1. Introduction

Partial differential equations (PDEs) constitute one of the most fundamental mathematical frameworks for describing natural phenomena across diverse scientific and engineering disciplines. From the fluid dynamics governing atmospheric circulation patterns [

1,

2] to the quantum mechanical wave functions describing atomic behavior [

3,

4], PDEs provide the mathematical language through which we model, understand, and predict complex systems. The ubiquity of PDEs in modern science stems from their ability to capture the spatial and temporal evolution of physical quantities, making them indispensable tools in physics, engineering, biology, finance, and numerous other fields.

The pervasive role of PDEs in scientific modeling cannot be overstated. In fluid dynamics, the Navier-Stokes equations govern the motion of viscous fluids [

5,

6], enabling the design of aircraft, the prediction of weather patterns, and the understanding of oceanic currents. Electromagnetic phenomena are elegantly described by Maxwell’s equations [

7,

8], which form the theoretical foundation for technologies ranging from wireless communications to magnetic resonance imaging. In biology, reaction-diffusion equations model pattern formation in developmental biology [

9], tumor growth dynamics, and the spread of infectious diseases. Financial mathematics employs the Black-Scholes equation and its generalizations to price derivatives and manage risk in complex financial instruments [

10]. Climate modeling relies on coupled systems of PDEs to simulate atmospheric and oceanic dynamics, providing crucial insights into global warming and extreme weather events [

1,

2].

The computational solution of these equations has become increasingly critical as scientific and engineering challenges grow in complexity and scale [

11,

12,

13]. Modern applications often involve multi-physics phenomena, extreme parameter regimes, and high-dimensional parameter spaces that push traditional numerical methods to their limits [

14,

15,

16]. This has sparked intense interest in developing new computational approaches, including machine learning-based methods that promise to overcome some of the fundamental limitations of classical PDE solving techniques.

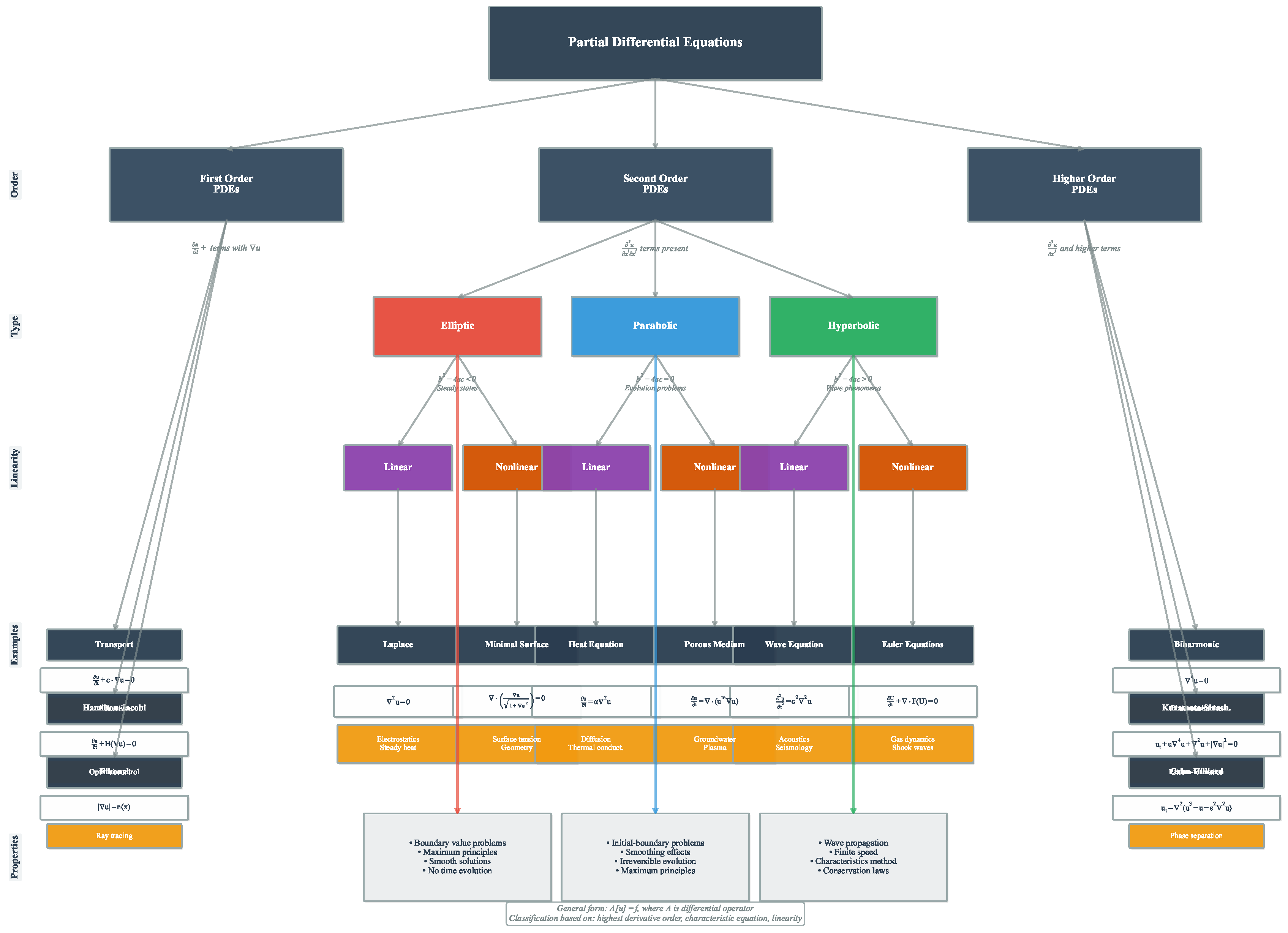

The classification of PDEs provides essential insight into their mathematical structure and computational requirements. The fundamental categorization distinguishes between elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic equations based on the nature of their characteristic surfaces and the physical phenomena they describe [

17,

18].

Elliptic equations, exemplified by Laplace’s equation

and Poisson’s equation

, typically arise in steady-state problems where the solution represents an equilibrium configuration [

19,

20]. These equations exhibit no preferred direction of information propagation, and boundary conditions influence the solution throughout the entire domain. The canonical example is the electrostatic potential problem, where the potential at any point depends on the charge distribution throughout the entire domain and the boundary conditions [

19,

20]. Elliptic problems are characterized by smooth solutions in the interior of the domain, provided the boundary data and source terms are sufficiently regular [

19,

20].

Parabolic equations, with the heat equation

serving as the prototypical example, describe diffusive processes evolving in time [

21,

22]. These equations exhibit a preferred temporal direction, with information propagating from initial conditions forward in time. The smoothing property of parabolic equations means that even discontinuous initial data typically evolve into smooth solutions for positive times [

21,

22]. Applications include heat conduction, chemical diffusion, and option pricing in mathematical finance. The computational challenge lies in maintaining stability and accuracy over long time intervals while respecting the physical constraint that information cannot propagate faster than the diffusion process allows [

23,

24,

25].

Hyperbolic equations, including the wave equation

and systems of conservation laws, govern wave propagation and transport phenomena [

26,

27]. These equations preserve the regularity of initial data, meaning that discontinuities or sharp gradients present initially will persist and propagate along characteristic curves [

26,

27]. The finite speed of information propagation in hyperbolic systems reflects fundamental physical principles such as the speed of light in electromagnetic waves or the speed of sound in acoustic phenomena [

28,

29]. Computational methods must carefully respect these characteristic directions to avoid nonphysical oscillations and maintain solution accuracy.

The distinction between linear and nonlinear PDEs profoundly impacts both their mathematical analysis and computational treatment [

30,

31]. Linear PDEs satisfy the superposition principle, allowing solutions to be constructed from linear combinations of simpler solutions [

32,

33]. This property enables powerful analytical techniques such as separation of variables, Green’s functions, and transform methods. Computationally, linear systems typically lead to sparse linear algebraic systems that can be solved efficiently using iterative methods [

34].

Nonlinear PDEs, in contrast, exhibit far richer and more complex behavior. Solutions may develop singularities in finite time, multiple solutions may exist for the same boundary conditions, and small changes in parameters can lead to dramatically different solution behavior [

30,

31]. The Navier-Stokes equations exemplify these challenges, with phenomena such as turbulence representing complex nonlinear dynamics that remain elusive. Computationally, nonlinear PDEs require iterative solution procedures such as Newton’s method, often with sophisticated continuation and adaptive strategies to handle solution branches and bifurcations [

30].

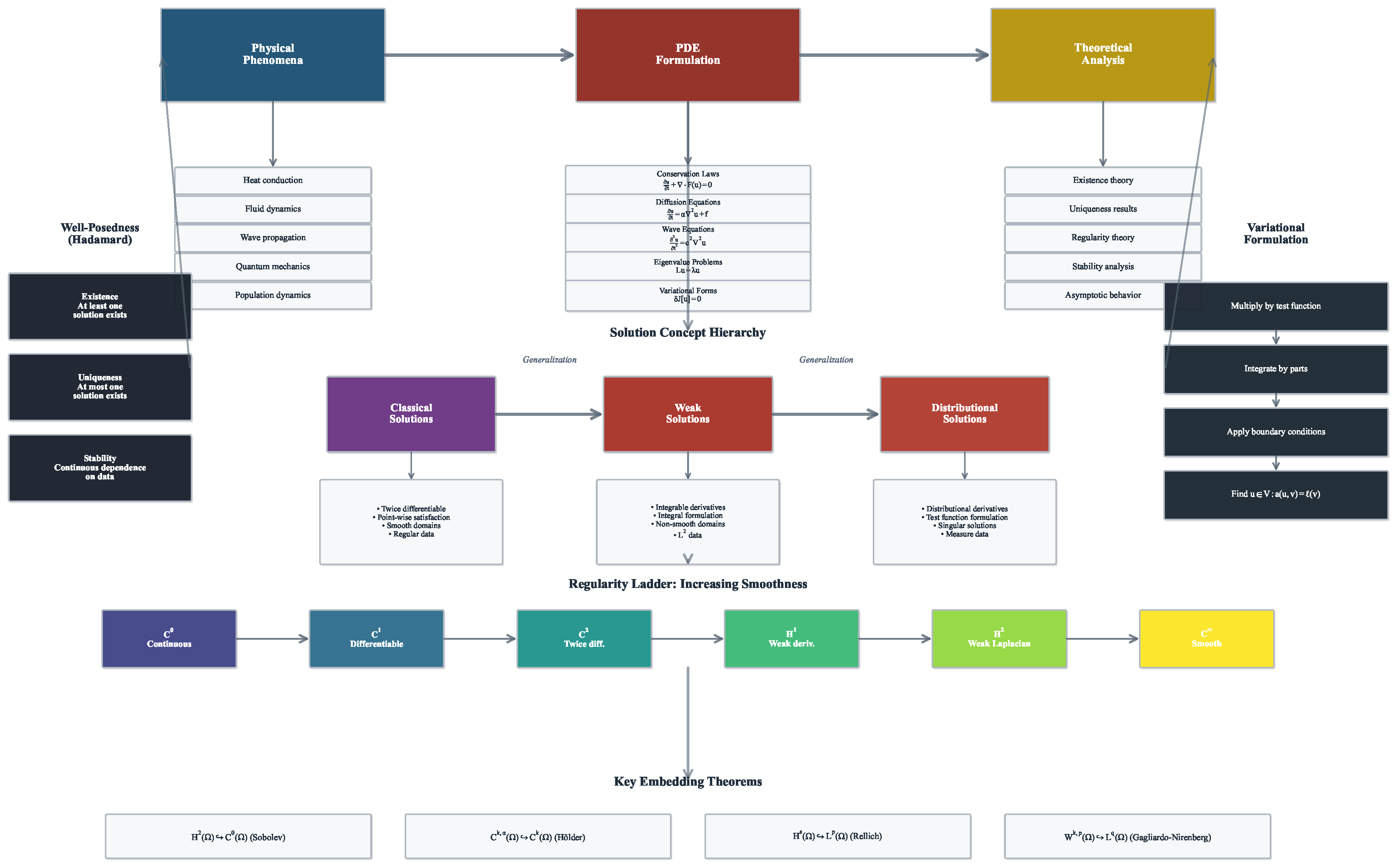

The proper specification of auxiliary conditions is crucial for ensuring well-posed PDE problems [

17,

35]. Boundary value problems involve specifying conditions on the spatial boundary of the domain [

36]. Dirichlet boundary conditions prescribe the solution values directly, as in

on

. Neumann conditions specify the normal derivative,

on

, representing flux conditions in physical applications. Mixed or Robin boundary conditions combine both types, often arising in heat transfer problems with convective cooling. The choice of boundary conditions must be physically meaningful and mathematically appropriate for the PDE type.

