1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) represents a significant shift where smart devices communicate over internet protocols, creating a vast network of intelligent systems. IoT has driven significant advancements in various areas, such as smart agriculture, industrial automation, and medical applications, which have greatly improved human life [

1]. Among these applications, smart health systems have become essential infrastructure, especially during the global COVID-19 pandemic, when telemedicine services were vital for maintaining public health [

2].

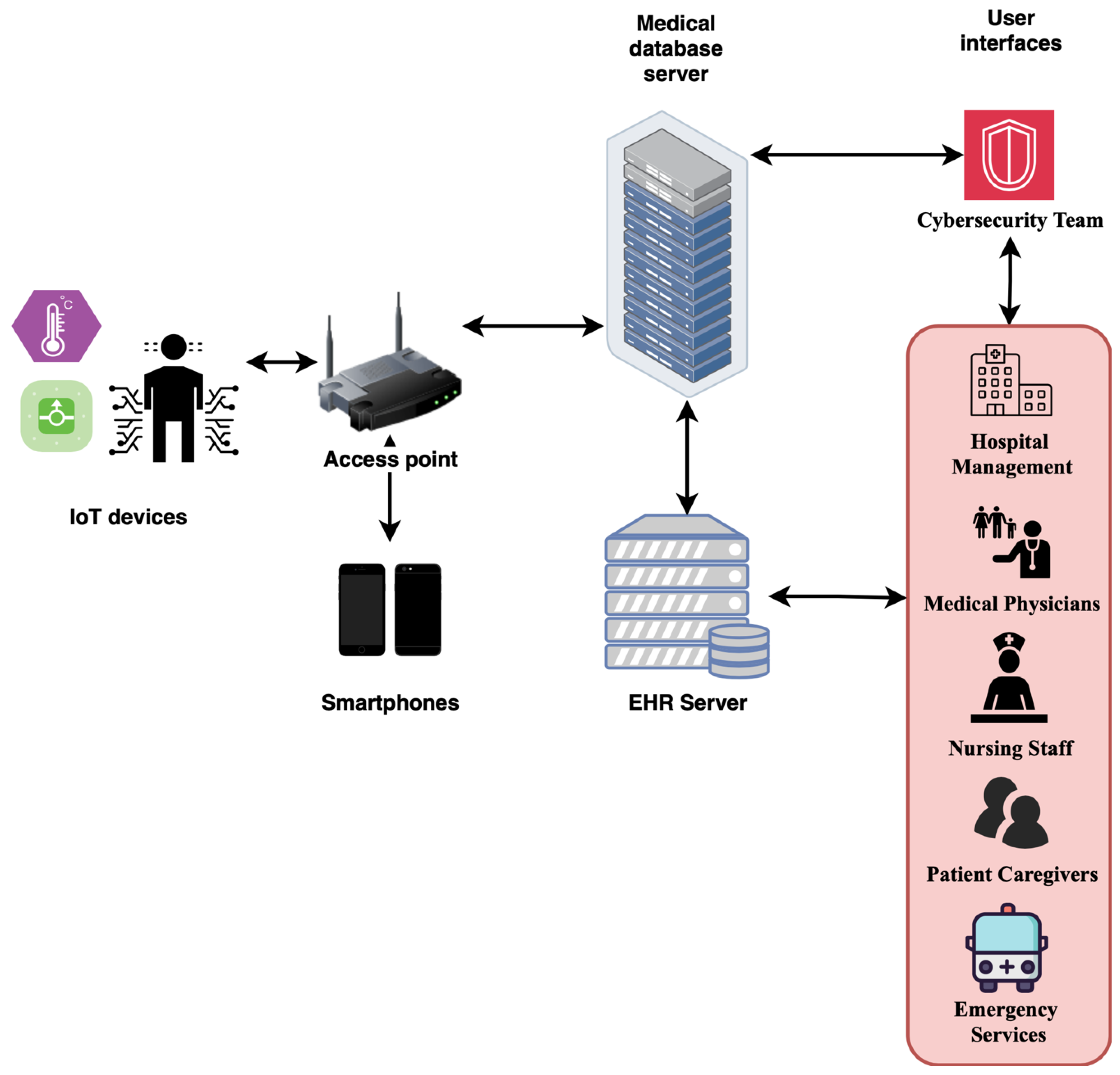

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) is a part of IoT that focuses on meeting medical needs with networked medical devices, sensors, and monitoring systems [

3,

4]. These systems provide continuous patient monitoring through wearable sensors, implantable sensors, and mobile health applications. This approach enables early medical intervention, which helps reduce healthcare costs and the need for hospital stays [

2]. Various stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, patients, caregivers, hospital administrators, and emergency responders, depend on safe and reliable IoMT systems to deliver effective healthcare.

As IoMT devices have increased, so have numerous cybersecurity threats that endanger healthcare systems and patient safety. Many of these connected devices have weak security features, including the absence of encryption protocols, inconsistent firmware updates, and unprotected data channels [

3]. These vulnerabilities make them prime targets for cybercriminals who might steal sensitive patient data and disrupt important healthcare services.

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks have become one of the most common and complex threats to Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) infrastructure [

5]. Unlike standard single-vector attacks, multi-vector DDoS attacks use multiple methods at the same time. They target weaknesses across different network layers to cause more damage and avoid detection. Recent statistics show a surprising 417% rise in multi-vector DDoS attacks. Healthcare systems in countries like India face about 1.9 million of these attacks each year.

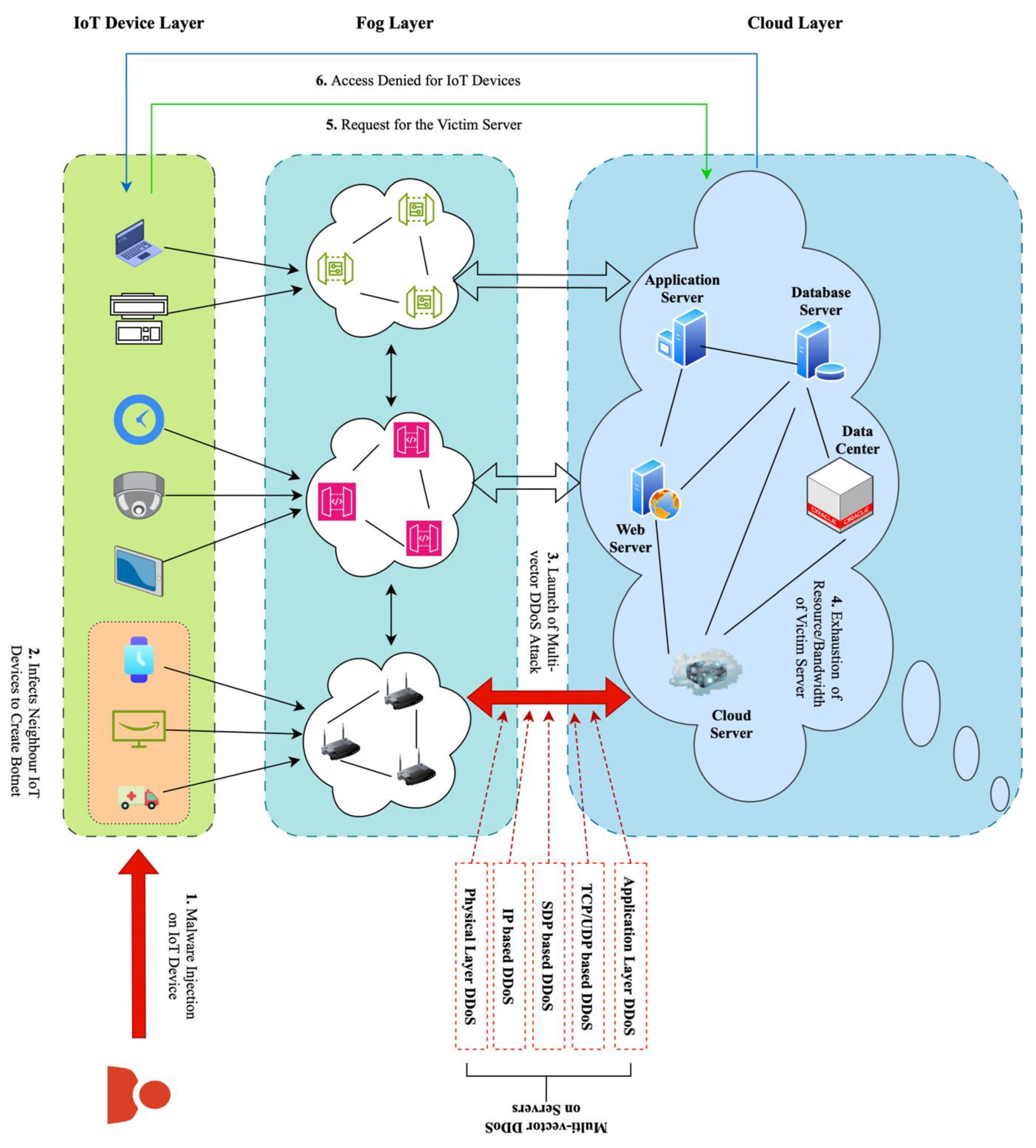

Multi-vector DDoS attacks generally unfold in six phases [

6] as shown in

Figure 1:

- 1)

Malware infects compromised IoT devices.

- 2)

The malware spreads through device-to-device infection to create botnets.

- 3)

Synchronized attacks occur using different methods (Layer 7 application-based, IP-based, TCP-based, UDP-based, and Service Discovery Protocol-based attacks).

- 4)

Resources are exhausted through bandwidth and processing overload.

- 5)

Legitimate service requests are blocked.

- 6)

Finally, this leads to denial of service for all legitimate users, regardless of their authenticity.

The evolving nature of these attacks adds to their complexity, with various attack vectors entering and exiting at different strengths throughout the attack [

6]. Traditional security solutions struggle to detect and address these threats due to their inability to handle the varied nature of the attacks.

Current intrusion detection systems (IDSs) fail to address multi-vector attacks in IoMT environments effectively. Traditional signature-based detection methods rely on predefined attack patterns, making them ineffective against new or evolving attack methods. Anomaly-based IDS can better detect unknown threats by establishing baseline behavior patterns, but they often produce high false positive rates and require significant computational power.

Recent research has looked into various machine learning methods for DDoS detection. These include Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machines, and deep learning techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [

7,

8]. However, high computational complexity, inadequate real-time processing, and insufficient adaptation to the specific needs of IoMT networks limit the majority of current solutions [

9,

10].

The limited resources of many IoMT devices further complicate the challenge and hinder the implementation of resource-intensive security measures [

11]. Additionally, the urgent nature of healthcare applications necessitates rapid detection and response to attacks, preventing potential harm to patients [

1].

The urgent need for IoMT security in healthcare delivery provides a compelling reason to develop advanced threat detection capabilities. Healthcare organizations face a unique risk; a security breach can lead to severe consequences beyond typical data loss or service outages. Recent reports indicate that 99% of healthcare networks have known exploited vulnerabilities, and 53% of connected devices are at risk of multi-vector DDoS attacks.

The need for user-specific detection systems arises from varying skills among healthcare stakeholders. For example, technical users, such as medical staff, require simple binary alerts to indicate the presence of security threats. In contrast, more experienced users need detailed information about specific attack vectors and exploited systems [

9]. This situation necessitates the creation of flexible detection frameworks that can provide appropriate information to different user groups.

Moreover, the growing use of mobile healthcare informatics systems adds complexity. These systems must ensure security while allowing for patient mobility and remote monitoring [

2]. The integration of Electronic Health Records (EHR) and medical database servers into mobile systems expands the attack surface and requires robust protection measures [

12].

This study addresses the gaps in multi-vector intrusion detection for IoMT systems and makes several important contributions.

We created an efficient anomaly-based intrusion detection framework using Modified Gated Recurrent Units (MGRU). This framework is designed specifically for multi-vector intrusion detection in resource-limited IoMT environments [

9]. The MGRU model outperforms traditional LSTM networks by reducing computational demands while maintaining effective sequence modeling for network traffic monitoring [

13].

We developed two detection classifiers to meet different user needs. The Binary Label Classifier (BLC) serves non-technical healthcare staff by providing basic notifications of attack presence, while the Multi-Label Classifier (MLC) offers technical users detailed information about attack vectors and categorization. This dual-classifier approach ensures that the correct information reaches various groups within healthcare facilities.

We conducted thorough testing using current datasets, specifically the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets, as well as genetic algorithm-based feature selection to optimize detection performance [

14,

15]. The testing assesses various performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, sensitivity, specificity, false alarm rate (FAR), false positive rate (FPR), Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), model size, training time, and attack detection time [

16,

17].

