1. Introduction

Tourism is a significant global industry, with substantial economic benefits, that drive increased production, income, and employment [

1,

2,

3]. However, its environmental impact, is more evident in the hotel sector, which contribute approximately 21% of the overall ecological footprint of the tourism and hospitality industry, due to high energy use, water consumption, and waste generation [

4,

5,

6]. The situation is more acute in the global south where recycling, extended producer responsibility systems, and attempt to reuse plastic waste have largely fallen flat due to a shortage of policy resources or capacity. This has made effective solid waste management critical, both for preserving natural resources and promoting sustainable practices [

6,

7,

8,

9].

In Zanzibar, tourism is not only an economic pillar but also a vital lifeline, contributing around 28% to the island’s GDP and 82% to its foreign exchange earnings [

8,

9]. The tourism sector in Zanzibar is growing at an annual rate of 15%, placing increasing pressure on local waste management systems as waste generation rises sharply [

10,

11,

12,

13]. What was once predominantly organic waste has now been shadowed by plastics and hazardous materials posing significant environmental risks. The convenience driven nature of the tourist and hotel industry fuel this shift, as single use plastics like water bottle, food wrapper and bags become widespread. This increase in plastic waste places immense strain on Zanzibar’s waste management infrastructure and threatens the island’s natural beauty by littering beaches and polluting coastal ecosystems. It also endangers marine life through ingestion, entanglement, habitat disruption, and the spread of toxic micro plastics in the food chain [

16]. Additionally, the accumulation of plastic waste leads to health risks, such as providing breeding grounds for disease vectors in discarded plastic bottles and containers [

17].

To safeguard Zanzibar's environmental integrity and ensure the long-term sustainability of its tourism sector, a systematic reform in waste management is essential. This reform must include a critical re-evaluation and redefinition of both the tourism and waste management value chains, while integrating innovative, evidence-based practices and methodologies for waste management [

15,

16]. The formulation of integrated, Eco-innovative strategies is vital to mitigate environmental degradation, with a particular emphasis on developing a multi-faceted, stakeholder-inclusive framework for effective policy-making in waste management [

15,

16,

18].

Community engagement is a key to effective waste management, especially in places where formal system is lacking [

17]. When local people are actively involved through clean-up efforts, sorting waste or running small recycling projects, waste is handled more efficiently and sustainably [

14,

18]. In many African communities, women and youth often lead these efforts, bringing the gaps between communities and and authorities [

17,

19]. By involving communities as real partners, not just recipient of services, waste solutions become more practical, inclusive and long lasting. Studies have demonstrated that active participation of local communities enhances waste collection efficient, foster local ownership, and encourage behavioral change toward more sustainable solutions [

19].

A number of studies has shown that women's participation in waste prevention is a key component of fostering equitable and socially inclusive solutions, ensuring that all segments of the population are involved in and benefit from these initiatives [

15,

16]. Moreover, strategies that prioritize waste reduction, along with those that enhance opportunities for reuse, recycling, and responsible disposal, which form the cornerstone of the transition toward a circular economy. are mostly done by women. The European Union's Horizon 2020 Urban Waste project highlights the importance of circular economy principles in waste management, demonstrating that targeted strategies can drive significant improvements in waste reduction and resource efficiency[

15].

Further evidence supporting these approaches comes from Kibria and Doukali (2023), who emphasized the potential of leveraging young entrepreneurship and innovation to enhance circular economy practices and waste management[

14,

18]. They argue that fostering entrepreneurial solutions in waste management not only promotes economic growth but also catalyses the adoption of sustainable waste management practices. The implementation of these strategies, reinforced by robust policy frameworks, can help reduce the ecological footprint of Zanzibar’s tourism sector while promoting sustainable resource management practices [

16].

Tourism-related waste in Zanzibar averages 1.5–2 kg per tourist per day, which is three to four times higher than the local waste generation rate [

17]. A substantial portion of this waste consists of single-use plastics and everyday toiletries. However, there is currently no systematic strategy in place for waste segregation, and comprehensive data on plastic waste generation and disposal practices are lacking [16.17]. Consequently, plastic litter has become widespread across beaches, seas, roadsides, and other natural areas, with significant environmental and economic consequences [

16,

18]. Further complicating the issue are factors such as insufficient technical skills, inadequate recycling infrastructure, a low level of public awareness, and poor enforcement of regulations, including the tendency for indiscriminate dumping [

14,

16,

17,

20,

21].

