Introduction

Women’s health can be recognised as a foundation of public health, with significant implications for population health, economic growth, and social development [

1]. Policies for women’s health are important to addressing and shaping the inequities that challenges affect women throughout their lives [

2]. Adolescence and young adulthood represent important stages during which access to healthcare information, nutrition, services, and products shapes lifelong health outcomes. Investments in the health of adolescent girls and young women yield notable returns by reducing maternal morbidity and mortality, improving mental health, and making healthier future generations [

3].

Adolescents (10–19 years) and young women (20–24 years) require appropriate policy for their unique health challenges, including comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services, menstrual health management, prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), safe pregnancy and childbirth, nutrition, and mental health support [

4,

5,

6]. Factors such as armed conflict, cultural taboos, financial constraints, normalized violence, and stigma significantly affect the health status of young women, particularly in low-income countries. These influences manifest in issues such as gender-based violence, early marriage, and limited access to education, underscoring the importance of developing unique policies for this population [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Global health documents and policies, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

11] and recommendations from organizations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) [

3] and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) [

12], have emphasised the importance of prioritising adolescent and young women’s health. However, progress remains inadequate, as many countries lack appropriate policies addressing the specific needs of this population, and these needs are often not prioritised [

5,

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, insufficient financial resources and infrastructure in many low- and lower-middle-income countries hinder the implementation of global health policies [

16]. Challenges such as early marriage and its associated medical and psychological complications [

17], limited access to reproductive health services and products [

18], and inadequate health education [

19] remain significant in numerous regions, yet governments and authorities have not enacted urgent or comprehensive policies to address them.

The KATHERINE Project has been developed to systematically explore current policies on adolescents’ and young women’s health, aiming to address existing gaps and challenges. By evaluating and analysing these policies, the project seeks to provide a comprehensive assessment of their content, implementation, and alignment with global equity-focused standards, while identifying strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement. The ultimate goal is to generate evidence-based recommendations that strengthen policy environments and better support the health and rights of adolescent girls and young women worldwide.

Methods

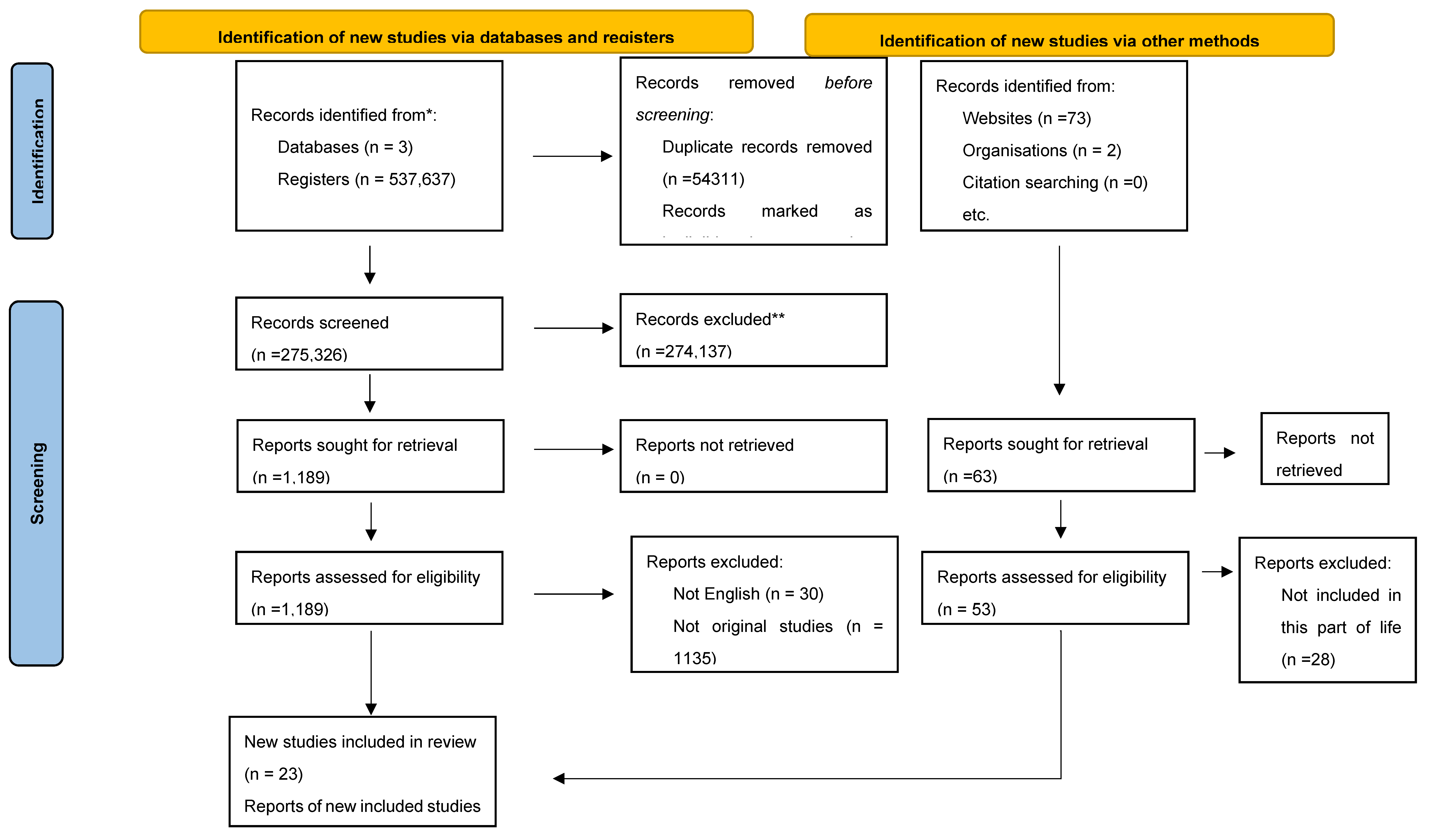

This review was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [

20,

21]. The methodological approach was established in advance to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Although the review was not formally registered, the structure adhered closely to PRISMA requirements, and each stage of the process was prospectively defined.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted on PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar through March 30, 2025. The search utilised keywords such as “women’s health”, “maternal health”, “reproductive health, and policy”, and “adolescent” AND “women”. Additionally, we searched through national and international websites, including WHO, UNFPA, and the Ministry of Health of various countries.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Three independent reviewers screened the collected articles to identify studies that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Population: women; (2) Intervention: health policy interventions; (3) Comparison: absence of such interventions; (4) Outcome: health policy–related outcomes; (5) Setting/Time: all settings and time periods; and (6) Study design: observational, interventional, or qualitative studies. Discrepancies among reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus. The selection process was documented in detail and summarized in a PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 2) [

22]. Studies or policies without an available English version were excluded.

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the AACODS checklist (Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance) [

23], a critical appraisal tool designed specifically for grey literature sources. The overall quality ranged from low to high. Studies scoring ≥25 were considered high quality, those scoring ≥19 but <25 were classified as moderate quality, and those scoring <19 were rated as low quality. Full details of the quality assessment are provided in the Supplementary Data.

Data Analysis

We conducted the analysis in two stages, combining contextual synthesis with thematic synthesis. In the first stage, all included documents (n = 48) were systematically reviewed to record key characteristics, including the type of policy (national strategy, financing reform, clinical guideline, or rights-based framework), geographical scope, publication year, and stated objectives. This process allowed us to situate each document within its policy and historical context.

In the second stage, we conducted a manual thematic analysis of the full texts of the policies. Initial codes were developed inductively from repeated reading of the documents, focusing on recurrent issues related to financing and health system capacity, service delivery models and workforce, equity and structural determinants, and adolescent and young women’s health. Coding was undertaken manually using matrices to organize and compare findings across settings. Through an iterative process, codes were refined and grouped into higher-order themes, with regular team discussions to ensure consistency, transparency, and conceptual coherence.

Finally, we synthesized the themes into a narrative account that highlighted convergences and divergences across contexts and time periods. This step integrated the thematic findings with the contextual mapping, allowing us to critically evaluate how global frameworks influenced national agendas, how equity and rights were operationalized, and where adolescents and young women were explicitly prioritized or overlooked.

