1. Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are cancerous conditions characterized by the abnormal proliferation of bone marrow and blood cells, affecting precursors of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets to varying extents. According to the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematopoietic neoplasms, MPNs are categorized into eight distinct disease types [

1].

They are typically differentiated from acute myeloid leukemia by having fewer than 20% myeloblasts in the blood and bone marrow. Additionally, MPNs are distinguished from other non-acute myeloid neoplasms by the absence of significant morphologic dysplasia and a pattern of hematopoiesis, evidenced by increased peripheral blood cell counts, splenomegaly, or both. This contrasts with the ineffective hematopoiesis (characterized by a cellular bone marrow but reduced peripheral blood cell counts) and dysplasia seen in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) [

2,

3].

Three primary MPN categories—polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF)—are variably associated with mutations in the Janus Kinase 2 (

Jak2) gene [

4].

Consequently, testing for

Jak2 mutations has become a standard component of evaluating patients with persistently elevated peripheral blood counts, organomegaly, unexplained thrombosis, or other symptoms indicative of MPN. Additionally, a smaller subset of disorders classified by the WHO under myeloproliferative/myelodysplastic neoplasms—conditions exhibiting overlapping features of both MPNs and myelodysplastic syndromes—also appear to be linked to

Jak2 mutations [

5].

Recent findings have shown that JAK2 V617F is associated with a specific haplotype, the germline GGCC (46/1) haplotype, especially in MPNs.

The

Jak2 46/1 haplotype, also known as the GGCC haplotype, is an inherited genetic variation within the

Jak2 gene locus that has become a focal point in research related to oncogenesis, particularly in MPNs and in associated drug resistance [

6].

This haplotype spans several polymorphisms within the

Jak2 gene and has been found to increase susceptibility to a variety of hematologic cancers, especially when linked with the somatic JAK2 V617F mutation, which results in the gain of function of the protein and the resulting alteration of the JAK/STAT pathway, which is essential for various cellular processes, particularly haematopoiesis. The “GGCC” part is characterised by four single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); it has been shown that the G allele of the rs10974944 single nucleotide polymorphism of this haplotype is correlated with MPNs progression to myelofibrosis (MF) and certain resistance-related clinical parameters [

7]. Identifying the 46/1 haplotype in patients may not only enhance risk stratification for

Jak2-driven cancers but also guide more effective, personalized therapeutic strategies to overcome resistance. Thus, the aim of this review is to describe current knowledge about the

Jak2 46/1 haplotype as a marker for diagnosis and the prediction of disease outcome.

2. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

MPNs are clonal blood diseases characterized by the overproduction of differentiated peripheral blood cells in the bone marrow, resulting in an increased risk of thrombosis, progression to medullary fibrosis, or secondary leukemic transformation [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In 1951, William Dameshek coined the term “myeloproliferative disorders”, which was later renamed by the World Health Organization (WHO) “myeloproliferative neoplasms” [

1].

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), produced in bone marrow, are immature cells with the ability to self-renew and differentiate in all mature blood cell types.

These cells can take two distinct paths at the progenitor stage, becoming myeloid or lymphoid stem cells. The first gives rise to T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells, while the second to megakaryocytes, erythrocytes, granulocytes, or macrophages [

14]. The bone marrow environment, growth factors, and transcription factors are essential for a normal hematopoietic process. In MPNs an abnormal proliferation of one or more terminal myeloid cell lines in the peripheral blood gives rise to the pathology. In particular, PV, ET, and PMF are the classic MPNs. The myeloid lineage overproduces granulocytes, platelets, and erythrocytes [

15]. This classification of MPNs is based on changes in blood cell counts and hematopoietic lineages in the bone marrow, which exhibit hyperplasia (an increase in the number of cells) and dysplasia (an abnormal development or growth of cells) [

16].

PV is characterized by erythrocytosis, with morphologically normal cells. Patients with PV have higher thrombotic and haemorrhagic predisposition; moreover, there are cumulative risks of the evolution of the pathology into leukaemia or risk for fibrotic progression [

17].

The primary characteristics of ET are thrombocytosis in the peripheral blood and an increase in the number of mature megakaryocytes, the precursor cells of platelets, in the bone marrow. Thrombotic events account for more than 20% of the complications associated with ET, representing a major risk of this pathology. The aim of treatments available nowadays is to minimize the risk of thrombosis and/or bleeding [

18].

Otherwise, MF refers to the formation of fibrosis in the bone marrow. MF can also derive from PV or ET [

16]. The most characteristic features include bone marrow fibrosis (reticulin/collagen), aberrant inflammation with cytokine overexpression, anemia (resulting from ineffective erythropoiesis), hepatosplenomegaly, extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH), constitutional symptoms (such as fatigue, night sweats, and fever), cachexia, leukemic progression, and shortened survival [

19]. Approximately 20% of patients with PMF develop leukemia. Many others die from co-existing conditions, including cardiovascular complications and cytopenia-related issues like infections or bleeding [

20,

21,

22].

Mutations in three key genes primarily drive these conditions:

Jak2, calreticulin (

Calr), and myeloproliferative leukemia oncogene (

Mpl). These mutations abnormally stimulate hematopoietic cell activity, leading to increased cellular proliferation and growth, which regrettably contributes to the progression of MF [

16]. Therefore, one of these mutations is often associated with the pathology. For example, the

Jak2 mutation is found in approximately 90% of patients, making it a strong diagnostic indicator [

19].

3. Role and Regulatory Mechanism of Wild Type JAK2

The

Jak2 gene is located on chromosome 9p24.1 that encodes a non-receptor tyrosine kinase. The

Jak2 gene comprises 142,939 base pairs (bp) and contain the following components: a promoter region, 25 exons, 25 introns, and a terminator region. Alternative splicing produces three isoforms of the JAK2 protein, generating seven transcripts ranging from 6900 to 7000 bp [

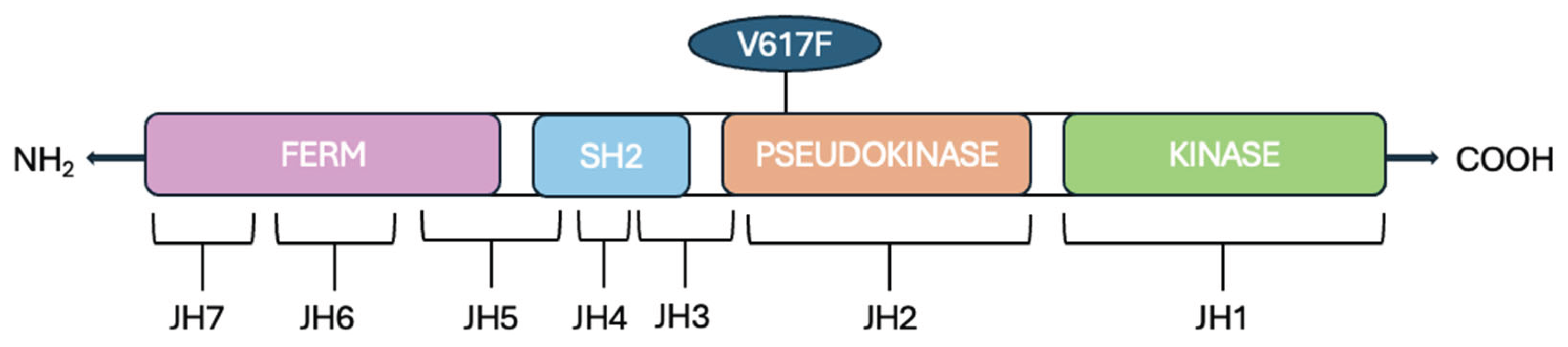

12]. In mammals, there are four members of the JAKs protein family: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. JAKs proteins are composed of an N-terminal FERM (four-point-one, ezrin, radixin, moesin) domain, an Src homology 2 (SH2) domain, a kinase-like pseudokinase domain (JH2) and a C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain JH1 (

Figure 1).

The FERM domain is composed of JAK homology (JH) domains JH5, JH6, and JH7; this domain binds noncovalently to the juxtamembrane sequence of the cytokine receptor, which includes two segments [

23,

24], Box1 and Box2, respectively characterized by proline-rich sequences and a hydrophobic segment. Moreover, this domain is involved in the intracellular regulation of the JAK activity.

The SH2 domain lacks phosphotyrosine binding activity. The name of the tyrosine kinase derives from the two kinase domains JH1 and JH2 because it refers to the double face of the Roman god Janus, a god of transitions or doorways. The first domain (JH1) encodes a tyrosine kinase (TK), while the second one (JH2) works as a pseudokinase (PK) because it lacks many of the conserved residues that are essential for phosphotransferase activity.

4. JAK/STAT Pathway and V617F Mutation Involvement in MPN

JAK proteins are involved in the JAK/STAT pathway, an important signalling pathway downstream of cytokine receptors [

25]. Cytokines are involved in numerous hematopoietic and immune functions, making this pathway essential for various cellular processes, particularly hematopoiesis [

26,

27]. Many different cytokines can activate the same JAK, which can be associated with multiple cytokine receptors, and in some cases, cytokine stimulation can enhance this association [

25].

