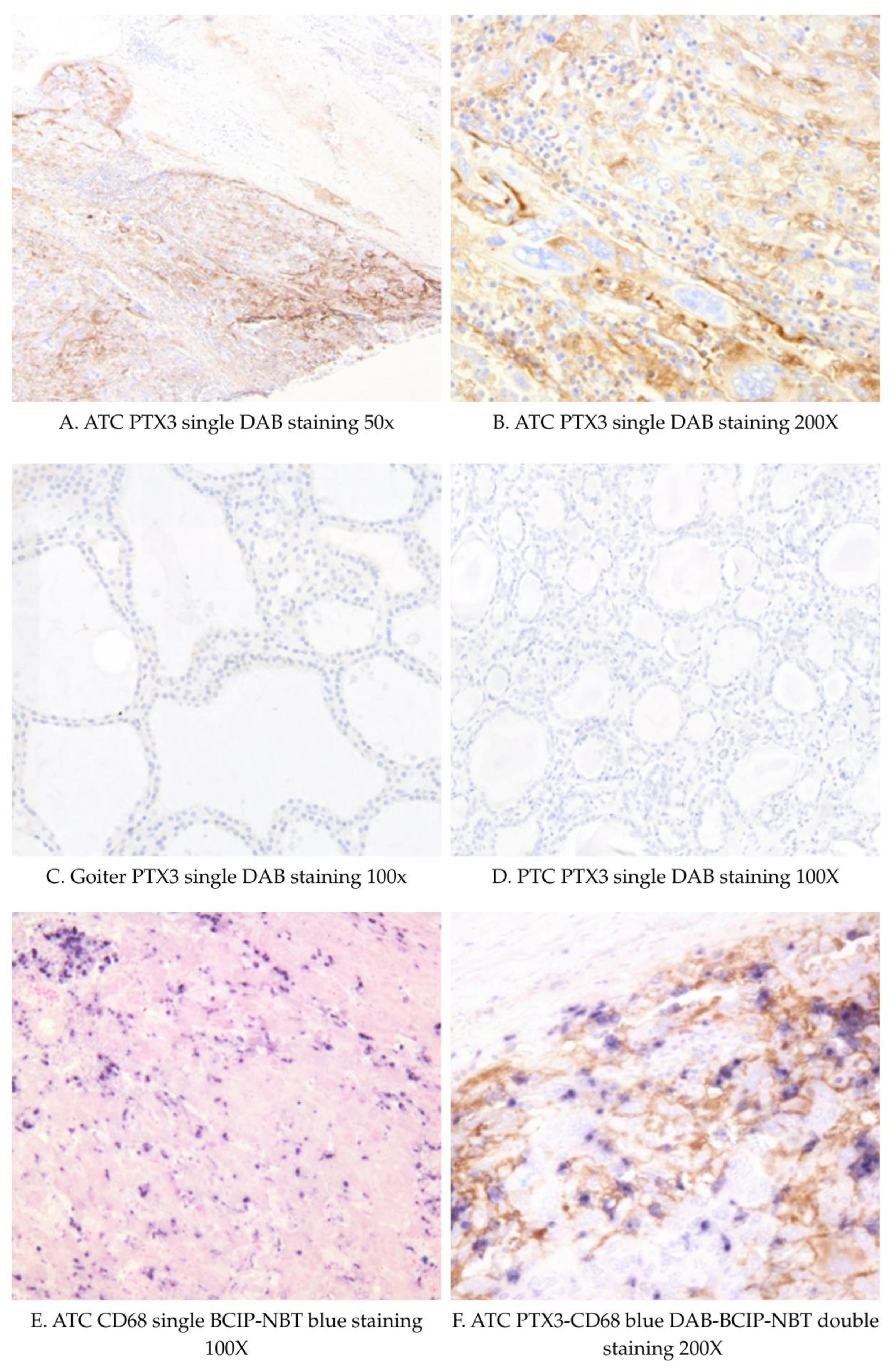

3.3. PTX3 Expression and Distribution in TC Tissue

We have further assessed PTX3 and CD68 expression by immunohistochemistry in tissue samples from 2 patients with goiter, 1 patient with papillary TC (PTC), and 4 patients with ATC (

