Introduction

Idiopathic edema (IE) is a disease of unknown etiology that occurs virtually exclusively in women between the ages of 20 and 60 years. It is characterized by a weight gain of >1.4 kg from morning to evening mostly in obese women with variable degrees of non-pitting edema of face and hands on awakening in the morning that are unrelated to menses. This is followed by increased abdominal girth with expansion of waist size, bloating, swelling of the trunks with tightening of the shirt and non-pitting edema of the lower extremities after assuming an upright posture. Once in bed they eliminate the fluid retained during the day in the form of nocturia every 2 to 3 hours to maintain stable weights the following morning. (1-6) The failure to include nocturia in characterizations of IE implies that there is no escape from the daily increase in weight. The daily weight gain without an escape would lead to an unabated increase in fluid overload that would lead to increasing edema and possibly congestive heart failure (CHF). The diagnosis of IE should be considered especially in any woman complaining of nocturia as an essential feature and an early clue to its diagnosis. Lack of nocturia would rule out the diagnosis of IE.

Various escape phenomena have been well characterized that are similar to the nocturia preventing perpetual fluid overload in IE. (7) Examples include deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) escape where the body counteracts the sodium retaining properties of DOCA by activating humoral, hemodynamic and neural mechanisms to reach an equilibrated state where sodium output matches input but at a higher extracellular volume (8); pitressin (vasopressin) escape in the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone as its V2 receptor down regulation reduces the distal tubule water reabsorption (9); diuretic escape from chronic diuretic administration such as furosemide by hypertrophy and proliferation of sodium transporters in the distal nephron (10); renal salt wasting escape from the recently identified natriuretic protein, haptoglobin related protein without signal peptide, where physiologic adjustments such as that found in DOCA escape will eliminate the sodium wasting by reaching an equilibrated state when sodium intake matches sodium output but at a lower blood volume (11,12); and now IE escape (7,13). A deficiency of a functional escape system can lead to serious hemodynamic consequences such as the persistent conservation of sodium in CHF, persistent sodium wasting in severe Addison’s disease or profound capillary leak in IE where intravascular volume depletion can be life-threatening. (14)

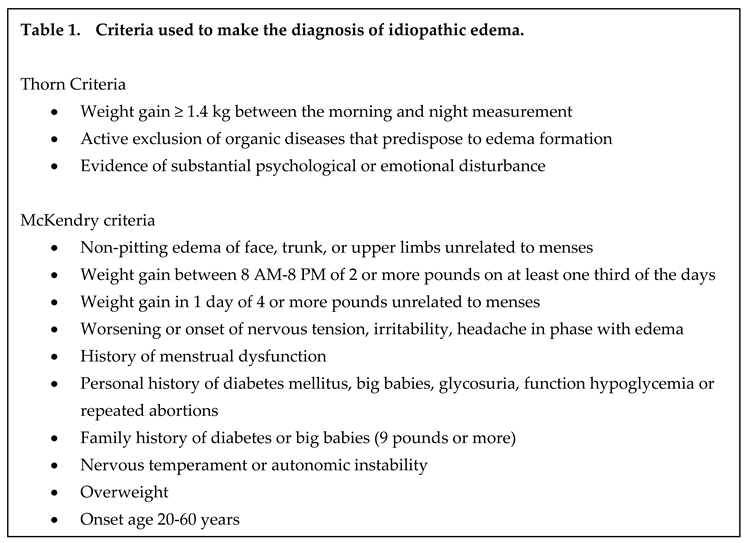

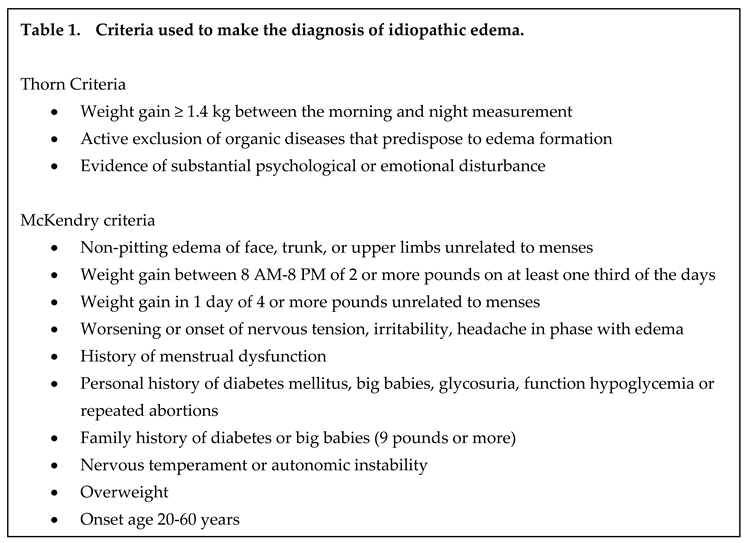

Patients with IE have also been characterized by obesity, diabetes with frequent miscarriages, having large babies and being significantly irritable and emotionally unstable, Table 1.

(1,2) Increased morbidity is not associated with increased mortality. (3,4) The multitude of nomenclatures such as cyclical edema, periodic edema, fluid retention syndrome, capillary leak syndrome and orthostatic edema reflects a state of confusion that, until recently, lacked a unified understanding of the pathophysiology and successful treatment of this enigmatic disease. (13,14) This poorly defined condition has not been fully recognized as a distinct clinical entity. It is also considered to be an untreatable condition. We sorted through some classic studies which set the pathophysiologic foundation to base our successful treatment of the varied clinical presentations of IE, including those that are life threatening. (5,6,13,14)

