1. Introduction

In recent years, several cloud computing platforms have been implemented, offering on-demand technical infrastructure, storage services, software packages, and computing power to handle large volumes of data processing and calculations [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Google Earth Engine (GEE), introduced by Google in 2010, is one of the most widely recognized platforms in remote sensing-related research. It is designed for storing, accessing, and analyzing a vast collection of remotely sensed data and geospatial datasets [

5,

6,

7]. GEE provides a wide range of datasets, including both pre-processed and raw data, as well as freely accessible satellite products at global, national, and regional scales [

8,

9,

10]. It archives a massive amount of remote sensing satellite data gathered over the past 40 years from major land monitoring sensors, including Landsat, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Sentinel, and Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS), among other datasets [

11] such as atmospheric, environmental, natural resources, and terrain datasets that serve as fundamental data for multi-disciplinary research and applications [

10].

Two other popular cloud computing platforms incorporate remotely sensed data from multiple satellites and provide Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) tools for analyzing environmental issues. These cloud-based platforms, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft Azure [

12,

13,

14] provide access to open remotely sensed data from various satellites using several technical tools. AWS involves Landsat-8, Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, China–Brazil Earth Resources Satellite program, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) image datasets, open data supplied by DigitalGlobe, and global model outputs [

7,

12,

15]. On the other hand, Azure provides Landsat and Sentinel-2 products for North America since 2013, along with Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) data since 2000 [

12,

13,

15,

16,

17]. Compared to them, GEE provides significantly larger volumes of remotely sensed datasets. GEE offers a broader range of geospatial datasets, including Sentinel, recent and historical archive (since 1972) of Landsat datasets, among many other remote sensing satellites' missions data, and provides services free of charge to all researchers [

14,

18,

19,

20].

Table 1 presents a detailed comparison between the three mentioned platforms in the context of remote sensing, highlighting GEE's unique features and advantages over its competitors.

While AWS and Azure are both robust platforms, their limited capabilities may not enable them to fully replace GEE, given its broad and openly accessible geospatial data and tools. This was reflected by the continued high usage of GEE by researchers, as noted in the literature. GEE is widely utilized in urbanization, sustainability, and environmental research studies due to its cloud-based geospatial processing abilities, online user access, and accessibility to extensive geospatial datasets [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Furthermore, it is also the most widely used online geospatial platform in land monitoring science [

7,

14]. GEE consists of several key components that make it an impressive tool for geospatial analysis [

26,

27,

28]. These key components include: 1) Its Data Catalog, which offers free access to a wide range of remotely sensed data and geospatial datasets [

29]. 2) Its Code Editor, is a web-based interactive environment that allows users to implement and execute JavaScript code in order to process and visualize data [

30,

31]. 3) Its cloud-based processing, which leverages Google’s high-performance computing infrastructure and parallel processing capabilities to enable efficient large-scale analysis without requiring local storage [

12,

32]. 4) allowing Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) in JavaScript and Python, which support workflow automation, integrate with other platforms, and enable the development of customized applications [

33,

34]. 5) GEE’s built-in export and sharing tools allow users to share results through Google Drive, Cloud Storage, or Earth Engine assets, facilitating collaboration and reproducibility [

12,

14]. 6) supports user-defined processing methods, enabling users to develop algorithms and deploy interactive applications using its accessible resources [

13,

20]; and 7) its software-free accessibility enables users to process datasets without downloading data or installing additional software, while still supporting integration with external packages and private datasets when needed [

7,

12,

14]

Moreover, GEE offers a comprehensive cloud-based solution for processing remotely sensed data, integrating both data access and analytical tools, making traditional desktop-based image analysis obsolete [

34,

35]. GEE is providing the researchers with a high-capability platform to analyze massive amounts of remotely sensed data through parallel processing techniques. This infrastructure facilitates efficient large-scale geospatial data analysis and ensures the timely delivery of results, even when working with highly complex datasets [

12,

32]. These features make GEE an effective tool for environmental monitoring, disaster response, and geospatial research.

Additionally, this platform includes a range of built-in algorithms, such as classification algorithms like Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Classification and Regression Tree (CART), and other supervised classification methods [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Moreover, it also involves various clustering algorithms such as K-Means, Cobweb, and Simple Non-Iterative Clustering (SNIC) [

10,

11,

44].

Research indicates that GEE has been utilized across various research fields, including urban planning, water management, health, forestry, and agricultural research [

14,

45,

46,

47,

48]. The majority of studies using GEE have concentrated on the evaluation and monitoring of land use and land cover (LULC) changes, among trend historical evaluation, the role of land surface temperature (LST) in global warming, and water resources studies [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

2. Significance and Objective

Due to the continuous increase in urbanization, monitoring LULC change has become crucial for evaluating urban planning, understanding urban-related hazards arising from rapid expansion, and mitigating the consequences of human–environment interactions [

57,

58]. Assessing LULC dynamics is also essential for evaluating impacts on ecosystems, including deforestation and biodiversity loss [

16]. More broadly, LULC analysis plays a key role in monitoring changes on Earth’s surface, encompassing climatic, environmental, and human transformations. However, LULC data supports evidence-based policy-making and economic planning [

18,

56].

Given these critical roles, this review focuses on the role of GEE in analyzing and monitoring LULC change. To the best of our knowledge, although several review papers address either GEE or LULC independently, no review has specifically examined LULC studies conducted using GEE. Therefore, this study aims to fill that gap by providing a comprehensive and up-to-date review of how GEE is applied to LULC change detection, identifying current trends, methodological preferences, and practical challenges. The study provides a foundation for researchers selecting methodologies and datasets for LULC analysis using GEE. The following section will provide a thorough evaluation and analysis of recent review papers, focusing on the role of GEE in remote sensing research.

3. Summary of Recent Review Articles

According to [

12], five literature review studies on GEE were conducted up to 2020, including articles by [

11,

14,

25,

47], and [

12] itself. Based on our investigation, six additional review articles have been published since 2020, including [

7,

10,

13,

15,

20,

59]. The studies reflect a remarkable increase in the utilization of GEE and its applications across various scientific disciplines. For instance, [

11] illustrated a comprehensive review of the GEE platform, discussing its data catalog, system architecture, and efficiency, and offering insights into its broad range of applications. In other studies [

25,

47] explored the usage patterns of GEE, revealing that most GEE-related research comes from developed nations, with Landsat being the dominant dataset. These studies also identified a gap in research from less developed countries, particularly in regions such as Africa. In terms of applications, the studies revealed that GEE has been widely used in several scientific fields, including monitoring and tracking land use and land cover (LULC) changes, land cover classification, disaster management, and agricultural research studies. These studies highlighted the strength of GEE as an emerging open-source tool across various applications. They also indicated that the demand for GEE is expected to grow significantly in the future due to its high capabilities in providing diverse data and its efficiency in analyzing and managing geospatial data in a manner suitable for users worldwide.

More recent review studies have confirmed what earlier reviews, before 2020, already indicated, showing an apparent increase in the use of GEE. For example, [

12,

13,

14] demonstrated the rapid expansion of employing GEE in a wide range of research and applications. These studies prove that Landsat datasets remain the most popularly utilized data, and machine learning techniques such as Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) are frequently employed for classification tasks. Additionally, GEE's role in investigating and analyzing global issues, such as water resource management, deforestation, desertification, air pollution, and global warming, was clearly highlighted in these reviews. In the context of GEE, ML, and AI integration, [

15,

59] identified the role of GEE in geospatial research, with a focus on ML and AI tools. The studies investigated technical aspects and the most utilized techniques and methodologies. The authors noted key challenges and future research priorities, while [

7,

20] underscored the platform's capabilities across several disciplines, reporting that countries such as China and the USA are major contributors to its widespread adoption. A summary of the main scope and findings of these review papers is described in

Table 2. In general terms, most review studies before 2020 highlighted the robust capabilities and components of GEE, as well as its applications in various research fields, predicting high demand for this technology due to its free access and ability to support remote sensing studies, with a note on the low contribution from less-developed countries. At the same time, more recent reviews (2020 onward) have focused on improving GEE effectiveness through integration with ML, DL, and AI approaches, which enhance performance and provide more reliable and accurate results.

However, GEE continues to prove itself as an effective tool for processing massive amounts of geospatial data and tackling global challenges, despite some obstacles and regional disparities in its adoption.

4. Materials and Methods

The first step of this research was to identify the range of selected articles, focusing on publications that utilized the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform to analyze and monitor Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) changes. The selection criteria focused on utilizing multiple global scientific libraries and databases to ensure the inclusion of the most relevant studies aligned within the scope of our research and to minimize selection bias. The review and analysis were conducted through “Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science” libraries and databases to identify the most relevant articles. The selection criteria included: the exclusive presence of the terms “Google Earth Engine” and “Land Use and Land Cover” in the title or keywords; publication in English; publication in peer-reviewed and high-impact journals; and a focus on the most recent year.

