Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

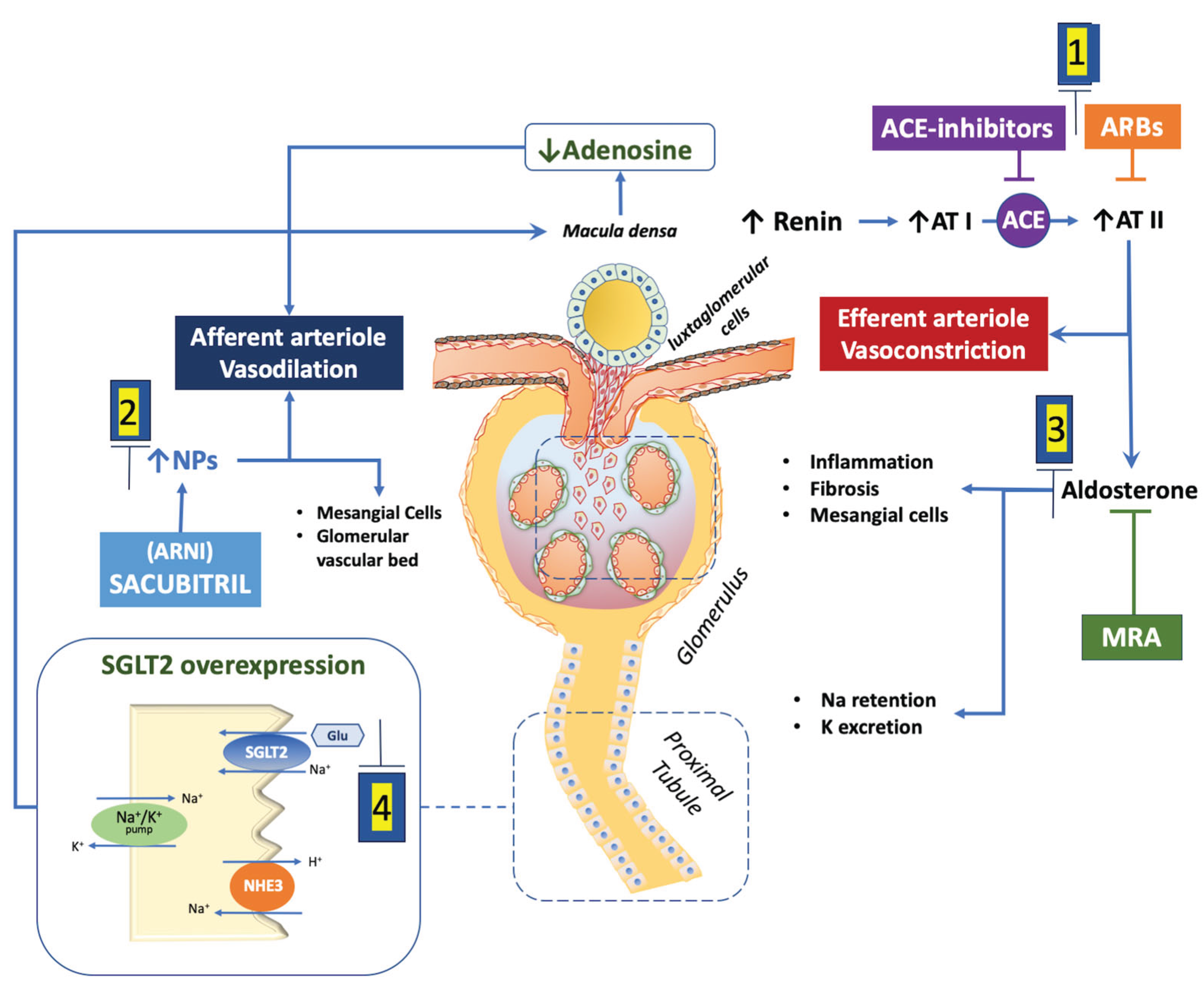

2. Renal Physiology and Heart Failure Hemodynamics

3. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEi) and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARB)

4. Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor (ARNI, Sacubitril/Valsartan)

5. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs)

