In this retrospective study of 1.009 adult inpatients with COVID-19, admission hyperglycemia was associated with significantly more severe clinical courses, higher medical resource consumption, and worse prognosis than normoglycemia. Our results align with the literature identifying admission hyperglycemia as an important predictor of severity and mortality in COVID-19 [

1,

2,

3]. Admission glucose correlates directly with risk of progression to severe disease and death [

39,

40]. The risk factors identified here are consistent with prior research, highlighting robust correlations between systemic immune responses and inflammation with potential multiorgan involvement that contributes to worsening disease [

1,

2,

3].

4.1. Metabolic Profile and Risk Factors

Sex distribution differed significantly by admission glycemia, with men predominating among hyperglycemics (58.3% vs. 41.7%; p=0.0003) and women among normoglycemics (54.5% vs. 45.5%). This matches epidemiologic data indicating higher prevalence and worse outcomes in men with SARS-CoV-2 infection [

50]. Age was also significantly associated with admission glycemia: patients aged 36–50 years were more often normoglycemic (24.7% vs. 17.6%), whereas those aged 66–80 years were predominantly hyperglycemic (37.9% vs. 26.5%; p<0.001), in line with evidence that advanced age is a risk factor for hyperglycemia and poor prognosis in SARS-CoV-2 infection [

55,

56]. CDC guidance likewise emphasizes substantially higher risks of severe disease, complications, and mortality in those ≥65 years [

57]. Early glycemic monitoring and metabolic control strategies are therefore crucial in older patients.

Hypertension and obesity were significantly more frequent among hyperglycemics (51.2% vs. 41.5%, p=0.007; and 10.8% vs. 3.6%, p=0.0006, respectively). These comorbidities are well-known for worsening COVID-19 course, being associated with higher mortality and severe complications. Respiratory comorbidities did not differ significantly, suggesting metabolic comorbidities (hypertension, obesity) are most relevant for hyperglycemic COVID-19 patients [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Mechanistically, hyperglycemia impairs immune responses and increases susceptibility to severe infections; obesity, hypertension, and diabetes contribute to severe disease through factors such as increased ACE2 expression in adipose tissue and exacerbation of systemic inflammation [

40,

41,

52].

