3. Results

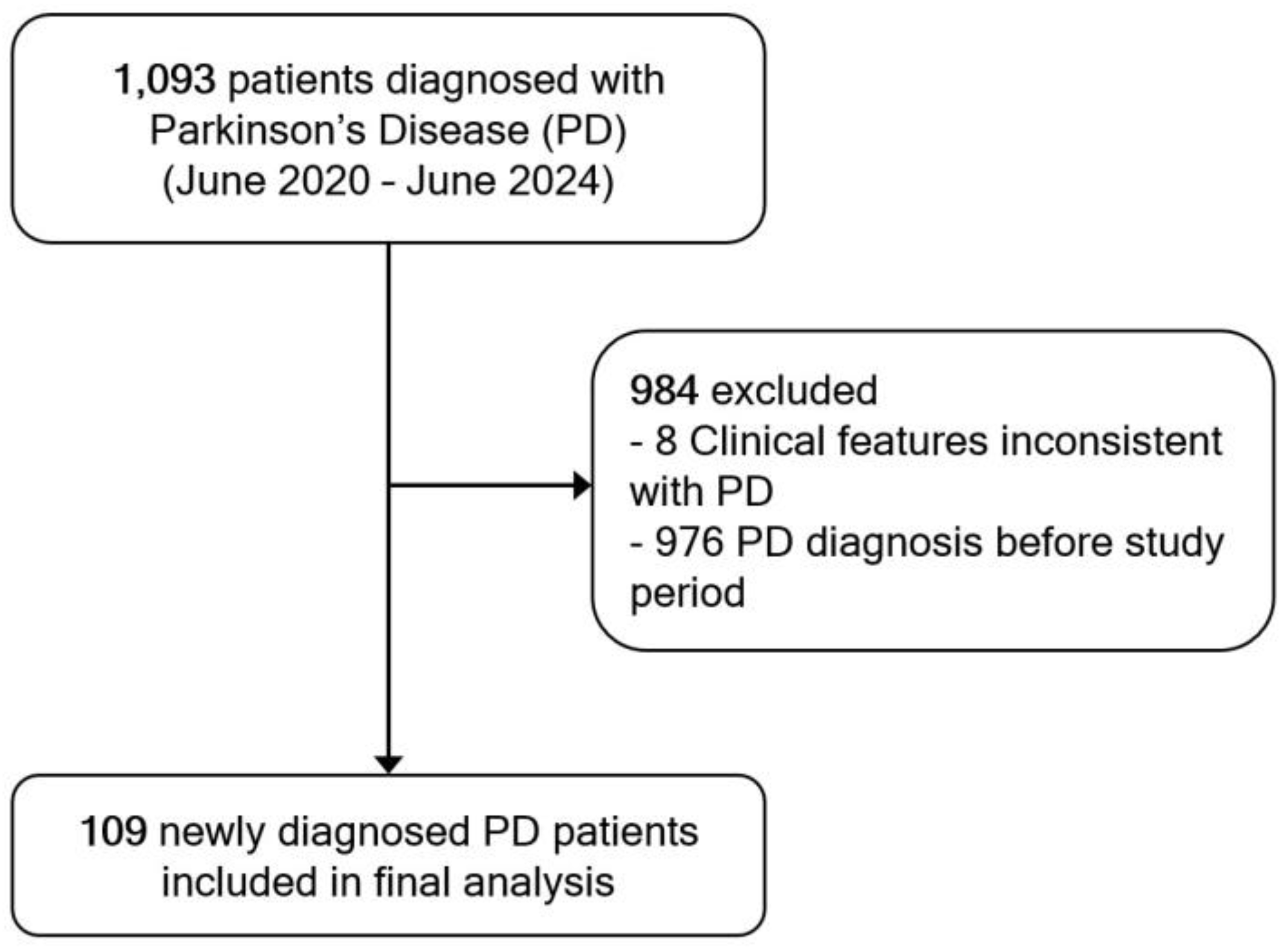

A total of 1,093 patients were diagnosed with PD during the study period. Of these, 976 patients were excluded due to a prior PD diagnosis before the study period, and 8 patients were excluded due to clinical features inconsistent with a probable PD diagnosis upon review. As a result, 109 newly diagnosed patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (

Figure 1).