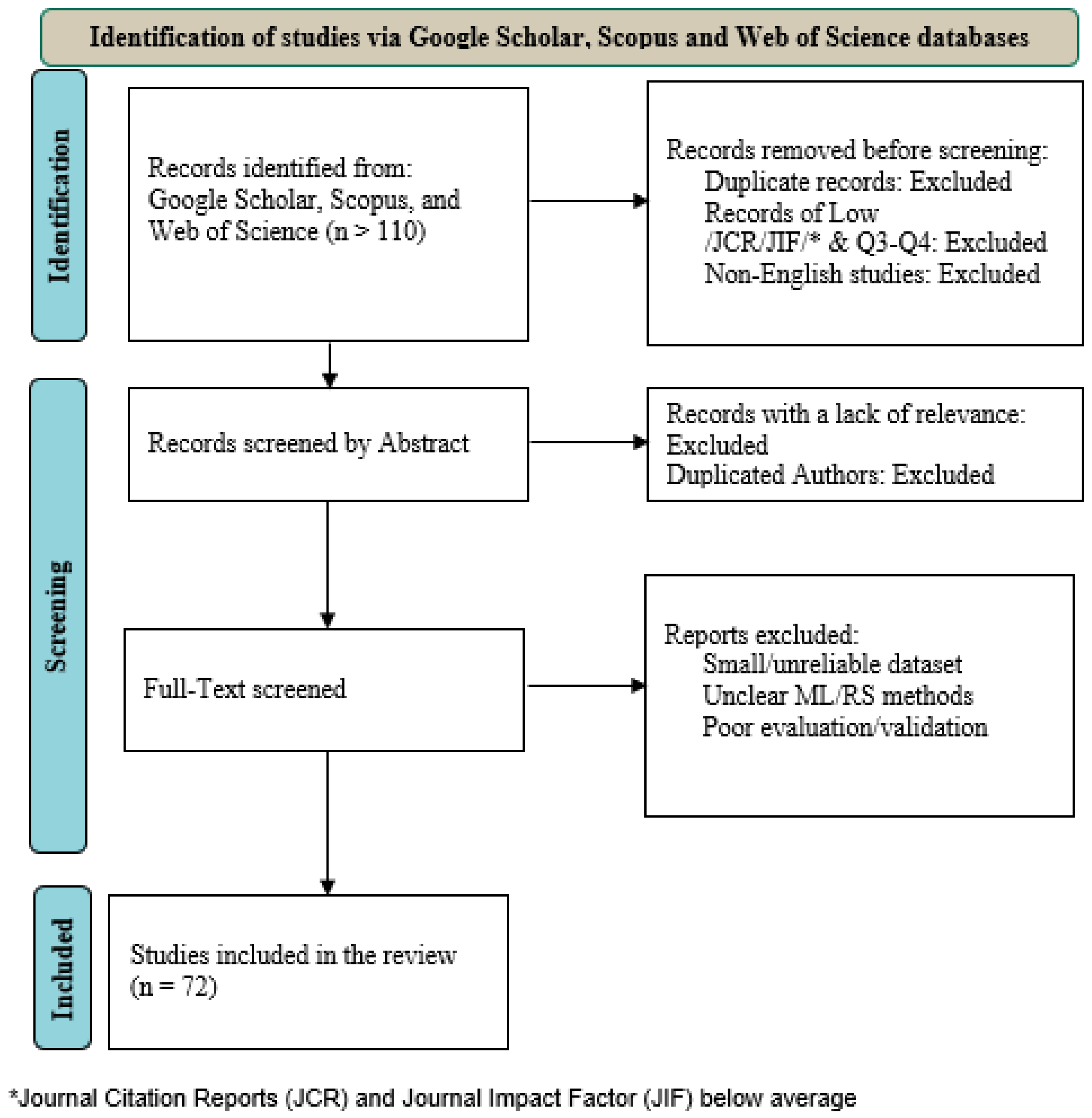

Consequently, more than 110 articles were reviewed. Then, some articles that were less relevant or had similar content, authors, or were published in a non-English language or low-impact journals were excluded. Finally, 72 articles were selected, including 11 review articles on GEE and about 61 articles on the use of GEE in LULC-related topics for in-depth analysis. These selected articles represent a comprehensive and significant body of work in the field of GEE-based LULC research. All selected articles in the database were thoroughly reviewed, and various pieces of information were collected. The articles database includes details such as the paper’s title, authors' names, keywords, publication year, journal, study areas, study sizes, satellite data, LULC classification method, data resolution, study period, accuracy, and reported challenges of using GEE. The PRISMA workflow has been used to ensure a transparent and systematic process for selecting studies.

Figure 1 illustrates the process of choosing and screening studies included in this review.

5. Results

5.1. Time Trend Analysis of Search Engine Results on GEE and LULC-Related Publications

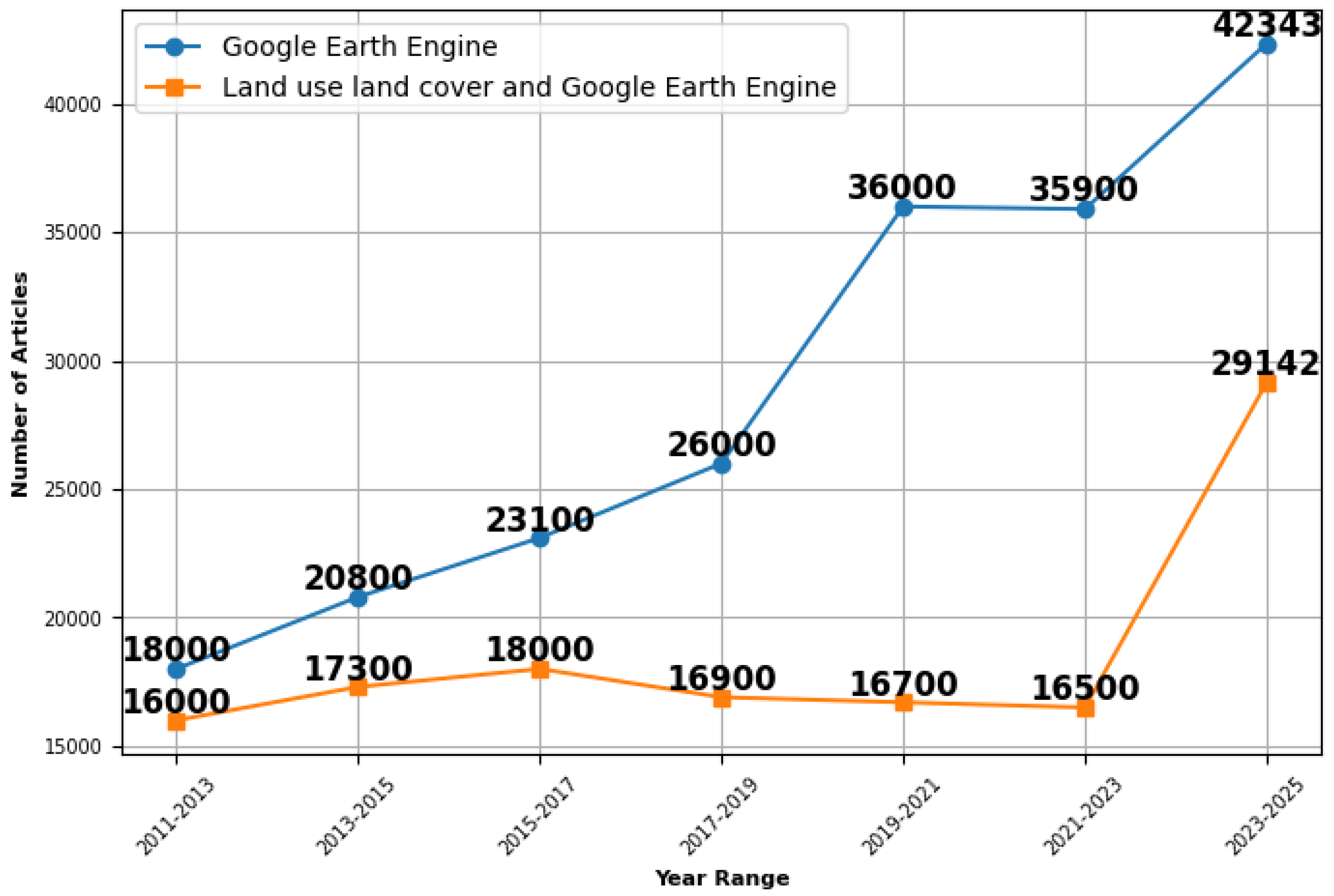

The analysis of the observed results, conducted through “Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science” search engines using the term "Google Earth Engine (GEE)" from 2011 to 2025, reveals that GEE experienced exponential growth from 2011 to 2021, followed by a period of stabilization between 2021 and 2023. This confirms the findings of the recent literature review article by [

13], which reported that GEE-related publications have grown significantly, with nearly 85% of them published in the past three years. Overall, based on our findings, the number of research articles referencing GEE in identifying publication years in the “Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science” search engines has increased significantly over the years. A rapid growth was observed between 2015 and 2021. Between 2015 and 2017, the number of results reached about 23,100, indicating moderate growth. This increased to 26,000 results from 2017 to 2019, showing wider adoption of GEE. There was a significant jump to 36,000 results from 2019 to 2021, reflecting high demand for the use of GEE for research purposes during this period. From 2021 to 2023, approximately 35,900 results were recorded, indicating sustained research interest. Finally, in recent years, from 2023 to the present (up to February 2025), a notable increase in publications has been observed. This surge is attributed to the fact that the number of articles collected up to February 2025 indicates an estimated 42,343 results by the end of 2025.

Regarding the number of articles that utilized GEE in LULC-related research, there were fluctuations over the years. Growth was observed in earlier years (2013-2017), which can be attributed to the increasing popularity and accessibility of GEE. This was followed by a slight slowdown in the later years (2017-2023), possibly due to the field's maturation, the need for more complex and time-consuming research, and the recession that accompanied the global pandemic COVID-19. However, a significant increase in publications integrating GEE and LULC was noted in recent years (2023-2025), marking a notable rise. This surge could be due to recent developments in the GEE, new research applications, an increased focus on urban expansion-related topics, and LULC monitoring using remote sensing data.

Figure 2 illustrates the timeline of research trends observed through scientific search databases “Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science” that focused on GEE alone compared to studies that combined GEE and LULC-related studies between 2011 and 2025.