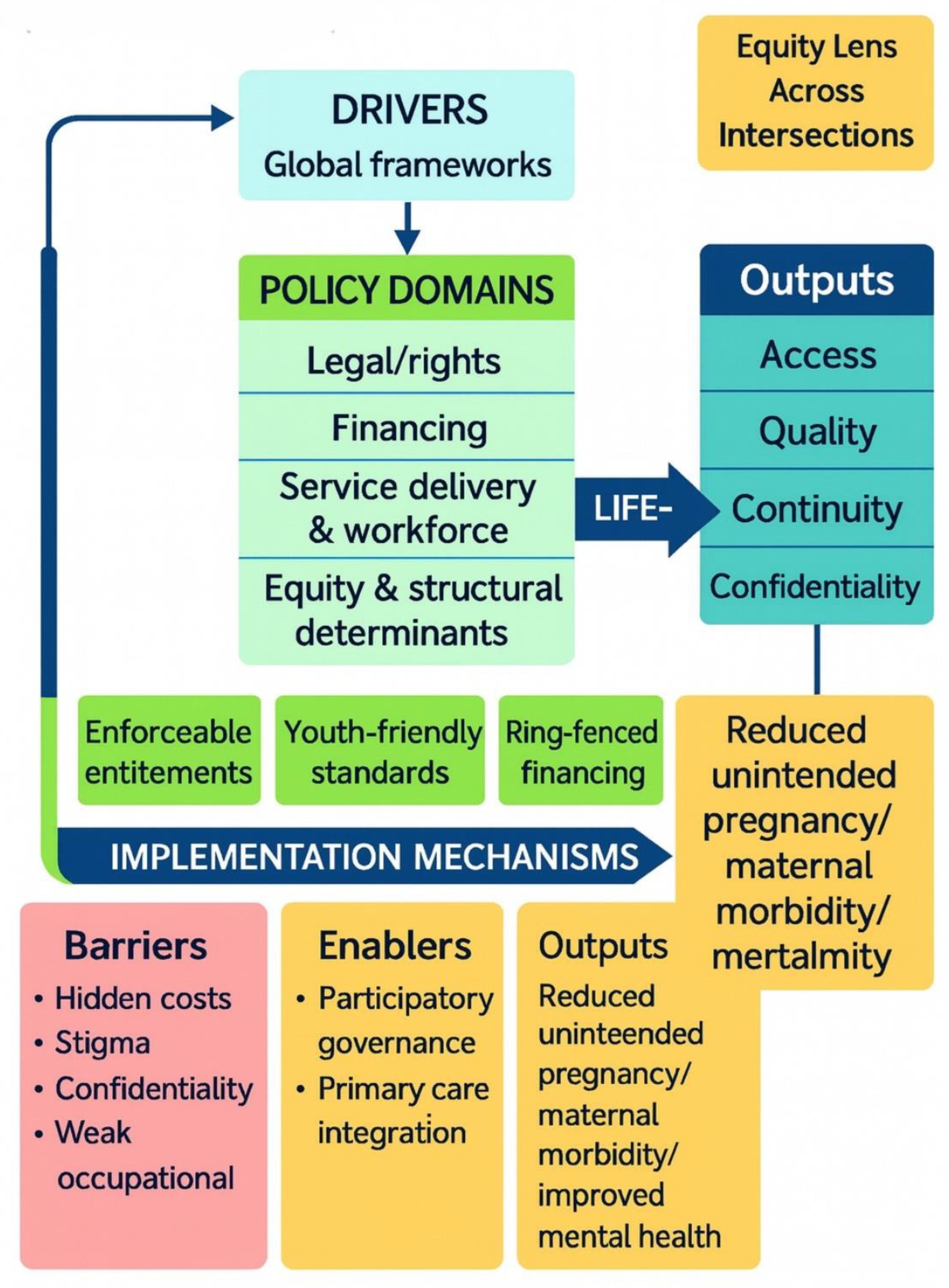

Figure 1 maps the pathways through which global agreements influence national women’s health policies. These policies are shaped by legal frameworks, financing mechanisms, service delivery models, and equity frameworks, which determine how health systems respond in practice. At the center are adolescents and young women, whose health outcomes depend on whether these policies translate into enforceable rights, adequate resources, youth-friendly services, and meaningful participation.

Results

Overview of Included Policies

A total of 48 national and international policies, strategies, and guidelines published between the early 1990s and the 2020s were reviewed. These documents encompassed national health strategies from countries such as (

Supplementary Table S1) Australia, Sri Lanka, Ghana, and Tanzania; reproductive health and financing reforms, including Ghana’s free delivery exemption, Nigeria’s Saving One Million Lives initiative, and Argentina’s harm-reduction abortion model; as well as clinical practice guidelines, such as the U.S. ACEP emergency care policy on early pregnancy. Rights- and equity-focused frameworks were also represented, for example, the comparative study on gender violence between Spain and Brazil, the World Health Organization’s guidance for refugee and migrant women, and Baltimore’s trauma-informed maternal health initiative. The dataset also included the Rwanda RMNCAH Strategic Plan (2018–2024), the Sierra Leone RMNCAH Policy (2017–2021), the Fiji Reproductive Health Policy, the Mongolia Reproductive Health Policy summary, and the Bhutan Reproductive Health Strategy, together demonstrating wide regional diversity. Collectively, these policies demonstrated a wide geographical spread across high-, middle-, and low-income contexts. Despite their diversity, they consistently highlighted the influence of global frameworks such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1979) [

24], the International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action (1994) [

25], the Beijing Platform for Action (1995) [

26], and the Sustainable Development Goals (2015) [

11]. These international agreements played a decisive role in shaping national agendas, with low- and middle-income countries frequently responding to donor-driven priorities, while high-income countries tended to embed equity, intersectionality, and rights-based approaches more explicitly.

Adolescents and young women, who were the central focus of this review, emerged as a group for whom there was a notable imbalance in policy attention. While nearly all policies acknowledged the importance of reproductive and maternal health, relatively few contained measures that explicitly addressed adolescents. When they were included, for instance, in Sri Lanka’s policies of 1998 and 2012 [

27,

28], Ghana’s 2014 reforms [

29], Australia’s strategy for 2020–2030 [

30], and the WHO’s guidance on migrant health [

31], the framing of adolescents gradually shifted from viewing them primarily as vulnerable populations to recognizing them as rights-bearing agents. Nevertheless, significant implementation gaps persisted, and in many cases, adolescents remained only implicitly referenced within broader maternal health frameworks.

Table 1.

Combined Thematic and Contextual Analysis.

Table 1.

Combined Thematic and Contextual Analysis.

| Theme |

Contextual Evidence |

Findings / Patterns |

Implications for Adolescents & Young Women |

| Legal & Policy Frameworks |

Spain’s Organic Law (2004) vs. Brazil’s Maria da Penha (2006); Tanzania’s donor-driven 1992 Population Policy; Australia’s 2020–2030 SDG-aligned strategy. |

Shift from maternal/child focus to rights-based life-course policies; donor-driven adoption in LMICs often narrowed to fertility control. |

Adolescents are acknowledged in some policies (Sri Lanka 1998, Ghana 2014, Australia 2020) but rarely operationalised into enforceable protections. |

| Financing & Coverage |

Ghana’s free delivery exemptions showed both equity gains and collapse under debt; Nigeria’s Saving One Million Lives tied funding to performance; Buenos Aires decentralised safe abortion, cutting maternal mortality. |

Fee removal and RBF increased utilisation, but donor dependence and hidden costs undermined sustainability. |

Adolescents remain highly sensitive to transport costs, informal fees, and mistrust of facilities—often deterring them from early or preventive care. |

| Service Delivery & Workforce |

Buenos Aires abortion decentralisation; Sri Lanka MCH life-course expansion; ACEP (U.S.) early pregnancy guideline modernisation. |

Nurses/midwives central; decentralised services widened reach; continuity and adolescent confidentiality were weak. |

Adolescents often faced stigma, lack of privacy, and inadequate youth-friendly training among providers, deterring service use. |

| Equity & Structural Determinants |

WHO 2018 migrant guidance (refugee girls); Baltimore trauma-informed care (post–Freddie Gray); Australia equity focus (Indigenous, rural, LBTI). |

Increasing recognition of violence, trauma, migration, and identity-based inequities, though stronger in HICs than LMICs. |

Marginalised adolescents face compounded vulnerabilities (violence, poverty, migration). Few policies operationalised equity into targeted, youth-focused programmes. |

| Adolescent & Youth Health |

Sri Lanka (1998, 2012), Ghana (2014), Australia (2020), and the WHO migrant guidance. |

Youth-specific services are still rare, often framed as behavioural prevention. |

Confidentiality gaps, provider stigma, and lack of youth participation undermine rights-based delivery; adolescents remain the least prioritised despite demographic significance. |

Combined Contextual and Thematic Analysis

Policy Drivers and Global Influences

Global agreements played a pivotal role in shaping national women’s health agendas, with their influence visible across diverse economic and political contexts. High-income countries, such as Australia, have more readily integrated the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and World Health Organization (WHO) frameworks into comprehensive national strategies that explicitly acknowledge equity, intersectionality, and rights-based approaches. By contrast, low- and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, were often constrained by donor-driven priorities and structural adjustment requirements. For example, Tanzania’s 1992 National Population Policy [

32] was closely tied to International Monetary Fund and World Bank adjustment programs, which promoted fertility reduction as part of broader economic reform. Similarly, Ghana’s early free delivery exemptions in maternal health [

33] reflected progressive intent but were introduced under conditions of financial pressure and lacked sustainable domestic ownership, leaving them vulnerable to policy failure.

