Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

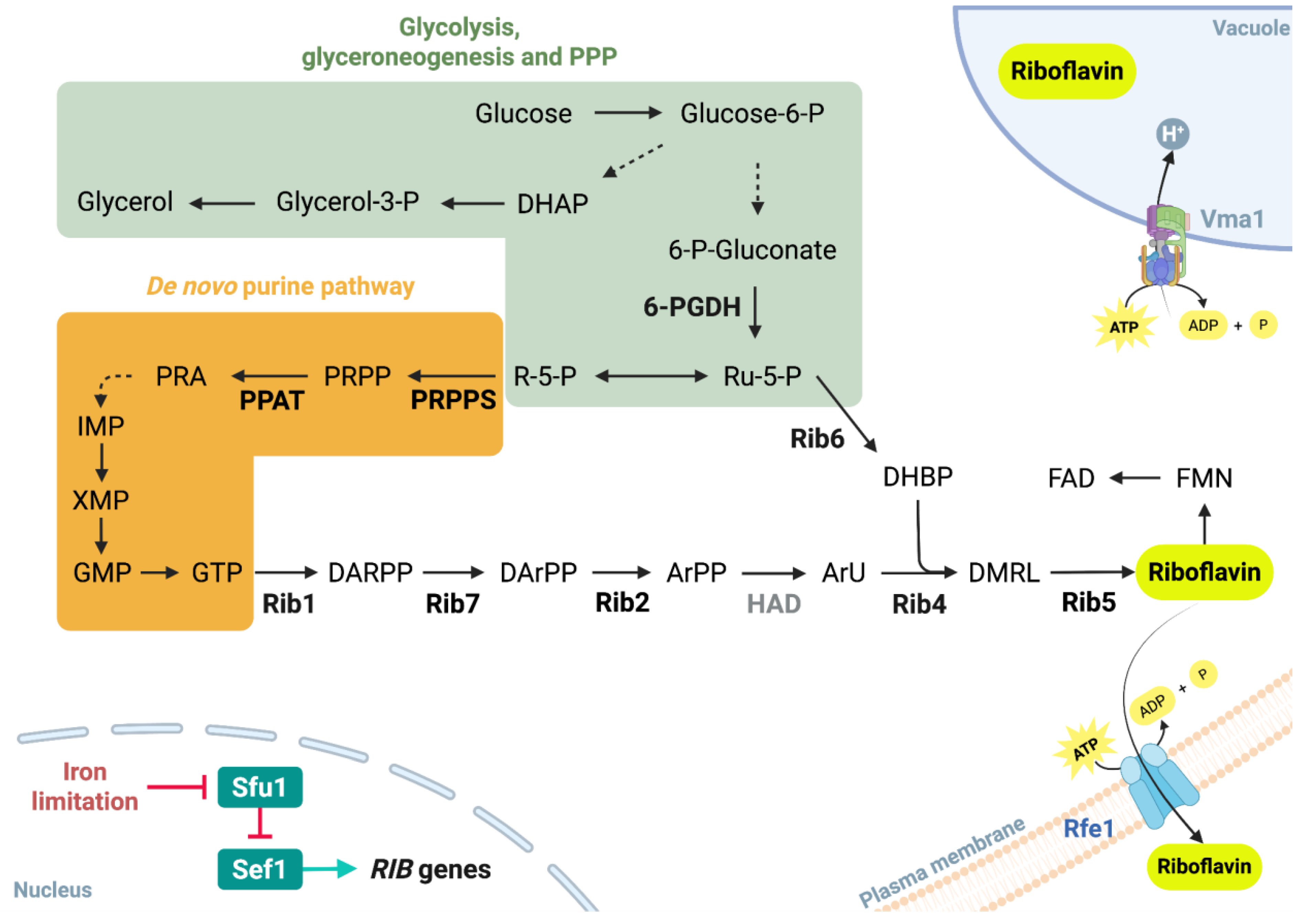

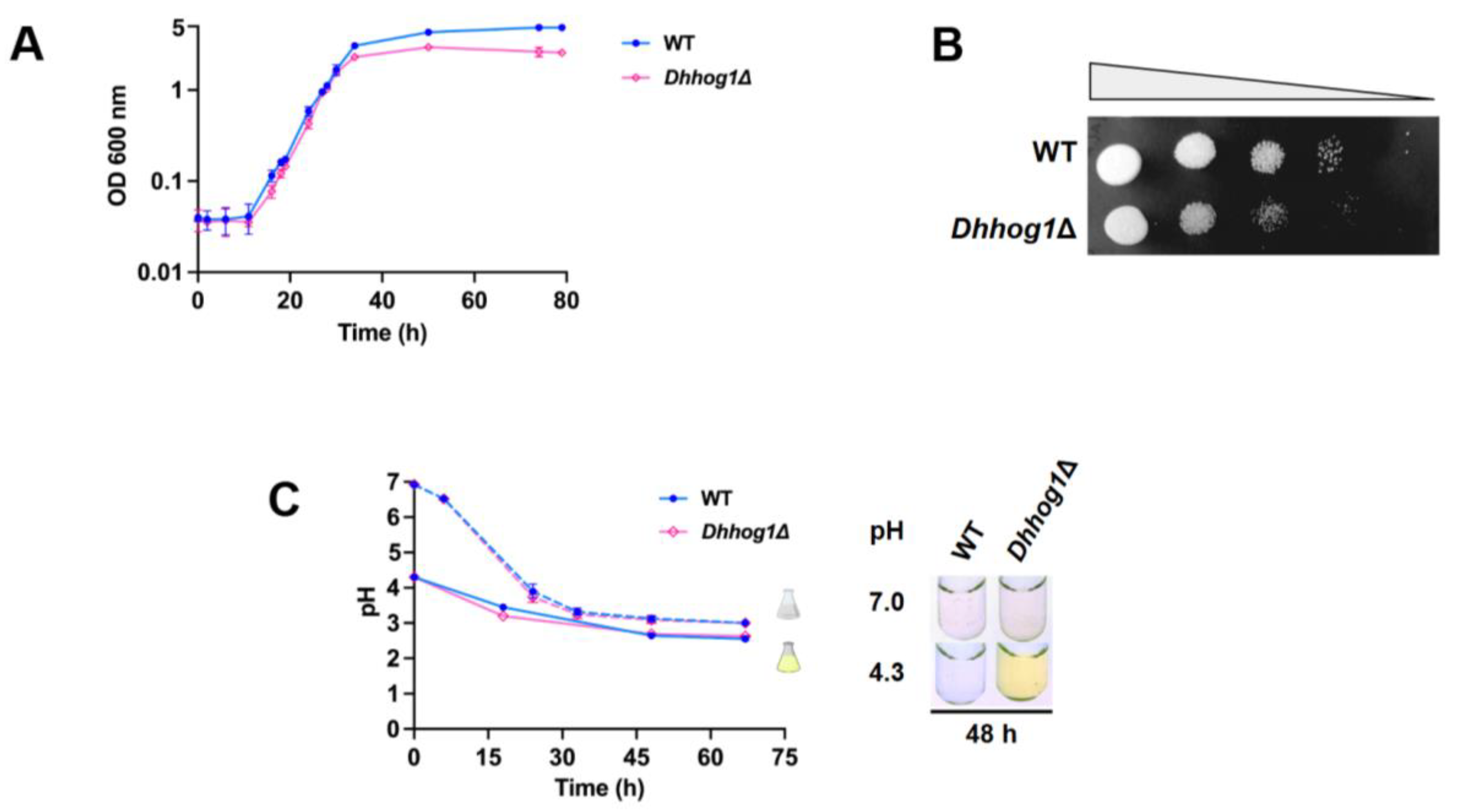

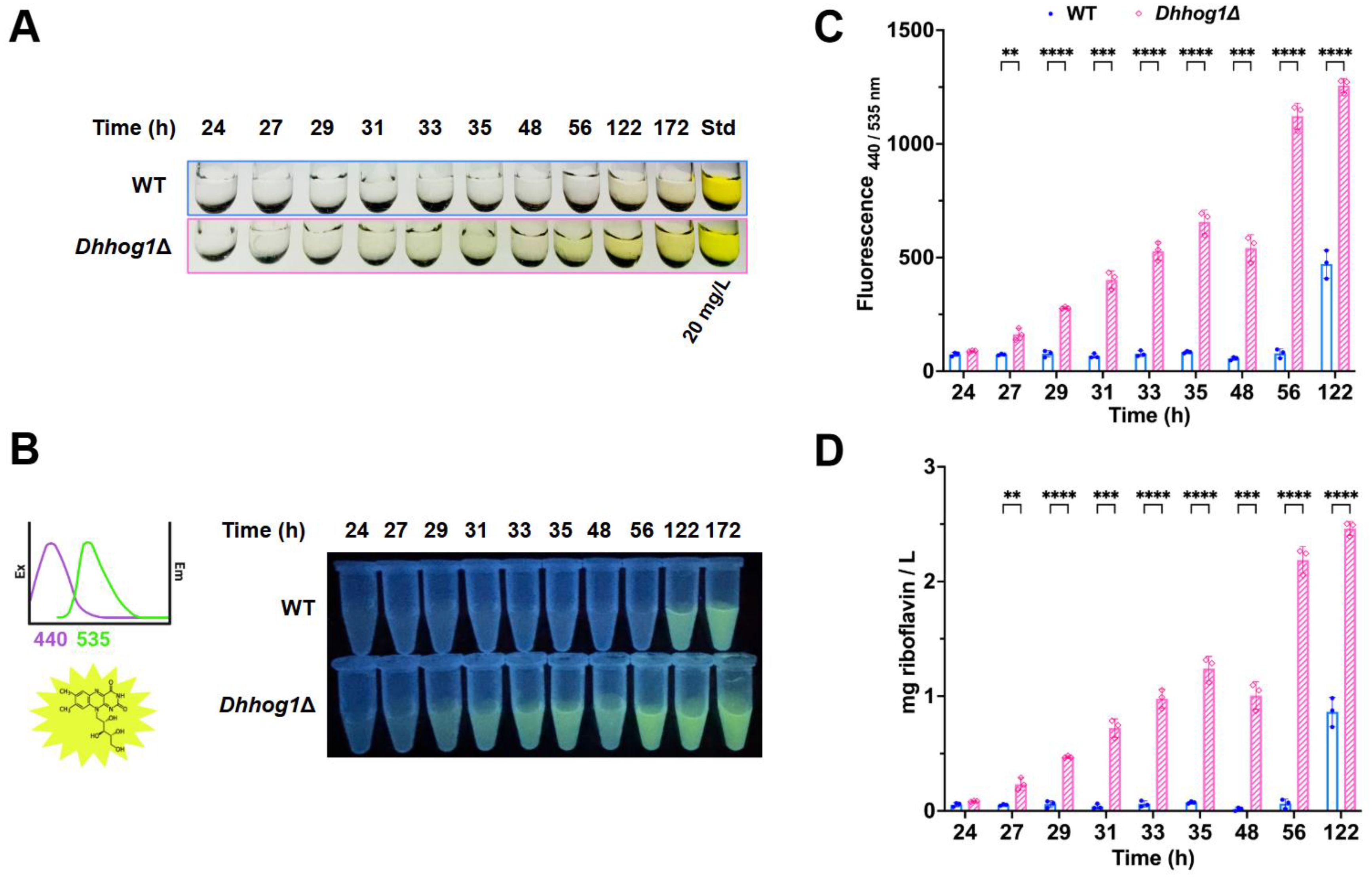

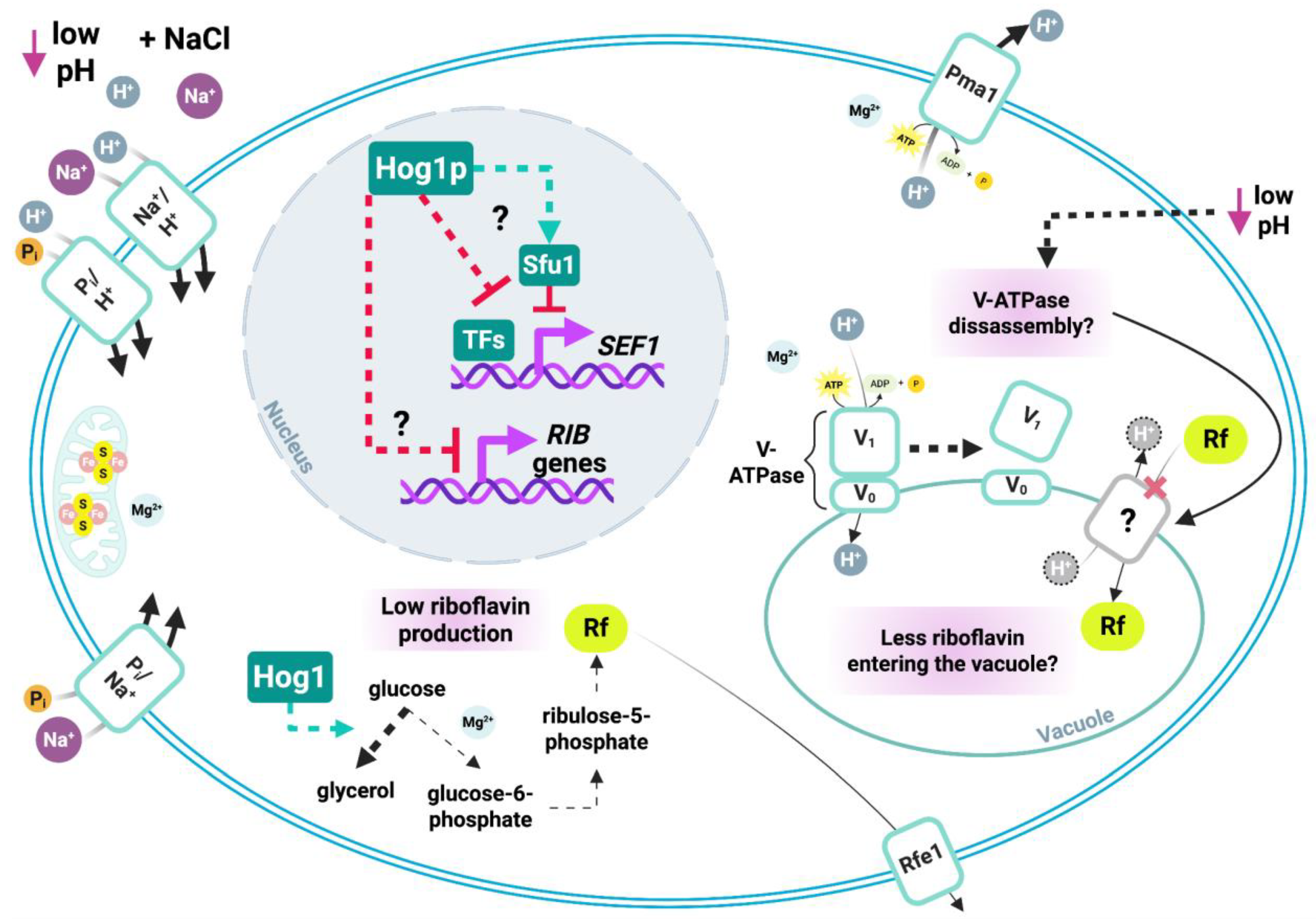

Riboflavin (vitamin B2) is an essential precursor of flavin cofactors involved in redox metabolism, and its industrial production increasingly relies on microbial fermentation. Debaryomyces hansenii (previously as syn. Candida famata) is a halotolerant flavinogenic yeast previously exploited for riboflavin biosynthesis; however, its biotechnological application has been limited by genetic instability and poor understanding of its regulatory networks. Here, we uncover a novel role for the High Osmolarity Glycerol (HOG) pathway in riboflavin metabolism of D. hansenii. Using the first stable knockout mutant (Dhhog1Δ), we