For instance, JAK2 associates with many homodimeric receptors, such as the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR), thrombopoietin receptor (TpoR/MPL), the growth hormone receptor (GHR), and the heterodimeric receptors, including the GM-CSF (Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor) and interleukin-3 receptors (IL-3R), which share a common beta subunit (βc) [

28].

Jak2 is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells and is critical for hematopoiesis, like

Jak3, which is especially expressed in lymphoid lineage cells [

27]. Instead,

Tyk2 is also detected in non-hematopoietic tissues, including the liver, lung, and intestine, where it participates in immune and inflammatory responses.

JAK2 plays a critical role in the JAK/STAT pathway [

10], where the binding of the hormone, interferons (IFNs), interleukins (ILs), colony-stimulating factors, cytokines, and growth factors leads to receptor dimerization.

Ligand’s binding activates the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor and the phosphorylation of JAK2 themselves. It induces receptor rearrangement that allows the transphosphorylation of the activation loop located on the JH1 domain, causing JAK2 activation [

29]. There are approximately 20 residues of tyrosine involved in this phosphorylation, which originates from cytokine activation [

30].

The activation loop is the part in which the major autophosphorylation of the JAK protein, a prerequisite for catalytic activation, occurs. This site includes all JAK tandem tyrosine residues; for instance, in JAK2, there are Tyr

1007 and Tyr

1008 [

31]. Moreover, other Tyr residues phosphorylated could enhance or downregulate JAK2 activity. The activation mechanism by Tyr

1007- Tyr

1008 phosphorylation is not yet fully understood in all cases; for instance, it has been demonstrated that phosphorylation of Tyr

119 in the FERM domain of JAK2 regulates its association with the Epo receptor [

32]. Otherwise, in the absence of cytokine activation, JAK2 is phosphorylated on Ser

523, which negatively controls JAK2 activity [

33].

After activation, the docking site becomes available and can attach signalling proteins, such as STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription). Two STAT proteins, phosphorylated on a conserved tyrosine residue at the C terminus, dimerize, dissociate from the receptor, and go to the nucleus, where they regulate gene expression; in fact, they bind DNA and activate the transcription of the target gene. Their binding site is typically located in specific regions, such as the enhancer, promoter region, or first intron of the target gene.

Considering that JAK/STAT pathway is fundamental in hematopoiesis [

26], its alteration leads to many blood diseases. A genetic polymorphism of

Jak2, the mutation V617F, has been associated with MPNs [

13]. It occurs in nearly 95% of patients with PV, and in 50-60% of patients with ET and PMF [

26].

JAK2 V617F is a somatic mutation, not present in the germline DNA of patients, acquired in the hematopoietic compartment, and characteristic of hematopoietic cells [

10]. This mutation consists of the substitution of valine for phenylalanine at codon 617 of JAK2, resulting in a gain-of-function effect for this gene [

10,

12].

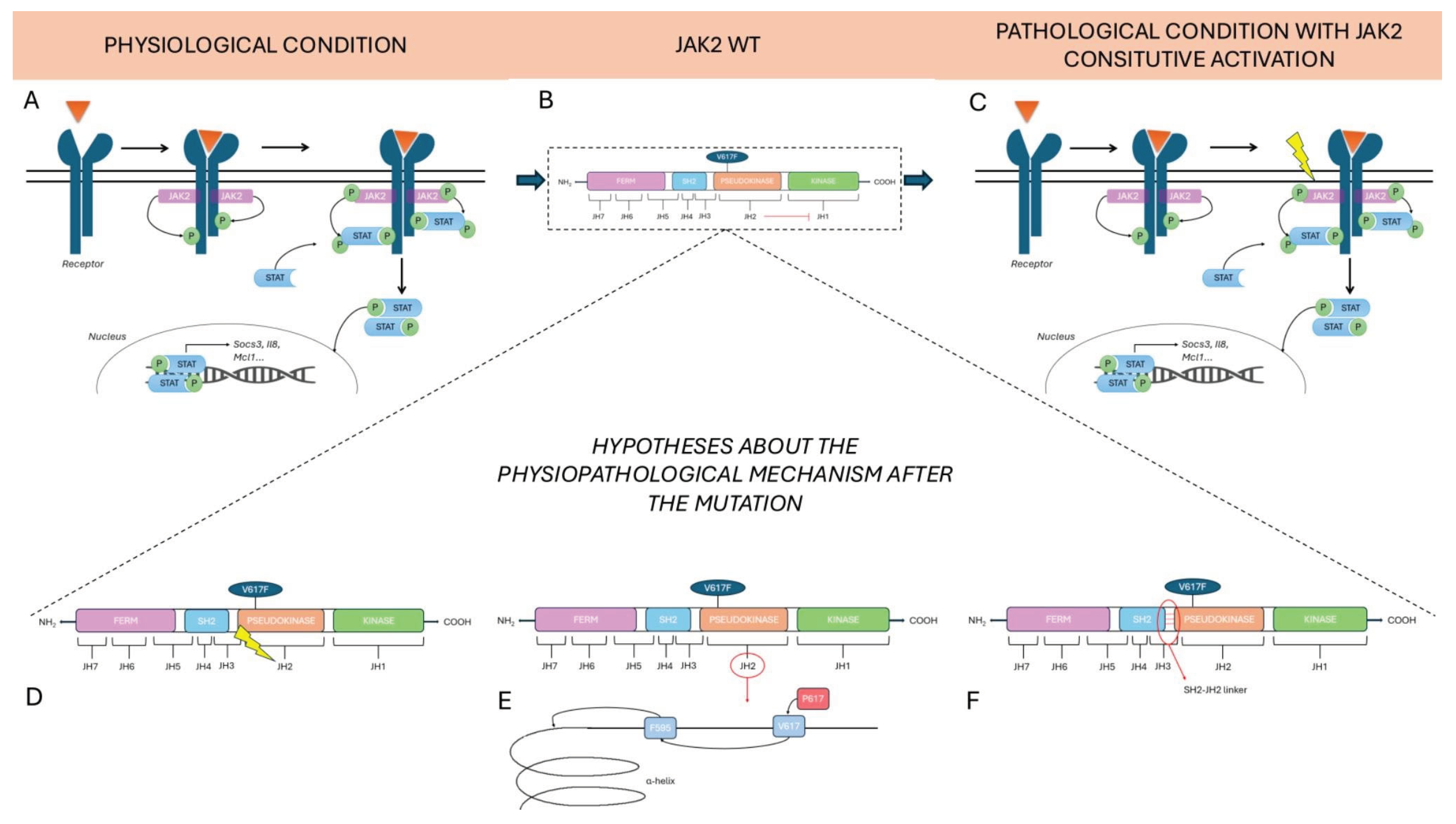

There are three main hypotheses about the physiopathological mechanism after the mutation.

The first current of thought states that constitutive activation of the pseudokinase (JH2) domain drives to loss of inhibitory function that this dominion exercises over the active (JH1) kinase domain. The roles of the JH2 domain, in fact, are to maintain a low basal activity of JAK when there are no cytokines and to facilitate JAK activation upon binding to the receptor when cytokines are present [

34].

The second hypothesis concerns the possibility that changes in JH2 conformation are responsible for kinase domain activation. The V617 mutation, which is mutated to Phe, could influence the neighbouring F595, a residue positioned in the αC helix of JH2, in a specific manner. The specific conformation of the αC helix is fundamental for kinase domain activation [

35].

The last hypothesis focuses on the direct activation of the JH1 domain via an SH2-JH2 linker [

36]. V617F is one of three mutations known to be concentrated in 3 regions of JH2; V617F is encoded by exon 14 and it is present in the majority of MPNs, while mutation on the exon 16 is associated with B-cell leukemia and in 4% of PV cases it has been found a mutation in the linker between SH2 and JH2 domain, encoded by exon 12 [

34]. These findings demonstrate the importance of the JH2 domain in regulating this pathway.

In any case, the outcome of each of these hypotheses is the same: after the constitutional activation of JAK2, subsequent downstream activation of STAT occurs (

Figure 2).

Otherwise, STAT proteins are signal transducers and activators of transcription. STAT family includes seven members: STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, and STAT6. Their primary function is as transcription factors, so when they enter the nucleus, they regulate the expression of cytokine-responsive genes [

37].

Mainly STAT3 and STAT5 are activated upon the mutation of JAK2 [

38]. For instance, constitutive activation of STAT5 has been associated with leukemic transformation [

39]. Moreover, high levels of STAT5 and STAT3 phosphorylation have been observed in PV patients, while in ET patients, STAT3 is highly phosphorylated, whereas STAT5 exhibits decreased phosphorylation levels. Ultimately, in PMF patients, both STAT3 and STAT5 exhibit low phosphorylation levels. Thus, in this cascade, a specific cytokine activates a specific JAK, which in turn activates a specific STAT. Therefore, some proteins dampen cytokine signalling at the different levels of this pathway. For instance, the SOCS (Suppressors Of Cytokine Signalling) family inhibits this cascade through negative feedback [

40]. For example, SOCS1-7 and the cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CIS) act by recruiting ubiquitin ligases (E3) to target JAK2 for degradation, whereas SOCS3 directly inhibits JAK2’s kinase activity via complex formation [

5].

Thus, when V617F mutation is present, hematopoietic cells undergo transformation into cytokine-independent growth. Therefore, processes like tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and the resulting inflammation are promoted [

12,

41].