While global frameworks such as CEDAW (1979), the International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action (1994), the Beijing Platform for Action (1995), and the SDGs (2015) successfully prompted widespread policy adoption, their translation into practice revealed striking disparities. The extent to which adolescents and young women benefited from these frameworks was strongly conditioned by political will, resource allocation, and institutional capacity at the national level. In donor-dependent systems such as Nepal and Ghana [

29,

34], adolescents were rarely prioritized explicitly, often subsumed within broader maternal health agendas, and left without targeted interventions. In rights-oriented systems such as Sweden’s SRHR International Policy (2006) [

35], adolescents were more visible as agents with entitlements, yet even in these contexts, their protection and participation were inconsistently implemented. This underscores the tension between international commitments and domestic realities: while global agreements provided important normative leverage, the realization of adolescent-responsive policies depended heavily on local ownership, sustainable financing, and the prioritization of equity in health governance.

Financing and Health System Capacity

Efforts to remove financial barriers to women’s health care have been central to policy reform, yet their outcomes reveal both opportunities and structural fragilities. In Ghana, maternal delivery exemptions [

33] and subsequent reproductive health service standards demonstrated that abolishing user fees increased service utilization, particularly among poorer households, and offered measurable equity gains. Similarly, Nigeria’s Saving One Million Lives initiative [

36] introduced an innovative results-based financing model, linking state-level disbursements to performance indicators such as skilled birth attendance, antenatal coverage, immunisation rates, and contraceptive uptake. In Latin America, Argentina’s adaptation of the Uruguayan harm-reduction model for abortion care [

37] illustrated how decentralization and public funding of safe abortion services dramatically reduced abortion-related maternal mortality, achieving a two-thirds decline within four years. The Rwanda RMNCAH Strategic Plan (2018–2024) [

38] built on progress in maternal and child health and explicitly positioned adolescent reproductive health within an agenda of equity, human rights, and universal health coverage.

Despite these advances, systemic constraints across low- and middle-income countries undermined the sustainability of financing reforms. In Ghana, unpredictable reimbursements and weak accountability mechanisms forced some facilities to reintroduce informal charges, eroding women’s trust in the policy and weakening its pro-poor orientation. In Nigeria, performance-based funding incentivized short-term gains but exposed deep inequities, as states with weaker administrative and health system capacity struggled to meet benchmarks, thereby exacerbating the country’s already acute geographic and socioeconomic disparities. Argentina’s decentralised model showed stronger institutionalisation, but its scalability remained dependent on political continuity and fiscal commitment.

For adolescents and young women, the limitations of financing reforms were particularly severe. Although the removal of user fees and the expansion of service packages increased theoretical access, hidden costs such as transportation, medicines, and informal payments remained prohibitive. These barriers disproportionately deterred younger women from seeking timely and preventive care, compounding risks of unsafe abortion, delayed antenatal attendance, and poor maternal outcomes. Financing reforms, therefore, highlight a recurring paradox: while they have the potential to reduce inequities and expand access, without stable domestic funding, robust institutional accountability, and adolescent-sensitive service design, they risk perpetuating the very exclusions they aim to address.

Service Delivery Models and Health Workforce

Across the policies reviewed, there was a clear trajectory from narrowly defined maternal–child health services toward more integrated and comprehensive reproductive health models. This evolution reflected the influence of global frameworks as well as domestic reforms that sought to broaden both the scope of care and the range of providers involved. In Argentina, for example, the adaptation of the Uruguayan harm-reduction model [

37] demonstrated the potential of decentralization, with general practitioners and midwives in primary care facilities trained and authorized to deliver safe abortion and post-abortion services. This shift not only expanded access geographically but also embedded reproductive health care within community-level services, thereby reducing delays, stigma, and mortality. Sri Lanka’s maternal and child health policy [

28] also exemplified integration, extending beyond maternal survival to include adolescent health, gender-based violence, nutrition, and non-communicable diseases within a life-course framework. In high-income contexts, clinical modernization was equally significant. The U.S. ACEP clinical policy for emergency departments [

39] abandoned outdated reliance on discriminatory β-HCG thresholds in the evaluation of early pregnancy complications, instead recommending universal ultrasound for symptomatic women. This represented a major advance in patient safety, particularly for young women at risk of ectopic pregnancy, who historically faced delays in diagnosis and treatment. The Fiji Reproductive Health Policy [

40] provided a life-course framework for reproductive health, emphasising primary care as the entry point and explicitly aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals. Similarly, the Mongolia Reproductive Health Policy [

41] summary highlighted urban–rural inequities in access to sexual and reproductive health services.

Central to the effectiveness of these models was the health workforce, with nurses and midwives consistently identified as frontline actors in screening, counselling, and referral. In both Spain and Brazil [

42], for instance, nurses played a pivotal role in responding to gender-based violence by identifying at-risk women and linking them with appropriate health and legal support. Similarly, in Ghana and Sri Lanka [

28,

29], midwives were crucial to implementing reproductive health strategies at community and facility levels. However, across diverse contexts, insufficient training, limited resources, and persistent provider stigma undermined the reach and quality of adolescent-friendly services. Young women often reported judgmental attitudes or breaches of confidentiality from providers, which created significant deterrents to accessing contraception, safe abortion, or care for gender-based violence.

Equity Considerations

Equity was a recurring theme across most policies, though the depth and scope of attention varied significantly by context. In high-income settings, such as Australia’s National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 [

30], the WHO’s technical guidance on refugee and migrant health [

31], and Baltimore’s trauma-informed maternal health initiative [

43], equity was framed through an explicit intersectional lens. These policies recognized the compounded disadvantages faced by Indigenous women, women in rural and remote areas, migrants and refugees, LBTI populations, and women living with disabilities, embedding these considerations as central to service planning. The Sierra Leone RMNCAH Policy (2017–2021) [

44] directly responded to alarming maternal, child, and adolescent health indicators, making RMNCAH urgent national priorities. In middle- and low-income countries, by contrast, equity frameworks were more often anchored in poverty reduction, rural disadvantage, and alignment with donor priorities, reflecting the structural constraints of financing and governance.

Legal and rights-based approaches also revealed equity as a core determinant of health. Spain’s Organic Law 1/2004 and Brazil’s Maria da Penha Law (2006) [

42] framed gender-based violence as both a public health crisis and a human rights violation, while Baltimore’s trauma-informed care initiative [

43] situated maternal health within broader struggles against racial injustice, community violence, and structural trauma. These examples illustrate how health policy can move beyond biomedical framings to address the social conditions shaping women’s health across the life course.

Yet, despite progressive rhetoric, few policies have fully operationalized integration across sectors such as housing, education, employment, and social protection. As a result, equity considerations often remained aspirational rather than transformative. This gap was particularly evident for adolescents and young women from marginalized groups, including migrant girls, Indigenous youth, and those living in rural or remote areas. While their compounded risks were frequently acknowledged, policies rarely translated recognition into comprehensive action, leaving these groups disproportionately exposed to early pregnancy, unsafe abortion, gender-based violence, and poor access to services.

Adolescent and Young Women’s Health

Adolescents and young women were explicitly prioritized in only a limited number of policies, though where this occurred, it marked an important evolution in the framing of reproductive health. In Sri Lanka, the Population and Reproductive Health Policy (1998) and the Maternal and Child Health Policy (2012) [

27,

28] recognized adolescent sexual and reproductive health as a distinct concern, calling for youth-friendly services and life-skills education. Ghana’s Reproductive Health Service Policy and Standards (2014) [

29] went further by establishing adolescent-friendly service corners and explicit standards for confidential and non-judgmental care. In high-income contexts, Australia’s National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 [

30] identified adolescence as a critical investment period, emphasizing mental health, sexual and reproductive health, and violence prevention as priorities with long-term implications for equity and wellbeing. Similarly, the WHO’s Technical Guidance on the Health of Refugee and Migrant Women [

31] highlighted the disproportionate vulnerabilities of young migrant women, underscoring the intersection of age, gender, and migration status in shaping health risks.

The Bhutan Reproductive Health Strategy [

45] explicitly recognised adolescent SRHR within a national development framework but noted resource and capacity constraints for full implementation. South Africa’s entries, including ‘Ten years of democracy in South Africa: Documenting transformation in reproductive health policy and status’ [

46] and the ‘Strategic Plan for MNCWH and Nutrition’ [

47], documented rights-based reforms and integrated maternal and adolescent commitments. The Kenya National Population Policy [

48] addressed demographic change in relation to development while referencing adolescent needs. The Nepal National Reproductive Health Policy [

34] shifted away from narrow demographic targets toward comprehensive services, including adolescent health. Bangladesh appeared in the thematic analysis of abortion access [

49], where persistent financial and social barriers disproportionately affected young, unmarried women.

Despite these advances, the majority of policies in low- and middle-income countries framed adolescents primarily through moral or behavioral lenses, emphasizing the prevention of “early” pregnancies, responsible conduct, and family stability. This paternalistic framing often obscured adolescents’ status as rights-holders and reinforced barriers to care [

18]. Confidentiality breaches, provider stigma, and restrictive social norms continued to deter young women from accessing contraception, safe abortion, and reproductive health services, undermining the stated policy goals [

50]. Even where policies adopted progressive framings—viewing adolescence as a pivotal life stage that shapes long-term health trajectories—they frequently lacked the enforceable standards, resources, and system integration needed to translate rhetoric into reality [

51].

