1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) has positioned itself as a global leader in climate policy, underpinned by ambitious frameworks such as the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 package. These initiatives articulate a strong normative vision for rapid decarbonisation, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, accelerate the adoption of renewable energy, and phase out fossil fuels. However, the extent to which these political commitments translate into measurable behavioural and structural changes at the national level remains a critical and underexplored question.

This study addresses the growing need to empirically assess whether EU Member States are aligning their actual energy transition trajectories with the rhetoric of climate ambition. While much of the policy discourse highlights progress, particularly in setting targets and mobilising green investments, the empirical reality is often more fragmented. National-level energy behaviours, especially patterns of fossil fuel consumption, may not always reflect the transformative narratives promoted at the EU level.

Using machine learning techniques to analyse recent fuel consumption data, this paper investigates the extent and consistency of national decarbonisation signals. Beyond identifying general downward trends, the study incorporates slope acceleration metrics and label reversals to reveal nuanced patterns, such as rebound effects and temporal inconsistency, that are often overlooked in policy assessments. The findings suggest that while some Member States are indeed reducing their reliance on fossil fuels, others display stagnation or reversal, indicating a partial and asymmetric translation of policy into behaviour.

In highlighting the gap between discourse and data, this research contributes to a more grounded understanding of the EU’s energy transition. It underscores the need for continuous, multidimensional monitoring and cautions against conflating aspirational narratives with material outcomes. Such analysis is vital for recalibrating policy instruments, improving accountability, and ensuring that green commitments are not merely symbolic but structurally embedded.

2. Literature Review

While extensive research has been conducted on the evolution of EU climate governance and the design of its flagship policies, less attention has been given to the empirical evaluation of how these commitments translate into tangible energy transition behaviours. Existing literature tends to focus either on policy analysis or energy statistics in isolation, creating a methodological and analytical gap. This study aims to bridge this divide by applying machine learning methods to national-level fossil fuel consumption data, thereby contributing to a more integrated understanding of the alignment between rhetoric and reality within the EU energy transition.

2.1. EU Climate Governance and Fossil Fuel Policy Instruments

The European Union (EU) has established a robust framework to govern climate policies, specifically targeting fossil fuel consumption to mitigate climate change and promote sustainable energy practices. This governance architecture has evolved significantly, characterised by a combination of hard and soft policy instruments that engage member states in a multi-level governance framework. This literature review synthesises key contributions to understanding the relationship between European Union (EU) climate governance and fossil fuel policy instruments [

1,

2].

Central to the EU’s climate governance are legally binding frameworks and policy mechanisms, such as the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the European Green Deal (EGD). The ETS, established in 2005 and expanded through subsequent revisions, sets a cap on emissions and allows for trading among member states to incentivise reductions in fossil fuel consumption [

3].

According to Knodt, the ETS has emerged as a critical ‘hard governance’ mechanism, covering approximately 45% of total EU emissions, thereby placing significant constraints on fossil fuel usage while promoting the integration of renewable energy sources [

4,

5].

The EGD represents a comprehensive approach to achieving climate neutrality by 2050, setting ambitious targets that shape the energy landscape across EU member states [

6,

7].

Moreover, the EU’s governance structure encompasses a mix of soft law strategies, increasingly complemented by stringent reporting and accountability frameworks. As noted by Schoenefeld and Jordan, the EU’s climate policies contain elements of ‘harder’ governance due to evolving monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, enhancing their effectiveness and the accountability of member states in meeting climate goals [

8].

The incorporation of national energy and climate plans (NECPs), required from each member state under the governance regulations, exemplifies how the EU strives for coherence across diverse political landscapes [

9,

10].

The integration of climate and energy policies through the Energy Union strategy underscores the necessity for coordinated action among member states. Szulecki and Claes advocate for a better understanding of the overlaps between energy governance and climate objectives, emphasising the role of national policies in shaping EU legislative outcomes [

11].

Member states, particularly those with strong economies like Germany, have been influential in guiding EU climate ambitions, although their policies are often reinforced by EU frameworks that encourage cross-border cooperation [

12].

Achieving the EU’s climate objectives necessitates collaboration and convergence among national policies within the broader EU agenda.

Challenges remain as the EU navigates the complex interplay between political will, energy security, and public acceptance of transformative energy policies. Geopolitical shifts, such as the war in Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis, have prompted urgent re-evaluations of fossil fuel dependency across Europe [

13].

These developments highlight vulnerabilities in energy supply chains and reinforce the need for the EU to expedite its transition to sustainable energy systems [

14].

The EU’s capacity to pivot effectively in response to external pressures will be crucial in fulfilling its climate commitments, necessitating resilient governance frameworks that can adapt to dynamic political and economic environments [

15,

16].

2.2. From Policy Rhetoric to Policy Implementation

A primary challenge in integrating long-term perspectives is the inherent tension between energy security and climate objectives. The EU’s governance structure, which is influenced by the diverse interests and sovereignty of its member states, often prioritises immediate concerns, such as energy supply stability, over comprehensive decarbonisation objectives. Aalto and Temel underscore the reluctance of member states to relinquish control over energy sources and strategies, resulting in fragmented energy policymaking that hampers cohesive long-term planning [

17].

This situation is exemplified by the ongoing geopolitical considerations that affect EU-Russian energy relations, highlighting how external crises can shift policy focus away from long-term sustainability goals [

18].

Moreover, the governance of energy efficiency remains a pivotal aspect of the EU’s energy policies. The Energy Efficiency Directive emphasises the need for member states to be held accountable for achieving specified energy reduction targets [

19].

However, integrating energy efficiency measures into long-term energy strategies often encounters barriers related to under-investment and political opposition, particularly when short-term economic interests conflict with environmental sustainability [

20].

As Galán-Martín et al. indicate that delays in deploying innovative technologies, such as Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), could jeopardise the EU’s long-term climate goals, underscoring the urgency of immediate action alongside strategic foresight [

21].

The integration of new technologies, such as renewable energy sources and energy storage systems, must be strategically planned to align with the EU’s decarbonisation targets. Findings from Oberthür reveal that while current policies may have a short-sighted focus, there is an ongoing discourse aimed at enhancing the long-term viability of these initiatives [

22,

23].

The push for a comprehensive legal and institutional framework designed to facilitate renewable energy integration illustrates an effort to transcend immediate challenges in favour of sustainable long-term development [

24].

Furthermore, the short-termism prevalent in EU energy and climate policies has been critiqued for undermining the effectiveness of long-term strategies. Gheuens and Oberthür argue that a myopic focus on immediate goals leads to policies that may not fully reflect the science-based needs for long-term decarbonisation [

25].

This discrepancy highlights the necessity for policies that not only meet immediate targets but also adapt to evolving scientific insights regarding climate change.

The complexity of achieving a cohesive energy strategy in the EU is exacerbated by the need for coordination among various stakeholders, including national governments, private sector actors, and civil society [

26].

The varying degrees of commitment and capacity among member states to implement long-term energy policies can hinder progress. For instance, member states might prioritise financial stability and energy security over the bold measures required for environmental sustainability [

27,

28].