So, this paragraph demonstrated the importance of the JAK/STAT pathway dysregulation in hematological malignancy and the JAK2 V617F mutation role in cancer susceptibility. Recent findings have shown that JAK2 V617F is associated with this specific haplotype, the germline GGCC (46/1) haplotype, especially in MPNs [

12,

41].

5. Jak2 GGCC 46/1 Haplotype Discovery and Pathophysiology

Haplotype 46/1 was first discovered by Jones et al. [

6] in their study, 142 patients identified as having a homozygous V617F mutation were found to share an identical haplotype in approximately 77% of cases, or 109 patients. A haplotype is a group of genetic variations present on the same chromosome. These variants are not easily separable by recombination and tend to be inherited together as a unit. They are in linkage disequilibrium, which is proof of a shared ancestry of the chromosomes.

These results indicate that the homozygous V617F mutation is not random, in fact it occurs on a specific

Jak2 haplotype. This haplotype is present in approximately 45% of the general population [

42], and other studies have confirmed its association with the V617F mutation [

12,

41].

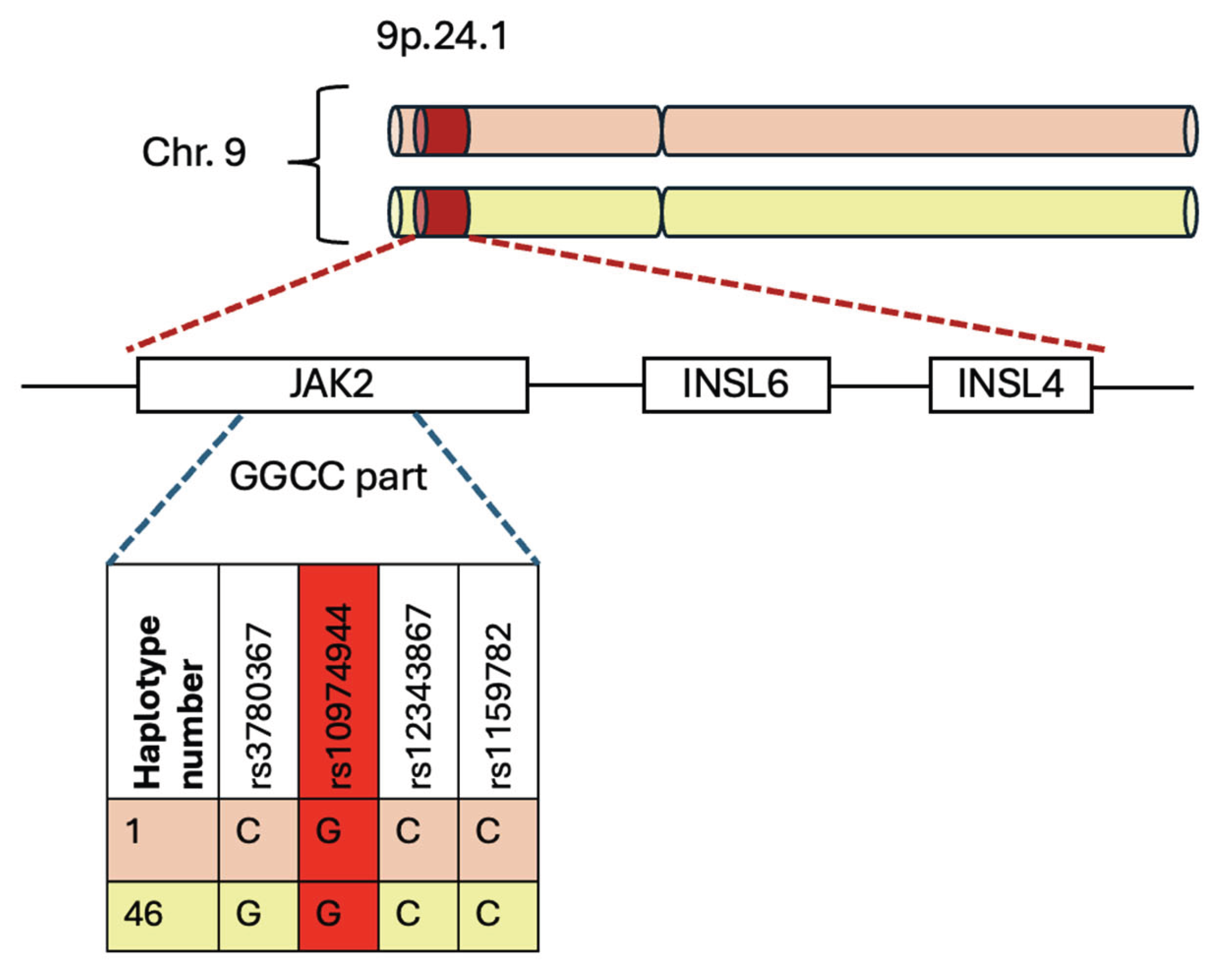

The 46/1 haplotype includes a segment called “GGCC” that encompasses the most frequently mutated

Jak2 exons: exon 14 (mainly the V617F mutation), exon 12 (mutations and deletions), and, to a lesser extent, exons 13 and 15 [

42].

This haplotype includes a set of genetic variations that map a region of 250–280 kb and are distributed along chromosome 9p.24.1, which covers the

Jak2,

Insl6, and

Insl4 genes [

12,

41,

43]. The last two genes are generally not transcribed in the hematopoietic system [

44].

The differences in the considered region are contained in sites of single-base genetic alterations known as single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), which contribute to interindividual and heritable differences in complex phenotypes [

22].

The “GGCC” part encompasses the region between intron 10 and intron 15 of the

Jak2 gene, characterized by four single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): rs3780367 in intron 10, rs10974944 in intron 12, rs12343867 in intron 14, and rs1159782 in intron 15. All these SNPs are in complete linkage disequilibrium, which means they are inherited together. “GGCC” part is called this way not because it is reached in GC sequences, but because it contains four single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and they replace three thymidines (T) and one cytosine (C) with two guanosines (G) and two cytosines, creating the pattern called “GGCC” (

Figure 3) [

42].

A novel hypothesis associates the GGCC haplotype with dysregulation in inflammatory and myelomonocytic responses, possibly due to the increased expression of the other two genes covered by the haplotype, Insl6 and Insl4. They increase their expression in the medullary stromal cells, where they are produced; consequently, these cells produce excessive amounts of proinflammatory cytokines.

In addition to inflammation, other events such as splenomegaly and splanchnic vein thrombosis have been associated with 46/1 [

12,

41].

Another influence of the haplotype is exercised on the expression of

Insl6 and

Insl4 in medullary stromal cells, causing proinflammatory and promyeloid activity of cytokines. This mechanism facilitates the survival of the mutated clone [

45].

Interestingly, several individuals in an Australian family with familial MPN, identified with germline Retinoblastoma-binding protein 6 (

Rbbp6) variants, also carried the

Jak2 46/1 haplotype [

46]. This suggests these germline predisposing variants may act additively or synergistically to promote MPN development. It means that the presence of each variant independently contributes to the overall risk of developing MPN or that their combined effect is greater than the sum of their individual effects.

Jak2 expression appears to be unaffected by the 46/1 haplotype [

6,

47]. There are two hypotheses explaining the mechanism by which the

Jak2 46/1 haplotype influences the development of MPNs. The “hypermutability” hypothesis suggests that the

Jak2 46/1 haplotype makes the genetic region in which it is located more genetically unstable and more susceptible to replication errors and genetic damage [

11,

48,

49]. The “fertile soil” hypothesis postulates that hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) carrying the 46/1 haplotype have a selective advantage. This means that these cells might proliferate or survive better than other HSCs, creating a more “fertile” environment for the development of mutations and subsequent clonal expansion [

43].

It is important to note that these two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and could both contribute to the risk of MPNs.

The frequency of the

Jak2 haplotype GGCC_46/1 in the healthy population is approximately 24%, whereas in patients with the JAK2 V617F mutation, it is found in 40–80% of cases [

50]. So,

Jak2 haplotype GGCC_46/1 is preferentially associated with JAK2 V617F mutation, but not exclusively [

43]. This haplotype accounts for approximately 28% of the population-attributable risk of developing an MPN [

6].

This haplotype precedes the acquisition of the JAK2 V617F variant and has also been identified as one of the factors that increases the risk of familial MPNs by more than five times [

12,

41].

Remarkably, the “GGCC” haplotype is tagged by rs10974944, a SNP in which a cytosine is replaced with a guanosine. Therefore, the C allele is the common allele, whereas the G allele represents the variant that confers risk for MPNs. At the same time, the heterozygous condition is C/G.

rs10974944 has been long studied in populations from Brazil, Japan, and China.What has become evident is that this is strongly associated with JAK2 V617F-positive MPN patients compared to controls [

51].

This association has been demonstrated in a study carried out by Kilpivaara, which identified the rs10974944 variant (C/G) in the

Jak2 gene, revealing that it can predispose to JAK2 V617F-positive MPNs. Moreover, his studies demonstrated that the rs10974944 (G) allele may predispose to the acquisition of the JAK2 V617F somatic variant on the same strand [

52].

In addition, the C-allele is associated with ET [

53]. At the same time, other studies have demonstrated a prevalence of the heterozygous haplotype CG in patients with PMF and PV [

54].