As a result, adolescents and young women remained poorly served by fragmented and under-resourced systems. Policies that recognized their unique needs often did so at a discursive level, but implementation rarely addressed the structural determinants that constrain their autonomy and access.

Narrative Synthesis for Adolescents and Young Women

The data show that even though women’s health policy has been evolving globally from traditional frameworks that were focused on maternal survival to rights-based, equity-oriented ones, adolescents and young women continue to be a neglected majority in practice. When youth have a specific commitment, it is often inconsistent, symbolic, or rhetorical, with little or no financing, accountability, and skills building to support its application to impact [

52,

53]. The critical needs of adolescents’ access to confidential contraception and safe abortion care, prevention of violence, trauma-informed mental health care, and youth-driven service design are present, under varying degrees of frequency, in health system service delivery. Examples remain scarce, but important improvements in capacity and resilience among adolescents have occurred in places such as Ghana, where fundamentals of prevention, respect, and care are important [

29]; Sri Lanka, considering mental health, guidance, and growth-prevention [

27,

28]; Buenos Aires, where working on prevention and care [

37], and Australia where reduced barriers to equitable access [

30]. The identified trends indicate improved adolescent outcomes linked to reduced unintended pregnancies, an increase in contraceptive uptake, and a reduction in maternal deaths, improved mental health indicators, and higher satisfaction rates with services. However, these solutions were more of an adaptation journey for those involved than a concrete outcome.

Adolescents are confronted with particular hazards from chronic conditions that are becoming more important and are rarely prioritized in policies. WHO’s Global Health Observatory (GHO) indicates that the burden of morbidity and disability during the adolescent lifecycle attributable to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), especially mental health disorders, cancers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases, constitutes a significant and increasing proportion of morbidity and disability during the adolescent phase with the potential for multi-generational consequences [

54]. An epidemiological fact sheet of the WHO identified that adolescents face several important health risks, injuries, violence between inter-personal partners, self-harm, pregnancy and childbirth, mental health disorders, and adolescent fertility rates estimated at 42 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19 years in 2021 [

55]. The combined impression of these chronic and acute health risks demands an urgent focus on the development of adolescent-centred policies that address immediate and potentially long-term health development trajectories.

Moreover, adolescents with chronic conditions face complicated realities: they have a strong clustering of health-risk behaviours, few protective factors, and concurrency of social vulnerabilities, including stigma, low school engagement, and family stress, all of which can undermine their health trajectory [

56]. These intersections reinforce the need for policy frameworks that are both multisectoral and developmentally responsive.

Despite this strong evidence base, the reviewed policies show significant gaps. Although many countries have adopted adolescent-inclusive policies, they often remain siloed within the health sector, with limited engagement of education, social protection, or mental health systems. As the

Lancet series underscores, “a multisectoral approach is essential” to effectively address structural determinants of adolescent health [

57]. Moreover, implementation fidelity suffers as most frameworks lack comprehensive adolescent-specific indicators—scoping reviews show that even vital domains like service quality or system performance are seldom measured [

58]. Combined with the widespread absence of economic evaluations—cost-effectiveness studies are rare in LMIC adolescent health programs [

59], these findings highlight how adolescent health commitments often remain aspirational rather than operational.

This disparity underscores profound evidence gaps: the need to develop youth-sensitive monitoring systems, disaggregate data by age, sex, and context; consider chronic conditions; and include processes that allow adolescents to be active stakeholders, not just passive beneficiaries in the policy development process. Barring a significant investment in these areas, adolescents and young women remain at risk of being overlooked and left behind in global health policy development, even though they are shouldering substantial immediate and long-term health risks.

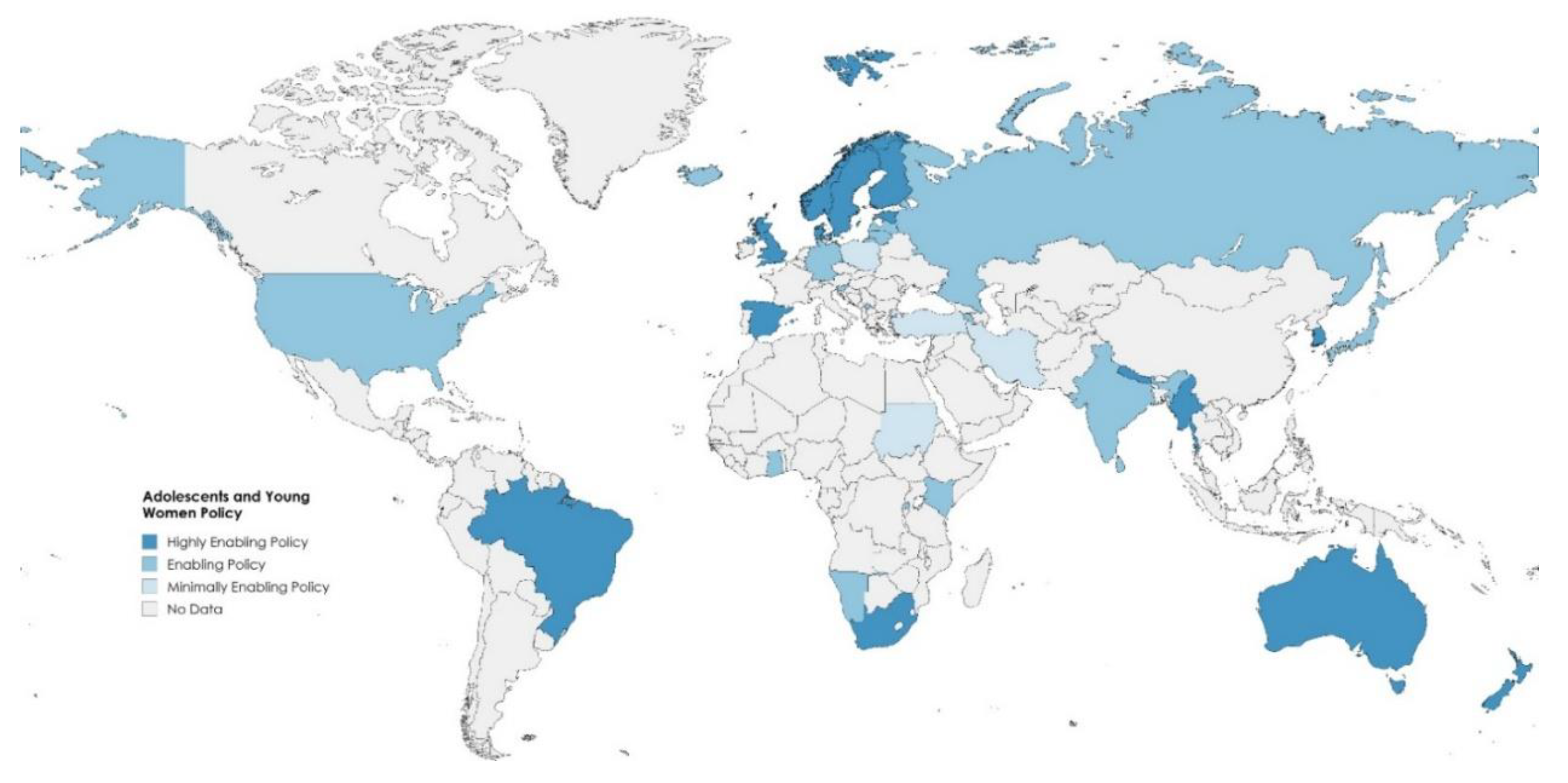

Figure 3.

Global Distribution of Adolescent and Young Women’s Policies.

Figure 3.

Global Distribution of Adolescent and Young Women’s Policies.

Discussion

This systematic review of 48 global and national women’s health policies found an evolving paradigm shift from a focus on maternal survival to a broader, rights-based, life-course approach. Legal frameworks, financing streams, and service delivery mechanisms have changed, yet the ongoing and substantial inclusion of all adolescents and all women into these policy structures remains problematic. Our synthesis demonstrated that global policies, such as CEDAW, ICPD, the Beijing Platform for Action, and SDGs, acted as catalysts for national action, but the adolescent-sensitive implementation hinged on deeply ingrained political economies, financing potentials, and health systems.

Interpretation of Principal Findings

This review indicates that global women’s health frameworks such as CEDAW (1979), the ICPD Programme of Action (1994), the Beijing Platform for Action (1995), and the SDGs (2015) contributed to the advancement of national health policies. However, the implementation of global commitments to adolescent- and youth-sensitive practice differed significantly across diverse political and economic contexts. In high-income countries (HICs), with sufficient fiscal space and comprehensive and trustworthy data collection, rights-based approaches were more visible. For example, Australia’s National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 includes equity, intersectionality, and mental health as explicit policy pillars while recognizing the role of structural determinants such as indigeneity, rurality, disability, and sexual diversity [

30].

