Introduction

Homelessness among women is a complex phenomenon shaped by cultural norms and notions of deviance, with profound implications for women’s health. Since the 1980s, understandings of homelessness have shifted from viewing it primarily as an individual pathology or moral failing as Gowan (2010) termed “‘sin-talk’, the individual pathology of homelessness as deviance” to more nuanced perspectives emphasizing illness and structural factors (“‘sick-talk’” and “‘system-talk’”) [

1]. Feminist scholars have highlighted that women’s homelessness fundamentally challenges culturally expected gender roles [

1]. In patriarchal societies, women are traditionally expected to be caregivers, wives, and mothers anchored within a household; a lone woman without a home is seen as anomalous and deviant [

1]. This critical essay examines how such cultural constructions of “normative” female behaviour versus “deviance” shape the experiences of homeless women and their health outcomes. Spanning 1980 to 2025 and drawing on examples from the United Kingdom (UK), Europe, South America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania, the analysis is grounded in feminist theory, intersectionality, and medical anthropology. It explores how gendered norms and definitions of deviance influence women’s pathways into homelessness, the stigma and violence they face, and the impacts on their physical, mental, and reproductive health. Relevant peer-reviewed studies, government and non-government reports, and international agency publications are cited to provide a robust, comparative perspective on this issue.

Methods

Design and Rationale

We conducted an integrative, critical review informed by feminist theory, intersectionality, and medical anthropology to examine how cultural norms and notions of deviance shape women’s homelessness and health. This design enabled synthesis across empirical studies, policy documents, and grey literature spanning the UK/Europe, South America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania between January 1st 1980–January 1st 2025.

Sources and Search Strategy

We used PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct using keywords and combining concepts of women OR female, homelessness/rough sleeping/hidden homelessness, stigma/deviance, violence, and health outcomes (physical, mental, reproductive). In addition we used government and non-governmental organisation (NGO) reports. All material included were published in English that were available as full texts.

Eligibility and Screening

All reports that focused on women’s homelessness or closely allied forms such as hidden homelessness, street homelessness, statutory/temporary accommodation; explicit analysis of cultural norms, deviance, stigma, violence, or gendered pathways; and/or health outcomes (clinical, surgical, patient-reported, societal, environmental). We included mixed-methods and qualitative studies, policy reports, and official statistics. Opinion pieces lacking analytic content, and sources without sufficient methodological description as well as those published in non-English were excluded.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We extracted study characteristics (country/region, population, design), cultural/structural determinants (patriarchy, stigma, criminalisation, violence), and health outcomes (physical, mental, reproductive). We used constant-comparison and critical interpretive synthesis to integrate empirical and policy evidence, organising themes around (i) cultural norms and deviance, (ii) stigma/violence, and (iii) multi-domain health outcomes, with regional and temporal contrasts (1980s vs. contemporary).

Figures were constructed from the curated sources:

Figure 1 (conceptual pathways model) and regional trend panels (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) using the most authoritative, clearly defined national series available; sources and non-comparability notes accompany each figure.

Ethics

All data were publicly available; no human participants were directly involved.

Theoretical Framework: Feminist, Intersectional and Anthropological Lenses

Feminist Theory and Patriarchy

A feminist perspective is essential to understanding women’s homelessness. Patriarchal cultural, legal and religious norms across many societies have historically confined women to domestic roles as dutiful wives, mothers, or carers [

2]. When women “exist outside the father/male partner controlled ‘home’” they defy patriarchal expectations and are often perceived as experiencing an “extreme and rare” condition [

1]. Feminist scholars argue that responses to women’s homelessness are filtered through these gendered expectations, for instance, a homeless woman might be judged for failing to maintain the role of caregiver or “keeper of the home” [

1]. Early feminist research in the 1980s and 1990s began drawing attention to women’s homelessness as distinct from men’s, noting that it had been largely overlooked or treated as a subset of a male problem [

1]. By the 2000s, feminist analyses underscored how women’s routes into homelessness often involve gender-based violence (such as domestic abuse) and economic inequalities rooted in sexism [

3,

4] .

The concept of the “feminisation of poverty” became pertinent: women disproportionately experience poverty due to lower wages, precarious employment, and caregiving burdens, putting them at greater risk of homelessness [

2,

5]. Feminist theory also critiques earlier explanations that portrayed homeless women as passive victims of patriarchy; instead, it emphasizes women’s agency and the need to account for how social structures constrain or enable their choices [

1].

Intersectionality

Intersectional theory, originating from Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work in 1989, provides a vital framework for analysing homeless women’s experiences. It posits that multiple aspects of identity and power such as gender, race, ethnicity, class, age, (dis)ability and sexuality intersect to shape one’s social marginalisation. Homeless women often belong to several marginalised groups simultaneously, compounding their vulnerabilities [

2]. Crucially, “health- and social inequities that women experiencing homelessness face cannot be understood” through a single-axis lens; intersectionality reveals how factors like gender, poverty, ethnicity, disability or sexual orientation interweave in these women’s lives [

2]. For example, Indigenous, Black and minority ethnic women are frequently over-represented among homeless populations in various countries, reflecting colonial and racial injustices layered atop gender oppression.

In Australia, Aboriginal women face especially high rates of homelessness: by 2021, women comprised 44% of the homeless population, and over half of these women were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander [

4]. This stark statistic illustrates how race, indigeneity and gender intersect under economic hardship and housing crises. Likewise, age intersects with gender: older women (e.g. those over 55) represent a fast-growing segment of homeless individuals in many regions (37.8% of homeless women in Australia in 2021 were 55+ [

4], often due to widowhood, insufficient pensions, or divorce in societies where older women have little financial security. Intersectionality also draws attention to LGBTQ+ women (including trans women) and migrant women experiencing homelessness, who may face additional stigma or legal barriers. A recent study in Buenos Aires found that homeless women attributed the discrimination and unfair treatment they endured to “the fact of being homeless, being women (cis or trans), and being poor” [

6] – a clear articulation of intersecting disadvantages. By applying an intersectional lens, we can see that a homeless woman’s experiences and health are not solely about her gender or housing status, but about a confluence of many social determinants.

Medical Anthropology and Social Determinants

A medical anthropological approach situates homeless women’s health in the broader cultural and socio-economic context, rather than viewing health problems in isolation. It recognises homelessness as not just a loss of physical shelter but as social exclusion that produces “huge health inequalities” [

2]. The concept of

structural violence is useful here: coined by Johan Galtung and applied by anthropologists like Paul Farmer, structural violence refers to institutional and systemic harm done to marginalized people by perpetuating inequality and limiting life chances. In the case of homeless women, structural violence manifests as gender-biased housing systems, inadequate welfare support, and punitive laws that together trap women in a cycle of poverty, trauma and ill-health. A critical study in Canada using feminist theory found that homeless mothers’ trajectories are shaped by structural violence, identifying “structural-level factors” such as

gendered pathways into homelessness, systems of support that create structural barriers, and disjointed services that exacerbate trauma [

6]. In other words, the policies and social services meant to help can fail women through bureaucratic hurdles or insensitivity to gendered needs, compounding their suffering. Medical anthropology also emphasizes

embodiment: how social suffering (like stigma or abuse) literally gets “under the skin” to impact the body and mind. Homeless women’s high rates of trauma-related disorders, chronic illness, and even shortened lifespans are thus viewed as embodiments of the cumulative stressors and dangers they face in society [

3,

4]. This perspective compels us to see health and illness among homeless women not as random misfortunes or personal failings, but as outcomes deeply rooted in cultural definitions (e.g. who is “deserving” of care or housing) and power structures.

Cultural Norms, Deviance, and the Stigma of Women’s Homelessness

Across diverse cultural contexts, a woman without a home often finds herself cast as a social deviant as someone who has transgressed the unwritten rules of “proper” womanhood. The normative ideal in many societies is that a woman should be anchored in a household as a dutiful daughter, a wife/partner, or a mother caring for children. These roles are romanticized as the feminine domain. Thus, when a woman is “out of place” visible on the streets, unmoored from family – she is frequently met with public disapproval or bewilderment. Society, in effect, “does not expect women to be homeless, because women are viewed as being the core of family structures, the core of what society understands as ‘home’” [

1]. This cultural mindset has been observed from Europe to Asia: for instance, in the UK, lone homeless women have long been treated as an atypical subset of the homeless population, with assumptions that most women will either be protected by family networks or absorbed into social services especially if they have children [

1]. In South Asian contexts, strongly patriarchal norms similarly dictate that a “respectable” woman lives under male protection; a woman on her own in public is often viewed with suspicion. Research from Pakistan notes how patriarchy “reinforces male superiority and female subordination” and confines women to nurturing roles [

2], meaning that women who flee abusive homes or otherwise end up in shelters are seen as violating cultural and even “moral” codes. The consequence is that homeless women may be shunned, harassed, or labelled as morally loose for example, they might be presumed to be sex workers or to have drug addictions, regardless of the actual reasons for their homelessness.