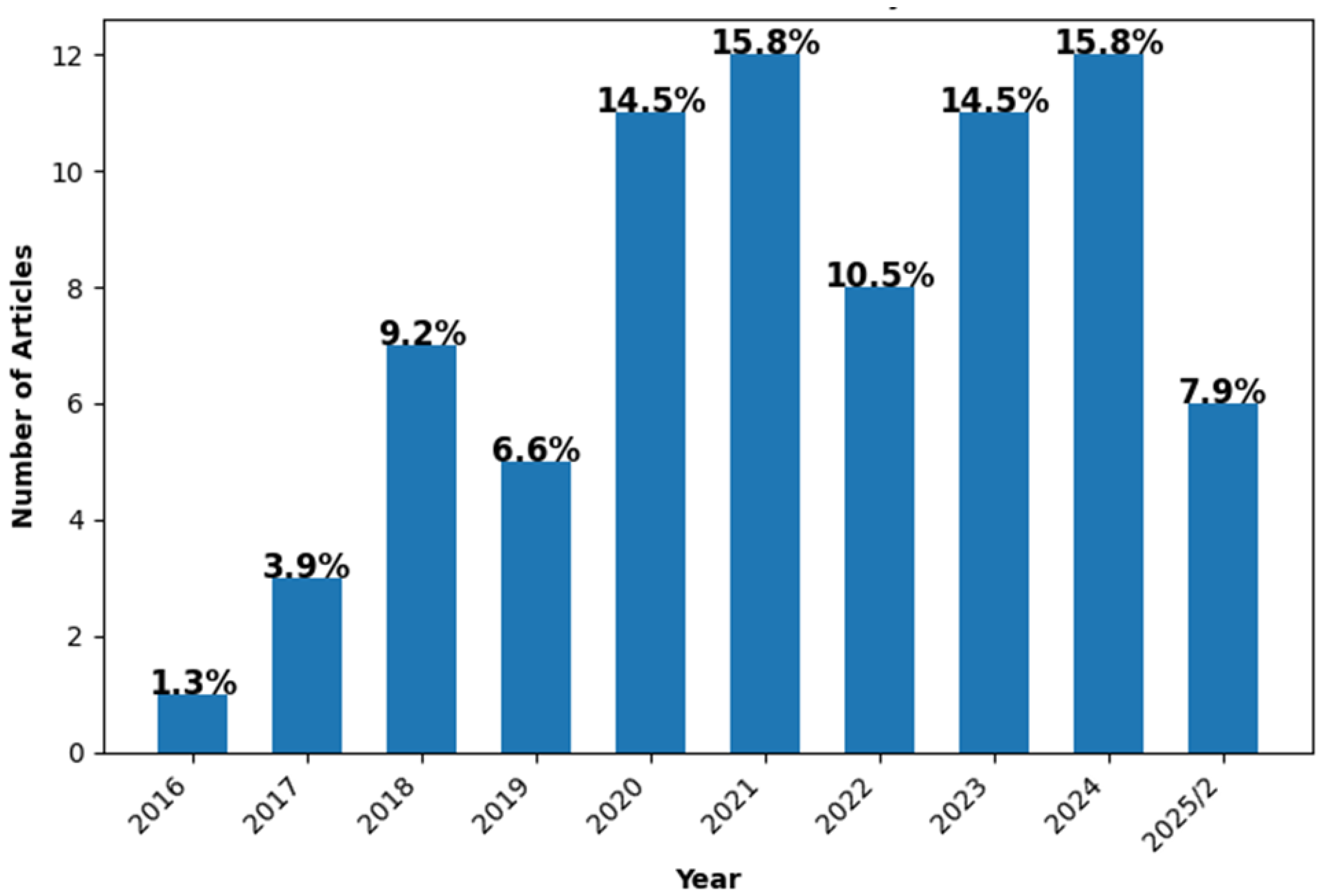

In this study, as shown in

Figure 3, all selected and reviewed articles (72 papers) were published from 2016 onward. About 80% of the articles were published after 2020, indicating a significant increase in research activity focused on GEE and LULC integration in recent years. Notably, 7.9% of the articles are from 2025, despite the data only covering the first two months of the year (up to February). This surge in publications in recent years reflects the growing interest and research activity in the field of GEE-based LULC research, keeping the audience updated with the latest trends.

5.2. Journals Analysis

During this study, the scientific journals that have published the selected papers were analyzed, showing a clear concentration of publications in specific journals. The journal “Remote Sensing” was utilized as a publisher for 25% of total publications, indicating its significant contribution in the field of remote sensing and environmental sciences. It is one of the most prominent and widely used journals in the discipline, likely to publish an extensive portion of the research related to satellite imagery, geospatial data, and remote sensing techniques. In addition, this confirms the results of previous review articles on GEE topics by [

10,

12,

13,

47], which revealed that the “Remote Sensing” journal has the highest number of publications in related fields. As a result, “Remote Sensing” has emerged as the leading journal for GEE-related publications to date. Several journals, such as “ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing”, “ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information”, and “Remote Sensing of Environment” appear multiple times, which may indicate a strong presence in their respective fields as shown in

Table 3.

Other journals in the list cover a variety of specializations within remote sensing, environmental monitoring, and geospatial sciences. For example, journals like “Land”, “Rangeland Ecology & Management”, “Water”, and “Sustainability” highlight the intersection of remote sensing with environmental science, land management, and sustainable development. The list includes not only journals focused on remote sensing but also interdisciplinary journals such as “Computers, Environment and Urban Systems”, “Journal of Earth System Science”, and “GIScience & Remote Sensing”, which cover broader geographical, environmental, and earth monitoring topics.

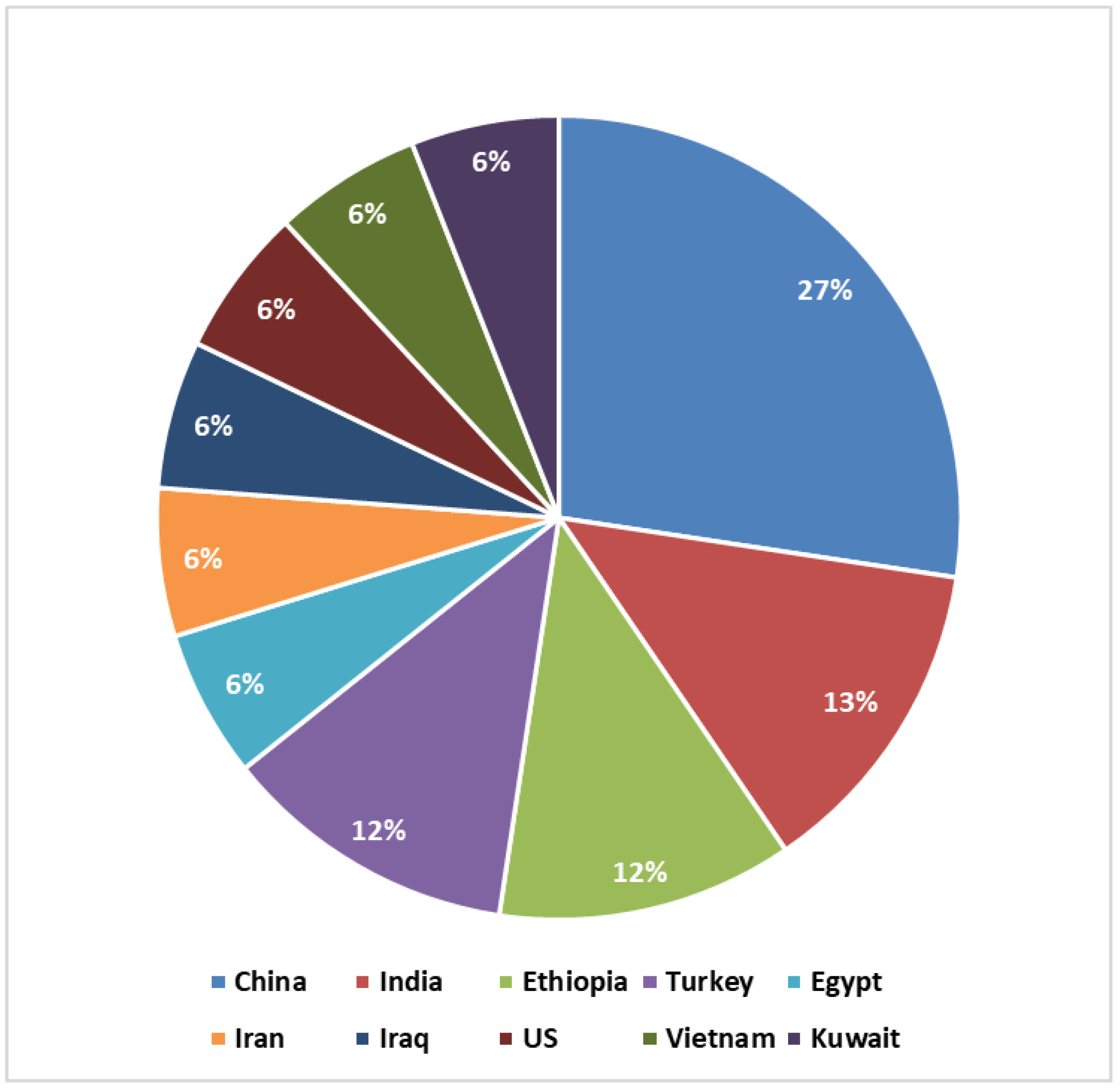

5.3. Geographical Distribution of Studies

One of the primary outcomes of this study is to highlight the geographical distribution of the reviewed papers. As shown in

Figure 4, the studies encompass a diverse range of regions worldwide, including China, India, Ethiopia, Turkey, the US, and Vietnam, among other countries. China appears most frequently in the studies in about 27%, with studies covering various provinces, river basins, urban areas, and more (e.g., “Yangtze River Basin, Yellow River Basin, Shenzhen, Shandong, Hebei, and Liaoning”). after China, India often appears in several studies, accounting for 13%, focusing on districts, sub-basins, and specific regions. (e.g., “Jagatsinghpur district, Kolleru Lake and Munneru Sub-Basin”).

The period from 2020 to 2024 witnessed a rise in global-level studies such as [

4,

8,

30,

34,

60], as well as several regional-level studies such as [

16,

19,

24,

28,

61,

62,

63]. This reflects a high-growing interest globally and regionally in using remote sensing virtual platforms, particularly GEE, for analyzing and monitoring large-scale data in urbanization and environmental studies. In early 2025, several studies such as [

5,

51,

54,

57,

58] highlighted a significant focus on utilizing GEE for analyzing and investigating urban sprawl and wetlands, indicating a future research direction towards addressing the impacts of urbanization and environmental change.

By analyzing studies covering extensive regions such as China’s Yellow River Basin (967,000 km²) in the study [

64] and Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta (7306.6 km²) in the paper by [

16], it is evident that researchers rely on GEE as a primary tool and data source for widespread study areas. These regions are of particular interest due to their ecological and socio-economic significance, making the use of GEE in these studies particularly noteworthy. Based on this extensive reliance on GEE in these studies, GEE has proven to be a reliable and effective platform for managing and analyzing large-scale remotely sensed data. There are other studies focused on smaller but significant areas, such as Indonesia’s Banda Aceh (small urban areas) authored by [

42], Italy’s Calabria by [

27], and Ethiopia's Upper Tekeze River Basin’s studies by [

33,

65], demonstrating that GEE provides a diverse range of datasets for researchers to conduct their studies smoothly and achieve the desired results.