5.1. Steroid MRAs

5.2. Non-Steroid MRAs

| Study | Population characteristics | Mean GFR* |

eGFR detected changes in study course | Relation between study outcome and detected eGFR changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOPCAT [45,69] | Number. 1767 LVEF 58± 7 |

53% GFR<60 | - Creatinine increase from baseline was greater in spironolacone than in. placebo group (+12.5% vs. +3.5%). - GFR mean reduction was greater in spironolactone than in placebo group (– 2.3 vs -0.7 ml/min/m2) |

- In 14% WRF was observed (Creatinine increase >0.3 mg/dl or >25% from baseline to 4 months). - WRF was associated with increased risk in whole population (HR 2.22 IC 1.67-2.96) - Patients developing WRF in the placebo group were at higher absolute risk of the primary endpoint compared to Spironolactone group: (39.6 events per 100 patient-years;95% CI: 25.5 to 61.3) vs. placebo group (16.7 events per 100 patient-years; 95% CI: 12.0 - 23.3) |

| Pooled analysis of EMPHASIS TOPCAT and EPHESUS [83] |

Number 12700 | 43% with GFR*<60 | 2.6% experienced eGFR< 30 ml/min/m2 across study period | - Randomization to MRA (vs placebo) increased stepwise the odds of developing WRF by 1.2- to 2.0-fold - The effect of MRAs vs placebo on the reduction of CV death / hHF was attenuated as GFR decreased (treatment-by-eGFR interaction P for trend¼ 0.033). - Primary outcome with MRA therapy was similar in those who experienced a decrease in GFR to <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (HR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.43-0.99) compared with those who did not (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.56-0.71) |

| FINEARTS HF [49,50] | Number: 5587 Age 72 ± 10 years Males: 60% LVEF: 53±8% |

62 ± 19 | Early (1 month) GFR decline >15%: 23% in finerenone and 13.4% in placebo (OR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.69-2.24; P < 0.001) |

Greater risk of hHF/CV death after early GFR decline in placebo group (RR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.22-1.99; P < 0.01) than in finerenone group (RR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.90-1.43; P= 0.27; P interaction = 0.06) |

| Study |

Type of Analysis | Albuminuria n (%) |

Adverse outcome | All-Cause Mortality | Drug effects on renal function and albuminuria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Val-Heft [23] | Relationships between study outcomes and proteinuria in HFrEF patients | 405*/5010 (8%) |

- Proteinuria: HR: 1.28 (95%CI: 1.06- 1.55) for first morbid - Proteinuria and CKD: HR: 1.26 (95%CI: 1.01- 1.57) for first morbid - Proteinuria and no-CKD: HR: 1.42 (95%CI: 0.98 to 2.07) for first morbid |

- Proteinuria: HR: 1.28 (95%CI: 1.01- 1.62) for first morbid - Proteinuria and CKD: HR: 1.26 (95%CI: 0.96- 1.66) for first morbid - Proteinuria and no-CKD: HR: 1.37 (95%CI: 0.83 to 2.26) for first morbid |

Without Albuminuria GFR† change: -2.6±0.2 in placebo group vs. -6.5±0.2 in Valsartan group (mean difference -3.9). With Albuminuria GFR† change: -5.3±0.6 in placebo group vs. -6.6±0.6 mL in Valsartan group (mean difference -1.3) |

| PARADIGM-HF [26] | Renal effects of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFrEF | UACR‡: albuminuria in 441/1872 (24%) |

First morbid event, post-hoc prespecified composite renal outcome: sacubitril/valsartan vs Enalapril HR 0.94 (95%CI: 0.40–2.2) | Sacubitril/valsartan vs Enalapril HR 1.15 (95%CI: 0.78–1.71) |

Risk of albuminuria: - HR 1.20 (95% CI: 1.04- 1.36) after sacubitril/valsartan - HR 0.90 (95% CI: 0.77 -1.03) after Enalapril |

| EMPEROR POOLED [65] |

Secondary analysis of EMPEROR reduced and EMPEROR Preserved pooled data | 9673 patients with assessed UACR‡: Microalbuminuria in 32%, macroalbuminuria in 11% |