4.2. Clinical Severity and Respiratory Involvement

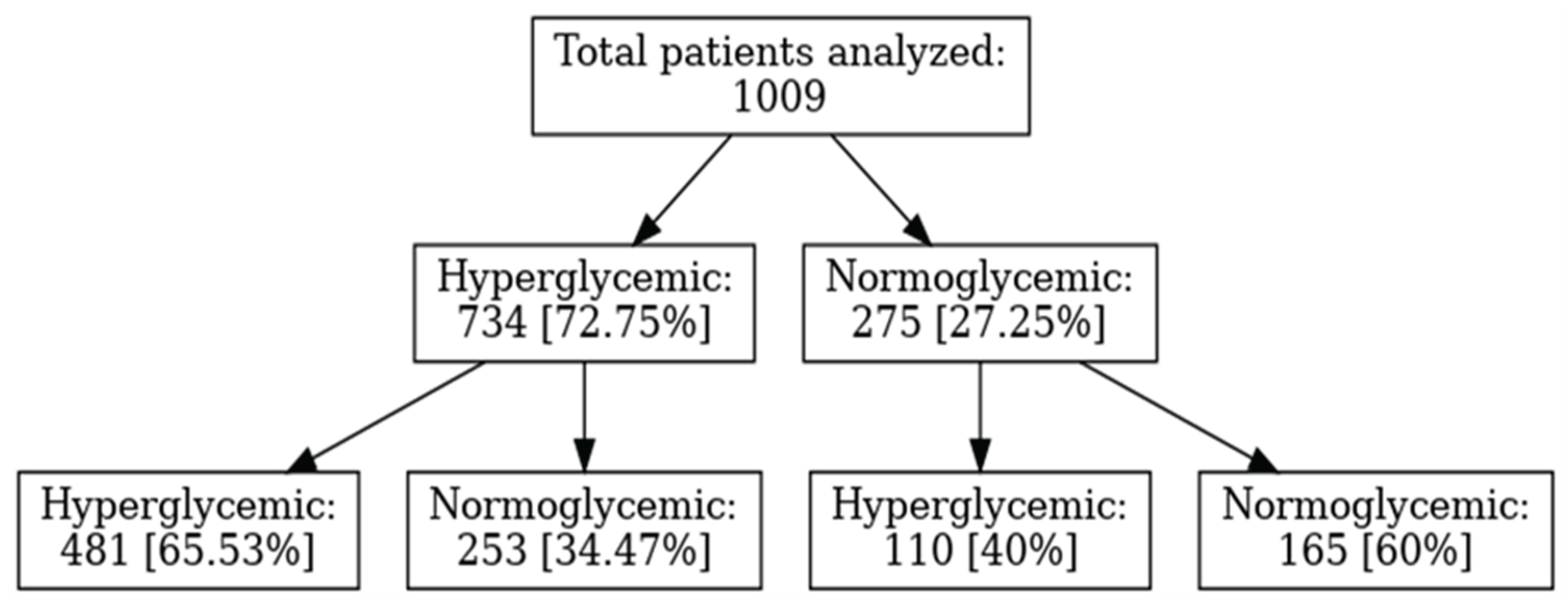

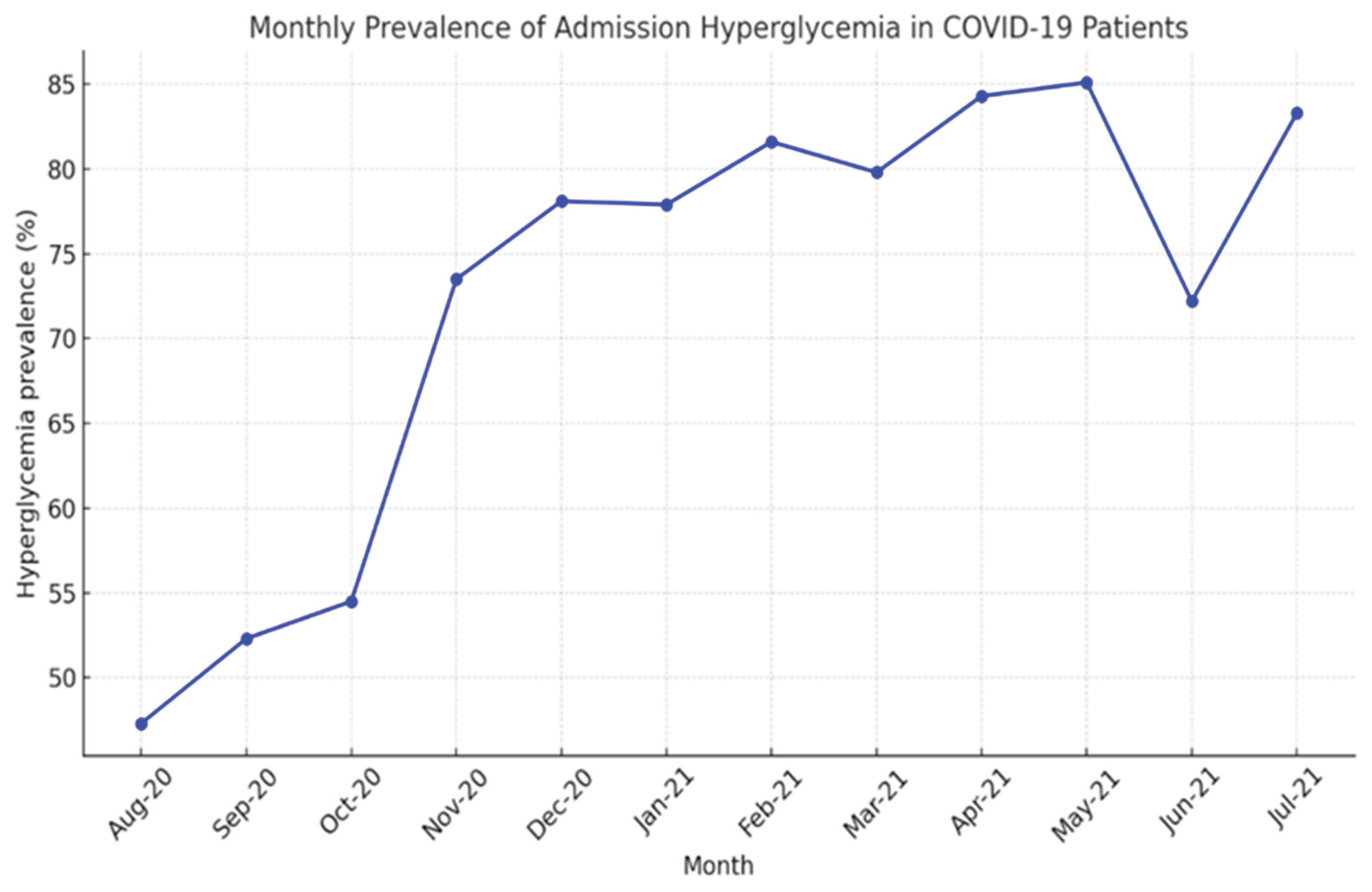

In our non-diabetic cohort (n=1009), a remarkable 72.7% presented with disordered glucose metabolism at admission, with values from 107 mg/dL (106 mg/dL being the analyzer’s upper normal limit) up to 620 mg/dL (the latter in a 50-year-old woman). A temporal analysis of COVID-19 hospitalizations and admission hyperglycemia revealed that, in the first months (August–October 2020), hyperglycemia was present in 47–55% of patients, a lower percentage compared to subsequent months. The sharp increase observed between November 2020 and January 2021 (73–78%) coincided with the second pandemic wave and a growing number of severe cases, suggesting that hyperglycemia may represent a marker of COVID-19 severity. The peak values recorded between February and May 2021 (82–85%) corresponded to the wave driven by the Alpha variant and indicated that more than four out of five hospitalized patients presented with admission hyperglycemia, supporting the hypothesis of a bidirectional relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and hyperglycemia: the viral variant associated with more severe forms induces hyperglycemia, while metabolic disturbances, in turn, influence the clinical phenotype of COVID-19. The 38-percentage-point difference between the minimum and maximum values is statistically significant and highlights the clinical relevance of admission hyperglycemia as a prognostic indicator. These findings suggest that admission hyperglycemia is closely associated with COVID-19 severity; thus, early monitoring and glycemic control may be essential to improve outcomes in hospitalized patients [

4,

5,

6,

39].

Likewise, in our cohort, severe forms of COVID-19 were more frequent in hyperglycemic patients, and acute respiratory failure was nearly twice as common compared to normoglycemic patients, suggesting more pronounced pulmonary involvement associated with hyperglycemia. Although the overall incidence of critical forms was low, these were more than five times more frequent in hyperglycemics. The need for non-invasive ventilation was nearly five times higher among hyperglycemics, whereas mild forms predominated in normoglycemics. The probability of ICU admission was more than five times higher in hyperglycemic patients, noting that some patients used CPAP in the infectious diseases ward due to ICU bed shortages. Mortality was also significantly higher among hyperglycemics. These data show that admission hyperglycemia is not only a marker of severity but also a possible independent negative prognostic factor, contributing to clinical decompensation and increased risk of death [

5,

65,

66]. The associations persist even in the absence of a previous diagnosis of diabetes, suggesting that stress hyperglycemia or newly diagnosed diabetes may have similar clinical implications [

63,

67]. In 60.4% of hyperglycemic patients, hyperglycemia persisted during hospitalization; 12.4% required insulin therapy for glycemic control. Among patients with admission glucose > 180 mg/dL, 77.5% developed severe or critical forms with respiratory failure, 16.5% required non-invasive ventilation, and 7% died. In a retrospective study (Inner-City Hospital, 2020), patients without diabetes but with admission glucose > 200 mg/dL had significantly higher mortality; moreover, stress hyperglycemia in the absence of pre-existing diabetes was associated with even greater risks than in patients with known diabetes [

41]. Consequently, admission glucose levels correlate directly with clinical severity and risk of death, as reported both in our study and in other research [

17,

18,

40].

