1. Case

A 45-year-old woman was brought in after calling EMS for shortness of breath. She had a known history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and was on long-term warfarin therapy, actively followed in a thrombosis clinic. As the ambulance arrived at the emergency department, she suffered a cardiac arrest. Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) was initiated immediately. After approximately 15 minutes of resuscitation, intravenous thrombolysis was administered for presumptive massive pulmonary embolism.

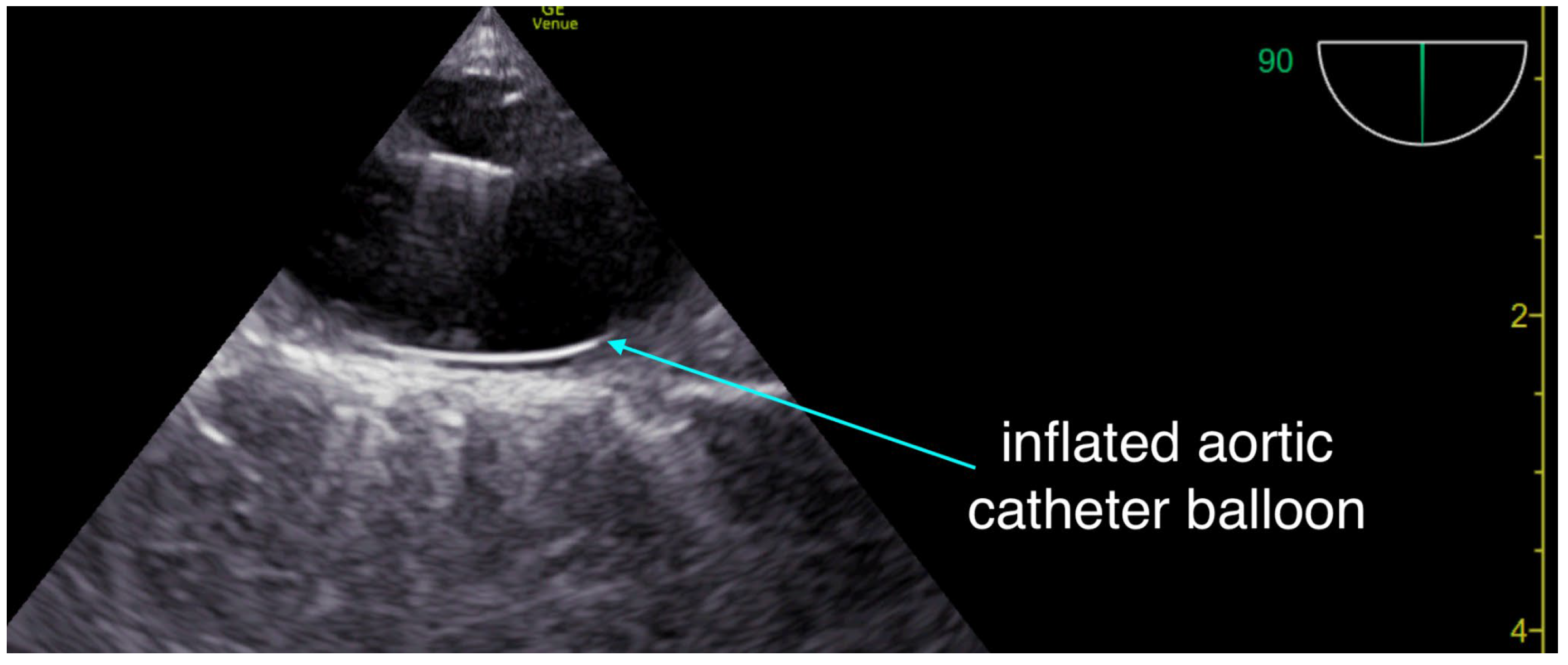

The critical care team arrived and performed resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), which confirmed both the adequacy of chest compression positioning with the mechanical compression device (LUCAS) and the absence of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. The right ventricle was dilated, but no intracardiac thrombus was observed. With no return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after a total of 40 minutes of resuscitation, an aortic occlusion catheter (COBRA-OS, Frontline Medical Technologies, London, ON, Canada) was inserted and inflated at approximately 50 minutes of ongoing resuscitation. About five minutes later, TEE demonstrated cardiac activity consistent with pseudo-pulseless electrical activity (pseudo-PEA), with contractions that were largely ineffective and only minimally opened the aortic valve. By that point, the patient had received six milligrams of epinephrine according to ACLS protocol. The tertiary care center providing mechanical circulatory support was then contacted; however, given the prolonged duration of arrest, the additional time required for transfer, and the absence of effective ROSC, the patient was no longer considered a candidate for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR)

