Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

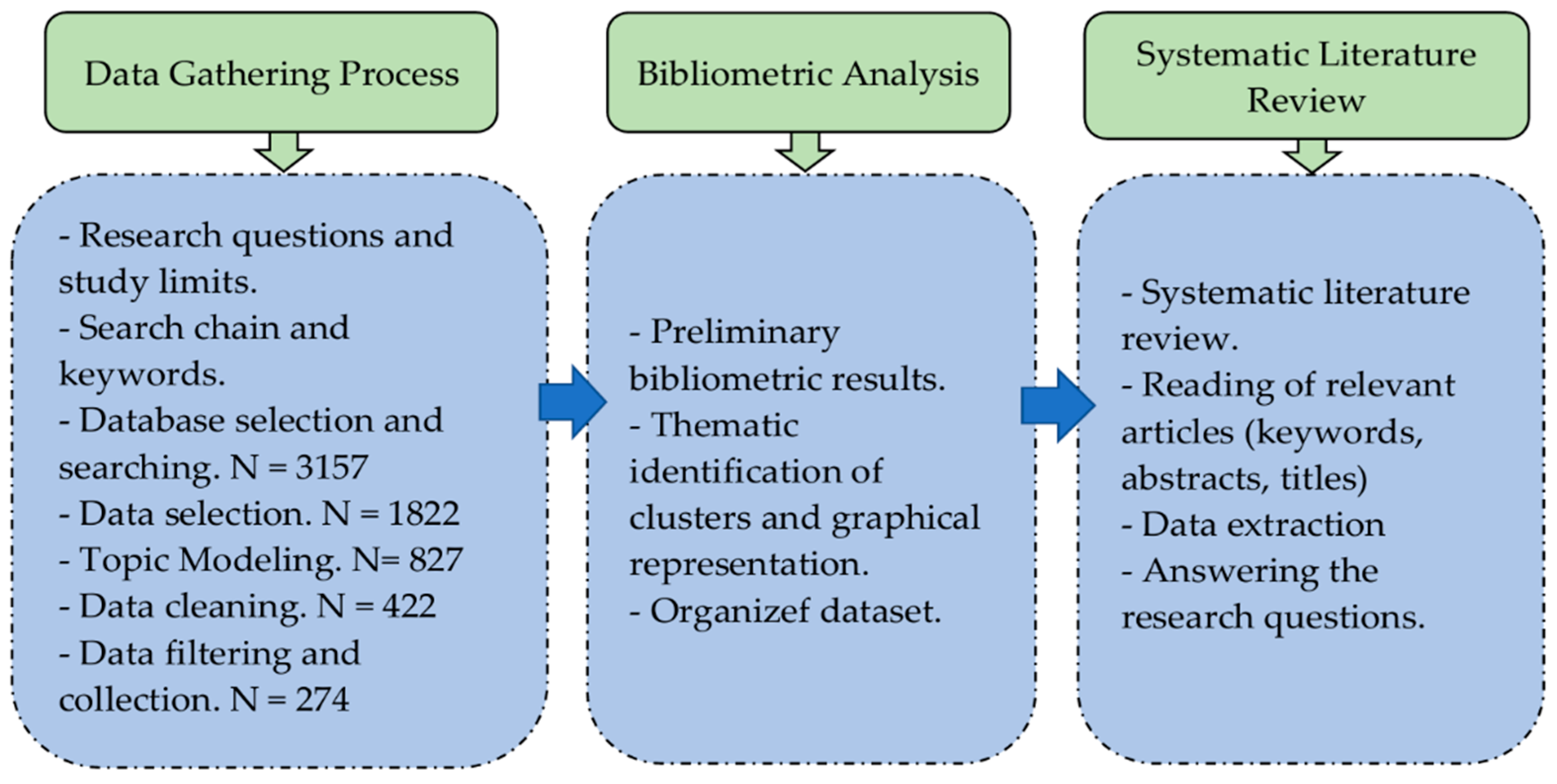

2.1. Data Gathering Process

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis (BA)