Similar results were reported by Fadini et al. in a retrospective analysis of 413 COVID-19 patients, which highlighted a strong correlation between admission glucose and clinical severity/complications, with a significantly stronger association (p < 0.001) in newly diagnosed diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or random glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L [≥ 200 mg/dL] in the presence of hyperglycemia symptoms) compared to pre-existing diabetes. Each 2 mmol/L (36 mg/dL) increase in fasting admission glucose was associated with a 21% relative increase in the risk of severe disease [

17]. Similarly, Coppelli et al., in a retrospective study of 271 patients, showed that admission hyperglycemia remained the only independent predictor of mortality (p = 0.04); mortality was significantly higher in patients with “new” hyperglycemia (≥ 140 mg/dL) without diabetes compared to normoglycemics (< 140 mg/dL): 39.4% vs. 16.8% [

18].

Age-stratified analysis of CPAP requirement adds further nuance: in patients ≤ 50 years, the need was low and similar between groups, likely reflecting better respiratory reserve; in those aged 51–65 years, hyperglycemia was associated with an eightfold higher risk of requiring CPAP, while in patients ≥ 66 years the rate was about 4.5 times higher than in normoglycemics, suggesting a possible additive effect of hyperglycemia on age-related pulmonary vulnerability [

23].

4.3. Immune Dysfunction and Inflammatory Profile in Hyperglycemia

Accumulating evidence indicates that hyperglycemia is associated with profound immune dysfunction, including lymphopenia, elevated CRP and D-dimer, and coagulation abnormalities (21,25). Recent meta-analyses confirm significantly higher levels of ferritin, CRP, IL-6, fibrinogen, and D-dimer in hyperglycemic/diabetic patients compared with normoglycemics, reflecting an amplified proinflammatory and prothrombotic state [

22,

24].

In our cohort, laboratory findings consistently linked hyperglycemia with heightened immune/inflammatory responses. Severe lymphopenia (< 1000/μL) occurred in nearly 60% of hyperglycemics versus 23% of normoglycemics, underscoring marked cellular immune impairment. Hyperglycemia may exacerbate this dysfunction through mechanisms such as abnormal protein glycosylation and impaired T-cell activation, thereby limiting viral clearance. Supporting these observations, a recent study in Diseases (2024) reported that hyperglycemic COVID-19 patients exhibited reduced lymphocytes, lower oxygen saturation, and increased LDH and ferritin, all markers of severe disease [

21]. Other reports similarly noted that hyperglycemia and diabetes are associated with profound lymphopenia and elevated CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, and PCT compared with non-diabetic patients [

27]. Complete eosinopenia, observed in 84% of hyperglycemics in our study, further supports an intense acute inflammatory response; its predictive value for ICU admission and respiratory support has been described elsewhere (28). Consistent with these hematologic abnormalities, hyperglycemic patients showed significantly higher levels of ESR, CRP, ferritin, and fibrinogen, suggesting a pronounced proinflammatory milieu driven by oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and activation of the IL-6/TNF-α cytokine axis [

21,

29]. Elevated D-dimer and LDH indicated increased thrombotic risk and extensive tissue injury, particularly pulmonary, in line with previous reports identifying hyperglycemia as an independent risk factor for thromboembolic complications and alveolo-capillary damage [

21,

29].

Transaminase elevations (ALT, AST) were also more frequent in hyperglycemics, possibly reflecting systemic inflammatory injury, viral-induced hepatic involvement, metabolic toxicity, or muscle damage [

21,

27]. In contrast, creatinine did not differ significantly between groups, suggesting that renal impairment at admission is more likely attributable to factors such as hypotension, hypoxia, or nephrotoxic drugs rather than hyperglycemia itself [

42].

Taken together, these findings indicate that hyperglycemic patients display a markedly more severe inflammatory and hematologic profile than normoglycemics, characterized by lymphopenia, eosinopenia, and elevated inflammatory and coagulation markers, thereby supporting the concept of hyperglycemia as both a marker and amplifier of severe COVID-19.