Previous studies suggest that strategies focused on reducing environmental impact through reduction, reuse, and recycling of plastics are effective in addressing the global plastic waste crisis [

18,

22]. Strategies such as reducing single-use plastics, collaborating with manufacturers to minimize packaging or paying for the waste they produce (EPR schemes), and enhancing recycling have been shown to reduce plastic waste and ease pressures on collection and landfill systems [

22,

24].

In Zanzibar, innovative community driven initiatives are emerging as frontiers of sustainable plastic waste management. Organizations like the Zanzibar Scraps and Environment Association (ZASEA) is actively engaging communities in plastic collection and recycling, while social enterprises such as CHAKO, Zanzibar, in partnership with the TUI Care Foundation, are pioneering creative up-cycling models that empower women and youth by transforming waste into valuable products. Recycling at OZTI stands at the forefront of HDPE recycling, integrating social enterprise with education and skills development to build local capacity. Complementing these efforts, the Zanzibar Youth Education, Environment, Development Support Association (ZAYEDESA), and KAWA Initiatives mobilize schools, youth, and women’s groups to foster environmental stewardship and practical waste solutions, particularly in tourism hot-spots. Informal reuse practices, such as repurpose PET bottles for household needs, highlight a deep-rooted culture of resourcefulness, offering untapped potential for scaling sustainable waste solutions. Together, these initiatives chart a promising path toward resilient, community centered plastic waste management in Zanzibar’s coastal regions (Unpublished NGO data, Zanzibar, 2023).

Despite increasing research on plastic waste management in the Global South, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies examining the intersection of tourism, waste generation, and community-driven sustainability strategies in island nations such as Zanzibar[

16,

17]. Previous research has highlighted the effectiveness of strategies focused on reducing, reusing, and recycling plastics in addressing the global plastic waste crisis. Kibria, Masuk, and Safayet [

18] conducted a comprehensive study exploring the challenges and opportunities associated with mitigating plastic pollution and improving waste management in various global contexts. Their findings underscore the significant environmental and health risks posed by plastic waste, particularly in regions with underdeveloped waste management systems. The authors advocate for comprehensive waste management strategies that integrate waste reduction, recycling, and the adoption of alternative materials, while emphasizing the need for infrastructure improvements, public awareness, and community engagement to enhance waste management effectiveness. Furthermore, the study highlights the potential of technological innovations and policy interventions to address the plastic waste challenge more effectively.

Similarly, Jacobsen, Pedersen, and Thøgersen [

22] conducted a systematic literature review to examine the drivers and barriers to plastic packaging waste avoidance and recycling [

23]. Their analysis identified key factors influencing consumer behaviour, including cultural, economic, and policy-related variables, which significantly impact the success of waste reduction and recycling initiatives. The review also emphasizes the importance of collaboration between policymakers, business, and consumers to establish a circular economy model that encourages both consumer participation and industry-wide commitment to sustainable practices.

Number of studies have shown that community-driven local strategies are essential in addressing plastic waste challenges in regions with high tourism activity [

25,

26,

28,

29]. In Zanzibar, tackling plastic waste requires a holistic, integrated strategy that considers the social, economic, institutional, technical, and environmental aspects of waste management. Community participation plays a critical role in fostering a sense of responsibility and encouraging sustainable practices [

29,

32]. Effective waste management is not only a public health necessity but also presents opportunities for energy recovery and material recycling, which can benefit local communities economically and environmentally [

30,

31,

33]. This study aims to explore these opportunities in Zanzibar's context, while also providing valuable insights for other tourism-dependent destinations globally.

Zanzibar’s current waste management system relies heavily on a linear model of generating, collecting, and disposing of waste, which is increasingly unsustainable as the volume of plastic waste continues to rise. This approach contributes to environmental degradation and public health concerns. As a result, there is growing influence for integrating circular economy principles into waste management systems to foster sustainability [23,27&28]. Emerging technologies, such as biodegradable plastics, advanced recycling processes, and waste-to-energy solutions, offer new avenues for tackling waste challenges that could complement existing efforts in Zanzibar.