Initial value problems specify the solution and possibly its time derivatives at an initial time. For first-order time-dependent PDEs, specifying

suffices, while second-order equations like the wave equation require both

and

. The compatibility between initial and boundary conditions at corners and edges of the domain can significantly affect solution regularity and computational accuracy [

37,

38].

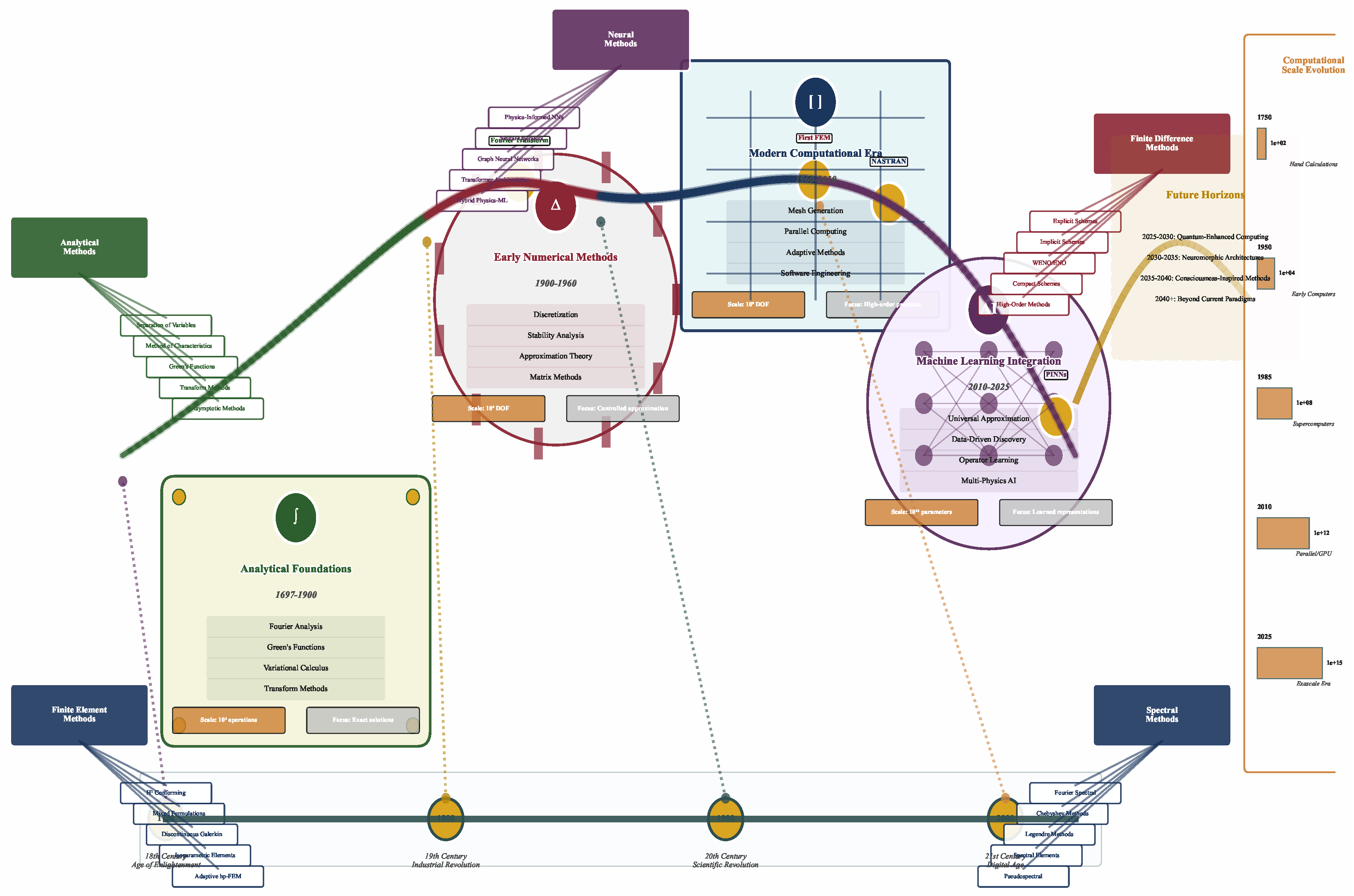

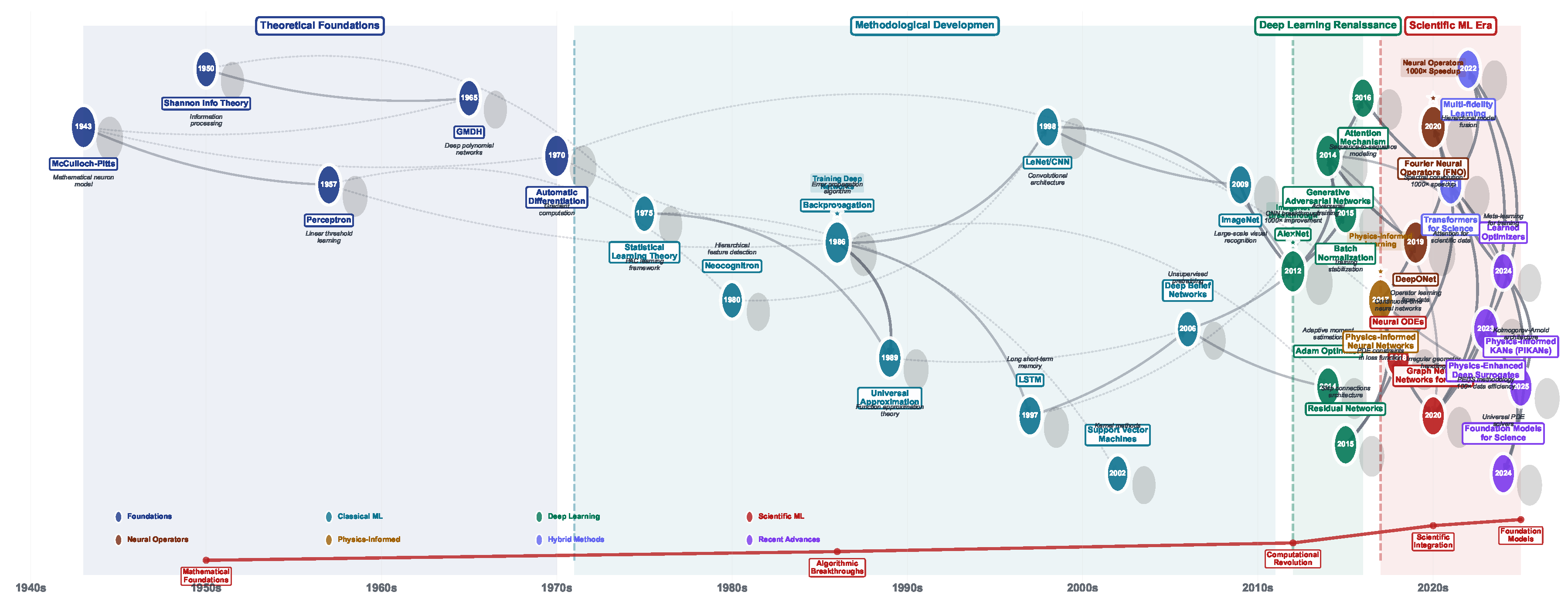

The evolution of numerical methods for PDEs reflects a continuous interplay between mathematical understanding, computational capabilities, and application demands. Traditional approaches, rooted in functional analysis and numerical linear algebra, have achieved remarkable success in solving a wide range of PDE problems. These methods, such as finite difference, finite element, and spectral methods, provide rigorous error estimates, conservation properties, and well-understood stability criteria [

38,

39,

40,

41]. However, they face significant challenges in high-dimensional problems due to the curse of dimensionality, struggle with complex geometries and moving boundaries, and often require extensive mesh generation and refinement strategies that can dominate the computational cost [

42,

43,

44,

45].

The emergence of machine learning approaches to PDE solving represents a paradigm shift in computational mathematics. Neural network-based methods, particularly physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and deep operator learning frameworks, offer the potential to overcome some traditional limitations [

15,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. These approaches can naturally handle high-dimensional problems, provide mesh-free solutions, and learn from data to capture complex solution behaviors. However, they introduce new challenges related to training efficiency, solution accuracy guarantees, and the interpretation of learned representations [

15,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. The integration of physical constraints and conservation laws into machine learning architectures [

50,

51,

52] remains an active area of research, with hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of traditional and machine learning methods [

53,

54,

55] showing particular promise.