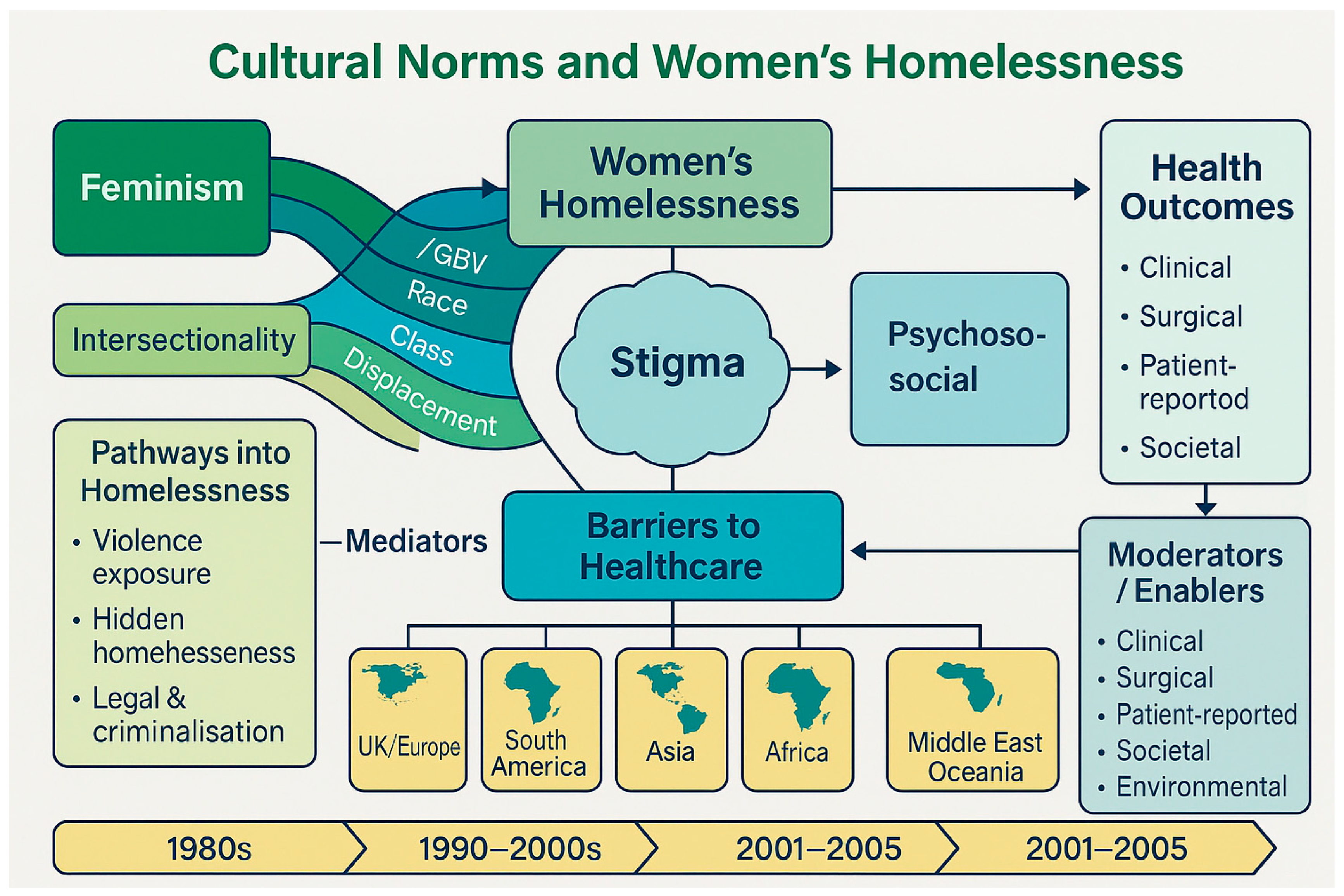

This figure demonstrates how cultural norms, intersectionality, and structural inequalities interact to influence pathways into homelessness for women. Stigma and barriers to healthcare mediate the relationship between these upstream factors and diverse health outcomes. The model highlights the need for context-specific, trauma-informed interventions and policy reforms to reduce health inequities among homeless women globally.

Stigma and “Deviant” Labels

Homeless women frequently face stigma that paints them as deviants unworthy of empathy. They carry the compounded stigma of both homelessness often associated with dirtiness, criminality or failure and of violating gender norms. In many cultures, homelessness is heavily stigmatized for anyone as a form of social failure – but women report distinct forms of stigma. A qualitative study in Ethiopia found that one reason policymakers paid so little attention to homeless women was a lack of consensus on defining their plight implicitly, homeless women remained invisible, in part because acknowledging them challenges conventional norms and statistics often fail to count them [

7]. In Western countries too, homeless women have historically been less visible than men; many hide their situation due to shame or fear. Women will engage in ”hidden homelessness”, for instance by couch-surfing or staying in temporary unsafe arrangements, precisely to avoid the public stigma and dangers of street homelessness [

3]. In Australia, it is noted that women often

do not disclose their homelessness to authorities or health providers, fearing judgement or child removal the term “no fixed address” on forms can mask their situation [

4]. Such under-reporting stems from stigma and the very real possibility that a homeless mother will be deemed an unfit mother by child protection agencies [

4]. This creates a vicious cycle: stigma drives women to hide, which in turn renders them less visible in data and policy, reinforcing the false norm that women are rarely homeless.

Culturally specific labels also play a role. In Latin America, machista attitudes may brand homeless women as “

mujeres de la calle” (street women) with connotations of prostitution or moral corruption. In parts of Africa, extreme cases show how cultural beliefs can directly pathologize and endanger homeless or isolated women: elderly destitute women, especially widows without family protection, are sometimes accused of witchcraft, a heinous label that has led to violent persecution [

8]. Accused “witches” in countries like Kenya and Ghana have been beaten, banished from communities, or even killed, in a grotesque expression of how deviance from social norms (being an older woman without a traditional family role) is met with brutality [

8]. While witchcraft accusations are an extreme form of stigmatization, more common across cultures is the notion that a woman on the streets must have deviated from acceptable behaviour where “she” is often assumed to be mentally ill, addicted, or promiscuous. In the UK, the media historically referred to solitary homeless women as “bag ladies,” a term dripping with pity and implicit blame, suggesting a fall from normative grace. By the 1990s and 2000s, advocacy began reframing homeless women as

victims of circumstance and oppression rather than deviants. Nonetheless, remnants of the deviance narrative persist in public attitudes and even in how services are structured with many geared towards male patterns of homelessness.

Survival Strategies and ‘Deviant’ Behaviour

Importantly, homeless women may engage in activities deemed deviant or transgressive as

survival strategies, which then reinforces societal stigma. With few options to secure income or safety, some resort to sex work, panhandling, petty theft, or substance use. These behaviours should be understood in context – as responses to extreme marginalization yet society often views them through a punitive lens. A UK survey found 28% of homeless women had formed an unwanted sexual partnership just to get a roof over their head, and 20% had engaged in sex work to afford accommodation [

3]. This phenomenon known as “survival sex” illustrates the bind homeless women are in: exchanging sex is one of the only tools available to avoid sleeping rough, but it simultaneously marks them as ‘deviant’ in the eyes of the public (and the law). The same survey noted that such involvement in sex work can lead to entanglement with the criminal justice system, further entrenching homelessness and social exclusion [

3]. Likewise, homeless women often use drugs or alcohol as a coping mechanism to numb trauma or stay awake through dangerous nights, but this substance use can be interpreted by society as a personal failing or moral flaw. In London, homelessness services have reported a sharp rise in drug and alcohol problems among women sleeping rough, a 65% increase since 2014, far outpacing the increase among men in most cases

these problems developed before the woman first became homeless, as a result of traumatic life experiences [

3]. Such findings challenge the stereotype that women are homeless

because of substance abuse; more often, trauma such as childhood abuse, domestic violence precedes both addiction and homelessness, creating a complex web of “deviant” labels attached to someone who in truth has been severely victimized [

3].

The cultural context of deviance also has a legal dimension. Many jurisdictions criminalize aspects of homelessness loitering, vagrancy, street sleeping, soliciting), and women often get caught in these nets. In some South American cities, homeless women report anticipating harassment or arbitrary detention by police

simply for being homeless. In Argentina, for example, nearly two-thirds of homeless women surveyed felt they could be “insulted or detained without cause” by authorities [

6]. This anticipated discrimination came from being seen as

doubly deviant poor and female in public space. Such criminalization not only adds to mental stress but can lead to incarceration or fines, further harming women’s health and prospects. Anthropologically, one could argue these punitive responses are society’s way of enforcing norms: by punishing the homeless woman, society signals that she has deviated from acceptable behaviour (i.e. not being under male/family supervision) and must be corrected or hidden away.