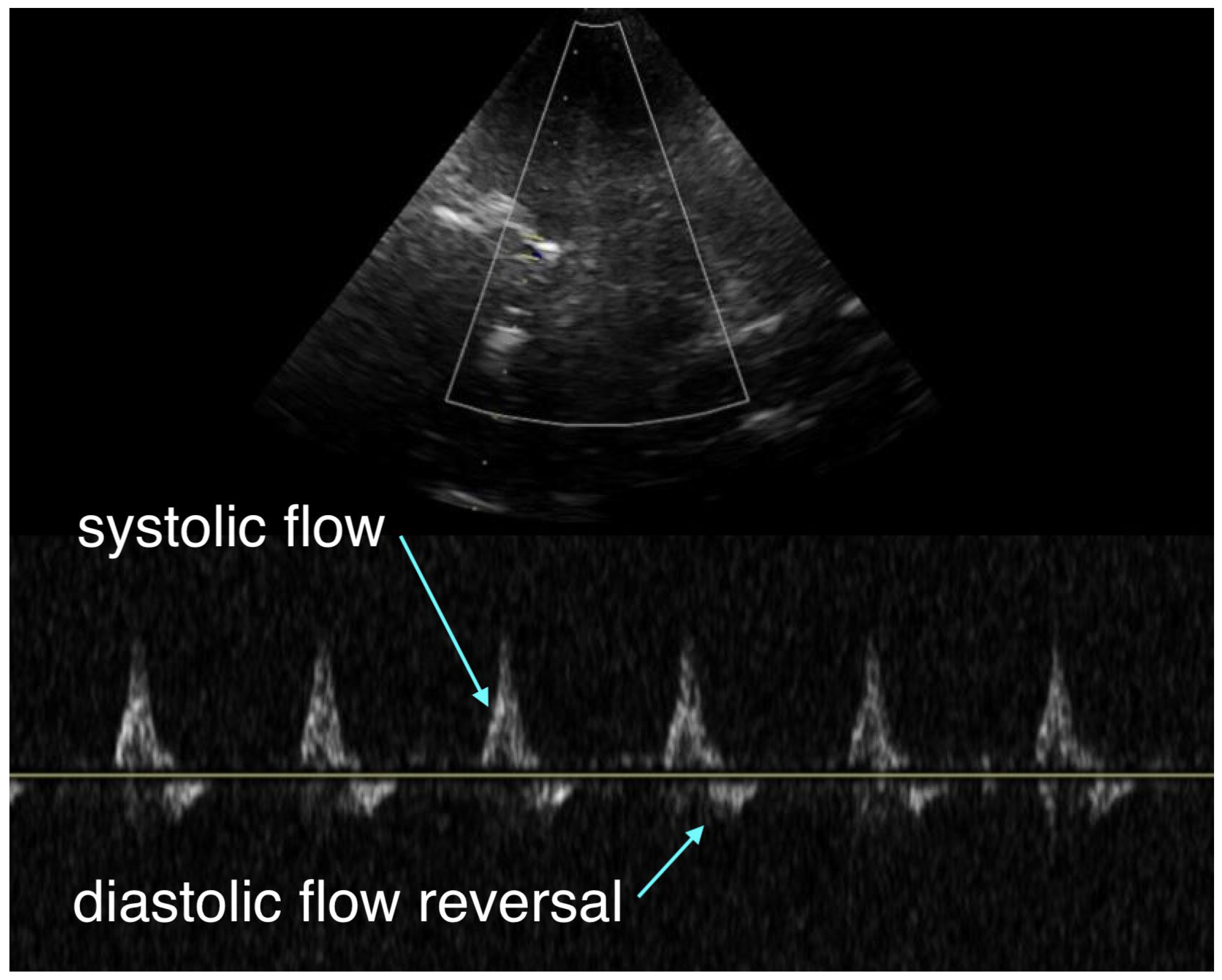

During CPR, transcranial Doppler (TCD) was used to assess intracranial flow. (

Figure 1) It revealed a systolic upstroke but also early diastolic flow reversal and no significant forward flow during the remainder of diastole, which was thought to reflect severely impaired cerebral perfusion, either from markedly vasoconstricted intracerebral arterioles secondary to epinephrine administration or from elevated intracranial pressure.

At approximately 55 minutes of resuscitation, biventricular systolic function showed improvement on a hi-dose epinephrine drip, and the aortic catheter balloon was deflated to avoid excessive afterload and to allow perfusion of the lower body. Resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) at that time demonstrated a normal left ventricular ejection fraction with an underfilled ventricle, alongside a dilated right ventricle with a TAPSE of approximately 10–11 mm. Blood pressure was adequate at around 150/90 mmHg; however, capillary refill time remained markedly prolonged at more than five seconds.

Given the high doses of epinephrine required to maintain this hemodynamic state, and the presence of predominantly right-sided cardiogenic shock, the tertiary care center was recontacted. With this new development of sustained ROSC, the patient was accepted for transfer for possible mechanical circulatory support. Unfortunately, significant delays followed: more than 30 minutes were required to secure an ambulance, and transport to the receiving facility took an additional 35 minutes.

During transport, hemodynamics were continuously monitored using resuscitative TEE. The epinephrine infusion was continued. End-tidal CO2 remained at greater than 40 mmHg, and arterial blood pressure stayed above 100 mmHg systolic. However, pulse pressure was narrow, with diastolic pressures generally ranging between 70 and 90 mmHg.Upon arrival at the tertiary care center, the patient was assessed by the treating team. The Glasgow Coma Scale was 3, pupils were minimally reactive, and no gag reflex was present. Repeat transcranial Doppler demonstrated the same pattern of systolic flow with early diastolic flow reversal and an absence of forward flow during the remainder of diastole.

