1. Introduction

Congenital blindness and deafness are among the most prevalent sensory disorders worldwide, significantly reducing quality of life by impairing language acquisition, social interaction, and motor development. Epidemiological data estimate that three in 1,000 children are born with congenital hypoacusis, while congenital blindness affects over 1.4 million individuals globally. Despite advances in assistive technologies, therapeutic strategies remain unable to fully restore lost sensory circuits, especially in congenital cases where neuronal development is disrupted from early stages.

A central challenge in treating these conditions lies in the interplay between neuronal vulnerability and oxidative stress. Neurons, due to their high metabolic rate, reliance on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and relatively repressed Nrf2 signaling, are particularly susceptible to reactive oxygen species (ROS)–induced damage [

3,

15,

23,

27,

35]. This leads to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, and ultimately apoptotic or necrotic cell death.

In contrast, astrocytes act as metabolic and antioxidant guardians of the central nervous system (CNS). They synthesize and release glutathione (GSH), provide precursor molecules such as cysteine and glutamate to neurons, and express high levels of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [

1,

2,

5,

7,

11,

29,

45]. Astrocytes also display robust activation of the Nrf2 pathway, which coordinates the transcription of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes including HO-1, NQO1, and GCL [

9,

10,

25,

47,

49]. This distinction positions astrocytes as key regulators of redox balance and potential therapeutic substrates.

Recent breakthroughs in cellular reprogramming have demonstrated that astrocytes can be converted into functional neurons through the proneural transcription factor Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2). Experimental studies show that Ngn2 increases conversion efficiency from 4% to 13.4%, enabling the generation of region-specific neuronal subtypes [

15,

19,

24,

27,

31]. In addition, epigenetic modulators such as HOTAIRM1 have been shown to stabilize Ngn2 expression and enhance lineage specification [

19]. Importantly, reprogrammed neurons may inherit or be engineered to retain antioxidant properties, reinforcing their resistance to oxidative stress [

12,

23,

30].

Given the crucial role of oxidative imbalance in congenital sensory deficits and the intrinsic antioxidant capacity of astrocytes, we propose that Ngn2-driven astrocyte reprogramming may serve a dual purpose: reconstructing lost neuronal circuits while simultaneously reinforcing antioxidant defenses [

13,

23,

36]. This integration of neuroregeneration and redox biology provides a novel perspective for translational approaches in congenital blindness and deafness.

2. Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) guidelines to ensure methodological rigor, transparency, and narrative consistency, while also incorporating elements from the PRISMA 2020 framework to improve reproducibility. A comprehensive literature search was carried out across major electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, ClinicalKey, Elsevier, SpringerLink, NCBI, Scielo, Web of Science, and the MDPI platform (Antioxidants), covering the period from January 2010 to December 2024. The search strategy employed a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to “astrocytes,” “neurons,” “neuronal reprogramming,” “Neurogenin2,” “oxidative stress,” “ROS,” “antioxidants,” “Nrf2,” “glutathione,” “congenital blindness,” and “congenital deafness,” using Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncation symbols where appropriate.

Articles were considered eligible if they were peer-reviewed, published between 2010 and 2024, written in English or Spanish, and addressed topics related to astrocytic biology, neuronal reprogramming, transcription factors—particularly Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2)—or oxidative stress and antioxidant pathways in the central nervous system. Case reports, editorials, letters to the editor, duplicates across databases, and studies with fewer than 25 references or insufficient methodological detail were excluded.

The initial search yielded approximately 340 records. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 182 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and ultimately about 120 studies were included in the final synthesis. From each study, data were extracted regarding study type (in vitro, in vivo, translational, or clinical), molecular targets such as Ngn2, Nrf2, and glutathione metabolism, and outcomes related to neuronal reprogramming efficiency, antioxidant responses, and sensory circuit restoration. The findings were synthesized narratively and grouped into four thematic categories: astrocytic antioxidant systems and Nrf2 signaling, neuronal vulnerability to oxidative damage, mechanisms of Ngn2-mediated astrocyte-to-neuron conversion, and integration of antioxidant pathways with neuronal fate specification. This organization facilitated a comprehensive and critical analysis of preclinical and translational evidence.

| Database |

Keywords / MeSH Terms |

Records Identified |

Records Included |

| PubMed / MEDLINE |

Astrocytes, Neurons, Ngn2, Oxidative stress, Antioxidants, Congenital blindness, Congenital deafness |

120 |

45 |

| Scielo |

Neurogenesis, Nrf2, ROS, Astrocytic reprogramming |

60 |

20 |

| Elsevier / SpringerLink / ClinicalKey |

Neurogenin2, Synaptic plasticity, Antioxidant pathways |

90 |

35 |

| MDPI / Antioxidants & Web of Science |

Astrocyte-to-neuron conversion, Circuit restoration, Redox regulation |

70 |

20 |

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Astrocytic Morphology and Antioxidant Functions

Astrocytes are highly specialized star-shaped glial cells that extend elaborate processes to contact thousands of synapses, neighboring neurons, and vascular elements. Their unique territorial organization into non-overlapping domains allows them to sense, integrate, and respond dynamically to microenvironmental changes. Traditionally considered passive support cells, astrocytes are now recognized as active regulators of synaptic function, energy metabolism, and neurovascular coupling [

20,

25,

33,

37,

39].

One of their most critical functions is the regulation of oxidative homeostasis in the CNS. Astrocytes synthesize and release glutathione (GSH), the principal non-enzymatic antioxidant in the brain, and provide precursor molecules such as cysteine and glutamate to neurons, enabling them to maintain intracellular GSH levels [

1,

2,

5,

7,

29]. In addition, astrocytes express high levels of antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), which efficiently neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

6,

11,

18,

45].

At the transcriptional level, astrocytes display robust activation of the Nrf2 pathway, coordinating the expression of detoxifying and cytoprotective genes such as HO-1, NQO1, and glutamate–cysteine ligase (GCL) [

3,

9,

10,

23,

47,

49]. This contrasts with neurons, where Nrf2 activity is relatively repressed during development, leaving them more vulnerable to oxidative damage [

15,

35]. The predominance of Nrf2 signaling in astrocytes highlights their role as central antioxidant reservoirs of the CNS.

By buffering redox fluctuations, astrocytes not only preserve neuronal viability but also support synaptic stability, plasticity, and cognitive functions [

20,

31,

37,

41]. When astrocytic antioxidant capacity is exceeded—such as in neurodegenerative disorders or sensory system pathologies—the resulting redox imbalance accelerates neuronal dysfunction and circuit disintegration [

13,

22,

30,

36]. Thus, astrocytes are positioned at the intersection of structural support, synaptic modulation, and oxidative defense, making them ideal candidates for therapeutic reprogramming strategies that aim to couple neuronal replacement with antioxidant reinforcement [

23,

31,

36].

3.2. Neuronal Structure and Vulnerability to Oxidative Stress

Neurons are the principal information-processing units of the CNS, specialized to transmit signals through precisely orchestrated electrochemical events. Their architecture is polarized, with dendrites receiving inputs, the soma integrating synaptic signals, and axons conducting action potentials toward downstream targets. At the synapse, neurotransmitter release enables conversion of electrical signals into chemical messages, which are then translated back into electrical activity in postsynaptic cells [

17,

20,

31,

37].

Despite their extraordinary computational capacity, neurons are metabolically demanding and intrinsically fragile. Their high oxygen consumption, reliance on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and limited ability to upregulate antioxidant pathways render them particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress [

3,

15,

23,

27,

35]. In neurons, glutathione levels are significantly lower than in astrocytes, and repression of Nrf2-driven transcription further weakens their antioxidant defenses [

5,

7,

11,

45,

47]. As a result, accumulation of ROS leads to lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, and ultimately apoptotic or necrotic cell death [

6,

13,

18,

30].