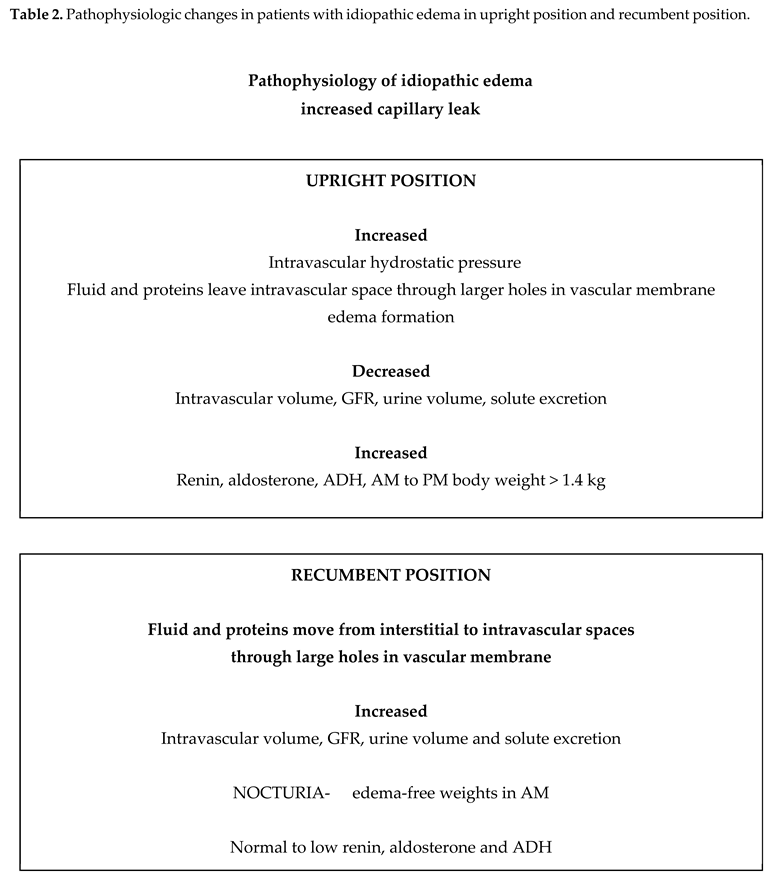

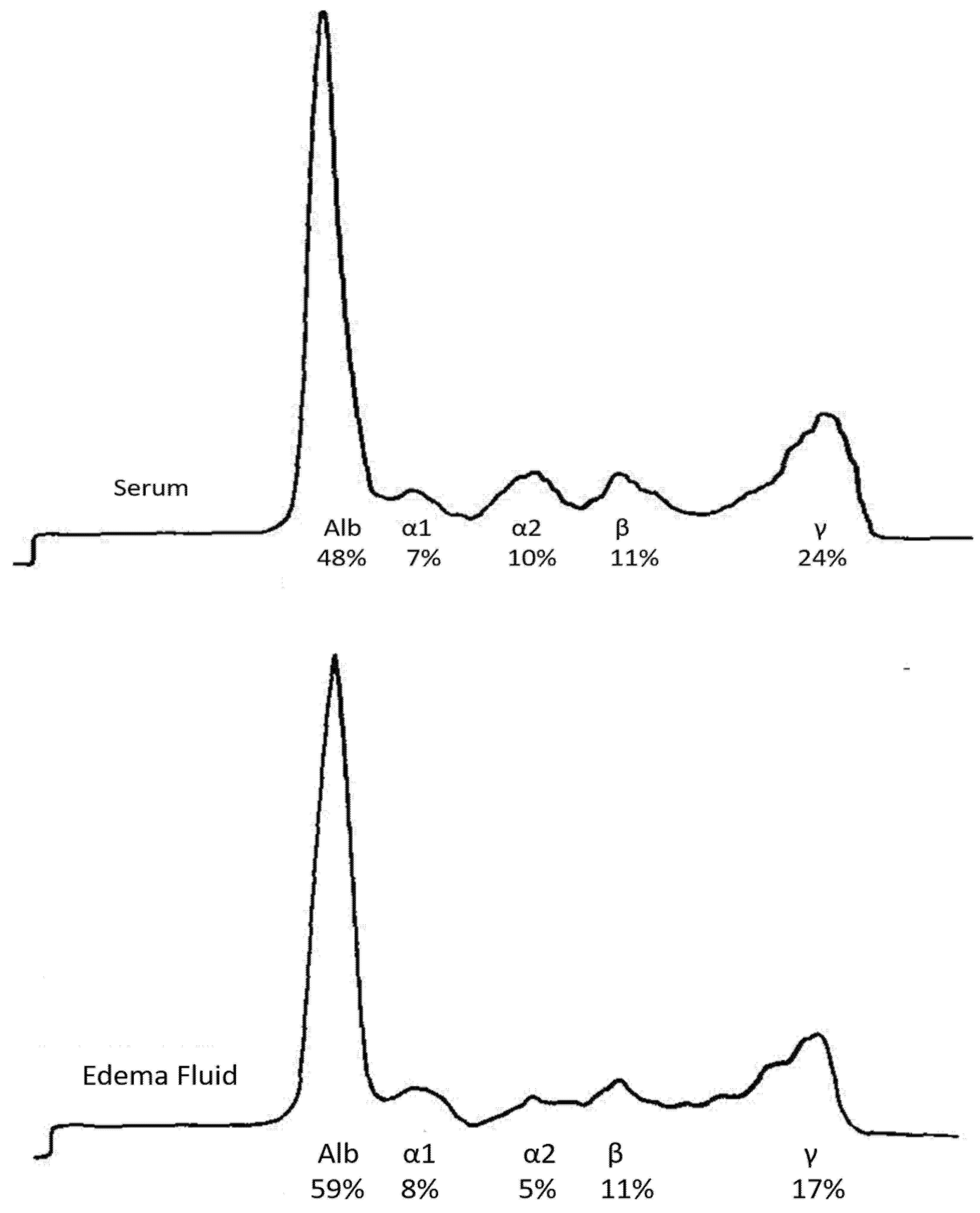

This review focuses on capillary leak as the single underlying physiologic abnormality leading to the complex physiology of edema formation via Starling’s forces. (15) We demonstrate how a variable increase in capillary leak can induce clinical presentations that appear to be disconnected and potentially life-threatening. Addressing the metabolic pathways that are affected by a capillary leak led to successful treatment of the diverse clinical presentations of IE with significant improvement in physical and emotional quality of life, Table 2. (5,6,13-15)

Successful Treatment of Idiopathic Edema, Including Life-Threatening Complications