2.3. Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

3. Results

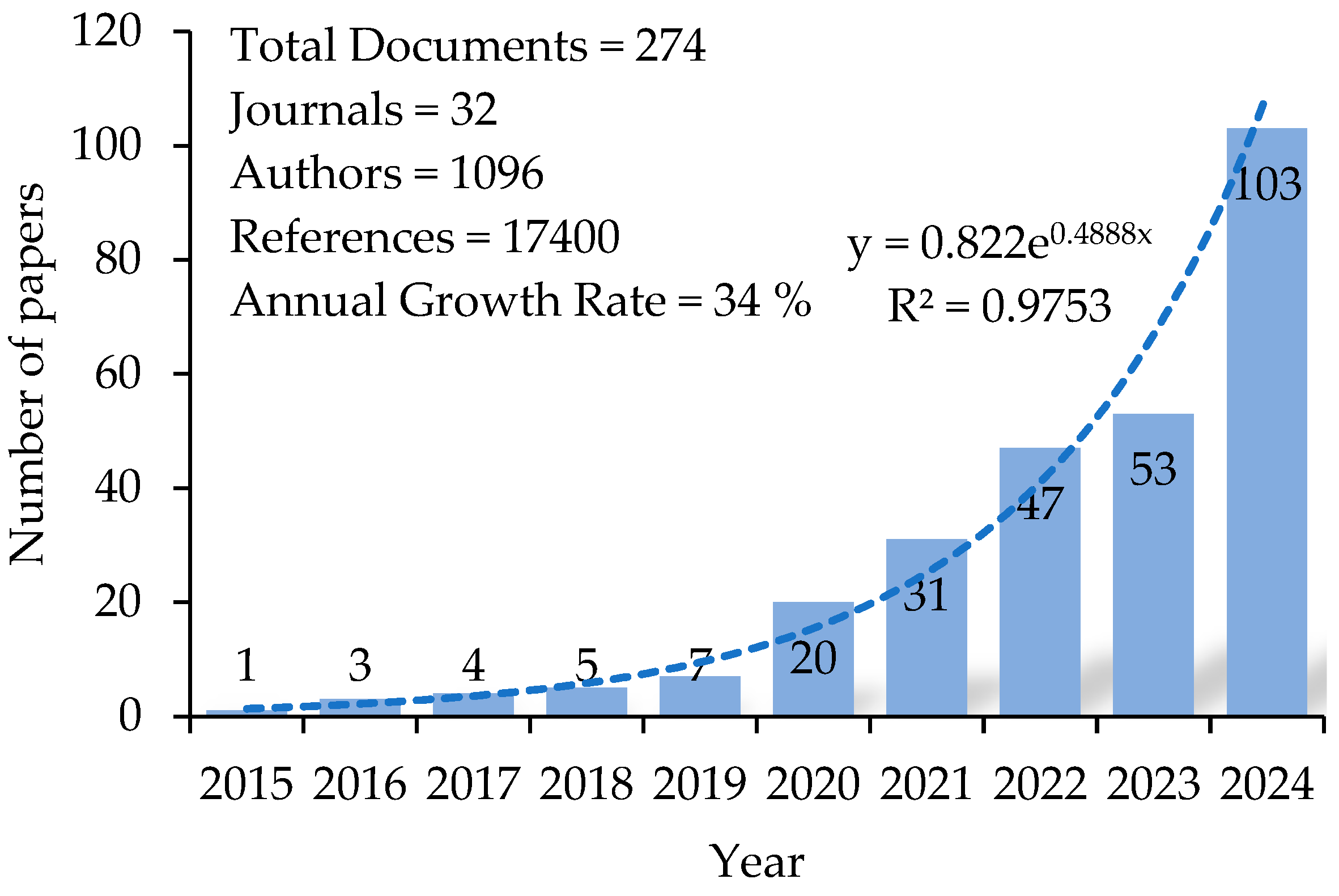

3.1. Bibliometric Performance Analysis

3.1.1. Journals

3.1.2. Most Cited Documents

3.2. Bibliometric Science Mapping

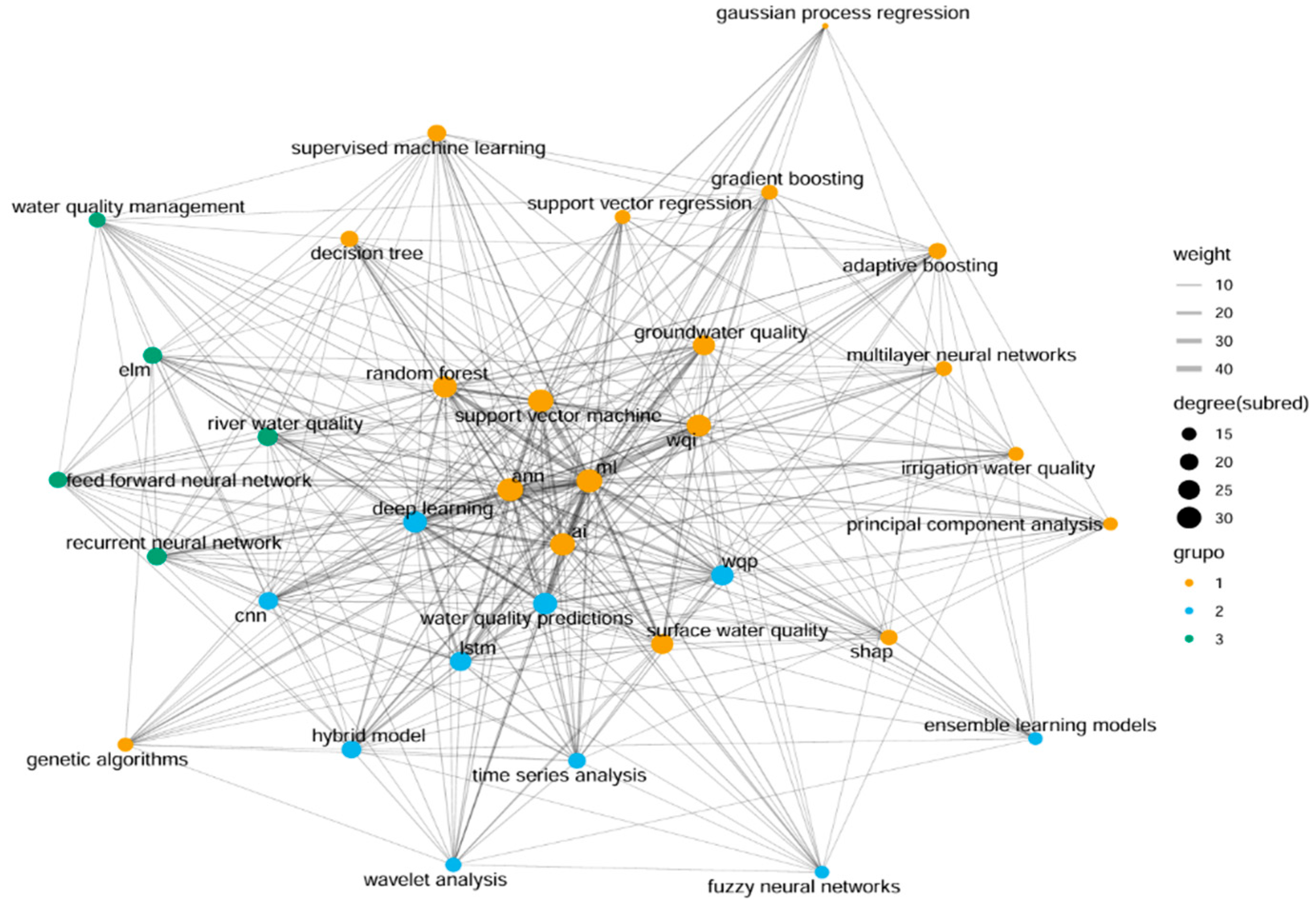

3.2.1. Network Analysis on Co-Occurrence of Authors’ Keywords

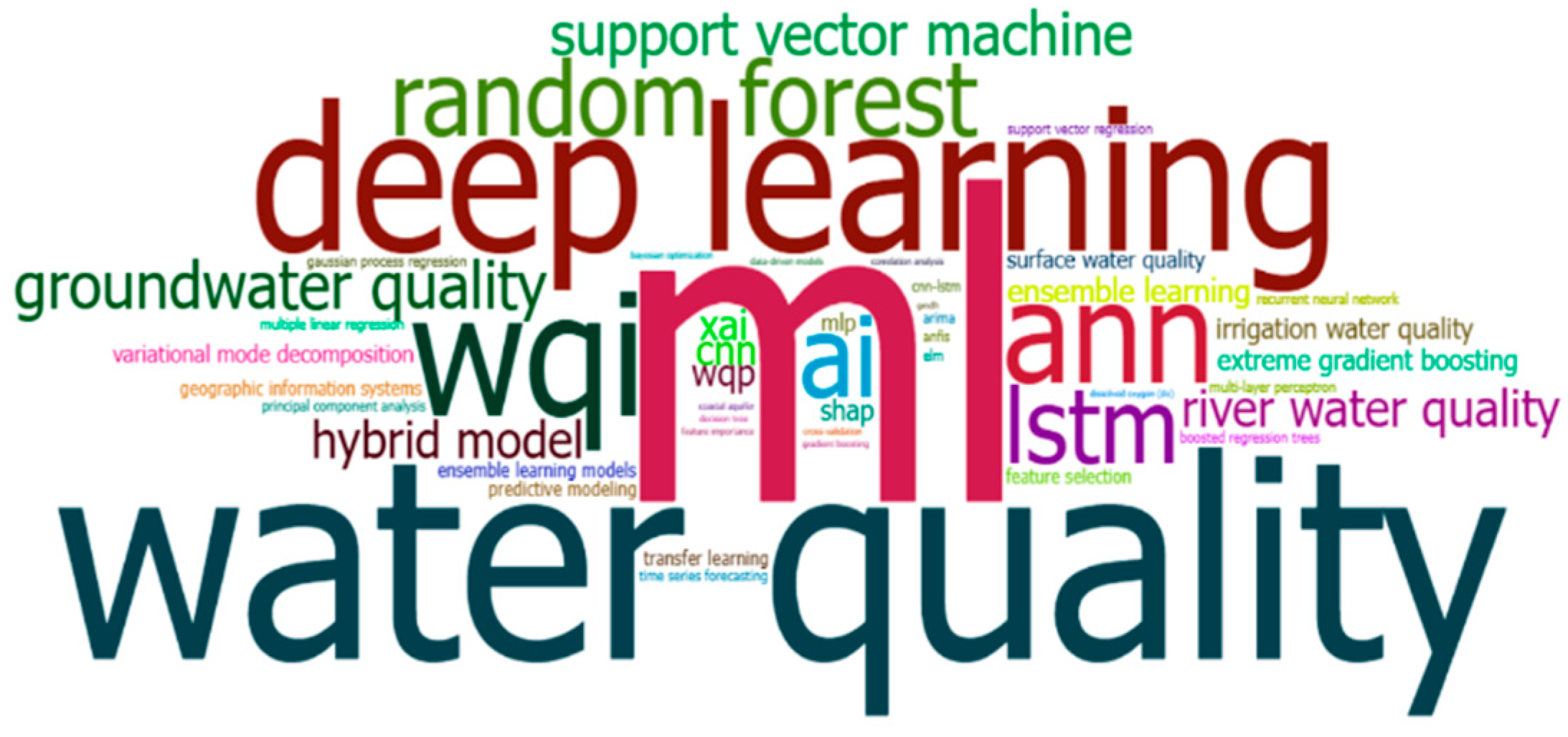

3.2.2. World Cloud

3.2.3. Thematic Map with Authors’ Keywords

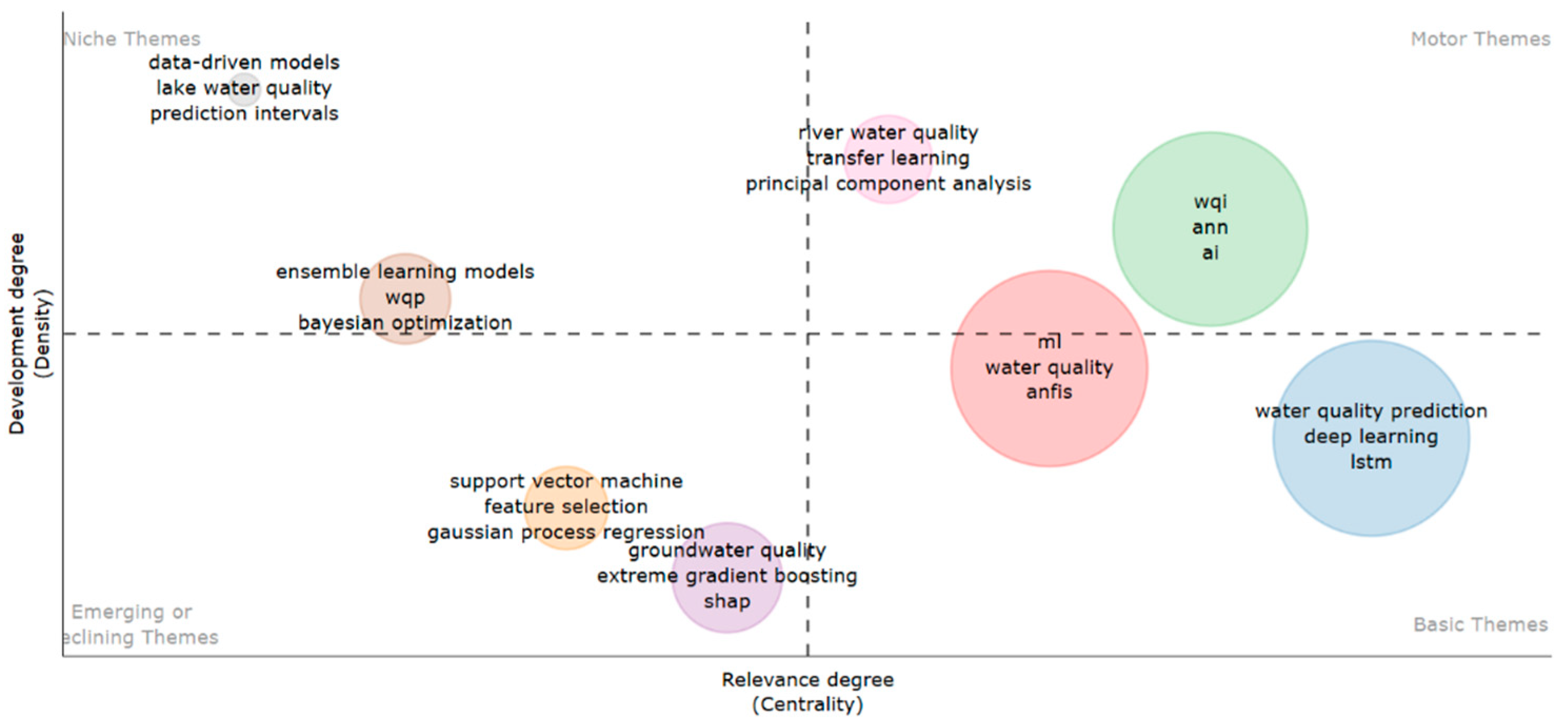

3.2.4. Thematic Evolution and Trend Topics with Keywords Plus

