Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

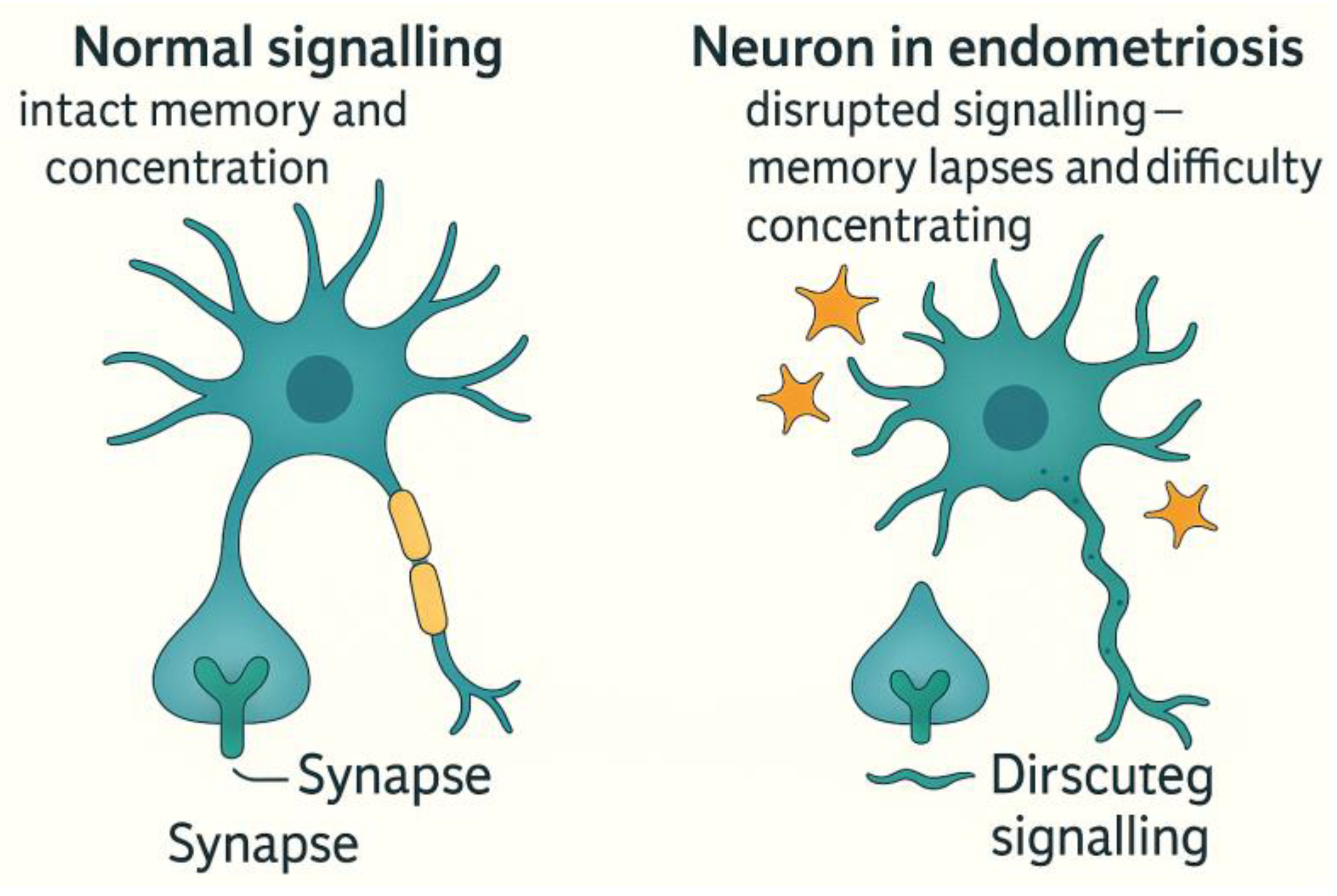

Chronic Pain Processing: Neuroplastic Changes and Central Sensitisation in Endometriosis

Methods

Study Design

Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Study Selection and Screening

Data Extraction

Quality Appraisal

Data Synthesis

Results

Women’s Mental Health: Depression, Cognition and Quality of Life

Endometriosis: Cognitive, Neurological, and Psychological Impact

Mental Health Correlations

RLS in Endometriosis Patients

Clinical Relevance and Life Impact.

