1. Introduction

The Constitution of India serves as an indispensable basis for democracy and provides the dignity, freedom and equality of citizens through a series of Fundamental Rights. Fundamental Rights, located in Part III of the Constitution, establish civil liberties, including the right to freedom of speech and expression; the right to equality before the law - and protection from exploitation; respectively. Fundamental Rights are intended to enable people to live where they have access to justice and security. While they are not simply rights in law, the Rights are encouraged, and intended to be a continuing way to engage with democracy, but also to strive for the equal right of citizens to justice and opportunity regardless of their social, economic and cultural situation (Basu, 2015; Jain, 2013).

1.1. Barriers to Realization

Despite being constitutionally guaranteed rights, Fundamental Rights are often not fully available or are underused in practice. For instance, illiteracy and poverty, gender and caste discrimination, lack of knowledge of the law, and most importantly, the delay caused by bureaucracy in the courts mean that large sectors of the population are unable to fully enjoy these rights (Singh, 2021; Sharma, 2022). In particular, it is extremely difficult for underprivileged people to contest their claims or realize their rights to access entitlements, and therefore, the difference between the principles of the Constitution and reality is widening. These constraints undermine democracy's promises for equality and freedom, and consider issues of access equally important as the Rights themselves.

1.2. Research Gap

Although the quantity of literature that focuses on the constitutionally enshrined architecture of the Fundamental Rights is significant, the amount of literature that focuses on how citizens navigate and experience rights through practice within their everyday lives is extremely limited. In particular, the literature has focused mainly on legal provisions, landmark judgements, or theoretical discussions, and does not often examine the level of public awareness of rights, and physical barriers to accessing rights when looking at different social groups. These gaps are particularly relevant to the present situation in India whereby democracy is not just a matter of rights written into law, but more about people’s ability to understand and implement them

1.3. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to address this gap by examining citizens's awareness of, and access to, Fundamental Rights outlined in the Constitution. In particular, it examines how aware citizens are of their rights, what are the factors that inhibit them from availing them, and How can we increase people's awareness and access to them. The study will attempt to bridge constitutional theory with lived experience, and also provide actionable suggestions to enable a more participatory and operational approach to rights in the contemporary context in India.

2. Objectives of the Research

- 2.1.

To understand the meaning and importance of Fundamental Rights as guaranteed by the Indian Constitution.

- 2.2.

To examine the gap between the constitutional guarantee and practical implementation of these rights in daily life.

- 2.3.

To identify key challenges such as lack of awareness, social inequality, and legal delays that affect the enforcement of these rights.

- 2.4.

To highlight real-life examples or situations where Fundamental Rights were denied or violated.

- 2.5.

To propose simple and practical solutions that can help make Fundamental Rights more effective and accessible to all citizens.

3. Review of Literature

In order to understand how Fundamental Rights are viewed, accessed, and implemented in India, various streams of literature were reviewed. The review encompasses constitutional literature, learned articles, judicial decisions, textbooks, and empirical research.

3.1. Constitutional Provisions and Legal Framework

The Indian Constitution’s Part III (Articles 12–35) lays down Fundamental Rights, entrenched rights that are legally enforceable entitlements and that limit arbitrariness of state actions, guaranteeing individual and citizen freedoms. Articles 32 and 226 have remedies so that the rights are justiciable; citizens can go directly to the Supreme Court or the High Courts. According to constitutional historians, this provision remains the most characteristically Indian feature of its democracy and stands in stark contrast to many of the post-colonial constitutions (Austin, G., 1999).

3.2. Scholarly Interpretations

Prominent constitutional scholars have emphasized that the moral and legal foundation of Indian democracy is comprised of Fundamental Rights. (M. P. Jain, 2013) refers to them as the "cornerstone of constitutionalism," guaranteeing that state power remains answerable to restraints. (D. D. Basu, 2015) presents them as means to uphold human dignity and achieve equilibrium between individual freedom and state accountability. (H. M. Seervai, 2013) seconded this opinion, with the contention that enforceability of rights renders them a necessary aspect of democratic participation and minority protection.