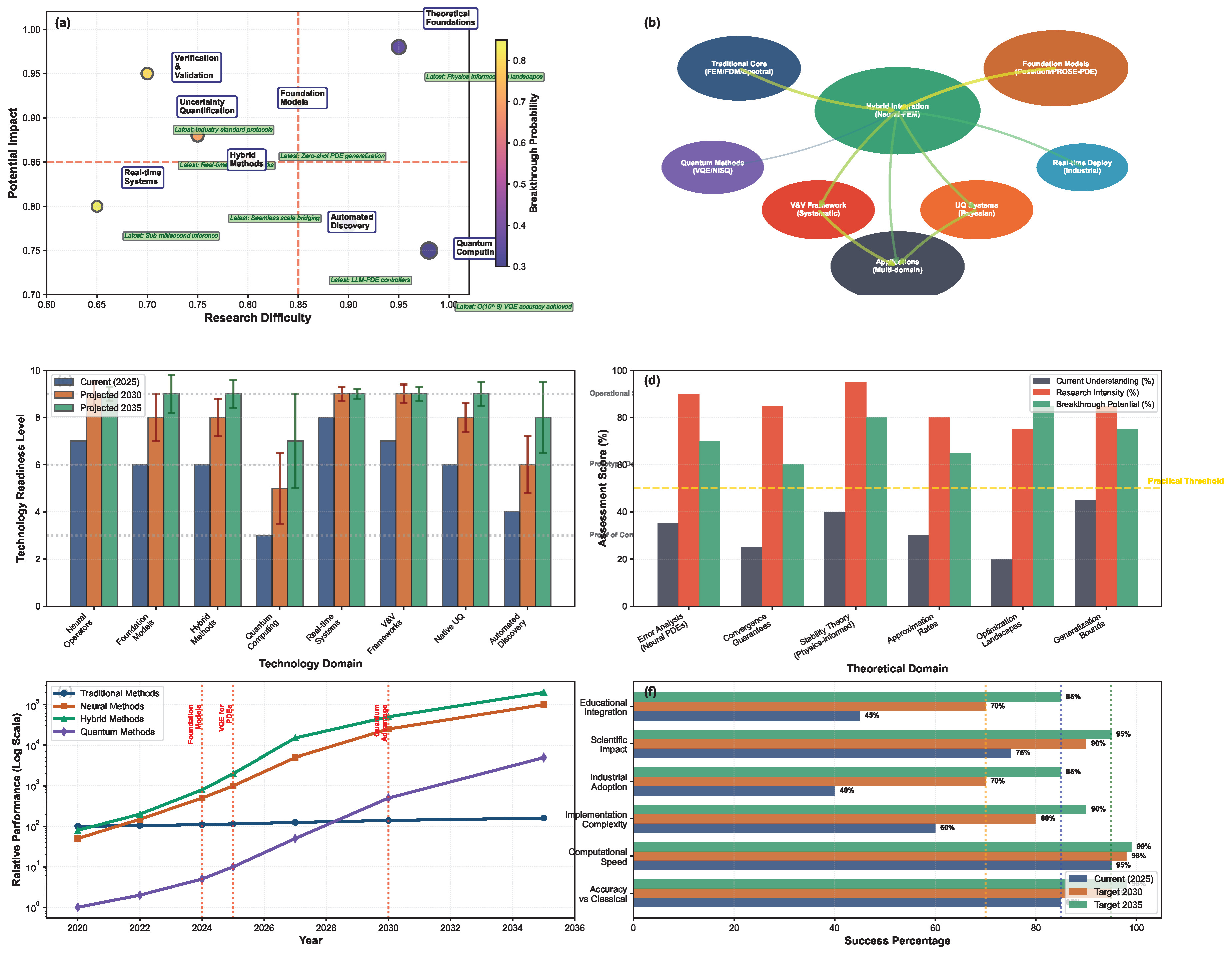

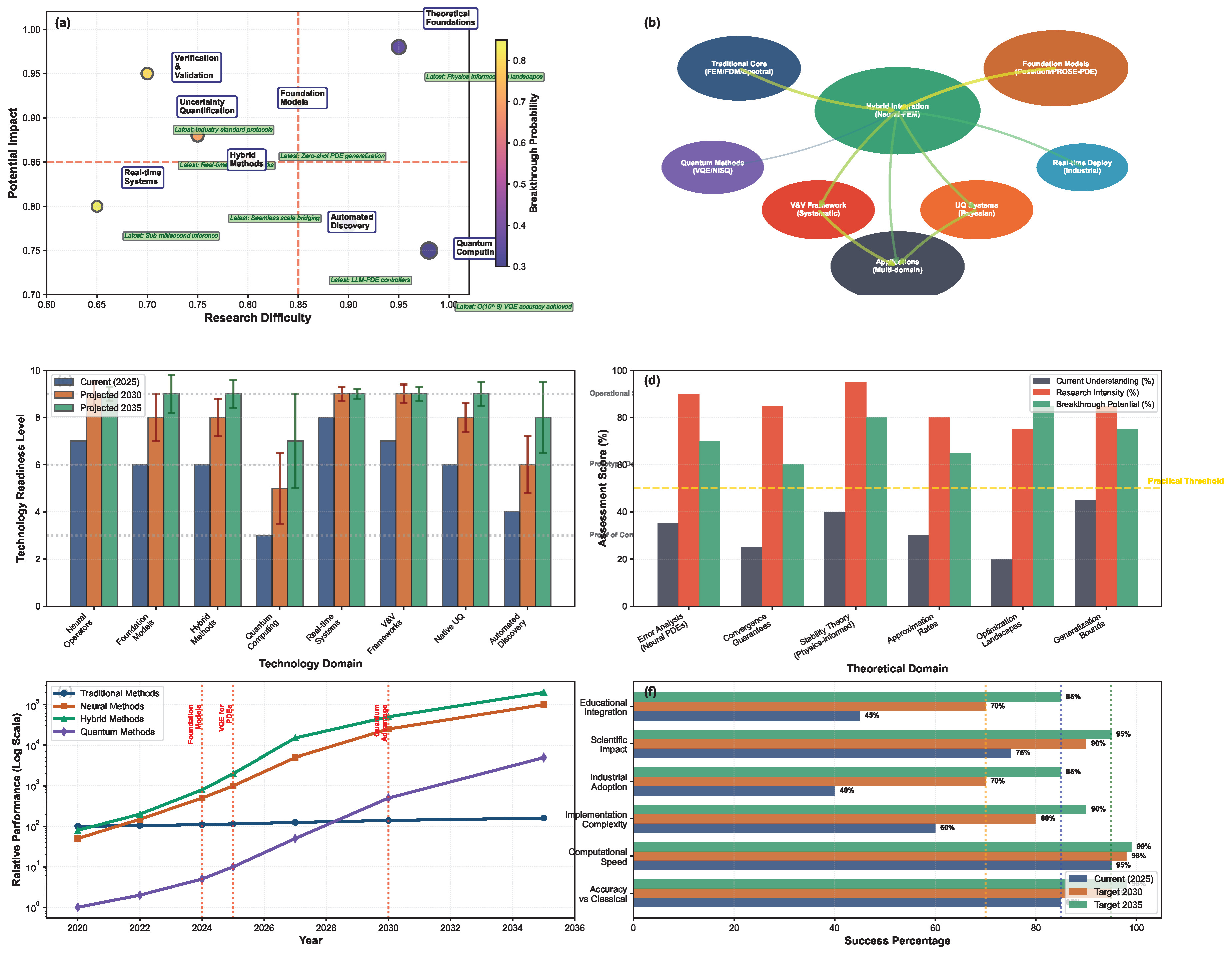

The present review aims to provide a state-of-the-art assessment of both traditional and machine learning methods for solving PDEs. We systematically examine the theoretical foundations, computational implementations, and practical applications of each approach. Throughout this review, we maintain a critical perspective, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each method and identifying open challenges that overcoming them may lead to more effective and efficient PDE solvers for the increasingly complex problems facing modern science and engineering.

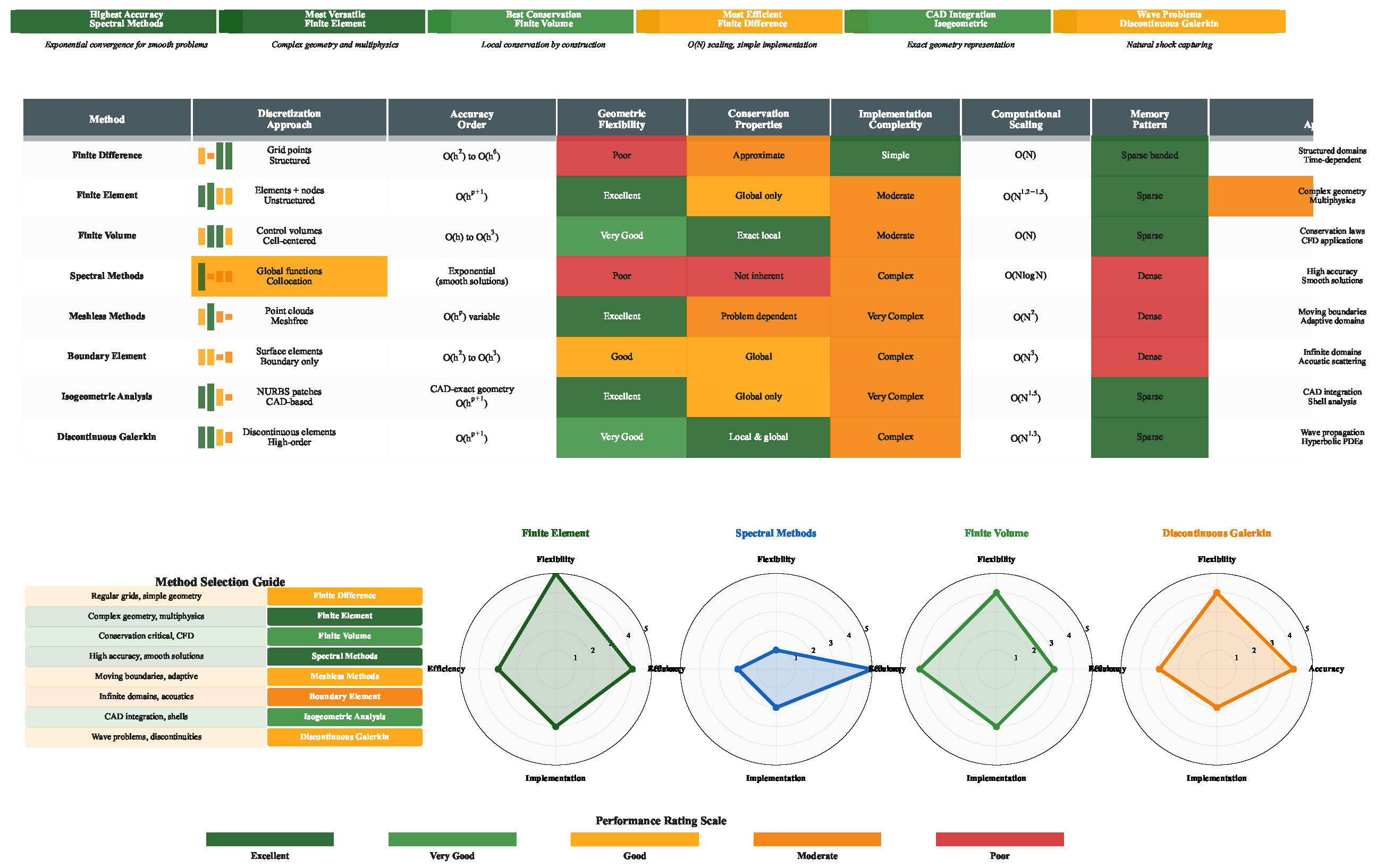

6. Critical Evaluation of Classical PDE Solvers

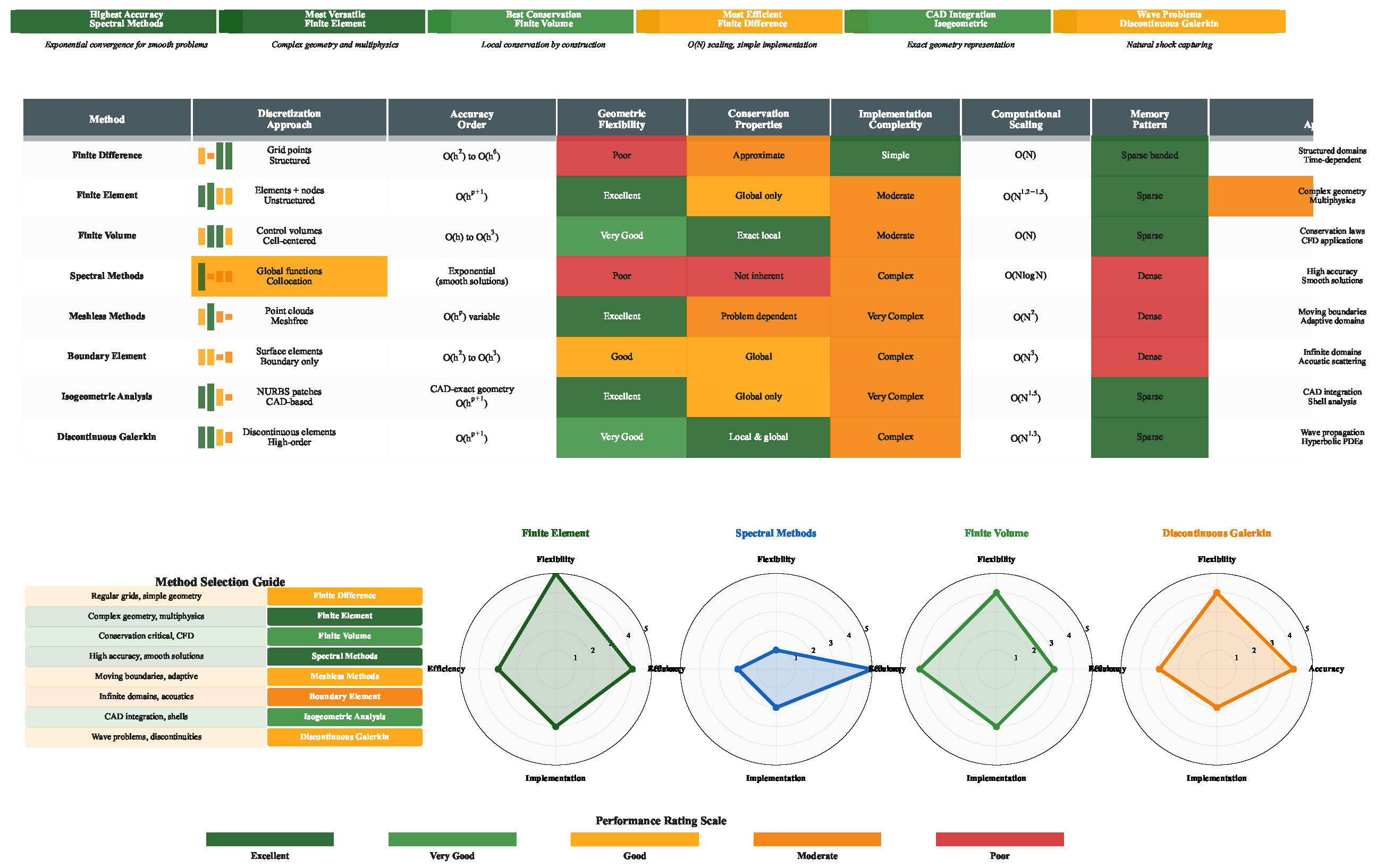

The computational solution of PDEs stands at a critical juncture where decades of mathematical innovation meet the practical constraints of modern computing architectures. It reflects a fundamental tension between theoretical elegance and practical utility. While mathematical analysis provides asymptotic complexity bounds and convergence guarantees, real-world performance depends critically on problem-specific characteristics, hardware constraints, and implementation quality. The analysis below examines the intricate trade-offs governing method selection, evaluating computational efficiency, accuracy characteristics, adaptive capabilities, and implementation complexities across the spectrum of classical and multiscale approaches. The systematic comparison presented in

Table 1 synthesizes these multifaceted considerations, providing quantitative metrics essential for informed method selection in contemporary scientific computing applications.

