Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetically heterogeneous and clinically variable rare neuromuscular disorder caused by homozygous mutations or deletions in the SMN1 gene, leading to deficiency of the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, degeneration of anterior horn cells, and progressive muscle weakness and atrophy [

1,

2]. It affects approximately 1–2 per 100,000 individuals globally, with carrier frequency estimated at 1 in 40–70 [

3]. SMA is now typically classified into Types 0 through IV, based on age of onset and maximum motor task achieved: Type 0 (prenatal onset), Type I (infantile, never sits), Type II (intermediate, sits but never walks), Type III (later onset, may walk), and Type IV (adult-onset, mild weakness) [

1,

4,

5,

6].

Historically, pain has not been considered a core feature of SMA. However, with the introduction of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) such as nusinersen, onasemnogene abeparvovec, and risdiplam since 2016–2019, survival and motor function have improved substantially across SMA types [

7,

8,

9,

10]. As patients live longer and gain partial mobility, secondary complications, including musculoskeletal discomfort, neuropathic symptoms, and procedural pain, have risen in prominence.

Emerging observational evidence indicates that pain affects between 40% and 80% of people with SMA, depending on age and phenotype [

11,

12]. Among Japanese patients with Types II and III, chronic pain prevalence is approximately 40%, with daily mild but persistent pain in the neck, back, and lower extremities, commonly exacerbated by sitting and physical activity [

11]. In a cohort of adolescents and adults, more than 80% reported intermittent mild-to-moderate pain, frequently localized to the lumbar spine, hips, or thoracic region, closely associated with depressive symptoms rather than directly with physical disability [

13]. A Swiss series demonstrated age-related differences: adolescents had highest pain prevalence (~62%), followed by adults (~48%), children aged 6–12 years (~32%) and children under 6 years (~9%) [

14].

Pain mechanisms in SMA are multifactorial [

15]. Musculoskeletal pain arises from scoliosis, joint contractures, hip subluxation, limited range of motion, and prolonged wheelchair use. Sensorimotor impairment in Types II and III further predisposes to mechanical strain and discomfort [

16]. While SMA is primarily a motor neuropathy, emerging data suggest sensory nerve alterations, especially in Type III, with abnormalities in cold pain thresholds and sensory nerve conduction metrics, indicating a potential neuropathic component in some patients [

16]. Procedural pain from repeated intrathecal injections and surgical interventions (e.g. spinal fusion) adds further complexity [

17,

18,

19], with emerging interventions such as epidural spinal cord stimulation introducing additional procedural considerations [

20]. Chronic nociceptive input may also drive central sensitization, amplifying pain perception over time.

The impact of pain extends beyond physical sensation, affecting mood, sleep, participation in rehabilitation, and overall quality of life [

21,

22]. Although reported mean pain intensity is generally low to moderate, there is strong evidence of correlation between pain and depressive symptoms in older patients with SMA and in pain patients in general [

23,

24]. Yet pain in SMA remains under-assessed in clinical practice, with limited use of standardized instruments and lack of SMA-specific pain protocols [

11,

13,

25].

This systematic review aims to comprehensively synthesize current peer-reviewed evidence on pain in SMA by examining its epidemiology across different disease types and age groups, while delineating the clinical pain phenotypes and their anatomical distribution. It further explores the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to pain, encompassing musculoskeletal, neuropathic, and procedural factors. In addition, the review evaluates the available pain assessment tools and outcome measures used in clinical and research settings and critically appraises the therapeutic approaches employed, including pharmacologic treatments, rehabilitative interventions, orthopedic procedures, and psychological management strategies. Finally, this review will identify gaps in knowledge and propose directions for future research, including the development of SMA-specific pain assessment instruments, longitudinal studies on pain trajectories in the era of SMN-modulator therapies, and interdisciplinary clinical guidelines to optimize patient-centered outcomes.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

26]. We performed comprehensive searches through six bibliographic databases or platforms: PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, to identify peer-reviewed publications addressing pain in SMA. Searches were last updated on June 1, 2025.

Search strategies combined controlled vocabulary (e.g. MeSH terms “spinal muscular atrophy”, “pain”, “musculoskeletal pain”, “neuropathic pain”) and free-text keywords (“SMA pain”, “SMA pain assessment”, “muscle pain SMA”, “spinal muscular atrophy pain”), using Boolean operators, proximity operators, and truncation as appropriate for each database. Google Scholar was searched using the broadest terms (“spinal muscular atrophy pain”) and limited to the first 500 results, screening titles and abstracts for relevance due to practicality.

Eligible publications included cross-sectional, cohort, case–control, interventional, and qualitative studies, as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, that reported epidemiological data, clinical characteristics, assessment tools, pathophysiological observations, or management strategies for pain in any SMA type. Exclusion criteria comprised conference abstracts without full text, non-English language publications, animal or in vitro studies, and articles focusing solely on motor function without mention of pain.

All retrieved citations were imported into EndNote and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (GF, MLGL) screened titles and abstracts for potential inclusion. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were then assessed independently. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or adjudication by a third senior reviewer (GV).

Data extraction was performed using a standardized form capturing: study design, SMA type(s) studied, sample size, demographic characteristics, pain prevalence and intensity, anatomical distribution, pain assessment instruments, proposed mechanisms, and intervention strategies.

Extracted quantitative data on pain prevalence, frequency, and intensity were tabulated and, where appropriate, synthesized narratively and via descriptive statistics (means, medians, percentages). Statistical analyses and weighted prevalence calculations were performed using standard epidemiological formulas, with confidence intervals calculated using the Wilson score method for proportions. The analyses were conducted in R software v4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria,