To support this transition, the Zanzibar Commission for Tourism (ZCT) launched the Zanzibar Declaration for Sustainable Tourism in 2023, an initiative that encourages the tourism industry to adopt sustainable practices that benefit people, the planet, and the economy. This declaration emphasizes the importance of waste reduction and resource efficiency, highlighting the need for enhanced plastic waste recovery and recycling. By focusing on effective waste management and ecosystem restoration, Zanzibar can transition toward responsible tourism and improve its environmental sustainability. These efforts align with global sustainability initiatives, positioning Zanzibar as a potential leader in responsible tourism practices.

As part of Zanzibar’s commitment to sustainable tourism, this research explores ways to balance tourism growth with socioeconomic development and environmental protection. The findings of this study aim to contribute to the development of more effective waste management policies, ensuring that both the environment and the tourism industry can thrive in the future. By examining Zanzibar’s waste management practices, this research will highlight innovative and scale-able solutions that can be adopted by other tourist destinations facing similar challenges.

As tourism continues to thrive, the effective management of plastic waste has become an increasingly urgent challenge. Although research on plastic waste management in the Global South is growing, there remains a significant gap in studies that examine the intersection of tourism, waste generation, and community-driven sustainability strategies, particularly in island nations such as Zanzibar.

This study investigates innovative and context-specific approaches for managing plastic waste in Zanzibar’s rapidly expanding tourism sector, with the goal of aligning local practices with global sustainability frameworks. It emphasizes the integration of innovative solutions and active community participation, addressing the social, economic, institutional, technical, and environmental dimensions of plastic waste management.

By adopting a holistic perspective, this research aims to generate actionable recommendations for a range of stakeholders, including local government authorities, community leaders, and environmental organizations. The findings seek to contribute to the sustainable development of Zanzibar by offering practical guidance that supports existing initiatives such as the Zanzibar Declaration on Sustainable Tourism and the Greener Zanzibar Campaign, both of which advocate for environmentally responsible tourism. In doing so, this study aims to advance waste reduction efforts and promote eco-friendly practices across the tourism value chain.