3.3. Awareness of Civic and Educational Rights

Concerns about fundamental rights begin in schools. NCERT civics textbooks introduce students to concepts such as equality, freedom and freedom from being exploited through storytelling and lessons in the classroom, thus making constitutional concepts less abstruse (NCERT, 2020). However, (Anil Kumar, 2017) points out that this knowledge is limited to school-age children and does not apply to larger segments of society, such as early school leavers, who are unaware of their legal rights. According to (R.Pathak, 2021), there are insufficient civic literacy initiatives outside of public formal education that bridge the gap between civic poverty and legal entitlements.

3.4. Judicial Interpretation and Landmark Cases

Over the decades, the Indian judiciary has steadily broadened the benchmarks and safeguards of fundamental rights. As stated in the 1973 decision of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, these rights compose part of the Constitution's "basic structure" which cannot be changed, repealed or suspended by Parliament (Supreme Court of India, 1973). In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) the Supreme Court located a wide interpretation of Article 21 which not only encompassed survival, but dignity, autonomy, and reasonableness in the exercise of State power (Supreme Court of India, 1978). As (Seervai, 2013) indicates, these judgments highlight the fact that the judiciary has transformed Fundamental Rights from 'clauses' to 'dynamic provisions' in the Constitution.

3.5. Social Realities and Media Reports

Even as the legal system is strong, lived experiences have a different tale to tell. Singh (2021) identifies that caste-based discrimination and economic disparity continue to hinder the equal enjoyment of rights in rural India (Singh, 2021). Media news resonate similarly: the Hathras case of 2020 exposed how gender and caste prejudice undermined the Right to Equality and the Right to Life, while the story of migrant workers under COVID-19 lockdown laid bare the vulnerability of the Right to Livelihood and Dignity (Sharma, P., 2022). These stories highlight that mere awareness is not enough, systemic hurdles still withhold rights from marginalized communities.

3.6. Summary of Literature

In particular, the combined readings develop an irony; India has one of the strongest constitutional systems of rights protection, but has many obstacles to accessibility and awareness. The readings suggest that in practice, schools and the courts are likely to support rights, although they will be behaving in a context of socioeconomic clarification and poor civic engagement. The readings recommend more civic education, critical awareness campaigns, and systemic reform to reduce the difference between constitutional principle and practice (D. D.Basu, 2015; R. K.Singh, 2021).

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design

The research used a mixed method design, which included a survey for numbers and trends, but also interviews, to learn about lived experiences. The survey allowed us to understand the awareness levels by age groups, while the interviews of domestic workers provided information on how marginalised people make sense of and access their rights.

4.2. Population and Sampling

Survey Group: We had responses from about 70 people, including both students and adults from Gurgaon, and gave us a representation of more than just one age group. The survey link was distributed via WhatsApp, class forums, and through personal networks, so it was convenience sampling.

Interview Group: We interviewed 10 domestic workers (or house helps), individuals from the sample population due to their socio-economic status, will likely not be able to participate in formal civic education which makes their views especially useful. The creation of this group was a type of purposive sampling (selecting them on purpose because of their status).

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents by age.

Figure 1.

Distribution of respondents by age.

4.3. Research Instruments

Survey (Google Forms): The survey questions were:

Familiarity with Fundamental Rights ("Can you name one?")

First source of knowlege (school, family, media, peers).

Perceptions about access ("Do all citizens have equal access to Rights?")

Barriers faced (poverty, illiteracy, stigma, delays).

Rank the most important right today.

Suggestions for improving familiarity.

Interviews (Semi-structured): we followed up with short, simple questions in Hindi/English depending on their comfort level, e.g.,

"Have you heard about Fundamental Rights?"

"Where did you learn about them?'

"Do you think you could use these rights if you needed to?"

"What issues stop you from using your rights?"