Empagliflozin vs Placebo for first and recurrent hHF: HR: 0.72; 95%CI: 0.63-0.82 |

Empagliflozin vs. Placebo: HR: 0.97 (95%CI: 0.87-1.08) |

Empagliflozin vs placebo GFR† slope difference: - UACr <30: −1.6 (95%CI: 1.2-1.9) - UACr 30- 300: −2.5 (95%CI: −2.9 - −2.2) - UACr >300: −4.0 (95%CI: −4.6 - −3.3) |

| TOPCAT [45] | Secondary analysis on a TOPCAT subpopulation focusing on UACr association with renal study outcome |

744 patients with UACR‡ detected at baseline and at 1-year visit (microalbuminuria in 35%, macroalbuminuria in 13%) | Crude Model for Efficacy Outcomes on hHF per UACR halving at the 1-Year Visit vs Baseline: HR: 0.89; 95%CI: 0.82-0.97 |

Crude Model for Efficacy Outcomes per UACr, Halving at the 1-Year Visit vs Baseline. HR: 0.90; 95%CI: 0.83–0.97 |

At 1-year visit, in patients with macroalbuminuria, spironolactone reduced albuminuria by 76% (Geometric Mean Ratio: 0.24; 95%CI: 0.10–0.56) |

| FINEARTS-HF [51] | UACr changes over time and the development of microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria | 5797 patients with assessed UACr‡ (microalbuminuria in 30% macroalbuminuria in 10%) |

- | - | After Six months, reduction in UACr in finerenone group: Mean -30% (95%CI: 25%-34%) Composite kidney outcome (including >57% eGFR fall) in Placebo vs Finerenone: HR: 1.28; 95%CI: 0.80-2.05 |

6. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter Type 2 Inhibitors (SGLT2i)

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Afferent arteriole |

| ACEi | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ARB | Angiotensin receptor blockers |

| ARNI | Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitor |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| EA | Effeerent arteriole |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| hHF | Heart failure hospitalizations |

| HFmrEF | Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MRA | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists |

| RAAS | Renin angiotensin aldosterone system |

| sCr | Serum creatinine |

| SGLT2i | Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors |

| WRF | Worsening renal function |

| UACr | Urinary albumin-creatinine ratio |

References

- Damman, K.; Valente, M.A.; Voors, A.A.; O'Connor, C.M.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Hillege, H.L. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014, 35, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, P.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Matsushita, K.; Sang, Y.; Ballew, S.H.; Grams, M.E.; et al. Major cardiovascular events and subsequent risk of kidney failure with replacement therapy: a CKD Prognosis Consortium study. Eur Heart J. 2023, 44, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deursen, V.M.; Urso, R.; Laroche, C.; Damman, K.; Dahlstrom, U.; Tavazzi, L.; Maggioni, A.P.; Voors, A.A. Co-morbidities in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the European Heart Failure Pilot Survey. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damman, K. When Kidney Function Declines But Therapy Still Works: The Case for Nonsteroidal MRA Therapy in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2025, 85, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, W.; Tighiouart, H.; Ku, E.; Salem, D.; Sarnak, M.J. Trends in Kidney Function Outcomes Following RAAS Inhibition in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Am J Kidney Dis 2020, 75, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damman, K.; Perez, A.C.; Anand, I.S.; Komajda, M.; McKelvie, R.S.; Zile, M.R.; Massie, B.; Carson, P.E.; McMurray, J.J. Worsening renal function and outcome in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction and the impact of angiotensin receptor blocker treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 64, 1106–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Ferreira, J.P.; Pocock, S.J.; Zeller, C.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; et al. Cardiac and Kidney Benefits of Empagliflozin in Heart Failure Across the Spectrum of Kidney Function: Insights From EMPEROR-Reduced. Circulation 2021, 143, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Ferreira, J.P.; Rossignol, P.; Neuen, B.L.; Claggett, B.L.; Pfeffer, M.A.; et al. Effects of steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on acute and chronic estimated glomerular filtration rate slopes in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 1586–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahim, A.; Linde, C.; Savarese, G.; Dahlstrom, U.; Lund, L.H.; Hage, C. Implementation of guideline-recommended therapies in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction according to heart failure duration: An analysis of 55‚Äâ581 patients from the Swedish Heart Failure (SwedeHF) Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, R.; Bruss, Z.S.; Sehdev, J.S. Physiology, Renal Blood Flow and Filtration. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482248/.