Global and Regional Considerations

Menopause: Hormonal Transitions and the Brain

Cognitive Symptoms and Functional Impact

RLS and Menopausal Hormones

Hormone Therapy (HT): Cognitive Potential and Limitations

Mental Health and Vasomotor Symptoms

Intersectionality and Social Determinants

Workplace and Policy Implications

PCOS and Neurological Impact

Social Determinants and Policy

Bladder Function and Neurology

Neuroanatomy of Bladder Control

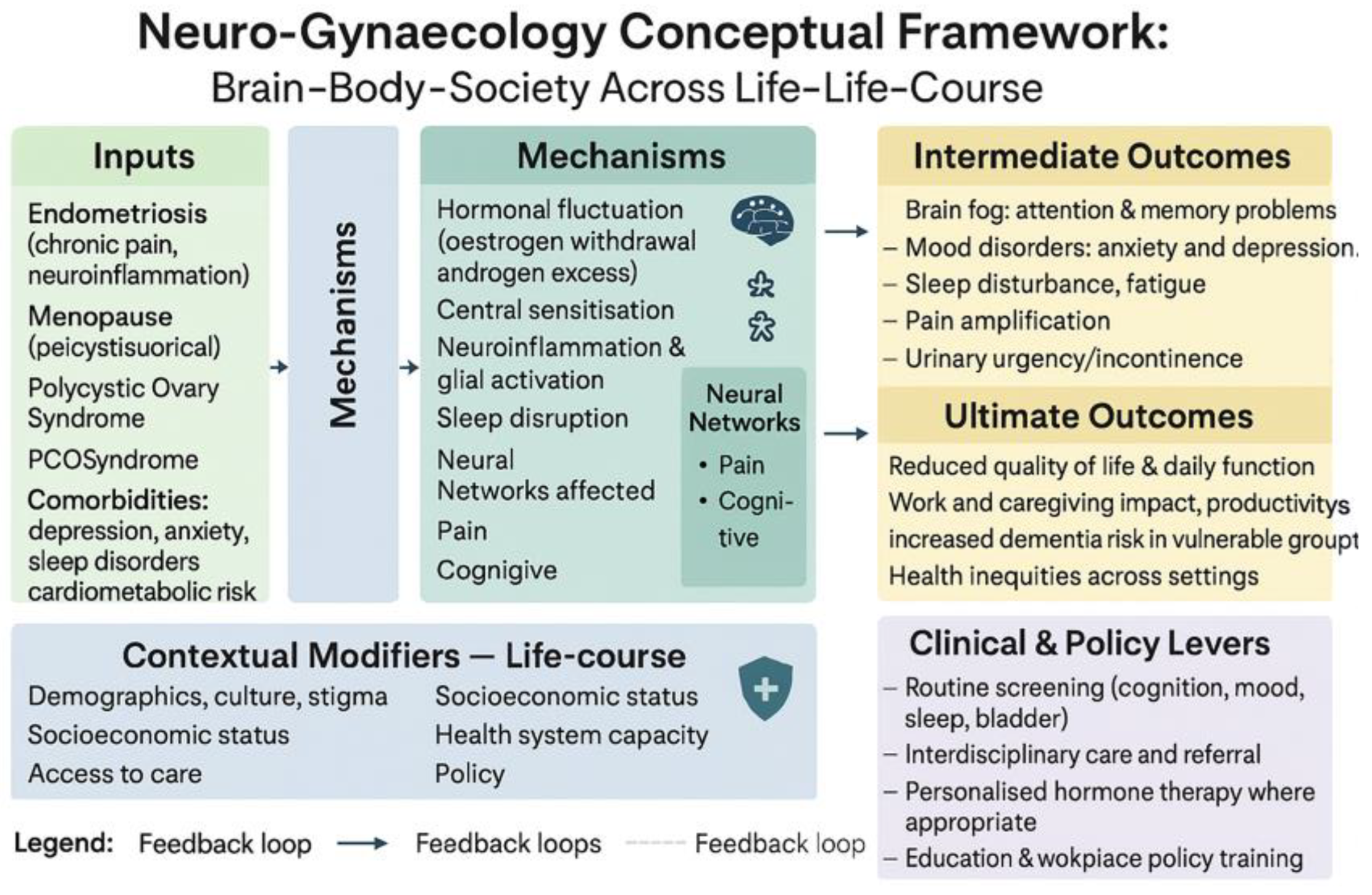

The Neuro-Gynaecology Conceptual Framework

Discussion

Neurological Impact and Central Sensitisation

Bladder Dysfunction: The Overlooked Dimension

Health Inequities and Global Considerations

Strengths and limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval

Availability of Data and Material

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

Code availability

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

References

- Li, T.; Mamillapalli, R.; Ding, S.; Chang, H.; Liu, Z.-W.; Gao, X.-B.; Taylor, H.S. Endometriosis alters brain electrophysiology, gene expression and increases pain sensitization, anxiety, and depression in female mice†. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 349–359. [CrossRef]

- Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 May;10(5):261–75. [CrossRef]

- As-Sanie, S.; Kim, J.; Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Sundgren, P.C.; Clauw, D.J.; Napadow, V.; Harris, R.E. Functional Connectivity Is Associated With Altered Brain Chemistry in Women With Endometriosis-Associated Chronic Pelvic Pain. J. Pain 2016, 17, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wessels, J.M.; Leyland, N.A.; Agarwal, S.K.; Foster, W.G. Estrogen induced changes in uterine brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptors. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 925–936. [CrossRef]

- Endometriosis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis.

- Facchin, F.; Barbara, G.; Dridi, D.; Alberico, D.; Buggio, L.; Somigliana, E.; Saita, E.; Vercellini, P. Mental health in women with endometriosis: searching for predictors of psychological distress. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1855–1861. [CrossRef]

- Depressive disorder (depression) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- Women are 40% more likely to experience depression during the perimenopause | UCL News - UCL – University College London [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2024/may/women-are-40-more-likely-experience-depression-during-perimenopause.

- Recognizing the Lesser-Known Symptoms of Depression | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.nami.org/depression-disorders/recognizing-the-lesser-known-symptoms-of-depression/.

- Goveas, J.S.; Espeland, M.A.; Woods, N.F.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Kotchen, J.M. Depressive Symptoms and Incidence of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Probable Dementia in Elderly Women: The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Wesström, J.; Nilsson, S.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Ulfberg, J. Restless legs syndrome among women: prevalence, co-morbidity and possible relationship to menopause. Climacteric 2008, 11, 422–428. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 30. [CrossRef]

- EndoNews.com: News & Research Portal for Endometriosis Foundation of America [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Cognitive Difficulties in Endometriosis. Available from: https://www.endonews.com/cognitive-difficulties-in-endometriosis.

- Berryman, A.; Machado, L. Cognitive Functioning in Females with Endometriosis-Associated Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Literature Review. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2025, 40, 1066–1080. [CrossRef]

- Maulitz, L.; Stickeler, E.; Stickel, S.; Habel, U.; Tchaikovski, S.; Chechko, N. Endometriosis, psychiatric comorbidities and neuroimaging: Estimating the odds of an endometriosis brain. Front. Neuroendocr. 2022, 65, 100988. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.T.; Redden, C.R.; Raj, K.; Arcanjo, R.B.; Stasiak, S.; Li, Q.; Steelman, A.J.; Nowak, R.A. Endometriosis leads to central nervous system-wide glial activation in a mouse model of endometriosis. J. Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 59. [CrossRef]

- World population ageing 2019 [Internet]. New York: UN; 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3907988.

- Epperson, C.N.; Sammel, M.D.; Freeman, E.W. Menopause Effects on Verbal Memory: Findings From a Longitudinal Community Cohort. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 3829–3838. [CrossRef]

- Mosconi L, Berti V, Quinn C, McHugh P, Petrongolo G, Varsavsky I, et al. Sex differences in Alzheimer risk: Brain imaging of endocrine vs chronologic aging. Neurology. 2017 Sept 26;89(13):1382–90. [CrossRef]

- Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, Ahlskog JE, Grossardt BR, de Andrade M, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007 Sept 11;69(11):1074–83. [CrossRef]

- Maki, P.M.; Henderson, V.W. Hormone therapy, dementia, and cognition: the Women's Health Initiative 10 years on. Climacteric 2012, 15, 256–262. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Lahan, V.; Goel, D. Prevalence of restless leg syndrome in subjects with depressive disorder. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 70–3. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.P.; Picchietti, D.L.; Garcia-Borreguero, D.; Ondo, W.G.; Walters, A.S.; Winkelman, J.W.; Zucconi, M.; Ferri, R.; Trenkwalder, C.; Lee, H.B. Restless legs syndrome/Willis–Ekbom disease diagnostic criteria: updated International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) consensus criteria – history, rationale, description, and significance. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 860–873. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, A.; Panay, N. Menopause and the workplace. Climacteric 2014, 17, 317–318. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.W. Associations of depression with the transition to menopause. Menopause 2010, 17, 823–827. [CrossRef]

- WHO Data [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health Data Portal. Available from: https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/mca/global-strategy.