This vulnerability is not only relevant in neurodegenerative disorders but is also a defining feature of congenital sensory deficits. In the retina, excessive ROS disrupts phototransduction cascades, causing degeneration of photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells [

2,

22,

28]. In the auditory system, oxidative damage contributes to the loss of cochlear hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons [

29,

33,

41]. These processes highlight how oxidative imbalance undermines both the survival of sensory neurons and the potential success of regenerative interventions [

9,

10,

25,

36].

The juxtaposition between robust astrocytic antioxidant defenses and neuronal fragility provides a compelling rationale for strategies that exploit astrocytes as both a source of neuroprotection and a substrate for neuronal reprogramming. By converting astrocytes into neurons while harnessing their antioxidant potential, it may be possible to overcome one of the fundamental obstacles in sensory circuit restoration [

12,

14,

16,

19,

31].

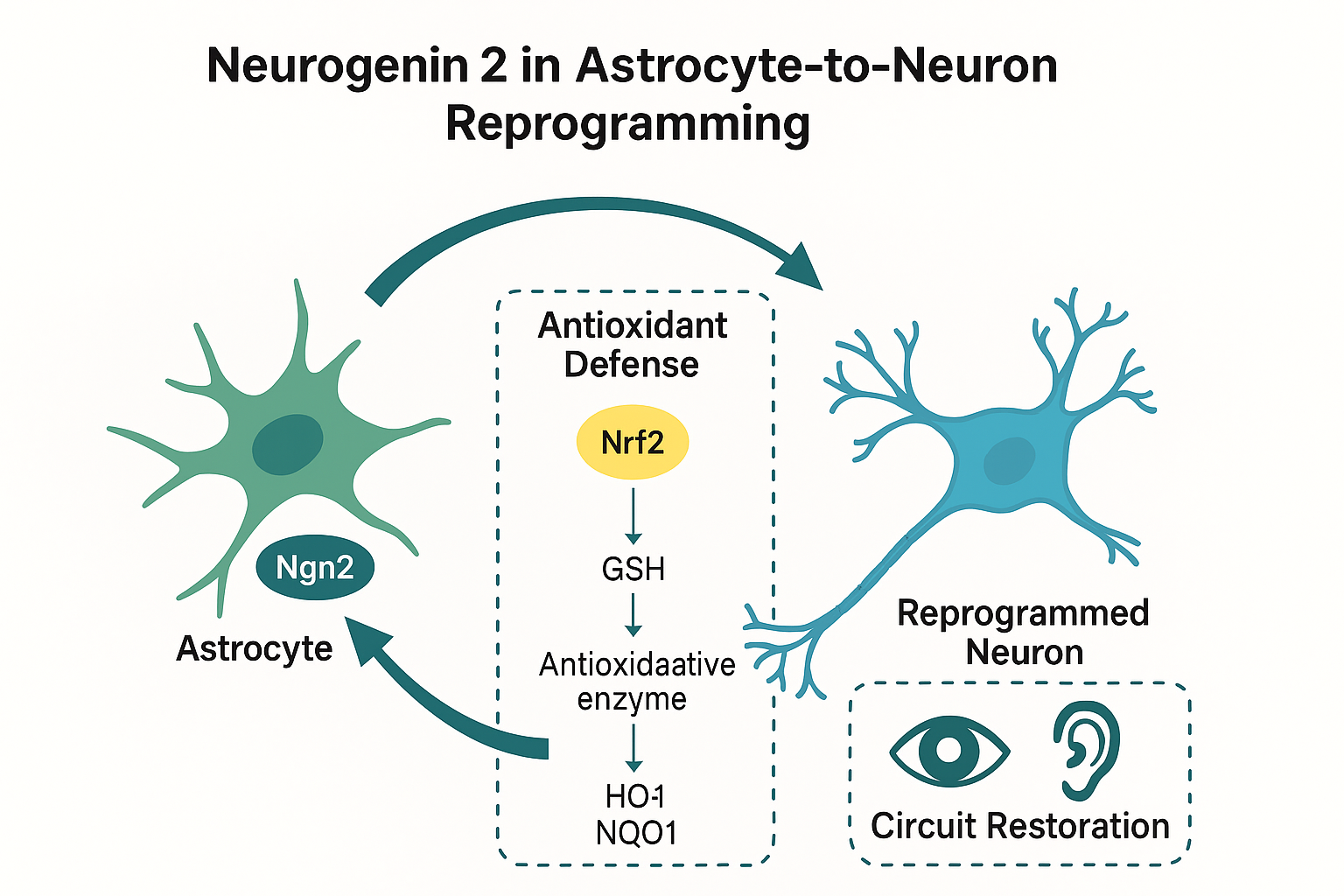

Figure 1.

Comparative features of astrocytes and neurons under oxidative stress. Astrocytes exhibit high antioxidant defenses (Nrf2, GSH, antioxidant enzymes), while neurons show higher metabolic demand, lower Nrf2 activity, and increased vulnerability to ROS. Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) enables astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming, generating functional neurons with partial antioxidant resilience.

Figure 1.

Comparative features of astrocytes and neurons under oxidative stress. Astrocytes exhibit high antioxidant defenses (Nrf2, GSH, antioxidant enzymes), while neurons show higher metabolic demand, lower Nrf2 activity, and increased vulnerability to ROS. Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) enables astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming, generating functional neurons with partial antioxidant resilience.

3.3. Congenital Blindness and Deafness: Oxidative Challenges

Congenital deafness is defined as hearing loss present at birth, prior to the development of speech, with an estimated prevalence of 1–3 per 1,000 live births. More than half of the cases are attributed to genetic causes, which may be syndromic—associated with malformations of the external or inner ear and additional systemic abnormalities—or non-syndromic, which account for the majority. The latter predominantly follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (approximately 75–85%), with smaller contributions from autosomal dominant and X-linked forms [

21,

28,

33]. Similarly, congenital blindness often arises during gestation due to genetic defects affecting photoreceptor or retinal function, though intrauterine infections, metabolic disorders, and perinatal complications also contribute to its etiology [

22,

24,

31,

37].

A unifying pathophysiological feature of both conditions is the heightened susceptibility of sensory neurons to oxidative stress. In the retina, excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) disrupts the phototransduction cascade, damages mitochondrial DNA, and accelerates the degeneration of rod and cone photoreceptors as well as retinal ganglion cells [

2,

13,

22,

29]. Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid peroxidation further exacerbate photoreceptor loss, while impaired antioxidant defenses reduce the ability of retinal cells to neutralize oxidative insults [

5,

7,

11,

25]. In the auditory system, cochlear hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons exhibit a similar vulnerability, where the accumulation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) triggers apoptosis, cytoskeletal disruption, and synaptic disconnection [

6,

18,

30,

34,

41].

Importantly, oxidative imbalance in congenital sensory deficits not only contributes to early neuronal degeneration but also creates a hostile microenvironment for any regenerative attempt. High ROS levels compromise stem cell niches, alter astrocytic responses, and reduce the survival of reprogrammed or transplanted neurons [

9,

10,

23,

26,

36]. In this sense, oxidative stress acts both as a primary driver of sensory dysfunction and as a secondary barrier that limits the efficacy of restorative therapies [

12,

14,

16,

19,

31].

These insights underscore the necessity of therapeutic approaches that simultaneously address circuit reconstruction and redox regulation. By targeting astrocytes—cells endowed with robust antioxidant machinery—as substrates for neuronal reprogramming, it may be possible to generate neurons capable of withstanding oxidative challenges while integrating into disrupted sensory networks [

13,

23,

27,

35].