6.1. Computational Complexity Analysis: Beyond Asymptotic Bounds

The computational complexity of PDE solvers fundamentally constrains their applicability to large-scale scientific and engineering problems. While asymptotic complexity provides theoretical guidance, practical performance depends on numerous factors, including memory access patterns, vectorization efficiency, and hidden constants that can dominate for realistic problem sizes.

Classical finite difference methods, as detailed in

Table 1, exhibit favorable

complexity for explicit schemes, making them computationally attractive for hyperbolic problems where time accuracy requirements naturally limit time steps. However, this apparent efficiency masks significant limitations. The Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy stability constraint imposes

for hyperbolic equations and the more restrictive

for parabolic problems, potentially requiring millions of time steps for fine spatial resolutions. This quadratic scaling effectively transforms the linear per-step complexity into prohibitive total computational costs for diffusion-dominated problems.

Finite element methods demonstrate more nuanced complexity behavior, with standard h-version implementations requiring to operations per solution step. The superlinear scaling arises from multiple sources: sparse matrix assembly overhead, numerical integration costs that scale with element order, and iterative solver complexity that depends on condition number growth. The table reveals that p-version and hp-adaptive methods achieve superior accuracy-per-degree-of-freedom ratios, potentially offsetting their increased per-unknown costs through dramatic reductions in problem size. For smooth solutions, exponential convergence rates enable machine-precision accuracy with orders of magnitude fewer unknowns than low-order methods.

Spectral methods occupy a unique position in the complexity landscape, achieving

complexity through fast transform algorithms while delivering exponential convergence for smooth problems.

Table 1 indicates error levels of

to

for global spectral methods, unmatched by other approaches. However, this efficiency comes with stringent requirements: solution smoothness, simple geometries, and specialized boundary treatment. The spectral element method relaxes geometric constraints while maintaining spectral accuracy, though at increased complexity

due to inter-element coupling and local-to-global mappings.

The most striking complexity characteristics emerge in multiscale methods, where traditional scaling arguments break down. The Multiscale Finite Element Method exhibits complexity, where coarse-scale costs multiply with fine-scale basis construction expenses. This offline-online decomposition proves transformative for problems with fixed microstructure but becomes prohibitive when material properties evolve dynamically. The Heterogeneous Multiscale Method’s scaling reveals explicit dependence on spatial dimension d, highlighting the curse of dimensionality in microscale sampling.

6.2. Mesh Adaptivity: Intelligence in Computational Resource Allocation

Adaptive mesh refinement represents one of the most significant advances in computational efficiency, enabling orders-of-magnitude performance improvements for problems with localized features. The adaptivity characteristics summarized in

Table 1 reveal fundamental differences in how methods allocate computational resources.

Traditional h-refinement, available across finite element and finite volume methods, provides geometric flexibility through element subdivision. The standard FEM and discontinuous Galerkin methods support h-adaptivity with well-established error estimators and refinement strategies. However, implementation complexity increases substantially: adaptive methods require dynamic data structures, load balancing algorithms, and sophisticated error estimators. The "Medium" to "High" implementation difficulty ratings reflect these additional requirements beyond basic method implementation.

The p-refinement strategy, unique to polynomial-based methods, increases approximation order while maintaining fixed mesh topology. The table indicates that p-adaptive methods achieve errors of to , superior to h-refinement for smooth solutions. The spectral element method’s p-adaptivity enables local order variation, concentrating high-order approximation where solution smoothness permits, while maintaining robustness near singularities through lower-order elements.

Block-structured AMR, rated "Very High" in implementation difficulty, provides the most sophisticated adaptivity framework. The Berger-Colella algorithm enables hierarchical refinement with guaranteed conservation through flux correction procedures. The complexity includes overhead from managing refinement hierarchies, computing error indicators, and maintaining conservation at refinement boundaries. Despite implementation challenges, block-structured AMR remains essential for hyperbolic conservation laws where shock-tracking efficiency determines overall feasibility.

Multiscale methods introduce fundamentally different adaptivity concepts focused on basis function selection rather than geometric refinement. The Generalized Multiscale Finite Element Method’s complexity explicitly depends on the number of basis functions k, enabling adaptive enrichment through spectral decomposition of local problems. This approach proves particularly effective for heterogeneous media where traditional refinement would require prohibitive resolution of material interfaces.

6.3. Uncertainty Quantification: From Afterthought to Integral Design

The treatment of uncertainty in PDE solvers has evolved from post-processing add-ons to integral solution components, driven by recognition that deterministic solutions provide incomplete information for engineering decision-making. There is a stark divide between methods with native UQ support and those requiring external uncertainty propagation frameworks.

Classical methods—finite difference, standard finite elements, spectral methods—lack intrinsic uncertainty quantification capabilities, as indicated by "No" or "Limited" UQ support throughout the table. These methods require Monte Carlo sampling or surrogate modeling approaches that multiply baseline computational costs by the number of uncertainty samples. For a method with complexity and M uncertainty samples, total cost scales as , quickly becoming prohibitive for high-dimensional uncertainty spaces.

The Reduced Basis Method stands out with native "Yes" for UQ support, reflecting its fundamental design for parametric problems. The offline-online decomposition enables rapid parameter exploration with online complexity independent of full-model dimension N. This separation proves transformative: uncertainty propagation costs reduce from to where typically . The method’s strong theoretical foundations provide rigorous a posteriori error bounds accounting for both discretization and model reduction errors.

The Heterogeneous Multiscale Method’s "Limited" UQ support reflects emerging capabilities for uncertainty in microscale properties. By treating microscale parameters as random fields, HMM can propagate uncertainty through scale coupling, though theoretical foundations remain less developed than for single-scale methods. Recent advances in multilevel Monte Carlo methods show promise for combining multiscale modeling with efficient uncertainty propagation.

6.4. Nonlinearity Handling: The Persistent Challenge

Nonlinear PDEs expose fundamental differences in solver robustness and efficiency. Newton-Raphson methods, employed by finite element and spectral element approaches, offer quadratic convergence for sufficiently smooth problems with good initial guesses. However, the table’s complexity estimates often increase for nonlinear problems: finite element methods rise from to or higher due to Jacobian assembly and factorization costs. Each Newton iteration requires solving a linear system with complexity comparable to the linear problem, while multiple iterations compound costs. The "Medium" to "High" implementation difficulty reflects additional complexities: Jacobian computation, line search algorithms, and continuation methods for poor initial guesses.

Conservative finite volume methods employ problem-specific approaches like Godunov and MUSCL schemes that build nonlinearity treatment into the discretization. These methods maintain physical properties—positivity, maximum principles, and entropy conditions—that Newton-based approaches may violate during iteration. The trade-off appears in accuracy: finite volume methods typically achieve to errors compared to spectral methods’ to , reflecting the tension between robustness and accuracy.

Explicit time integration, marked throughout the table for hyperbolic problems, sidesteps nonlinear system solution at the cost of stability restrictions. The simplicity of explicit methods—"Low" implementation difficulty for basic finite differences—makes them attractive for problems where time accuracy requirements naturally limit time steps. However, implicit-explicit (IMEX) schemes, not separately listed but increasingly important, combine the advantages of both approaches for problems with multiple time scales.

Multiscale methods face compounded challenges from nonlinearity across scales. The Heterogeneous Multiscale Method’s "Constrained" nonlinearity handling reflects the need to maintain consistency between scales while iterating on nonlinear problems. Variational Multiscale Methods incorporate "Stabilized" formulations that add numerical dissipation scaled by local residuals, automatically adapting to nonlinearity strength.

6.5. Theoretical Foundations: Rigor to Meet Reality

The theoretical underpinnings of numerical methods, captured in the "Theory Bounds" column of

Table 1, profoundly influence their reliability and applicability. Methods with "Strong" theoretical foundations provide rigorous error estimates, stability guarantees, and convergence proofs, while those marked "Weak" or "Emerging" require empirical validation and careful application.

Finite element methods universally exhibit "Strong" theoretical foundations, reflecting decades of functional analysis development. The Céa lemma guarantees quasi-optimality in energy norms, while Aubin-Nitsche duality provides improved estimates. These results translate to practical benefits: reliable error indicators for adaptivity, robust convergence for well-posed problems, and systematic treatment of boundary conditions. The theoretical maturity enables confidence in finite element solutions even for complex industrial applications.

Spectral methods similarly benefit from strong theoretical foundations rooted in approximation theory. Exponential convergence for analytic functions follows from classical results on polynomial approximation in the complex plane. The connection between smoothness and convergence rate—explicit in Jackson and Bernstein theorems—guides practical application: spectral methods excel for smooth solutions but fail catastrophically for problems with discontinuities.

The contrast with meshless methods proves instructive. Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics shows "Weak" theoretical support despite widespread application in astrophysics and fluid dynamics. The lack of rigorous convergence theory manifests in practical difficulties: particle clustering, numerical instabilities, and unclear error estimation. The to error ranges reflect these theoretical limitations rather than implementation deficiencies.

Multiscale methods demonstrate varied theoretical maturity. Classical approaches like MsFEM and LOD possess "Strong" foundations based on homogenization theory and functional analysis. These rigorous results enable reliable error estimation and optimal basis construction. Conversely, Equation-Free Methods show "Emerging" theoretical support, reflecting their recent development and the challenges of analyzing methods that bypass explicit macroscale equations.

6.6. Implementation Complexity: The Hidden Cost of Sophistication

The implementation difficulty ratings (

Table 1) show a crucial but often overlooked aspect of method selection. While theoretical elegance and computational efficiency dominate academic discussions, implementation complexity frequently determines practical adoption in industrial and research settings.

"Low" difficulty methods—basic finite differences and explicit finite volume schemes—require only fundamental programming skills: array manipulations, loop structures, and basic numerical linear algebra. These methods can be implemented in hundreds of lines of code, debugged readily, and modified for specific applications. Their accessibility explains their persistent popularity despite their theoretical limitations.

"Medium" difficulty encompasses standard finite elements, spectral methods using FFTs, and cell-centered finite volumes. These methods demand understanding of data structures (sparse matrices, element connectivity), numerical integration, and iterative solvers. Modern libraries like FEniCS and deal.II mitigate complexity through high-level interfaces, though customization still requires substantial expertise.

"High" difficulty methods—hp-adaptivity, discontinuous Galerkin, radial basis functions—combine multiple sophisticated components. Implementation requires mastery of advanced data structures, parallel algorithms, and numerical analysis. The hp-FEM’s automatic refinement selection exemplifies this complexity: optimal strategies must balance error estimation, refinement prediction, and load balancing across processors.

"Very High" difficulty ratings correlate with research-frontier methods where standard implementations may not exist. Extended Finite Elements (XFEM) requires level set methods, enrichment functions, and specialized quadrature for discontinuous integrands. Algebraic multigrid demands graph algorithms, strength-of-connection metrics, and sophisticated smoothing strategies. These methods often require team efforts and years of development to achieve production quality.

6.7. Memory Efficiency and Architectural Considerations

Memory requirements often determine practical feasibility, particularly for three-dimensional problems. Memory access patterns, cache efficiency, and data structure choices profoundly impact real-world performance on modern hierarchical memory architectures.

Finite difference methods achieve optimal memory efficiency through their regular grid structure. Explicit schemes require minimal storage—solution arrays and geometric information—enabling solutions to problems limited only by available memory. The regular access patterns enable effective cache utilization and vectorization, explaining their continued competitiveness despite theoretical limitations.