3. Results

3.1. Particicipants Profile by Age Group and Gender

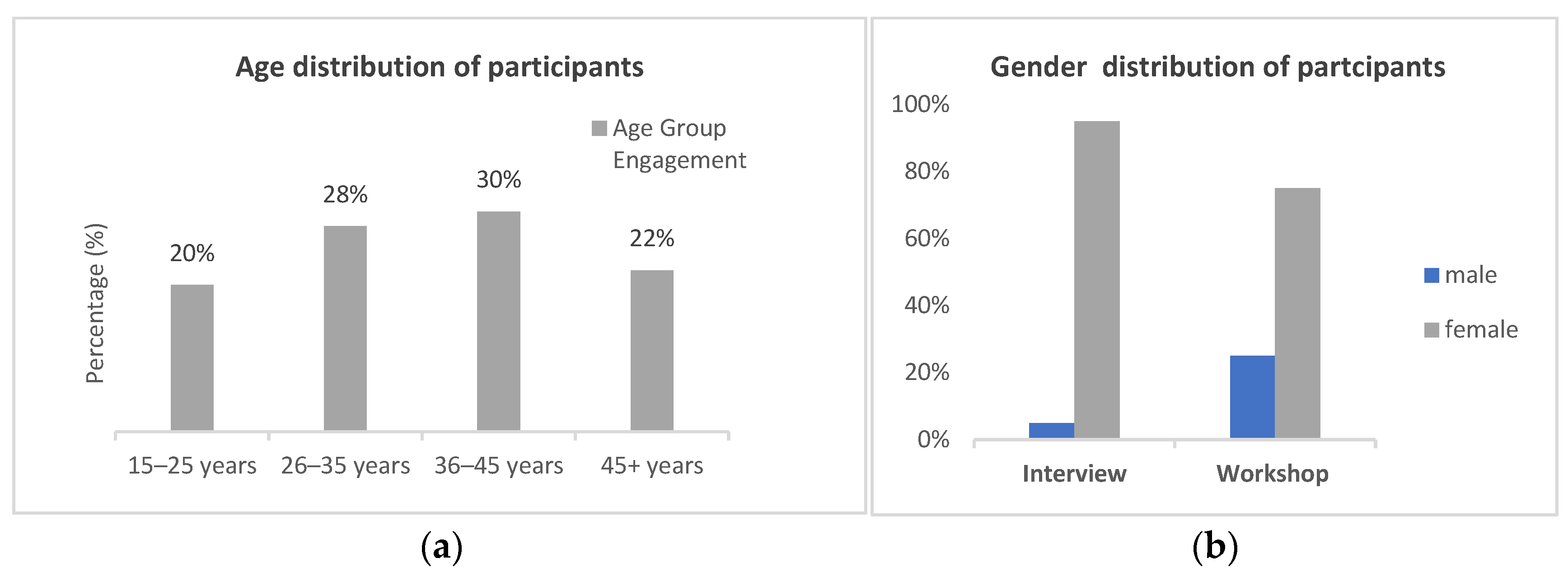

Findings from community interviews reflected a fairly balanced age distribution among participants, with 20% aged 15–25, 28% aged 26–35, 30% aged 36–45, and 22% aged 45 and above. Female representation was strong across all age groups, making up 95% of interviewees and 75% of workshop participants.

Figure 2.

a: Particicipants distribution by age group. 2b: Participants distribtion by gender.

Figure 2.

a: Particicipants distribution by age group. 2b: Participants distribtion by gender.

3.2. Type of Plastic Waste in the Communities

The predominant type of plastic waste observed in the study communities is single-use Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) bottles, primarily used for packaging mineral water and beverages. Based on field observations and interviews, a significant proportion of these PET bottles is sourced from hotels, where they are often passed on to adjacent communities for reuse or repurposing. PET bottles are reused within the local communities as containers for liquids such as cooking oil, water, milk, honey, and soap, or to store dry products like tea bags, curry powders, and spices and end up being dumped. These findings reflect the affordability and convenience of PET bottles, which, while contributing to reduced waste in the short term, do not address the broader systemic issues related to plastic waste. High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) plastics were identified as the second most generated plastic waste type in the region, particularly used in packaging materials (field observation).

Figure 3.

Plastic waste accumulation on Kendwa beach (Source:Property common.

Figure 3.

Plastic waste accumulation on Kendwa beach (Source:Property common.

Figure 4.

Hotel waste improperly disposed in nature at Nungwi (Source: ZANREC).

Figure 4.

Hotel waste improperly disposed in nature at Nungwi (Source: ZANREC).

3.3. Waste Collection and Transportation Systems in the Study Area

In rural coastal areas like Kendwa, Nungwi, Jambiani, Paje, and Michamvi, district councils are responsible for waste collection and disposal. Larger hotels generally manage their waste through contracts with private contractors hired by the councils who transport it to the designated landfill in Kibele. However, a clear gap exists once waste enters the community. Many smaller hotels, restaurants, and households lack access to formal waste services and often depend on informal collectors or dispose of waste at nearby points without proper oversight.

Figure 5.

Uncovered truck transporting waste from Michamvi to the disposal site (Soure:researcher).

Figure 5.

Uncovered truck transporting waste from Michamvi to the disposal site (Soure:researcher).

Figure 6.

Disposal of waste at the nearby collection point in Paje (Soure:researcher).

Figure 6.

Disposal of waste at the nearby collection point in Paje (Soure:researcher).

Even with formal contracts in place, field observations reveal that waste collection trucks often operate

uncovered and carry mixed waste, which undermines efforts to separate recyclables and manage waste responsibly. Additionally, local waste collectors, frustrated by long distances to dumpsites and inadequate logistical support, sometimes resort to open or illegal dumping. This disconnection between formal waste management at larger hotels and informal community-level practices presents significant challenges for effective waste control in these coastal villages.

Interviews with contractors suggest that insufficient compensation for transportation costs to official dumpsites exacerbates inefficiencies, prompting some to turn to informal dumping methods. This occurs because transporting waste to official sites is considered cost-ineffective. District councils, responsible for overseeing waste collection from hotels, set collection fees based on the size of the hotel. As a result, hotel owners face higher costs, yet they often negotiate these fees, compelling waste collection companies to bypass regulations and exploit loopholes.

3.4. Waste Recovery, Reuse, and Treatment Practices

Field observations identified several common practices for managing plastic waste, including open burning, reuse, disposal in pits, indiscriminate dumping in backyards, and open dumping (

Figure 4). However, there are emerging efforts, particularly in Nungwi and Kendwa, where community groups collect discarded plastics to transform them into handcrafted items, and children collect plastic and exchange them for valuable material through the swop-shops supported by a professional waste management company.