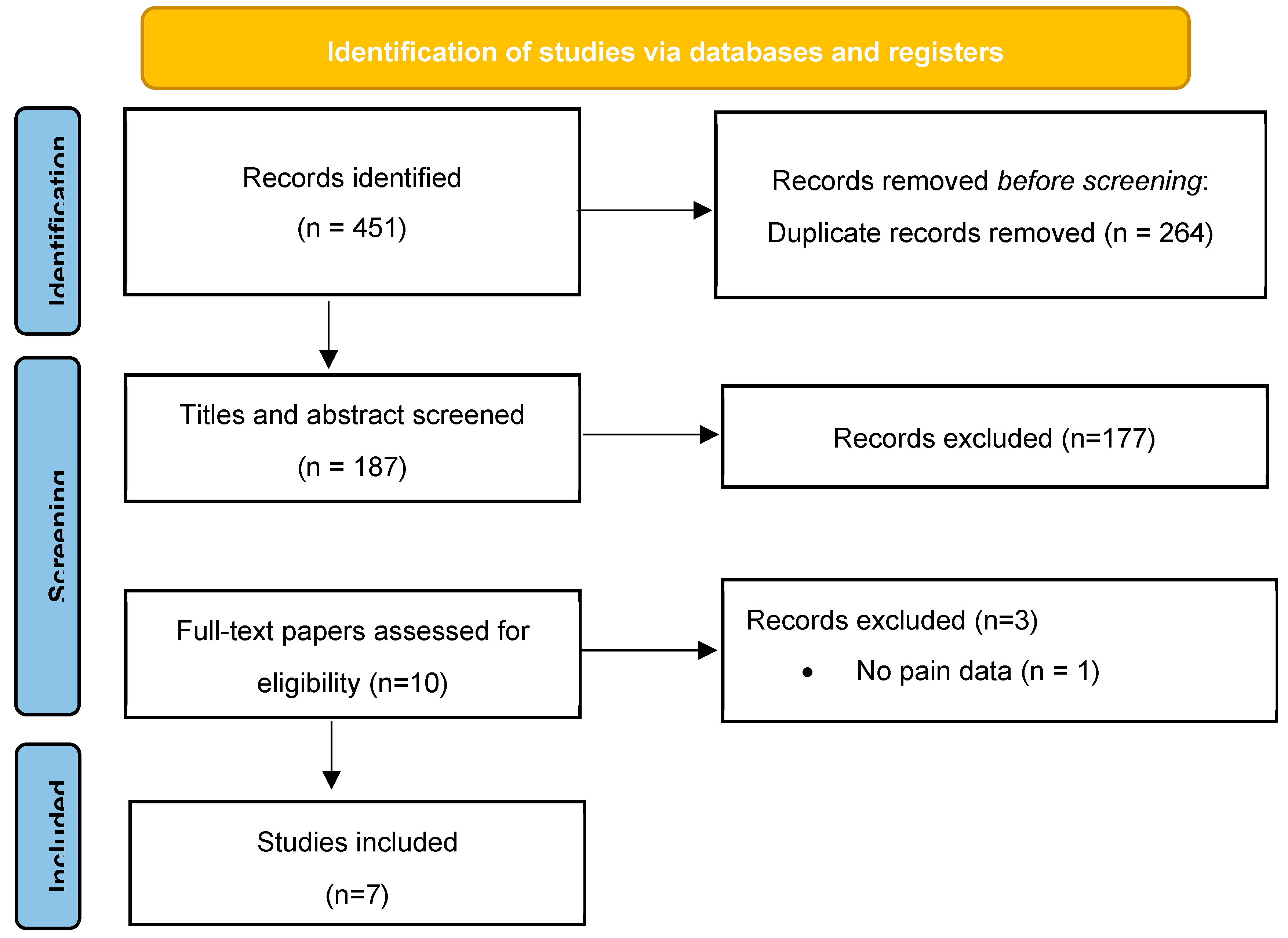

www.r-project.org). Given the limited number of studies, considerable heterogeneity in study designs, populations, outcome measures, and predominantly observational nature of the evidence, formal meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, findings were organized thematically across the following domains: epidemiology by SMA type and age, clinical phenotypes of pain (e.g. musculoskeletal, neuropathic, procedural), assessment and measurement tools, underlying pathophysiology, and management approaches. Where possible, subgroup comparisons across SMA types (e.g. Type II vs Type III), and age strata (children, adolescents, adults) were delineated. The methods were registered prospectively with PROSPERO (Registration no. CRD420251118178), and reporting adheres to PRISMA 2020 checklist to ensure transparency and reproducibility. A comprehensive database search yielded 451 records. After removal of 264 duplicate entries, 187 records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 177 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 10 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, leading to the exclusion of three studies (one lacking pain-related data and two classified as reviews or editorials). A total of seven studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were included in the final qualitative analysis (

Figure 1).

Epidemiology of Pain in SMA

Pain is a frequent and clinically relevant symptom in SMA, often underrecognized in clinical practice despite its substantial impact on patient quality of life. With the advent of DMTs, patients with SMA are experiencing prolonged survival and improved motor function. Consequently, the burden of pain is increasingly reported and systematically assessed. A 2024 Swiss registry-based study evaluating children, adolescents, and adults with SMA demonstrated that chronic pain persisting for more than three months affected 62% of adolescents, 48% of adults, 39% of children aged 6–12 years, and 10% of those younger than six years, highlighting a clear age-dependent increase in pain prevalence [

14]. Similar prevalence rates have been observed when stratifying by SMA type: 40.6% in Type II and 40.9% in Type III, suggesting that intermediate phenotypes are particularly susceptible to chronic pain [

11]. In a focused cohort of ambulant adult patients with Type III SMA, 55% reported clinically significant nociceptive pain, which was objectively assessed through pressure algometry and myotonometry. This pain was predominantly attributed to musculoskeletal imbalance arising from chronic motor neuron loss and progressive muscle weakness [

27]. Furthermore, a broader multi-center cohort study indicated that up to 80% of SMA patients experienced intermittent pain episodes occurring at least weekly, underscoring its chronic and recurrent nature [

13]. Additional studies corroborate these findings. Dunaway et al. [

28] reported that nearly half of pediatric and adult SMA patients experienced daily pain, primarily in the hips and lower back, contributing to functional limitations and decreased participation in physical therapy. Similarly, a different group of research identified chronic musculoskeletal discomfort in 55% of adult SMA patients, frequently associated with scoliosis and joint contractures [

29].

Clinical Phenotypes of Pain

Although the intensity of pain in SMA is typically reported as low to moderate, it is frequently persistent, occurring on a daily basis and often exerting a long-term impact on patients’ functional status (

Table 1). Commonly affected anatomical regions include the lower extremities, hips, back, and neck [

11]. In a retrospective survey involving 104 SMA patients, hip pain was identified in 58% of respondents, with 14% experiencing moderate-to-severe intensity, as reflected by a mean modified Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) score of 2.1 ± 2.3 [

25]. Pain was reported to interfere significantly with activities of daily living, including prolonged sitting, patient transfers, and sleep quality [

25]. Factors independently associated with higher odds of experiencing moderate-to-severe pain included obesity (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 5.4), the presence of hip contractures (aOR 3.2), hip dislocations (aOR 2.9), and prior surgical interventions for scoliosis correction (aOR 2.6) [

25].

