Introduction

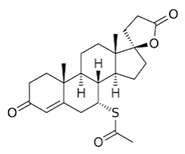

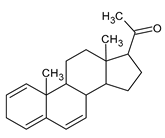

An anti-androgen is a compound that blocks the androgen receptors. 5 alpha reductase inhibitors cannot be considered as anti-androgens: e.g., even blocking 5aR would leave testosterone available to act on AR. Steroids are biomolecules with a basic structure made up of cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene [

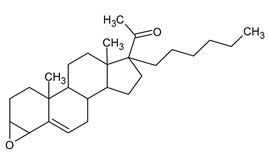

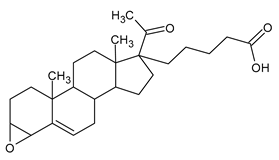

1]. Two steroids derived from cholesterol are testosterone (

Figure 1), as natural androgen, and progesterone (

Figure 2), as natural antiandrogen [

2]. Tradicionally finasteride and dutasteride, the two synthetic inhibitors used in clinics, as well, epigallo catechin gallate as a natural inhibitor of 5aR.

Antiandrogens or androgen antagonists alter the androgen pathway by blocking the appropriate receptors, competing for binding sites on the cell surface or affecting androgen production [

3]. Endogenous sex hormones may differentially modulate glycemic status and it is associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes [

4]. However, reactive oxygen species (ROS) may act as a metabolic signal-mediating responses to changes in glucose and hormones [

5]. Low levels of circulating androgens should be considered as a significant risk factor for the development of neurodegenerative disorders [

6]. In this regard, numerous neurotransmitters have been implicated in the pathogenesis of these disorders, with dopamine and serotonin playing a crucial role in the neural reward pathways [

7].

Antiandrogens can be prescribed to treat an array of diseases and disorders as gender dysphoria. In men, antiandrogens are most frequently used to treat prostate hyperplasia and cancer [

8]. In many tissues sulfonated steroids exceed the concentration of free steroids. Recently, these sulfonated steroids were also shown to fulfill important physiological functions. It was suggested that cholesterol sulfate (CS) is converted by CYP11A1 to pregnenolone sulfate (PregS), which is metabolized to 17OH-PregS; thus, strengthening the potential physiological meaning of a pathway for sulfonated steroids [

9].

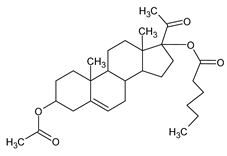

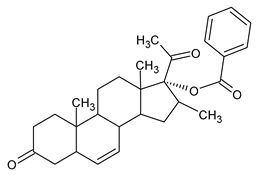

Antiandrogens present in the environment have become a topic of concern. Certain plant species have also been found to produce antiandrogens as dehydropregnenolone acetate (

Figure 3), and inhibit circulating androgens by blocking androgen receptors, suppressing androgen synthesis, or acting in both ways [

10].

Target Cell Action

The most common antiandrogens are androgen receptor (AR) antagonists, which act on the target cell level and competitively bind to androgen receptors [

11]. Antiandrogenic drugs are used for hormone therapy. This therapy is called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). The main goal of ADT is to produce a state of competition between them and the circulating androgens for binding sites on prostate cell receptors. In this way, they can inhibit prostate cancer growth and promote their apoptosis [

12]. Antiandrogen monotherapy generally causes fewer side effects in males; however, they are less effective in blocking androgen when compared with combined therapies. Monotherapy is often preferred by men as it is less likely to diminish libido than combined therapies [

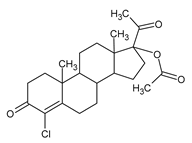

13]. In fact, antiandrogens are 5α-reductase inhibitors and prevent the conversion of testosterone to DHT [

14], by directly binding on hydrogen in C-5 (

Figure 4).

DHT is 3-5 times more potent than testosterone or other androgens. They are unique because they do not counteract the effects or production of other androgens other than DHT. Dihydrotestosterone is necessary for development of both external male sex organs and the prostate [

15].

However, 5α-reductase enzyme has several isoforms and is expressed in various tissues as well as in the epithelium and myelin [

16]. Therefore, the circulating and intraprostatic DHT could be further reduced by a more effective dual 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor, which would be efficacious in the treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia and other DHT-related disorders, as gender dysphoria. Antiandrogens act by various mechanisms to decrease the production or effects of testosterone, but it is unclear which antiandrogen is most effective at feminization [

17], although, Spironolactone is commonly used in feminizing hormone therapy to achieve the goal of female range testosterone level [

18].

A peptide antagonist interrupts androgen receptor protein interaction from the surface of the receptor. This approach is mechanism-based and has greater potential for blocking receptor activity than the traditional ligand-receptor binding approach [

19].

Developing Novel Antiandrogen

On the other hand, some studies suggest that the modification of steroid B-ring or D-ring and lateral chain play an important role for the hormonal therapy [

20]. There is much interest in developing chemical novel antiandrogen drugs that may help to prevent or ameliorate these clinical disorders; thus, suggesting the introduction of aromatic or aliphatic structures in steroid B-ring and D-ring [

21].

Methods

The present study has the aim of pharmacological evaluation of several new steroid derivatives that were prepared from the commercially available 16-dehydropregnenolone acetate. The biological activity of the new steroidal derivatives was determined. The neuroprotection effect of the steroids was demostrated using the biomarkers of oxidative stress on male rat brain and liver with hypoglycemia induced.

Results and Discusion

Enzyme kinetics was demostrated by the inhibition of 5α-reductase enzyme on myelin of brain. This study suggest that steroid 12 derivatives with an electrophilic center can interact more efficiently with the 5α-reductase enzyme and then induce neuroprotection in hypoglycemia animal model. Further research with clinically meaningful endpoints is needed to optimize the use of antiandrogens in these hormonal therapies.

Table 1.

Novel synthetic steroidal structures and in vitro result assessments.

The complete data of this study showed very clearly that all compounds are good inhibitors for the 5alpha-reductase enzyme. Probing the efficacy of these novel steroids with respect to spironolactone in vitro assay, appears that they would be promising compounds for future hormonal therapy in patients

Conclusion

The future of antiandrogenic steroid drugs is believed to be antagonists due mainly to cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene structure. Androgen receptor antagonists act in an alternative manner and this may be one of the mechanisms underlying the benefits of these drugs. In addition, this response between antiandrogens and clinical disorders is expected in adult people. In general, the analysis of novel synthetic steroid suggests that it is favorable to insert aromatic or ester-aliphatic groups in ring D, chloride in ring B, and aliphatic group with carbonyl in ring A. The aromatic groups inserted in ring D, activated 5α-reductase enzyme. These antioxidant molecules provide the scientific basis to design clinical trials aimed at reducing the oxidative stress, and probably the CNS changes elicited by hormonal therapy in patients. This is important when we consider that it is still unclear which antiandrogen is most effective at achieving feminization. However, there are insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy or safety of hormonal treatment approaches for transgender women in transition, or prostate cancer. Hence, further research with clinically meaningful endpoints is needed to optimize the use of antiandrogens in these hormonal therapies.

Authors' Contributions

DCG, NOB, MOH, AVP, RSP, VMDG, HJO, ARO. All them made 1. Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; 2. Drafting the article or substantively contributing to revisions in intellectual content; 3. Final approval of the version to be published; and 4. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Authors' information: All participating authors are qualified medical science researcher recognized by the Health Ministry of Mexico.

Funding

This article received no kind of economical support

Availability of Data

Any data used in this study are available on request to the correspondence author.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Cyril Ndidi Nwoye Nnamezie, an expert translator and native English speaker, a researcher in Medical Science and a physician by profession. The authors express their profound gratitude to the National Institute of Pediatrics [NIP] for the support in the publication of this article issued on the Program A022.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Robel, E.; Baulieu, E.E. Neurosteroids: biosynthesis and function. Trends Endocrinol Metab 1994, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, G.D.; Barragán, M.G.; Espitia, V.I.; Hernández, G.E.; Santamaría, A.D.; Juárez, O.H. Effect of testosterone and steroids homologues on indolamines and lipid peroxidation in rat brain. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2005, 94, 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Mowszowicz, I. Antiandrogens. Mechanisms and paradoxical effects. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 1989, 50, 189–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ding, E.L.; Yiqing Song. ; Vasanti Malik, S.; Simin Liu. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2006, 295, 1288–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markkula, P.S.; Lyons, D.; Chen-Yu Yueh. ; Riches, C.; Hurst, P.; Barbara Fielding. et al. Intracerebroventricular Catalase Reduces Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity and Increases Responses to Hypoglycemia in Rats. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 4669–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, K.O.; Khaidarova, R.R.; Khabibullina, R.H.; Stytsenko, E.S.; Filosofova, V.I.; Nuriakhmetova, I.R.; et al. , Testosterone and Alzheimer's disease. Probl Endokrinol (Mosk) 2022, 68, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muna Asiff; Hatta Sidi; Ruziana Masiran; Jaya Kumar; Srijit Das; Nurul Hazwani Hatta, et al, Hypersexuality As a Neuropsychiatric Disorder: The Neurobiology and Treatment Options. Curr Drug Targets 2018, 19, 1391–1401. [CrossRef]

- Gillatt, D. Antiandrogen treatments in locally advanced prostate cancer: are they all the same? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2006, 1, S17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neunzig, J.; Sánchez-Guijo, A.; Mosa, A.; Hartmann, M.F.; Geyer, J.; Wudy, S.A.; et al. A steroidogenic pathway for sulfonated steroids: The metabolism of pregnenolone sulfate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Rabe, T. Hormonal antiandrogens in acne treatment. J German Soc Dermatol 2010, 8 (Suppl 1), S60–74. [Google Scholar]

- Witjes, F.J. , Debruyne, F.M.; Fernandez del Moral, P.; Geboers, A.D. Ketoconazole high dose in management of hormonally pretreated patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Dutch South-Eastern Urological Cooperative Group. Urology 1989, 33, 411–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albany, C.; Hahn, N.M. Heat shock and other apoptosis-related proteins as therapeutic targets in prostate cancer. Asian J Androl 2014, 16, 359–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kolvenbag, G.J.; Iversen, P.; Newling, D.W. Antiandrogen monotherapy: a new form of treatment for patients with prostate cancer. Urology 2001, 58, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, E.; Bratoeff, E.; Cabeza, M.; Ramirez, E.; Quiroz, A.; Heuze, I. Steroid 5alpha-reductase inhibitors. Mini-Rev Med Chem 2003, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Kang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xie, G.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Effects of dihydrotestosterone on synaptic plasticity of hippocampus in male SAMP8 mice. Exp Gerontol 2013, 48, 778–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agis-Balboa, R.C.; Guidotti, A.; Pinna, G. 5α-reductase type I expression is downregulated in the prefrontal cortex/Brodmann's area 9 (BA9) of depressed patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014, 231, 3569–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachlan Angus, M.; Brendan Nolan, J.; Jeffrey Zajac, D.; Ada Cheung, S. A systematic review of antiandrogens and feminization in transgender women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2021, 94, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supanat Burinkul; Krasean Panyakhamlerd; Ammarin Suwan; Punkavee Tuntiviriyapun; Sorawit Wainipitapong. Anti-Androgenic Effects Comparison Between Cyproterone Acetate and Spironolactone in Transgender Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Sex Med 2021, 18, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Margaill, I.; Zhang, S.; Labombarda, F.; Coqueran, B.; Delespierre, B.; et al. , Progesterone receptors: a key for neuroprotection in experimental stroke. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3747–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaili, J.; Boisvert, M.; Longpré, F.; Carange, J.; Le Gall, C.; Martinoli, M.G.; et al. Brassinosteroids and analogs as neuroprotectors: synthesis and structure-activity relationships. Steroids 2012, 77, 91–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, D.C. , Bratoeff, E.; Riveros, A.C.; Brizuela, N.O. Mejia, G.B.; Olguin, H.J. et al. Effect of two antiandrogens as protectors of prostate and brain in a Huntington's animal model. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2014, 14, 1293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).