1. Introduction

Rising rates of respiratory diseases across Europe have caused increasing alarm among policymakers, public health authorities, and environmental researchers. Regarding shifting air quality, changing energy futures, and climatic stress caused by urbanization and climate change, understanding the mechanisms by which environmental conditions and infrastructure contribute to respiratory mortality has emerged as a priority for public health. Despite the vital contributions in environmental epidemiology, many previous studies have been sectoral or fragmented in scope, often failing to consider the systemic integration between ecological, infrastructural, and climatic variables. Such compartmentalization in methodology has led to the widespread application of linear or econometric models, which are not capable of capturing the multidimensionality and spatial heterogeneity characteristic of environmental-health linkages. Such gaps have been addressed by recent studies. For instance, Genowska et al. (2023) provide Polish birth cohort evidence associating robustly industrious air pollution with respiratory mortality, while Liu et al. (2022) and Gutman et al. (2022) unveil long-term air pollution exposure to extensively increase mortality due to pneumonia, as well as acute respiratory distress syndrome, respectively, across large European cohorts. Similarly, the EXHAUSTION project (Zafeiratou et al., 2023) reveals the mediation by localized climatic features, such as heat exposure, of respiratory mortality across the scale of small areas. Such findings reaffirm the need for multiscale, contextualized modeling, which is rare in mainstream approaches. This paper fills these gaps by offering an expansive, data-intensive description of the determinants of respiratory disease mortality (TRD) across European nation-states, utilizing a combined methodology of econometric regression, machine learning (KNN), and network analysis. Our principal research question is: How do structural environmental variables—electricity access, freshwater withdrawals, sanitation coverage, agricultural land use, fossil and renewable energy use, and heat-related climatic stress—intersect to influence respiratory disease mortality across European national contexts? Second, the present study extends prior findings in the literature exploring the broader determinants of respiratory health. For instance, Bush et al. (2024) and Yang & Zou (2025) pay attention to the role of social and subjective environmental determinants—early-life exposure and perceived ecologic quality—ramifying with material infrastructure in long-term respiratory endpoints. In a similar manner, Xu et al. (2023) and Zhang et al. (2024) provide evidence that cause-specific respiratory mortality is mediated by environmental greenness, as well as by long-term aerosol exposure, with a preference for combination with air pollution. Such findings mirror the non-linear effects uncovered by the KNN models in this paper, specifically for renewable energy sources (RENE) and sanitation exposure (SANS), with context-dependent relations with TRD. In an alternative spatial-epidemiological line, Cortes-Ramirez et al. (2023) unveil respiratory infection risk mapping across Colombian urban divisions, highlighting the value of high-grain, location-specific analysis—a strategy repeated here through European environmental-health profile clustering, as well as density-based partitioning. Prieto-Flores et al. (2021) also identify geographic disparities in respiratory mortality in urban regions such as Madrid, emphasizing the spatially non-uniform environmental risk on which the current study’s cluster analysis focuses. In this sense, the study is novel on three key fronts. Firstly, the study increases the analytical scope by integrating environmental, structural, and climatic variables on an overarching high-dimensionality platform. Rather than ignoring or omitting one or two exposures, the study models multi-dependencies among variables such as land use, electrification, sanitation, and temperature stress. Secondly, its structural composition is multicomponent: its econometric models allow causal inference, machine learning models reveal non-linear interactions, yet network analysis preserves structural interdependencies—balancing the weaknesses or incapacities of mainstream statistical thinking. Thirdly, the study employs additive feature attribution procedures (similar to SHAP values) to visualize the model’s predictions for easier interpretation, with the intention that the results are not only statistically robust but also deployable. The model identifies variables such as agricultural land use (AGRL) and coal-based electricity (COAL) as consistently associated with high respiratory mortality, presumably due to their contribution to particulate pollution. In contrast, access to electricity (ELEC) and freshwater withdrawals (WTRW) are highlighted as protectants, presumably by virtue of enabling cleaner indoor conditions and access to better sanitation. Notably, sanitation (SANS) has a seemingly counterintuitive positive connection with TRD—potentially hinting at urban transition systems or correlated urban air pollution, similar to the results obtained by Pona et al. (2021), among others, on the inadequacy of using indicators based solely on physical infrastructure. Model comparison also identifies instance-based machine learning strategies—namely K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)—as better positioned than linear regression models in terms of prediction, due to their better ability to identify spatially nuanced, as well as structural, inclinations. This is particularly crucial, especially considering results such as those of Zhang et al. (2024), among others, including Liu et al. (2022), which report multi-exposure interactions for the risk of respiratory mortality. In unison, the network analysis employed in the current study depicts how variables such as sanitation, in addition to land use, hold key structural positions, serving as brokers between disparate environmental subsystem interactions. By grounding the analysis in cross-national panel data, the study offers not only theoretical novelty but also implementable knowledge for the construction of health-environment policy. Findings support growing calls for multisectoral, whole-of-society responses combining environmental planning, energy sector transitions, and public health interventions. Such an integration is crucial in mitigating the long-standing respiratory disease burden, particularly in light of increasing climatic volatility and urbanization pressures throughout Europe. In the long term, the paper makes an original contribution to the environmental health literature by deriving a multidimensional empirical model for the system complexity of respiratory mortality. This research directly aligns with the most current environmental health literature on climate, air pollution, infrastructure, and spatial health inequities—from long-term exposure studies to spatial inequity mapping—providing an empirical foundation for stronger, fairer, and contextually rooted policy countermeasures to respiratory disease throughout Europe and other regions.

Section 2 shows a comprehensive literature review that situates respiratory disease mortality within environmental, climatic, infrastructural, and social determinants, emphasizing oxidative stress pathways, climate impacts, and inequalities.

Section 3 shows the integrated analytical framework and variable definitions, detailing the eight key indicators (TRD, ELEC, AGRL, WTRW, CDD, COAL, SANS, RENE) that underpin the analysis.

Section 4 shows the econometric results from fixed- and random-effects panel models, while

Section 4.1 shows a robustness check with Driscoll–Kraay errors, confirming most associations but weakening significance for WTRW, CDD, and RENE.

Section 5 shows the use of DBSCAN clustering to uncover environmental-health profiles, while

Section 6 shows KNN regression as the best-performing predictive model, highlighting the influence of AGRL, RENE, and WTRW.

Section 7 shows the network analysis, exposing systemic interdependencies among variables.

Section 8 shows policy implications,

Section 9 shows analytical limitations, and

Section 10 shows the study’s conclusions on integrated approaches to respiratory health.

2. Literature Review

In an increasingly voluminous body of interdisciplinary literature, the realization is growing that respiratory health is not solely defined by direct pollutant exposures, but by the complex interlinkage between environmental, climatic, infrastructural, and socio-demographic determinants. Our selected articles provide a fundamental understanding of the multifaceted system, offering insights into causal mechanisms, distributional injustices, and the potential for integrative policy interventions. Such perspectives directly verify the evidence from our study, which innovates the field with systems-level, multi-methods analysis. With the combination of panel econometrics, machine learning (KNN), clustering, and network science, the study identifies agricultural land use (AGRL), sanitation (SANS), electricity access (ELEC), and climatic stress (CDD) as structural key drivers for respiratory disease mortality (TRD) in European contexts. At the mechanisms level, Albano et al. (2022) and Bălă et al. (2021) identify oxidative stress as an overarching biological pathway through which airborne toxins cause inflammation and tissue disruption in the respiratory system. Such evidence corroborates the connections between land use, sources of pollution, and respiratory mortality in your model, particularly where AGRL and COAL use function as surrogates for particulate exposures. In a similar measure, Lee et al. (2021) confirm that outdoor impurities, including PM, SO₂, and NO₂, are predominant precipitants for chronic respiratory disease. However, Maung et al. (2022) unveil that indoor exposures—including VOCs and cookstove-related particulates—amplify the risks among the vulnerable. Such evidence aligns with the findings in your study, which observed that expanded access to electricity (ELEC) has likely reduced respiratory mortality, most likely due to a decrease in indoor biomass dependence. Climate-related stress or stressors have a disproportionately severe effect on most workers. Agache et al. (2022) and Bell et al. (2024) list climate change as an aggravating factor among the determinants of respiratory health, with the mediating effect of extreme heat, quantified by Cooling Degree Days (CDD), in your study. Grigorieva & Lukyanets (2021) deconstruct the accretive effect of heat and pollution, echoing the evidence from your study on the interactive effect between environmental exposures. Momtazmanesh et al. (2023), in the GBD 2019 update, confirm the predominance of air pollution, climate, and occupational exposures as global risk factors for respiratory disease—directly replicating the explanatory power of COAL, AGRL, and SANS in your fixed-effects models. Urban configuration and greenness reveal themselves as principal mediating variables. Ali et al. (2022) and Bauwelinck et al. (2021) demonstrate that access to proximal urban green space reduces respiratory risk, particularly among the elderly. Bikis (2023) offers dual commentary on greenness, quantifying its buffering effect but cautioning its pollutant-trapping effect in poorly ventilated spots. Qualifiers are corroborated by your network and cluster analyses, which demonstrate context-sensitive connections between RENE, land use, and TRD. Additional corroboration is provided by Wu et al. (2021), whose results replicate that vegetation-based urban configurations hold promise for reducing respiratory burden when species selection, density, and spatial distance are optimized. Wu et al. (2024) corroborate the promise of roadside green space in enhancing air quality near old-age homes, highlighting the need for localized spatial interventions. Environmental benefits, however, are not programmatically distributed. Berberian et al. (2022) chronicle racialized gaps in respiratory health outcomes resulting from climate stress in the U.S., while Chang et al. (2024) critique the lack of global protocols addressing governmental respiratory inequities and the appreciation of Indigenous communities. Such inequities are revealed by Pona et al. (2021), who discover catastrophic infrastructural failings in Nigeria, challenging the assumption that access to services, including sanitation, will automatically bestow health benefits—a factor appearing in your counterintuitive conclusion that larger SANS corresponds positively with TRD, potentially indicating in-transition or unquantified urban density effects. COVID-19 has recently spotlighted the effect of compounded vulnerability. Bloom et al. (2021) reveal that individuals with pre-existing respiratory diseases enjoyed lower risks during the pandemic, indicating that environmental resilience must be coupled with public health readiness. This co-occurs with the time dummies in your study, registering the TRD peaks occurring during 2020–2021. Sophistication also arises from Silveyra et al. (2021), who reveal sex and gender differences in pulmonary responses to environmental challenges. Though not directly simulated by you, such heterogeneity provides an intriguing axis for future stratification. Likewise, Solomon et al. (2023) link environmental exposure to clinical progression in interstitial lung disease, providing pharmaceutical evidence—through pirfenidone—of how environment-elicited diseases necessitate both preventive and treatment strategies. Lastly, Wilkinson & Woodcock (2022) connect asthma inhaler environmental externalities, offering systems of health as both drivers and potential correctives for environmental loss. This is analogous to how you conclude that RENE has ambiguous effects on TRD, an artifact most likely where “renewables” would still be typical biomass. Collectively, these all provide support for three overarching findings: (1) respiratory health is governed by systemic interdependencies across environmental, climactic, infrastructural, and social scales; (2) biological, and clinical pathways—such as oxidative stress—provide mechanistic support for these relations; as well as (3) environmental health risks aren’t proportionally allocated, so need socially aware, cross-sectoral approaches. This European paper takes a step further by demonstrating how network centrality, clustering heterogeneity, and nonlinear predictive modeling (through KNN) can disclose hidden structures and also serve as foci for policy-amenable leverage. In doing so, it provides an excellent empirical foundation for constructing combined interventions with the potential to reduce the respiratory disease burden in an environmental change scenario (

Table 1).