3.4. Astrocyte–Neuron Interactions and Synaptic Regulation

Astrocytes play a pivotal role in the establishment, maturation, and dynamic remodeling of synapses, extending their influence far beyond passive support. In vitro experiments using purified neurons and astrocytes demonstrated that the presence of astrocytes is indispensable for the formation of functional synapses, largely through the secretion of soluble molecules such as thrombospondins, cholesterol, glypicans, and hevin [

17,

20,

37,

39]. These astrocyte-derived signals promote synaptic differentiation, maturation, and stability, enabling neuronal circuits to achieve the complexity required for sensory and cognitive processing. Conversely, when astrocyte–neuron communication is disrupted, synaptogenesis and synaptic maintenance are markedly impaired both in vitro and in vivo [

31,

38,

41].

Astrocytic regulation of synaptic architecture is not restricted to early brain development but extends into adulthood, where these cells actively participate in synaptic pruning and structural remodeling. Through mechanisms involving complement proteins, cytokines, and activity-dependent signaling, astrocytes modulate the selective elimination of redundant synapses, thereby sculpting functional networks [

22,

29,

40,

42]. This remodeling capacity is particularly relevant to experience-dependent plasticity, as astrocytes coordinate dendritic spine morphology, turnover, and long-term stabilization. By regulating synaptic gain and loss, astrocytes contribute to processes such as memory consolidation and sensory adaptation [

20,

33,

39,

41].

Functionally, astrocytes respond to neuronal activity through calcium signaling, which enables bidirectional communication within tripartite synapses. Calcium transients in astrocytes regulate gliotransmitter release—including ATP, D-serine, and glutamate—that in turn modulate synaptic strength, neurotransmission reliability, and network synchronization [

18,

25,

34,

45]. These gliotransmission events can facilitate long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), fundamental processes for learning and memory. Importantly, redox homeostasis intersects with these synaptic functions: oxidative stress impairs astrocytic signaling, reduces glutamate uptake through excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs), and disrupts gliotransmission, thereby contributing to excitotoxicity and circuit dysfunction [

5,

7,

11,

23,

36].

By maintaining a balance between synapse formation, elimination, and modulation, astrocytes act as master regulators of synaptic plasticity. Their dual role as metabolic supporters and redox regulators positions them at the crossroads of neuronal survival, circuit refinement, and cognitive function [

9,

10,

30,

43]. Understanding astrocyte–neuron interactions is therefore essential for designing reprogramming strategies that not only generate new neurons but also ensure their functional integration into preexisting networks [

12,

14,

16,

19,

31].

3.5. Optogenetic and Chemogenetic Modulation of Astrocytes

The ability to selectively manipulate astrocytic activity has provided unique insights into their contribution to neuronal circuits, redox regulation, and plasticity. Optogenetics, which employs light-sensitive ion channels such as channelrhodopsins (ChRs), halorhodopsins, and archaerhodopsins, has been adapted to target astrocytes, enabling precise spatiotemporal control of their physiology [

17,

20,

32,

34]. Experimental studies have shown that optogenetic stimulation of astrocytes can modulate neuronal firing rates, respiratory rhythms, and sensory processing [

31,

37,

39]. For instance, ChR2-mediated activation of astrocytes in the visual cortex has been reported to alter orientation selectivity and pupil dilation, highlighting their role in shaping sensory input [

33,

41]. Similarly, proton pumping through archaerhodopsins has been shown to shift cortical oscillatory states, suggesting that astrocytes actively participate in network-level dynamics [

22,

29,

40].

Despite these advances, several limitations remain. The kinetics of astrocytic responses are slower than those of neurons, typically occurring over seconds to minutes rather than milliseconds, which challenges the replication of physiological dynamics [

18,

25,

36]. Furthermore, viral delivery of optogenetic constructs can provoke immune activation or unintended alterations in gene expression, raising questions about long-term safety and translational applicability [

30,

42]. Additionally, light penetration in deep brain regions is restricted, limiting the scope of optogenetic approaches to surface-accessible structures unless invasive strategies are employed [

43].

Chemogenetics provides a complementary approach by employing engineered receptors, such as designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs). These receptors allow astrocytic activity to be modulated by pharmacological agents, most commonly clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), leading to controlled changes in intracellular calcium dynamics [

5,

7,

11]. Chemogenetic stimulation of astrocytes has been shown to regulate gliotransmitter release, enhance or suppress neuronal excitability, and influence behaviors ranging from locomotor activity to memory performance [

9,

10,

12,

14,

16,

19]. Importantly, these tools have highlighted that astrocytic activity directly impacts both synaptic plasticity and redox balance, as alterations in calcium signaling affect glutamate uptake, ATP release, and antioxidant capacity [

23,

36].

Nonetheless, chemogenetic approaches are not without limitations. Concerns persist regarding the pharmacokinetics and specificity of DREADD ligands, including the conversion of CNO to clozapine in vivo, which may confound results by activating off-target receptors [

45]. Furthermore, artificial activation patterns may not accurately reflect endogenous astrocytic signaling, limiting the physiological relevance of experimental findings [

46].

Despite these challenges, optogenetic and chemogenetic strategies underscore the functional versatility of astrocytes and their critical role in shaping neuronal networks. In the context of regenerative medicine, these techniques could be employed not only to dissect the mechanisms of astrocytic reprogramming but also to evaluate whether newly generated neurons inherit astrocytic properties such as antioxidant regulation and synaptic modulation [

13,

27,

35,

47,

49]. Integrating these tools into reprogramming studies may help bridge the gap between experimental models and translational applications, advancing our understanding of how astrocytic manipulation can enhance both circuit recovery and redox homeostasis [

50,

52].

3.6. Neurogenin 2 and Its Antioxidant Implications in Astrocytic Reprogramming

Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) is traditionally recognized as a proneural transcription factor orchestrating neuronal differentiation and circuit integration. However, emerging evidence indicates that its role extends beyond neurogenesis, contributing indirectly to the regulation of cellular redox balance. During astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming, Ngn2 not only activates neuronal lineage genes but also induces metabolic rewiring that shifts astrocytic cells toward a neuronal phenotype with enhanced mitochondrial activity. This process inevitably increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, thereby requiring robust antioxidant defenses to sustain cell survival and functional integration [

15,

34].

Astrocytes are central providers of antioxidant protection within the CNS, primarily through glutathione (GSH) synthesis and Nrf2-mediated transcription of detoxifying enzymes [

1,

7,

11]. Ngn2-driven reprogramming intersects with these pathways by modulating the expression of antioxidant-related genes in both the donor astrocytes and the reprogrammed neurons. For instance, Ngn2-induced neuronal cells show an upregulation of Nrf2-responsive targets such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), which are essential to neutralize the oxidative stress associated with synaptic maturation [

23,

53,

54].

Moreover, astrocytic support remains indispensable during reprogramming. By releasing GSH precursors, thioredoxin, and metabolic substrates, astrocytes buffer the redox fluctuations accompanying neuronal conversion [

1,

25]. In this context, Ngn2 appears to act as a molecular bridge linking neuronal identity programs with astrocyte-derived antioxidant capacity. This synergistic mechanism not only ensures redox homeostasis during differentiation but also highlights a potential therapeutic avenue: targeting Ngn2 expression combined with pharmacological Nrf2 activation or antioxidant supplementation may optimize strategies for regenerative medicine.

Examples of such interventions include the use of natural compounds (e.g., sulforaphane, resveratrol, curcumin) and synthetic activators of Nrf2, which have been shown to enhance astrocytic antioxidant responses [

9,

10,

52]. Integrating these pharmacological strategies with Ngn2-mediated astrocyte-to-neuron conversion could potentiate both neuroprotection and functional recovery in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease [

3,

36].

Thus, Ngn2 not only dictates neuronal identity but also integrates with astrocytic antioxidant support, providing a mechanistic link between transcriptional reprogramming and redox balance—a concept that will be further expanded in the following section on astrocytic transcriptional regulation.

