1. Introduction

Tight gas is one of the key areas of unconventional natural gas exploration worldwide, and large-scale tight gas exploration and development has been achieved in many basins in China [

1,

2,

3]. Within the Upper Paleozoic successions of the Ordos Basin, tight gas resources are 13.32 × 10

12 m

3, accounting for approximately 61% of China’s total tight gas resources [

4]. Major gas fields include the Sulige, Mizhi, Zizhou, Shenmu, Daniudi, Yan’an, and Dongsheng, with annual production exceeding 400 × 10

8 m

3. These fields constitute China’s major tight gas province, exhibiting the largest proven reserves and highest gas production in China [

5].

The Permian He 1 Member gas reservoir exhibits extensive distribution in the Ordos Basin. Vertically and laterally amalgamated channel sandstone bodies form sheet-like units with remarkable regional continuity [

6,

7,

8]. Reservoir lithologies predominantly comprise lithic sandstones and sublithic sandstones [

1,

9]. Severe mechanical compaction and intensive cementation during diagenesis have resulted in pore systems dominated by intercrystalline micropores and intragranular dissolution pores, with minor intergranular pores and microfractures. Porosity ranges primarily between 4-8%, while permeability falls within 0.01-1 mD, defining typical low-porosity, low-permeability tight sandstone reservoirs [

10]. Production wells exhibit negligible natural gas flow capacity. After hydraulic fracturing stimulation, vertical wells yield 1 × 10

4–2 × 10

4 m

3/d, whereas horizontal wells achieve up to 10.7 × 10

4 m

3/d.

Previous studies about the He 1 Member sandstone reservoirs have indicated that favorable reservoirs are governed by several factors. Sedimentary microfacies constitute the fundamental prerequisite for favorable reservoir formation [

11,

12], while secondary porosity generation through dissolution directly enables reservoir quality enhancement [

9,

13]. Moderate amounts of chlorite coatings reinforce mechanical compaction resistance and inhibit quartz overgrowth, thereby preserving primary porosity [

14,

15]. Microporosity within clay minerals and volcanic ash matrix, including intercrystalline and dissolution micropores, augments reservoir quality [

16,

17]. Microfractures enhance reservoir permeability [

18,

19]. However, natural gas exploration in the southern basin revealed conventional reservoirs that exhibit > 1 mD permeability and natural gas flow capacity. Existing genetic models cannot explain this phenomenon. Insufficient understanding of the reservoir formation mechanism has led to poor constraints on the distribution patterns and scale of this reservoir, thereby limiting the selection of natural gas exploration targets.

The aim of the study is to elucidate the genesis of conventional reservoirs (K > 1 mD) within tight sandstones, thereby providing a case of differential diagenesis and pore evolution in fluvial depositional systems.

2. Geological Setting

Ordos Basin, occupying approximately 370,000 km

2, is one of China’s major sedimentary basins. It features a large west-dipping monoclinal structure and ranks among China’s most hydrocarbon-rich basins (

Figure 1).

Following deposition of the Middle Ordovician Majiagou Formation carbonates, the Caledonian Orogeny triggered regional uplift of the North China Platform (including the Ordos Basin). The Ordos Basin was subjected to 140 million years of subaerial exposure with intense weathering, leaching, and erosion. During the Late Carboniferous, persistent southward subduction of the Paleo-Asian Ocean (Solon Ocean) along the northern margin of the North China Platform and rapid expansion of the Mianlue Ocean to the south induced gradual subsidence of the North China Platform, initiating renewed sedimentation [

20]. The Late Paleozoic stratigraphic successions in the Ordos Basin comprise Late Carboniferous Benxi Formation and Early Permian Taiyuan Formation mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sequences with coal seams. This progression continues into the Early Permian Shanxi Formation lacustrine-deltaic siliciclastics interbedded with coals, succeeded by Middle Permian Shihezi Formation and Late Permian Shiqianfeng Formation fluvial siliciclastic successions.

During He 1 Member deposition, persistent southward subduction and compression of the Amur Block along the northern margin of the North China Platform induced further crustal uplift [

21]. The northern uplift generated abundant detrital supply and enhanced surface runoff activity, developing long-transported fluvial depositional systems. Concurrently, uplift of the Qinling Orogenic Belt in the southern basin intensified volcanic activity, evidenced by tuff intervals encountered in boreholes and pervasive volcanic ash matrix within sandstones.

3. Sampling and Methods

Detailed core descriptions were conducted on nine cored wells within the study area, with 93 representative samples collected for integrated analysis including conventional petrophysical measurements, resin-impregnated thin-section petrography, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), high-pressure mercury injection (HPMI) capillary pressure analysis, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) mineralogy.

Reservoir types were classified based on conventional petrophysical properties and pore-types analysis. Subsequent investigation delineated petrology, pore structure, and diagenesis of the different reservoir types. Finally, the study synthesized diagenetic sequences for each reservoir type and elucidated controlling factors of favorable reservoirs.

4. Results

4.1. Sedimentary Microfacies and Characteristics

The He 1 Member is a braided fluvial system, within which four distinct sedimentary microfacies are identified based on sedimentary structures and sandstone stacking patterns: channel fills, longitudinal bars, transverse bars, and laminated sandstones (

Figure 2).

Channel fills form through fluvial incising and rapid sedimentary infilling, depositing dominantly granule conglomerates and coarse sandstones with abundant floating granule clasts. These deposits feature basal gravel lags (

Figure 3a) that fine upward into sand-dominated intervals. Bedding structures are poorly defined, though faint cross-bedding is discernible. The composition of sandstone is lithic to sublithic. They exhibit moderate rounding but poor sorting. The sandstones contain 59-83 vol.% quartz (average 62.5 vol.%), 15-38 vol.% rock fragments (average 28.34 vol.%), and 1-6 vol.% matrix (average 3.2 vol.%), with clay dominated by illite and illite-smectite mixed-layer clay minerals.

Longitudinal bars develop along channel axes through downstream accretion, composed of stacked downstream accretion units. These deposits consist predominantly of fine- to coarse-grained sandstones, occasionally intercalated with gravel-dominated bars (

Figure 3b). Vertical grain-size trends are poorly defined. Sedimentary structures are dominated by low-angle planar cross-bedding, with subordinate trough cross-bedding. The sandstones are primarily lithic sandstones, containing 55-69 vol.% quartz (average 60.38 vol.%), 22-39 vol.% lithic fragments (average 32.69 vol.%), and 2-5 vol.% matrix (average 3.03 vol.%), with significant altered volcanic rock fragment material and illite-smectite mixed-layer clay.

The transverse bar forms through vertical accretion, characterized by horizontal set boundaries; high-angle cross-bedding is well developed within the unit (

Figure 3c). These deposits consist predominantly of medium-to-coarse sandstones exhibiting faint vertical grain-size trends. The sandstones are primarily sublithic sandstones, containing 58-91 vol.% quartz (average 65.1 vol.%), 9-31 vol.% lithic fragments (average 20.2 vol.%), and 1-3 vol.% matrix (average 2.89 vol.%), with well-developed authigenic chlorite clay.

Laminated sandstones form through overbank deposition during flood events, typically accumulating atop bar surfaces or along channel margins. Individual beds range from several to tens of centimeters in thickness, exhibiting planar or slightly scoured basal contacts. These deposits display a typical vertical sequence: parallel-laminated or low-angle cross-bedded fine sandstones (

Figure 3d) grading upward into ripple-laminated siltstones with mica-rich horizons. This succession records waning flow energy during individual flood episodes. Laminated sandstones are lithic sandstones, containing 52-68 vol.% quartz (average 57 vol.%), 27-42 vol.% lithic fragments (average 34.5 vol.%), and 4-6 vol.% matrix (average 5.33 vol.%). The clay is dominated by illite.

