Introduction

Social media platforms have become the dominant gateway to information, entertainment, and peer interaction for today’s young adults. In Egypt, where internet penetration now exceeds 80 % and some 50.7 million social media accounts were active in January 2025 (43 % of all residents and the vast majority of 18 to 24 year-olds), undergraduate students inhabit a mobile-first landscape of sustained online interaction [

1].

The term “social media” describes the ways in which individuals connect with one another through the creation, sharing, and/or exchange of ideas and information inside online communities and networks [

2]. When referring to “media” the term “social” implies that the platforms are user-focused and facilitate group interaction. Social media can be understood as virtual human network facilitators or enhancers, offering services via mobile devices or web-based apps, with leading platforms including Facebook (and Messenger), Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok [

3]. Since its inception, social media has seen rapid uptake (e.g., Facebook reported one billion global users in November 2012), and today anyone with an internet connection may access unlimited material, expanding their personal knowledge base [

4]. Yet while social media removes barriers to communication and supports decentralized channels for democratic participation, it can also negatively impact wellbeing by increasing anxiety, depression, loneliness, fear of missing out, and cyberbullying. In 2020, 44 % of U.S. internet users reported experiencing online harassment, and the addictive nature of these platforms, driven by dopamine boosts from likes and shares, can erode self-esteem when expected approval is absent [

5].

