1. Introduction to Network Reputation Assessment

In the face of escalating network security threats and increasingly sophisticated attack methods, the effective appraisal and evaluation of the security and trustworthiness of pivotal network assets, such as web servers, email servers, and URLs, become imperative. Utilizing reputation scores as evaluative standards and resorting to tailored protective measures can potentially minimize Internet-associated risks. Network reputation symbolizes the degree of trust conferred on resources and services by the stakeholders in information technology and network communication, and is derived from information related to interactions and feedback amongst the entities. It steers users towards informed trust decisions by gauging the reliability of an entity’s behavior and the veracity of associated content, thus mitigating the risks that users may potentially encounter during the utilization of online resources[

1,

2].

Reputation assessment systems analyze the behavioral patterns of IP addresses or network nodes, accumulating data about their activities. They establish criteria for measuring reputation, continually evaluating entities to support informed decision-making and to improve network service quality[

3,

4]. For example, Cisco’s IronPort anti-spam appliances use the SenderBase to compute reputation scores for emails by examining more than 120 parameters, which contribute to determining the likelihood of an email being spam[

5]. Talos Intelligence actively monitors the online reputation of IP addresses, assigning them ratings such as ’excellent’, ’neutral’, or ’poor’[

6]. Sender Score, similar to a credit score system, assesses domain reputation over time and calculates a reputation score[

7]. TrustedSource applies real-time analysis protocols, leveraging McAfee’s extensive global security infrastructure to assign reputation scores to various digital assets[

8]. Microsoft’s Smart Network Data Services (SNDS) provides insights into domain reputation through metrics like the volume of emails delivered to Microsoft’s spam traps and the rate of user complaints[

9]. The ReputationAuthority system analyzes domain names and IP data, conducts automated anti-spam and anti-virus screening by examining the content and origin of messages, and provides comprehensive reputation assessments for IPs or domains[

10]. Tencent’s Threat Intelligence Cloud Search Service (TICS) gathers global intelligence by monitoring IP address activities and assigning descriptive tags to categorize them [

11].

2. Methods of Reputation Assessment

The algorithms used to assess reputation are primarily categorized into three groups: reputation evaluations founded on statistics, those built on similarity, and ones constructed on machine learning. Algorithms predicated on statistical evaluations harness professional experience and knowledge, employing statistical analysis tools to quantify reputation scores. Methods developed on the basis of similarity measure reputation levels through standard parameter-based similarity assessments. Machine learning-based evaluations predict the reputation state by extracting attributes and utilizing machine learning algorithms. Subsequent sections will delve deeper into these three kinds of reputation evaluation methods, as well as their application contexts.

2.1. Reputation Assessment Based on Statistical Algorithms

2.1.1. Reputation Assessment Through Feedback Analysis

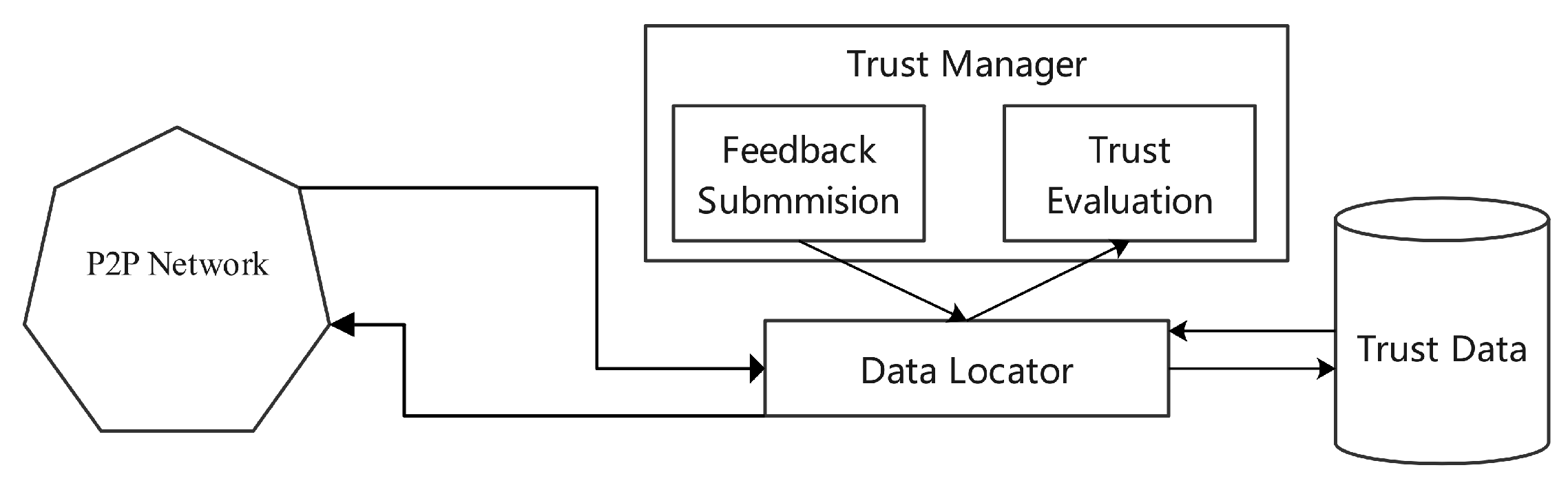

Li et al. proposed the PeerTrust protocol, a feedback-centric trust model tailored for peer-to-peer (P2P) network environments, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Each peer within the network embodies a cohesive system consisting of a trust manager, a micro-database, and a locator. The trust manager employs a set of variables to compute a normalized reputation score over a defined time interval. The variables include the total number of transactions denoted by

, the frequency of transactions

, the level of satisfaction

, the credibility of feedback

, the transaction context

, and the community context

. These elements are aggregated by applying weighting coefficients

and

, as delineated in Equation (

1):

Regarding cloud services, reliability can be assessed by adaptively altering the weight values assigned to different inputs such as cloud service feedback, historical feedback, and the initial trust level of users prior to transactions [

12]. The STRAF model integrates consumer feedback with similarity preferences to provide a holistic trust assessment for cloud services [

13].

2.1.2. Reputation Assessment Utilizing Statistical Inference

Yang et al. [

14] introduced a statistical model to assign reputation scores within P2P networks based on mathematical statistics. For instance, to construct a confidence interval for a node j’s reputation drawn from a sample of size n with a mean denoted as

, it is assumed that

approximates a normal distribution expressed as

. The confidence interval for the reputation value

, at a confidence level of

, is computed via Equation (

2):

Zheng et al. [

15] conducted a statistical exploration of IP address access frequencies within a specific timeframe, using a mirrored data stream. By defining threshold conditions based on typical access rates and request volumes, they fashioned a procedure to ascertain the reputation of IP addresses.

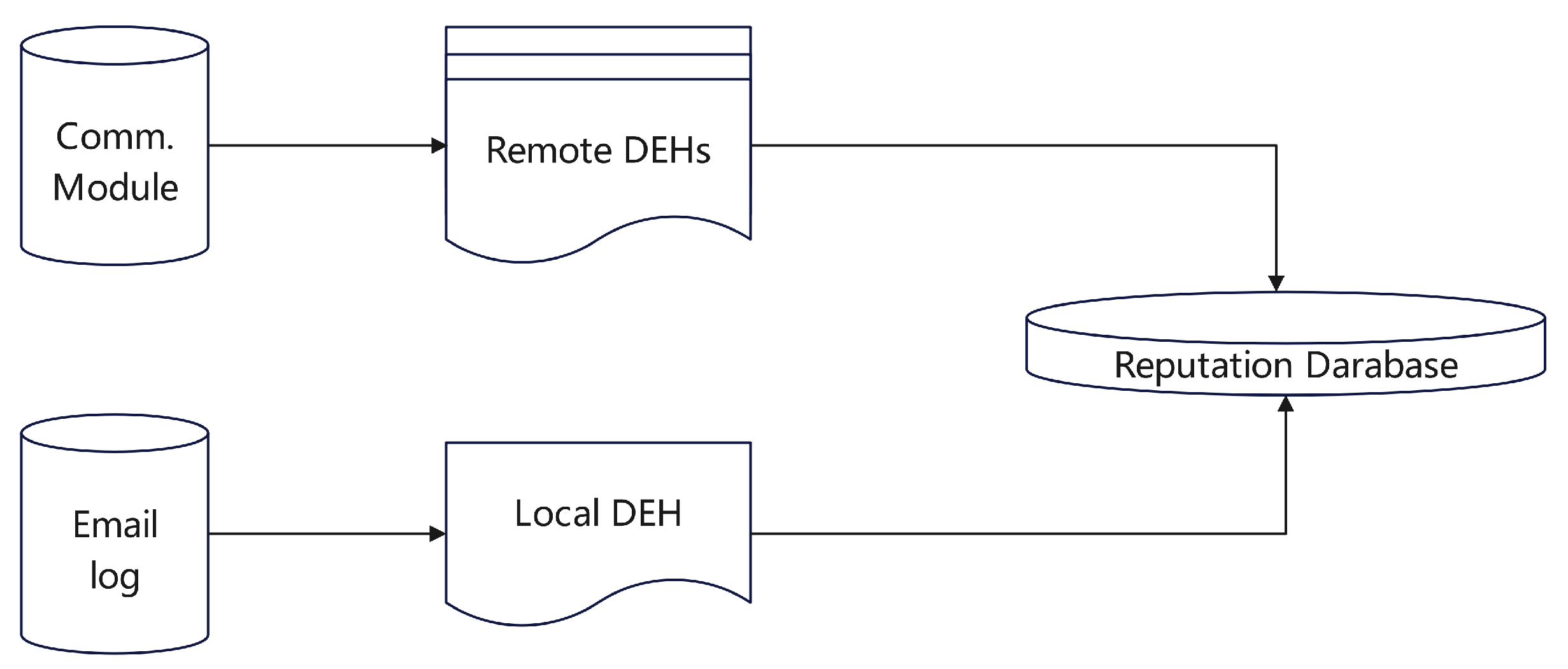

2.1.3. Collaborative Email Reputation System

Xie et al. [

16] developed a novel system known as the Collaborative Automatic Email Reputation (CARE), which operates across various domains. This system harnesses historical email data complemented by information shared among partner domains to foster a comprehensive reputation database.As illustrated in

Figure 2,featuring a Domain Email History (DEH) database that documents email exchanges over a set period. The integration of this local and global data, coupled with precise weighting, enables the derivation of an aggregate reputation score.

2.1.4. Behavior-Based Reputation Assessment

Chen et al.[

17] synergistically combined the concepts of Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and the Internet of Things (IoT) to devise a novel reputation mechanism, termed IoTrust. The cross-layer authorization strategy encompassing five hierarchical levels: the object layer, the node layer, the SDN control layer, the organizational layer, and the reputation management layer. The tripartite mechanism of reputation evaluation, beginning with the behavioral and status verification of network entities. This process is followed by an assessment within a defined evaluation window, culminating in the assignment of a reputation score based on these assessments.

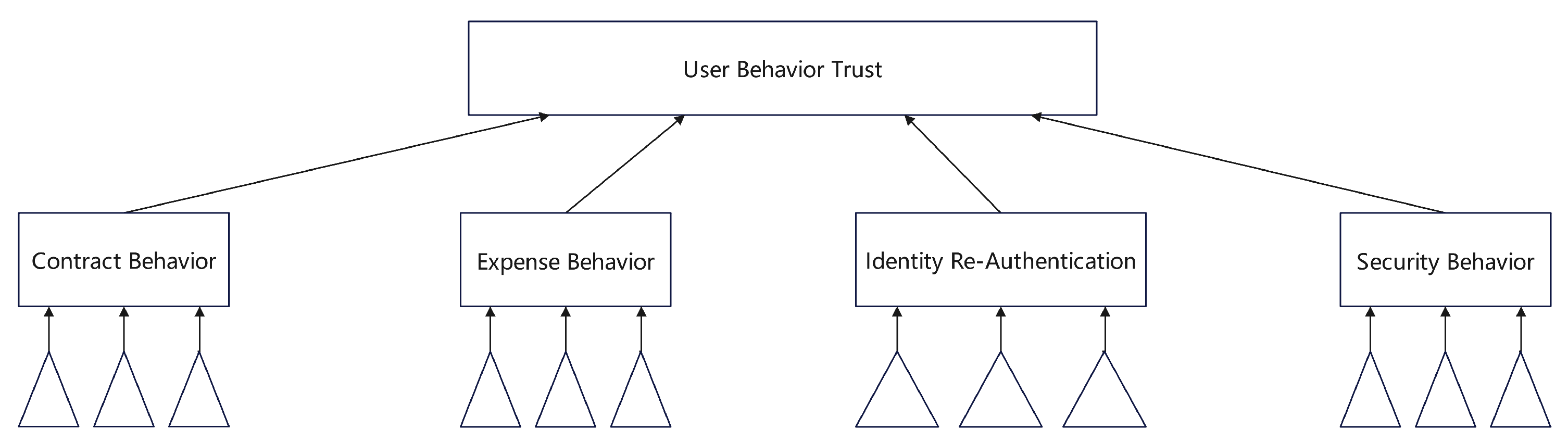

Tian et al.[

18] deconstructed the concept of user reputation into four principal facets: Security Behavior, Contract Performance, Payment Compliance, and Identity Authentication. Each of these facets was further segmented into constituent evidential elements. The resulting mathematical formulation, represented by Equation (

3), embodies the concept of "gradual accumulation and rapid depreciation" in the context of reputation building. In this equation, the symbol

denotes the weighting coefficients that harmonize the impact of the behavior’s duration against incidents of anomalous activities. The dynamic weighting of each reputational component aims to reflect accurately the temporal progression of an entity’s reputation.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical Model for User Behavior Trust Evaluation in Cloud Computing

Figure 3.