- Bozdag, G.; Mumusoglu, S.; Zengin, D.; Karabulut, E.; Yildiz, B.O. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2841–2855. [CrossRef]

- Hogervorst, E. Effects of Gonadal Hormones on Cognitive Behaviour in Elderly Men and Women. J. Neuroendocr. 2013, 25, 1182–1195. [CrossRef]

- Barry, J.; Kuczmierczyk, A.; Hardiman, P. Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 2442–2451. [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Campbell, R.E. The neuroendocrine genesis of polycystic ovary syndrome: A role for arcuate nucleus GABA neurons. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 160, 106–117. [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, B.; Kronbichler, M.; Nuerk, H.-C.; Kerschbaum, H. Hormonal contraceptives masculinize brain activation patterns in the absence of behavioral changes in two numerical tasks. Brain Res. 2014, 1543, 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Cosar, E.; Cosar, M.; Köken, G.; Sahin, F.K.; Caliskan, G.; Haktanir, A.; Eser, O.; Yaman, M.; Yilmazer, M. Polycystic ovary syndrome is related to idiopathic intracranial hypertension according to magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance venography. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 1245–1246. [CrossRef]

- Ghorayeb, I.; Bioulac, B.; Scribans, C.; Tison, F. Perceived severity of restless legs syndrome across the female life cycle. Sleep Med. 2008, 9, 799–802. [CrossRef]

- Tempest, N.; Boyers, M.; Carter, A.; Lane, S.; Hapangama, D.K. Premenopausal Women With a Diagnosis of Endometriosis Have a Significantly Higher Prevalence of a Diagnosis or Symptoms Suggestive of Restless Leg Syndrome: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 599306. [CrossRef]

- Restless Legs Perimenopause | Restless Legs Menopause [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.mymenopausetransformation.com/restless-leg-syndrome/can-the-right-nutrients-calm-your-jumpy-restless-legs/.

- Pedersini, R.; di Mauro, P.; Amoroso, V.; Castronovo, V.; Zamparini, M.; Monteverdi, S.; Laini, L.; Schivardi, G.; Cosentini, D.; Grisanti, S.; et al. Sleep disturbances and restless legs syndrome in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer given adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Breast 2022, 66, 162–168. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, M.; Tabatabaei, F.-S.; Akbarzadeh, I.; Eftekhar, T.; Hantoushzadeh, S.; Hedayati, F.; Ahmadi, S.; Delbari, A. The sleep quality in women with surgical menopause compared to natural menopause based on Ardakan Cohort Study on Aging (ACSA). BMC Women's Heal. 2025, 25, 100. [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1602–1618. [CrossRef]

- Polycystic ovary syndrome [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/polycystic-ovary-syndrome.

- Chesson, A.L.; Wise, M.; Davila, D.; Johnson, S.; Littner, M.; Anderson, W.M.; Hartse, K.; Rafecas, J. Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder. Sleep 1999, 22, 961–968. [CrossRef]

- Trenkwalder C, Allen R, Högl B, Paulus W, Winkelmann J. Restless legs syndrome associated with major diseases: A systematic review and new concept. Neurology. 2016 Apr 5;86(14):1336–43. [CrossRef]

- Avis, N.E.; Colvin, A.; Karlamangla, A.S.; Crawford, S.; Hess, R.; Waetjen, L.E.; Brooks, M.; Tepper, P.G.; Greendale, G.A. Change in sexual functioning over the menopausal transition: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause 2017, 24, 379–390. [CrossRef]

- Hall L, Callister LC, Berry JA, Matsumura G. Meanings of menopause: cultural influences on perception and management of menopause. J Holist Nurs. 2007 June;25(2):106–18. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.; MacLennan, S.J.; Hassard, J. Menopause and work: An electronic survey of employees’ attitudes in the UK. Maturitas 2013, 76, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Women’s Health Strategy for England. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/womens-health-strategy-for-england/womens-health-strategy-for-england.