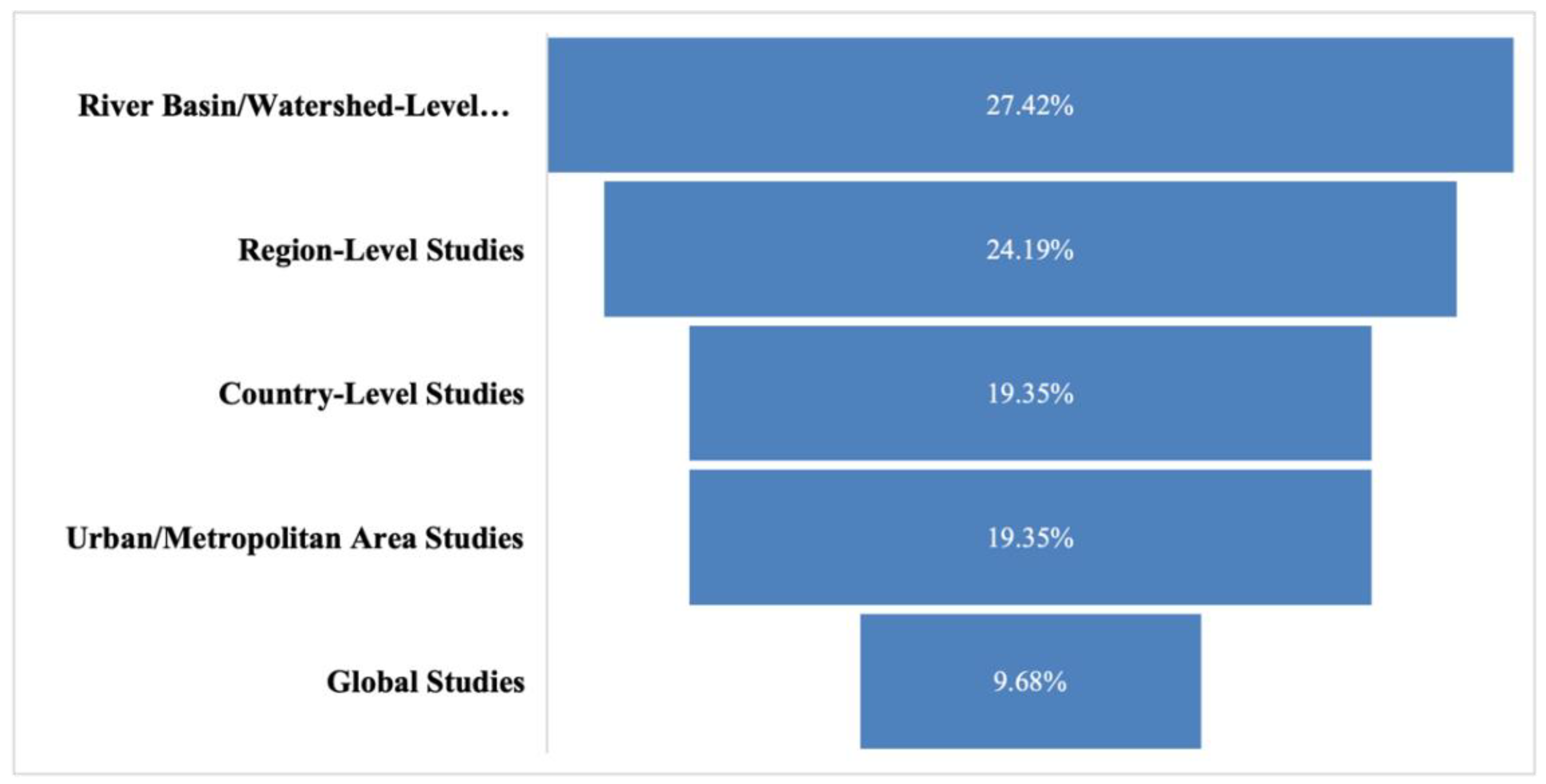

According to the reviewed papers, the analysis and assessment of LULC change were consistently dominant in all geographical scales, as illustrated in

Figure 5, reflecting the powerful capabilities of the GEE platform on different scales.

This also emphasizes the importance of GEE in land management, urbanization, and agriculture monitoring-related studies. In particular, the studies have focused notably on urban expansion and LULC analysis in recent years (2023–2025) across various spatial scales. This concentration was clear in several articles, such as [

1,

5,

21,

28,

40,

48,

58]. This trend highlights an increasing need for effective open-source platforms, such as GEE. As the demand for advanced analytics and global engagement in LULC studies continues to grow, it is anticipated that the adoption of platforms like GEE will become more urgent, ensuring that researchers can keep pace with the evolving landscape of geospatial analysis.

5.4. LULC-Related Methods, Algorithms, and Applications

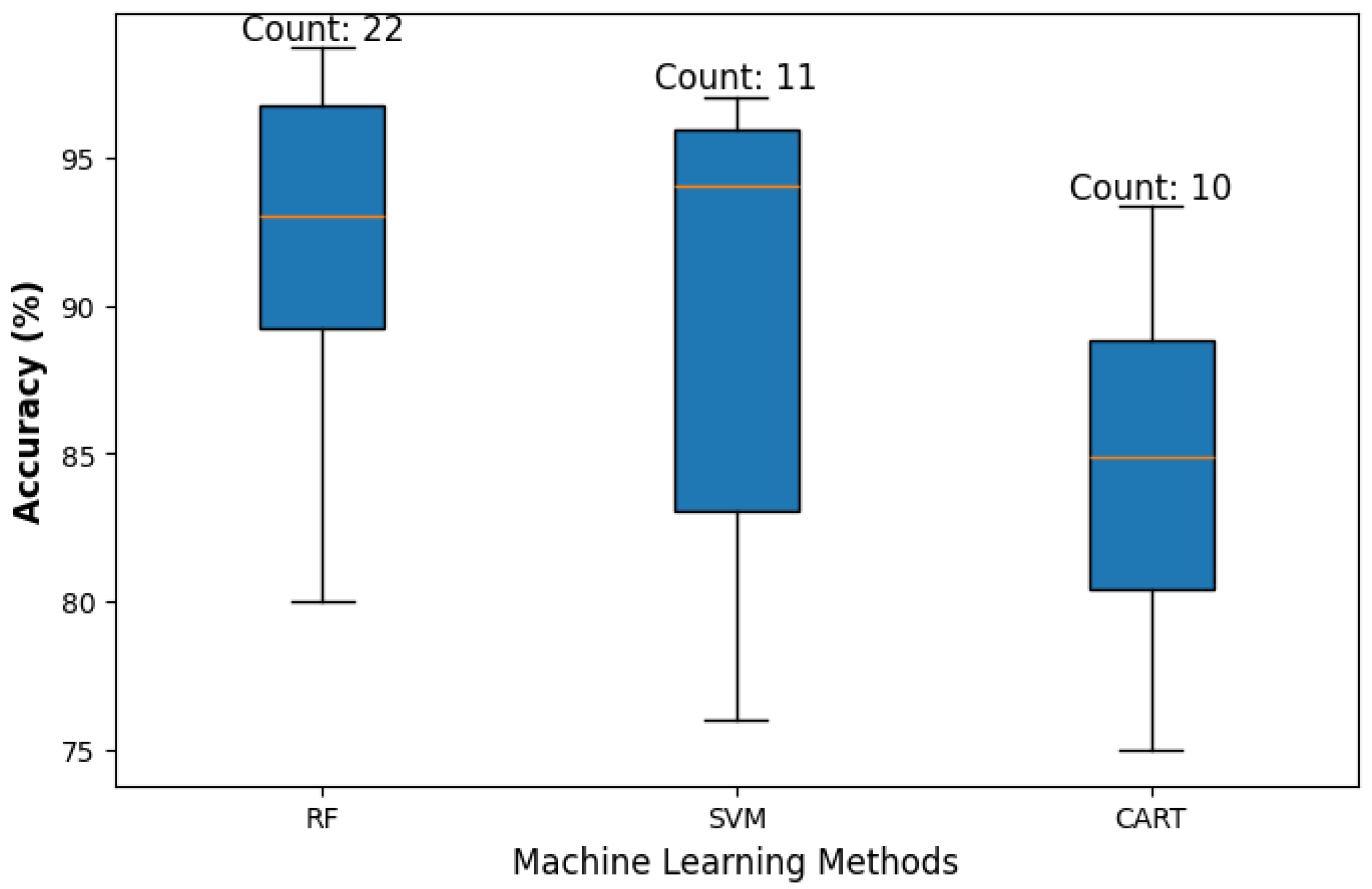

Various methods have been applied for LULC data classification in the selected studies. As shown in

Figure 6, the Random Forest (RF) algorithm was the most commonly used classification method, appearing in the majority of studies and representing approximately 36% of all reviewed studies. It was followed by Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Classification and Regression Trees (CART), which accounted for approximately 19% and 17%, respectively. Several Deep Learning (DL) approaches, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Fully Convolutional Neural Networks (FCNN), and TWIn Neural Networks for Sentinel data (TWINNS), were utilized in about 6.67% of cases, indicating that deep learning is emerging as a strong tool, particularly for Sentinel and Landsat imagery. Some less commonly used methods, such as Naive Bayes, Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST), Simple Non-Iterative Clustering (SNIC), and Random Under-sampling Ensemble of Support Vector Machines (RUESVMs), were each applied only once in the reviewed studies.

Most studies (almost 90%) validate classification results using overall accuracy, user’s accuracy, producer’s accuracy, and Kappa coefficient. The overall accuracy of different classification methods ranges from 80% to 98.68%, with most methods achieving above 90%. This high level of accuracy reassures researchers about the reliability of the results. At the same time, Kappa values are generally high and above (> 0.75), indicating strong agreement between classified results and reference data. The highest reported accuracy (98.68%) was achieved using a combination of RF, CART, and SVM. However, the RF classifier alone provides accuracy above 95% in most cases. The most frequently used algorithms for data analysis were RF, SVM, CART, and Maximum Likelihood (MLH), with RF being the most widely adopted method. SVM is commonly combined with RF, typically achieving accuracy above 90%. In contrast, CART, although widely used, generally provides lower accuracy, ranging between 80% and 90%, as demonstrated in

Figure 6.

The Maximum Likelihood Algorithm (MLH) was utilized in some studies, but it is less prevalent than machine learning methods. Moreover, deep learning and neural network models, including FCNN, TWINNS, and Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network (MLPNN), are gaining attention in LULC-related research due to their high accuracy.

For instance, RF is a highly adaptable algorithm and widely used across various domains, including LULC classification, urban growth modeling, regression analysis, time series analysis, and change detection. It is often combined with other machine learning algorithms such as SVM, CART, ANN, and Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) to enhance its performance and accuracy. SVM algorithms were frequently used in combination with RF and CART to improve results, particularly in tasks such as Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) intensity classification, urban expansion prediction, and change detection. It is widely applied in supervised classification tasks and is often combined with other algorithms to develop advanced change detection methods. The Maximum Likelihood Algorithm (MLH) serves as a baseline for comparison with more complex algorithms such as RF and SVM, particularly in supervised classification. It is also used in index-based methods, such as the Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI), which combines multiple indices, including the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI), the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), and the Normalized Difference Built-up Index (NDBI), for comprehensive land use and land cover analysis. CART was also commonly used in urban growth modeling, change detection, Land Surface Temperature (LST) analysis, and LULC classification. However, SVM and CART algorithms are often combined with other models to improve classification accuracy. Other algorithms, such as ANN, are leveraged for predicting future LULC projections and urban expansion. Moreover, Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) and Linear Spectral Mixture Analysis (LSMA) are also employed alongside RF and SVM to enhance the accuracy of the regression model, providing better results in complex geographical and urban studies.