4.4. Comparative Analysis by Hyperglycemia Severity

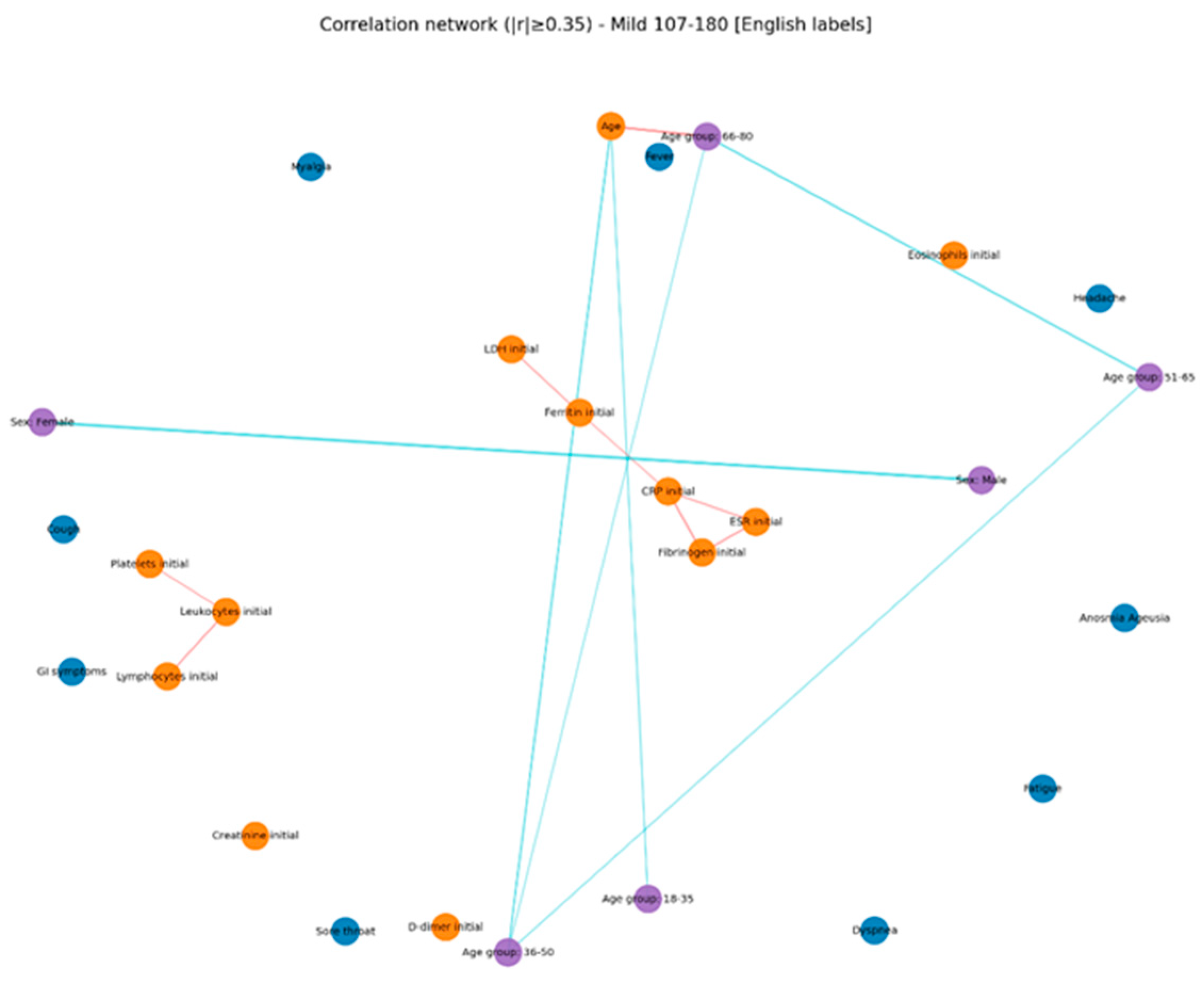

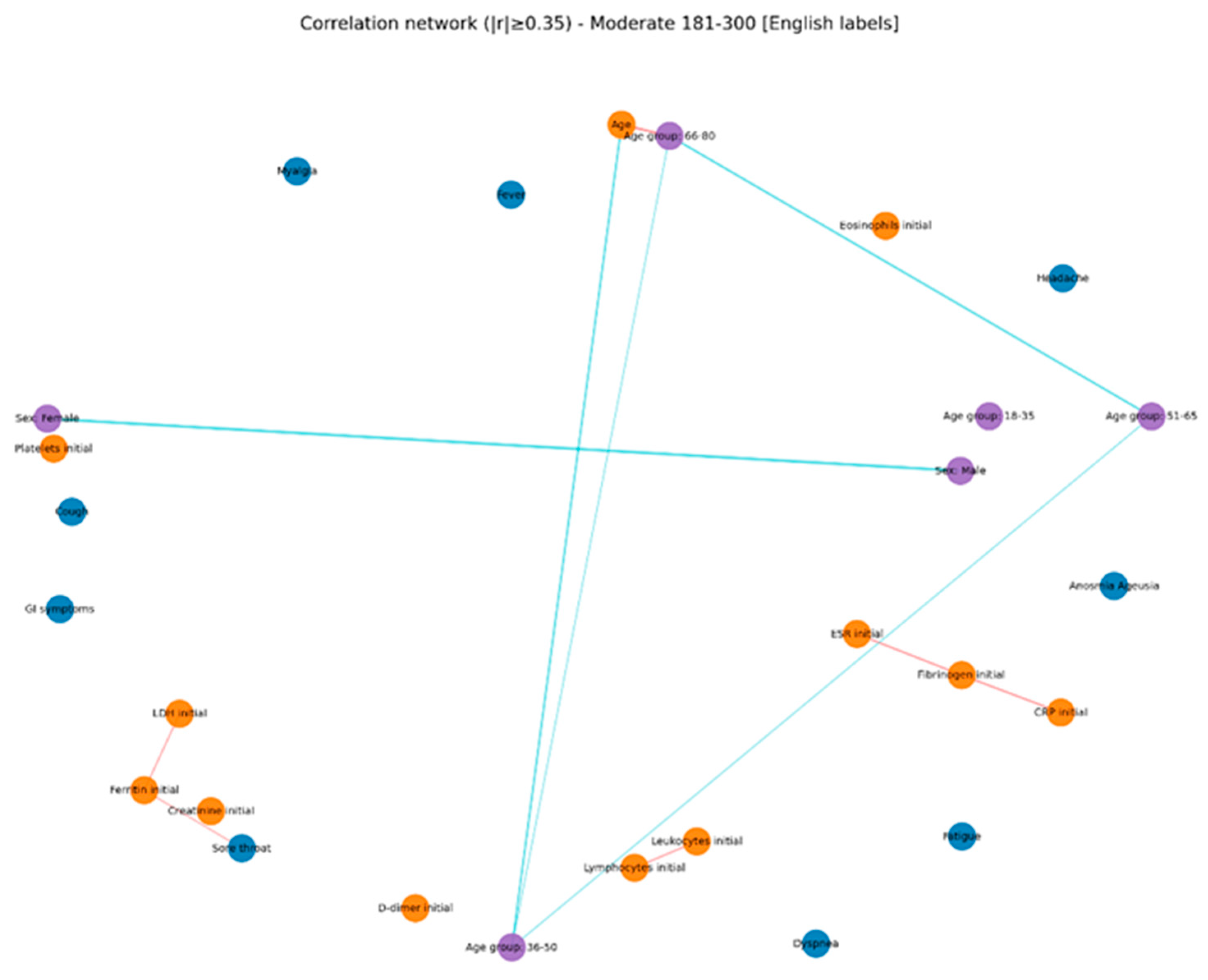

The comparative analysis of clinical and biological profiles according to hyperglycemia severity highlights a graded progression of the inflammatory response and hematologic parameters as glucose levels rise. Three distinct subgroups — mild hyperglycemia (107–180 mg/dL), moderate hyperglycemia (181–300 mg/dL), and severe hyperglycemia (> 300 mg/dL) — showed significant quantitative and qualitative differences, with important clinical and prognostic implications.