By contrast, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), donor priorities shaped both the content and scope of policy adoption. Ghana’s

Free Delivery Exemption Policy illustrates this tension [

33]. While initially progressive, its implementation was driven by IMF/World Bank structural adjustment programs, which required fertility reduction and health sector rationalization as conditions of economic reform. Ghana’s GDP stood at ~

$82.8 billion in 2024 (GDP per capita ~

$2,400), with inflation above 23% and external debt levels near 70% of GDP [

60]. Within this fragile macroeconomic context, reimbursement delays undermined the policy’s credibility, forcing facilities to reintroduce informal fees. Adolescents were particularly affected, as “hidden costs”—transport, drugs, and stigma from providers discouraged early and consistent service use.

Nigeria presents another, but complementary case. The Saving One Million Lives initiative [

36], financed by the Global Financing Facility at the World Bank, rolled out results-based financing linked to maternal health performance indicators. This catalysed increased utilization of maternal health services in the stronger states, while at the same time, it deepened inequities for the weaker states, which were unable to meet the benchmark requirements. This failure must be viewed against Nigeria’s epidemiological context: it is responsible for around 20% of the global burden of maternal deaths, and it had a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 1,047 per 100,000 live births in 2020, among the highest in the world. Rural and conflict-affected adolescents and young women experienced a disproportionate burden of maternal mortality, reflecting the inability of financing reforms to address deep-rooted structural inequities in maternal health without accompanying substantial investment in system capacity and accountability [

61,

62].

Service delivery reforms linked to decentralization, integration, and clinical modernization make these inconsistencies even clearer. For example, with a decentralized system of abortion care in Argentina, obstetricians, general practitioners, and midwives practicing in primary care were empowered to provide safe abortion services to their clients and, as a result, effectively reduced abortion-related maternal mortality by two-thirds in four years [

37]. In Sri Lanka, instead of a fragmented system, the health system integrated adolescent health, gender-based violence, and chronic conditions under maternal-child health frameworks to allow for a whole-person, holistic view of health care [

27,

28]. In the United States, clinical modernization, in this instance, a policy by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) demonstrated evidence-informed reforms could enhance adolescent safety by moving from HCG thresholds to universal ultrasound for early pregnancy emergencies [

39]. Despite the evidence and that the majority of abortions arise from unintended pregnancies, absent widely available earlier state-based care and even in countries where evidence-based change is possible, such as India, where health governance is a state matter, and China, where provincial variations are normative no integrated care systems for adolescents have emerged, leading to continued and substantial disparities in access and outcomes [

63,

64].

Lastly, equity rhetoric has proliferated across settings and contexts, though, as a construct, it remains very weak in practice. Many policies highlight priority groups such as migrants, rural women, Indigenous populations, or LGBTI persons—but this rarely translates into enforceable actions, adolescent-specific targets, or integrated multisectoral efforts [

65]. Even when policies signal inclusivity, evaluations consistently reveal critical cracks: provider bias, breaches of confidentiality, and lack of adolescent-tailored monitoring all persist across contexts [

66]. Moreover, the most vulnerable—including adolescents in remote or conflict-affected areas—remain underserved, underscoring that equity often remains an aspiration rather than a reality [

67].

Regional Contrasts

The wider dataset highlights these regional contrasts. In sub-Saharan Africa, Rwanda and Sierra Leone [

38,

44] positioned adolescent and maternal health centrally within RMNCAH strategies, while South Africa and Kenya advanced rights-based policies that struggled with uneven implementation [

47,

48]. In South Asia, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan adopted adolescent-inclusive frameworks that were progressive in design but limited by resources [

34,

45,

49]. In the Pacific, Fiji’s policy demonstrated life-course alignment with global goals but faced delivery challenges [

40], while in East and Central Asia, Mongolia highlighted persistent geographic inequities [

41]. In Europe, Spain, Sweden, and the UK adopted equity-framed women’s health strategies [

35,

42,

68], and in the Americas, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and the U.S. reflected divergent reforms, from abortion liberalisation to trauma-informed initiatives [

37,

39,

42,

69].

Comparison with Prior Policy Trajectories

The trajectory of women’s health policy can be broadly understood through three overlapping phases: (1) the maternal survival era, (2) the reproductive health and rights movement, and (3) the life-course and equity-based approach. Each phase reflects shifting global governance priorities and national policy responses, yet the inclusion of adolescents and young women has remained inconsistent and often superficial.

In the maternal survival era (1970s–1980s), policy action stemmed more from a worldwide outcry about unacceptably high levels of maternal mortality than from any real commitment to safe motherhood. The Safe Motherhood Initiative, established in 1987, prioritized highly trained birth attendants, emergency obstetric care, and controlling fertility. Although this helped save millions of lives, adolescents were rarely recognized as a separate analysis within maternal health structures or frameworks. This absence is strange considering that adolescent mothers have far higher risks of eclampsia, puerperal infection, and severe systemic complications than women between the ages of 20 and 24 [

70].

The reproductive health and rights phase (1990s-2000s), following ICPD (1994) and the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action, reconceptualised maternal survival within a more expansive, rights-based agenda. While maternal survival continues to be an important concern, there has been a notable policy shift in various regions toward prioritizing broader aspects of sexual and reproductive health. In Latin America, commitments around contraception, safe abortion, and gender equality have become central to women’s health policies, marking a transition from traditional maternal-focused frameworks [

71]. Similarly, in Sub-Saharan Africa, contemporary analyses show that adolescent-focused SRH services—particularly access to contraception and safe abortion—are increasingly recognized as essential policy priorities, even as structural and socio-ecological barriers continue to impede their full realization [

72]. However, the reforms in many LMICs were external, donor-dependent, and tied to macroeconomic adjustment programs. For example, Ghana’s reproductive health policies in this period were shaped by IMF/World Bank mandates that used fertility reduction purely as part of the economic reform agenda as devoid of any rights-based vision [

73]. Adolescents were being framed predominantly as a risk group, rather than having confidentiality and autonomy.

The life-course and equity phase (2010s onward) reflects the influence of the SDGs and the WHO’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) agenda, which framed health as a continuum across stages of life and embedded intersectional determinants such as migration, indigeneity, and disability. Policies like Australia’s

National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030 and Argentina’s harm-reduction abortion framework exemplify this maturity [

30,

37]. Yet, while these strategies explicitly mention adolescents, the translation into actionable entitlements, youth-friendly standards, dedicated funding, and accountability mechanisms remains uneven. Adolescents continue to be poorly represented in national and global data systems, which most often aggregate them into the broad category of “women of reproductive age” (15–49 years), thereby obscuring their specific vulnerabilities and needs. This lack of age-disaggregated data has been repeatedly identified as a critical barrier to adolescent-sensitive policy evaluation [

74,

75,

76].

Importantly, trends in maternal mortality and morbidity highlight this policy gap. Globally, maternal mortality decreased by 34% between 2000 and 2020, yet the decreases were uneven: sub-Saharan Africa still has 70% of maternal deaths, and Nigeria alone accounts for nearly 20% [

77]. Countries like Sri Lanka, on the other hand, have sustained low maternal mortality with a long history of investment in midwifery, universal access, and integration of adolescent services. Nevertheless, beyond mortality, there are a significant number of morbidities mental health, chronic disease, and complications of unsafe abortion that remain less captured. Adolescents experience a particularly high unmet need for contraception, and unsafe abortion is common, with greater risks of obstetric fistula and decreased mental health in the aftermath of early pregnancy; yet, few policies have taken a systematic approach to address these morbidity pathways [

78,

79].

Altogether, the evolution of policy trajectories indicates the potential for shared understanding of women’s rights and health equity to expand. But not all women and girls have benefited equally: the interests of older women and mothers have been prioritized, while adolescents and young women are often omitted and viewed in terms of the potential harms to maternal health indicators, not as rights holders with agency and multiple needs. The fact that maternal mortality remains persistently high in LMICs, as well as the largely overlooked adolescent morbidity burden, serves as a reminder that converting global commitments to actions in national health systems is still an unfinished agenda, and one that must include all young people.

Implications for Adolescents and Young Women

Adolescents and young women experience intersecting vulnerabilities—spanning sexual, reproductive, and mental health—that extend well beyond traditional maternal health concerns. Evidence from Sri Lanka illustrates how targeted rules and service adaptations, such as the establishment of Youth-Friendly Service centers (“Yowun Piyasa”), led to better alignment with adolescent needs—enabling access to condoms, emergency contraception, and pregnancy testing—while general, adult-oriented services faced shortcomings like poor confidentiality and low youth engagement [

80,

81]. In Australia, tailored community-based mental health initiatives, especially those offering integrated multidisciplinary care, have demonstrably improved mental health outcomes and psychosocial wellbeing among youth [

82]. In contrast, policy approaches that frame adolescents primarily in moral or behavioral terms tend to miss the mark, perpetuating stigma, eroding care-seeking, and failing to address their lived realities.