5.5. Satellite Imagery Usage

This study has examined various data sources used for LULC classification and analysis in the selected papers. The results demonstrate consistency across the most common datasets, based on multiple approaches aligned with each study's primary objectives. This is especially noteworthy, given that some studies have used different types of remotely sensed data sources to achieve impactful results. Overall, as demonstrated in

Table 4 and

Figure 7, Landsat satellite data, including all versions, were utilized in 65% of LULC-related studies, confirming their dominance in long-term change detection and land use land cover (LULC) analysis. Landsat-8 is the most often used satellite sensor, appearing in 31% of total studies, underscoring its importance in remote sensing applications [

14]. Landsat-5 and Landsat-7 were utilized in 20% and 14% respectively, reflecting the continued reliance on historical Landsat data for long-term LULC change and environmental monitoring [

15]. This widespread use of Landsat data underscores its reliability and the trust researchers place in it for their studies. On the other hand, Sentinel satellite datasets, including Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2, were employed in 23% of the reviewed LULC-related articles, highlighting their essential role in remote sensing but still trailing behind Landsat in overall usage [

14,

66]. Precisely, Sentinel-2 has been used in 15% of papers, making it more widely adopted than Sentinel-1, which appears in 8% of the total studies. This indicates a stronger preference for researchers to use optical data over SAR-based observations [

10,

12]. MODIS data have been utilized in various LULC studies, representing 4.5% of the total studies. The low percentage of MODIS dataset utilization in LULC monitoring studies is likely due to its lower spatial resolution (250m, 500m, 1000m) [

47] compared to Landsat and Sentinel data. However, its effectiveness was remarkable in studies that required Near Real-Time (NRT) data due to its appropriate temporal resolution for monitoring and investigating environmental issues such as drought, vegetation health, natural disasters, and atmospheric studies [

10,

11,

12].

These trends highlight the significant role of Landsat data in environmental and urban studies, complemented by the integration of Sentinel data for a wide range of research applications. The use of Landsat and Sentinel satellite data with spatial resolutions ranging from 10m to 30m is crucial for monitoring land-use changes, urban sprawl, deforestation, and environmental degradation [

62,

66]. Based on our findings, the most common spatial resolution used in studies focusing on urban expansion monitoring and LULC change tracking was 10 to 30 meters, which provides an excellent balance between spatial detail and coverage. This balance ensures the effectiveness of the chosen approach in capturing both detailed and broad changes in the landscape.

5.6. Studies Periods

By reviewing the selected papers that used GEE for LULC change monitoring, we have identified an apparent variation in the time intervals of the studies, ranging from long-term analyses (approximately 30 years) to short-term periods (1 to 5 years), depending on the primary objectives of each study. Most studies have mainly focused on decadal trends in years such as 2000, 2010, and 2020, which are the most frequently analyzed years. Many studies follow fixed decadal intervals (e.g., every 5 or 10 years) such as [

23,

44,

67]. In contrast, others such as [

5,

52,

64] used variable intervals or annual data (e.g., 1987–2020) for time-series analysis. Short-term studies (e.g., 2016 to 2019, 2015 to 2020, 2019) examined recent changes, as seen in studies conducted by [

29,

60,

68], whereas long-term studies (e.g., 20–30 years) explored historical trends such as [

16,

51]. Landsat satellite datasets, particularly Landsat 5, 7, and 8, have been extensively used over long periods, such as 20-30 years, for research investigating environmental monitoring and LULC change detection [

14,

15]. MODIS data, on the other hand, has been employed in broader temporal ecological studies, particularly focusing on vegetation, water bodies, large-scale atmospheric analysis, and studies that require Near Real-Time (NRT) data [

11,

12]. Sentinel-1 (SAR) and Sentinel-2 (optical) data are commonly used in various recent studies, such as [

8,

44,

58], which concentrate on monitoring and investigating long-term and short-term urban dynamics and expansion. This reflected the effectiveness of their temporal and spatial resolution, which is ideal for detecting rapid changes, such as land subsidence and urban sprawl. The increased use of Sentinel data in recent years has highlighted a shift towards more detailed monitoring of land and infrastructure changes, especially in land-use and urban planning. The combination of utilizing various satellite data, such as Landsat and Sentinel, provides complementary insights, allowing for comprehensive analysis of large-scale and localized environmental issues and LULC change monitoring [

15].

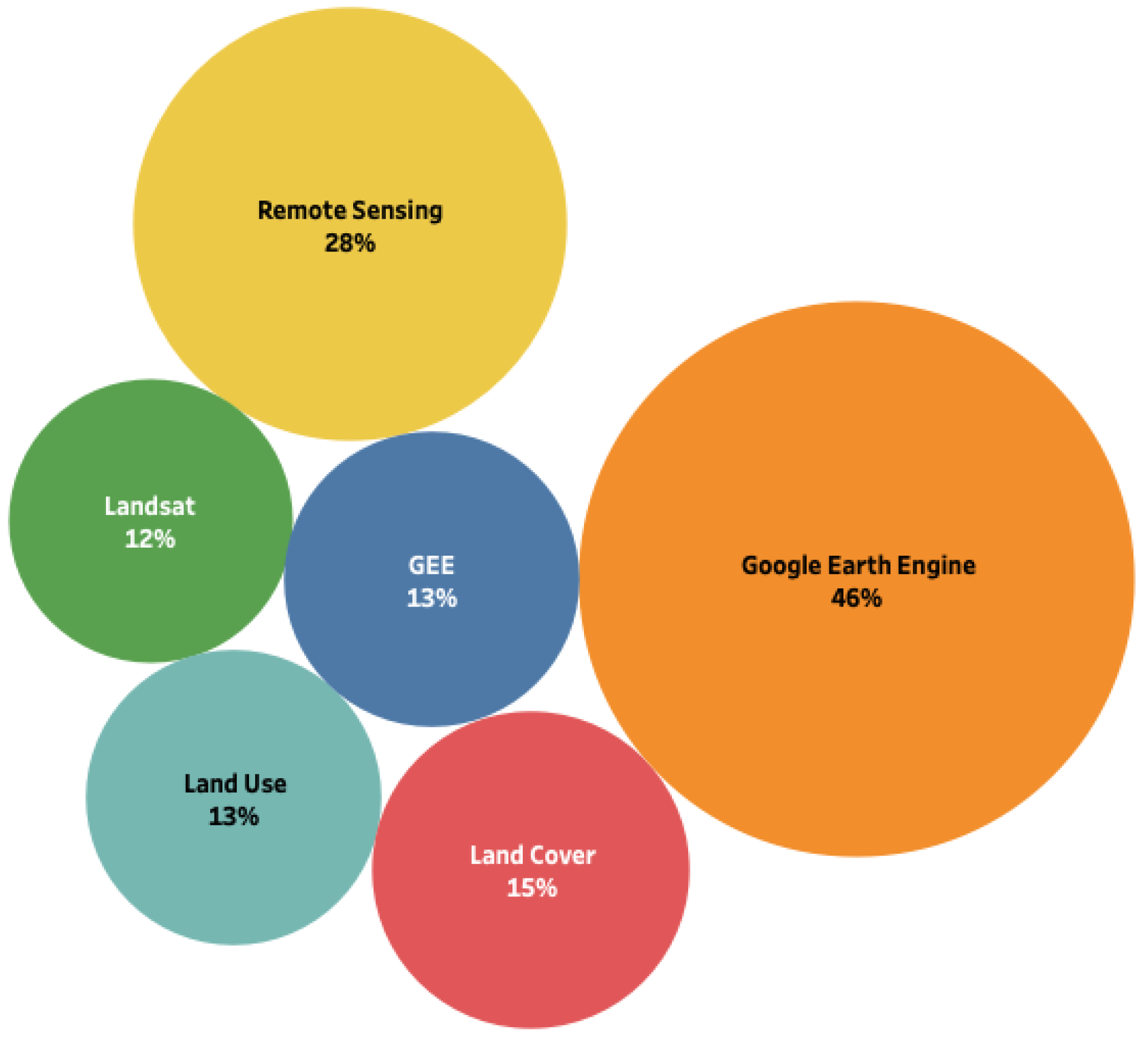

5.7. Keyword Analysis

Throughout this study, the replication of common keywords used in the reviewed articles was examined. The analysis of the frequency and percentage distribution of common keywords reveals that “Google Earth Engine” is the most frequently used term, occurring 33 times, which constitutes approximately 46% of the total studies. This indicates a strong focus on the usage of Google Earth Engine in the context of scientific remote sensing applications and studies. Other key terms include “Remote Sensing” (20 occurrences), “Land Cover” (10 occurrences), and the “GEE” shortcut (9 occurrences), highlighting the significant role of remote sensing technologies and GEE platforms in selecting the research’s keywords. The frequent use of these terms suggests a clear trend toward geospatial data-driven approaches and cloud-based processing in recent LULC research.

Table 5 and

Figure 8 present the top six most used keywords.

Terms related to “Change Detection”, “Machine Learning”, “Cloud Computing”, “Urban Expansion”, and “Change Detection” also appear frequently, highlighting their importance in geospatial analysis and environmental monitoring research. Additionally, the terms “Landsat”, “Sentinel”, and “LULC” are common keywords in the reviewed articles, which emphasize the significance of satellite imagery and LULC analysis.

Figure 9 illustrates a word cloud of the most frequently used keywords in the reviewed studies.

Overall, the main keywords chosen by researchers mainly have revolved around geospatial technologies, machine learning applications, and satellite-based monitoring. This highlights the growing role of GEE not just as a data platform, but as a vital tool and theme for modern geospatial analysis.

6. Discussion

This discussion articulates key insights from this study and recent review papers on Google Earth Engine, situating them within the broader context of the platform's expanding applications, evolving methodologies, global usage trends, and challenges. By comparing earlier reviews [

12,

25,

47] with more recent reviews, such as [

10,

13,

20] this study highlights critical shifts in GEE’s role within remote sensing research from its early stages to its current status as a globally utilized platform.

6.1. Expansion of Data Usage and Methodological Shifts

Early reviews, such as [

12], revealed the dominance of Landsat and Sentinel data in GEE applications, with RF algorithms being widely implemented. Subsequent studies, including [

14,

20] confirmed these trends while noting an increasing reliance on Sentinel-2 due to its improved spatial and temporal resolution. Our review further demonstrates a methodological evolution, with a growing emphasis on deep learning, cloud-native workflows, and AI-driven automation [

15]. This shift reflects GEE’s transition from being primarily a data access tool to a comprehensive platform supporting advanced large-scale analytics. [

25,

47].

6.2. Geographic and Thematic Diversification

Initial assessments by [

25,

47], highlighted GEE’s limited adoption in developing regions, despite its potential to make geospatial analysis more accessible. However, later studies, including [

14,

20] observed a significant increase in contributions from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, with countries such as China, India, Ethiopia, and Brazil emerging as key contributors. Our findings support this trend, showing broader engagement from previously underrepresented regions, particularly in applications such as urban expansion, wetland monitoring, and agricultural assessments. This expansion aligns with [

11] the original vision of GEE, which is to be an inclusive and globally accessible platform.

6.3. Increasing Specialization and Interdisciplinary Applications

While early review by [

12] emphasized GEE’s general utility in LULC mapping and environmental monitoring, more recent analyses reveal a trend toward specialization. Studies such as [

59] focused on refining classification techniques using machine learning, while [

10,

13] highlighted GEE’s growing role in climate change, disaster response, and public health. The integration of AI and cloud computing [

15] has further enabled complex, large-scale analyses, reinforcing GEE’s position as a cornerstone of modern geospatial research. Our study aligns with these findings and confirms that the GEE platform has become a powerful integrated tool for obtaining data, conducting comprehensive analysis, and visualizing the desired results. Furthermore, the platform is developed to be integrated with advanced ML and AI tools, serving researchers worldwide across various fields of research.