3. Integrated Analytical Framework and Variable Definitions

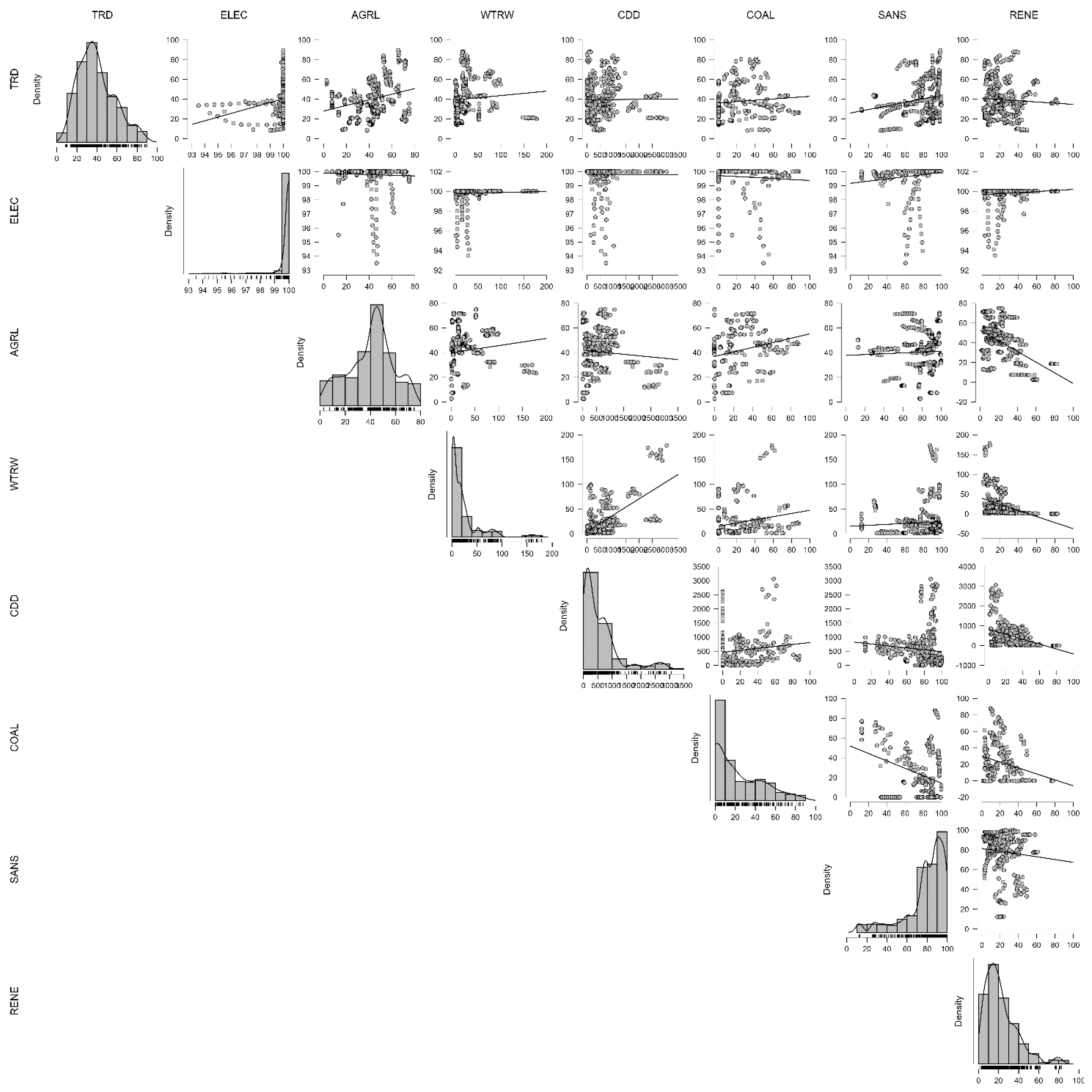

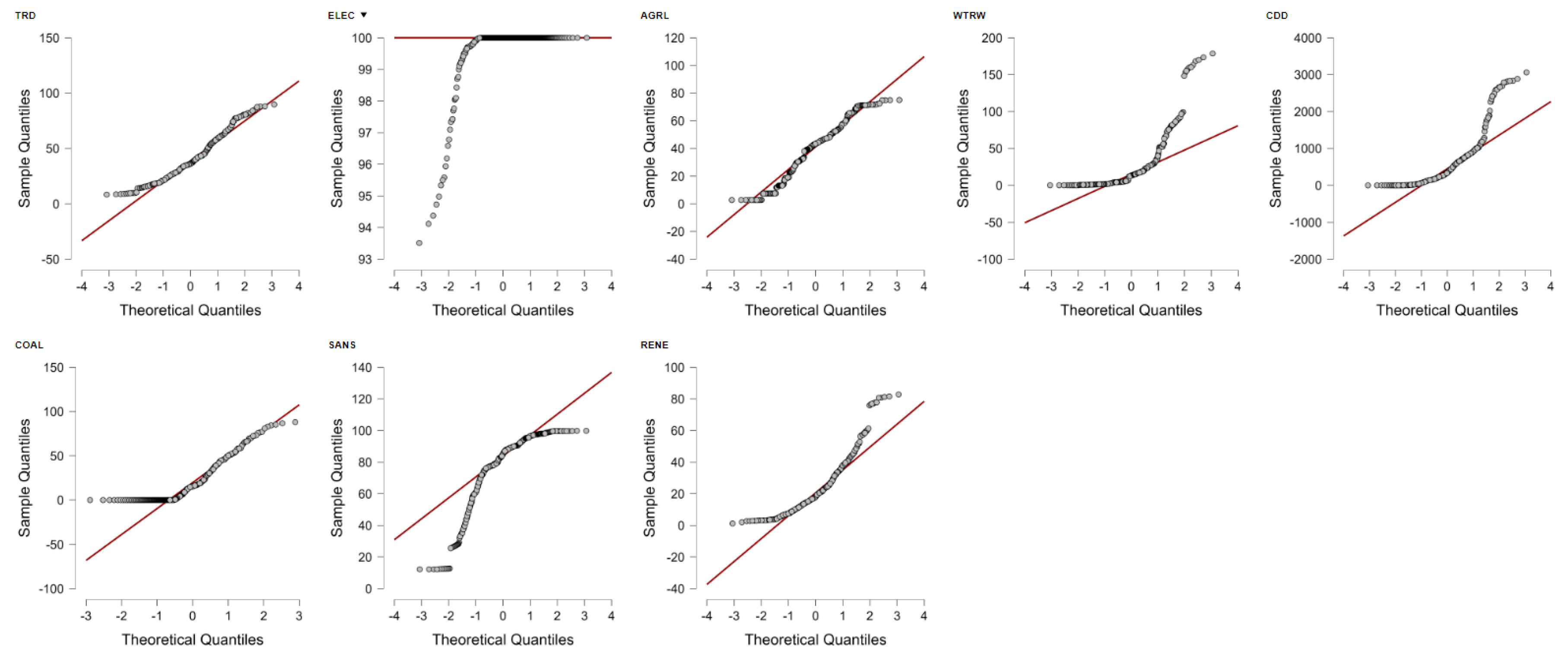

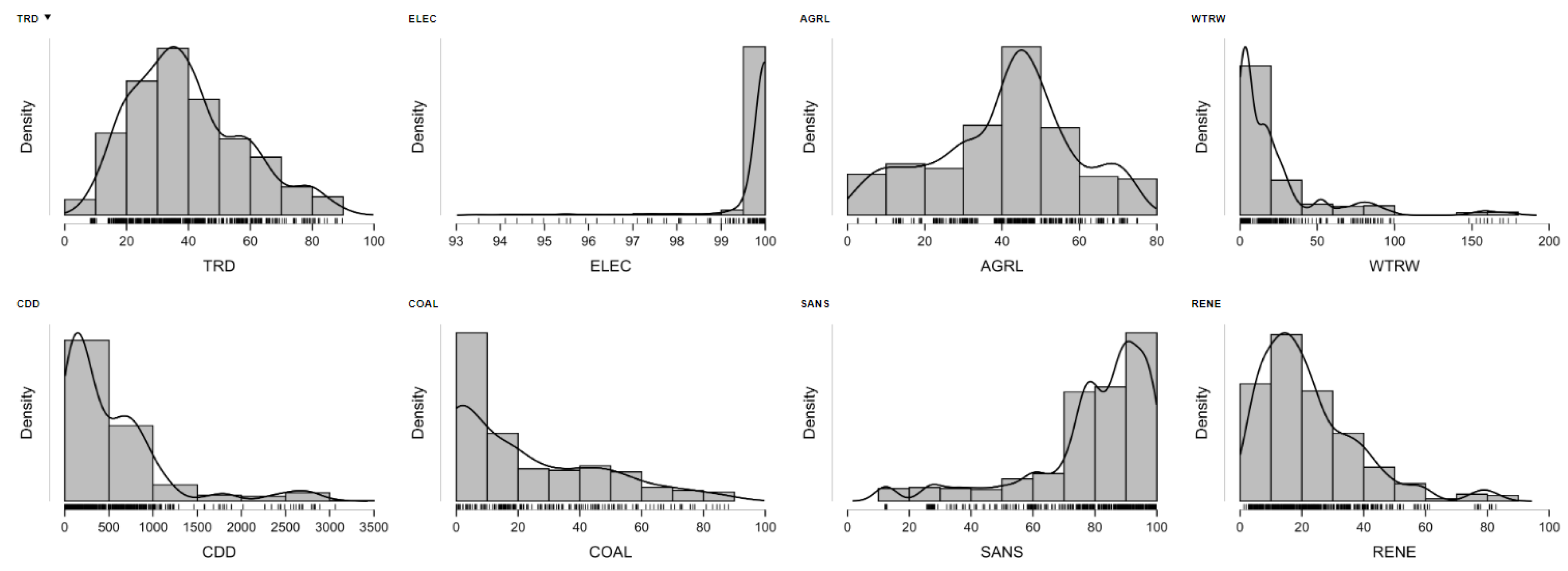

This quantitative analysis examines eight predictors for how environmental and infrastructural variables relate to respiratory disease mortality (TRD). TRD represents the number of deaths due to respiratory diseases for 100,000 residents. Access to electricity (ELEC) represents the proportion of the population with access to stable electric power. Agricultural land (AGRL) represents the proportion of cropland area. Water withdrawals (WTRW) represent the intensity of consumptive water. Cooling Degree Days (CDD) represent equivalent space cooling demand due to heat. Coal electricity (COAL) represents the proportion of power generated by coal. Safe sanitation (SANS) offers access to improved sanitation. Renewable energy (RENE) represents the proportion of clean energy. These indicators establish public health and sustainability (

Table 2).