In conclusion, integrating long-term perspectives into EU energy governance poses significant challenges, ranging from geopolitical influences to the complexities of member state sovereignty and investment priorities. To effectively navigate these obstacles, a concerted effort is needed to align short-term actions with long-term climate goals. The ongoing evaluation of current policies and frameworks, such as the Energy Efficiency Directive and the European Green Deal, will be crucial to ensuring that the EU not only meets its immediate energy needs but also paves the way for a sustainable future.

2.3. Empirical Approaches to Energy Transition Monitoring

In the context of transitioning to renewable energy, the empirical monitoring of energy transition processes is crucial for effective governance and policy implementation. This literature review examines empirical approaches to monitoring energy transitions, with a focus on evaluating frameworks that can accurately capture the complexities and multidimensional aspects of energy consumption and production.

A significant challenge in monitoring energy transitions is the need for multifaceted evaluation methods that account for various influential factors. Gałecka and Pyra advocate for a comprehensive framework that looks beyond single indicators, emphasising the necessity to incorporate a wide array of variables that impact energy consumption patterns [

29].

Their analysis responds to the requirements identified by other scholars who suggest that monitoring progress in the energy transition necessitates a multifaceted approach that considers multidimensional variables.

As nations grapple with the transitional dynamics, there is a clear recognition of the continued importance of fossil fuels during this shift. Phan highlights that, despite the rise of renewables, oil and gas are projected to play a critical role in the immediate term [

30].

This reality necessitates monitoring frameworks that not only consider the penetration of renewables but also account for the ongoing reliance on traditional energy sources. Innovative approaches that allow for dynamic management of energy resources can provide insights into how the transition may influence energy markets and consumption patterns over time.

Technological innovation also emerges as a vital element in the transition process. Lukashevych et al. discuss the need for novel technical solutions in managing renewable energy variability [

31].

Monitoring frameworks should include metrics that capture technological advancements, as they significantly influence the stability and reliability of renewable energy supply. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in the monitoring process offers promising prospects for enhanced data analysis and predictive modelling, allowing policymakers to make informed decisions that reflect current trends and uncertainties in energy use [

32]. Equity and justice considerations also play a crucial role in energy transitions, as highlighted by Jacome et al. [

33].

The evaluation of energy justice metrics can illuminate disparities in the distribution of benefits and burdens among communities. Establishing quantifiable goals related to energy equity can enhance accountability and transparency in energy transition policy, ensuring that marginalised groups are not left behind during this pivotal shift. The analytical frameworks proposed by such studies can help policymakers track justice-related outcomes and inform equitable energy initiatives.

Moreover, comprehensive and targeted instrument mixes are crucial for stimulating effective energy transitions. Rosenow et al. emphasise the need for diverse public policy interventions that steer transitions toward climate goals [

34].

Their findings suggest that a tailored mixture of instruments can enhance energy efficiency and facilitate the uptake of renewable technologies, promoting quicker transitions. Continuous monitoring of the effects of this policy instruments can provide valuable feedback that can be used to adjust strategies in real-time.

Lastly, accountability mechanisms are integral to the success of energy transition initiatives. Sareen discusses cross-sectoral metrics as tools for accountability in the context of integrating energy systems [

35].

Implementing these metrics can foster transparent monitoring and delineate the interactions between energy systems, thereby providing a more integrated view of the transition process.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Scope

This study employs a mixed-methods, data-driven approach to assess the degree to which the fossil fuel consumption behaviours of EU Member States align with the bloc’s climate policy rhetoric. The primary objective is to determine whether observable decarbonization trends align with political commitments outlined in instruments such as the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 packages. The analysis is based on national-level time-series data on fossil fuel consumption, disaggregated by fuel type (gas, liquid, solid), across a sample of EU countries. Two temporal windows are analysed: a long-term historical window (covering the whole available series for each country) and a short-term window (capturing the most recent five-year period). This dual-window design enables a comparative assessment of structural versus recent behavioural changes.

3.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

The primary dataset includes annual energy consumption figures (in kilotonnes of oil equivalent, ktoe) obtained from authoritative sources such as Eurostat and national energy agencies. Fossil fuel consumption is broken down into three categories: Gas (natural gas and derived gases), Liquid fuels (primarily petroleum and oil products), and Solid fuels (including coal and lignite). All-time series were normalised and detrended where necessary to reduce baseline bias between countries with different absolute consumption levels.

3.3. Feature Engineering and Trend Diagnostics

For each country and fuel type, a set of quantitative features was derived to capture the shape and dynamics of energy use trajectories: (1) Slope (trend gradient): Linear regression coefficient over each time window, (2) Delta (net change): Total change in ktoe between window start and end, (3) Variance and volatility indicators: Standard deviation of annual changes and (4), Recent acceleration: Difference in slope between recent and historical windows. These features served both as inputs for classification models and for interpretive diagnostics, such as slope differential analysis. This allowed the study not only to categorise countries but also to assess transition momentum and reversibility.

3.4. Classification Modelling with Machine Learning

A supervised machine learning approach was applied using a Random Forest classifier, chosen for its robustness to nonlinearities and its capacity to handle small datasets with high dimensionality. Countries were labelled as:

- 1 (Greening): Significant decline in fossil fuel use across the majority of indicators

- 0 (Not Greening): Stagnation or increase in one or more key fuel types

The model was trained separately on the historical and recent time windows to identify both long-term transition status and emerging trends. Performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with special attention given to the interpretation of the confusion matrix due to class imbalance. To assess model transparency and interpretability, feature importance scores were extracted using both Gini impurity and permutation-based metrics.

3.5. Temporal Classification Comparison and Label Reversal Detection

A key analytical innovation of this study is the identification of classification label reversals —cases where a country’s predicted status changed between the historical and recent models. These reversals are used as empirical markers of transition volatility, signalling either acceleration (positive shift) or deceleration (negative shift) in energy behaviour.

Additionally, a slope differential metric was calculated to quantify the rate of change over time:

This metric is visualised across countries and fuel types to detect latent acceleration or rebound effects and to supplement binary classification with a richer picture of behavioural dynamics.

4. Results

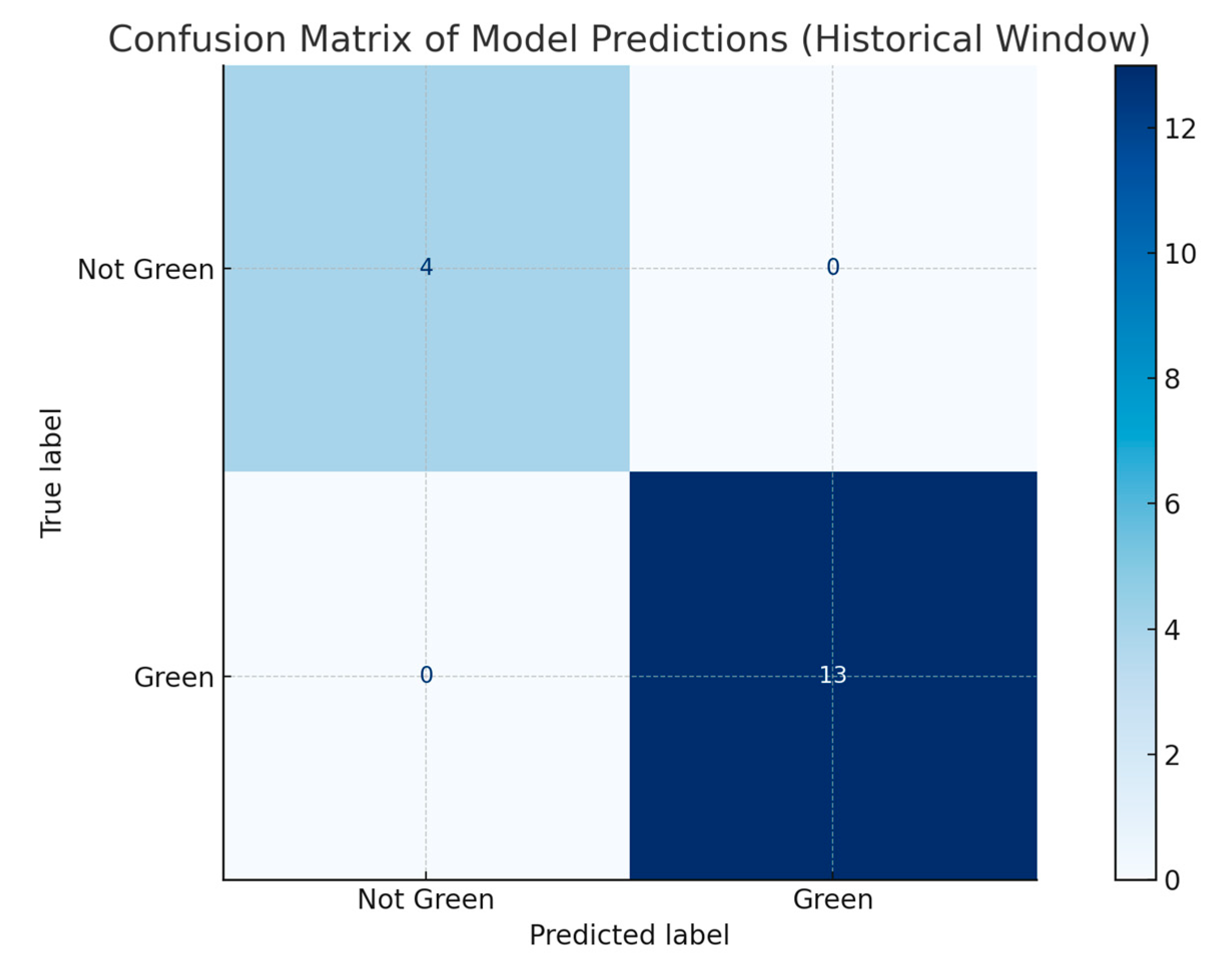

4.1. Classification Performance of the Green Transition Model

To assess the extent to which EU countries are undergoing structural decarbonisation, a Random Forest classifier was trained on time-series features representing fossil fuel consumption trends. The model achieved an overall accuracy of 66.7% in predicting transition status based on historical patterns, with an F1-score of 0.80 for countries exhibiting “green” behaviour (

Table 1).

However, the classification performance for the “not greening” class was poor, primarily due to class imbalance in the dataset—most countries showed at least some reduction, which skewed the distribution. Precision and recall for the “not greening” class were both 0.00, suggesting a need for more balanced training data or resampling strategies.

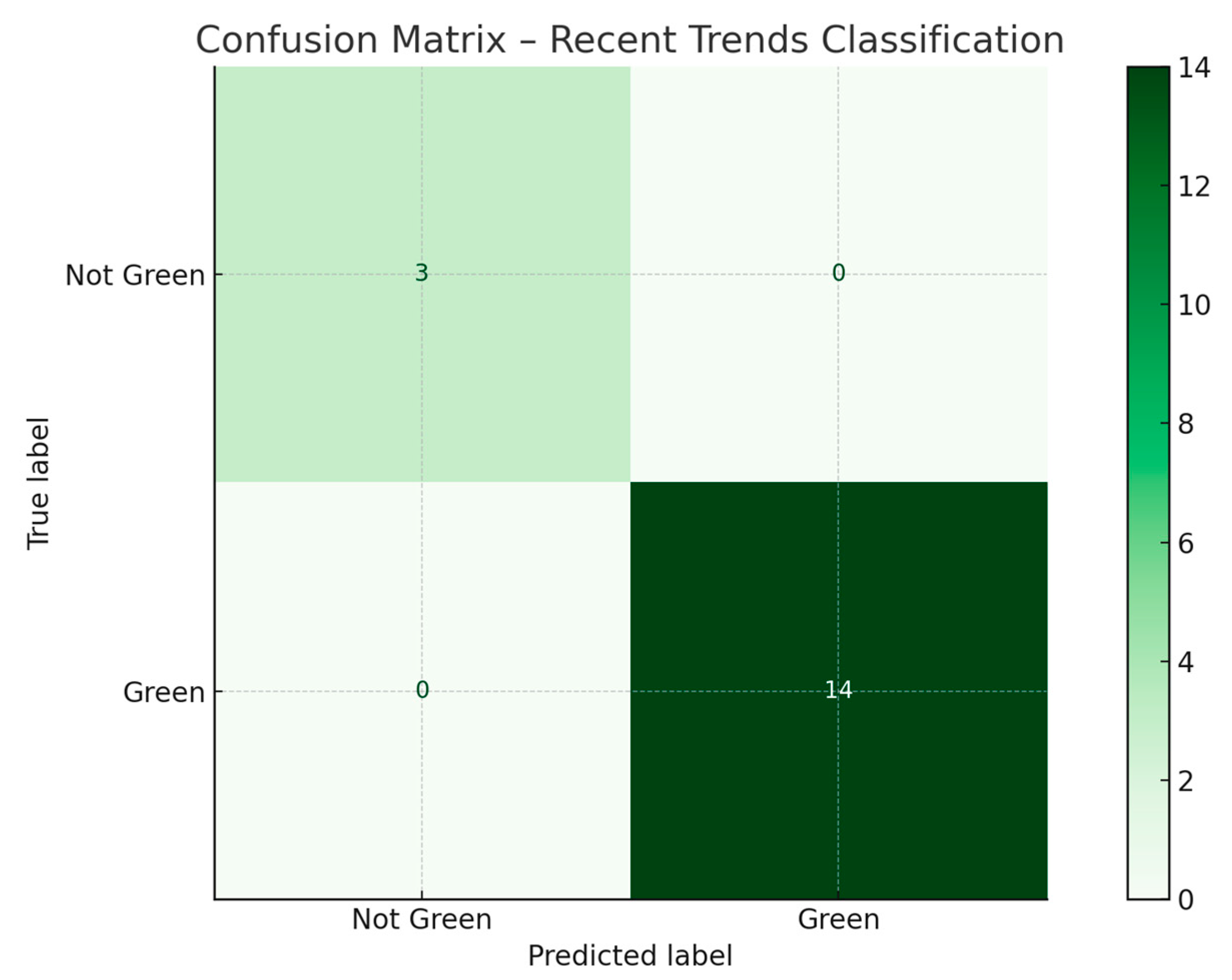

4.2. Classification Based on Recent Fuel Trends

To capture more immediate signals of policy impact, a second classification model was trained using only the most recent five years of fossil fuel consumption data. This short-term model significantly outperformed the historical one, achieving an overall accuracy of 88.9%, with a near-perfect F1-score of 0.93 for the “greening” class and 0.67 for the “not greening” class.

This suggests that recent behavioural shifts, likely influenced by post-2020 policy actions, pandemic-related energy dynamics, and REPowerEU directives, are more predictive of transition status than long-term historical inertia. Notably, this model was better able to detect countries not undergoing transition, indicating improved class balance in short-term trends.

Table 2.

Metrics for Recent Model.

Table 2.

Metrics for Recent Model.

| Metric |

Class 0 (Not Greening) |

Class 1 (Greening) |

| Precision |

1.00 |

0.88 |

| Recall |

0.50 |

1.00 |

| F1-score |

0.67 |

0.93 |

| Accuracy |

88.9% (8/9 countries) |

— |

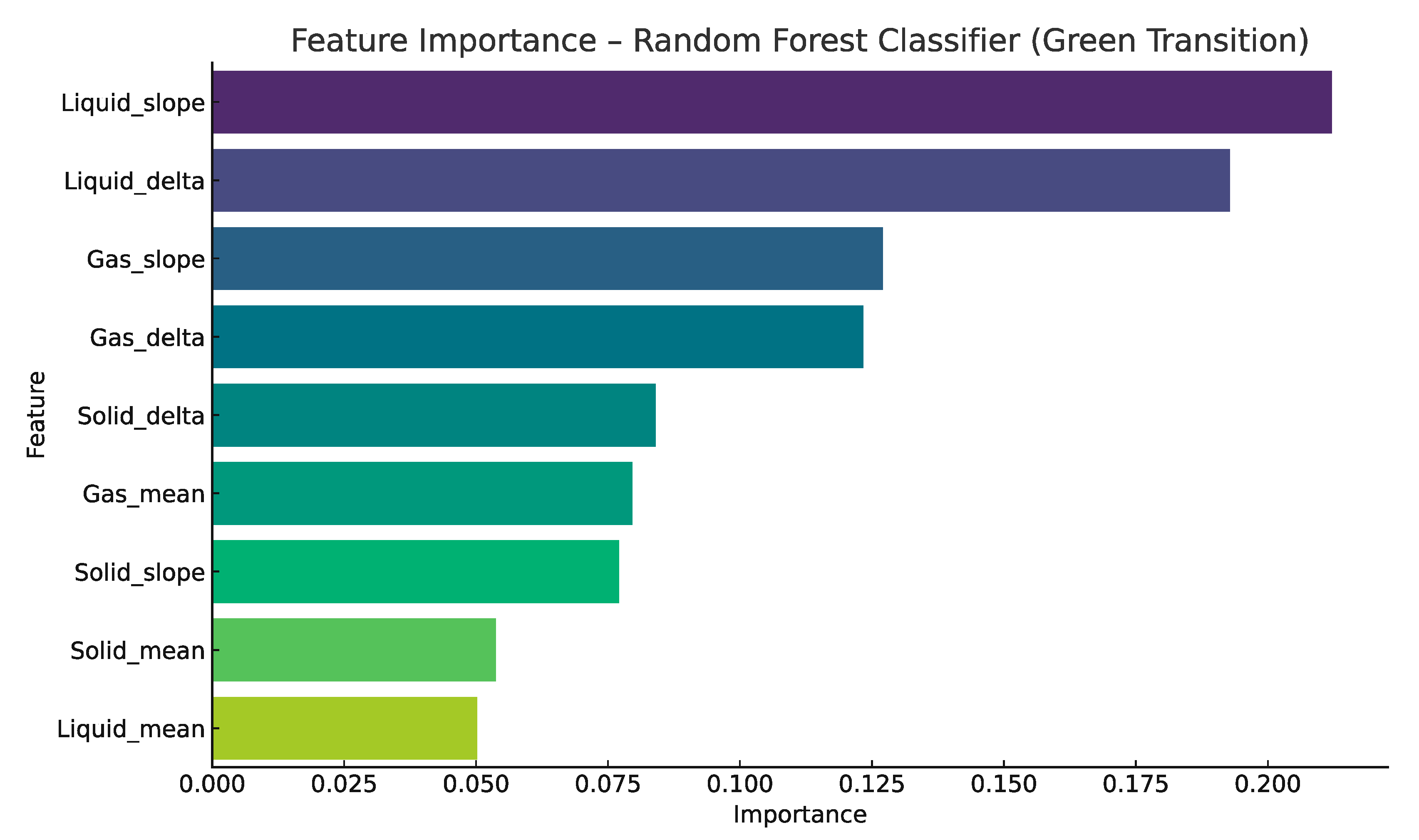

4.3. Feature Importance and Model Interpretability

To understand what drives the classification of countries as either “greening” or “not greening,” feature importance was analysed using both Gini-based impurity and permutation importance methods. In both historical and recent models, the most influential features were related to liquid fuel consumption specifically:

Liquid_slope – the rate of change in liquid fuel use,

Liquid_delta – the net absolute change over the period (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Confusion Matrix of Model Predictions (Historical Window). Confusion matrix showing classification results for green transition based on full historical fuel consumption trends. The imbalance between classes is evident, with the model performing well on ‘greening’ cases but failing to identify non-transitioning countries correctly.

Figure 1.

Confusion Matrix of Model Predictions (Historical Window). Confusion matrix showing classification results for green transition based on full historical fuel consumption trends. The imbalance between classes is evident, with the model performing well on ‘greening’ cases but failing to identify non-transitioning countries correctly.

Figure 2.

Confusion Matrix – Recent Trends Classification. Confusion matrix for the model trained on the recent five-year trends in fossil fuel. The model demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity, accurately identifying both transitioning and non-transitioning countries, surpassing the accuracy of the historical model.

Figure 2.

Confusion Matrix – Recent Trends Classification. Confusion matrix for the model trained on the recent five-year trends in fossil fuel. The model demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity, accurately identifying both transitioning and non-transitioning countries, surpassing the accuracy of the historical model.

Figure 3.

Feature Importance Plot (Recent Trends Model). Permutation-based feature importance plot for the short-term transition model. Liquid fuel indicators significantly contribute to the predictive power, underscoring the relevance of oil consumption trends as indicators of structural decarbonisation.

Figure 3.

Feature Importance Plot (Recent Trends Model). Permutation-based feature importance plot for the short-term transition model. Liquid fuel indicators significantly contribute to the predictive power, underscoring the relevance of oil consumption trends as indicators of structural decarbonisation.

These two features accounted for over 40% of total model importance in both timeframes, indicating that liquid fuels serve as the clearest empirical signal of green transition behaviour. This aligns with the political visibility and economic centrality of oil consumption in the EU’s energy mix, particularly in transport and industry.

Gas and solid fuel indicators made a marginal contribution to the historical model. Still, they gained slight importance in the recent model, particularly Gas_slope_recent, reflecting more recent volatility in gas consumption due to geopolitical and market disruptions.

Among all predictors, only changes in liquid fuel usage had a measurable impact on classification performance. This suggests that policy efforts aimed at reducing oil dependence are the most empirically detectable signals of transition, reinforcing the political importance of transport and industrial decarbonisation pathways.”

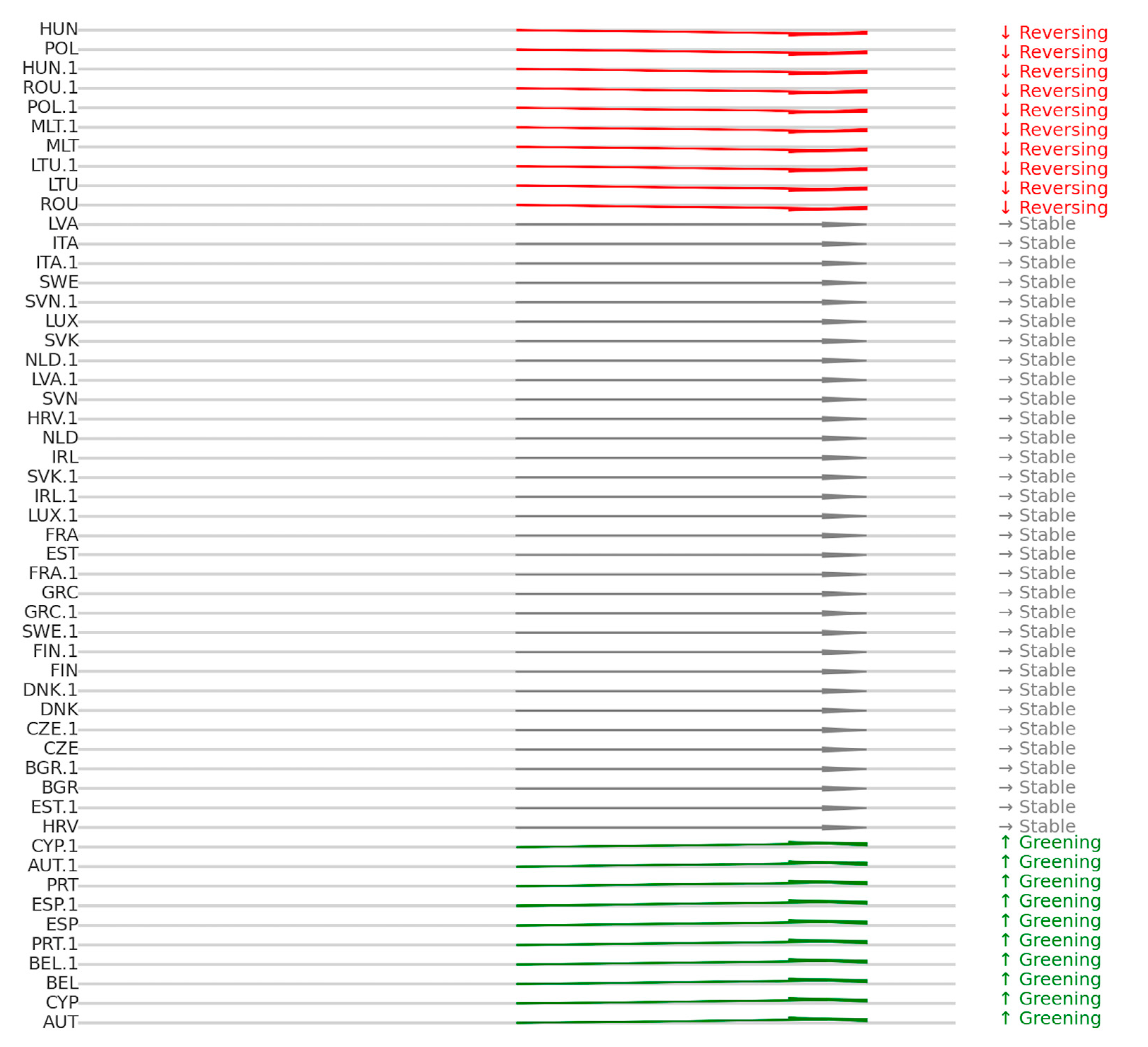

4.4. Temporal Dynamics and Label Reversals

Beyond binary classification, this study examines the temporal consistency of countries’ transition statuses by comparing predictions based on long-term historical trends with those derived from the most recent five-year window. This dual-window approach enables the identification of label reversals, where countries switch from “not greening” to “greening” or vice versa, revealing non-linear and dynamic decarbonisation paths.

Several EU Member States experienced such reversals. For example, Austria, Belgium, and Spain were classified as “not greening” based on historical data but showed substantial recent declines in fossil fuel consumption, leading to a “greening” classification in the short-term model. These upward reversals suggest that recent policy actions or post-pandemic structural shifts have begun to exert measurable influence on energy consumption patterns. In contrast, countries like Hungary and Czechia displayed the opposite pattern: despite historical downward trends, their recent fossil fuel use either stagnated or rebounded. These downward reversals may signal transition fatigue, an economic recovery-driven rebound in emissions, or delayed policy implementation.

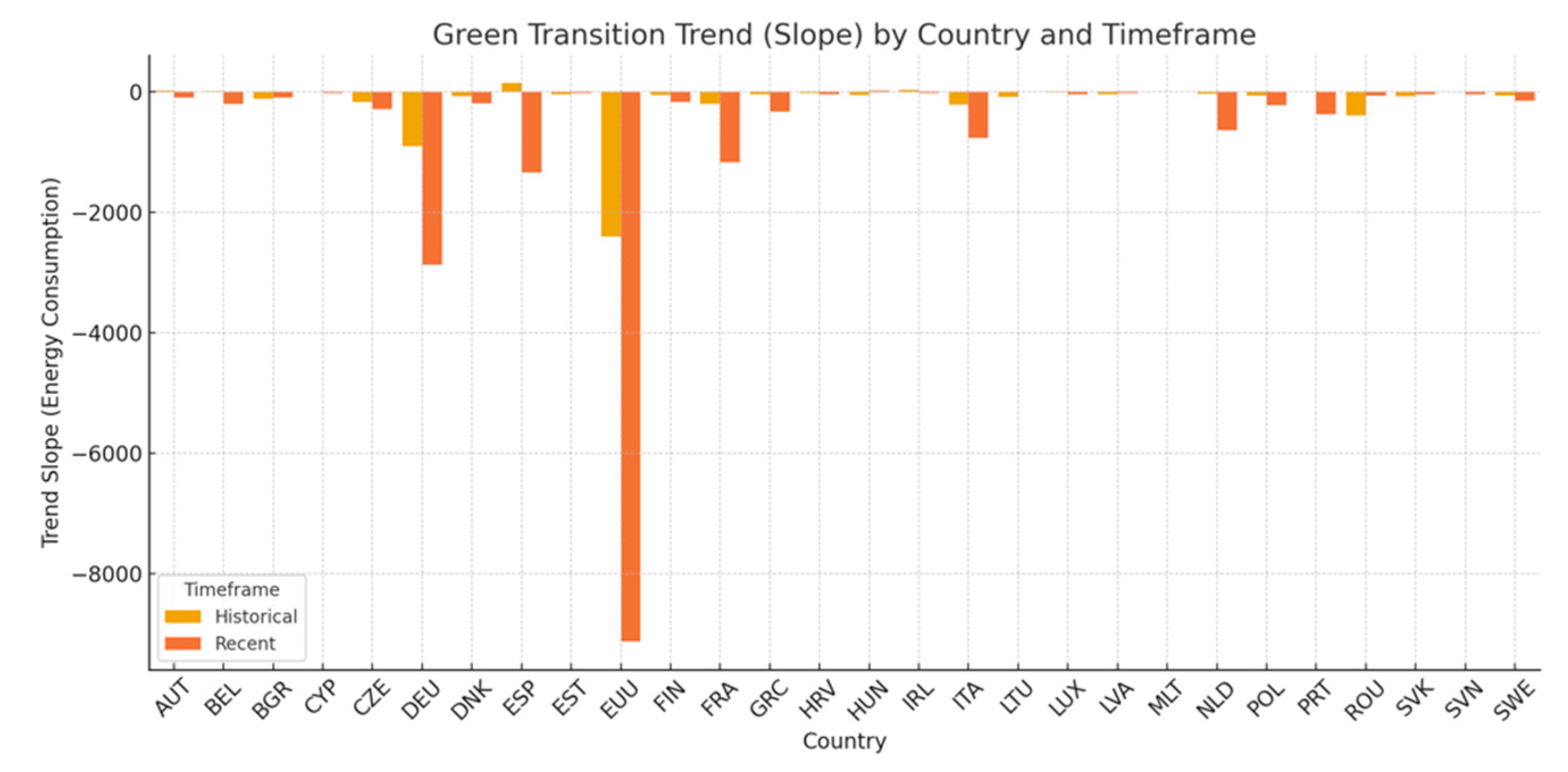

Figure 4 below presents these label dynamics:

To further quantify these behavioural shifts, we introduce the slope differential metric:

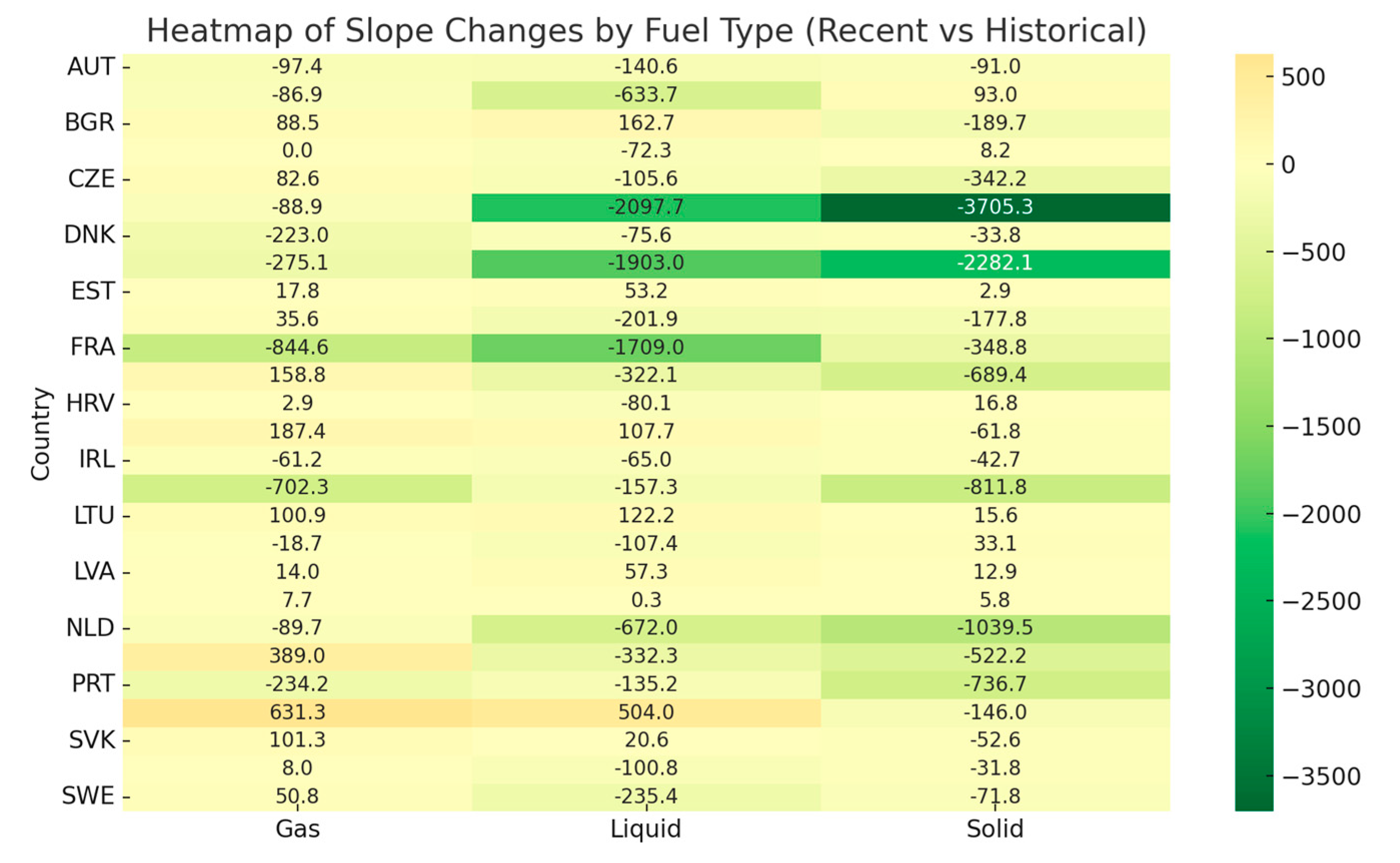

This metric measures the acceleration or deceleration of fossil fuel consumption for each country and fuel type (gas, liquid, solid). Negative values indicate a faster decline in recent years (i.e., policy acceleration), while positive values suggest slowing progress or even trend reversal. The results are visualised in

Figure 5, a heatmap of slope changes:

This temporal analysis reveals that transition trajectories are far from static. While some countries have gained momentum, others risk losing ground, underscoring the need for continuous monitoring and adaptable policy responses.

To triangulate the slope differential findings and offer a more intuitive view of country-level momentum, two additional visual diagnostics were generated.

Figure 6 presents a direct comparison of total fossil fuel trend slopes for each country across two timeframes: historical and recent. This chart underscores the direction and magnitude of aggregate change. Countries like Denmark (DNK)

, Spain (ESP), and Estonia (EST) display more negative slopes in the recent window, indicating that their transitions have not only persisted but intensified. In contrast, countries such as Slovakia (SVK) and Portugal (PRT) show flatter or less negative recent slopes, suggesting deceleration or partial reversal in fossil reduction progress.

To capture fuel-specific dynamics,

Figure 7 disaggregates the ∆Slope values by gas, liquid, and solid fuels. This offers insight into which fuel types are driving transition behaviour in each country.

Together, these visuals confirm that energy transitions in the EU are heterogeneous, fuel-dependent, and time-sensitive. These diagnostics also provide the empirical grounding for the country-level profiles that follow.

4.5. Country-Level Cases

To complement the aggregate classification and trend analyses, this section presents illustrative case studies of selected EU Member States. These country-level profiles are based on the observed differences between historical and recent fossil fuel consumption trends, with a focus on changes in slope and classification outcomes. The selected cases represent diverse trajectories: late-onset acceleration, structural deepening, and signs of reversal.

Austria represents a case of delayed but measurable progress. Historically, the country exhibited minimal reductions in fossil fuel consumption, leading to a “not greening” classification. However, over the recent five-year period, Austria has demonstrated moderate slope improvements, particularly in the use of liquid fuel. This change resulted in a classification reversal, suggesting the emergence of effective policy mechanisms post-2020, possibly in the transport or heating sectors.

Spain shows one of the most significant improvements in recent slope trends, primarily driven by reductions in liquid and solid fuels. Although its historical trajectory was moderate, recent dynamics indicate an intensified phase of transition. This may be attributed to a combination of EU-supported renewable energy expansion, national electric mobility incentives, and declining demand in the fossil-based power sector.

France presents a rare case of multidimensional acceleration, with substantial recent declines observed across all three fuel types: gas, liquid, and solid. The steepening of these slopes indicates a structural rather than cyclical decarbonisation pattern. An integrated policy mix, including carbon taxation, energy efficiency programmes, and fossil-to-renewable substitution in district heating and industry, likely supports this trend.

In contrast, Hungary exhibits signs of stagnation or reversal. Despite a historically declining trajectory, recent slopes suggest flattening or slight rebounds in fossil fuel consumption. This has led to a downgraded classification in the recent window. The underlying causes may include economic recovery effects following the COVID-19 pandemic, short-term prioritisation of energy security, or a lack of implementation capacity at the national level.

These cases collectively demonstrate the diversity and complexity of transition pathways within the EU. While some countries exhibit a strengthening of decarbonisation momentum, others reveal the fragility of early progress. The observed temporal volatility highlights the need for sustained, adaptive, and sector-specific interventions to secure long-term transition outcomes.

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine the extent to which the European Union’s climate rhetoric—enshrined in flagship initiatives such as the European Green Deal and Fit for 55—is mirrored in the empirical record of national-level fossil fuel consumption. By combining long-term and recent behavioural trend analysis with machine learning classification, the findings offer a nuanced picture: while rhetorical ambition exists at the supranational level, its translation into material transition outcomes is partial, asymmetric, and temporally inconsistent.

The results reveal that a significant share of Member States are demonstrating recent decarbonisation progress, particularly in liquid fuel consumption, which emerged as the most sensitive and policy-responsive indicator. This trend aligns with the increasing EU-level regulation in the transport sector, including vehicle electrification mandates and fuel taxation. It may signal that rhetorical commitments are beginning to influence real-world energy systems. In countries like France and Denmark, where fossil fuel decline was both deep and cross-sectoral, the evidence supports the notion that rhetorical intent and material transformation can be mutually reinforcing.

However, the inclusion of slope differential metrics and dual-window classification introduces a more complex narrative. Many countries classified as “greening” in the historical window showed stagnation or even reversal in recent years. These label reversals, observed in countries such as Hungary and Czechia, raise critical questions about the durability of transition trajectories and the depth of policy institutionalisation. Short-term improvements may reflect temporary demand shocks or cyclical effects rather than structural change. Conversely, recent gains in late-shifting countries like Austria and Spain suggest that transition is not necessarily linear but can be reactivated under the right political and economic conditions.

These findings reinforce the idea that rhetoric and reality are misaligned, not categorically, but conditionally. The EU’s strategic climate vision sets clear normative expectations, but the operationalisation of that vision varies widely across Member States. Multilevel governance, divergent national energy mixes, and the uneven absorption of EU funding and regulatory instruments all contribute to this disparity. In particular, the discrepancy between long-term and recent trends underscores the vulnerability of transition processes to policy fatigue, political turnover, or energy price volatility, especially in the wake of overlapping crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

From a methodological standpoint, this study illustrates the value of combining classification modelling with time-series diagnostics to capture transition dynamics. By introducing a dual-window approach and the slope differential metric, the analysis moves beyond static “green” versus “not green” categories to reveal momentum, acceleration, and reversibility—dimensions that are critical for policy evaluation but often overlooked in headline-level indicators.

6. Policy Implications

These findings have important implications for both EU-level governance and national policymaking:

1. The need for differentiated transition monitoring: Binary labels and aggregate targets obscure meaningful differences in transition pace and sectoral composition. EU oversight mechanisms should incorporate fuel-specific, time-sensitive indicators to detect where momentum is building or eroding.

2. Addressing policy volatility: The presence of label reversals in multiple countries signals the fragility of transition pathways. This underscores the need to institutionalise climate action across electoral cycles, reduce regulatory uncertainty, and align fiscal instruments (e.g., green subsidies, taxation) with long-term goals.

3. Reinforcing the link between rhetoric and enforcement: Political commitments must be accompanied by robust implementation architectures. Strengthening mechanisms such as the NECP review process and climate conditionalities in EU funding could help close the gap between aspiration and execution.

4. Early-warning diagnostics for policy adaptation: Tools like slope differential tracking and machine learning classification can act as early warning systems, flagging deceleration or reversal before formal compliance gaps appear. This empowers policymakers to intervene proactively rather than retroactively.

In sum, the European Union’s climate narrative is not disconnected from material outcomes, but the relationship is conditional, uneven, and sensitive to time. Ensuring that rhetoric continues to align with and reinforce empirical trends will require sustained political commitment, rigorous monitoring, and adaptive governance mechanisms capable of navigating transition volatility.

7. Conclusions

This study offers a data-driven assessment of the alignment between the European Union’s climate ambitions and the actual energy transition behaviours of its Member States. The results suggest a cautiously optimistic yet fundamentally asymmetric relationship between rhetorical commitments and material outcomes.

On the one hand, several countries—most notably Germany, Denmark, and Austria—have demonstrated clear downward trends in fossil fuel consumption, particularly in the use of liquid fuels. These trends, captured by machine learning classification, indicate that EU-level policy signals may be exerting tangible behavioural influence at the national level.

On the other hand, the analysis of slope acceleration metrics and label reversals reveals a more complex and fragmented reality. Some Member States, despite public commitments to green transition objectives, display stagnating or even reversing trajectories in specific fuel types. This indicates that transition pathways are neither linear nor uniformly progressive, but instead subject to short-term shocks, reactive policy adjustments, and inconsistent implementation.

The presence of countries shifting between “green” and “not green” classifications further reinforces the notion that energy transition is not a binary status but a dynamic process requiring ongoing empirical scrutiny. Slogans such as “Fit for 55” and the “Green Deal” establish important normative targets, but these must be continuously validated against behavioural and structural evidence.

In conclusion, while some EU Member States are indeed “walking the talk,” others remain trapped in the space between commitment and implementation. This highlights the need for ongoing, multidimensional monitoring of decarbonisation behaviours—and for caution against conflating aspirational narratives with measurable progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; methodology, O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; analysis and selection of sources and the literature, O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; consultations on material and technical issues, O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; literature review, O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; writing—original draft O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, O.P., O.L., K.P., M.R., A.K., T.V. and M.H.; supervision, O.L., K.P. and O.P.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

his work was supported by a subsidy from the Ministry of Education and Science for the WSEI (Project No. 8/121/226upf).

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are publicly available, all datasets are in the public domain and were available as of 01 May 2025. The results of the author’s calculations are the author’s own and are reliable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sala, D.; Liashenko, O.; Pyzalski, M.; Pavlov, K.; Pavlova, O.; Durczak, K.; Chornyi, R. The Energy Footprint in the EU: How CO2 Emission Reductions Drive Sustainable Development. Energies 2025, 18, 3110. [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, O., Pavlov, K., Liashenko, O., Jamróz, A., & Kopeć, S. (2025). Gas in Transition: An ARDL Analysis of Economic and Fuel Drivers in the European Union. Energies, 18(14), 3876. [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C., Moore, B., Boasson, E., Gravey, V., Jordan, A., Kivimaa, P., … & Homeyer, I. (2023). Three Decades of EU Climate Policy: Racing Toward Climate Neutrality? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Climate Change, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Knodt, M. (2023). Instruments and modes of governance in EU climate and energy policy: from the Energy Union to the European Green Deal, 202-215. [CrossRef]

- Knodt, M., Ringel, M., & Müller, R. (2020). ‘Harder’ soft governance in the European Energy Union. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(6), 787-800. [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C., Moore, B., Boasson, E., Gravey, V., Jordan, A., Kivimaa, P., … & Homeyer, I. (2023). Three Decades of EU Climate Policy: Racing Toward Climate Neutrality? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Climate Change, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Homeyer, I., Oberthür, S., & Jordan, A. (2021). EU climate and energy governance in times of crisis: towards a new agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 959-979. [CrossRef]

- Schoenefeld, J. and Jordan, A. (2020). Towards harder soft governance? Monitoring climate policy in the EU. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(6), 774-786. [CrossRef]

- Knodt, M. (2023). Instruments and modes of governance in EU climate and energy policy: from the Energy Union to the European Green Deal, 202-215. [CrossRef]

- Knodt, M., Ringel, M., & Müller, R. (2020). ‘Harder’ soft governance in the European Energy Union. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(6), 787-800. [CrossRef]

- Szulecki, K. and Claes, D. (2019). Towards Decarbonization: Understanding EU Energy Governance. Politics and Governance, 7(1), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, M. and Wettestad, J. (2024). Implementing EU energy and climate governance: Germany and Sweden as frontrunners? NPJ Climate Action, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Ringel, M. (2018). Tele-coupling energy efficiency policies in Europe: showcasing the German governance arrangements. Sustainability, 10(6), 1754. [CrossRef]

- Maltby, T. (2013). European Union energy policy integration: A case of European Commission policy entrepreneurship and increasing supranationalism. Energy Policy, 55, 435-444. [CrossRef]

- Gheuens, J. (2023). Putting on the brakes: the shortsightedness of eu car decarbonization policies. NPJ Climate Action, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Gheuens, J. and Oberthür, S. (2021). EU climate and energy policy: how myopic is it?. Politics and Governance, 9(3), 337-347. [CrossRef]

- Aalto, P., & Temel, D. (2013). European energy security: Natural gas and the integration process. JCMS Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(4), 758-774. [CrossRef]

- Christou, O. (2021). Energy Security in Turbulent Times Towards the European Green Deal. Politics and Governance, 9(3), 360-369. [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T., Rosenow, J., & Bertoldi, P. (2018). Energy Efficiency Obligation Schemes: Their Future in the EU. Energy Efficiency, 12(1), 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G. and Silva, P. (2017). Energy efficiency governance in the EU-28: analysis of institutional, human, financial, and political dimensions. Energy Efficiency, 10(5), 1279-1297. [CrossRef]

- Galán-Martín, Á., Vázquez, D., Cobo, S., Dowell, N., Caballero, J., & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. (2021). Delaying carbon dioxide removal in the European Union puts climate targets at risk. Nature Communications, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Oberthür, S. (2019). Hard or soft governance? The EU’s climate and energy policy framework for 2030. Politics and Governance, 7(1), 17-27. [CrossRef]

- Oberthür, S. and Dupont, C. (2021). The European Union’s International Climate Leadership: Towards a Grand Climate Strategy? Journal of European Public Policy, 28(7), 1095-1114. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M. (2014). Governing towards renewable energy in the EU: competences, instruments, and procedures. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 21(1), 39-63. [CrossRef]

- Gheuens, J. and Oberthür, S. (2021). EU climate and energy policy: how myopic is it?. Politics and Governance, 9(3), 337-347. [CrossRef]

- Williges, K., Gaast, W., Bruyn-Szendrei, K., Tuerk, A., & Bachner, G. (2022). The potential for successful climate policy in national energy and climate plans: highlighting key gaps and ways forward. Sustainable Earth Reviews, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Zaklan, A., Wachsmuth, J., & Duscha, V. (2021). The EU ETS to 2030 and beyond: Adjusting the cap in light of the 1.5 °C target and current energy policies. Climate Policy, 21(6), 778-791. [CrossRef]

- Pancheva, K., Antonova, A., Stefanov, K., Georgiev, A., Mihnev, P., & Malcheva, T. (2018). Supporting european energy consumers through gamification and competence-based learning. Serdica Journal of Computing, 11(3-4), 225-248. [CrossRef]

- Gałecka, A. and Pyra, M. (2024). Changes in the global energy consumption structure and the energy transition process. Energies, 17(22), 5644. [CrossRef]

- Phan, T. (2022). Portfolio management strategies of oil companies in the energy transition trend. Petrovietnam Journal, 2, 26-31. [CrossRef]

- Lukashevych, Y., Evdokimov, V., Maksymova, I., & Tsvilii, D. (2024). Innovation in the energy sector: the transition to renewable sources as a strategic step towards sustainable development. African Journal of Applied Research, 10(1), 43-56. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Wen, J., & Chang, C. (2023). Going green with artificial intelligence: the path of technological change towards the renewable energy transition. Oeconomia Copernicana, 14(4), 1059-1095. [CrossRef]

- Jacome, V., Pellow, D., & Deshmukh, R. (2023). Evaluating equity and justice in low-carbon energy transitions. Environmental Research Letters, 18(12), 123003. [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, J., Kern, F., & Rogge, K. (2017). The need for comprehensive and well-targeted instrument mixes to stimulate energy transitions: the case of energy efficiency policy. Energy Research & Social Science, 33, 95-104. [CrossRef]

- Sareen, S. (2023). Cross-sectoral metrics as accountability tools for twin transitioning energy systems. Environmental Policy and Governance, 33(6), 593-603. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).