The underlying mechanisms of pain in SMA are predominantly musculoskeletal, involving scoliosis, progressive joint contractures, hip subluxations, muscular imbalance, and complications arising from long-term wheelchair dependence [

27]. These secondary biomechanical alterations are consequences of chronic motor neuron degeneration and muscular atrophy. However, despite these observations, the current literature remains sparse in addressing the pathophysiological differentiation between nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain components in SMA patients. Understanding this differentiation is crucial for guiding mechanism-based analgesic strategies but has been largely neglected in clinical research. In fact, emerging evidence points toward a possible neuropathic component. Sensory testing and nerve conduction studies in animals with SMA Types II and III have revealed subtle sensory deficits, suggesting peripheral nerve involvement and altered nociceptive signaling [

30]. This is supported by preclinical findings: in a mild SMA mouse model, deficiency of SMN protein resulted in dorsal root ganglion neuron hyperexcitability, upregulation of voltage-gated sodium channels (Na_v1.7 and Na_v1.8), and increased norepinephrine levels, collectively leading to heightened mechanical pain sensitivity [

30]. These results implicate peripheral sensitization as a contributing factor to SMA-related pain, bridging the gap between purely musculoskeletal nociceptive pain and potential neuropathic mechanisms.

Despite these advances, robust human studies dissecting the relative contributions of nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain phenotypes are lacking. Existing clinical trials and observational studies often report pain as a secondary outcome, without employing standardized neuropathic pain screening tools (e.g., DN4, painDETECT) or advanced neurophysiological assessments. Consequently, the prevalence of neuropathic or centrally mediated (nociplastic) pain in SMA remains unknown. Addressing this knowledge gap through comprehensive neurophysiological, imaging, and biomarker-driven investigations will be pivotal for developing personalized, mechanism-targeted pain management approaches in SMA patients [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Even if the number of SMA patients is low, they deserve an optimal, personalized treatment, in order to alleviate their suffering.

Pooled analysis of 7 included studies (

Table 1) reporting quantitative pain prevalence (total n = 599) revealed substantial variability in pain rates. The weighted overall prevalence was 48.7% (95% CI: 44.6-52.8), though this masks important age-related differences: 10% in children <6 years, 39% in children 6-12 years, 62% in adolescents, and 48-80% in adults. High heterogeneity (I² = 86.3%) reflects differences in pain definitions, assessment methods, and patient populations. Limited type-specific data from a single study (n=135) reported similar prevalences for Type II (40.6%, 95% CI: 32.2-49.5) and Type III (40.9%, 95% CI: 29.0-53.6). Collectively, these data indicate that pain is a highly prevalent and clinically significant manifestation of SMA, particularly in patients with longer disease duration and intermediate phenotypes.

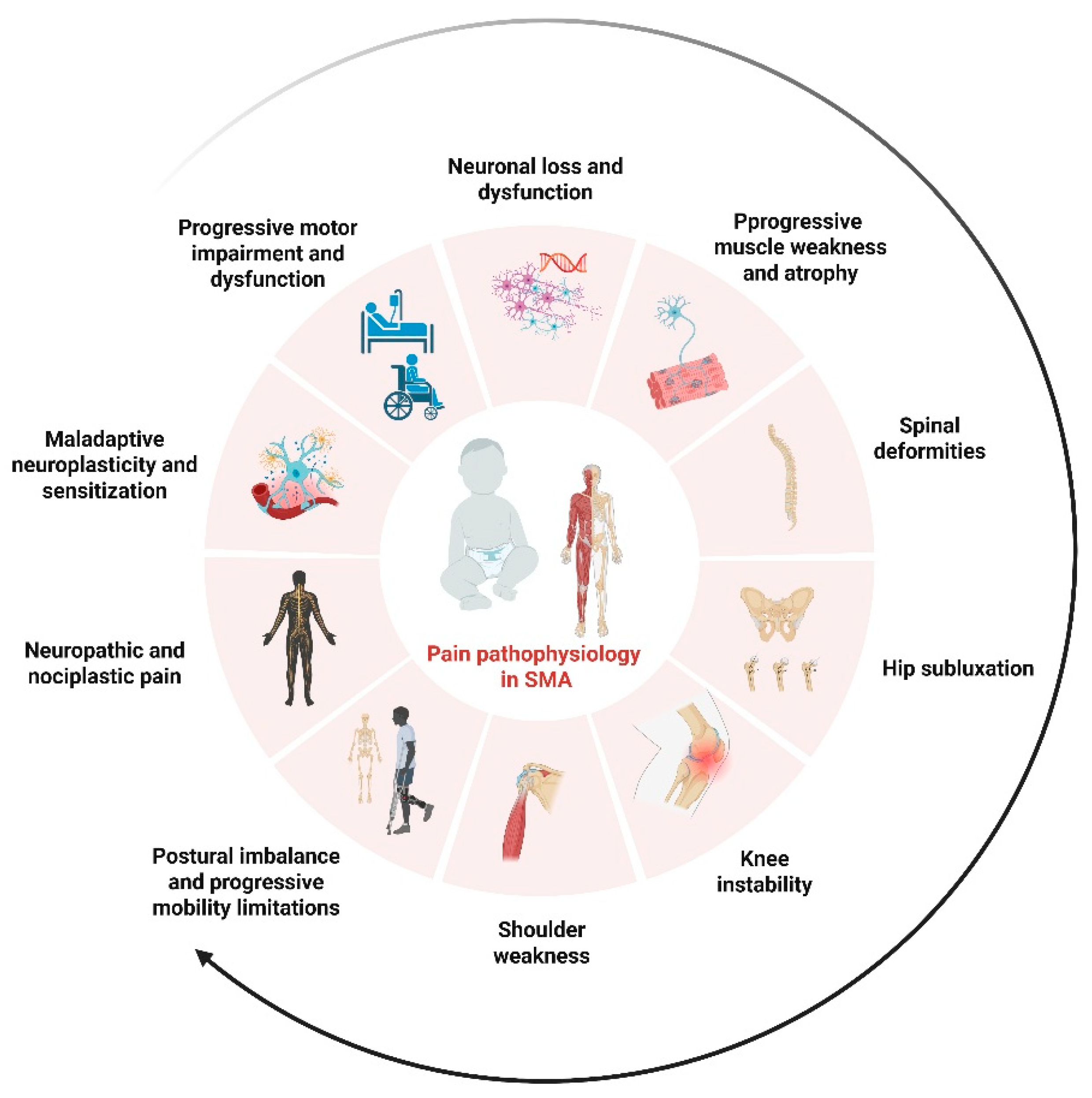

Underlying Pathophysiology

The mechanisms driving pain in SMA are complex and multifactorial. Traditionally viewed as a pure motor neuronopathy, SMA is increasingly recognized to involve sensory neuronal dysfunction and peripheral nociceptive alterations. Musculoskeletal factors, spinal deformities, joint contractures, hip subluxations, and postural imbalance, predominate in clinical descriptions, but emerging evidence suggests contributions from neuropathic and nociplastic mechanisms as well.