- Pollak, M.R.; Quaggin, S.E.; Hoenig, M.P.; Dworkin, L.D. The glomerulus: the sphere of influence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 9, 1461–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, P.; Remuzzi, G.; Glassock, R.; Levin, A.; Jager, K.J.; Tonelli, M.; Massy, Z.; Wanner, C.; Anders, H.J. Chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 1708, 3, 17088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. Why do the kidneys release renin in patients with congestive heart failure? A nephrocentric view of converting-enzyme inhibition. Eur Heart J 1990, 11 Suppl D, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, L.; Unnersjo-Jess, D.; Hohne, M.; Edwards, A.; Binz-Lotter, J.; Reilly, D.; et al. A molecular mechanism explaining albuminuria in kidney disease. Nat Metab. 2020, 2, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benghanem Gharbi, M.; Elseviers, M.; Zamd, M.; Belghiti Alaoui, A.; Benahadi, N.; Trabelssi el, H.; et al. Chronic kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity in the adult population of Morocco: how to avoid "over"- and "under"-diagnosis of CKD. Kidney Int 2016, 89, 1363–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, S.; Kjekshus, J.; Swedberg, K. Renal function in severe congestive heart failure during treatment with enalapril (the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study [CONSENSUS] Trial). Am J Cardiol 1992, 70, 479–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dries, D.L.; Exner, D.V.; Domanski, M.J.; Greenberg, B.; Stevenson, L.W. The prognostic implications of renal insufficiency in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000, 35, 681–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testani, J.M.; Kimmel, S.E.; Dries, D.L.; Coca, S.G. Prognostic importance of early worsening renal function after initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail 2011, 4, 685–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Ma, I.; Thompson, C.R.; Humphries, K.; Salem, D.N.; Sarnak, M.J.; Levin, A. Kidney function and mortality among patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 17, 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillege, H.L.; Nitsch, D.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Swedberg, K.; McMurray, J.J.; Yusuf, S.; et al. Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Investigators. Renal function as a predictor of outcome in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure. Circulation 2006, 113, 671–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damman, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Swedberg, K.; Yusuf, S.; Young, J.B.; et al. Worsening renal function and outcome in heart failure patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction and the impact of angiotensin receptor blocker treatment: data from the CHARM-study programme. Eur J Heart Fail 2016, 18, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.E.; Solomon, S.D.; Gerstein, H.C.; Zetterstrand, S.; Olofsson, B.; Michelson, E.L.; e, al.; CHARM Investigators and Committees. Albuminuria in chronic heart failure: prevalence and prognostic importance. Lancet 2009, 374, 543–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, I.S.; Bishu, K.; Rector, T.S.; Ishani, A.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Cohn, J.N. Proteinuria, chronic kidney disease, and the effect of an angiotensin receptor blocker in addition to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in patients with moderate to severe heart failure. Circulation 2009, 120, 1577–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Mann, J.F.; Yi, Q.; et al. HOPE Study Investigators. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA 2001, 286, 421–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; et al. PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damman, K.; Gori, M.; Claggett, B.; Jhund, P.S.; Senni, M.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; et al. Renal Effects and Associated Outcomes During Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018, 6, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voors, A.A.; Gori, M.; Liu, L.C.; Claggett, B.; Zile, M.R.; Pieske, B.; et al.; PARAMOUNT Investigators Renal effects of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 510–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggenenti, P.; Remuzzi, G. Combined neprilysin and RAS inhibition for the failing heart: straining the kidney to help the heart? Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17(5), 468–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, A.A.; Wanner, C.; Sarnak, M.J.; Pina, I.L.; McIntyre, C.W.; Komenda, P.; et al.; Conference Participants Heart failure in chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2019, 95, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatur, S.; Neuen, B.L.; Claggett, B.L.; Beldhuis, I.E.; Mc Causland, F.R.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan Across the Spectrum of Renal Impairment in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 2148–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Anand, I.S.; Ge, J.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; et al. PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019, 38, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatur S, Claggett BL, McCausland FR, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Packer M, Pfeffer MA, Lefkowitz M, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M. Variation in Renal Function Following Transition to Sacubitril/Valsartan in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Causland, F.R.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Claggett, B.; Anavekar, N.S.; Senni, M.; Gori, M.; et al. . Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition and Renal Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2020, 142, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatur, S.; Vaduganathan, M.; Peikert, A.; Claggett, B.L.; McCausland, F.R.; Skali, H.; et al. Longitudinal trajectories in renal function before and after heart failure hospitalization among patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the PARAGON-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontremoli, R.; Borghi, C.; Perrone Filardi, P. Renal protection in chronic heart failure: focus on sacubitril/valsartan. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2021, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Jackson, A.M.; Lam, C.S.P.; Redfield, M.M.; Anand, I.S.; Ge, J.; et al. Effects of Sacubitril-Valsartan Versus Valsartan in Women Compared With Men With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights From PARAGON-HF. Circulation 2020, 141, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selye, H.; Hall, C.E.; Rowley, E.M. Malignant Hypertension Produced by Treatment with Desoxycorticosterone Acetate and Sodium Chloride. Can Med Assoc J 1943, 49, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Remme, W.J.; Cody, R.; Castaigne, A.; Perez, A.; Palensky, J.; Wittes, J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999, 341(10), 709–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juurlink, D.N.; Mamdani, M.M.; Lee, D.S.; Kopp, A.; Austin, P.C.; Laupacis, A.; Redelmeier, D.A. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med 2004, 351, 543–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; McMurray, J.J.; Krum, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Swedberg, K.; Shi, H.; et al.; EMPHASIS-HF Study Group Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011, 364, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschalier, R.; McMurray, J.J.; Swedberg, K.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Krum, H.; Pocock, S.J.; et al.; EMPHASIS-HF Investigators Safety and efficacy of eplerenone in patients at high risk for hyperkalemia and/or worsening renal function: analyses of the EMPHASIS-HF study subgroups (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization And SurvIval Study in Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013, 62, 1585–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Assmann, S.F.; Boineau, R.; Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.; et al.; TOPCAT Investigators Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014, 370, 1383–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, M.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Lindenfeld, J.; Kao, D.P. Sex Differences in Outcomes and Responses to Spironolactone in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Secondary Analysis of TOPCAT Trial. JACC Heart Fail 2019, 7, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.; Liu, J.; Shah, A.M.; Rector, T.S.; Shah, S.J.; et al. Interaction Between Spironolactone and Natriuretic Peptides in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: From the TOPCAT Trial. JACC Heart Fail 2017, 5, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Claggett, B.; Assmann, S.F.; Boineau, R.; Anand, I.S.; Clausell, N.; et al. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation 2015, 131, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, S.; Claggett, B.; Shah, S.J.; Anand, I.; Rouleau, J.L.; O'Meara, E.; et al. Prognostic Value of Albuminuria and Influence of Spironolactone in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2018, 11, e005288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc. KERENDIA (finerenone) prescribing information. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://labeling. bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/Kerendia_ PI.pdf.