Finite element methods incur substantial memory overhead from storing element connectivity, sparse matrix structures, and quadrature data. A typical tetrahedral mesh requires approximately 20-30 integers per element for connectivity, plus coordinate storage and degree-of-freedom mappings. Sparse matrix storage adds 12-16 bytes per nonzero entry, with bandwidth depending on element order and mesh structure. Higher-order methods exacerbate memory pressure through denser local matrices and increased quadrature requirements.

Spectral methods present contrasting memory characteristics. Global spectral methods require dense matrix storage for non-periodic problems, limiting applicability to moderate problem sizes despite superior accuracy. Spectral element methods balance accuracy with memory efficiency through block-sparse structures, though tensor-product bases still require careful implementation to avoid redundant storage.

Multiscale methods face unique memory challenges from maintaining multiple resolution levels simultaneously. The Multiscale FEM must store both coarse-scale matrices and fine-scale basis functions, potentially multiplying memory requirements. Efficient implementations exploit problem structure: periodic microstructures enable basis reuse, while localization properties permit compression of basis function data.

6.8. Performance Metrics Beyond Convergence Rates

The error ranges provide essential accuracy guidance but are not sufficient to characterize practical performance completely. Real-world applications demand consideration of multiple metrics that theoretical analysis often overlooks. Time-to-solution encompasses the complete computational pipeline: preprocessing (mesh generation, basis construction), solution computation, and post-processing. Spectral methods’ superior accuracy may be offset by complex boundary condition implementation. Finite element methods’ geometric flexibility comes at the cost of mesh generation, often consuming more human time than computation for complex geometries.

Robustness to parameter variations critically impacts industrial applications. Methods with strong theoretical foundations generally demonstrate predictable performance across parameter ranges, while empirical approaches may fail unexpectedly. The table’s error ranges partially capture this: narrow ranges (e.g., to for p-FEM) indicate consistent performance, while wide ranges (e.g., to for RBF) suggest parameter sensitivity.

Scalability on parallel architectures increasingly determines method viability for large-scale problems. Explicit methods’ nearest-neighbor communication patterns enable excellent weak scaling to millions of processors. Implicit methods face stronger scaling challenges from global linear system solutions, though domain decomposition and multigrid approaches partially mitigate these limitations. Spectral methods’ global coupling through transforms creates fundamental scaling barriers, limiting their application to moderate processor counts despite algorithmic advantages.

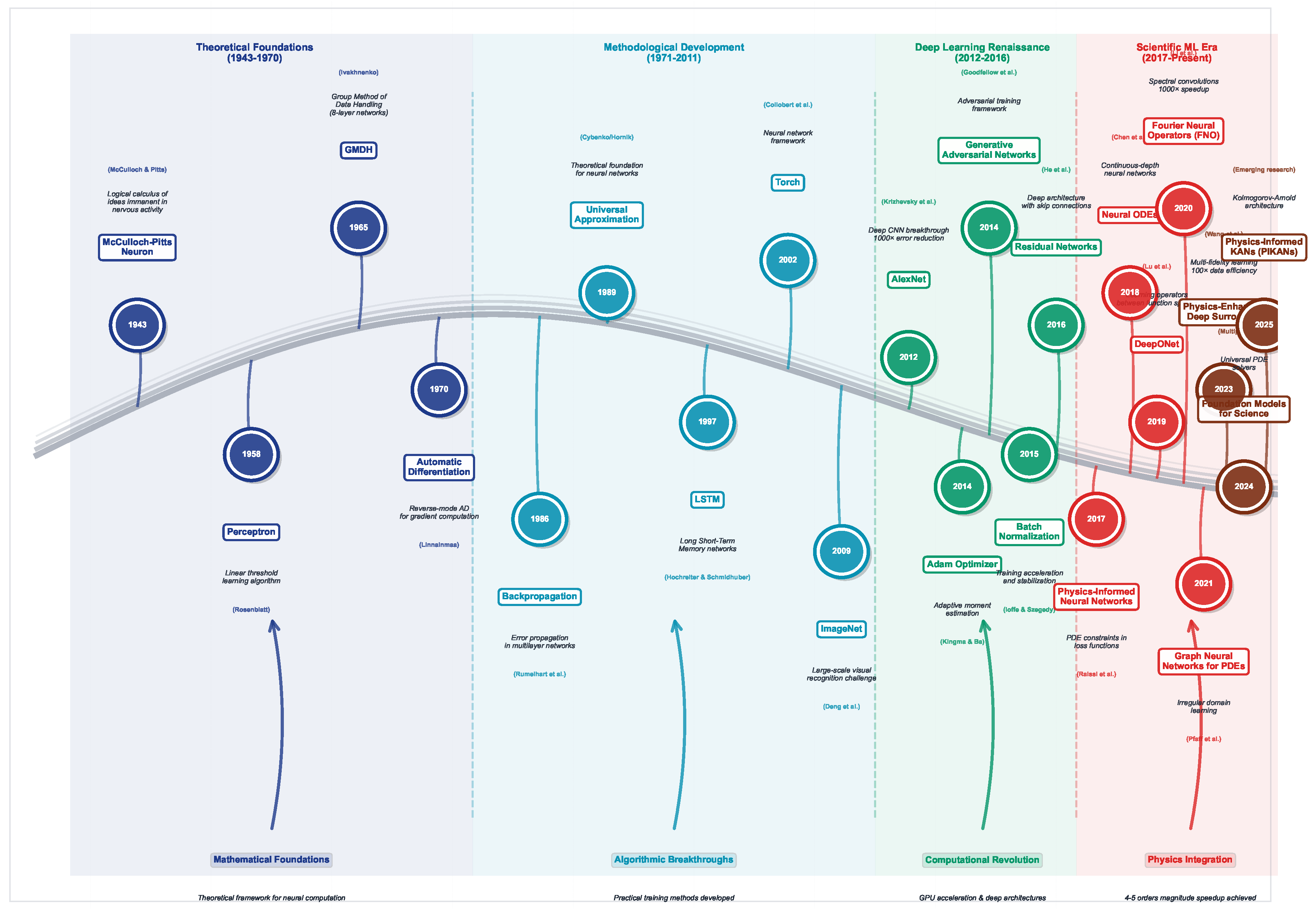

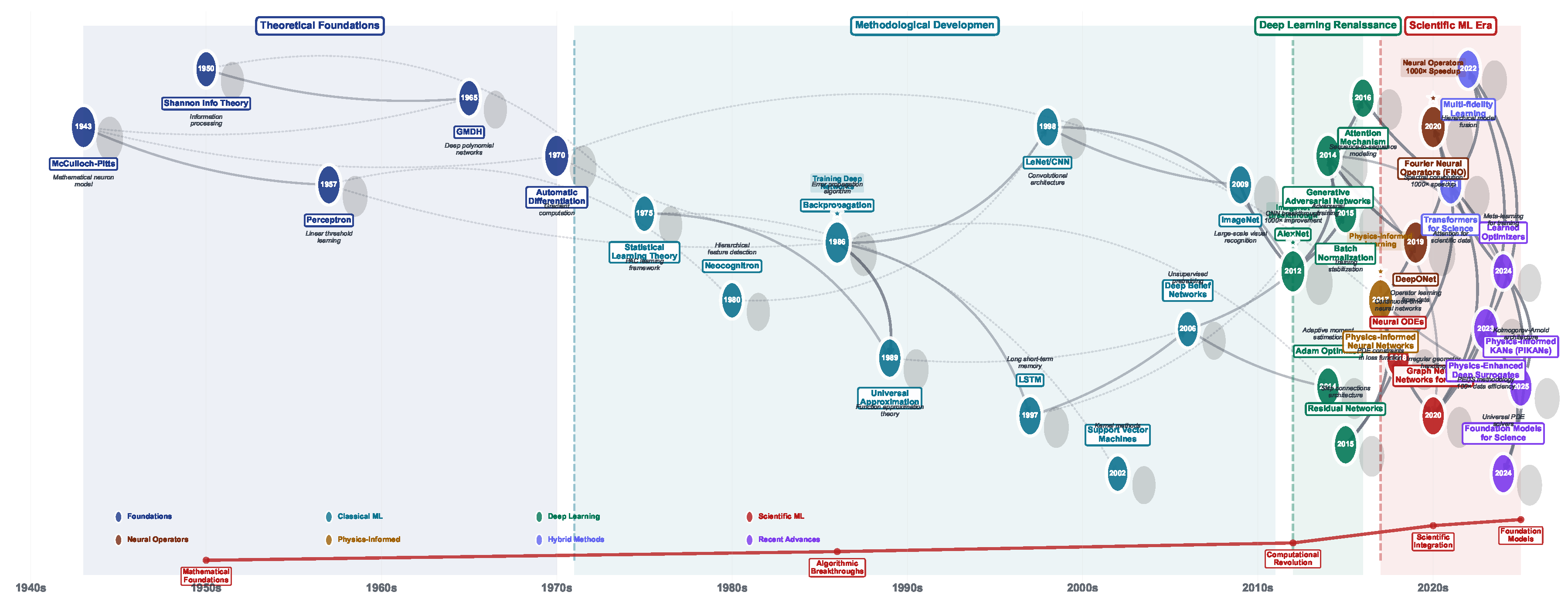

7. Machine Learning-Based PDE Solvers

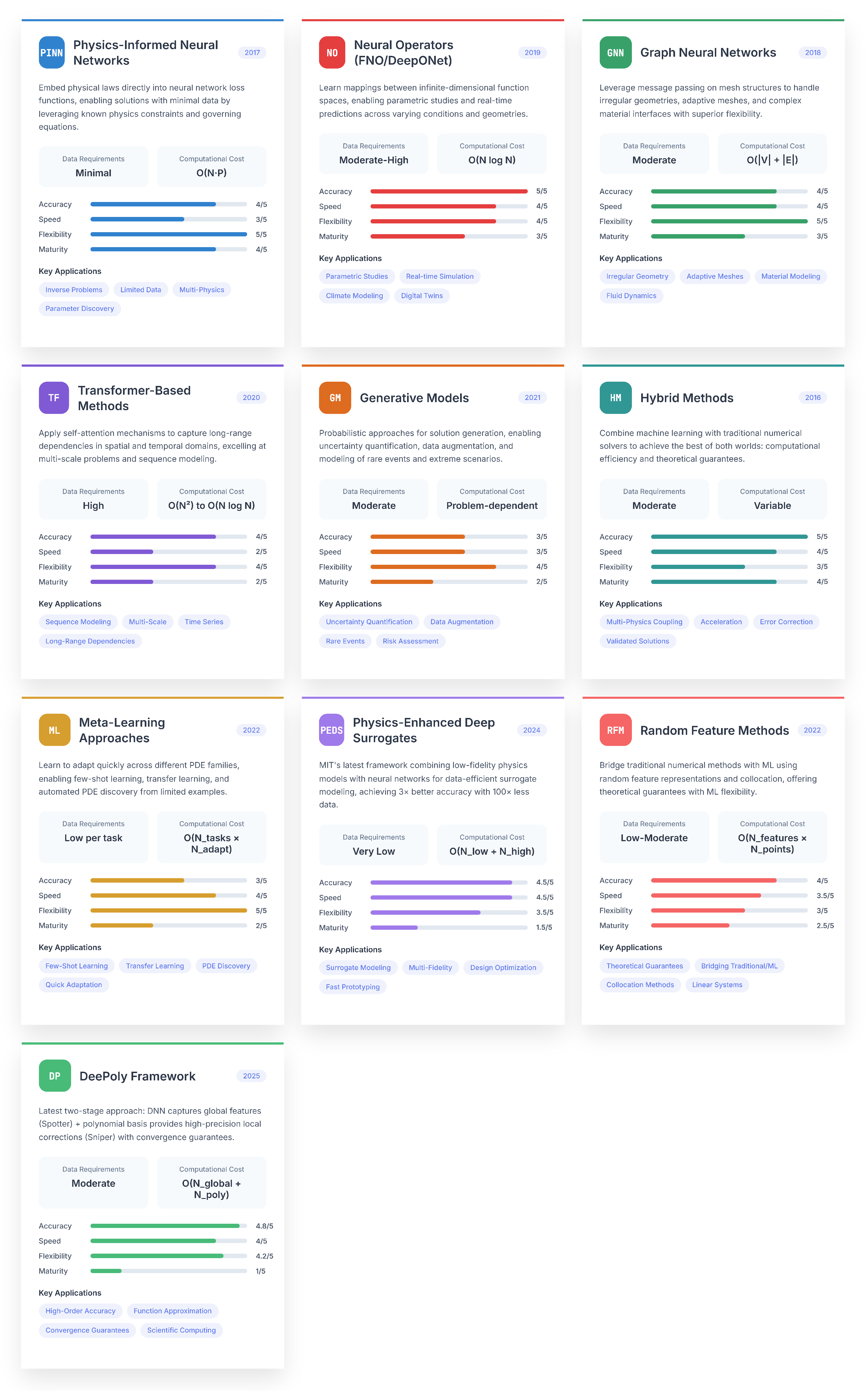

Machine learning (ML) approaches for solving PDEs represent a paradigm shift from traditional discretization-based methods, leveraging neural networks’ universal approximation capabilities to learn solution mappings directly from data or physical constraints. These methods are broadly categorized into major families in this section as outlined in

Table 2. Unlike conventional numerical methods that discretize domains and solve algebraic systems, ML-based solvers parameterize solutions through neural networks, optimizing network parameters to simultaneously satisfy boundary conditions, initial conditions, and governing equations. This approach offers distinctive advantages, including mesh-free formulations, natural handling of high-dimensional problems, and unified frameworks for both forward and inverse problems, while introducing new challenges in training dynamics, theoretical guarantees, and computational efficiency.