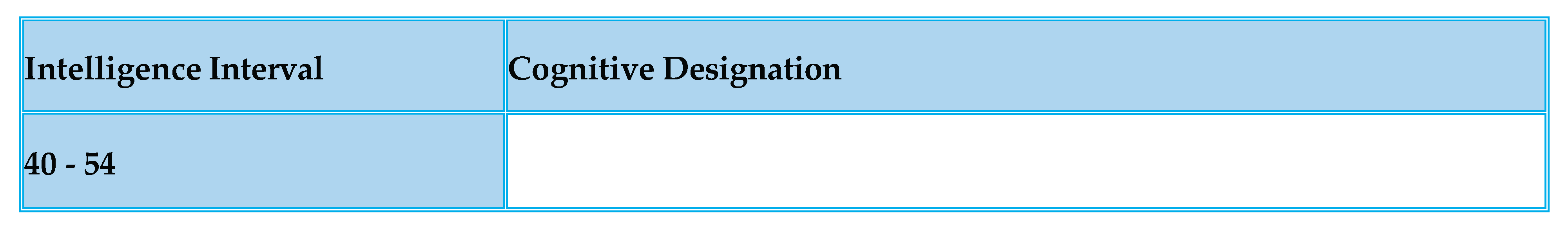

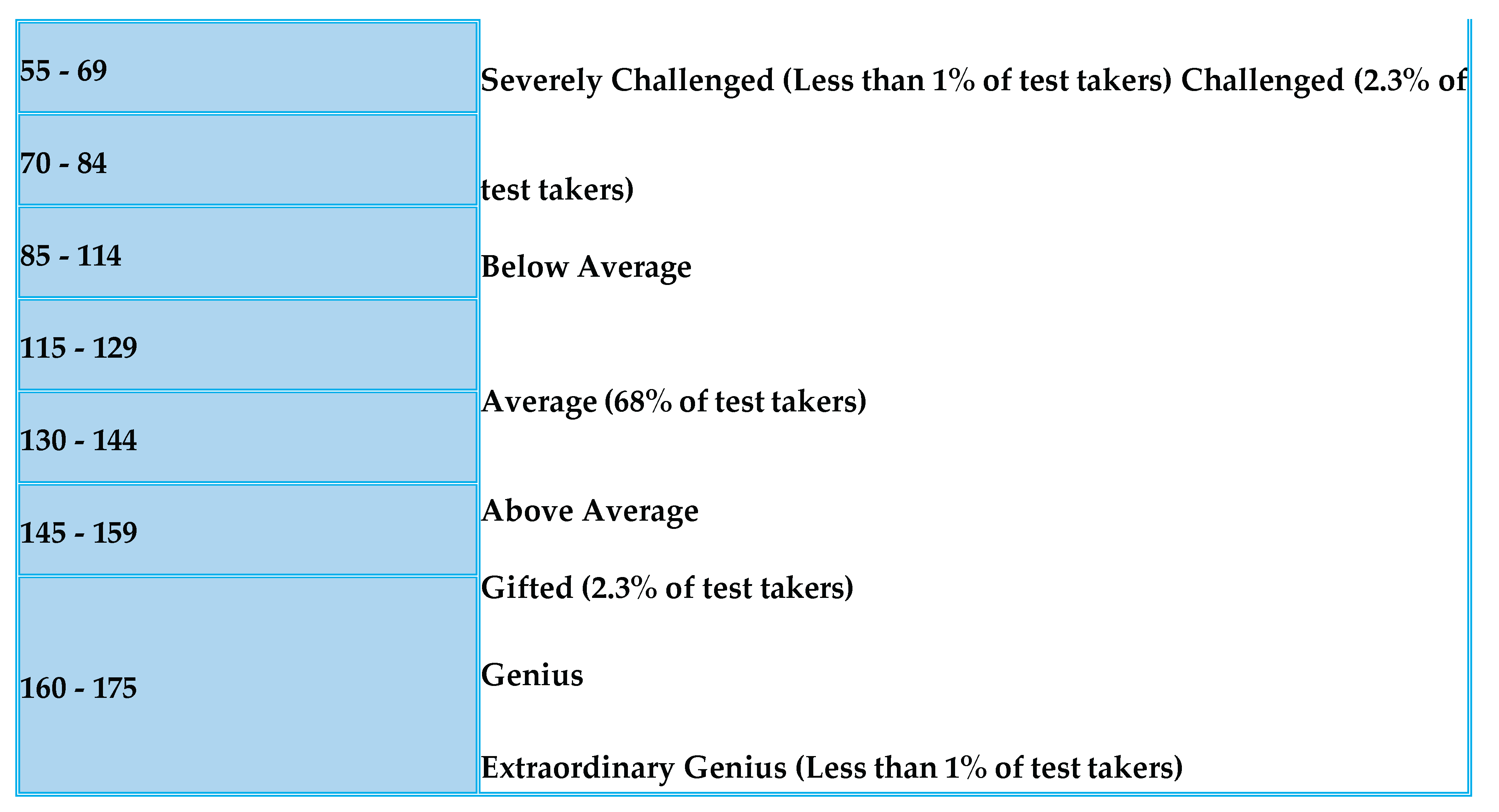

Intelligence quotient (IQ), a widely used but partial measure of cognitive ability, originated with Alfred Binet’s 1905 test, which assessed memory, attention, and problem-solving to assign a “mental age”. Over time, the development of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children and the Stanford-Binet Scales refined IQ assessment into the dual verbal and non-verbal tasks familiar today [

6]. IQ scores between 90 and 109 indicate average intelligence (encompassing about 68 % of the population), while scores above 130 signal exceptional giftedness, and only about 2 % of individuals exceed this threshold [

7]. Although some historical figures are later estimated to have had IQs around 160, and organizations like the Giga Society report extraordinary scores (for example, 276 in April 2024), IQ remains just one facet of human intellect, omitting emotional, social, and creative dimensions, and is itself subject to change through education and experience [

8].

Egypt provides a compelling case study for examining the cognitive consequences of pervasive digital engagement. Prospective studies from North America, Europe, and East Asia have reported modest associations between prolonged screen time and deficits in processing speed, working memory, and attention, though findings vary once confounders like physical activity, sleep, and socioeconomic status are controlled, and almost all derive from high-income settings [

9,

10]. To date, no study has quantified the relationship between habitual social media use and objective measures of cognitive performance in Egyptian undergraduates.