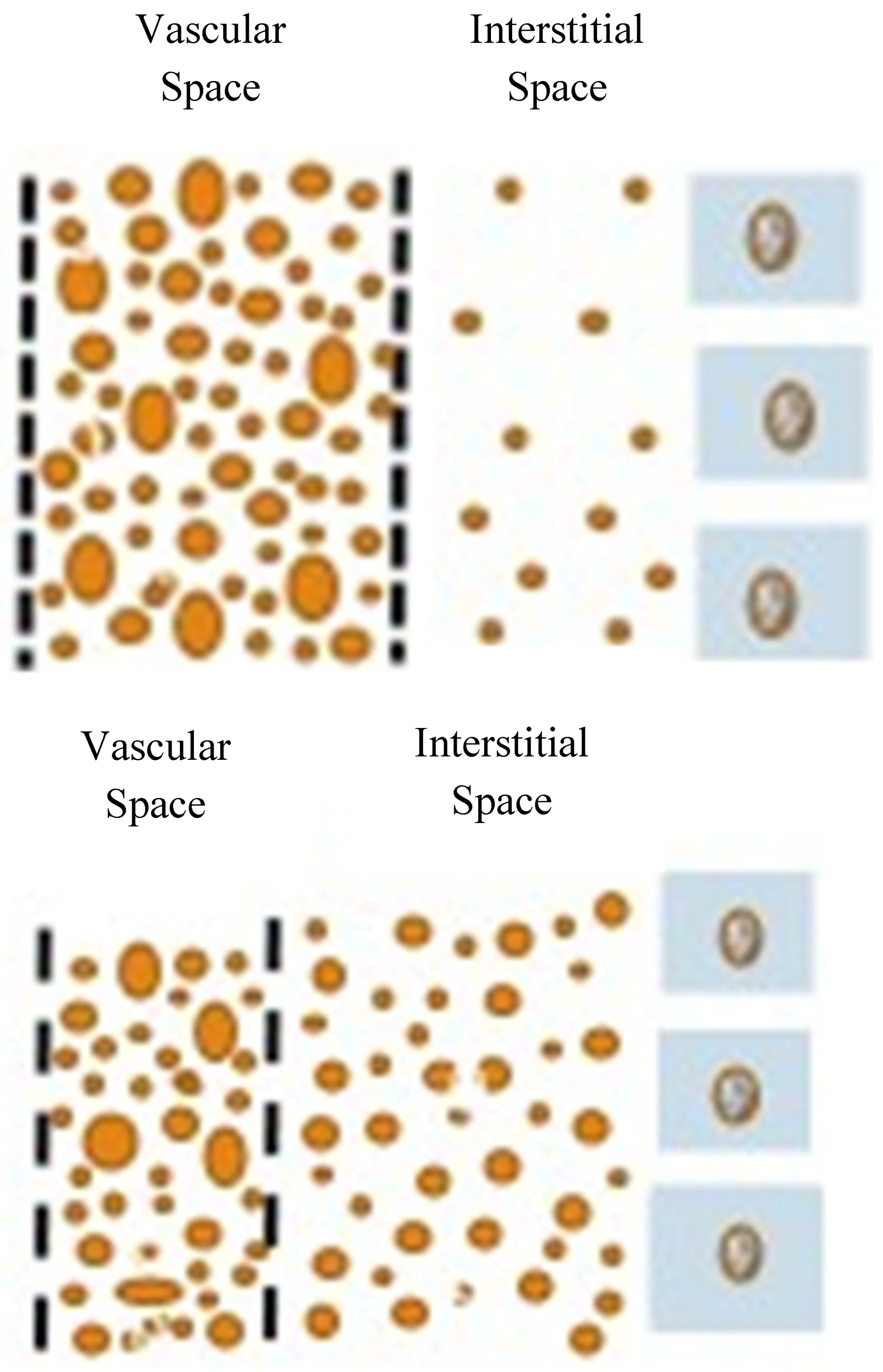

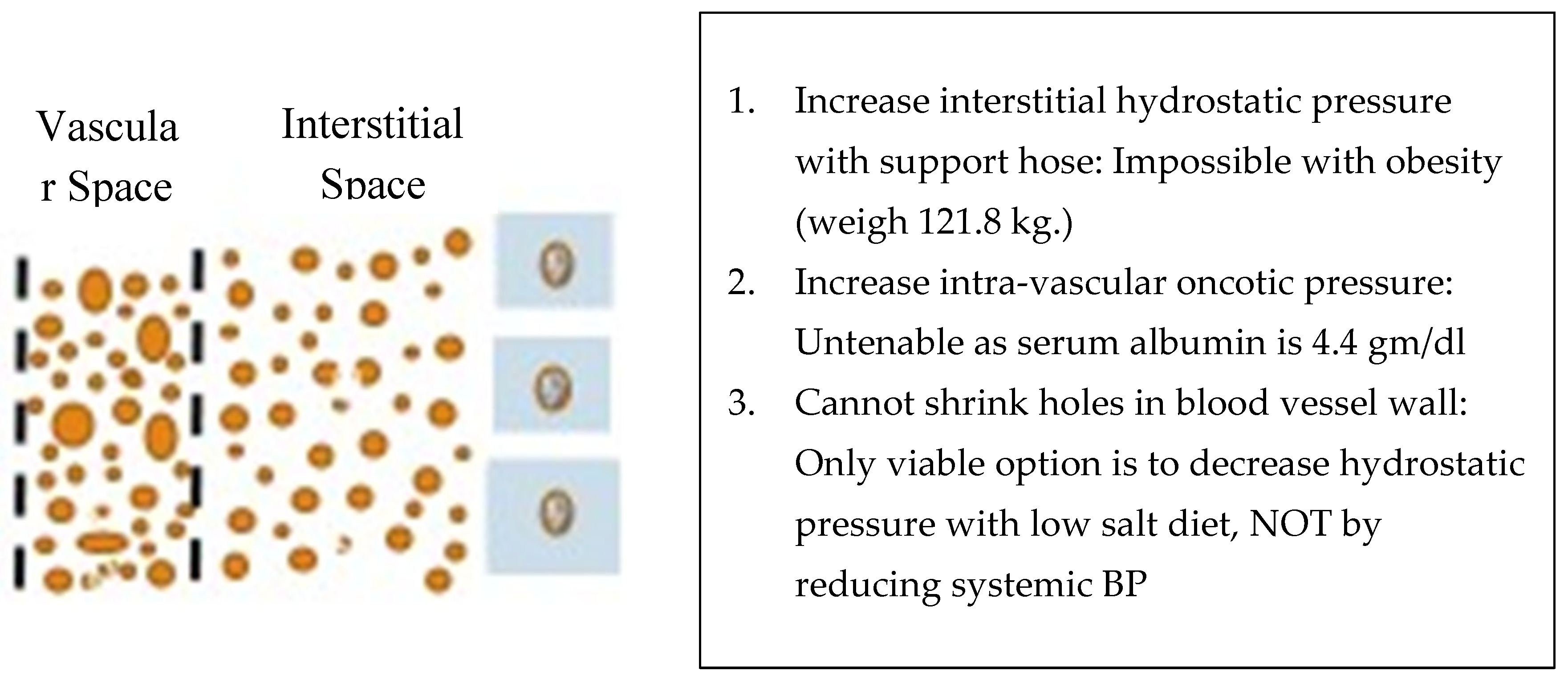

The treatment of IE has not been well defined and has been considered to be an untreatable disease. We treated 4 patients who met the criteria for IE by addressing the factors that contributed to edema formation according to Starling’s forces. (13) We reasoned through each variable and concluded that we could not increase intravascular oncotic pressure by increasing plasma protein content, lower systemic blood pressure to reduce hydrostatic pressure in the veins or eliminate the capillary leak, figure 3. We were left with two potential therapeutic options; 1. increase interstitial hydrostatic pressure to reduce or prevent proteins and fluid from leaving the intravascular space or 2. reduce intravascular hydrostatic pressure by reducing sodium intake. The first option to increase interstitial hydrostatic pressure could be accomplished by wearing support hose that extended up to the waist or higher. All 4 patients had body mass indices in the maximally obese ranges that made this option impossible to execute. The only viable option was to reduce intravascular hydrostatic pressure by reducing sodium intake,

Figure 3. (13)

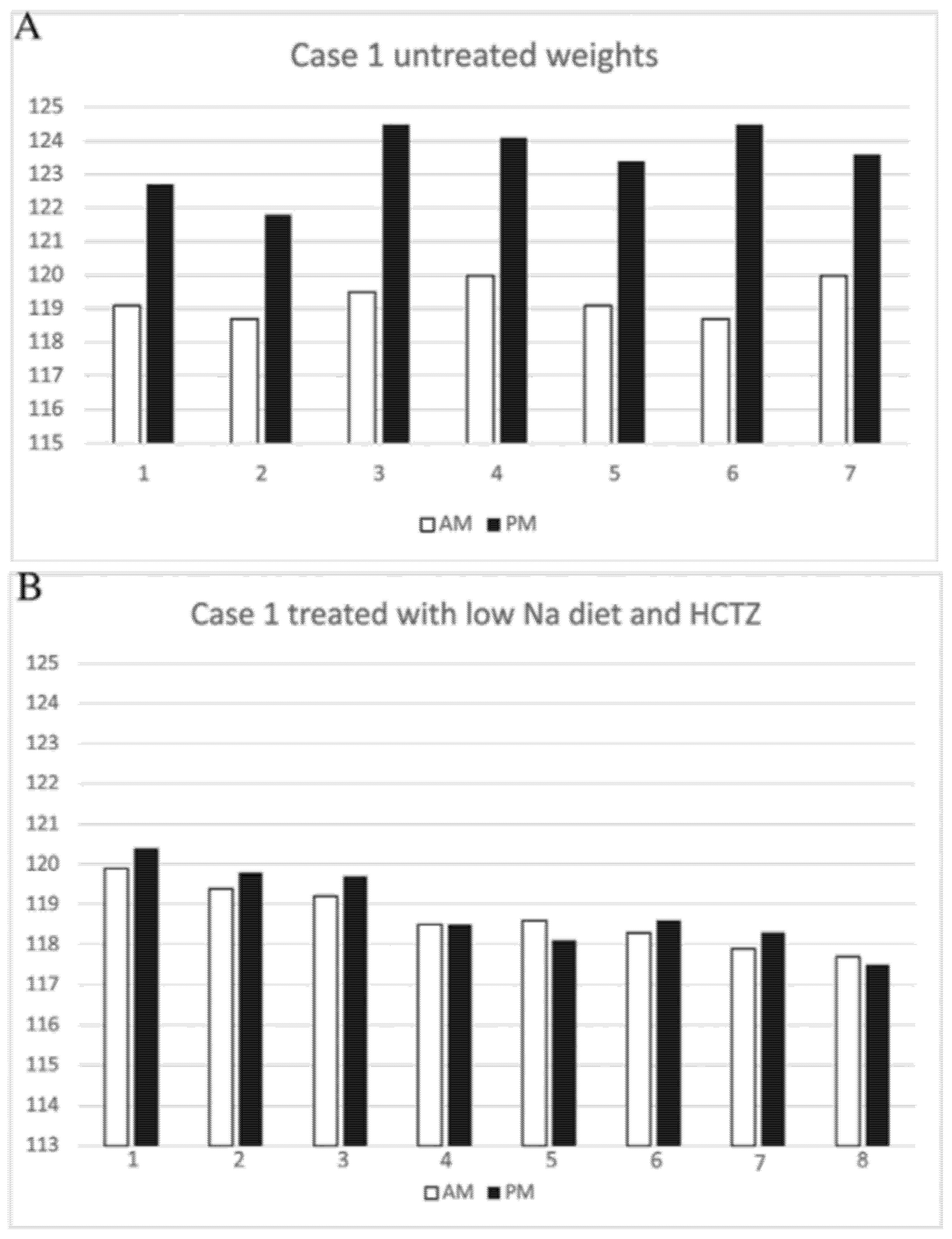

According to the American Heart Association website, a low salt diet is to ingest < 2000 mg of sodium per day, which is equivalent to ingesting 5 grams of salt. The first patient was a 44-year-old woman with a body weight of 121.8 