- Filippatos, G.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; et al. Finerenone and Heart Failure Outcomes by Kidney Function/Albuminuria in Chronic Kidney Disease and Diabetes. JACC Heart Fail 2022, 10, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.; Jhund, P.S.; Desai, A.S.; et al.; FINEARTS-HF Committees and Investigators Finerenone in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2024, 391, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Bauersachs, J.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Initial Decline in Glomerular Filtration Rate With Finerenone in HFmrEF/HFpEF: A Prespecified Analysis of FINEARTS-HF. J Am Coll Cardiol 2025, 85, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Causland, F.R.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.J.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.S.; et al. Finerenone and Kidney Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure: The FINEARTS-HF Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2025, 85, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhund, P.S.; Talebi, A.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure: an individual patient level meta-analysis. Lancet 2024, 404, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group; SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal Trialists' Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials. Lancet 2022, 400(10365), 1788-1801. [CrossRef]

- Marton, A.; Saffari, S.E.; Rauh, M.; Sun, R.N.; Nagel, A.M.; Linz, P.; et al. Water Conservation Overrides Osmotic Diuresis During SGLT2 Inhibition in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 1386–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherney, D.Z.; Perkins, B.A.; Soleymanlou, N.; Maione, M.; Lai, V.; Lee, A.; et al. Renal hemodynamic effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2014, 129, 587–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronda, E.; Iacoviello, M.; Arduini, A.; Benvenuto, M.; Gabrielli, D.; Bonomini, M.; Tavazzi, L. Gliflozines use in heart failure patients. Focus on renal actions and overview of clinical experience. Eur J Intern Med 2025, 132, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Pocock, S.J.; et al.; EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Committees and Investigators Influence of neprilysin inhibition on the efficacy and safety of empagliflozin in patients with chronic heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallon, V.; Kim, Y.C. Protecting the Kidney: The Unexpected Logic of Inhibiting a Glucose Transporter. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022, 112, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, C.; Docherty, K.F.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; de Boer, R.A.; Damman, K.; Inzucchi, S.E.; et al. Initial Decline (Dip) in Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate After Initiation of Dapagliflozin in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: Insights From DAPA-HF. Circulation 2022, 146, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Causland, F.R.; Claggett, B.L.; Vaduganathan, M.; Desai, A.S.; Jhund, P.; de Boer, R.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Kidney Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure With Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Prespecified Analysis of the DELIVER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Ferreira, J.P.; Gregson, J.; Kraus, B.J.; Mattheus, M.; Hauske, S.J.; et al.; EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Committees and Investigators Early changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate post-initiation of empagliflozin in EMPEROR-Reduced. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, T.; Ferreira, J.P.; Butler, J.; Kraus, B.J.; Mattheus, M.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Early changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate post-initiation of empagliflozin in EMPEROR-Preserved. Eur J Heart Fail 2024, 26, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Butler, J.; Zeller, C.; Pocock, S.J.; Brueckmann, M.; Ferreira, J.P.; et al. Blinded Withdrawal of Long-Term Randomized Treatment With Empagliflozin or Placebo in Patients With Heart Failure. Circulation 2023, 148, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.; Perkins, B.A.; Fitchett, D.H.; Husain, M.; Cherney, D.Z. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: Cardiovascular and Kidney Effects, Potential Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Circulation 2016, 134, 752–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Zannad, F.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Association of Empagliflozin Treatment With Albuminuria Levels in Patients With Heart Failure: A Secondary Analysis of EMPEROR-Pooled. JAMA Cardiol 2022, 7, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Nie, Z.; Shi, R.; Yu, D.; Wang, Q.; Shao, F.; et al. Time to Benefit of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors Among Patients With Heart Failure. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2330754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, N.; Federici, M.; Schott, K.; Muller-Wieland, D.; Ajjan, R.A.; Antunes, M.J.; et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 4043–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beldhuis, I.E.; Lam, C.S.P.; Testani, J.M.; Voors, A.A.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Damman, K. Evidence-Based Medical Therapy in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation 2022, 145, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaziano, L.; Sun, L.; Arnold, M.; Bell, S.; Cho, K.; Kaptoge, S.K.; et al.; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration/EPIC-CVD/Million Veteran Program Mild-to-Moderate Kidney Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Disease: Observational and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Circulation 2022, 146, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonneijck, L.; Muskiet, M.H.; Smits, M.M.; van Bommel, E.J.; Heerspink, H.J.; van Raalte, D.H.; Joles, J.A. Glomerular Hyperfiltration in Diabetes: Mechanisms, Clinical Significance, and Treatment. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 28, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuen, B.L.; Tighiouart, H.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Vonesh, E.F.; Chaudhari, J.; Miao, S.; et al.; CKD-EPI Clinical Trials Acute Treatment Effects on GFR in Randomized Clinical Trials of Kidney Disease Progression. J Am Soc Nephrol 2022, 33, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, F.A.; de Zeeuw, D.; Thomas, M.C.; Cooper, M.E.; de Graeff, P.A.; et al. An acute fall in estimated glomerular filtration rate during treatment with losartan predicts a slower decrease in long-term renal function. Kidney Int 2011, 80, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Bakris, G.L.; Packer, M.; Shahid, I.; Anker, S.D.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Kidney function assessment and endpoint ascertainment in clinical trials. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 1379–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, J.H.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.L.; Jhund, P.S.; Neuen, B.L.; McCausland, F.R.; et al. Therapeutic Effects of Heart Failure Medical Therapies on Standardized Kidney Outcomes: Comprehensive Individual Participant-Level Analysis of 6 Randomized Clinical Trials. Circulation 2024, 150, 1858–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Tighiouart, H.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Gansevoort, R.T.; et al. GFR Slope as a Surrogate End Point for Kidney Disease Progression in Clinical Trials: A Meta-Analysis of Treatment Effects of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2019, 30, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, P.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Matsushita, K.; Sang, Y.; Ballew, S.H.; Grams, M.E.; et al. Major cardiovascular events and subsequent risk of kidney failure with replacement therapy: a CKD Prognosis Consortium study. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronda E, Palazzuoli A, Iacoviello M, Benevenuto M, Gabrielli D, Arduini A. Renal Oxygen Demand and Nephron Function: Is Glucose a Friend or Foe? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 9957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Jhund, P.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Brinker, M.; et al. The efficacy of finerenone on hierarchical composite endpoint analysed using win statistics in patients with heart failure and mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: A prespecified analysis of FINEARTS-HF. Eur J Heart Fail 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Neuen, B.L.; McCausland, F.; Jhund, P.S.; Docherty, K.F.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D. Why Has it Been Challenging to Modify Kidney Disease Progression in Patients With Heart Failure? J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 84, 2241–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Effects of empagliflozin on progression of chronic kidney disease: a prespecified secondary analysis from the empa-kidney trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2024, 12, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, R.D.; Tobin, J.; Shock, N.W. Longitudinal studies on the rate of decline in renal function with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985, 33, 278–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Pitt, B.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pocock, S.J.; Solomon, S.D.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Zannad, F.; Rossignol, P. Steroidal MRA Across the Spectrum of Renal Function: A Pooled Analysis of RCTs. JACC Heart Fail 2022, 10, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Population characteristics | Mean eGFR* |