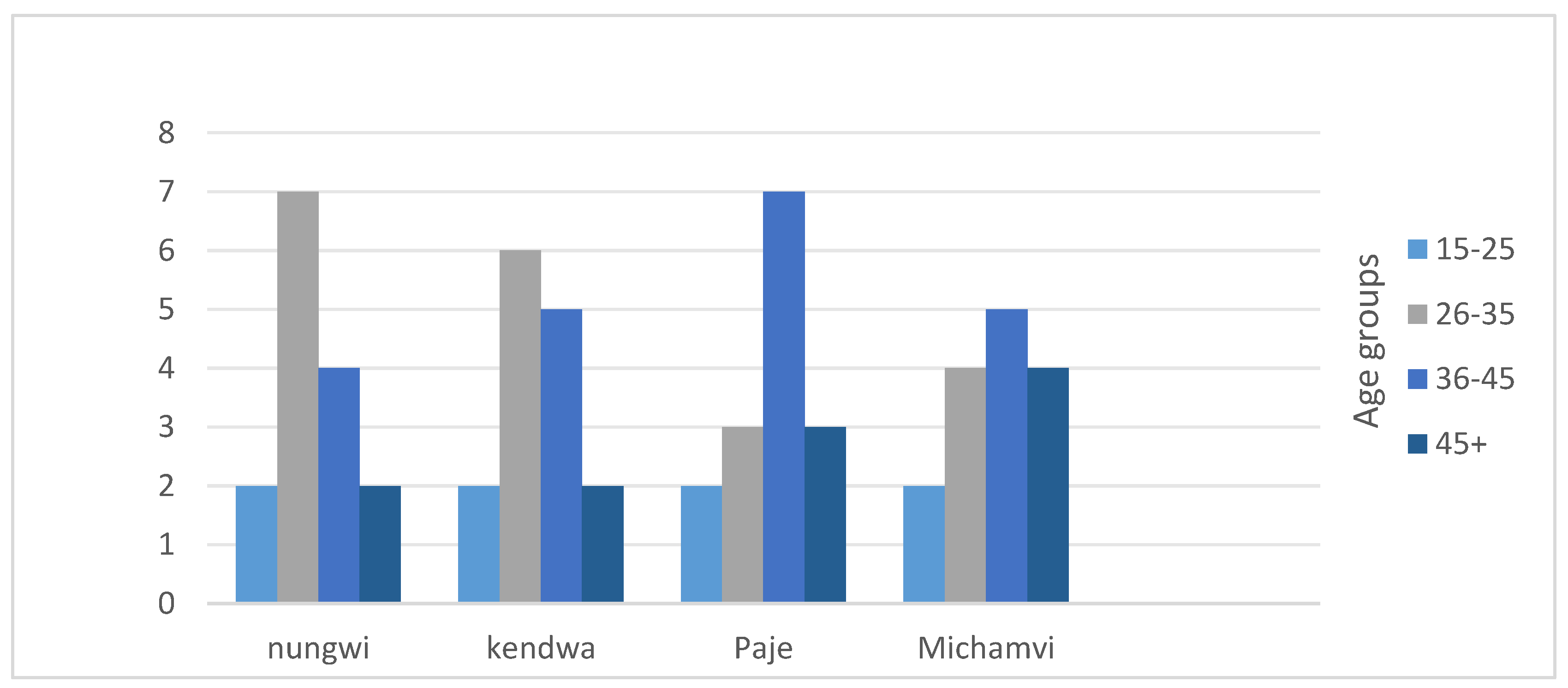

3.5. Community Participation Across Locations and Age Groups

Patterns of engagement across the study sites showed some geographic variation. In Nungwi and Kendwa, the most active groups were young adults aged 26–35 and adults aged 36–45, aligning with the overall age profile of the sample. In Paje, engagement was highest among adults aged 36–45, followed closely by older adults aged 45 and above, suggesting a stronger role of senior community members in local waste initiatives. By contrast, Michamvi showed generally low and uneven participation across all age groups, with especially limited involvement from youth aged 15–25. These variations highlight how age and location influence participation dynamics, underscoring the need for tailored engagement strategies that reflect local demographic realities.

Figure 7.

Community Engagement in Plastic Waste Collection and Recycling across communities.

Figure 7.

Community Engagement in Plastic Waste Collection and Recycling across communities.

Observations based on a structured checklist revealed clear differences in how plastic collection and recycling efforts were taking shape across the four study villages (

Table 1).