We evaluate MGRU's performance against previous intrusion detection models, highlighting the benefits of a genetic algorithm-based feature selection approach.

These results suggest that combining genetic algorithms with stacked MGRU networks can significantly enhance intrusion detection efficiency in IoT healthcare settings.

The remainder of the study is structured to provide a detailed discussion of the proposed research methods and findings.

Section 2 reviews current literature on intrusion detection systems for IoT-enabled healthcare networks, covering existing methods and identifying research gaps.

Section 3 describes the theoretical basis of the improved Gated Recurrent Unit architecture and the enhancements that boost performance for cybersecurity tasks.

Section 4 outlines the careful selection and preprocessing of datasets, explaining why we chose particular datasets and how we employed a genetic algorithm-based feature selection.

Section 5 explains the overall design of the proposed intrusion detection framework. It covers the architecture, implementation, and integration of the two detection engines.

Section 6 presents experimental evaluation results. It compares the proposed system's performance with that of other methods using various metrics and datasets.

Section 7 discusses the complexity and computational costs of the proposed framework. It includes scalability challenges and implementation issues. Finally,

Section 8 summarizes the research findings, addresses limitations, and suggests future research directions to improve IoMT security.

This framework enables a detailed examination of all aspects of the research. It covers theoretical concepts and real-world implementation. Through this, readers gain a complete understanding of the proposed multi-vector intrusion detection framework for IoMT systems.

2. Literature Review

Recent research has focused considerable attention on attack classification methods, specifically investigating binary versus multi-label classification methods for healthcare-specific threat detection. Researchers believe that mitigation strategies should not only detect malicious activities but also accurately identify the nature of attack vectors.

Previous efforts in this research area include the creation of realistic healthcare datasets by leading researchers. Experimental setups explicitly tailored for the capture of smart healthcare data by Hady et al. [

21] and Ahmed et al. [

25] resulted in the formulation of two large-scale datasets, namely WUSTL-EHMS-2020 and ECU-IoHT. These datasets have now emerged as reference tools for all future research, offering realistic healthcare IoT traffic patterns integrated with a range of attack models.

Table 1 shows a detailed overview of the related literature.

2.1. Deep Learning Approaches in Healthcare IDS

The ImmuneNet framework, which was introduced by Kumaar et al. [

18], is a novel deep learning-based hybrid IDS developed explicitly for smart health systems. The framework utilizes network traffic capture mechanisms via CICFlowMeter and Wireshark tools, focusing on detecting attacks in Electronic Health Records (EHRs) through binary classification methods. The system shows promise in integrating various detection methods to enhance the overall security posture in healthcare settings.

As a complement to this study, Patel et al. [

20] proposed a neural network-based intrusion detection system for cloud-based ECG healthcare data. Their method combines a hybrid Tempest algorithm with the Tempest-NN architecture, which extends beyond mere intrusion detection capability to incorporate arrhythmia classification functionality. This two-in-one system demonstrates the potential for healthcare IDS to provide both security and clinical decision support functionalities.

Current advances in deep learning for healthcare security have investigated advanced neural architectures. Dina et al. [

26] conducted extensive comparisons between Feed-forward Neural Networks (FNN) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in the context of IoT-based healthcare intrusion detection. Empirical analysis confirmed that FNN architectures yielded better performance than CNN techniques in specific healthcare attack detection scenarios, with accuracy rates exceeding 97%.

The use of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) has proven to be especially promising for the recognition of sequential patterns in healthcare IoT networks. Almutairi and Alshargabi [

27] developed RNN-based detection mechanisms trained using the NSL-KDD dataset and demonstrated 87% accuracy in multi-class attack classification. Their study identified the need for further optimization to enhance detection capabilities.

2.2. Lightweight IDS Solutions for Resource-Constrained Environments

The difficulty of implementing IDS solutions on resource-limited IoMT devices has driven extensive research into lightweight detection mechanisms. Ariffin et al. [

28] proposed a hybrid feature selection mechanism using XGBoost and MaxPoolingID techniques for MQTT-based IoT systems specifically. Their lightweight IDS measured 90% accuracy in both unidirectional and bidirectional traffic flow scenarios, with bidirectional analysis performing best in all evaluation metrics.

Iwendi et al. [

22] tackled feature optimization issues using a genetic algorithm implementation, this time applying to the KSL-KDD dataset for multi-label attack vector classification. Their method demonstrated significantly improved feature selection efficiency, reducing computation overhead without compromising detection accuracy. This paper laid the groundwork for follow-up research on evolutionary optimization methods for healthcare IDS.

Cross-validation frameworks and statistical testing of significance have become the standard for ensuring robust performance comparisons. Recent research [

42] has highlighted the need for addressing class imbalance and avoiding overfitting through sophisticated preprocessing methods, such as the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) and Quantile Transformer standardization.

The deployment of IDS in conjunction with edge computing paradigms has become a crucial area of research. Ma et al. [

33] deployed Random Forest classifiers with feature selection functions on edge computing devices in Software Defined Networking (SDN) settings. The performance achieved by their system was excellent, with 99.99% accuracy and prediction times of 0.4 seconds, proving the practicability of real-time threat detection at network edges.

Li et al. [

35] proposed FLEAM, a federated learning-enhanced architecture to mitigate DDoS attacks in Industrial IoT networks. Their distributed system achieved a detection accuracy of 98% by reducing mitigation response time by 72% and increasing the cost of attack by 2.7 times. This study shows that organizations can implement collaborative defense methods across dispersed healthcare networks.

2.3. Multi-Vector Attack Detection and Classification

Modern healthcare networks are increasingly vulnerable to advanced multi-vector DDoS attacks that exploit weaknesses across multiple network layers simultaneously. Ahmed et al. [

34] constructed a multilayer perceptron (MLP) deep learning model for detecting application-layer DDoS, emphasizing packet attribute analysis, such as HTTP frame lengths, IP address distributions, and port mapping patterns. Their method attained a 98.99% detection efficiency rate with a lower false positive rate of 2.11%.

The FlowGuard system proposed by Jia et al. [

39] is a milestone in traffic variation-based DDoS detection. It is an intelligent edge defensive mechanism that utilizes two machine learning models: LSTM networks for attack detection (with 98.9% accuracy) and CNN architectures for attack classification (with 99.9% accuracy). The system sufficiently supports IoT delay requirements while being implemented on edge servers with upgraded computational power.

Protocol-Based Deep Intrusion Detection (PB-DID), proposed by Zeeshan et al. [

37], solves the complexity of combining multiple dataset sources into robust training environments. They blend UNSWNB15 and Bot-IoT datasets, applying class imbalance handling methods and overfitting prevention strategies. The system achieved 96.3% accuracy in attack detection for the normal, DoS, and DDoS traffic classes.

Sangodoyin et al. [

40] performed a comprehensive analysis of machine learning algorithms for DDoS flooding attacks in SDN frameworks, comparing Classification and Regression Tree (CART), k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN), Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA), and Gaussian Naïve Bayes (GNB) algorithms. Empirical analysis carried out using real-time experimental data, such as throughput, jitter, and response time metrics, proved CART to be the best, with 98% prediction accuracy, a processing rate of 5.3 × 10 observations per second, and a training time of 12.4 ms.

2.4. Ensemble and Hybrid Learning Approaches

Ensemble learning techniques enhance detection effectiveness through the fusion of algorithms. Basharat et al. [

23] applied ensemble machine learning techniques to intelligent healthcare systems, with the highest rates of attack detection by AdaBoost classifiers from several models tested. Their extended evaluation framework established standards for ensemble performance in healthcare application-based attack scenarios.

Guo et al. [

32] ran comprehensive testing of ten various learning techniques on the TON_IoT attack dataset, with stacking-ensemble models being the best performers. Their method yielded Matthews Correlation Coefficient scores of 0.9971 for binary classification and 0.9909 for multi-class classification, demonstrating the strong efficacy of ensemble methods in recognizing intricate attack patterns.

The integration of multiple detection paradigms into a single framework has proven efficient for handling diverse threat profiles. Alani [

29] designed IoTProtect, an IDS based on machine learning, with remarkable performance metrics, including a 99.999% attack detection rate, a 0.001% false positive rate, and a 0% false negative rate. The success of the system is due to comprehensive ensemble feature complexity reduction schemes coupled with real-time processing at IoT gateway levels.

Roopak et al. [

38] proposed an intrusion detection system that integrated CNN and LSTM architectures with multi-objective optimization methods. Their system utilized Jumping Gene-adapted NSGA-II algorithms for dimension reduction, achieving an accuracy of 99.03%. Additionally, five-fold cross-validation strategies enabled a drastic reduction in training time.

2.5. Specialized Detection for Healthcare Applications

Healthcare IDS studies have increasingly emphasized merging medical and biometric data sources to improve threat detection performance. Hady et al. [

21] set up robust testbeds for Enhanced Healthcare Monitoring Systems (EHMS), capturing both network traffic and patient biometric data. Their validation against the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 MITM dataset demonstrated the viability of multimodal data fusion for realistic healthcare threat detection scenarios.

Tuteja et al. [

24] investigated logistic regression-based methods for healthcare intrusion detection, integrating LSTM networks for recognizing attack patterns. Their research provided building blocks for integrating patterns of clinical data with network security monitoring, demonstrating the potential for healthcare-specific threat intelligence.

The migration of healthcare systems to cloud-based environments has created the need for specialized security methods. Saif et al. [

19] applied hybrid IDS solutions to IoT-based smart healthcare on AI-based cloud medical servers. Their analysis of six hybrid machine learning methods revealed that Decision Tree methods are optimal for cloud-based healthcare threat detection, setting standards for cloud security in medical settings.

Sophisticated cloud security studies have investigated automated threat response mechanisms. Adebayo et al. [

31] proposed AI-driven intrusion prevention systems using Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) classifiers for real-time IoT network defense. Their system achieved 99.9% accuracy through ensemble feature complexity reduction, demonstrating the potential of autonomous threat mitigation in healthcare cloud environments.

2.6. Emerging Threats and Advanced Detection Techniques

The healthcare industry is under growing pressure from zero-day attacks and changing threat environments. Vishwakarma and Jain [

36] proposed honeypot-based machine learning models for IoT botnet DDoS attack defense. It supports dynamic model updates based on honeypot-collected data, offering features to detect and neutralize unknown attack patterns.

McDermott et al. [

41] designed Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks (BLSTM-RNN) for detecting botnets in home automation systems. Their framework utilized word embedding methods for tokenizing attack packets, exhibiting better long-term performance than regular LSTM methods for detecting multi-vector attacks correlated with Mirai botnets.

Healthcare networks are increasingly coexisting in Industrial IoT (IIoT) environments, requiring targeted security methods. Ramaiah and Rahamathulla [

30] proposed robust network intrusion detection systems for IIoT networks and attained 99.93% detection with Extremely Randomized Trees (ERT) and 99.85% detection with LSTM-based methods using the EdgeIIoT-2021 dataset.

The integration of blockchain and advanced AI methodologies has become a promising area for enhancing the security of key healthcare infrastructure. Current studies have investigated the fusion of federated learning with fog/edge computing frameworks, resulting in substantial improvements in detection accuracy, reduced response times, and increased attack costs for attackers.

The literature review identifies a thorough transformation in healthcare IDS research, from basic signature-based detection to advanced machine learning and deep learning techniques. Recent studies have shown impressive results in detection rates, with various methods achieving more than 99% accuracy across different test scenarios. Nevertheless, the complexity of current healthcare IoT environments and the development of sophisticated multi-vector attacks justify further research in lightweight, adaptive, and user-oriented detection methodologies.

The creation of realistic datasets and standardized testing techniques has dramatically improved the quality and comparability of educational assessments. The availability of complete datasets, such as CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024, enables the realistic testing of IDS performance in various healthcare scenarios.

3. Preliminaries

In designing anomaly-based intrusion detection systems (IDS) for multi-vector intrusion detection in IoT-enabled healthcare facilities, selecting a proper deep learning architecture is crucial. While there are several recurrent neural network (RNN) models, LSTM, Transformers, and Autoencoders have each shown superiority in different domains. These models show significant disadvantages within the context of healthcare facilities with time-sensitive operations. Although powerful in capturing long-range dependencies, LSTM networks consume significant computational resources and require longer training times, which means they are not ideal for quick deployment in healthcare applications where real-time response and resource conservation are priorities. Transformers require extensive computational power because of their self-attention mechanism. Their complexity and susceptibility to catastrophic forgetting can interfere with sustained accuracy and stability in streaming, real-time scenarios common in IoT healthcare data. Although autoencoders have the potential to perform unsupervised anomaly detection, they are prone to overfitting and data loss, which can compromise reliability in critical and sensitive areas, such as medical informatics.