Violence, Trauma and Social Suffering

A constant across regions is that homeless women are exposed to extraordinarily high levels of violence. When cultural norms fail to contain women within homes, societies paradoxically often respond not with protection but with violence and predation. Homeless women are far more likely than their male counterparts to be victims of sexual and gender-based violence, both before and during homelessness [

9]. Violence is simultaneously a leading cause

and a consequence of women’s homelessness [

3]. For many women, the pathway into homelessness is paved with abuse: domestic violence is cited as the single most common driver of women’s homelessness in numerous countries. In the UK, over half of women sleeping rough have experienced abuse from a partner or family member, and one-third attribute their homelessness directly to fleeing domestic abuse [

3]. Similarly, in Australia, family and domestic violence accounts for 45% of all requests for homelessness assistance [

4]. Women often face an impossible choice; stay in a violent home or risk homelessness a decision shaped by cultural pressures such as stigma against divorce, economic dependence on husbands and lack of social support. Many become homeless

because they bravely left an abuser, only to encounter new dangers on the street.

Once homeless, women’s vulnerability to violence multiplies. The street and shelter environments often mirror and magnify the patriarchal violence women face in private homes. Frontline outreach workers in Brazil poignantly described the

”daily violence experienced by homeless women” as a constant in their narratives [

6]. Women sleeping in public endure sexual assault, beatings, and exploitation with alarming frequency. One Brazilian study reported homeless women being raped by strangers or even assaulted by security personnel who should be protecting citizens [

6]. Women without shelter may attach themselves to male partners for protection a pragmatic adaptation to deter predators yet even those partnerships can turn violent. According to outreach professionals, many homeless women “get a companion and a dog to stay safe and even then it ends up happening” that they are abused [

6]. This underscores the grim reality: no makeshift strategy can fully shield a lone woman in the absence of a safe home. Moreover, violence can come from unexpected quarters. In the Brazilian context, women sleeping rough avoided areas with established sex workers out of fear that turf conflicts would lead to physical attacks [

6]. Here we see how desperation can breed conflict even

among marginalized women, illustrating what anthropologists call “structural violence” where oppressed groups are pitted against each other by circumstance.

The traumatic effects of such violence are profound. Homeless women often suffer from complex trauma repeated interpersonal trauma that can lead to PTSD, depression, anxiety, and substance dependence. Trauma becomes “cumulative and compounded” over time [

4]. A woman who was abused in childhood, then battered by a partner, and later raped on the streets carries layer upon layer of unhealed trauma. Medical anthropology emphasizes that this trauma is not merely individual pathology but

social suffering, produced by an interplay of personal abuse and societal neglect. Homeless women frequently exhibit hyper-vigilant or aggressive behaviours as adaptive responses to danger. Outreach workers note that women learn to “change their attitudes” on the streets, sometimes pre-emptively attacking or lashing out as a strategy for self-defence [

6]. What might be labelled “deviant” aggression is, in context, an embodied trauma response. Unfortunately, these defensive behaviours born of violence can create barriers to care, as women may struggle to trust service providers or may appear hostile when in fact they are fearful [

6]. Culturally sensitive, trauma-informed approaches are needed to break through this defensive shell and address the underlying wounds.

An important aspect of violence against homeless women is sexual and reproductive coercion. The threat of rape is a shadow that looms over every homeless woman’s night. Studies in the United States have found staggeringly high rates of sexual assault: one survey in Los Angeles in the 1990s found 13% of homeless women had been raped in the past year alone [

10]. Similar or higher rates have been reported in other cities and countries. Even short of rape, the constant harassment lewd solicitations, groping, the inability to find secure and private spaces constitutes a form of gendered violence. In Europe, migrant or asylum-seeking women who end up homeless (often because they have no recourse to public funds) are particularly vulnerable to traffickers and exploiters, essentially being forced into sex for survival [

3]. The

consequence of such pervasive violence is not only immediate physical harm but long-term mental health damage and an undermining of these women’s sexual and reproductive autonomy. Many homeless women describe feeling that their bodies are not their own, they must be “on alert” or at the mercy of others, a direct assault on their dignity and health.

Impacts on Physical Health

Homelessness is catastrophically damaging to women’s physical health. Deprivation of shelter, proper nutrition, sanitation, and safety translates into a host of acute and chronic health problems. In general, people experiencing homelessness suffer far worse health outcomes and markedly higher mortality than the general population [

2]. For women, these health disparities are often exacerbated by the violence and reproductive health challenges discussed above.

General Health and Chronic Illness

Homeless women face high rates of communicable diseases (such as respiratory infections, tuberculosis, HIV), exposure-related conditions (frostbite, heat stroke, foot problems), and chronic illnesses (like hypertension, diabetes) that become poorly managed [

11]. Living without stable housing means lacking refrigeration for medications, regular meals, or a clean environment to recover from illness. Studies have found that homeless women frequently have multiple health issues simultaneously a U.S. study noted prevalent “multimorbidity” among homeless individuals regardless of sex [

4]. However, women may suffer particular burdens such as higher rates of anaemia, complications from poor nutrition, and musculoskeletal problems from carrying belongings or children while on the move. In the UK, recent research by Groundswell found 74% of homeless women had at least one current physical health problem [

3] an astonishingly high prevalence. These ranged from chronic pain and asthma to acute conditions like wounds. Furthermore, the average age of death for a homeless woman in England is just 43 years, nearly 40 years younger than women in the general population [

3]. This shocking statistic encapsulates the cumulative toll of rough sleeping, stress, and inadequate healthcare on women’s bodies. Similarly, in Australia it’s observed that unsheltered homeless women have a

much higher risk of premature mortality than even homeless men, despite men being the majority of rough sleepers [

12]. One reason is that women’s exposure to violence (homicide, fatal assault) and the physiological strain of repeated pregnancies or sexual trauma can drive mortality rates up.

Injuries and Disability

Many homeless women carry long-term physical scars or disabilities. Assaults cause fractures, lacerations, dental trauma, and head injuries. Survivors of domestic violence may have old untreated injuries that worsen over time. Without rest and proper treatment, a simple injury can become a disabling condition. For example, a broken bone that doesn’t heal correctly can limit mobility; a head injury can lead to seizures or cognitive impairment [

13]. Homeless women also often suffer from untreated dental problems and vision/hearing issues, which though not unique to women, can affect their nutrition and safety such as poor vision makes a woman more vulnerable on the streets at night. The cumulative physical trauma can make daily survival even harder, contributing to a cycle where poor health hinders a woman’s ability to seek help or work, prolonging her homelessness.

Sexual and Reproductive Health

A woman’s reproductive system and sexual health are greatly impacted by homelessness, and these issues deserve special attention discussed more fully in the next section. Briefly, high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been documented among homeless women due to sexual violence and lack of access to protection [

14]. For instance, outreach clinics in Brazil regularly encounter homeless women with untreated HIV, syphilis, and other STIs, some of which are detected only when a woman becomes pregnant [

6]. Homeless women also struggle with menstrual health without access to sanitary products or private facilities, menstruation can lead to infections or humiliation. Conditions like urinary tract infections and pelvic inflammatory disease may go untreated and progress.

Nutrition and Maternal Health

Malnutrition and food insecurity are daily challenges. Women, especially mothers, might prioritize any available food for their children or others, going hungry themselves. Over time, insufficient nutrition weakens the immune system and exacerbates conditions like anaemia. Pregnant homeless women are a particularly high-risk group physically. Prenatal malnutrition and stress contribute to low birth weight and complications. Many homeless women have little to no prenatal care – one study described the difficulty of carrying out and monitoring prenatal care for women “pregnant on the streets,” noting that many expectant mothers are not seen until they present in labour [

6]. The result is often unmanaged chronic conditions such as gestational diabetes or hypertension and higher rates of miscarriage, stillbirth, or maternal morbidity. Accounts from Brazil’s Street Outreach teams illustrate stark scenarios where homeless pregnant women with untreated syphilis unable to complete the course of penicillin because they disappear or avoid hospitals due to fear (some were “fugitives from the police” and could not give their real names) [

6]. Consequently, preventable conditions like congenital syphilis continue to harm babies. After giving birth, many homeless women face postpartum recovery without rest or sanitation there are reports of women returning to the streets with infected caesarean section wounds and severe bleeding because they had no follow-up care [

6]. It is hard to imagine a scenario more dangerous to a woman’s health than having major surgery (like a C-section) and then sleeping rough immediately afterward.