An attempt was made to wean the high doses of epinephrine and substitute vasopressin and norepinephrine. This, however, resulted in profound hypotension and a clear, significant deterioration in biventricular cardiac function. An urgent multidisciplinary discussion was held, and the decision was made not to initiate mechanical circulatory support given the absence of signs of life nearly two hours after ROSC. The patient’s family was subsequently informed, and a joint decision was made to withdraw care.

2. Discussion

While this case was undoubtedly tragic and left a lasting impact on much of the treating personnel due to the patient’s youthful age, there are several noteworthy points that prompted us to report it.

-

a.

Access to Mechanical Circulatory Assistance for Community Hospital Patients

This case illustrates the urgent need for health systems to expand rapid access to mechanical circulatory support for unstable patients. Although some randomized controlled trials have reported neutral results, recent systematic reviews demonstrate that ECPR for refractory cardiac arrest is associated with improved survival and favorable neurological outcomes. [

1] This principle also applies to cardiogenic shock, which is frequently encountered in the post-resuscitation setting, with recent data from the DANGER trial further supporting the benefits of mechanical circulatory support in this population. [

2]

The effectiveness of ECPR is, however, extremely time dependent, with survival strongly influenced by the duration of low-flow prior to extracorporeal support. In most current systems, patients must be transported to an ECPR-capable center where the ECMO team awaits and initiates cannulation. While effective for those who collapse nearby, this model largely excludes patients located farther away, as transfer delays often render them ineligible for ECPR.