4.2. Reservoir Quality

4.2.1. Porosity-Permeability Characteristics

The He 1 Member sandstones exhibit predominantly tight, low-permeability characteristics, though reservoir quality varies significantly among depositional microfacies. Transverse bar facies demonstrate superior physical properties on average, followed by channel fills and longitudinal bars, with laminated sandstones exhibiting the poorest reservoir quality (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4).

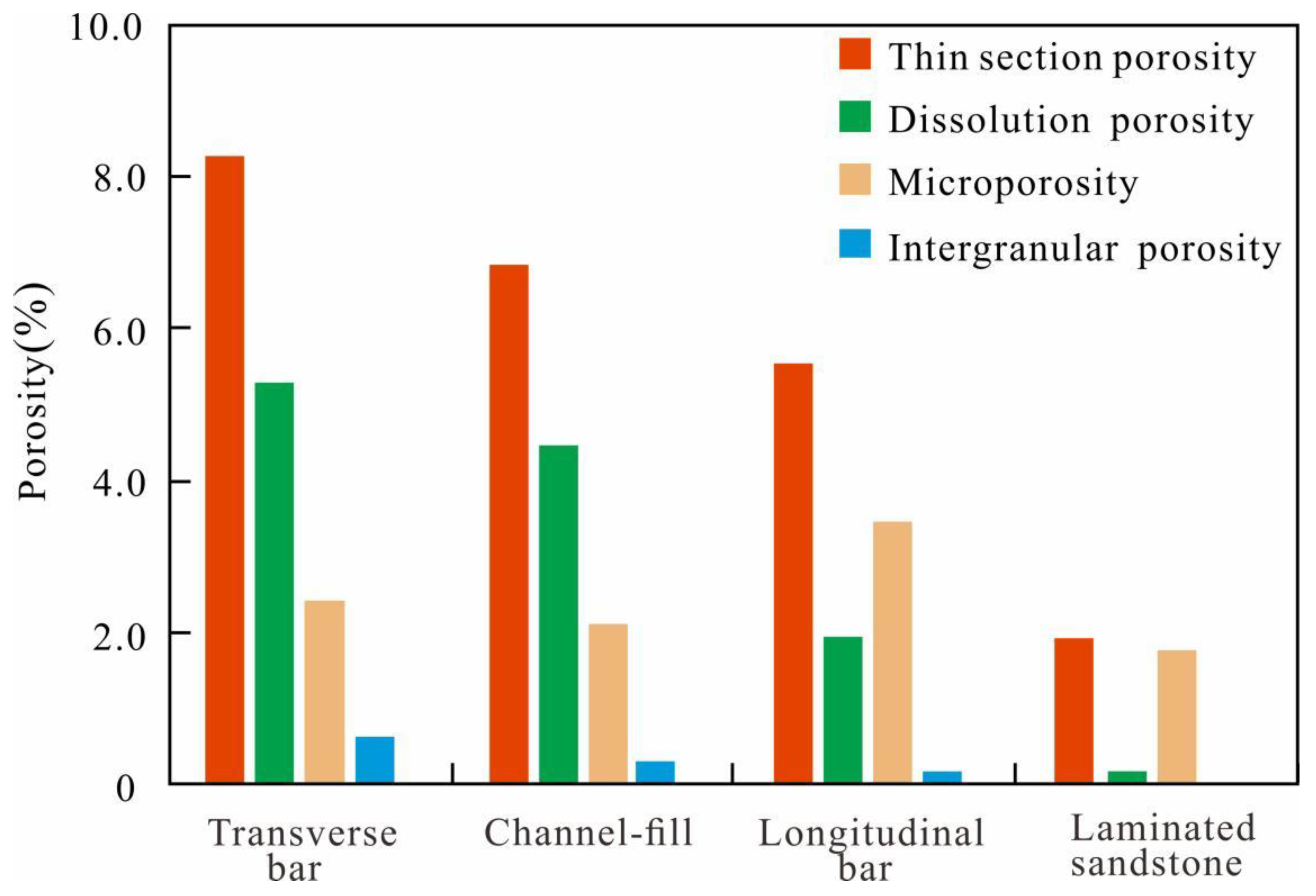

4.2.2. Pore Type

The He 1 Member sandstones are mainly composed of intragranular dissolution pores and micropores within clay, with intergranular pores being subordinate. Pore type distribution exhibits significant variation across depositional microfacies (

Figure 5). Transverse bar sandstones are dominated by dissolution pores and micropores, with highly variable amounts of intergranular pores. Channel fills and longitudinal bar sandstones primarily contain dissolution pores and micropores, with rare occurrence of intergranular pores. Laminated sandstones are principally characterized by micropores, occasionally displaying minor intragranular dissolution pores, and completely lack intergranular pores.

Based on pore types, the characteristics of porosity and permeability and gas production test data, sandstone reservoirs are classified into three categories:

Type I Reservoir: Dominated by dissolution pores and intergranular pores with porosity > 10% and permeability > 0.5 mD. These conventional reservoirs can get commercial gas flow rates without hydraulic fracturing stimulation.

Type II Reservoir: Primarily contain dissolution pores and micropores with sporadic intergranular pores. Porosity ranges from 8% to 10% and permeability 0.1-0.5 mD. Gas production ranges between 0.6 × 104–1.3 × 104 m3/d after fracturing stimulation.

Type III Reservoir: Characterized by micropores with subordinate dissolution pores. Porosity is 4-8% and permeability 0.07-0.1 mD. Gas production ranges from 0.1 × 104 to 0.5 × 104 m3/d after fracturing stimulation.