Barriers to Healthcare

While health needs are immense, homeless women often encounter daunting barriers to accessing healthcare. Structural barriers include lack of insurance or money for transport, bureaucratic requirements such as having an ID or address to register at a clinic), and inflexible appointment systems. Cultural and interpersonal barriers are equally significant: many homeless women do not trust healthcare providers or have had negative experiences of discrimination in clinics [

2]. A history of trauma can make clinical settings triggering. Moreover, when healthcare is delivered in male-dominated or mixed environments such as general homeless drop-in clinic full of men, women may feel unsafe or unseen. Medical anthropologists note that these barriers lead homeless women to under-utilize preventive and primary care, often only seeking help when a condition is advanced or life-threatening [

2,

4]. This contributes to higher emergency room use and hospitalizations, reflecting a system that reacts to crises rather than preventing them. Some innovative programs are trying to bridge this gap: for example,

street medicine teams in Brazil and elsewhere bring healthcare directly to homeless encampments, offering services like wound care, vaccinations, and chronic disease management [

15]. Such efforts, especially when they include female healthcare workers or a focus on women’s health, have shown promise in reaching women who would otherwise go without care. Nonetheless, as of 2025, across much of the world there remains a large unmet need for accessible, gender-sensitive health services for homeless women.

Mental Health and Substance Use

Homeless women’s mental health is deeply affected by their experiences, with high prevalence of psychiatric conditions that both precipitate and result from homelessness. It is well documented that homeless women are more likely to experience mental ill-health than homeless men, and their mental health issues are often more complex [

3]. For example, in England 58% of women sleeping rough report mental health problems (vs 44% of men) [

3], and women with mental illness are at higher risk of chronic or repeated homelessness [

3]. Common mental health diagnoses among homeless women include depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance use disorders. It is critical to note that these conditions often arise in response to the extreme stressors homeless women face, though pre-existing mental illness can also be a factor in women becoming homeless especially in societies where mental health services are inadequate, and families may abandon women with serious mental illness.

Trauma and PTSD

The prevalence of PTSD among women experiencing homelessness is strikingly high due to the pervasive violence and abuse in their lives. Many have enduring flashbacks, nightmares, hyperarousal, and avoidance behaviours linked to past assaults or childhood abuse. A Canadian study on structural violence noted that

experiences of violence, homelessness and trauma are cyclical and interconnected [

6] each one feeding into the other. The cumulative trauma can lead to a state of constant fear and mistrust. Women may become socially withdrawn or conversely, prone to angry outbursts. Both reactions hinder their ability to engage with support systems that might help them. In South America, mental health stigma is also a challenge; homeless women with evident psychological distress are at risk of further marginalization, sometimes dismissed as “crazy” or subjected to police brutality rather than medical care [

6]. Without trauma-informed mental health support, many women self-medicate with drugs or alcohol which can develop into addiction or they simply suffer in silence, which can lead to suicide in some tragic cases.

Depression and Self-Harm

Homeless women frequently report feelings of hopelessness, shame, and isolation classic markers of depression. They experience grief from multiple losses: the loss of home, often the loss of custody of children, loss of partner through violence or separation, and loss of identity or purpose as defined by their former roles. These compounded losses can trigger severe depressive episodes. Studies have found elevated rates of suicidal ideation among homeless women. They are also at risk of self-harm. Medical staff in emergency shelters often encounter women who engage in cutting or other self-injurious behaviour as a coping mechanism for emotional pain. Depression in homeless women is often under-treated: antidepressants or therapy may be out of reach, and the daily grind of survival leaves little space to heal psychologically. Furthermore, many homeless women internalize the stigma and blame – feeling that they have failed as mothers or wives which reinforces low self-worth and hinders recovery from depression.

Substance Use and Dual Diagnosis

While excessive substance use such as drugs and alcohol is sometimes a cause of homelessness, for many women it is largely a

consequence or coping strategy. The extreme stress, trauma, and physical hardships push many women towards using substances to numb pain, stay awake, or find moments of escape. Over time, some develop substance use disorders. This often overlaps with mental illness a dual diagnosis of, say, PTSD and opioid dependence, or depression and alcohol dependence. Homeless women who use substances face a double stigma and are often excluded from shelters or services that have strict abstinence rules, leading them to further marginal environments such as street encampments where overdose and violence risks are high. There is a gendered pattern to substance use as well: homeless women may be introduced to drugs by male partners or exploiters and can become trapped in abusive, drug-fuelled relationships. A London study by St Mungo’s found a sharp increase in women rough sleepers with drug/alcohol problems and noted that in “most cases, drug and alcohol problems develop before a woman first sleeps rough, the product of traumatic experience” [

3]. The substances often serve as both a cause and symptom of mental distress. Medical anthropology points out that in many cultures women who drink or use drugs heavily are seen as especially deviant, violating feminine ideals of purity or self-control, which can lead to additional shame and reluctance to seek help.

Barriers to Mental Healthcare

Homeless women face significant obstacles in accessing mental health care. Many shelters or temporary accommodations lack on-site mental health services. Outpatient clinics may require appointments that are hard to keep when one’s life is chaotic. Furthermore, distrust of institutions due to past trauma or discrimination can make women less likely to engage with formal mental health treatment. This is one area where intersectionality is crucial: for instance, an Indigenous homeless woman might fear or distrust Western mental health services due to historical trauma or culturally insensitive care [

16]. Likewise, immigrant women may face language barriers or culturally inappropriate counselling. Intersectional stigma also plays a role a Black woman with mental illness and homeless may face racial stereotypes when seeking help, or a transgender homeless woman might avoid clinics for fear of transphobia. All these factors contribute to many homeless women not receiving needed psychiatric care or therapy. Encouragingly, there are emerging models of care that integrate mental health with other support: trauma-informed shelters, women-only drop-in centres with counsellors, peer support groups led by formerly homeless women, etc. Evaluations show that women respond well to empathetic, peer-informed approaches that make them feel safe and understood (which is unsurprising given their prior traumas often involve violation of trust). Still, in most parts of the world, mental health services for homeless women remain ad hoc and under-resourced [

7].

Reproductive Health and Motherhood

Women’s homelessness has unique repercussions for reproductive and gynaecological health, which have been under-addressed historically. The ability to control one’s reproduction and to parent children is severely compromised by the state of being homeless, and cultural norms around femininity and motherhood cast a long shadow over these experiences.

Gynaecological Health

Homeless women often suffer from neglected gynaecological issues from untreated infections to lack of cancer screenings. They face many barriers to accessing reproductive healthcare like Pap smears, STI tests, and contraceptive services. Interestingly, outreach programs have found that offering gynaecological care can be an effective “gateway” to reach homeless women [

6]. In Brazil, a

Street Outreach Office initiative reported that many women initially engage with health services through gynaecological consultations, which they seek even when they avoid other kinds of medical help [

6]. This is partly because issues like severe pelvic pain, vaginal infections, or menstrual irregularities become unbearable, and also because women may perceive reproductive health as one area where they deserve care. Such programs often provide cervical cancer screenings, STI testing, and contraception like subdermal contraceptive implants) on the spot [

6]. High rates of STIs including HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis have been detected among homeless women, reflecting both sexual violence and lack of preventive services [

6]. Untreated STIs can lead to infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and in the case of syphilis, can be passed to infants congenitally. Homeless women also face problems like fibroids or endometriosis without relief, and menopause may come early or with exacerbated symptoms in this population [

17]. There is evidence that prolonged stress and malnutrition can disturb menstrual cycles or fertility, adding another layer of unpredictability to their health.

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Homelessness is extremely perilous for pregnant women. Pregnancy in a homeless context often goes hand-in-hand with inadequate prenatal care. As noted in a Brazilian study, outreach workers struggle to even

find and follow up with pregnant women to ensure they get ultrasounds and tests, because these women are highly mobile or hiding [

6]. As a result, conditions like gestational diabetes or hypertensive disorders often remain undiagnosed until a crisis occurs. The risk of preterm birth and low birth weight is high, given the stressful environment and poor nutrition. Labor and delivery for homeless women can also be fraught some women delay going to the hospital for fear of mistreatment or of child protection taking their baby immediately. Health workers recount cases where they had to secure a spot in a maternity ward for a homeless woman and virtually escort her through the process to ensure she wasn’t turned away [

6]. Even when homeless women do give birth in hospitals, the postpartum period is especially difficult. Many are separated from their newborns almost immediately: it is common for child welfare agencies to remove babies born to homeless mothers, on the grounds that the mother cannot provide a safe environment. From a medical standpoint, this might protect the infant’s health, but from the mother’s perspective it is a devastating loss and often a reason she might avoid maternity services in the first place. Homeless mothers who wish to keep their infants face enormous challenges they must secure at least a temporary shelter or transitional housing quickly. The emotional toll of having a child removed can worsen the mother’s mental health and lead to relapse into substance use or deeper despair [

18].