Hierarchical Model for User Behavior Trust Evaluation in Cloud Computing

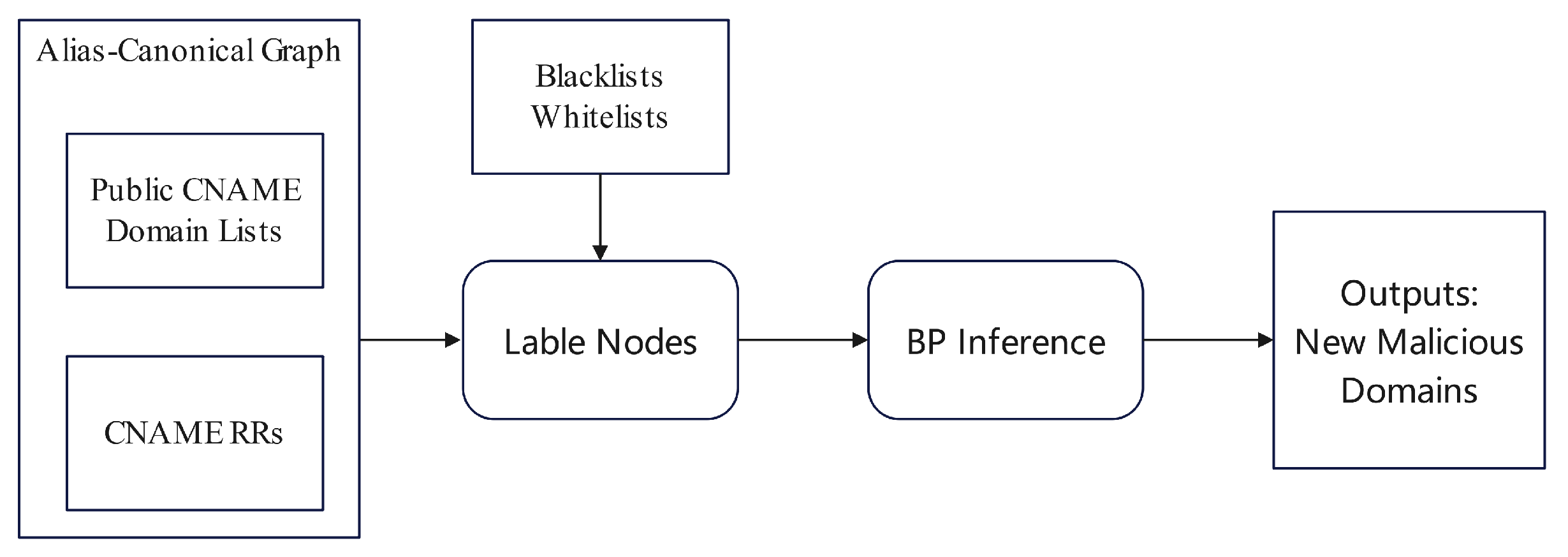

2.1.5. Domain Reputation Assessment Based on Alias-Canonical Graphs

Peng et al.[

19] carried out a comprehensive study on domain names captured within DNS CNAME resource records that do not resolve directly to an IP address. The study unveiled a noteworthy pattern connecting such domains with the affiliated malicious counterparts. These domains, when associated with known malicious entities, have a heightened risk of also being malicious in nature. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the methodology begins with the construction of an alias-canonical graph derived from the DNS CNAME records. Domains within the graph are then classified as either malicious, benign, or indeterminate, depending on correspondence with existing blacklists or whitelists. To calculate the probability of maliciousness for each undetermined domain, the study implemented a Belief Propagation (BP) algorithm. Integral to the algorithm are two parameters: the initial prior probability of a node

(indicating node

i’s propensity to assume a state

), and the conditional probability

(reflecting the likelihood of state

’s influence by state

). Through Equations (

4) and (

5), the BP algorithm iteratively adjusts and relays messages

between adjacent nodes. The process continues until the marginal probabilities stabilize, culminating in a determination of the malicious probability for each unknown domain.

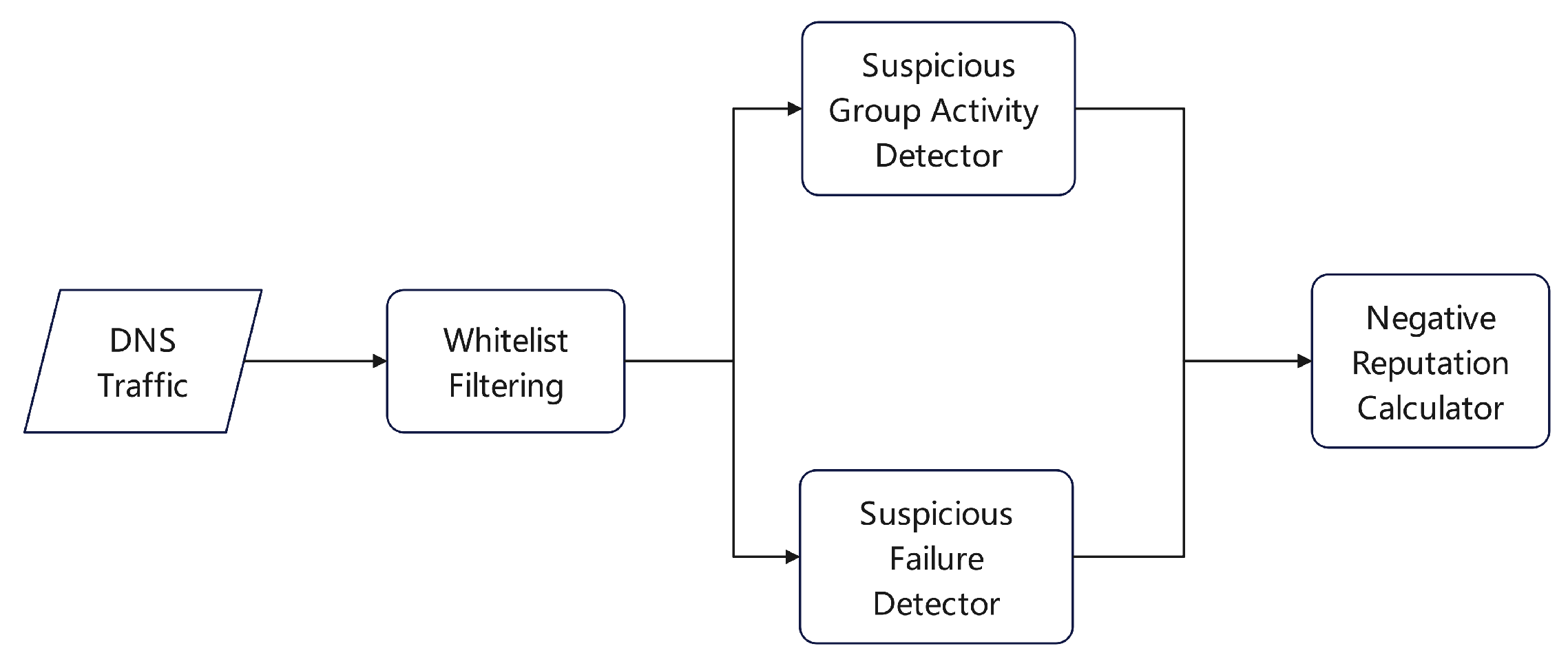

2.1.6. Botnet Reputation Assessment Based on DNS Queries

Sharifnya et al.[

20] developed a mechanism for assigning reputation scores to hosts assumed to be involved in botnet activities. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the system collects DNS query logs at the end of each temporal interval, examining records with common attributes. The system applies statistical methods, such as the Kullback-Leibler divergence and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, to identify hosts that produce an abnormal quantity of suspicious domains through algorithmic generation, subsequently organizing them into a group activity matrix labeled as suspicious. Simultaneously, the system detects hosts associated with a consistent rate of DNS query failures and incorporates this information into a suspicious failure matrix. The overall reputation score for each host is calculated by integrating insights from both matrices.

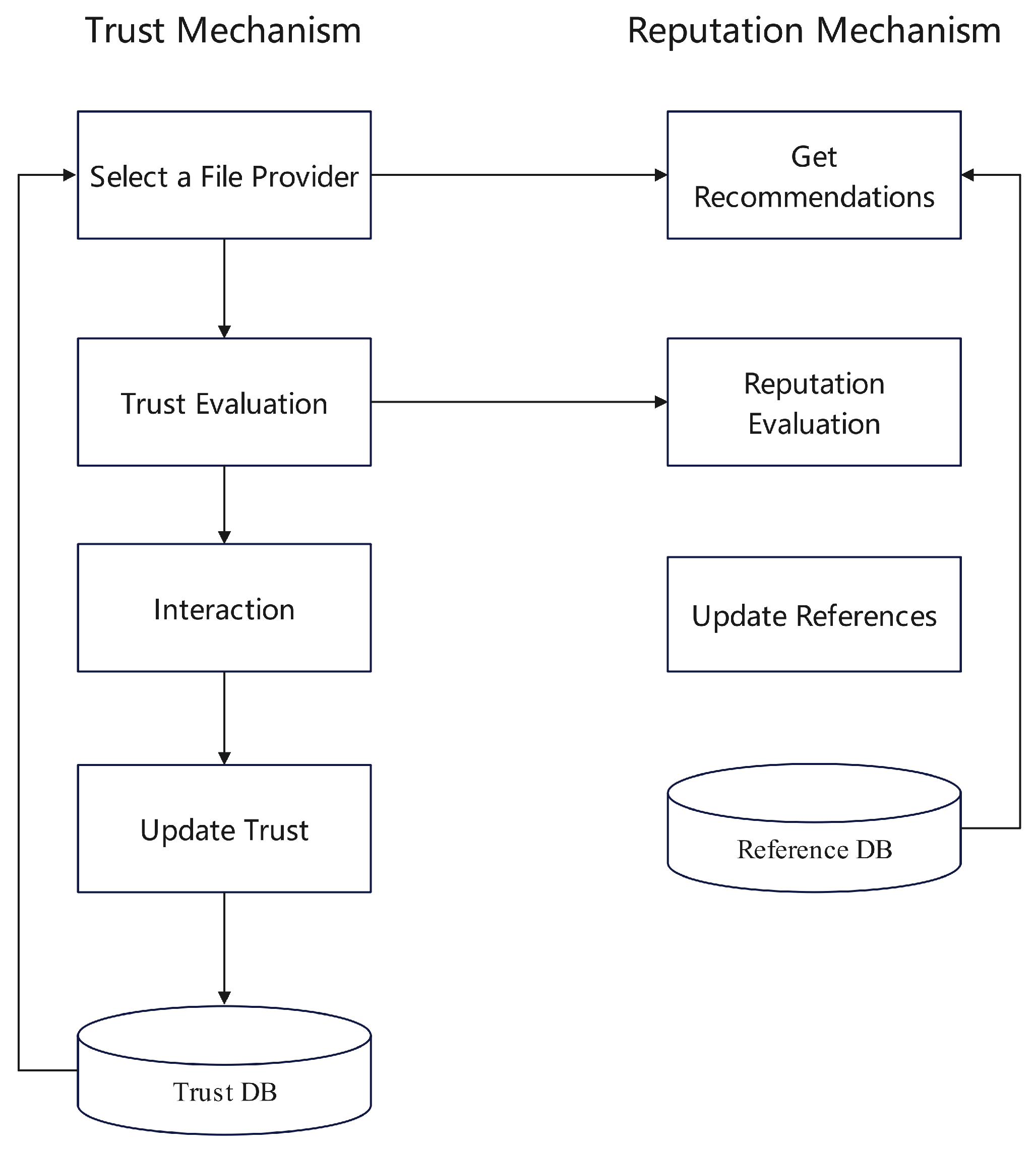

2.1.7. Reputation Assessment Based on Bayesian Networks

Wang et al. [

21] proposed a methodology for reputation assessment utilizing Bayesian networks, considering the complex and situational aspects of reputation. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the model considers two dimensions of feedback—authenticity and similarity—and assigns respective weights to each. The reputation score for a file is influenced by factors such as file type, quality, and the reliability of its availability for download. By evaluating these dimensions, the method determines a comprehensive reputation profile for a file server.