A promising alternative is the hub-and-spoke model, in which ECMO can be initiated at satellite hospitals or by mobile teams prior to transfer to a tertiary care facility. Importantly, hub-and-spoke preserves the existing hospital-based structure: expert teams remain in their centers and continue their usual clinical responsibilities until called upon for cannulation at a spoke site, minimizing disruption to the system. This approach has been demonstrated by the Minnesota mobile ECPR consortium, which has shown the model to be both feasible and effective, particularly in achieving favorable neurological outcomes. [

3] In parallel, a recent Monte Carlo modeling suggests that hub-and-spoke ECPR model could increase accessibility (capture rate) and survival, highlighting the need to evaluate this model as a potential strategy to improve equity of care. [

4]

b. Trans-Cranial Doppler in Cardiac Arrest

The second point raised by this case is the potential use of transcranial Doppler (TCD) during cardiac arrest to assess intracranial flow. While some work has been published in the pediatric literature [

5], our team has also performed exploratory examinations during resuscitation. This modality may help identify patients in whom epinephrine-induced vasoconstriction could be particularly harmful, by creating a loss of effective energy transfer between arterioles and capillaries such that excessive vasoconstriction raises the critical closing pressure and prevents capillary perfusion despite apparently adequate arterial pressure (arteriolo-capillary uncoupling). [

6]

Transcranial Doppler provides a window into intracranial hemodynamics, arguably the most important determinant of outcome during cardiac arrest resuscitation. In this case, the absence of diastolic forward flow with early diastolic flow reversal (

Figure 1) was interpreted as either excessive vasoconstriction of intracerebral arterioles impairing perfusion, or significant cerebral edema causing elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). Optic nerve sheath ultrasound could have helped differentiate between these two mechanisms, but was not performed. Given the very limited literature, these observations remain theoretical and warrant further study, as we currently lack tools to tailor resuscitative strategies directly to cerebral flow.

c. Resuscitative TEE as a Transport Monitoring Tool

Another important consideration is the potential use of resuscitative TEE as a continuous hemodynamic monitor during the transfer of unstable patients. While definitive outcome studies are still pending, its diagnostic utility is clear: it ensures optimal chest compression positioning and reliably guides the placement of advanced resuscitation cannulae. ([

7,

8,

9];

Figure 2) By contrast, standard inter-hospital transport monitoring is generally limited to an arterial line, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, capnography, and a basic transport ventilator, which limits diagnostic capabilities and delays the rapid correction of physiologic abnormalities.