Adolescents face a unique set of risk factors, including high rates of unintended pregnancy, unsafe abortion, gender-based and intimate partner violence, and high mental health burden. Chronic conditions depression, diabetes, and anaemia are common have relatively increased rates among adolescents, with lasting implications for health equity [

55,

83]. Social determinants such as poverty, rural residence, migration status, disability, and LBTI identity exacerbate these risks. Policies that addressed these factors with enforceable entitlements, dedicated financing, and youth participation achieved more durable improvements.

Below, we outline the four central features that shaped adolescent and young women’s health outcomes, with expanded explanations and recommendations for future policy design.

Table 2.

Central features of Adolescent and Young Women’s Health outcomes.

Table 2.

Central features of Adolescent and Young Women’s Health outcomes.

| Feature |

Explanation |

Recommendations |

| Clear entitlements |

Adolescents require explicit rights to free, confidential contraception, safe abortion, post-violence care, and mental health services. Without enforceable entitlements, services are inconsistently provided and easily deprioritized in budget cycles. |

Legally codify adolescent entitlements in national regulations and provider contracts; include grievance redress mechanisms at the facility level; link facility accreditation to compliance with confidentiality and rights standards. |

| Youth-friendly service standards |

Standards such as private counseling rooms, opt-out chaperone policies, adolescent-only clinic hours, and provider training for non-judgmental care directly improve care-seeking, confidentiality, and satisfaction. |

Mainstream youth-friendly protocols into primary care; create national accreditation for adolescent-friendly facilities; include stigma reduction in continuing medical education. |

| Dedicated adolescent funding |

In LMICs, adolescent programs are often diluted during budget execution, leaving young women dependent on under-resourced maternal health frameworks. Dedicated funding protects adolescent priorities from being absorbed into broader maternal programs. |

Ring-fence funds for adolescent SRH services; introduce adolescent-specific performance indicators in financing contracts (e.g., % of adolescents accessing contraception or mental health services). |

| Youth participation in governance |

Adolescents are often recipients but not co-creators of policy. Participatory mechanisms—youth councils, peer navigators, scorecards—ensure services reflect lived realities and strengthen accountability. |

Institutionalize youth representation in health policy governance; provide funding for youth-led monitoring; expand peer-support models integrated into national systems. |

Policies lacking one or more of these features showed only partial improvements: for instance, service utilisation increased, but continuity of care lagged; or stigma persisted despite expanded service menus. This highlights that rhetoric alone is insufficient; policies must be backed by legal enforceability, financial protection, system-level accountability, and youth voice.

Financing and Delivery: From Access to Assurance

Removing point-of-care fees increases use, but whether adolescents and young women actually receive timely, respectful, and continuous care depends on the macroeconomics of fiscal space and the microeconomics of provider payment

. Ghana’s experience is instructive. As a lower-middle-income economy, Ghana posted 5.7% GDP growth in 2024, yet entered 2025 with elevated inflation and ongoing debt restructuring under an IMF program conditions that compress health budgets and create cash-flow stress for facilities [

60,

84]. Fee exemptions for deliveries did raise utilization, especially among poorer women, but delayed reimbursements under the National Health Insurance Scheme repeatedly pushed facilities toward informal charges and stockouts—precisely the hidden costs that deter adolescents (transport, medicines, “tips,” privacy) [

33,

85,

86]. In such contexts, “free care” is

not assurance for youth: the policy promise is undermined by arrears, weak accountability, and the absence of adolescent-specific financing lines that protect confidentiality and continuity.

Nigeria illustrates the vulnerabilities associated with a different financing mechanism. The Saving One Million Lives program used results-based financing had purchased units of service provision according to performance indicators, like skilled attendance to birth and coverage for vaccines. While this created sharper incentives in the stronger states, weaker states had no administrative capacity to meet targets for any of the performance indicators, leading to a widening of inefficiencies and differential access to critical services among adolescents [

36]. Additionally, the poor state of Nigeria’s epidemiological profile nearly one in five global maternal deaths occurring in Nigeria, with adolescents disproportionately represented among first pregnancies in high-risk settings, means that performance-based schemes that incentivize service delivery in stronger states tend to be detrimental to fragile states that lack the essential resources to meet the performance targets. This can leave the highest-risk populations, specifically adolescents residing in rural and conflict-affected settings, without continuous access to quality health care and other ecosystem-based services [

62].

By contrast, Argentina’s decentralized harm-reduction abortion model illustrates how financing aligned with service delivery can reshape outcomes. By devolving funding and authority to primary care and empowering general practitioners and midwives to provide abortion and post-abortion care, Argentina achieved a dramatic reduction in abortion-related maternal mortality within just a few years. In this model, financing supported the spaces where adolescents actually sought care, services were normalized rather than exceptional, and provider training and legal protection created the assurance needed for adolescents to seek care without fear of stigma or denial [

37].

These encounters reveal that access policies do not equal assurance for adolescents. In LMICs like Ghana and Nigeria, there are limits to fiscal space or health system constraints, a lack of resource transfers to providers where they may wait months, and aid conditionalities that can undermine sustainability, leading to additional costs to young women or breaches in service delivery. In HICs, there is more fiscal space, and purchasing power allows the policies to develop adolescent guarantees and to institutionalize auditing care experiences of broader financing frameworks. The difference between access and assurance is whether financing mechanisms related to adolescent-specific needs ensure the delivery of confidentiality, continuity, and privacy. If financing ignores adolescent-specific needs, then the cost in time, money, and trust rests with families, and the greatest benefit for system navigation is delivered to populations that are already privileged.

Equity and Intersectionality: From Recognition to Design

Equity language is now so prevalent in women’s health policy that it could be described as ubiquitous; however, the conversion of rhetoric into implementable policy and associated outcomes is severely uneven. In Australia, there has been an increased prevalence of intersectionality in the national strategy, and it explicitly states the needs of Indigenous women, migrants, women with disabilities, and LBTI populations [

30]. The situation in many low- and middle-income countries is often that equity is at some level of introduction, but due to the focus on poverty reduction or rural access, it often reflects the priorities of donors more than the context-based understandings of gender, culture, and identity [

27,

28,

29,

32].

Migration and displacement demonstrate some of the most jarring divides between recognition and design. Global frameworks of relevance, including WHO’s Promoting the health of refugees and migrants technical guidance, highlight adolescent migrant girls as a population at especially high risk of violence, sexual exploitation, and stagnated access to reproductive health services [

87]. Yet national policy responses remain fragmented, often focusing on maternal health broadly without tailoring entitlements for adolescents in migrant and refugee communities. Evidence from Europe indicates that first-generation migrant adolescents experience significant structural barriers to accessing confidential contraception and safe abortion, driven by legal restrictions, language challenges, and fears around anonymity and discrimination [

88,

89]. In contrast, second- and third-generation adolescents, while formally integrated into national health systems, often confront cultural stigma at home. These inherited beliefs can dissuade them from seeking early reproductive care or asserting their autonomy [

90].

Religious and cultural norms also shape the way policies are implemented, often in ways not explicitly acknowledged in official documents. In sub-Saharan Africa, the moral framing of adolescent sexuality has resulted in policies that emphasize abstinence and “responsible behaviour” rather than rights and agency [

91,

92,

93]. This approach perpetuates provider stigma and undermines confidentiality, as adolescents are frequently required to seek parental or spousal consent for contraceptives or safe abortion services [

72]. In Latin America, the influence of doctrines associated with Roman Catholic religious orthodoxy has historically constrained reproductive rights [

71], but harm-reduction models, such as in Uruguay and Argentina, have shown how policy innovation can navigate restrictive environments to expand adolescent access while reducing maternal mortality. These shifts demonstrate that cultural and religious contexts must be actively engaged in policy design, rather than being left as unacknowledged barriers to implementation.

Age itself is an axis of inequity that is often overlooked in equity frameworks. Adolescents are more biologically vulnerable than older women to complications such as eclampsia, obstructed labour, and postpartum haemorrhage, and are also more likely to experience long-term consequences of early childbearing, including obstetric fistula and mental health sequelae [

78,

79,

94,

95,

96]. Yet policies often frame adolescents as future mothers, rather than as individuals with present rights to autonomy and care. Older women, particularly those managing chronic conditions, are increasingly recognized in equity discussions, but the distinct risks of adolescents, particularly those who are poor, rural, migrant, or LBTI, remain less consistently operationalised in policy.

Equity frameworks that succeed, such as Baltimore’s trauma-informed maternal health initiative or Spain and Brazil’s laws addressing gender violence, do so by explicitly linking health to broader social determinants such as housing, employment, education, and legal protection [

42,

43]. However, few policies in LMICs operationalize this level of integration, leaving adolescents exposed to compounded risks. Without funded outreach mechanisms such as peer navigators, interpreters, mobile clinics, or school-linked services, equity commitments remain aspirational. Policies that stop at recognition, without dedicated budgets, measurable targets, and adolescent-specific accountability systems, perpetuate structural inequities even while claiming to be rights-based.