Methodology. This study combines several analytical approaches, including panel data analysis, clustering methods, machine learning regression, and network analysis, to examine the environmental determinants of respiratory disease mortality among European states. In its multi-approach design, the study offers an in-depth, multi-level set of findings on complex relations across the space of infrastructure, climatic, and health variables. By connecting approaches instead of dividing them, the study presents an overarching analytical framework where each approach has its counterpart findings, providing validity as well as interpretation for the results. Allowing for identification over time as well as between-country dynamic effects, the analysis begins with the use of panel data models to estimate over-time changes in respiratory disease mortality relative to environmental variables. Allowing for identification over time as well as between countries, the models capture both persistence and variability across European country settings for effects. The models for identification feature both fixed effects models and random effects models, further substantiated by robustness checks across alternative settings for the models. In these approaches, Vasilescu et al. (2024) align with the author, who applies panel clustering regression across the analysis to explore income inequalities across the EU, with explicit consideration of the extent to which structural heterogeneity has the potential to provide policy-relevant findings. In a similar fashion to the Leogrande et al. (2022a) panel-based designs, the panel-based approaches feature methodology counterparts for exploring the dynamics of digital governance across European states, with the implication that panel econometrics offers useful approximations for the multi-country complexity. Having followed through on the findings across the econometrics, the study applies unsupervised clustering procedures—hierarchical, including DBSCAN (density-based clustering)—to identify typological subgroups with similar configurations across environmental health. These procedures identify structural heterogeneity across the dataset, providing insights into country typologies as well as combinations of variables associated with high or low mortality burdens. In its application for clustering, the approach investigated by Krstić (2023) examined climate change configurations across the EU, where the integration of regression and clustering identified varied regional trajectories. Similarly, Leogrande et al. (2023) employ the application of k-means clustering with predictive learning in the extraction of typologies from European scientific outputs, thereby offering evidence for the suitability of clustering for typological partitioning in high-dimensional data. To analyze the predictive relations, the study employs a set of supervised machine learning algorithms—viz. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)—to analyze the relations between the variables. All these are quantified with the performance metrics such as MSE, RMSE, MAE, and R². In these, the KNN algorithm emerges as the best-performing algorithm, striking a balance between predictive power and understandability. This outcome aligns with the results of Leogrande et al. (2022b), who employed machine learning regressions to examine the determinants of European digital literacy. The results indicate that instance-based algorithms, such as KNN, outperform their parametric counterparts in handling multidimensional, nonlinear relations. Model understandability is promoted through the application of additive feature attribution techniques (similar to SHAP), whereby predictions are broken down by identifying the contribution of individual predictors—a methodology also advocated by ML-attuned conduct, as proposed by Leogrande et al. (2023). This last analytical tier also employs network analysis to present the interdependencies between environmental, infrastructural, and climatic variables. Salient metrics, such as degree centrality, betweenness, closeness, and expected influence, are applied to identify variables playing structural hubs or bridges. Weights are quantified with the assistance of coefficients by the econometric models, as well as by machine learning algorithms, thereby combining the unifying predictive evidence with the inferential evidence on the network. This systemic perspective offers an overarching relevance to the contributions made by variables such as agricultural land use, sanitation, and water withdrawals—confirming the postulation that respiratory health is nested in an interactive environmental system. Joint application of these techniques is one of the study’s most robust findings. One among these compensates for the deficiencies revealed by the rest: panel data provides causal inference with the addition of temporal controls; clustering identifies heterogeneity with the addition of country typologies; machine learning identifies nonlinear, high-dimensional relations; and network analysis identifies systemic structure. This interdisciplinary forum offers best practices in environmental modeling, data science for climate issues, and digital governance studies. By doing so, the paper provides an interdisciplinary examination of the determinants of respiratory mortality, thereby enhancing both its empirical validity and policy usefulness. By combining structural insights with statistical rigor, the methodology demonstrates how the integration (and not the separate, solo application) of analytical strategies provides an optimal strategy for addressing complex public health challenges in the context of an environmental change regime (

Figure 1).

4. Environmental-Infrastructural Determinants of Respiratory Disease Mortality (TRD Model)

This subsection presents the primary econometric analysis, examining the impact of environmental and infrastructural indicators on total respiratory disease mortality (TRD) among European countries. Based on a panel data set comprising 238 observations across 38 national units over several years, the model specification accommodates both random-effects and fixed-effects regressions. Estimating the former, the primary objective is to identify the statistical connection between TRD and the explanatory set, which consists of access to power supply, agricultural proportion, abstracted water volumes, cooling degree days (used as a proxy for heat stress), coal-based power plants, safe sanitation, and renewable power penetration. Employing both random and fixed effects models, the analysis not only controls for the panel structure explicitly found in the data, but also for the possibility of unobserved country heterogeneity—a methodological practice consonant with recent European health and sustainability scholarship. For example, Stanciu et al. (2024) employ a similar panel data design to unravel the determinants of total mortality in the EU, highlighting the interactive effects among structural variables such as infrastructure, access to healthcare facilities, and environmental pressure on the construction of public health outcomes. Similarly, Andrei (2023) employs panel econometrics to analyze the environmental cost of economic growth among EU states, validating the importance of using fixed-effects specifications when examining complex, multivariate environmental-health relationships over the long term. A comparison between fixed and random effects, further enriched by diagnostic tests (e.g., Breusch–Pagan, Hausman, and joint significance tests), provides an evaluation of the robustness of the models as well as the validity of the specifications. This multilayered methodological practice ensures that the estimated TRD-environmental relations hold not only statistically but also substantively, thereby strengthening the policy relevance of the empirical findings. Notably, this study not only aligns with the larger strategy employed by the bulk of applied environmental health models but also contributes its voice to the emerging literature on socioeconomic-environmental determinants of population-level outcomes, in the tradition of life expectancy and disease burden. For example, Karma (2023) shows that socioeconomic indicators such as energy and the proportionate burden for infrastructure significantly impact the variability in life expectancy across Southeastern Europe—findings similar to the current study’s focus on the power supply access, the proportionate sanitation volume, and the proportionate volume for abstracted renewables in the construction that attaches to the construction for TRD. By integrating these layers of analysis, the econometric component provides empirical specificity as well as methodological rigor, offering an overarching picture of how infrastructural and environmental conditions shape respiratory health trajectories throughout European nation-states. We estimated the following equation:

Where i=41

1 and t=[2010;2021] (

Table 3).