Figure 2). A summary of immunohistochemistry findings is presented in

Supplementary Table S2. PTX3 staining was strongly positive in 3 out of 4 ATCs, predominantly intracellular with some interstitial staining. There was a higher number of infiltrating CD68-positive cells in ATC compared to the other patients. Nonetheless, there were only a few scattered CD68-positive cells, which also stained positively for PTX3, indicating a low co-localization. The PTX3-negative ATC patient (ATC4) had high plasma PTX3 levels but weak tissue PTX3 and CD68 staining. PTX3 staining was virtually absent in the PTC and goiter tissues, with sparse and faint staining.

4. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the expression and potential role of PTX3 in ATC. While overall no significant difference in plasma PTX3 concentrations was observed between patients with TC and benign thyroid disease, increased PTX3 expression was found in patients with ATC, suggesting its association with the aggressive clinical phenotype of this cancer subtype. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate PTX3 either in plasma or tissue in ATC.

The findings have several potential implications. As such, it has previously been suggested that PTX3 could reflect a more aggressive tumor phenotype in other cancers and thus could have prognostic implications. A genome-wide analysis of ATC and other differentiated subtypes of TC indicated that

PTX3, COLEC12, and

PDGFRA were overexpressed in ATC while being underexpressed in follicular or PTC [

15]. Another bioinformatic analysis of eight gene-expression profiles found a four-gene prognostic signature for PTC, which included

PTX3, PAPSS2, PCOLCE2, and

TGFBR3, which showed better performances in overall survival prediction than the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system [

22]. Concerning plasma PTX3 concentrations, Chiari et al. found no differences between 53 patients with benign or malignant thyroid nodules, but higher PTX3 concentrations in these patients than in healthy volunteers. The authors hypothesized that PTX3 overexpression could be associated with active phases of nodular remodelling [

23]. In line with these results, Destek et al. found no significant difference in PTX3 plasma levels between patients with benign thyroid nodules (41 patients) and those with cytologically confirmed PTC (14 patients), regardless of nodule size or number [

24]. Our study aimed to extend these investigations to patients with a broader spectrum of TC histological phenotypes, including patients with more advanced disease. Overall, our results yielded no significant difference in PTX3 plasma concentrations between the TC group and the group of patients with benign thyroid pathology nor within the TC group, according to differentiated histological subtypes, presence and extent of active structural disease, or other aggressive features such as RAIR. However, the fact that ATC clearly showed increased concentrations of PTX3 in circulation and higher expression of PTX3 in the tissue samples aligns with previous research indicating that the role of PTX3 in cancer may be context-dependent, influenced by the specific cancer type [

9].

The present findings raise important questions about the potential contribution of PTX3 in the pathogenesis of TC, particularly aggressive forms such as ATC. PTX3 has been reported to promote cell migration and invasion in various tumor models. The in vitro study by Kondo et al. demonstrated that high PTX3 levels produced by pancreatic carcinoma cell lines are linked to tumor progression and poor patient outcomes [

25]. PTX3 enhances EGF-induced migration, invasion, and metastasis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells [

12]. Song et al. reported a significantly higher PTX3 immunostaining in hepatocellular carcinoma compared to normal adjacent liver tissue and showed that PTX3 promotes tumor invasion, cell proliferation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by in vivo xenograft experiments [

17]. The high PTX3 expression we found in ATC tissues supports the hypothesis that PTX3 is involved in the inflammatory microenvironment of aggressive tumors, potentially contributing to macrophage infiltration and function [

17]. In the ATC patients there was an increased infiltration with CD68 positive macrophages, concordant with the high infiltration with TAMs previously reported [

4], as well as a strong PTX3 expression in both tumoral cells and interstitial ATC tissues. However, immunohistochemically, PTX3 and CD68 staining were virtually absent in patients with goiter, and in those with PTC. These findings are in line with the high PTX3 expression at the tissue level in other tumoral tissues, such as gliomas, particularly high-grade anaplastic gliomas, and glioblastoma, unlike the low-grade tumors [

