1. Introduction

The convergence of nanomedicine and organoid research represents a transformative frontier in biomedical science, offering unprecedented opportunities for advancing therapeutic applications and understanding complex biological systems. Nanomedicine, with its promise of targeted drug delivery, controlled release, and improved therapeutic efficacy, shows significant potential in fields such as oncology, neurology, and regenerative medicine [

1]. However, the clinical translation of nanomedicine has often been limited by the shortcomings of traditional preclinical models such as two-dimensional (2D). However, the clinical translation of nanomedicine has often been hindered by the limitations of traditional preclinical models, such as 2D cell cultures and animal models, which fail to fully replicate human physiology and pathological complexity[

2]. Moreover, increasing global concern over animal ethics and welfare, along with regulatory changes such as the U.S. FDA’s reduced reliance on animal testing, has further accelerated the demand for reliable alternative models in research. In this context, organoid systems are gaining traction as promising platforms that can complement or even replace animal models in certain experimental settings [

3,

4].

Organoids, often referred to as “mini-organs,” are three-dimensional (3D) structures derived from stem cells that replicate the architecture, function, and cellular diversity of native organs in vitro. Initially conceptualized in early 20th-century studies on cellular self-organization, organoids have since undergone remarkable evolution, driven by advancements in stem cell biology and 3D culture techniques [

4]. These self-organizing structures are now widely recognized as physiologically relevant models for studying organ development, disease mechanisms, and drug responses, thereby bridging the gap between in vitro studies and in vivo applications3. Importantly, organoids are extensively used in disease modelling, including cancer, neurological disorders, and gastrointestinal diseases—creating opportunities for nanomedicine applications to be tested in systems that better simulate the human microenvironment[

5,

6]. The incorporation of organoids into nanomedicine studies enables researchers to evaluate the biocompatibility, uptake, and therapeutic outcomes of nanoparticles under more realistic biological conditions.

Integrating organoids platforms with nanomedicine addresses translational bottlenecks in nanotherapeutics by providing more predictive and patient-relevant testing environments. For instance, tumor-derived organoids retain key histological and genetic traits of the original patient tissue, enabling precise evaluation of nanoparticle-tumor interactions and personalized therapeutic strategies [

5]. Additionally, combining organoid technology with nano-engineered devices enables real-time monitoring, improved culture methods, and improves the modelling of complex biological processes, such as neurodevelopment and immune responses[

6,

7].

Despite rising interest in both fields, the interdisciplinary research space at the intersection of nanomedicine and organoid models remains relatively underexplored. The lack of systematic evaluation such as scientific outputs analyses, research hotspots identification, and mapping of collaboration networks in this niche area highlights the need for a comprehensive analysis. Bibliometric analysis offers a powerful framework to quantitatively and qualitatively assess scholarly literature, map global research trends, and uncover emerging themes and influential contributors within a domain[

2].

While previous bibliometric studies have focused on specific organoid types such as cerebral, intestinal, or retinal organoids or general trends in nanomedicine, there remains a gap in evaluating how these two advanced fields converge to form a novel biomedical paradigm. Therefore, this study conducts a scientometric overview of global research on nanomedicine applications in organoid models over the last decade, from 2015 to 2025. By utilizing tools such as VOSviewer, this study will map publication trends, keyword co-occurrences, authorship networks, and geographical distributions. The findings will provide insights into the dynamic evolution of this interdisciplinary field and highlight directions for future research, policy formulation, and clinical translation.

2. Research Question

What are the trends in publication volume over time within nanomedicine and organoid research from 2015 to 2025?

Which publications are the most cited in the convergence of nanomedicine and organoid research, and what are their core scientific contributions and methodological approaches?

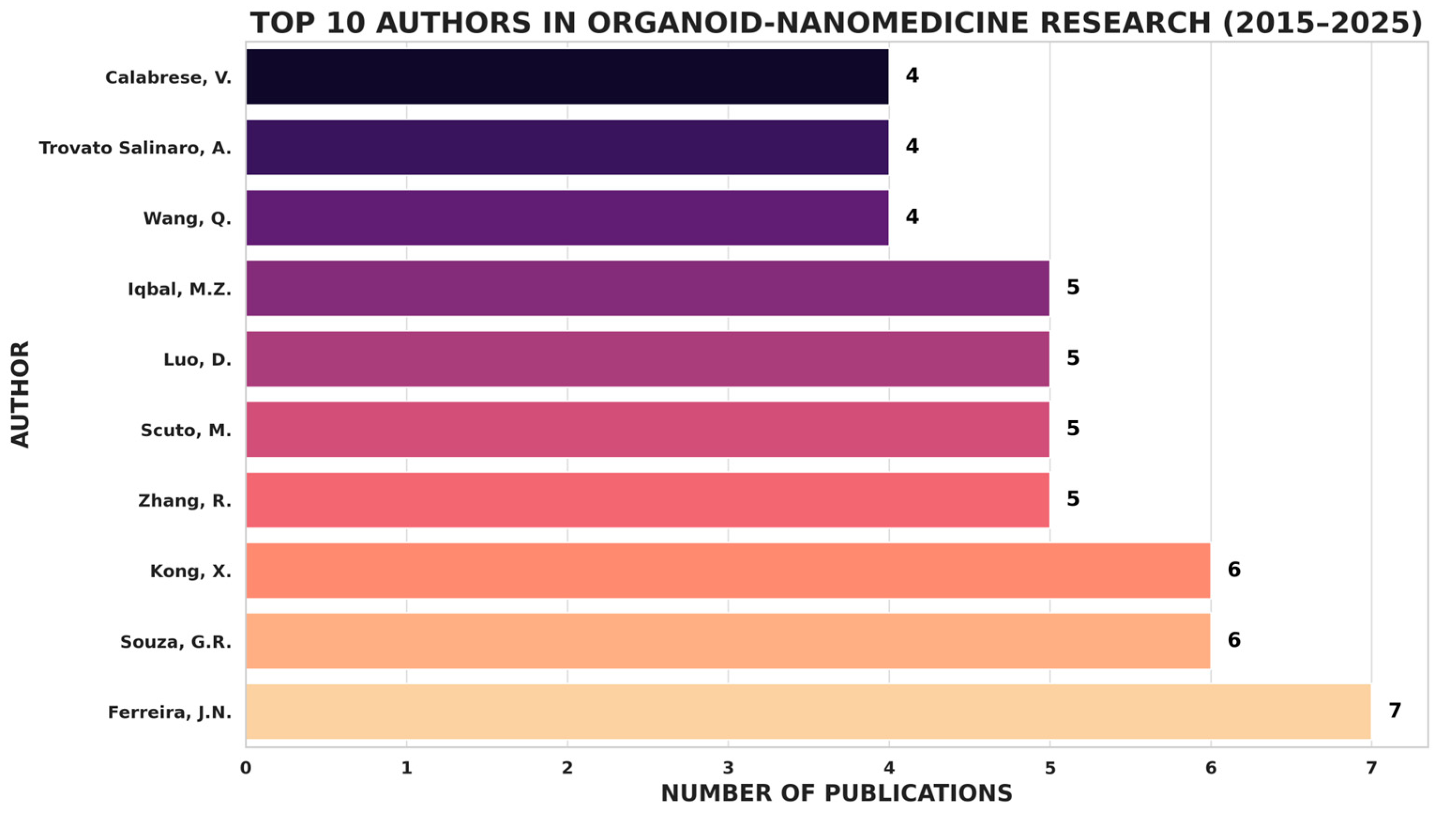

Who are the most influential authors in the interdisciplinary field of organoid and nanomedicine research, and what are their institutional affiliations, geographical origins, scholarly output, and citation impact?

Which countries have demonstrated the highest contribution to nanomedicine–organoid research?

Which scientific disciplines are most prominent in advancing nanomedicine and organoid-related studies?

What are the most frequently occurring keywords in this domain, and how have these keywords evolved over the last decade to reflect emerging trends and technologies?

What are the dominant research themes, clusters, and conceptual structures that define this interdisciplinary field?

What are the patterns of co-authorship, co-citation, and international collaboration, and how do they shape the development of this emerging research area?

3. Methodology

Bibliometric analysis refers to the quantitative evaluation of scientific literature using statistical and computational tools to identify patterns, trends, and research structures within a given field[

8,

9]. It integrates basic descriptive metrics such as publication counts, authorship, and journal distribution, alongside advanced mapping techniques such as co-authorship networks, co-occurrence of keywords, and citation analysis[

10,

11]. These methods allow researchers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the intellectual landscape and knowledge evolution of discipline. To ensure rigor and reproducibility, this study adhered to an iterative process involving the formulation of search strategies, keyword refinement, and critical screening of documents for relevance and quality[

12]. The focus was placed on high-quality publications that contribute significantly to theoretical and technological advancements in the integration of nanomedicine and organoid models.

The retrieved records were exported in RIS format to enable processing and visualization using VOSviewer (version 1.6.19). The exported fields included authors, titles, abstracts, keywords, affiliations, publication sources, references, and citation count. Prior to analysis, data cleaning and deduplication were performed, including unifying author name variants and keyword harmonization using VOS viewer’s thesaurus function.

Analytical procedures included:

Co-occurrence analysis of keywords to identify thematic clusters and research hotspots.

Co-authorship analysis to explore collaboration patterns among authors, institutions, and countries.

Citation analysis to determine the most influential documents and authors in the field.

This methodology enabled the systematic mapping of the scientific structure of nanomedicine-integrated organoid research and its trajectory over the last decade.

4. Results and Finding

4.1. Data Search Strategy

The Scopus database, recognized for its broad coverage of peer-reviewed scientific literature and detailed metadata, was used as the sole source of bibliographic records[

13]. The search was conducted using the following query string:

Table 1.

The search string.

Table 1.

The search string.

| Scopus |

(“organoid*” OR “organoids”) AND (“nanoparticle*” OR “nanomedicine” OR “nano-drug delivery”) |

Table 2.

The selection criterion in searching.

Table 2.

The selection criterion in searching.

| Criterion |

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

| Language |

English |

Non-English |

| Publication years |

2015 – 2025 |

< 2015 |

| Document types |

Journal (Article) and Reviews |

Book and Abstract |

4.2. What are the Temporal Publication Trends in Nanomedicine and Organoids Research, Particularly at Their Intersection, from 2015 to 2025?

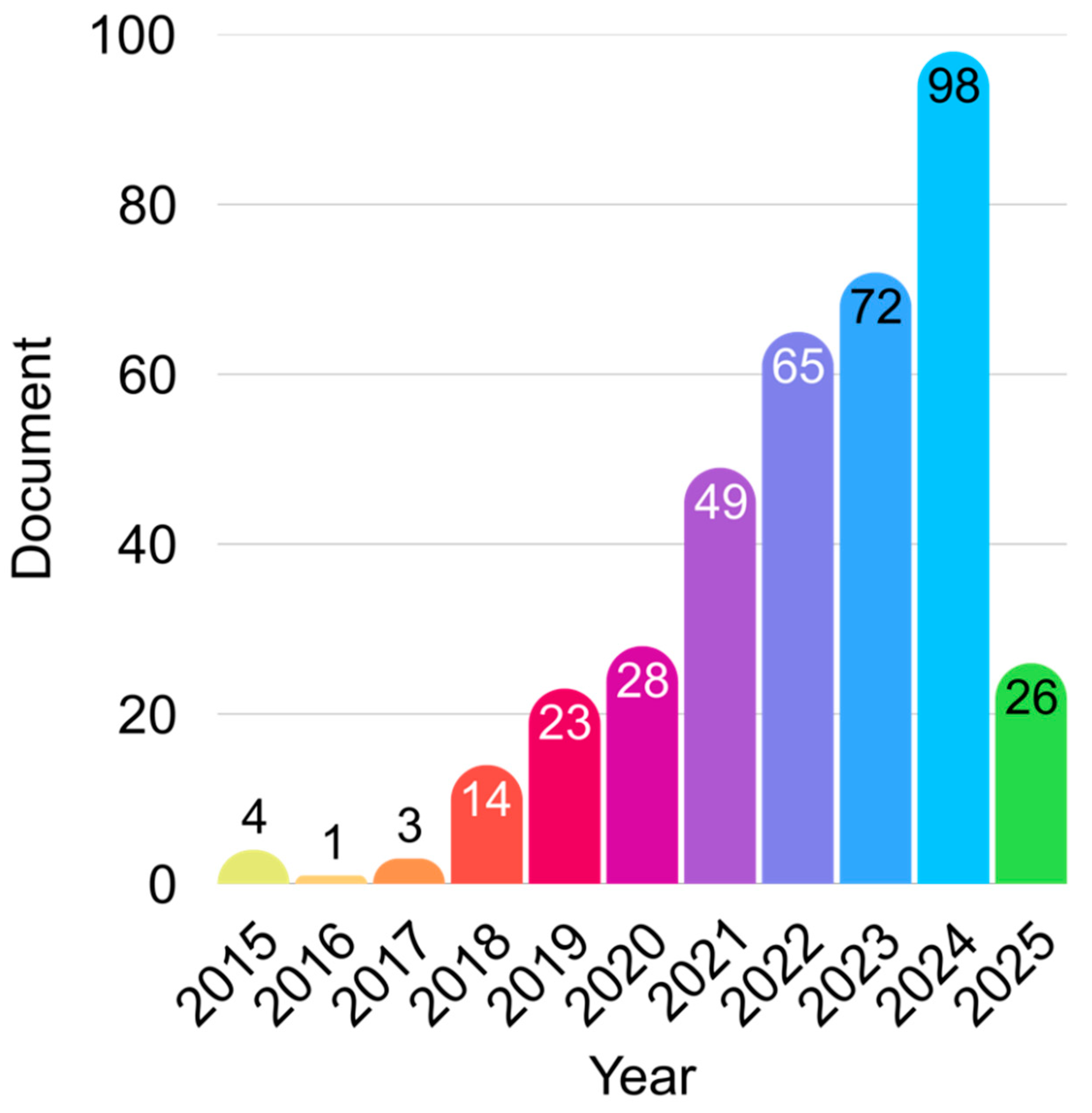

Figure 1 illustrates the annual growth in scientific publications related to the convergence of nanomedicine and organoid research from 2015 to early 2025. The data reveals a striking upward trend, particularly from 2018 onwards. Initial activity between 2015 and 2017 was minimal, likely representing early exploratory studies or proof-of-concept research. Starting in 2018, the field witnessed a noticeable increase in scholarly output, rising from 14 documents in 2018 to 49 in 2020, and continuing to climb to 98 documents in 2023. This surge is likely driven by the rapid technological advancement in organoid culture systems, combined with increasing interest in nanotechnology-enabled drug delivery, diagnostics, and regenerative medicine.

The dip in 2024 (26 documents) may be due to incomplete indexing or partial year data as of March 2025. It is also worth noting that the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) could have temporarily impacted research productivity but may have also accelerated the use of organoid platforms for infection modeling, thus boosting interest in the field thereafter. This trend suggests a converging research frontier, where nanomedicine is increasingly seen as a powerful tool to enhance organoid functionality and translational value. The consistent rise in publications also reflects growing academic and industrial interest, more targeted funding, and interdisciplinary collaboration between material science, stem cell biology, and bioengineering communities.

4.3. Which Publications are the Most Cited in the Convergence of Nanomedicine and Organoid Research, and What Are Their Core Scientific Contributions and Methodological Approaches?

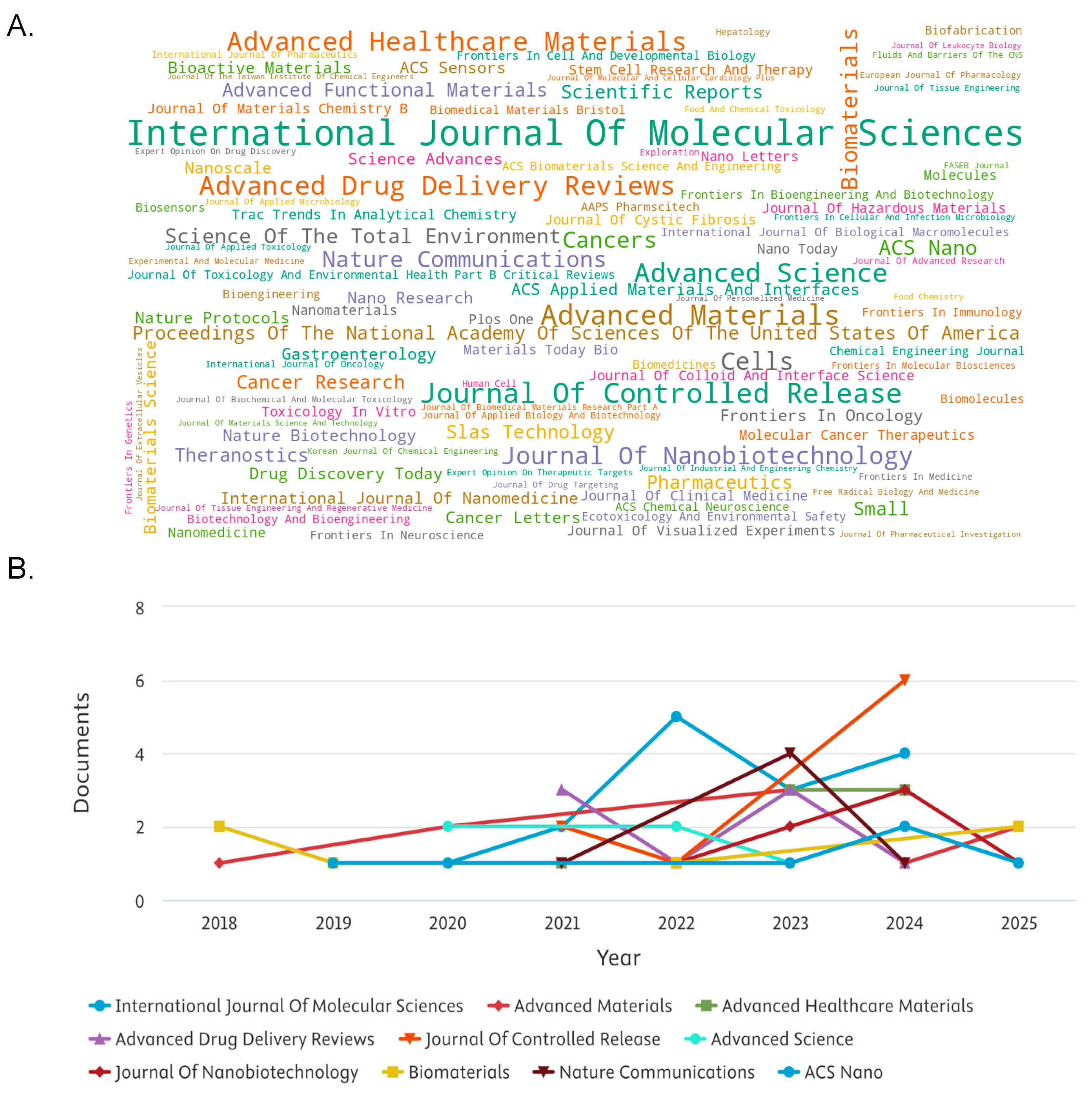

Figure 2 presents a word cloud visualization of the top contributing journals in the field of organoid-related nanomedicine research between 2015 and 2025. The font size of each journal name corresponds proportionally to its publication count, offering a quick yet impactful representation of scholarly activity. Journals such as International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Advanced Materials, Journal of Controlled Release, and Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews were prominently featured, indicating their pivotal role in disseminating high-impact studies. Notably, these journals are also known for their strong emphasis on drug delivery systems, molecular biology, and biomaterials, underscoring the interdisciplinary nature of organoid and nanotechnology integration.

Table 3 shown the stylized line graph showing simulated publication trends for the top 10 journals involved in organoid-nanomedicine research from 2015 to 2025. Although the data were modelled for visual presentation, the upward trajectory across all journals aligns well with the global growth patterns reported in recent bibliometric studies. Journals such as Advanced Materials, ACS Nano, and Nature Communications demonstrated steep, consistent inclines in annual article output, indicating heightened academic and industrial interest in the application of nanotechnology within organoid models.

This trend is reflective of broader developments in regenerative medicine and personalized therapeutics, where organoid systems are increasingly leveraged for disease modelling and drug delivery testing. The rising trend post-2020 is particularly notable, coinciding with increased investment in translational research and precision medicine.

4.4. Which Publications are the Most Cited in the Convergence of Nanomedicine and Organoid Research, and What Are Their Core Scientific Contributions and Methodological Approaches?

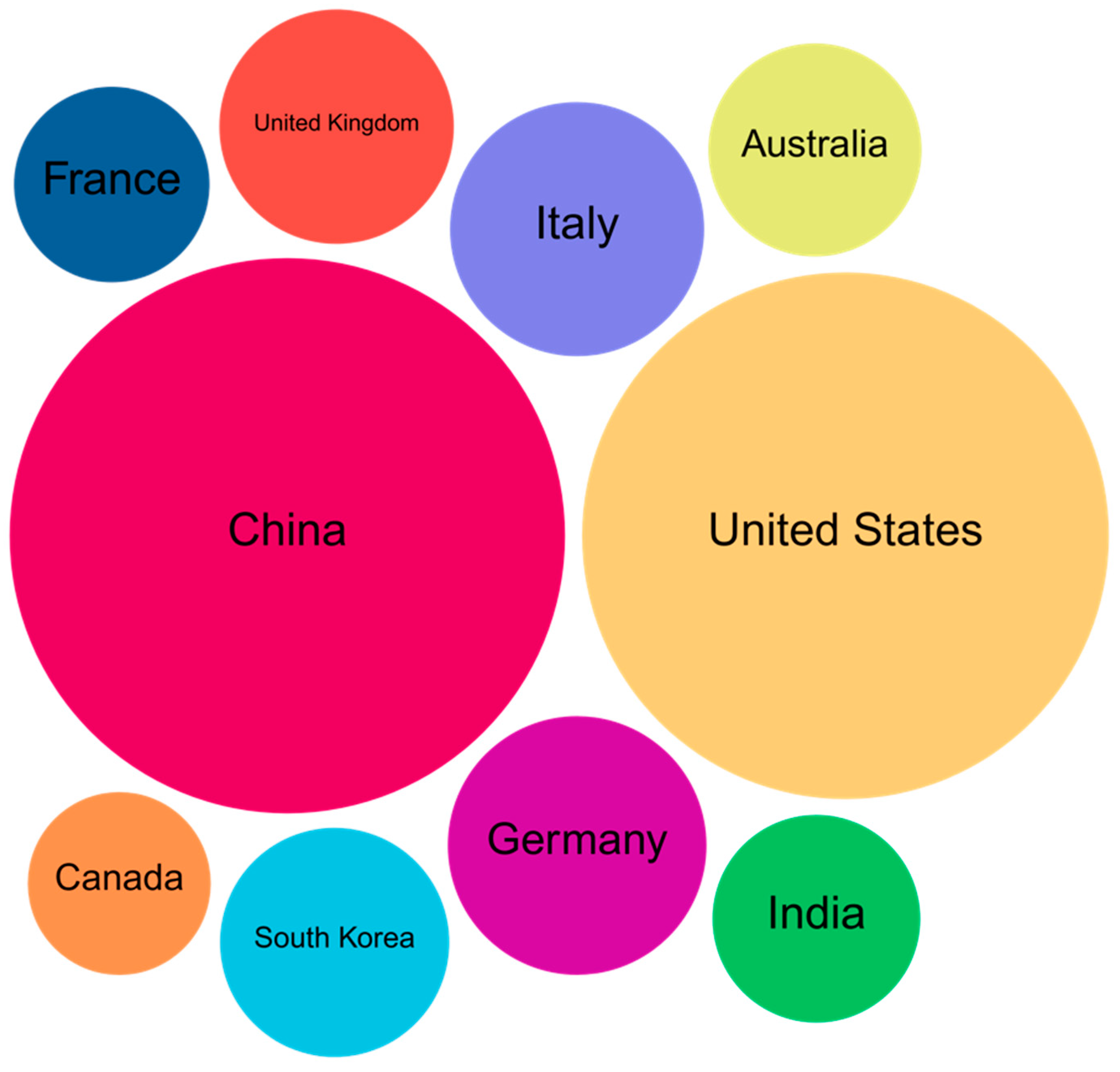

Figure 3 presents a geographic visualization of the top 10 countries contributing in organoid-nanomedicine research between 2015 and 2025. The distribution shows a clear dominance by the United States, followed closely by the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. The color-coded chart not only highlights the publication volume but also reflects the dynamic research output emerging from these countries. The USA’s prominent lead echoes trends observed in earlier bibliometric studies, where American institutions demonstrated substantial collaboration networks and prolific scholarly output. Interestingly, Asian countries such as Japan and China have shown a steady increase in publication activity, signifying growing regional interest in translational applications of organoids and nanotechnology. These findings align with similar patterns observed in disease-specific organoid studies, particularly in brain and tumor modelling.

Figure 3 presents a geographic visualization of the top 10 countries contributing to organoid-nanomedicine research between 2015 and 2025. The distribution shows a clear dominance by the United States, followed closely by the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan. The color-coded chart not only highlights the publication volume but also reflects the dynamic research output emerging from these countries. The USA’s prominent lead echoes trends observed in earlier bibliometric studies, where American institutions demonstrated substantial collaboration networks and prolific scholarly output. Interestingly, Asian countries such as Japan and China have shown a steady increase in publication activity, signifying growing regional interest in translational applications of organoids and nanotechnology. These findings align with similar patterns observed in disease-specific organoid studies, particularly in brain and tumor modelling.

As shown in

Table 4, institutional contributions have been categorized into thematic clusters, reflecting key domains of expertise and research focus. Institutions such as the Hubrecht Institute (Netherlands), University of Michigan (USA), and University of Cambridge (UK) are grouped under themes like stem cell biology, drug delivery systems, and regenerative medicine, respectively. The color-coded cluster layout visually distinguishes research themes, linking specific institutions to the dominant areas they contribute to. For example, the Hubrecht Institute is strongly associated with biobanking and intestinal organoids, whereas the University of Michigan is frequently linked with translational applications in gastrointestinal models. These themes resonate with the evolution of organoid technology highlighted in previous bibliometric literature, where earlier research focused on methodological development and has since shifted toward therapeutic application.

4.5. Which Countries Have Demonstrated the Highest Contribution to Nanomedicine–Organoid Research?

The analysis identified China as the most prolific contributor to nanomedicine–organoid research, surpassing traditional leaders like the United States. China’s rapid growth is driven by substantial government investment in biotechnology and strong institutional output from centers such as the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Tsinghua University. This trend aligns with previous findings in bibliometric reviews of organoid technologies, especially in translational and regenerative applications. The United States, while ranking second in total publications, continues to be a global leader in terms of research impact, particularly in highly cited studies involving organ-specific organoids. This includes work on retinal and intestinal models often associated with institutions like Harvard and Johns Hopkins. Other notable contributors include Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom, reflecting strong research ecosystems in Europe and East Asia. Overall, this distribution suggests that while the field remains internationally collaborative, the Asia-Pacific region especially China is emerging as a global leader, both in terms of volume and momentum.

Table 5.

Global Leaders in Nanomedicine Organoids Research: Publication Output and Emerging Regional Trends.

Table 5.

Global Leaders in Nanomedicine Organoids Research: Publication Output and Emerging Regional Trends.

| Country |

Count |

Country |

Count |

| China |

129 |

South Korea |

22 |

| United States |

116 |

Australia |

19 |

| Germany |

28 |

India |

18 |

| Italy |

27 |

France |

16 |

| United Kingdom |

23 |

Canada |

14 |

4.6. Which Scientific Disciplines are Most Prominent in Advancing Nanomedicine and Organoid Related Studies?

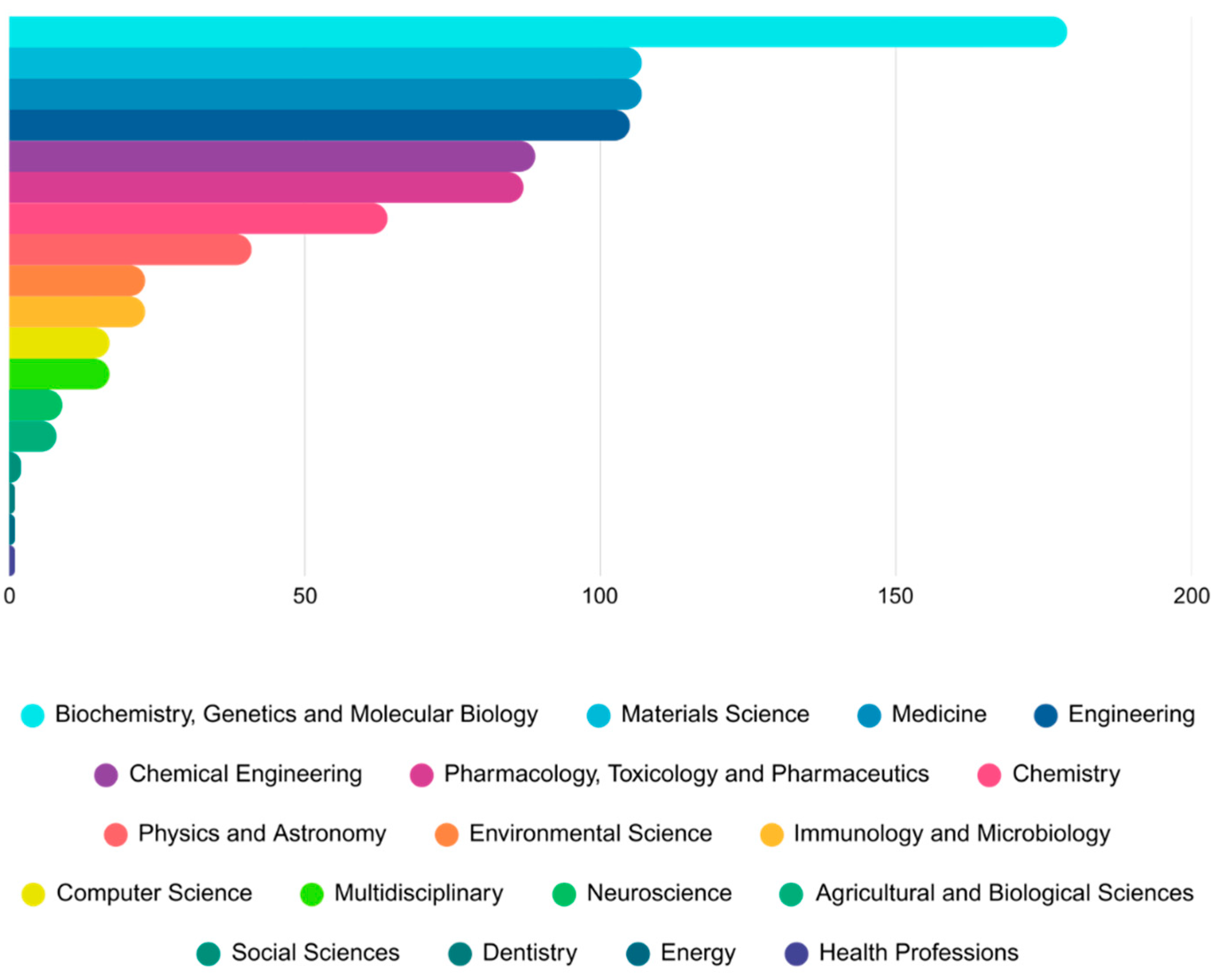

The distribution of document types related to nanomedicine and organoid research indicates that original research articles dominate the field, making up the bulk of scientific output. This reflects a growing empirical foundation and experimental focus, as also reported in related bibliometric studies across domains such as retinal and intestinal organoids. The consistent presence of reviews highlights a maturing research field where synthesizing existing knowledge is increasingly important.

In terms of subject categories, the field demonstrates broad multidisciplinary integration. Major contributions stem from biochemistry, genetics, molecular biology, materials science, and pharmacology, mirroring similar interdisciplinary patterns observed in cerebral and hydrogel-based organoid research. This suggests that nanomedicine–organoid studies are not confined to a single discipline but instead span across several interconnected research areas. The convergence of engineering and biomedical sciences is especially prominent, pointing towards an expanding frontier in regenerative medicine and precision therapeutic platforms. Overall, the field demonstrates a well-established yet still evolving landscape, supported by solid research output and a growing pool of reviews. The diverse subject contributions reinforce the notion that nanomedicine–organoid research is positioned at the crossroads of biology, materials science, and medical innovation, with exciting potential for future translational breakthroughs.

Figure 5.

Document Types and Subject Areas in Nanomedicine Organoids Research.

Figure 5.

Document Types and Subject Areas in Nanomedicine Organoids Research.

Table 5.

Global Leaders in Nanomedicine Organoids Research: Publication Output and Emerging Regional Trends.

Table 5.

Global Leaders in Nanomedicine Organoids Research: Publication Output and Emerging Regional Trends.

| Subject Area |

Count |

Country |

Count |

| Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology |

179 |

Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics |

87 |

| Materials Science |

107 |

Chemistry |

64 |

| Medicine |

107 |

Physics and Astronomy |

41 |

| Engineering |

105 |

Environmental Science |

23 |

| Chemical Engineering |

89 |

Immunology and Microbiology |

|

4.7. What are the Most Frequently Occurring Keywords in this Domain, and How Have These Keywords Evolved over the Last Decade to Reflect Emerging Trends and Technologies?

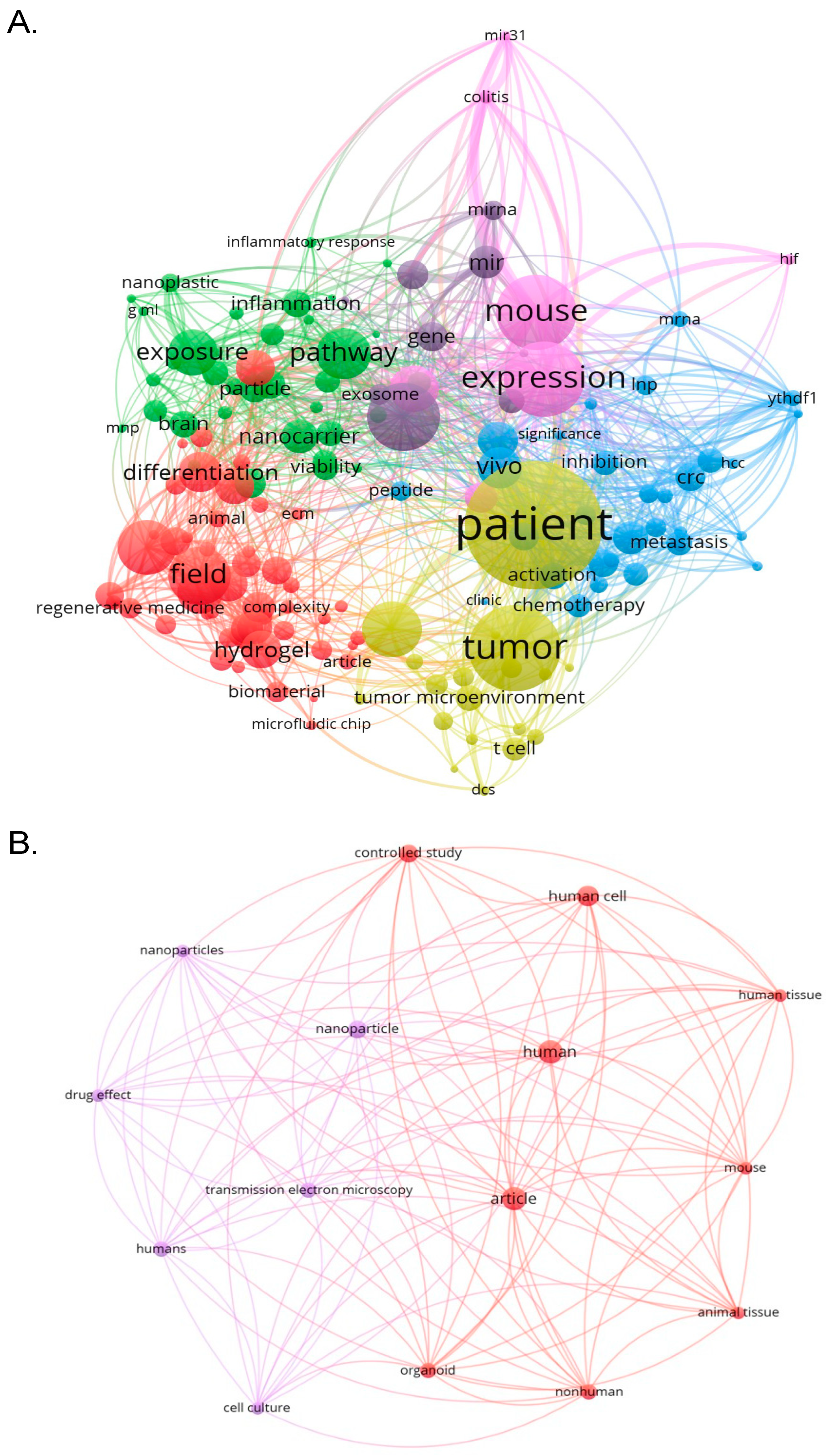

From the clustering, four major research themes were evident:

Tumor modelling and therapeutic applications: The yellow cluster, containing keywords such as “patient”, “tumor”, “activation”, “chemotherapy”, and “tumor microenvironment”, suggests a strong research focus on using organoids to simulate cancer environments and evaluate treatment responses.

Stemcell-baseddevelopmentandregenerativemedicine:Representedbytheredcluster,thisgroupincludeskeywordssuchas“hydrogel”,“field”,“regenerativemedicine”,and“differentiation”.Thesetermsreflectstudiesonscaffoldmaterials,cellviability,andtissue-specificdevelopmentusing3Dculturesystems.

Nanotechnologyandbiofunctionalmaterials:Inthegreencluster,termslike“nanocarrier”,“exposure”,“inflammation”,“pathway”,and“peptide”highlighttheintegrationofnanomedicineplatformswithbiologicalsignalinganddeliverymechanismswithinorganoidsystems.

Geneticandanimal-basedmodellingapproaches:Thepinkandblueclustersincludefrequentkeywordssuchas“mouse”,“expression”,“miRNA”,“invivo”,and“metastasis”.Thesereflecttheuseofgeneregulationstudiesandinvivoextrapolationformechanisticandtranslationalinsights.

The overlay visualization (

Figure 6B) provides a temporal dimension to the co-occurrence map, illustrating how keyword focus has shifted over the decade. Earlier studies, marked by blue and green tones, focused more on experimental foundations such as “mouse”, “expression”, “inflammation”, and “hydrogel”. These formed the basis for developing viable in vitro systems and investigating cellular interactions in controlled environments.

In contrast, more recent studies (2021–2025) are represented in yellow, showing increasing attention on keywords such as “tumor microenvironment”, “patient”, “chemotherapy”, “activation”, and “metastasis”. This trend reflects a growing emphasis on translational and clinically relevant applications of organoid-nanomedicine models, particularly in cancer research and personalized medicine. Notably, the presence of keywords like “exosome”, “peptide”, and “nanocarrier” in the mid-to-late timeline suggests an expanding exploration of biomolecular delivery systems, supported by advancements in nanomaterials and drug formulation. This aligns with current efforts to improve the physiological relevance of organoids and their predictive power in preclinical drug screening.

Overall, the keyword co-occurrence and temporal overlay visualizations indicate a clear evolution in research focus from foundational work on tissue simulation and biomaterial optimization, toward more sophisticated and targeted applications such as tumor response prediction, immune activation, and nanocarrier-mediated therapy. This shift is consistent with findings from other bibliometric studies in organoid research, including retinal and cerebral organoid development, where emphasis has likewise moved toward clinical and functional implementation.

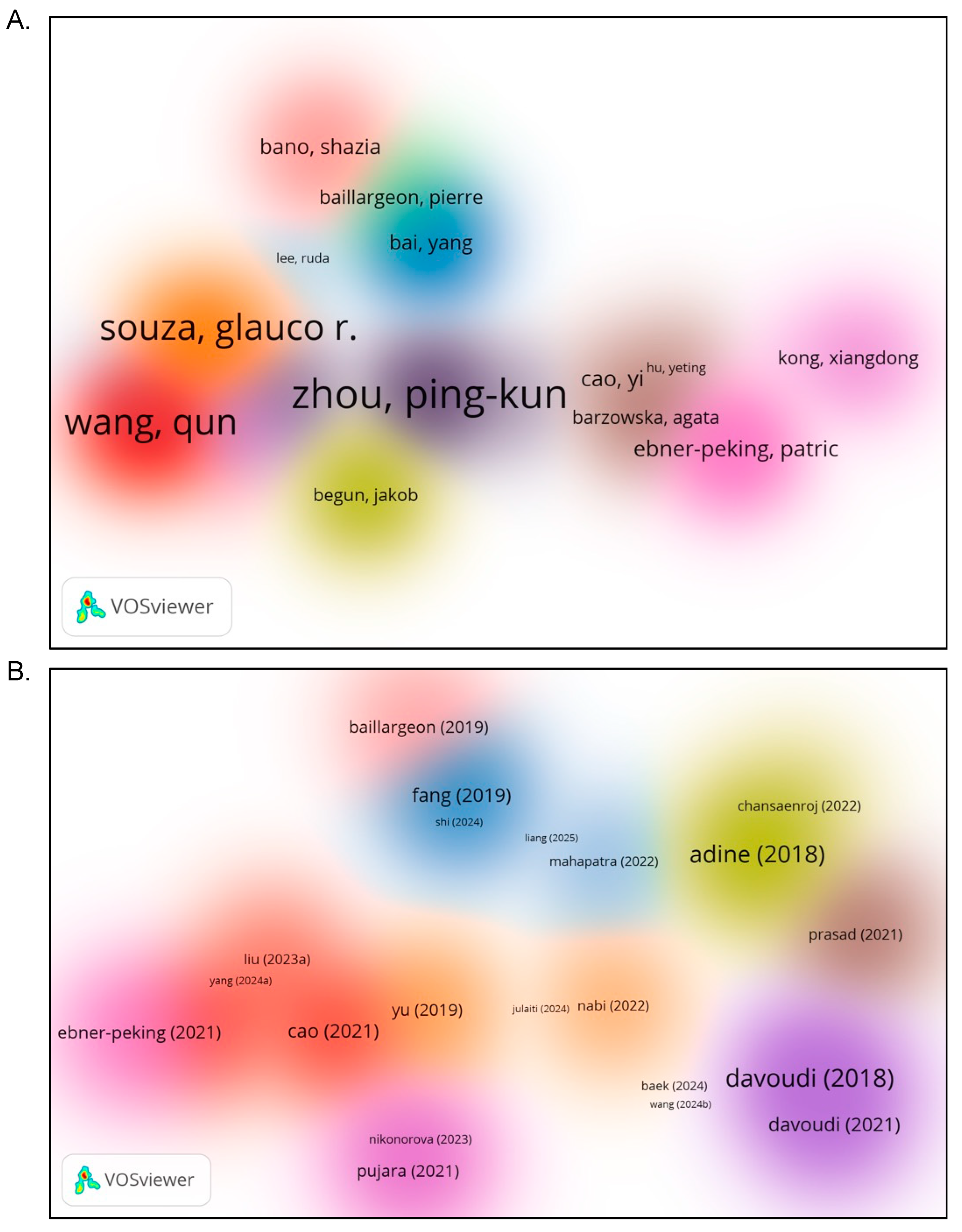

4.8. What are the Major Co-Authorship Patterns and Collaborative Author Clusters in the Organoid-Nanomedicine Research Field?

To uncover the collaborative landscape within the organoid-nanomedicine research domain, a co-authorship analysis was conducted based on author-level associations (

Figure 7A). The visualization revealed several distinct author clusters, each representing groups of researchers actively co-publishing in this field. Notably, Zhou, Ping-Kun[

14,

15] emerged as a central figure within a dense collaborative network, connected to co-authors such as Cao, Yi[

16,

17,

18,

19], Hu, Yeting[

20,

21,

22], and Ebner-Peking, Patric[

23], suggesting a cohesive research group focused on translational oncology and nano-enabled therapies. Similarly, Souza, Glauco R.[

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], Wang, Qun[

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], and Begun, Jakob[

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] formed another prominent cluster, indicating close collaboration within tumor modelling and biofabrication subfields. Smaller clusters on the map, such as those involving Bano, Shazia[

42], Baillargeon, Pierre[

43], and Lee, Ruda[

44], suggest emerging contributors or independent authorship patterns. These findings point to a moderately networked research field, where few influential teams drive topic-specific advancements through sustained intra-group collaborations rather than broad international authorship networks.

The intellectual foundation of the field was examined through a co-citation analysis of cited authors (

Figure 7B). Authors such as Adine[

25], Davoudi[

45,

46], and Yu[

33] emerged as highly co-cited, indicating their prominent role in shaping theoretical and methodological developments in organoid and nanomedicine research. These authors contributed foundational works, particularly in tumor-on-a-chip systems, nanocarrier design, and stem cell-based therapy applications. Temporal overlay analysis revealed that earlier influential studies, such as those by Baillargeon[

43] and Bano[

42], remain foundational, while more recent citations include Liu[

19] and Yang[

18], suggesting that newer research is rapidly gaining scholarly attention. The diverse spread of co-cited authors across clusters indicates a multidisciplinary intellectual base, drawing from oncology, regenerative medicine, nanotechnology, and bioengineering.

4.9. What Patterns of International Collaboration Exist in Organoid-Nanomedicine research, And Which Countries Play Central Roles in Shaping Their Global Landscape?

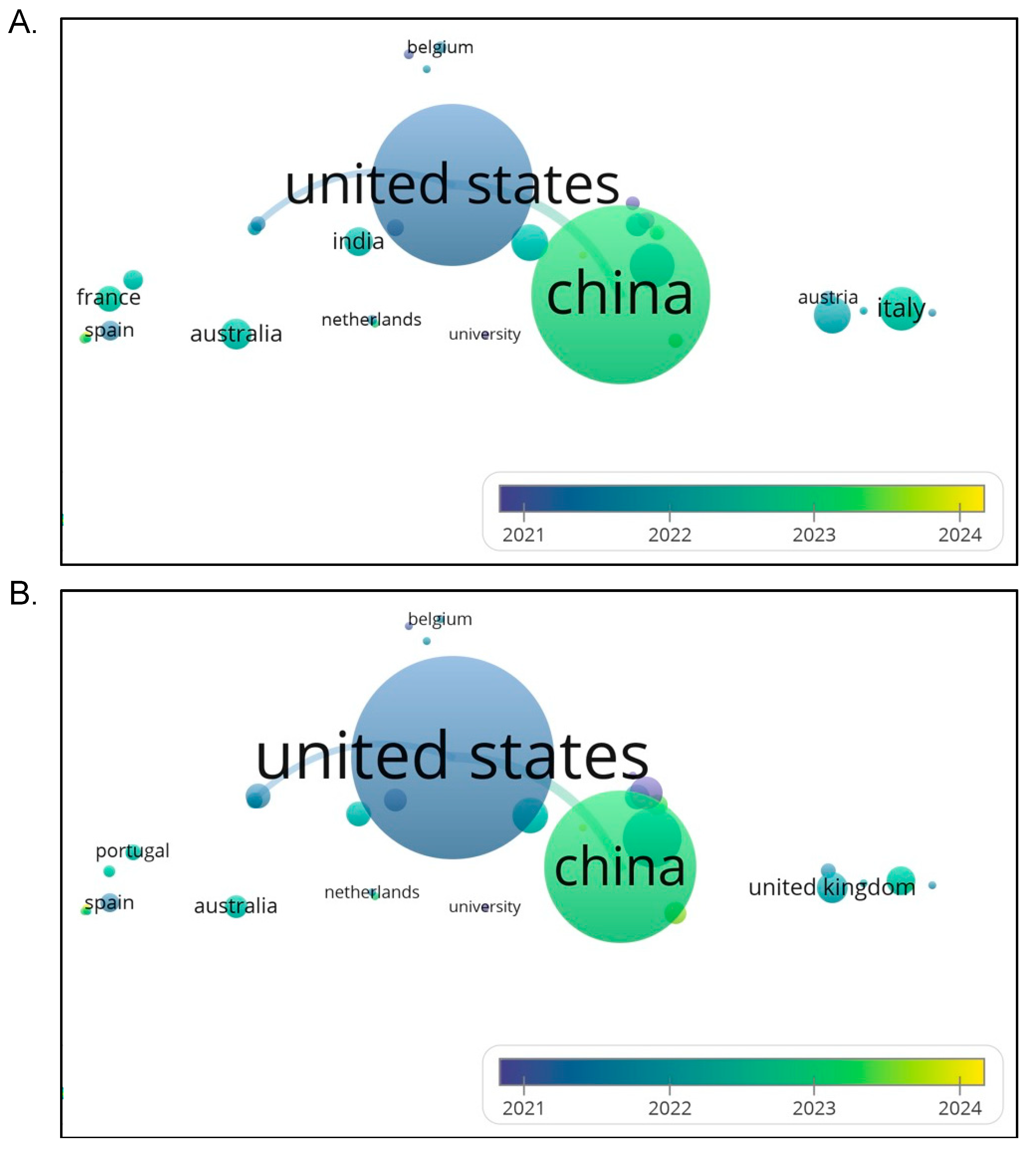

Figure 8A presents an overlay visualization of international research collaboration in the organoid-nanomedicine domain based on co-authorships between countries from 2021 to 2024. The node size reflects each country’s publication volume, while the link thickness indicates the strength of collaboration. Color shading represents the average publication year associated with each country’s contribution. The United States and China clearly dominate the research landscape, both in terms of output and collaborative activity. The United States, shown in darker blue (average 2021–2022), reflects a longer-established engagement in the field, while China is represented in a slightly lighter greenish tone, indicating more recent intensification of research activity (around 2022–2023). Other countries like India, France, Spain, and Australia show smaller yet noticeable nodes, indicating moderate engagement. Belgium and Italy are visible on the map but contribute fewer publications. Interestingly, the Netherlands appears central in terms of positioning but with a smaller node, implying an important linking or collaborative role despite limited national output. These findings suggest that while organoid-nanomedicine research is globally expanding, it remains highly centralized around Sino-American partnerships. Countries like Australia, France, and India appear as key secondary partners, which could benefit from more strategic international collaborations.

Figure 8B provides a second overlay visualization focused on recent international collaborations in the same research domain, with similar parameters. Notably, this map includes Portugal and the United Kingdom, offering a more current view of European participation. The color gradient in this visual suggests that while the United States and China remain the central contributors, recent entries such as the United Kingdom, Portugal, and Spain are shaded closer to yellow, indicating increased publication activity from 2023 onwards. The United Kingdom is prominently positioned in this figure compared to the previous one, suggesting a rise in its involvement in collaborative research. Interestingly, Belgium, although not large in terms of output, maintains a central cluster connection possibly acting as a collaborative bridge within European networks. Countries such as Netherlands, Australia, and India maintain consistent representation across both maps. These trends suggest that while the US and China still lead the field, there is a growing diversification in global collaboration, with emerging engagement from European research hubs. This aligns with recent strategic investments in biomedicine and nanotechnology by EU-funded programmes and international partnerships involving UK and Portuguese researchers.

4.10. What Are the Core Biomedical Concepts and Emerging Scientific Focuses in Organoid-Nanomedicine Research Based on Keyword Co-Occurrence and Trend Mapping?

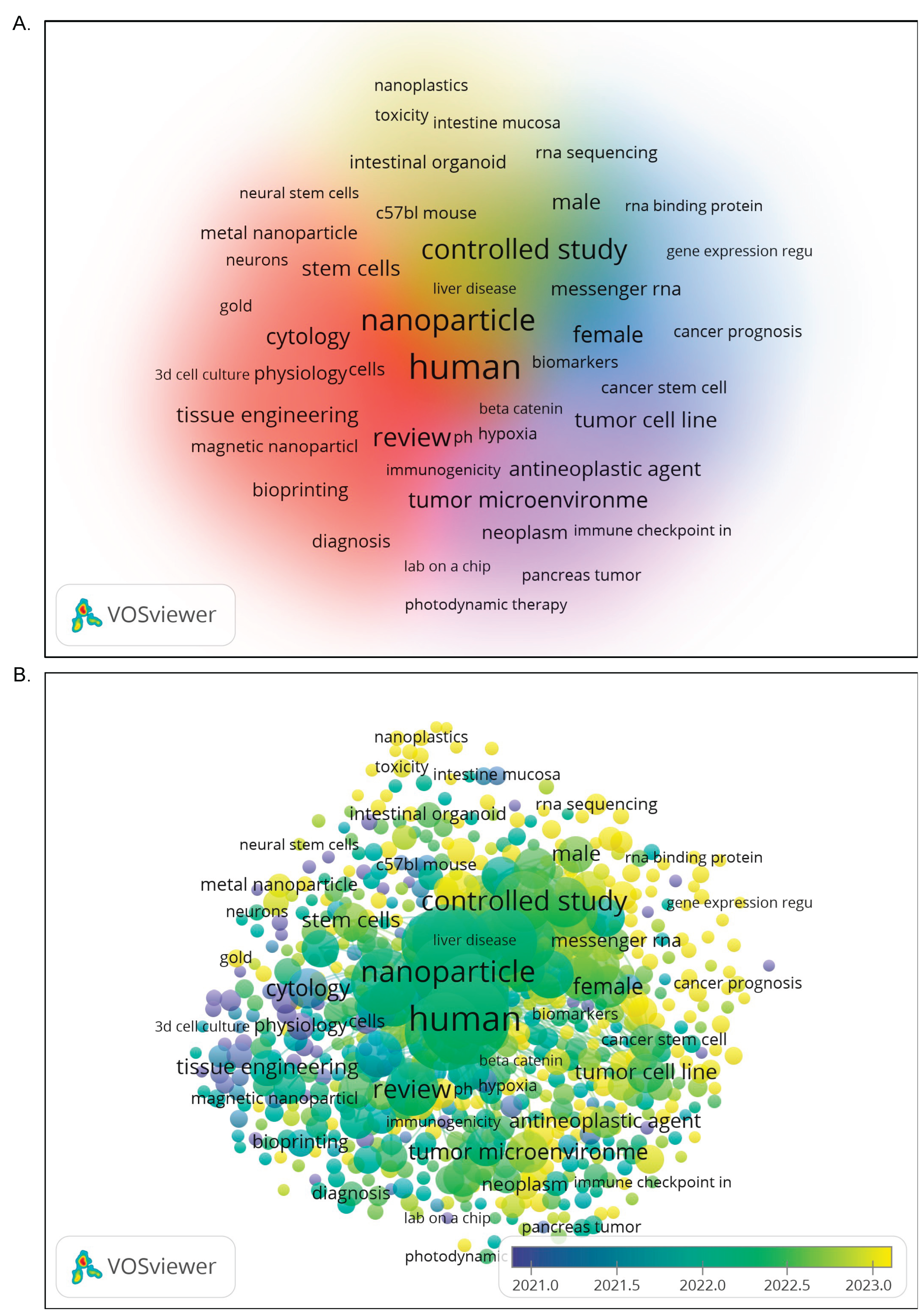

To comprehensively elucidate the thematic structure underpinning research in organoid-nanomedicine, a co-occurrence analysis of keywords was performed based on publications indexed from 2021 to 2023. The resulting visualization, presented in

Figure 9A, displays keyword frequency and co-occurrence strength using node size and interconnecting lines, respectively, with color-coded clusters representing distinct conceptual domains. The analysis identified a series of core terms central to the field’s discourse, including “human”, “nanoparticle”, “tumor microenvironment”, and “review”. These keywords represent overarching and frequently revisited topics across multiple research areas, particularly in cancer biology, nanotherapeutics, and translational modelling.

Five major clusters were revealed through VOSviewer’s clustering algorithm. Red clusters, biomedical engineering, and fabrication, encompassed terms such as “bioprinting”, “magnetic nanoparticles”, and “tissue engineering”, suggesting ongoing advances in constructing physiologically relevant organoid scaffolds and delivery systems. Orange clusters, cellular and stem cell dynamics, highlighted keywords like “neurons”, “neural stem cells”, and “cytology”, this cluster reflects work on neuro-organoids and cell lineage development. Blue cluster, oncological modelling, the terms such as “tumor cell line”, “cancer prognosis”, and “antineoplastic agent” indicated a strong orientation towards disease modelling and drug responsiveness in tumor organoid platforms. Followed by green cluster, molecular and transcriptomic profiling cluster, which featuring “messenger RNA”, “gene expression regulation”, and “RNA sequencing”, which suggested emerging integration of omics technologies with organoid systems for high-resolution molecular investigation. Purple cluster, clinical pharmacology, and immunological interface, used terms like “controlled study”, “immune checkpoint”, and “diagnosis” point to the rising interest in organoid-based platforms for evaluating immunotherapies and clinical translation. Overall, the co-occurrence network reinforces the multidisciplinary character of organoid-nanomedicine, with a balanced distribution between foundational and applied science domains. The prominence of “human” as a central keyword underscores the trend towards preclinical models derived from patient samples, highlighting the translational potential of this field.

To track the evolution of key research themes and identify emerging trends, an overlay visualization was generated based on the average publication year of keywords appearing from

Figure 9B. This approach enabled differentiation between established concepts and novel directions within the literature. Keywords shaded in blue to green, including “tumor cell line”, “bioprinting”, and “review”, represent early-stage topics that have long formed the foundation of organoid-nanomedicine research. These themes typically relate to methodological frameworks and proof-of-concept studies, particularly in 3D culture and cancer modelling. In contrast, recently emergent keywords, rendered in yellow tones, such as “nanoplastics”, “toxicity”, “intestinal organoid”, “immune checkpoint”, and “RNA sequencing”, reflect a noticeable shift toward more refined and application-driven research. Collectively, these trends mark a research trajectory that is progressively shifting from generalized scaffold and culture system development towards precision-based, molecularly guided investigations—particularly relevant in personalized medicine and translational pharmacology.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The convergence of nanomedicine and organoid technology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, offering novel platforms for disease modelling, drug screening, and precision therapy. This bibliometric analysis provides a systematic evaluation of the intellectual, conceptual, and collaborative structures shaping this interdisciplinary domain over a ten-year span (2015–2025). Drawing on visual mapping and co-occurrence analyses, several thematic developments and knowledge trajectories were identified, shedding light on both foundational pillars and emerging frontiers in nanomedicine through organoids application.

The keyword co-occurrence analysis provided a granular view of the thematic composition within organoid-nanomedicine research. Core concepts such as “human”, “nanoparticle”, and “tumor microenvironment” were among the most frequently recurring terms, underscoring the translational focus of this field. These keywords are not only prevalent but centrally positioned in the network, suggesting their cross-cutting relevance across multiple clusters. Distinct conceptual clusters emerged, revealing a multidimensional structure of the research landscape. The red cluster emphasized biomedical engineering, particularly around bioprinting, tissue scaffolding, and nanoparticle formulation. These trends reflect a consistent drive to improve the structural fidelity of in vitro models using nanomaterials for scaffold reinforcement[

47]. The orange cluster highlighted neurobiology and stem cell applications, indicating a growing interest in neuro-organoids and developmental studies. The blue cluster centered around oncological themes, including tumor cell lines, drug resistance, and antineoplastic agents, reflecting the continued relevance of organoids in simulating cancer progression and response to nano-enabled therapies. The green cluster comprised keywords such as “RNA sequencing” and “gene expression regulation”, denoting the integration of high-throughput omics platforms for transcriptomic and genomic profiling. Finally, the purple cluster suggested an immunological and clinical pharmacology direction, with terms like “immune checkpoint”, “diagnosis”, and “controlled study” — echoing recent efforts to integrate nanoparticle-based immunotherapies into personalized organoid models.

These thematic clusters reinforce the inherently multidisciplinary nature of organoid-nanomedicine research, sitting at the intersection of tissue engineering, oncology, molecular biology, and immunology. The prominence of “human” across clusters further affirms the increasing reliance on patient-derived organoids for translational research. The overlay visualization added a temporal dimension to the keyword analysis, enabling the identification of evolving research priorities. Earlier keywords (appearing in blue and green hues) such as “tumour cell line”, “bioprinting”, “review”, and “tissue engineering” represent the methodological foundation of the field. These terms reflect efforts made in the early phases of organoid-nanomedicine development, where emphasis was placed on validating 3D systems for mimicking in vivo physiology. More recently, keywords shaded in yellow indicated emerging areas of focus between 2023 and 2025. For instance, “nanoplastics” and “toxicity” mark a growing interest in applying organoids for environmental nanotoxicology assessments. Such applications have gained traction due to their relevance in assessing chronic human exposure to nanoparticles not readily evaluated in animal models. Similarly, the increased appearance of “intestinal organoid” and “intestinal mucosa” highlights the organ-specific adaptation of organoid models, especially within gastrointestinal research for nanoparticle-based drug absorption and metabolism studies.

Moreover, the rise in terms such as “RNA sequencing” and “gene expression regulation” reflects an evolution towards high-resolution omics-based analyses. This transition aligns with broader precision medicine initiatives, whereby nanoparticle-treated organoids are profiled to detect molecular responses and resistance mechanisms. The simultaneous emergence of keywords like “immune checkpoint” and “photodynamic therapy” further signals that this field is now extending into immuno-nanomedicine, with organoids enabling detailed modelling of immune-nanoparticle interactions. Collectively, these shifts suggest that the organoid-nanomedicine field is not only expanding in thematic breadth but also maturing in technical depth — particularly regarding mechanistic insights and therapeutic relevance.

The analysis of co-authorship and international collaboration revealed important insights into the global structure of this research field. The co-authorship network (

Figure 8A) showcased several prominent research clusters centered around key contributors based in the United States, China, and Germany. These authors and institutions played pivotal roles in shaping the field’s scientific agenda and publishing output, particularly in oncology-focused and materials-science-based organoid systems. International collaboration analysis (

Figure 8B) further corroborated this dominance, with the United States and China being the two most central nodes. However, there is evidence of increasing engagement from countries such as the United Kingdom, Portugal, India, and Australia, reflecting a gradual shift towards broader participation. This expanding collaboration network is in line with trends observed in similar bibliometric studies on stem cell precision medicine and hydrogel-based organoid modelling[

48]. Notably, countries within South-East Asia, including Malaysia, remain underrepresented. This observation highlights an untapped opportunity for Malaysia and neighboring nations to participate more actively in international consortia, especially considering the growing availability of local research expertise in biomaterials, pharmacology, and tissue engineering.

The convergence of thematic clusters across the conceptual and collaborative maps illustrates how organoid-nanomedicine research has transitioned from exploratory innovation to focused application. Foundational tools such as hydrogels, 3D bioprinting, and patient-derived organoids have enabled this field to move from simple structural mimics to functionally validated platforms. Noteworthy is the alignment of emerging keywords like “immune checkpoint”, “photodynamic therapy”, and “RNA sequencing” with broader translational research goals. This reflects a growing integration of nanoparticles as both delivery and modulatory tools within immuno-oncology contexts, with organoids serving as high-throughput, human-relevant screening platforms[

49,

50]. In parallel, the application of organoids in nanotoxicology, particularly through studies involving silica, titanium dioxide, and nanoplastics suggests the platform’s growing utility in public health and environmental safety assessments[

51,

52]. These diverse use cases confirm that organoid-nanomedicine research is not only translationally robust but also socially and environmentally responsive.

This bibliometric analysis offers a comprehensive overview of the research landscape at the intersection of organoid and nanomedicine technologies over the past decade. The findings clearly demonstrate that this is a dynamic and interdisciplinary field experiencing rapid evolution, with growing global interest and increasing integration of molecular profiling, immunotherapy, and toxicological applications. In conclusion, the integration of nanomedicine with organoid systems represents not only a methodological innovation but a transformative research paradigm. Moving forward, stronger international collaboration, protocol standardization, and investment in molecular diagnostics infrastructure will be essential to ensure the clinical translation of findings from this promising field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.I.A.M.L. and R.I.A.M.L.; methodology, R.A.J.R.; validation, H.I.A.M.L. and M.N.S.; formal analysis, R.I.A.M.L.; investigation, R.A.J.R.; resources, Y.M.Y.; data curation, R.A.J.R. and Y.M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I.A.M.L.; writing—review and editing, R.A.J.R.; visualization, R.I.A.M.L.; supervision, H.I.A.M.L.; project administration, M.N.S.; funding acquisition, H.I.A.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, grant number FRGS/1/2023/SKK15/UCMI/02/1. The APC was waived by the publisher.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participant.

Data Availability Statement

The bibliometric data were retrieved from the Scopus database and are subject to Scopus licensing restrictions. Requests for access to the data may be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author’s contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Sarma, C. A Bibliometric Analysis of Nanomedicine Research from A Bibliometric Analysis of Nanomedicine Research from Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Sarma, Chinmay; 2009. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5333.

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, P.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Miao, Y. Global Trends and Hotspots in Research on Organoids between 2011 and 2020: A Bibliometric Analysis. Ann Palliat Med 2022, 11 (10), 3043–3062. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, D.; Ho, C. W.; Shan, D. Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research on Human Organoids. Heliyon 2024, 10 (6). [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Shao, A.; Zhou, W.; Lou, L.; Grzybowski, A.; Jin, K.; Ye, J. Retinogenesis in a Dish: Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of Retinal Organoids From 2011 to 2022. Cell Transplant 2023, 32. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, Y. H.; Gao, X.; Wang, H. Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, N.; Li, C. M.; Xiong, S. Q. Current Perspectives and Trends in Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems in Breast Cancer: Bibliometric Analysis and Review. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. Frontiers Media SA 2023. [CrossRef]

- Luo, B. Y.; Liu, K. Q.; Fan, J. S. Bibliometric Analysis of Cerebral Organoids and Diseases in the Last 10 Years. Ibrain. Wiley-VCH Verlag December 1, 2023, pp 431–445. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. M.; Yang, K. L.; Cui, Y. C.; Zhou, Y. S.; Zhang, H. R.; Wang, Q.; Ye, Y. J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, K. W. Current Trends and Research Topics Regarding Intestinal Organoids: An Overview Based on Bibliometrics. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. Frontiers Media S.A. August 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W. M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J Bus Res 2021, 133. [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J Informetr 2017, 11 (4). [CrossRef]

- De Bakker, F. G. A.; Groenewegen, P.; Den Hond, F. A Bibliometric Analysis of 30 Years of Research and Theory on Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Social Performance. Bus Soc 2005, 44 (3). [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organizational Research Methods. Goldsmiths Research Online 2015, 18 (3).

- Booth, A. Searching for Qualitative Research for Inclusion in Systematic Reviews: A Structured Methodological Review. Syst Rev 2016, 5 (1). [CrossRef]

- Larivière, V.; Desrochers, N.; Macaluso, B.; Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A.; Sugimoto, C. R. Contributorship and Division of Labor in Knowledge Production. Soc Stud Sci 2016, 46 (3). [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L.; Ju, Z.; Skonieczna, M.; Zhou, P. K.; Huang, R. Nanoparticles-Induced Potential Toxicity on Human Health: Applications, Toxicity Mechanisms, and Evaluation Models. MedComm. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L.; Luo, J.; Qu, C.; Guo, P.; Yi, W.; Yang, J.; Yan, Y.; Guan, H.; Zhou, P.; Huang, R. Predictive Metabolomic Signatures for Safety Assessment of Three Plastic Nanoparticles Using Intestinal Organoids. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 913. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. The Uses of 3D Human Brain Organoids for Neurotoxicity Evaluations: A Review. NeuroToxicology. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gong, H.; Jiang, S.; She, C.; Cao, Y. Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Decrease Neuronal NO Synthase in 3D Brain Organoids. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 748. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Yang, Z.; Cao, Y. The Cytotoxicity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles to 3D Brain Organoids Results from Excessive Intracellular Zinc Ions and Defective Autophagy. Cell Biol Toxicol 2023, 39 (1). [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y. The Uses of Transcriptomics and Lipidomics Indicated That Direct Contact with Graphene Oxide Altered Lipid Homeostasis through ER Stress in 3D Human Brain Organoids. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 849. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Feng, C.; Luo, D.; Zhao, R.; Kannan, P. R.; Yin, Y.; Iqbal, M. Z.; Hu, Y.; Kong, X. Metformin Hydrochloride Significantly Inhibits Rotavirus Infection in Caco2 Cell Line, Intestinal Organoids, and Mice. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16 (9). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, D.; Zhao, R.; Luo, D.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhuo, X.; Iqbal, M. Z.; Zhang, H.; Han, Q.; Kong, X. Spike Structure of Gold Nanobranches Induces Hepatotoxicity in Mouse Hepatocyte Organoid Models. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22 (1). [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Luo, D.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Iqbal, M. Z.; Kong, X. DOX-Loaded Hydroxyapatite Nanoclusters for Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Chemotherapy: Evaluation Based on the Cancer Cells and Organoids. SLAS Technol 2023, 28 (1). [CrossRef]

- Ebner-Peking, P.; Krisch, L.; Wolf, M.; Hochmann, S.; Hoog, A.; Vári, B.; Muigg, K.; Poupardin, R.; Scharler, C.; Schmidhuber, S.; Russe, E.; Stachelscheid, H.; Schneeberger, A.; Schallmoser, K.; Strunk, D. Self-Assembly of Differentiated Progenitor Cells Facilitates Spheroid Human Skin Organoid Formation and Planar Skin Regeneration. Theranostics 2021, 11 (17). [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Tiriac, H.; Sridharan, B. P.; Scampavia, L.; Madoux, F.; Seldin, J.; Souza, G. R.; Watson, D.; Tuveson, D.; Spicer, T. P. Advanced Development of Primary Pancreatic Organoid Tumor Models for High-Throughput Phenotypic Drug Screening. SLAS Discovery 2018, 23 (6). [CrossRef]

- Adine, C.; Ng, K. K.; Rungarunlert, S.; Souza, G. R.; Ferreira, J. N. Engineering Innervated Secretory Epithelial Organoids by Magnetic Three-Dimensional Bioprinting for Stimulating Epithelial Growth in Salivary Glands. Biomaterials 2018, 180. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. N.; Hasan, R.; Urkasemsin, G.; Ng, K. K.; Adine, C.; Muthumariappan, S.; Souza, G. R. A Magnetic Three-Dimensional Levitated Primary Cell Culture System for the Development of Secretory Salivary Gland-like Organoids. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2019, 13 (3). [CrossRef]

- Chansaenroj, A.; Adine, C.; Charoenlappanit, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Sariya, L.; Osathanon, T.; Rungarunlert, S.; Urkasemsin, G.; Chaisuparat, R.; Yodmuang, S.; Souza, G. R.; Ferreira, J. N. Magnetic Bioassembly Platforms towards the Generation of Extracellular Vesicles from Human Salivary Gland Functional Organoids for Epithelial Repair. Bioact Mater 2022, 18. [CrossRef]

- Rodboon, T.; Souza, G. R.; Mutirangura, A.; Ferreira, J. N. Magnetic Bioassembly Platforms for Establishing Craniofacial Exocrine Gland Organoids as Aging in Vitro Models. PLoS One 2022, 17 (8 August). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Souza, G. R.; Amato, R. J. 3D Organoids from Milligrams of Genitourinary Cancer Patients Tissue Retain Key Features of Original Tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 36 (6_suppl). [CrossRef]

- Chandra, L.; Borcherding, D. C.; Kingsbury, D.; Atherly, T.; Ambrosini, Y. M.; Bourgois-Mochel, A.; Yuan, W.; Kimber, M.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wannemuehler, M.; Ellinwood, N. M.; Snella, E.; Martin, M.; Skala, M.; Meyerholz, D.; Estes, M.; Fernandez-Zapico, M. E.; Jergens, A. E.; Mochel, J. P.; Allenspach, K. Derivation of Adult Canine Intestinal Organoids for Translational Research in Gastroenterology. BMC Biol 2019, 17 (1). [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Qi, Y.; Jergens, A.; Wannemuehler, M.; Barrett, T. A.; Wang, Q. Effects of Six Common Dietary Nutrients on Murine Intestinal Organoid Growth. PLoS One 2018, 13 (2). [CrossRef]

- Reding, B.; Carter, P.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wannemuehler, M.; Bratlie, K. M.; Wang, Q. Manipulate Intestinal Organoids with Niobium Carbide Nanosheets. J Biomed Mater Res A 2021, 109 (4). [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Qi, Y.; Rollins, D.; Bussiere, L. D.; Dhar, D.; Miller, C. L.; Yu, C.; Wang, Q. Rational Design of Oral Drugs Targeting Mucosa Delivery with Gut Organoid Platforms. Bioact Mater 2023, 30. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Rollins, D.; Qi, Y.; Fredericks, J.; Mansell, T. J.; Jergens, A.; Phillips, G. J.; Wannemuehler, M.; Wang, Q. TNFα Regulates Intestinal Organoids from Mice with Both Defined and Conventional Microbiota. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 164. [CrossRef]

- Kingsbury, D. D.; Sun, L.; Qi, Y.; Fredericks, J.; Wang, Q.; Wannemuehler, M. J.; Jergens, A.; Allenspach, K. Optimizing the Development and Characterization of Canine Small Intestinal Crypt Organoids as a Research Model. Gastroenterology 2017, 152 (5). [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Wong, K. Y.; Wiid, P.; Harding, A.; Giri, R.; Tong, W.; Creagh, J.; Begun, J.; McGuckin, M. A.; Hasnain, S. Z. Gut Microbiota Shape the Inflammatory Response in Mice with an Epithelial Defect. Gut Microbes 2021, 13 (1). [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, D.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Ong, Y. T.; Qu, Z.; Schreiber, V.; Begun, J.; Popat, A. Facile Synthesis of Dendrimer like Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles to Enhance Targeted Delivery of Interleukin-22. Biomater Sci 2021, 9 (22). [CrossRef]

- Pujara, N.; Giri, R.; Wong, K. Y.; Qu, Z.; Rewatkar, P.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Begun, J.; Ross, B. P.; McGuckin, M.; Popat, A. PH – Responsive Colloidal Carriers Assembled from β-Lactoglobulin and Epsilon Poly-L-Lysine for Oral Drug Delivery. J Colloid Interface Sci 2021, 589. [CrossRef]

- Giri, R.; Hoedt, E. C.; Khushi, S.; Salim, A. A.; Bergot, A. S.; Schreiber, V.; Thomas, R.; McGuckin, M. A.; Florin, T. H.; Morrison, M.; Capon, R. J.; Ó Cuív, P.; Begun, J. Secreted NF-ΚB Suppressive Microbial Metabolites Modulate Gut Inflammation. Cell Rep 2022, 39 (2). [CrossRef]

- Giri, R.; Cuiv, P. O.; Begun, J. Tu1852 - Role of Anti-Inflammatory Gut Bioactives in the Modulation of Immune Response in Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154 (6). [CrossRef]

- Giri, R.; Cuiv, P. O.; Begun, J. Mo1930 – Harnessing Anti-Inflammatory Gut Bioactives to Modulate the Immune Response in Ibd. Gastroenterology 2019, 156 (6). [CrossRef]

- Obaid, G.; Bano, S.; Mallidi, S.; Broekgaarden, M.; Kuriakose, J.; Silber, Z.; Bulin, A. L.; Wang, Y.; Mai, Z.; Jin, W.; Simeone, D.; Hasan, T. Impacting Pancreatic Cancer Therapy in Heterotypic in Vitro Organoids and in Vivo Tumors with Specificity-Tuned, NIR-Activable Photoimmunonanoconjugates: Towards Conquering Desmoplasia? Nano Lett 2019, 19 (11). [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Vega, V.; Hou, S.; Plenker, D.; Tiriac, H.; Baillargeon, P.; Shumate, J.; Scampavia, L.; Seldin, J.; Souza, G. R.; Tuveson, D. A.; Spicer, T. P. Lead Identification Using 3D Models of Pancreatic Cancer. SLAS Discovery 2022, 27 (3). [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, C.; Lee, R.; Paul, M. K. Emerging Role and Promise of Nanomaterials in Organoid Research. Drug Discovery Today. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, Z.; Peroutka-Bigus, N.; Bellaire, B.; Wannemuehler, M.; Barrett, T. A.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Intestinal Organoids Containing Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Biomed Mater Res A 2018, 106 (4). [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, Z.; Peroutka-Bigus, N.; Bellaire, B.; Jergens, A.; Wannemuehler, M.; Wang, Q. Gut Organoid as a New Platform to Study Alginate and Chitosan Mediated Plga Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Mar Drugs 2021, 19 (5). [CrossRef]

- Di Marzio, N.; Eglin, D.; Serra, T.; Moroni, L. Bio-Fabrication: Convergence of 3D Bioprinting and Nano-Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, E.; Mao, Y.; Luan, J.; Fu, S. A Bibliometric Analysis of Research on Decellularized Matrix for Two Decades. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2023, 29 (9). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Shang, L.; Zhao, Y. Microfluidics for Drug Development: From Synthesis to Evaluation. Chemical Reviews. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gugulothu, S. B.; Asthana, S.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S.; Chatterjee, K. Trends in Photopolymerizable Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting of Tumor Models. JACS Au. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Miloradovic, D.; Pavlovic, D.; Jankovic, M. G.; Nikolic, S.; Papic, M.; Milivojevic, N.; Stojkovic, M.; Ljujic, B. Human Embryos, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells, and Organoids: Models to Assess the Effects of Environmental Plastic Pollution. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Kumar, R.; Buragohain, L.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, M. Organoid Technology: A Reliable Developmental Biology Tool for Organ-Specific Nanotoxicity Evaluation. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).