In Nungwi, plastic waste management appeared to be deeply embedded in daily routines, supported by a strong presence of NGOs and proactive involvement from the district council. Community-led initiatives were also highly visible and frequent. Kendwa also showed a high level of activity, where swop-shops, partnerships between hotels and local communities, and youth-driven education efforts all of which highly contributed to an active waste management culture. Paje reflected a more moderate level of engagement, with occasional clean-up events, school involvement, and some support from swop-shops. Meanwhile, Michamvi stood out for its limited activity there were no visible recycling programs or community incentives, and little evidence of infrastructure to support organized plastic collection. This initiative, while promising, is limited to specific areas, and neighboring communities lack access to similar services, highlighting disparities in waste management practices across the communities.

3.6. Disposal and Final Treatment Methods

Few environmentally conscious hotels in the study area are working alongside local communities and environmental initiatives to tackle the growing issue of plastic waste. These hotels collaborate with organizations such as Chako Zanzibar, Kawa Environmental Club, Recycle at OZTI, and Zanrec to implement sustainable waste management practices. Chako, Zanzibar focuses on waste sorting, turning waste into art, raising awareness, spreading knowledge, and promoting female empowerment through its programs. Kawa Environmental Club organizes community clean-ups and educational initiatives to foster a deeper understanding of waste reduction. Recycle at OZTI collects plastic waste from hotels and neighboring communities for recycling, while Zanrec plays a key role in managing and processing waste, providing waste collection and recycling services. While these efforts are valuable, challenges remain, including community perception on plastic waste, limited space for sorting and recycling infrastructure and inadequate waste management systems.

In the interviews many respondents expressed the view that plastic waste is simply something to be collected and taken to landfills. One middle-aged woman reflected on this mindset, noting that “We need to rethink our mindset of plastic and find better ways to manage it”. Other commented. It's somehow disappointing. Instead of benefiting from hotel investments, we witness improper hotel waste management". Emphasizing a similar view, a young woman added,"Waste is waste as far as it is not needed anymore, regardless it's plastic or else". The best option is to do away with it." Another participant expressed frustration, saying, "I wonder what the district is doing. The hoteliers pay for the waste to be properly collected, why should it be us doing it?"

In response to such concerns, the CEO of ZANREC explained that “the company has taken proactive steps by setting up collection points in various locations where locals can exchange plastic waste for school items such as books, uniforms, and school bags, thereby fostering community participation in waste reduction while addressing local needs.” However, this approach has drawn criticism from some community members. These contrasting views underscore the complexities and challenges in promoting effective waste management strategies that are both sustainable and inclusive of community needs and concerns.

3.7. Challenges and Opportunities in Managing Plastic Waste in the Study Area; Insight from Participatory Workshop

Key challenges observed include weak strategic planning, insufficient recycling facilities, and logistical and operational barriers such as inadequate infrastructure and high transportation costs, particularly for long-distance routes from Michamvi and Paje to the Kibele dumpsite or recycling firms most of which are located in urban region. As one waste management personnel remarked, "We would like to establish a recycling facility nearby, but we lack a suitable location. Despite several discussions with district officials, they don’t seem to support our idea."

In line with this view, a young entrepreneur in her thirties added, "If municipalities and district councils could facilitate relationships among different stakeholders in waste management, plastic waste issues could be significantly reduced. Despite the challenges identified, significant opportunities exist within the growing ecosystem of local solutions, as outlined earlier in the introduction, demonstrating the potential for more sustainable and community-driven plastic waste management.

3.8. Insights from Participatory Workshops

During participatory workshops, several key themes emerged regarding strategies to enhance local waste management. First, the importance of community education was strongly emphasized. Educating communities to promote sustainable waste practices and forming partnerships with local businesses and NGOs were viewed as critical to increasing recycling and up-cycling rates. Approximately 20% of workshop participants highlighted that empowering residents through community-led initiatives could substantially improve local waste management outcomes. Participants also underscored the need for targeted incentives to encourage businesses to adopt sustainable practices and invest in recycling technologies. In this regard, several specific recommendations were proposed:

3.8.1. Establishment of Training Programs for the Waste Management Workforce

Participants recommended that district councils should partner with existing waste initiatives Zanzibar by drawing inspiration on the UNICEF–UNDP WasteX Lab model at the State University of Zanzibar (SUZA), which offers infrastructure, mentor-ship, and a circular economy curriculum to strengthen the existing initiatives within the areas. This approach was considered promising for supporting locally adapted training for waste collectors, informal workers, and council staff especially in under-served areas like Michamvi and Paje, to improve skills in plastic waste sorting, and small-scale recycling.