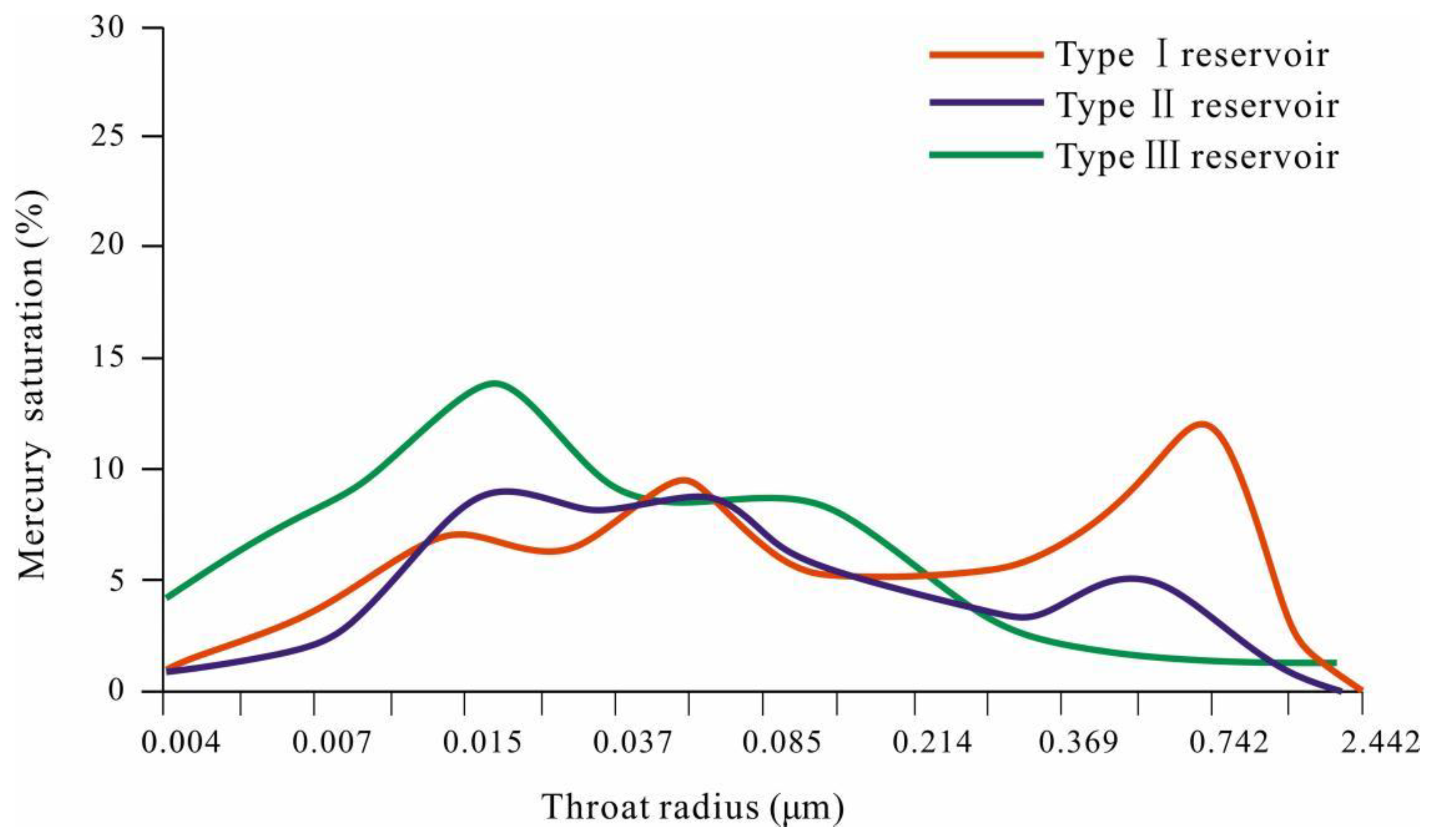

4.2.3. Pore Structure

Mercury injection capillary pressure (MICP) data indicate reservoirs with very fine to fine throats, poor throat sorting, and complex pore-throat structure. Different sandstone reservoirs have different pore-throat structures (

Figure 6):

Type I Reservoir exhibits entry pressures < 0.5 MPa and median pressures of 1.2-8.6 MPa (average 5.5 MPa). Pore volume accessible through throats > 1 μm constitutes 15.9-51.1% of total porosity (average 25.7%), with mercury withdrawal efficiency exceeding 38%.

Type II Reservoir exhibits moderate entry pressures (0.5-1 MPa) and median pressures of 3.4-26.2 MPa (average 9.9 MPa). Throat-connected porosity (>1 μm) represents 9.9-31.8% of total pores (average 11.5%), with mercury withdrawal efficiency > 30%.

Type III Reservoir features elevated entry pressures (typically > 1 MPa) and median pressures of 10.3-79.5 MPa (average 27.1 MPa). Pores linked to >1 μm throats account for 2.7-8.2% of total porosity (average 4.8%), with mercury withdrawal efficiency exceeding 20%.

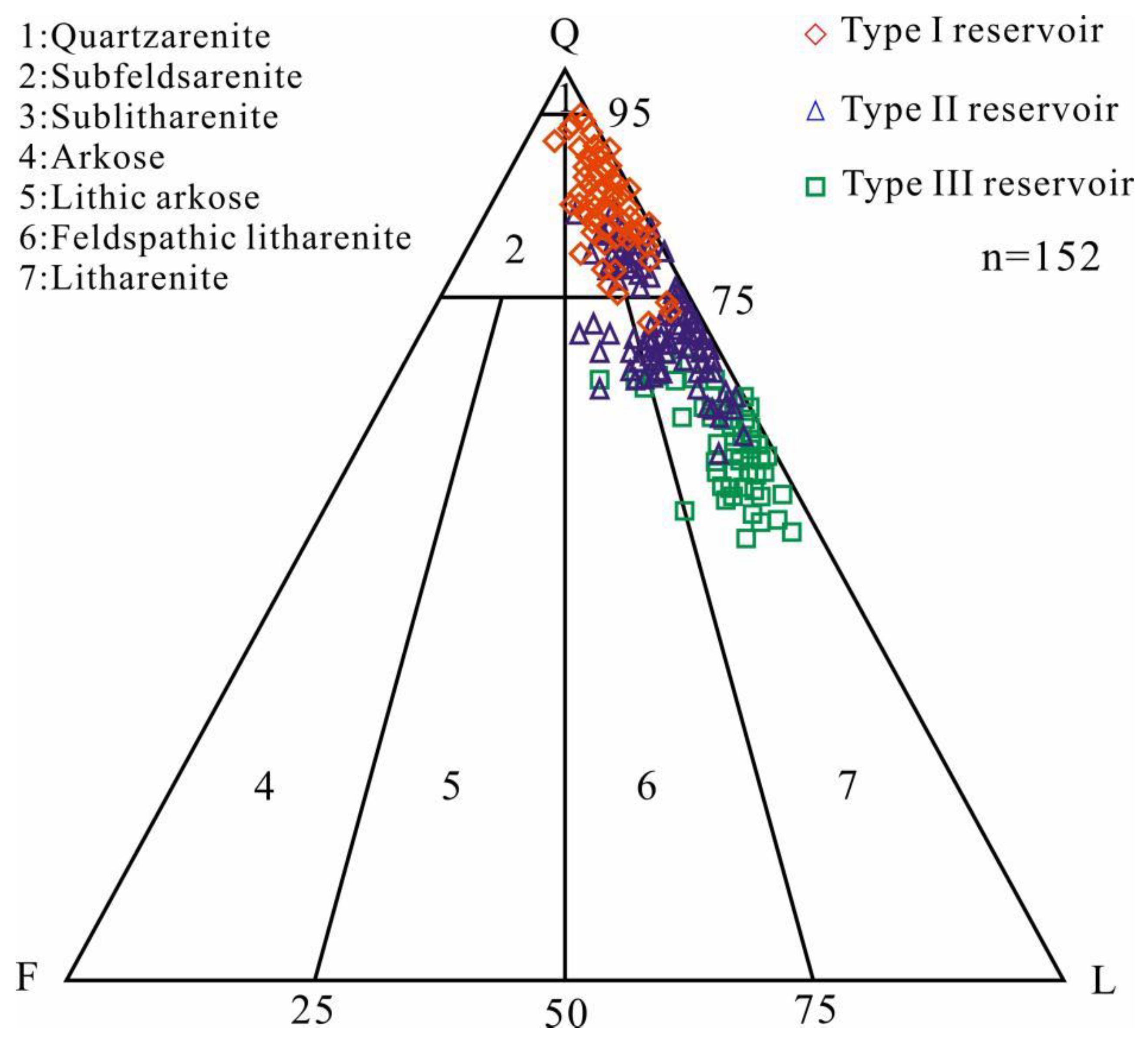

4.3. Petrological Characteristics

The three types of reservoir display marked differences in detrital grain texture, composition, and interstitial materials (

Table 1 and

Figure 7):

Type I Reservoirs comprise coarse-grained sublithic sandstones. Rigid quartz grains form frameworks with sparse, uniformly distributed lithic fragments. Minor volcanic rock fragments transform to illite-smectite mixed-layer clay. Well-developed pore-lining chlorite occurs with sporadic quartz overgrowths and heterogeneously distributed minor ferroan calcite.