2.2. Reputation Assessment Based on Similarity

2.2.1. Assessment Derived from Domain Information

Fukushima et al. [

22] proposed a reputation evaluation method based on domain names and IP registration addresses. The method allocates IP address blocks to each Autonomous System (AS). Each IP address within these blocks is associated with a domain name managed by a registrar. The authors’ approach involves inspecting the reputation of particular IP address ranges and registrars that are frequently used by acknowledged attackers, thus forming a blacklist informed by the reputations of these entities. During the reputation assessment, domain information extracted through the hierarchical structure is compared against the blacklist.

2.2.2. Header Information-Based Assessment

Esquivel et al. [

23] implemented network measurement techniques to determine distinct TCP packet header signatures characteristic of spam botnets. Initial verification involves checking the "Sender Policy Framework" (SPF) records within the Domain Name System (DNS) to verify the legitimacy of the sender’s email provider. The investigation continues with "Neighbor Name Tests" and "Keyword Tests" to scrutinize the information in the headers. The IP address’s potential for malignancy is deduced from a similarity analysis with known signatures. Lastly, TCP fingerprint characteristics are cross-referenced with known profiles, such as those from the Srizbi botnet, to conduct a thorough reputation assessment.

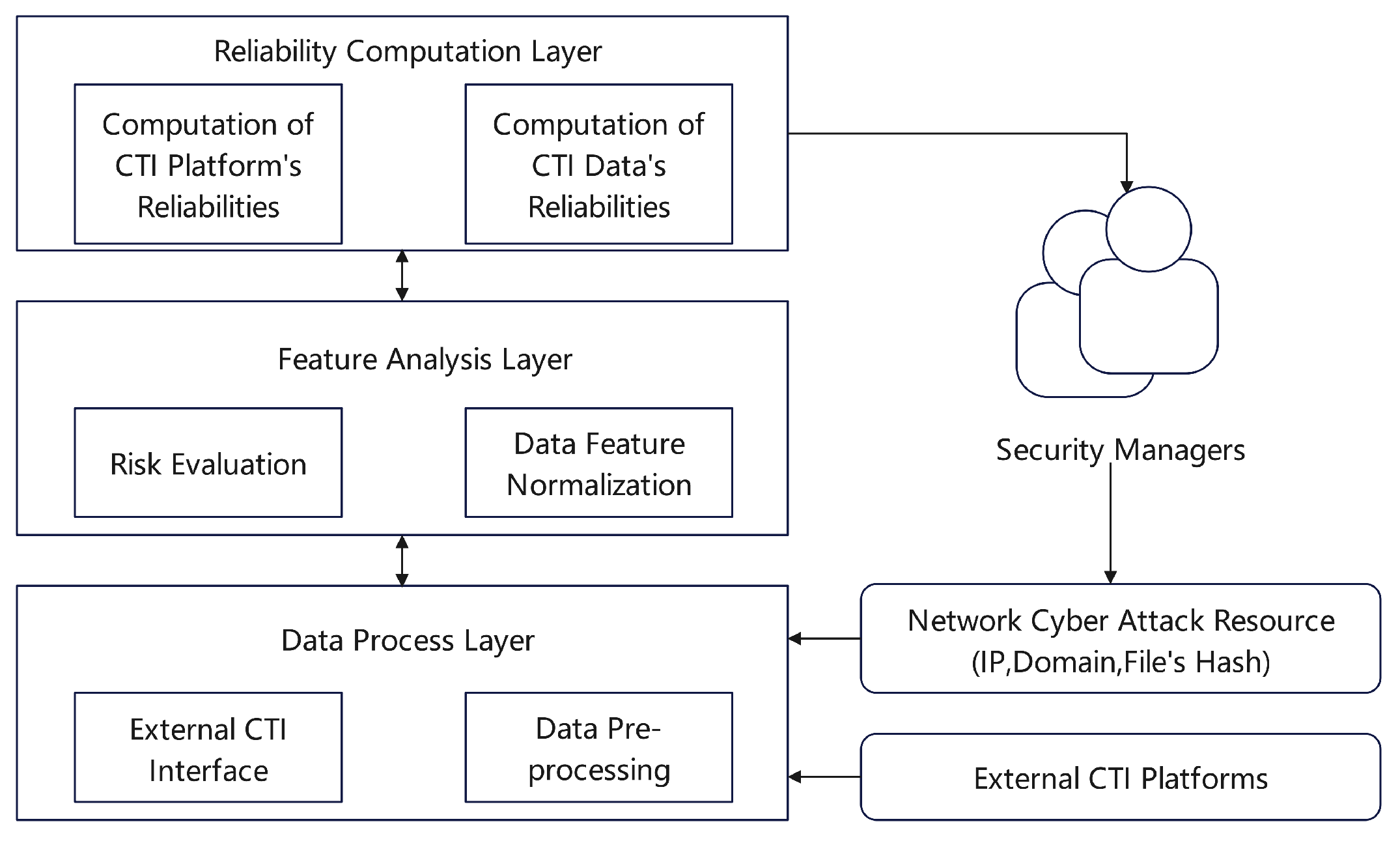

2.2.3. Network Threat Information-Based Assessment

Gong et al. [

24] developed a procedure for evaluating the reputation of network entities by integrating data from Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems. As depicted in

Figure 7, the method is structured into three consecutive stages: data collection, feature analysis, and the computation of reputation scores. The data collection phase amalgamates inputs from security surveillance systems with data pooled from network threat intelligence sources. It also compiles records from malware attacks, honeypot engagements, and security incident responses. In the feature analysis phase, the data attributes are carefully examined; this is followed by a reputation rating procedure assessing the veracity of each Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) input. The Mahalanobis distance metric is employed to evaluate the divergence from expected behavior patterns.

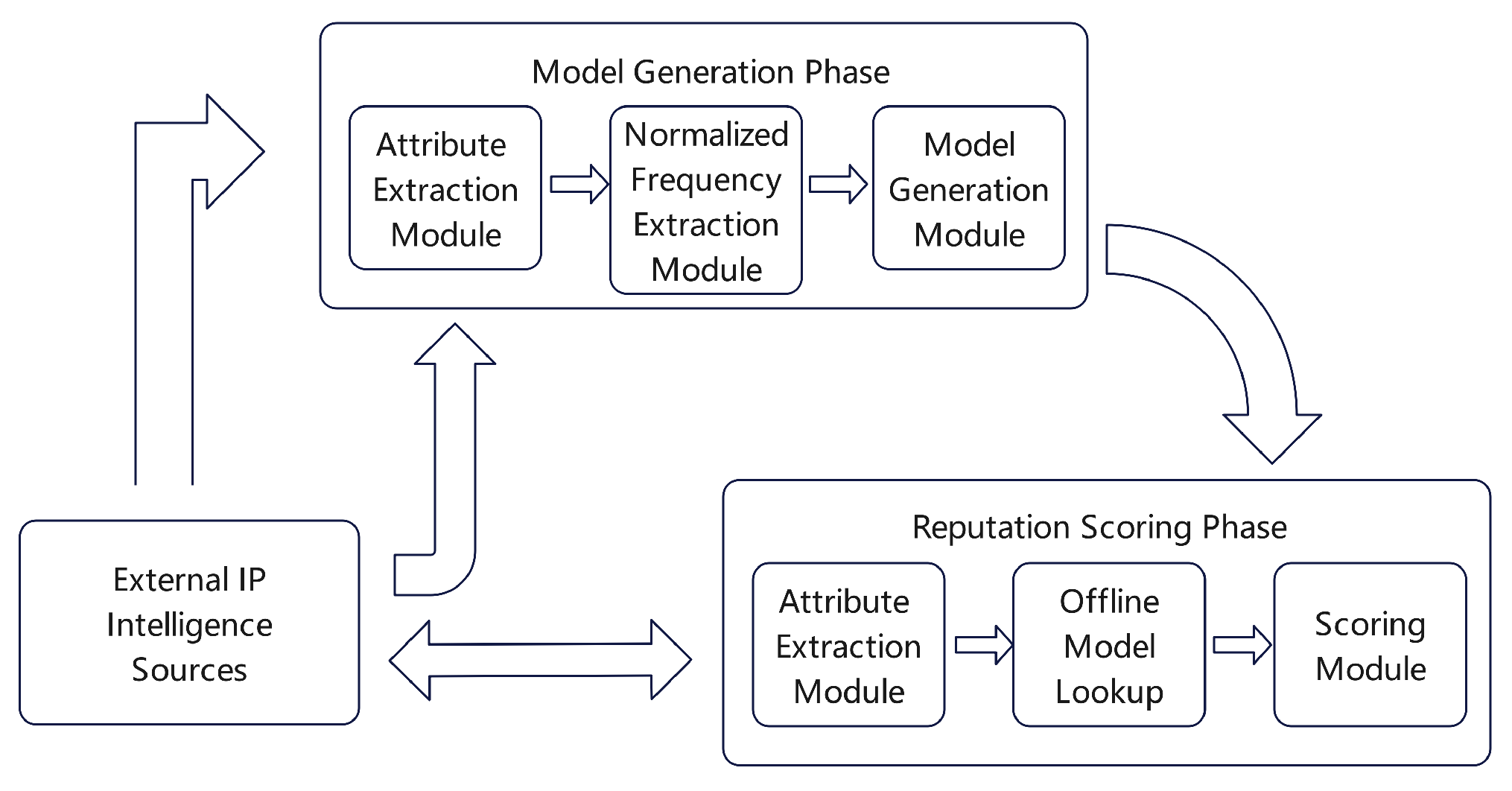

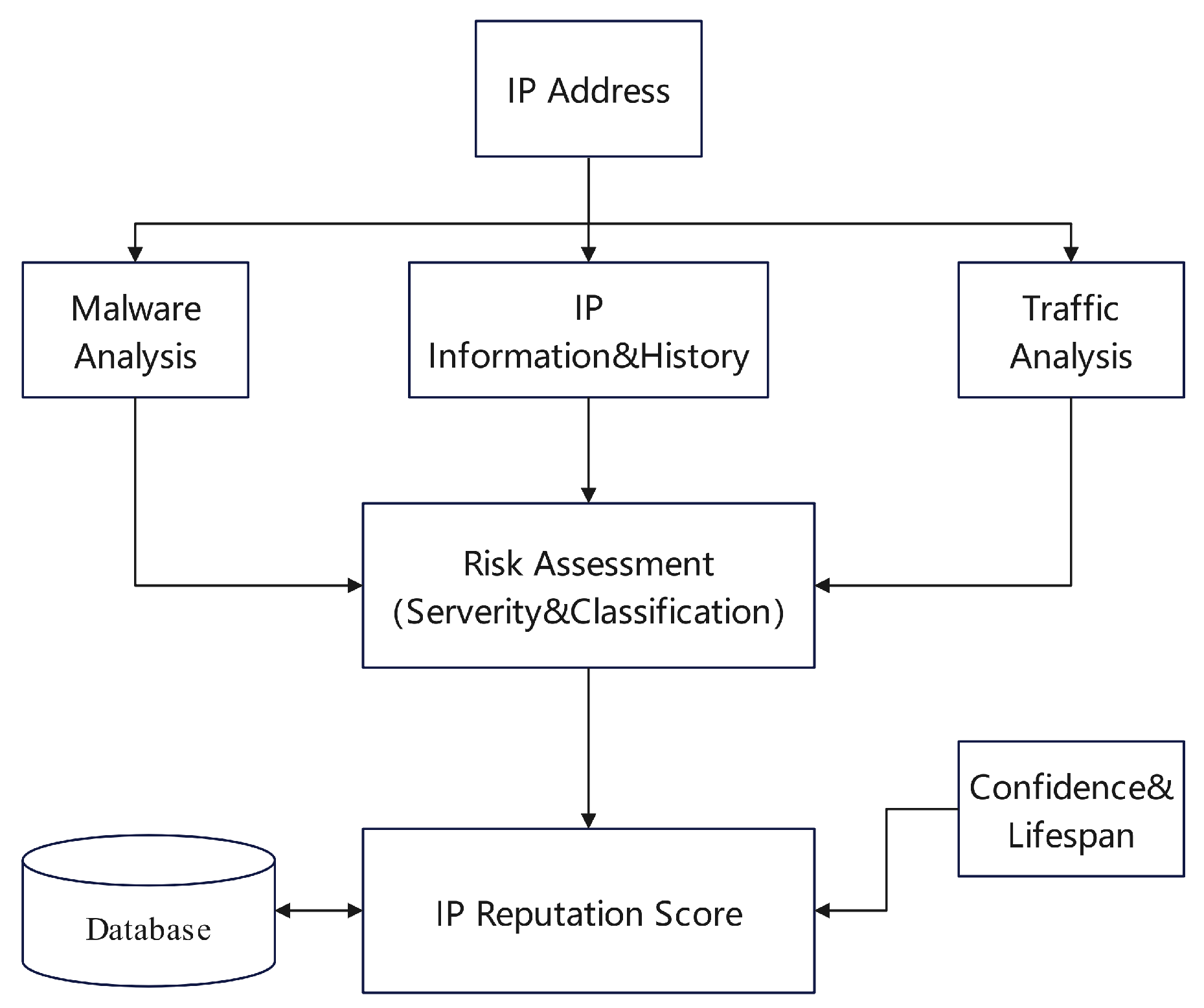

2.2.4. Dynamic Attributes-Oriented Assessment

Renjan et al. [

25] introduced the Dynamic Attribute-Based Reputation Evaluation (DABR) method. As illustrated in

Figure 8, this approach engages in a two-stage process: the generation of the reputation model and the computation of reputation scores. The initial phase compiles a database of identified malicious IP addresses and extracts various meta-features, which feed into the creation of a predictive model for classifying IP addresses as benign or malevolent. For the evaluation of newly observed IPs, the DABR framework gathers pertinent attributes, normalizes the accumulated feature vectors, and applies the Euclidean distance from a standardized point of origin to calculate the IP address’s reputation score.