That is why the JAK2 46/1 haplotype in patients with MPNs could become a potential biomarker for the early diagnosis of the pathology.

6. Jak2 Haplotype 46/1 and Onco-Drug Resistance Onset

6.1. MPN Treatments and Therapies

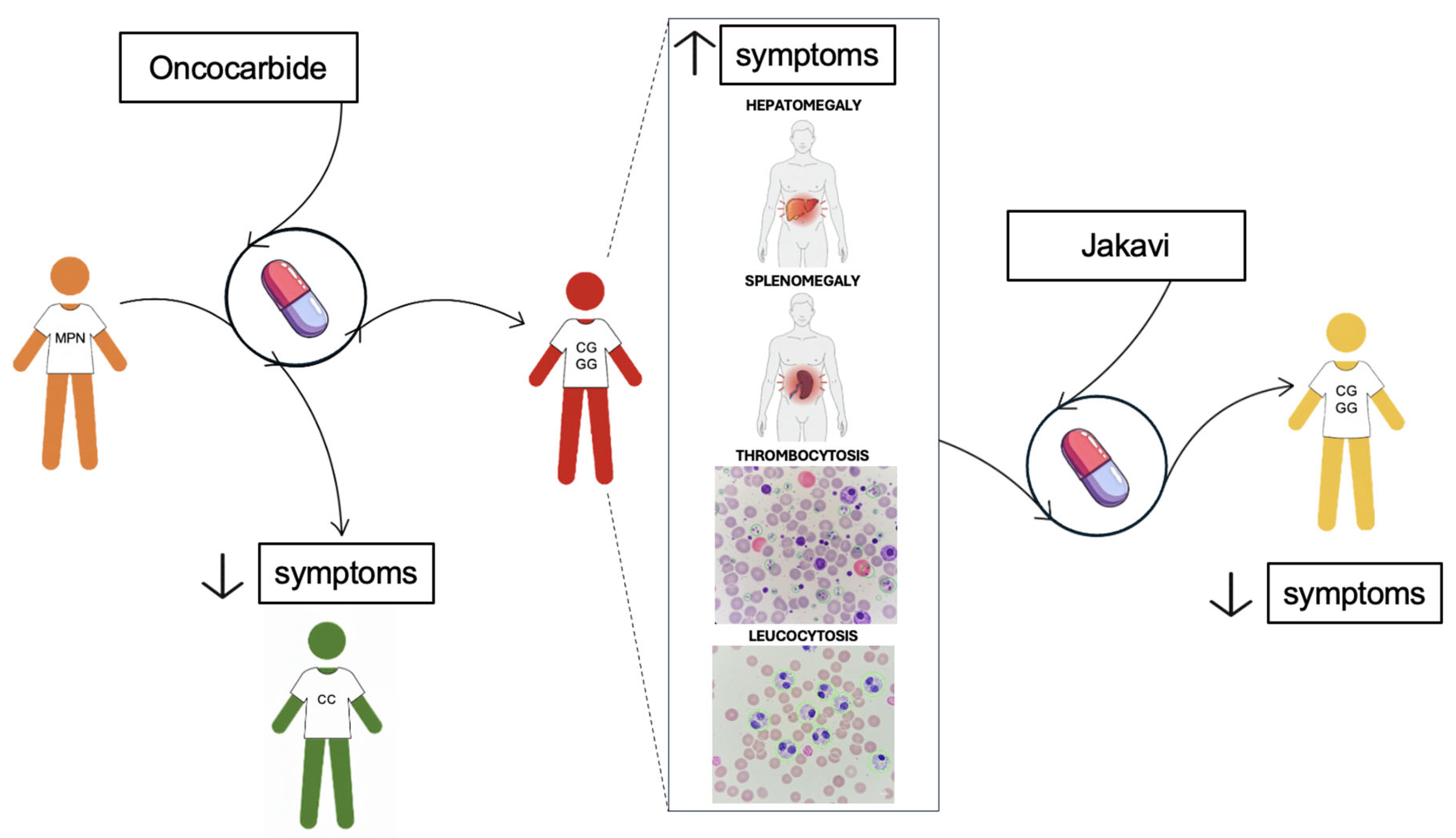

MPNs are generally an indolent pathology. The treatments aim to prevent complications. Therapies used in treatment include cytoreductive therapy, which utilizes Oncocarbide, also known as hydroxyurea (ATC: L01XX05). Following the National Cancer Institute definition, hydroxyurea is an antimetabolite that inhibits DNA synthesis and may kill cancer cells, but it may also make them easier to kill with radiation therapy (National Cancer Institute). So, it is a cytostatic agent that acts like an anti-cancer drug. It is a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor that does not interfere with RNA or protein synthesis [

55].

In the last years, many advancements in MPN treatment have been made, largely thanks to the discovery that different cytokines trigger the same response, acting on the same receptor subunit or the same intracellular signalling mediator, and thanks to the finding of some molecules able to cross the cell membrane and to reach their target specifically. These advancements led to the discovery of JAK selective inhibitors [

56].

Different types of drugs have been investigated, and some problems have emerged: the V617F mutation has been found outside the ATP-binding pocket of JAK2, so the JAK inhibitor that targets this ATP-binding pocket can block both the mutated form of the protein and the wild-type one. This process could affect the treatment, resulting in myelosuppressive adverse events post-therapy.

One of the most used drugs is Jakavi, a selective inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2 [

57]. This type of drug acts on the JAK-STAT pathway, reducing the phosphorylation and leading to reduced cellular proliferation and induction of apoptosis [

58].

Jakavi (ruxolitinib) is particularly indicated for the treatment of splenomegaly and other symptoms in adults with PMF, or MF that develops after PV or ET [

59]. Otherwise, Fedratinib (TG101348) is a selective JAK2 inhibitor that can induce apoptosis in cell lines with the V617F mutation [

60,

61]. They are both “type I” inhibitors, which means that they bind and stabilize the kinase-active conformation of JAK2. In contrast, “type II” ATP-competitive inhibitors do the same but with the inactive conformation of the protein [

62].

Regarding PV, hydroxyurea (Oncocarbide) is the first-line treatment for high-risk patients [

63]. For low-risk patients, it is used if blood counts increase, symptoms are severe, or there is splenomegaly or intolerance to phlebotomy [

64]. If hematocrit exceeds 45%, therapy switches to ruxolitinib (Jakavi), which is crucial for controlling hematocrit and reducing splenomegaly [

65].

Oncocarbide is also used with patients affected by ET as first-line treatment. In this case, the cytoreductive therapy is changed to Jakavi if the hematocrit level increases or patients show leucocytosis or thrombocytosis.

For low-risk ET patients (those who are younger, have no other risk factors, and do not have extreme thrombocytosis), treatment may involve low-dose aspirin or simply observation [

66]. Extreme thrombocytosis (platelet count> 1×10^6/L) is a concern due to increased bleeding risks [

64]. High-risk patients typically receive cytoreductive therapy, with hydroxyurea as the first-line treatment. If patients develop resistance or intolerance to hydroxyurea, anagrelide, or ruxolitinib (Jakavi) may be used as an alternative. In any case, rigorous control of cardiovascular risk factors is recommended for all patients [

66]. At least, in ET, doctors can prescribe up to a maximum of 1,5-2 g of Oncocarbide per day to decrease platelet levels. If the level increases, therapy must be changed. Splenomegaly is another parameter considered. If the spleen dimension increases in patients who undergo treatment with Oncocarbide, it could be a sign of drug resistance.

For MF patients, hydroxyurea is the first-line treatment, effectively halving splenomegaly in about 40% of cases, with benefits lasting roughly one year [

67]. Myelosuppression and painful mucocutaneous ulcers are common side effects. If patients become refractory to hydroxyurea (e.g., hematocrit above 45%) [

68] or experience symptomatic splenomegaly, treatment should switch to ruxolitinib [

57] (

Figure 4).

So, although many patients with MF have shown some improvement in the signs and symptoms after treatment with ruxolitinib, others are refractory to ruxolitinib, and a lot of them lose their response over time. At least, a possible prolongation of patients’ survival has been observed in other cases [

69].

6.2. Challenges and Drug resistance in MPNs

The two considerable situations to evaluate for changing therapy are drug resistance and drug intolerance. The first manifests as splenomegaly, leucocytosis, thrombocytosis, or persistent anemia; hematological clinical signs, such as anemia, or extra-hematological clinical signs, including non-melanoma skin cancers, characterize the second.

Drug resistance in JAK2-associated cancers, particularly to JAK inhibitors like ruxolitinib, is a significant challenge in treating MPNs. The 46/1 haplotype has been implicated in influencing responses to these drugs, as well as the development of resistance, and various mechanisms have been hypothesized.

The first hypothesis concerns an enhanced activation of signalling pathways. It has been demonstrated that if the haplotype enhances the V617F mutation, this alteration may lead to more robust activation of downstream signalling pathways, such as JAK-STAT. However, it can also increase MAPK activity, which plays a key role in promoting cell growth and survival. In this signalling network, MAPK activation, induced by JAK2-V617F, is, to some extent, also dependent on PI3K. Thus, because the resilience of the JAK2 and PI3K pathways may reduce the efficacy of JAK inhibitors, these pathways could be a potential therapeutic target for controlling abnormal cell growth in JAK2-V617F-positive diseases, potentially with alternative or combinatorial approaches [

70].