Type II Reservoirs consist of medium-to-coarse-grained lithic sandstones to sublithic sandstones. Compared to Type I, they show elevated lithic content and significantly reduced pore-lining chlorite cementation. Clay mineral assemblages diverge markedly, with increased proportions of illite-smectite mixed-layer clay. Quartz overgrowths are pervasive.

Type III Reservoirs are medium-grained lithic sandstones with diminished intergranular chlorite clay relative to other types. Kaolinite and illite–smectite mixed-layer contents are similar to those in Type II Reservoirs, but the proportion of illite increases markedly. Quartz overgrowths are insignificant.

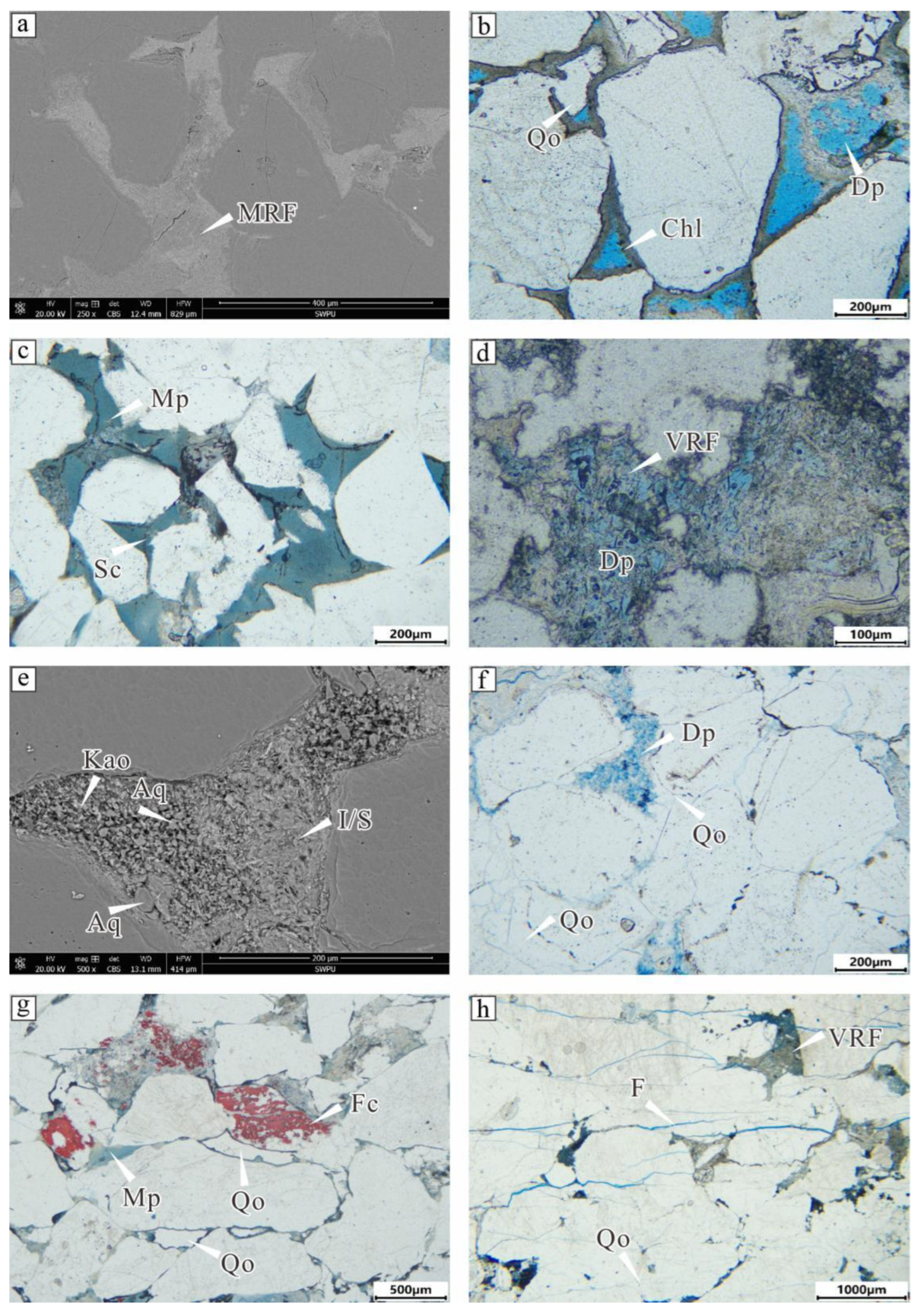

4.4. Diagenesis

4.4.1. Compaction

Despite similar burial depths (2600-3000 m) in the He 1 Member sandstones, compaction intensity varies substantially. Detrital grain contacts range from point contacts to concave-convex contacts (

Figure 8a,b). Under comparable vertical stress conditions, variations in grain contacts are predominantly controlled by ductile grain content [

23]. Within the He 1 Member, ductile grain content exhibits a significant negative correlation with grain size, a typical feature throughout the Ordos Basin [

24]. Consequently, coarser-grained sandstones exhibit progressively weaker compaction (

Figure 9).

4.4.2. Dissolution

Dissolution primarily occurs in volcanic rock fragments and volcanic ash matrix, generating intragranular dissolution pores, moldic pores, and micropores within the matrix (

Figure 8c,d). This process develops predominantly in sandstones with moderate ductile rock fragments content. When the content of ductile rock fragments is high, early mechanical compaction eliminates intergranular pores, inhibiting pore-water circulation and trapping the dissolution by-products within the reaction system. Conversely, sandstones lacking volcanic components exhibit underdeveloped dissolution due to the absence of soluble minerals.

Dissolution of volcanic rock fragments predominantly yields illite-smectite (I/S) mixed-layer clay and microquartz (

Figure 8e), with partial in situ precipitation within dissolution pores. Dissolution of volcanic ash matrix primarily generates illite-smectite mixed-layer clays and illite (

Figure 8c,d). Meanwhile, dissolution of volcanic materials releases substantial iron ions, magnesium ions and silica, supplying essential constituents for chlorite cements and quartz overgrowth [

25].

4.4.3. Cementation

(1) Chlorite cementation

Chlorite cements mainly occur as pore-lining with a thickness of 2-28 μm, exhibiting pronounced spatial heterogeneity in abundance. Pore-lining chlorite is abundant (up to 3%) in sandstones with well-developed intergranular pores (

Figure 8b). In contrast, they are virtually absent in sandstones characterized by pronounced quartz overgrowths, abundant matrix, and severe compaction caused by ductile rock fragment deformation (

Figure 8a,c,f).

(2) Silica cementation

Silica cements occur in two forms: quartz overgrowths and microquartz within micropores (

Figure 8e,f). Quartz overgrowths are widespread but highly variable in abundance. In quartz-rich sandstones, they may completely occlude intergranular pores, forming tightly cemented, non-porous sandstones. Maximum quartz overgrowth content reaches 8.3%, with hand specimens resembling quartzite. Conversely, sandstones with well-developed pore-lining chlorite or those containing high ductile lithic content under severe compaction lack quartz overgrowths (

Figure 8a,b). Microquartz primarily occurs within intragranular dissolution pores associated with dissolution products: illite-smectite mixed-layer clays, illite, and kaolinite (

Figure 8e). These crystals range from several μm to 30 μm in size and are genetically linked to volcanic lithic dissolution. Following alteration of volcanic materials, microquartz precipitates to varying degrees within the micropores [

25].