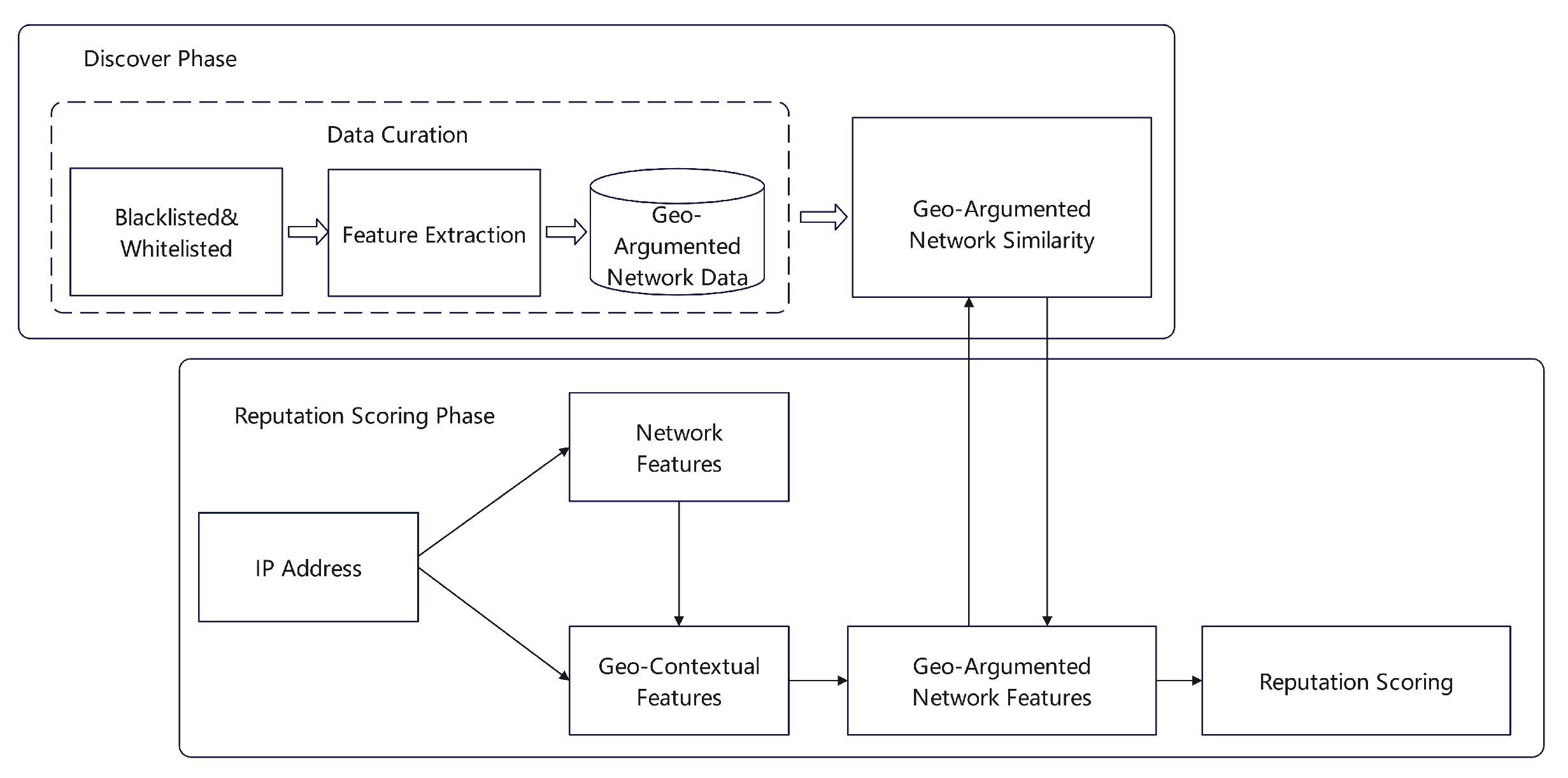

2.2.5. Geographically Enhanced Network Similarity Assessment

Sainani et al. [

26] devised an approach to evaluate the trustworthiness of IP addresses in scenarios involving encrypted communications.

Figure 9 demonstrates the model, which consolidates network metrics sourced from various databases with geographic information to create a Geographically Enhanced Network dataset (GeoNet). The model employs a customized clustering algorithm to establish a reference model; thereafter, it assesses the interconnectedness between individual IP addresses. The trustworthiness of an IP address is ultimately determined by the degree of its alignment with the reference model.

2.2.6. Image Layering Technique for Reputation Assessment

Anderson et al. [

27] explored the presence of fraudulent activities within spam emails by adopting an "image layering" technique. This method involves analyzing the visual congruities among web page snapshots to group together scam-related servers. The system extracts content from emails, detects URLs embedded within, and dynamically follows these links to identify the associated servers. It subsequently engages in proactive server probing to elucidate key operational characteristics, such as server uptime, activity periods, and geographic distribution, thereby enabling a comprehensive assessment of server reputation.

2.3. Reputation Assessment Employing Machine Learning Methods

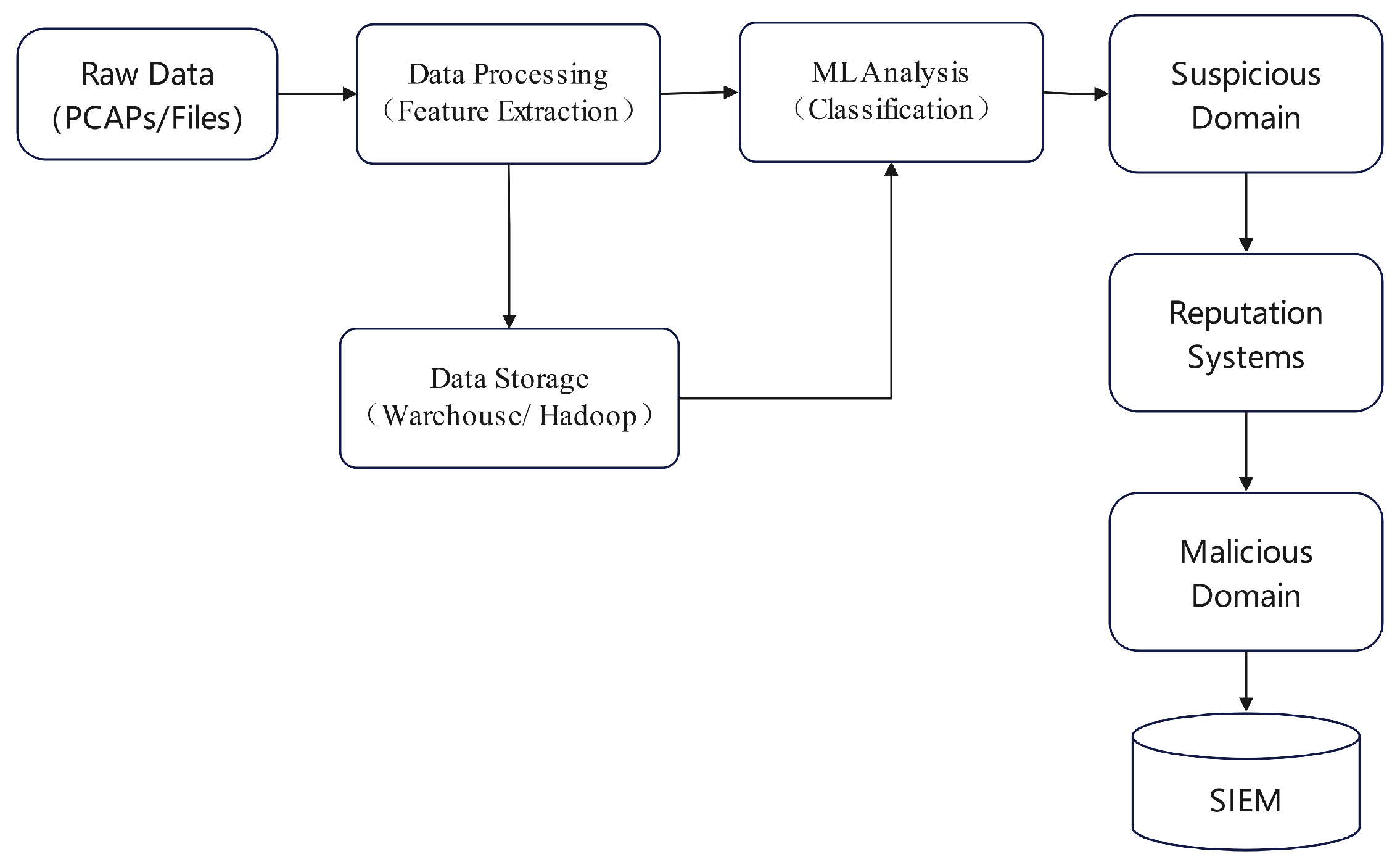

2.3.1. Feature-based DNS Reputation Assessment

Ma et al. [

28] employed a feature-based approach to differentiate between benign and malicious websites. They leveraged lexical features of URLs, such as the length of the hostname, overall URL length, and the count of period characters ".", in addition to host attributes like IP address descriptors, WHOIS information, domain registration details, and geographic location data. These attributes were consolidated into feature vectors, which facilitated automated classification and improved predictive accuracy through the deployment of Support Vector Machines (SVM) and regularized logistic regression (LR).