Another hypothesis concerns the altered epigenetic landscape, as it has been confirmed that the V617F mutation induces epigenetic deregulation [

71]. Epigenetic remodelling is essential in hematopoietic cells because it ensures their steady state, defined as the equilibrium between self-renewal and proliferative gene expression programs, thereby guaranteeing the appropriate cell fate determination. Reversible modifications to chromatin structure, DNA methylation, and histone modifications are all epigenetic changes that influence gene transcription profiles [

72].

In any case, substantial evidence suggests that the resistance to the JAK inhibitor may be a consequence of the reactivation of the JAK/STAT pathway through the heterodimerization of activated JAK2 and JAK1, or TYK2. This mechanism results in the activation of JAK2 in trans by other JAK kinases, increased JAK2 mRNA expression (which promotes the formation of heterodimers), and the ultimately resistance to JAK2 inhibitor–induced apoptosis. In these studies, the cessation of therapy with a JAK2 inhibitor results in new sensitization of the resistant clone positive for the V617F mutation, leading to the conclusion that after a period of treatment interruption, patients resistant to JAK2 inhibitors may respond to retreatment with the same JAK2 inhibitor or with others [

71].

Moreover, it has been demonstrated that JAK inhibition leads to alterations in the histone landscape, resulting in an increase in methylation and acetylation [

73].

Alteration of the methylation landscape has been suggested to play a key role in the pathogenesis and leukemic transformation of MPNs [

74].

Several studies have suggested that the haplotype is associated with an increase in the expression of specific genes, including

Jak2,

Insl6, and

Insl4. Therefore, this process results in DNA recombination, with the emergence of genetic variations or abnormal methylation of the promoter region too [

12].

For instance, DNA recombination could be stimulated by unidentified intronic repeating DNA sequences in the 46/1 haplotype, which could, in turn, cause the overexpression of the

Jak2 gene located on the recombined allele. The activation of

Jak2 determines the transmission of signals derived from all the cytokines involved in myelopoiesis, resulting in the chronically excessive stimulation of this process. In conclusion, the excessive stimulation of mitosis in myeloid progenitors makes them more prone to making mistakes during replication, creating altered genes, such as

Jak2 [

42].

Additionally, the haplotype is expected to enhance cytokine production by bone marrow stromal cells through the overexpression of

Insl4 and

Insl6. This process may contribute to activating the constitutive JAK/STAT pathway, through the V617F mutation [

42,

44,

75].

To conclude, the 46/1 haplotype might affect gene expression patterns and methylation status in hematopoietic stem cells, promoting a survival advantage. This epigenetic advantage enables cells to bypass JAK inhibition, allowing them to adapt to the selective pressure exerted by JAK-targeted therapies.

The last hypothesis regarding how the 46/1 haplotype influences responses to these drugs and resistance development concerns the susceptibility of cells harbouring the 46/1 haplotype to acquire additional mutations more readily in response to therapy, giving rise to drug-resistant clones. This is particularly problematic in MPNs, where clonal evolution is a known contributor to disease progression and treatment resistance.

JAK2 V617F allele burden, or variant allele fraction (VAF), refers to the percentage of hematopoietic cells that carry this mutation. In this case, low clonal JAK2 V617F load is associated with a clonal hematopoiesis phenotype of indeterminate potential or ET, whereas high clonal load is associated with PV or post-PV myelofibrosis (MFP). High clonal loads of JAK2 V617F are associated with increased leukocyte counts, risk of myelofibrotic transformation, and risk of splenomegaly. Thus, this study demonstrates that hematopoietic cells with the JAK2 V617F mutation (commonly associated with the 46/1 haplotype) exhibit enhanced clonal evolution, which can drive disease progression and resistance to therapy. This evolution is a hallmark of MPNs, particularly in conditions such as MF [

76]. Moreover, while direct evidence linking the 46/1 haplotype to drug resistance is limited, it has been associated with clinical markers of resistance and disease transformation, such as progression to MF. In one study, the G/G allele was observed in patients with resistance-related parameters (p = 0.002449) [

7]. Interestingly, JAK2 mutations are most acquired in cis with the JAK2 predisposition haplotype, as demonstrated by many studies [

6,

11,

52]. Furthermore, the 46/1 haplotype has been hypothesized to be associated with greater genomic instability, making cells more susceptible to accumulating additional mutations [

12].

The unique role of the 46/1 haplotype in fostering mutation acquisition and drug resistance in JAK2-driven cancers suggests that it could be a predictive biomarker for susceptibility to certain cancers and responses to JAK2 inhibitors. Identifying patients with the 46/1 haplotype might allow for more personalized treatment strategies, such as using combination therapies. For instance, therapies combining JAK inhibitors with PI3K inhibitors have been evaluated, as mentioned earlier before [

70].

Another possibility is to target both the JAK/STAT and BET pathways to improve response rates. The BET family comprises four proteins, BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT, which are a group of transcriptional co-regulators. They can recognize acetylated lysines in histones. The BET inhibitors prevent them from binding these acetylated residues. BET proteins and JAK2 signalling can converge on the same transcriptional regulatory system, a key point in controlling the expression of specific genes, such as LMO2, which is expressed in progenitor cells from PV patients. It has been discovered that the combined action of two inhibitors may prevent the rise of JAK inhibitor-resistant clones. For instance, I-BET151 is effective against PV as the compound specifically targets homozygous JAK2 V617F cells. In polycythemia, both JAK and BET inhibitors may overcome the problem of the first one, which do not induce a consistent reduction in the burden of JAK2 V617F-positive progenitor cells [

57,

77], and may increase the possibility of targeting the neoplastic cells while simultaneously reducing the risk of adverse side effects.

In addition, Carreño-Tarragona et al. [

78] have demonstrated another possible mechanism through which haplotype 46/1 can increase the risk of developing MPNs. The gene that encodes CD274/programmed death-1 receptor ligand (PD-L1) is also located at 9p24.1 and has a physical interaction with JAK2. It is overexpressed in MPN patients with the V617F mutation [

79], and the degree of PD-L1 expression in CD34+ cells has been linked to JAK2 V617F mutational burden [

80,

81]. Thus, they have proven that haplotype 46/1 influences PD-L1 expression levels through a hypoxia-mediated mechanism, whereby PD-L1 interacts with transcriptional regulatory elements within the

Jak2 locus [

78].

The Jak2 46/1 haplotype is a significant factor in both the development and therapeutic resistance of JAK2-associated hematologic cancers. Its association with the JAK2 V617F mutation highlights its role in cancer susceptibility, while its impact on signalling pathways and the epigenetic landscape of cells contributes to the development of drug resistance. Identifying the 46/1 haplotype in patients may not only enhance risk stratification for JAK2-driven cancers but also guide more effective, personalized therapeutic strategies to overcome resistance. Further research into its exact mechanisms may reveal additional targets for intervention, offering new hope for treating resistant hematologic malignancies.

7. Jak2 Haplotype 46/1 and Risk Stratification

A recent study has revealed that the 46/1 haplotype, specifically the G allele of the rs10974944 SNP, appears to be associated with most symptoms related to the onset of onco-drug resistance. These clinical parameters include splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, thrombocytosis, and leucocytosis. In fact, the rs10974944 G allele, a tag for the JAK2 46/1 haplotype, has been shown to be significantly more prevalent in JAK2 V617F-positive patients, suggesting a germline predisposition that influences disease phenotype and clinical progression [

52]. A Brazilian study found that MPN patients carrying the G allele exhibited higher hematocrit, hemoglobin, and platelet levels compared to non-carriers, correlating with clinical manifestations like splenomegaly and thrombocytosis [

82].

In contrast, in C/G patients, a prevalence has only been found for hepatomegaly, suggesting a more limited role of this genotype in the full spectrum of resistance-associated features. Supporting this, a recent cohort study of drug-resistant MPN patients from Southern Italy found the C/G genotype in ~58% of resistant individuals, often displaying hepatomegaly, thrombocytosis, and leucocytosis, while the G/G genotype was underrepresented (~6%) and not significantly associated with resistance outcomes [

7].

Thus, although no direct correlation between the GGCC_46/1 haplotype in G/G homozygosity and onco-drug resistance outcome has been statistically confirmed, the presence of the G/G genotype appears to be related to a clinical profile (e.g., splenomegaly and high blood cell counts) that could potentially favour the development of resistance-related conditions, possibly through chronic inflammation and clonal evolution mechanisms (

Figure 4).

More interestingly, this haplotype — specifically the G allele of rs10974944 — has also been associated with an increased risk of progression to myelofibrosis (MF), a more severe MPN phenotype. Several studies indicate that 46/1 carriers are more likely to harbour not only JAK2 mutations but also MPL or CALR mutations, increasing the risk of fibrotic transformation and leukemic progression [

11,

58,

83]. Moreover, recent insights from 3D chromatin structure studies suggest that the 46/1 haplotype may promote a PD-L1–mediated immunosuppressive niche, contributing to disease progression and treatment resistance [

78].