Consequently, the above-mentioned architectures are challenging to manage in resource-limited, latency-critical, and adaptive healthcare networks.

3.1. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU): The Lightweight Solution

GRU is a better alternative because it is simpler to implement, converges faster, and requires less memory than the LSTM and Transformer models. GRU effectively captures sequential dependencies in time series data, solving the vanishing gradient problem and reducing computational overhead. These properties position GRU as an ideal choice for real-time anomaly detection in the healthcare environment, where both speed and accuracy are critical.

Figure 2a shows the architecture of a standard GRU cell containing a reset gate, an update gate, and a candidate state.

Figure 2 (b) illustrates the design of an MGRU cell with an abandoned reset gate.

The baseline GRU cell operates based on two types of gating mechanisms: the reset gate and the update gate, which control information flow and retain practical context over time.

Standard GRU Cell Mathematical Formulation

Let xt be the input vector for the current time step t, and ht-1 be the previous hidden state:

-

Update Gate (zt): This gate determines the amount of the past hidden state to retain for the current hidden state. It is calculated by:

(1)

-

Reset Gate (rt): This gate controls how much of the past hidden state to forget when calculating the candidate hidden state. It is calculated by:

(2)

-

Candidate Activation (): The reset gate will add this new information.:

(3)

-

Hidden State Update (): The new hidden state is a weighted sum of the old hidden state and the candidate hidden state, governed by the update gate:

(4)

where σ is the sigmoid activation function, denotes element-wise multiplication, and W, U, and b are the learnable parameters for each gate.

3.2. Modified GRU Architecture

To further minimize the network for IoT-based healthcare settings, the GRU is simplified by removing the reset gate. This design modification minimizes the parameters and calculations, making the network even lighter and quicker, and widely known as the Modified GRU (MGRU).

MGRU Cell Mathematical Formulation

The MGRU works as follows:

-

Update Gate (zt): Similar to the regular GRU, it regulates the proportion of keeping the past hidden state and integrating new information:

(5)

-

Candidate Activation (): Without a reset gate, the candidate hidden state is calculated directly from the last hidden state:

(6)

-

Hidden State Update (): Calculate the latest hidden state as:

(7)

Eliminating the reset gate simplifies the gating structure of the MGRU, resulting in faster training, reduced computational requirements, and on-device deployability in healthcare IoT applications

4. Dataset Selection and Preparation

The process of building efficient intrusion detection systems for IoT-enabled healthcare infrastructure requires a systematic inspection and the selection of suitable benchmark datasets that accurately reflect modern threat scenarios. This section provides an in-depth assessment of current attack datasets to evaluate their suitability for multi-vector intrusion detection in healthcare IoT networks. The choice factors prioritize datasets with heterogeneous attack vectors, real-world-like traffic patterns, and complete labeling schemes that enable both binary and multi-class classification tasks.

Modern cybersecurity studies have yielded numerous benchmark datasets designed to test intrusion detection systems in various network settings. Nonetheless, the distinct nature of healthcare IoT networks, including resource limitations, communication protocols, and time sensitivity, requires custom datasets that accurately reflect the intricacies of medical device communication and potential attack behavior. This review categorizes existing datasets into healthcare-specific and general IoT datasets, discussing their suitability for training effective multi-vector intrusion detection models.

4.1. Healthcare-Specific Dataset Analysis

The healthcare field presents particular security needs that require specialized datasets to record network traffic and patterns of communication among medical devices. Researchers have created various large-scale healthcare datasets to meet these needs, each with different properties and restrictions for multi-vector DDoS detection.

Initially developed for intensive care unit monitoring, the HiRID dataset is primarily centered on patient physiological data rather than network security-related data. Although applicable to research in medical informatics, HiRID does not encompass the network traffic patterns and attack scenarios necessary to train robust intrusion detection models [

43]. Ahmed et al. [

25] created this dataset, which is a valuable addition to healthcare IoT security research. The ECU-IoHT dataset comprises realistic traffic patterns from health devices, including both benign communications and various types of attacks. However, its drawback is that the diversity of DDoS attack vectors is limited, making it inadequate for extensive multi-vector DDoS detection training.

Designed by Hady et al. [

21], the WUSTL-EHMS-2020 dataset encompasses both network traffic and biometric patient data, providing a comprehensive view of healthcare system communications. It contains scenarios involving Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks and some healthcare-related threat patterns. Although it has a realistic strategy for collecting healthcare data, WUSTL-EHMS-2020 lacks the same range of DDoS attack vectors to train a robust multi-vector detection system. Researchers dedicate the MIT-BIH Arrhythmia Database to cardiac rhythm analysis and arrhythmia detection. Although useful for medical device security studies, it lacks network traffic or DDoS attack patterns, making it less suitable for network-based intrusion detection systems [

44].

The CICIoMT2024 dataset [

15] is a significant contribution towards healthcare IoT security research, tailored to overcome the shortcomings of existing healthcare datasets. The Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity has designed a comprehensive dataset to emulate real IoMT network traffic, utilizing a wide range of communication protocols in healthcare settings. CICIoMT2024 consists of 18 unique attack types carried out against a testbed comprising 40 IoMT devices, with 25 physical and 15 simulated devices. This holistic strategy ensures the real-world simulation of modern healthcare IoT settings, while also providing adequate attack diversity to train robust models.

The data collects traffic from multiple healthcare communication protocols, including Wi-Fi, MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport), and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). This multi-protocol data collection reflects the heterogeneous nature of contemporary healthcare IoT networks, where various devices employ different communication standards according to their individual needs. The CICIoMT2024 dataset classifies the attacks into five main categories: Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), Denial of Service (DoS), Reconnaissance (Recon), MQTT-specific attacks, and spoofing attacks. The robust classification framework facilitates both binary classification (benign or malicious) and fine-grained multi-class identification of attacks.

4.2. General IoT Dataset Evaluation

Emphasizing Industrial IoT settings, the WUSTL-IIOT-2021 dataset has multiple attack scenarios attacking industrial control systems. Although useful for industrial security analysis, the dataset's focus on industrial protocols and attack patterns restricts its direct application to healthcare IoT settings [

45]. As one of the first intrusion detection datasets, the DARPA 1999 dataset set significant research benchmarks for security. Due to its age and being geared towards traditional network environments, it is not adequate for today's IoT security needs, especially in terms of healthcare-specific threats and current communication protocols [

46].

Cybersecurity studies have extensively applied this extensive network security dataset, which contains different types of attacks. Although it comprises DDoS attack traffic, UNSW-NB15 does not provide the detailed categorization of various DDoS attack vectors required for training a multi-vector detection system [

48]. CICIDS2017 and CSE-CIC-IDS2018 are modern intrusion detection datasets that provide comprehensive network attack scenarios with accurate labeling. Although they include DDoS traffic, the datasets target general network environments instead of IoT-specific communication patterns and limitations [

51,

52].

Formulated explicitly to attack research, the CICDDoS2019 dataset includes attack vectors such as Portmap, LDAP, NetBIOS, and volumetric attacks. The rich labeling and diversity of attacks render CICDDoS2019 particularly suitable for multi-vector detection training for DDoS attacks, but it lacks a healthcare-related context [

53]. As a landmark in IoT security research, the CICIoT2023 dataset comprises traffic from 105 IoT devices across 33 distinct attack types, categorized into seven major classes: DDoS, DoS, Reconnaissance, Web-based, Brute Force, Spoofing, and Mirai attacks. The dataset's comprehensive coverage of attacks and simulation of a realistic IoT environment makes it eminently suitable for training robust intrusion detection systems [

14].

The BoT-IoT, NSL-KDD, and N-BaIoT datasets are exemplary contributions to IoT security research, but they have shortcomings in multi-vector attack detection. BoT-IoT focuses solely on botnet behaviors. In contrast, NSL-KDD is an enhanced version of the original KDD dataset, but it lacks modern attack patterns. Additionally, N-BaIoT targets specific IoT device weaknesses rather than overall multi-vector attacks [

4][

4][

50].

4.3. Dataset Selection Methodology

Healthcare IoT settings require considering appropriate datasets for multi-vector intrusion detection. Key conditions include diversity in attack vectors, protocol coverage, quality of labeling, dataset size, and relevance to healthcare IoT contexts, as outlined in

Table 2.

Effective multi-vector intrusion detection requires training datasets that encompass a range of attack types, which can occur in conjunction with or in sequence. The chosen datasets should encompass the representation of Layer 3 (network layer) attacks, such as ICMP floods, Layer 4 (transport layer) attacks, including SYN floods and UDP floods, and Layer 7 (application layer) attacks, like HTTP-based DDoS. IoT networks in healthcare utilize various communication protocols, depending on the device categories and applications. Sampled datasets should reflect traffic across protocols commonly used in healthcare settings, such as regular IP-based communications, MQTT for low-bandwidth device messaging, and Bluetooth for personal health devices.

Strong model training requires high-quality labels that facilitate both binary classification (attack/benign) and fine-grained multi-class classification, allowing for the detection of specific types of attacks. The labeling scheme must be consistent, precise, and exhaustive for all attack scenarios.

Focused on CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 as the main datasets for the development of multi-vector intrusion detection systems based on extensive analysis of accessible datasets against selection criteria, this study:

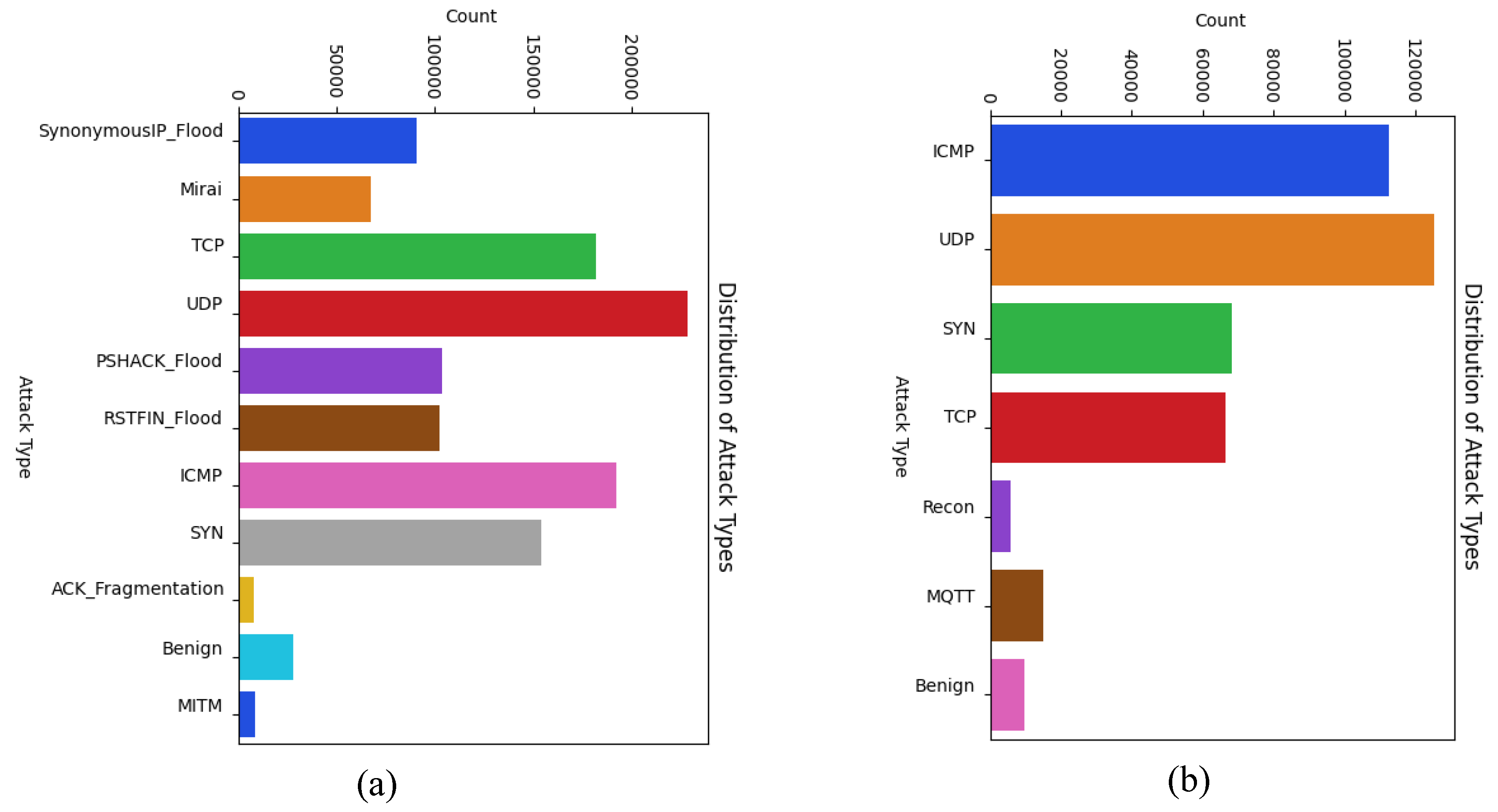

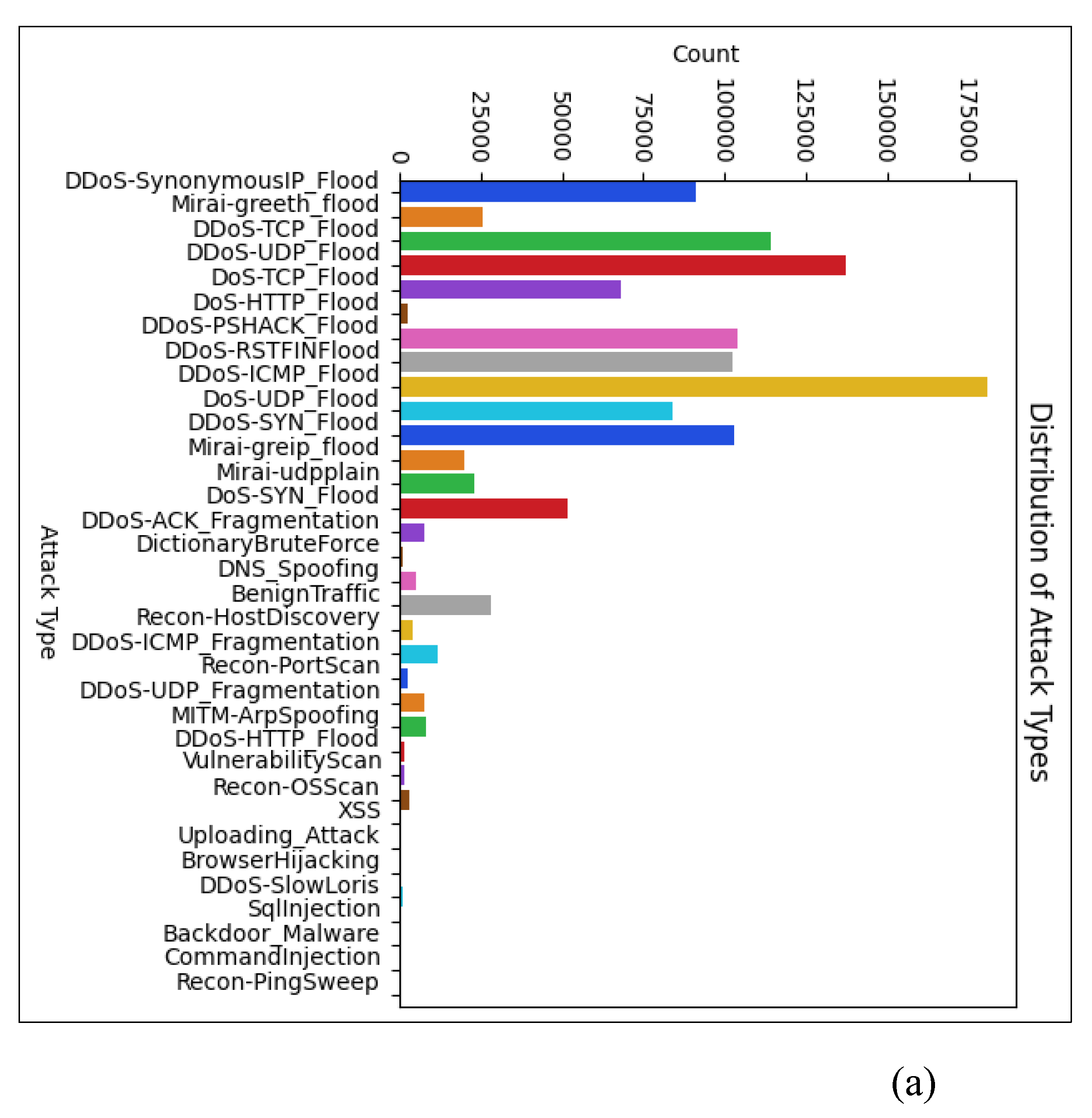

CICIoT2023: The dataset offers rich IoT attack coverage with 33 various attack types from seven classes, including a wide variety of DDoS attack variants, as shown in

Figure 3 (a). The size of the dataset (105 devices) and the diversity of attacks make it suitable for training effective detection models that can handle diverse IoT environments.

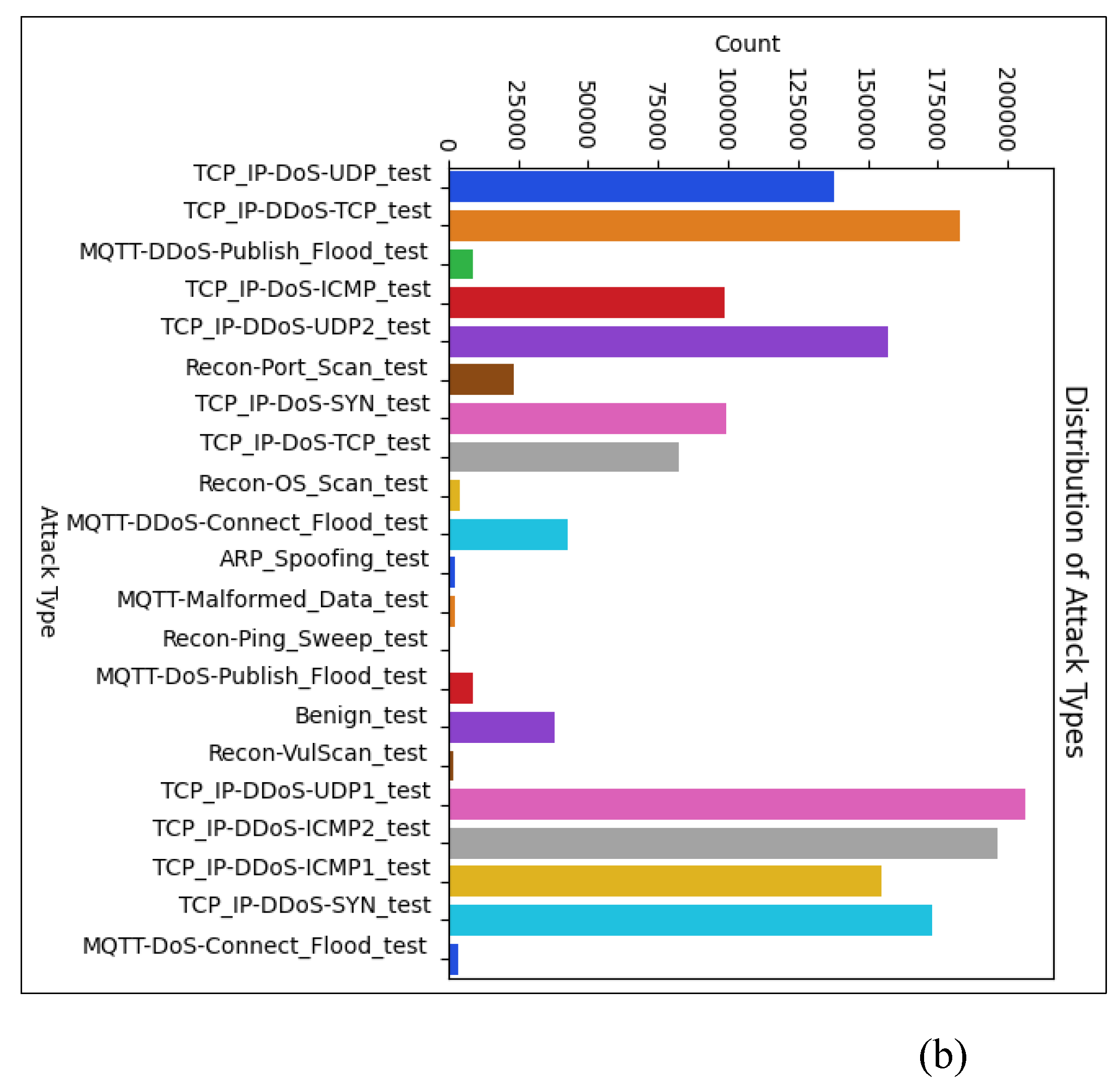

CICIoMT2024: Tailored for research in healthcare IoT security, this dataset meets the distinct needs of medical device networks. Its emphasis on healthcare-pertinent protocols and attack situations creates valuable context for creating healthcare-specific intrusion detection systems. The dataset provides comprehensive IoT attack coverage, encompassing 20 distinct attack types from six classes, including a diverse range of DDoS attack variants, as illustrated in

Figure 3b.

4.4. Attack Label Selection and Categorization

This study examines the most common DDoS attack vectors found in CICIoT2023, considering the comprehensive set of attack types:

Portmap: Exploiting Network File System (NFS) portmapper services for amplification attacks

LDAP: Lightweight Directory Access Protocol amplification attacks

NetBIOS: Network Basic Input/Output System-based DDoS attacks

SlowLoris: Application-layer DDoS attacks targeting web servers

SYN: TCP SYN flood attacks overwhelm connection establishment processes

UDP: User Datagram Protocol flood attacks consume bandwidth and processing resources

ICMP: Internet Control Message Protocol flood attacks

TCP: General TCP-based flooding attacks

HTTP: Hypertext Transfer Protocol-based application layer attacks

The CICIoMT2024 dataset offers healthcare-related attack instances with the following chosen labels used for training of multi-vector intrusion detection:

ICMP: Healthcare device-targeted ICMP flooding attacks

UDP: UDP-based attacks against medical device communications

SYN: SYN flood attacks targeting healthcare service availability

TCP: TCP-based attacks disrupting medical data transmission

MQTT: Message Queuing Telemetry Transport protocol-specific attacks

Recon: Reconnaissance attacks gather intelligence for subsequent attacks

Benign: Normal healthcare IoT traffic patterns

Both datasets contain multiple common attack categories (Benign, SYN, TCP, UDP, ICMP), which facilitate cross-dataset validation and strong model assessment in various IoT settings. The overlap offers prospects of transfer learning and overall performance evaluation.

4.5. Data Preprocessing and Preparation Pipeline

Efficient machine learning model construction requires thorough data preprocessing to achieve optimal training performance and model accuracy. The preprocessing pipeline for CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets involves several phases aimed at addressing data quality issues, optimizing features, and preparing the classification scheme.

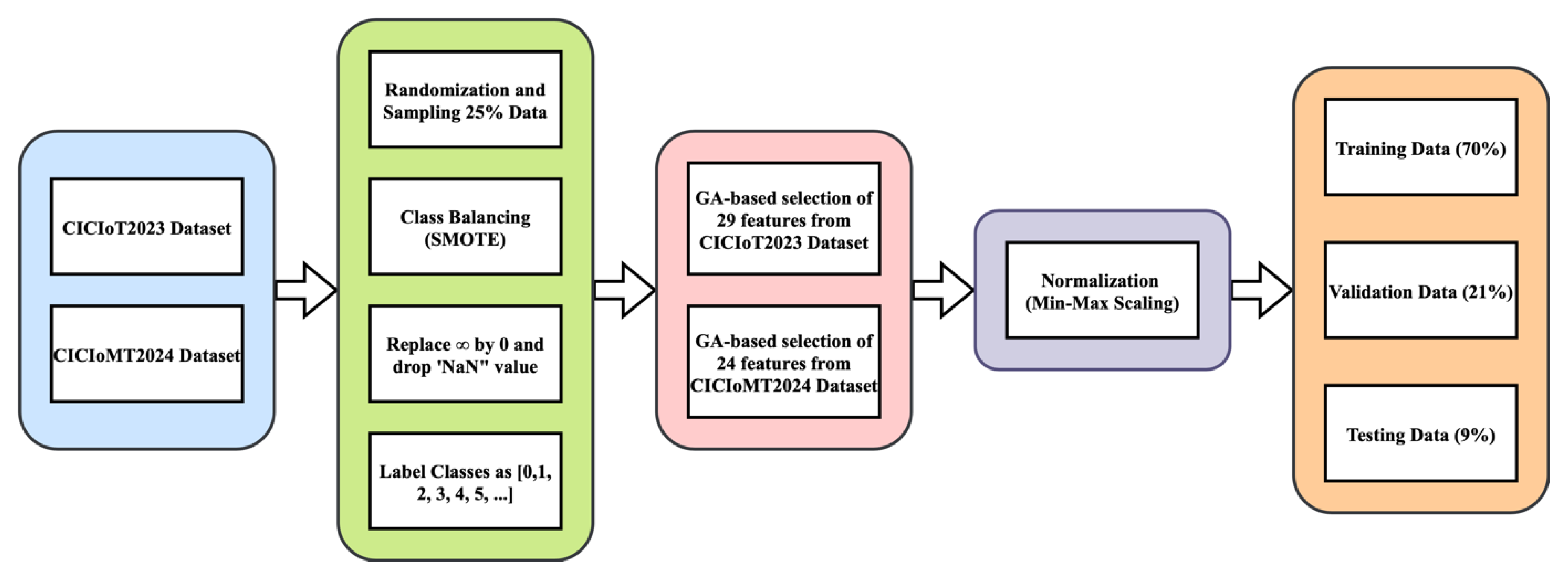

Figure 4 displays the preprocessing stages of the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets.