Against this backdrop, we conducted a multi-faculty, cross-sectional study testing the hypothesis that longer daily social media screen time is independently associated with lower IQ scores among Egyptian university students, after adjusting for key demographic and academic factors. By providing the first region-specific estimate of this exposure-response relationship, our goal is to benchmark Egyptian data against international effect sizes and to identify modifiable behavioral targets for campus health-promotion programs.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This cross-sectional study was conducted between December 2023 and May 2024 among undergraduate students in Egypt. Participants were eligible if they were aged 18-24 years, enrolled in an accredited undergraduate program, and active users of social media platforms (e.g., Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, X, Reddit). Exclusion criteria included a known diagnosis of neurological or developmental disorders (e.g., epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability), non-residency in Egypt, and incomplete responses.

Data Collection

Data were collected through an online survey distributed via academic and student networks. The survey comprised three sections:

1. Sociodemographic data: Age, gender, nationality, academic major, GPA, and first language.

2. Digital media use: Self-reported average daily social media screen time (validated by a screenshot when available), types of platforms used, and phone-related behaviors (e.g., distractibility, dependence).

3. Cognitive assessment: Participants completed a 20-item IQ test hosted on [

www.free-iqtest.net] (https://

www.free-iqtest.net), previously cited in peer-reviewed literature assessing verbal reasoning, logic, and problem-solving domains.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Quantitative variables were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess the relationship between social media screen time and IQ scores. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

Participation was anonymous and voluntary. No identifiable personal data were collected. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Committee of Misr University for Science and Technology.