Furthermore, homeless women who have other children frequently carry the trauma of separation. As noted in England, half of single homeless women are mothers, but most do not have their children in their care, with many children taken into foster care or relatives’ care [

3]. These family separations are both a result of homelessness authorities step in when a mother lacks housing and a cause of prolonged homelessness the grief and legal battles can derail a woman’s efforts to recover. Mothers on the streets often stay in abusive situations to avoid losing their children e.g. enduring a violent partner because leaving might mean homelessness and thus child removal [

3]. Those who do lose children may become trapped in a vicious cycle: without stable housing they cannot regain custody, but the trauma of losing custody makes it harder to achieve stability. This scenario is common across different regions. In the UK, for example, women have reported that after fleeing domestic violence, they were not prioritized for housing because their children were taken into foster care; ironically, they could only get their children back if they found housing, an almost impossible task without support leading to what advocates call a “vicious cycle” of women remaining homeless longer than necessary [

3].

Survival Sex and Reproductive Control

The practice of survival sex and sexual exploitation has obvious reproductive health implications: unwanted pregnancies are common. Homeless women may have limited ability to negotiate condom use, either in transactional sex or even with a steady partner who may control them. As a result, homeless women experience higher rates of unplanned pregnancies and often multiple pregnancies in quick succession. Some pregnancies end in miscarriage, others in unsafe abortion where abortion is illegal or inaccessible, women might resort to dangerous methods. Those who carry to term face the challenges described above. Access to contraception is spotty; some shelters or clinics provide free contraceptives, but a woman sleeping rough might have no easy, private way to obtain pills or injections regularly [

19]. Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) like implants or intrauterine devices are increasingly recommended for homeless women to give them a measure of control – indeed, the Street Outreach in Brazil actively offered LARC insertion to women on the streets [

6]. However, even this must be done carefully and with consent, given historical abuses (there is a troubled history of coercive contraception targeting poor or minority women). A feminist health perspective insists that homeless women be given full information and choice regarding reproductive health services, to empower them rather than treating them as passive recipients.

Menstrual Hygiene

A less researched but crucial aspect of women’s health is menstrual hygiene management. Homeless women often lack access to sanitary pads or tampons, clean water, and private facilities. This can lead to them using unhygienic substitutes old rags, newspapers or bleeding freely, causing skin infections and humiliation. Culturally, menstruation can carry taboos; in some societies, women are expected to isolate or be extra clean during periods an impossible requirement for a homeless woman. Thus, menstruation becomes yet another source of stigma and discomfort. Recently, some NGOs have started to distribute menstrual hygiene products to homeless women, recognizing it as a dignity and health issue. Additionally, the rise of “period poverty” activism especially in the 2010s has shed light on how women in extreme poverty, including homelessness, struggle during their menstrual cycles. For a homeless woman, the arrival of her period may mean a choice between buying food or buying pads, a choice no one should have to make [

20].

Regional and Comparative Perspectives

While the overarching themes of gendered norms and health impacts resonate globally, there are important regional variations in women’s homelessness between the UK, Europe, South America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania, as well as changes from 1980 to the present. These differences influence how homelessness is experienced and addressed.

United Kingdom and Europe

In the UK and much of Europe, the welfare state and social services framework have somewhat cushioned women from absolute homelessness, particularly women with children. Since the 1980s, laws in the UK have given some priority to women especially pregnant women or those with dependents in housing assistance, which stems from an understanding that these groups are “vulnerable” and a cultural notion of protecting motherhood. Consequently, a large proportion of homeless women in Britain are counted among the

statutorily homeless (in temporary accommodation or awaiting housing) rather than rough sleepers. As noted earlier, about 56% of statutory homeless households in England are headed by women mostly lone mothers) [

3], whereas only ~14% of rough sleepers are women [

3]. However, these figures can mislead: they “do not give a full picture” because many women avoid rough sleeping by finding informal and often dangerous arrangements [

3]. European researchers observe that women’s homelessness is often

hidden by design, a direct response to fear of violence [

3]. In countries like Sweden, it’s been pointed out that homelessness research and policy historically treated it as a male phenomenon, resulting in scarce data on women [

2]. Only in recent years have European networks such as FEANTSA – the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless, pushed for more gender-responsive approaches. Countries such as France, Spain, and Ireland have also documented rising numbers of homeless women, often linked to austerity measures, migration, and domestic violence [

21]. By 2025, the discourse in Europe acknowledges that while men still make up the bulk of visible homelessness, women’s homelessness requires targeted strategies for example, women-only shelters and safe spaces are expanding in some cities, recognizing that traditional mixed shelters can be unsafe or unwelcoming for women [

3]. The cultural context in Europe predominantly secular, with relatively high gender equality indices) might suggest less overt stigma towards homeless women than in very conservative societies. Yet, homeless women in Europe still report feeling highly stigmatized and afraid of judgement. The normative expectation of women as home-makers is deeply ingrained even in Europe’s modern societies [

1]. A homeless woman in, say, Italy or Poland may face family shame or be seen as bringing dishonour, which might not be formally religious but is tied to community values about women’s roles.

South America

In South America, strong family networks and marianismo the ideal of female self-sacrifice for family characterise cultural norms [

22]. Women often endure hardship to keep the family unit intact. This can both prevent and prolong homelessness: some women will tolerate extreme abuse or impoverishment at home rather than leave thus avoiding homelessness, while those who do become homeless might still try to keep children with relatives to maintain maternal identity. South American countries have significant homeless populations especially in major cities such as street dwellers in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires. Women on the streets there often congregate in certain areas and sometimes form small communities for mutual aid. However, they also encounter macho aggression in public. For example, homeless women in Brazil, as discussed, face violence from multiple fronts, partners, police, other street inhabitants [

6]. Culturally, a homeless woman may be viewed with a mix of pity and scorn; charities, often church-based, provide soup kitchens or refuges, but state interventions have been limited. The period from 1980 to 2025 in much of South America saw economic upheavals (debt crises, structural adjustment, hyperinflation in the 1980s, neoliberal reforms in the 1990s) that worsened poverty. Women, as part of the informal economy in large numbers, were hit hard, leading to what Latin American scholars call the

feminization of poverty. This has inevitably led to more women unable to afford housing. Countries like Brazil have some progressive health policies (the SUS public health system) which, at least on paper, guarantee healthcare to homeless individuals; indeed, Brazil pioneered street medicine teams (Consultórios na Rua) that include focus on women’s sexual health [

6]. Still, these services are not uniformly available. Argentina’s recent study on homeless women noted the glaring lack of data and policy for women’s homelessness [

7] – there was “no consensus regarding the definition” and little political priority given to it, despite evidence of severe health impacts on women [

7]. This indicates that cultural and political recognition of homeless women’s issues in parts of South America is still nascent. Encouragingly, grassroots feminist movements in the region such as Ni Una Menos, which protests violence against women increasingly highlight how domestic violence and homelessness are connected, potentially spurring more gender-aware homeless services in the future.

Asia

Asia contains vast cultural diversity, but many Asian societies share strong patriarchal family systems. In South Asia, women’s homelessness is often tied to widowhood or marital breakdown. A woman without a husband can be extremely vulnerable if her in-laws or natal family do not support her widows might be ostracised as in parts of India, where widows historically were marginalized and even congregated in cities like Vrindavan [

23]. Some end up homeless or in shelters/ashrams for destitute women. Dowry practices and domestic violence also contribute; women who are “discarded” by husbands or in-laws may literally have nowhere to go [

24]. The 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of some NGOs focusing on “street women” in cities like Mumbai or Dhaka, but large-scale data is limited. In East and Southeast Asia, rapid urbanization created new homelessness challenges. Countries like Japan and South Korea historically had very low homelessness rates with cultural factors discouraging public presence of women in need, but economic recessions saw older men dominate the homeless demographics, with few women on the streets [

25]. Those women who are homeless often resort to “net café refuges” as in Japan, where women might stay overnight in cheap internet cafes or other hidden forms, reflecting the shame associated. In China, internal migration and lack of hukou household registration) for migrants has led to some migrant women living in slums or as unofficial homeless, though the issue is not well-documented. One case worth noting: in parts of South Asia and Africa, there are instances of accusations of witchcraft leading to older women being cast out (as mentioned earlier with Kenya. In India and Nepal, there have likewise been cases of widows or single older women accused of witchcraft and expelled from villages. Thus, while the specifics differ, the underlying theme is that women who lack male protection or defy expected roles like the docile wife or selfless mother often find themselves socially exiled and extremely vulnerable.

From a health perspective, Asian homeless women often inhabit slums or informal settlements rather than street homelessness per se. For example, large numbers of women live in the urban slums of India or the Philippines; while not “homeless” by certain definitions they share many conditions of homelessness: inadequate shelter, no secure tenure, and poor health outcomes. The WHO South-East Asia region has acknowledged that women in informal settlements have high maternal and infant mortality, and lack access to sanitation, which is analogous to the plight of homeless women. There is also a growing issue of refugee or conflict-driven homelessness of women such as displaced Rohingya women in camps in Bangladesh, or war-displaced women in the Middle East these scenarios blur into disaster/humanitarian contexts but similarly involve women outside their normal social structures, facing health crises.

Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, homelessness often takes the form of informal housing also known as

shanty towns or refugee camps rather than rough sleeping in city centers, though street homelessness exists too for instance, street families in Nairobi or Johannesburg. The extended family system in many African cultures has traditionally absorbed widows, single mothers, or struggling kin, but this has been under strain due to urbanization, HIV/AIDS which created many orphans and widows simultaneously), and economic hardship. Homeless women in African cities might be domestic violence survivors who have no formal refuge; while some countries like South Africa have shelters, they are few relative to need. Research in Johannesburg in the 1990s already highlighted that homeless street women had dire health profiles [

26], and more recent South African work has drawn attention to how family violence and gender inequalities drive women into homelessness [

27]. For example, family violence is the leading cause of homelessness for Indigenous women in South Africa (who are six times more likely than non-indigenous women to experience domestic violence) [

27], echoing patterns in other regions. A qualitative study in Ethiopia (2023) revealed that the lack of policy focus on homeless women meant virtually non-existent targeted health or social services for them [

7]. In many African countries, homeless women (especially those without children with them) are a highly marginalized and almost invisible population, often conflated with beggars or sex workers in public perception. Their health needs be it for HIV treatment, prenatal care, or trauma support – are largely unmet unless they encounter charitable clinics or missions [

28].

One distinct challenge in Africa is the intersection of homelessness with the HIV epidemic. Women who are homeless or in unstable housing have higher HIV prevalence, and conversely, women living with HIV who lack family support can end up homeless for instance, if their illness leads to stigma or inability to work. This creates a vicious cycle of ill health and homelessness. Some countries have started to integrate housing with HIV programs for women, recognizing stable housing as key to adherence to medication.

Oceania (Australia and New Zealand)

In Oceania, particularly Australia, women’s homelessness has gained considerable attention in the past decade. The context is somewhat similar to the UK in that welfare support exists, but changing economic conditions like a housing affordability crisis have led to more women falling through the cracks. Notably, Australia has seen a surge in older women becoming homeless due to a combination of factors: gender pay gaps and unpaid caregiving leave many with little retirement savings, and if they experience a late-life divorce or rent increase, they may be unable to secure housing. These “new” homeless sometimes termed the “hidden homeless” because they often sleep in cars or couch-surf have challenged the stereotype that homelessness only happens to mentally ill or addicted individuals [

29]. Australian data from 2021 show women are about 44% of the homeless population, with Indigenous women and older women disproportionately affected [

4]. Culturally, this has forced a reckoning: seeing respectable middle-aged women turning to homeless services has reduced some stigma and prompted calls for policy action like more public housing and rent support for older single women. Additionally, Australia and New Zealand have significant Indigenous populations for whom homelessness cannot be separated from the legacy of colonization and dispossession. Indigenous women often have extended family obligations and high rates of domestic violence victimization, contributing to cycles of housing instability. Indigenous conceptions of “home” and “homelessness” may also differ with some preferring kin-based crowding over going to formal shelters). Efforts are under way to create culturally appropriate support for example, incorporating Indigenous elders in designing women’s shelters or ensuring that traumatised Aboriginal women are not further alienated by mainstream services [

30].

Over the 1980–2025 period, one positive trend in Oceania and globally has been the development of the Housing First approach, which asserts that providing permanent housing is a prerequisite to effectively address other issues like health or employment. Some programs such as “Homes for Women” pilot in Brazil [

31], or women-focused Housing First in Canada and Australia) specifically target homeless women with histories of trauma, offering them housing coupled with support. Early evidence suggests women benefit greatly from Housing First, as it directly counters the instability that exacerbates their health problems. It also tacitly challenges the notion that they must

earn housing by fixing other issues; instead it treats housing as a human right and foundation. This aligns with international human rights frameworks: the UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing has emphasized that women’s right to housing is central to gender equality [

27], and that states should eliminate discrimination that leaves women homeless. Unfortunately, many countries are far from this ideal, but the recognition is growing.

Changes over Time (1980s vs. Today)

In the 1980s, women’s homelessness was a peripheral topic in both research and policy. Homeless populations in Western countries exploded in the 1980s due to economic policies and deinstitutionalization of psychiatric care, but the focus was largely on men, who were more visible on skid rows and in shelters. Women were often only discussed in context of homeless families usually as mothers accompanied by children. Feminist scholars in the late 1980s such as Watson, Casey, and others began pushing “gender back on the agenda”shura.shu.ac.uk, arguing that women’s experiences including hidden homelessness and the role of domestic abuse must be differentiated [

32]. Through the 1990s, more data emerged, and by the 2000s, intersectional analyses examining how race and class compound female homelessness became more common [

5]. The concept of intersectional structural inequalities fuelling the “feminization of homelessness” gained traction [

5]. In policy, the 2000s saw some gender-specific interventions, for example, in the UK, specialised services for women rough sleepers were developed, and domestic violence refuges while not always labelled as homelessness services effectively served as a homeless prevention for abused women. By the 2010s and 2020s, there is a broader acknowledgment of homeless women’s unique needs, yet huge gaps remain. The #MeToo movement and wider attention to violence against women have helped highlight that a significant subset of homeless women are survivors of gender-based violence, prompting closer ties between homelessness services and violence prevention services. The COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) further cast light on homelessness as a public health issue and showed how crises disproportionately affect vulnerable women [

33]. UN policy briefs noted that “the impacts of COVID-19 are exacerbated for women and girls simply by virtue of their sex” [

2] for homeless women this was acutely true, as lockdowns meant closed services and women having to survive “adding insult to injury” with even fewer interactions and support [

2]. Some cities put homeless people into hotels temporarily, and notably, many women who had been sleeping rough or in unsafe situations benefited from this emergency housing, proving that political will can swiftly make housing available. The challenge moving forward is to maintain and expand such progress in more normal times.

Discussion

The experiences of homeless women from 1980 to 2025 reveal a tragic continuity of gendered disadvantage, yet also a growing understanding that homelessness is not gender-neutral. Culturally ingrained norms about women’s “proper” place in the home, under male protection, fulfilling selfless roles have rendered the homeless woman a figure of deviance, often ignored at best or criminalized and victimized at worst. This critical perspective, grounded in feminist theory, intersectionality, and medical anthropology, shows that homeless women’s lives are shaped by the collision of patriarchal norms which marginalize women who don’t conform) and structural forces (like poverty, violence, and inadequate social safety nets). These forces manifest in severe health consequences: physical illnesses and injuries, mental trauma, and compromised reproductive health that collectively amount to a violation of women’s rights to health and housing.

Yet, over the past decades there has been a gradual shift in both narrative and practice. What was once viewed through a moralistic or individualistic lens “deviant women making bad choices” is increasingly recognized as a systemic issue of gender inequality and social exclusion. Intersectional analyses have illuminated how homeless women are often at the nexus of multiple oppressions for example, an older Indigenous woman fleeing abuse faces ageism, racism, and sexism all at once, heightening her risk of homelessness and ill-health. Medical anthropologists and public health experts have reframed women’s homelessness as a public health crisis and a product of structural violence, rather than an aberration. This perspective urges for holistic solutions: not only providing shelter but also addressing the trauma, providing healthcare, and critically, changing the cultural narratives that blame or shun homeless women.

Policy and practice are slowly catching up. International bodies like the UN now speak of housing as a human right for women, and call on governments to ensure equality in access to housing. Some countries have adopted trauma-informed, gender-responsive approaches for instance, women-only accommodation remains scarce only about 11% of homelessness services in England offer women-only spaces, but its expansion is recognised as crucial for safety and rehabilitation. Empowering homeless women through peer involvement in research and planning as done in Sweden’s co-created studies is another promising development, as it validates their voice and needs.

Ultimately, to improve the health and lives of homeless women, we must challenge the very cultural context that deems their existence deviant. This means tackling stigma in communities, ensuring that a woman leaving an abusive home is met with compassion and prompt support rather than suspicion, and educating society that homelessness is a consequence of structural failings economic inequality, insufficient housing, gender violence not personal moral failings. It also means acknowledging homeless women’s resilience and strengths. As feminist researchers have shown, homeless women develop remarkable strategies to survive and to care for others many still strive to be mothers and helpers even when in crisis. A medical anthropological view encourages us to see homeless women as experts in their own lives, holding vital knowledge about what would help them. Interventions rooted in intersectional justice that is, addressing not just gender but the intersecting racial, economic, and social inequities hold the greatest promise for ending the cycle of homelessness among women.