Biomechanical strain resulting from progressive muscle weakness and motor neuron degeneration leads to compensatory skeletal and soft tissue alterations that can initiate persistent nociceptive input. Osteoarticular changes, particularly hip instability and scoliosis, generate chronic mechanical stress on joints and soft tissues, driving pain that is typically classified as nociceptive. In contrast, the involvement of sensory pathways in SMA is now supported by human and preclinical studies. A recent case series of sensory dysfunction in SMA Types II and III revealed electrophysiological abnormalities consistent with sensory fiber impairment, raising the possibility that peripheral neuropathic mechanisms contribute to pain in a subset of patients [

16]. In fact, as previously cited, in murine models of mild SMA, dorsal root ganglion neurons exhibited hyperexcitability, with upregulation of Na_v1.7 and Na_v1.8 sodium channels, increased NF-κB activity, and elevated norepinephrine levels. These molecular alterations produced mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia, consistent with peripheral sensitization [

30]. Sensory–motor circuit disruption may further complicate pain pathways. Mouse and human studies have documented impaired proprioceptive synapses on motor neurons, indicating that sensory afferent dysfunction is a conserved and possibly pain-relevant pathogenic event in SMA [

48]. Nevertheless, the literature remains sparse with respect to quantitative human sensory testing, microneurography, or skin biopsy data that would delineate specific neuropathic or nociplastic pain phenotypes. Moreover, central sensitization processes, such as maladaptive spinal dorsal horn plasticity, have not yet been studied in SMA patients, despite their recognized role in chronic pain syndromes more broadly. Epigenetic modulation of pain pathways, including histone modifications in dorsal horn neurons, remains an unexplored domain in SMA-related pain research.

The complex and multifactorial contributors to pain in SMA are illustrated in

Figure 2, which summarizes the interplay between musculoskeletal, neuronal, and central mechanisms involved in its pathophysiology.

In summary, the limited but intriguing evidence suggests a spectrum of pain pathophysiology in SMA: predominantly nociceptive pain from musculoskeletal derangements, potential neuropathic pain owing to sensory neuron dysfunction and peripheral sensitization, and yet-to-be-characterized nociplastic or central pain contributions. Addressing these knowledge gaps with comprehensive neurophysiological, imaging, and molecular biomarker studies will be essential to inform mechanism-targeted pain management strategies in the era of longer survival and improved motor function.

Management Approaches

Effective pain management in SMA requires an individualized and multidisciplinary approach, targeting the nociceptive, neuropathic, and functional components that underlie patient discomfort. Although no standardized pain management guidelines specific to SMA currently exist, the broader principles of pediatric and adult neuromuscular pain management, as defined in recent SMA care recommendations, can be adapted to this unique population [

49].

Pharmacologic Management

Analgesic regimens are primarily oriented toward nociceptive musculoskeletal pain. Non-opioid agents such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may mitigate low-to-moderate intensity pain arising from structural imbalances, contractures, or spinal deformities. In cases of neuropathic pain, suggested by sensory testing or pain phenotypes resembling radiculopathy, gabapentinoids (e.g. gabapentin, pregabalin) can be considered, although no randomized trials exist in SMA populations. Limited observational data report symptomatic relief with gabapentin in SMA Type II adults with evidence of small fiber involvement [

50]. Opioid analgesics are reserved for refractory or severe pain, such as postoperative discomfort from spinal fusion; long-term use is avoided due to concerns about tolerance and respiratory depression in SMA patients [

11,

12,

13,

51].

Non-Pharmacologic and Rehabilitation Approaches

Physical therapy is foundational to pain prevention and management. A recent review of physiotherapy and respiratory rehabilitation in SMA emphasizes tailored programs incorporating range-of-motion exercises, postural training, contracture prevention, and assistive device optimization to mitigate biomechanical stress and secondary musculoskeletal pain [

50]. Seating posture optimization and ergonomics are important in adolescents and adults to minimize pressure points and hip discomfort. Patients with SMA Type III/IV may benefit from low-intensity resistance training or aquatic therapy to preserve muscle balance without overloading weakened musculature [

52].

Orthopedic and Interventional Strategies

Orthopedic interventions, including bracing, scoliosis correction, and hip stabilization surgery, often aim to improve function but may also ameliorate pain by realigning skeletal structures and reducing joint stress. Postoperative or interventional anesthesia in SMA patients poses peculiar challenges; avoidance of depolarizing muscle relaxants is recommended, with regional or spinal anesthesia preferred to minimize perioperative pain and complications [

53,

54].

Psychological and Behavioral Interventions

Chronic pain in SMA can impair mood, sleep, and rehabilitation adherence [

54]. Evidence from chronic pain populations supports the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based stress reduction, and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). While SMA-specific trials are lacking, these modalities may enhance coping, reduce pain-related disability, and improve psychological resilience [

55].

Role of Disease-Modifying Therapies

Although SMN-targeting therapies (such as nusinersen, risdiplam, and onasemnogene abeparvovec) principally address motor function and survival, they may indirectly reduce pain by preserving muscle bulk and reducing secondary orthopedic complications. However, data on whether DMTs directly improve pain are absent; future longitudinal studies are required to assess their impact on pain trajectories.

To illustrate the comprehensive and interdisciplinary nature of pain management in SMA,

Figure 3 presents a schematic overview of pharmacologic, non-pharmacologic, orthopedic, psychological, and disease-modifying strategies integrated across the patient care.

In summary, pain management in SMA is best approached via multidisciplinary coordination, integrating targeted pharmacotherapy, preventive and rehabilitative measures, orthopedic optimization, psychological support, and careful perioperative planning. Further research should establish SMA-specific pain protocols, particularly to delineate nociceptive versus neuropathic or nociplastic profiles and inform mechanism-driven therapeutic trials.

Study Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological heterogeneity of included studies presented significant challenges for standardized quality assessment. Our review encompassed diverse study designs including cross-sectional surveys, longitudinal cohort studies, retrospective chart reviews, secondary analyses of clinical trial data, and patient registry reports, each with fundamentally different methodological frameworks and quality indicators. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, while appropriate for traditional observational studies, could not be uniformly applied across this heterogeneous evidence base. For instance, registry-based studies [

14,

27] have different quality considerations than questionnaire surveys [

11] or secondary analyses of motor function trials [

28]. Rather than imposing inappropriate quality metrics, we conducted a narrative assessment of methodological strengths and limitations specific to each study design. Key quality indicators considered included: (1) use of validated pain assessment instruments versus non-standardized questionnaires, (2) completeness of pain phenotype characterization (anatomical location, intensity, frequency, quality), (3) sample size and representativeness of the SMA population studied, (4) adjustment for relevant confounders such as age, SMA type, and DMTs and (5) transparency in reporting missing data and non-response rates. Notably, only 3 of the studies employed validated pain scales (VAS, NRS, or modified BPI), while the majority relied on study-specific questionnaires without established psychometric properties. No studies utilized neuropathic pain screening tools despite emerging evidence of sensory nerve involvement. This methodological variability, while limiting quantitative synthesis, reflects the exploratory nature of pain research in SMA and underscores the urgent need for standardized, disease-specific pain assessment protocols in future studies.

Discussion

This systematic review highlights that pain is a prevalent and clinically meaningful manifestation of SMA, particularly in patients with intermediate phenotypes and longer disease duration. The reported prevalence of chronic pain, ranging from 40% to 80% in different studies [

11,

12,

13,

14,

27,

28,

29], underscores its relevance as a comorbidity that impairs functional independence and quality of life. Pain is predominantly nociceptive, driven by musculoskeletal complications such as scoliosis, hip subluxation, and joint contractures resulting from progressive motor neuron degeneration [

27]. However, emerging evidence suggests that neuropathic and potentially nociplastic mechanisms may also contribute to pain pathogenesis in SMA patients [

16,

30,

48]. These findings are broadly consistent with literature on other neuromotor disorders, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), where musculoskeletal pain similarly dominates the clinical picture due to prolonged wheelchair use, contractures, and abnormal biomechanics [

57,

58]. In ALS, neuropathic pain components have been identified through sensory testing and quantitative sensory thresholds, paralleling the subtle sensory deficits observed in SMA Types II and III [

16]. Despite these similarities, pain assessment in SMA remains poorly standardized and significantly underexplored compared to DMD and ALS, where validated pain questionnaires and neuropathic screening tools have been increasingly incorporated in clinical studies [

59,

60].

This review also highlights substantial methodological limitations in the current body of evidence. Pain is frequently reported as a secondary outcome, without detailed phenotypic classification into nociceptive, neuropathic, or nociplastic subtypes. Few studies have applied validated neuropathic pain instruments (e.g., DN4, painDETECT) or objective neurophysiological assessments such as microneurography or QST [

35,

39,

40,

41]. Furthermore, the paucity of longitudinal studies precludes understanding of how pain evolves over time, particularly in the context of DMTs. In fact, only preliminary evidence suggests differential effects of DMTs on pain outcomes. Hagenacker et al. [

31] reported pain reduction in 23% of adults receiving nusinersen, though this was not a primary endpoint of the study. The mechanism may involve both direct neuroprotective effects and indirect benefits through improved positioning and reduced contractures. However, prospective studies with standardized pain assessments are urgently needed to quantify these effects and identify predictors of pain response to DMTs.

The limited number of SMA-specific tools to assess pain interference and its impact on daily functioning represents another critical gap [

11,

35,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. In comparison to other neuromotor conditions, research on SMA pain mechanisms and management is notably less advanced. While multidisciplinary approaches integrating pharmacological, rehabilitative, orthopedic, and psychological strategies are recommended [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55], their efficacy has not been rigorously evaluated in SMA-specific trials. This lack of evidence impedes development of tailored clinical guidelines.

Clinical Implications

Based on this systematic review, several clinical recommendations emerge that can enhance pain management in patients with SMA. Routine pain screening using validated assessment tools should be implemented for all SMA patients, with periodic reassessment to monitor changes over time. Given the high reported prevalence of pain, ranging from 40% to 80%, clinicians should remain vigilant, particularly in non-verbal or younger individuals who may struggle to express or localize pain. Importantly, assessments should aim to distinguish between nociceptive and neuropathic pain components to guide mechanism-based therapeutic strategies. The incorporation of multidisciplinary pain management teams, comprising pain specialists, physiotherapists, and psychologists, into routine SMA care is strongly recommended to ensure a comprehensive and personalized approach. Lastly, future clinical trials evaluating DMTs for SMA should incorporate standardized pain measures as secondary outcomes to better understand the impact of these interventions on patient quality of life.

Future Research Priorities

This review highlights several key areas that warrant future research to advance pain management in SMA. First, there is an urgent need for the development and validation of SMA-specific pain assessment tools capable of capturing both nociceptive and neuropathic components. Longitudinal cohort studies are also essential to understand the evolution of pain trajectories from the time of diagnosis through the initiation and maintenance of disease-modifying therapies. Randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy and safety of specific pain interventions in SMA populations are notably lacking and should be prioritized. Additionally, identifying reliable biomarkers for pain phenotyping and for monitoring treatment response would enable more targeted and personalized approaches. Qualitative studies are needed to capture patient and caregiver perspectives on the impact of pain and their preferences for management strategies. Finally, health economic evaluations of integrated, multidisciplinary pain management programs in SMA could provide valuable insights into their cost-effectiveness and inform healthcare policy decisions.

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting its findings. First, the available literature on pain in SMA is limited both in volume and methodological rigor. Most studies included in this review report pain as a secondary outcome rather than a primary endpoint, resulting in heterogeneous and often incomplete data on pain prevalence, characteristics, and management. Consequently, the synthesis of results is primarily descriptive and lacks the robustness needed for quantitative meta-analysis. Second, there is a paucity of research specifically addressing the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying pain in SMA. Few studies have employed standardized tools to differentiate between nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain phenotypes, and objective neurophysiological assessments, such as QST, microneurography, or advanced imaging modalities, have rarely been conducted. This limitation restricts our ability to draw firm conclusions regarding the mechanistic basis of pain in this population. Third, significant variability exists across studies in terms of patient demographics, SMA types, age groups, and DMTs. Many studies include mixed cohorts without stratification by phenotype or treatment exposure, making it challenging to assess how these factors influence pain prevalence or intensity. Furthermore, most available data are derived from small sample sizes, retrospective designs, or registry-based analyses, which are susceptible to selection bias and underreporting of pain symptoms. Fourth, there is a lack of SMA-specific validated pain assessment instruments. Some studies rely on generic tools such as the VAS or BPI, which may not adequately capture pain phenotypes or functional interference unique to SMA patients. This limitation hampers accurate pain characterization and cross-study comparability. Finally, the review may be affected by publication bias, as studies reporting negative or nonsignificant findings regarding pain in SMA may be less likely to be published. The inclusion of only peer-reviewed articles in English may have further limited the scope of evidence retrieved. Overall, these limitations highlight the urgent need for high-quality, prospective studies with standardized, disease-specific pain assessments and mechanistic investigations to advance understanding and management of pain in SMA.

Conclusion

This review identifies pain as a major, yet insufficiently addressed, aspect of SMA. The literature remains scarce regarding its underlying pathophysiology, differentiation of pain phenotypes, and validated measurement tools. Future research should focus on mechanism-based investigations employing advanced neurophysiological and imaging methods, standardized pain assessments, and well-designed interventional trials. Such efforts are critical for developing targeted pain management protocols and improving the long-term quality of life for individuals with SMA. The evolving landscape of SMA treatment with DMTs has paradoxically revealed pain as an emergent clinical priority. As patients survive longer with improved motor function, comprehensive pain management becomes essential for optimizing quality of life. This review provides a foundation for developing evidence-based clinical pathways and highlights the urgent need for prospective, multicenter studies using standardized pain assessment protocols. Only through such concerted efforts we can transform pain from an overlooked comorbidity to a systematically addressed component of comprehensive SMA care.

List of Abbreviations

ACT - Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

aOR - Adjusted Odds Ratio

BPI - Brief Pain Inventory

CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

CBT - Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CI - Confidence Interval

DMD - Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

DMT - Disease-Modifying Therapy

DN4 - Douleur Neuropathique 4 (Neuropathic Pain in 4 Questions)

EIM - Electrical Impedance Myography

fMRI - Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

HFMS - Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale

HFMSE - Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded

mBPI - Modified Brief Pain Inventory

MeSH - Medical Subject Headings

NF-κB - Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

NPS - Neuropathic Pain Scale

NRS - Numeric Rating Scale

NSAIDs - Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

PRISMA - Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

QST - Quantitative Sensory Testing

RHS - Revised Hammersmith Scale

SMA - Spinal Muscular Atrophy

SMAIS-UL - SMA Independence Scale–Upper Limb Module

SMN - Survival Motor Neuron

SMN1 - Survival Motor Neuron 1 (gene)

VAS - Visual Analog Scale

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V.; methodology, M.L.G.L.; software and formal analysis, G.V., M.L.G.L.; data curation, M.L.G.L; writing-original draft preparation, G.V., G.F.; writing-review and supervision, A.A.A.A, S.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The PROSPERO registration (CRD42025111878) provides additional methodological details.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Fondazione Paolo Procacci for the support in the publication process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, Wirth B, Montes J, Main M, Mazzone ES, Vitale M, Snyder B, Quijano-Roy S, Bertini E, Davis RH, Meyer OH, Simonds AK, Schroth MK, Graham RJ, Kirschner J, Iannaccone ST, Crawford TO, Woods S, Qian Y, Sejersen T; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: Recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Feb;28(2):103-115. [CrossRef]

- Bagga P, Singh S, Ram G, Kapil S, Singh A. Diving into progress: a review on current therapeutic advancements in spinal muscular atrophy. Front Neurol. 2024 May 24;15:1368658. [CrossRef]

- Song W, Ke X. Rehabilitation management for patients with spinal muscular atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025 Jul 10;20(1):352. [CrossRef]

- Dubowitz, V. Chaos in the classification of SMA: a possible resolution. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995 Jan;5(1):3-5. [CrossRef]

- Dubowitz, V. Very severe spinal muscular atrophy (SMA type 0): an expanding clinical phenotype. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 1999;3(2):49-51. [CrossRef]

- Prior TW, Leach ME, Finanger EL. Spinal Muscular Atrophy. 2000 Feb 24 [updated 2024 Sep 19]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2025. [PubMed]

- Cobben JM, Lemmink HH, Snoeck I, Barth PA, van der Lee JH, de Visser M. Survival in SMA type I: a prospective analysis of 34 consecutive cases. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008 Jul;18(7):541-4. [CrossRef]

- Berglund A, Berkö S, Lampa E, Sejersen T. Survival in patients diagnosed with SMA at less than 24 months of age in a population-based setting before, during and after introduction of nusinersen therapy. Experience from Sweden. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2022 Sep;40:57-60. [CrossRef]

- Lejman J, Panuciak K, Nowicka E, Mastalerczyk A, Wojciechowska K, Lejman M. Gene Therapy in ALS and SMA: Advances, Challenges and Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 6;24(2):1130. [CrossRef]

- Reilly A, Chehade L, Kothary R. Curing SMA: Are we there yet? Gene Ther. 2023 Feb;30(1-2):8-17. [CrossRef]

- Uchio Y, Kajima K, Suzuki H, Nakamura K, Saito M, Ikai T. Pain in Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Questionnaire Study. Phys Ther Res. 2022;25(3):150-155. [CrossRef]

- Sagerer E, Wirner C, Schoser B, Wenninger S. Nociceptive pain in adult patients with 5q-spinal muscular atrophy type 3: a cross-sectional clinical study. J Neurol. 2023 Jan;270(1):250-261. [CrossRef]

- Keipert LM, Wurster CD, Uzelac Z, Dorst J, Schuster J, Wollinsky K, Ludolph A, Lulé D. Pain in adult and adolescent patients with 5q-associated Spinal Muscular Atrophy - an often underrated phenomenon. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2025 May 21:22143602251325773. [CrossRef]

- Steiner L, Tscherter A, Henzi B, Branca M, Carda S, Enzmann C, Fluss J, Jacquier D, Neuwirth C, Ripellino P, Scheidegger O, Schlaeger R, Schreiner B, Stettner GM, Klein A; Swiss-Reg-NMD Group. Chronic Pain in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Switzerland: A Query to the Spinal Muscular Atrophy Registry. J Clin Med. 2024 May 9;13(10):2798. [CrossRef]

- Hanna RB, Nahm N, Bent MA, Sund S, Patterson K, Schroth MK, Halanski MA. Hip Pain in Nonambulatory Children with Type-I or II Spinal Muscular Atrophy. JB JS Open Access. 2022 Sep 14;7(3):e22.00011. [CrossRef]

- Koszewicz M, Ubysz J, Dziadkowiak E, Wieczorek M, Budrewicz S. Sensory dysfunction in SMA type 2 and 3 - adaptive mechanism or concomitant target of damage? Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024 Sep 3;19(1):321. [CrossRef]

- Haché M, Swoboda KJ, Sethna N, Farrow-Gillespie A, Khandji A, Xia S, Bishop KM. Intrathecal Injections in Children With Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Nusinersen Clinical Trial Experience. J Child Neurol. 2016 Jun;31(7):899-906. [CrossRef]

- Brusa C, Baranello G, Ridout D, de Graaf J, Manzur AY, Munot P, Sarkozy A, Main M, Milev E, Iodice M, Ramsey D, Tucker S, Ember T, Nadarajah R, Muntoni F, Scoto M. Secondary outcomes of scoliosis surgery in disease-modifying treatment-naïve patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 2 and nonambulant type 3. Muscle Nerve. 2024 Nov;70(5):1000-1009. [CrossRef]

- Lee HS, Lee H, Lee YM, Kim S. Considerations for repetitive intrathecal procedures in long-term nusinersen treatment for non-ambulatory spinal muscular atrophy. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 12;15(1):8553. [CrossRef]

- Prat-Ortega G, Ensel S, Donadio S, Borda L, Boos A, Yadav P, Verma N, Ho J, Carranza E, Frazier-Kim S, Fields DP, Fisher LE, Weber DJ, Balzer J, Duong T, Weinstein SD, Eliasson MJL, Montes J, Chen KS, Clemens PR, Gerszten P, Mentis GZ, Pirondini E, Friedlander RM, Capogrosso M. First-in-human study of epidural spinal cord stimulation in individuals with spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Med. 2025 Apr;31(4):1246-1256. [CrossRef]

- Şen AD, Uğur Ö, Yarar C, Carman KB. Pain in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 2 and Type 3 Patients. Osmangazi Tıp Dergisi. 2025;47(1):16-21. [CrossRef]

- Hertel E, Rathleff MS, Straszek CL, Holden S, Petersen KK. The Impacts of Poor Sleep Quality on Knee Pain and Quality of Life in Young Adults: Insights From a Population-based Cohort. Clin J Pain. 2025 Jun 1;41(6):e1283. [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu Z, Sönmez Kurukaya S, Uluğ F, Dilek TD, Zindar Y, Arslan B, Tayşi B, Anaç E, Balkanas M, Kesik S, Sak K, Demirel ÖF, Doğangün B, Saltık S. Quality of Life, Caregiver Burden, and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in Parents of Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Comparison with Healthy Controls. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025 May 21;61(5):930. [CrossRef]

- Zis P, Daskalaki A, Bountouni I, Sykioti P, Varrassi G, Paladini A. Depression and chronic pain in the elderly: links and management challenges. Clin Interv Aging. 2017 Apr 21;12:709-720. [CrossRef]

- Xu AL, Crawford TO, Sponseller PD. Hip Pain in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Prevalence, Intensity, Interference, and Factors Associated With Moderate to Severe Pain. J Pediatr Orthop. 2022 May-Jun 01;42(5):273-279. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Pitarch-Castellano I, Hervás D, Cattinari MG, Ibáñez Albert E, López Lobato M, Ñungo Garzón NC, Rojas J, Puig-Ram C, Madruga-Garrido M. Pain in Children and Adolescents with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Longitudinal Study from a Patient Registry. Children (Basel). 2023 Nov 30;10(12):1880. [CrossRef]

- Dunaway Young S, Montes J, Kramer SS, Marra J, Salazar R, Cruz R, Chiriboga CA, Garber CE, De Vivo DC. Six-minute walk test is reliable and valid in spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2016 Nov;54(5):836-842. [CrossRef]

- Sansone VA, Coratti G, Pera MC, Pane M, Messina S, Salmin F, Albamonte E, De Sanctis R, Sframeli M, Di Bella V, Morando S, d'Amico A, Frongia AL, Antonaci L, Pirola A, Pedemonte M, Bertini E, Bruno C, Mercuri E; Italian ISMAC group. Sometimes they come back: New and old spinal muscular atrophy adults in the era of nusinersen. Eur J Neurol. 2021 Feb;28(2):602-608. [CrossRef]

- Qu R, Yao F, Zhang X, Gao Y, Liu T, Hua Y. SMN deficiency causes pain hypersensitivity in a mild SMA mouse model through enhancing excitability of nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons. Sci Rep. 2019 Apr 24;9(1):6493. [CrossRef]

- Hagenacker T, Wurster CD, Günther R, Schreiber-Katz O, Osmanovic A, Petri S, Weiler M, Ziegler A, Kuttler J, Koch JC, Schneider I, Wunderlich G, Schloss N, Lehmann HC, Cordts I, Deschauer M, Lingor P, Kamm C, Stolte B, Pietruck L, Totzeck A, Kizina K, Mönninghoff C, von Velsen O, Ose C, Reichmann H, Forsting M, Pechmann A, Kirschner J, Ludolph AC, Hermann A, Kleinschnitz C. Nusinersen in adults with 5q spinal muscular atrophy: a non-interventional, multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Apr;19(4):317-325. [CrossRef]

- Sansone VA, Walter MC, Attarian S, Delstanche S, Mercuri E, Lochmüller H, Neuwirth C, Vazquez-Costa JF, Kleinschnitz C, Hagenacker T. Measuring Outcomes in Adults with Spinal Muscular Atrophy - Challenges and Future Directions - Meeting Report. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;7(4):523-534. [CrossRef]

- Finkel RS, Schara-Schmidt U, Hagenacker T. Editorial: Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Evolutions and Revolutions of Modern Therapy. Front Neurol. 2020 Jul 28;11:783. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Costa, JF. Natural history data in adults with SMA. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Jul;19(7):564-565. [CrossRef]

- Attal N, Bouhassira D, Baron R. Diagnosis and assessment of neuropathic pain through questionnaires. Lancet Neurol. 2018 May;17(5):456-466. [CrossRef]

- Mogil, JS. The history of pain measurement in humans and animals. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2022 Sep 15;3:1031058. [CrossRef]

- El-Tallawy SN, Pergolizzi JV, Vasiliu-Feltes I, Ahmed RS, LeQuang JK, El-Tallawy HN, Varrassi G, Nagiub MS. Incorporation of "Artificial Intelligence" for Objective Pain Assessment: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther. 2024 Jun;13(3):293-317. [CrossRef]

- Lawson SL, Hogg MM, Moore CG, Anderson WE, Osipoff PS, Runyon MS, Reynolds SL. Pediatric Pain Assessment in the Emergency Department: Patient and Caregiver Agreement Using the Wong-Baker FACES and the Faces Pain Scale-Revised. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021 Dec 1;37(12):e950-e954. [CrossRef]

- Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology. 1997 Feb;48(2):332-8. [CrossRef]

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, Baron R, Bennett DLH, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Freeman R, Hansson P, Nurmikko T, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Serra J, Smith BH, Treede RD, Jensen TS. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016 Aug;157(8):1599-1606. [CrossRef]

- van Driel MEC, Huygen FJPM, Rijsdijk M. Quantitative sensory testing: a practical guide and clinical applications. BJA Educ. 2024 Sep;24(9):326-334. [CrossRef]

- Main M, Kairon H, Mercuri E, Muntoni F. The Hammersmith functional motor scale for children with spinal muscular atrophy: a scale to test ability and monitor progress in children with limited ambulation. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2003;7(4):155-9. [CrossRef]

- O'Hagen JM, Glanzman AM, McDermott MP, Ryan PA, Flickinger J, Quigley J, Riley S, Sanborn E, Irvine C, Martens WB, Annis C, Tawil R, Oskoui M, Darras BT, Finkel RS, De Vivo DC. An expanded version of the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale for SMA II and III patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007 Oct;17(9-10):693-7. [CrossRef]

- Ramsey D, Scoto M, Mayhew A, Main M, Mazzone ES, Montes J, de Sanctis R, Dunaway Young S, Salazar R, Glanzman AM, Pasternak A, Quigley J, Mirek E, Duong T, Gee R, Civitello M, Tennekoon G, Pane M, Pera MC, Bushby K, Day J, Darras BT, De Vivo D, Finkel R, Mercuri E, Muntoni F. Revised Hammersmith Scale for spinal muscular atrophy: A SMA specific clinical outcome assessment tool. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 21;12(2):e0172346. [CrossRef]

- Trundell D, Skalicky A, Staunton H, Hareendran A, Le Scouiller S, Barrett L, Cooper O, Gorni K, Seabrook T, Jethwa S, Cano S. Development of the SMA independence scale-upper limb module (SMAIS-ULM): A novel scale for individuals with Type 2 and non-ambulant Type 3 SMA. J Neurol Sci. 2022 Jan 15;432:120059. [CrossRef]

- Bravetti C, Coratti G, Pera MC, Gadaleta G, Mongini T, Coccia M, Ferrero A, Costantini EM, Longo A, Cumbo F, Catteruccia M, D'Amico A, Morando S, Brolatti N, Bruno C, Verriello L, Pessa ME, Antonaci L, Faini C, Liguori R, Vacchiano V, Ruggiero L, Zoppi D, Russo A, Torri F, Ricci G, Chiappini R, Siciliano G, Trabacca A, Agosto C, Benedetti F, Pane M, Mercuri E; ITASMAC working group. Italian validation of the SMA independence scale-upper limb module. Eur J Pediatr. 2025 Jun 10;184(7):410. [CrossRef]

- Sonbas Cobb B, Kolb SJ, Rutkove SB. Machine learning-enhanced electrical impedance myography to diagnose and track spinal muscular atrophy progression. Physiol Meas. 2024 Sep 6;45(9):10.1088/1361-6579/ad74d5. [CrossRef]

- Simon CM, Delestree N, Montes J, Gerstner F, Carranza E, Sowoidnich L, Buettner JM, Pagiazitis JG, Prat-Ortega G, Ensel S, Donadio S, Garcia JL, Kratimenos P, Chung WK, Sumner CJ, Weimer LH, Pirondini E, Capogrosso M, Pellizzoni L, De Vivo DC, Mentis GZ. Dysfunction of proprioceptive sensory synapses is a pathogenic event and therapeutic target in mice and humans with spinal muscular atrophy. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Jun 4:2024.06.03.24308132. [CrossRef]

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Meyer OH, Simonds AK, Schroth MK, Graham RJ, Kirschner J, Iannaccone ST, Crawford TO, Woods S, Muntoni F, Wirth B, Montes J, Main M, Mazzone ES, Vitale M, Snyder B, Quijano-Roy S, Bertini E, Davis RH, Qian Y, Sejersen T; SMA Care group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 2: Pulmonary and acute care; medications, supplements and immunizations; other organ systems; and ethics. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018 Mar;28(3):197-207. [CrossRef]

- Cammarano S, Chirico VA, Giardulli B, Mazzuoccolo G, Ruosi C, Corrado B. Physical and Respiratory Rehabilitation in Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Critical Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2025 Apr 16;15(8):4398. [CrossRef]

- Schroth MK, Deans J, Bharucha Goebel DX, Burnette WB, Darras BT, Elsheikh BH, Felker MV, Klein A, Krueger J, Proud CM, Veerapandiyan A, Graham RJ. Spinal Muscular Atrophy Update in Best Practices: Recommendations for Treatment Considerations. Neurol Clin Pract. 2025 Feb;15(1):e200374. [CrossRef]

- American Physical Therapy Association. Physical Therapy Guide to Spinal Muscular Atrophy. ChoosePT.com. Updated 2025. Available at: https://www.choosept.com/guide/physical-therapy-guide-spinal-muscular-atrophy. Accessed August 2025. (Visited on August 2025).

- Graham RJ, Athiraman U, Laubach AE, Sethna NF. Anesthesia and perioperative medical management of children with spinal muscular atrophy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009 Nov;19(11):1054-63. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Chen X, Liang X, Niu Q, Chan Y, Xu X. Anesthetic management of a patient with spinal muscular atrophy type II for scoliosis surgery: a case report. BMC Anesthesiol. 2025 Apr 11;25(1):173. [CrossRef]

- Sari DM, Wijaya LC, Sitorus WD, Dewi MM. Psychological burden in spinal muscular atrophy patients and their families: A systematic review. Egyptian J Neurol, Psychiatry Neurosur. 2022 Nov 22;58(1):140. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Ming W, Tan Y, Wang Y, Wang M, Li H, Jiao Z, Hou Y. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in patients with motor neuron disease: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025 Jul 25;104(30):e43597. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, EP. Pharmacotherapy of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2020;261:25-37. [CrossRef]

- Tra NT, Kiryu-Seo S, Kida H, Wakatsuki K, Tashiro Y, Tsutsumi M, Ataka M, Iguchi Y, Nemoto T, Takahashi R, Katsuno M, Kiyama H. Absence of the axon initial segment in sensory neuron enhances resistance to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2025 Jul 7:awaf182. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Andrades MJ, Vinolo-Gil MJ, Casuso-Holgado MJ, Barón-López J, Rodríguez-Huguet M, Martín-Valero R. Measurement Properties of Self-Report Questionnaires for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Commonly Used Instruments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Feb 14;20(4):3310. [CrossRef]

- Pota V, Sansone P, De Sarno S, Aurilio C, Coppolino F, Barbarisi M, Barbato F, Fiore M, Cosenza G, Passavanti MB, Pace MC. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Pain: A Narrative Review from Pain Assessment to Therapy. Behav Neurol. 2024 Mar 16;2024:1228194. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).