Network traffic data typically includes missing values because of measurement failures, hardware faults, or communication losses. The preprocessing pipeline detects features with 'NaN' (Not a Number) values and executes respective handling techniques. We impute missing values in categorical features using the mean, preserving the highest frequency category representation. Numerical features having missing values are subject to mean imputation to reduce the effect of outliers on the replaced values. The preprocessing pipeline conducts rigorous data validation checks to detect and resolve inconsistencies in feature values, timestamp ordering, and labels. We use manual verification or automatic repair to mark inconsistent records.

4.5.1. Feature Engineering and Selection

Randomization and Sampling: To prevent bias in model training, the preprocessing pipeline uses randomization methods while sampling the data. Researchers intentionally omitted specific rows to ensure randomization while maintaining a representative sample of all attack types and typical traffic patterns.

Feature Categorization: The attack types in the datasets are classified into distinct attack categories, as shown in

Figure 6, based on their operational similarities and effects on IoT healthcare systems. The classes represent shared characteristics, such as resource exhaustion, information gathering, protocol exploitation, or identity deception, to allow more effective analysis and detection approaches. The classification matches the design of the datasets to support both binary (benign vs. attack) and multi-class (specific attack types) intrusion detection.

Genetic Algorithm-Based Feature Selection: Building on conventional feature selection techniques, this study utilizes genetic algorithm (GA) optimization to select a subset of features. The GA method systematically investigates the feature space and finds the best combination of features that yields maximum classification performance while reducing computational costs, as represented in Algorithm 1.

Figure 5 illustrates the features selected by GA for binary classification and multi-label classification from the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets.

The genetic algorithm implementation employs the following parameters:

Population Size: 10 individuals representing different feature subsets

Selection Method: Tournament selection with a tournament size of 3

Crossover Rate: 0.5 for generating new feature combinations

Mutation Rate: 0.2 for introducing feature variation

Fitness Function: LightGBM model across validation sets

Termination Criteria: 5 generations or convergence threshold achievement

4.5.2. Dataset Balancing and Augmentation

Class Imbalance Assessment: Datasets of real-world network traffic are generally heavily class-imbalanced, with benign traffic far overwhelming attack occurrences. The preprocessing pipeline performs a thorough class distribution analysis to measure the severity of imbalance and determine suitable balancing measures.

| Algorithm 1 Genetic Algorithm for Feature Selection |

Ensure:Training data matrix, labels

Require: Population size P, number of generations G, crossover probability pc, mutation probability pm, tournament size T

Initialize Population

For each individual i = 1 to P, generate a random bitmask

where sj(i) = 1 indicates feature j is selected.

Evaluate Initial Fitness

For each individual s(i):Form reduced dataset

Train a lightweight classifier on (X′,Y).

Compute validation accuracy F(s(i)).

Evolutionary Loop

For generation g = 1 to G:

3.1. Selection (Tournament)

For each of P offspring:

Randomly pick T individuals from the current population.

Parent p := individual with the highest fitness among those T.

3.2.Crossover

Pair up selected parents at random.

For each pair (pa,pb):

With probability pc, choose two crossover points c1 < c2.

Swap bits between c1 and c2 to form two children.

Otherwise, children = exact copies of parents.

3.3. Mutation

For each bit in each child, flip the bit with probability pm.

3.4. Fitness Evaluation

For each new child s:

Compute F(s) as in step 2.

3.5. Elitism & Replacement

Combine the current population and offspring.

Sort all 2P individuals by fitness F.

Keep the top P individuals for the next generation.Return Best Mask

Let

Output the feature index set

|

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE): The pipeline uses SMOTE to introduce synthetic minority class samples for handling class imbalance, effectively increasing their representation as depicted in

Figure 7. It creates new attack samples through interpolation between current attack instances to enhance the model's training on rare attack modes.

5. Proposed Framework

The rapid exponential growth of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices in modern healthcare settings has revolutionized the delivery of medical services while simultaneously introducing unprecedented cybersecurity risks. Interconnected medical devices that span implantable biosensors, wearable health monitors, and more, form extensive attack surfaces that malicious actors can target to launch sophisticated multi-vector intrusion attacks on critical healthcare infrastructure.

The proposed framework addresses the unique security challenges of IoMT environments with a robust, dual-type intrusion detection system designed explicitly for healthcare. This novel solution integrates the computational power of Modified Gated Recurrent Units (MGRU) with a GA-based feature selection approach.

Modern healthcare networks are becoming increasingly vulnerable to advanced attack vectors that exploit the inherent weaknesses in resource-limited medical devices. The high availability and accessibility features of IoMT devices significantly increase the likelihood and potential severity of multi-vector attacks on smart healthcare systems. Such attacks can cause disruptions to critical patient care services, violate sensitive medical information, and even put patients' safety at risk due to service disruptions.

Figure 5.

Features Selected from CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets using GA.

Figure 5.

Features Selected from CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets using GA.

The Internet of Medical Things ecosystem is a highly interconnected system of medical devices, communication infrastructure, and data processing systems that work together to facilitate sophisticated healthcare service delivery. To develop successful security mechanisms that safeguard patient data and maintain service continuity, it is crucial to comprehend the flow of data and patterns of communication within this ecosystem.

The IoMT architecture comprises several layers of interconnected components with specific functions in the healthcare data gathering and processing pipeline. Designers create these devices, gateways, servers, and interfaces to fulfill the varied needs of healthcare stakeholders, as illustrated in

Figure 8.

The IoMT framework integrates advanced implantable devices that track patient physiological parameters continuously and administer therapeutic interventions. These include:

Cardiac Pacemakers: High-end cardiac rhythm management devices that track heart function and offer electrical stimulation to ensure optimal cardiac performance.

Cochlear Implants: Advanced auditory prosthetic devices that translate sound signals into electrical impulses for individuals with profound hearing loss.

Gastric Stimulators: Medical devices that modulate digestive system function by controlled electrical stimulation.

Implantable Biosensors: Real-time monitoring devices that monitor multiple physiological parameters such as glucose, blood pressure, and tissue oxygenation.

Advanced wearable technology provides comprehensive health monitoring capabilities by integrating non-invasive sensors. Primary categories of wearable devices are:

Smart ECG Monitors: Handheld electrocardiogram units that continuously record cardiac electrical activity and identify arrhythmias or other cardiac abnormalities.

Depression Level Monitors: An advanced way to track psychological health-related behavioral patterns, along with physiological markers involved.

Smart Insulin Monitors: Continuous glucose monitoring systems combined with the provision of automatic implantable mechanisms for insulin delivery in patients who have diabetes.

Smart Blood Pressure Monitors: Blood pressure measurement units with automatic capabilities and remote monitoring via wireless connectivity.

Medical devices generate sensor data and forward it to mobile devices, which serve as communication hubs. Smartphones act as intelligent sink devices, collecting information from multiple IoMT sources and securely transmitting it to the healthcare network infrastructure.

The data path for transmission from mobile devices to healthcare servers utilizes standardized network access points that facilitate secure connections, ensure data integrity, and maintain patient confidentiality. The layer employs authentication methods and encryption techniques to safeguard personal medical data in transit.

Data from aggregated IoMT undergoes thorough processing on specialized medical database servers equipped with enhanced data analysis features. These servers apply machine learning methods for pattern analysis, anomaly detection, and knowledge extraction to facilitate the clinical decision-making process.

Analyzed medical data and analytical findings are systematically consolidated into Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems, developing comprehensive patient profiles that incorporate diagnostic data, treatment histories, laboratory results, imaging data, and demographic information. Such integration enables healthcare professionals to have complete patient details, allowing them to make informed clinical decisions.

Figure 6.

Different Attack Categories with Majority and Minority classes for (a) CICIoT2023, and (b) CICIoMT2024 Datasets.

Figure 6.

Different Attack Categories with Majority and Minority classes for (a) CICIoT2023, and (b) CICIoMT2024 Datasets.

5.1. Stakeholder Classification and Alert Mechanisms

Technical users of the IoMT framework are primarily cybersecurity experts responsible for detection, analysis, and threat mitigation. Cybersecurity experts require precise information on attack vectors to implement effective countermeasures and maintain a robust system security posture.

Technical users benefit from fine-grained threat intelligence that includes detailed attack classifications, source detection, attack vector breakdowns, and suggested mitigation steps. The designed framework delivers holistic, multi-class classification outputs that facilitate technical teams' comprehension of attack properties and the deployment of specialized defense strategies.

Non-technical stakeholders include different healthcare professionals whose primary concern is patient care over cybersecurity activities. These stakeholders include:

Hospital Management: Management staff are in charge of operational management and resource allocation decisions.

Medical Physicians: Clinicians who need continued access to patient data and medical systems.

Nursing Staff: Frontline medical caregivers who rely on stable IoMT systems for patient monitoring and care provision.

Patient Caregivers: Support staff involved in patient care activities and health status monitoring.

Emergency Services: Emergency response teams need immediate access to patient information during emergency responses.

Non-technical users receive straightforward binary classification alerts of the existence or non-existence of security threats without necessitating exhaustive technical analysis. This method enables healthcare professionals to quickly grasp the security status without being distracted from patient care tasks.

5.2. Proposed Intrusion Detection Framework Architecture

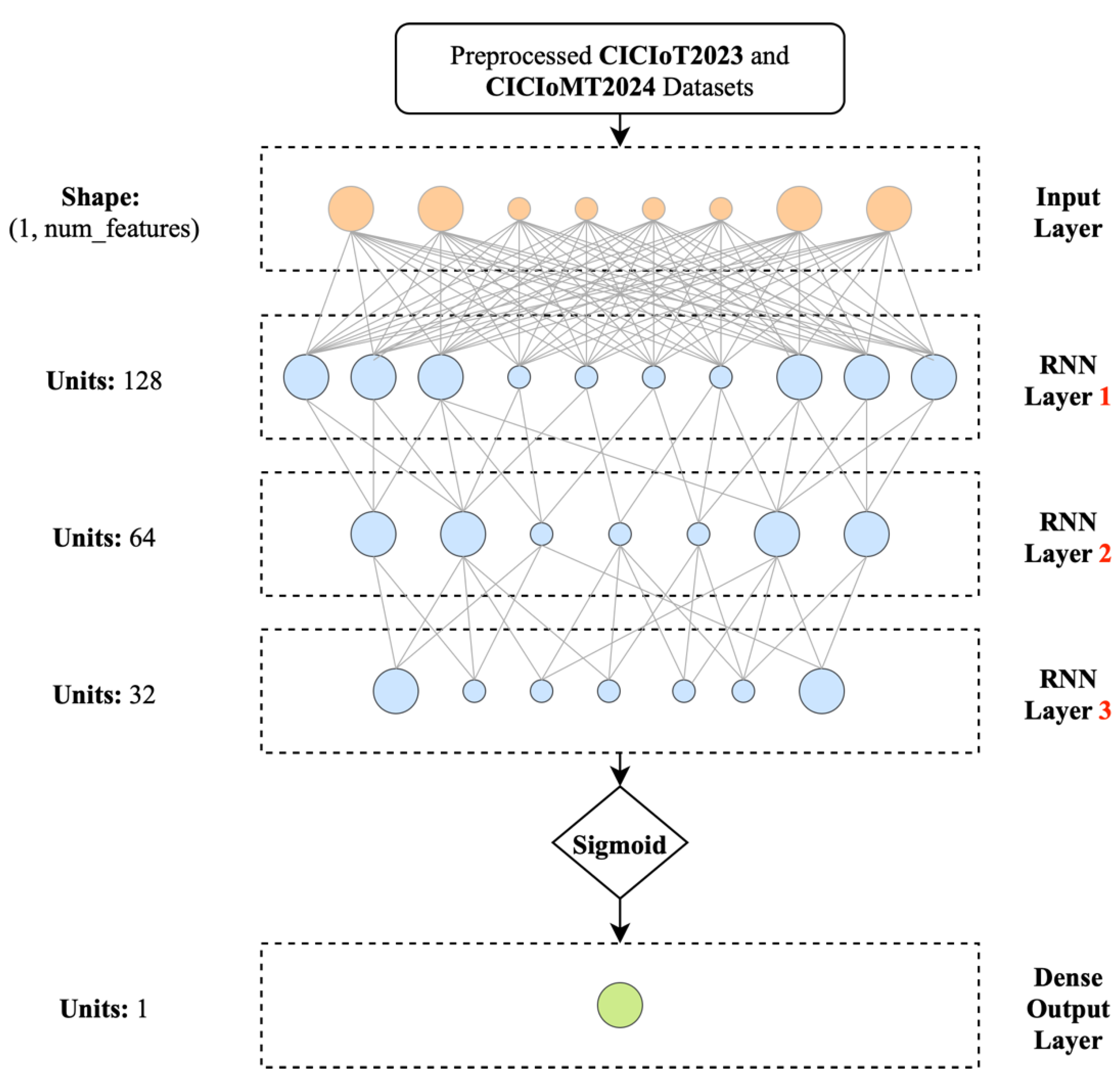

The proposed intrusion detection system employs a two-instance structure that addresses the diverse information needs of healthcare stakeholders without compromising on computational effectiveness in resource-limited IoMT contexts. This solution integrates two classification instances: a Binary Label Classifier (BLC) to serve non-technical users and a Multi-Label Classifier (MLC) for technical users. The design approach acknowledges that adequate security in healthcare settings requires customized information delivery mechanisms, taking into account users' levels of expertise and operational roles.

5.2.1. Binary Label Classifier (BLC) Design

The Binary Label Classifier focuses on quick threat detection through simplified binary classification, identifying benign network traffic and malicious attack patterns. The method is suited for non-technical healthcare practitioners who need instant threat awareness without technical complexity.

The BLC utilizes optimized Modified Gated Recurrent Units, specifically designed for binary classification tasks in healthcare IoT networks.

Figure 9 depicts the architecture of the proposed BLC. The MGRU architecture processes sequential network traffic information to detect patterns of attacks while preserving low computational overhead levels appropriate for real-time healthcare use cases.

5.2.2. Multi-Label Classifier (MLC) Design

The Multi-Label Classifier provides in-depth identification and classification of attack vectors for cybersecurity experts. The method conducts granular threat analysis of identified threats, classifying attacks by targeted vector types, attack patterns, and threat patterns.

The MLC utilizes advanced MGRU settings tailored for multi-class classification processes in multiple categories of attacks.

Figure 10 depicts the architecture of the proposed MLC. The improved architecture handles complex network traffic patterns to differentiate between numerous attack categories, including DDoS attack variations, reconnaissance actions, and protocol-specific attacks.

5.3. MGRU-Based Deep Learning Implementation

5.3.1. Modified GRU Architecture Optimization

We selected Modified Gated Recurrent Units based on the distinct needs of IoMT environments, where limited computational budgets require real-time processing. MGRU architecture eliminates unnecessary computational complexity while maintaining efficient sequence modeling capabilities for network traffic analysis.

Network traffic in IoMT settings exhibits sequential features, necessitating dedicated processing strategies that can identify temporal relationships and detect patterns of attack development. The MGRU architecture is particularly efficient at handling sequential data streams with low memory usage and high-speed inference.

The framework architecture supports varying scales of networks, ranging from small practices to large healthcare systems, through modular MGRU implementations. This scalability provides effective threat detection across a wide range of healthcare environments while maintaining consistent performance characteristics.

5.3.2. Training and Optimization Methodology

The MGRU models undergo thorough training using the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets, which contain real-world attack scenarios and threat models specific to the healthcare sector. This method of training the model ensures that the framework can effectively identify today's multi-vector attacks on healthcare infrastructure. The comprehensive training and evaluation of BLC and MLC are represented in Algorithm 2 and Algorithm 3, respectively.

The system employs a feature selection method using GA to improve MGRU performance according to healthcare-specific network traffic profiles. Ongoing optimization procedures enable MGRU models to maintain high detection efficiency and meet the real-time performance requirements necessary for medical care applications. Optimization involves hyperparameter adjustment, model compression, and acceleration of inference.

6. Experimental Results and Performance Analysis

This section presents the results and performance of the suggested intrusion detection system. The system consists of two independent Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) instances, which we refer to as BLC and MLC. Both instances were created in Python using the Keras library in Google Colab, an environment that offers a neural network framework based on TensorFlow.

| Algorithm 2 Training and Evaluation of BLC |

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

15:

16:

17:

18:

19:

20:

21:

22:

23:

24:

25:

26:

27:

28:

29:

|

Inputs: Datasets, Batch size B, Number of epochs E, Learning rate Lr

Split Dataset into training set X_train, validation set X_val, and test set X_test

Preprocess features:

for each X in X_train, X_val, X_test do

X_norm ← normalize(X)

end for

Define model:

Input → mGRU(128, return_sequences=True)

→ mGRU(64, return_sequences=True)

→ mGRU(32, return_sequences=False)

→ Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')

Compile model with:

optimizer = Adam(learning_rate=Lr)

loss = BinaryCrossentropy()

metrics = [Accuracy()]

Train model:

history ← model.fit(

x = X_train.features,

y = X_train.labels,

batch_size = B,

epochs = E,

validation_data = (X_val.features, X_val.labels)

)

Evaluate model on X_test:

results ← model.evaluate(X_test.features, X_test.labels)

Print test loss and metrics from results |

| Algorithm 3 Training and Evaluation of MLC |

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

15:

16:

17:

18:

19:

20:

21:

22:

23:

24:

25:

26:

27:

28:

29:

|

Inputs: Datasets, Batch size B, Number of epochs E, Learning rate Lr

Split Dataset into training set X_train, validation set X_val, and test set X_test

Preprocess features:

for each X in X_train, X_val, X_test do

X_norm ← normalize(X)

end for

Define model:

Input → mGRU(128, return_sequences=True)

→ mGRU(64, return_sequences=True)

→ mGRU(32, return_sequences=False)

→ Dense(C, activation='softmax')

Compile model with:

optimizer = Adam(learning_rate=Lr)

loss = SparseCategoricalCrossentropy()

metrics = [Accuracy()]

Train model:

history ← model.fit(

x = X_train.features,

y = X_train.labels,

batch_size = B,

epochs = E,

validation_data = (X_val.features, X_val.labels)

)

Evaluate model on X_test:

results ← model.evaluate(X_test.features, X_test.labels)

Print test loss and metrics from results |

The center of both BLC and MLC models is a latent layer made up of three stacked layers of MGRU, whose purpose is to detect dependencies in the input data. Specific hyperparameters regulate the learning, which are broad settings that affect the way the model learns. Optimal values for these parameters, under which the model performed best, are recorded in

Table 3.

For both data sets, the data was divided into training, validation, and testing sets to train, validate, and test the models. In particular, 70% of the data was applied for training, 20% for validation, and the remaining 10% was for testing the ultimate performance of the BLC and MLC models. The subsequent sections explain how the models performed on this 10% test dataset, demonstrating their effectiveness and efficiency in detecting attacks, and provide more specific results. We provide an analysis of several key performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, Sensitivity, Specificity, etc.

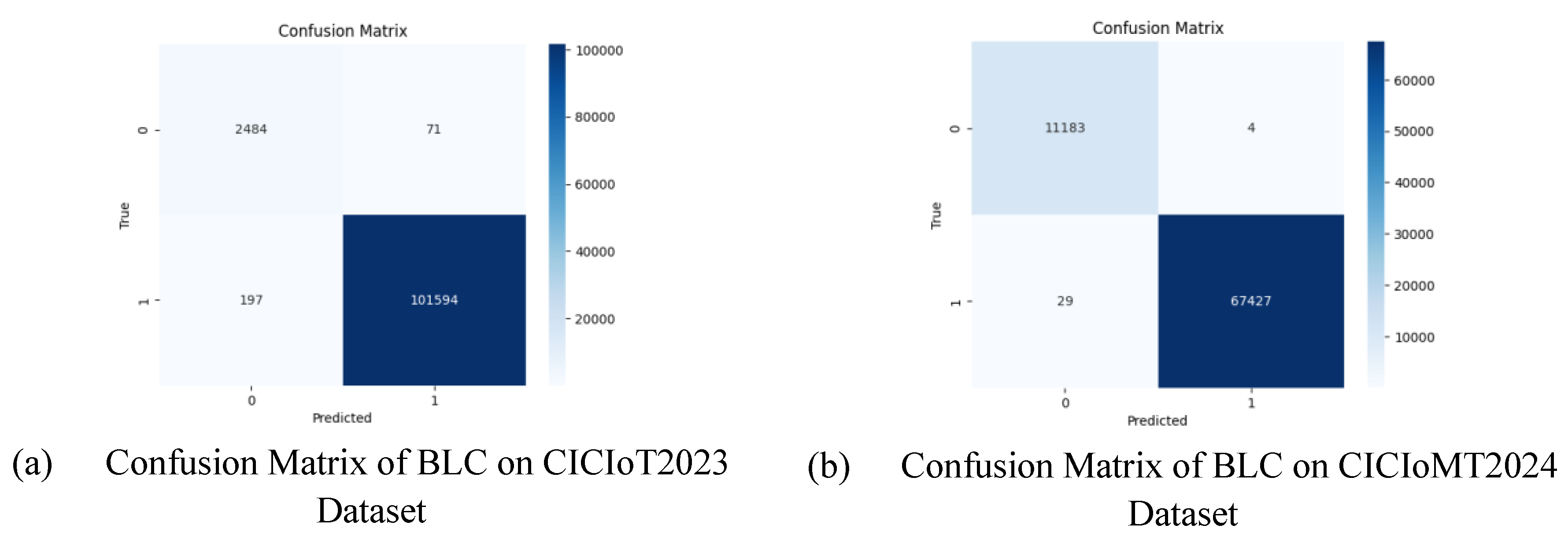

6.1. Results of BLC

This subsection compares the performance of the BLC model on the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets. We provide an analysis of some important measures on both the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets.

Figure 11a demonstrates the BLC model's training and testing accuracy and loss curves on the CICIoT2023 dataset.

Figure 11b shows the corresponding accuracy and loss curves for the CICIoMT2024 dataset.

Figure 12a is the confusion matrix of BLC's performance on the CICIoT2023 dataset, and

Figure 12b is that of the CICIoMT2024 dataset. We tabulated the performance measures extracted from these matrices in

Table 4.

6.2. Results of MLC

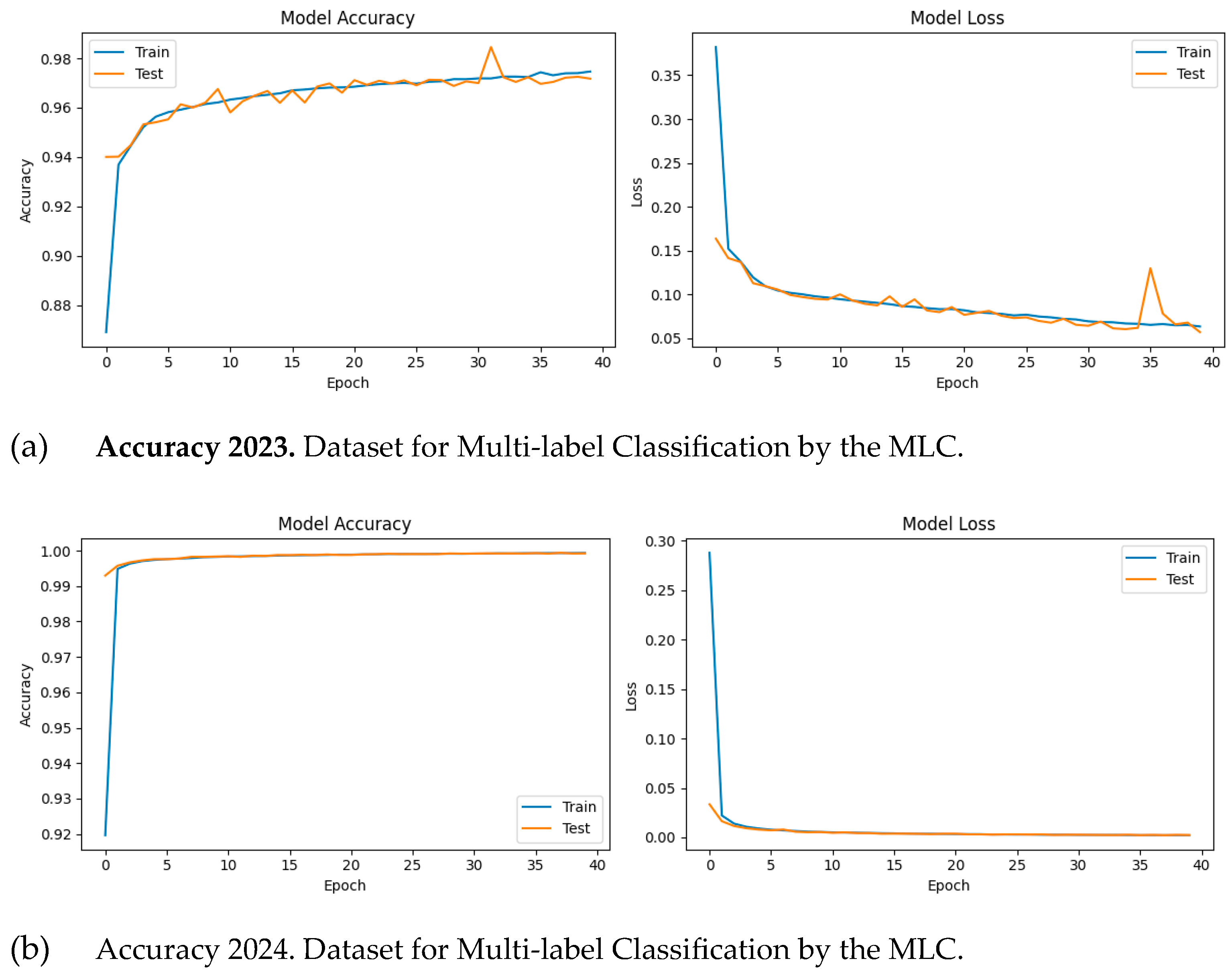

This subsection shows a corresponding performance measurement for the MLC model on both the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 data, with an emphasis on accuracy, loss, and confusion matrices.

Figure 13a illustrates the MLC model's training and test accuracy and loss plots on the CICIoT2023 dataset.

Figure 13b illustrates the accuracy and loss plots for the CICIoMT2024 dataset.

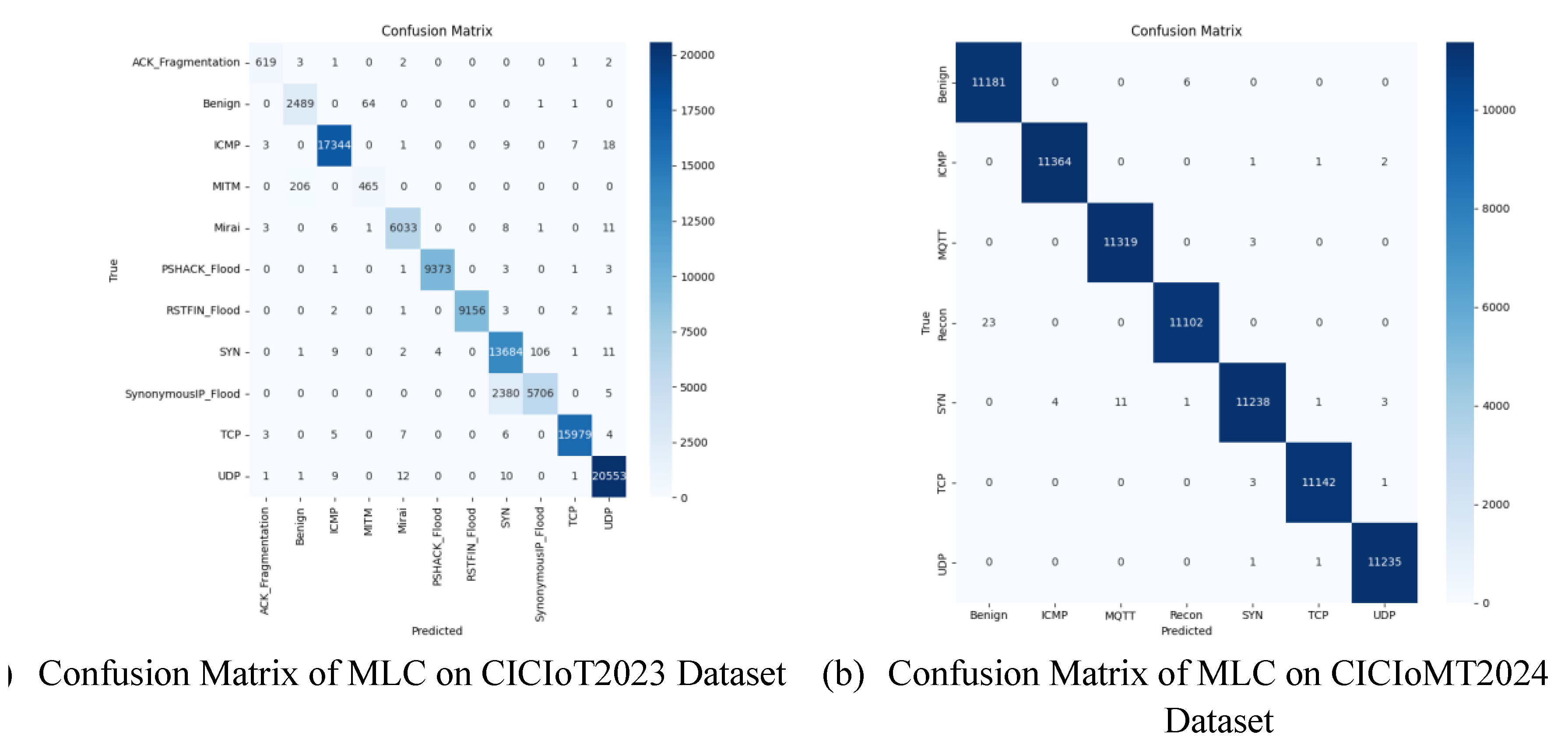

Figure 14a depicts the confusion matrix for the MLC model for the CICIoT2023 dataset, and

Figure 14b similarly illustrates the confusion matrix for the CICIoMT2024 dataset, with resulting performance metrics tabulated in

Table 5.

7. Discussion

Implications: This study presents a novel, lightweight, and user-specific approach to detecting multi-vector DDoS attacks in IoT-enabled healthcare systems. The methodology employs two independent deep-learning-based intrusion detection systems (IDS), each with hidden layers constructed using a modified GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) architecture.Evaluations: We compared the performance of suggested IDS instances (BLC and MLC) to the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets. After training, the BLC model categorizes incoming IoMT traffic as 'Attack' or 'Benign.' The MLC model can categorize traffic as 'Benign' or a specific type of attack, such as 'ICMP,' 'UDP,' 'SYN,' 'TCP,' 'MQTT,' and flood and fragmentation attacks.

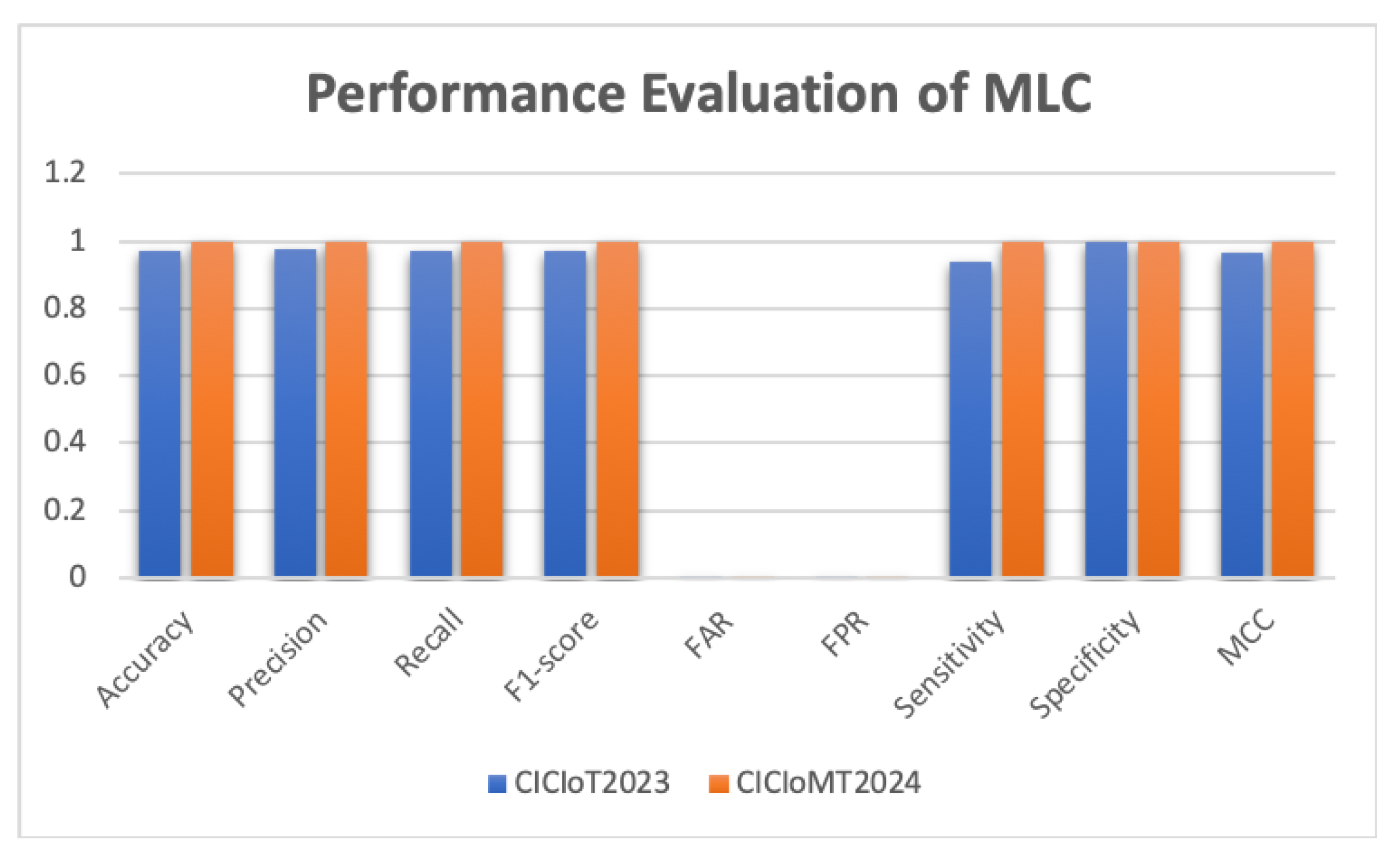

To highlight the efficiency and creativity of our models, we compared their performance to existing intrusion detection methods. As shown in

Table 6, our proposed IDS instance (MLC) outperformed state-of-the-art mechanisms in multi-class classification and multi-vector attack detection in four key metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

Figure 15 depicts the behavior of the BLC model on the two datasets, which perform similarly on key measures.

Figure 16 displays the behavior of the MLC model, which, despite varied behavior on the two datasets, performed better when trained on the CICIoMT2024 dataset than the CICIoT2023 dataset.

Complexity Analysis

Here, we analyze the complexity of our IDS instance on our stacked MGRU layers. We compare them based on several measures: model size, training and testing time, accuracy, loss, and detection time.

Table 7 explains the comparison of these models on the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets. This research indicated that the IDS instances based on our stacked MGRU layers always exhibited better performance metrics.

However, applying deep learning models in real-time healthcare systems presents several challenges, including latency, hardware and software requirements, the need for frequent updates, and the difficulty in collating detection outcomes from different IoT devices to detect multi-vector DDoS attacks. Since our models utilize lightweight mGRU layers, they are easier to deploy in real-time, enabling fast attack detection with reasonable complexity. In the future, we plan to implement a lightweight blockchain framework that will process collaborative detection outcomes across multiple mobile devices, enabling even quicker responses for healthcare application users.

Limitations: Although our framework exhibits unique and efficient performance, we found a few primary limitations:

Real-Time Data: In the future, we will construct a testbed to monitor real-time IoT healthcare traffic through multiple medical sensors and wearable devices.

Authentication: This study assumes that all IoMT devices in an IoT environment are authenticated. Hence, it does not cover authentication and identification schemes. We aim to develop a lightweight authentication protocol for IoT-based healthcare devices based on Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD).