Conclusion

Women’s homelessness sits at the intersection of cultural normativity and deviance, revealing much about how societies value or devalue women outside traditional roles. Its impact on women’s health is severe and multi-faceted, but not intractable. The years 1980–2025 show both the persistence of patriarchy and the power of feminist and intersectional frameworks to reinterpret and respond to this challenge. A critical, culturally informed perspective makes clear that improving homeless women’s health necessitates transforming cultural attitudes and social systems: from expanding housing rights and healthcare access to dismantling the stigma that clings to the “homeless woman” as a cultural archetype. Only by doing so can we hope to ensure that women regardless of their housing status can live with dignity, security, and well-being.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

The PIs and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

GD conceptualised this manuscript and wrote the first draft. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

References

- Bretherton J, Centre for Housing Policy UoY. Women’s Experiences of Homelessness: A Longitudinal Study. [CrossRef]

- Waqar Husain1 Haitham Jahrami6, FI, Muhammad Ahmad Husain1, Achraf Ammar2,3, Khaled Trabelsi4,5 and.

- Greenhalgh, H. Agenda Briefing: Women and girls who are homeless. Agenda, the alliance for women and girls at risk; 2020.

- Villiers LJWaRC. Leave no-one behind: reducing health disparities for women experiencing homelessness in Australia. Medical jouranal of Australia. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ShirleyV.Truong3 HBHR, MelinaR.Singh.

- Nayara Gonçalves Barbosa TMH, Thamíris Martins Michelon , Lise Maria Carvalho Mendes GGdS, Juliana Cristina dos Santos Monteiro , and Flávia Azevedo Gomes-Sponholz Attention to Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health at the Street Outreach Office. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kalkidan Yohannes1, 3*, Mats Målqvist1, Hannah Bradby4, Yemane Berhane5, and Sibylle Herzig van Wees1.

- Helpage international. Older people in Kenya must be protected from witchcraft accusations 2021 [Available from: helpage.orghelpage.org.

- Diane Santa Maria KB, Stacy Drake, Sarah Narendorf, , Anamika Barman-Adhikari, , RP, Hsun-TaHsu, Jama Shelton, Kristin Ferguson, Kimberly Bender,. Gaps in Sexual Assault Health Care Among Homeless Young Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rosa(a) AdS, Brêtas(b) ACP.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Care for Homeless People. Homelessness, Health, and Human Needs: National Academies Press (US); 1988.

- Joy Moses and Jackie Janosko. Demographic Data Project: Gender and Individual Homelessness. National Alliance to end homelessness. 2019.

- Cléa Adas Saliba Garbin APDdGeQ, Tânia Adas Saliba Rovida, Artênio José Isper Garbin,. Occurrence of Traumatic Dental Injury in Cases of Domestic Violence. Scielo Brazil. 2012.

- Nayara Gonçalves Barbosa1 LMCM, Fábio da Costa Carbogim, Angela Maria e Silva,Thaís de Oliveira Gozzo and Flávia Azevedo Gomes-Sponholz,. Sexual assault and vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections among homeless Brazilian women: a cross sectional qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rio de Janeiro (AFP). In Rio wasteland, health teams take medical care to homeless, 2023 [Available from: rfi.fr.

- Catharine Chambers SC, Allison N. Scott, George Tolomiczenko, Donald A. Redelmeier, WL, and Stephen W. Hwang,. Factors Associated with Poor Mental Health Status among Homeless Women with and without Dependent Children. Community Mental Health. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gayathri Delanerolle PP, Sohier Elneil,Vikram Talaulikar, George U Eleje, Rabia Kareem, Ashish Shetty, Lucky Saraswath, *Om Kurmi,Cristina Laguna Benetti-Pinto, Ifran Muhammad, Nirmala Rathnayake, Teck-Hock Toh, Ieera Madan Aggarwal, Jian Qing Shi, Julie Taylor,, Kathleen Riach KP, Ian Litchfield, Helen Felicity Kemp, Paula Briggs, and the MARIE collaborative. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global helath. 2025.

- Giulio BorghiI PC, Sylvaine Devriendt, Maxime Lebeaupin,Maud Poirier, Juan-Diego Poveda. The perceived impact of homelessness on health during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A qualitative study carried out in the metropolitan area of Nantes, France. Plos one. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Karen Trister Grace CNH, Kristin Bevilacqua , Arshdeep Kaur , Janice Miller , Michele R Decker Sexual and Reproductive Health and Reproductive Coercion in Women Victim/Survivors Receiving Housing Support. Journal of family violence. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Elsevier Ltd. Menstrual health: a neglected public health problem. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas. 2022. [CrossRef]

- FEANTSA Youth. A Gendered Approach to Youth Homelessness. 2021.

- Melissa M. Ertl REB, Robin Petering, Hsun-TaHsu, Jama Shelton, Kristin Ferguson, Kimberly Bender,. Longitudinal Associations Between Marianismo Beliefs and Acculturative Stress Among Latina Immigrants During Initial Years in the United States. Couns Psychol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hossain B. Widowhood and its Associated Vulnerabilities in India: A Gendered Perspective. The india forum. 2024.

- Shalu Nigam. Dowry is a serious economic violence: Rethinking Dowry Law in India2023.

- Suzanne Speak. The State of Homelessness in Developing Countries. 2016.

- Benedict Osei Asibey1* ECaBM.

- United Nations Human Rights Office of High Commissioner. Women and the right to adequate housing 2025 [Available from: ohchr.org.

- Everlyne Rotich IM, Irene Marete, Faith Yego, Miquel Bennasar Veny, Berta Artigas Lelong. Being homeless: reasons and challenges faced by affected women.. African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2012;6(1), :41-8. [CrossRef]

- Nan Shao. The Crisis of Older Women’s Homelessness: A Case Study of Australia. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 2024;42. [CrossRef]

- Selina Tually UoSA, Deirdre Tedmanson UoSA, Daphne Habibis UoT, Kelly McKinley UoSA, Skye Akbar UoSA, Alwin Chong UoSA, et al.

- Ana Carolina Peixoto do NascimentoORCID Icon ABIADG. Housing first for people experiencing homelessness in Brazil and worldwide: an integrative literature characterizing similarities and differences. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abe Oudshoorn AVB, Colleen Van Loon,. A History of Women’s Homelessness: The Making of a Crisis Journal of social inclusion. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Elisabet Mattsson1, Marléne Lindblad3, Åsa Kneck2, Martin Salzmann-Eriksson4, Anna Klarare1,2, Women a, Health5 ABfI.

Figure 1.

depicts the interconnected pathways linking cultural norms to women’s homelessness and the resulting health outcomes. Green boxes represent enabling and structural factors such as feminism and intersectionality, while yellow boxes indicate contextual and regional influences, including geographic regions, life-course stages, and historical timelines. Blue boxes highlight barriers and negative factors, including women’s homelessness, stigma, and barriers to healthcare. The arrows illustrate the directional flow between determinants, mediators, and outcomes, showing how these forces interact over time. The health outcomes box encompasses five key dimensions: clinical, surgical, patient-reported, societal, and environmental, reflecting the broad impacts of homelessness on women’s health.

Figure 1.

depicts the interconnected pathways linking cultural norms to women’s homelessness and the resulting health outcomes. Green boxes represent enabling and structural factors such as feminism and intersectionality, while yellow boxes indicate contextual and regional influences, including geographic regions, life-course stages, and historical timelines. Blue boxes highlight barriers and negative factors, including women’s homelessness, stigma, and barriers to healthcare. The arrows illustrate the directional flow between determinants, mediators, and outcomes, showing how these forces interact over time. The health outcomes box encompasses five key dimensions: clinical, surgical, patient-reported, societal, and environmental, reflecting the broad impacts of homelessness on women’s health.