4.4. Data Collection

Survey was conducted virtually during July 2025. Of the 70 respondents, most were students, but almost a quarter were working adults.

Interviews: we conducted in-person interviews with 10 domestic workers. We explained the study to participants in simplified language; obtained verbal consent, and provided anonymity for all responses. Many stated they had little or no knowledge of their rights, and several indicated they had only heard of them on TV or from an employer.

4.5. Data Analysis

Survey data: The responses were analyzed using percentages and graphs to show levels of awareness about, sources of information, and barriers to knowledge about, ILO convention.

Interview data: The responses were analysed using descriptive codes based on themes, such as:

Low awareness — "We don't know the details about our rights."

Dependence on others — "If we have a problem, we get our employer to help us."

Barriers — "Even if we know something wrong is happening, we don't know where to complain to."

The study was able to make three-way comparisons between students, adults and domestic workers, enabling comparisons across age and social groups. This coverage of the educated class, supports awareness but for the marginalised sections, practical access is thin.

5. Results and Analysis

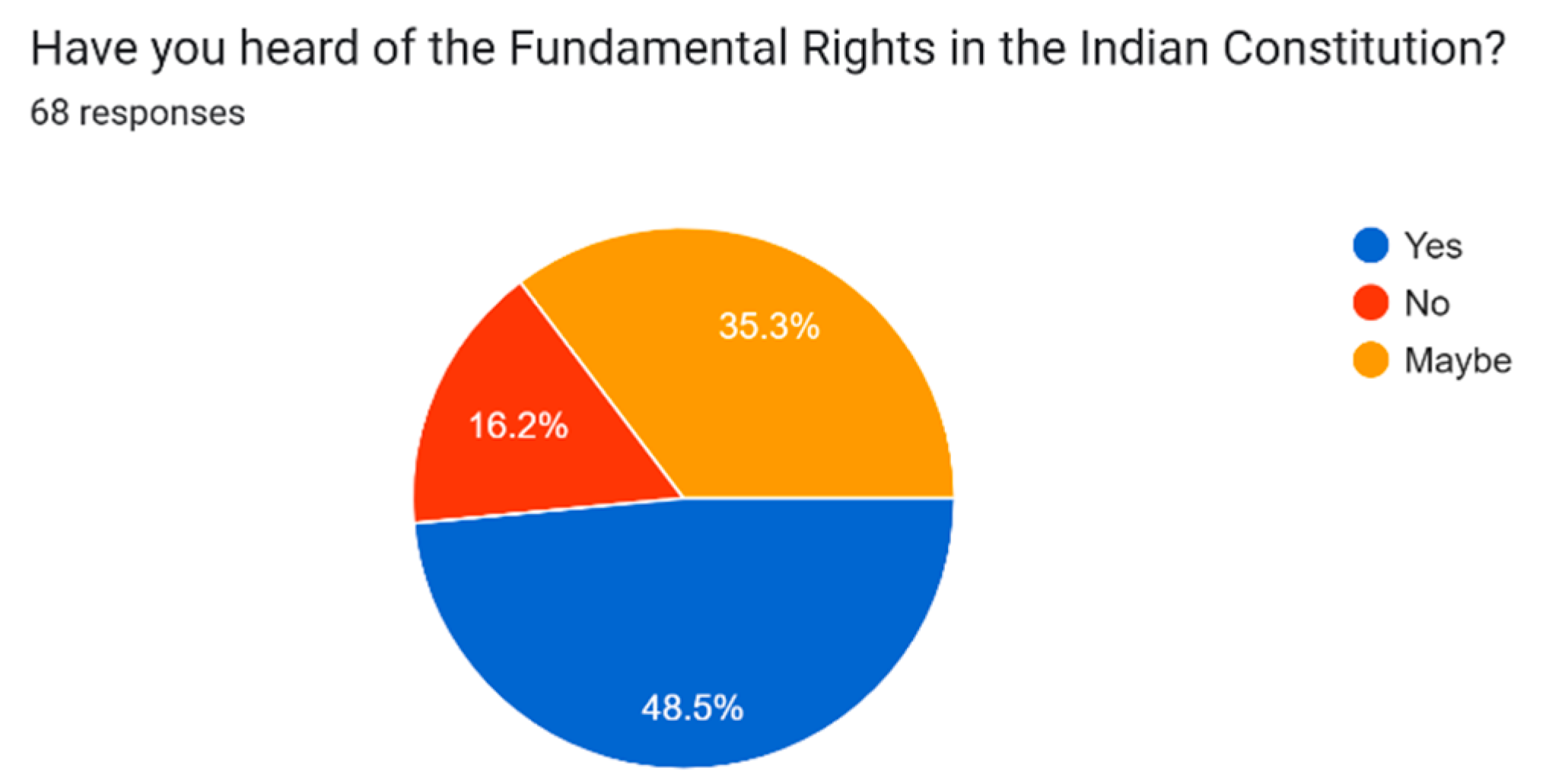

5.1. Awareness of Fundamental Rights

Throughout the survey, nearly 80% of all respondents (students + adults) indicated that they had heard of Fundamental Rights. But when prompted to identify one of the rights correctly, only around 50% managed to do so. The Right to Equality and the Right to Freedom of Speech were the most commonly cited. This indicates that people might have heard of the term, but their level of understanding is shallow.