8. Conclusions and Future Work

The study successfully designed and tested a lightweight multi-vector DDoS detection framework directly tailored for IoMT-based healthcare systems. We have demonstrated that we can achieve high-performance intrusion detection without the heavy computational cost of traditional deep learning models by utilizing a new MGRU architecture and a genetic algorithm-based feature selection approach. The dual-classifier technique (BLC and MLC) satisfies the key requirement of user-centric threat intelligence, supporting both healthcare professionals with simplified detection and cybersecurity teams with deep insights. Our experimental results, which include a detailed analysis of the CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 datasets, validate that our proposed mechanism outperforms current mechanisms and is deployable in real-time scenarios. The analysis of complexity also highlights the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the framework, opening the door for its implementation in practical time-sensitive healthcare environments.

Although this study has made notable contributions, some limitations provide the path for future research. One key area for improvement is the development of a dedicated testbed to collect and process real-time IoT healthcare traffic from diverse medical sensors and wearable devices. It would enable more realistic validation and testing. Moreover, the current research assumes that the IoT environment has authenticated IoMT devices; hence, future research will aim to develop a lightweight authentication scheme on top of Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) to strengthen the overall security level of the framework. Lastly, to address the challenge of cooperative attack detection across multiple devices, we plan to develop a lightweight blockchain framework. It would enable secure and efficient processing of collaborative detection outcomes, ultimately providing a quicker response time and higher resilience against advanced multi-vector attacks in healthcare applications.

Author Contributions

Author 1 has experimented and written the complete manuscript. Author 2 has reviewed the manuscript and suggested modifications and changes for further improvements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial or non-financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ul, I.; Bin, M.; Asif, M.; Ullah, R. DoS/DDoS Detection for E-Healthcare in Internet of Things. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumari, B.; Ali, A.; Yadav, R.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Sharma, K.K.; Hajela, K.; Singh, G.K. Mobile technology. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzamesi, L.; Elsayed, N. A Review on the Security Vulnerabilities of the IoMT Against Malware Attacks and DDoS. 2025 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 01–08.

- Elsayed, N.; Dzamesi, L.; ElSayed, Z.; Ozer, M. Extreme Learning Machine-Based System for DDoS Attacks Detections on IoMT Devices. arXiv.org. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.05132.

- Pakmehr, A.; Aßmuth, A.; Taheri, N.; Ghaffari, A. DDoS attack detection techniques in IoT networks: a survey. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 14637–14668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguru, A.; Erukala, S. OTI-IoT: A Blockchain-based Operational Threat Intelligence Framework for Multi-vector DDoS Attacks. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2024, 24, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiramasundari, S.; Ramaswamy, V. Distributed denial-of-service (DDOS) attack detection using supervised machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.I.; El Reheem, E.A.; Guirguis, S.K. An entropy and machine learning based approach for DDoS attacks detection in software defined networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. N. K. Intrusion Detection System Using Gated Recurrent Neural Network. 618, vol. 10, no. 01, pp. 1–8, May 2024.

- Kumar, D.; Pateriya, R.; Gupta, R.K.; Dehalwar, V.; Sharma, A. DDoS Detection using Deep Learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 218, 2420–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasongo, S.M.; Sun, Y. A Deep Gated Recurrent Unit based model for wireless intrusion detection system. ICT Express 2021, 7, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D. Choosing an electronic health records system: professional liability considerations. 2011, 8, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Agarap, A.F.M. A Neural Network Architecture Combining Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) for Intrusion Detection in Network Traffic Data. In Proceedings of the 2018 10th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing, Macau, China, 26–28 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A Real-Time Dataset and Benchmark for Large-Scale Attacks in IoT Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, S.; Neto, E.C.P.; Ferreira, R.; Molokwu, R.C.; Sadeghi, S.; Ghorbani, A. CiCIoMT2024: Attack Vectors in Healthcare Devices-A Multi-Protocol Dataset for Assessing IoMT Device Security. Elsevier BV, 2024. Accessed: Aug. 04, 2025. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- Maseno, E.M.; Wang, Z. Hybrid wrapper feature selection method based on genetic algorithm and extreme learning machine for intrusion detection. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoson, E.S.; Abbass, O. Detecting Distributed Denial of Service Attacks using Machine Learning Models. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaar, M.A.; Samiayya, D.; Vincent, P.M.D.R.; Srinivasan, K.; Chang, C.-Y.; Ganesh, H. A Hybrid Framework for Intrusion Detection in Healthcare Systems Using Deep Learning. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 9, 824898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, S.; Das, P.; Biswas, S.; Khari, M.; Shanmuganathan, V. HIIDS: Hybrid intelligent intrusion detection system empowered with machine learning and metaheuristic algorithms for application in IoT based healthcare. Microprocess. Microsystems 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K. Improving intrusion detection in cloud-based healthcare using neural network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2023, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hady, A.A.; Ghubaish, A.; Salman, T.; Unal, D.; Jain, R. Intrusion Detection System for Healthcare Systems Using Medical and Network Data: A Comparison Study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 106576–106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwendi, C.; Anajemba, J.H.; Biamba, C.; Ngabo, D. Security of Things Intrusion Detection System for Smart Healthcare. Electronics 2021, 10, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharat, A.; Bin Mohamad, M.M.; Khan, A. Machine Learning Techniques for Intrusion Detection in Smart Healthcare Systems: A Comparative Analysis. 2022 4th International Conference on Smart Sensors and Application (ICSSA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MalaysiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 29–33.

- Tuteja, A.; Matta, P.; Sharma, S.; Nandan, K.; Gautam, P. Intrusion Detection in Health Care System: A logistic Regression Approach. 2022 5th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1794–1799.

- Ahmed, M.; Byreddy, S.; Nutakki, A.; Sikos, L.F.; Haskell-Dowland, P. ECU-IoHT: A dataset for analyzing cyberattacks in Internet of Health Things. Ad Hoc Networks 2021, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dina, A.S.; Siddique, A.; Manivannan, D. A deep learning approach for intrusion detection in Internet of Things using focal loss function. Internet Things 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, A.F.; Alshargabi, A.A. Using Deep Learning Technique to Protect Internet Network from Intrusion in IoT Environment. 2022 2nd International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, YemenDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Ariffin, S.H.S.; Mustaffa, N.H.; Dewanta, F.; Hamzah, I.W.; Baharudin, M.A.; Wahab, N.H.A. Hybrid Feature Selection Based Lightweight Network Intrusion Detection System for MQTT Protocol. 2023 15th International Conference on Software, Knowledge, Information Management and Applications (SKIMA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MalaysiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 226–230.

- Alani, M.M. IoTProtect: A Machine-Learning Based IoT Intrusion Detection System. 2022 6th International Conference on Cryptography, Security and Privacy (CSP). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 61–65.

- Ramaiah, M.; Rahamathulla, M.Y. Securing the Industrial IoT: A Novel Network Intrusion Detection Models. 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence For Internet of Things (AIIoT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Adebayo, P.O.; Abdulahi, M.J.; Lawrence, O.M.; Ibrahim, Y.A.; Faki, S.A.; Hassan, B.A. An Artificial Intelligence-based Ensemble Technique for Intrusion Detection and Prevention in IoT Systems. 2024 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Driving Sustainable Development Goals (SEB4SDG). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, NigeriaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Guo, G.; Pan, X.; Liu, H.; Li, F.; Pei, L.; Hu, K. An IoT Intrusion Detection System Based on TON IoT Network Dataset. 2023 IEEE 13th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 0333–0338.

- Ma, R.; Wang, Q.; Bu, X.; Chen, X. Real-Time Detection of DDoS Attacks Based on Random Forest in SDN. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, Z.A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Latif, S.; Aslam, S.; Mujlid, H.; Adil, M.; Najam, Z. Effective and Efficient DDoS Attack Detection Using Deep Learning Algorithm, Multi-Layer Perceptron. Futur. Internet 2023, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lyu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lyu, X. FLEAM: A Federated Learning Empowered Architecture to Mitigate DDoS in Industrial IoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2021, 18, 4059–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, R.; Jain, A.K. A Honeypot with Machine Learning based Detection Framework for defending IoT based Botnet DDoS Attacks. 2019 3rd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1019–1024.

- Zeeshan, M.; Riaz, Q.; Bilal, M.A.; Shahzad, M.K.; Jabeen, H.; Haider, S.A.; Rahim, A. Protocol-Based Deep Intrusion Detection for DoS and DDoS Attacks Using UNSW-NB15 and Bot-IoT Data-Sets. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 2269–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopak, M.; Tian, G.Y.; Chambers, J. An Intrusion Detection System Against DDoS Attacks in IoT Networks. 2020 10th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 0562–0567.

- Jia, Y.; Zhong, F.; Alrawais, A.; Gong, B.; Cheng, X. FlowGuard: An Intelligent Edge Defense Mechanism Against IoT DDoS Attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9552–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangodoyin, A.O.; Akinsolu, M.O.; Pillai, P.; Grout, V. Detection and Classification of DDoS Flooding Attacks on Software-Defined Networks: A Case Study for the Application of Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 122495–122508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.D.; Majdani, F.; Petrovski, A.V. Botnet Detection in the Internet of Things using Deep Learning Approaches. 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BrazilDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–8.

- Ali, M.; Saleem, Y.; Hina, S.; Shah, G.A. DDoSViT: IoT DDoS attack detection for fortifying firmware Over-The-Air (OTA) updates using vision transformer. Internet Things 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Faltys et al., "HiRID, a high time-resolution ICU dataset." [Online]. Available: https://physionet.org/content/hirid/1.1/.

- Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.N.; Glass, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ivanov, P.C.; Mark, R.G.; Mietus, J.E.; Moody, G.B.; Peng, C.-K.; Stanley, H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a New Research Resource for Complex Physiologic Signals. Circulation 2000, 101, E215–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WUSTL-IIOT-2021 Dataset for IIoT Cybersecurity Research." [Online]. Available: http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/iiot2/index.

- Thomas, C.; Sharma, V.; Balakrishnan, N.; Dasarathy, B.V. Usefulness of DARPA dataset for intrusion detection system evaluation. SPIE Defense and Security Symposium. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Koroniotis, N.; Moustafa, N.; Sitnikova, E.; Turnbull, B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the Internet of Things for network forensic analytics: Bot-IoT dataset. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N. and J. Slay. UNSW-NB15: a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). in 2015 military communications and information systems conference (MilCIS). 2015. IEEE.

- Bala, R.; Nagpal, R. A REVIEW ON KDD CUP99 AND NSL-KDD DATASET. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 2019, 10, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-BaIoT—Network-Based Detection of IoT Botnet Attacks Using Deep Autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniabudi; Stiawan, D. ; Darmawijoyo; Bin Idris, M.Y.; Bamhdi, A.M.; Budiarto, R. CICIDS-2017 Dataset Feature Analysis With Information Gain for Anomaly Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 132911–132921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leevy, J.L.; Hancock, J.; Zuech, R.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Detecting cybersecurity attacks across different network features and learners. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, AI. H.; Lashkari, SA.H. ; Hakak, and AS. A.; Ghorbani, “A.A. Developing Realistic Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attack Dataset and Taxonomy,” in 2019 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST), Oct. 2019, pp. 1––8. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Abbas, S.G.; Husnain, M.; Fayyaz, U.U.; Shahzad, F.; Shah, G.A. IoT DoS and DDoS Attack Detection using ResNet. 2020 IEEE 23rd International Multitopic Conference (INMIC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, PakistanDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Ravi, N.; Shalinie, S.M. Learning-Driven Detection and Mitigation of DDoS Attack in IoT via SDN-Cloud Architecture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 3559–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Su, L.; Lu, Z. DeepGFL: Deep Feature Learning via Graph for Attack Detection on Flow-Based Network Traffic. MILCOM 2018 - IEEE Military Communications Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 579–584.

- Roopak, M.; Tian, G.Y.; Chambers, J. Deep Learning Models for Cyber Security in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 7–9 January 2019; pp. 0452–0457. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

A Visualization of Multi-vector DDoS Attacks in an Internet of Things Environment.

Figure 1.

A Visualization of Multi-vector DDoS Attacks in an Internet of Things Environment.

Figure 2.

Standard GRU and Modified GRU Architecture.

Figure 2.

Standard GRU and Modified GRU Architecture.

Figure 3.

Different Attack Types in (a) CICIoT2023, and (b) CICIoMT2024.

Figure 3.

Different Attack Types in (a) CICIoT2023, and (b) CICIoMT2024.

Figure 4.

A Visualisation of Preprocessing Steps of CICIoT2023 and CICIoMT2024 Datasets.

Figure 4.