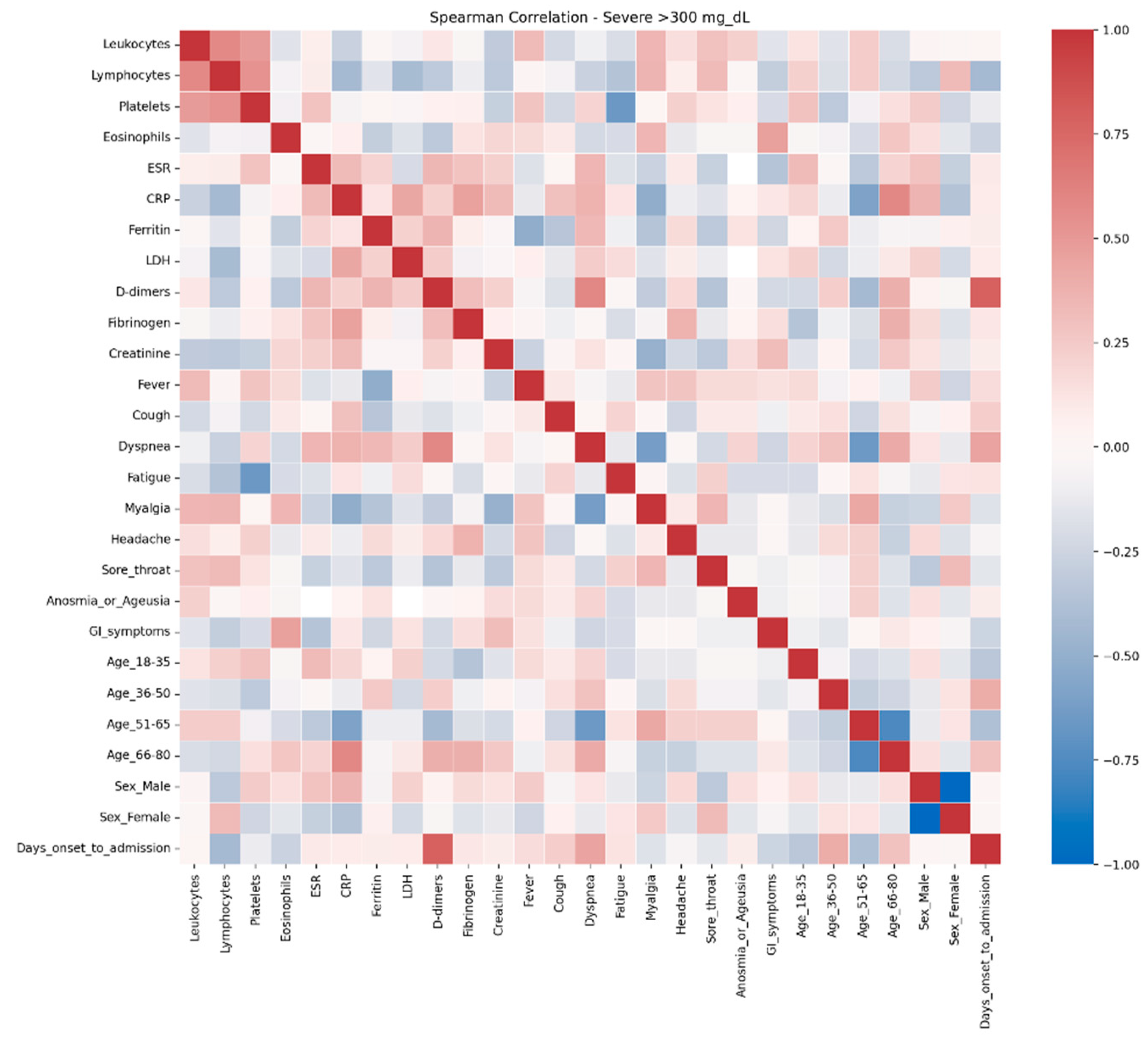

Even in the absence of a prior diabetes diagnosis, elevated glucose levels can amplify systemic inflammation and alter hematologic and coagulation functions (58). In the severe hyperglycemia group (> 300 mg/dL), notable correlations were observed: CRP was inversely associated with oxygen saturation and positively with radiologic severity and D-dimer levels, suggesting an intense systemic inflammatory syndrome with pulmonary and vascular involvement. D-dimers correlated with time to hospitalization and radiologic score, indicating an early, aggressive vascular inflammatory process associated with rapid disease progression. Markers of cellular injury, particularly LDH, showed negative correlations with O₂ saturation and positive associations with dyspnea in severe hyperglycemia, suggesting extensive pulmonary damage [

59].

Across all groups, LDH correlated positively with ferritin, AST, and CRP, but these correlations were strongest in the moderate hyperglycemia subgroup, pointing to multisystem cellular injury. A retrospective study by Kumar et al. (2025) [

60] demonstrated that CRP, D-dimer, and IL-6 are independent risk factors for COVID-19 severity, while CRP, D-dimer, LDH, ferritin, and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) are independent predictors of mortality. D-dimer emerged as the most sensitive and specific marker of severity, while LDH was the most reliable predictor of mortality [

68,

69,

70]. Hepatic involvement was evident in moderate hyperglycemia, reflected by correlations between transaminases and inflammatory markers; however, in extreme hyperglycemia these associations disappeared, possibly indicating less pronounced secondary hepatic injury or a clinical picture dominated by pulmonary and systemic involvement. Diaz-Louzao C. et al. (2022) examined the temporal relationships between inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6, D-dimer, lymphocyte count) and hepatic injury markers (AST, ALT, GGT), showing different patterns depending on disease evolution and prognosis [

71]. Notably, deceased patients had elevated hepatocellular markers positively correlated with inflammatory markers, whereas in survivors these correlations became inverse after one week of hospitalization [

63,

71].