Thus, this haplotype could serve as a crucial biomarker — not only for early diagnosis and risk stratification in MPNs, but also for monitoring resistant subclones and predicting long-term outcomes. Its identification may support the development of personalized therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing disease progression and drug resistance.

8. Last Frontier: Epigenetic Therapies

Epigenetic therapies, such as DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) or histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, could be investigated as adjuncts to standard JAK inhibition in patients with the 46/1 haplotype, targeting the modified epigenetic landscape that might confer a survival advantage. DNMT and HDAC inhibitors induce DNA demethylation and histone acetylation, respectively, leading to the reactivation of silenced genes and dramatic morphological and functional changes in cancer cells [

84]. One of the consequences of HDAC inhibition is the continuous activation of the STAT protein, involved in the JAK/STAT pathway [

85,

86]. For example, HDAC8 inhibitors modulate the JAK/STAT pathway in patients with MPN [

87]. It has been demonstrated that HDACi, when combined with JAK2i, inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells, leading to apoptosis [

88,

89].

Otherwise, DNMT can act on the JAK7STAT3 pathway, for instance, reducing its activation. DNMT inhibitors reverse DNA hypermethylation, which may lead to the reactivation of silenced tumor suppressor genes or negative regulators of the JAK/STAT pathway. For example, they can act on genes encoding SOCS proteins (Suppressors of Cytokine Signalling), which are key negative regulators of the JAK/STAT pathway. If these genes are epigenetically silenced in MPNs, DNMT inhibitors can restore their expression and dampen pathway activation [

90].

So, although JAK inhibitors primarily reduce symptoms, control splenomegaly, and improve quality of life, they do not fully eradicate the mutant clone or prevent disease progression to MF or acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Otherwise, DNMT inhibitors, such as azacitidine or decitabine, inhibit DNA methyltransferase enzymes, resulting in the hypomethylation of DNA. This process can reactivate silenced tumor suppressor genes and potentially reverse abnormal epigenetic changes that drive the disease [

91].

This is the reason why combinatory treatments can be the driving discovery to more effective therapy. An in-depth analysis is necessary to investigate the potential side effects caused by their combination. For instance, in the case of JAKi combined with DNMTi, possible overlapping toxicities must be considered, because the cytopenia caused by both could limit their combined use.

Moreover, further studies about patients’ genetics are required, to identify those who will benefit most from this combination. At least, ongoing research is evaluating the safety and efficacy of combining these therapies in MPNs.

In recent years, the haplotype has been shown to have potential as a promising biomarker for various aspects of MPNs.

Discovered as a genetic variant of the Jak2 gene, it has been shown to predispose individuals to the acquisition of the JAK2 V617F mutation, which results in the gain-of-function of the resulting protein, leading to constitutive activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in MPNs.

Thus, numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the mechanism by which its presence causes this alteration, and its role in modifying the epigenetic landscape has emerged from these studies.

9. Discussion

The haplotype has been shown to predispose to the acquisition of V617F mutation, thus investigating its presence in the patient’s population helps clinicians to predict MPN onset. The potential of the haplotype as a predictive biomarker for the development of the MPNs, proposing its use for an early diagnosis of these pathologies, is that it allows non-invasive analysis, such as peripheral venous blood sampling and the consequent DNA extraction and analysis, to predict the outcome of the MPN and their therapies.

Further analysis has been conducted to investigate its association with the onset of onco-drug resistance in patients with MPN who are positive for the V617F mutation. An association has been discovered between patients with the 46/1 haplotype, tagged by the rs10974944 SNP, where the G allele represents the risk allele, and those with most symptoms related to the onset of onco-drug resistance [

7]. Consequently, it has been supposed that the presence of the 46/1 haplotype predisposes to thrombocytosis, leucocytosis, splenomegaly and hepatomegaly, characteristic symptoms of MPNs, which in turn lead to onco-drug resistance. Further studies are required to validate the association between the haplotype considered and the onset of onco-drug resistance itself.

In addition, due to the narrow cardinality of the sample analyzed, these data must be confirmed by expanding the sample under study. If confirmed, this conclusion suggests another use of the haplotype as a promising therapeutic marker [

70]. A new therapy can be used to directly target the haplotype, thereby preventing the consequences of its expression, such as the epigenetic landscape alterations, associated with the gain of the V617F mutation.

Nowadays, many therapies are in trials, alone or in combination. JAK inhibitors are most used as first and second-line therapies. To overcome the problem of the epigenetic landscape being modified in the presence of the JAK2 haplotype 46/1, epigenetic therapies, such as DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) or histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, have been proposed in combination with classical therapies [

84,

90]. The advantage of these epigenetic therapies is that they modulate the expression of genes involved in the JAK/STAT pathway, thereby regulating the pathogenic pathway upstream. It has become clear that haplotype identification offers a crucial advantage in therapy, not only because it may become a new therapy itself, but also because its identification enables the most efficient therapies, based on the patient’s genetics.

Other studies are required to explore the balance between benefits and risks for the patients, considering the combination of their side effects to evaluate if the combination prevents or enhances them.

At least, the haplotype is linked with the worsening of the MPNs. Although the narrow cardinality of the samples analyzed, the G allele of the 46/1 haplotype, tagged by the rs10974944 SNP, has been demonstrated to be associated with the evolution of PV or ET to a myelofibrotic condition [

7]. These data suggest that early identification of haplotype in patients could help with disease management, converging on the conclusion that the GGCC haplotype could also serve as a biomarker for the evolution of the pathology.

These results could help medical personnel predict the rise and evolution of MPNs, guiding them to better treatment, considering the increased possibility of evolution to MF in patients with this haplotype.

All these discoveries together open the potential of personalized medicine based on the genetic profile of each patient. The potential of the haplotype is first to be easily detectable, thanks to techniques such as PCR or gel electrophoresis, which are used routinely in clinical laboratories. The knowledge of four different SNPs available to tag the haplotype makes the protocol easier to develop. In fact, many studies propose protocols for this analysis, such as those of Trifa et al. [

9] that developed a simple and inexpensive PCR-RFLP assay for studying the

Jak2 rs10974944 SNP, those of Pagliarini-e-Silva S. et al. [

51] that make some changes in Trifa’s protocol, to allow better visualization of the bands, or those of Perrone et al. [

7] that is based on Trifa’s version.

Another advantage of using the haplotype is in diagnosis, as the presence of the haplotype precedes the acquisition of the V617F mutation, which is typically used for confirming MPN diagnosis. Screening, including the 46/1 haplotype, could be an innovative example of early diagnosis for MPNs, allowing clinicians to intervene in a timely manner.

The GGCC 46/1 haplotype could play a key role in developing new therapeutic strategies tailored to each patient’s genetics. Used alone or in combination with other therapies, it could decrease the side effects due to the broad spectrum of action of the therapies now available. Although an in-depth analysis of its therapeutic role is required, its monitoring could help clinicians predict the worsening of MPNs such as PV or ET. This could aid in selecting a therapy that considers the potential progression of MF.

To sum up, the potential of the haplotype is unmistakable; therefore, further studies are necessary to evaluate its practical application.

10. Conclusions

The haplotype 46/1 is one of the major discoveries in hematological malignancies management, because it has been discovered as a novel marker for early diagnosis and risk-stratification in MPN.

The haplotype 46/1 predisposes to the acquisition of the V617F mutation in MPN patients, representing an innovative target for early diagnosis. Moreover, it presents many advantages because it is easily detectable with non-invasive methods and it allows for personalized diagnostic approaches, based on the genetic profile of each patient.

In addition, many studies have demonstrated the role in leading to the onset of onco-drug resistance. This implies that it might be a useful predictive biomarker for an individual’s susceptibility to develop the symptoms typical of this condition.

Nevertheless, this evidence must be validated by further studies, but it represents promising preliminary results for the inclusion of the haplotype in the field of personalized medicine.

11. Future Directions

Looking ahead, further investigations are warranted to bridge the existing knowledge gaps. A major limitation in the current literature is the lack of longitudinal data. In addition, the narrow cardinality of the sample analyzed is a consistent constraint for results’ validation, especially considering the low prevalence of the variable considered, the G allele, in the general population. Consequently, further studies should aim to extend the sample under study, maybe with multicentre research.

Further elucidation of the epigenetic landscape of the haplotype may uncover novel therapeutic targets. Understanding these mechanisms could pave the way for novel diagnostic tools or therapeutic strategies, allowing a precise and quick management of patients with high risk-stratification.

Overall, these future directions hold great promise for enhancing our understanding and management of myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Acknowledgments

The authors are highly thankful to the Alessia Pallara and Triacorda Associations for providing financial support for the present study and for the research activities of the Clinical Proteomic Lab. Also, we duly acknowledge (i) Dott. Antonio Danieli, Laboratory of General Physiology, University of Salento, for its technical support and (ii) all medical stuff from the Hematology and Stem Cell Transplant Unit, Onco-Hematological Department, who contributed to this work with their data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P., S.S., B.P., D.S., M.M. and N.D.R.; methodology, M.P., S.S., B.P., A.T. and R.M.; investigation M.P., S.S. and B.P.; resources, M.M. and N.D.R.; writing— original draft preparation, M.P., S.S., B.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P., S.S., B.P., A.T., G.L., R.M., D.S., M.M. and N.D.R.; supervision, S.S., D.S., M.M. and N.D.R.; project administration, M.M. and N.D.R.; funding acquisition, M.M. and N.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thapa B, Fazal S, Parsi M, Rogers HJ. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. 2025.