3.8.2. Enhancement of Public Awareness Campaigns

Drawing on initiatives led by existing recycling efforts like Recycle at OZTI, Kawa, and Chako, and Zanre participants recommended replicating these models across Unguja and rural communities. They emphasized investing in Swahili radio, village meetings, and school curricula to effectively communicate the importance of plastic segregation and proper disposal.

3.8.3. Investment in Local Technologies

Support for small-scale recycling and up-cycling units was seen as vital for reducing waste and creating value from recycled materials. In Zanzibar, initiatives like Chako involve communities in collecting and transforming plastic waste into handcrafted products, providing both environmental and economic benefits. Similarly, the Destination Zero Waste project by the TUI Care Foundation establishes small recycling hubs that train local entrepreneurs to upcycle plastic into marketable goods. Scaling such models through collaboration with local authorities and NGOs was earmarked as a crucial platform for reducing waste and creating economic opportunities within local communities.

3.8.4. Promotion of Eco-Friendly Packaging Solutions

Participants recommended using local materials such as banana leaves, palm fronds, and cassava starch to develop biodegradable packaging. In Zanzibar, banana leaves are already used informally and could be scaled for wider use. The participants cited similar approaches in Thailand and Vietnam where supermarkets adopt banana leaf packaging, while innovations from India have extended the durability of such materials for commercial use. Adapting these models locally, particularly within food markets, street vending, and hotel supply chains, was linked to the reduction of plastic waste, support green entrepreneurship, and align with Zanzibar’s sustainable tourism goals.

3.8.5. Implementation of Low-Cost Waste Sorting Machines

Participants recognized low cost waste sorting machines as effective tools for improving segregation efficiency and enabling the separation of recyclable plastics from other waste types. They proposed that in Zanzibar, such machines could be introduced at community-level or informal collection centers to reduce contamination and increase recycling rates. Using innovation hubs at technical institutions such as the Karume Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) and the Institute of Tourism at SUZA, locally appropriate prototypes could be designed, made-up, and piloted. Drawing from successful examples in Kenya and India, where manual sorters have enhanced small-scale waste recovery, participants emphasized the potential for replicating similar technologies in areas like Michamvi and Paje.

3.8.6. Development of Mobile Messaging Platforms or Apps

Participants suggested utilizing existing digital platforms and services provided by major telecom companies such as Tigo, Mixx by Yas, Halotel, Airtel and other locally available mobile network operators to promote waste segregation and recycling. They reported that these platforms could be effective in disseminating timely information on waste collection schedules, recycling points, and recyclable materials. Additionally, participants noted that such platforms have the potential to encourage responsible consumer behavior and foster a culture of sustainability.

A recurring theme among participants was the critical role of waste sorting. It was widely agreed that sorting waste constitutes a vital first step towards sustainable waste management, even in areas lacking formal recycling infrastructure. Sorting was acknowledged as a means to reduce landfill burden, conserve resources, and lay the foundation for future waste management and recycling initiatives. Supporting this view, studies from other contexts have demonstrated that although sorting may not lead to immediate recycling due to infrastructural constraints, it remains an indispensable precursor that facilitates the eventual development of local recycling industries by ensuring that recyclable materials are efficiently processed once suitable facilities are available (18).

Given the insights above, there is an urgent need to establish closed loop, community-driven circular economy model(s) to reduce pollution and create income-generating opportunities. This study proposes an establishment of a hybrid waste bank model to be integrated with existing swop shops, supported by capacity-building initiatives to enable recycling or up-cycling of sorted waste. Waste banks have emerged as an effective community-based solution for enhancing municipal solid waste (MSW) management through recycling, and their integration with local initiatives can further strengthen environmental and economic outcomes[

34]

Waste bank programs have proven effective in improving waste management and increasing community engagement in low and middle-income countries. These systems allow people to deposit sorted recyclable waste in exchange for money or savings, promoting both environmental responsibility and economic benefits. In Tanga City, Tanzania, the Waste Banks project, led by the Taka Ni Ajira Foundation and the UNDP Accelerator Lab, supports marginalized waste pickers and promotes a circular economy through digital tools and social incentives [