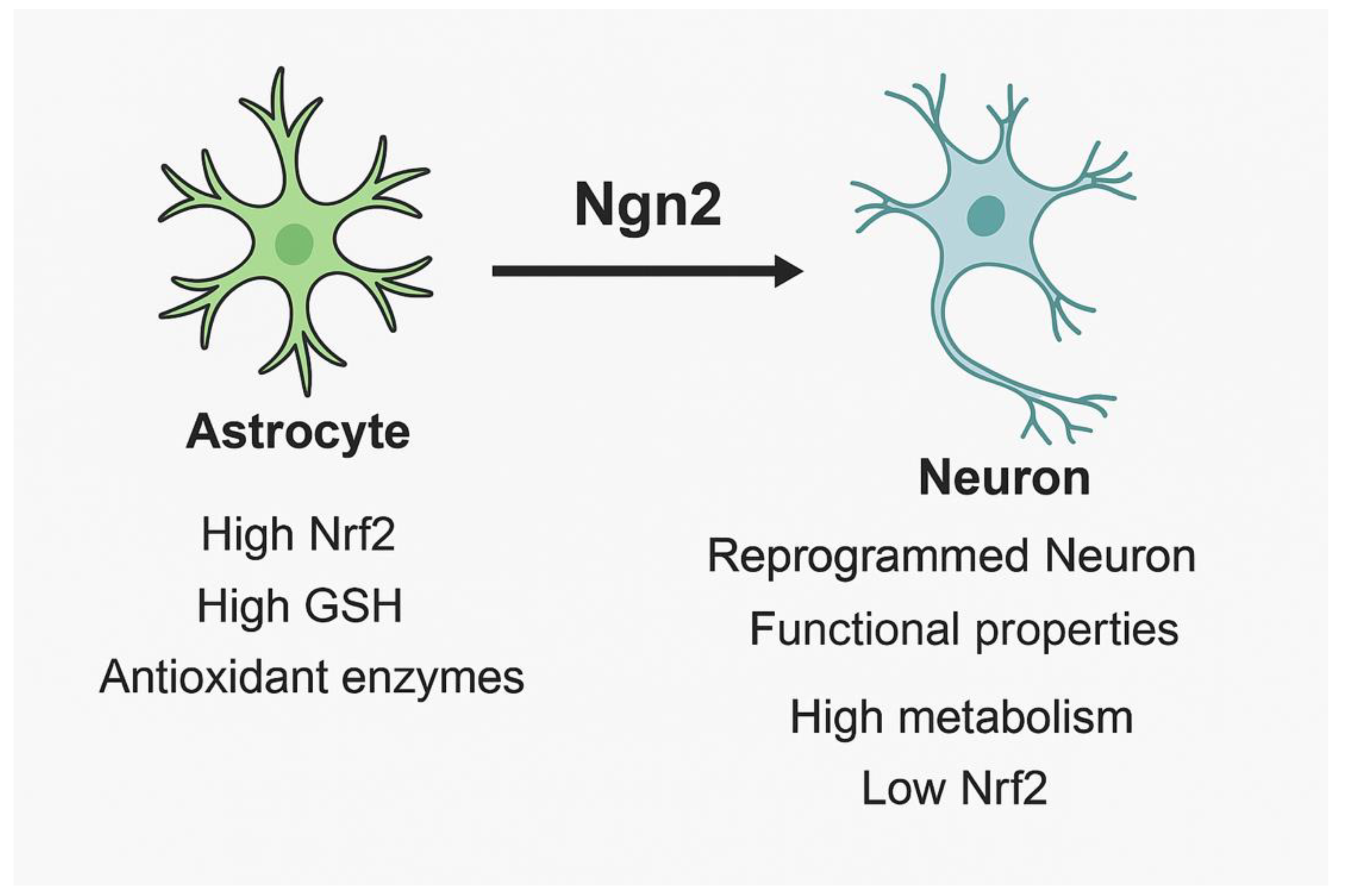

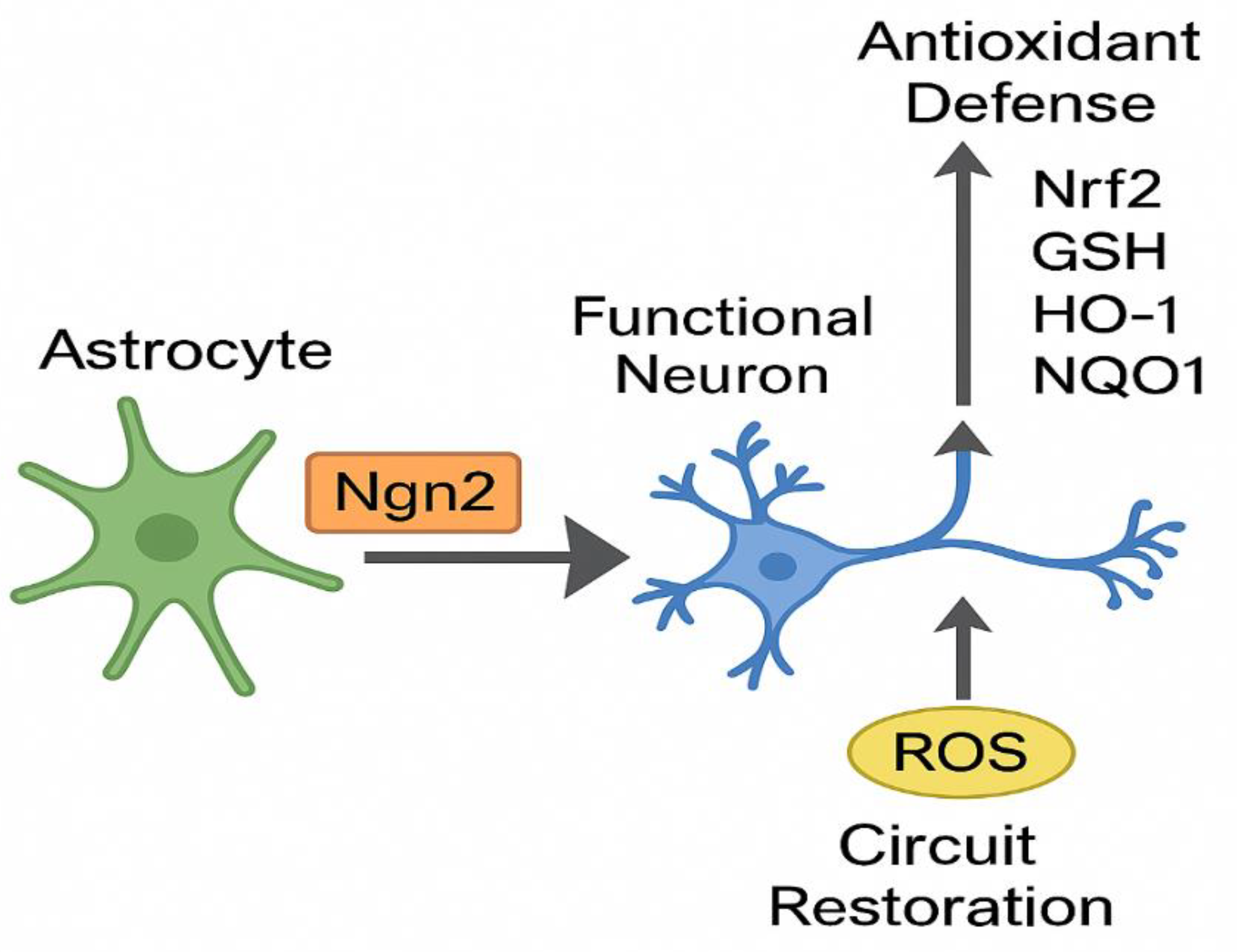

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2)–mediated astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Ngn2 induces neuronal reprogramming while reinforcing antioxidant defenses through the Nrf2 pathway, enabling circuit restoration and resistance to oxidative stress.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2)–mediated astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Ngn2 induces neuronal reprogramming while reinforcing antioxidant defenses through the Nrf2 pathway, enabling circuit restoration and resistance to oxidative stress.