demonstrate that loss of DhHog1 triggers early, premature, and enhanced secretion of riboflavin under acidic and saline conditions, visible as a yellow fluorescent pigment in the culture medium. Accelerated riboflavin accumulation in the mutant was accompanied by altered assimilation of phosphorus, sulfur, and magnesium, but not iron, suggesting that regulation extends beyond classical iron limitation. Gene expression analyses showed consistent up-regulation of RIB1, RIB4, and RIB6 genes and derepression of the iron regulator SEF1 in Dhhog1Δ, supporting a model where DhHog1 negatively controls riboflavin biosynthesis through stress-responsive transcription factors and pseudo iron-starvation signaling. Our findings broaden the functional scope of the HOG pathway by linking osmotic stress adaptation with secondary metabolism and establish DhHog1 as a key negative regulator of early riboflavin overproduction and secretion. This work provides new insights into yeast stress-metabolism crosstalk and highlights D. hansenii as a promising platform for metabolic engineering of industrial riboflavin production.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and growth conditions

2.2. Growth curves and pH measurements

2.3. Riboflavin measurements

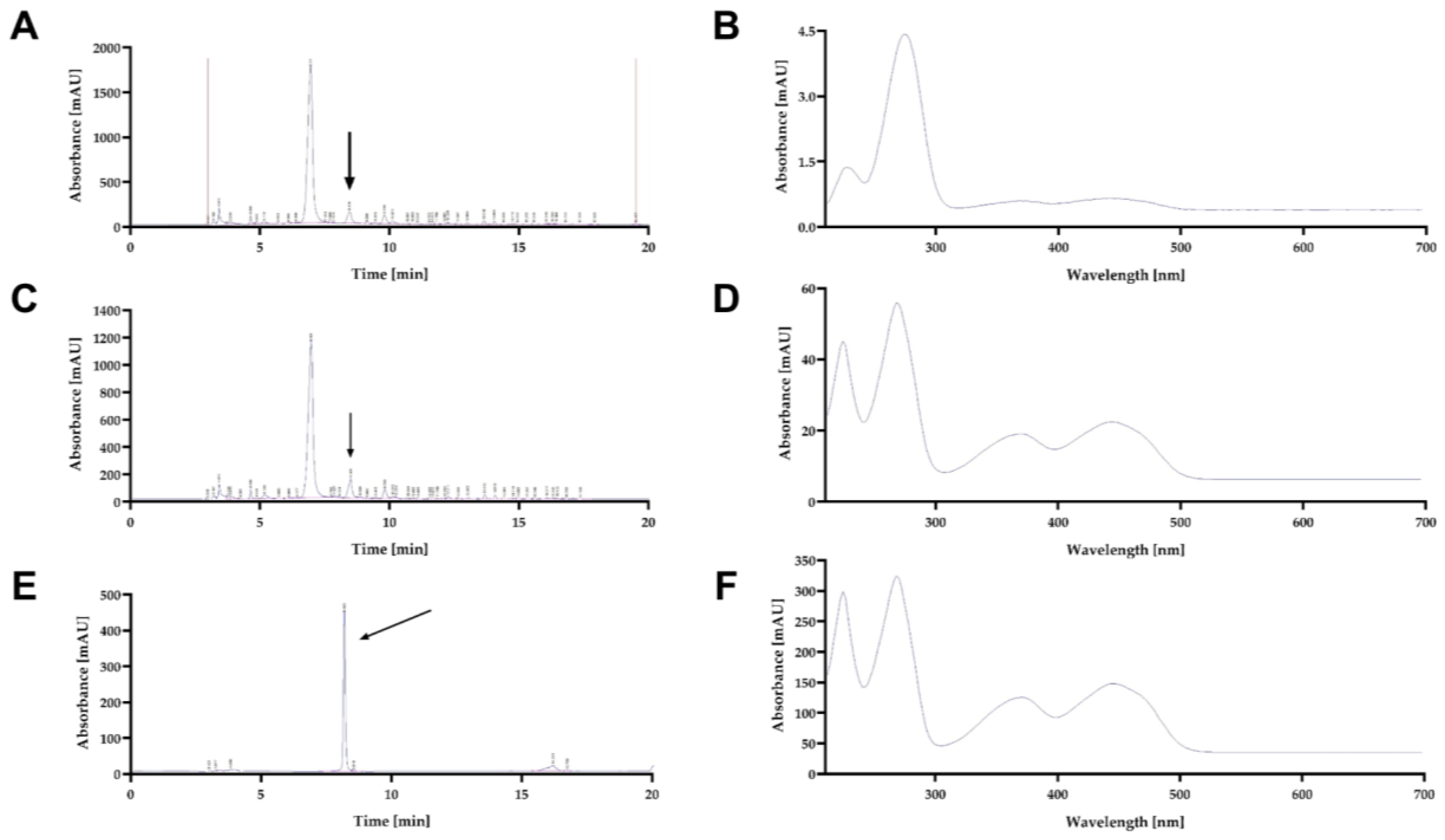

2.4. Riboflavin extraction and RP-HPLC-DAD analysis

2.5. Element analysis

2.6. RNA extraction

2.7. Identification of riboflavin biosynthesis genes

2.8. In silico predictions of transcription factor binding sites

2.9. Analysis of gene expression

2.10. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial low pH induces the excretion and accumulation of riboflavin in D. hansenii