- March, W.A.; Moore, V.M.; Willson, K.J.; Phillips, D.I.; Norman, R.J.; Davies, M.J. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 25, 544–551. [CrossRef]

- Cooney, L.G.; Lee, I.; Sammel, M.D.; Dokras, A. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1075–1091. [CrossRef]

- Pastor, C.L.; Griffin-Korf, M.L.; Aloi, J.A.; Evans, W.S.; Marshall, J.C. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Evidence for Reduced Sensitivity of the Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Pulse Generator to Inhibition by Estradiol and Progesterone1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 582–590. [CrossRef]

- Wild, R.A.; Rizzo, M.; Clifton, S.; Carmina, E. Lipid levels in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1073–1079.e11. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, E.A.; Pasch, L.A.; Cedars, M.I.; Legro, R.S.; Eisenberg, E.; Huddleston, H.G. Insulin resistance is associated with depression risk in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Teede HJ, Tay CT, Laven JJE, Dokras A, Moran LJ, Piltonen TT, et al. Recommendations From the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023 Sept 18;108(10):2447–69. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.; Tadic, S.D. Bladder control, urgency, and urge incontinence: Evidence from functional brain imaging. Neurourol. Urodynamics 2007, 27, 466–474. [CrossRef]

- Komesu YM, Ketai LH, Mayer AR, Teshiba TM, Rogers RG. Functional MRI of the Brain in Women with Overactive Bladder: Brain Activation During Urinary Urgency. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Aug 31];17(1):50–4. [CrossRef]

- Campin L, Borghese B, Marcellin L, Santulli P, Bourret A, Chapron C. [Urinary functional disorders bound to deep endometriosis and to its treatment: review of the literature]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2014 June;43(6):431–42. [CrossRef]

- Kölükçü E, Gülücü S, Erdemir F. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and polycystic ovary syndrome. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31];69(5):e20221561. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.; Cardozo, L.D. The role of estrogens in female lower urinary tract dysfunction. Urology 2003, 62, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Wein, A.J.; Tubaro, A.; Sexton, C.C.; Thompson, C.L.; Kopp, Z.S.; Aiyer, L.P. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009, 103, 4–11. [CrossRef]

- Sukhu, T.; Kennelly, M.J.; Kurpad, R. Sacral neuromodulation in overactive bladder: a review and current perspectives. Res. Rep. Urol. 2016, ume 8, 193–199. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Andersson, K.; Apostolidis, A.; Birder, L.; Bliss, D.; Brubaker, L.; Cardozo, L.; Castro-Diaz, D.; O'COnnell, P.; Cottenden, A.; et al. 6th International Consultation on Incontinence. Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and faecal incontinence. Neurourol. Urodynamics 2018, 37, 2271–2272. [CrossRef]

- Harlow, B.L.; Wise, L.A.; Stewart, E.G. Prevalence and predictors of chronic lower genital tract discomfort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 545–550. [CrossRef]

- van Rysewyk, S.; Blomkvist, R.; Chuter, A.; Crighton, R.; Hodson, F.; Roomes, D.; Smith, B.H.; Toye, F. Understanding the lived experience of chronic pain: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative evidence syntheses. Br. J. Pain 2023, 17, 592–605. [CrossRef]

- Berkley KJ, Rapkin AJ, Papka RE. The pains of endometriosis. Science. 2005 June 10;308(5728):1587–9. [CrossRef]

- Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, Sandhu KV, Bastiaanssen TFS, Boehme M, et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev. 2019 Oct 1;99(4):1877–2013. [CrossRef]

- Howard FM. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Mar;101(3):594–611.

- Giudice, L.C.; Oskotsky, T.T.; Falako, S.; Opoku-Anane, J.; Sirota, M. Endometriosis in the era of precision medicine and impact on sexual and reproductive health across the lifespan and in diverse populations. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23130. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, R.; Stewen, K.; Ost, L.; Kottmann, T.; Theis, S.; Elger, T.; Schmidt, M.W.; Anic, K.; Kalb, S.R.; Brenner, W.; et al. Predictors of Psychological Distress in Women with Endometriosis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 4927. [CrossRef]

- Denny, E.; Mann, C.H. Endometriosis and the primary care consultation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 139, 111–115. [CrossRef]

- Seear, K. The etiquette of endometriosis: Stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1220–1227. [CrossRef]

- Jones G, Kennedy S, Barnard A, Wong J, Jenkinson C. Development of an endometriosis quality-of-life instrument: The Endometriosis Health Profile-30. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Aug;98(2):258–64. [CrossRef]

- Gleason, C.E.; Dowling, N.M.; Wharton, W.; Manson, J.E.; Miller, V.M.; Atwood, C.S.; Brinton, E.A.; Cedars, M.I.; Lobo, R.A.; Merriam, G.R.; et al. Effects of Hormone Therapy on Cognition and Mood in Recently Postmenopausal Women: Findings from the Randomized, Controlled KEEPS–Cognitive and Affective Study. PLOS Med. 2015, 12, e1001833. [CrossRef]

- Krystal AD. Insomnia in women. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5(3):41–50. [CrossRef]

- Strategy on women’s health and well-being in the WHO European Region [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2016-4173-43932-61910.