6.4. Comparative Insights on GEE’s Future Directions

Compared to foundational work such as [

11] which positioned GEE as a revolutionary and promising tool, recent reviews demonstrate its evolution into a standardized platform for remote sensing and geospatial research. The rising number of publications, diversification of applications, and global user base underscore its established role not only in addressing environmental and societal challenges but also in contributing its extensive capabilities to a wide range of studies worldwide.

6.5. Reported Limitations of GEE in LULC

GEE is a powerful tool for processing geospatial data, but it has some limitations that obstruct its full potential for various applications [

7,

11,

12,

14]. Noting that these limitations could be considered as expected challenges in the technology fields. These challenges could be addressed in the future without compromising the high effectiveness and performance of the GEE platform. One of the major challenges is the difficulty in handling large datasets due to memory constraints, which can result in slow processing times, especially when dealing with high-resolution or large-scale time-series data [

14,

15]. Moreover, GEE's fixed computing infrastructure limits users' ability to adjust computational resources, while the flexibility is often needed for more detailed computations and simulations [

15,

58]. Additionally, GEE’s users highlighted some challenges with cloud cover and data gaps in satellite imagery, which can significantly reduce its usefulness in areas with frequent cloud cover, such as tropical regions [

12,

14,

15,

64]. Users also face challenges when trying to integrate multi-source data and conduct spatial and temporal analyses together [

58,

69]. The platform’s lack of control over data chunking and limitations in multi-user collaboration further complicate large-scale and multi-user projects [

14,

61]. There are also significant issues with the limited set of algorithms available within GEE. For instance, machine learning tools are limited, and many deep learning models cannot be directly implemented on the platform [

7,

12,

14]. The platform is also not compatible with certain types of data, such as complex Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data (unless Sentinel-1 data), and high-resolution data (unless National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) and Planet Skysat) data [

7,

14]. In addition, GEE's data privacy has been mentioned in the literature as a marked concern, due to the storage of data on private company servers, which presents a barrier for users, governmental agencies, and private companies that require strict data confidentiality [

7,

12]. Users also reported some difficulties with specific preprocessing methods, such as atmospheric corrections and the platform's inability to handle complex segmentation algorithms [

7,

12].

To summarize, the most significant limitations are memory constraints and cloud cover interference, which hinder large-scale and tropical applications, respectively. Furthermore, other technical limitations, such as limited support for advanced machine learning (ML) models and fixed computing infrastructure, could be improved by integrating GEE with Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) in JavaScript and Python, which enable workflow automation and modeling. These limitations together highlight the challenges noted by users when using GEE for large-scale geospatial analysis.

Table 6 provides the main reported limitations and challenges of the GEE platform.

7. Conclusions

This review and analysis were conducted using the “Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science” search engines, covering 72 articles on GEE and its application in LULC research up to February 2025. The review reveals that Google Earth Engine (GEE) has become a valuable and effective tool for acquiring and analyzing remotely sensed data globally, with applications spanning multiple disciplines. This study has also shown how GEE has developed different aspects of analyzing and handling geospatial data by integrating ML and DL models. It is expected to increase the reliability of the GEE platform in the future due to its ease of access, quantity, and diversity of data it provides, and the combined analytical tools and models. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

GEE-related research has significantly increased over the years, as demonstrated by the recorded results through the search engines “Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science”, with rapid growth observed between 2015 and 2021. The number of publications grew from 23,100 (2015–2017) to 26,000 (2017–2019), followed by a sharp growth to 36,000 (2019–2021). Research interest remained stable from 2021 to 2023, with 35,900 results found. However, this stabilization is likely due to the recession during the COVID-19 pandemic. The latest data (up to February 2025) indicate a peak with an estimated 42,343 results by the end of 2025. Overall, GEE research witnessed exponential growth between 2015 and 2021, followed by stabilization between 2021 and 2023.

The journal “Remote Sensing” leads the contribution of GEE-LULC research, noticeable in 25% of total studies and highlighting its significance in LULC-related topics using GEE. Other prominent journals, including “ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing”, “ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information”, “IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing”, and “Remote Sensing of Environment”, also have a strong contribution in the field of GEE and LULC-related research.

The reviewed articles cover multiple countries. China has the most frequent case studies, accounting for 27% of the total reviewed papers, followed by India (13%), and other countries such as Ethiopia, Turkey, and the US.

RF was the most utilized classification method (36%), followed by SVM (19%) and CART (17%). SVM is often combined with RF, achieving an accuracy of over 90%, whereas CART typically ranges from 80% to 90%. Deep learning approaches, including ANN, FCNN, and TWINNS, account for up to 6.67% of appearances in the selected studies, indicating a growing adoption, especially for Sentinel and Landsat imagery.

Most studies validate classification results using overall accuracy ranging from 80% to 98.68%. The highest accuracy was achieved by combining the RF, CART, and SVM algorithms.

Landsat satellite imagery with 30m spatial resolution has dominated over remote sensing studies, appearing in 65% of case studies, with Landsat-8 being the most used (31%). Sentinel-2 data were utilized in approximately 15% of studies, and they were more widely adopted than Sentinel-1 (8%). This has reflected the preference by researchers to utilize optical data over SAR data. Combined Sentinel satellite data appeared in 23% of studies, showing growing usage but still trailing behind Landsat. MODIS data was used in 4.5% of cases, likely due to its coarse spatial resolution. These trends underscore Landsat's pivotal role in land use and land cover monitoring studies, as well as the growing integration of Sentinel data. This apparent demand for Landsat data was due to the availability of massive archived historical data provided by Landsat satellite missions since 1972, which was suitable for researchers to track and monitor historical changes over extended periods [

14,

20,

47].

GEE-based LULC studies mainly focus on decadal trends, with key years being 2000, 2010, and 2020. Fixed, variable, and annual intervals are used in time-series analysis, with a growing emphasis on data from the post-2015 period. Landsat (5, 7, 8) data sets were extensively utilized for long-term monitoring, while MODIS offers global environmental insights. Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 are increasingly adopted for high-resolution and rapid change detection-related studies, particularly in monitoring environmental issues, urban, and land-use planning.

The analysis shows the term "Google Earth Engine" as the most frequent keyword observed in 46% of occurrences in the reviewed studies, followed by "Remote Sensing" and "Land Cover". Other notable terms, including "Change Detection", "Machine Learning", and "Cloud Computing", have been noticed, highlighting their importance and repetition in remote sensing-related studies.

The main challenges in using Google Earth Engine for geospatial analysis involved data processing, computational, analytical, integration, and security issues. Data-related obstacles, such as cloud cover, data gaps, and spatial resolution limitations, can affect the accuracy of results and obstruct the detection of small-scale features. Computational constraints, particularly memory limits, fixed platform resources, and long processing times for large datasets, remain concerns for users. Furthermore, the identified analytical challenges include pixel-oriented noise in classification, limited training samples, and difficulties in spatiotemporal analysis. The restricted availability of advanced data mining models and the integration of deep learning further complicate the analysis. Additionally, GEE faces some limitations in the integration process that assist with multi-user collaboration and multi-source data interoperability. Security and privacy concerns arise from data being stored on private servers, which can deter governmental and private organizations from using the platform. Despite these challenges, Google Earth Engine has proven to be an effective and valuable tool for researchers in various fields, including LULC change tracking, disaster management, hydrological studies, monitoring land surface temperature, and forecasting future urban expansion.

Looking ahead, identifying these challenges can help to suggest key solutions that GEE’s operators could implement. Specifically, integrating deep learning architectures, boosting Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) support, and expanding native libraries for AI models can significantly enhance GEE’s analytical capabilities. Furthermore, trends such as real-time environmental monitoring, enhanced support for multi-sensor fusion, and the growing adoption of cloud-native geospatial AI are expected to further increase GEE's utility. As geospatial research increasingly overlaps with artificial intelligence and big data, platforms like GEE are likely to evolve into more scalable, interactive, and intelligent systems for global environmental monitoring. This technology is expected to continue growing and developing significantly in the future.

This study advances the existing literature on GEE by offering a focused review of its applications in LULC-related research. Unlike more general bibliometric or platform-wide reviews, our study highlights methodological choices, algorithm preferences, and dataset use specific to LULC research. By analyzing trends in classification techniques, satellite data sources, and regional contributions, we underscore both the strengths and gaps in GEE-based LULC research. The study offers future insights and a foundation for researchers and practical applications, providing guidance on methodologies and datasets for LULC analysis using GEE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and Z.Z.; methodology, B.A. and Z.Z.; data collection and analysis, B.A. and X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.; review and refinement, Z.Z. and X.L.; editing, B.A.; supervision, Z.Z. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GEE |

Google Earth Engine |

| LULC |

Land Use and Land Cover |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| CART |

Classification and Regression Tree |

| MODIS |

Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NOAA |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| ALOS |

Advanced Land Observing Satellite |

| AWS |

Amazon Web Services |

| APIs |

Application Programming Interfaces |

| LST |

Land Surface Temperature |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Networks |