The machine learning approaches for solving PDEs has evolved rapidly, encompassing diverse methodologies from physics-informed neural networks to advanced neural operators and graph-based architectures.

Figure 7 provides an overview of this ecosystem, illustrating prominent method families with their respective performance characteristics, computational complexities, and optimal application domains. The categorization indicates the maturation of the field from early hybrid approaches (2016) to cutting-edge frameworks like Physics-Enhanced Deep Surrogates and DeePoly (2024-2025), while highlighting the trade-offs between data requirements, accuracy, and computational efficiency that guide practical method selection.

7.1. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

The Physics-Informed Neural Networks paradigm represents the most prominent and extensively studied approach in machine learning-based PDE solving [

43,

185]. PINNs embed physical knowledge directly into the neural network training process through composite loss functions that enforce both data constraints and physical laws encoded as differential equations [

46,

47]. This fundamental principle has spawned a rich ecosystem of variants addressing specific challenges in computational physics.

7.1.1. Core PINN Framework and Variants

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

The original PINN framework employs feedforward neural networks to approximate PDE solutions by minimizing a composite loss function [

43,

185]. The methodology parameterizes the solution

as a neural network

with parameters

, constructing a loss function comprising multiple components [

15,

46]:

where

enforces boundary conditions,

enforces initial conditions,

minimizes the PDE residual computed using automatic differentiation, and

incorporates available measurements. The PDE residual at collocation points

sampled throughout the domain is:

where

represents the differential operator. Implementation involves strategic sampling of collocation points, often using Latin hypercube sampling or adaptive strategies based on residual magnitudes.

Variational PINNs (VPINNs)

Variational Physics-Informed Neural Networks extend the classical framework by incorporating variational principles [

186,

187]. For problems admitting energy formulations, such as elasticity or electromagnetics, VPINNs minimize the variational energy functional:

where

is the energy functional and constraints enforce boundary conditions. This approach often exhibits superior convergence properties due to the natural coercivity of energy functionals. Implementation involves numerical integration over the domain using Monte Carlo sampling or quadrature rules.

Conservative PINNs (CPINNs)

Conservative Physics-Informed Neural Networks ensure strict satisfaction of conservation laws through architectural constraints or specialized loss formulations [

188]. For conservation laws

, CPINNs enforce:

This can be achieved through penalty methods or by parameterizing the solution in terms of stream functions that automatically satisfy conservation.

Deep Ritz Method

The Deep Ritz Method applies variational principles using neural networks as basis functions for elliptic PDEs [

189,

190]. The approach minimizes the energy functional:

The method naturally handles complex boundaries through penalty methods and achieves high accuracy for problems with smooth solutions.

Weak Adversarial Networks (WANs)

WANs employ adversarial training with generator networks approximating solutions and discriminator networks identifying PDE violations [

191,

192]. The generator minimizes:

while the discriminator maximizes its ability to detect PDE residuals. This formulation avoids explicit computation of high-order derivatives.

Extended PINNs (XPINNs)

XPINNs employ domain decomposition with multiple neural networks in subdomains, enabling parallel computation and better handling of complex geometries [

193,

194]. Interface conditions ensure continuity:

Additional flux conservation conditions may be imposed for conservation laws.

Multi-fidelity PINNs

Multi-fidelity PINNs leverage data of varying accuracy through transfer learning and correlation modeling [

195,

196]:

where

is a low-fidelity solution,

is a learned correlation, and

captures the discrepancy. Training proceeds hierarchically from low to high fidelity.

Adaptive PINNs

Adaptive PINNs incorporate dynamic strategies for network architecture, sampling, and loss weights. Residual-based adaptive sampling redistributes collocation points [

197,

198]:

where

controls the adaptation aggressiveness. Network architecture can grow through progressive training, adding neurons or layers based on convergence metrics.

7.1.2. Strengths and Advantages of PINNs

The PINN framework offers compelling advantages that have driven widespread adoption across scientific computing domains. The mesh-free nature represents a fundamental advantage, eliminating the computational overhead and geometric constraints of mesh generation. This proves particularly valuable for problems involving complex three-dimensional geometries, moving boundaries, or domains with intricate features where traditional meshing becomes prohibitively expensive or technically challenging. The ability to handle free boundary problems, inverse problems, and domains with holes or irregular shapes without specialized treatment provides unprecedented flexibility.

PINNs demonstrate exceptional capability in solving inverse problems where unknown parameters, source terms, or boundary conditions must be inferred from sparse observations. The unified framework treats forward and inverse problems identically, with unknown quantities simply becoming additional trainable parameters. This eliminates the need for adjoint methods or iterative regularization schemes required by traditional approaches. Applications in parameter identification, source localization, and data assimilation have shown PINNs can recover unknown fields from minimal data, even in the presence of noise.

The framework’s ability to naturally incorporate heterogeneous data sources represents a significant practical advantage. PINNs can simultaneously assimilate experimental measurements at arbitrary locations, enforce known boundary conditions, satisfy governing equations, and incorporate prior knowledge through regularization terms. This data fusion capability proves invaluable in real-world applications where information comes from diverse sources with varying reliability and coverage.

For high-dimensional problems, PINNs avoid the exponential scaling curse that plagues grid-based methods. The computational cost scales with the number of collocation points (typically ) rather than the full grid size ( for d dimensions). This makes previously intractable problems computationally feasible, with applications in quantum mechanics (many-body Schrödinger equations), financial mathematics (high-dimensional Black-Scholes equations), and statistical mechanics demonstrating orders of magnitude computational savings.

The continuous representation learned by PINNs provides solutions at arbitrary resolution without interpolation errors. Once trained, the network can be queried at any spatial or temporal location with negligible computational cost, enabling applications requiring variable resolution, real-time evaluation, or repeated queries at non-grid points. This property proves particularly valuable for visualization, design optimization, and control applications.

Automatic differentiation infrastructure provides exact derivatives to machine precision without discretization errors. This eliminates numerical dispersion, dissipation, and truncation errors associated with finite difference approximations, potentially achieving higher accuracy for problems requiring precise gradient computations. The exact enforcement of differential equations at collocation points, rather than approximate satisfaction on grid cells, can lead to superior accuracy for smooth solutions.

7.1.3. Limitations and Challenges of PINNs

Despite their advantages, PINNs face fundamental limitations that may constrain their applicability and effectiveness in many scenarios. Training dynamics represent perhaps the most significant challenge, with the multi-objective nature of the loss function creating complex, often pathological optimization landscapes. The competition between different loss terms frequently leads to poor convergence, with one component dominating others during training. Recent research has identified this as a fundamental issue related to the gradient flow dynamics, where gradients from different loss components can have vastly different magnitudes and conflicting directions.

The spectral bias phenomenon, where neural networks preferentially learn low-frequency components, severely limits PINN performance for solutions containing sharp gradients, boundary layers, or high-frequency oscillations. This bias stems from the neural network architecture and initialization, causing slow convergence or complete failure to capture fine-scale features. Solutions with shocks, discontinuities, or rapid transitions remain particularly challenging, often requiring specialized architectures or training procedures that complicate implementation.

Accuracy limitations become apparent when comparing PINNs to mature traditional methods. For smooth problems where spectral or high-order finite element methods excel, PINNs typically achieve only moderate accuracy, with relative errors of to compared to machine precision () achievable by traditional methods. The stochastic nature of training introduces variability, with different random seeds potentially yielding significantly different solutions. This non-deterministic behavior complicates verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification procedures essential for scientific computing.

Computational efficiency during training poses significant practical challenges. While inference is fast, the training phase often requires to iterations for convergence, with each iteration involving forward passes, automatic differentiation, and evaluation of multiple loss components. For time-dependent problems, the computational cost can exceed that of traditional time-stepping methods, particularly for long-time integration where error accumulation becomes problematic. The global nature of neural network approximations contrasts with the local support of traditional basis functions, potentially limiting parallel scalability.

Theoretical understanding remains limited compared to traditional numerical methods. The lack of rigorous error bounds, stability analysis, and convergence guarantees creates uncertainty about solution reliability. Recent theoretical work has begun establishing approximation results for specific cases, but a comprehensive analysis comparable to finite element or spectral methods remains elusive. The interaction between network architecture, optimization algorithms, and PDE properties lacks systematic understanding, making method design more art than science.

Hyperparameter sensitivity plagues practical implementation, with performance critically dependent on network architecture, activation functions, initialization strategies, optimizer choice, learning rates, and loss weight balancing. The absence of systematic guidelines for these choices necessitates expensive trial-and-error experimentation. The weighting parameters in the loss function require particularly careful tuning, with poor choices leading to training failure or inaccurate solutions.

7.2. Neural Operator Methods

Neural Operator methods represent a paradigm shift from learning individual solutions to learning mappings between function spaces. Unlike PINNs that solve specific PDE instances, neural operators learn the solution operator that maps input functions (initial conditions, boundary conditions, or source terms) to solution functions. This approach enables instant evaluation for new problem instances without retraining, making them particularly powerful for parametric studies, design optimization, and uncertainty quantification.

7.2.1. Principal Neural Operator Architectures

Fourier Neural Operator (FNO)

The Fourier Neural Operator leverages spectral methods within neural architectures, parameterizing integral operators through learnable filters in Fourier space. The key insight is that many differential operators become algebraic in Fourier space, enabling efficient learning. The operator is parameterized as:

where

represents learnable Fourier coefficients (typically truncated to lower frequencies),

is a pointwise linear transform, and

,

denote the Fourier transform and its inverse. The complete architecture stacks multiple Fourier layers:

Implementation leverages FFT for

complexity, with careful treatment of boundary conditions through padding strategies.

Deep Operator Network (DeepONet)

DeepONet employs a branch-trunk architecture inspired by the universal approximation theorem for operators. The operator is decomposed as:

where the branch network

encodes input functions evaluated at sensor locations, and the trunk network

provides continuous basis functions. This architecture naturally handles multiple input functions and vector-valued outputs through appropriate modifications.

Graph Neural Operator (GNO)

GNO extends operator learning to irregular domains using graph representations. The methodology leverages message passing on graphs constructed from spatial discretizations:

where

is a learned kernel function encoding geometric relationships. The architecture maintains discretization invariance through careful normalization.

Multipole Graph Networks (MGN)

MGN incorporates hierarchical decompositions inspired by fast multipole methods, enabling efficient computation of long-range interactions:

where

are multipole expansions and

are learned coefficients. This achieves

or

scaling for problems with global coupling.

Neural Integral Operators

These methods directly parameterize integral operators through neural networks:

where

is a neural network taking pairs of coordinates. Implementation uses Monte Carlo integration or quadrature rules, with variance reduction techniques for efficiency.

Wavelet Neural Operator

WNO employs wavelet transforms for multi-resolution operator learning:

where

represents wavelet filters at different scales. This naturally captures multiscale features and provides localization in both space and frequency.