35]. In Lagos, Nigeria, Wecyclers collects recyclables from households using low-cost cargo bicycles, and residents earn points redeemable for goods and services, increasing recycling participation [

36]. In Cairo, Egypt, the Zabbaleen community operates decentralized waste banks, recycling up to 80% of waste and creating up-cycled products, providing income and improving local waste management [

37]. In Indonesia, the Bank Sampah system encourages residents to separate recyclables and deposit them at local waste banks, with transactions recorded in customer accounts or lists maintained by the banks [

38]. In Thailand, school-based waste bank initiatives have successfully changed recycling habits, engaging students and communities to ensure long-term participation [

39]. These examples demonstrate that waste bank systems can be adapted to diverse contexts, effectively supporting both environmental and social goals, and serve as a practical and effective model for the region

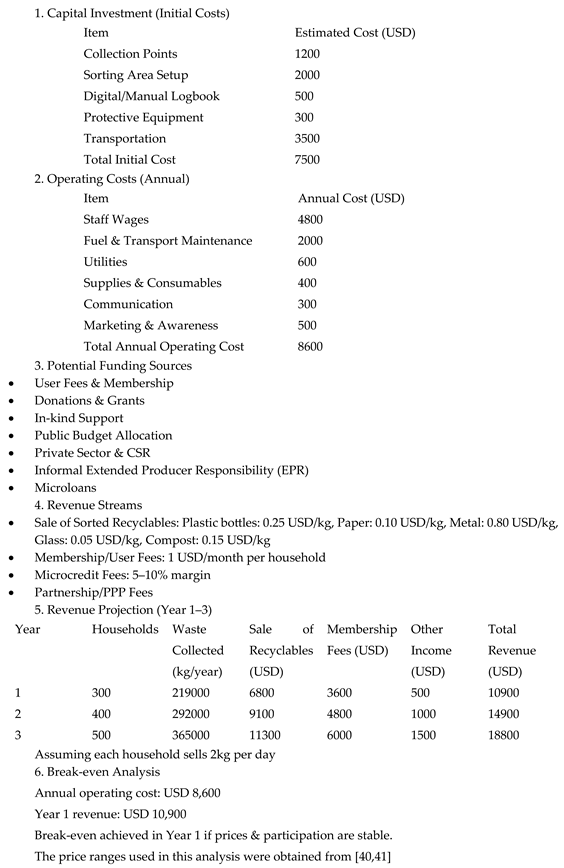

The operation and sustainability of the waste bank model rely on the basis of its core activities where waste collection, sorting, storage, and resale.

Table A1 in the Appendix presents a financial analysis of a waste bank system, using prices adopted from the existing initiatives in mainland Tanzania, and Zanzibar [

40,

41]. This analysis illustrates potential funding sources, revenue streams, costs, and savings associated with operating a community-based waste bank, providing a practical framework for assessing economic feasibility and sustainability in similar contexts. By consistently supplying high-quality recyclable materials to buyers and maintaining efficient logistics, the waste bank can strengthen its financial stability while fostering long-term community participation

Strategies to Enhance Waste Bank Programs

Community Engagement & Education

Conduct awareness campaigns in schools, local markets, religious and cultural gathering spaces to teach the importance of waste segregation and recycling.

Organize household level sorting workshops to equip individuals with practical waste management skills.

Responsible: Waste bank coordinators, local leaders through sheha committee, and volunteers

Youth and School Involvement

Establish school Eco-clubs and youth groups to collect and deposit recyclables, fostering responsibility and environmental stewardship.

Responsible:Teachers, school eco-club leaders, student volunteers

Environmental Clean-ups

Organize beach clean-ups to maintain a continuous supply of materials while reducing environmental pollution.

Responsible: Community volunteers, youth groups, NGOs, local authorities, hoteliers

Practical Recycling & Up-cycling

Responsible: Waste bank administrators, local artisans, technical trainers

Youth-Led Waste-to-Wealth Initiatives:

Engage young people in transforming waste into useful products, generating income, building skills, and supporting environmental sustainability, as demonstrated in the Maldives [

51].

Responsible:Youth entrepreneurs, NGOs

By implementing these strategies, the waste bank can strengthen its financial viability, maximize its environmental impact, and empower youth and women as active participants in sustainable waste management.