| FCNN |

Fully Convolutional Neural Networks |

| TWINNS |

TWIn Neural Networks for Sentinel data |

| InVEST |

Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs |

| SNIC |

Simple Non-Iterative Clustering |

| RUESVMs |

Random Under-sampling Ensemble of Support Vector Machines |

| MLH |

Maximum Likelihood Algorithm |

| MLPNN |

Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network |

| MLR |

Multiple Linear Regression |

| SAR |

Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| NUACI |

Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index |

| NDWI |

Normalized Difference Water Index |

| NDVI |

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDBI |

Normalized Difference Built-up Index |

| GWR |

Geographically Weighted Regression |

| LSMA |

Linear Spectral Mixture Analysis |

| NRT |

Near Real-Time |

| NAIP |

National Agriculture Imagery Program |

| GPU |

Graphics Processing Unit |

References

- Bathe, K.D.; Patil, N.S. Assessment of Land Use-Land Cover Dynamics and Its Future Projection through Google Earth Engine, Machine Learning and QGIS-MOLUSCE: A Case Study in Jagatsinghpur District, Odisha, India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 133, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Plaza, A.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Sun, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhu, Y. Big Data for Remote Sensing: Challenges and Opportunities. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulova, A.; Jokar Arsanjani, J. Exploratory Analysis of Driving Force of Wildfires in Australia: An Application of Machine Learning within Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Chakraborty, T.; Simensen, T.; Singh, G. Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Datasets: A Comparison of Dynamic World, World Cover and Esri Land Cover. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atesoglu, A.; Ozel, H.B.; Varol, T.; Cetin, M.; Baysal, B.U.; Bulut, F.S. Monitoring Land Cover/Use Conversions in Türkiye Wetlands Using Collect Earth. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Hao, Z.; Post, C.J.; Mikhailova, E.A.; Yu, K.; Yang, L.; Liu, J. Monitoring Land Cover Change on a Rapidly Urbanizing Island Using Google Earth Engine. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P. Progress and Trends in the Application of Google Earth and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.F.; Brumby, S.P.; Guzder-Williams, B.; Birch, T.; Hyde, S.B.; Mazzariello, J.; Czerwinski, W.; Pasquarella, V.J.; Haertel, R.; Ilyushchenko, S.; et al. Dynamic World, Near Real-Time Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Mapping. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Pei, F.; Wang, S. High-Resolution Multi-Temporal Mapping of Global Urban Land Using Landsat Images Based on the Google Earth Engine Platform. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cutillas, P.; Pérez-Navarro, A.; Conesa-García, C.; Zema, D.A.; Amado-Álvarez, J.P. What Is Going on within Google Earth Engine? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 29, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S.; et al. Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform for Remote Sensing Big Data Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham-Duc, B.; Nguyen, H.; Phan, H.; Tran-Anh, Q. Trends and Applications of Google Earth Engine in Remote Sensing and Earth Science Research: A Bibliometric Analysis Using Scopus Database. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 2355–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiminia, H.; Salehi, B.; Mahdianpari, M.; Quackenbush, L.; Adeli, S.; Brisco, B. Google Earth Engine for Geo-Big Data Applications: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 164, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Driscol, J.; Sarigai, S.; Wu, Q.; Chen, H.; Lippitt, C.D. Google Earth Engine and Artificial Intelligence (AI): A Comprehensive Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, N.A.; Nhut, H.S.; An, N.N.; Phuong, T.A.; Hanh, N.C.; Thao, G.T.P.; Pham, T.T.; Hong, P.V.; Ha, L.T.T.; Bui, D.T.; et al. Thirty-Year Dynamics of LULC at the Dong Thap Muoi Area, Southern Vietnam, Using Google Earth Engine. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hird, J.; DeLancey, E.; McDermid, G.; Kariyeva, J. Google Earth Engine, Open-Access Satellite Data, and Machine Learning in Support of Large-Area Probabilistic Wetland Mapping. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaefuna, R.O.; Chukwudi, D.O. Analysis Of Land Use And Land Cover Changes In Port Harcourt Metropolis Using Geospatial Techniques. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2024, 18, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix Justiniano, E.; Rodrigues Dos Santos Junior, E.; Malheiros De Melo, B.; Victor Nascimento Siqueira, J.; Gomes Morato, R.; Fantin, M.; Cesar Pedrassoli, J.; Roberto Martines, M.; Shinji Kawakubo, F. Proposal for an Index of Roads and Structures for the Mapping of Non-Vegetated Urban Surfaces Using OSM and Sentinel-2 Data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2022, 109, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velastegui-Montoya, A.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Rivera-Torres, H.; Sadeck, L.; Adami, M. Google Earth Engine: A Global Analysis and Future Trends. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dousari, A.E.; Mishra, A.; Singh, S. Land Use Land Cover Change Detection and Urban Sprawl Prediction for Kuwait Metropolitan Region, Using Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Networks (MLPNN). Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, R.; You, W.; Hanson, G.; Khandelwal, A. Detecting the Boundaries of Urban Areas in India: A Dataset for Pixel-Based Image Classification in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, M.; Cilek, A. ANALYSIS OF URBAN LAND USE CHANGE USING REMOTE SENSING AND DIFFERENT CHANGE DETECTION TECHNIQUES: THE CASE OF ANKARA PROVINCE. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-M-1–2023, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, C.; Song, Y.; Sun, W.; Yang, G. Long-Term Mapping of Land Use and Cover Changes Using Landsat Images on the Google Earth Engine Cloud Platform in Bay Area - A Case Study of Hangzhou Bay, China. Sustain. Horiz. 2023, 7, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Kumar, L. Google Earth Engine Applications. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Gao, X.; Shen, Z.; Li, R. Expansion of Urban Impervious Surfaces in Xining City Based on GEE and Landsat Time Series Data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 147097–147111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachoo, Y.H.; Cutugno, M.; Robustelli, U.; Pugliano, G. Impact of Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) Changes on Carbon Stocks and Economic Implications in Calabria Using Google Earth Engine (GEE). Sensors 2024, 24, 5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhu, R.; Qu, C.; Zhang, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, L.; Wang, F.; Huang, F. Spatio-Temporal Land-Use/Cover Change Dynamics Using Spatiotemporal Data Fusion Model and Google Earth Engine in Jilin Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, E.; Chandra, M.; Sunar, F. THE USE OF MULTI-TEMPORAL SENTINEL SATELLITESIN THE ANALYSIS OF LAND COVER/LAND USE CHANGESCAUSED BY THE NUCLEAR POWER PLANT CONSTRUCTION. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-3/W8, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, A. Improving the Accuracy of Global DEM of Differences (DoD) in Google Earth Engine for 3-D Change Detection Analysis. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 12332–12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloud-Based Remote Sensing with Google Earth Engine: Fundamentals and Applications; Cardille, J. A., Crowley, M.A., Saah, D., Clinton, N.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; ISBN 978-3-031-26587-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Liao, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, S. Long Time-Series Mapping and Change Detection of Coastal Zone Land Use Based on Google Earth Engine and Multi-Source Data Fusion. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentaw, A.E.; Abegaz, A. Analyzing Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using Google Earth Engine and Random Forest Algorithm and Their Implications to the Management of Land Degradation in the Upper Tekeze Basin, Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 3937558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gong, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Hu, T.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, J.; et al. Mapping Global Urban Boundaries from the Global Artificial Impervious Area (GAIA) Data. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboureh, A.; Ebrahimy, H.; Azadbakht, M.; Bian, J.; Amani, M. RUESVMs: An Ensemble Method to Handle the Class Imbalance Problem in Land Cover Mapping Using Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atef, I.; Ahmed, W.; Abdel-Maguid, R.H. Modelling of Land Use Land Cover Changes Using Machine Learning and GIS Techniques: A Case Study in El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M. Google Earth Engine (GEE) Cloud Computing Based Crop Classification Using Radar, Optical Images and Support Vector Machine Algorithm (SVM). In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 3rd International Multidisciplinary Conference on Engineering Technology (IMCET); IEEE: Beirut, Lebanon, December 8, 2021; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.H.; AL-Hameedawi, A.N.M.; Ismael, H.S. Supervised Classification Model Using Google Earth Engine Development Environment for Wasit Governorate. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 961, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Iizuka, K.; Bragais, M.A.; Endo, I.; Magcale-Macandog, D.B. Employing Crowdsourced Geographic Data and Multi-Temporal/Multi-Sensor Satellite Imagery to Monitor Land Cover Change: A Case Study in an Urbanizing Region of the Philippines. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 64, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Z.; Dervisoglu, A. Determination of Urban Areas Using Google Earth Engine and Spectral Indices; Esenyurt Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Geoinformatics 2023, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magidi, J.; Ahmed, F. Assessing Urban Sprawl Using Remote Sensing and Landscape Metrics: A Case Study of City of Tshwane, South Africa (1984–2015). Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2019, 22, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safira; Amiren, M. ; Nazhifah, S.A.; Rusdi, M.; Nizamuddin; Misbullah, A. Comparison of Support Vector Machine and Random Forest Methods on Sentinel-2A Imagery for Land Cover Identification in Banda Aceh City Using Google Earth Engine. Indones. J. Comput. Sci. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W.; Elias, E.; Warkineh, B.; Tekalign, M.; Abebe, G. Modeling of Land Use and Land Cover Changes Using Google Earth Engine and Machine Learning Approach: Implications for Landscape Management. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, J. Dynamic Monitoring of Urban Built-up Object Expansion Trajectories in Karachi, Pakistan with Time Series Images and the LandTrendr Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi Garajeh, M.; Haji, F.; Tohidfar, M.; Sadeqi, A.; Ahmadi, R.; Kariminejad, N. Spatiotemporal Monitoring of Climate Change Impacts on Water Resources Using an Integrated Approach of Remote Sensing and Google Earth Engine. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolli, M.K.; Opp, C.; Karthe, D.; Groll, M. Mapping of Major Land-Use Changes in the Kolleru Lake Freshwater Ecosystem by Using Landsat Satellite Images in Google Earth Engine. Water 2020, 12, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Mutanga, O. Google Earth Engine Applications Since Inception: Usage, Trends, and Potential. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, G.; Mund, J.-P.; Rahaman, K.J. Detection of Urban Expansion Using the Indices-Based Built-Up Index Derived from Landsat Imagery in Google Earth Engine. GI_Forum 2023, 1, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Saber, M.; Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H.; Homayouni, S. Urban Land Use and Land Cover Change Analysis Using Random Forest Classification of Landsat Time Series. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Hou, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, P. Review of Land Use and Land Cover Change Research Progress. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 113, 012087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demessie, S.F.; Dile, Y.T.; Bedadi, B.; Tarkegn, T.G.; Bayabil, H.K.; Sintayehu, D.W. Assessing and Projecting Land Use Land Cover Changes Using Machine Learning Models in the Guder Watershed, Ethiopia. Environ. Chall. 2025, 18, 101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, L.; Rai, R. Land Use and Land Cover Change Analysis Using Google Earth Engine in Manamati Watershed of Kathmandu District, Nepal. Third Pole J. Geogr. Educ. 2022, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukika, K.N.; Keesara, V.R.; Sridhar, V. Analysis of Land Use and Land Cover Using Machine Learning Algorithms on Google Earth Engine for Munneru River Basin, India. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, B.R.; Tiwari, S.; Dwivedi, C.S.; Pandey, A.C.; Singh, B.; Behera, M.D.; Kumar, N. Comparative Assessment of Satellite-Based Models through Planetscope and Landsat-8 for Determining Physico-Chemical Water Quality Parameters in Varuna River (India). Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanelli, R.; Nascetti, A.; Cirigliano, R.V.; Di Rico, C.; Leuzzi, G.; Monti, P.; Crespi, M. Monitoring the Impact of Land Cover Change on Surface Urban Heat Island through Google Earth Engine: Proposal of a Global Methodology, First Applications and Problems. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selka, I.; Mokhtari, A.; Tabet Aoul, K.; Bengusmia, D.; Kacemi, M.; Djebbar, K. Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Land Cover Changes on Surface Temperature Dynamics Using Google Earth Engine: A Case Study of Tlemcen Municipality, Northwestern Algeria (1989–2019). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, A.; Dosiou, A.; Bakousi, A.; Karachaliou, E.; Tavantzis, I.; Stylianidis, E. Assessing Spatial Correlations Between Land Cover Types and Land Surface Temperature Trends Using Vegetation Index Techniques in Google Earth Engine: A Case Study of Thessaloniki, Greece. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Hu, G.; Li, M.; Yao, Y.; Li, X. An Online Tool with Google Earth Engine and Cellular Automata for Seamlessly Simulating Global Urban Expansion at High Resolutions. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, A.; Gupta, M.K.; Shrivastava, V. Techniques and Challenges of the Machine Learning Method for Land Use/Land Cover (LU/LC) Classification in Remote Sensing Using the Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2023, 11, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Hou, Y.; Dou, Y.; Lu, D.; Yang, S. Mapping Global Urban Impervious Surface and Green Space Fractions Using Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, P.; Bullock, E.L.; Woodcock, C.E.; Olofsson, P. A Suite of Tools for Continuous Land Change Monitoring in Google Earth Engine. Front. Clim. 2020, 2, 576740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Kuch, V.; Lehnert, L.W. Land Cover Classification Using Google Earth Engine and Random Forest Classifier—The Role of Image Composition. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Islam, F.; Waseem, L.A.; Tariq, A.; Nawaz, M.; Islam, I.U.; Bibi, T.; Rehman, N.U.; Ahmad, W.; Aslam, R.W.; et al. Comparison of Three Machine Learning Algorithms Using Google Earth Engine for Land Use Land Cover Classification. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 92, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Liang, W.; Fu, B.; Zhang, W.; Yan, J.; Lü, Y.; Yue, C.; Jin, Z.; Lan, Z.; Li, S.; et al. Mapping Land Use/Cover Dynamics of the Yellow River Basin from 1986 to 2018 Supported by Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewunetu, A.; Abebe, G. Integrating Google Earth Engine and Random Forest for Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection and Analysis in the Upper Tekeze Basin. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ienco, D.; Interdonato, R.; Gaetano, R.; Ho Tong Minh, D. Combining Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Satellite Image Time Series for Land Cover Mapping via a Multi-Source Deep Learning Architecture. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 158, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhu, M.; Liang, Y.; Qin, G.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Land Use/Land Cover Change and Their Driving Factors in the Yellow River Basin of Shandong Province Based on Google Earth Engine from 2000 to 2020. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Khazaei, M.; Alavipanah, S.K.; Weng, Q. Google Earth Engine for Large-Scale Land Use and Land Cover Mapping: An Object-Based Classification Approach Using Spectral, Textural and Topographical Factors. GIScience Remote Sens. 2021, 58, 914–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, N.; Pebesma, E.; Câmara, G. Using Google Earth Engine to Detect Land Cover Change: Singapore as a Use Case. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 51, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Jobaer, M.A.; Haque, S.F.; Islam Shozib, M.S.; Limon, Z.A. Mapping and Monitoring Land Use Land Cover Dynamics Employing Google Earth Engine and Machine Learning Algorithms on Chattogram, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of the Study Selection Process, showing the selection criteria and mechanism for excluding articles that do not match the scope of our study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of the Study Selection Process, showing the selection criteria and mechanism for excluding articles that do not match the scope of our study.