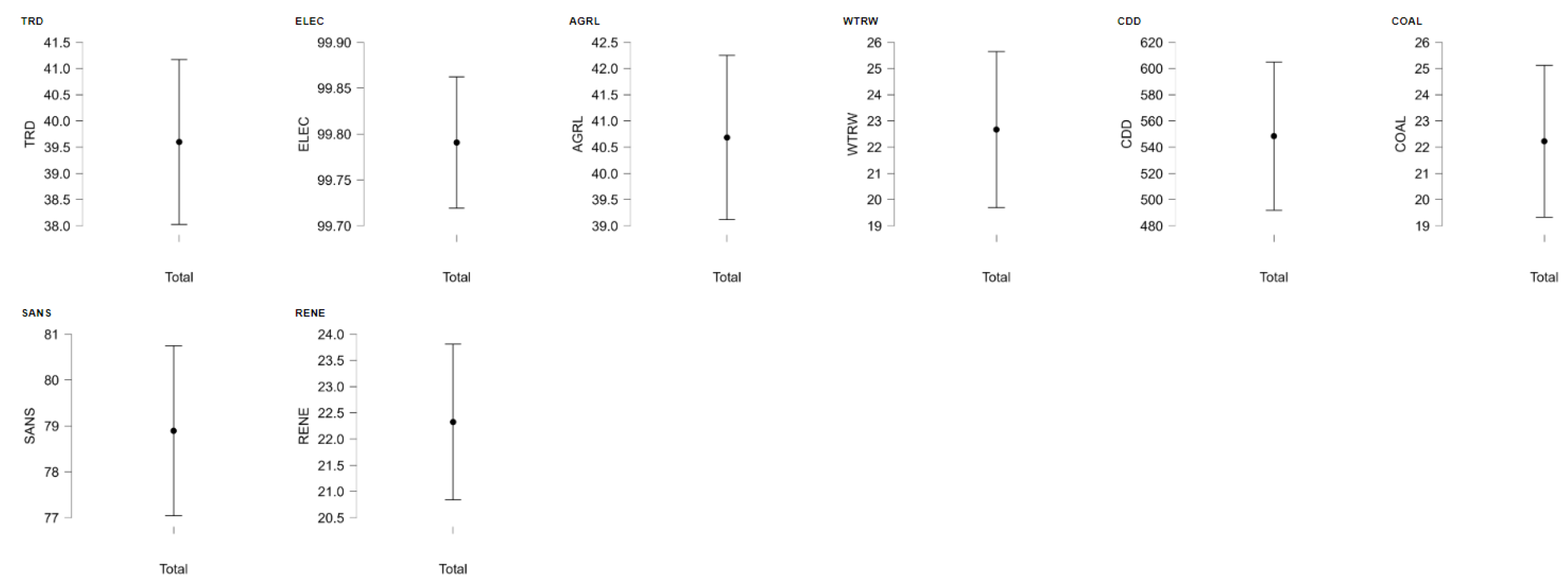

This discussion analyzes the determinants of respiratory disease mortality (TRD) across 38 national contexts by using an unbalanced panel data set with 238 observations across six to eleven years. TRD is defined as an energy access and composition function, with further controls for land use, freshwater withdrawals, climate heat stress, access to sanitation, and renewable energy penetration. We employ both random-effects generalized least squares (GLS) and fixed-effects estimation approaches, designing the specification to allow for robust analysis across all units as well as between-unit variance, while taking into account potential biases due to unobserved heterogeneity. This analytical arrangement follows on the heels of recent literature applying the panel data methodology for the analysis of environmental sustainability, energy transitions, as well as European climate adaptation (e.g., Galiński, 2023; Bonar, 2024; Andrei, 2023; Bytyqi et al., 2024), where the environmental stress-macro-/infra-variable interactions are increasingly analyzed using static as well as dynamic specifications. In particular, the GLS, as well as the fixed-effects arrangement, corresponds to some applied uses in public health epidemiology (e.g., Stanciu et al., 2024; see also environmental fiscal works by Anastasiou et al., 2024), providing support for the design’s robustness and practicability. TRD, the dependent variable, measures the number of respiratory-related deaths across 100,000 inhabitants, and it varies substantially across the panel (mean = 38.9; SD = 16.8), providing an informative interval for inference. Exogenous variables are power access (ELEC), agricultural shares (AGRL), freshwater withdrawals (WTRW), summer heat stress (cooling degree days; CDD), coal power for the purpose of electricity (COAL), access to safe sanitation (SANS), as well as renewable power force (electricity mix; RENE). In the random-effects setup, power access has a statistically significant protective effect on respiratory mortalities (coefficient: −0.8129; SE = 0.2515; z = −3.233), consistent with improved indoor air quality and better health access. This finding aligns with the broader European evidence on environmental health convergence during structural change (e.g., Wojciechowski et al., 2023; Mirović et al., 2021), where access to power infrastructure helps buffer population resilience against stressors caused by climate change and air pollution. In contrast, agricultural land share demonstrates a strong positive association (0.5151, SE = 0.1018, z = 5.061), potentially due to higher dust, drift of pesticides, or combustion of biomass—mechanisms characteristic for rural trace exposure pathways cited in agrarian-focussed health-environment studies (e.g., Maji & Boruah, 2025). Freshwater withdrawals (−0.1084, SE = 0.0395, z = −2.742) are negatively associated with TRD, presumably due to better hygiene infrastructure. Still, the interpretation must be corrected for the concern for the lack of ecological sustainability—a factor discussed in green growth evaluations for post-transition economies (see Andabayeva et al., 2025). Heat stress, operationalized through the term cooling degree days (CDD), emerges as the key risk factor (0.00449, SE = 0.00121, z = 3.694), aligning with the growing evidence linking weather-related thermal heat exposure to respiratory morbidity and mortality (Walkowiak et al., 2025). Similarly, coal-based electricity generation (0.1149, SE = 0.0416, z = 2.759) reaffirms the known respiratory risks associated with carbon-based energy sources (cf. Wojciechowski et al., 2023), while paralleling environmental tax and transition investigations in EU settings (Mirović et al., 2021). Positive coefficient for safe sanitation (SANS) (0.2605, SE = 0.0528, z = 4.929) comes somewhat counterintuitively, but potentially due to transition-phase or urban density or externality effects—findings which have nuanced meanings for public service expansion during rapid transformations (cf. Andrei, 2023; Stanciu et al., 2024). Similarly, the positive association for renewable energy penetration (RENE) (0.2497, SE = 0.0737, z = 3.390) may originate due to definitional ambiguity (e.g., inclusion or non-exclusion of traditional biomass) or transition-phase effects, highlighted in European- and Central Asian-type green economy studies (see Andabayeva et al., 2025). With the assumption for the fixed effects, results qualitatively hold: electricity access continues associating with lower TRD (−0.8178, SE = 0.2541, t = −3.218), agricultural land use registers an even larger positive effect (0.5987, SE = 0.1334, t = 4.486), and freshwater withdrawals associate protectively (−0.1364, SE = 0.0453, t = −3.009). Impact for CDD (0.00426), COAL (0.1209), SANS (0.2688), and RENE (0.2346) also holds with strong statistical support. Model fit statistics clearly favor the fixed-effects specification: the residual variance decreases from 60,652 to 766.6, the log-likelihood increases significantly (from −997.0 to −476.9), and all information criteria (AIC, BIC, HQIC) improve. The standard error of regression decreases by 16.2 to 1.99, also resulting in a better within-unit fit. Although fixed-effects models forgo the estimation of time-invariant covariates, they enable better control for latent heterogeneity—an issue also raised by fiscal and demographic panel studies (Anastasiou et al., 2024). Diagnostic checks reaffirm the panel structure. Both the Breusch–Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test (χ² = 580.15, p < 10⁻¹²⁷) and the F-test for heterogeneity across units (F = 341.85, p < 10⁻¹⁵⁶) both indicate using panel estimators. The Hausman test (χ² = 7.93, p = 0.339) indicates no statistically significant difference between fixed and random effects, corroborating the convergent validity of the approaches. High shrinkage parameter (θ = 0.9505) also supports the conclusion that the random-effects estimate approximates the fixed-effects estimate. Variance decomposition reveals that most variability in TRD occurs across countries (262.0) rather than within country observations (3.97), corroborating cross-sectional heterogeneity as the primary explanatory variation—a dynamic also observed in other EU-wide panel studies on mortality and environmental expenditure (Galiński, 2023). Positive serial correlation (ρ = 0.5004, Durbin–Watson = 0.7431) suggests the application of robust standard errors or dynamic specifications to correct the resulting downward bias, a point also raised by recent environmental panel studies (Mirović et al., 2021; Bytyqi et al., 2024). Despite this, the major results are robust across specifications and estimators. Joint tests support strong explanatory power: χ² = 109.1 (p < 10⁻²⁰) for random effects, F = 15.32 (p < 10⁻¹⁵) for fixed effects. Substantially, the effect sizes indicate that electrification lowers TRD by ~0.82 deaths per 100,000, and agricultural land expansion adds ~0.6 deaths. Heat exposure results in ~0.0045 deaths per degree per day, with coal-based electricity contributing ~0.12 deaths. Access to water protects, but sanitation and renewables paradoxically associate with high TRD—possibly due to compositional effects, urban unmeasured confounders, or policy implementation delays. Finally, the analysis offers robust, cross-validated panel evidence on the environmental and infrastructural determinants of respiratory mortality. The findings are robust, aligning with larger European panel data studies on energy, public finance, and health-environment interactions. They identify implementable channels—through electrification, climate adjustment, and structural reforms—through which environmental health performance can be improved, yet also present evidence on the complexity and transition nature of the European systems’ sustainability dynamics.

4.1. Robustness Analysis Using Driscoll–Kraay Standard Errors: Addressing Cross-Sectional Dependence and Temporal Correlation

To establish the reliability and credibility of the primary findings generated in the fixed- and random-effects panel estimations, robustness check with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors was conducted. Robustness checks feature as an integral part of empirical econometrics, especially when dealing with macro-panel data for numerous countries over the long haul. In these conditions, cross-sectional dependence, heteroskedasticity, and serial dependence are rampant validity dangers for inference. Heteroskedasticity-robust or clustered standard deviations would classically underestimate true standard deviations when the data feature cross-sectional dependence, hence generating overconfident test statistics. This problem is solved by the Driscoll–Kraay methodology by producing heteroskedasticity-consistent standard deviations resistant to quite general spatial as well as temporal dependence, hence facilitating more conservative yet plausible inference. Such adjustment comes particularly with the characteristic of the data: the European states are highly economically interdependent states, yet also highly interdependent states environmentally. This is expressed by the illustration by the observation by Yıldırım & Baycan (2023), where the booting energy productivity dynamics among the states in the EU would yield strong spatiotemporal dependencies whose effects would demand robust estimating strategies to avoid biased inference. In an alternative regional context, Fotio et al. (2024) demonstrate how environmental decay engages economic growth to determine the Sub-Saharan Africa child mortality, with particular reference to the need for observational spatially correlated processes when studying the health-environment relationships. Air pollutant diffusion, climate change stress, or coherent change resulting from policies (e.g., EU climate policies or COVID-19 pandemic change responses) instigate unobserved shocks to gain association across units as well as across time. Such is pertinent with regard to environmental and economic interdependence discussions relevant to the transition regimes where the blue economy, inclusive growth, as well as sustainability co-entwine (Han et al., 2025). Through the Driscoll–Kraay adjustment, potential bias resulting from such unobserved, spatially correlated processes is hence diminished, and the respective previous significant coefficients are tested with regard to whether they would persist in the stricter scale from which inference results (

Table 4).

The Driscoll–Kraay specification keeps the fixed-effects estimator for controlling unobserved, time-invariant unit-level heterogeneity but exchanges the standard error estimation procedure for one that corrects for autocorrelation as well as for spatial correlation, using two lags. The model has 238 observations through 38 countries, consistent with the previous fixed-effects format. Overall model fit is still respectable, with an in-the-walls R-squared = 0.3909, so that close to 39% of the variability in respiratory disease mortality (TRD), across countries, is explained by the covariates. Of key importance, the covariates’ joint significance remains ultra-strong (F(17, 10) = 62,298.16, p < 0.001), substantiating the explanatory power even with this stringent correction. Of policy relevance, access to electricity (ELEC) keeps its negative relationship with respiratory mortality (coefficient = −1.2757), but statistically less so (t = −2.16, p = 0.056), indicating marginal statistical significance at the 10% level. This is substantively informative and consonant with widespread evidence globally that electrification helps reduce the dependence on biomass in the household sector, hence removing many sources of bad air that cause respiratory diseases, especially in settings with weak rural electrification—transition economies among others—a factor also highlighted by Owusu & Acheampong (2025), who note the role of the green finance, renewable energy, and digitization in providing access, on the one hand, but also facilitating inclusive growth, on the other. Agriculture land share (AGRL), on the other hand, is robust (coefficient = 0.6356), remaining statistically significant (t = 3.75, p = 0.004), noting the enduring respiratory risk with agriculture activities, including dust, drift losses due to pesticides, as wells as field burning. This is consonant with environmental health concerns represented by Akther et al. (2025), when they researched the dynamics of the municipals wastes in Europe with rural mismanagement and particulates exposure potentially degrading the human body. Freshwater withdrawals (WTRW), on the other hand, insists on the coefficient with the minus sign, but with less statistical power (t = −1.93, p = 0.082), indicating how the access to clean freshwater has an indirect contribution to the respiratory health through hygiene and mitigation of diseases. This outcome is in line with broader evidence by Han et al. (2025), who emphasize the need for alignment between blue economy principles as well as inclusive growth for transition economies, as well as by Samreen & Majeed (2022), who emphasize the need for the socio-political as well as environmental quality determinants in the construction of population health as well as ecological footprints. Cooling degree days (CDD) also retains its positive sign (0.00366), but the relevance fades (t = 1.59, p = 0.143), corroborating the challenge in positively estimating temperature effects in models where the autocorrelations are a problem. In any event, the directionality is consistent with findings such as by Yıldırım & Baycan (2023), who present how energy intensity multiplies with climate stress to expand inefficiencies as well as environmental risks across the EU. The coal-based electricity (COAL) term retains its statistically significant association with high TRD (coefficient = 0.1122, t = 2.47, p = 0.033), reconfirming the relevance of coal as a major environmental health risk due to particulate emissions as well as poor air quality. This is comparable with the evidence by Chu & Le (2022), who suggest fossil fuel intensity as the major cause of the pollution-related health risk among G7 economies even when they control for policy uncertainty as well as economic sophistication. Safe sanitation access (SANS) among all the variables has the most stable as well as robust association with TRD, retaining high statistical relevance (coefficient = 0.1755, t = 5.13, p < 0.001). This is somewhat surprising but would most likely connect with urbanization dynamics as well as transition infrastructure, in line with Abdi et al. (2025), who suggest that population growth density as well as infrastructual transitions across Sub-Saharan Africa will often generate ecological as well as health trade-offs. Note the renewable energy proportion (RENE) loses statistical relevance when using the Driscoll–Kraay correction (t = 1.20, p = 0.259), although the coefficient remains positive (0.1252). This loss may originate with the collinear problem with other variables representing the infrastructure or the fact that traditional biomass is counted as “renewable.” Similar complexities are addressed by Ofori et al. (2024), who examine the interdependencies between trade as well as innovation in the deployment of renewable across BRICS as well as MINT economies, as well as Hashemizadeh et al. (2021), who explore the contribution of the fiscal ability as well as public debt to the construction of the renewable energy paths. All the dummies for the years 2011-2020 have positive and statistically significant coefficients, for instance, 2019 (4.1117, t = 5.94, p < 0.001) and 2020 (3.8436, t = 5.17, p < 0.001). These potential determinants for world shocks—COVID-19, mobility shifts, disruptions for the macroeconomy, and access shifts for healthcare—favor the inclusion for the year’s fixed effects. As noted by Tursunov et al. (2025), the application for robust estimate procedures for the handling for the attrition biases and the missingness manages validity for the unbalanced longitudinal data for health. Again, the constant term is large (121.0853), but imprecise (p = 0.083), as would be expected when controls abound with fixed effects. Altogether, the Driscoll–Kraay estimator supports the robustness for the major results but legitimately reduce the list for the statistically significant predictors. Electricity access, agricultural land use, coal energy, and sanitation facilities preserve the directional and often statistically significant associations with TRD. Meanwhile, the diminished significance for freshwater withdrawals, renewable energy, and heat stress reveal the statistical power-robustness trade-off for the working assumption on the distribution for the data. The results also support the major claim for the critical importance for the modernization for the primary physical structure, the energy transition, as well as the integration for the environmental policies, for the achievement for the better change for the respiratory health—particularly for the transition economies with the rapid change. This conclusion corresponds with the comprehensive green transition narrative established by Majeed & Hashemizadeh (2021), as also Andrei (2023), and is also re-iterated by the studies for the inclusive growth (and also the transition economy literature by Han et al., 2025), with the crucial implication for the balancing for the economic growth with the environmental integrity with the evidence-based platforms.