4.4.4. Other Diagenetic Alterations

(1) Ferroan calcite replacement and cementation

Ferroan calcite locally replaces volcanic rock fragments or matrix (

Figure 8g), while rarely occurring as intergranular pore-filling cement. Its content ranges from 0-8% (average 1.3%), exerting negligible impact on reservoir quality.

(2) Fracturing

A set of shear fractures is observed in the sandstone, with planar fracture surfaces. The average width of the fractures is 3 μm. The fractures cut across all diagenetic cements and remain unfilled (

Figure 8h).

5. Discussion

5.1. Reservoir Pore Evolution

The He 1 Member sandstones have undergone intense diagenetic alteration including mechanical compaction, dissolution, and multiple cementation. Diagenetic sequences vary significantly across different types of sandstone reservoirs, ultimately controlling reservoir pore evolution (

Figure 10).

5.1.1. Type I Reservoir

At the onset of diagenesis, mechanical compaction induced minimal intergranular pores loss due to limited ductile grain deformation, preserving substantial primary intergranular pores. Localized pore loss occurred only where ductile grains were abundant. In eogenetic freshwater environments, alteration of volcanic rock fragments and minor volcanic ash matrix generated intragranular dissolution porosity and micropores, while simultaneously forming well-developed pore-lining chlorite. During mesogenesis, these chlorite cements inhibited quartz overgrowths through surface coverage mechanisms. Consequently, Type I reservoir exhibits coexisting intergranular and intragranular dissolution porosity with superior pore-throat connectivity.

5.1.2. Type II Reservoir

Early compaction induced ductile grain deformation that partially occluded intergranular pores, yet substantial primary intergranular pores persisted. During eogenesis, acidic freshwater fluids selectively dissolved detrital components. Volcanic lithics and volcanic ash matrix were altered to I/S mixed-layer clay and kaolinite. This dissolution generated intragranular pores and micropores. Due to abundant matrix content, pore-lining chlorite was poorly developed. During mesogenesis, extensive alteration of volcanic material released abundant silica, leading to widespread quartz overgrowth. Consequently, Type II reservoirs are dominated by isolated intragranular dissolution pores, resulting in poor pore connectivity.

5.1.3. Type III Reservoir

Throughout early diagenesis, severe mechanical compaction induced pervasive plastic deformation of ductile rock fragments, substantially reducing intergranular pores. With progressive burial and increasing temperature, volcanic rock fragments underwent alteration to form I/S mixed-layer clay. In mesogenesis, minor quartz overgrowths occluded residual intergranular pores. Syneresis of altered volcanic ash matrix generated microfractures. Ultimately, Type III reservoir exhibits pore systems dominated by micropores within clay matrix and volcanic rock fragments, resulting in poor pore connectivity.

5.2. The Relationship Between Volcanic Material and Dissolution

5.2.1. Dissolution Time

Within the diagenetic sequence, dissolution primarily preceded or was synchronous with quartz overgrowth cementation. Diagnostic evidence includes: (1) pervasive ductile grain deformation contemporaneous with dissolution and alteration; (2) partial occlusion of dissolution pores by quartz cement; (3) widespread quartz overgrowths enveloping dissolution residues (

Figure 8f); (4) late-diagenetic ferroan calcite infilling of dissolution pores.

5.2.2. Dissolution Material Sources

The He 1 Member sandstones contain volcanic constituents comprising: (1) volcanic rock fragments and (2) volcanic ash matrix. Volcanic rocks originated from provenance weathering. Southern basin provenance analysis identifies Paleoproterozoic Qinling Group and Mesoproterozoic-Neoproterozoic Kuanping Group as primary provenances. The Qinling Group comprises high-grade metamorphic rocks, whereas the Kuanping Group consists of low-grade metasediments derived from terrigenous clastics and basaltic volcanic rocks. This provenance is the primary reason for the ubiquitous occurrence of volcanic and low-grade metasedimentary lithics in He 1 Member sandstones. Moreover, varying proportions of synsedimentary intermediate- to felsic- volcanic ash matrix are present, and are altered to I/S mixed-layer clay during diagenesis.

5.2.3. Differential Dissolution Patterns

Certain volcanic and low-grade metasedimentary rock fragments exhibit ductile properties, undergoing pronounced plastic deformation during mechanical compaction that destroys intergranular pores and throats. When substantial intergranular porosity diminishes and throats close, diagenetic fluid mobility becomes restricted, thereby reducing dissolution efficiency. Even where dissolution occurred, the cessation of dissolution reactions was inevitable as reaction products could not be efficiently transported out of the reaction system.

Hence, moderate lithic content is a critical control on dissolution. Here, “moderate” denotes that rigid quartz grains form a framework, with lithic fragments dispersed among quartz grains. Under such conditions, even when ductile lithics undergo plastic deformation, they will not cause multiple throats to close simultaneously. Statistics confirm that when ductile grain content remains below 10%, deformation-induced pore-throat occlusion rates are maintained below 20%, thereby enhancing subsequent dissolution efficiency.

Volcanic ash matrix exhibits an analogous influence. When intergranular volcanic ash content is low, significant dissolution generates abundant secondary pores. Conversely, if volcanic ash matrix content is sufficiently high to pervasively infill intergranular pores, alteration yields micropores with negligible macropores observed.

Effective dissolution of volcanic materials requires sustained pore-water flux during diagenesis. This requires limited mechanical compaction to preserve intergranular pores and moderate clay matrix content within pores. Flume experiments demonstrate that platy lithic fragments are deposited under lower flow velocities [

26]. A considerable proportion of the platy rock fragments or minerals are ductile. As a result, lithic content increases with decreasing grain size. He 1 Member sandstones exhibit 14.6 vol.% lithic content in coarse sandstones versus 26.3 vol.% in fine sandstones on average. When the lithic content exceeds 20%, early mechanical compaction dramatically reduces intergranular porosity, hindering further dissolution. Petrographic studies show that coarse-grained sublithic sandstones formed in high-energy settings satisfy this requirement.

5.3. Controls on Quartz Overgrowth

5.3.1. Silica Sources for Quartz Overgrowths

The content of quartz overgrowths in the sandstones of the He 1 Member ranges from 0.2% to 8.3 vol.%, exhibiting significant variability. High contents of quartz cement require pore fluids that are rich in silica. In fluvial facies strata, the primary sources of silica include feldspar dissolution, pressure solution of quartz grains, and dissolution of volcanic materials [

23]. The He 1 Member sandstones are characteristically feldspar-poor, so feldspar dissolution is not the dominant silica source. Although mechanical compaction has induced significant ductile grain deformation, pressure dissolution of quartz grains remains limited, indicating that pressure dissolution is also not a major silica source. Both volcanic rock fragments and volcanic ash matrix in the sandstones are subjected to varying degrees of dissolution (

Figure 8d,e), generating substantial silica. The most pronounced silica cementation in the He 1 Member sandstones occurs in the southern basin, demonstrating a strong genetic linkage to a provenance enriched in volcanic lithics and abundant synsedimentary volcanic ash.

5.3.2. Chlorite Coatings Inhibiting Quartz Overgrowths

The inhibitory effect of pore-lining chlorite on quartz overgrowths has been extensively documented [

27,

28,

29]. Correspondingly, pore-lining chlorite provides an effective barrier for quartz cementation from the detrital surface into the pore space due to the high crystal interconnection in the He 1 Member sandstones (

Figure 8b). In sandstones with high primary intergranular pores, the absence of pore-lining chlorite would permit quartz overgrowth to completely occlude intergranular pores (

Figure 8f,h).