kg, hypertension, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), type 2 diabetes mellitus, antiphospholipid syndrome with multiple miscarriages, sleep apnea and hypercholesterolemia who presented with typical symptoms of IE for 10 years. Utilization of support hose that extended up to her thorax was previously abandoned because of the difficulty in being fitted, the discomfort of having this cumbersome garment on during most of the day while being in an upright position and appearance of edema above the garment in the chest. She gained 3.5 to 5.5 kg from morning to bedtime while on a daily sodium intake of 3 to 4 gm/day with nocturia x 5 and stable edema-free weights the following morning, figure 4A. We gradually reduced her sodium intake to 1 gram/day, which yielded weights that did not differ from her morning weights by more than 1 kg with a reduction in nocturia to 1,

Figure 4B. (13)

The second patient was a 56-year-old obese woman with a history of PCOS, hypertension, gastro-esophageal reflux, primary hyperparathyroidism with parathyroidectomy, total hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy and hypercholesterolemia, who presented with signs and symptoms that met the criteria for the diagnosis of IE for 5 years. She weighed 95 kg and had weight gains between 1.4 to 2.3 kg between morning and bedtime with nocturia every 2 to 3 hours. She gained less than 0.7 kg during the day after reducing her sodium intake to approximately 1.0 gram/day.