Figure 2.

Timeline of research trends through scientific databases on solely GEE and GEE & LULC studies (2011-2025). The timeline shows an overall growth of GEE and LULC-related studies over the years.

Figure 2.

Timeline of research trends through scientific databases on solely GEE and GEE & LULC studies (2011-2025). The timeline shows an overall growth of GEE and LULC-related studies over the years.

Figure 3.

Number of selected studies by year, showing that most of the GEE and LULC-related studies were conducted from 2020 onward.

Figure 3.

Number of selected studies by year, showing that most of the GEE and LULC-related studies were conducted from 2020 onward.

Figure 4.

Geographical Distribution of Case Studies by Country. Researchers from China contribute the highest percentage of publications, representing 27% of total reviewed articles, followed by India 13%.

Figure 4.

Geographical Distribution of Case Studies by Country. Researchers from China contribute the highest percentage of publications, representing 27% of total reviewed articles, followed by India 13%.

Figure 5.

Percentage of articles’ study scale on LULC topics related to GEE, representing the variety of case studies from a large-scale level (globally) to a small-scale level (e.g., river basins and watersheds).

Figure 5.

Percentage of articles’ study scale on LULC topics related to GEE, representing the variety of case studies from a large-scale level (globally) to a small-scale level (e.g., river basins and watersheds).

Figure 6.

RF, SVM, and CART classifiers’ frequency and accuracy, demonstrating the prevalence of utilizing RF algorithms for data classification tasks over the reviewed studies, as evidenced by providing the highest accuracy range.

Figure 6.

RF, SVM, and CART classifiers’ frequency and accuracy, demonstrating the prevalence of utilizing RF algorithms for data classification tasks over the reviewed studies, as evidenced by providing the highest accuracy range.

Figure 7.

The most common satellite data used in the reviewed articles represent a remarkable prevalence of utilizing Landsat data, followed by Sentinel datasets.

Figure 7.

The most common satellite data used in the reviewed articles represent a remarkable prevalence of utilizing Landsat data, followed by Sentinel datasets.

Figure 8.

The top six most frequently used keywords in the reviewed articles highlight dominant research themes related to GEE and LULC.

Figure 8.

The top six most frequently used keywords in the reviewed articles highlight dominant research themes related to GEE and LULC.

Figure 9.

Word cloud visualization of keywords extracted from the reviewed articles, illustrating the prominence and diversity of terms used in GEE and LULC-related studies.

Figure 9.

Word cloud visualization of keywords extracted from the reviewed articles, illustrating the prominence and diversity of terms used in GEE and LULC-related studies.

Table 1.

Comparison of Cloud-Based Platforms: Google Earth Engine, AWS, and Microsoft Azure.

Table 1.

Comparison of Cloud-Based Platforms: Google Earth Engine, AWS, and Microsoft Azure.

| Feature |

Google Earth Engine (GEE) |

Amazon Web Services (AWS) |

Microsoft Azure |

| Satellite Imagery Coverage |

Landsat, Sentinel, MODIS, NOAA, ALOS, and many others. |

Landsat-8, Sentinel-1/2, NOAA, DigitalGlobe, Global Model Outputs. |

Landsat & Sentinel-2 (North America), MODIS. |

| Volume of Data |

Significantly massive volumes of remote sensing data. |

Limited amount of data. |

Limited geographic data (covering mainly North America). |

| AI/ML Tools |

Integrated cloud-based AI/ML tools and APIs. |

Supports AI/ML through cloud infrastructure with fewer domain-specific requirements. |

AI/ML capabilities via Azure Machine Learning services. |

| Cost |

Free access for researchers and public users. |

Paid services, pricing based on usage. |

Paid services, pricing based on usage. |

| Historical Archive |

Extensive data have been archived, including Landsat data since 1972. |

Varies, generally more recent datasets. |

MODIS since 2000, Landsat & Sentinel-2 for North America since 2013. |

| Remote Sensing Usability |

Highly optimized for remote sensing applications. |

A general cloud platform requires more user setup. |

General cloud platform, less optimized for RS specifically. |

Table 2.

Scope and main findings of previous review articles in the GEE topic.

Table 2.

Scope and main findings of previous review articles in the GEE topic.

| Study |

Scope |

Main findings |

| [11] |

A comprehensive analysis was conducted on multiple factors of GEE, involving its data catalog, system structure, functionalities, data dissemination mechanisms, efficiency, applications, and reported challenges. |

Provided a summary of frequently used datasets in Google Earth Engine’s data catalog.

Discussed a simplified system architecture diagram.

The paper illustrates a summary of Google Earth Engine functions.

Examined GEE System modeling, structure, and performance assessment.

Evaluate the data dissemination procedure and approaches.

The paper discussed future directions and challenges in utilizing GEE as a valuable tool for analyzing global issues. |

| [47] |

Conducted an intensive analysis of usage patterns on the GEE platform, focusing on determining its adoption by researchers in developing countries. |

The highest number of articles was published in the journals “Remote Sensing”, followed by “Remote Sensing of Environment”.

A wide range of applications was conducted, involving different areas of research such as forestry and vegetation, as well as investigating various medical diseases such as Malaria.

The most widely utilized data in the research were Landsat imagery datasets.

GEE usage was primarily associated with institutions located in developed countries, and most study sites were also situated in these regions.

A limited number of publications were conducted by institutions located in less developed nations. |

| [25] |

This special issue, authored by experts in the field, illustrates 22 papers that examine key applications of Google Earth Engine (GEE). The topics covered included vegetation applications and mapping, land-cover changes, agricultural and disaster management, as well as various areas within related disciplines. |

The practical implementation of GEE across a range of applications.

GEE is capable of processing large datasets at different scales and developing automated models suitable for operational use.

There was a higher level of GEE usage in developed countries compared to developing regions such as Africa.

Landsat was recognized as the most extensively utilized dataset. |

[14]

|

A review was conducted on 349 scientific papers that utilized GEE as a leading platform, evaluating various factors including the datasets and satellite sensors used, areas of interest, data resolutions, applications, methodologies, and analytical strategies. |

Demonstrated and discussed a wide range of GEE-related papers in different disciplines, such as urbanization studies and environmental challenges at both national and worldwide levels.

Remotely sensed data were employed in 90% of the reviewed articles, while the remaining 10% relied on pre-processed or pre-existing data sets for their research.

Landsat imagery data sets with moderate spatial resolution were intensively utilized.

The most commonly applied techniques for processing utilized data sets were Random Forest and Linear Regression Algorithms.

The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was used in 27% of the reviewed articles for vegetation, crop, and land-cover analysis, as well as for research on drought and desertification.

The results of this study demonstrate that GEE has achieved remarkable advancements in tackling global challenges related to geospatial data processing. |

[12]

|

Examined 450 scientific papers focusing on various applications of the GEE platform, including its capabilities, data sets, functionalities, benefits, challenges, and diverse aspects of applications. |

Landsat and Sentinel datasets have been extensively utilized by users of Google Earth Engine (GEE).

Data classification frequently employs supervised machine learning algorithms, with Random Forest (RF) being a commonly used example.

The intensive use of GEE covers a broad range of applications, including land use and land cover (LULC) analysis, hydrological studies, urbanization modeling, disaster monitoring, global warming assessment, and various data processing tasks.

Recent years have witnessed a notable rise in GEE-related publications. In the future, it is expected that an even broader range of users from diverse disciplines will adopt GEE to undertake their challenges in big data processing. |

| [7] |

A comprehensive review analysis was conducted on the applications and evolving trends of Google Earth (GE) and Google Earth Engine (GEE), focusing on scientific papers published up to January 2021. |

Over the 14 years from 2006 to 2020, the number of publications that employed GE and GEE increased from 2 to 530, marking a significant growth in the research interest in GE and GEE.

Compared to GEE, GE research spanned various disciplines of study, including biology, education, health, and economics, and was published in a broader range of scientific journals.

Keywords such as "land cover", "water", "model", "vegetation", and "forest" were commonly used in both studies related to GE and GEE.