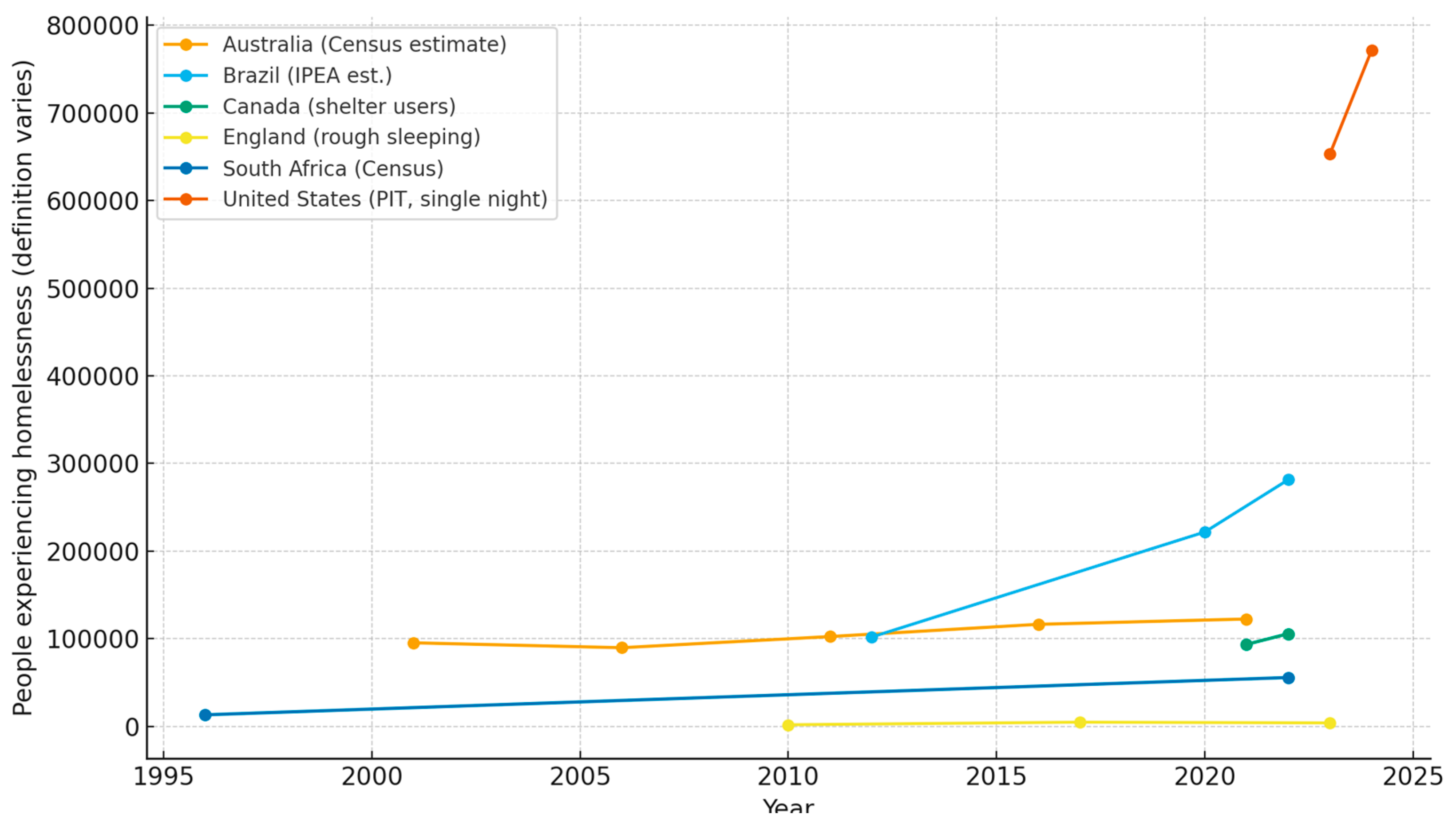

Figure 2.

shows homelessness trends using the most authoritative national publicly available data series available, recognising that definitions vary significantly across countries (e.g., rough sleeping vs. sheltered populations vs. census-based estimates). Data sources include: United States – HUD Point-in-Time single-night counts [2023,2024]; England – Autumn rough sleeping snapshot (2010, 2017, 2023); Australia – ABS Census estimates (2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021); Canada – National Shelter Study (2021–2022); South Africa – Stats SA Census counts [1996,2022]; Brazil – IPEA national estimates (2012, 2020, 2022). Important note: These datasets are not directly comparable across countries and should be interpreted as separate indicators of homelessness within their respective contexts.

Figure 2.

shows homelessness trends using the most authoritative national publicly available data series available, recognising that definitions vary significantly across countries (e.g., rough sleeping vs. sheltered populations vs. census-based estimates). Data sources include: United States – HUD Point-in-Time single-night counts [2023,2024]; England – Autumn rough sleeping snapshot (2010, 2017, 2023); Australia – ABS Census estimates (2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021); Canada – National Shelter Study (2021–2022); South Africa – Stats SA Census counts [1996,2022]; Brazil – IPEA national estimates (2012, 2020, 2022). Important note: These datasets are not directly comparable across countries and should be interpreted as separate indicators of homelessness within their respective contexts.

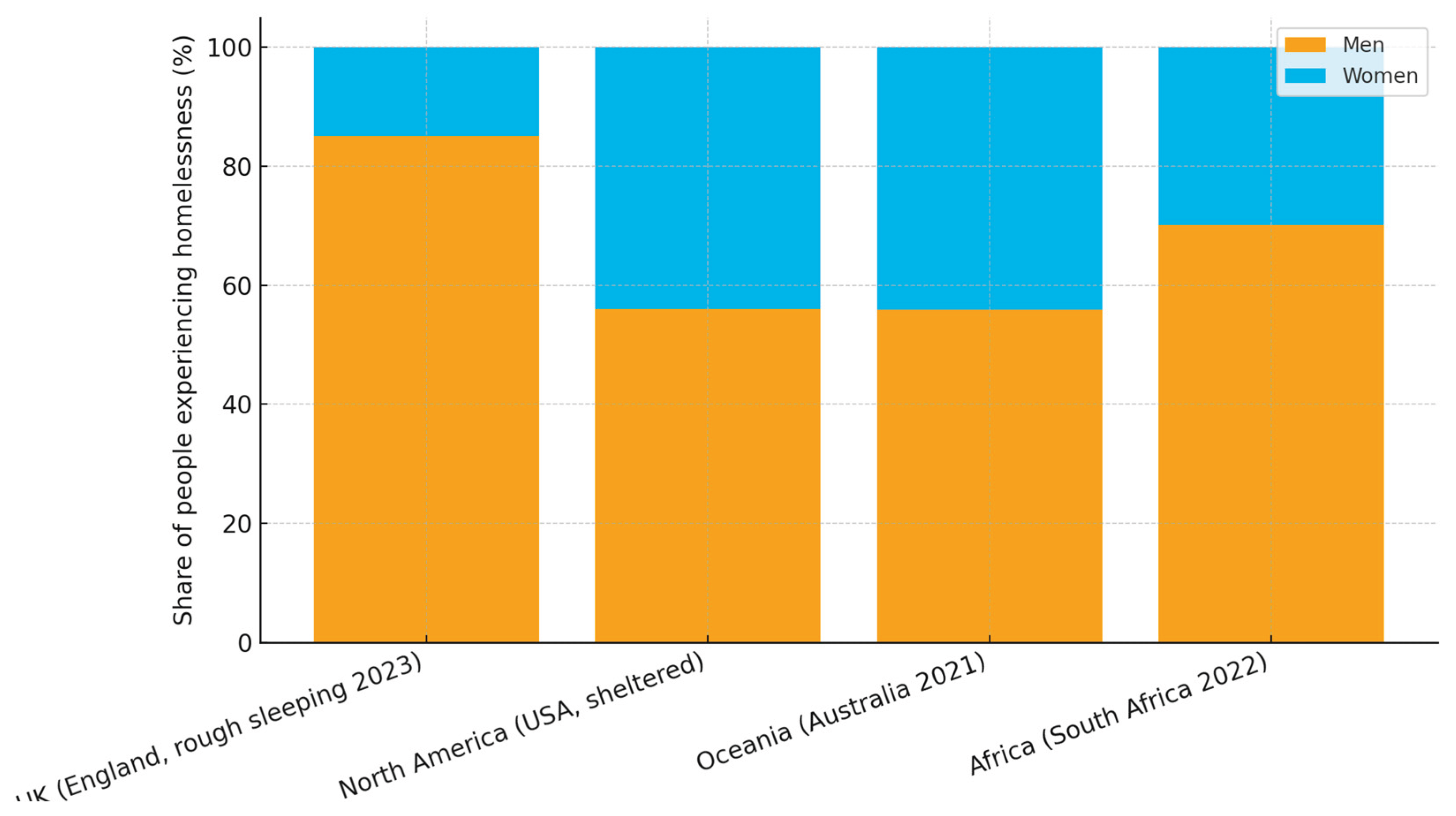

Figure 3.

presents the latest available gender-disaggregated homelessness data for regions with reliable, clearly defined statistics. Reported shares are: UK (England, 2023 rough sleeping): Women 15%, Men 85%; North America (USA, sheltered population): Women ≈44%, Men ≈56%; Oceania (Australia, 2021 Census): Women 44.1%, Men 55.9%; Africa (South Africa, 2022 Census): Women 29.9%, Men 70.1%. For Europe (excluding UK), Asia, South America, and the Middle East, there is currently no consistent, comparable data due to variations in definitions and undercounting of hidden homelessness.

Figure 3.

presents the latest available gender-disaggregated homelessness data for regions with reliable, clearly defined statistics. Reported shares are: UK (England, 2023 rough sleeping): Women 15%, Men 85%; North America (USA, sheltered population): Women ≈44%, Men ≈56%; Oceania (Australia, 2021 Census): Women 44.1%, Men 55.9%; Africa (South Africa, 2022 Census): Women 29.9%, Men 70.1%. For Europe (excluding UK), Asia, South America, and the Middle East, there is currently no consistent, comparable data due to variations in definitions and undercounting of hidden homelessness.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).