Transformer Neural Operator

TNO adapts attention mechanisms for operator learning:

where

are attention weights computed from query location

y and key locations

. This provides adaptive, input-dependent basis functions.

Latent Space Model Neural Operators

LSM-based operators learn in compressed representations:

where

and

are encoder/decoder networks and

operates in low-dimensional latent space, dramatically reducing computational costs.

7.2.2. Strengths and Advantages of Neural Operators

Neural operators offer transformative advantages for parametric PDE problems requiring multiple solutions. The fundamental strength lies in learning solution operators rather than individual solutions, enabling instant evaluation for new parameter configurations without retraining. Once trained, evaluating solutions for new initial conditions, boundary conditions, or PDE parameters requires only a forward pass, taking milliseconds, compared to minutes or hours for traditional solvers. This speedup of to times enables previously infeasible applications like real-time control, interactive design exploration, and large-scale uncertainty quantification.

Resolution invariance represents a unique capability that distinguishes neural operators from both traditional methods and other ML approaches. Models trained on coarse grids can evaluate solutions on fine grids or at arbitrary continuous locations without retraining. This discretization-agnostic property stems from learning in function space rather than on specific discretizations. The ability to train on heterogeneous data sources with varying resolutions proves invaluable for incorporating experimental data, multi-fidelity simulations, and adaptive mesh computations within a unified framework.

The learned operators often capture physically meaningful reduced-order representations, providing insight into dominant solution modes and effective dimensionality. The operator viewpoint naturally handles multiple input-output relationships, learning complex mappings between different physical fields without requiring specialized coupling procedures. This proves particularly valuable for multi-physics problems where traditional methods require sophisticated and problem-specific coupling strategies.

Theoretical foundations for neural operators continue to strengthen, with recent work establishing universal approximation theorems and approximation rates for various architectures. The connection to classical approximation theory through kernel methods and spectral analysis provides a mathematical framework for understanding capabilities and limitations. The operator learning paradigm also enables systematic treatment of inverse problems, where the forward operator is learned from data and then inverted using optimization or sampling techniques.

7.2.3. Limitations and Challenges of Neural Operators

Despite their advantages, neural operators face challenges. Data requirements represent the primary constraint, with training typically requiring thousands to millions of input-output function pairs. Generating this training data through traditional simulations can dominate total computational cost, limiting applicability to problems where data generation is expensive. The quality of learned operators directly depends on training data coverage, with poor generalization to parameter regimes, boundary conditions, or forcing terms outside the training distribution.

Accuracy degradation for complex problems remains problematic. While neural operators excel for smooth solutions and moderate parameter variations, performance deteriorates for problems with sharp interfaces, shocks, or extreme parameter ranges. FNO’s global spectral basis can produce Gibbs phenomena near discontinuities, while DeepONet’s finite basis decomposition may inadequately capture complex solution manifolds. The fixed architecture assumption that works well for one problem class may fail for others, requiring problem-specific architectural choices.

Memory and computational requirements during training can be substantial. FNO requires storing Fourier transforms of all training samples, with memory scaling as . The need to process entire functions rather than local patches limits batch sizes and can necessitate specialized hardware. Training instability, particularly for GNO and attention-based variants, requires careful initialization and learning rate scheduling.

While improving, theoretical understanding remains incomplete. Approximation guarantees typically require strong assumptions about operator regularity that may not hold for practical problems. The effect of discretization on learned operators, optimal architecture choices for different operator classes, and connections to classical numerical analysis remain active research areas. Error propagation in composed operators and long-time integration stability lacks a comprehensive analysis.

7.3. Graph Neural Network Approaches

Graph Neural Network approaches for PDE solving leverage the natural graph structure present in computational meshes, particle systems, and discretized domains. By treating spatial discretizations as graphs with nodes representing solution values and edges encoding connectivity, GNNs learn local interaction patterns that generalize across different mesh topologies and resolutions. This paradigm connects traditional mesh-based methods with modern deep learning, maintaining geometric flexibility while exploiting neural networks’ approximation capabilities.

7.3.1. Key GNN Architectures for PDEs

MeshGraphNets

MeshGraphNets encode mesh-based discretizations using an encoder-processor-decoder architecture tailored for physical simulations. The encoder maps mesh features to latent representations:

The processor applies multiple message-passing steps:

The decoder produces solution updates:

This architecture naturally handles unstructured meshes and supports adaptive refinement.

Neural Mesh Refinement

This approach uses GNNs to predict optimal mesh refinement patterns:

where

indicates the refinement needed. The method learns from optimal refinement examples, going beyond traditional error indicators.

Multiscale GNNs

These architectures process information at multiple resolution levels through hierarchical graph structures:

This enables efficient processing of multiscale phenomena.

Physics-Informed GNNs

PI-GNNs incorporate physical constraints into message passing:

where

encodes known physical interactions (e.g., inverse distance for gravitational forces).

Geometric Deep Learning for PDEs

This framework ensures equivariance to geometric transformations:

for transformations

in the symmetry group. Implementation uses specialized layers respecting geometric structure.

Simplicial Neural Networks

These networks operate on simplicial complexes, generalizing beyond graph edges:

where

and

denote lower and upper adjacent simplices, enabling representation of higher-order geometric relationships.

7.3.2. Strengths and Advantages of GNN Approaches

GNN methods excel at handling irregular geometries and unstructured meshes without special treatment, providing natural generalization across different mesh topologies. The local message passing mechanism mirrors physical interactions in PDEs, providing a strong inductive bias that improves sample efficiency and generalization. Unlike methods requiring fixed grids, GNNs seamlessly handle adaptive mesh refinement, moving meshes, and topological changes during simulation.

The framework naturally supports multi-physics coupling through heterogeneous node and edge types, enabling unified treatment of coupled PDE systems. Different physical quantities can be represented as node features, while edge types can encode different interaction types. This flexibility extends to multi-scale problems where different regions require different physics models or resolution levels.

Interpretability represents a key advantage, with learned message passing functions often corresponding to discretized differential operators. This connection facilitates validation against traditional methods and provides physical insight into learned representations. The local nature of computations enables efficient parallel implementation with communication patterns similar to traditional domain decomposition methods.

GNNs demonstrate strong generalization to new mesh configurations, learning robust solution operators that transfer across different discretizations. This mesh-agnostic property proves valuable for problems where optimal meshing is unknown or changes during simulation. The ability to incorporate geometric features (angles, areas, curvatures) as edge or node attributes enables learning of geometry-aware solution strategies.

7.3.3. Limitations and Challenges of GNN Approaches

GNN methods struggle with long-range interactions, requiring information propagation through many message-passing steps. Each layer typically aggregates information from immediate neighbors, necessitating deep networks for global dependencies. This can lead to over-smoothing, where node features become indistinguishable, or gradient vanishing/explosion during training. Problems with strong non-local coupling may require specialized architectures or auxiliary global information pathways.

Theoretical understanding remains limited compared to traditional discretization methods. Approximation capabilities, stability properties, and convergence guarantees for GNN-based PDE solvers lack comprehensive analysis. The connection between the number of message passing steps, mesh resolution, and solution accuracy remains poorly understood. Error accumulation in time-dependent problems and long-term stability requires further investigation.

Dependence on mesh quality can significantly impact solution accuracy. While GNNs handle irregular meshes, highly skewed elements or extreme size variations can degrade performance. The implicit discretization learned by the network may not satisfy important properties like conservation or maximum principles without explicit enforcement, leading to unphysical solutions for certain problem classes.

Training requires diverse mesh configurations to ensure generalization, significantly increasing data generation costs. The distribution of training meshes must adequately cover expected test scenarios, including different resolutions, element types, and geometric configurations. Poor coverage leads to degraded performance on novel mesh types.

Implementation complexity exceeds standard neural networks, requiring specialized graph processing libraries and careful handling of variable-size inputs. Batching graphs with different sizes requires padding or specialized data structures. Memory requirements for storing graph connectivity can become substantial for large meshes, potentially limiting scalability.

7.4. Transformer and Attention-Based Methods

Transformer architectures bring the power of attention mechanisms to PDE solving, enabling models to capture long-range dependencies and complex interactions without the architectural constraints of local operations. By treating spatial and temporal coordinates as sequences, these methods can dynamically focus computational resources on relevant features, providing adaptive and interpretable solution strategies.

7.4.1. Transformer Variants for PDEs

Galerkin Transformer

The Galerkin Transformer combines variational methods with transformer architectures, learning optimal basis functions and their interactions through attention mechanisms. The solution is represented as:

where basis functions

and coefficients

are determined through attention:

The architecture learns to discover problem-specific basis functions that optimally represent solutions.

Factorized FNO

This architecture addresses FNO’s computational limitations through low-rank decompositions:

where the rank

is adapted through attention mechanisms:

U-FNO

U-FNO combines U-Net’s multi-scale processing with Fourier transforms:

where attention mechanisms fuse information across scales.

Operator Transformer

This architecture directly learns operator mappings using encoder-decoder attention:

where

denotes positional encodings adapted for continuous domains.

PDEformer

PDEformer incorporates domain-specific inductive biases through specialized attention patterns:

where

encodes physical priors such as locality, causality, or symmetries. Multi-head attention captures different physical interactions:

with heads specialized for different phenomena (diffusion, advection, reaction).

7.4.2. Strengths and Advantages of Transformer Methods

Transformer-based methods offer unique advantages through their global receptive fields and adaptive computation. Unlike CNNs or GNNs that build global understanding through successive local operations, transformers can capture long-range dependencies from the first layer. This proves particularly valuable for problems with non-local interactions, integral equations, or global constraints that are challenging for local methods.

The attention mechanism provides natural interpretability, revealing which spatial or temporal regions most influence predictions at any point. Attention weights can be visualized and analyzed to understand solution strategies, validate physical consistency, and debug model behavior. This interpretability exceeds that of black-box neural networks, approaching the transparency of traditional numerical methods.

Adaptive computation through attention enables efficient resource allocation, focusing on regions requiring high resolution while spending less computation on smooth areas. This data-dependent processing can outperform fixed discretizations, particularly for problems with localized features or moving fronts. The framework naturally handles variable-length sequences and irregular sampling, accommodating diverse data sources and adaptive discretizations.

The flexibility of transformer architectures enables straightforward incorporation of multiple modalities and auxiliary information. Physical parameters, boundary conditions, and observational data can be encoded as additional tokens, with attention mechanisms learning appropriate interactions. This unified treatment simplifies multi-physics coupling and parameter-dependent problems.

Recent theoretical work has begun establishing transformers’ approximation capabilities for operator learning, showing that they can efficiently approximate certain classes of integral operators. The connection to kernel methods through attention mechanisms provides a mathematical framework for analysis.

7.4.3. Limitations and Challenges of Transformer Methods

The quadratic computational complexity with sequence length represents the primary limitation, restricting applicability to moderate-scale problems. For 3D simulations requiring grid points, storing attention matrices requires prohibitive memory. Various linear attention mechanisms have been proposed, but often sacrifice expressiveness or require problem-specific design.

Transformer-based PDE solvers suffer from training instability, and careful initialization, learning rate scheduling, and architectural choices are required for convergence. The optimization landscape appears more complex than for specialized architectures, and training often requires significantly more iterations. Warm-up schedules, gradient clipping, and specialized optimizers become necessary, increasing implementation complexity.

The global attention mechanism may be inefficient for problems with primarily local interactions, where traditional methods or local architectures excel. The transformer must learn to ignore irrelevant long-range connections, potentially wasting model capacity. Problems well-suited to local discretizations may see limited benefit from global attention.

Position encoding for continuous domains remains an open challenge. Standard sinusoidal encodings from NLP do not naturally extend to irregular domains or account for geometric properties. Learned position encodings can overfit to training configurations, limiting generalization. Recent work on continuous position encodings shows promise but lacks a comprehensive evaluation.

Limited specialized implementations for scientific computing hamper practical adoption. While transformer libraries are mature for NLP and computer vision, adaptations for PDE solving require custom development. Efficient implementations leveraging sparsity patterns or physical structure remain underexplored.

7.5. Generative and Probabilistic Models

Generative and probabilistic models are moving from deterministic point estimates to modeling solution distributions. This approach naturally handles uncertainty from multiple sources—incomplete initial conditions, noisy measurements, uncertain parameters, and inherent stochasticity—providing not just predictions but confidence assessments crucial for decision-making under uncertainty.