The cohort exhibited a slight male predominance (59.63%). The mean age at motor symptom onset was 69.13 ± 9.29 years. Most patients (62.38%) were covered by the Civil Servant Medical Benefit scheme (CSMBS), followed by self-pay/private insurance (16.51%) and the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) (15.59%). A family history of PD was documented in 46.79% of cases; 11.76% had a positive family history. Approximately 75.23% of patients resided within 80 km of the hospital. Regarding initial healthcare access, 62.39% of patients were first assessed by non-neurologists in outpatient clinics, whereas only 37.61% were directly evaluated by neurologists (

Table 1).

Movement disorder specialists confirmed the diagnosis in 55.05% of cases, followed by general neurologists (39.45%), internal medicine physicians (4.59%), and general practitioners (0.92%). The median duration from motor symptom onset to the first medical visit (onset-to-visit interval, OTV) was 360 days (IQR 150-720), while the median time from first visit to confirmed diagnosis (visit-to-diagnosis interval, VTD) was 10 days (IQR 1-30). The median duration to PD diagnosis was significantly shorter in patients who were initially assessed by neurologists, whereas the median OTV interval did not differ significantly between groups (

Table 2).

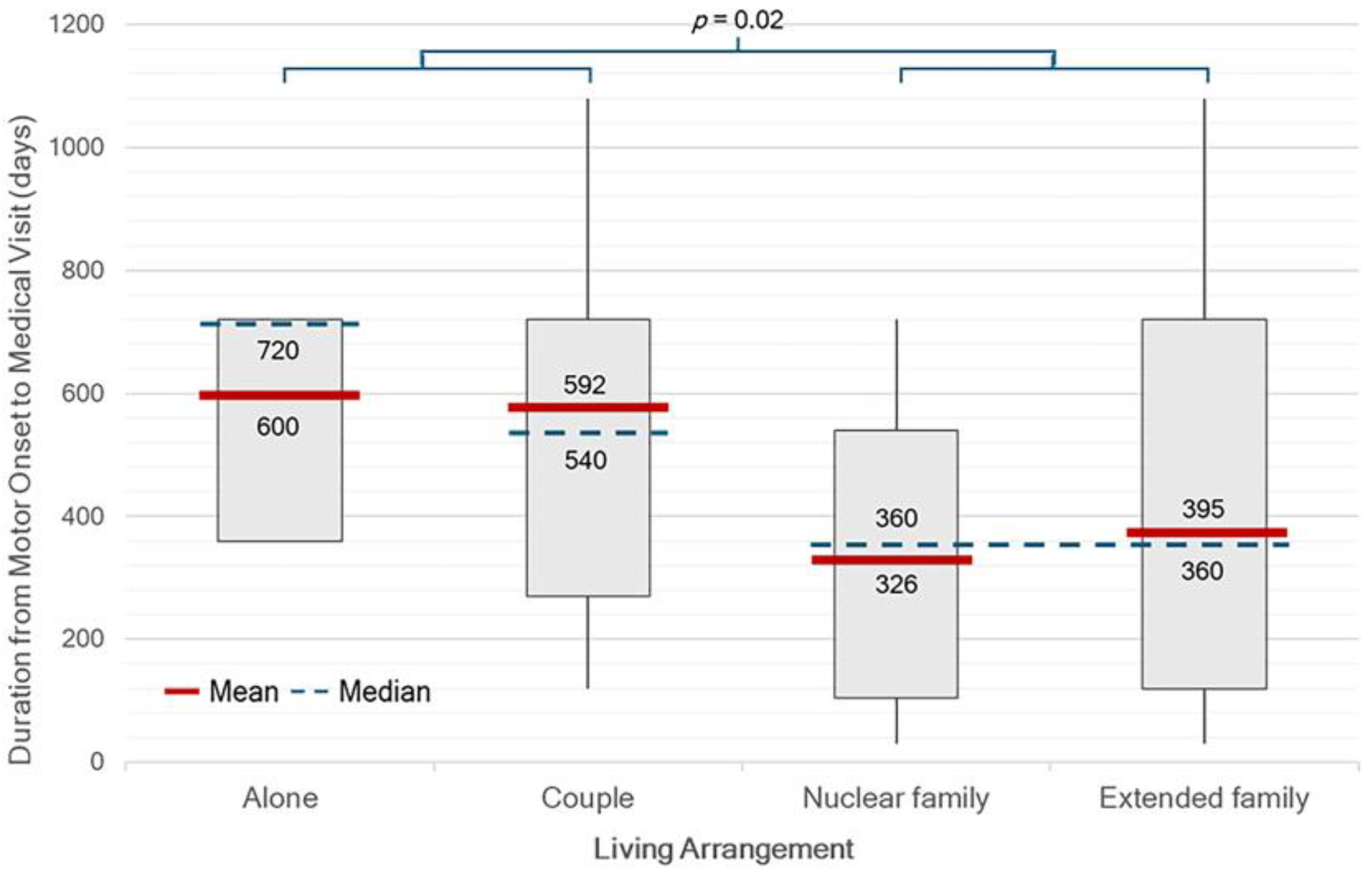

There were significant differences in median OTV interval between single or couple household and family household (p = 0.02) (

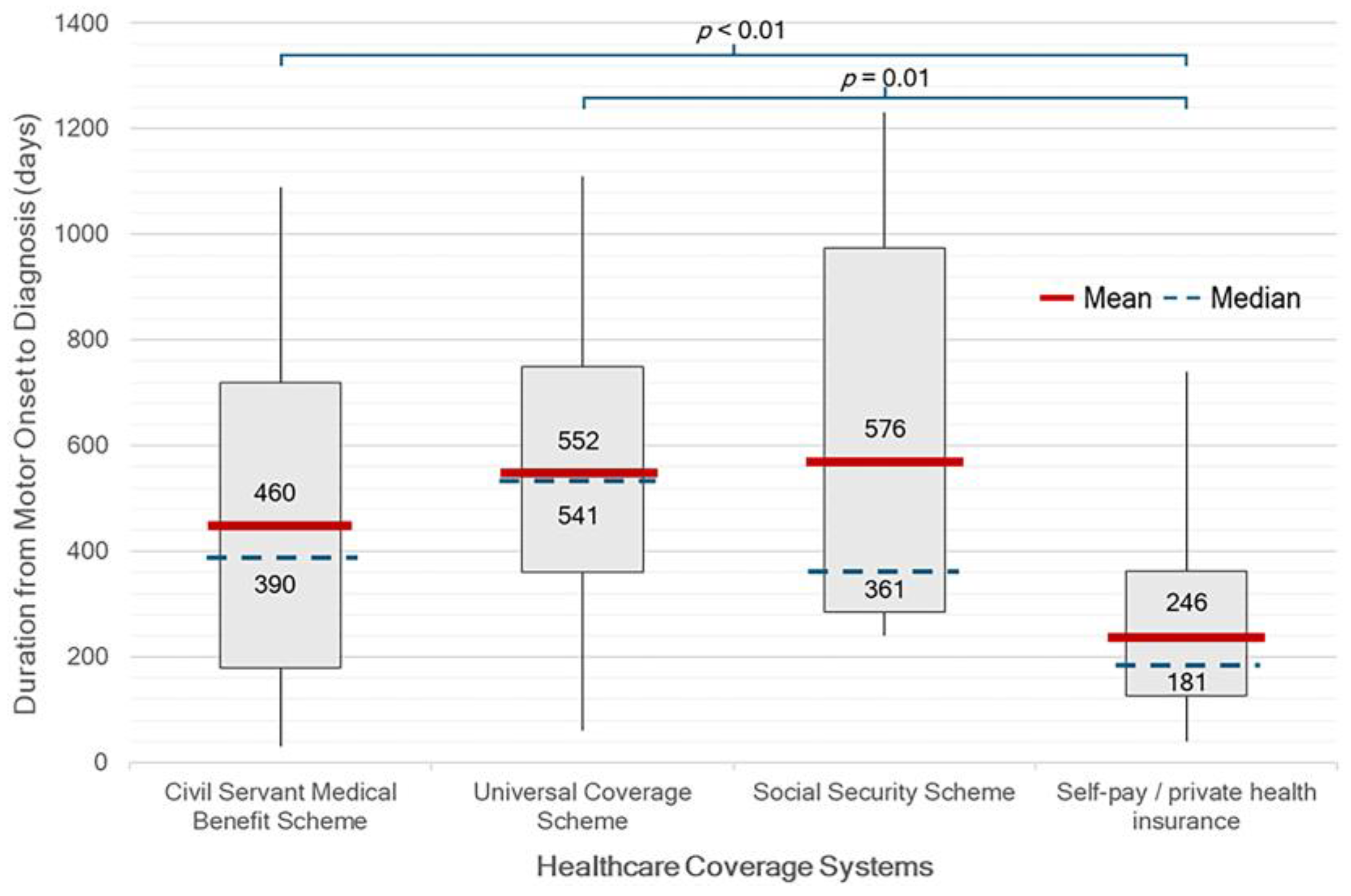

Figure 2). Patients who self-pay or with private insurance had a significantly shorter median duration of 181 days (IQR 127-362), from symptom onset to diagnosis (onset-to-diagnosis interval, OTD) compared to those under other healthcare schemes (p < 0.01). On the other hand, patients receiving care under the UCS had the longest median duration of 541 days (IQR 361-750) (