Results

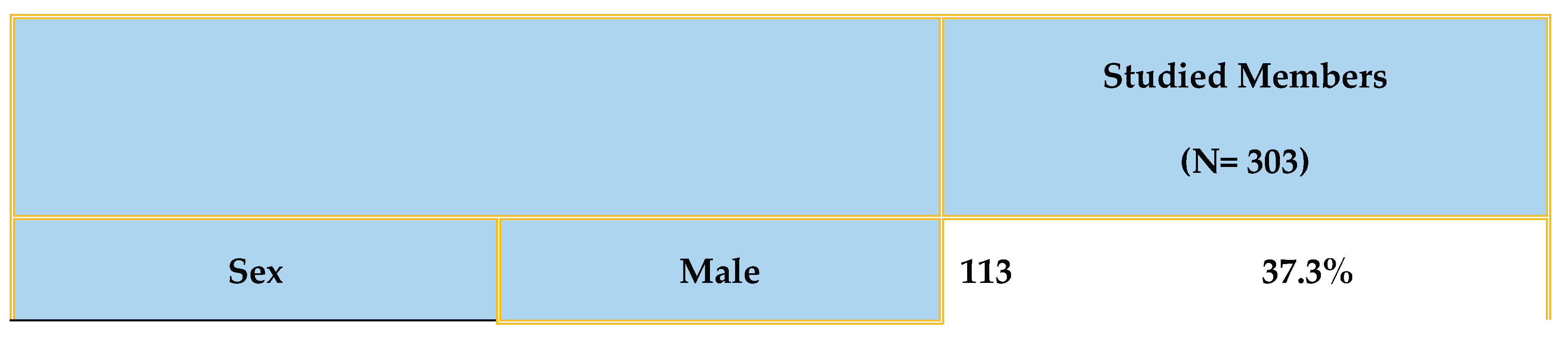

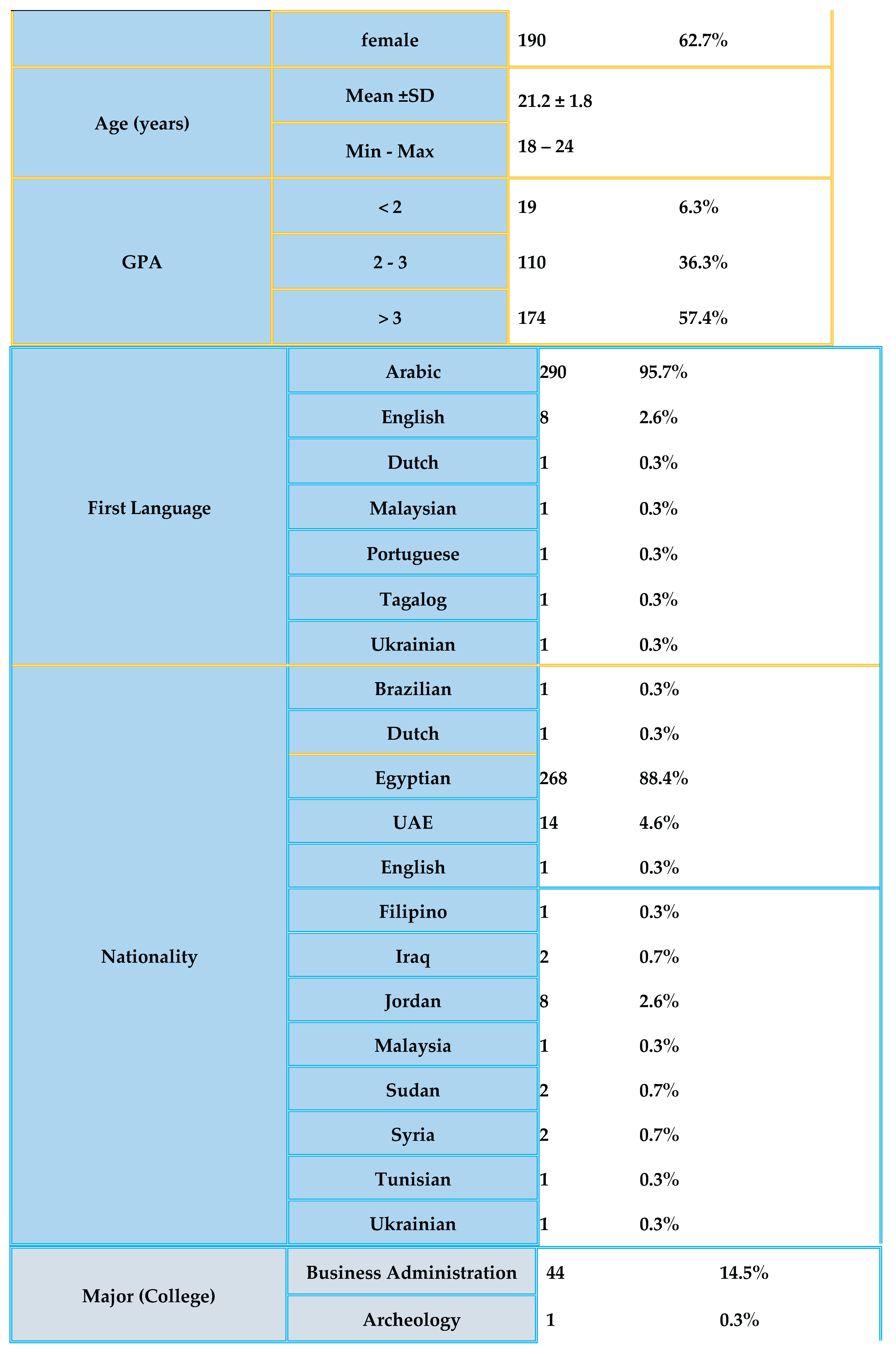

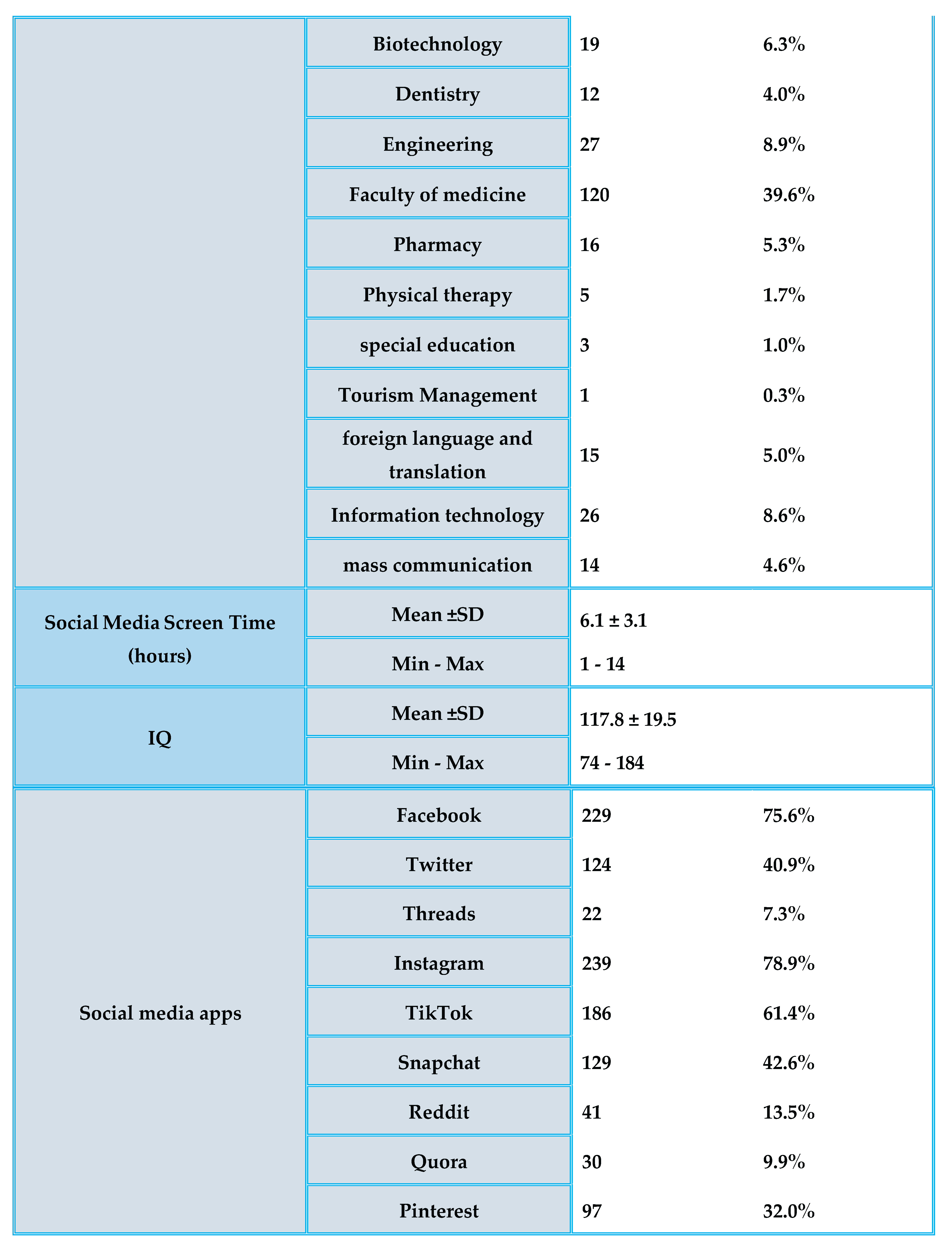

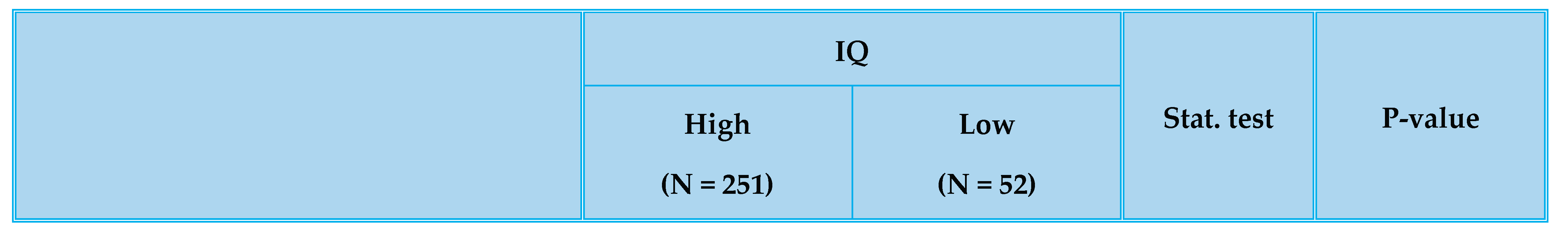

Of 327 respondents, 303 met all the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. Mean age was

21.2 ± 1.8 years (range 18–24);

62.7 % were female. Almost all participants reported Arabic as their first language (95.7 %), and 88.4 % held Egyptian nationality, with the remainder drawn chiefly from other Middle Eastern countries

. Medicine was the most common major (39.6 %), followed by business administration (14.5 %) and engineering (8.9 %). Grade-point average (GPA) was ≥3.0 in 57.4 % of students, 2.0–2.99 in 36.3 %, and <2.0 in 6.3 %. Among all participants, Instagram (78.9%) and Facebook (75.6%) were the most used apps, followed by TikTok (61.4%) and Snapchat (42.6%). Average daily social media screen time was

6.1 ± 3.1 h (range 1–14 h). Mean IQ score, assessed with the 20-item online test, was

117.8 ± 19.5 (range 74–184) (

Table 1). Most students fell within the

average (IQ 90–109; 34 %) or

above-average (IQ 110–129; 28 %) categories; 10 % scored ≥130 (

superior), whereas 5 % scored <90 (

Table 2).