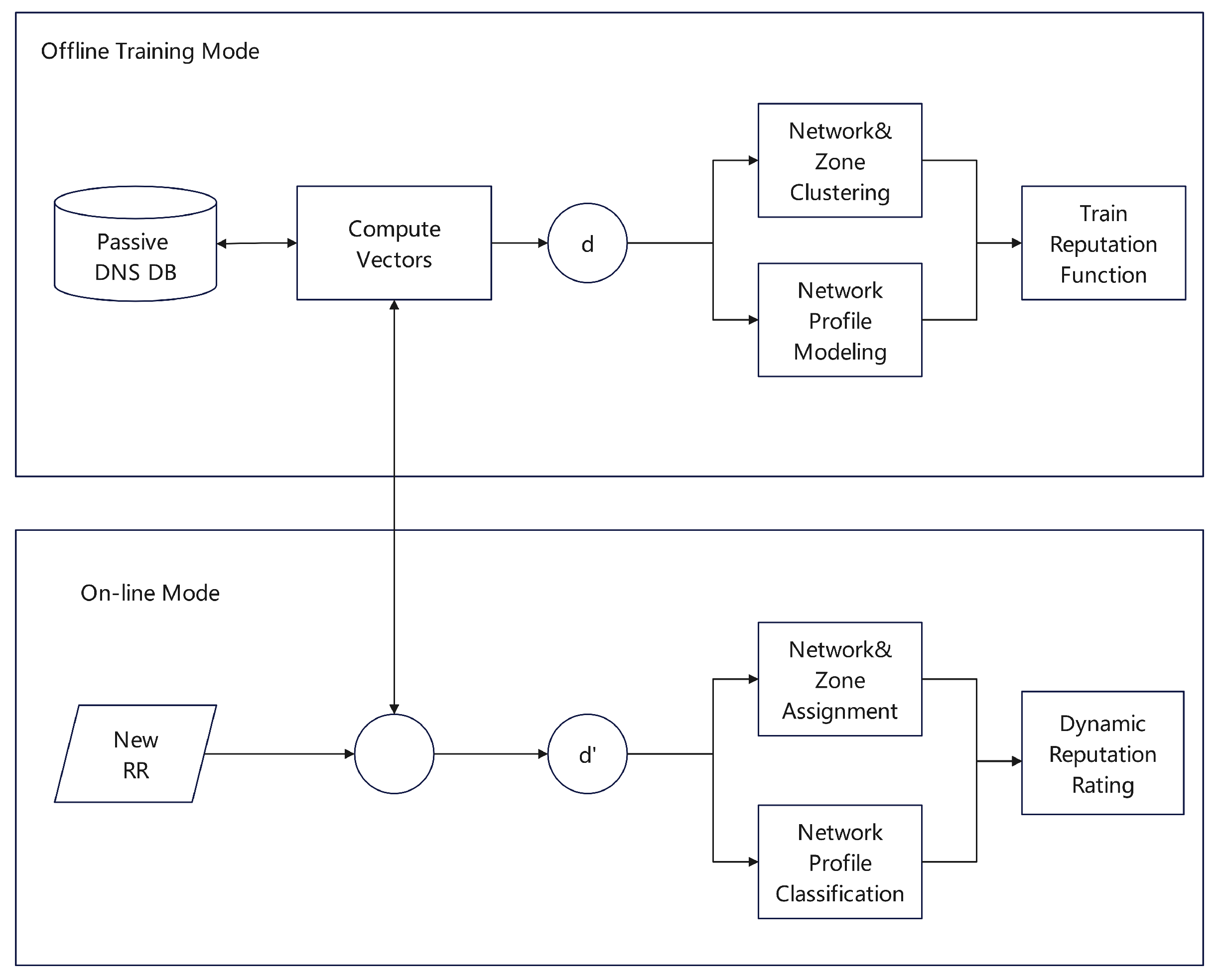

Antonakakis et al. [

29] proposed the Notos model, effectively distinguishing between legitimate and malicious domains by analyzing network-based and regional characteristics pertinent to the DNS. As illustrated in

Figure 10, Notos relies on DNS and IP traffic data collected from both passive DNS repositories and Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems to assess network behaviors, historical regional attributes, and domain activity patterns. The model’s reputation engine synthesizes these inputs with an extensive knowledge base to train a statistical reputation function that assigns credibility scores to new domains.

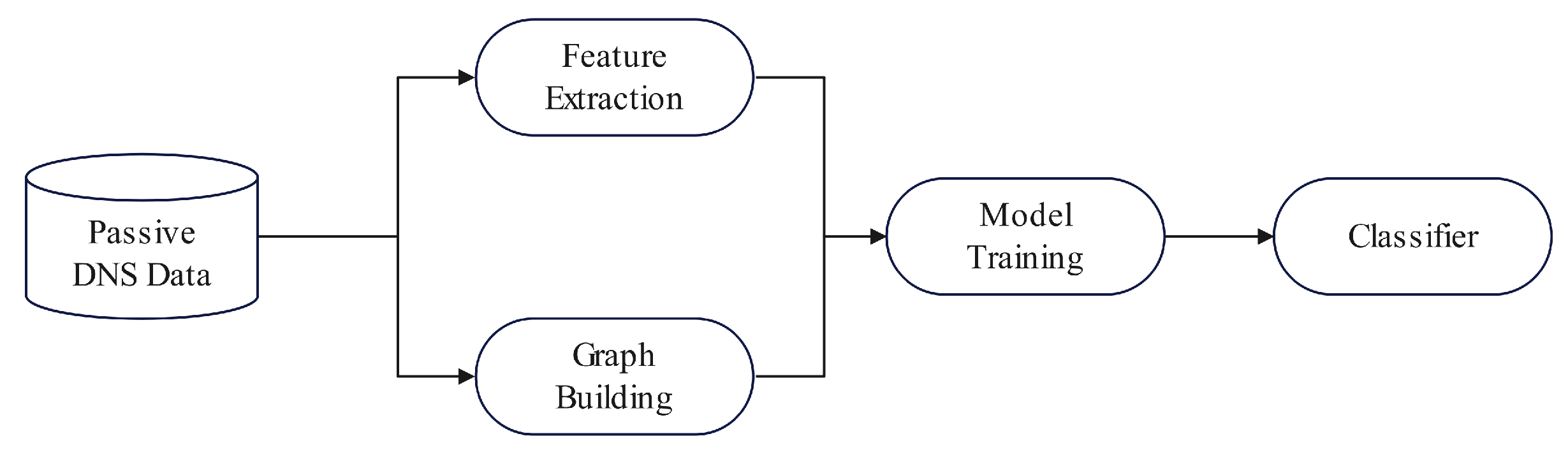

Liang et al. [

30] presented the MalPortrait system, integrates domain-specific features with relational data between domains to detect malevolent entities. As depicted in

Figure 11, the system harvests both string-based and network-based domain features, and discerns domains that resolve to identical IP addresses as interconnected nodes within a network graph. The strength of inter-domain correlations informs the graph’s topology, and graph-theoretic methods are employed to derive novel predictive features. A Random Forest algorithm powers the system’s ability to effectuate robust domain assessment and malicious domain identification.

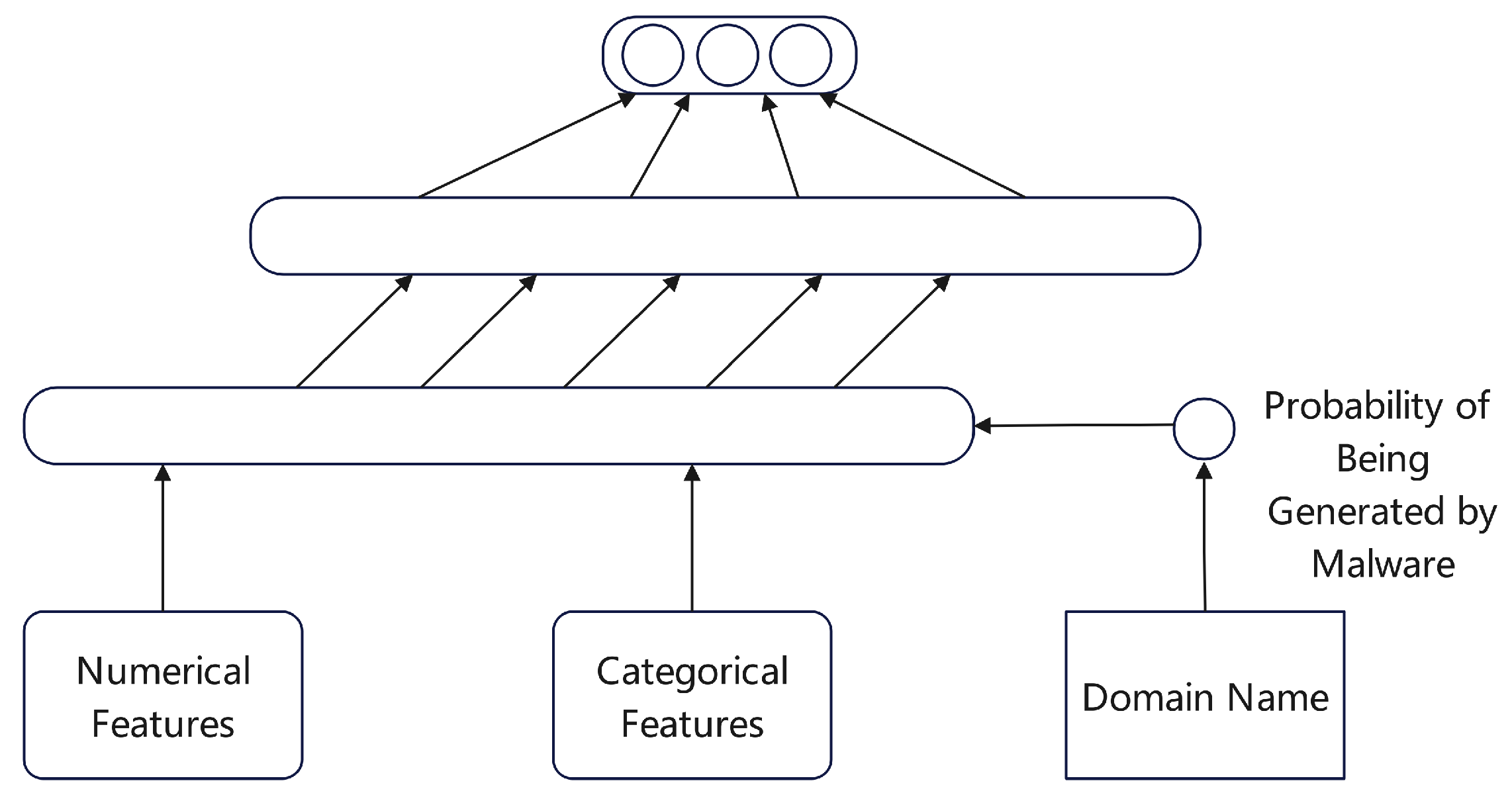

Lison [

31] harnessed the prowess of deep neural network architectures for categorizing domain names. This model begins by aggregating a plethora of features spanning numerical, categorical, and character sequence data types, partially labeled through established blacklist and whitelist repositories. A bidirectional graph model underpins the framework, intertwining domain names with IP addresses through association-based links, and allowing the reputation of each node to influence its neighbors.

Figure 12 showcases the neural processing pathway, the transformation of data into compressed embedding vectors—particularly for categorical features, the application of recursive networks to estimate malware-generation probabilities, and ultimately, the integration into dual successive dense layers that project a probabilistic domain reputation distribution.

2.3.2. Feature-based Email Reputation Assessment

Tang et al. [

32] innovated a method to evaluate the email sender’s reputation based on spectral features. The system scrutinizes the communication patterns of email senders to unveil distinctive behavioral signatures. Methodology is the gathering of key data, including the queried IP address (Q), the originating source of the query (S), and the corresponding timestamp (T). Collectively referred to as QST data, these parameters inform the construction of two feature vector sets—the width vector encapsulates the general behavioral trend associated with an IP, and the spectral vector delineates the specific sending pattern. These vectors enable the system to parse IP behaviors with elevated precision, thereby enhancing the identification of spam emails.

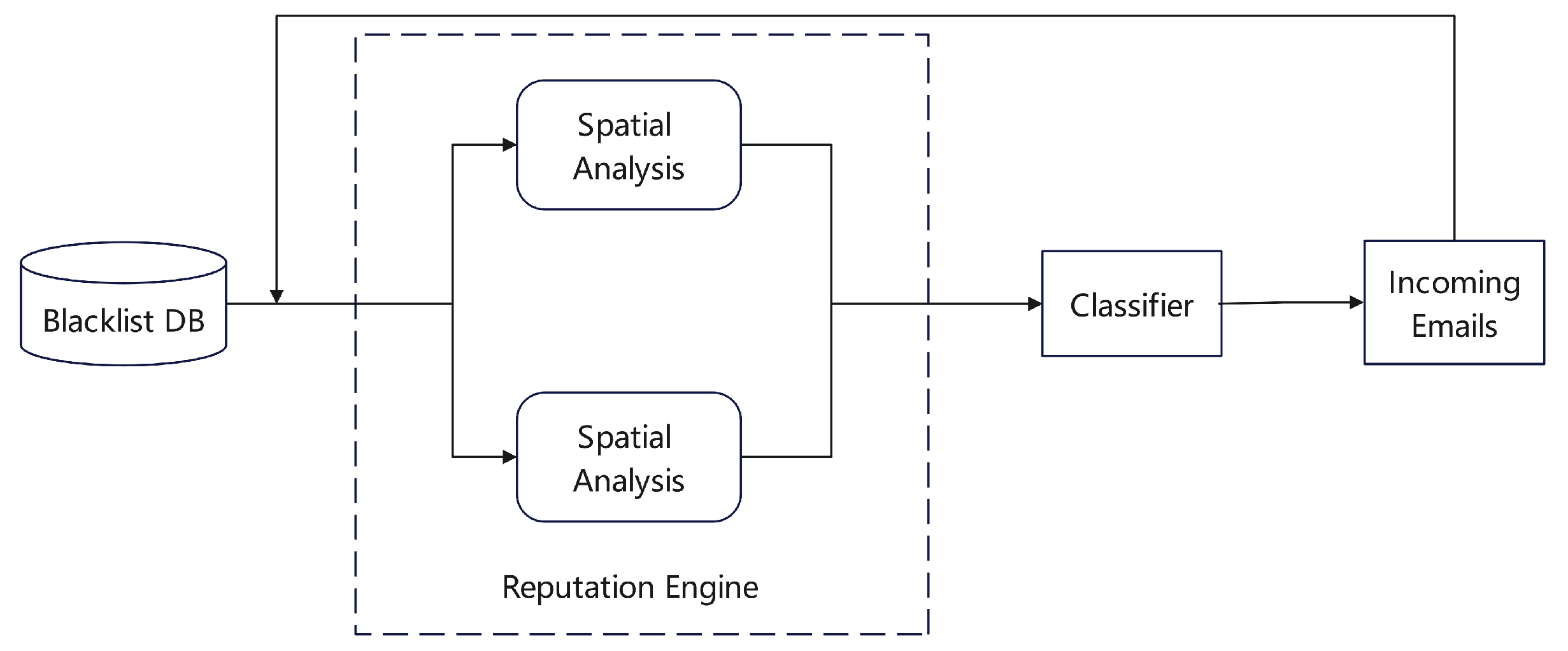

Hao et al. [

33] designed the SNARE system for automated reputation scoring of email senders, assessing them by exploring the spatiotemporal attributes of communications. The system involves an array of variables, including the sender’s automation systems, the geographic dispersion of IP addresses, the temporal patterns of emails sent, the status of open ports, the length of message content, and the density within the IP address space. Following feature extraction, these data points are fed into an automated classifier, which, coupled with preclassified data, enables the sender categorization process via supervised machine learning algorithms.