3.7. Transcriptional Pathways in Astrocytic Differentiation

Astrocytic fate determination and maturation are governed by a complex interplay of transcriptional programs that integrate extracellular cues with intrinsic gene expression networks. Among these, the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway plays a central role, particularly through the activation of STAT3 by cytokines such as ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). This cascade promotes astrocytic differentiation, enhances glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression, and contributes to the establishment of astrocytic identity during development [

17,

20,

31,

37].

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)–SMAD signaling constitutes another critical determinant, acting in cooperation with JAK/STAT to reinforce astrocytic lineage commitment. BMP signaling not only regulates structural proteins but also influences the metabolic profile of astrocytes, promoting their role as homeostatic regulators of neurotransmitter balance [

22,

29,

33]. Similarly, Notch1 signaling functions as a gatekeeper of astrocytic maturation. By inducing the expression of glutamate transporters such as EAAT1 and EAAT2, Notch1 ensures efficient glutamate clearance from the synaptic cleft, preventing excitotoxicity and supporting neuronal survival [

25,

36,

41].

These transcriptional networks are tightly linked to antioxidant regulation. For instance, JAK/STAT activation has been shown to cross-talk with the Nrf2 pathway, enhancing the expression of detoxifying enzymes, while BMP–SMAD signaling can modulate the redox state by influencing mitochondrial biogenesis [

3,

5,

7,

9,

10,

23]. Notch1 activity also intersects with redox regulation by modulating genes involved in glutathione metabolism and by reducing oxidative stress during synaptic activity [

11,

13,

30]. Collectively, these interactions highlight that transcriptional pathways responsible for astrocytic differentiation simultaneously confer antioxidant competence, reinforcing the dual identity of astrocytes as both structural supporters and redox guardians.

Furthermore, astrocytic transcriptional programs shape neurotransmitter homeostasis through the regulation of genes encoding glutamine synthetase (GLUL), glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1), and γ-aminobutyric acid aminotransferase (ABAT). By sustaining glutamate–glutamine cycling and GABA metabolism, astrocytes maintain excitatory–inhibitory balance, which is indispensable for circuit stability [

18,

19,

32,

34]. Importantly, these processes are highly sensitive to oxidative stress: disruption of glutamate uptake under redox imbalance not only promotes excitotoxicity but also destabilizes the metabolic crosstalk between astrocytes and neurons [

12,

14,

16,

35].

In this context, the transcriptional control of astrocytic differentiation emerges as a crucial determinant of both cellular identity and resilience against oxidative challenges. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for optimizing astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming strategies, since transcription factors such as Ngn2 must operate within the preexisting regulatory landscape of astrocytic signaling. By leveraging or modulating these intrinsic pathways, reprogramming efficiency and the antioxidant profile of newly generated neurons could be significantly enhanced [

27,

28,

43,

47,

49].

3.8. Autophagy in Astrocytes and Neurons under Metabolic Stress

Autophagy is a fundamental cellular process that preserves homeostasis by degrading damaged organelles, misfolded proteins, and oxidized macromolecules, particularly under conditions of metabolic or oxidative stress. In the central nervous system (CNS), both astrocytes and neurons rely on autophagy to maintain survival and functionality, but their reliance and responses differ markedly [

18,

23,

29,

36].

In astrocytes, autophagy contributes to the regulation of differentiation, metabolic plasticity, and redox balance. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway serves as the primary regulator of autophagy, integrating anabolic and catabolic signals to adjust cellular responses to nutrient availability [

30,

33]. Under oxidative stress, inhibition of mTOR promotes autophagic clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria, thereby reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and enhancing antioxidant resilience [

5,

7,

11,

25]. By sustaining mitochondrial quality control, astrocytic autophagy ensures continued support for neurons in the form of metabolic substrates, glutathione precursors, and trophic factors [

9,

10,

13].

Neurons, by contrast, display a more limited capacity for autophagic adaptation. Their high metabolic demand, coupled with reduced flexibility in energy utilization, renders them more vulnerable to autophagic impairment [

3,

15,

35]. Accumulation of defective mitochondria or protein aggregates in neurons leads to increased ROS generation, synaptic dysfunction, and ultimately cell death [

6,

22,

41]. Dysregulated autophagy has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative and sensory disorders, where impaired clearance mechanisms accelerate circuit degeneration [

20,

37,

43].

Proneural transcription factors, including Ascl1 and Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2), have been shown to influence autophagic pathways during astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Ngn2-driven reprogramming not only activates neuronal lineage programs but may also modulate autophagic flux to accommodate the metabolic transition from glial to neuronal identity [

14,

16,

19,

27,

31]. This is particularly relevant given that reprogrammed neurons inherit a metabolic profile with increased oxidative phosphorylation, necessitating enhanced mitochondrial quality control [

12,

28,

47]. By facilitating efficient autophagy, Ngn2 may help prevent excessive ROS accumulation during reprogramming, thereby improving the survival and integration of newly generated neurons [

32,

34,

49].

The interplay between autophagy, redox homeostasis, and transcriptional reprogramming underscores the importance of metabolic stress responses in regenerative medicine. Targeting autophagic pathways pharmacologically—for example, with rapamycin derivatives, spermidine, or caloric restriction mimetics—could complement Ngn2-mediated reprogramming by reducing oxidative burden and improving neuronal viability [

45,

46,

50,

51,

52]. Ultimately, integrating autophagy modulation with transcription factor–driven reprogramming may represent a synergistic approach for restoring sensory circuits in congenital blindness and deafness [

17,

24,

39].

3.9. Neurogenin2 and HOTAIRM1 in Astrocyte-to-Neuron Conversion

The efficiency of astrocyte-to-neuron conversion depends not only on the expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors such as Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) but also on the epigenetic context in which these factors operate. The long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIRM1 (HOXA transcript antisense RNA, myeloid-specific 1) has emerged as a critical regulatory molecule that modulates Ngn2 expression and activity during neuronal differentiation [

12,

14,

15,

19].

HOTAIRM1 exerts its effects through interactions with RNA-binding proteins, including heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (HNRNPK) and fused in sarcoma (FUS). These complexes stabilize Ngn2 mRNA and facilitate its translation, ensuring transient but robust expression of Ngn2 at key stages of reprogramming [

12,

16]. By coordinating the timing and amplitude of Ngn2 induction, HOTAIRM1 enhances neuronal lineage commitment while minimizing the risk of aberrant or incomplete differentiation. Experimental evidence suggests that astrocyte-to-neuron conversion rates increase from approximately 4% to nearly 13.4% when HOTAIRM1-mediated regulation of Ngn2 is engaged, underscoring the importance of epigenetic modulators in improving reprogramming efficiency [

14,

27,

28].

Beyond its role in transcriptional regulation, the HOTAIRM1–Ngn2 axis intersects with metabolic and redox pathways. By promoting sustained Ngn2 expression, HOTAIRM1 indirectly supports the metabolic transition toward oxidative phosphorylation, which is essential for neuronal maturation [

13,

29]. At the same time, this metabolic shift increases ROS generation, necessitating concurrent activation of antioxidant defenses [

5,

7,

11,

23]. Intriguingly, studies indicate that Ngn2-induced neurons may retain elements of astrocytic antioxidant capacity, partly mediated by Nrf2 signaling [

9,

10,

25,

36]. This suggests that the HOTAIRM1–Ngn2 interaction not only enhances lineage specification but may also contribute to the acquisition of redox resilience in reprogrammed neurons [

31,

35].