- Barbui T, Barosi G, Birgegard G, Cervantes F, Finazzi G, Griesshammer M, et al. Philadelphia-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: critical concepts and management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:761–70. [CrossRef]

- Kim S-Y, Bae SH, Bang S-M, Eom K-S, Hong J, Jang S, et al. The 2020 revision of the guidelines for the management of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Korean J Intern Med 2021;36:45–62. [CrossRef]

- Jang M-A, Choi CW. Recent insights regarding the molecular basis of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Korean J Intern Med 2020;35:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bader MS, Meyer SC. JAK2 in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Still a Protagonist. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022;15. [CrossRef]

- Jones A V, Chase A, Silver RT, Oscier D, Zoi K, Wang YL, et al. JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet 2009;41:446–9. [CrossRef]

- Perrone M, Sergio S, Tarantino A, Loglisci G, Matera R, Seripa D, et al. Association of JAK2 Haplotype GGCC_46/1 with the Response to Onco-Drug in MPNs Patients Positive for JAK2V617F Mutation. Onco 2024;4:241–56. [CrossRef]

- Jang M-A, Choi CW. Recent insights regarding the molecular basis of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Korean J Intern Med 2020;35:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Trifa AP, Cucuianu A, Popp RA. Development of a reliable PCR-RFLP assay for investigation of the JAK2 rs10974944 SNP, which might predispose to the acquisition of somatic mutation JAK2(V617F). Acta Haematol 2010;123:84–7. [CrossRef]

- Levine RL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Gilliland DG. Role of JAK2 in the pathogenesis and therapy of myeloproliferative disorders. Nat Rev Cancer 2007;7:673–83. [CrossRef]

- Olcaydu D, Harutyunyan A, Jäger R, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Pabinger I, et al. A common JAK2 haplotype confers susceptibility to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet 2009;41:450–4. [CrossRef]

- Paes J, Silva GA V, Tarragô AM, Mourão LP de S. The Contribution of JAK2 46/1 Haplotype in the Predisposition to Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Ngoc NT, Hau BB, Vuong NB, Xuan NT. JAK2 rs10974944 is associated with both V617F-positive and negative myeloproliferative neoplasms in a Vietnamese population: A potential genetic marker. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2022;10:e2044. [CrossRef]

- Kondo M, Wagers AJ, Manz MG, Prohaska SS, Scherer DC, Beilhack GF, et al. Biology of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors: implications for clinical application. Annu Rev Immunol 2003;21:759–806. [CrossRef]

- Josil J, Thuillier E, Chambrun L, Plo I. [Natural history of myeloproliferative neoplasms by a phylogenetic tree-based approach]. Med Sci (Paris) 2024;40:209–11. [CrossRef]

- Verma T, Papadantonakis N, Peker Barclift D, Zhang L. Molecular Genetic Profile of Myelofibrosis: Implications in the Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Advancements. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay D, Kremyanskaya M, Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R. Diagnosis and Treatment of Polycythemia Vera: A Review. JAMA 2025;333:153–60. [CrossRef]

- Barranco-Lampón G, Martínez-Castro R, Arana-Luna L, Álvarez-Vera JL, Rojas-Castillejos F, Peñaloza-Ramírez R, et al. Polycythemia vera. Gac Med Mex 2022;158:11–6. [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2021 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol 2021;96:145–62. [CrossRef]

- Tefferi A, Mudireddy M, Mannelli F, Begna KH, Patnaik MM, Hanson CA, et al. Blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasm: Mayo-AGIMM study of 410 patients from two separate cohorts. Leukemia 2018;32:1200–10. [CrossRef]

- Genthon A, Killian M, Mertz P, Cathebras P, Gimenez De Mestral S, Guyotat D, et al. [Myelofibrosis: A review]. Rev Med Interne 2021;42:101–9. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein DB, Cavalleri GL. Genomics: understanding human diversity. Nature 2005;437:1241–2. [CrossRef]

- Tanner JW, Chen W, Young RL, Longmore GD, Shaw AS. The conserved box 1 motif of cytokine receptors is required for association with JAK kinases. J Biol Chem 1995;270:6523–30. [CrossRef]

- Ferrao RD, Wallweber HJ, Lupardus PJ. Receptor-mediated dimerization of JAK2 FERM domains is required for JAK2 activation. Elife 2018;7. [CrossRef]

- Imada K, Leonard WJ. The Jak-STAT pathway. Mol Immunol 2000;37:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Staerk J, Constantinescu SN. The JAK-STAT pathway and hematopoietic stem cells from the JAK2 V617F perspective. JAKSTAT 2012;1:184–90. [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka K, Saharinen P, Pesu M, Holt VET, Silvennoinen O, O’Shea JJ. The Janus kinases (Jaks). Genome Biol 2004;5:253. [CrossRef]

- Nair PC, Piehler J, Tvorogov D, Ross DM, Lopez AF, Gotlib J, et al. Next-Generation JAK2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Lessons from Structure-Based Drug Discovery Approaches. Blood Cancer Discov 2023;4:352–64. [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn BA, Quelle FW, Cleveland JL, Yi T, Ihle JN. Structure of the murine Jak2 protein-tyrosine kinase and its role in interleukin 3 signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993;90:8429–33. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda T, Feng J, Witthuhn BA, Sekine Y, Ihle JN. Determination of the transphosphorylation sites of Jak2 kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;325:586–94. [CrossRef]

- Neubauer H, Cumano A, Müller M, Wu H, Huffstadt U, Pfeffer K. Jak2 deficiency defines an essential developmental checkpoint in definitive hematopoiesis. Cell 1998;93:397–409. [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi-Tago M, Pelletier S, Matsuda T, Parganas E, Ihle JN. Receptor specific downregulation of cytokine signaling by autophosphorylation in the FERM domain of Jak2. EMBO J 2006;25:4763–72. [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz-Munoz AM, Argetsinger LS, Kouadio J-LK, Stensballe A, Jensen ON, Cline JM, et al. Phosphorylation of JAK2 at serine 523: a negative regulator of JAK2 that is stimulated by growth hormone and epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol 2006;26:4052–62. [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen O, Hubbard SR. Molecular insights into regulation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2015;125:3388–92. [CrossRef]

- Dusa A, Mouton C, Pecquet C, Herman M, Constantinescu SN. JAK2 V617F constitutive activation requires JH2 residue F595: a pseudokinase domain target for specific inhibitors. PLoS One 2010;5:e11157. [CrossRef]

- Leroy E, Dusa A, Colau D, Motamedi A, Cahu X, Mouton C, et al. Uncoupling JAK2 V617F activation from cytokine-induced signalling by modulation of JH2 αC helix. Biochem J 2016;473:1579–91. [CrossRef]

- Agashe RP, Lippman SM, Kurzrock R. JAK: Not Just Another Kinase. Mol Cancer Ther 2022;21:1757–64. [CrossRef]

- de Freitas RM, da Costa Maranduba CM. Myeloproliferative neoplasms and the JAK/STAT signaling pathway: an overview. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 2015;37:348–53. [CrossRef]

- Schuringa JJ, Chung KY, Morrone G, Moore MAS. Constitutive activation of STAT5A promotes human hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and erythroid differentiation. J Exp Med 2004;200:623–35. [CrossRef]

- Teofili L, Martini M, Cenci T, Petrucci G, Torti L, Storti S, et al. Different STAT-3 and STAT-5 phosphorylation discriminates among Ph-negative chronic myeloproliferative diseases and is independent of the V617F JAK-2 mutation. Blood 2007;110:354–9. [CrossRef]

- Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Mudireddy M, Finke CM, Hanson CA, Ketterling RP, et al. The germline JAK2 GGCC (46/1) haplotype and survival among 414 molecularly-annotated patients with primary myelofibrosis. Am J Hematol 2019;94:299–305. [CrossRef]

- Hermouet S, Vilaine M. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype: a marker of inappropriate myelomonocytic response to cytokine stimulation, leading to increased risk of inflammation, myeloid neoplasm, and impaired defense against infection? Haematologica 2011;96:1575–9. [CrossRef]

- Anelli L, Zagaria A, Specchia G, Albano F. The JAK2 GGCC (46/1) Haplotype in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Causal or Random? Int J Mol Sci 2018;19. [CrossRef]

- Vannucchi AM, Guglielmelli P. The JAK2 46/1 (GGCC) MPN-predisposing haplotype: A risky haplotype, after all. Am J Hematol 2019;94:283–5. [CrossRef]

- Nasillo V, Riva G, Paolini A, Forghieri F, Roncati L, Lusenti B, et al. Inflammatory Microenvironment and Specific T Cells in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Immunopathogenesis and Novel Immunotherapies. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22. [CrossRef]

- Harutyunyan AS, Giambruno R, Krendl C, Stukalov A, Klampfl T, Berg T, et al. Germline RBBP6 mutations in familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2016;127:362–5. [CrossRef]

- Spasovski V, Tosic N, Nikcevic G, Stojiljkovic M, Zukic B, Radmilovic M, et al. The influence of novel transcriptional regulatory element in intron 14 on the expression of Janus kinase 2 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. J Appl Genet 2013;54:21–6. [CrossRef]