Interviews with the domestic workers showed a far more biting contrast. Of the 10 workers, there were only 3 who had even heard of the term "Fundamental Rights." The others claimed never to have heard of it or got it mixed up with other general government schemes such as ration cards or health subsidy.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents aware vs. unaware of Fundamental Rights.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents aware vs. unaware of Fundamental Rights.

5.2. Sources of Knowledge

From the survey:

Students: The majority (65%) reported school education as their initial source of information. Social media (10%), and family/friends (5%) ranked second and third, respectively.

Adults: A large portion, identified newspapers and television as their initial exposure, while some attributed it to workplace discussions or neighbourhood discussions.

Domestic workers (interviews): The majority confessed they never learned about rights at school because they had dropped out early. Some claimed to have gotten information about rights from employers or on TV news, but with very little concept of what they really meant.

Figure 3.

Respondents’ primary sources of information about Fundamental Rights.

Figure 3.

Respondents’ primary sources of information about Fundamental Rights.

5.3. Perceptions of Accessibility

When asked if rights are accessible to all on an equal basis:

Students and adults (questionnaire): 50% agreed, 30% disagreed, and 20% did not know. This breakdown indicates uncertainty regarding how rights operate in real life.

Domestic workers (interviews): The majority reported that they did not feel they could enforce rights if something went wrong. One worker commented, "Even when something is not fair, we don't know where to go or who will hear us." This indicates the distance between constitutional promise and everyday life.