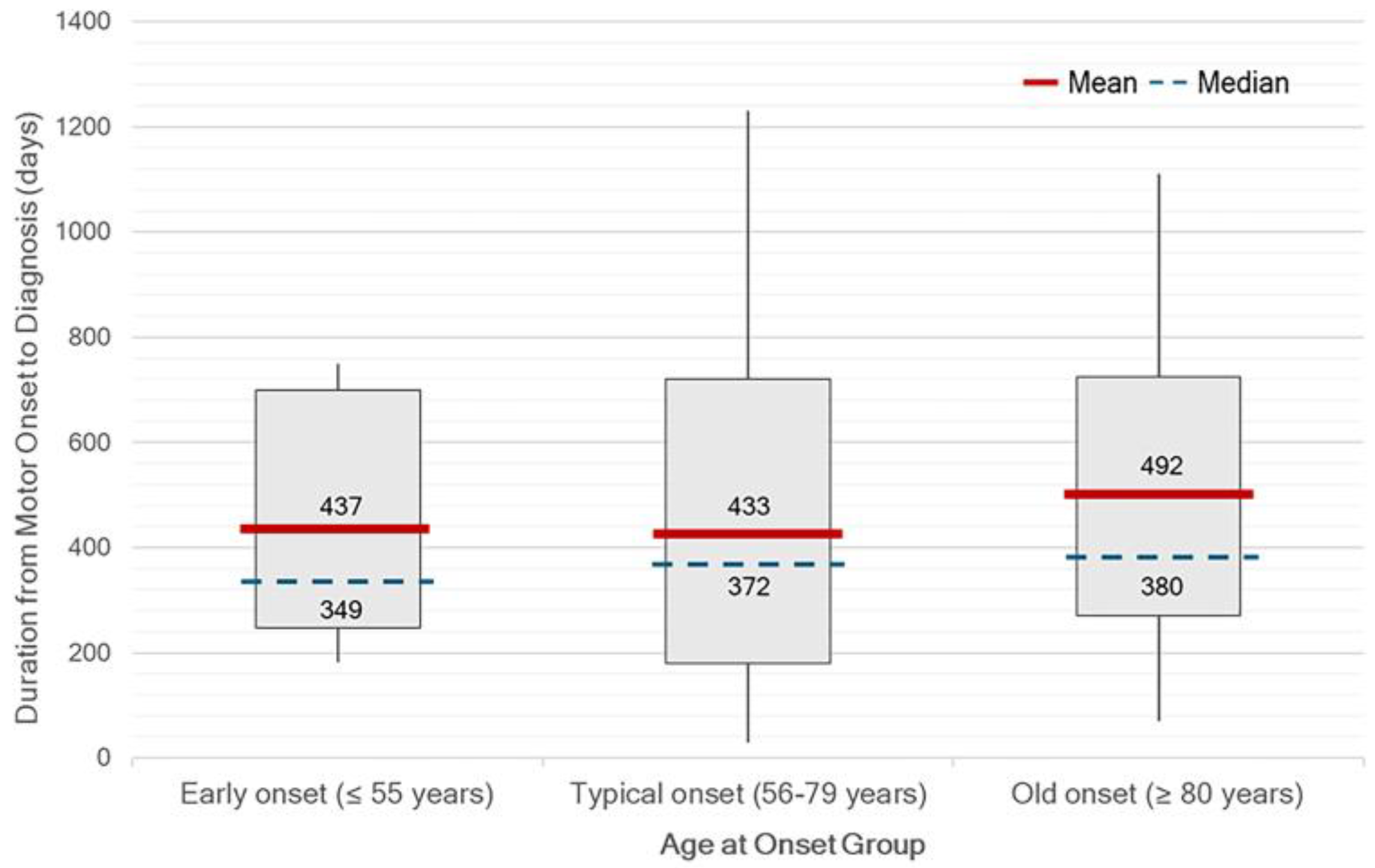

Figure 3). There was no statistically significant difference in median OTD between age at onset group. Although not statistically significant, diagnostic delays tended to be longer in patients with very late-onset PD (

Figure 4). No significant differences in OTV duration, VTD duration, age at onset, or HY stage were found between male and female patients.

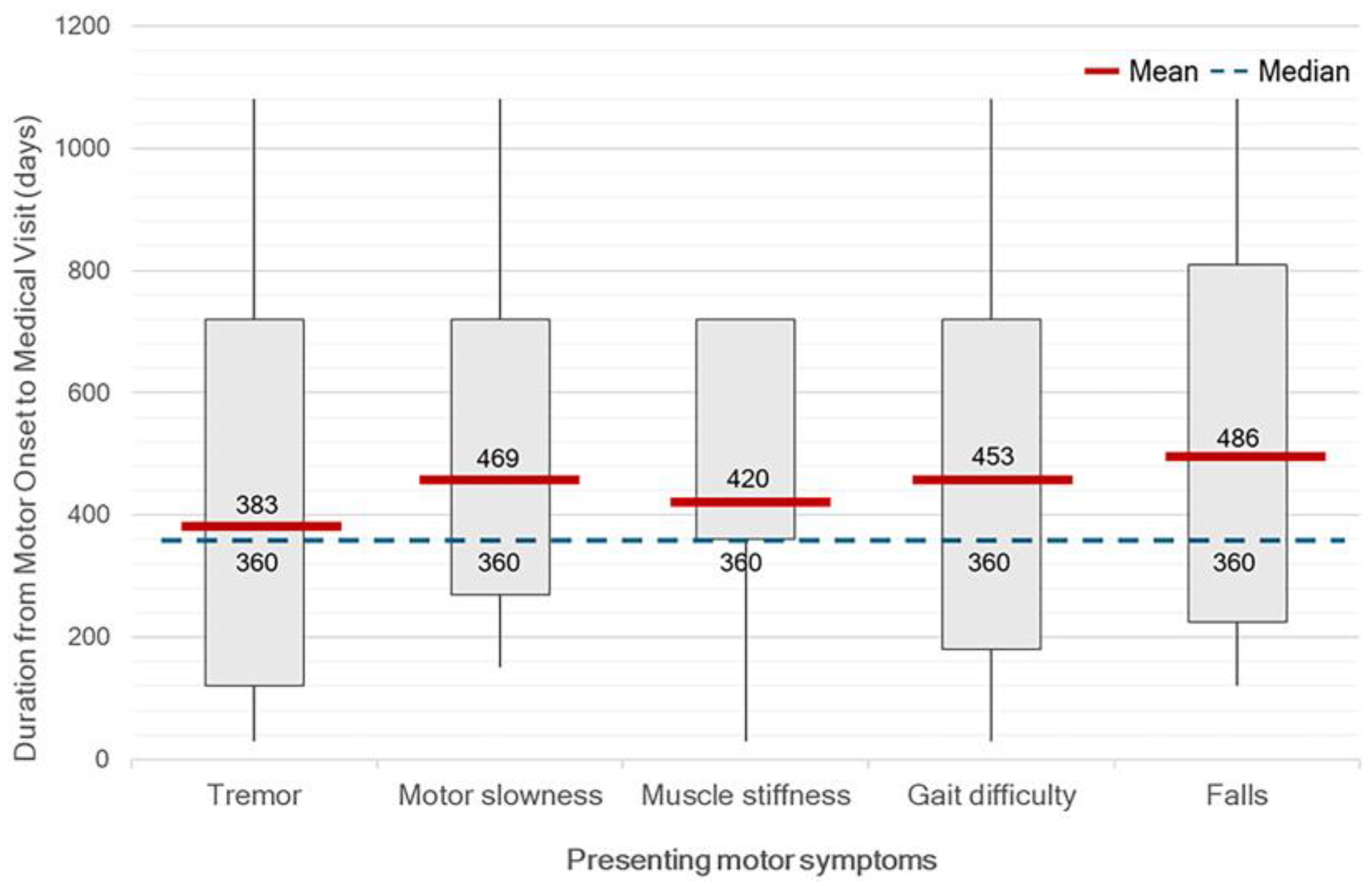

At the time of diagnosis, the median HY stage was 2 (range, 1–4). Only 32.10% of patients were HY stage 1, while 9.17% were diagnosed at advanced stages (HY stage 3-4). Unilateral motor symptom predominance was observed in 93.57% of patients, with predominantly on the right side (52.29%). Tremor was the most common initial symptom, reported in 75.22% of patients, followed by gait difficulty (38.45%), slowness of movement (37.61%), muscle stiffness (16.51%), and falls (9.17%). No significant differences in OTV duration were found across different initial motor symptoms. However, patients with tremor were likely to have a clinical visit earlier than others. (

Figure 5). On neurological examination, bradykinesia was identified in 85.32% of patients, resting tremor in 80.73%, rigidity in 73.39%, and postural instability in 22.02%. A significant discrepancy was observed between self-reported slowness of movement and bradykinesia identified during clinical examination (p < 0.01).