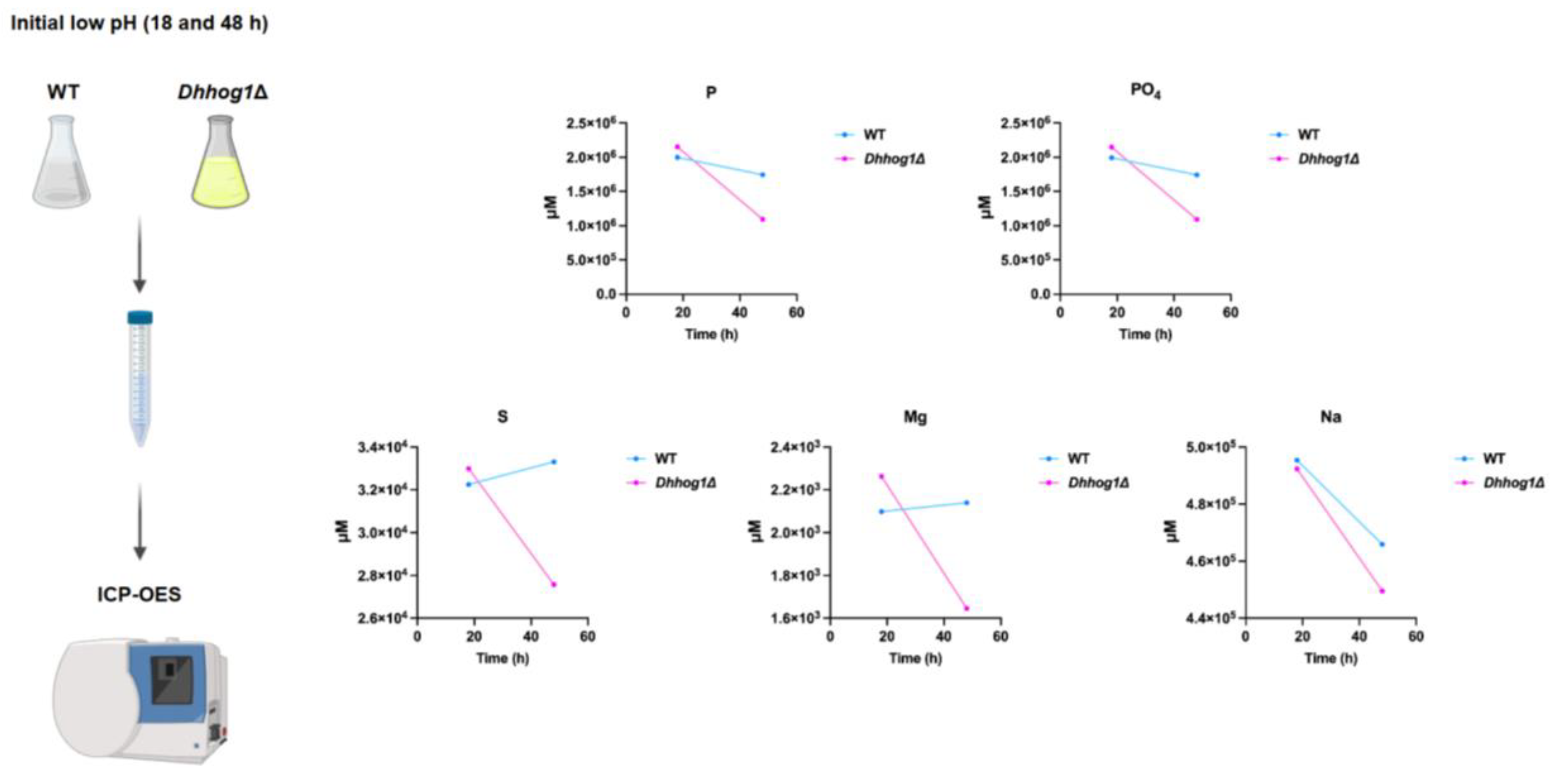

3.2. Accelerated uptake of essential elements in Dhhog1Δ cells

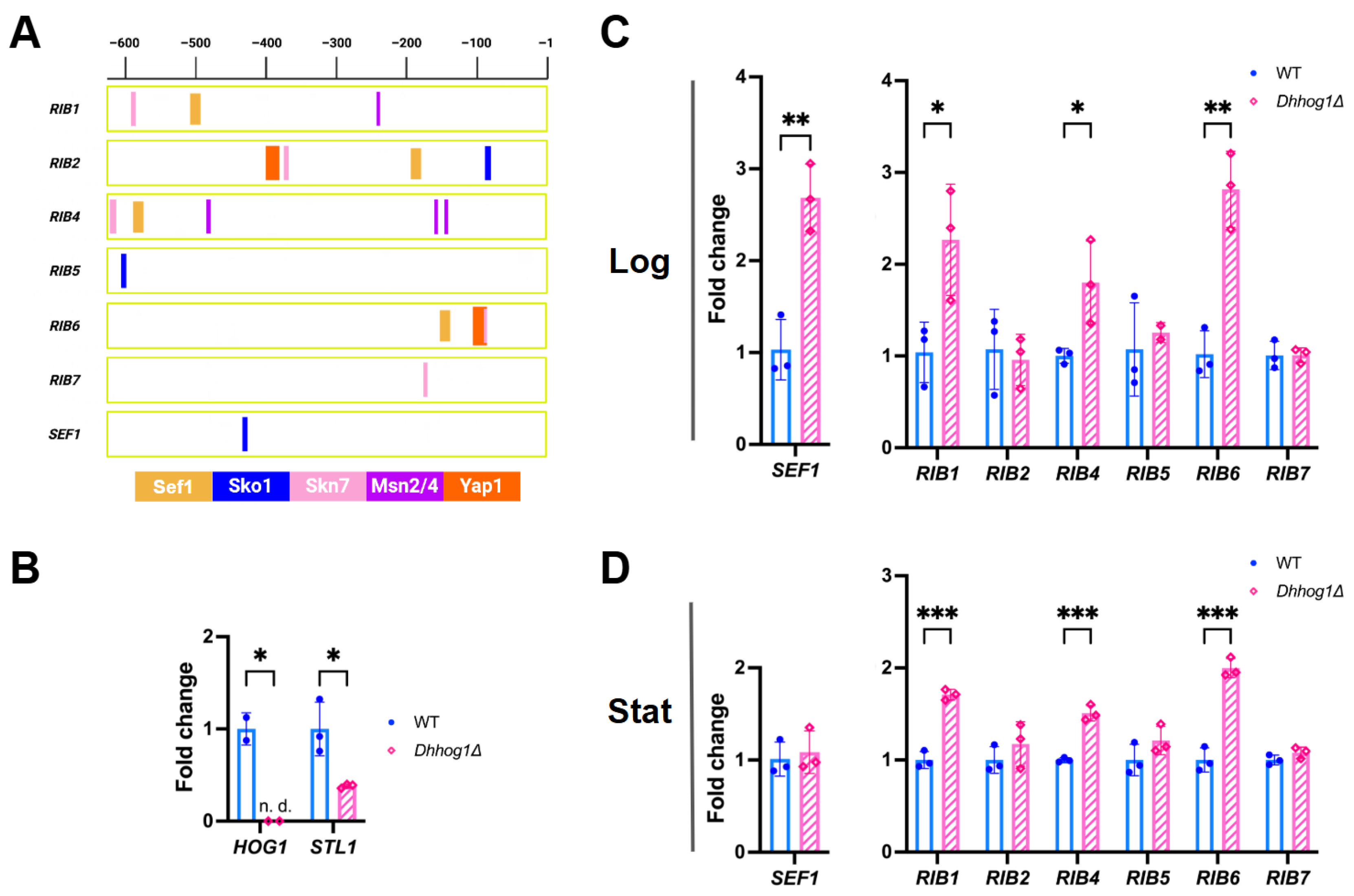

3.3. Riboflavin biosynthesis genes are upregulated in the Dhhog1Δ mutant

4. Discussion

4.1. Conserved riboflavinogenesis in Debaryomyces species and potential repression by DhHog1

4.2. HOG-dependent effects of pH and NaCl on vacuolar dynamics and riboflavin secretion

4.3. HOG signaling and multi-element homeostasis in riboflavin secretion

4.4. Sulfur and phosphate metabolism as key contributors to riboflavin overproduction in the Dhhog1Δ mutant

4.5. DhHog1-mediated negative regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis via stress- and iron-responsive transcription factors