West et al. [

34] proposed a sophisticated reputation model known as PreSTA, grounded in the analysis of historical data from IP blacklists, coupled with spatial reasoning techniques. As depicted in

Figure 13, PreSTA operates on a feedback database that monitors the dynamics of blacklists and records negative feedback events. The model extracts salient attributes such as the hierarchical configuration of IP addresses, the incidence of spam-associated IPs, and the spatial clustering of these addresses. It employs two temporal functions that accord higher weight to recent activities, and a spatial function that normalizes values in accordance with the magnitude of the IP clusters. By applying these functions, PreSTA ascertains diverse reputation scores for IP addresses corresponding to different spatial contexts and then utilizes Support Vector Machines (SVMs) to determine threshold values for classifying credibility ratings.

2.3.3. Feature-based IP Address Reputation Assessment

Chiba et al. [

35] outlined a systematic approach for detecting malicious websites by investigating the temporal consistency and spatial clustering of IP addresses.The method defines an IPv4 address as a tuple (X1, X2, X3, X4), with ’N’ representing an integer from 0 to 4 and ’k’ denoting the index within the feature vector. An IP address’s feature vector is composed of three types of extractions: octal, expanded octal , and bitwise. These extracted features inform the SVM-based supervised learning for classification, where the decision function of the SVM is calibrated using a logistic sigmoid function [

36] to compute a probabilistic reputation score.

Huang et al.[

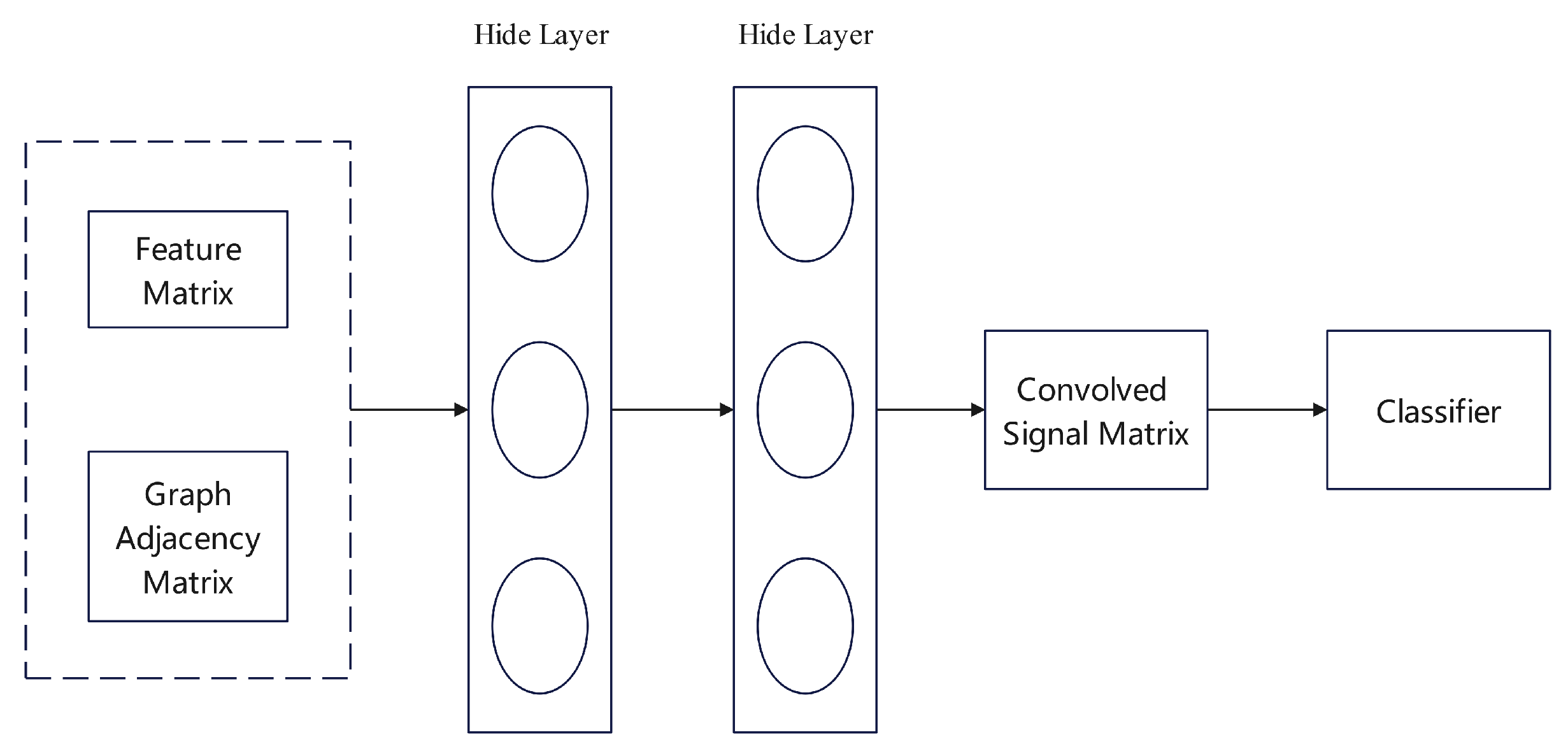

37] developed a method that harnesses Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in conjunction with cross-protocol analysis for the robust identification of malicious IP addresses.

Figure 14 demonstrates how the model integrates features from network traffic, emails, and DNS protocols to form an extensive feature matrix within a multi-dimensional feature space. An IP association graph is constructed, representing IP addresses as nodes and their connections as edges, using an adjacency matrix for representation.

Initially, the algorithm employs a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to automatically deduce an embedding layer that captures the topological characteristics of the graph. Successive hidden layers then aggregate these features from immediate neighbors to refine each node’s feature representation, culminating in the formation of a detailed feature matrix. The model subsequently employs a softmax function and a Random Forest classifier in sequence to carry out node classification, translating the results into probabilities indicative of the likelihood that the IP addresses may be malicious.

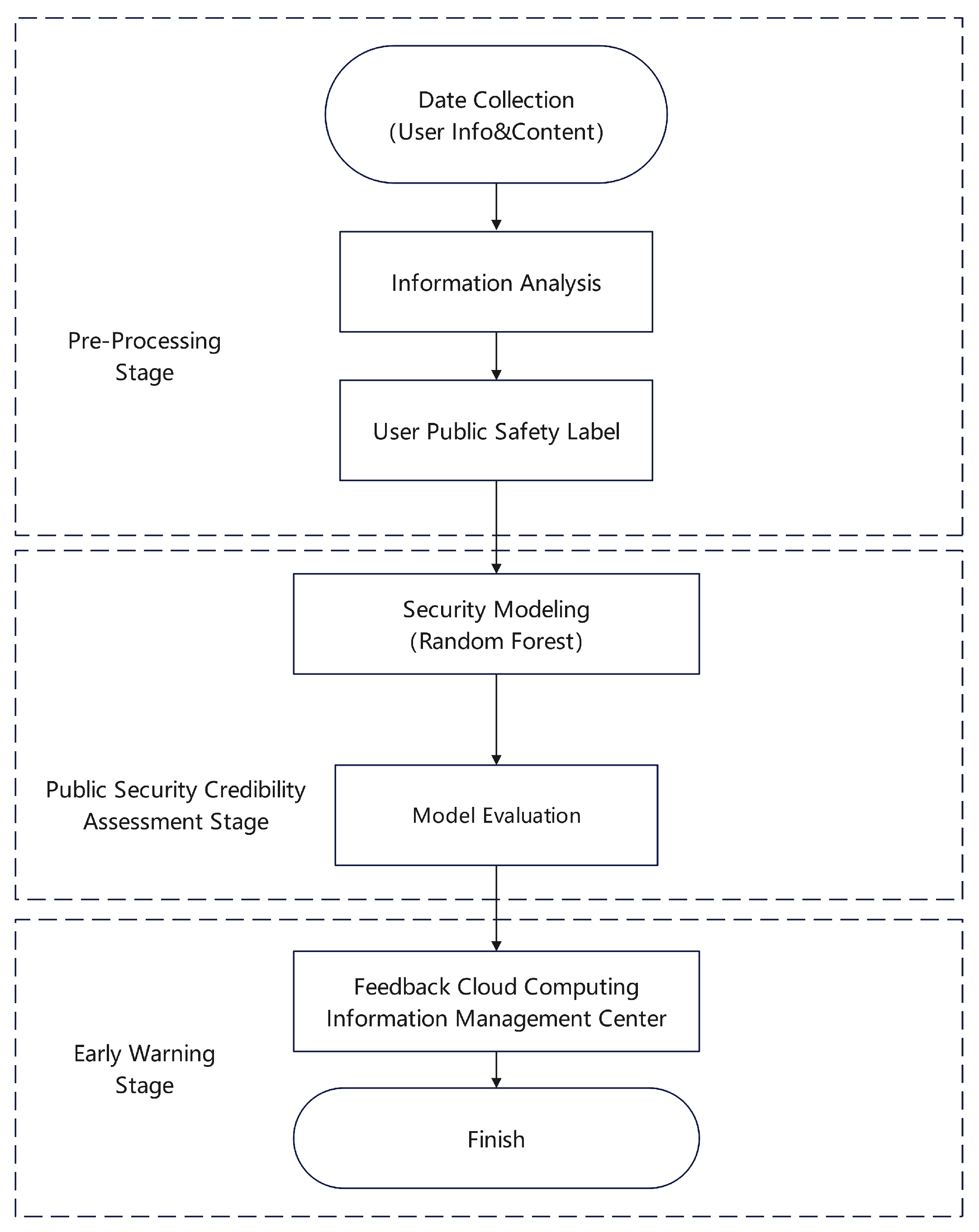

2.3.4. Cloud Computing Reputation Assessment Based on a Scorecard—Random Forest Model

Zhou et al.[

38] introduced the PST-SRF model, which innovatively combines a scorecard methodology with the Random Forest algorithm to evaluate the reputation of cloud computing services. As illustrated in

Figure 15, this model begins by collecting hyperlink navigation and content information through tools provided by cloud service providers, such as web crawlers, log collectors, and text information parsing systems. The model then extracts salient features and conducts a categorical analysis using a convolutional neural network (CNN). In the subsequent phase, the scorecard approach is utilized to identify key indicators that are closely linked with the cloud service’s public safety reputation. Finally, the Random Forest algorithm is applied to assess the comprehensive public safety reputation of cloud service users.