Among non-motor symptoms, constipation was the most prevalent (32.11%), followed by rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) (23.85%), anxiety (12.84%), insomnia (12.84%), and depression (4.58%).

Regarding imaging for diagnosis, approximately one-third of patients (30.28%) did not undergo any neuroimaging studies. Among those who did, brain MRI (47.71%) was more frequently performed than CT (22.02%). Levodopa was the most initiated treatment following diagnosis, prescribed in 88.07% of patients, followed by dopamine agonist in 11.01%, and no treatment (0.92%).

In 55.96% of patients, initial parkinsonian features were not recognized as such. The most common alternative diagnoses included tremor disorders (21.10%), orthopedic conditions (17.76%), and ischemic stroke (6.42%) (

Table 3). The rate of initially unrecognized parkinsonism was significantly higher among patients first evaluated by non-neurologists compared to neurologists (81.97% vs. 18.03%, p < 0.01). Furthermore, patients who initially presented with muscle stiffness (77.78% vs. 51.65%, p = 0.04) and gait difficulty (69.05% vs. 47.76%, p = 0.03) were more likely to be misdiagnosed.

Correlation coefficients analysis revealed a moderate negative correlation between the OTV duration and years of education (r = -0.37, p < 0.01). Weak positive correlations were observed between OTV duration and isolated living arrangement (r= 0.29, p = 0.02) and bilateral motor symptom involvement (r = 0.26, p = 0.05), HY stage at diagnosis (r = 0.19, p = 0.04), and the presence of slowness of movement (r = 0.20, p = 0.04). For the VTD interval, a moderate positive correlation was found with initial assessment by non-neurologists (r = 0.38, p < 0.01), and a mild positive correlation was noted for the presence of rigidity symptoms (r = 0.22, p = 0.02).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the longest delay in the diagnostic process for PD occurs between the onset of motor symptoms and the patient’s decision to seek medical attention. On average, patients waited approximately 12 months before their first medical consultation, underscoring delays in early symptom recognition and potential barriers to accessing healthcare services in Thailand. Compared to earlier Western studies conducted over a decade ago, which reported median durations of 4 months in New York City and 11 months in Cambridge [

5,

6]. The delay observed in our contemporary Thai cohort is notably longer, despite overall improvements in global health literacy and healthcare infrastructure.

In contrast, the median duration from the first medical visit to diagnosis in our cohort was relatively short. The overall duration was 10 days, and among patients who were initially assessed by non-neurologists, the median duration was 30 days. These intervals are comparable to the one- to three-month diagnostic delays reported in previous Western studies [

5,

6]. This finding suggests that the referral and diagnostic process within our hospital is relatively efficient. However, it is important to note that this study was conducted in a tertiary university hospital, where neurologists and movement disorder specialists are available on a full-time basis. In general healthcare settings, where access to such specialists is more limited, substantially longer delays in diagnosis can be expected.

We found no gender-related differences in time to PD diagnosis, in contrast to previous studies that report delayed diagnosis in women [

6]. This finding may reflect comparable healthcare-seeking behaviors and more equitable access to medical services between sexes in Thailand. The predominance of elderly male patients in our cohort aligns with the typical demographic profile of PD reported in both Thai and global populations [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Beyond sex-related patterns, social context played a critical role in influencing diagnostic timing. Patients with higher educational attainment and those living in extended family settings, common in Thai and other Asian societies, were more likely to seek medical attention earlier. This may be attributed to greater disease awareness or, at minimum, the presence of family members who could recognize early symptoms and encourage evaluation. As a result, these individuals were more likely to receive a timely diagnosis, underscoring the importance of both individual and familial factors in promoting early recognition of PD symptoms. In addition, cultural factors also contribute to delays. In Thai society, patients often tolerate mild or non-disabling symptoms and avoid seeking medical care until symptoms become more severe or disruptive. This reluctance may be reinforced by fear of diagnosis, concerns about treatment costs, or the perceived inconvenience of hospital visits. Such health-seeking behaviors likely prolong the onset-to-visit interval and delay timely recognition of PD.