5. Uncovering Environmental-Health Profiles with Density-Based Clustering (DBSCAN): Methodological Validation and Policy Insights

In deriving strong environmental as well as health profile for Europe, the current study applied many clustering algorithms for the investigation for the mortality for the respiratory disease as well as the environmental determinants. Through the application for six standard validity indices—comprising Dunn Index, Calinski–Harabasz Index, as well as Minimum Separation—there was systematic checking for the performance for each individual separate model. Of the algorithms checked, Density-Based Clustering (DBSCAN) was the most successful for the optimal balance for the inter-cluster separeibility as well as the intra-cluster compactness. To entrench its robustness, individual validity checks through silhouette scores, measures for the homogeneity for individual separate clusters, as well as visual checking through the assistance through the K-Distance as well as the t-SNE plots, also ensued. DBSCAN’s ability for successfully handling the points for the noise as well as ability for the identification for the non-regular shapes for the respective congregating clusters best suit for their disparate environmental-health data, hence the reason for selection for individual separate interpretation as well as for policy-worthy partitionings. Similar advantages for DBSCAN also have been shown for many individual separate applications including the optimization for the monitoring environmental through individual separate improvements for the algorithms (Regilan & Hema, 2024), the clustering the social behaviour among the wastes (Al Jauhar et al., 2025), as well as for nation-based health insurance participation (Nurmayanti et al., 2022). All these explorations all revolve on the flexibility for the algorithm for the derivation for the embedded for the high-dimension complex datasets. In the derivation for the optimum-performing clustering algorithm for the European nation-based for the description for the mortality for the respiratory disease as well as its environmental determinants, many individual models also underwent checking with the six standard validity indices: Maximum Diameter, Minimum Separation, Pearson’s γ, Dunn Index, Entropy, as well as the Calinski–Harabasz Index. All these simultaneously estimate the intra-cluster compactness, the inter-cluster separeibility, the homogeneity, as well as the overall partitioning quality. Of the algorithms checked, DBSCAN is the best bet. This conclusion also finds an echo for the methodological improvements for the robust density-based clustering such as the partitioning through the assistance through DBSCAN+, for the individual separate statistical significance boost for the division for the datasets for the noisy (Xie et al., 2021). In the present study, DBSCAN had the highest minimum separation score as 1.00 with the Dunn index also as 1.00, indicating the best compactness as well as the best separation. This Pearson’s γ value for the DBSCAN as 0.62 reflects an accepting but not strong relationship between distances along with membership. Comparing with the Hierarchical Clustering where the best Pearson’s γ reached is 1.00 and the Calinski—Harabasz index reached is respectable 0.95 but where by the very low minimum separation (0.26), the Dunn index (0.44), it found its performance dampened for practical interpretation. Likewise, these weaknesses for the particular hierarchical and partitioning approaches have been reported in Saliba et al. (2025) for precipitation clustering for Romania as well as in Syahzaqi et al. (2024) for environmental pollution profiling for Indonesia. Fuzzy C-Means and Model-Based Clustering under-performed across all metrics, particularly in entropy reduction and cohesion. Neighborhood-Based Clustering reached the highest Calinski–Harabasz index (1.00) and entropy (0.95), but its very low minimum separation (0.14) shown revealed over-partitioning. Random Forest, however, occasionally strong for classification settings, failed to best DBSCAN on unsupervised metrics relevant for this data set. DBSCAN’s superiority is also demonstrated in recent comparative studies, e.g., its use for clustering obesity risk trends (Geovani et al., 2024) as well as for the policy analysis for circular economy (Henriques et al., 2022), where uncovering hidden structures possesses explicit policy usefulness. Further, the versatility for DBSCAN for public health settings has an echo for its successful integration for the illustration for the depiction for the forecasts for an epidemic (Papageorgiou, 2025). Altogether, DBSCAN achieves the best balance for compactness, for separation, as well as for generalizability, making it the most appropriate solution for the spatially segmenting for environmental-health data. By its robustness for the noxious shapes as for distribution with considerable noise, it ensures that the delicate interdependencies are preserved rather than over-simplified by the rigid use for the partition. By these facts, DBSCAN becomes the selected the best clustering algorithm for the characterization for the description for the environmental-health for the profiles for Europe (

Table 5).

Density-Based Clustering (DBSCAN), the top-performing unsupervised method by our comparison, demonstrates an unambiguous and meaningful separation of the data set in the data space into four clear clusters with one noise point. This corresponds with the intrinsic logic of the algorithm: it puts points in the clusters only when points are embedded in an appropriate density of neighbors so that core relations but not outliers are distinguished. Such insensitivity to noises as well as non-convex shapes of the clusters has furthermore been advocated for in advanced revisions on the method, for instance, DBSCAN+, adding statistical guarantees to density-based partitional clustering (Xie et al., 2021). In the current example, Cluster 1 dominates by 219 of 238 observations, indicating an intrinsic or majoritarian behavioral regularity in the environmental determinants across sampled countries. The other clusters (2, 3, and 4), with six observations only, are smaller in scale but potentially capturing edge regions or dissimilar policy conditions. Nevertheless, the smaller but high-cohesion-subclusters (2, 3, and 4) achieve highly high silhouette scores—0.853, 0.776, and 0.798 respectively—reflecting strong cohesion among points on the interior but excellent separation with regard to the rest of the clusters. We observe these outputs in line with the quality of DBSCAN to identify subgroups with high density but highly defined subgroups, shown for instance by the identification of pollutant monitoring sub-watersheds by the help of IoT (Regilan & Hema, 2024) through to geo-industrial clustering for Europe’s transition towards the circular economy (Mendez Alva et al., 2021). In contrast, the large but not exceptionally high silhouette score by part of the DBSCAN (0.165 by Cluster 1), suggests that the resulting DBSCAN group will bear some borderline points or heterogeneity on the interior. Explained proportion in the sense whereby the heterogeneity on the interior (and hence controlled by the respective shape parameters), it is exceptionally high for the overwhelming Cluster 1 (0.998), but near to zero for the other clusters, hence additionally emphasizing the overwhelming role for the DBSCAN-cluster 1 for the interior data structure. Following the very same tendency, the sum-of-squares-W (WSS) values are also most compact for the overwhelming DBSCAN-cluster 1 (WSS = 1.474), with the smaller DBSCAN-clusters also accepting appropriate dispersion for the number. All in all, the DBSCAN outputs indicate data where most sampled countries follow an individual environmental-mortality profile with few but distinctive cases on the outliers. Such smaller high-cohesion-subclusters may indicate exceptional socio-environmental paths, for which focused research in the policy analysis is justified (

Table 6).

DBSCAN-extracted cluster means reveal explicit segregation in environmental and infrastratural configurations with respiratory disease mortality (TRD). Most abundant set, Cluster 1 (n = 219), concentrates near zero on all the variables with the implication for a rather balanced and regular set with mean exposure values along with intermediate values for health outcomes. With mean TRD values of 0.096, it indicates an average mortality rate comparable with the total European trends. In comparison, Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 yield significantly negative values for TRD (−1.647 and −1.686, respectively), indicating significantly below-average mortality for the respiratory tract. However, their respective configurations differ considerably in terms of infrastruture. Cluster 0 with one data anomaly (noise point), registers the bottom values across all the variables, particularly for water (WTRW = −3.748), electricity (ELEC = −0.656), and has the potential for representing an ultra-underdeveloped or data-anomalous situation. On the contrary, Cluster 2 has exceptionally high access to electricity (ELEC = 3.129), high renewable energy penetration (RENE = 0.197), but low agricultural land use—dimensions harmonious with successful respiratory outcomes. Clusters 3 and 4 with below-average TRD values (−0.996 and −0.529, respectively), register high access to electricity (ELEC = 3.459 and 2.014), with exceptionally high values for RENE (4.436 and 1.886), indicating regions with highly developed renewable installations. However, these deviate on sanitation (SANS = −1.074 for Cluster 3), agricultural land use (AGRL = 1.316 for Cluster 3 but −0.964 for Cluster 4), indicating non-uniform modes of development. These differences reflect findings for De Ridder et al. (2024), who observe how the environmental variables combined with the geographical ones influence the health outcomes in contradictory ways, demonstrated in the space-time dispersion of SARS-CoV-2. Individually, these signify the manner in which low values for the respiratory mortality are accompanied by high electrification, integration with renewals, and efficacious use of resources but with sanitation service and agricultural land use nuances dampening the relationship. Efficacy in identifying such subtle clusters for DBSCAN also reflects its larger uses in environmental and social system analysis, ranging from optimizing monitoring of ecological parameters using the Internet of Things (IoT) (Regilan & Hema, 2023) to clustering behavioral indicators for managing wastes (Al Jauhar et al., 2025). Such observations also highlight context-specialized strategies for the infrastructure in contributing to the determinants of public health (

Table 7).