The third patient was a 46-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, proteinuria, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, PCOS, biopsy diagnosis of focal segmental glomerulonephritis of the obesity type and obesity weighing 127.7 kg. The diagnosis of IE was entertained and proven because of history of nocturia x 3 to 4 over the previous 4 years by morning to bedtime weight gains of 1.8 to 2.7 kg. She denied swelling of face or hands on arising in the morning and increasing abdominal girth or tightness of her shirt with bloating that were present in the other patients with IE. Reducing her sodium intake to about 1.5 grams/day resulted in less than a 0.6 kg weight gain from morning to bedtime and reducing nocturia to once a night.

The fourth patient was a 23-year-old woman who presented with a recent history of microscopic hematuria with a biopsy diagnosis of a thin basement membrane, gastroparesis, recovery from COVID-19 infection and signs and symptoms typical of IE along with nocturia x 4 to 5. She weighed 74 kg and gained 2.5 to 3 kg from morning to bedtime on a 3-to-4-gram sodium intake along with the nocturia. She was treated with a low sodium diet approximating 1.75 grams per day but required hydrochlorothiazide to attain weight gains of less than 0.5 kg from morning to bedtime with absence of nocturia. (13)

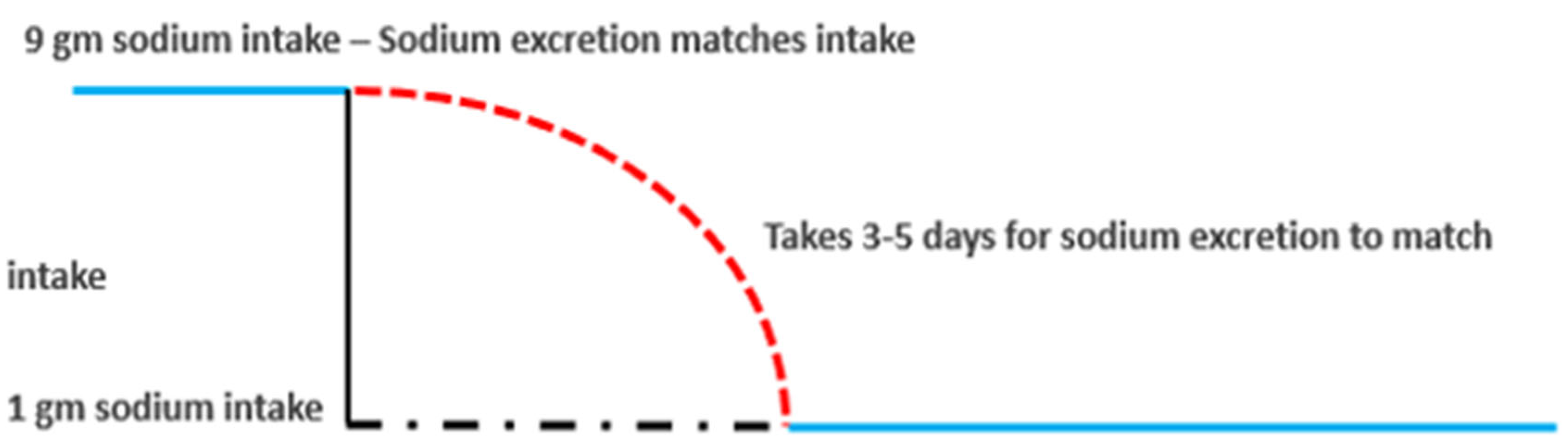

All four patients had difficulty sustaining consistently low sodium intake because of lifestyle circumstances that prevented them from maintaining a low sodium diet. A single episode of dietary indiscretion led to the discomfort of cyclical weight gains that took 3 to 5 days to resolve after returning to their customary low sodium diets. Any normal subject, who acutely reduces their daily sodium intake, will gradually reduce sodium excretion and reach a new equilibrated state in 3 to 5 days when sodium intake matches sodium excretion,

Figure 5A. (19)