Pore-lining chlorite predominantly develops in sandstones with well-preserved intergranular pores, forming isopachous rims on grain surfaces. In sandstones enriched in ductile grains, however, early compaction induces grain deformation that occludes pore spaces, thus preventing the development of chlorite coating.

Chlorite formation requires substantial supplies of iron and magnesium, sourced primarily from the early diagenetic hydrolysis or dissolution of biotite, volcanic lithic fragments, and volcanic ash matrix within sandstones, which liberates these critical cations [

27]. During early diagenesis, clay mineral precursors on grain surfaces react with iron- and magnesium-enriched pore waters, initiating chlorite grain coatings [

29]. With ongoing diagenesis, chlorite progressively precipitates onto these coatings, ultimately developing into pore-lining chlorite, with crystal morphologies evolving from amorphous at grain contacts to euhedral terminations toward pore centers, demonstrating multi-stage growth. To form well-developed pore-lining chlorite, two essential conditions must be met. First, the intergranular porosity must be preserved during diagenesis to provide the necessary space for the continuous growth of the chlorite. Second, a sustained supply of iron ions and magnesium ions is required [

30].

5.4. Development Patterns of Conventional Reservoirs

The above analysis demonstrates that conventional reservoirs (partly Type I reservoirs) in tight sandstone exhibit four diagnostic diagenetic features: limited compaction, well-developed pore-lining chlorite, restricted quartz overgrowths, and enhanced dissolution. Sandstones simultaneously satisfying these criteria must be quartz-rich coarse- to granule-grained sublithic sandstones. Nevertheless, such quartz-rich sandstones do not invariably form conventional reservoirs. This needs to be discussed under two distinct scenarios.

Scenario 1: The coarse-grained sublithic sandstones formed in transverse bar microfacies occur as isolated sandbodies bounded by mudstone seals above and below (

Figure 11a). These sandstones exhibit low lithic content (<15 vol.%), with volcanic lithics averaging 6% and matrix content < 3%. Because ductile rock fragments are scarce, rigid grains preserve a significant portion of intergranular pores during compaction. Volcanic lithic dissolution generates both intragranular dissolution pores and moldic pores, while simultaneously releasing ferroan ions that precipitate pervasive pore-lining chlorite. The mudstone-sealed sandbodies function as a closed diagenetic system, restricting fluid exchange with external sources. Consequently, all dissolution and precipitation processes occur internally within the indigenous fluids. The relatively low volcanic lithic content yields limited dissolved silica, while pore-lining chlorite inhibits quartz overgrowth. This configuration represents a closed intrastratal-diagenetic system.

Scenario 2: The coarse-grained sublithic sandstones formed in transverse bar and lithic-rich sandstones of other genetic types occur as amalgamated sandbodies, lacking stable intervening mudstone seals (

Figure 11b). Within this configuration, extensive dissolution of volcanic lithics releases SiO

2-, Fe-, and Mg-enriched fluids that undergo vertical migration and diffusion between sandbodies. Lithic-rich laminated sandstones and longitudinal bar deposits are subjected to severe porosity losses due to ductile grain deformation during mechanical compaction. In contrast, sublithic sandstones formed in transverse bars maintain preserved intergranular pores through rigid grain support. Diagenetic alteration of volcanic material liberates substantial silica, which precipitates as quartz overgrowths where pore-lining chlorite is underdeveloped. During cementation, quartz overgrowths envelop clay, forming embayed grain boundaries. Consequently, sublithic sandstones formed in transverse bar develop only isolated intragranular dissolution pores with limited connectivity, while intergranular pores become occluded by quartz overgrowths. This configuration represents an open interstratal-diagenetic system.

6. Conclusions

(1) Conventional reservoirs (permeability > 1 mD) in braided fluvial tight sandstones of the He 1 Member in the southern Ordos Basin require a synergistic diagenetic assemblage comprising weak compaction, enhanced dissolution, and restricted quartz overgrowth. Weak compaction is enabled by a rigid quartz grain framework within coarse-grained sublithic sandstones, preserving substantial primary intergranular porosity. Enhanced dissolution predominantly occurs in volcanic lithic fragments and volcanic ash matrix, generating abundant intragranular dissolution pores and micropores. Continuous pore-lining chlorite inhibits quartz overgrowth, thereby preventing silica cements from occluding intergranular pores. The combined action of these three factors provides the essential conditions for the development of conventional reservoirs.

(2) Microfacies exert fundamental control on conventional reservoir development. Favorable reservoirs predominantly formed in transverse bars of braided channel deposits. This microfacies forms under high-energy hydrodynamic conditions and is dominated by medium to coarse-grained sublithic sandstones characterized by low lithic content and minimal matrix. When such bar sandbodies are vertically sealed by mudstones, they simultaneously facilitate limited early compaction and restrict influx of external silica-rich fluids. Under these conditions, transverse bars typically develop conventional reservoirs.

(3) The alteration and dissolution of volcanic constituents (volcanic lithic fragments and volcanic ash matrix) provide essential materials for conventional reservoir development. On one hand, their alteration generates clay minerals including I/S mixed-layer clay and chlorite clay, with pore-lining chlorite significantly inhibiting quartz overgrowth. On the other hand, silica liberated during dissolution supplies materials for quartz cementation. Critically, moderate volcanic material content (<10%) enables sustained dissolution that produces substantial secondary pores while preventing premature loss of intergranular pores from plastic deformation of ductile lithics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing-Review and Editing, X.D.; Conceptualization, Writing-Original Draft, Formal analysis, Y.W.; Visualization, Data Curation, Project administration, J.G.; Investigation, F.L.; Project administration, X.Z.; Software, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Financially supported by the Sinopec Science and Technology Research project (No. 34550000-24-ZC0611-0012).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VRF |

Volcanic rock fragment |

| MRF |

Metamorphic rock fragment |

| I/S |

Illite/smectite mixed layers |

| Chl |

Chlorite |

| F |

Fractures |

| Qo |

Quartz overgrowth |

| Aq |

Authigenic quartz |

| Fc |

Ferroan calcite |

| Sc |

Syneresis cracks |

| Kao |

Kaolinite |

| Mp |

Micropores |

| Q |

Quartz grain |

| Dp |

Dissolution pore |

| Mo |

Moldic pore |

| SEM |

Scanningelectronmicroscopy |

| HPMI |

High-pressure mercuryinjection |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| MICP |

Mercuryinjectioncapillary pressure |

References

- Fu, J.H.; Fan, L.Y.; Liu, X.S.; Hu, X.Y.; Li, J.H.; Ji, H.K. New Progress, Prospects, and Countermeasures for Natural-Gas Exploration in the Ordos Basin. Petroleum Exploration in China 2019, 24, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Z.; Guo, B.C.; Zheng, M.; Yang, T. Main Types, Geological Characteristics, and Resource Potential of Tight Sandstone Gas in China. Natural Gas Geoscience 2012, 23, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.G. Review and Prospect of the Development of China’s Natural Gas Industry. Natural Gas Industry 2021, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.L.; Wei, Y.S.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.T.; De, W.M.; Huang, S.Q. Development Status and Prospects of Tight Sandstone Gas in China. Natural Gas Industry 2022, 42, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.T.; Liu, X.P.; Jia, L.; Hu, J.L.; Lu, Z.X.; Zhou, G.X. Accumulation Patterns and Exploration Targets of Tight Sandstone Gas in the Low-Generation-Intensity Northern Tianhuan Depression, Ordos Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2021, 32, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.P.; Han, X.G.; Zhao, H.T.; Hu, J.L.; Jing, X.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Gas-Water Distribution Characteristics and Genetic Analysis of Tight Gas Reservoirs in the He 8 Member of the Ordos Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2023, 34, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H. 2020.