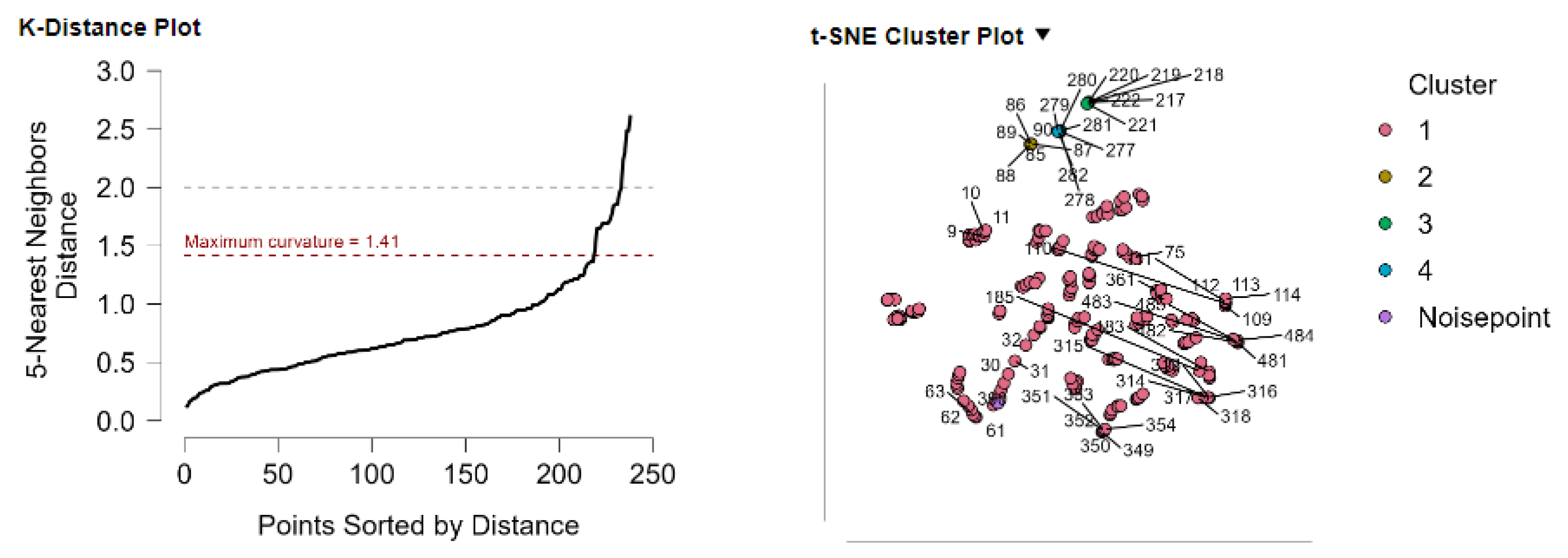

Figure 2 depicts two key visual diagnostics for validating and interpreting the DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) algorithm. To the left, the K-Distance Plot depicts the distance to the fifth nearest neighbor for each observation, in ascending order. We note an abrupt “elbow” at an approximate distance of 1.41, the equivalent to the curvature-maximum point itself, indicating an data-informed estimate for the epsilon (ε) parameter. This threshold is key in DBSCAN for the identification of the neighborhood radius where observations belong to the same cluster. Such data-driven parameter selection approaches follow along with current improvements in methodology, such as the K-NN–based ε calibration (Delgado & Morales, 2021), as with procedures for the stratified sampling in order to accurately refine DBSCAN parameterization (Monko & Kimura, 2023). This abrupt change after this point identifies the transition between denser clusters to less dense regions or potential outliers. To the right, the t-SNE Cluster Plot illustrates the two-dimensional embedding for the high-dimensional data space colored by the resulting membership for the identified clusters. Cluster 1 (pink), with most observations (n = 219), identifies the bulk as the central structure. In contrast, Clusters 2, 3, and 4 (yellow, green, blue), with six separated, compact observations each, indicate the identification of separate sub-structures for the data. One observation stands out identified by DBSCAN as an outlier (noise point; purple), an identification that holds correct. This visual evidence supports the successful identification by DBSCAN for relevant density-based structures successfully discriminating between the dense clusters, the transition regions, as with the isolated outliers. This combining the visual diagnostics with the outputs through the t-SNE visualizations is widespread recognized as an effective combination for the validation for non-linear structures across the multidimensional data (Bajal et al., 2022). This combination between the identification with the ε-threshold identification with the explicit space separation observed on the t-SNE plot supports the robustness for the identification by the algorithm for the complex non-linear groupings found on the environmental- and respiratory-mortality data (

Figure 2).

Lastly, application of Density-Based Clustering (DBSCAN) provides an optimal, context-adaptive method for discovering environmental-health profiles among the European states. With high performance on many validity indices and ability to discover well-separated, self-coherent groupings—along with noise points—DBSCAN holds promise for complex, heterogeneous data. Equivalent to broader DBSCAN application, such as for environmental monitoring with the IoT (Regilan & Hema, 2023), to clustering garbage management behavior (Al Jauhar et al., 2025), the algorithm excels in processing irregular, real-world data to reveal structural, hidden relations. In comparison with highly structured traditional clustering algorithms, DBSCAN accommodates the irregularity and diversity emanating in public health and environmental systems. Output typologies reveal an overarching bulk demarcating average conditions with smaller, distinctive clusters denoting characteristic developmental or infrastructural conditions. Such capability to map systemic differentiation complements its application for geo-based industrial clustering for urban symbiosis and circularity by European regions (Mendez Alva et al., 2021), where identification of centers of convergence/divergence provides sustainable policy directions. Such patterns as identifying respiratory mortality with the assistance of the likes of access to electric power, sanitation access, or renewable energy penetration not only validate the methodology selection but also provide policy-significant evidence on the reciprocal effects between the environmental exposures on the one, with respective health outcomes on the other. With identification connecting the dots between respiratory mortality with the assistance of electric power access, sanitation access, or renewable energy penetration, the analysis provides evidence for the imperative for bespoke, region-by-region intervention strategies. DBSCAN thus demonstrates itself as at once technology-justified, yet substantively relevant to the tools applied in the field for environmental-epidemiologic analysis as for the design for spatial health policy.

6. KNN Regression for Environmental Determinants of Respiratory Mortality

In exploring the predictive relationship between European respiratory disease mortality and environmental variables, many machine learning models (algorithms) were tested for their accuracy, robustness, and interpretation. Of these, the most successful strategy turned out to be the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm. With its non-parametric expression, with predictions rendered through similarity between data points in high dimensional space, KNN sidesteps parametric assumptions on data distribution, instead taking advantage of complex, non-linear interactions among variables. This is especially relevant in heterogeneous environmental-health data, where structural variability as well as context-specific relations between the variables abound. Such KNN efficacy for environmental as well as for health prediction has also been reported among other recent applications, including the prediction of air pollution (Evitania, 2023) as well as the identification of lung cancers (Moon & Jetawat, 2024). See the following analysis for the following in-depth discussion on the superior prediction ability of the KNN model, including comparative bench-marking among other algorithms and feature interpretation. See also the discussion on the advantage of additive interpretation for the identification of individual-variable contribution to predicted values. In conclusion, KNN proves not only statistically the best but also policy-informative, with high-grain observations on how the environmental conditions effect respiratory health outcomes. Of the machine learning models evaluated, the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm proves the most successful in the prediction performance of respiratory disease mortality, with the best performance across the board among all metrics for errors (Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)) as well as all indicators for the accuracy (R²). With normalised bench-mark values on all indicators—MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and R²—of 1.0, KNN reflects the best performance among all other algorithms in this comparison. Such best performance reflects the high compatibility between the data structure with KNN’s instance-based learning mechanism, one relying on similarity between observations rather than explicit parametric training. In high-complexity, heterogenous datasets such as this one—where non-linearity between the structure, environmental determinants, as well as health outcomes dominate—local decision-making by KNN excels. With the capability to identify high-grain relations without assuming linearity or distributional shape, the model offers flexibility useful for public health prediction. This performance corresponds with findings in other disciplines, where KNN has proven beneficial in functional time series modeling (Bouzebda et al., 2023), cardiology risk predictions (Ramani et al., 2023), and even drug use prognosis for the diagnosis of diseases (Farizki et al., 2024). Furthermore, additive feature contribution analysis points to variables such as agricultural land use (AGRL), renewable energy (RENE), and water withdrawals (WTRW) as playing primary roles in predictions, congruent with prior econometric findings. With strong statistical fit comes the capability to provide results that are interpretable, substantiating the value of KNN not simply for the power to predict but also for information beneficial for policy. Although models such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) also reached low rates of fault for particular metrics, their understandability and consistency were weaker, making these less desirable for the realm of policy. Lastly, the robustness of KNN in many dimensions of evaluation makes its selection as the optimum performing estimator for the purpose of approximating respiratory mortality justified, substantiating the role of spatial and infstructured nearness in the determination of the trajectory of health(

Table 8).

The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regression algorithm is the best performing regression model here, with an ideal normalized score of 1.0 across all the key performance indicators: MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and R². Such high predictive power suggests that the KNN indeed picks up the complex, non-linear relations between the environmental variables and the respiratory disease mortality (TRD) correctly in the data. Since the KNN is particularly an excellent non-parametric method for capturing non-regular patterns without an explicit assumption on the functional form, such an application becomes ideal where interactions between the variables are most likely to be multidimensional and non-linear. Such flexibility is reflective on its established usefulness in environmental applications such as air quality classification in Jakarta (Wiranata et al., 2023) and air pollution forecast models (Evitania, 2023), where the KNN accurately identified complex pollutant patterns in non-similar data. Feature importance analysis by mean dropout loss over 50 permutations provides evidence for this interpretation through the identification of the critical importance of some environmental variables. Agricultural land use (AGRL), with the highest dropout loss (13.4), and renewable energy sharing (RENE), with the next highest (13.1), suggest the critical importance these variables play in the determination of respiratory mortality predictions. These findings are in line with the econometric evidence, where the AGRL consistently expressed the positive association with the TRD—presumably due to particulate exposure due to rural land use—and the RENE expressed the ambiguous or context-laden results. Similar methodological corroboration for the robustness for the KNN for non-linear dependency extraction also comes in the field of functional regression, where the KNN has successfully been applied for quasi-association data on time series (Bouzebda et al., 2023). Water withdrawals (WTRW), with the next highest score, also scores high for the implication where the water structured by the water supply infrastructure determines the respiratory outcomes. Cooling degree days (CDD), similarly high-scoring, indicate heat stress as also determining the respiratory outcomes. Sanitation (SANS), less high-scoring but high, and coal energy (COAL), less high-scoring but high, yet again, indicate the relevance across the statistical as well as the machine regime. Access to electricity (ELEC), less impactful for this particular regime but yet again adds appreciably in the predictions. The additive prediction explanations yet again reveal how the KNN scales all the prediction relative to the base (mean TRD = 38.921), with variables in the likes of AGRL, CDD, and RENE placing strong upward or downward pressure on predicted mortality. Overall, KNN’s performance and interpretability render it a strong option for predictive modeling for environmental health analytics with the benefits of both high-precision predictions and policy-informative insights (

Table 9).