- Wortmann, L.; Oertelt-Prigione, S. Teaching Sex- and Gender-Sensitive Medicine Is Not Just a Matter of Content. J. Med Educ. Curric. Dev. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Details |

| Neuroimaging Findings | - Increased grey matter volume in the insula, thalamus, and anterior cingulate cortex. - Altered connectivity in the Default Mode Network (DMN) and Salience Network. These are associated with pain hypervigilance and cognitive inflexibility. |

| Central Sensitisation Manifestations | - Hyperalgesia: Heightened sensitivity to painful stimuli. - Allodynia: Pain in response to non-painful stimuli (e.g. light touch). - Pain Memory Consolidation: Persistent perception of pain even after the original cause is removed. |

| Comparative Syndromes | Similar CNS patterns observed in fibromyalgia and chronic migraine, indicating that endometriosis belongs to the spectrum of central pain syndromes (5,6). |

| Category | Details |

| Onset and Diagnosis | - Often begins during adolescence. - Diagnosis typically delayed by 6–11 years due to symptom normalisation and lack of awareness (17). |

| Barriers to Diagnosis | - Dysmenorrhea frequently dismissed as normal. - Menstrual pain still stigmatised or minimised in schools and primary healthcare settings. |

| Consequences of Delay | - School absenteeism and academic disruption. - Social isolation and shame surrounding menstruation. - Early invalidation shapes long-term healthcare attitudes. |

| Neurodevelopmental Risk | - Chronic pain during critical brain development may lead to long-term cognitive-emotional dysregulation. |

| Intervention Priorities | - Early recognition and validation of menstrual pain. - Comprehensive pain management. - School-based accommodations and mental health support. |

| Category | Details |

| Persistent Risk Factors | Women may continue to experience symptoms postmenopausal if they: - Use menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) - Have deep-infiltrating lesions - Exhibit central sensitisation from long-standing pain (18). |

| Ongoing Symptoms | - Pelvic pain - Bladder or bowel dysfunction - Psychological distress including low mood, anxiety, and fatigue |

| Neurological Footprint | Long-term changes in brain function due to chronic pain may impact: - Concentration and processing speed - Pain perception - Emotional resilience |

| Ageing-Related Risks | Women with a history of endometriosis may have increased risks of: - Sleep disorders - Depression and anxiety - Reduced cognitive reserve in later life (19) |

| Research Needs | More longitudinal studies are needed to determine the extent of cognitive and emotional sequelae of chronic endometriosis after menopause. |

| Contributing Factor | Description and Impact |

| Iron Deficiency | - Iron is essential for dopamine synthesis in the central nervous system. - In endometriosis, heavy menstrual bleeding, inflammation, or malabsorption can lead to systemic and cerebral iron depletion (23). |

| Chronic Inflammation | - Endometriosis involves chronic pelvic and systemic inflammation. - Elevated cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α may impair dopaminergic signalling and peripheral nerve function, contributing to RLS pathophysiology. |

| Hormonal Fluctuations | - Oestrogen and progesterone regulate dopamine and GABAergic neurotransmission. - Hormonal imbalances in endometriosis may exacerbate or reveal underlying RLS symptoms (23). |

| Sleep Disruption | - Endometriosis-related pain leads to insomnia and fragmented sleep. - RLS symptoms typically worsen at night, compounding sleep loss and increasing fatigue, anxiety, and depression. |

| Category | Details |

| Clinical Clues for RLS | - Insomnia or difficulty falling asleep - Nighttime leg restlessness or discomfort - Unexplained daytime fatigue - Unrefreshing sleep despite adequate duration |

| Recommended Workup | - Ferritin testing (target >75 ng/mL) - Medication review (e.g., antihistamines, SSRIs may worsen symptoms) - Assessment of sleep hygiene and circadian rhythm |

| Management Strategies | - Iron supplementation (oral or intravenous) - Dopaminergic agents (e.g., pramipexole, ropinirole) - Gabapentinoids (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin—helpful with comorbid pain/anxiety) - Sleep behaviour therapy and lifestyle modification (avoid caffeine, alcohol, nicotine) |