- Yang, H.; Fu, J.H.; Liu, X.S.; Meng, P.L. Accumulation Conditions and Exploration-Development of Tight Gas in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2012, 39, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.C.; Liu, J.F.; Guo, R.L.; Li, Y.L.; Yin, H.R.; Huang, X.Y.; Wang, F.Q. Development Characteristics and Controlling Factors of High-Quality Reservoirs in the He 8 Member, Southeastern Ordos Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2025, 36, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, L.; Wu, J. Study on the Diagenetic Evolution of Tight Sandstones in the Shanxi–Lower Shihezi Interval, Southern Ordos Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2021, 32, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.M.; Li, J.B.; Wang, Z.X.; Fan, A.P.; Gao, W.L.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, Y. Reservoir Characteristics of Tight Sandstones at a Braided-River Delta Front and Controls on High-Quality Reservoirs: A Case Study of the 8th Member of the Shihezi Formation, Southwestern Sulige Gas Field. Acta Petrolei Sinica 2019, 40, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, F.Q.; Zhang, W.; An, C.; He, Y.J.; Zhu, M.L.; Ai, X.Y. Dynamic Evaluation of the Tight Sandstone Reservoir in He 1 Member, Northern Ordos Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2024, 35, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qu, X.Y.; Qiu, L.W.; Zhang, L.Q. Petrophysical Properties and Diagenetic Key Controls of Upper Paleozoic Tight Sandstone Reservoirs in Well D18, Daniudi Gas Field. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2016, 34, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.Y.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, Q. Impact of Chlorite Coatings on Clastic Reservoir Properties and Their Forming Environment: A Case Study of the Upper Paleozoic in the Daniudi Gas Field, Ordos Basin. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2015, 33, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tian, J.C.; Chen, R.; Li, M.R.; Xiao, L. Reservoir Characteristics and Controlling Factors of the He 8 Member in the Upper Paleozoic of Northern Ordos Basin. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2009, 27, 238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.L.; Liu, X.S.; Fu, X.Y.; Li, M.; Kang, R.; Jia, Y.N. Influence of Petrological Composition and Diagenetic Evolution on the Reservoir Quality and Productivity of Tight Sandstones: A Case Study of the He 8 Gas Reservoir in the Upper Paleozoic of the Ordos Basin. Journal of Earth Science 2014, 39, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Luo, J.L.; Li, W.H.; Wang, R.G. Genesis of Low Permeability and Formation Mechanism of High-Quality Reservoirs in the Lower Sub-Member of the He 8 Tight Sandstone, Block Su 77, Ordos Basin. Geological Science and Technology Information 2018, 37, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Ma, Z.J.; Han, D.; Wang, H.Y.; Ma, L.T.; Ge, D.S. Key Controlling Factors for the Formation of High-Quality Tight-Sandstone Reservoirs in the Linxing Block, Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin. Natural Gas Geoscience 2018, 29, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Lan, C.L. Distribution of Fractures and Faults in the Upper Paleozoic of the Yulin–Shenmu Area, Ordos Basin, and Their Influence on Natural-Gas Enrichment Zones. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2006, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.F.; Bao, H.P.; Kai, B.Z.; Wei, L.B.; Xv, Y.H.; Ma, J.H.; Cheng, X. Critical tectonic modification periods and its geologic features of Ordos Basin and adjacent area. 2021, 42, 1255-1269. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; Liu, H.J.; Quan, B.; Wang, Z.C.; Qian, K. Late Paleozoic Sedimentary System and PaleogeographicEvolution of Ordos Area. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 1998, 16, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L.; Andrews, P.B.; Lewis, D.W. Detrital sedimentary rock classification and nomenclature for use in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 1970, 13, 937–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.E. Sedimentary petrology (4th edn), Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023, pp.

- Liu, X.; Ding, X.Q.; Hersi, O.S.; Han, M.M.; Zhu, Y. Sedimentary facies and reservoir characteristics of the Western Sulige field Permian He 8 tight sandstones, Ordos Basin, China. Geological Journal 2020, 55, 7818–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Q.; Hersi, O.S.; Hu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.N.; Miao, C.S. Diagenesis of volcanic-rich tight sandstones and conglomerates: a case study from Cretaceous Yingcheng Formation, Changling Sag, Songliao Basin, China. Arabian Journal of Geosciences 2018, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G. Sedimentology and Stratigraphy, Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2009, pp. 419.

- Berger, A.; Gier, S.; Krois, P. Porosity-preserving chlorite cements in shallow-marine volcaniclastic sandstones: Evidence from Cretaceous sandstones of the Sawan gas field, Pakistan. Aapg Bulletin 2009, 93, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, S.N. Preservation of Anomalously High Porosity in Deeply Buried Sandstones by Grain-Coating Chlorite: Examples from the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Aapg Bulletin 1993, 77, 1260–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H.; Griffiths, J.; Wooldridge, L.J.; Utley, J.E.P.; Lawan, A.Y.; Muhammed, D.D.; Simon, N.; Armitage, P.J. Chlorite in sandstones. Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 204, 103105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Q.; Zhang, S.N.; Ge, P.L.; Yi, C. Diagenetic System of the Yanchang Formation Reservoirs in the Southeastern Ordos Basin. Acta Sedimentologica Sinica 2011, 29, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the study area and stratigraphic column of He 1 Member.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the study area and stratigraphic column of He 1 Member.

Figure 2.

Sedimentary microfacies and physical properties of He 1 Member of Well R 6.

Figure 2.

Sedimentary microfacies and physical properties of He 1 Member of Well R 6.

Figure 3.

Core photographs showing representative lithofacies of the He 1 Member: (a) Light gray, massive-bedded, normally graded pebbly coarse sandstone with poorly sorted but well-rounded pebbles, Well XF8, 2897.23 m; (b) Light gray, massive-bedded, fine-to-medium pebble conglomerate containing poorly sorted, well-rounded pebbles (3 mm to 2 cm diameter), Well R6, 2970.03 m; (c) Light gray, planar cross-bedded, coarse sandstone containing granules with poor sorting and rounding, Well R7, 3155.43 m; (d) Gray, horizontally laminated fine sandstone exhibiting abundant argillaceous laminae, Well R602, 3017.82 m.

Figure 3.

Core photographs showing representative lithofacies of the He 1 Member: (a) Light gray, massive-bedded, normally graded pebbly coarse sandstone with poorly sorted but well-rounded pebbles, Well XF8, 2897.23 m; (b) Light gray, massive-bedded, fine-to-medium pebble conglomerate containing poorly sorted, well-rounded pebbles (3 mm to 2 cm diameter), Well R6, 2970.03 m; (c) Light gray, planar cross-bedded, coarse sandstone containing granules with poor sorting and rounding, Well R7, 3155.43 m; (d) Gray, horizontally laminated fine sandstone exhibiting abundant argillaceous laminae, Well R602, 3017.82 m.

Figure 4.

Plot of porosity versus permeability for the four types of sedimentary microfacies.

Figure 4.

Plot of porosity versus permeability for the four types of sedimentary microfacies.

Figure 5.

Pore types of the four types of sedimentary microfacies of the He 1 Member.

Figure 5.

Pore types of the four types of sedimentary microfacies of the He 1 Member.

Figure 6.

Throat radius distribution of the three types of reservoirs.