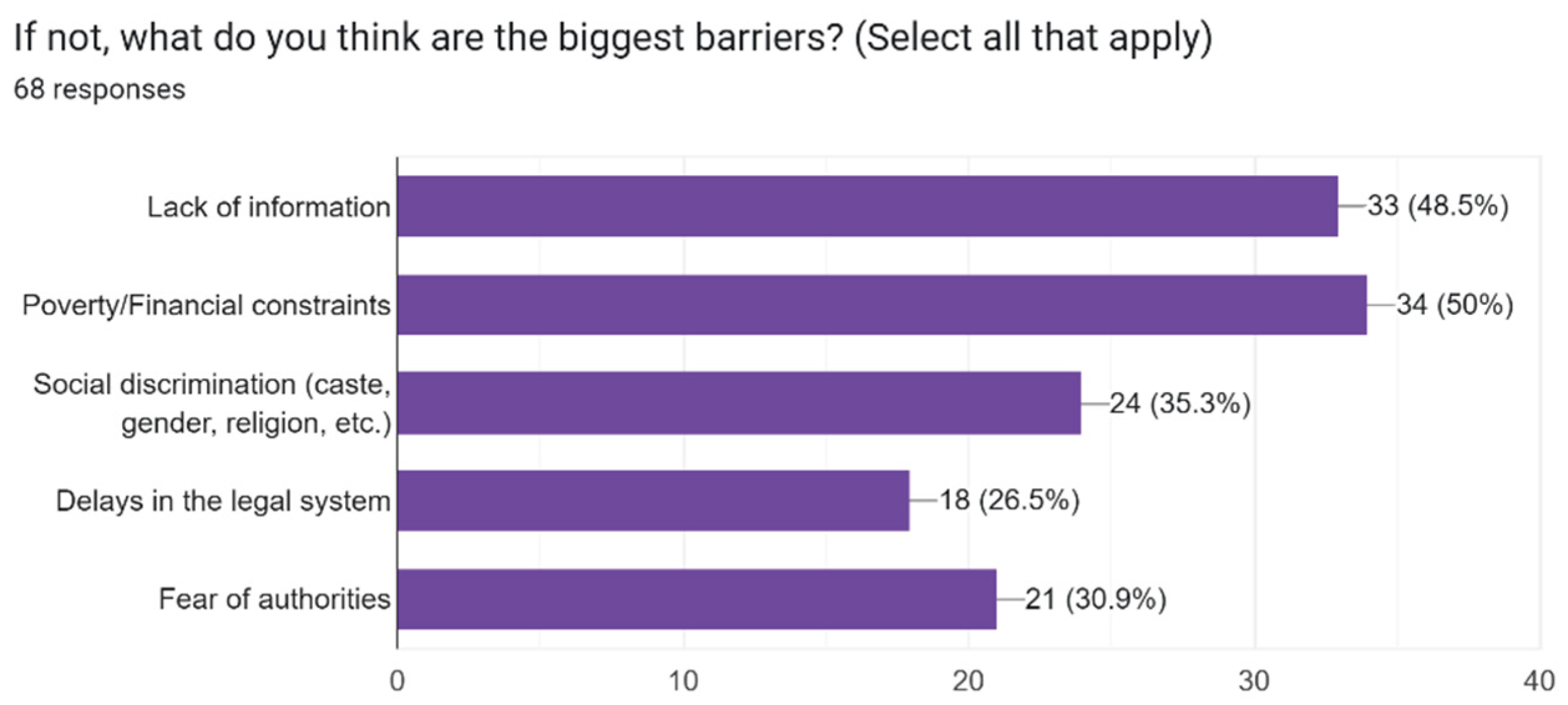

5.4. Exercising Rights Barriers

The following were cited by survey respondents as the main barriers:

Domestic workers affirmatively confirmed the barriers. A number of them said illiteracy and poverty prevent them from knowing what their rights are or visiting formal institutions. Many of them also cited dependence on employers, they depend on their employers to assist them in times of need instead of turning to formal institutions.

Figure 4.

Common challenges faced by respondents in exercising their Fundamental Rights.

Figure 4.

Common challenges faced by respondents in exercising their Fundamental Rights.

5.5. Most Significant Right Now

On being asked to pick the most significant right in the world today:

42% of the students and adults combined chose the Right to Equality.

28% chose the Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression.

Significantly fewer chose rights such as the Right against Exploitation or Right to Constitutional Remedies.

For migrant workers, this was a more abstract question. Some replied that "equality" sounded most crucial, but most said they didn't really know what each of the rights represented. This is once more indicative of the divide between awareness among educated citizens and marginalized communities.

6. Recommendations to Bridge the Gap

According to the survey, a number of steps can be suggested to enhance awareness and accessibility of Fundamental Rights:

6.1. Enhancing Civic Education

As most respondents had initially been introduced to Fundamental Rights through school, the educational system has to step up. Civic education has to go beyond reading from textbooks to incorporate:

Case studies on violation of rights and redressal.

Simulation sessions on legal aid or class debates.

Inclusion of Fundamental Rights consciousness in extracurricular activities.

6.2. Broadening Awareness Outside Schools

Nearly one-fourth of the respondents indicated that their first awareness of this event came from family, friends or social media. This indicates the need for wider awareness campaigns within the community such as:

Television, radio and social media campaigns.

Community initiatives at the grass roots level - with special attention to parents and rural audiences.

Have partnerships with NGOs who can access more marginalized groups.

In rural areas, Panchayats or Sarpanches should be educated with these rights and their working and given the responsibility to pass that information to there followers.

6.3. Breaking Down Structural Barriers

The most frequently mentioned obstacles were poverty, illiteracy, and ignorance. To meet these:

Improve free and accessible legal aid infrastructure at the district and block levels.

Increase literacy and computer education schemes incorporating awareness about rights.

Streamline legal processes and minimize bureaucratic delays in the access to remedies.

6.4. Initiatives for Youth Involvement

Since the survey involved young respondents, it is essential that their future role as citizens be highlighted. Recommended initiatives are:

National youth workshops on Basic Rights.

Student initiative campaigns on equality and freedom of expression.

Online forums where youths can post experiences of practicing their rights.

7. Conclusion

This study attempted to examine the knowledge and accessibility of Fundamental Rights for different parts of society. The findings made one thing clear: there was a big gap between what the Constitution provides and what people lived.

From the survey conducted with children and adults, we found that most people had heard about Fundamental Rights, but had little to no in-depth knowledge or understanding. Students identified schools as the main source of their knowledge, while adults most often reported televisions, newspapers (including articles), and social media. Interviews with the domestic workers indicated that this marginalized community had very low awareness. A majority of them confused rights with government welfare schemes and did not acknowledge any avenue to ask for their rights if something went wrong.

The barriers: poverty, illiteracy, ignorance, social discrimination, and biased judicial systems, make it clear, the rights listed in the Constitution are not enough. Unless people are aware of and able to avail themselves of these rights, they are merely ink on paper.

Our recommendations outlines a pathway: practically implement civic education into schools; use panchayats and local village leaders to promote awareness in villages; create media and social media campaigns with easy to understand language; implement easy access legal aid systems; conduct community workshops; and utilize youth for awareness sharing. All of these steps will assist in bridging the gap between law and practice.

In summary, it is not enough to have a constitution, what differentiates a strong democracy from a weak one is the extent to which the citizens are able to use their constitution. For India, it will be a challenge to ensure Fundamental Rights are not for the educated or upper class, but for all citizens - poor or rich, rural or urban, young or old, only then, will the Constitution fulfil its potential of providing equality, justice, and freedom for all.

References

- Amnesty International India. (2020). Know your rights: A handbook on fundamental rights in India. Amnesty International.

- Austin, G. (1999). Working a democratic constitution: The Indian experience. Oxford University Press.

- Basu, D. D. (2015). Introduction to the Constitution of India (22nd ed.). LexisNexis.

- Jain, M. P. (2013). Indian constitutional law (7th ed.). LexisNexis.

- Kumar, A. (2017). Civic literacy and legal awareness: A study on India. Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 12(3), 45–58.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training. (2020). Democratic politics (NCERT Civics textbooks, Classes 8–10). Government of India.

- NITI Aayog. (2018). Strategy for New India @ 75. Government of India.

- Pathak, R. (2021). Bridging the civic literacy gap in India: Challenges and opportunities. Indian Journal of Civic Studies, 15(2), 101–119.

- Seervai, H. M. (2013). Constitutional law of India (4th ed.). Universal Law Publishing.

- Sharma, P. (2022). Rights in crisis: COVID-19 and the migrant worker experience. Economic and Political Weekly, 57(12), 23–29.

- Singh, R. K. (2021). Social realities of rights in rural India. Indian Journal of Law and Society, 8(1), 55–73.

- Supreme Court of India. (1973). Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, AIR 1973 SC 1461.

- Supreme Court of India. (1978). Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, AIR 1978 SC 597.

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights (UDHR). https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).