In sum, intersectionality in women’s health policies remains more often an aspirational principle than a lived reality for adolescents and young women. Migrants, diaspora communities, Indigenous populations, and sexual minorities are acknowledged in global frameworks but rarely prioritized in domestic financing or service delivery. Religion and culture are powerful forces shaping adolescent care experiences, yet policy documents often treat them as invisible. And while equity commitments for older women are gaining traction in some settings, adolescents, arguably the group at highest biological and social risk, remain on the periphery of policy design. Bridging this gap requires equity frameworks that move beyond recognition to concrete design features: dedicated adolescent budgets, culturally responsive outreach, and accountability systems that monitor not just access but also the experience of care.

Measurement and Accountability

Measurement remains one of the most underdeveloped components of women’s health policy, particularly in relation to adolescents and young women. Most monitoring frameworks aggregate outcomes under the broad category of “women of reproductive age,” obscuring the distinctive risks and needs of adolescents [

58]. As a result, adolescent outcomes such as contraceptive uptake, continuity of care, confidentiality, and experience of stigma remain invisible within official statistics. The absence of age-disaggregated data not only undermines accountability but also sustains the misconception that adolescent health can be subsumed under maternal frameworks [

97]. Few countries systematically disaggregate adolescent outcomes. Rwanda and Sierra Leone attempted to include adolescent indicators in their monitoring systems, but weak data infrastructures constrained follow-through [

38,

44]. Bhutan and Nepal highlighted adolescent participation in strategy design, but evaluation frameworks remained limited [

34,

45]. High-income contexts such as Sweden and the UK progressively integrated adolescent-sensitive equity metrics within national women’s health strategies, demonstrating the potential of data systems to make adolescent commitments visible [

35,

68].

High-income countries with robust health information systems, such as Australia, Canada, and members of the European Union, have been able to incorporate more granular measures of equity, including Indigenous identity, rurality, and sexual orientation, into their monitoring frameworks. This has enabled policymakers to identify service gaps and adapt programs accordingly [

98,

99]. In contrast, many LMICs rely heavily on donor-driven surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which, while valuable, are conducted every five years or more and are not designed to track programmatic performance in real time. The reliance on episodic, externally funded surveys means that ministries of health often lack routine indicators to monitor adolescent service quality, confidentiality, or continuity of care [

100].

Emerging frameworks suggest that accountability for adolescent health requires a multidimensional approach. Indicators should be disaggregated not only by age but also by gender identity, rurality, migration status, and disability, to capture intersectional inequities [

101]. Metrics must extend beyond service utilization to include experience of care, particularly around confidentiality, perceived stigma, and decision-making autonomy [

51,

102]. Facility-level audits should examine readiness to deliver adolescent-friendly services, including private counselling arrangements, flexible clinic hours, and staff training. Importantly, accountability should not be conceived solely as top-down monitoring but must include mechanisms for youth-side participation: advisory councils, peer scorecards, hotlines, and grievance redress platforms can ensure that adolescent voices are systematically heard and acted upon [

103,

104,

105,

106].

Without these changes, measurement risks remaining a bureaucratic exercise that reinforces invisibility rather than a tool for equity. Adolescents and young women will continue to be lost in aggregated categories, their rights diluted into broader maternal indicators. For policies to move from rhetoric to assurance, measurement systems must evolve from static, donor-driven cycles toward dynamic, participatory frameworks that make adolescents visible, track their outcomes in real time, and enforce accountability when commitments are unmet.

Practice and Policy Implications

The findings of this review suggest that translating equity and rights commitments into tangible improvements for adolescents and young women requires a shift from aspirational policy language toward enforceable entitlements, backed by financing and measurable accountability. Ministries of health in both high- and low-income settings often publish comprehensive strategies that acknowledge adolescent needs, yet in the absence of regulatory mandates and budgetary allocations, these commitments remain rhetorical [

53,

107]. For example, Ghana’s experience with delivery fee exemptions underscores that policy intent alone cannot guarantee adolescent access when reimbursement systems falter and informal costs re-emerge [

33]. Similarly, in Nigeria, results-based financing rewarded states with stronger health system capacity but widened inequities for adolescents in fragile regions, highlighting the risks of financing models that prioritize efficiency over equity [

36].

In practice, this means that ministries must move beyond general commitments to “youth-friendly care” and instead codify adolescent entitlements within regulations, service contracts, and provider payment systems. Confidential access to contraception, safe abortion where legal, mental health first response, and care post-violence should not depend on the discretion of individual providers but should be enshrined as minimum service guarantees. These guarantees require clear age-specific targets and should be accompanied by provider training and supervision mechanisms that reinforce non-judgmental care [

108,

109].

For implementers, the priority lies in ensuring that frontline delivery systems reflect adolescent realities. Adolescents face unique barriers related to privacy, time, and stigma; thus, small but crucial adjustments such as designated clinic hours for youth, private counselling rooms, opt-out chaperone policies, and reliable contraceptive supplies can significantly influence care-seeking behaviours [

50,

110]. Experience from Argentina’s harm-reduction abortion model shows that when primary care services are funded and normalized for adolescents, outcomes improve rapidly and sustainably [

37].

Development partners also have a role to play, but must avoid perpetuating donor-driven distortions. Too often, external funding emphasizes vertical, target-driven approaches that prioritize aggregate maternal outcomes while neglecting adolescent-specific indicators [

111,

112]. Instead, partners should support the development of national health information systems that routinely capture age-disaggregated data, invest in training curricula for adolescent-friendly services, and strengthen model clinics that can demonstrate best practice. Critically, financial support should be tied to accountability mechanisms that measure adolescent experience of care and equity across intersecting identities, rather than only service utilization numbers.

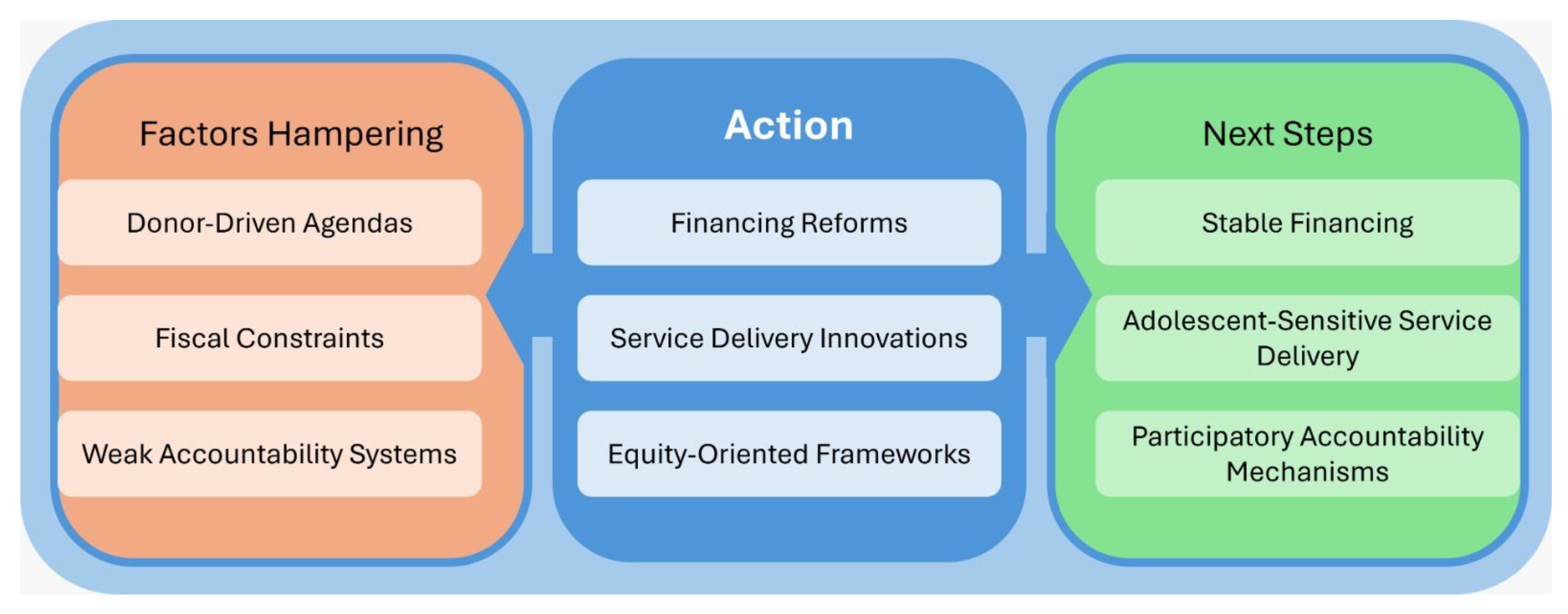

Figure 4.

Barriers, Policy Actions, and Future Priorities for Adolescent and Young Women’s Health in Global Policies.

Figure 4.

Barriers, Policy Actions, and Future Priorities for Adolescent and Young Women’s Health in Global Policies.