Normal response to acute reduction in sodium intake

Sodium excretion matches input

Takes 3-5 days for sodium excretion to match low sodium intake

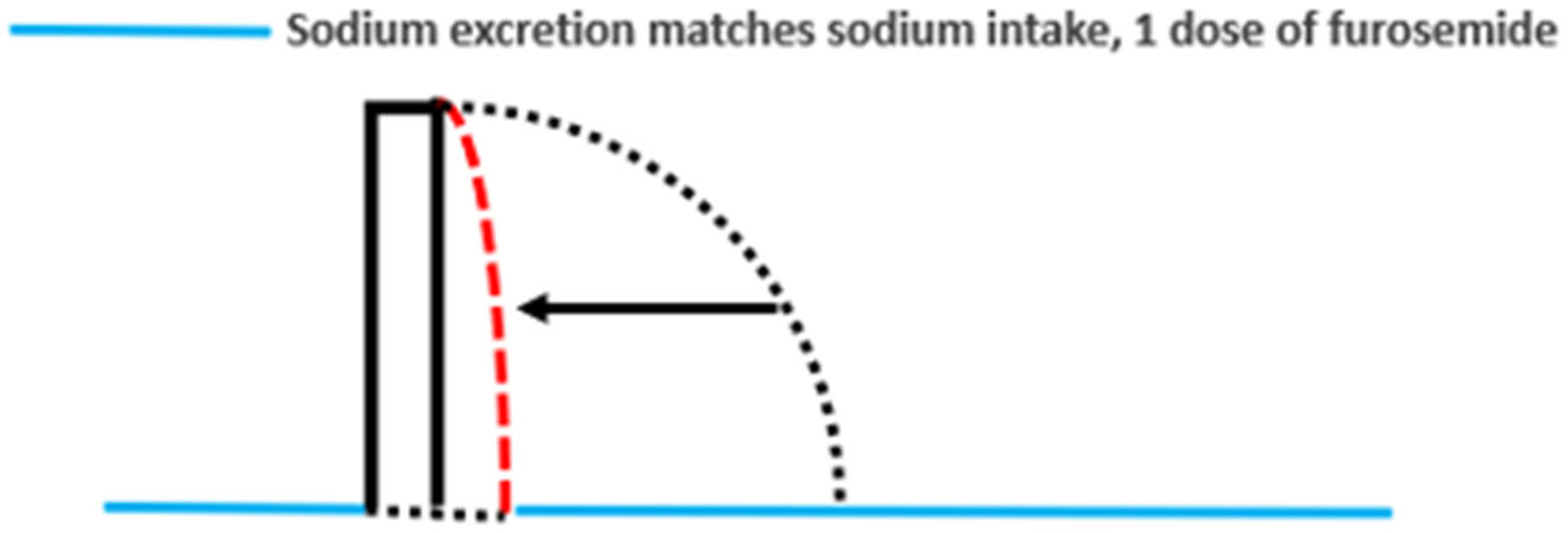

Effect of 1 episode of increased sodium intake

Furosemide following AM eliminates 3-5 days of bloating

This was found to be true in patients with IE where they experienced increased truncal and abdominal girth with bloating for 3 to 5 days after a single episode of eating a diet of higher sodium content. The patients took hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) the following morning whenever they had a high sodium intake the night before, which eliminated the 3 to 5 days of edema and bloating,

Figure 5B. (13,14) HCTZ was switched to 20 mg of furosemide because of the hypokalemia that required potassium supplementation with HCTZ.

Unusual Life-Threatening Complications of Idiopathic Edema

The majority of IE cases present with the cyclical edema and nocturia as described above. Unusual life-threatening complications can occur when the physiological consequences of the capillary leak are manifested by activation of other metabolic pathways. The first patient was an 81-year-old woman from Florida, who was referred for evaluation of 3 episodes of seizures and coma due to hyponatremia. It appears that she had symptoms of hyponatremia since the age of 77 when she experienced staggering gait and bumping into objects that bruised or abraded her knees. (20-22) In 2020 she was hospitalized for 3 episodes of seizures and coma with serum sodium of 117, 123 and 123 mmol/L, respectively. We explained that a large intake of water over a short period of time resulted in a rapid decrease in serum sodium which induced swelling of brain cells that was responsible for her coma and seizures. A larger volume of water intake could have led to greater swelling of the brain cells in a rigidly enclosed bony space that would cause sudden death by forcing the brainstem into the spinal canal as described in marathon runners and other sports activities. (22-24) One episode resulted in fracture of her sacrum that was associated with a seizure and coma while driving an automobile. She was intubated for extended periods of time which eventually required resection of a 90% stenosis of her trachea. When seen in New York, the limited information presented to us suggested that she might be suffering from a reset osmostat when she was noted to excrete a dilute urine with an osmolality of 158 mOsm/kg when her serum sodium was 133 mmol/L. While considering the rarity of dilute urines being excreted in hyponatremic conditions and an expected lower serum sodium when urines become dilute in reset osmostat (25), the patient mentioned that she gets up 4 times a night to urinate. Our first manuscript on IE stressed the “unappreciated importance of nocturia” that characterized patients with IE. (13) We proceeded to evaluate her for IE and realized she had swollen hands and face on arising and increased abdominal and truncal girth with bloating after assuming an upright posture that was followed by nocturia x 4 since the age of 18. Weights taken in the morning and at bedtime over 7 days revealed weight gains between 2.5 and 3.1 kg with nocturia x 4 that confirmed the diagnosis of IE. As noted above, the increased capillary leak in IE reduces intravascular volume, which is a potent stimulus for increased ADH production. ADH levels remain high because the inhibitory effect of the hypo osmolar plasma is overridden by the more potent volume stimulus for ADH secretion. (26) Under these volume depleted conditions, the hyponatremia will persist as long as the patient is drinking sufficient amounts of water, as normal subjects receiving daily administration of pitressin did not develop hyponatremia without adequate water intake. (27-29) The intravascular volume depletion also creates a prerenal state which decreases GFR, urine volume and solute excretion to promote edema formation when in an upright position, Table 2. (6,30)

When the patient assumes a recumbent position at bedtime, fluid and protein from the interstitial space moves into the intravascular space to normalize or increase intravascular volume which would reduce plasma renin, aldosterone and ADH levels, increase GFR and excrete large volumes of dilute urines of high solute content to increase nocturia and return to a non-edematous state in the morning. An overnight collection of urines during her second hyponatremic hospitalization illustrates these points when she excreted a total volume of 3,100 ml of urine with osmolalities that became progressively dilute at 251, 197, 165 and 146 mOsm/kg. The excretion of dilute urines removes pure water from the body to increase serum sodium or correct the hyponatremia. The complicated pathophysiologic changes noted during upright and recumbent positions in the hyponatremic IE patient are identical to a hyponatremic patient with renal salt wasting (RSW). The only differences are: 1. intravascular volume depletion in RSW is due to urinary losses of solute and water as compared to a shift in solutes and water from intravascular to interstitial spaces due to a capillary leak in IE and 2. correction of intravascular volume depletion and hyponatremia by isotonic saline infusions in RSW and shift of solutes and water from interstitial to intravascular space in IE. (14,31) In both conditions, the restoration of a high or normal intravascular volume eliminates the volume stimulus for ADH secretion and allows the coexisting hypoosmolality of plasma to inhibit ADH secretion, induce excretion of large volumes of dilute urine to correct the hyponatremia. (11,14,31)

The constant fear of having seizures was addressed by repeatedly explaining how we can eliminate the seizures and coma by avoiding intake of large volumes of water over a short period of time and the increase in truncal and abdominal girth with bloating and nocturia by reducing her sodium intake or add furosemide if she had a high sodium meal the night before. Controlling water intake to 4 ounces of water every 3 hours during the waking hours of the day led to serum sodium levels consistently above 137 mmol/L with more recent levels exceeding 139 mmol/L. It was difficult to limit her sodium intake to less than 1 gram a day because of very active social engagements. She learned to take furosemide the morning after consuming a high sodium diet the night before to eliminate the 3 to 5 days of edema and bloating,

Figure 5A and

Figure 5B

. (19) She was repeatedly reminded that the staggering and seizures with coma were due to excessive water intake and her swelling, increase in truncal and abdominal girth with bloating and nocturia were due to high sodium diets. In the course of two years all fears of seizures and coma and the complex of symptoms associated with IE dissipated as she is able to travel unsupervised and participate in many social activities. She is no longer fearful of having episodes of seizures and coma and understands why she had such puzzling effects of IE since age 18. She understands the derivation of her symptoms and has greatly improved her physical and emotional well-being.