7.5.1. Probabilistic PDE Solving Approaches

Score-based PDE Solvers

Score-based methods leverage diffusion models to solve PDEs by learning the score function (gradient of log-probability) of solution distributions. The approach treats PDE solving as a generative process where solutions are sampled from learned distributions. The forward diffusion process gradually corrupts PDE solutions:

The reverse process, guided by the learned score function

, generates solutions:

PDE constraints are incorporated through conditional sampling or modified score matching objectives that penalize constraint violations.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for PDEs

VAEs learn compressed probabilistic representations of PDE solutions, enabling efficient sampling and uncertainty quantification. The encoder network

maps solutions to latent distributions, while the decoder

reconstructs solutions. The training objective combines reconstruction with PDE constraints:

The latent space captures solution variability, enabling interpolation and extrapolation in parameter space.

Normalizing Flows for PDEs

Normalizing flows construct exact probabilistic models through invertible transformations. A sequence of bijective functions

transforms simple distributions to complex solution distributions:

The exact likelihood is computed through the change of variables formula:

PDE constraints are enforced through constrained optimization or specialized flow architectures.

Neural Stochastic PDEs

These methods explicitly model stochastic PDEs with random forcing or coefficients:

Neural networks parameterize both drift

and diffusion

terms. Training uses stochastic trajectory matching:

Bayesian Neural Networks for PDEs

BNNs quantify epistemic uncertainty by placing distributions over network parameters:

Variational inference approximates the posterior

by minimizing:

Multiple samples from

provide uncertainty estimates.

7.5.2. Strengths and Advantages of Generative Models

Generative and probabilistic models offer advantages for real-world PDE applications where uncertainty is inherent. Natural uncertainty quantification provides confidence intervals and risk assessments crucial for safety-critical applications. Unlike deterministic methods requiring separate uncertainty propagation, these approaches inherently model solution variability, capturing both aleatoric (data) and epistemic (model) uncertainty within a unified framework.

Robust handling of noisy and incomplete data reflects practical measurement scenarios. While traditional methods require complete, clean boundary conditions and initial data, probabilistic approaches naturally accommodate missing information, measurement noise, and sparse observations. The framework can infer likely solutions consistent with both physical laws and partial observations, enabling data assimilation and state estimation applications.

The ability to model multi-modal solution distributions proves valuable for problems with non-unique solutions, bifurcations, or phase transitions. Traditional methods typically find single solutions, potentially missing important alternative states. Generative models can capture and sample from complex solution manifolds, revealing the full range of possible behaviors.

Latent variable models like VAEs provide interpretable low-dimensional representations capturing essential solution features. These compressed representations enable efficient exploration of parameter spaces, sensitivity analysis, and identification of dominant modes. The continuous latent space supports interpolation between solutions and generation of new instances.

These methods provide natural frameworks for stochastic PDEs, avoiding closure approximations or Monte Carlo sampling. Direct modeling of probability distributions enables efficient computation of statistics and rare event probabilities. This principled treatment of randomness benefits applications in turbulence modeling, uncertainty propagation, and risk assessment.

7.5.3. Limitations and Challenges of Generative Models

Computational overhead represents a significant limitation, with training and inference typically requiring more resources than deterministic alternatives. Score-based methods need numerous denoising steps, VAEs require sampling during training, and normalizing flows involve expensive Jacobian computations. The computational cost can exceed traditional uncertainty quantification methods for simple problems.

Many generative approaches suffer from training complexity and instability. Balancing multiple objectives (reconstruction, regularization, PDE constraints) requires careful tuning. Mode collapse in VAEs, training instability in normalizing flows, and convergence issues in score-based methods demand expertise and extensive experimentation. The addition of PDE constraints to already complex training procedures exacerbates these challenges.

Theoretical understanding of uncertainty quality remains limited. While these methods provide uncertainty estimates, their calibration and reliability for PDE applications lack comprehensive analysis. The interaction between approximation errors, discretization effects, and probabilistic modeling can produce overconfident or poorly calibrated uncertainties. Validation requires extensive comparison with ground truth distributions, often unavailable for complex PDEs.

High-dimensional problems present severe scalability challenges. The curse of dimensionality affects all generative models, with VAEs suffering from posterior collapse, normalizing flows requiring extremely deep architectures, and score-based methods needing fine discretization of the diffusion process. Memory requirements for storing and processing distributions can also become prohibitive.

Despite probabilistic frameworks, the interpretability of learned representations may be limited. Understanding why certain solutions are assigned high probability or how physical constraints influence distributions remains challenging. The black-box nature of neural network components obscures the relationship between inputs and probabilistic outputs.

7.6. Hybrid and Multi-Physics Methods

Hybrid methods combine traditional numerical methods with machine learning, creating synergistic approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. By combining the mathematical rigor, conservation properties, and interpretability of classical methods with the flexibility, efficiency, and learning capabilities of neural networks, hybrid approaches address fundamental limitations while maintaining scientific computing standards.

7.6.1. Integration Strategies and Architectures

Neural-FEM Coupling

This approach embeds neural networks within finite element frameworks at multiple levels. At the constitutive level, neural networks replace analytical material models:

where

represents material parameters and

H denotes history variables. The element stiffness matrix becomes:

At the element level, neural networks enhance shape functions:

providing adaptive basis enrichment. Training minimizes combined FEM residuals and data mismatch.

Multiscale Neural Networks

These architectures explicitly separate scales using neural networks for scale bridging:

The macro-scale evolution follows homogenized equations with neural network closures:

where

and

are learned from fine-scale simulations.

Neural Homogenization

This method learns effective properties and closure relations for heterogeneous materials:

Training data comes from computational homogenization on representative volume elements. The approach handles nonlinear homogenization where analytical methods fail.

Multi-fidelity Networks

These combine models of varying accuracy and cost:

where

learns the correlation between fidelities and

captures the discrepancy. Hierarchical training leverages abundant low-fidelity data:

Physics-Guided Networks

These architectures incorporate physical principles directly into network design. Conservation laws are enforced through architectural constraints:

Symmetries are preserved through equivariant layers:

Energy conservation uses Hamiltonian neural networks:

7.6.2. Strengths and Advantages of Hybrid Methods

Hybrid methods bring forward the best aspects of traditional and machine learning approaches. Enhanced interpretability through integration with established numerical frameworks provides confidence in solutions and facilitates debugging. Unlike pure black-box neural networks, hybrid methods maintain clear connections to physical principles and mathematical theory, enabling validation against known solutions and physical intuition.

Leveraging both physics-based modeling and data-driven corrections improves accuracy. Traditional methods provide baseline solutions respecting conservation laws and boundary conditions, while neural networks capture complex phenomena beyond idealized models. This combination often achieves higher accuracy than either approach alone, particularly for problems with well-understood physics and complex empirical behaviors.

Computational efficiency gains arise from using neural networks to accelerate expensive components while maintaining mathematical rigor. Examples include learned preconditioners reducing iteration counts, neural network closures avoiding fine-scale simulations, and surrogate models replacing expensive constitutive evaluations. The selective application of machine learning to computational bottlenecks provides targeted acceleration.

Natural incorporation of domain knowledge through traditional formulations ensures physical consistency. Conservation laws, symmetries, and mathematical properties are exactly satisfied by design rather than approximately learned. This proves crucial for safety-critical applications where violations of physical principles are unacceptable.

The physics-based foundation ensures robustness to limited data. While pure data-driven methods may fail with sparse data, hybrid approaches leverage physical models to constrain the learning problem. The reduced reliance on data enables applications to problems where extensive datasets are unavailable.

7.6.3. Limitations and Challenges of Hybrid Methods

Implementation complexity represents the primary challenge, requiring expertise in both traditional numerical methods and machine learning. Developers must understand finite element formulations, neural network architectures, and their interaction. Software engineering challenges arise from integrating diverse libraries, managing different data structures, and ensuring efficient communication between components.

Balancing different error sources becomes complex with contributions from discretization errors, neural network approximation errors, and potential inconsistencies between components. Error analysis must consider interaction effects, making convergence studies and reliability assessment more challenging than for pure methods. The optimal balance between physics-based and data-driven components often requires extensive experimentation.

Training procedures must coordinate traditional and ML components, leading to complex optimization problems. Sequential training may lead to suboptimal solutions, while joint training faces challenges from different convergence rates and scaling. The need to maintain physical constraints during neural network updates requires specialized optimization techniques.

Theoretical analysis becomes significantly more complex than for pure approaches. Establishing stability, convergence, and error bounds requires considering the interaction between different components. The effect of neural network approximations on overall solution properties remains poorly understood for many hybrid schemes.

Software maintenance and portability challenges arise from dependencies on multiple frameworks. Keeping hybrid codes updated with evolving ML libraries while maintaining numerical stability requires ongoing effort. The specialized nature of hybrid implementations can limit code sharing and community development.

7.7. Meta-Learning and Few-Shot Methods

Meta-learning approaches address the critical challenge of rapid adaptation to new PDE problems with minimal data. By learning to learn from related problems, these methods enable efficient solution of PDE families where traditional approaches would require extensive recomputation or retraining.

7.7.1. Meta-Learning Strategies for PDEs

Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) for PDEs

MAML learns initialization parameters, enabling rapid adaptation through a few gradient steps. The bi-level optimization seeks parameters that are sensitive to task-specific updates:

For PDEs, tasks represent different parameter values, boundary conditions, or domain configurations. Implementation requires computing second-order derivatives or using first-order approximations.

Prototypical Networks for PDEs

These learn embeddings where PDE problems cluster by solution characteristics:

where

encodes problem specifications and

is the prototype for problem class

k. New problems are solved by identifying the nearest prototype and applying class-specific solvers.

Neural Processes for PDEs

These provide probabilistic predictions with uncertainty from limited context:

where

is the context set. The framework naturally handles sparse observations and provides calibrated uncertainties.

Hypernetworks for PDEs

Hypernetworks generate problem-specific parameters without optimization:

where

P encodes problem parameters. This enables instant adaptation through forward passes rather than gradient updates.

7.7.2. Advantages of Meta-Learning

Dramatic reduction in per-problem data requirements enables practical deployment where data is expensive. Adaptation from 5-10 examples compares favorably to thousands required by standard training. This efficiency proves crucial for experimental validation or real-time applications.

Systematic exploitation of problem similarities improves generalization and reduces redundant computation. Learning shared representations across problem families provides insights into underlying structures. The framework naturally supports transfer learning and continual learning scenarios.

Computational efficiency during deployment through few-shot adaptation enables real-time applications. Once meta-trained, solving new instances requires minimal computation compared to training from scratch. This supports interactive design exploration and control applications.

7.7.3. Challenges of Meta-Learning

The requirement for well-defined task distributions limits applicability. The meta-training distribution must adequately cover expected test scenarios. Poor coverage leads to catastrophic failure on out-of-distribution problems. Defining appropriate task families for PDEs requires domain expertise.

Meta-training computational costs can be substantial, requiring diverse problem instances and complex bi-level optimization. The upfront investment may not amortize for small problem families. Training instability and sensitivity to hyperparameters complicate practical implementation.

Limited theoretical understanding of generalization and adaptation capabilities creates uncertainty. The interaction between task diversity, model capacity, and adaptation performance remains unexplored. Validation requires careful experimental design to assess true few-shot capabilities versus memorization.

7.8. Physics-Enhanced Deep Surrogates (PEDS)

Physics-Enhanced Deep Surrogates represent a hybrid paradigm that combines low-fidelity physics solvers with neural network generators to achieve superior data efficiency and physical interpretability compared to black-box neural approaches [

157]. Unlike purely data-driven surrogates or physics-agnostic neural networks, PEDS leverages existing simplified physical models as foundational components, using neural networks to bridge the accuracy gap to high-fidelity solutions while maintaining computational tractability.

7.8.1. Core PEDS Framework and Mathematical Formulation

Fundamental Architecture

The PEDS framework operates on a three-component architecture: a neural network generator , a low-fidelity physics solver , and a high-fidelity reference solver . Given input parameters p describing the physical system (geometry, boundary conditions, material properties), the methodology proceeds as follows:

The neural network generator produces a coarsened representation of the input: