Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Subject and Methods

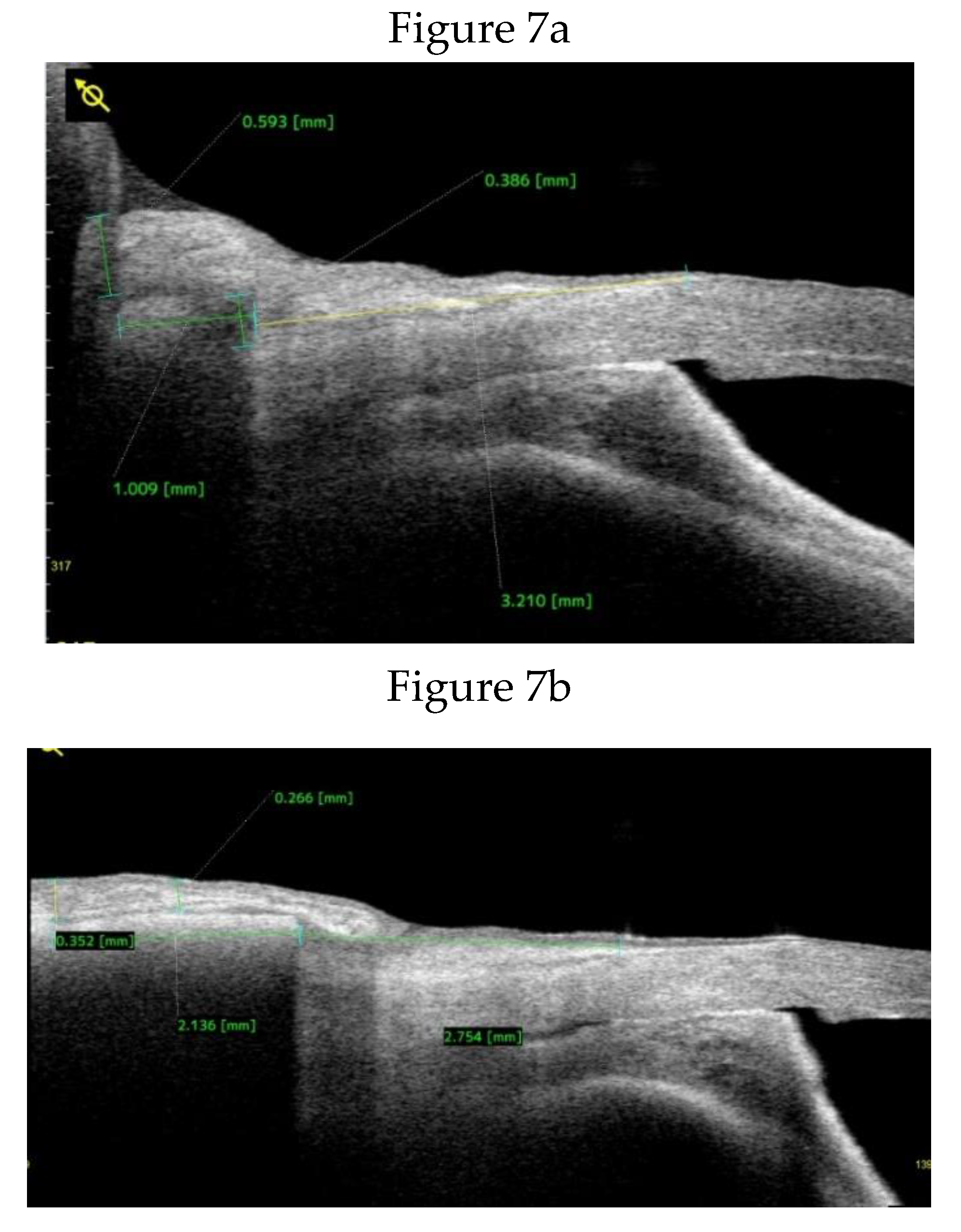

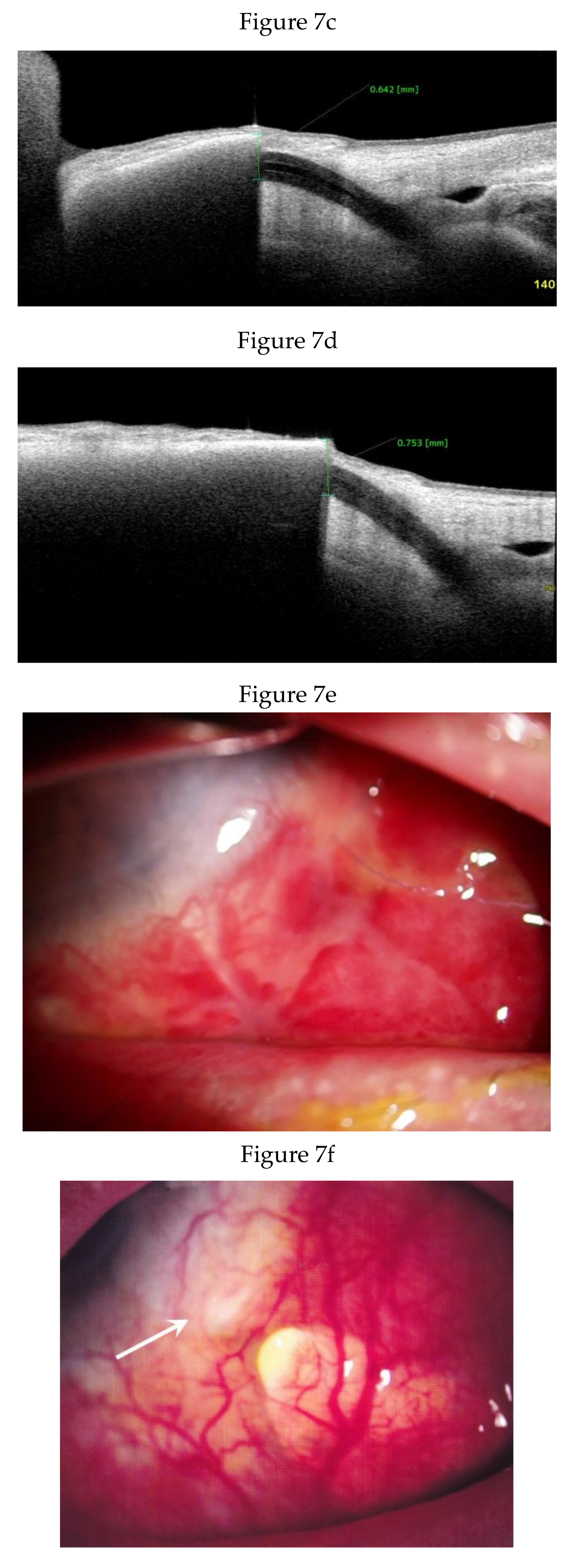

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography (AS-OCT) Evaluation.

Statistical Analysis

Surgical Techniques:

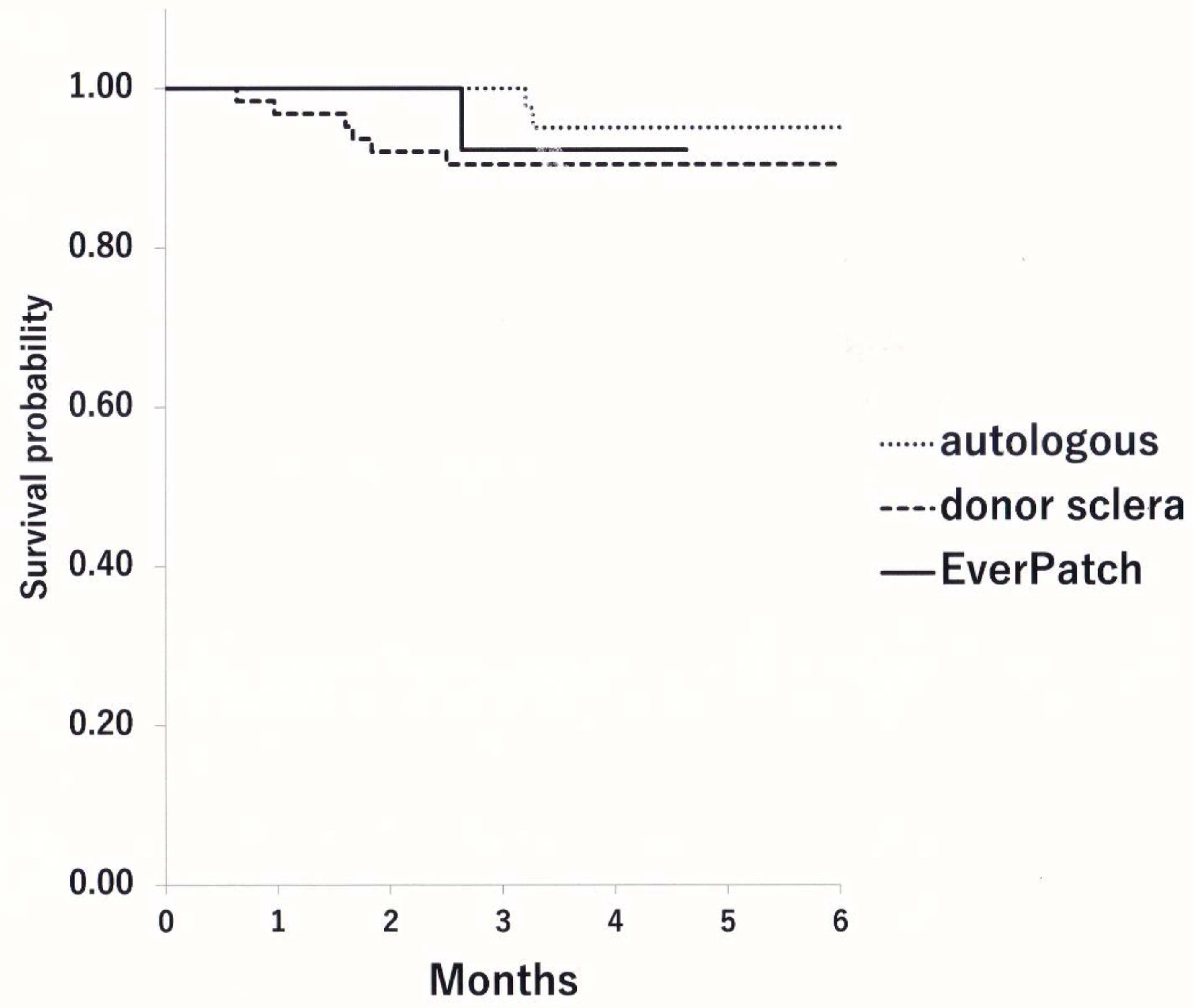

Results

Clinical Course and Conjunctival Thickness in a Representative Case

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbas, Y.B.; Alagoz, N.; Sari, C.; Altan, C.; Yasar, T. Evaluation of pericardium patch graft thickness in patients with Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation: an anterior segment OCT study. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2024, 68, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luna, R.A.; Moledina, A.; Wang, J.; Jampel, H.D. Measurement of Gamma-Irradiated Corneal Patch Graft Thickness After Aqueous Drainage Device Surgery. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.F.; Doyle, J.W.; Ticrney, J.W., Jr. A comparison of glaucoma drainage implant tube coverage. J Glaucoma. 2002, 11, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schipper, P.; Weber, C.; Lu, K.; Fan, S.; Prokosch, V.; Holz, F.G.; Mercieca, K. Anterior segment OCT for imaging PAUL(®) glaucoma implant patch grafts: a useful method for follow-up and risk management. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Ichhpujani, P.; Kumar, S. Grafts in Glaucoma Surgery: A Review of the Literature. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2017, 6, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalta, A.H. Long-term experience of patch graft failure after Ahmed Glaucoma Valve® surgery using donor dura and sclera allografts. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2012, 43, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.; Yan, D.B. Five-Year Outcomes of Graft-Free Tube Shunts and Risk Factors for Tube Exposures in Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2024, 33, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, T.; LaCour, O.J.; Burgoyne, C.F.; LaFleur, P.K.; Duzman, E. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene reinforcement material in glaucoma drain surgery. J Glaucoma. 2001, 10, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuoka, K.; Tada, K.; Yasuoka, K. Ahmed Glaucoma Valve (AGV) implantation using Gore-Tex. Jpn J Ophthalmic Surg. 2024, 37, 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczynski, R.; Gumula, T.; Stodolak-Zych, E.; Pawlicki, K.; Wieczorek, J.; Kajor, M.; Blazewicz, S. Histopathological Evaluation of a Hydrophobic Terpolymer (PTFE-PVD-PP) as an Implant Material for Nonpenetrating Very Deep Sclerectomy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 5203–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, S.; Halenda, K. Late-onset Pseudomonas aeruginosa orbital cellulitis following glaucoma drainage device implantation. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2024, 34, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Okada, M.; Maki, K.; Shimazaki, A.; Kato, M.; Inoue, T. Tissue Reactivity to, and Stability of, Glaucoma Drainage Device Materials Placed Under Rabbit Conjunctiva. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2022, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Tian, C.; Qin, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Duan, X.; Shu, C.; Ouyang, C. The novel hybrid polycarbonate polyurethane / polyester three-layered large-diameter artificial blood vessel. J Biomater Appl. 2022, 36, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazic, S.; Kellett, C.; Afzal, I.; Mohan, R.; Killampalli, V.; Field, R.E. Three-year results of a polycarbonate urethane acetabular bearing in total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2020, 30, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Elkhodiry, M.; Shi, L.; Xue, Y.; Abyaneh, M.H.; Kossar, A.P.; Giuglaris, C.; Carter, S.L.; Li, R.L.; Bacha, E.; et al. A biomimetic multilayered polymeric material designed for heart valve repair and replacement. Biomaterials. 2022, 288, 121756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The CorNeat EverPatch: Superior Alternative to Tissue Grafts. accessed on 2025/1/29. https://www.corneat.com/news/the-corneat-everpatch%3A-superior-alternative-to-tissue-grafts.

- Kanter, J.; Garkal, A.; Cardakli, N.; Pitha, I.; Sabharwal, J.; Schein, O.D.; Ramulu, P.Y.; Parikh, K.S.; Johnson, T.V. Early Postoperative Conjunctival Complications Leading to Exposure of Surgically Implanted CorNeat EverPatch Devices. Ophthalmology. 2025, 132, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Vigo, J.I.; Fernández-Aragón, S.; Burgos-Blasco, B.; Ly-Yang, F.; De-Pablo-Gómez-de-Liaño, L.; Almorín-Fernández-Vigo, I.; Martínez-de-la-Casa, J.M.; Fernández-Vigo, J. Comparison in conjunctival-Tenon’s capsule thickness, anterior scleral thickness and ciliary muscle dimensions between Caucasians and Hispanic by optical coherence tomography. Int Ophthalmol. 2023, 43, 3969–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, M.; Han, Z.; Zou, H. In vivo cross-sectional observation and thickness measurement of bulbar conjunctiva using optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011, 52, 7787–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Beishri, A.S.; Malik, R.; Freidi, A.; Ahmad, S. Risk Factors for Glaucoma Drainage Device Exposure in a Middle-Eastern Population. J Glaucoma. 2019, 28, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Y.S.; Lee, N.Y.; Park, C.K. Risk factors of implant exposure outside the conjunctiva after Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2009, 53, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Qian, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Comparison study of surface-initiated hydrogel coatings with distinct side-chains for improving biocompatibility of polymeric heart valves. Biomater Sci. 2024, 12, 2717–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawana, K.; Kiuchi, T.; Yasuno, Y.; Oshika, T. Evaluation of trabeculectomy blebs using 3-dimensional cornea and anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009, 116, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffen, N.; Buys, Y.M.; Smith, M.; Anraku, A.; Alasbali, T.; Rachmiel, R.; Trope, G.E. Conjunctival complications related to Ahmed glaucoma valve insertion. J Glaucoma. 2014, 23, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EverPatch | Scleral Patch | P Value (ANOVA) | |

| Age | 65.8±15.1 | 62.5±17.9 | 0.463 |

| Type of Glaucoma | NVG 5, POAG 7, PEG 2,SG 2,PACG 2 | NVG 27, POAG 25, PEG 10, SG 26, PACG 5 | 0.132 (residual analysis) |