Figure 6.

Throat radius distribution of the three types of reservoirs.

Figure 7.

Quartz-feldspar-lithic fragment (Q-F-L) ternary diagram showing composition of the three types of reservoirs from the He 1 Member. Classification after Folk [

22].

Figure 7.

Quartz-feldspar-lithic fragment (Q-F-L) ternary diagram showing composition of the three types of reservoirs from the He 1 Member. Classification after Folk [

22].

Figure 8.

Optical photomicrographs of He 1 Member sandstone: (a) Ductile metamorphic rock fragments deformed during compaction showing concave-convex contacts, and negligible porosity, Well XF15-P4, 3180.14 m (SEM); (b) Point and long grain contacts with pore-lining chlorite and intergranular porosity; quartz overgrowths occur where pore-lining chlorite is absent, featuring a dissolution pore at right, Well R7, 3158.62 m (PPL); (c) Micropores within volcanic ash matrix, exhibiting desiccation cracks formed by diagenetic dehydration, Well XF5, 2695.51 m (PPL); (d) Intragranular dissolution pores in volcanic lithics containing flaky illite clays, Well XF15-P1, 3087.54 m (PPL); (e) Authigenic illite-smectite mixed-layer clay, kaolinite, and microquartz precipitated from volcanic lithic dissolution, Well XF5, 2695.51 m (SEM); (f) Quartz overgrowths with embayed boundaries containing clay inclusions and dust rims at crystal interfaces, Well XF3, 2696.08 m (PPL); (g) Ferroan calcite cements replacing lithics, volcanic ash matrix infilling pores, and authigenic quartz occurring in residual spaces, Well XF8, 2898.82 m (PPL); (h) Subparallel shear fractures transecting grains and cements with no mineral infilling, Well XF12, 2866.55 m (PPL). VRF: volcanic rock fragments; MRF: metamorphic rock fragments; I/S: illite/smectite mixed layers; Chl: chlorite; F: fractures; Qo: quartz overgrowths; Aq: authigenic quartz; Fc: ferroan calcite; Sc: syneresis cracks; Kao: kaolinite; Mp: moldic pore.

Figure 8.

Optical photomicrographs of He 1 Member sandstone: (a) Ductile metamorphic rock fragments deformed during compaction showing concave-convex contacts, and negligible porosity, Well XF15-P4, 3180.14 m (SEM); (b) Point and long grain contacts with pore-lining chlorite and intergranular porosity; quartz overgrowths occur where pore-lining chlorite is absent, featuring a dissolution pore at right, Well R7, 3158.62 m (PPL); (c) Micropores within volcanic ash matrix, exhibiting desiccation cracks formed by diagenetic dehydration, Well XF5, 2695.51 m (PPL); (d) Intragranular dissolution pores in volcanic lithics containing flaky illite clays, Well XF15-P1, 3087.54 m (PPL); (e) Authigenic illite-smectite mixed-layer clay, kaolinite, and microquartz precipitated from volcanic lithic dissolution, Well XF5, 2695.51 m (SEM); (f) Quartz overgrowths with embayed boundaries containing clay inclusions and dust rims at crystal interfaces, Well XF3, 2696.08 m (PPL); (g) Ferroan calcite cements replacing lithics, volcanic ash matrix infilling pores, and authigenic quartz occurring in residual spaces, Well XF8, 2898.82 m (PPL); (h) Subparallel shear fractures transecting grains and cements with no mineral infilling, Well XF12, 2866.55 m (PPL). VRF: volcanic rock fragments; MRF: metamorphic rock fragments; I/S: illite/smectite mixed layers; Chl: chlorite; F: fractures; Qo: quartz overgrowths; Aq: authigenic quartz; Fc: ferroan calcite; Sc: syneresis cracks; Kao: kaolinite; Mp: moldic pore.

Figure 9.

Plot of intergranular volume (IGV) versus cementation and compaction of different types of sandstone.

Figure 9.

Plot of intergranular volume (IGV) versus cementation and compaction of different types of sandstone.

Figure 10.

Sandstone pore evolution of He 1 sandstone reservoir. Q: Quartz grain; VRF: Volcanic rock fragment; MRF: Metamorphic rock fragment; Chl: Chlorite; Qo: Quartz overgrowth; Kao: Kaolinite; Dp: Dissolution pore; Mo: Moldic pore; Mp: Micropore.

Figure 10.

Sandstone pore evolution of He 1 sandstone reservoir. Q: Quartz grain; VRF: Volcanic rock fragment; MRF: Metamorphic rock fragment; Chl: Chlorite; Qo: Quartz overgrowth; Kao: Kaolinite; Dp: Dissolution pore; Mo: Moldic pore; Mp: Micropore.

Figure 11.

Reservoir formation mechanism of the He 1 member sandstones. (a) Transverse bar sandbodies are sealed above and below by mudstones, so diagenesis is confined entirely within the sandbodies, resulting in Type I Reservoirs. (b) Where transverse bar, longitudinal bar, and laminated sandstones are vertically amalgamated, interstitial pore waters can carry ions among different sandbodies. The large amount of silica released by dissolution of volcanic material in longitudinal bars and laminated sandstones can migrate into the transverse bars, producing abundant quartz overgrowths. Under these conditions, Type I Reservoirs do not develop within the transverse bars.

Figure 11.

Reservoir formation mechanism of the He 1 member sandstones. (a) Transverse bar sandbodies are sealed above and below by mudstones, so diagenesis is confined entirely within the sandbodies, resulting in Type I Reservoirs. (b) Where transverse bar, longitudinal bar, and laminated sandstones are vertically amalgamated, interstitial pore waters can carry ions among different sandbodies. The large amount of silica released by dissolution of volcanic material in longitudinal bars and laminated sandstones can migrate into the transverse bars, producing abundant quartz overgrowths. Under these conditions, Type I Reservoirs do not develop within the transverse bars.

Table 1.

Statistical summary of the petrographic parameters of He 1 Member sandstones.

Table 1.

Statistical summary of the petrographic parameters of He 1 Member sandstones.

| Components |

Type I reservoir (n=18) |

Type II reservoir (n=21) |

Type III reservoir (n=19) |

| Max,% |

Min,% |

Aver,% |

Max,% |

Min,% |

Aver,% |

Max,% |

Min,% |

Aver,% |

| Fragmentts |

Quartz |

90.6 |

66.5 |

71.6 |

87.9 |

50.5 |

69.9 |

75.86 |

46.3 |

63.6 |

| Feldspar |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

2.7 |

0.0 |

1.6 |

4.8 |

0.0 |

2.3 |

| Volcanic rock fragment |

7.7 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

8.7 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

10.6 |

3.1 |

4.4 |

| Metamorphic rock fragment |

16.2 |

7.9 |

12.5 |

24.6 |

5.6 |

16.8 |

35.2 |

12.2 |

17.8 |

| Mica |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

2.7 |

0.0 |

0.6 |

6.2 |

1.3 |

4.1 |

| Cements |

Calcite |

4.8 |

0.0 |

1.2 |

5.6 |

0.4 |

2.2 |

10.3 |

0.4 |

2.3 |

| Chlorite |

8.4 |

3.5 |

5.6 |

6.7 |

2.2 |

3.5 |

2.1 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

| Illite |

1.8 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

4.2 |

0.3 |

2.4 |

5.3 |

0.2 |

3.5 |

| Kaolinite |

1.8 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

3.1 |

0.0 |

1.6 |

| Quartz overgrowth |

2.1 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

8.3 |

0.6 |

4.1 |

3.3 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).