19]. Interestingly, The Human Protein Atlas has published expression data of PTX3 in cell lines including TC, and reported higher amounts of PTX3 produced by the ATC-derived cell line 8505C, compared to ATC-derived cell line CAL-62, squamous cell TC derived cell line SW579, PTC derived cell lines (BCPAP, BHT-101, TPC-1), follicular TC derived cell lines (FTC-133, FTC-238) [

26]. In the high-grade glioma tissue, PTX3 expression was expressed by both tumor cells and activated macrophages [

19]. In our study, however, there was a low co-localization of the CD68 and PTX3 in the tumor microenvironment, suggesting that PTX3 was mainly produced by tumoral cells, other immune cells, or stromal cells rather than the CD68-positive macrophages highly infiltrating the tumors. Moreover, the finding of a high PTX3 plasma concentration in one patient in which the tissue expression of PTX3 was virtually absent suggests that the PTX3 could also be even synthesized outside the tumor site, such as the liver, potentially upon stimulatory effects of other systemic proinflammatory cytokines such as the IL-6, also reported to be increased in ATC [

27].

Our study has some limitations. PTX3 plasma concentrations could reflect other systemic inflammatory conditions. Patients with ATC were significantly older than patients with benign thyroid disease, thus possibly harbouring endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, with associated smoldering inflammation, hence potentially confounding factors. However, none of the included ATC patients had a medical history of cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, in our study, age did not correlate significantly with plasma PTX3 concentrations. Other limitations include the small sample size, heterogeneity of the cohort, and inability to perform comprehensive analyses across all groups, histologic subtypes, or AJCC stages and the lack of a healthy cohort.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides novel insights into the expression and potential role of PTX3 in ATC. While overall no significant difference in plasma PTX3 levels was observed between patients with TC and benign thyroid disease, increased PTX3 expression was found in patients with ATC, suggesting its association with the aggressive clinical phenotype of this cancer subtype. The immunohistochemistry experiments revealed only a few double-positive TAMs, suggesting that PTX3 might likely be produced by tumoral cells, stromal cells, or other immune cells. Despite the limitations of this study, the findings point to PTX3 as a potential contributor to the inflammatory microenvironment in ATC. Future research should focus on validating these findings in larger cohorts and utilizing advanced technologies to further explore the mechanistic pathways of PTX3 in the immunologic landscape of aggressive thyroid cancer.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Standard immunostaining protocol for paraffin-section soft tissues: PTX3 and CD68 double staining; Table S2: PTX3 and CD68 expression in TC tissues (summary of IHC findings); File S1. Methodology: PTX3 plasma measurement, immunohistochemical assessment, and statistical analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T.N.-M.; Methodology, R.T.N.-M., A.B., P.vanH., M.J., L.vanE.; Investigation, R.T.N.-M., A.B., P.vanH., M.J., K.R., B.W., L.vanE., I.vanE.-vanG.; Data Curation, R.T.N.-M., A.B., P.vanH., I.vanE.-vanG.; Formal Analysis, A.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.T.N.-M., A.B., P.vanH., M.J.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.T.N.-M., A.B., P.vanH., M.J., K.R., B.W., L.vanE., D.I., I.vanE.-vanG., C.B.; Supervision, R.T.N.-M.; Funding Acquisition, R.T.N.-M. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Joint Programme for Rare Disease under Research mobility grant EJP WP 17 and by the Next Generation EU: Program of National Recovery and Resilience grant: Decoding the immune-inflammatory axis in rare non-medullary thyroid cancer as an innovative approach for novel combinatory therapeutic approaches Code:81/15.11.2022; Contract 760067/23/5.2023. Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of The National Institute of Endocrinology "C. I. Parhon" (No. 08/20.04.2022) and Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands (2022-16025 & 2017-3628). All patients provided informed consent for participation under ethical guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the laboratory technicians, research staff, and medical personnel whose support was invaluable in conducting this study. We are also deeply grateful to the patients who participated in this research, as their contribution made this work possible. The graphical abstract figure was created in

https://BioRender.com

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was carried out without any commercial or financial connections that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AJCC – American Joint Committee on Cancer

ATC – Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma

BMI – Body Mass Index

CD68 – Cluster of Differentiation 68 (Macrophage Marker)

DAMPs – Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns

DTC – Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

ELISA – Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

IL-1β – Interleukin-1 Beta

IL-6 – Interleukin-6

IHC – Immunohistochemistry

NMTC – Non-Medullary Thyroid Cancer

PDTC – Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma

PRMs – Pattern Recognition Molecules

PTC – Papillary Thyroid Cancer

PTX3 – Pentraxin 3

RAIR – Radioiodine Resistance

TC – Thyroid Cancer

TAM – Tumor-Associated Macrophage

TLR – Toll-Like Receptor

TNF – Tumor Necrosis Factor

TSG-14 – Tumor Necrosis Factor-Stimulated Gene 14

References

- Mohebati A, DiLorenzo M, Palmer F, Patel SG, Pfister D, Lee N, et al. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: A 25-year Single-Institution Experience. Ann Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2014 May 1 [cited 2023 Sep 8];21(5):1665–70. [CrossRef]

- Durante C, Montesano T, Attard M, Torlontano M, Monzani F, Costante G, et al. Long-Term Surveillance of Papillary Thyroid Cancer Patients Who Do Not Undergo Postoperative Radioiodine Remnant Ablation: Is There a Role for Serum Thyroglobulin Measurement? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism [Internet]. 2012 Aug [cited 2019 Aug 2];97(8):2748–53. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008 Jul 24;454(7203):436–44. [CrossRef]

- Ryder M, Ghossein RA, Ricarte-Filho JCM, Knauf JA, Fagin JA. Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008 Dec;15(4):1069–74. [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiecki S, Stępień T, Kuzdak K, Stępień H, Krupiński R, Seehofer D, et al. Serum levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) in thyroid cancer patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg [Internet]. 2008 May 1 [cited 2021 Jul 11];393(3):275–80. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki S, Shibata M, Gonda K, Kanke Y, Ashizawa M, Ujiie D, et al. Immunosuppression involving increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels, systemic inflammation and hypoalbuminemia are present in patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov;1(6):959–64. [CrossRef]

- Plantinga TS, Ms P, M O, Lab J, D P, Jw S, et al. Association of NF-κB polymorphisms with clinical outcome of non-medullary thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine-related cancer [Internet]. 2017 Jul [cited 2024 Sep 23];24(7). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28428267/. [CrossRef]

- Rabold K, Zoodsma M, Grondman I, Kuijpers Y, Bremmers M, Jaeger M, et al. Reprogramming of myeloid cells and their progenitors in patients with non-medullary thyroid carcinoma. Nature Communications. 2022 Oct 18;13. [CrossRef]

- Doni A, Stravalaci M, Inforzato A, Magrini E, Mantovani A, Garlanda C, et al. The Long Pentraxin PTX3 as a Link Between Innate Immunity, Tissue Remodeling, and Cancer. Front Immunol. 2019;10:712. [CrossRef]

- Bottazzi B, Vouret-Craviari V, Bastone A, De Gioia L, Matteucci C, Peri G, et al. Multimer Formation and Ligand Recognition by the Long Pentraxin PTX3: SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES WITH THE SHORT PENTRAXINS C-REACTIVE PROTEIN AND SERUM AMYLOID P COMPONENT*. Journal of Biological Chemistry [Internet]. 1997 Dec 26 [cited 2023 Sep 8];272(52):32817–23. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021925818396248. [CrossRef]

- Giacomini A, Ghedini GC, Presta M, Ronca R. Long pentraxin 3: A novel multifaceted player in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2018 Jan;1869(1):53–63. [CrossRef]

- Chang WC, Wu SL, Huang WC, Hsu JY, Chan SH, Wang JM, et al. PTX3 gene activation in EGF-induced head and neck cancer cell metastasis. Oncotarget [Internet]. 2015 Mar 8 [cited 2023 Sep 8];6(10):7741–57. Available from: https://www.oncotarget.com/article/3482/text/. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Zhao Y, Guo L. Increased serum pentraxin-3 level predicts poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer after curative surgery, a cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Oct;97(40):e11780. [CrossRef]

- Ma D, Zong Y, Zhu ST, Wang YJ, Li P, Zhang ST. Inhibitory Role of Pentraxin-3 in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Chinese Medical Journal [Internet]. 2016 Sep 20 [cited 2024 Jul 24];129(18):2233–40. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00029330-201609200-00016.

- Espinal-Enríquez J, Muñoz-Montero S, Imaz-Rosshandler I, Huerta-Verde A, Mejía C, Hernández-Lemus E. Genome-wide expression analysis suggests a crucial role of dysregulation of matrix metalloproteinases pathway in undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma. BMC Genomics [Internet]. 2015 Mar 18 [cited 2023 Sep 8];16(1):207. [CrossRef]

- Diamandis EP, Goodglick L, Planque C, Thornquist MD. Pentraxin-3 is a novel biomarker of lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Apr 15;17(8):2395–9. [CrossRef]

- Song T, Wang C, Guo C, Liu Q, Zheng X. Pentraxin 3 overexpression accelerated tumor metastasis and indicated poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma via driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cancer [Internet]. 2018 Jun 23 [cited 2023 Jun 12];9(15):2650–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6072810/. [CrossRef]

- Infante M, Allavena P, Garlanda C, Nebuloni M, Morenghi E, Rahal D, et al. Prognostic and diagnostic potential of local and circulating levels of pentraxin 3 in lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2016 Feb 15;138(4):983–91. [CrossRef]

- Locatelli M, Ferrero S, Martinelli Boneschi F, Boiocchi L, Zavanone M, Maria Gaini S, et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 as a correlate of cancer-related inflammation and prognosis of malignancy in gliomas. J Neuroimmunol. 2013 Jul 15;260(1–2):99–106. [CrossRef]

- Brierley JD, Mary K. Gospodarowicz, Christian Wittekind. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th edition. Eighth Edition. Wiley Blackell; 2016.

- Schlumberger M, Brose M, Elisei R, Leboulleux S, Luster M, Pitoia F, et al. Definition and management of radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology [Internet]. 2014 May 1 [cited 2024 Oct 24];2(5):356–8. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(13)70215-8/abstract.

- Luo Y, Chen R, Ning Z, Fu N, Xie M. <p>Identification of a Four-Gene Signature for Determining the Prognosis of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma by Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis</p>. IJGM [Internet]. 2022 Feb 4 [cited 2023 Sep 8];15:1147–60. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/identification-of-a-four-gene-signature-for-determining-the-prognosis--peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-IJGM. [CrossRef]

- Chiari D, Pirali B, Perano V, Leone R, Mantovani A, Bottazzi B. The crossroad between autoimmune disorder, tissue remodeling and cancer of the thyroid: The long pentraxin 3 (PTX3). Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1146017. [CrossRef]

- Destek S, Benturk B, Yapalak Y, Ozer OF. Clinical Significance of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, Leukocyte, Fibrinogen, C-Reactive Protein, and Pentraxin 3 Values in Thyroid Nodules. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul [Internet]. 2022 Jun 28 [cited 2023 Sep 8];56(2):270–5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9350052/. [CrossRef]

- Kondo S, Ueno H, Hosoi H, Hashimoto J, Morizane C, Koizumi F, et al. Clinical impact of pentraxin family expression on prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Br J Cancer [Internet]. 2013 Aug [cited 2023 Sep 8];109(3):739–46. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/bjc2013348. [CrossRef]

- The Human Protein Atlas [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000163661-PTX3/cell+line.

- Zhang L, Xu S, Cheng X, Wu J, Wang Y, Gao W, et al. Inflammatory tumor microenvironment of thyroid cancer promotes cellular dedifferentiation and silencing of iodide-handling genes expression. Pathology - Research and Practice [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Nov 14];246:154495. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0344033823001954. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).