The second patient is a 42-year-old woman with a history of immunologic deficiency with probable Sjogren’s syndrome and Raynaud’s phenomenon, proteinuria with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria since age 4 and frequent urinary tract infections. She presented with a history of postural dizziness with a single episode of fainting between 2000 and 2004. She had 4 to 5 fainting episodes with intermittent postural dizziness between 2004 and 2010. She fainted 6 to 8 times and fractured her wrist, elbow, shoulder and coccyx in 2016 and sprained her ankles 4 to 5 times, wrist 2 to 3 times, knee and shoulder that required long periods of rehabilitation, remained homebound and unable to work. She had foam placed over hardwood floors and any sharp edges, nonslip carpets on the stairways and about 20 rings placed at strategic areas of the wall to hold on to when she was dizzy while ambulating. She also sat down while showering and had access to a panic button should she fall or faint in the bathroom. Her lying blood pressure of 94/50 decreased to 55-60/25-30 mmHg standing as her pulse increased from 84 beats per minute lying to 136 beats per minute standing, which were more consistent with a volume depleted state rather than having autonomic failure where there is a meager increase in pulse rates after standing up. (32) While undergoing a diagnostic evaluation of her symptoms, she mentioned getting up 4 times a night to urinate. The diagnosis of IE was made by the history of swelling of hands and face in the morning followed by an increase in truncal and abdominal girth, bloating and edema with nocturia. She gained 2.0 to 2.7 kg from morning to bedtime and got up to urinate 4 times each night for one week. Her weight upon arising in the morning was 63 kg. It was apparent that her capillary leak was of such magnitude that there was sufficient amount of fluid moving from the intravascular to interstitial spaces to reduce blood volume to the extent of inducing severe postural hypotension, dizziness and fainting. The postural dizziness and fainting associated with IE eliminated salt restriction as a therapeutic option. The most reasonable option was to wear support stockings extending up to her waist to increase interstitial hydrostatic pressure and prevent fluid from leaving the intravascular spaces. On this regimen her lying blood pressure of 94/57 was unchanged at 95/65 standing while her pulse increased from 88 beats per minute lying to 121 beats per minute standing. The support stocking also eliminated the weight gain from morning to bedtime and nocturia. Her postural hypotension and signs and symptoms of IE were no longer a problem as long as she wore her support hose that extended to her waist. She was fortunately not obese like many of our other patients who would have had great difficulty wearing the support stockings. Postural hypotension of this severity would be extremely difficult to treat in very obese patients but should be attempted because there are no alternatives for this life-threatening complication of IE. There is a single case of a patient who had intermittent bouts of severe capillary leak that led to her demise from one of her recurrent hypotensive episodes. (18) This case does not appear to fall under the category of IE because of the intermittency of the disease, which has not occurred in other patients with IE over extended periods of time. Capillary leak has been demonstrated in many clinical conditions such as sepsis, autoimmune diseases, drugs and hyperestrogenism that add further insights into clinical outcomes resulting from a capillary leak. (33-35)

Summary and Concluding Remarks

It is apparent from the cases included in this review that an increase in capillary leak can lead to seemingly disparate clinical presentations. We are uncertain of the prevalence of IE in the general population, but it appears to be more common than it is perceived to be. The duration of undiagnosed cases of IE included in this review suggests that IE does not appear to be readily recognized as a disease. Recognizing and understanding the spectrum of pathophysiologic and clinical presentations resulting from a single leaky capillary membrane greatly improved the physical and emotional well-being of these patients. Understanding led to substantial emotional stability. While we advocate an attempt to understanding and teaching the pathophysiologic consequences of a capillary leak, a practical clinical approach can be summarized by highlighting the sequence of events that will lead to a diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

What are the factors that make you think of IE.

- I.

-

Idiopathic edema

- 1)

-

Signs and symptoms

- a)

Patient is a woman

- b)

Notes swelling of thorax and abdomen with tightening of the shirt and increase in abdominal girth with bloating and swelling of legs after standing up.

- c)

Nocturia

- 2)

-

Work up for IE

- a)

> 1.4 kg weight gain AM to bedtime for I week

- b)

Getting up to urinate > 2 times

- II.

-

Idiopathic edema presenting with Hyponatremia

- 1)

-

Signs and symptoms

- a)

Staggering, falling, difficulty with mentation

- b)

Rarely seizures or coma

- c)

Serum sodium < 135 mmol/L

- d)

Signs and symptoms of IE

- III.

-

Postural hypotension and dizziness-fainting

- 1)

If present, consider IE as above.

- 2)

Take BP and pulse lying and after standing up

- IV.

Treatment

- 1)

-

Idiopathic edema

- a)

Sodium restricted diet

- b)

-

Furosemide

- i.

After single increase in sodium intake

- ii.

Daily to improve quality of life with high sodium intake every day

- c)

Avoid acute ingestion of large volume of water

- 2)

-

Hyponatremia

- a)

Avoid acute ingestion of large volume of water

- b)

4 ounces of water every 3 hours

- c)

Sodium restriction with or without furosemide

- 3)

-

Postural hypotension-dizziness-fainting

- a)

Support stocking above waist

- b)

sodium restriction contraindicated

Author Contributions

Dr. John K. Maesaka recruited all of the patients from a limited practice of nephrology. He was responsible for the care of these patients in addition to reviewing the literature, writing the manuscript and setting up the tables and figures. Dr. Louis J. Imbriano participated in the discussions of each patient in terms of diagnosis and treatment, reviewed the literature, edited each draft of the manuscript and helped to organize the proper formatting, to meet the requirements of the Journal of Clinical Medicine, including assisting in the submission process. Dr. Candace Grant participated in the discussions on identification, work up and treatment of all cases of idiopathic edema, performed a literature review, edited crafts of the manuscript as all stages in terms of accuracy and scientific merit, including preparation for submission to the Journal of Clinical Medicine. Drs. Nobuyuki Miyawaki and Minesh Khatri participated in the discussion of each case in terms of diagnosis and treatment and edited preliminary drafts for accuracy and quality of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of NYU-Long Island (formerly Winthrop University Hospital).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

| ADH |

Antidiuretic hormone |

| DOCA |

Deoxycorticosterone acetate |

| CHF |

Congestive Heart Failure |

| GFR |

Glomerular filtration rate |

| HCTZ |

Hydrochlorothiazide |

| IE |

Idiopathic edema |

| PCOS |

Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| RSW |

Renal salt wasting |

References

- Thorn, G. Approach to the patient with “idiopathic edema” or “periodic swelling”. JAMA 1968, 206, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, J.B. Idiopathic edema. Can Nurse. 1973, 69, 41–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sterns, R.H. Idiopathic edema. Up to Date. Editors Emmett M, and Post TW, Waltham, MA.