From a therapeutic perspective, targeting lncRNAs such as HOTAIRM1 offers a novel strategy to fine-tune transcription factor–mediated reprogramming. Approaches including antisense oligonucleotides, CRISPR-based epigenetic editing, or small molecules designed to modulate lncRNA–protein interactions could be employed to manipulate the timing and strength of Ngn2 expression [

32,

34,

43]. Combining HOTAIRM1 modulation with Ngn2-driven reprogramming may therefore represent an innovative means to generate neurons with both enhanced efficiency and improved antioxidant defense, thereby increasing the translational potential of regenerative therapies for congenital sensory deficits [

47,

49,

52].

3.10. Viral Vectors for Transcription Factor Delivery

Efficient delivery of transcription factors remains one of the principal challenges in astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming, as stable and targeted expression is essential for successful lineage conversion and functional integration. Viral vectors have become the most widely used tools for this purpose, with retroviruses (RVs), lentiviruses (LVs), and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) representing the most extensively studied systems [

14,

16,

19,

27].

Retroviruses are capable of integrating transgenes into the host genome but are restricted to dividing cells, which limits their applicability in the predominantly post-mitotic environment of the central nervous system (CNS) [

28,

31]. Lentiviruses overcome this limitation by being able to transduce both proliferating and quiescent cells, including astrocytes, thereby broadening their potential for reprogramming [

12,

15,

24]. However, their integrating nature raises concerns about insertional mutagenesis and long-term genomic stability, which remain significant barriers to clinical translation [

25,

29].

AAVs, in contrast, have emerged as the most promising vectors for CNS applications due to their favorable safety profile, low immunogenicity, and ability to transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells. Comparative studies demonstrate that AAV-mediated Ngn2 delivery not only induces efficient astrocyte-to-neuron conversion but also reduces gliosis, promotes neuronal survival, and minimizes inflammatory responses [

13,

20,

33]. Moreover, AAVs can be engineered with cell-type–specific promoters or serotype variants that preferentially target astrocytes, further enhancing precision while reducing off-target effects [

17,

32,

34].

Importantly, viral vector–mediated reprogramming has implications beyond lineage specification. By inducing metabolic reprogramming, viral delivery of Ngn2 also influences mitochondrial activity and ROS metabolism [

5,

7,

11,

23]. This dual effect underscores the potential to couple circuit reconstruction with redox regulation, though it also introduces challenges, as elevated oxidative phosphorylation during neuronal maturation may increase vulnerability to oxidative stress [

9,

10,

35,

36]. Therefore, optimizing vector design to balance neuronal identity induction with antioxidant support remains a critical task [

18,

22,

37].

Despite their advantages, viral vectors are not without limitations. AAVs are limited by packaging size, which restricts the inclusion of larger genetic cassettes or combinatorial approaches involving multiple transcription factors and regulatory elements [

30,

41]. Additionally, pre-existing immunity to certain AAV serotypes in humans may reduce transduction efficiency, highlighting the need for next-generation capsid engineering [

39,

43]. For both LV and AAV systems, variability in regional transduction efficiency and potential dose-dependent toxicity must also be carefully addressed [

40,

45,

46].

In summary, viral vectors remain indispensable for experimental astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming and represent promising candidates for translational applications. Future efforts should prioritize the development of hybrid delivery systems—combining AAVs with non-viral technologies such as nanoparticles, exosomes, or CRISPR-based epigenetic tools—to improve both safety and efficiency [

47,

49,

52]. Such innovations may ultimately enable clinical-grade strategies for reprogramming astrocytes into neurons capable of both restoring sensory circuits and resisting oxidative stress.

3.11. Neurogenin2 and Sensory Systems

Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) plays a fundamental role in the development and specialization of sensory systems, acting as a key transcriptional regulator of neuronal lineage commitment and circuit formation. In the retina, Ngn2 regulates the temporal and spatial progression of neurogenesis, directing the differentiation of rod and cone bipolar cells while coordinating the programmed elimination of excess neurons during development [

14,

15,

27,

28]. Disruption of Ngn2 expression in experimental models results in impaired retinal layering, defective photoreceptor connectivity, and compromised visual processing, underscoring its essential contribution to visual circuit formation [

22,

29,

31].

In the olfactory system, Ngn2 is co-expressed with Neurogenin 1 (Ngn1) in progenitor populations of the olfactory bulb, but unlike Ngn1, Ngn2 is not expressed in the olfactory epithelium. Instead, Ngn2 functions primarily within the bulb, where it specifies glutamatergic neuronal identity and orchestrates synaptic integration of olfactory inputs [

19,

24]. This division of labor between Ngn1 and Ngn2 highlights the transcriptional complexity of sensory development and suggests that manipulation of these factors may yield distinct outcomes depending on the targeted tissue [

16,

20].

Beyond its developmental roles, Ngn2 has been shown to influence regenerative capacity in sensory systems. In models of retinal injury, Ngn2 expression enhances neuronal survival, promotes axonal outgrowth, and supports synaptic reconnection [

13,

30,

33]. Similarly, in olfactory circuits, ectopic expression of Ngn2 facilitates neuronal integration and functional recovery, pointing to its potential utility in repairing sensory pathways disrupted by congenital or acquired damage [

32,

34,

37]. Importantly, these effects are not limited to lineage specification but extend to metabolic and antioxidant adaptations, as Ngn2-induced neurons demonstrate upregulation of Nrf2-related antioxidant genes, which may increase their resilience in oxidative environments such as the retina and cochlea [

5,

7,

9,

10,

23,

25].

Given that congenital blindness and deafness are characterized by both disrupted circuit formation and heightened oxidative vulnerability, Ngn2-directed astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming emerges as a particularly relevant therapeutic strategy. By simultaneously restoring lost neuronal populations and reinforcing antioxidant defenses, Ngn2 has the potential to address the dual challenges that define these conditions. The integration of developmental insights with reprogramming approaches strengthens the rationale for targeting Ngn2 in translational applications aimed at congenital sensory deficits [

12,

35,

36,

43,

47,

49].