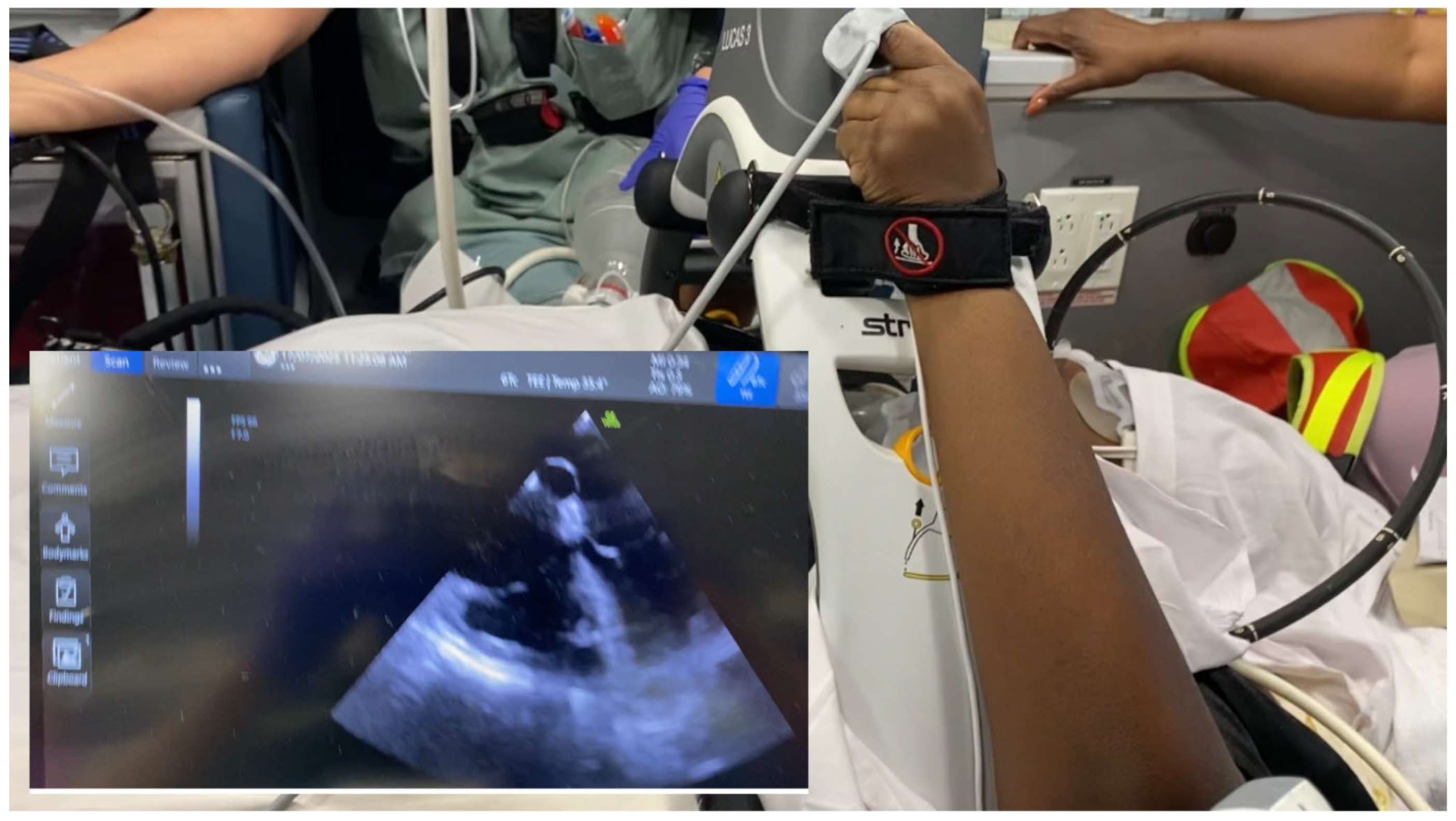

Portable ultrasound devices coupled with an indwelling TEE probe provide high-quality imaging during transport, which would be impossible to achieve with surface ultrasound given the density of equipment straps surrounding the patient, and the additional risk of attempting transthoracic imaging in a moving vehicle. Our team has used this technique in several inter-hospital transfers and has found it to be both safe and reliable.

Practically, the probe is disconnected from the ultrasound console during patient movement, reconnected once the patient is secured in the ambulance, and again briefly disconnected at arrival before being reattached in the receiving intensive care unit.

For clinicians already performing resuscitative TEE, extending its use into transport, whether from the emergency department to the intensive care or to another institution, represents a viable and effective option to enhance monitoring and safety.

Figure 3 provides an example of intra-transport TEE imaging.

d. Resuscitative Aortic Occlusion Catheters in Non-Traumatic Cardiac Arrest

Our group has previously published a case of aortic occlusion catheter use in cardiac arrest and we eagerly await the results of the ongoing REBOARREST trial. [

10] From a physiologic standpoint, optimizing cerebral and coronary perfusion by improving the central-to-coronary/cerebral pressure gradient, rather than relying on epinephrine-driven vasoconstriction, would be a superior approach. As already stated, excessive vasoconstriction risks disrupting the arteriolo–capillary interface when it goes beyond restoring normal vascular tone. [

6] It is important to recall that the primary purpose of epinephrine is to restore coronary perfusion pressure in hopes of achieving ROSC, with intracerebral vasoconstriction being an undesirable side effect. Occlusion of the distal circulation allows for an increase in proximal aortic pressure which achieves the goal of increasing coronary perfusion pressure without the unwanted effect of cerebral microcirculatory vasoconstriction. These considerations suggest that the routine use of aortic occlusion catheters in non-traumatic cardiac arrest may represent a less physiologically damaging means of restoring both coronary and cerebral perfusion.

In this case it is impossible to know whether ROSC occurring soon after balloon inflation was related or simply coincident with the thrombolytic effect.