Research and Evaluation Priorities

A striking finding from this review is the paucity of rigorous evaluation of women’s health policies, particularly in relation to adolescents and young women. High-income countries have been able to leverage strong health information systems, maternal mortality review committees, and longitudinal data sources, which enable them to assess both outcomes and equity impacts [

113,

114]. In contrast, many low- and middle-income countries continue to rely on episodic, donor-funded evaluations, such as Demographic and Health Surveys. While these surveys are useful for identifying broad trends, they do not capture program fidelity, implementation challenges, or adolescent-specific outcomes [

115,

116]. This results in a pattern where policies are launched with considerable fanfare but fade from visibility once donor funding ends, creating a cycle of aspirational commitments without sustained learning.

The absence of systematic evaluation cycles means that many policies in LMICs are not revisited, updated, or revised in light of new evidence. For example, Ghana’s free delivery exemptions were adopted without robust cost-effectiveness studies, and when reimbursement challenges undermined sustainability, there was little institutional mechanism to document lessons learned or redesign the intervention [

117,

118]. Similarly, in Nigeria, results-based financing was rolled out nationally despite limited evaluation of how such models might affect adolescents in fragile or resource-poor states [

36,

119]. Without intentional evaluation frameworks, these policy experiments risk repeating mistakes rather than generating cumulative knowledge.

Research gaps are also visible in the domains of confidentiality, stigma reduction, and youth participation. While global evidence supports the value of youth-friendly services, very few studies measure the mechanisms by which provider attitudes, privacy protections, or peer-led models affect adolescent health-seeking behaviour [

103,

104,

105,

106]. Implementation science approaches, which can explain not just whether policies work but how and why, are underutilized in LMIC contexts where they are most needed [

120]. Moreover, academic research is often siloed from policy processes, with findings remaining in journals rather than feeding into policy revisions. This disconnect results in duplication of effort and perpetuates gaps in adolescent-specific programming [

121].

Moving forward, a more holistic approach to research and evaluation is needed—one that goes beyond content analysis of policies and emphasizes the processes by which policies are developed, implemented, and adapted. Academics should be embedded within policymaking cycles, working alongside ministries to design evaluation frameworks, analyse disaggregated data, and co-produce knowledge that can directly inform revisions. At the same time, participatory methods that engage adolescents and young women as co-researchers are critical to ensure that evidence reflects lived realities and not just bureaucratic indicators.

Finally, research funders and global health institutions should prioritize building local capacity for policy evaluation in LMICs, including training in implementation science, establishing open-access policy repositories, and ensuring that evaluations are systematically published and accessible. Without these investments, the cycle of donor-driven, short-lived policies will persist, and adolescents will remain marginal in both the evidence base and the reforms it informs.

Conclusions

This review of 48 national and international women’s health policies demonstrates that while global frameworks such as CEDAW, the ICPD Programme of Action, the Beijing Platform for Action, and the Sustainable Development Goals have pushed agendas toward equity and rights, adolescents and young women remain inconsistently prioritized in practice. Across contexts, financing reforms, service delivery innovations, and equity-oriented frameworks have produced gains, but these gains are uneven and fragile, often diluted by donor-driven agendas, fiscal constraints, or weak accountability systems. High-income countries have made greater progress in embedding intersectionality and adolescent entitlements within policy frameworks, yet even in these contexts, gaps in implementation persist. In low- and middle-income countries, the structural limitations of health financing, service delivery, and evaluation have left adolescents particularly vulnerable to hidden costs, stigma, and fragmented services.

The implications are clear: adolescents and young women must be recognized as rights-holders within health systems, with explicit guarantees for confidentiality, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health, mental health, and protection from violence. Policy rhetoric must translate into enforceable design features backed by stable financing, adolescent-sensitive service delivery, and participatory accountability mechanisms. Future progress will depend on strengthening policy evaluation cycles, embedding implementation science in LMICs, and fostering co-production between academics, policymakers, and young people themselves. Only through these shifts can global and national policies move beyond symbolic recognition and begin to realize the transformative potential of equity and rights for adolescents and young women across diverse contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care, or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

The data shared within this manuscript is publicly available.

Code availability

Not applicable

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and conceptualised this paper as part of the KATHERINE project. GD wrote the first draft and furthered it by all other authors. All authors critically appraised, reviewed, and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

No participants were involved in this paper

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

References

- Remme M, Vassall A, Fernando G, Bloom DE. Investing in the health of girls and women: a best buy for sustainable development. BMJ 2020, 369, m1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert KG, Bird CE, Kozhimmanil K, Wood SF. To Address Women’s Health Inequity, It Must First Be Measured. Health Equity 2022, 6, 881–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. platform.who.int. 2023. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health Data Portal. Available online: https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/global-strategy-data.

- Morris JL, Rushwan H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: The global challenges. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2015, 131, S40–2. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SD, Seeley J. Grand Challenges in Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. Front Reprod Health. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar]

- INFORMATION SERIES ON SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS UPDATED 2020 ADOLESCENTS [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/SexualHealth/INFO_Adolescents_WEB.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Michaels Aibangbee, Sowbhagya Micheal, Pranee Liamputtong, Rashmi Pithavadian, Hossain SZ, Mpofu E, et al. Barriers to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Migrant and Refugee Youth: An Exploratory Socioecological Qualitative Analysis. Youth 2024, 4, 1538–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratislava, S. A UNFPA Strategy for Gender Mainstreaming in Areas of Conflict and Reconstruction [Internet]. 2002. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/impact_conflict_women.pdf.

- Manar Shalak, Markson F, Manoj Nepal. Gender-Based Violence and Women Reproductive Health in War Affected Area. Korean J Fam Med 2024, 45, 12–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishwajit G, Sarker S, Yaya S. Socio-cultural aspects of gender-based violence and its impacts on women’s health in South Asia. F1000Research 2016, 5, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations. 2025. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- www.unfpa.org [Internet]. 2014. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/resources/adolescent-sexual-and-reproductive-health.

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2025. Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1.

- Loveless, G. Ballard Brief. 2025. Ballard Brief. Available online: https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/barriers-to-adequate-healthcare-for-women-in-the-united-states.

- Hopkins J, Narasimhan M, Aujla M, Silva R, Mandil A. The importance of insufficient national data on sexual and reproductive health and rights in international databases. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 70, 102554–102554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam N, Merry L, Browne JL, Nahar Q. Editorial: Adolescent sexual and reproductive health challenges in low-income settings. Front Public Health. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar]

- www.unicef.org [Internet]. 2020. Early marriage and its devastating effects. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/southsudan/stories/early-marriage-and-its-devastating-effects.

- Chandra-Mouli V, Akwara E. Improving access to and use of contraception by adolescents: What progress has been made, what lessons have been learned, and what are the implications for action? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol [Internet] 2020, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Zangeneh Jolovi S, Tarrahi MJ, Safdari Dehsheshmeh F, Nekuei NS. Barriers to Sexual Health Education for Female Adolescents in Schools from Health Care Providers’ perspective. J Midwifery Reprod Health 2023, 11, 3694–703. [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet] 2021, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Int J Surg 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med [Internet] 2009, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall, J. AACODS Checklist [Internet]. Adelaide, Australia: Flinders University; 2010. Available online: https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/xmlui/handle/2328/3326.

- United Nations. OHCHR. United Nations; 1979. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York, 18 December 1979. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women.

- UNFPA. www.unfpa.org. 2014. International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/publications/international-conference-population-and-development-programme-action.

- UN Women. UN Women. 2015. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, Beijing +5 Political Declaration and Outcome. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/01/beijing-declaration.

- Population and Reproductive Health Policy [Internet]. Ministry of Health, Indigenous Medicine in 1998; 1998. Available online: https://www.health.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/3_Population-and-Reproductive-1.pdf.

- National Maternal and Child Health Policy Sri Lanka [Internet]. 2012. Available online: https://www.aidscontrol.gov.lk/images/publications/national_maternal_and_child_health_policy.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- National Reproductive Health Service Policy and Standards [Internet]. Republic of Ghana; 2014. Available online: https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/policy/gha-cc-10-01-policy-2014-eng-national-reproductive-health-service-policy-and-standards.pdf.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Australian Government Department of Health. 2021. National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-womens-health-strategy-2020-2030.

- Improving the health care of pregnant refugee and migrant women and newborn children [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/342289/9789289053815-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Richey, LA. Women’s Reproductive Health & Population Policy: Tanzania. Rev Afr Polit Econ 2003, 30, 273–92. [Google Scholar]

- Professor David Ofori-Adjei. Ghana’s Free Delivery Care Policy. Ghana Med J 2007, 41, 94. [Google Scholar]

- National Medical Standard For Reproductive Health Volume I: Contraceptive Services Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population Family Welfare Division [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/national_medical_standard-_final.pdf.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden. National Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) [Internet]. Solna & Östersund, Sweden; 2022. Available online: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/5ced6a64b90f44ccb0dc56564e701ea1/national-strategy-sexual-reproductive-health-rights-srhr.pdf.

- World Bank [Internet]. World Bank Project : Nigeria - Program to Support Saving One Million Lives - P146583. Available online: https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P146583.