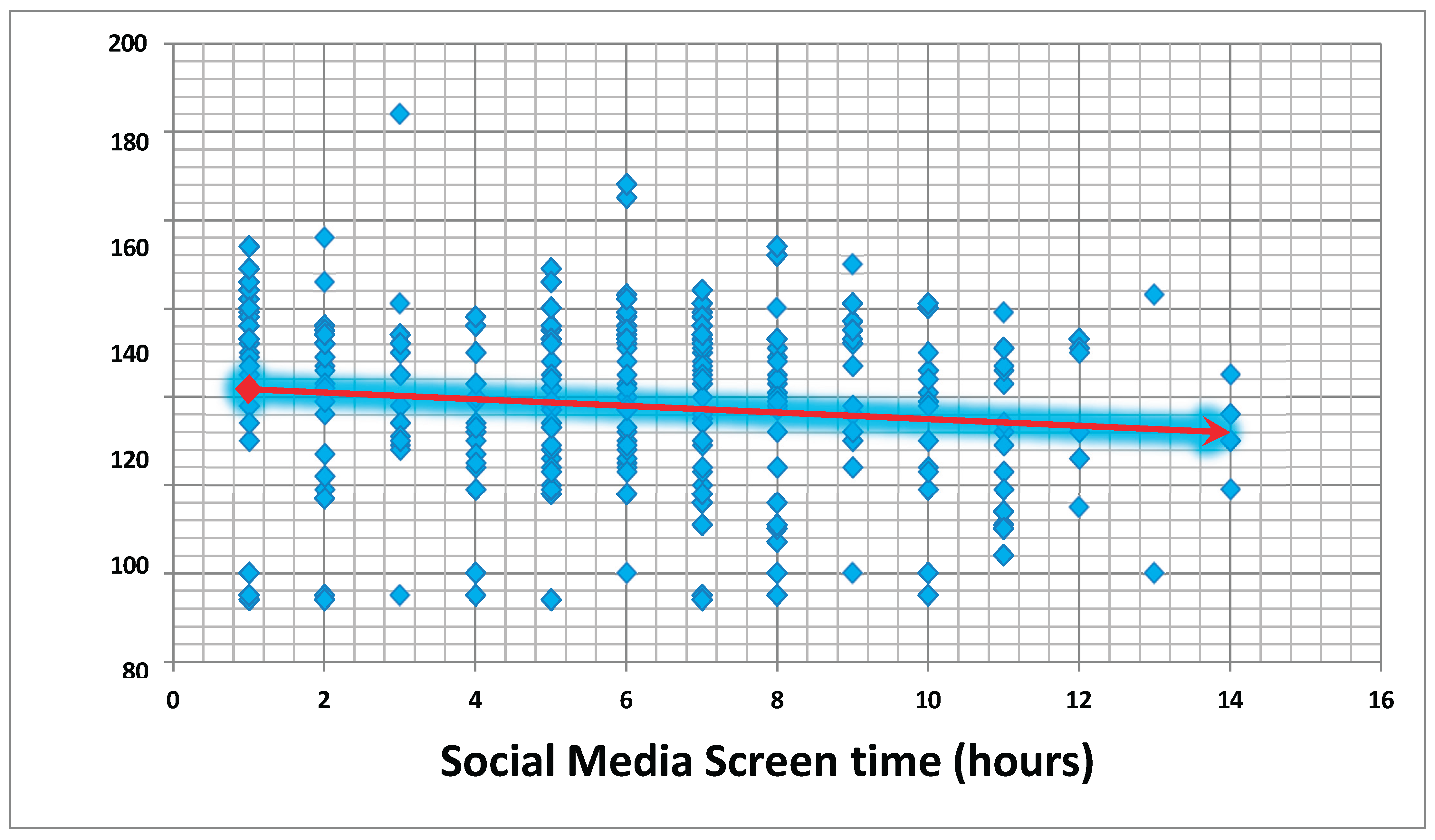

Pearson correlation showed a

significant inverse association between social-media screen-time and IQ (

r = -0.12,

p = 0.037) (

Figure 3). Among IQ categories, a statistically significant difference was found only in sex distribution (p = 0.044), with a higher proportion of females in both groups, especially among Low IQ members. Other variables like age, nationality, language, college major, and screen time showed no significant differences (