Oxygen saturation decreased in parallel with negative correlations to CRP, LDH, and chest radiologic score across all subgroups, with maximum intensity in patients with glucose ≥ 300 mg/dL, reflecting severe hypoxemia and extensive pulmonary involvement. In this group, the radiologic score was the most interconnected marker, correlating with CRP, ferritin, and D-dimer, supporting the suspicion of severe viral pneumonia and intense inflammation [

32].

Correlations between inflammatory markers (CRP–LDH, ferritin–LDH) were evident in groups with lower glucose levels but disappeared in extreme hyperglycemia, possibly reflecting a “saturated” inflammatory response in which traditional biological relationships become attenuated due to profound systemic dysfunction.

These results support the hypothesis that elevated glucose levels, even without pre-existing diabetes, can amplify systemic inflammatory responses and induce hematologic and coagulation changes [

61,

62]. Patients with glucose > 300 mg/dL showed tighter integration of clinical symptoms with biological parameters, which may explain their higher risk of complications and the need for more aggressive monitoring and intervention.

The persistence of isolated symptoms (anosmia, fatigue), even at high glucose levels, suggests that not all clinical manifestations are directly influenced by metabolic status. In contrast, inflammatory and hematologic parameters appear to be more sensitive indicators of hyperglycemia severity and may serve as prognostic markers.

These observations provide an integrated perspective on the interaction between glucose metabolism and the inflammatory response, supporting a stratified management approach in patients with acute hyperglycemia. In practice, early identification of patients with complex networks of correlations (inflammatory, hematologic, and clinical) may guide timely therapeutic interventions and prevent progression to severe forms or major metabolic decompensation.

Overall, the data support the concept that admission hyperglycemia in COVID-19 is more than a simple metabolic marker, representing an indicator of disease severity. Multiple correlations between glucose, inflammation, pulmonary involvement, and tissue injury suggest that early glycemic control may have significant prognostic implications. These findings align with other studies demonstrating the clear association between hyperglycemia and mortality in COVID-19, even in patients without pre-existing diabetes [

15,

21,

29,

30,

31].