Mean early renal function changes in treated arm vs. control arm |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOLVD Treatment and Prevention (cumulative): Enalapril vs. placebo [5] |

Number: 6245, Age: 59±10 years, LVEF: <35% | Treatment: 69.5±19 Prevention: 76.2±18 |

Treatment: -27.3(-33-21) Prevention: -12,8 (-17.4-8.4) |

| CHARM program Candesartan v. placebo [20] |

Number: 2405, Age: 65±12 years, Males: 68%, Diabetes: 38%, Mean LVEF 39 % | 71 ± 27 | Creatinine increase>25% at 6 weeks 16% vs. 25% |

| PARADIGM HF Sacubiril/valsartan vs Enalapril [32] |

Number: 8,096, Age: 64±11 years, Males: 78%, Diabetes: 35%, LVEF: 31% | 68 ± 19 | Run-in GFR decline >15% in 11% of patients. |

| PARAGON-HF Sacubiril/valsartan vs Enalapril [32] |

Number: 4665, Age: 73±8 years, Males: 52%, Diabetes: 43%, LVEF: 58% | 63±19 | Run-in GFR decline >15% in 10% of patients |

|

Mean chronic renal function changes in treated arm vs. control |

Cardiovascular outcomes | ||

| SOLVD Treatment and Prevention (cumulative): Enalapril vs. placebo [5] |

Treatment -27.3(-33-21) Prevention -12,8 (-17.4-8.4) |

Mortality in placebo vs. enalapril group: - CKD patients: 45% vs. 42% (HR, 0.88; CI, 0.73-1.06; p=0.164) - non CKD patients: 36% vs. 31% (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.98; p=0.028) |

|

| CHARM program Candesartan v. placebo [20] |

Creatinine increase>25% at 6 weeks 16% vs. 25% |

Candesartan reduced both sudden death (HR 0.85 [0.73 to 0.99], P=0.036) and death from worsening HF | |

| PARADIGM HF Sacubiril/valsartan vs Enalapril [32] |

Run-in GFR decline >15% in 11% of patients. |

CV death/hHF: - Enalapril vs.sacubitril/valsartan in no GFR decline: 13.08 (95%CI: 12.27-13.96) vs. 10.46 (95%CI: 9.74-11.23) events/100 person years (HR: 0.79; 95%CI: 0.72-0.87)) - Enalapril vs.sacubitril/valsartan in GFR decline: 14.24 (95%CI: 11.93-17.08) vs. 9.70 (95%CI 7.93-11.96) events/100 person years (HR: 0.78; 95%CI: 0.61-1.01) |

|

| PARAGON-HF Sacubiril/valsartan vs Enalapril [32] |

Run-in GFR decline >15% in 10% of patients |

CV death/hHF: - Valsartan vs.sacubitril/valsartan in no GFR decline: 14.11 (95%CI:12.58-15.88) vs. 12.43 (95%CI: 11.12-13.93) events per 100 person years (HR 0.87; 95%CI: 0.74-1.03) - Valsartan vs.sacubitril/valsartan in GFR decline: 17.27 (13.59-22.27) vs. 15.16 (11.56-20.24) events per 100 person years (HR: 0.84; 95%CI: 0.58-1.20) |

|

| Study | Population characteristics | Mean early GFR* changes in treated arm vs. control arm |

Mean chronic GFR* changes in treated arm vs. control |

Cardiovascular outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPA-HF Dapagliflozin vs. Placebo [59] |

Number: 4618 Age: 66 ± 11 years Males: 77% Diabetes: 42% LVEF: 31% Median eGFR*: 66 |

-4.19 (95%CI: -4.52/-3.87) vs. -1.09 (95%CI: -1.42/-0.77) | -1.09 (95%CI: 1.40 / -0.77) vs. - 2.85 (95%CI: -3.17 / -2.53) | CV death /hHF: 11.4 vs 15,6 per 100 pts/year (HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.61-1.00) |

| EMPEROR-R Empagliflozin vs. Placebo [61] |

Number: 3547 Age: 67 ± 11 years Males:76% Diabetes: 50% LVEF: 27% Mean eGFR*: 62±22 |

-3.5 (95%CI: -3.1/-3.9) vs. -1.0 (95%CI: -0,6/-1.4) |

-0.55 ±0.23 (SD) vs. -2.28±0.23(SD) |

CV death /hHF: 15.8 vs 21 per 100 pts/year (HR: 0.75; 95%CI: 0.65 0.86) |

| EMPEROR-P Empagliflozin vs. Placebo [62] |

Number: 5836 Age: 72 ± 9 years Males: 65% Diabetes: 49% LVEF: 54% Mean eGFR*: 61±20 |

−3.7 (95%CI: −4.0 / −3.4) vs. −0.5 (95%CI: −0.8 to−0.2) |

−1.25 ± 0.11(SD) vs. −2.62 ± 0.11(SD) |

CV death /hHF: 6,9 vs 8,7 per 100 pts/year (HR: 0.79; 95%CI: 0.69- 0.90) |

| DELIVER Dapagliflozin vs. Placebo [60] |

Number: 6262 Age: 72 ± 10 years Males 56% Diabetes: 45% LVEF: 54% Mean eGFR*: 61 ± 19 |

-3.7 (95%CI: -4.0/-3.3) vs. -0.4 (95%CI: -0,8/-0.0) |

-0.5(95%CI: −0.1 / -0.9) vs. −1.4 (95%CI: −1.0 / −1.8) |

CV death /hHF: 11,8 vs 15,4 per 100 pts/year (HR: 0.77; 95%CI: 0,67- 0,78) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).