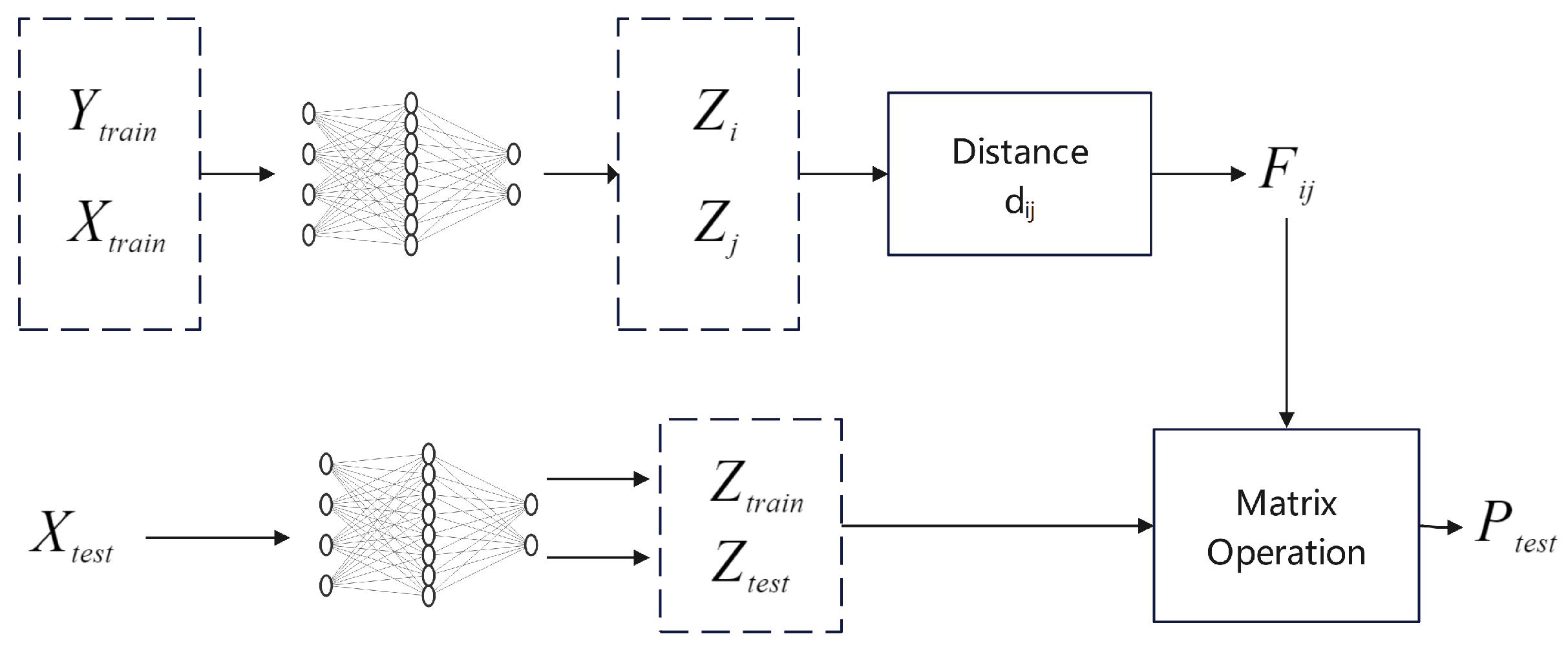

2.3.5. Reputation Assessment Based on Similarity Classification

Sun et al.[

39] developed the Siamese Network Classification Framework (SNCF) to facilitate scalable and effective risk analysis techniques based on similarity measurements. As depicted in

Figure 16, the SNCF model encompasses three main stages: data preprocessing, model training, and risk prediction. During preprocessing, pairs of data samples

are projected onto a standardized space that enables the calculation of their similarity

using Euclidean distance. The training phase involves the Siamese network architecture, which is conditioned using the target risk label

and the calculated similarities as a reference. Finally, risk prediction is carried out through matrix operations to predict risk labels for new test data, thus achieving comprehensive risk assessment.

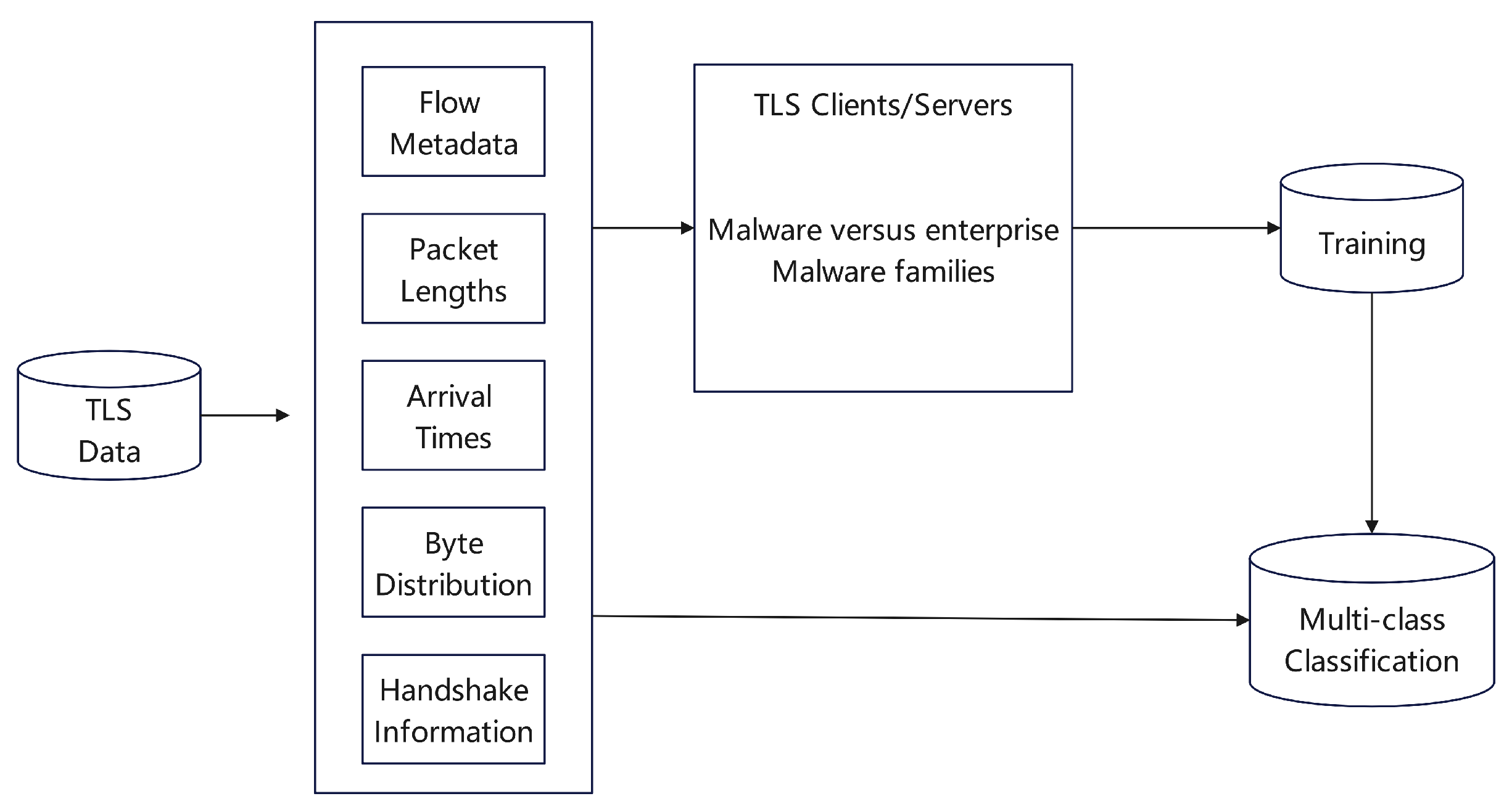

2.3.6. Reputation Assessment Based on TLS Features

Anderson et al.[

40] explored the domain of encrypted traffic, particularly focusing on features extracted from TLS for the detection of malware traffic.

Figure 17 presents the various features examined, which include network quintuples, sequences of packet lengths, timing intervals between packets, distribution patterns of bytes, and metadata from unencrypted TLS handshakes. The investigation revealed distinctive patterns in malware traffic, such as anomalies in encryption and signature algorithms, public key lengths, client parameters, and destination addresses. A logistic regression classifier was employed to successfully identify and categorize malware.

2.3.7. Reputation Assessment Based on Clustering Algorithms

Morales et al.[

41] clustered algorithms were synergized with a database of known malicious domain names to effectively identify malignant DNS queries and responses. As outlined in

Figure 18, this method involves the initial extraction of crucial attributes, such as domain names, TTL values, and response patterns, from passive DNS traffic. The approach incorporates a preprocessing stage where domain reputations are vetted using trusted sources. Domains assessed as high-risk are subsequently stored in an "anchor" file. This strategy implements the use of data batching and a consistent sliding window technique to continuously assess the data. Within each window, distinct clustering algorithms—k-Means, AP, and MS are applied to analyze and categorize domains that could potentially pose security threats.

2.3.8. Reputation Assessment Based on Malware Analysis

Usman et al.[

42] introduced a multifaceted approach that intertwines dynamic malware analysis, network threat intelligence, and machine learning techniques to evaluate the reputation of IP addresses. As illustrated in

Figure 19, the proposed methodology begins with the dynamic analysis of malware samples associated with particular IP addresses. These samples are then classified using a range of machine learning algorithms. A comprehensive analysis of the malware includes several factors such as binary signatures, periods of activity, and the frequency of connection attempts. For a more detailed inquiry, two distinct datasets are generated: one reflecting the network signatures of malicious software, and the other containing additional information regarding file system and registry operations. Employing decision tree analysis, the approach compares behavioral patterns and deviations across these datasets, ultimately deducing the malignancy level of the respective IP addresses.

3. Comparative Summary of Existing Methods

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the reputation evaluation systems discussed in Chapter 2. The assessment takes into account the objects of evaluation, elements of evaluation, application settings, real-time capability, and accuracy.

The tabular data presented above provides a comprehensive analysis of various systems. Evidently, the utilization of statistical algorithms for evaluating network reputation has proven to be both efficient and concise. However, this method exhibits certain limitations, namely the stringent requirement of high-quality data and a protracted evaluation timeline. Consequently, this approach fails to deliver early warnings against unknown malicious activities.

Comparison measures, despite leveraging an array of features, present their own challenges in the context of data normalization and feature extraction. Such challenges can consequently influence calculation efficiency. Moreover, the choice and dynamic update of anchor points require more consideration and improvement in terms of accuracy.

Machine learning techniques have shown potential in evaluating diverse objects and predicting unknown malicious behaviors in network reputation. These techniques also exhibit impressive accuracy, though they require greater computational resources and deployment complexity.

4. Development Trends

Reputation systems play a pivotal role in maintaining the integrity of the internet. They not only encourage ethical conduct but also enhance the quality of network services. As preventive tools, these systems curb detrimental activities within the network, thereby securing websites and their users. The emerging trends in the development of reputation systems can be classified into several key sectors:

4.1. Data Diversification

Traditional reputation evaluation overly relies on a limited set of data sources, such as user behavioral logs, historic transaction data, and IP address blacklists. With the rapid surge in data and continued advancement in big data analysis technologies, future reputation evaluation systems are anticipated to incorporate a wider range of aspects and dimensions. These could include trustworthiness analysis of data sources, network protocol characteristic analysis, traffic analysis, user activity levels, and time-series data to achieve a more versatile and general evaluation system. Concurrently, effectively integrating and merging data from multiple channels, formats, and qualities to maintain data consistency, completeness, and reliability, poses a much-needed area of exploration for future research.

4.2. Real-time Assessment and Dynamic Monitoring

Thanks to the substantial improvement of server computing capabilities and the continual evolution of distributed computing technologies, reputation evaluation systems are increasingly adopting a continuous monitoring and real-time evaluation approach. As these systems lessen their dependency on historical data, they are better positioned to swiftly identify and react to potential security threats and undesired behaviors. Such systems can detect internal anomalies and risk factors in a timely manner, thereby enabling rapid defensive action and reinforcing the security line. However, evaluation systems often contain redundant information when processing multi-dimensional data, and the efficiency of feature identification and extraction remains a topic for improvement. Further, as data volume grows, computational complexity may increase exponentially, severely constraining the timeliness of the evaluation system.

4.3. Extensive Reputation Evaluation

The widespread implementation of IPv6 technology in concert with the Internet of Things (IoT) has magnified the focus on network nodes and user data security considerations. This prevailing trend indicates a surge in large-scale application and demand for reputation evaluation systems. In the expansive scheme of things, the evolution of these systems would aid in constructing a more holistic and precise paradigm for assessing network security. The challenge that lies within the sphere of reputation evaluation includes designing efficient reputation propagation and evaluation mechanisms suited to diverse platforms and varied network environments, addressing the issues of cross-platform reputation consistency, and devising effective safeguards for user privacy, thereby eliminating the risk of data-leakage and misuse during the evaluation process.

4.4. Incorporation of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

The lightning-paced progression of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology has engendered a paradigm where establishing reputation feature extraction and classification models based on network security increasingly leans on data analysis and intelligent algorithms. The application of AI’s capacity for autonomous learning and real-time updating promises to yield more precise and effective evaluation results, thus augmenting the potency of network security protection. However, in actual network contexts, given the data scarcity and category imbalance issues, addressing data imbalance, sample paucity, and label inaccuracies becomes crucial for refining the accuracy of the evaluation system. Accordingly, Machine Learning and Deep Learning models, often perceived as enigmatic ’black box’ constructs, necessitate a deeper dive to untangle the logic underpinning model decisions. Enhancing model interpretability, and thereby strengthening the credibility of reputation evaluation outcomes, holds considerable relevance in encouraging the implementation and advancement of Machine Learning and AI in this domain.