- Kay, A.; Davis, C.L. Idiopathic edema. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1999, 34, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, O.M.; Bayliss, R.I.S. Idiopathic Oedema of Women: A Clinical and Investigative Study. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 1976, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeten, D.H. Idiopathic edema. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin N. Am. 1995, 24, 531–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maesaka, J.K.; Imbriano, L.J.; Miyawaki, N. Determining Fractional Urate Excretion Rates in Hyponatremic Conditions and Improved Methods to Distinguish Cerebral/Renal Salt Wasting From the Syndrome of Inappropriate Secretion of Antidiuretic Hormone. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohring, J.; Mohring, B.; Littlejohn, N.K.; Siel, J.R.B.; Ketsawatsomkron, P.; Pelham, C.J.; Pearson, N.A.; Hilzendeger, A.M.; Buehrer, B.A.; Weidemann, B.J.; et al. Reevaluation of DOCA escape phenomenon. Am. J. Physiol. Content 1972, 223, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Sandberg, K.; Murase, T.; Baker, E.A.; Speth, R.C.; Verbalis, J.G. Vasopressin V2 Receptor Binding Is Down-Regulated during Renal Escape from Vasopressin-Induced Antidiuresis1. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, D.H.; Felker, G.M.; Ingelfinger, J.R. Diuretic Treatment in Heart Failure. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1964–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesaka, J.K.; Imbriano, L.J.; Miyawaki, N. High Prevalence of Renal Salt Wasting Without Cerebral Disease as Cause of Hyponatremia in General Medical Wards. Am. J. Med Sci. 2018, 356, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maesaka, J.K.; Imbriano, L.J.; Pinkhasov, A.; Muralidharan, R.; Song, X.; Russo, L.M.; Comper, W.D. Identification of a Novel Natriuretic Protein in Patients With Cerebral-Renal Salt Wasting—Implications for Enhanced Diagnosis. Am. J. Med Sci. 2021, 361, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, K.; Imbriano, L.J.; Miyawaki, N.; Maesaka, J.K. Pathophysiologic approach to understanding and successfully treating idiopathic edema: Unappreciated importance of nocturia. Am. J. Med Sci. 2022, 364, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesaka, J.K.; Imbriano, L.J.; Grant, C.; Miyawaki, N. Successful treatment of unusual life-threatening complications of idiopathic edema. Am. J. Med Sci. 2024, 368, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, M.; Horwith, M.; Brown, J.L. Idiopathic edema: Studies demonstrating protein-leaking angiopathy. Am. J. Med. 1970, 49, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, E.H. Contributions to the Physiology of Lymph Secretion. J. Physiol. 1893, 14, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wardener, H.E. Idiopathic edema: Role of diuretic abuse. Kidney Int. 1981, 19, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanga, Z.; Brunner, A.; Leuenberger, M.; Grimble, R.F.; Shenkin, A.; Allison, S.P.; Lobo, D.N. Nutrition in clinical practice—the refeeding syndrome: illustrative cases and guidelines for prevention and treatment. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 62, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, B.; Thompson, D.; Horwith, M.; Luckey, E. Cyclical edema and shock due to increased capillary permeability. Am. J. Med. 1960, 29, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, B.; Musch, W.; Vandemergel, X.; Manto, M.U.; Decaux, G. Mild Chronic Hyponatremia Is Associated With Falls, Unsteadiness, and Attention Deficits. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 71.e1–71.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaux, G. Morbidity Associated with Chronic Hyponatremia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingert, M.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Weiss, K.; Thuany, M.; Chlíbková, D.; Knechtle, B. Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia in Marathon Runners. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, M.H.; Kirven, J. Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengne, F.G. Adaptation of the Brain to Hyponatremia and Its Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbriano, L.J.; Ilamathi, E.; Ali, N.M.; Miyawaki, N.; Maesaka, J.K. Normal fractional urate excretion identifies hyponatremic patients with reset osmostat. J. Nephrol. 2012, 25, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stricker, E.M.; Verbalis, J. Water intake and body fluids. In Fundamental Neuroscience, 2nd ed.; Squire, L.E., Roberts, J.L., Spitzer, N.C., Zigmond, M.J., McConnell, S.K., Bloom, F.E., Eds.; Elsevier: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 1011–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Jaenike, J.R.; Waterhouse, C. THE RENAL RESPONSE TO SUSTAINED ADMINISTRATION OF VASOPRESSIN AND WATER IN MAN*. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1961, 21, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinsky, N.G.; Davidson, D.G.; Berliner, R.W.; Verbalis, J.G.; Jonassen, T.E.N.; Nielsen, S.; Christensen, S.; Petersen, J.S. Changes in urine concentration during prolonged administration of vasopressin and water. Am. J. Physiol. Content 1959, 196, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leaf, A.; Bartter, F.C.; Santos, R.F.; Wrong, O. Evidence in man that urinary electrolyte loss induced by pitressin is a function of water retention 1. J. Clin. Investig. 1953, 32, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelo, J.G. Normotensive Ischemic Acute Renal Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesaka, J.; Miyawaki, N.; Palaia, T.; Fishbane, S.; Durham, J. Renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: Diagnostic value of urate determinations in hyponatremia. Kidney Int. 2007, 71, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieling, W.; Kaufmann, H.; E Claydon, V.; van Wijnen, V.K.; Harms, M.P.M.; Juraschek, S.P.; Thijs, R.D. Diagnosis and treatment of orthostatic hypotension. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, T.; Jewelewicz, R.; Dyrenfurth, I.; Speroff, L.; Wiele, R.L.V. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Report of a case with notes on pathogenesis and treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972, 112, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrenko, A.P.; Castelo-Branco, C.; Marshalov, D.V.; Salov, I.A.; Shifman, E.M. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. A new look at an old problem. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddall, E.; Khatri, M.; Radhakrishnan, J. Capillary leak syndrome: etiologies, pathophysiology, and management. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).