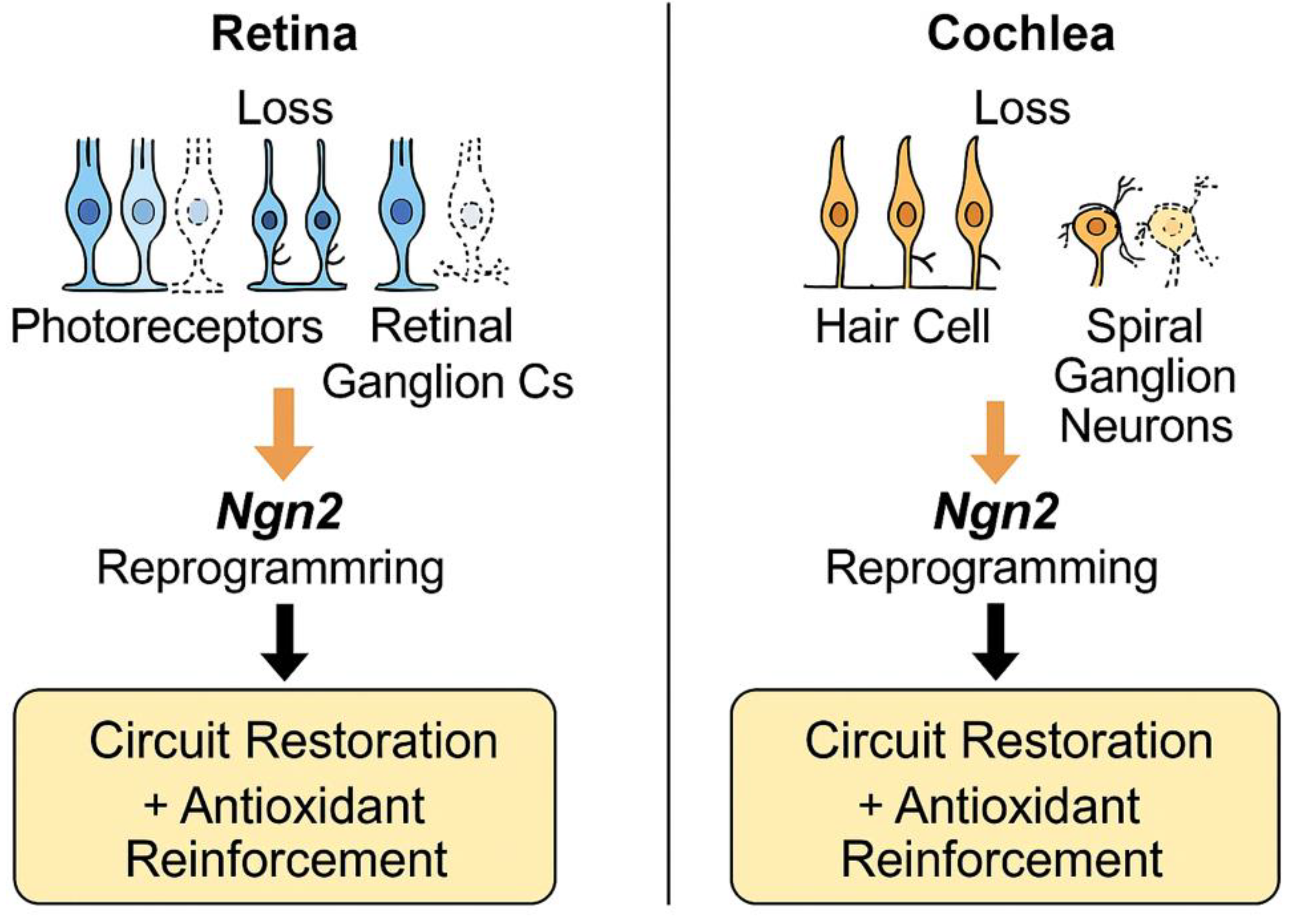

Figure 3.

Potential clinical applications of Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2)–mediated astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming in sensory systems. In the retina, Ngn2 promotes regeneration of photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells, while in the cochlea, Ngn2 facilitates replacement of hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons. Both processes contribute to circuit restoration and antioxidant reinforcement.

Figure 3.

Potential clinical applications of Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2)–mediated astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming in sensory systems. In the retina, Ngn2 promotes regeneration of photoreceptors and retinal ganglion cells, while in the cochlea, Ngn2 facilitates replacement of hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons. Both processes contribute to circuit restoration and antioxidant reinforcement.

4. Discussion

The evidence synthesized in this review positions astrocytes not merely as passive supporters of neuronal function but as central players in redox homeostasis and potential substrates for neuronal reprogramming. Their robust antioxidant systems—dominated by Nrf2-dependent transcriptional programs and glutathione metabolism—offer a level of resilience that neurons inherently lack. This biological distinction provides a compelling rationale for exploiting astrocytes as dual agents in therapeutic strategies: both as a reservoir of antioxidant protection and as a cellular source for neuronal replacement [

53].

The use of Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) as a reprogramming factor represents a major advance in regenerative neuroscience. Experimental models consistently demonstrate that Ngn2 enhances astrocyte-to-neuron conversion efficiency and promotes integration into host circuits, including those of the visual and auditory systems [

14,

15,

27]. Importantly, emerging findings suggest that Ngn2-driven reprogramming may preserve or even potentiate antioxidant defenses, thus offering a dual therapeutic effect: restoration of disrupted neuronal circuits and reinforcement of resistance against reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

54]. This duality is particularly relevant in congenital blindness and deafness, where oxidative stress not only accelerates neuronal degeneration but also diminishes the survival of transplanted or reprogrammed cells [

23,

25].

Nevertheless, several challenges must be critically acknowledged. First, the long-term stability and functionality of reprogrammed neurons remain incompletely understood [

55]. It is unclear whether antioxidant protection persists beyond early differentiation stages or if newly generated neurons eventually lose the redox resilience inherited from their astrocytic precursors. Second, most reprogramming studies have been conducted in rodent models, which may not fully recapitulate the complexity and heterogeneity of human central nervous system (CNS) tissue [

16,

20]. Translating these findings to humans requires validation in humanized models such as induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived organoids or ex vivo human astrocyte cultures [

56].

Third, the methods used to deliver transcription factors—primarily viral vectors—carry both technical and safety limitations. Although adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) provide a favorable safety profile and relatively efficient transduction, challenges such as restricted packaging capacity, variable regional tropism, and potential immune responses must be resolved before clinical application [

30,

33]. Non-viral strategies, including nanoparticles, exosome-mediated delivery, or CRISPR-based epigenetic editing, may represent safer and more versatile alternatives, though these approaches remain largely experimental [

57].

Another unresolved issue concerns the functional integration of reprogrammed neurons into host networks. While electrophysiological studies confirm synaptic activity and partial incorporation, it remains uncertain whether these neurons fully replicate the properties of endogenous cells, including their ability to withstand chronic oxidative insults [

32,

34]. An optimal therapeutic scenario may involve a hybrid strategy: maintaining aspects of astrocytic antioxidant capacity while conferring neuronal identity. Gene-editing technologies, combinatorial approaches (e.g., Ngn2 with Nrf2 activation), and pharmacological interventions with antioxidant compounds such as sulforaphane or resveratrol could help achieve this balance [

58].

Comparison with other proneural transcription factors further highlights the distinctive potential of Ngn2. Ascl1 and NeuroD1 have also been shown to induce neuronal reprogramming, but their efficiency and subtype specificity differ. For instance, Ascl1 promotes rapid but often incomplete neuronal conversion, while NeuroD1 supports cortical excitatory phenotypes but with lower efficiency [

47,

49]. Ngn2 appears particularly suited for sensory systems, given its developmental role in visual and olfactory circuits. However, combinatorial expression of proneural factors may outperform single-gene approaches, an avenue that warrants further investigation.

From a methodological perspective, optogenetic and chemogenetic tools provide valuable opportunities to probe the functional integration of reprogrammed neurons and their interaction with astrocytic signaling [

3,

18]. These techniques could help determine whether reprogrammed cells inherit astrocytic traits, such as enhanced antioxidant capacity or redox-sensitive signaling. Furthermore, integrating autophagy modulators with reprogramming protocols may improve mitochondrial quality control and reduce oxidative burden during neuronal conversion [

36,

41].

Finally, the therapeutic implications of this field extend beyond congenital blindness and deafness. The concept of astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming coupled with antioxidant reinforcement may be applicable to a wide spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), all of which share oxidative stress as a central pathogenic mechanism [

13,

43]. Future research should prioritize cross-species validation, longitudinal monitoring of reprogrammed neurons, and combinatorial strategies that integrate genetic, epigenetic, and pharmacological interventions to maximize both safety and efficacy [

52].

4.1. Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, most evidence on Ngn2-mediated astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming derives from rodent models, which may not fully represent the complexity of human astrocytic heterogeneity [

16,

20]. Second, the persistence of antioxidant protection in reprogrammed neurons remains uncertain, as long-term studies are scarce [

55]. Third, viral vectors, while effective, present safety concerns including immunogenicity and insertional mutagenesis, limiting direct clinical translation [

30]. Finally, the lack of standardized protocols for reprogramming across laboratories complicates reproducibility [

56]. Addressing these limitations will be essential for advancing the translational potential of this strategy.

5. Conclusion

Astrocytes, once regarded as mere supportive cells, are now recognized as central regulators of redox balance and critical partners in maintaining neuronal health. Their intrinsic antioxidant capacity, dominated by Nrf2-driven transcriptional programs and glutathione metabolism, positions them as uniquely suited to serve as substrates for neuronal reprogramming.

Evidence from experimental models demonstrates that Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) can efficiently convert astrocytes into functional neurons, while simultaneously engaging antioxidant pathways that reinforce cellular resilience against oxidative stress. This dual capacity—circuit reconstruction and redox reinforcement—represents a paradigm shift in regenerative neuroscience. In the context of congenital blindness and deafness, conditions defined by both disrupted neuronal circuits and heightened oxidative vulnerability, Ngn2-directed astrocytic reprogramming emerges as a particularly compelling therapeutic strategy.