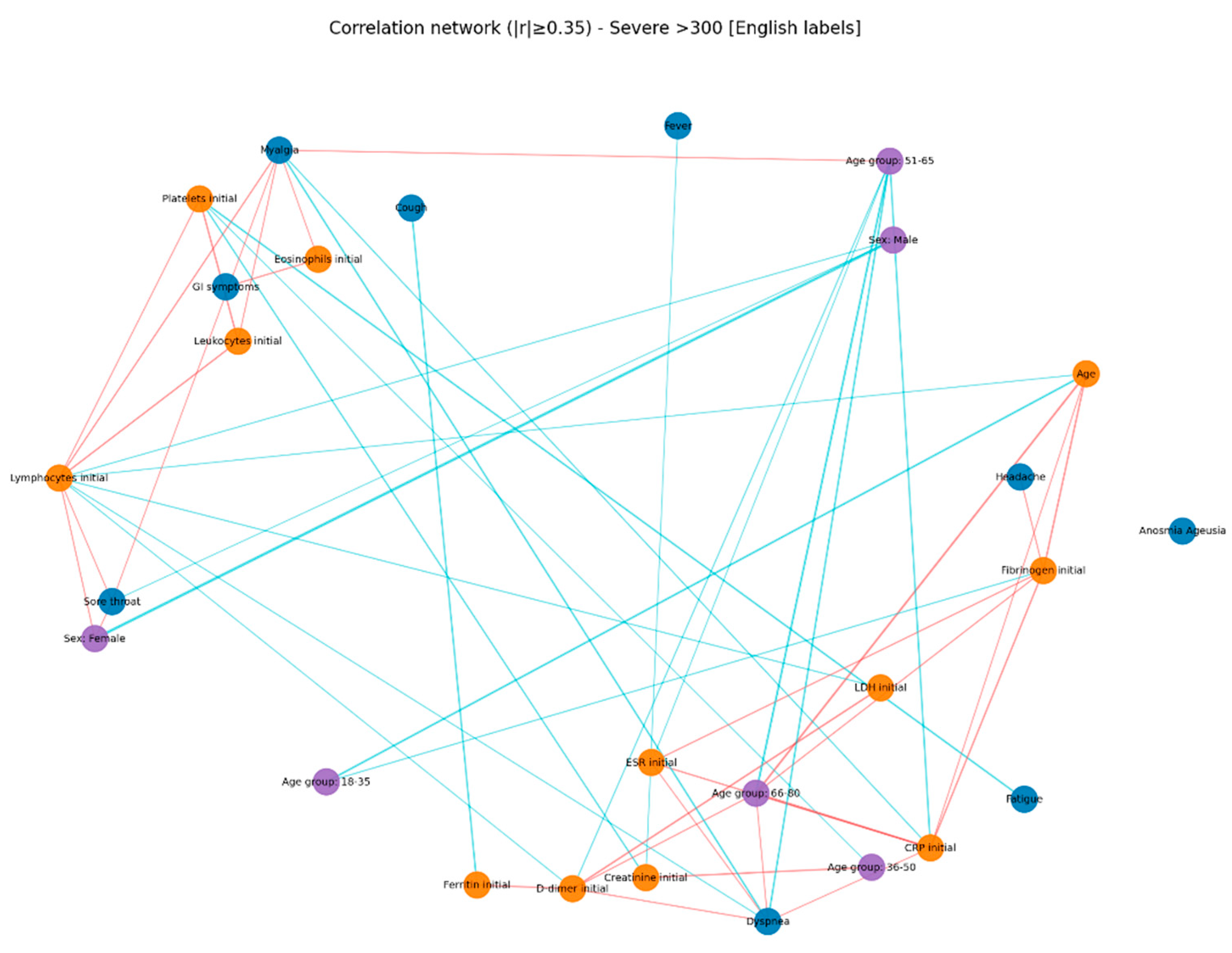

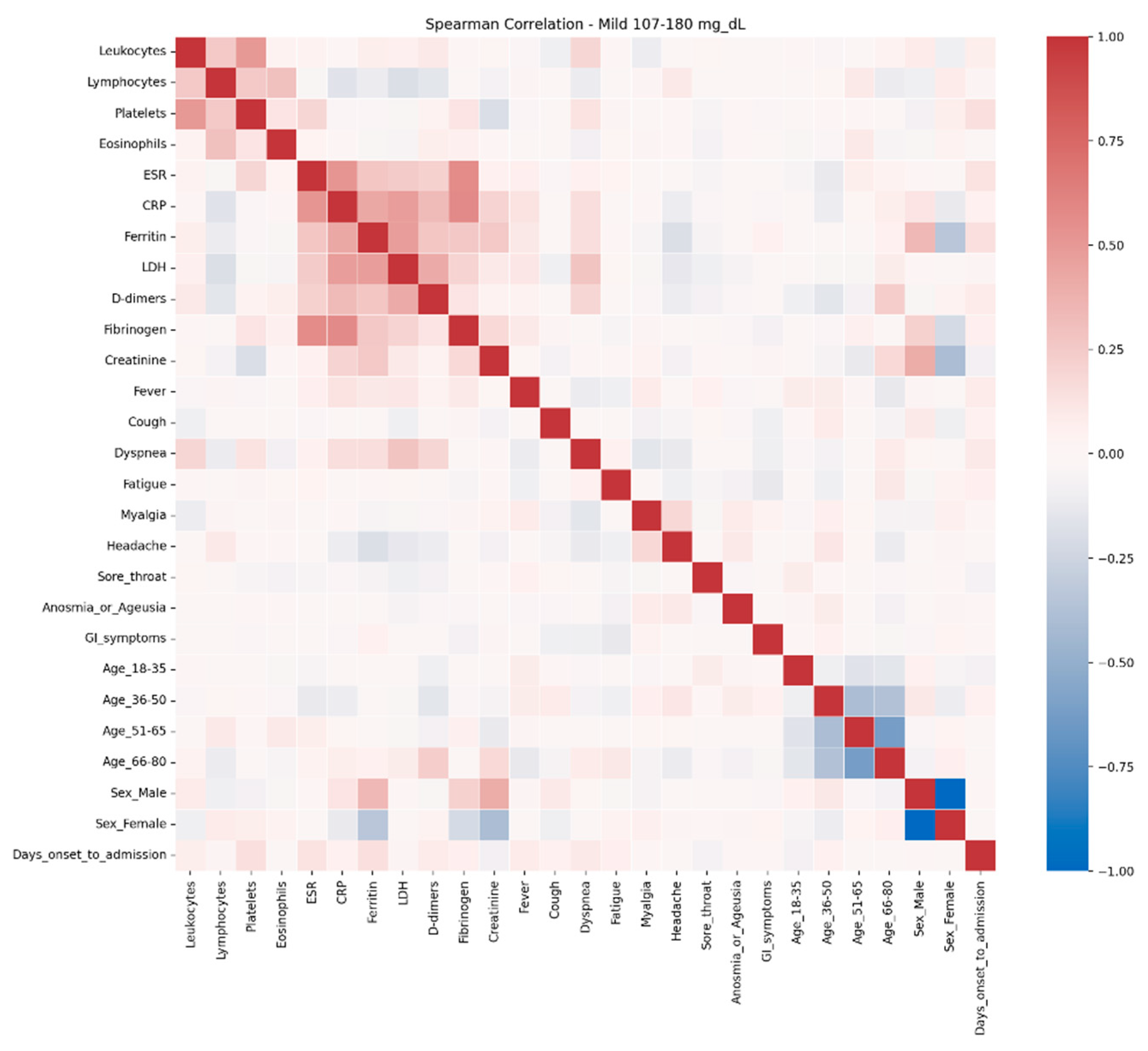

In the present study, correlation network analysis revealed that hyperglycemia severity is associated with a progressive increase in the complexity of interactions among biological, clinical, and demographic variables. In mild hyperglycemia, the profile was dominated by correlations between inflammatory markers and hematologic parameters, suggesting that even slightly elevated glucose levels can trigger a detectable inflammatory response. As hyperglycemia advanced to moderate levels, the inflammatory–hematologic cluster became more consolidated, with additional connections to coagulation markers and renal function, particularly in older patients, indicating broader systemic activation and increased vulnerability to metabolic and endothelial dysfunction. In severe hyperglycemia, the correlation structure became dense, with numerous positive and negative associations, reflecting greater immunologic and hematologic dysregulation. The integration of respiratory and general symptoms (fever, dyspnea, fatigue) into the biological core of the network reflects a more severe clinical expression and a closer interplay between inflammatory responses and clinical manifestations. These patterns suggest that hyperglycemia is not merely a marker of severity but actively contributes to remodeling the inflammatory and hematologic response, with direct implications for the clinical phenotype and patient prognosis. Ceriello A. (2020), in “Hyperglycemia and COVID-19: what was known and what is really new?”, supports the hypothesis that hyperglycemia is not just a marker but an active factor exacerbating inflammation and the procoagulant state [

72].

4.5. Pathophysiological Considerations

The relationship between hyperglycemia and poor prognosis in COVID-19 is complex and bidirectional. SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce hyperglycemia through increased release of counter-regulatory hormones, severe systemic inflammation, and possibly by direct injury to pancreatic β-cells. In turn, hyperglycemia worsens immune dysfunction, increases oxidative stress, promotes endothelial damage, and induces a prothrombotic state, thereby amplifying the pathogenic cascades involved in severe disease [

5,

6,

26].