3. Conclusion

Cardiac arrest is a rapidly evolving field, and conventional ACLS is no longer sufficient beyond the initial minutes of management. Survival should not depend on something as arbitrary as geographic location, yet current systems restrict access to advanced resuscitation strategies such as ECPR to patients who collapse near an ECMO center. Because ECPR is extremely time sensitive, system reorganization is urgently needed to expand timely access, whether through hub-and-spoke networks or prehospital models.

At the same time, emerging adjuncts, including femoral arterial lines, resuscitative TEE, and aortic occlusion catheters, warrant further study, as accumulating clinical experience suggests they may meaningfully influence outcomes. In parallel, technologies such as trans-cranial Doppler sonography offer the potential to personalize resuscitation and better target neuroprotective strategies.

The future of resuscitation will depend on both equitable system design and personalized interventions, working together to improve survival and neurological outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R., L.L., G.S.; data curation, P.G..; writing—original draft preparation, P.R., L.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L., P.G., G.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient’s next of kin to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Frontline Medical (London, Ontario, Canada) for donating the COBRA-OS Catheters to the Santa Cabrini Critical Care team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TEE |

Trans-Esophageal Echocardiography |

| TCD |

Transcranial Doppler |

| ECPR |

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| ICP |

Intracranial pressure |

| ROSC |

Return of spontaneous circulation |

| ECMO |

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| CPR |

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

References

- Reddy, S.; Garcia, S.; Hostetter, L.J.; Finch, A.S.; Bellolio, F.; Guru, P.; Gerberi, D.J.; Smischney, N.J. Extracorporeal-CPR Versus Conventional-CPR for Adult Patients in Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest– Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2024, 40, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, J.E.; Engstrøm, T.; Jensen, L.O.; Eiskjær, H.; Mangner, N.; Polzin, A.; Schulze, P.C.; Skurk, C.; Nordbeck, P.; Clemmensen, P.; et al. Microaxial Flow Pump or Standard Care in Infarct-Related Cardiogenic Shock. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartos, J.A.; Frascone, R.; Conterato, M.; Wesley, K.; Lick, C.; Sipprell, K.; Vuljaj, N.; Burnett, A.; Peterson, B.K.; Simpson, N.; et al. The Minnesota mobile extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation consortium for treatment of out-of-hospital refractory ventricular fibrillation: Program description, performance, and outcomes. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 29-30, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroux, L.; Grunau, B.; Lecuyer, P.; Dennis-Benford, N.B.; Lamhaut, L.; Cheskes, S.; Cournoyer, A.; Cavayas, Y.A. Optimizing extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation delivery for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Resuscitation 2025, 110743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordanova, B.; Li, L.; Clark, R.S.B.; Manole, M.D. Alterations in Cerebral Blood Flow after Resuscitation from Cardiac Arrest. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 174–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rola, P.; Kattan, E.; Siuba, M.T.; Haycock, K.; Crager, S.; Spiegel, R.; Hockstein, M.; Bhardwaj, V.; Miller, A.; Kenny, J.-E.; et al. Point of View: A Holistic Four-Interface Conceptual Model for Personalizing Shock Resuscitation. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, F.; Diederich, T.; Owyang, C.G.; Stancati, J.A.; Dudzinski, D.M.; Panchamia, R.; Hussain, A.; Andrus, P.; Via, G. Resuscitative Transesophageal Echocardiography in Critical Care. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douflé, G.; Roscoe, A.; Billia, F.; Fan, E. Echocardiography for adult patients supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruit, N.; Ferguson, I.; Dieleman, J.; Burns, B.; Shearer, N.; Tian, D.; Dennis, M. Use of transoesophageal echocardiography in the pre-hospital setting to determine compression position in out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2025, 209, 110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rola, P.; St-Arnaud, P.; Karimov, T.; Brede, J.R. REBOA-Assisted Resuscitation in Non-Traumatic Cardiac Arrest due to Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report with Physiological and Practical Reflections. J. Endovasc. Resusc. Trauma Manag. 2021, 5, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).