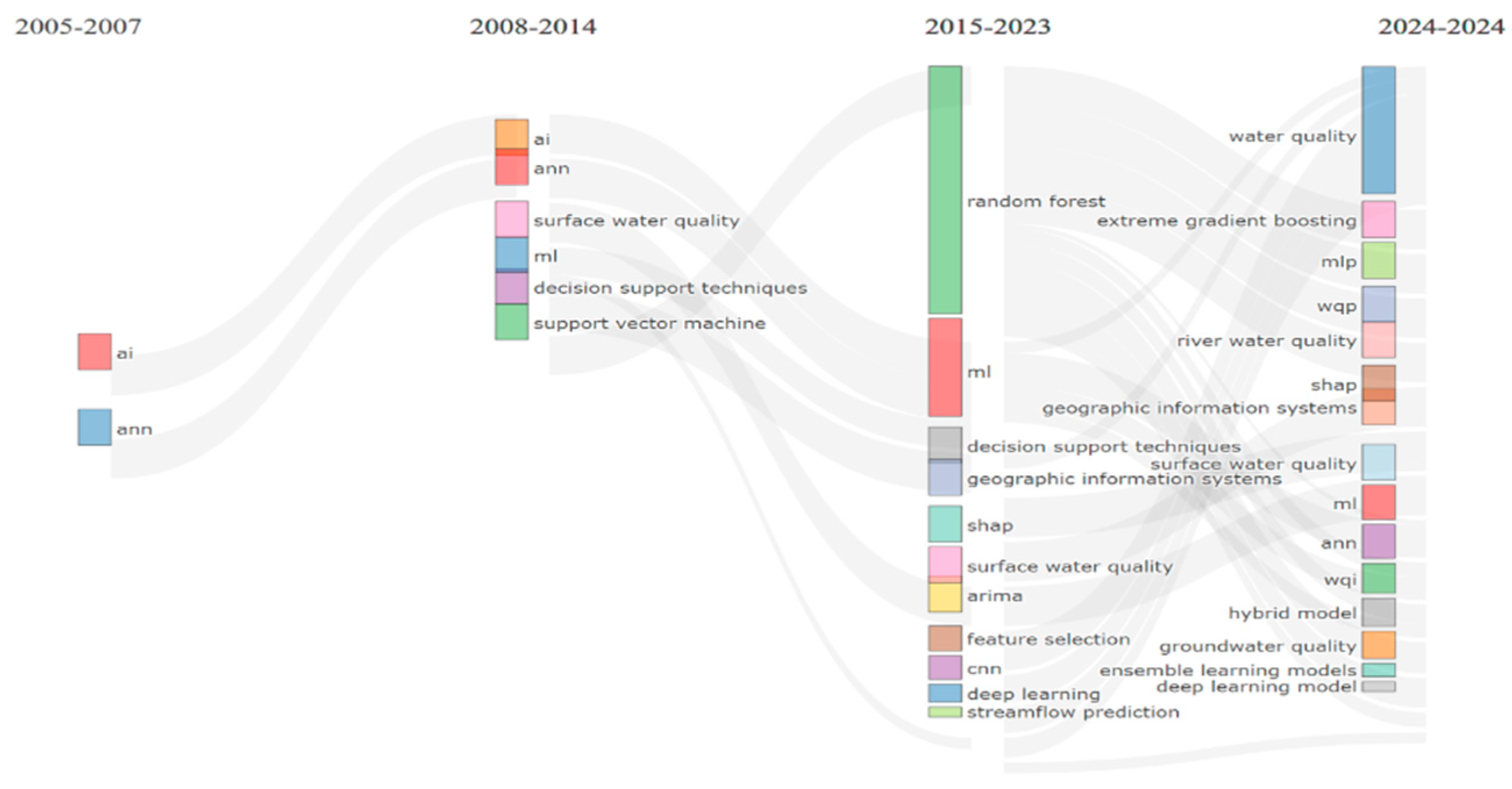

3.2.5. Social Structure

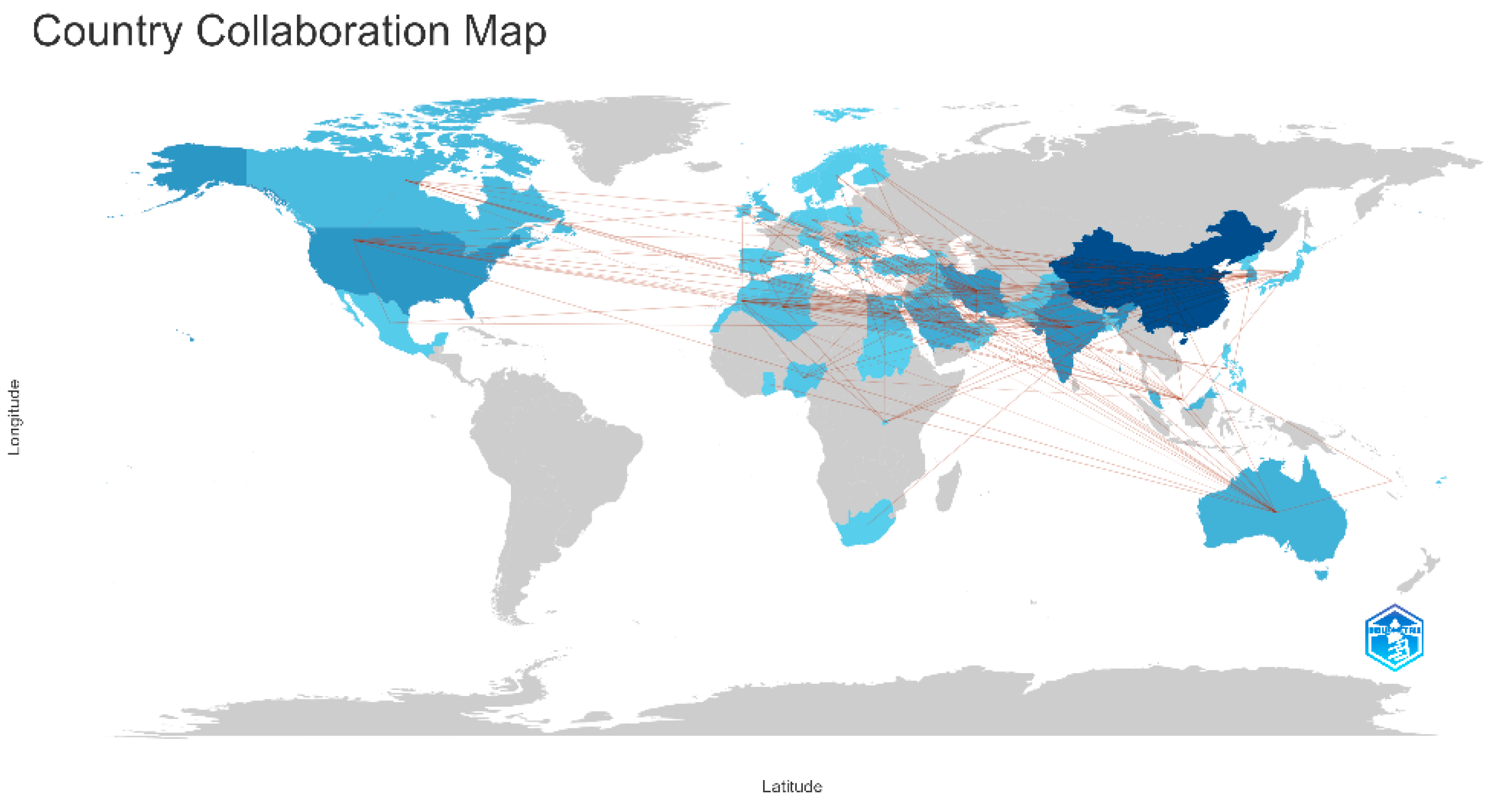

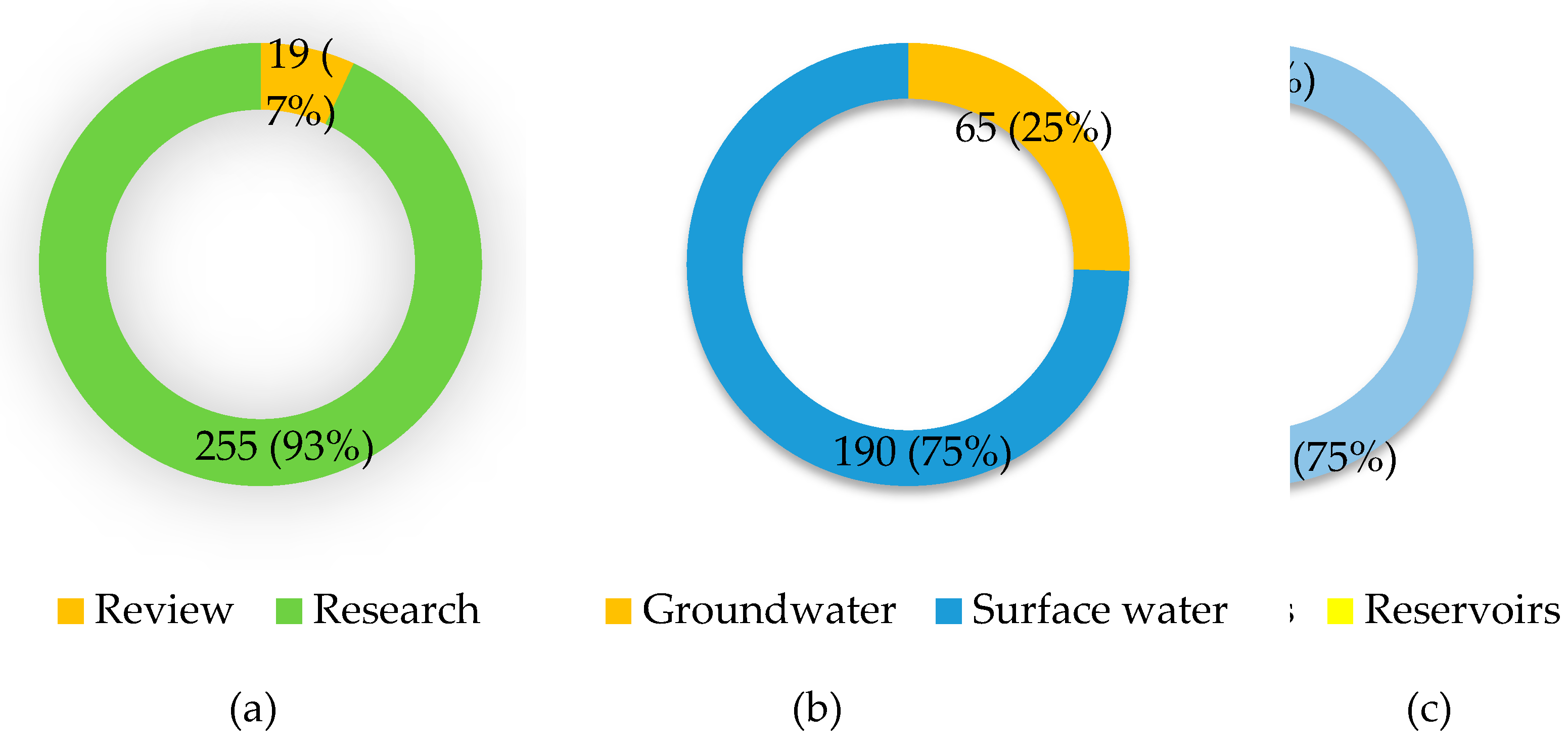

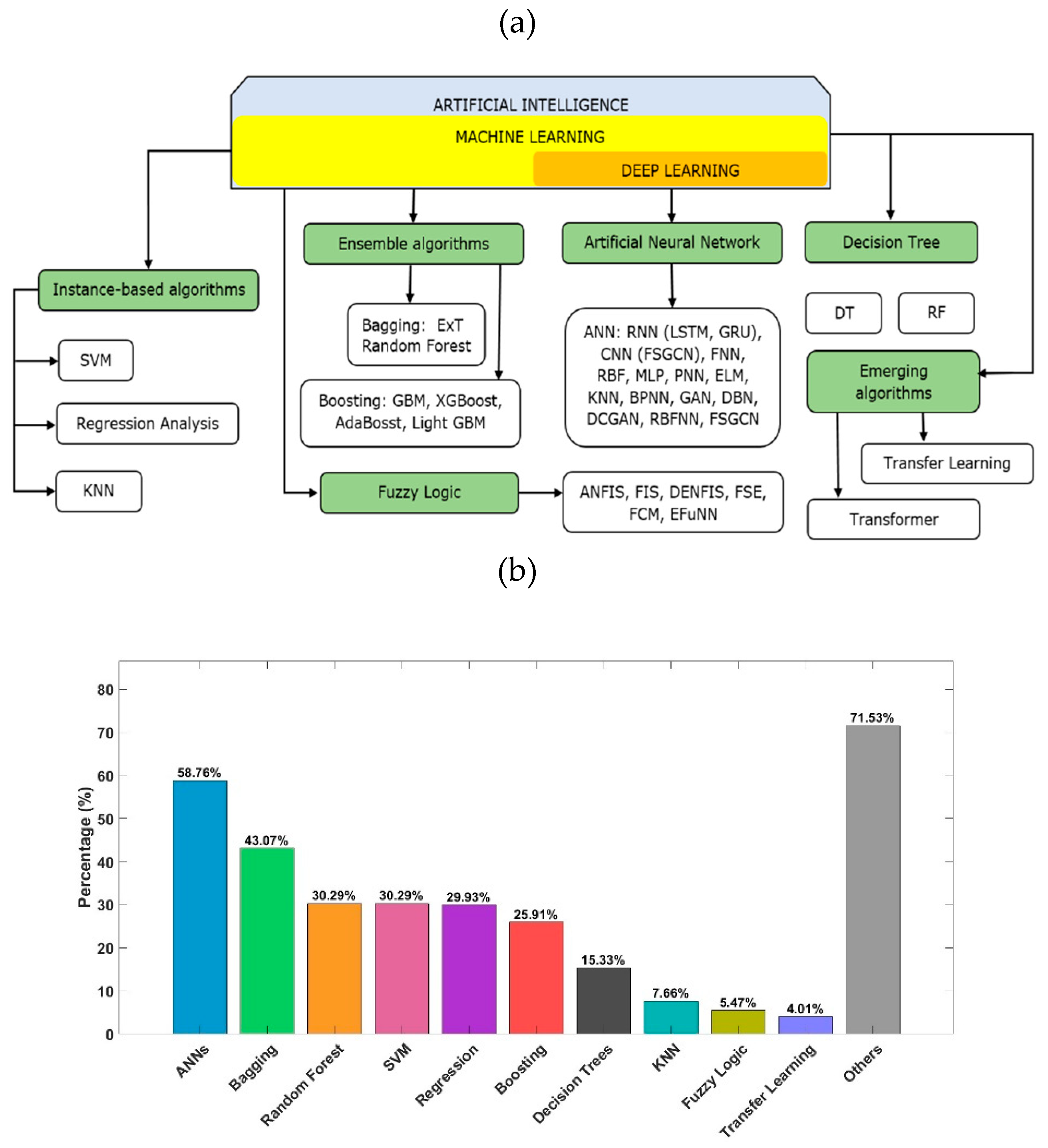

3.3. Systematic Literature Reviews Results

3.3.1. Prediction of River Water Quality Using AI/ML/DL

3.3.2. Prediction of River Water Quality Using AI/ML/DL

4. Answering the Research Questions

5. Contribution and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMT | Alternating Model Tree |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System |

| ANFIS–GP | Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System – Grid Partitioning |

| ANFIS–SC | ANFIS – Subtractive Clustering |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AO-SVM | Aquila Optimization Support Vector Machine |

| AR | Additive Regression |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| BDT | Boosted Decision Tree |

| BiGRU | Bi-directional Gated Recurrent Units |

| BMEF | Bayesian Maximum Entropy-based Fusion |

| BNN | Bayesian Neural Network |

| BPNN | Backpropagation Neural Network |

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting |

| CEEMD | Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CSA | Crow Search Algorithm |

| DBN | Deep Belief Network |

| DCGAN | Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network |

| DENFIS | Dynamic Evolving Neural-Fuzzy Inference System |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DR | Discretization Regression |

| DRNN | Deep Recurrent Neural Network |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| EANN | Emotional Artificial Neural Network |

| EANN-GA | Emotional Artificial Neural Network – Genetic Algorithm |

| EBM | Ensemble Bagged Machine |

| EFuNN | Evolving Fuzzy Neural Network |

| ELN | Extreme Learning Machine |

| EN | Elastic Network |

| ET | Extra Tree Regression |

| EWQI | Entropy-weighted Water Quality Index |

| ExT | Extra Trees |

| FFNNs | Feedforward Neural Networks |

| FNN | Feed-forward Neural Network |

| FSGCN | Functional-Structural Sub-Region Graph Convolutional Network |

| FFA | Firefly Algorithm |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GB | Gradient Boosting |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regression |

| GBT | Gradient Boosted Trees |

| GEP | Gene Expression Programming |

| GMDH | Group Method of Data Handling |

| GNB | Gaussian Naïve Bayes |

| GPR | Gaussian Process Regression |

| GRNN | Generalized Regression Neural Network |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| GS-RF | Grid Search Random Forest |

| GS-SVR | Grid Search Support Vector Regression |

| GWQI | Groundwater Quality Index |

| HGB | Histogram Gradient Boosting |

| IABC-BP | Improved Artificial Bee Colony – Backpropagation |

| IWQI | Irrigation Water Quality Index |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbours |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LSSVR | Least Squares Support Vector Regression |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| MARS | Multivariate Adaptive Regression Spline |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| MLRF | Multi-label Classification Through Random Forest |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MnLR | Multinomial Logistic Regression |

| NNE | Neural Network Ensemble |

| PLS | Partial Least Squares |

| PNN | Probabilistic Neural Network |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RBFNN | Radial Basis Function Neural Network |

| RC | Random Committee |

| REPT | Reduced Error Pruning Tree |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RFC | Randomizable Filtered Classification |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RR | Ridge Regression |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SLR | Simple Linear Regression |

| SMO-SVM | Sequential Minimal Optimization - Support Vector Machine |

| SSA-CNN-LSTM | Sparrow Search Algorithm - Convolutional Neural Network - Long Short-Term Memory |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| SVMR | Support Vector Machine Regression |

| SWEBM | Stochastic Weighted Ensemble Bagged Machine |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

| TL | Transfer Learning |

| WA | Wavelet Analysis |

| W-MGGP | Wavelet-Multigene Genetic Programming |

| WQI | Water Quality Index |

| WQP | Water Quality Parameters |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

| XAI | eXplainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XGB | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Ahmed, W.; Mohammed, S.; El-Shazly, A.; Morsy, S. Tigris River water surface quality monitoring using remote sensing data and GIS techniques. Egypt. J. Remote. Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaagai, A.; Aouissi, H.A.; Bencedira, S.; Hinge, G.; Athamena, A.; Heddam, S.; Gad, M.; Elsherbiny, O.; Elsayed, S.; Eid, M.H.; et al. Application of Water Quality Indices, Machine Learning Approaches, and GIS to Identify Groundwater Quality for Irrigation Purposes: A Case Study of Sahara Aquifer, Doucen Plain, Algeria. Water 2023, 15, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, H.; Sajjad, H.; Hussain, S.; Roshani; Masroor; Sharma, A. Surface water quality prediction in the lower Thoubal river watershed, India: A hyper-tuned machine learning approach and DNN-based sensitivity analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU, Informe mundial de las Naciones Unidas sobre el desarrollo de los recursos hídricos 2020: agua y cambio climático. Ciudad de México, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://es.unesco.org/themes/watersecurity/wwap/wwdr/2020.

- Gao, J.; Zhu, S.; Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Deng, G.; Wen, Y.; He, C.; Cao, Y. Bibliometric analysis of climate change and water quality. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 3441–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.; Pachepsky, Y.; Kim, S.; Abbas, A.; Kim, M.; Kwon, Y.S.; Ligaray, M.; Cho, K.H. Long short-term memory models of water quality in inland water environments. Water Res. X 2023, 21, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, E.E.; Baloch, M.Y.J.; Nigar, A.; Abualkhair, H.F.; Aldawood, F.K.; Tageldin, E. Machine Learning Algorithms for Predicting the Water Quality Index. Water 2023, 15, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.A.; Muhammad, N.S.; Abdullah, J. Scenario-based pollution discharge simulations and mapping using integrated QUAL2K-GIS. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummidivarapu, S.K.; Rehana, S.; Rao, Y.S. Mapping and assessment of river water quality under varying hydro-climatic and pollution scenarios by integrating QUAL2K, GEFC, and GIS. Environ. Res. 2023, 239, 117250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafaraz, J.; Kaleybar, F.A.; Karamjavan, J.M.; Habibzadeh, N. Predicting river water quality: An imposing engagement between machine learning and the QUAL2Kw models (case study: Aji-Chai, river, Iran). Results Eng. 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueh, Y.-Y.; Fan, C.; Huang, Y.-Z. Copper concentration simulation in a river by SWAT-WASP integration and its application to assessing the impacts of climate change and various remediation strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.; Sabokruhie, P.; Brinkmann, M.; Lindenschmidt, K.-E. Modelling Transport and Fate of Copper and Nickel across the South Saskatchewan River Using WASP—TOXI. Water 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.; Ahmed, Z.; Seefat, S.M.; Nahin, K.T.K. Assessment of surface water quality around a landfill using multivariate statistical method, Sylhet, Bangladesh. Environ. Nanotechnology, Monit. Manag. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.; Siddiqui, S.; Higgins, P.; Paul, A.S.; Lawrence, N.A.; Lall, A.S.; Khatoon, A.; Singh, A.; Majeed, P.A.; Massey, S.; et al. Assessment of seasonal impacts on Water Quality in Yamuna river using Water Quality Index and Multivariate Statistical approaches. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.P.; Fonseca, A.R.; Pacheco, F.; Fernandes, L.S. Water quality predictions through linear regression - A brute force algorithm approach. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoie, M.; Motamedi, A.; Fan, J.; Moudi, M. Prediction of water quality under the impacts of fine dust and sand storm events using an experimental model and multivariate regression analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.K.; Hunjra, A.I.; Bhaskar, R.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data in natural resources management: A comprehensive bibliometric review of literature spanning 1975–2022. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, J.; Wang, H.; Boczkaj, G.; Mahlknecht, J.; Singh, S.V.; Wang, C. Bibliometric analysis of artificial intelligence in wastewater treatment: Current status, research progress, and future prospects. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Inca, C.; Calle, M.; Croghan, D.; Haghighi, A.T.; Marttila, H.; Silander, J.; Alho, P. Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) in the Integrated Hydrological and Fluvial Systems Modeling: Review of Current Applications and Trends. Water 2022, 14, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ahn, J.; Kim, J.; Yoon, Y.; Park, J. Prediction and Interpretation of Water Quality Recovery after a Disturbance in a Water Treatment System Using Artificial Intelligence. Water 2022, 14, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga-Alvarado, M.; Gómez-Escalonilla, V.; Martínez-Santos, P. Identification of non-conventional groundwater resources by means of machine learning in the Aconcagua basin, Chile. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, D.N.; Quan, N.T.; Linh, D.Q.; Nhi, P.T.T.; Thuy, N.T.D. Using Machine Learning Models for Predicting the Water Quality Index in the La Buong River, Vietnam. Water 2022, 14, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallya, G.; Hantush, M.M.; Govindaraju, R.S. A Machine Learning Approach to Predict Watershed Health Indices for Sediments and Nutrients at Ungauged Basins. Water 2023, 15, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, F.; Kang, D. Application of Machine Learning in Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Water 2023, 15, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, Z. A Prediction Model Based on Deep Belief Network and Least Squares SVR Applied to Cross-Section Water Quality. Water 2020, 12, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Real-time probabilistic forecasting of river water quality under data missing situation: Deep learning plus post-processing techniques. J. Hydrol. 2020, 589, 125164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, K.P.; Mishra, A.K. Deep learning in hydrology and water resources disciplines: concepts, methods, applications, and research directions. J. Hydrol. 2023, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y. An ensemble model for accurate prediction of key water quality parameters in river based on deep learning methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellaiah, C.; Anbalagan, S.; Swaminathan, D.; Chowdhury, S.; Kadhila, T.; Shopati, A.K.; Shangdiar, S.; Sharma, B.; Amesho, K.T. Integrating deep learning techniques for effective river water quality monitoring and management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, D.V.V.; Venkataramana, L.Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Prasannamedha, G.; Harshana, S.; Srividya, S.J.; Harrinei, K.; Indraganti, S. Analysis and prediction of water quality using deep learning and auto deep learning techniques. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 821, 153311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khullar, S.; Singh, N. Water quality assessment of a river using deep learning Bi-LSTM methodology: forecasting and validation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 12875–12889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition.,” New York, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023.pdf.

- UN-Water, “The Sustainable Development Goal 6 Global Acceleration Framework,” Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://unsceb.org/sdg-6-global-acceleration-framework.

- Marques, M.d.C.; Mohamed, A.A.; Feitosa, P. Sustainable development goal 6 monitoring through statistical machine learning – Random Forest method. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2024, 8, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, L.; Usta, D.B.; Alvarez, L.B.; Duran-Llacer, I.; Lami, A.; Martínez-Retureta, R.; Urrutia, R. Machine Learning Algorithms for the Estimation of Water Quality Parameters in Lake Llanquihue in Southern Chile. Water 2023, 15, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.T.; Nigar, N.; Faisal, H.M.; Shahzad, M.K. AI for clean water: efficient water quality prediction leveraging machine learning. Water Pr. Technol. 2024, 19, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.G.; Nikoo, M.R.; Niknazar, F.; Al-Rawas, G.; Al-Wardy, M.; Gandomi, A.H. A multi-model data fusion methodology for reservoir water quality based on machine learning algorithms and bayesian maximum entropy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghiabi, A.H.; Nasrolahi, A.H.; Parsaie, A. Water quality prediction using machine learning methods. Water Qual. Res. J. 2018, 53, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, N.; Anmala, J.; Varma, M.R.; Rajitha, K. Performance of Machine Learning, Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and stacked ensemble models in predicting Water Quality Index (WQI) from surface water quality parameters, climatic and land use data. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzana, S.Z.; Paudyal, D.R.; Chadalavada, S.; Alam, J. Temporal Dynamics and Predictive Modelling of Streamflow and Water Quality Using Advanced Statistical and Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques. Water 2024, 16, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, G.; Nash, S.; Diganta, M.T.M.; Rahman, A.; Olbert, A.I. Robust machine learning algorithms for predicting coastal water quality index. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, I.I.S.; Othman, Z.; Sani, N.S. Water Quality Index Classification Based on Machine Learning: A Case from the Langat River Basin Model. Water 2022, 14, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Das, A.; Sharma, P. Predictive modeling of water quality index (WQI) classes in Indian rivers: Insights from the application of multiple Machine Learning (ML) models on a decennial dataset. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 3221–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Chen, S.; Ruan, X. Interpretable CEEMDAN-FE-LSTM-transformer hybrid model for predicting total phosphorus concentrations in surface water. J. Hydrol. 2024, 629, 130609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, V.; Bravo, I.; Saavedra, M. Water Quality Classification and Machine Learning Model for Predicting Water Quality Status—A Study on Loa River Located in an Extremely Arid Environment: Atacama Desert. Water 2023, 15, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Niazkar, M.; Zakwan, M.; Piraei, R. A Machine Learning-Based Framework for Water Quality Index Estimation in the Southern Bug River. Water 2023, 15, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aju, C.; Achu, A.; Mohammed, M.P.; Raicy, M.; Gopinath, G.; Reghunath, R. Groundwater quality prediction and risk assessment in Kerala, India: A machine-learning approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ren, H.; Wu, B.; Ye, L. A review of the application of machine learning in water quality evaluation. Eco-Environment Heal. 2022, 1, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, A.F.; Garibay, M.V.; Díaz-Vázquez, D.; Yebra-Montes, C.; Brown, L.E.; Johnson, A.; Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Improving river water quality prediction with hybrid machine learning and temporal analysis. Ecol. Informatics 2024, 82, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Zhou, A.; Shen, S.-L. Prediction of long-term water quality using machine learning enhanced by Bayesian optimisation. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 318, 120870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, J.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Wu, J. Water resource forecasting with machine learning and deep learning: A scientometric analysis. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, P.; Nagarajan, K.K.; Partheeban, P.; Krishnamurthy, V. Critical review on water quality analysis using IoT and machine learning models. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, F.; Huang, F. Research progress in water quality prediction based on deep learning technology: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 26415–26431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N.F.C.; Mohd, N.S.; Koting, S.; Ismail, Z.; Sherif, M.; El-Shafie, A. Groundwater quality forecasting modelling using artificial intelligence: A review. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 14, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, G. A scientometric review of the research on the impacts of climate change on water quality during 1998–2018. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 14322–14341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Mazumdar, A.; Basu, S. Evolution of groundwater quality assessment on urban area- a bibliometric analysis. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 20, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiyasha; Tung, T.M.; Yaseen, Z.M. A survey on river water quality modelling using artificial intelligence models: 2000–2020. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojbasic, S.; Dmitrasinovic, S.; Kostic, M.; Sekulic, M.T.; Radonic, J.; Dodig, A.; Stojkovic, M. Application of machine learning in river water quality management: a review. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering – A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G.; Balzano, M.; Caputo, A.; Pellegrini, M.M. Guidelines for Bibliometric-Systematic Literature Reviews: 10 steps to combine analysis, synthesis and theory development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2024, 27, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. How to combine and clean bibliometric data and use bibliometric tools synergistically: Guidelines using metaverse research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.A.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Botella, J.L.M. A Systematic Literature Review on the Revolutionary Impact of Blockchain in Modern Business. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahami, M.; Maalej, A.J.; Krichen, M. A systematic literature review on dynamic testing of blockchain oriented software. Sci. Comput. Program. 2024, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousso, B.Z.; Bertone, E.; Stewart, R.; Hamilton, D.P. A systematic literature review of forecasting and predictive models for cyanobacteria blooms in freshwater lakes. Water Res. 2020, 182, 115959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Côté, G.; Karimi, R. Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarimah, A.O.; Bazel, M.A.; Alaloul, W.S.; Alazaiza, M.Y.; Al-Zghoul, T.M.; Almuhaya, B.; Khan, A.; Mushtaha, A.W. Artificial intelligence in wastewater treatment: Research trends and future perspectives through bibliometric analysis. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Searchsmart.org: Guiding researchers to the best databases and search systems for systematic reviews and beyond. Res. Synth. Methods 2024, 15, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dinter, R.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Catal, C. Automation of systematic literature reviews: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRAN, “TextmineR: Functions for Text Mining and Topic Modeling.” https://cran.rproject.org/package=textmineR.

- Kassem, A.; Sefelnasr, A.; Ebraheem, A.A.; Sherif, M. Seawater intrusion physical models: A bibliometric analysis and review of mitigation strategies. J. Hydrol. 2024, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, Z.; Moja, N.T.; Nkambule, T.T.; de Kock, L.-A. Utilization of biochar for remediation of heavy metals in aqueous environments: A review and bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kong, F.; Yin, H.; Middel, A.; Zheng, X.; Huang, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, D.; Wen, Z. Impacts of green roofs on water, temperature, and air quality: A bibliometric review. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazatti, M.J.; Justi, A.C.A.; Souza, R.F.; Miranda, J.C.d.C. Soybean biorefinery and technological forecasts based on a bibliometric analysis and network mapping. Environ. Dev. 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batagelj, V.; Cerinšek, M. On bibliographic networks. Scientometrics 2013, 96, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A.A. Enhancing systematic literature review adapting ‘double diamond approach’. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Gauster, S.P. How to search for literature in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A comprehensive step-by-step guide. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.; Vakkalanka, S.; Kuzniarz, L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 64, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, M.; Demiray, B.Z.; Xiang, Z.; Ewing, G.J.; Sermet, Y.; Demir, I. A comprehensive review of deep learning applications in hydrology and water resources. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 82, 2635–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ma, C.; Ma, J.; Huangfu, X.; He, Q. Machine learning in natural and engineered water systems. Water Res. 2021, 205, 117666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, G.W.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, V.P. Surface water quality under climate change scenarios in the Bosque watershed, Central Texas of United States. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2024, 25, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.; Srinath, S.; Tuppad, P. Comprehensive analysis of multiple classifiers for enhanced river water quality monitoring with explainable AI. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, L.M.; Mohiyaden, H.A.; Marufuzzaman, M.; Noh, N.S.M.; Heddam, S.; Ehteram, M.; Kisi, O.; Sammen, S.S. Developing an ensembled machine learning model for predicting water quality index in Johor River Basin. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, R.; Aalami, M.T.; Adamowski, J. Short-term water quality variable prediction using a hybrid CNN–LSTM deep learning model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2020, 34, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, R.; Adamowski, J.; Moghaddam, A.A. Application of wavelet-artificial intelligence hybrid models for water quality prediction: a case study in Aji-Chay River, Iran. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 1797–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Y.; Afan, H.A.; El-Shafie, A.H.; Koting, S.B.; Mohd, N.S.; Jaafar, W.Z.B.; Sai, H.L.; Malek, M.A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Mohtar, W.H.M.W.; et al. Towards a time and cost effective approach to water quality index class prediction. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Shang, X.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Zhang, M. Prediction of dissolved oxygen concentration in hypoxic river systems using support vector machine: a case study of Wen-Rui Tang River, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 16062–16076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijani, E.; Barzegar, R.; Deo, R.; Tziritis, E.; Skordas, K. Design and implementation of a hybrid model based on two-layer decomposition method coupled with extreme learning machines to support real-time environmental monitoring of water quality parameters. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 648, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, S.I.; Pham, Q.B.; Saini, G.; Linh, N.T.T.; Ahmed, A.N.; Mohajane, M.; Khaledian, M.; Abdulkadir, R.A.; Bach, Q.-V. Implementation of data intelligence models coupled with ensemble machine learning for prediction of water quality index. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 41524–41539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori, R.; Yeh, H.-D.; Abbasi, M.; Kachoosangi, F.T.; Moazami, S. Uncertainty analysis of support vector machine for online prediction of five-day biochemical oxygen demand. J. Hydrol. 2015, 527, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaa, B.; Elbeltagi, A.; Boudibi, S.; Chaffaï, H.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Kulimushi, L.C.; Choudhari, P.; Hani, A.; Brouziyne, Y.; Wong, Y.J. Water quality index modeling using random forest and improved SMO algorithm for support vector machine in Saf-Saf river basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 48491–48508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, H.; Jiang, P.; Yu, S.; Lin, G.; Bychkov, I.; Hmelnov, A.; Ruzhnikov, G.; Zhu, N.; Liu, Z. A transfer Learning-Based LSTM strategy for imputing Large-Scale consecutive missing data and its application in a water quality prediction system. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidzadeh, Z.; Ehteram, M.; Shabanian, H. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BILSTM) - Support Vector Machine: A new machine learning model for predicting water quality parameters. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 15, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-C. Application of wavelet theory to enhance the performance of machine learning techniques in estimating water quality parameters (case study: Gao-Ping River). Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 87, 1294–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, L.; Ben, X.; Jin, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F. Hybrid deep learning based prediction for water quality of plain watershed. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzar, M.S.; Benaafi, M.; Costache, R.; Alagha, O.; Mu'AZu, N.D.; Zubair, M.; Abdullahi, J.; Abba, S. New generation neurocomputing learning coupled with a hybrid neuro-fuzzy model for quantifying water quality index variable: A case study from Saudi Arabia. Ecol. Informatics 2022, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, W.; Jiang, T.; Ju, H. Enhanced prediction of river dissolved oxygen through feature- and model-based transfer learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodkar, K.; Mirchi, A.; Nourani, V.; Kaghazchi, A.; Sadler, J.M.; Mansaray, A.; Wagner, K.; Alderman, P.D.; Taghvaeian, S.; Bailey, R.T. Stream salinity prediction in data-scarce regions: Application of transfer learning and uncertainty quantification. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2024, 266, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, P.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z. A coupled model to improve river water quality prediction towards addressing non-stationarity and data limitation. Water Res. 2023, 248, 120895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Wu, H.; Gao, M.; Yi, H.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, L.; Cheng, S. TLT: Recurrent fine-tuning transfer learning for water quality long-term prediction. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.; Brcic, M.; Cabitza, F.; Choi, J.; Confalonieri, R.; Del Ser, J.; Guidotti, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Herrera, F.; Holzinger, A.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) 2.0: A manifesto of open challenges and interdisciplinary research directions. Inf. Fusion 2024, 106, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; Cortés, C.B.; Yáñez, M.A. Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Hydrology: Interpreting Black-Box Snowmelt-Driven Streamflow Predictions in an Arid Andean Basin of North-Central Chile. Water 2023, 15, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madni, H.A.; Umer, M.; Ishaq, A.; Abuzinadah, N.; Saidani, O.; Alsubai, S.; Hamdi, M.; Ashraf, I. Water-Quality Prediction Based on H2O AutoML and Explainable AI Techniques. Water 2023, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, F.; Rahman, A. Coupling Machine and Deep Learning with Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Improving Prediction of Groundwater Quality and Decision-Making in Arid Region, Saudi Arabia. Water 2023, 15, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, R.; Sun, J.; Yu, H.; Li, Y. Application of machine learning in groundwater quality modeling - A comprehensive review. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Scholz, M.; Ali, M.; Gad, M.; Elsayed, S.; Khadr, M.; Hussein, H.; Ibrahim, H.H.; Eid, M.H.; et al. Evaluation and Prediction of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation Using an Integrated Water Quality Indices, Machine Learning Models and GIS Approaches: A Representative Case Study. Water 2023, 15, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahat, S.H.; Steissberg, T.; Chang, W.; Chen, X.; Mandavya, G.; Tracy, J.; Wasti, A.; Atreya, G.; Saki, S.; Bhuiyan, A.E.; et al. Remote sensing-enabled machine learning for river water quality modeling under multidimensional uncertainty. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 898, 165504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huangfu, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, H.; Sun, Q. Remote Estimation of Water Quality Parameters of Medium- and Small-Sized Inland Rivers Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Water 2020, 12, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'GRady, J.; Zhang, D.; O'COnnor, N.; Regan, F. A comprehensive review of catchment water quality monitoring using a tiered framework of integrated sensing technologies. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 765, 142766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Peng, M.; Wang, M. A River Water Quality Prediction Method Based on Dual Signal Decomposition and Deep Learning. Water 2024, 16, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.N.; Othman, F.B.; Afan, H.A.; Ibrahim, R.K.; Fai, C.M.; Hossain, S.; Ehteram, M.; Elshafie, A. Machine learning methods for better water quality prediction. J. Hydrol. 2019, 578, 124084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liao, Z.; Wang, L. The Use of Attention-Enhanced CNN-LSTM Models for Multi-Indicator and Time-Series Predictions of Surface Water Quality. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 6103–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, J.M.; Koenig, L.E.; Gorski, G.; Carter, A.M.; Hall, R.O. Evaluating a process-guided deep learning approach for predicting dissolved oxygen in streams. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, 15270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.; Ganesh, S.S.; Karthick, A.; Sampradeepraj, T. Environmental water quality prediction based on COOT-CSO-LSTM deep learning. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 54525–54533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursaeid, M.; Poursaeed, A.H.; Shabanlou, S. Water quality fluctuations prediction and Debi estimation based on stochastic optimized weighted ensemble learning machine. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 188, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J, V.; K, K.; Shanmugaiah, K.; Bai, F.J.J.S.; S, K. AO-SVM: a machine learning model for predicting water quality in the cauvery river. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 075025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluru, R.K.; Sundararajan, S.; S, V.; Balakrishnan, S.; V, S.; Rajagopal, M. Predicting nitrous oxide contaminants in Cauvery basin using region-based convolutional neural network. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 26, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lim, J.Y.; Oh, J.-M. Innovative interpretable AI-guided water quality evaluation with risk adversarial analysis in river streams considering spatial-temporal effects. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 350, 124015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lin, S.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Deng, H.; Fang, H.; Li, W. Analysis of dissolved oxygen influencing factors and concentration prediction using input variable selection technique: A hybrid machine learning approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, G.; Shen, C.; Duncan, J.; Cibin, R. Performance evaluation of deep learning based stream nitrate concentration prediction model to fill stream nitrate data gaps at low-frequency nitrate monitoring basins. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.B.; Patra, K.C.; Pradhan, B.; Samantra, A. HDTO-DeepAR: A novel hybrid approach to forecast surface water quality indicators. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wollheim, W.M. Prediction of riverine daily minimum dissolved oxygen concentrations using hybrid deep learning and routine hydrometeorological data. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 918, 170383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wu, T. A deep learning interpretable model for river dissolved oxygen multi-step and interval prediction based on multi-source data fusion. J. Hydrol. 2024, 629, 130637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mukhtar, M.; Srivastava, A.; Khadke, L.; Al-Musawi, T.; Elbeltagi, A. Prediction of Irrigation Water Quality Indices Using Random Committee, Discretization Regression, REPTree, and Additive Regression. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 38, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, B.; Zhang, S.; Driscoll, C.T.; Wen, T. Human and natural impacts on the U.S. freshwater salinization and alkalinization: A machine learning approach. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 889, 164138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition and a Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network for Surface Water Quality Prediction of the Xiaofu River, China. Water 2023, 15, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wu, W.; Cai, Y.; Wan, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, Q.; Shen, S. Feature Extraction and Prediction of Water Quality Based on Candlestick Theory and Deep Learning Methods. Water 2023, 15, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.; Song, G.; Lee, J.; Cho, M. Deep Learning Methods for Predicting Tap-Water Quality Time Series in South Korea. Water 2022, 14, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, J.M.Z.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Alelyani, S.; Mohana, M.; Hosain, M. Improving Water Quality Index Prediction Using Regression Learning Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 13702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorado-Guerra, D.Y.; Corzo-Pérez, G.; Paredes-Arquiola, J.; Pérez-Martín, M.Á. Machine learning models to predict nitrate concentration in a river basin. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 125012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, I.C.; Ahmadisharaf, E.; Sun, Y. Predicting in-stream water quality constituents at the watershed scale using machine learning. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2022, 251, 104078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Golkarian, A.; Melesse, A.M.; Deo, R.C. Suspended sediment load modeling using advanced hybrid rotation forest based elastic network approach. J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Yao, L. A hybrid model for water quality parameter prediction based on CEEMDAN-IALO-LSTM ensemble learning. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, A.; Lv, R.; Zhao, S.; Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z. A study on water quality parameters estimation for urban rivers based on ground hyperspectral remote sensing technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 63640–63654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balson, T.; Ward, A.S. A machine learning approach to water quality forecasts and sensor network expansion: Case study in the Wabash River Basin, United States. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, N.H.A.; Yaacob, W.F.W.; Nasir, S.A.M.; Shaadan, N. Prediction of Water Quality Classification of the Kelantan River Basin, Malaysia, Using Machine Learning Techniques. Water 2022, 14, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, N.N.M.; Hayder, G.; Yusof, K.A. Water Quality Predictive Analytics Using an Artificial Neural Network with a Graphical User Interface. Water 2022, 14, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weierbach, H.; Lima, A.R.; Willard, J.D.; Hendrix, V.C.; Christianson, D.S.; Lubich, M.; Varadharajan, C. Stream Temperature Predictions for River Basin Management in the Pacific Northwest and Mid-Atlantic Regions Using Machine Learning. Water 2022, 14, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, A.F.; Yebra-Montes, C.; Garibay, M.V.; de Anda, J.; Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. Simple Prediction of an Ecosystem-Specific Water Quality Index and the Water Quality Classification of a Highly Polluted River through Supervised Machine Learning. Water 2022, 14, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.; Srdjević, Z.; Srdjević, B. Water quality prediction based on Naïve Bayes algorithm. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Keshari, A.K. Dissolved oxygen modelling of the Yamuna River using different ANFIS models. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 3359–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S.V.; Sharafati, A.; Feizi, H.; Marjaie, S.M.S.; Asadollah, S.B.H.S.; Motta, D. An efficient strategy for predicting river dissolved oxygen concentration: application of deep recurrent neural network model. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Predicting river dissolved oxygen time series based on stand-alone models and hybrid wavelet-based models. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najah, A.; Teo, F.Y.; Chow, M.F.; Huang, Y.F.; Latif, S.D.; Abdullah, S.; Ismail, M.; El-Shafie, A. Surface water quality status and prediction during movement control operation order under COVID-19 pandemic: Case studies in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Maleki, N.; Rezaie-Balf, M.; Singh, V.P.; Alizamir, M.; Kim, N.W.; Lee, J.-T.; Kisi, O. Assessment of the total organic carbon employing the different nature-inspired approaches in the Nakdong River, South Korea. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H. Water Quality Prediction in the Luan River Based on 1-DRCNN and BiGRU Hybrid Neural Network Model. Water 2021, 13, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setshedi, K. J. , Mutingwende, N., Ngqwala, N. P. The Use of Artificial Neural Networks to Predict the Physicochemical Characteristics of Water Quality in Three District Municipalities, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, S.I.; Abdulkadir, R.A.; Sammen, S.S.; Usman, A.G.; Meshram, S.G.; Malik, A.; Shahid, S. Comparative implementation between neuro-emotional genetic algorithm and novel ensemble computing techniques for modelling dissolved oxygen concentration. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2021, 66, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.-L. Comparison of Forecasting Models for Real-Time Monitoring of Water Quality Parameters Based on Hybrid Deep Learning Neural Networks. Water 2021, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Fitch, P.; Thorburn, P.J. Predicting the Trend of Dissolved Oxygen Based on the kPCA-RNN Model. Water 2020, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-S.; Pyo, J.; Chun, J.A. Prediction of Water Level and Water Quality Using a CNN-LSTM Combined Deep Learning Approach. Water 2020, 12, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, M.; Ahmadianfar, I.; Chu, X.F.; Yaseen, Z.M. Prediction of surface water total dissolved solids using hybridized wavelet-multigene genetic programming: New approach. J. Hydrol. 2020, 589, 125335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Khosravi, K.; Tiefenbacher, J.; Nguyen, H.; Kazakis, N. Improving prediction of water quality indices using novel hybrid machine-learning algorithms. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 721, 137612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fang, G.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. Water Quality Prediction Model of a Water Diversion Project Based on the Improved Artificial Bee Colony–Backpropagation Neural Network. Water 2018, 10, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheli, B.; Aalami, M.T.; El-Shafie, A.; Ghorbani, M.A.; Deo, R.C. Uncertainty assessment of the multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network model with implementation of the novel hybrid MLP-FFA method for prediction of biochemical oxygen demand and dissolved oxygen: a case study of Langat River. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, C.; Camejo, J.; Banciu, A.; Nita-Lazar, M.; Paun, I.; Cristofor, S.; Pacheco, O.R.; Guevara, M. Water quality of Danube Delta systems: ecological status and prediction using machine-learning algorithms. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 2413–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; You, X.-Y. Recent Advances in Surface Water Quality Prediction Using Artificial Intelligence Models. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 38, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Escalonilla, V.; Montero-González, E.; Díaz-Alcaide, S.; Martín-Loeches, M.; del Rosario, M.R.; Martínez-Santos, P. A machine learning approach to site groundwater contamination monitoring wells. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, C.; Yang, W.; Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Dai, R. Improving prediction of groundwater quality in situations of limited monitoring data based on virtual sample generation and Gaussian process regression. Water Res. 2024, 267, 122498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.; Abbas, A.; Kim, H.G.; Van Hoan, H.; Van Tuan, P.; Long, P.T.; Lee, E.; Cho, K.H. Spatial prediction of groundwater salinity in multiple aquifers of the Mekong Delta region using explainable machine learning models. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Liang, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; He, B.; Wang, G. Identifying the spatial pattern and driving factors of nitrate in groundwater using a novel framework of interpretable stacking ensemble learning. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2024, 46, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boufekane, A.; Meddi, M.; Maizi, D.; Busico, G. Performance of artificial intelligence model (LSTM model) for estimating and predicting water quality index for irrigation purposes in order to improve agricultural production. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Sharan, A.; Sharma, K.; Ram, A.; Roy, D.K.; Datta, B. Scrutinizing different predictive modeling validation methodologies and data-partitioning strategies: new insights using groundwater modeling case study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I. Ayaz Sensitivity analysis-driven machine learning approach for groundwater quality prediction: Insights from integrating ENTROPY and CRITIC methods. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 26, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Y.; Nan, T.; Guo, H. Prediction of arsenic and fluoride in groundwater of the North China Plain using enhanced stacking ensemble learning. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.R.; Das, S. Coastal groundwater quality prediction using objective-weighted WQI and machine learning approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 19439–19457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, T.; Gogoi, U.R.; Samanta, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Singh, M.K.; Pasupuleti, S. Identifying the Most Discriminative Parameter for Water Quality Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Water 2024, 16, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesoriero, A.J.; Wherry, S.A.; Dupuy, D.I.; Johnson, T.D. Predicting Redox Conditions in Groundwater at a National Scale Using Random Forest Classification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 5079–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzain, H.E.; Abdalla, O.; Ahmed, H.A.; Kacimov, A.; Al-Maktoumi, A.; Al-Higgi, K.; Abdallah, M.; Yassin, M.A.; Senapathi, V. An innovative approach for predicting groundwater TDS using optimized ensemble machine learning algorithms at two levels of modeling strategy. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Su, C.; Ahmad, M.; Baloch, M.Y.J.; Rashid, A.; Ullah, Z.; Abbas, H.; Nigar, A.; Ali, A.; Ullah, A. Hydrogeochemistry and prediction of arsenic contamination in groundwater of Vehari, Pakistan: comparison of artificial neural network, random forest and logistic regression models. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2023, 46, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, L.; Lakshmanan, V.R. Groundwater quality assessment using machine learning models: a comprehensive study on the industrial corridor of a semi-arid region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboobi, H.; Shakiba, A.; Mirbagheri, B. Improving groundwater nitrate concentration prediction using local ensemble of machine learning models. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajib, A.M.; Diganta, M.T.M.; Rahman, A.; Dabrowski, T.; Olbert, A.I.; Uddin, G. Developing a novel tool for assessing the groundwater incorporating water quality index and machine learning approach. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, R.; Mousavi, S.R.; Rahimabadi, P.D.; Panahi, M.; Rahmani, A. Assessing data mining algorithms to predict the quality of groundwater resources for determining irrigation hazard. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Pang, Z.; Miao, S. Predicting Groundwater Indicator Concentration Based on Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network: A Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 15612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.-M.; Ni, C.-F.; Su, Y.-S.; Nguyen, V.-C.; Lee, I.-H.; Lin, C.-P.; Nguyen, H.-H. Predicting Heavy Metal Concentrations in Shallow Aquifer Systems Based on Low-Cost Physiochemical Parameters Using Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 12180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşan, M.; Taşan, S.; Demir, Y. Estimation and uncertainty analysis of groundwater quality parameters in a coastal aquifer under seawater intrusion: a comparative study of deep learning and classic machine learning methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 2866–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Bali, V.; Nawaz, N.; Bali, S.; Mathur, S.; Mishra, R.K.; Rani, S. A Machine-Learning Approach for Prediction of Water Contamination Using Latitude, Longitude, and Elevation. Water 2022, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadri, S.; Pande, C.B.; Panneerselvam, B.; Moharir, K.N.; Elbeltagi, A. Prediction of irrigation groundwater quality parameters using ANN, LSTM, and MLR models. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 21067–21091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, K.P.; Wheeler, D.C.; Flory, A.R.; Jones, R.R.; Patel, D.; Nolan, B.T.; Ward, M.H. Modeling groundwater nitrate exposure in private wells of North Carolina for the Agricultural Health Study. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 655, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakizadeh, M. Spatial analysis of total dissolved solids in Dezful Aquifer: Comparison between universal and fixed rank kriging. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2019, 221, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Cai, Z.; Shoaib, M.; Iqbal, J.; Ismail, M.; Arifullah; Alrefaei, A.F.; Albeshr, M.F. Machine Learning Models for Water Quality Prediction: A Comprehensive Analysis and Uncertainty Assessment in Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan. Water 2024, 16, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Batelaan, O.; Fadaee, M.; Hinkelmann, R. Ensemble machine learning paradigms in hydrology: A review. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrees, A.; Awan, H.H.; Javed, M.F.; Mohamed, A.M. Prediction of water quality indexes with ensemble learners: Bagging and boosting. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yao, K.; Zhu, B.; Gao, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lin, F.; Zhang, X. Water Quality Inversion of a Typical Rural Small River in Southeastern China Based on UAV Multispectral Imagery: A Comparison of Multiple Machine Learning Algorithms. Water 2024, 16, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najah, A.; El-Shafie, A.; Karim, O.A.; El-Shafie, A.H. Application of artificial neural networks for water quality prediction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2013, 22, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Pal, A. Tuning fuzzy logic controller with SGWO for river water quality modelling. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 54, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilipkumar, J.; Shanmugam, P. Fuzzy-based global water quality assessment and water quality cells identification using satellite data. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 193, 115148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyakulina, A.; Yusipov, I.; Moskalev, A.; Franceschi, C.; Ivanchenko, M. eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in aging clock models. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 93, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nallakaruppan, M.K.; Gangadevi, E.; Shri, M.L.; Balusamy, B.; Bhattacharya, S.; Selvarajan, S. Reliable water quality prediction and parametric analysis using explainable AI models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Datta, P.; Pal, P.; Ghosh, K.; Das, A.; Das, B.K. Unveiling the hidden connections: Using explainable artificial intelligence to assess water quality criteria in nine giant rivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, X.; Lai, C.; Chen, L.; Wei, J. A novel coupling interpretable machine learning framework for water quality prediction and environmental effect understanding in different flow discharge regulations of hydro-projects. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 950, 175281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juna, A.; Umer, M.; Sadiq, S.; Karamti, H.; Eshmawi, A.A.; Mohamed, A.; Ashraf, I. Water Quality Prediction Using KNN Imputer and Multilayer Perceptron. Water 2022, 14, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Mumtaz, R.; Anwar, H.; Shah, A.A.; Irfan, R.; García-Nieto, J. Efficient Water Quality Prediction Using Supervised Machine Learning. Water 2019, 11, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pany, R.; Rath, A.; Swain, P.C. Water quality assessment for River Mahanadi of Odisha, India using statistical techniques and Artificial Neural Networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Luo, D.; Tan, J.; Li, S.; Song, X.; Xiong, R.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Xiong, H. Spatial Mapping and Prediction of Groundwater Quality Using Ensemble Learning Models and SHapley Additive exPlanations with Spatial Uncertainty Analysis. Water 2024, 16, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, S.; Nikoo, M.R.; Mohammadi, A.; Barzegar, R. Two-stage meta-ensembling machine learning model for enhanced water quality forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2024, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, L.; Usta, D.B.; Duran-Llacer, I.; Alvarez, L.B.; Yépez, S.; Bourrel, L.; Frappart, F.; Urrutia, R. Estimation of Water Quality Parameters through a Combination of Deep Learning and Remote Sensing Techniques in a Lake in Southern Chile. Remote. Sens. 2023, 15, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, J.; Chu, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, G. Interpretable Machine Learning Based Quantification of the Impact of Water Quality Indicators on Groundwater Under Multiple Pollution Sources. Water 2025, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Xu, N.; Cui, X.; Wu, T. Interpretable prediction, classification and regulation of water quality: A case study of Poyang Lake, China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 951, 175407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadkani, S.; Hemmatzadeh, Y.; Saber, A.; Sergini, M.M. Enhanced predictive modeling of dissolved oxygen concentrations in riverine systems using novel hybrid temporal pattern attention deep neural networks. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzir, S.Y.; Abuzir, Y.S. Machine learning for water quality classification. Water Qual. Res. J. 2022, 57, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, F.; Sekerinski, E.; Han, J.-C.; Zhou, Y. Real-time prediction of river chloride concentration using ensemble learning. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertikh, S.; Boutaghane, H.; Boumaaza, M.; Belaadi, A.; Bouslah, S. Assessment and prediction of water quality indices by machine learning-genetic algorithm and response surface methodology. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 5573–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooladi, M.; Nikoo, M.R.; Mirghafari, R.; Madramootoo, C.A.; Al-Rawas, G.; Nazari, R. Robust clustering-based hybrid technique enabling reliable reservoir water quality prediction with uncertainty quantification and spatial analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 362, 121259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghashghaie, M.; Eslami, H.; Ostad-Ali-Askari, K. Applications of time series analysis to investigate components of Madiyan-rood river water quality. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojer, A.K.; Biru, B.H.; Al-Quraishi, A.; Debelee, T.G.; Negera, W.G.; Woldesillasie, F.F.; Esubalew, S.Z. Machine learning and remote sensing based time series analysis for drought risk prediction in Borena Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. J. Arid. Environ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, S. A novel interval decomposition correlation particle swarm optimization-extreme learning machine model for short-term and long-term water quality prediction. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Raj, A.; Yadav, B. Enhancing local-scale groundwater quality predictions using advanced machine learning approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasani, S.S.; Arias, M.E.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Tarabih, O.M.; Welch, Z.; Zhang, Q. Leveraging explainable machine learning for enhanced management of lake water quality. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, D.; Soliman, M.; Ahmed, E.; Hassanien, A.E. An optimized explainable artificial intelligence approach for sustainable clean water. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 25899–25919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufpoor, S.; Jalali, M.; Nikmehr, S.; Shiri, N.; Shiri, J.; Maroufpoor, E. Modeling groundwater quality by using hybrid intelligent and geostatistical methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 28183–28197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.I.; Javed, M.F.; Alqahtani, A.; Aldrees, A. Environmental assessment based surface water quality prediction using hyper-parameter optimized machine learning models based on consistent big data. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 151, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, H.; Salari, M.; Ali, S.A.-J.; Dehrashid, A.A.; Azadi, H. Modeling the total hardness (TH) of groundwater in aquifers using novel hybrid soft computing optimizer models. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Ma, Q.; Huang, S.; Liu, F.; Wan, Z. A hybrid water quality prediction model based on variational mode decomposition and bidirectional gated recursive unit. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 2273–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makumbura, R.K.; Mampitiya, L.; Rathnayake, N.; Meddage, D.; Henna, S.; Dang, T.L.; Hoshino, Y.; Rathnayake, U. Advancing water quality assessment and prediction using machine learning models, coupled with explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques like shapley additive explanations (SHAP) for interpreting the black-box nature. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, M.; Busico, G.; Sirna, M.; Tedesco, D.; Mastrocicco, M. A multi-step approach to evaluate the sustainable use of groundwater resources for human consumption and agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Ko, K.-S.; Yoo, K. A machine learning-based approach to predict groundwater nitrate susceptibility using field measurements and hydrogeological variables in the Nonsan Stream Watershed, South Korea. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Wan, W.; Zhao, J.; Xie, G. Large-scale prediction of stream water quality using an interpretable deep learning approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Duan, S.; Huang, Y.; Cai, J.; Bian, J. Use of interpretable machine learning to identify the factors influencing the nonlinear linkage between land use and river water quality in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 140, 108977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Questions | Justification |

|---|---|

| RQ1. What are the most commonly used AI/ML/DL algorithms for predicting water quality | To establish a general overview of the research topic. |

| RQ2. Which AI/ML/DL algorithm provides the most accurate estimation of water quality? | To identify knowledge gaps in AI/ML/DL prediction models. |

| RQ3. What limitations have been identified in water quality prediction using AI/ML/DL techniques? | To uncover potential research opportunities and future work |

| RQ4. What emerging variants currently exist in AI/ML/DL models for estimating water quality? | To identify current trends in AI/ML/DL techniques for water quality prediction. |

| RQ5. What are the key water quality indicators used to assess natural water sources? | To review and understand the factors that determine water quality. |

| ID | Journals | H Index | TC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Water (Switzerland) | 19 | 1568 |

| 2 | Journal of Hydrology | 18 | 2231 |

| 3 | Environmental Science and Pollution Research | 14 | 803 |

| 4 | Water Research | 10 | 823 |

| 5 | Science of the Total Environment | 9 | 737 |

| 6 | Journal of Environmental Management | 7 | 193 |

| 7 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 6 | 103 |

| 8 | Environmental Monitoring and Assessment | 5 | 115 |

| 9 | Hydrological Processes | 5 | 82 |

| 10 | Process Safety and Environmental Protection | 5 | 147 |

| Ranking | First author | Year | LC1 | GC2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rahim Barzegar | 2020 | 32 | 330 | [86] |

| 2 | Rahim Barzegar | 2016 | 15 | 149 | [87] |

| 3 | Jun Yung Ho | 2019 | 13 | 101 | [88] |

| 4 | Amir Hamzeh Haghiabi | 2018 | 13 | 290 | [38] |

| 5 | Xiaoliang Ji | 2017 | 11 | 10 | [89] |

| 6 | Elham Fijani | 2019 | 10 | 146 | [90] |

| 7 | Sani Isah Abba | 2020 | 9 | 91 | [91] |

| 8 | Muhammed Sit | 2020 | 9 | 273 | [80] |

| 9 | Roohollah Noori | 2015 | 9 | 66 | [92] |

| 10 | Bachir Sakaa | 2022 | 7 | 66 | [93] |

| ID | River | Algorithm | Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yangtze River, China | CNN-LSTM | WQP | [114] |

| 2 | Delaware River Basin, USA | XGB, RF, KNN | WQP | [115] |

| 3 | Sheshui River in Wuhan, China | RF, SSA-CNN-LSTM | WQP | [112] |

| 4 | Vaigai, Madurai, and Tamil Nadu Rivers, India | Optimization algorithm and LSTM | WQP | [116] |

| 5 | Upper Red River Basin (URRB), USA | TL, FFNNs | WQP | [100] |

| 6 | The South Platte River, Colorado, USA | EBM, SWEBM | WQP | [117] |

| 7 | Cauvery River, India | AO-SVM | WQI | [118] |

| 8 | Indian Rivers | DT, RF, GBT, ANN, SVM | WQP | [43] |

| 9 | Cauvery River, India | CNN | WQP | [119] |

| 10 | Han River, South Korea | RF, SVR, XGB, LGB, and a hybrid model. SHAP, LIME | WQI | [120] |

| 11 | Tanjiang River, China | SVR | WQP | [121] |

| 12 | Des Moines, Iowa, and Cedar Rivers, Iowa, USA | LSTM, GRU | WQP | [122] |

| 13 | Mahanadi River, India | LSTM, GRU, XGB | WQI | [123] |

| 14 | Oyster River,New Hampshire, USA | CNN-LSTM | WQP | [124] |

| 15 | Li River and Liu River, China | SSA, GRU, SHAP | WQP | [125] |

| 16 | Fujian River Network, China | WA-LSTM-TL | WQP | [101] |

| 17 | Euphrates River, Iraq | RC, DR, REPT, AR | WQP | [126] |

| 18 | Ohio River, USA | LSTM | WQP | [109] |

| 19 | USA Rivers | RF | WQP | [127] |

| 20 | Xiaofu River, China | LSTM | WQP | [128] |

| 21 | Lijiang River, China | BPNN, SVR, GRU | WQP | [129] |

| 22 | Drinking water quality, South Korea | LSTM, GRU | WQP | [130] |

| 23 | Indian, Rivers* | DT, LR, Ridge, Lasso, SVR, RF, ET, ANN | WQI | [131] |

| 24 | Júcar River, Spain | RF, XGB, SHAP | WQP | [132] |

| 25 | Bullfrog River, Tampa, Florida USA | SVM, RF, XGB, ANN, SHAP | WQP | [133] |

| 26 | Talar River, Iran | EN, AMT, REPT | WQP | [134] |

| 27 | Wadi Saf-Saf River, Algeria | SMO-SVM, RF | WQI | [93] |

| 28 | Pearl River, China | CEEMDAN -LSTM | WQP | [135] |

| 29 | Fuyang River, China | RF, PLS | WQP | [136] |

| 30 | Synthetic data set Wabash River, USA | SVMR | WQP | [137] |

| 31 | Yamuna River, India | LSTM, SVR, CNN-LSTM | WQP | [31] |

| 32 | Kelantan River, Malaysia | KNN, ANN, DT, RF, GB | WQP | [138] |

| 33 | Langat River, Malaysia | ANN | WQP | [139] |

| 34 | Mid-Atlantic and Pacific Northwest USA, River Basin | SVR, XGB | WQP | [140] |

| 35 | Santiago-Guadalajara River, Mexico | SLR, MLR | WQI | [141] |

| 36 | Danube,Tisa, and Sava Rivers, Vojvodina Province, Serbia | Naïve Bayes algorithm | WQI | [142] |

| 37 | Yamuna River,India | ANFIS–GP, ANFIS–SC | WQP | [143] |

| 38 | Fanno Creek in Oregon, USA | DRNN, SVM, ANN | WQP | [144] |

| 39 | Dongjiang River, China | WT-MLR, WT-SVM, WT-ANN, WT-RF | WQP | [145] |

| 40 | Klang and Penang Rivers, Malaysia | MLP, SVM, RF, BDT | WQI | [146] |

| 41 | Nakdong River, South Korea | CEEMDAN, CSA, MARS | WQP | [147] |

| 42 | Luan River, Tangshan China | 1-DRCNN* , BiGRU | WQP | [148] |

| 43 | Tyhume, Bloukrans, Buffalo Rivers Province of South Africa | ANN, MLP, RBF | WQP | [149] |

| 44 | Kinta River, Malaysia | EANN-GA, EANN, FFNN, NNE | WQI | [150] |

| 45 | Xin’anjiang River, China | CNN-LSTM, CEEMDAN | WQP | [151] |

| 46 | The Juhe River, Sanhe China | PSO-DBN-LSSVR | WQP | [25] |

| 47 | Burnett River, Australia | kPCA, RNN, FFNN, SVR, GRNN | WQP | [152] |

| 48 | Nakdong River, South Korea | CNN-LSTM | WQP | [153] |

| 49 | Sefid Rud River, Iran | W-MGGP, GEP, DWT | WQP | [154] |

| 50 | Talar River, Iran | RF, RFC | WQI | [155] |

| 51 | Yangtze River, Jiangsu, China | IABC-BPNN | WQP | [156] |

| 52 | Klang River, Malaysia | DT | WQI | [88] |

| 53 | Langat River, Malaysia | MLP-FFA | WQP | [157] |

| 54 | Tireh River, Iran | ANN, GMDH, SVM | WQP | [38] |

| 55 | Danube Delta River, Romania | ANN, KNN, BPNN | WQI | [158] |

| 56 | Sefidrood River, Iran | SVM | WQP | [92] |

| 57 | Aji-Chay River, Iran | ANN, ANFIS, WT | WQP | [87] |

| ID | Region | Parameters | Algorithm | Reference |

| 1 | Madrid, Spain | Nitrate concentrations | DT, RF, AdaBoost, ExT | [160] |

| 2 | Songyuan City, China | Strontium (Sr2+) | GAN, KNN, GPR | [161] |

| 3 | Mekong Delta región, Vietnam | Salinity levels | Bagging, CatBoost, ExT, HGB*, XGB, DT, RF, LightGBM, KNN, SHAP | [162] |

| 4 | Eden Valley, Cumbria, North West England | Nitrate concentrations | DT, XGB, RF, KNN, SHAP | [163] |

| 5 | Kerala, India | EWQI | XGB, SVR, ANN, RF | [47] |

| 6 | The Mitidja plain, northern Algeria | IWQI | LSTM | [164] |

| 7 | Groundwater dataset | Salinity levels | GMDH algorithm | [165] |

| 8 | Tamil Nadu, India | IWQI | SVM, ANN, LRM, RT, GPR, BRT | [166] |

| 9 | North China Plain, Beijing | Arsenic (As) and fluoride (F−) concentrations | XGB, RF, SVM, | [167] |

| 10 | Eastern India | WQI | MLP-ANN | [168] |

| 11 | Raipur district, Chhattisgarh, India | WQI | ANN-LR | |

| 12 | Midwestern United States | Redox Conditions | GBM, XGB, RF | [169] |

| 13 | Hawasinah catchment Wilayat Al-Khaburah, Oman | TDS | CatBoost regression, ExT regression, Bagging regression | [170] |

| 14 | Vehari, Punjab Province of Pakistan | WQI | ANN, RF, LR | [171] |

| 15 | Northeast of Tamil Nadu, India | WQI | GB, RF, DT, KNN, MLP, XGB, SVR | [172] |

| 16 | Qom City, Iran | Nitrate concentration | KNN, SVR, RF | [173] |

| 17 | Savar, Dhaka district, Bangladesh | GWQI* | LR, SVM, ANN | [174] |

| 18 | Al Qunfudhah, Saudi Arabia | WQI | CNN, XGB, SHAP | [175] |

| 19 | Fars Province, Iran | WQI | RF, BRT, MnLR | [176] |

| 20 | Wendeng District, China | WQI | LSTM | [177] |

| 21 | Taiwan Groundwater Pollution Monitoring Standard | Heavy Metal Concentrations | SVR, KNN, MLP, GBR, LIME, SHAP | [178] |

| 22 | Middle Black Sea Region of Turkey | WQP | CNN, RF, XGB, DNN | [179] |

| 23 | Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India | WQP | MLR, SVR, DT | [180] |

| 24 | The Akot basin, Akola district of Maharashtra, India | IWQI | ANN, LSTM, MLR | [181] |

| 25 | North Carolina, USA | Nitrate concentrations | RF | [182] |

| 26 | Dezful Aquifer, Iran | TDS | RF | [183] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).