Healthcare entitlement also emerged as a key determinant of diagnostic delay. Patients who paid out-of-pocket or held private insurance experienced a significantly shorter median interval from symptom onset to diagnosis compared to those enrolled in other benefit schemes, particularly the UCS. Although UCS is Thailand’s national insurance program intended to ensure universal access regardless of socioeconomic status, its multi-tiered referral system can create delays before patients reach specialist care. In contrast, patients with financial flexibility or access to streamlined schemes such as the CSMBS may more readily consult neurologists or tertiary care centers, leading to earlier diagnosis. Indeed, CSMBS was the most common healthcare coverage among patients in this cohort, indicating that many had full reimbursement for medical expenses. This likely contributed to the relatively shorter diagnostic timelines observed in our study population, compared to what might be expected in the broader Thai population.

Educational level and household income also appear to contribute meaningfully to diagnostic disparities. Lower education levels in older generations may partly explain reduced symptom recognition, consistent with the observed correlation between education and diagnostic delay. Household income data, while incomplete, revealed that over half of the patients had a monthly income below 50,000 THB. These lower-income patients are more likely to be covered under UCS, further compounding diagnostic delays due to structural barriers.

Taken together, these findings illustrate how disparities in education, income, and healthcare coverage intersect to shape the diagnostic journey of PD patients. Addressing these systemic inequities through public health education, enhanced primary care screening, and more efficient referral mechanisms, particularly within the UCS, will be essential in promoting earlier diagnosis and ensuring more equitable brain health outcomes.

A family history of PD was documented in fewer than half of the patients, which may be attributable to incomplete medical records or insufficient emphasis on family history during clinical assessment. Nevertheless, the proportion of patients with a confirmed positive family history was consistent with previous reports [

5,

7]. Although the majority of PD cases are considered sporadic, they are likely influenced by complex interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental factors [

9]. Documenting family history may provide valuable insights into hereditary risk and facilitate the identification of genetic variants and inheritance patterns in future research.

This study identified substantial variation in the distance between patients’ residences and the hospital, ranging from within the same province to other provinces and even across regions. These differences may reflect disparities in healthcare coverage. Patients receiving care under the UCS were generally referred from nearby provincial hospitals, whereas those covered by the CSMBS or those who self-paid were more likely to choose their healthcare providers based on the hospital’s reputation and the availability of specialists. These findings suggest that healthcare entitlement plays an important role in determining both referral patterns and access to expert care.

Interestingly, parkinsonian features were initially unrecognized or misdiagnosed in more than half of patients with PD, most commonly by non-neurologists during their first medical assessment. Patients who were presented with unilateral muscle stiffness and gait difficulty were frequently misdiagnosed as stroke or other orthopedic conditions. Initial misdiagnosis not only delays appropriate treatment but may also result in unnecessary medication use, excessive diagnostic investigations, and unwarranted surgical interventions. These findings underscore the urgent need to improve awareness and diagnostic proficiency related to PD among a broader range of healthcare providers. Movement disorder specialists and neurologists played a pivotal role in establishing an accurate diagnosis of PD. Therefore, expanding access to neurologists and movement disorder specialists, along with implementing efficient consultation and referral systems, is crucial for ensuring early and accurate diagnosis of PD.

In terms of motor symptoms, tremor was the most common presenting feature in this study, consistent with previous findings [

5,

10]. It often served as the main symptom prompting patients to seek medical attention and guiding physicians toward a diagnosis of PD. However, it is important to recognize that tremor is not required for diagnosis, as approximately 15 to 20 percent of patients with PD do not exhibit tremor [

10]. Additionally, patients with young-onset PD associated with gene mutations, such as PRKN (Parkin) mutations, may exhibit slower disease progression, dystonic features involving the lower limbs, and often an absence of tremor. These atypical clinical presentations may contribute to diagnostic delays [

11,

12].

Notably, a clear discrepancy was observed between self-reported slowness of movement and bradykinesia identified during clinical examination. This highlights the under-recognition of subtle or mild bradykinetic symptoms by patients. In addition, patients with very late-onset PD appeared to be diagnosed later than those in other age groups. This may reflect a tendency to attribute symptoms to the normal aging process rather than to a pathological condition. These findings emphasize the need to improve both public and clinical awareness of non-tremor motor manifestations of PD. Additionally, approximately half of the patients were diagnosed at a moderate stage, as indicated by HY stage 2. This suggests that the symptoms prompting medical consultation often emerge at a later stage of the disease, typically when bilateral motor involvement has already developed. Therefore, greater emphasis should be placed on the recognition of early-stage symptoms, including those in the prodromal phase.