4.6. DhHog1 signaling as a metabolic switch linking carbon and phosphate fluxes to riboflavin biosynthesis

4.7. Concluding remarks and perspectives

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Abbas, C.A.; Sibirny, A.A. Genetic Control of Biosynthesis and Transport of Riboflavin and Flavin Nucleotides and Construction of Robust Biotechnological Producers. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 321–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almagro, A.; Prista, C.; Benito, B.; Loureiro-Dias, M.C.; Ramos, J. Cloning and Expression of Two Genes Coding for Sodium Pumps in the Salt-Tolerant Yeast Debaryomyces hansenii. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 3251–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornrattanapan, P. Riboflavin production by Candida tropicalis isolated from seawater. Sci. Res. Essays 2013, 8, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreieva, Y.; Petrovska, Y.; Lyzak, O.; Liu, W.; Kang, Y.; Dmytruk, K.; Sibirny, A. Role of the regulatory genes SEF1, VMA1 and SFU1 in riboflavin synthesis in the flavinogenic yeast Candida famata (Candida flareri). Yeast 2020, 37, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreieva, Y.; Lyzak, O.; Liu, W.; Kang, Y.; Dmytruk, K.; Sibirny, A. SEF1 and VMA1 Genes Regulate Riboflavin Biosynthesis in the Flavinogenic Yeast Candida famata. Cytol. Genet. 2020, 54, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anraku, Y.; Umemoto, N.; Hirata, R.; Wada, Y. Structure and function of the yeast vacuolar membrane proton ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1989, 21, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auesukaree, C. Molecular mechanisms of the yeast adaptive response and tolerance to stresses encountered during ethanol fermentation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 124, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averianova, L.A.; Balabanova, L.A.; Son, O.M.; Podvolotskaya, A.B.; Tekutyeva, L.A. Production of Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) by Microorganisms: An Overview. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 570828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacher, A.; Eberhardt, S.; Eisenreich, W.; Fischer, M.; Herz, S.; Illarionov, B.; Kis, K.; Richter, G. (2001). Biosynthesis of riboflavin. In Vitamins & Hormones (Vol. 61, pp. 1–49). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, T.; Outten, C.E. (2022). The role of thiols in iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis. In Redox Chemistry and Biology of Thiols (pp. 487–506). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.K.; Mondal, A.K. Isolation and sequence of the HOG1 homologue from Debaryomyces hansenii by complementation of the hog1Δ strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2000, 16, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.F.; Hylemon, P.B. Expression of the bile acid-inducible NADH:flavin oxidoreductase gene of Eubacterium sp. VPI 12708 in Escherichia coli. BBA Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1995, 1249, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, A.A.; Tourtellotte, J.; Niwa, M. Late Phase of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response Pathway Is Regulated by Hog1 MAP Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 17545–17555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, R.C.; Palmer, G.; Beinert, H. Direct Studies on the Electron Transfer Sequence in Xanthine Oxidase by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 1964, 239, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calahorra, M.; Sánchez, N.S.; Peña, A. Activation of fermentation by salts in Debaryomyces hansenii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcí a-Salcedo, R.; Montiel, V.; Calero, F.; Ramos, J. Characterization of DhKHA1, a gene coding for a putative Na+ transporter from Debaryomyces hansenii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007, 7, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Pande, K.; French, S.D.; Tuch, B.B.; Noble, S.M. An Iron Homeostasis Regulatory Circuit with Reciprocal Roles in Candida albicans Commensalism and Pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.S.; Zhu, Z.; McDonald, M.R.; Badiee, M.; Mortimer, I.P.; Leung, A.K.L.; Culotta, V.C. Crosstalk between iron and flavins in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Colmenares, I.; González, J.; Sánchez, N.S.; Ochoa-Gutiérrez, D.; Escobar-Sánchez, V.; Segal-Kischinevzky, C. Regulation of Catalase Expression and Activity by DhHog1 in the Halotolerant Yeast Debaryomyces hansenii Under Saline and Oxidative Conditions. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nadal, E.; Alepuz, P.M.; Posas, F. Dealing with osmostress through MAP kinase activation. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demain, A.L. Riboflavin Oversynthesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1972, 26, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demuyser, L.; Palmans, I.; Vandecruys, P.; Van Dijck, P. Molecular Elucidation of Riboflavin Production and Regulation in Candida albicans, toward a Novel Antifungal Drug Target. mSphere 2020, 5, 00714-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprez, M.-A.; Eskes, E.; Wilms, T.; Ludovico, P.; Winderickx, J. pH homeostasis links the nutrient sensing PKA/TORC1/Sch9 ménage-à-trois to stress tolerance and longevity. Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakov, T.T.; Kane, P.M. Regulation of Vacuolar Proton-translocating ATPase Activity and Assembly by Extracellular pH. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23771–23778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmytruk, K.V.; Abbas, C.A.; Voronovsky, A.Y.; Kshanovska, B.V.; Sybirna, K.A.; Sybirny, A.A. Cloning of structural genes involved in riboflavin synthesis of the yeast Candida famata. Ukr. Biokhim. Zh. 1999, 76, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dmytruk, K.V.; Voronovsky, A.Y.; Sibirny, A.A. Insertion mutagenesis of the yeast Candida famata (Debaryomyces hansenii) by random integration of linear DNA fragments. Curr. Genet. 2006, 50, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytruk, K.V.; Yatsyshyn, V.Y.; Sybirna, N.O.; Fedorovych, D.V.; Sibirny, A.A. Metabolic engineering and classic selection of the yeast Candida famata (Candida flareri) for construction of strains with enhanced riboflavin production. Metab. Eng. 2011, 13, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmytruk, K.; Lyzak, O.; Yatsyshyn, V.; Kluz, M.; Sibirny, V.; Puchalski, C.; Sibirny, A. Construction and fed-batch cultivation of Candida famata with enhanced riboflavin production. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 172, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytruk, K.V.; Ruchala, J.; Fedorovych, D.V.; Ostapiv, R.D.; Sibirny, A.A. Modulation of the Purine Pathway for Riboflavin Production in Flavinogenic Recombinant Strain of the Yeast Candida famata. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 15, 1900468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjalbert, B.; Smith, D.A.; Cornell, M.J.; Alam, I.; Nicholls, S.; Brown, A.J.P.; Quinn, J. Role of the Hog1 Stress-activated Protein Kinase in the Global Transcriptional Response to Stress in the Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 1018–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskes, E.; Deprez, M.-A.; Wilms, T.; Winderickx, J. pH homeostasis in yeast; the phosphate perspective. Curr. Genet. 2018, 64, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorovich, D.; Protchenko, O.; Lesuisse, E. Iron uptake by the yeast Pichia guilliermondii. Flavinogenesis and reductive iron assimilation are co-regulated processes. Biometals 1999, 12, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorovych, D.; Kszeminska, H.; Babjak, L.; Kaszycki, P.; Kołoczek, H. Hexavalent chromium stimulation of riboflavin synthesis in flavinogenic yeast. Biometals 2001, 14, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorovych, D.; Boretsky, V.; Pynyaha, Y.; Bohovych, I.; Boretsky, Y.; Sibirny, A. Cloning of Genes Sef1 and Tup1 Encoding Transcriptional Activator and Global Repressor in the Flavinogenic Yeast Meyerozyma (Candida, Pichia) guilliermondii. Cytol. Genet. 2020, 54, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Sueta, G. (2022). Chemical basis of cysteine reactivity and specificity: Acidity and nucleophilicity. In Redox Chemistry and Biology of Thiols (pp. 19–58). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Frerman, F.E. Acyl-CoA dehydrogenases, electron transfer flavoprotein and electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1988, 16, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadd, G.M.; Edwards, S.W. Heavy-metal-induced flavin production by Debaryomyces hansenii and possible connexions with iron metabolism. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1986, 87, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokbayrak, Z.D.; Patel, D.; Brett, C.L. Acetate and hypertonic stress stimulate vacuole membrane fission using distinct mechanisms. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0271199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.C.; Miranda, I.; Silva, R.M.; Moura, G.R.; Thomas, B.; Akoulitchev, A.; Santos, M.A. A genetic code alteration generates a proteome of high diversity in the human pathogen Candida albicans. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Villarreal-Huerta, D.; Rosas-Paz, M.; Segal-Kischinevzky, C. (2025). Biotechnological Applications of Yeasts Under Extreme Conditions. In P. Buzzini, B. Turchetti, & A. Yurkov (Eds.), Extremophilic Yeasts (pp. 459–501). Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Walvekar, A.S.; Liang, S.; Rashida, Z.; Shah, P.; Laxman, S. A tRNA modification balances carbon and nitrogen metabolism by regulating phosphate homeostasis. eLife 2019, 8, e44795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, I.; Sarge, S.; Illarionov, B.; Laudert, D.; Hohmann, H.; Bacher, A.; Fischer, M. Enzymes from the Haloacid Dehalogenase (HAD) Superfamily Catalyse the Elusive Dephosphorylation Step of Riboflavin Biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 2013, 14, 2272–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, R.; Leroy, C.; Isnard, A.; Labarre, J.; Boy-Marcotte, E.; Toledano, M.B. The control of the yeast H2O2 response by the Msn2/4 transcription factors. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, R.; Ohsumk, Y.; Nakano, A.; Kawasaki, H.; Suzuki, K.; Anraku, Y. Molecular structure of a gene, VMA1, encoding the catalytic subunit of H(+)-translocating adenosine triphosphatase from vacuolar membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 6726–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S. Osmotic Stress Signaling and Osmoadaptation in Yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 300–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S.; Krantz, M.; Nordlander, B. (2007). Yeast Osmoregulation. In Methods in Enzymology (Vol. 428, pp. 29–45). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, S. Control of high osmolarity signalling in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 4025–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.; Pathak, P.; Román, E.; Pla, J.; Panwar, S.L. Adaptation to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Candida albicans Relies on the Activity of the Hog1 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 794855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikner, A.; Shiozaki, K. Yeast signaling pathways in the oxidative stress response. Mutat. Res./Fund. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2005, 569, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Nava, R.A.; Zepeda-Vallejo, L.G.; Santoyo-Tepole, F.; Chávez-Camarillo, G. Ma.; Cristiani-Urbina, E. RP-HPLC Separation and 1H NMR Identification of a Yellow Fluorescent Compound—Riboflavin (Vitamin B2)—Produced by the Yeast Hyphopichia wangnamkhiaoensis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Nava, R.A.; Chávez-Camarillo, G. Ma.; Cristiani-Urbina, E. Kinetics of Riboflavin Production by Hyphopichia wangnamkhiaoensis under Varying Nutritional Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, H.E.; Nimtz, M.; Müller, P.P.; Bilitewski, U. Involvement of the mitogen activated protein kinase Hog1p in the response of Candida albicans to iron availability. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakinuma, Y.; Ohsumi, Y.; Anraku, Y. Properties of H+-translocating adenosine triphosphatase in vacuolar membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 10859–10863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.A.B.; Lesuisse, E.; Stearman, R.; Klausner, R.D.; Dancis, A. Reductive iron uptake by Candida albicans: Role of copper, iron and the TUP1 regulator. Microbiology 2002, 148, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krassowski, T.; Coughlan, A.Y.; Shen, X.-X.; Zhou, X.; Kominek, J.; Opulente, D.A.; Riley, R.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Maheshwari, N.; Shields, D.C.; Kurtzman, C.P.; Hittinger, C.T.; Rokas, A.; Wolfe, K.H. Evolutionary instability of CUG-Leu in the genetic code of budding yeasts. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurabayashi, K.; Enshasy, H.A.E.; Park, E.Y.; Kato, T. Increased production of riboflavin in Ashbya gossypii by endoplasmic reticulum stresses. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, H.; Kaut, A.; Kispal, G.; Lill, R. A mitochondrial ferredoxin is essential for biogenesis of cellular iron-sulfur proteins. PNAS 2000, 97, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.-T. W.; Schneider, K.R.; O’Shea, E.K. A Genetic Study of Signaling Processes for Repression of PHO5 Transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1998, 150, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxman, S.; Sutter, B.M.; Wu, X.; Kumar, S.; Guo, X.; Trudgian, D.C.; Mirzaei, H.; Tu, B.P. Sulfur Amino Acids Regulate Translational Capacity and Metabolic Homeostasis through Modulation of tRNA Thiolation. Cell 2013, 154, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, J.G.; Milani, C.; De Giori, G.S.; Sesma, F.; Van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: A gut microbiota perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-T.; Lee, J.-W.; Lee, D.; Jung, W.-H.; Bahn, Y.-S. A Ferroxidase, Cfo1, Regulates Diverse Environmental Stress Responses of Cryptococcus neoformans through the HOG Pathway. Mycobiol. 2014, 42, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.H.; Choi, J.S.; Park, E.Y. Microbial production of riboflavin using riboflavin overproducers, Ashbya gossypii, Bacillus subtilis, and Candida famata: An overview. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2001, 6, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheroux, P.; Kappes, B.; Ealick, S.E. Flavogenomics – a genomic and structural view of flavin-dependent proteins. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 2625–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoorabadi, S.O.; Thibodeaux, C.J.; Liu, H. The Diverse Roles of Flavin Coenzymes – Nature’s Most Versatile Thespians. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6329–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Wang, K.; Zhao, M.; Xu, T.; Klionsky, D.J. Two MAPK-signaling pathways are required for mitophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell. Biol. 2011, 193, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.S.; Pereira, C.; Canadell, D.; Vilaça, R.; Teixeira, V.; Moradas-Ferreira, P.; De Nadal, E.; Posas, F.; Costa, V. The Hog1p kinase regulates Aft1p transcription factor to control iron accumulation. BBA Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Nanyan, N.S.B.; Takagi, H. Proline Homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: How Does the Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Msn2 Play a Role? Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, A. Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 17205–17208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.; Biswas, D.; Mondal, A.K. Development of host and vector for high-efficiency transformation and gene disruption in Debaryomyces hansenii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montiel, V.; Ramos, J. Intracellular Na+ and K+ distribution in Debaryomyces hansenii. Cloning and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of DhNHX1: Intracellular Na+ and K+ distribution in Debaryomyces hansenii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007, 7, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgunova, E.; Saller, S.; Haase, I.; Cushman, M.; Bacher, A.; Fischer, M.; Ladenstein, R. Lumazine Synthase from Candida albicans as an Anti-fungal Target Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 17231–17241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, C.; Siles, A.; Martí nez, J.L.; Calero, F.; Ramos, J. Oxidative stress sensitivity in Debaryomyces hansenii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, C.; Frost, A.T.; Ramos-Moreno, L.; Krum, M.R.; Martínez, J.L. A physiological characterization in controlled bioreactors reveals a novel survival strategy for Debaryomyces hansenii at high salinity. Yeast 2021, 38, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-V.; Gaillardin, C.; Neuvéglise, C. Differentiation of Debaryomyces hansenii and Candida famata by rRNA gene intergenic spacer fingerprinting and reassessment of phylogenetic relationships among D. hansenii, C. famata, D. fabryi, C. flareri (=D. subglobosus) and D. prosopidis: Description of D. vietnamensis sp. nov. closely related to D. nepalensis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieland, S.; Stahmann, K.-P. A developmental stage of hyphal cells shows riboflavin overproduction instead of sporulation in Ashbya gossypii. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 10143–10153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysten, J.; Van Dijck, P. Can we microbe-manage our vitamin acquisition for better health? PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Gutiérrez, D.; Reyes-Torres, A.M.; De La Fuente-Colmenares, I.; Escobar-Sánchez, V.; González, J.; Ortiz-Hernández, R.; Torres-Ramírez, N.; Segal-Kischinevzky, C. Alternative CUG Codon Usage in the Halotolerant Yeast Debaryomyces hansenii: Gene Expression Profiles Provide New Insights into Ambiguous Translation. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, H. Osmophilic yeasts. Adv. Food Res. 1963, 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Orij, R.; Brul, S.; Smits, G.J. Intracellular pH is a tightly controlled signal in yeast. BBA Gen. Subjects 2011, 1810, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.; Mondo, S.; Pereira, M.; Vieira, É.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Sá-Correia, I. Genome Sequence and Analysis of the Flavinogenic Yeast Candida membranifaciens IST 626. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penninckx, M. An overview on glutathione in Saccharomyces versus non-conventional yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002, 2, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, M.; Kearney, E.B.; Singer, T.P. Transport of riboflavin into yeast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 3221–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovska, Y.; Lyzak, O.; Ruchala, J.; Dmytruk, K.; Sibirny, A. Co-Overexpression of RIB1 and RIB6 Increases Riboflavin Production in the Yeast Candida famata. Fermentation 2022, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posas, F.; Wurgler-Murphy, S.M.; Maeda, T.; Witten, E.A.; Thai, T.C.; Saito, H. Yeast HOG1 MAP Kinase Cascade is Regulated by a Multistep Phosphorelay Mechanism in the SLN1–YPD1–SSK1 “Two-Component” Osmosensor. Cell 1996, 86, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prista, C.; Michán, C.; Miranda, I.M.; Ramos, J. The halotolerant Debaryomyces hansenii, the Cinderella of non-conventional yeasts. Yeast 2016, 33, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proft, M.; Struhl, K. Hog1 Kinase Converts the Sko1-Cyc8-Tup1 Repressor Complex into an Activator that Recruits SAGA and SWI/SNF in Response to Osmotic Stress. Mol. Cell 2002, 9, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proft, M.; Struhl, K. MAP Kinase-Mediated Stress Relief that Precedes and Regulates the Timing of Transcriptional Induction. Cell 2004, 118, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.-F.; Kerrest, A.; Lafontaine, I.; Dujon, B. Comparative Genomics of Hemiascomycete Yeasts: Genes Involved in DNA Replication, Repair, and Recombination. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ror, S.; and Panwar, S.L. Sef1-Regulated Iron Regulon Responds to Mitochondria-Dependent Iron–Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis in Candida albicans. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchala, J.; Andreieva, Y.A.; Tsyrulnyk, A.O.; Sobchuk, S.M.; Najdecka, A.; Wen, L.; Kang, Y.; Dmytruk, O.V.; Dmytruk, K.V.; Fedorovych, D.V.; Sibirny, A.A. Cheese whey supports high riboflavin synthesis by the engineered strains of the flavinogenic yeast Candida famata. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchala, J.; Najdecka, A.; Wojdyla, D.; Liu, W.; Sibirny, A. Regulation of Riboflavin Biosynthesis in Microorganisms and Construction of the Advanced Overproducers of this Vitamin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pérez, F.S.; Ruiz-Castilla, F.J.; Leal, C.; Martínez, J.L.; Ramos, J. Sodium and lithium exert differential effects on the central carbon metabolism of Debaryomyces hansenii through the glyoxylate shunt regulation. Yeast 2023, 40, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, N.; Rawat, R.; Thornburg, C.; Walker, K.D.; Roje, S. Identification and characterization of the missing phosphatase on the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2016, 88, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, M.S.; Purushotham, R.; Kaur, R. The Hog1 MAPK substrate governs Candida glabrata-epithelial cell adhesion via the histone H2A variant. PLOS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Posas, F. Response to Hyperosmotic Stress. Genet. 2012, 192, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N.S.; Arreguí n, R.; Calahorra, M.; Peña, A. Effects of salts on aerobic metabolism of Debaryomyces hansenii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, N.S.; Calahorra, M.; González, J.; Defosse, T.; Papon, N.; Peña, A.; Coria, R. Contribution of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1 to the halotolerance of the marine yeast Debaryomyces hansenii. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.O.; Silva, P.G.P.; Lemos Junior, W.J.F.; De Oliveira, V.S.; Anschau, A. Glutathione production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 1879–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarge, S.; Haase, I.; Illarionov, B.; Laudert, D.; Hohmann, H.; Bacher, A.; Fischer, M. Catalysis of an Essential Step in Vitamin B2 Biosynthesis by a Consortium of Broad Spectrum Hydrolases. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 2466–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlösser, T.; Gätgens, C.; Weber, U.; Stahmann, K. -Peter. Alanine: Glyoxylate aminotransferase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae –encoding gene AGX1 and metabolic significance. Yeast 2004, 21, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.E.; Brown, T.A.; Trumpower, B.L. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 3091–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, S.K.; Park, E.Y.; Revuelta, J.L.; Becker, J.; Wittmann, C. Biotechnology of riboflavin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2107–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seda-Miró, J.M.; Arroyo-González, N.; Pérez-Matos, A.; Govind, N.S. Impairment of cobalt-induced riboflavin biosynthesis in a Debaryomyces hansenii mutant. Can. J. Microbiol. 2007, 53, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal-Kischinevzky, C.; Romero-Aguilar, L.; Alcaraz, L.D.; López-Ortiz, G.; Martínez-Castillo, B.; Torres-Ramírez, N.; Sandoval, G.; González, J. Yeasts Inhabiting Extreme Environments and their Biotechnological Applications. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Separovich, R.J.; Karakatsanis, N.M.; Gao, K.; Fuh, D.; Hamey, J.J.; Wilkins, M.R. Proline-directed yeast and human MAP kinases phosphorylate the Dot1p/ DOT1L histone H3K79 methyltransferase. The FEBS J. 2024, 291, 2590–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Riboflavin Vitamin B2 Market Report 2025 (Global Edition). 2025. Available online: https://www.cognitivemarketresearch.com/vitamin-b2-riboflavin-market-report (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Silva, R.; Aguiar, T.Q.; Oliveira, R.; Domingues, L. Light exposure during growth increases riboflavin production, ROS accumulation and DNA damage in Ashbya gossypii riboflavin-overproducing strains. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, M.S.; Binkley, J.; Binkley, G.; Miyasato, S.R.; Simison, M.; Sherlock, G. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): Incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D592–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, V.K.; Suneetha, K.J.; Kaur, R. The mitogen-activated protein kinase CgHog1 is required for iron homeostasis, adherence and virulence in Candida glabrata. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2142–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahmann, K.-P.; Revuelta, J.L.; Seulberger, H. Three biotechnical processes using Ashbya gossypii, Candida famata, or Bacillus subtilis compete with chemical riboflavin production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 53, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahmann, K. -Peter, Arst, H.N.; Althöfer, H.; Revuelta, J.L.; Monschau, N.; Schlüpen, C.; Gätgens, C.; Wiesenburg, A.; Schlösser, T. Riboflavin, overproduced during sporulation of Ashbya gossypii, protects its hyaline spores against ultraviolet light. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, J.-K.; Poulsen, L.L.; Ziegler, D.M.; Robertus, J.D. Molecular Cloning and Kinetic Characterization of a Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 336, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sychrová, H.; Ramı́rez, J.; Peña, A. Involvement of Nha1 antiporter in regulation of intracellular pH in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 171, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, Y.; Noguchi, T. Characteristics of alanine: Glyoxylate aminotransferase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a regulatory enzyme in the glyoxylate pathway of glycine and serine biosynthesis from tricarboxylic acid-cycle intermediates. Biochem. J. 1985, 231, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Roman, E.; Claypool, S.; Manzoor, N.; Pla, J.; Panwar, S.L. Mitochondria Influence CDR1 Efflux Pump Activity, Hog1-Mediated Oxidative Stress Pathway, Iron Homeostasis, and Ergosterol Levels in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 5580–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Quiroz, F.; García-Marqués, S.; Coria, R.; Randez-Gil, F.; Prieto, J.A. The Activity of Yeast Hog1 MAPK Is Required during Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Induced by Tunicamycin Exposure. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 20088–20096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyrulnyk, A.O.; Fedorovych, D.V.; Dmytruk, K.V.; Sibirny, A.A. (2021). Overexpression of Riboflavin Excretase Enhances Riboflavin Production in the Yeast Candida famata. In M. Barile (Ed.), Flavins and Flavoproteins (Vol. 2280, pp. 31–42). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Turatsinze, J.-V.; Thomas-Chollier, M.; Defrance, M.; van Helden, J. Using RSAT to scan genome sequences for transcription factor binding sites and cis-regulatory modules. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandamme, E.J. Production of vitamins, coenzymes and related biochemicals by biotechnological processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1992, 53, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanetti, M.C.D.; Aquarone, E. Riboflavin excretion by Pachysolen tannophilus grown in synthetic medium supplemented with d-xylose. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1992, 8, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkova, K.; Sychrova, H. The Debaryomyces hansenii NHA1 gene encodes a plasma membrane alkali-metal-cation antiporter with broad substrate specificity. Gene 2006, 369, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voronovsky, A.; Abbas, C.; Fayura, L.; Kshanovska, B.; Dmytruk, K.; Sybirna, K.; Sibirny, A. Development of a transformation system for the flavinogenic yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002, 2, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronovsky, A.Y.; Abbas, C.A.; Dmytruk, K.V.; Ishchuk, O.P.; Kshanovska, B.V.; Sybirna, K.A.; Gaillardin, C.; Sibirny, A.A. Candida famata (Debaryomyces hansenii) DNA sequences containing genes involved in riboflavin synthesis. Yeast 2004, 21, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, G.M. The Roles of Magnesium in Biotechnology. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1994, 14, 311–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.T.; Wencewicz, T.A. Flavoenzymes: Versatile catalysts in biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walvekar, A.S.; Srinivasan, R.; Gupta, R.; Laxman, S. Methionine coordinates a hierarchically organized anabolic program enabling proliferation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2018, 29, 3183–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webert, H.; Freibert, S.-A.; Gallo, A.; Heidenreich, T.; Linne, U.; Amlacher, S.; Hurt, E.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Banci, L.; Lill, R. Functional reconstitution of mitochondrial Fe/S cluster synthesis on Isu1 reveals the involvement of ferredoxin. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, S.J.; Li, Z.; Nakagawa, C.L.; Collins, J.H.; Young, E.M. Oleaginous Yeast Biology Elucidated With Comparative Transcriptomics. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2025, 122, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaakoub, H.; Mina, S.; Calenda, A.; Bouchara, J.-P.; Papon, N. Oxidative stress response pathways in fungi. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | ID, ORF |