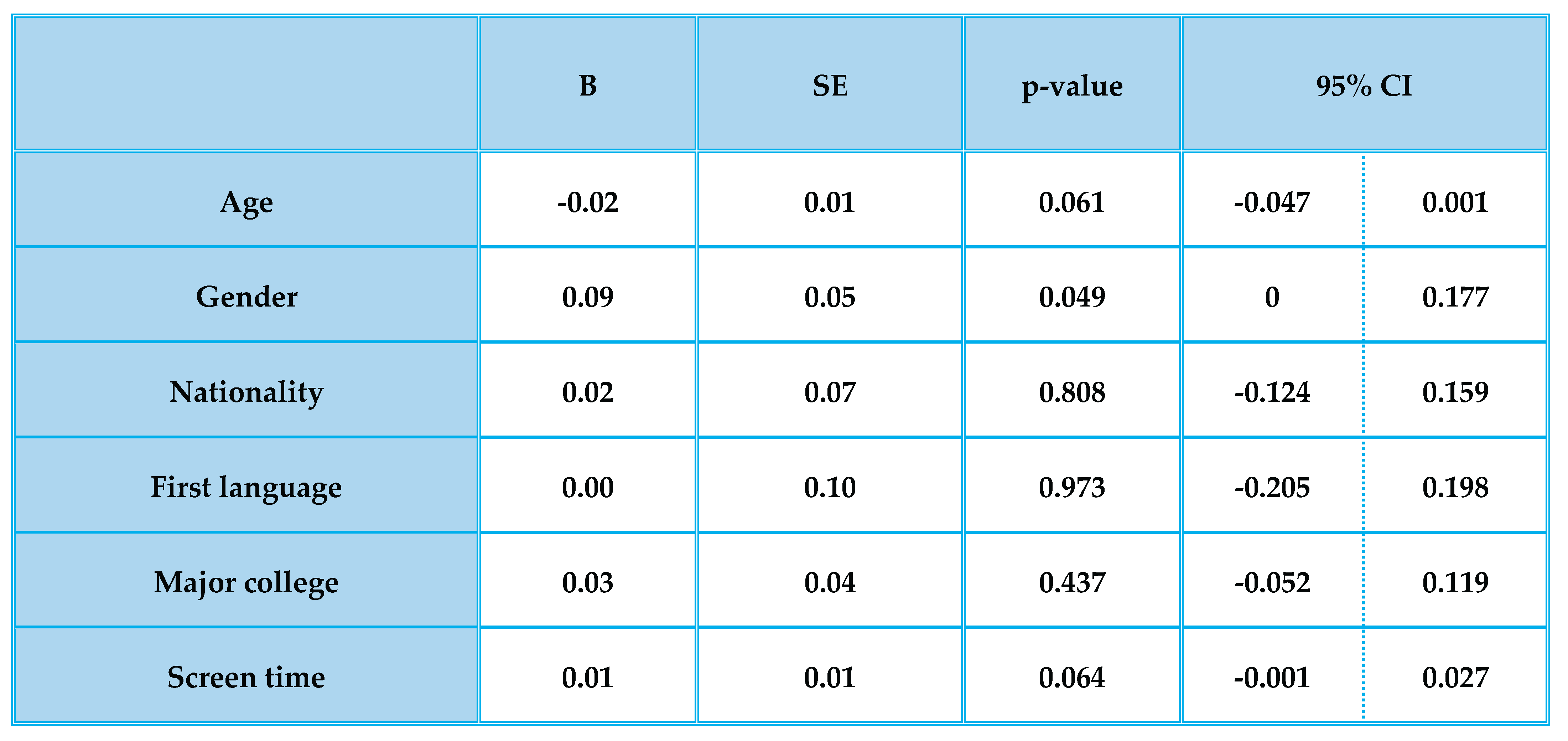

Table 4). A univariate logistic regression model showed that none of the studied factors (age, gender, nationality, first language, college major, or screen time) significantly predicted Low IQ. All variables had p-values greater than 0.05, indicating no predictive value (

Table 5).

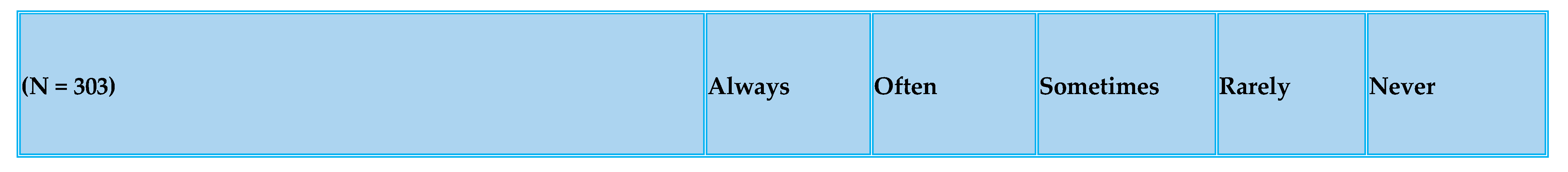

Phone-related behaviors were pervasive. More than half of students reported that push-notifications

“often” (34.7 %) or “always” (26.7 %) distracted them while studying. The prospect of being without their phone caused distress in 46.9 % (“often/always”). One-third (33.3 %) “often” struggled to recall academic material or everyday information, and another 31.4 % experienced this “sometimes.”

Two-thirds regarded themselves as phone-addicted (46.2 % “agree,” 20.5 % “strongly agree”). Despite these concerns,

52.8 % believed social-media use had an overall positive impact on their lives (

Table 6).

Together, these data show that Egyptian undergraduates spend an average of six hours per day on social media and that even this modest range of exposure is associated with measurable, albeit small, reductions in IQ performance, independent of key demographic and academic factors. High rates of self-perceived phone addiction and distraction underscore the behavioral prominence of digital engagement in this population.

Discussion

This study is among the first to empirically investigate the relationship between social media screen time and intelligence quotient (IQ) scores in a university-aged population. Our findings indicate a statistically significant negative correlation between daily social media use and IQ, suggesting that prolonged digital engagement may be modestly associated with reduced cognitive performance.

These results are consistent with neurodevelopmental research showing that excessive screen exposure, especially during formative years, can alter functional brain activity in regions responsible for attention, memory, and executive function [

11]. For instance, longitudinal neuroimaging studies have identified heightened reactivity in the amygdala and decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex among adolescents with frequent social media use, both of which are critical to cognitive regulation [

12].

Our findings also align with evidence from early childhood studies that link screen time to reduced full-scale IQ (FSIQ), verbal reasoning, and working memory scores [

13]. A recent scoping review of 44 international studies likewise underscores that chronic digital media use is associated with impaired learning, delayed language acquisition, and structural brain changes, particularly in the prefrontal regions [

14].

Beyond biological explanations, behavioral factors likely contribute. The frequent cognitive interruptions caused by app notifications, multitasking, and passive scrolling may reduce deep learning and memory consolidation, particularly among students [

15]. Our data support this, with over 60% of participants reporting frequent distraction and phone-related distress.