Additive explanations for the KNN predictions reveal the humble contribution by each environmental- as well as infrastructual- factor to the estimate for respiratory disease mortaluty through individual test cases. Through decomposing the predicted value in the base value as well as feature attributions, it becomes clear how conditions with wide variability exert effects on mortaluty in different directions as well as magnitudes. This procedure follows the growing application for the application of the use of interpretable machine learning techniques, where the techniques with bases on the SHAP- as well as feature attributions have found successful application in the medicine field, as the chronic kidney disease prediction (Gogoi & Valan, 2024), cardiac risk (Waqar et al., 2025), among others. In Case 1, for instance, severe adverse effects originate through agricultural land (AGRL = -3.982), freshwater withdrawals (WTRW = -3.652), as well as sanitation (SANS = -6.739), but severe favourable effects originate through the cooling degree days (CDD = +5.869), imposing severe upward force on the predicted mortaluty. This suggests high heat stress would greatly expand risk but some infrastructual attributes such as improved sanitation- as well as management of the water sector act to reduce these effects. Case 2, on the other hand, has an overall better performance where sanitation (SANS = +7.285), as well as renewable energy (RENE = +4.977), impose upward force on the prediction to near the base value. However, agricultural land- as well as water-variables exert force downwards. Of particular note is the manner through which renewable energy- as well as sanitation switch between conditions with negative- with positive-impact conditions across conditions, which identifies the context dependence for these variables. In Case 3, for instance, sanitation contributes +9.559 to the predicted mortaluty but in Case 5 contributes -7.829. Such variability informs the thesis that these indicators may capture transition effects on the sector or interactions with urban density or level of air pollution. What runs through all the five cases is the constantly adverse contribution by agricultural land- as well as freshwater-withdrawal variables on the lowering the prediction for respiratory mortaluty, further supporting the protective or mitigation effects for these regimes of the land use covering agriculture as an activity- or the type of water governance. Meanwhile, the effect by access to electricity (ELEC) is reduced or weaker with variability in the direction of site, suggesting that coverage with electric power supply or access in itself is insufficient where not balanced with clean sources of power or distribution thereof. Such explanatory additives enhance explanatory power for the KNN model and provide interpretable, instance-level insights that guide targeting environmental and public health interventions. This is part of broader trends in explainable AI, including its use for prediction of survivability for childhood respiratory disease (Kumar et al., 2024), showing its capability for trading off predictive power with clinical and policy usefulness (

Table 10).

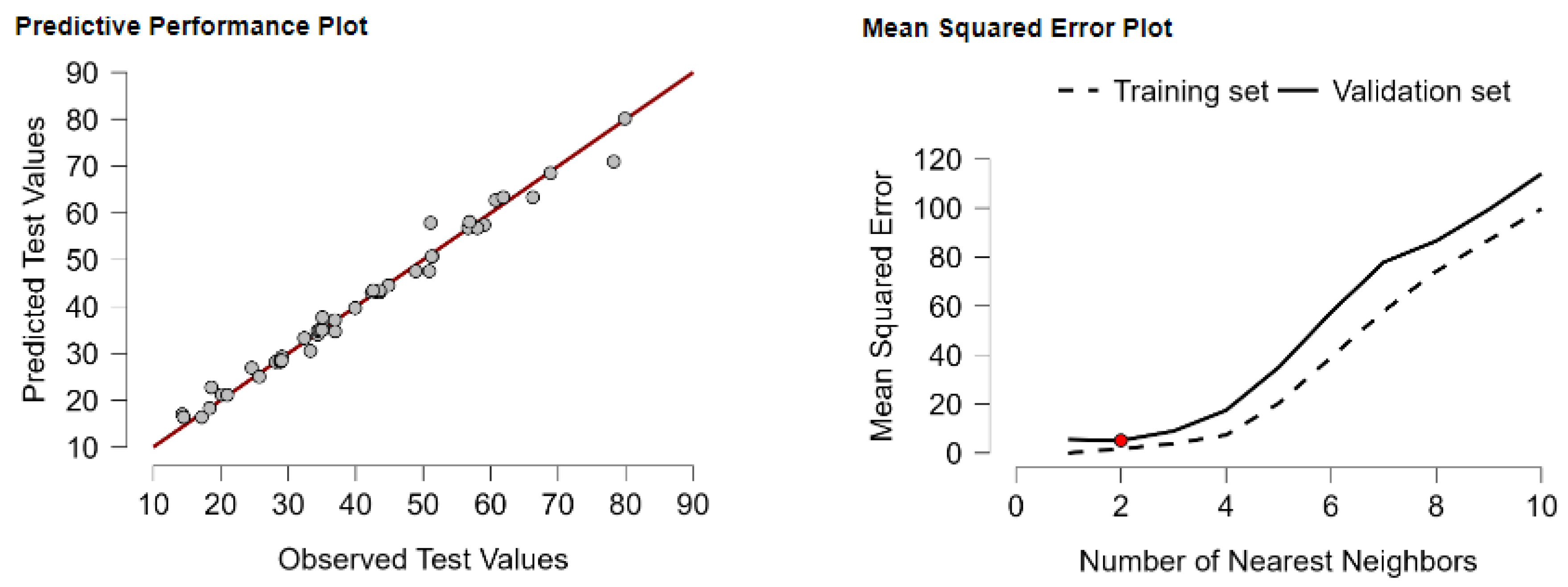

Two-panel figure demonstrating the strong predictive power and parameter calibration by the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) regression algorithm. Left panel, the Predictive Performance Plot, compares the observed vs. predicted values by the test set. Each data point represents a test observation where the ideal 1:1 correspondence between observed vs. predicted values is represented by the line in red. That the points close tightly around this line indicates strong predictive power, indicating the KNN algorithm is performing in an excellent manner in capturing the data structure. Similar results have been demonstrated for health-related outputs, where KNN correctly predicted risk for diabetes relative to Random Forest (Sudiatmika et al.) and reached robust findings for environmental yield prediction (Khan et al., 2022). There is minimal dispersion around the line, indicating the model doesn’t systematically over- or underpredict results. This close adherence visually substantiates the robust performance by the model using standard regression metrics such as minimal mean squared error (MSE) with high R-squared. Right panel, the Mean Squared Error Plot, demonstrates through plotting the values for the mean squared error (MSE) on the varying values for k, the number of neighboring points. By the U-curve exemplifying the characteristic bias-variance trade-off, when the number for the neighboring points stands low (particular for smaller values such as k = 1 or 2), the data over-fits by the model capturing the noise as signal such that the resulting variance is high with potential for unsound genizliciation. If the number for the neighboring points becomes too high, the predictions over-smoothes too much so the flexibility by the models drops with an increase for the bias. At the bottom left on the U-curve is the minima point on the validation set curve shown by the dot in red at k = 2, indicating the optimal neighbor selection the genidization error minimizes. One again with early prediction for gestational diabetes, the relevance for calibration for k has also highlighted with an optimized-parameter KNN classifier delivering results better relative to baseline models (Assegie et al., 2023). Of note, the distance between the curves for the data on the training set relative to the validation set becomes larger with an increase for the k, indicating when over-smoothing occurs with the loss by the models in flexibility. In unison, the plots confirm that the KNN algorithm when optimal for calibration performs robustly for the prediction for the outcomes by the respiratory mortality, thus validating the selection by the highest performing regression models with this analysis (

Figure 3).

In conclusion, the KNN algorithm possesses remarkable predictive potential, explanatory capability, and flexibility in representing respiratory disease mortality for environmental predictors. Through its non-parametric property, strong performance on all metrics for assessing models, and ability for representing local information without over-fitting, the algorithm becomes particularly fitting for high-complexity environmental-health data. Feature importance, as well as additive interpretation analysis, also support its safety and explicability, hence validating agricultural land, renewable power, and water intake as major drivers for respiratory health outcomes. Such attributes not only render KNN methodologically sound but also policy relevant for environmental health forecast as well as strategy.