Fw 5’ → 3’ | Rv 5’ → 3’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| DhACT1 | 2901278, DEHA2D05412g |

CCCAGAAGAACACCCAGTTT | CGGCTTGGATAGAAACGTAGAA |

| DhRIB1 | 2899385, DEHA2A12870g |

AAGACACCCTGCTGATGGTC | TGTCGGGGTTGTTGGTCAAT |

| DhRIB2 | 2902834, DEHA2E11374g |

TGGAACCATGCTCCTTGAGATT | CTGGCTCCACAACACCAACA |

| DhRIB4 | 2901083, DEHA2D04180g |

TGTTTGACCGATGAGCAAGC | ACACATTTCGACAGCAGCAG |

| DhRIB5 | 2901307, DEHA2D13926g |

GCCTGGGTGTAACTGACCAT | GGAGAAGGGGTTCATTGCCA |

| DhRIB6 | 2904849, DEHA2G09504g |

TGGTCTTATGAAGTCTACCGGC | TATGCTGATGGCACGACCAC |

| DhRIB7 | 2904875, DEHA2G10010g |

ACTTGCACCTCCTTCAACCAT | GGTGCATTTGTCAGGCTTCC |

| DhSEF1 | 2900038, DEHA2C16676g |

CCGTTTGCTTCGACCCTTTA | CTGCCAACAATGCTACCGTG |

| DhSTL1 | 2902951, DEHA2E01364g |

TGGGAATGGCTGACACTTATG | GCTCTTCTACCCAACCTATCAATC |

| DhHOG1 | 2902985, DEHA2E20944g |

AACCGCTCGCTGAATGGAAT | TCTCCACCTCCAGACGTGAT |

| Protein name, Identifier |

S. cerevisiae | C. albicans | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity (%) | Query cover (%) | Similarity (%) | Query cover (%) | |

|

DhRib1, DEHA2A12870p |

77 | 80 | 85 | 92 |

|

DhRib2, DEHA2E11374p |

73 | 86 | 80 | 100 |

|

DhRib4, DEHA2D04180p |

83 | 99 | 95 | 100 |

|

DhRib5, DEHA2D13926p |

73 | 98 | 82 | 100 |

|

DhRib6, DEHA2G09504p |

73 | 98 | 88 | 100 |

|

DhRib7, DEHA2G10010p |

62 | 100 | 65 | 100 |

|

DhSef1, DEHA2C16676p |

67 | 76 | 70 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).