| Aspect | Details |

| Neuroprotective Functions of Oestrogen | - Enhances synaptic plasticity and supports memory consolidation - Maintains mitochondrial efficiency for neuronal energy needs - Promotes glucose metabolism in the brain, essential for cognitive performance (30) |

| Neuroimaging Findings in Menopause | - Reduced grey and white matter volumes, especially in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex - Decreased glucose uptake in key brain areas - Increased amyloid-beta deposition, associated with Alzheimer’s disease (31) |

| Clinical Interpretation | Menopause may function as a “neurological transition state,” heightening vulnerability to accelerated brain ageing. |

| High-Risk Groups | Women experiencing early menopause (before age 45) or surgical menopause (e.g., oophorectomy) without hormone therapy are at greater risk of cognitive decline and dementia (32). |

| Domain | Key Findings |

| Cognitive Function | - Lower brain volume in frontal and temporal lobes - Reduced white matter integrity, impairing inter-regional communication - 11–13% lower performance on tasks involving attention, memory, and processing speed (38) - Associated with insulin resistance, obesity, and chronic inflammation - Poor sleep quality (e.g., due to sleep apnoea) worsens cognitive symptoms - Often missed due to focus on cosmetic or fertility issues |

| Mood Disorders and Emotional Health | - 2–3x higher risk of depression, anxiety, dysthymia, and eating disorders (47) - Hormonal imbalances (e.g., high testosterone, LH/FSH disruption) affect serotonin and dopamine - Stigma and appearance concerns cause low self-esteem - Adolescents with PCOS face bullying, school absenteeism, and social isolation, increasing risk of long-term mental illness |

| Neuroendocrine Basis | - PCOS involves elevated GnRH pulse frequency and increased LH, leading to androgen excess (48) - Disrupted HPO axis feedback implies a central role of the brain in PCOS pathogenesis - Brain imaging shows altered activity in corticolimbic circuits (amygdala, nucleus accumbens, anterior cingulate), affecting: reward processing, impulse control, and mood regulation |

| Androgens and Cognition | - High testosterone levels linked to poorer verbal memory and attention (49) - In some young women, mild androgen excess may enhance spatial ability via androgen receptor activity in the hippocampus and PFC - In most cases, particularly with metabolic dysfunction, androgens impair rather than enhance cognition |

| Life-Course Risk | - PCOS is lifelong, starting in adolescence and continuing into older age - Increases risk of: Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome (50–70%) Hypertension and CVD Stroke and cognitive decline {Citation} - Brain MRI in postmenopausal women with PCOS shows white matter lesions, silent infarcts, and microvascular disease - Early intervention may reduce neurovascular ageing |

| Condition | Mechanisms and Effects on Bladder Function |

| Endometriosis and Bladder Symptoms | - Deep infiltrating endometriosis may involve the bladder wall, ureters, or pelvic nerves. - Contributes to painful bladder syndrome or interstitial cystitis. - Chronic inflammation and central sensitisation exacerbate urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia—especially around menstruation. - May mimic recurrent UTIs, leading to misdiagnosis (54). |

| PCOS and Metabolic Contributions | - Obesity and insulin resistance in PCOS are linked to increased rates of urinary incontinence. - Excess abdominal pressure weakens pelvic floor neuromuscular support. - Metabolic inflammation may impact bladder sensory pathways, increasing urgency and frequency (55). |

| Menopause and Urogenital Atrophy | - Oestrogen deficiency causes thinning of bladder and urethral epithelium, reduced vascularity, and loss of collagen. - Results in reduced bladder capacity, increased urgency, and compromised sphincter control. - Neurologically, there is decreased afferent input and delayed cortical inhibitory control (56). |