7. Unveiling Environmental Interdependencies: A Network Analysis of Respiratory Mortality Determinants in Europe

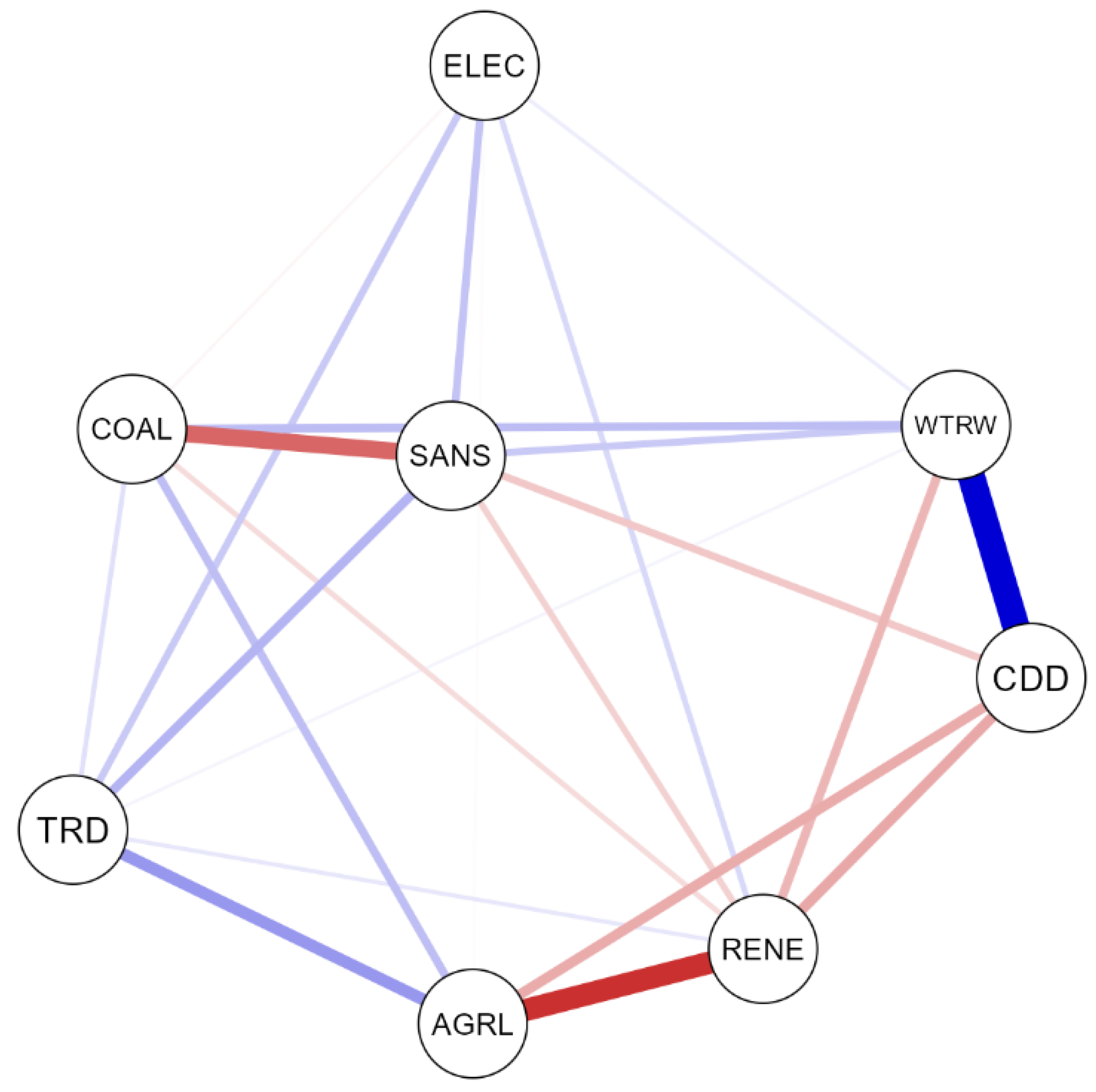

This part provides network-based analysis for the identification of complex interlinkages between environmental, infrastructural, and health-related variables for respiratory disease mortality in Europe. By estimating the structural relationships between eight key variables, the analysis reveals a relatively dense network where 23 among the 28 potential connections are non-zero. This results in the sparsity score of just 0.179, indicating that the vast majority of variables are linked instead of standing apart. Such an incredibly low level of sparsity points to an incredibly high level of mutual influence, so that shifts in one area or sector (e.g., for energy, sanitation, or agriculture) potentially ripple through the rest of the system. This highly connected structure provides an excellent canvas upon which to understand the results for the centrality measures, as the importance of the importance of the nodes grows with density. Such results are in line with prior evidence on spatial aggregation for respiratory mortality, for instance, the geographic health injustices defined for the city of Madrid (Prieto Flores et al., 2021), which similarly indicate the drivers of the risks on the system for the respiratory health. In short, the approach indicates the need for viewing respiratory health as the outcome for the operation of numerous co-occurring environmental as well as infrastructural conditions so as to develop across-the-board policy responses. The network analysis determines the distribution as relatively dense between the environmental variables with the variables for the infrastructures, with 23 among the potential 28 edges (connections between the variables) represented by non-zero values, thereby resulting in the sparsity value for 0.179. This indicates an implication that most variables in the network co-occur or exert influence conjointly. Practically, this offers insights to defend the assertion that respiratory health results not through an explicit set of determinants but rather through the complex interactions between conditions across many fronts. By way of example, the change in land use for agriculture would potentially co-vary with the access to energy or with withdrawals for the water, thereby offering yet further impetus for an across-the-board set of policy responses. This is consistent with the findings of Nepomuceno et al. (2022), who identify interdependencies as key in frontier approaches to the analysis of the efficiency of healthcare, demonstrating how performance is not typically caused by individual, lone drivers. The moderately dense network architecture also facilitates the interpretability of metrics for centrality and influence, which only acquire meaning when enough connections pervade the nodes. Similar results obtain in the climate-health literature, for example de Schrijver et al. (2023), who reveal that heat and cold vulnerability in Switzerland systematically differs between urban and rural communities, with an identification of the significance of contextual interdependencies for determining the nature of health (

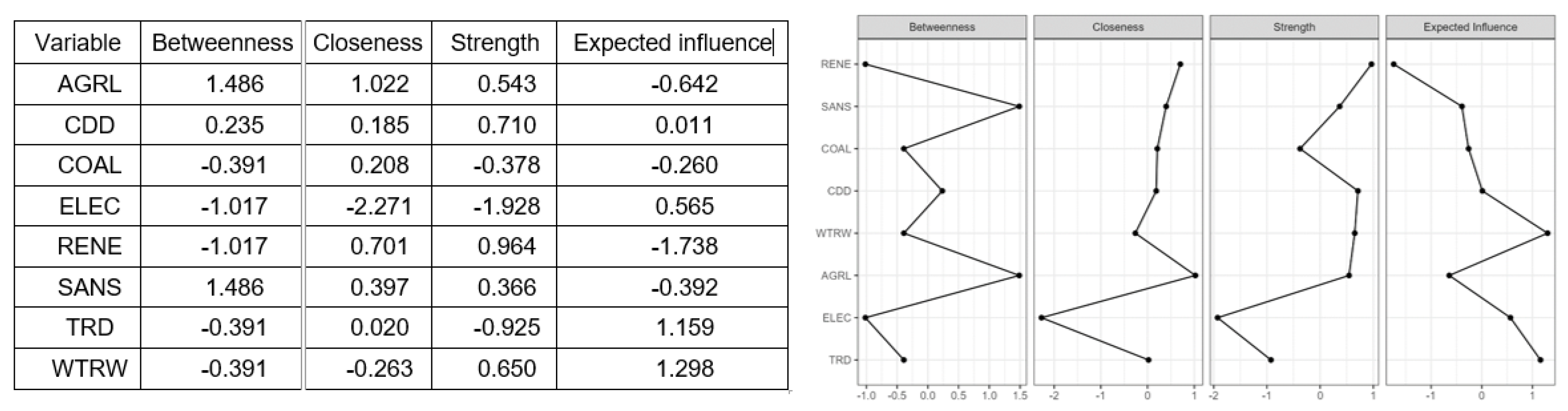

Table 11).

Betweenness and influence scores thus determined on the network analysis for the environmental and infrastructural variables reveal informative trends on the system of interrelations determining respiratory disease mortality (TRD). At all nodes, agricultural land (AGRL) and sanitation (SANS) also have the highest betweenness centrality scores (1.486), indicating that they play influential bridge or intermediate roles across the network, with potential transmission of effects between otherwise weakly connected variables. AGRL also has relative closeness centrality highness (1.022), indicating strong connectiveness with other nodes, but its expected influence is negative (−0.642), indicating on average that it reduces TRD considering its direct and indirect effects. This aligns with the model-based results advocating for its protective but context-dependent role. Such central nodes’ reinforcement in complex systems has parallel discussion in network science, where the identification of influential variables through the application of centrality measures represents an indispensable tool for the identification of system-level interactions (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2021). Comparatively, access to electricity (ELEC) has the most negative closeness (−2.271), indicating peripheral standing, but weak power-based cumulative interaction across the network (−1.928), yet its expected influence is positive (0.565), realizing potential benefits in the achievement of reduced respiratory mortality, especially through indirect channels. Renewable energy (RENE) has high connection with power (0.964), but has the most negative expected influence (−1.738), which may indicate combined effects in transition systems for energy, where renewables both modern (solar, wind), as well as ancient (biomass), co-exist. TRD itself has low-centrality scores but the highest expected influence (1.159), reaffirming its designation as reactive outcome. Of particular note, freshwater withdrawals (WTRW) have medium-centrality but highest expected influence (1.298), which points towards an influential indirect role in the establishment of the respiratory health. Cooling degree days (CDD), quantifying heat stressing, register medium power (0.710), but near-neutrality regarding expected influence (0.011), arguing for varying effects with dependence on context. In aggregate, these network results verify that variables such as AGRL, SANS, and WTRW are not only statistically significant in individual standing but also structurally central on the larger environmental-health interrelationship web, validating their priority for inclusion in focused policy intervention. Comparable findings hold for other environmental systems investigations, for instance, carbon footprint networks for global migration flows, wherein systemic impact is calculated by centrality (Li et al., 2024), and for future outlook models for air pollutant dynamics, wherein a series of interactive drivers co-determines results for exposure (Geng et al., 2023). Such analogs lend support to the interpretative relevance of the network perspective being adopted when conducting respiratory health analysis (

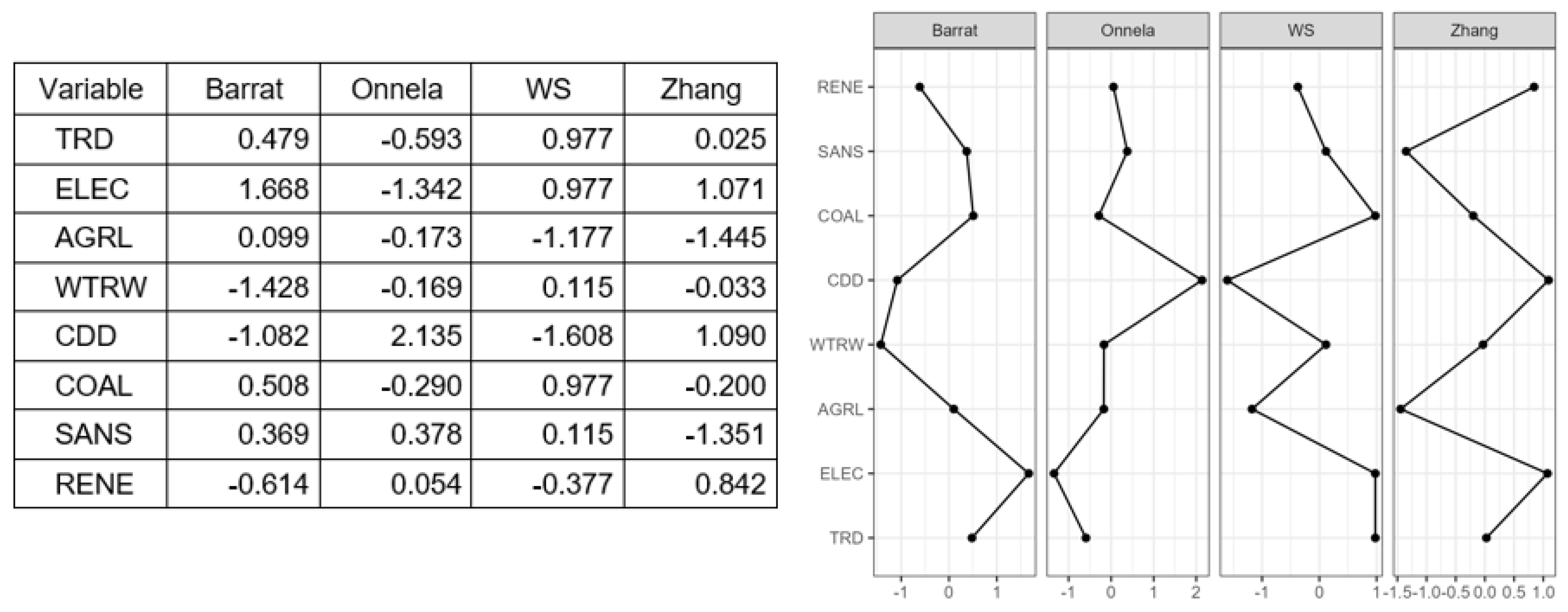

Figure 4).