A major mechanism involves viral binding to the ACE2 receptor, expressed in pancreatic β-cells, hepatocytes, and adipose tissue [

9]. Viral entry may exert direct cytotoxic effects, impairing insulin production and secretion. Systemic inflammation and the acute “cytokine storm” may further aggravate insulin resistance, leading to disruption of glucose metabolism [

10,

11].

Several studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection can significantly disrupt glucose metabolism, leading to hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and in some cases, new-onset diabetes, even in individuals without prior metabolic disorders. These alterations may persist beyond the acute phase, contributing to post-acute sequelae (PASC, or “long COVID”) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. SARS-CoV-2 may also stimulate glycolysis in monocytes, increasing lactate production and consequently serum LDH levels, which are characteristic of severe forms [

26]. For example, Chen et al. (2022) demonstrated that even patients with mild disease exhibited persistent metabolic alterations 2–3 months after recovery (elevated fasting glucose, reduced insulin sensitivity) [

19]. Similarly, Montefusco et al. described persistent hyperglycemia and altered insulin secretion dynamics during convalescence, suggesting that the virus may act both as a trigger and as an accelerator of metabolic dysfunction [

20].

4.6. Therapeutic Implications

The differences observed in antiviral use in our study likely reflect both the greater severity among hyperglycemic patients and the evolution of therapeutic protocols throughout the pandemic. Remdesivir was administered significantly more often in the hyperglycemic group (31.7%) compared with normoglycemics (15.3%) (p < 0.001), suggesting that these patients, being more severely affected (as shown by clinical and biological analyses), more frequently met the criteria for administration in moderate-to-severe forms requiring oxygen therapy. One study explored factors associated with hyperglycemic complications following remdesivir use, reporting more frequent administration in severe cases [

33]. In contrast, Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) was prescribed significantly more often in normoglycemics (43.3%) than in hyperglycemics (28.3%) (p < 0.001), suggesting that antiviral selection was influenced not only by glycemic status but also by treatment availability and protocol changes during the pandemic. The observed differences therefore reflect the temporal context of pandemic waves and resource availability rather than a direct effect of hyperglycemia. During the same period, admission hyperglycemia was less prevalent, and many normoglycemics were hospitalized earlier, when Kaletra was more commonly prescribed. Favipiravir was used more frequently in hyperglycemics (35.1% vs. 27.3%), but without statistical significance. Since it was introduced in later waves and indicated for mild-to-moderate forms, its higher use in hyperglycemics may reflect the need for early treatment in a high-risk population and the limited availability of remdesivir. A meta-analysis showed that favipiravir did not significantly reduce the need for ICU admission or oxygen therapy [

34]. Lack of antiviral treatment was more common among normoglycemics (6.1%) compared with hyperglycemics (1.4%) (p < 0.001), suggesting milder forms or hospitalizations during early phases when access to antivirals was limited.

Regarding immunomodulatory therapy, our data showed significantly greater use of tocilizumab and anakinra in patients with admission hyperglycemia (16.5% and 26.2% vs. 6.5% and 12.4%, p < 0.001). This suggests that these patients more frequently developed severe inflammatory responses requiring IL-6 or IL-1 blockade to control cytokine storm. Hyperglycemia has previously been associated with a proinflammatory state and immune dysfunction, which may exacerbate COVID-19 severity and increase the need for immunomodulatory therapies [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Thus, the observed differences support the hypothesis that admission hyperglycemia may serve as a marker of more severe forms of COVID-19, necessitating both broader-spectrum antivirals and intensive immunomodulation. A study published in Düzce Medical Journal compared the two drugs, suggesting that both can reduce the risk of clinical deterioration; high-flow oxygen requirements and non-invasive ventilation were lower, and hospital stays were shorter in the tocilizumab-treated group (p < 0.001; p = 0.002; p = 0.027) [

36].

The frequent use of corticosteroids in moderate-to-severe forms may contribute to hyperglycemia and requires careful management to avoid iatrogenic complications [

35]. Among the 275 normoglycemic patients at admission, 40% developed hyperglycemia during hospitalization; 94.5% of these received corticosteroids. Newly developed hyperglycemia was not associated with poor prognosis (only 16.2% developed severe/critical forms; 0.9% required non-invasive ventilation/ICU transfer). Furthermore, patients with persistent metabolic alterations may benefit from early lifestyle interventions, nutritional counseling, and pharmacological support to prevent progression to overt diabetes, considering that 29.3% of study patients had glucose > 140 mg/dL at discharge [

43].

4.8. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective and observational design precludes establishing a causal relationship between admission hyperglycemia and COVID-19 outcomes and may introduce recording bias. Second, as a single-center study conducted during a specific period (August 2020 – July 2021), the results may not be generalizable to other populations, regions, viral variants, or therapeutic regimens. In the absence of data on HbA1c, C-peptide, or pancreatic autoantibodies, it was not possible to differentiate the underlying mechanism of hyperglycemia (stress-induced vs. insulin resistance vs. autoimmune insulin deficiency). Likewise, a clear distinction between stress hyperglycemia and newly diagnosed diabetes could not be made.

Nevertheless, the findings indicate admission hyperglycemia as a clinically relevant and easily measurable prognostic marker. Hyperglycemia at admission may reflect both an accentuated systemic inflammatory response and pre-existing metabolic imbalance, being associated with more severe forms of disease, prolonged clinical course, and higher costs. New-onset hyperglycemia and diabetes increase cardiovascular risk and mortality if not managed promptly [

12,

13]. Systematic monitoring of glucose levels at admission and the implementation of careful glycemic control could enable early identification of high-risk patients, optimize therapeutic strategies, and improve resource allocation. Prospective studies and clinical trials are needed to determine whether early intervention and strict glycemic control can improve outcomes and reduce complications, thereby consolidating hyperglycemia as an integrated prognostic factor in COVID-19 management

.