| Sex: Male/Female | 11/7 | 57/48 | 0.619 |

| Side: R/L | 8/10 | 50/55 | 1.00 |

| Pre-op IOP (mmHg) | 29.8±13.7 | 29.4±9.4 | 0.758 |

| Pre-op BCVA (logMAR) | 0.901±0.923 | 0.708±0.857 | 0.383 |

| Pre-op meds | 4.3±1.2 | 4.1±1.2 | 0.491 |

| Number of prior surgeries | 2.0±1.2 | 2.7±1.9 | 0.121 |

| Visual field defects (HFA: MD) | -24.3±9.2* | -18.9±9.3* | 0.107 |

| Type of GDD used | AGV 5, PGI 13 | AGV 105 | NA |

| Endothelial cell density (cells/mm2) | 2149±524 | 1993±636 | 0.504 |

| Type of EverPatch | Shield type 15, Rectangular type 3 | NA | |

| Quadrant of tube insertion | Sup-temporal 15, Infero-nasal 3 | Sup-temporal 52, Sup-nasal 12, Inf-temporal 30, Inf-nasal 11 | 0.008 (residual analysis) |

| Tube tip location | Anterior chamber 6, Ciliary sulcus 10, pars plana 2 | Anterior chamber 26, ciliary sulcus 21, pars plana 58 | P<0.001(residual analysis) |

| Pre-op conjunctival thickness at 1 mm from SS | 0.262±0.100 | NA | |

| Pre-op conjunctival thickness at 3 mm from SS | 0.267±0.114 | NA |

| Pre-op | 2W | 1M | 2M | 3M | ||

| EverPatch | # of medications | 4.3±1.2 | 1.2±2.0 | 1.8±2.1 | 2.0±2.1 | 2.2±2.0 |

| IOP | 31.1±13.0 | 15.6±6.3 | 16.6±4.3 | 17.5±8.8 | 16.1±4.9 | |

| logMAR BCVA | 0.869±0.823 | 1.067±0.993 | 1.087±0.963 | 1.105±0.972 | 1.018±1.058 | |

| Control | # of medications | 4.1±1.2 | NA | NA | NA | 2.2±1.8 |

| IOP | 29.7±10.9 | NA | 19.7±9.0 | NA | 18.1±5.7 | |

| logMAR BCVA | 0.708±0.857 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Time point | 1 mm thickness (mm) | % Change vs Baseline | P vs. Baseline | P vs 3.9 days | 3 mm Thickness (mm) | % Change vs Baseline | P vs Baseline | P vs 3.9 days |

| Baseline | 0.262±0.100 | 0 | - | - | 0.267±0.114 | 0 | - | - |

| 3.9 days N=18 | 0.468±0.217 | 78.4 | 0.004↑ | - | 0.543±0.332 | 103.4 | 0.001↑ | - |

| 2 weeks N=18 | 0.455±0.217 | 73.6 | 0.004↑ | 0.609(ns) | 0.498±0.267 | 86.8 | 0.002↑ | 0.925(ns) |

| 1 month N=18 | 0.305± 0.16 | 16.5 | 0.246(ns) | 0.007↓ | 0.342±0.160 | 28.2 | 0.052(ns) | 0.006↓ |

| 2 months N=18 | 0.241±0.147 | -8.2 | 0.687(ns) | 0.001↓ | 0.279±0.180 | 4.5 | 0.831(ns) | 0.002↓ |

| 3 months N=16 | 0.240±0.185 | -8.3 | 0.501(ns) | 0.005↓ | 0.268±0.169 | 0.4 | 0.877(ns) | 0.006↓ |

| Time point | SS-EP (mm) | P* | Time point | Conjunctival incision-EP (mm) | P* |

| 4.9 days N=9 | 1.01±0.20 | 3.9 days N=12 | 2.07 ± 0.69 | ||

| 2 weeks N=7 | 1.07±0.23 | 0.893 | |||

| 1 month N=14 | 1.13±0.34 | 0.263 | |||

| 2 months N=15 | 1.20±0.39 | 0.953 | |||

| 3 months N=14 | 1.21±0.40 | 0.484 | 3 months N=12 | 1.75 ± 0.71 | 0.117 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).