- Park HS, Son BR, Shin KS, Kim HK, Yang Y, Jeong Y, et al. Germline JAK2 V617F mutation as a susceptibility gene causing myeloproliferative neoplasm in first-degree relatives. Leuk Lymphoma 2020;61:3251–4. [CrossRef]

- Jones A V, Campbell PJ, Beer PA, Schnittger S, Vannucchi AM, Zoi K, et al. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype predisposes to MPL-mutated myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2010;115:4517–23. [CrossRef]

- Andrikovics H, Nahajevszky S, Koszarska M, Meggyesi N, Bors A, Halm G, et al. JAK2 46/1 haplotype analysis in myeloproliferative neoplasms and acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2010;24:1809–13. [CrossRef]

- Pagliarini-e-Silva S, Santos BC, Pereira EM de F, Ferreira ME, Baraldi EC, Sell AM, et al. Evaluation of the association between the JAK2 46/1 haplotype and chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms in a Brazilian population. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:5–9. [CrossRef]

- Kilpivaara O, Mukherjee S, Schram AM, Wadleigh M, Mullally A, Ebert BL, et al. A germline JAK2 SNP is associated with predisposition to the development of JAK2(V617F)-positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat Genet 2009;41:455–9. [CrossRef]

- Pardanani AD, Levine RL, Lasho T, Pikman Y, Mesa RA, Wadleigh M, et al. MPL515 mutations in myeloproliferative and other myeloid disorders: a study of 1182 patients. Blood 2006;108:3472–6. [CrossRef]

- Guglielmelli P, Biamonte F, Spolverini A, Pieri L, Isgrò A, Antonioli E, et al. Frequency and clinical correlates of JAK2 46/1 (GGCC) haplotype in primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2010;24:1533–7. [CrossRef]

- Yarbro, JW. Mechanism of action of hydroxyurea. Semin Oncol 1992;19:1–10.

- Bertsias, G. Therapeutic targeting of JAKs: from hematology to rheumatology and from the first to the second generation of JAK inhibitors. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2020;31:105–11. [CrossRef]

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Levy RS, Gupta V, DiPersio JF, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:799–807. [CrossRef]

- Passamonti F, Maffioli M. The role of JAK2 inhibitors in MPNs 7 years after approval. Blood 2018;131:2426–35. [CrossRef]

- Harrison CN, Schaap N, Mesa RA. Management of myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib failure. Ann Hematol 2020;99:1177–91. [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorf JP, Jaszczur SM, Afifi S, Zhao JC, Zeidan AM. Beyond Ruxolitinib: Fedratinib and Other Emergent Treatment Options for Myelofibrosis. Cancer Manag Res 2019;11:10777–90. [CrossRef]

- Talpaz M, Kiladjian J-J. Fedratinib, a newly approved treatment for patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm-associated myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2021;35:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ross DM, Babon JJ, Tvorogov D, Thomas D. Persistence of myelofibrosis treated with ruxolitinib: biology and clinical implications. Haematologica 2021;106:1244–53. [CrossRef]

- Putter JS, Seghatchian J. Polycythaemia vera: molecular genetics, diagnostics and therapeutics. Vox Sang 2021;116:617–27. [CrossRef]

- Kim S-Y, Bae SH, Bang S-M, Eom K-S, Hong J, Jang S, et al. The 2020 revision of the guidelines for the management of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Korean J Intern Med 2021;36:45–62. [CrossRef]

- Ajayi S, Becker H, Reinhardt H, Engelhardt M, Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N, et al. Ruxolitinib. Recent Results Cancer Res 2018;212:119–32. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Larrán A, Cervantes F, Besses C. [Treatment of essential thrombocythemia]. Med Clin (Barc) 2013;141:260–4. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Trillos A, Gaya A, Maffioli M, Arellano-Rodrigo E, Calvo X, Díaz-Beyá M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of hydroxyurea in the treatment of the hyperproliferative manifestations of myelofibrosis: results in 40 patients. Ann Hematol 2010;89:1233–7. [CrossRef]

- Barbui T, Barosi G, Birgegard G, Cervantes F, Finazzi G, Griesshammer M, et al. Philadelphia-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: critical concepts and management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:761–70. [CrossRef]

- Newberry KJ, Patel K, Masarova L, Luthra R, Manshouri T, Jabbour E, et al. Clonal evolution and outcomes in myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib discontinuation. Blood 2017;130:1125–31. [CrossRef]

- Wolf A, Eulenfeld R, Gäbler K, Rolvering C, Haan S, Behrmann I, et al. JAK2-V617F-induced MAPK activity is regulated by PI3K and acts synergistically with PI3K on the proliferation of JAK2-V617F-positive cells. JAKSTAT 2013;2:e24574. [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama A, Verstovsek S. Molecular pathways: Jak/STAT pathway: mutations, inhibitors, and resistance. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:1933–40. [CrossRef]

- Saleem M, Aden LA, Mutchler AL, Basu C, Ertuglu LA, Sheng Q, et al. Myeloid-Specific JAK2 Contributes to Inflammation and Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure. Circ Res 2024;135:890–909. [CrossRef]

- Greenfield G, McMullin MF. Epigenetics in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Front Oncol 2023;13:1206965. [CrossRef]

- Pérez C, Pascual M, Martín-Subero JI, Bellosillo B, Segura V, Delabesse E, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation profile of chronic and transformed classic Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Haematologica 2013;98:1414–20. [CrossRef]

- Nahajevszky S, Andrikovics H, Batai A, Adam E, Bors A, Csomor J, et al. The prognostic impact of germline 46/1 haplotype of Janus kinase 2 in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2011;96:1613–8. [CrossRef]

- Moliterno AR, Kaizer H. Applied genomics in MPN presentation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2020;2020:434–9. [CrossRef]

- Dawson MA, Curry JE, Barber K, Beer PA, Graham B, Lyons JF, et al. AT9283, a potent inhibitor of the Aurora kinases and Jak2, has therapeutic potential in myeloproliferative disorders. Br J Haematol 2010;150:46–57. [CrossRef]

- Carreño-Tarragona G, Tiana M, Rouco R, Leivas A, Victorino J, García-Vicente R, et al. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype influences PD-L1 expression. Blood 2025;145:2196–201. [CrossRef]

- Prestipino A, Emhardt AJ, Aumann K, O’Sullivan D, Gorantla SP, Duquesne S, et al. Oncogenic JAK2V617F causes PD-L1 expression, mediating immune escape in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Transl Med 2018;10. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov D, Milosevic Feenstra JD, Sadovnik I, Herrmann H, Peter B, Willmann M, et al. Phenotypic characterization of disease-initiating stem cells in JAK2- or CALR-mutated myeloproliferative neoplasms. Am J Hematol 2023;98:770–83. [CrossRef]

- Milosevic Feenstra JD, Jäger R, Schischlik F, Ivanov D, Eisenwort G, Rumi E, et al. PD-L1 overexpression correlates with JAK2-V617F mutational burden and is associated with 9p uniparental disomy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Am J Hematol 2022;97:390–400. [CrossRef]

- Macedo LC, Santos BC, Pagliarini-e-Silva S, Pagnano KBB, Rodrigues C, Quintero FC, et al. JAK2 46/1 haplotype is associated with JAK2 V617F--positive myeloproliferative neoplasms in Brazilian patients. Int J Lab Hematol 2015;37:654–60. [CrossRef]

- Rumi E, Cazzola M. Diagnosis, risk stratification, and response evaluation in classical myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2017;129:680–92. [CrossRef]

- Xu S, Ren J, Chen H Bin, Wang Y, Liu Q, Zhang R, et al. Cytostatic and apoptotic effects of DNMT and HDAC inhibitors in endometrial cancer cells. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:1881–7. [CrossRef]

- Lane AA, Chabner BA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5459–68. [CrossRef]

- Fantin VR, Loboda A, Paweletz CP, Hendrickson RC, Pierce JW, Roth JA, et al. Constitutive activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription predicts vorinostat resistance in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res 2008;68:3785–94. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti A, Oehme I, Witt O, Oliveira G, Sippl W, Romier C, et al. HDAC8: a multifaceted target for therapeutic interventions. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015;36:481–92. [CrossRef]

- Zeng H, Qu J, Jin N, Xu J, Lin C, Chen Y, et al. Feedback Activation of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor Limits Response to Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors in Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell 2016;30:459–73. [CrossRef]

- Hosford SR, Miller TW. Clinical potential of novel therapeutic targets in breast cancer: CDK4/6, Src, JAK/STAT, PARP, HDAC, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2014;7:203–15. [CrossRef]

- Gan F, Zhou X, Zhou Y, Hou L, Chen X, Pan C, et al. Nephrotoxicity instead of immunotoxicity of OTA is induced through DNMT1-dependent activation of JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway by targeting SOCS3. Arch Toxicol 2019;93:1067–82. [CrossRef]

- Wei K-L, Chou J-L, Chen Y-C, Jin H, Chuang Y-M, Wu C-S, et al. Methylomics analysis identifies a putative STAT3 target, SPG20, as a noninvasive epigenetic biomarker for early detection of gastric cancer. PLoS One 2019;14:e0218338. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).