Yet, challenges remain before this approach can be translated to the clinic. Key questions include the long-term stability of reprogrammed neurons, the persistence of antioxidant protection, the optimization of delivery systems, and the reproducibility of findings in human tissue. Addressing these gaps will require interdisciplinary strategies that combine molecular biology, bioengineering, and translational neuroscience.

Looking ahead, the integration of transcription factor–mediated reprogramming with pharmacological or genetic activation of antioxidant pathways may yield hybrid strategies capable of both restoring lost neuronal populations and fortifying them against oxidative stress. Such approaches hold promise not only for congenital sensory deficits but also for a broader range of neurodegenerative diseases where oxidative imbalance is a central driver of pathology.

In conclusion, Ngn2-driven astrocyte-to-neuron reprogramming represents a transformative therapeutic avenue at the intersection of regenerative medicine and redox biology. By uniting the goals of circuit restoration and antioxidant defense, this strategy opens a novel frontier in the pursuit of effective treatments for congenital and degenerative disorders of the nervous system.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editorial office of Antioxidants for the invitation to submit this article. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- McBean, G.J. Astrocyte antioxidant systems. Antioxidants. 2018, 7, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E. Multitarget effects of Nrf2 signalling in the brain. Antioxidants. 2024, 13, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.F.S. Developmental epigenetic Nrf2 repression weakens neuronal antioxidant defences. Nat Commun. 2015, 6, 8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boas, S.M. The NRF2-dependent transcriptional regulation of antioxidant defense in astrocytes versus neurons. Antioxidants. 2021, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.K. The role of astrocytes in the central nervous system focused on BK channel and heme oxygenase metabolites. Antioxidants. 2019, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizor, A.; et al. Astrocytic oxidative/nitrosative stress contributes to Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Antioxidants. 2019, 8, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Hewett, S.J. Nrf2 regulates basal glutathione production in astrocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiwaji, Z.; et al. Reactive astrocytes acquire neuroprotective as well as deleterious signatures via Nrf2 expression. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.T. Role of NRF2 in pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: cross talk with microglia. Antioxidants. 2024, 13, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, B. Nrf2/Wnt resilience orchestrates rejuvenation of glia–neuron dialogue in Parkinson’s disease. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S. Neuroprotection and disease modification by astrocytes. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, J.; et al. HOTAIRM1 regulates neuronal differentiation by modulating NEUROGENIN 2. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxidants. 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Zhu, T.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, L. Neurogenin 2 enhances the generation of patient-specific induced neuronal cells. Brain Res. 2015, 1615, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. GSK3 temporally regulates neurogenin 2 proneural activity in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2012, 32, 7791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, J.; et al. Heterogeneity of neurons reprogrammed from spinal cord astrocytes. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasel, P.; et al. Neurons and neuronal activity control gene expression in astrocytes. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 15132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moruno-Manchon, J.F.; et al. Sphingosine kinase 1–associated autophagy differs between neurons and astrocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, E.L.; et al. ngn1/neurogenin activates transcription of multiple terminal selector transcription factors in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda). 2020, 10, 1949–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsky, A.; Goshen, I. Astrocytes in memory function: pioneering findings. Neuroscience. 2018, 370, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Navarro, Á.; et al. Astrocytes and neurons share region-specific transcriptional signatures. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabe8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puñal, V.M.; et al. Large-scale death of retinal astrocytes. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxidants. 2023, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzos, A.A.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming in astrocytes distinguishes region-specific neuronal susceptibility in Huntington mice. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1258–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.R. Nrf2 activation in astrocytes protects against chronic neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2008, 28, 13574–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespuglio, R.; et al. Cerebral inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in Trypanosoma brucei–infected rats. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0215070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolós, M.; et al. Neurogenin 2 mediates amyloid-β precursor protein–stimulated neurogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2014, 289, 31253–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, F.E.; et al. Grafted human embryonic progenitors expressing neurogenin2… PLoS One. 2010, 5, e15914. [CrossRef]

- Söllvander, S.; et al. Accumulation of amyloid-β by astrocytes results in enlarged endosomes and microvesicle-induced apoptosis of neurons. Mol Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbad, C.; et al. Astrocyte senescence promotes glutamate toxicity in cortical neurons. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0227887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunemi, T.; et al. Astrocytes protect human dopaminergic neurons from α-synuclein accumulation. J Neurosci. 2020, 40, 8618–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.; et al. Hippocampus-based contextual memory alters morphological characteristics of astrocytes. Mol Brain. 2016, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; et al. Disruption of the astrocyte–neuron interaction in 5XFAD mice. Mol Brain. 2021, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, Z.; et al. Extensive astrocyte synchronization advances neuronal coupling in slow wave activity in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemsen, B.M.; Scofield, M.D. Quiet on the set! Astroglia star in silent synaptogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2021, 89, 328–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresto, N.; et al. Do astrocytes play a role in intellectual disabilities? Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 518–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, A.; Goshen, I. The memory orchestra: the role of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in cognitive processes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2021, 67, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasel, P.; et al. Activity-dependent modulation of synapse-regulating genes in astrocytes. Elife. 2021, 10, e70514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; et al. Transcriptomic profiling of microglia and astrocytes throughout aging. J Neuroinflammation. 2020, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B.R.; Yunes-Medina, L.; Johnson, G.V. Transglutaminase 2: Friend or foe? J Neurosci Res. 2018, 96, 1150–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.; et al. Reactive astrocytes acquire neuroprotective as well as deleterious signatures via Nrf2 expression. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambe, Y.; et al. PACAP for lactate production and secretion in astrocytes during fear memory. Pharmacol Rep. 2021, 73, 1109–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; et al. Modulation of activated astrocytes… Int J Cardiol. 2020, 308, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Adamsky, A.; et al. Astrocytic activation generates de novo network oscillations. Nat Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1228–38. [Google Scholar]

- Min, R.; Nevian, T. Astrocyte signaling controls spike timing–dependent depression at neocortical synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2012, 15, 746–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papouin, T.; et al. Astrocytic modulation of sleep slow waves. Science. 2017, 354, 812–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pataskar, A.; et al. NeuroD1 reprograms chromatin and transcription factor landscapes to induce the neuronal program. Cell Stem Cell. 2016, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; et al. Direct reprogramming of resident glial cells into neurons: harnessing endogenous repair mechanisms in the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2021, 22, 339–55. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, C.; et al. Directing astroglia from the cerebral cortex into subtype-specific functional neurons. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of the NRF2 and KEAP1 partnership in chronic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Nrf2 – a therapeutic target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015, 88, 253–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, S.; Masserdotti, G.; Russo, G.L.; Götz, M. Direct neuronal reprogramming: achievements, hurdles, and new roads to success. Cell Stem Cell. 2017, 21, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Kang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Z.; Meng, F.; et al. Reversing a model of Parkinson’s disease with in situ converted nigral neurons. Nature. 2020, 582, 550–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouchane, M.; Melo de Farias, A.R.; Moura, D.M.; Hilscher, M.M.; Schroeder, T.; Leão, R.N.; et al. Lineage reprogramming of astrocytes into interneurons in the injured adult mouse spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 1181. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Guan, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, Q.; et al. Direct generation of human neuronal cells from adult astrocytes by small molecules. Cell Stem Cell. 2017, 21, 732–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.K.; Knoblich, J.A. Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 571–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivetti di Val Cervo, P.; Romanov, R.A.; Spigolon, G.; Masini, D.; Martín-Montañez, E.; Toledo, E.M.; et al. Induction of functional dopamine neurons from human astrocytes in vitro and mouse astrocytes in a Parkinson’s disease model. Nat Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 444–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).