5. Conclusion

Network reputation evaluation, given its considerable potential and practicality, emerges as a critical research direction within the field of network security. This paper provides a comprehensive review of network reputation evaluation methodologies, appraising their merits and limitations, and deliberates on prospective trends and challenges. Network reputation evaluation systems assume a vital role in improving network security defense capacities, fostering network service quality, and enhancing user articleexperience. Due to the constant modifications occurring in network environments and application scenarios, constant optimization and advancement of network reputation evaluation systems are crucial to address new security challenges and requirements.

References

- Resnick, P.; Kuwabara, K.; Zeckhauser, R.; Friedman, E. Reputation Systems. COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM 2000, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristofaro, E.; Gasti, P.; Tsudik, G. Fast and Private Computation of Cardinality of Set Intersection and Union. In Cryptology and Network Security; Hutchison, D., Kanade, T., Kittler, J., Kleinberg, J.M., Mattern, F., Mitchell, J.C., Naor, M., Nierstrasz, O., Pandu Rangan, C., Steffen, B., et al., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.D.; Joyce, M.V. Trusted System Concepts. Computers & Security 1995, 14, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jøsang, A.; Ismail, R.; Boyd, C. A Survey of Trust and Reputation Systems for Online Service Provision. Decision Support Systems 2007, 43, 618–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.Inc. Senderbase reputation score overview. Website, 2020. http://www.ironport.com/pdf/ironport-senderbase-reputationscore-overview.pdf.

- Talos, C. Cisco Talos Intelligence Group-Comprehensive Threat Intelligence. Website, 2023. https://support.talosintelligence.com/.

- Validity. Sender Score Email Reputation Management. Website, 2022. https://senderscore.org/assess/get-your-score.

- Wikipedia. TrustedSource. Website, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TrustedSourc.

- Microsoft. WhatIsSNDS. Website, 2013. https://sendersupport.olc.protection.outlook.com/snds/FAQ.aspxWhatIsSNDS.

- D, P.; W, J. Managing Distributed Trust Relationships for Multi-Modal Authentication. J. Inf. Secur. Appl 2018, 40, 258–270. [Google Scholar]

- Tencent, C. Tencent’s Threat Intelligence Cloud Search Service. Website, 2022. https://cloud.tencent.com/document/product/1013/31158.

- LI, B.; WU, L.; ZHOU, Z.; LI, H. Design and Implementation of Trust—based Identity Management Model fbr Cloud C0mputing. Computer Science 2014, 41, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Lan, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Chen, D. Enhancing Cloud-Based IoT Security Through Trustworthy Cloud Service: An Integration of Security and Reputation Approach. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 9368–9383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YANG, S.; DENG, Q. P2P Reputation Estimation Based on Statistical Inference. Microelectronics and Computer 2008, 25, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, y.; Hu, b.; Zheng, x.; Zhang, q. A network security protection method and system and process based on IP address security credibility. CN20161082 0694.2, 2020.

- Xie, M.; Wang, H. A Collaboration-based Autonomous Reputation System for Email Services. In Proceedings of the 2010 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM, San Diego, CA, USA; 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tian, Z.; Cui, X.; Yin, L.; Wang, X. Trust Architecture and Reputation Evaluation for Internet of Things. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2019, 10, 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.q.; Lin, C.; Ni, Y. Evaluation of User Behavior Trust in Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Computer Application and System Modeling (ICCASM 2010), Taiyuan, China; 2010; pp. V7–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Yun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Xiao, J. Discovering Malicious Domains through Alias-Canonical Graph. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ICESS, Sydney, Australia; 2017; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifnya, R.; Abadi, M. A Novel Reputation System to Detect DGA-based Botnets. In Proceedings of the ICCKE 2013, Mashhad, Iran; 2013; pp. 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vassileva, J. Trust and Reputation Model in Peer-to-Peer Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Third International Conference on Peer-to-Peer Computing (P2P2003), Linkoping, Sweden; 2003; pp. 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Y.; Hori, Y.; Sakurai, K. Proactive Blacklisting for Malicious Web Sites by Reputation Evaluation Based on Domain and IP Address Registration. In Proceedings of the 2011IEEE 10th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications; 2011; pp. 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, H.; Akella, A.; Mori, T. On the Effectiveness of IP Reputation for Spam Filtering. In Proceedings of the 2010 Second International Conference on COMmunication Systems and NETworks (COMSNETS 2010), Bangalore, India; 2010; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Cho, J.; Lee, C. A Reliability Comparison Method for OSINT Validity Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 14, 5428–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjan, A.; Joshi, K.P.; Narayanan, S.N.; Joshi, A. DAbR: Dynamic Attribute-based Reputation Scoring for Malicious IP Address Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Miami, FL; 2018; pp. 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainani, H.; Namayanja, J.M.; Sharma, G.; Misal, V.; Janeja, V.P. IP Reputation Scoring with Geo-Contextual Feature Augmentation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 2020, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.S.; Fleizach, C.; Savage, S.; Voelker, G.M. Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Security Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, August 6-10, 2007.

- Ma, J.; Saul, L.K.; Savage, S.; Voelker, G.M. Beyond Blacklists: Learning to Detect Malicious Web Sites from Suspicious URLs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Paris France, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, M.; Perdisci, R.; Dagon, D.; Lee, W.; Feamster, N. Building a dynamic reputation system for {DNS}. In Proceedings of the 19th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 10); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Zang, T.; Zeng, Y. MalPortrait: Sketch Malicious Domain Portraits Based on Passive DNS Data. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lison, P.; Mavroeidis, V. Neural Reputation Models Learned from Passive DNS Data. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2017; pp. 3662–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Krasser, S.; Judge, P.; Zhang, Y.Q. Fast and Effective Spam Sender Detection with Granular SVM on Highly Imbalanced Mail Server Behavior Data. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing, Atlanta, GA; 2006; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Syed, N.A.; Feamster, N.; Gray, A.G.; Krasser, S. Detecting Spammers with SNARE: Spatio-temporal Network-level Automatic Reputation Engine. In Proceedings of the USENIX security symposium, Vol. 9. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- West, A.G.; Aviv, A.J.; Chang, J.; Lee, I. Spam Mitigation Using Spatio-Temporal Reputations from Blacklist History. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, Austin Texas USA, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Chiba, D.; Tobe, K.; Mori, T.; Goto, S. Detecting Malicious Websites by Learning IP Address Features. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/IPSJ 12th International Symposium on Applications and the Internet, Izmir, Turkey; 2012; pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J, P. Probabilistic Outputs for Support Vector Machines and Comparisons to Regularized Likelihood Methods. Advances in large margin classifiers 1999, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Negrete, J.; Wagener, J.; Fralick, C.; Rodriguez, A.; Peterson, E.; Wosotowsky, A. Graph Neural Networks and Cross-Protocol Analysis for Detecting Malicious IP Addresses. Complex & Intelligent Systems. [CrossRef]

- ZHOU, S.; JIN, C.; WU, L.; HONG, Z. Research on cloud computing users’ public safety trust model based on scorecard-random forest. Journal on Communications 2018, 39, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lv, Q.; Hu, B. Risk Prediction for Imbalanced Data in Cyber Security : A Siamese Network-based Deep Learning Classification Framework. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Budapest, Hungary; 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.; Paul, S.; McGrew, D. Deciphering Malware’s Use of TLS (without Decryption). Journal of Computer Virology and Hacking Techniques 2018, 14, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.; Beck, S.; Zook, J.; Buczak, A.; Chavis, J.; Robinson, W.H.; Morales, J.A.; Mishra, S. Using Semi-Supervised Machine Learning to Address the Big Data Problem in DNS Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 7th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, N.; Usman, S.; Khan, F.; Jan, M.A.; Sajid, A.; Alazab, M.; Watters, P. Intelligent Dynamic Malware Detection Using Machine Learning in IP Reputation for Forensics Data Analytics. Future Generation Computer Systems 2021, 118, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Architecture of PeerTrust System

Figure 1.

Architecture of PeerTrust System

Figure 2.

Architecture of CARE System

Figure 2.

Architecture of CARE System

Figure 4.

Workflow for the Identification Process of Malicious Domains

Figure 4.

Workflow for the Identification Process of Malicious Domains

Figure 5.

Schematic of the DNS-based Reputation Estimation System

Figure 5.

Schematic of the DNS-based Reputation Estimation System

Figure 6.

Complex Dynamics of the Trust and Reputation Mechanism in a Peer-to-Peer Network

Figure 6.

Complex Dynamics of the Trust and Reputation Mechanism in a Peer-to-Peer Network

Figure 7.

Triple-Layered Structure of the SIEM-Based Model for Reputation Assessment

Figure 7.

Triple-Layered Structure of the SIEM-Based Model for Reputation Assessment

Figure 8.

Operational Framework of the DABR System

Figure 8.

Operational Framework of the DABR System

Figure 9.

GeoNet Model Illustrating the Integration of GeoNet for IP Credibility Assessment

Figure 9.

GeoNet Model Illustrating the Integration of GeoNet for IP Credibility Assessment

Figure 10.

The Notos Model System Architecture

Figure 10.

The Notos Model System Architecture

Figure 11.

MalPortrait System Overview

Figure 11.

MalPortrait System Overview

Figure 12.

Deep Neural Network Architecture for Domain Reputation Prediction

Figure 12.

Deep Neural Network Architecture for Domain Reputation Prediction

Figure 13.

The PreSTA framework for spam detection

Figure 13.

The PreSTA framework for spam detection

Figure 14.

Application of the GCN Model to Node Classification for IP Reputation Analysis

Figure 14.

Application of the GCN Model to Node Classification for IP Reputation Analysis

Figure 15.

Workflow of the PST-SRF Model for Assessing Cloud Computing User Reputation

Figure 15.

Workflow of the PST-SRF Model for Assessing Cloud Computing User Reputation

Figure 16.

The SNCF for Scoreimilarity-Based Risk Assessment

Figure 16.

The SNCF for Scoreimilarity-Based Risk Assessment

Figure 17.

Analyzing Malware Activity via TLS Characteristics

Figure 17.

Analyzing Malware Activity via TLS Characteristics

Figure 18.

Schematic of Big Data Platform for Malicious Domain Detection

Figure 18.

Schematic of Big Data Platform for Malicious Domain Detection

Figure 19.

Representation of the Dynamic IP Reputation System

Figure 19.

Representation of the Dynamic IP Reputation System

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Existing Reputation System

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Existing Reputation System

| Name |

Evaluation Object |

Evaluation Elements |

Adopted Technology |

Application Field |

Realtime |

Accuracy |

| PeerTrust |

Node |

Transaction Feedback |

Statistical Analysis |

Commerce |

no |

99.2% |

| CARE |

Email Domain |

Historical Behavior |

Statistical Analysis |

Email Communication |

no |

99.6% |

| IoTrust |

Node |

Historical Behavior |

Statistical Analysis |

IoT |

no |

Varies |

| STRAF |

Cloud Services |

Security Features

Feedback Rating |

Statistical Analysis |

IoT |

no |

|

| CNAME |

Domain |

DNS CNAME RR |

Statistical Analysis |

Detection of Malicious Domain |

yes |

97.3% |

| GSVMBA |

Email Sender |

Sending Methods |

Similarity Measures |

Email Communication |

no |

99.8% |

| OSINT CTI |

Network Data |

Data Features |

Similarity Measures |

Security Monitoring |

yes |

99% |

| DABR |

IP |

Dynamic Attributes |

Similarity Measures |

Traffic Filtering |

yes |

77.6% |

| GeoNetRS |

IP |

Network Characteristics

Geographhical Features |

Similarity Measures |

Encrypted Sessions |

yes |

73.3% |

| Notos |

Domain |

Passive DNS |

Machine Learning |

Website Security |

yes |

96.8% |

| PSTSRF |

Cloud User |

Link Information

Content Information |

Machine Learning |

Cloud Security |

yes |

96.5% |

| SNCF |

Network Data |

Content Information |

Machine Learning |

Prediction of Malicious Risks |

yes |

92.2% |

| SNARE |

Email Sender |

Network Characteristics

Spatiotemporal |

Machine Learning |

Email Communication |

no |

98.7% |

| MalPortrait |

Domain |

Passive DNS |

Machine Learning |

Detection of Malicious Domain |

yes |

96.8% |

| PreSTA |

Email Sender |

Negative Feedback

Spatial Grouping |

Machine Learning |

Email Communication |

no |

93% |

| GNN-GCN |

IP |

Protocol Characteristics |

Machine Learning |

Detection of Malicious IP |

yes |

85.3% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).