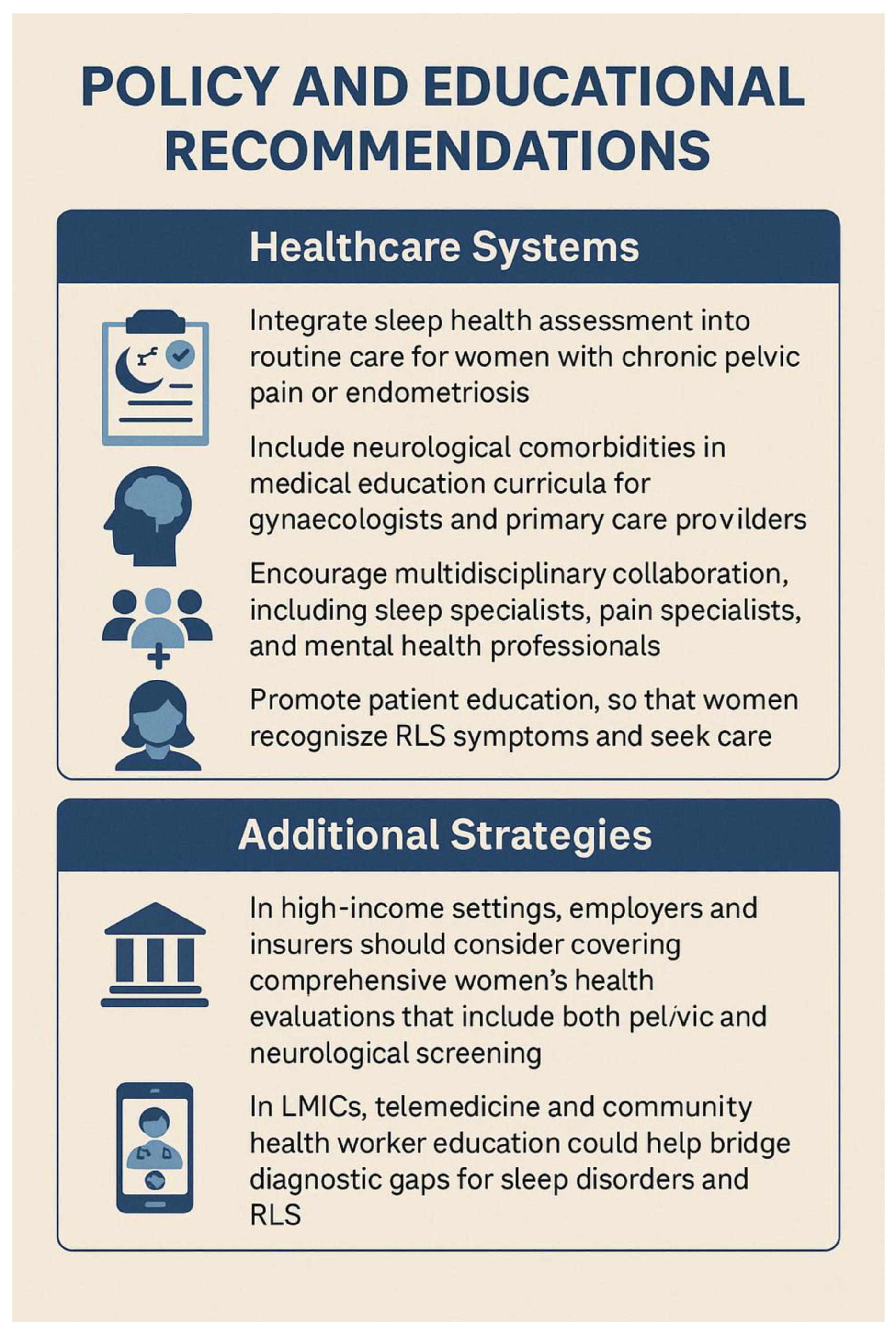

| Policy Recommendation | Key Actions |

| Integrate Neuropsychological Assessment into Women’s Health Services | Routine screening for cognitive symptoms, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances; use validated tools in consultations (70) |

| Promote Interdisciplinary and Life-Course Approaches | Develop interdisciplinary care pathways; ensure life-course continuity of care tailored to each stage. |

| Expand Research on Neuro-Gynaecological Conditions | Fund research on brain imaging, neuroendocrinology, and cognition in women’s health; close gender gaps in clinical trials |

| Address Health Inequities and Social Determinants | Address diagnostic delays via community outreach; invest in culturally sensitive care and accessible health communication (26) |

| Improve Menstrual and Menopause Literacy | Implement menstrual education in schools; standardise menopause care in healthcare systems and workplaces |

| Embed Sleep and Pain Management into Reproductive Health | Screen and manage sleep disorders and pain in reproductive health; train providers in sleep–hormone–pain links (71) |

| Develop Global Health Frameworks with Neurological Dimensions | Incorporate neurocognitive wellbeing into global women’s health policies; support LMIC capacity-building (72) |

| Promote Menopause- and Pain-Friendly Workplaces | Encourage workplace accommodations for menopausal symptoms and chronic pain; promote global adaptation of UK models. |

| Mandate Medical Education Reform | Integrate neuro-gynaecology and menstrual health into medical curricula; tackle gender bias in clinical training (73). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).