In terms of non-motor symptoms (NMS), the prevalence observed in this study was lower than previously reported [

6], suggesting potential under-recognition or under-documentation of NMS by physicians. A comprehensive evaluation of NMS should be an integral part of routine clinical PD assessment. Continuing medical education on the broad spectrum of PD manifestation is essential to improve diagnostic accuracy and optimize patient care.

Regarding the use of neuroimaging in diagnosis, approximately 30% of patients did not undergo any brain imaging studies. This is consistent with clinical practice when the presentation is typical and fulfills established diagnostic criteria. In such cases, neuroimaging may be deemed unnecessary, particularly in settings where resources are limited.

In the context of diagnostic disparities, biomarkers offer a promising avenue for improving early recognition of PD [

13]. While traditional imaging biomarkers such as DAT-SPECT remain costly and limited in availability, emerging digital biomarkers present a more scalable and accessible alternative, particularly in middle-income countries like Thailand. According to DataReportal 2024 report, Thailand has a high rate of smartphone usage, particularly among adults [

14], making the country well-positioned to leverage mobile health technologies to support early detection of PD. A nationwide digital health initiative, such as a “Check PD” campaign targeting individuals aged 40 and older, could empower at-risk individuals to self-screen using a smartphone-based application [

15]. Such a platform could integrate validated tools to assess voice changes, tremor, dexterity, gait, and postural balance, enabling early identification of subtle motor abnormalities long before individuals seek medical attention [

2]. By using objective digital data and machine learning algorithms, this approach may reduce reliance on subjective symptom reporting and mitigate disparities caused by inconsistent clinical expertise, especially in rural or under-resourced areas.

Equally important is the need to improve awareness of premotor symptoms such as constipation and RBD, which are recognized clinical biomarkers of prodromal PD. These symptoms are often overlooked by both patients and primary care physicians. Targeted education and training programs could enhance early recognition and timely referral. The locally developed NMSQ Application [

16], which enables patients to self-assess non-motor symptoms, further demonstrates the potential of digital tools to increase awareness and engagement. While not diagnostic, such platforms can empower users to recognize early warning signs and seek medical advice earlier. Overall, both clinical and digital biomarkers, when combined with education, can serve as diagnostic equalizers, particularly in resource-limited settings. Their integration into national health strategies may significantly improve early PD detection and promote brain health equity.

In this cohort, levodopa was the most frequently initiated treatment, prescribed in almost 90% of patients following diagnosis. This high rate reflects current clinical practice and recommendations, particularly in resource-limited settings where levodopa remains the most effective and accessible therapy for motor symptoms of PD. Its early and widespread use in this population also suggests that most patients presented with sufficiently advanced symptoms to warrant pharmacologic intervention. This further underscores the need for earlier detection and timely referral to minimize functional impairment at treatment initiation.

Despite the apparent familiarity of diagnostic delay issues in PD, the context-specific challenges faced by patients in LMICs like Thailand remain underexplored. Our study highlights how health entitlement schemes, sociocultural dynamics, and systemic referral structures uniquely influence the diagnostic journey in this population. By providing empirical data from a Southeast Asian context, this research reinforces the critical need for localized evidence to inform equitable healthcare policies. In doing so, it contributes to the overarching goal of the Brain Health for All Ages: Leave No One Behind. Addressing diagnostic delays in PD represents a “known but neglected” problem, one that requires continuous scrutiny and inclusive solutions to ensure that marginalized populations are not overlooked in global health strategies. Together, these approaches can reduce diagnostic delays, expand access to specialist care, and advance equitable brain health outcomes in Thailand.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the retrospective design may be subject to missing data and documentation bias. Nonetheless, the application of standardized diagnostic criteria and the use of structured data abstraction enhanced the consistency and reliability of clinical information. Second, the study was conducted at a single tertiary care hospital, which may limit its generalizability. However, as a major referral center serving both urban and rural populations, Thammasat University Hospital provides a valuable setting for evaluating real-world diagnostic pathways. Its wide catchment area and diverse patient population offer insights into healthcare access challenges that are likely relevant to other resource-constrained environments. Third, although the sample size was modest, it was drawn from a clearly defined cohort of newly diagnosed PD patients, allowing for robust analysis of diagnostic intervals, symptomatology, and system-level influences.