Taken together, these results emphasize the need for balanced digital habits in academic settings. Universities may benefit from incorporating digital hygiene education and promoting awareness around screen time self-regulation. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are warranted to further clarify causality and develop evidence-based guidelines for digital media use in young adults.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inference between social media use and cognitive outcomes. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the directionality and persistence of the observed associations. Second, the IQ test used, while validated in prior studies, was limited in scope and duration, potentially underestimating the complexity of cognitive function. The lack of a standardized clinical IQ assessment may affect generalizability. Third, the sample was recruited through convenience sampling, primarily from Egyptian medical and business faculties, which may limit generalizability to other academic disciplines or cultural contexts. Finally, confounding variables such as sleep duration, physical activity, mental health status, and academic workload were not controlled for, which may influence both screen time and cognitive performance.

Conclusion

This study provides initial empirical evidence of a statistically significant negative correlation between social media screen time and IQ scores among Egyptian undergraduate students. Although the effect size was modest, the findings align with growing neuroscientific and behavioral research suggesting that excessive digital engagement may adversely impact attention, memory, and cognitive efficiency. Given the widespread use of social media in academic and personal contexts, these findings contribute to the understanding of how screen-based behaviors may relate to cognitive functioning.

References

- Kemp S. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights [Internet]. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2025-egypt.

- Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! the Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons [Internet]. 2010 Oct 13 [cited 2025 Jul 10];53(1):59–68. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0007681309001232?via%3Dihub.

- Dewing M. Social Media: An Introduction [Internet]. www.publications.gc.ca. 2010 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/bdp-lop/eb/2010-3-eng.pdf.

- Amedie J. The Impact of Social Media on Society [Internet]. Santa Clara University; 2015 Sep [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=engl_176.

- Bounds D. Social Media’s Impact on Our Mental Health and Tips to Use It Safely [Internet]. UC Davis Health. UC Davis Health; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://health.ucdavis.edu/blog/cultivating-health/social-medias-impact-our-mental-health-and-tips-to-use-it-safely/2024/05.

- Kendra Cherry. How Are IQ Scores Interpreted? [Internet]. Verywell Mind. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/how-are-scores-on-iq-tests-calculated-2795584.

- Kumar K, Allarakha S. What Is the Normal Range for IQ? Chart [Internet]. MedicineNet. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.medicinenet.com/what_is_the_normal_range_for_iq/article.htm.

- Batra N. Top 10 Highest IQ Ever Recorded [Internet]. Jagranjosh.com. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/list-of-people-with-highest-iqs-1694766316-1.

- Hassan MM, Orebi HA, Salama B, Kabbash IA. The association of social media use and other social factors with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Egyptian university students. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2025 Jan 7 [cited 2025 Jul 10];25(1). Available from: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-024-05988-6.

- Shalash RJ, Arumugam A, Qadah RM, Al-Sharman A. Night Screen Time is Associated with Cognitive Function in Healthy Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare [Internet]. 2024 May 6 [cited 2025 Jul 10];17:2093–104. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/night-screen-time-is-associated-with-cognitive-function-in-healthy-you-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-JMDH#:~:text=Two%20studies%20involving%20older%20adults.

- Meri R, Hutton J, Farah R, DiFrancesco M, Gozman L, Horowitz-Kraus T. Higher access to screens is related to decreased functional connectivity between neural networks associated with basic attention skills and cognitive control in children. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence [Internet]. 2022 Aug 11 [cited 2025 Jul 10];29(4):666–85. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35957604/.

- Maza MT, Fox KA, Kwon SJ, Flannery JE, Lindquist KA, Prinstein MJ, et al. Association of Habitual Checking Behaviors on Social Media With Longitudinal Functional Brain Development. JAMA Pediatrics [Internet]. 2023 Jan 3 [cited 2025 Jul 10];177(2):160–7. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2799812.

- Zhao J, Yu Z, Sun X, Wu S, Zhang J, Zhang D, et al. Association Between Screen Time Trajectory and Early Childhood Development in Children in China. JAMA Pediatrics [Internet]. 2022 Jun 6 [cited 2025 Jul 10];176(8):768–75. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9171655/#H1-1-POI220027.

- Neophytou E, Manwell LA, Eikelboom R. Effects of excessive screen time on neurodevelopment, learning, memory, mental health, and neurodegeneration: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction [Internet]. 2019 Dec 16 [cited 2025 Jul 10];19(3):724–44. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11469-019-00182-2#Abs1.

- Chen Q, Yan Z, Mariola Moeyaert, Bangert-Drowns R. Mobile Multitasking in Learning: A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Mobilephone Distraction on Young Adults’ Immediate Recall. Computers in Human Behavior [Internet]. 2024 Sep 12 [cited 2025 Jul 10];162:108432–2. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563224003005?via%3Dihub.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).