1. Introduction

Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapies can cure up to 95% of patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [

1]. This makes the identification and timely treatment of infected individuals a cornerstone strategy not only to reduce mortality from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, but also to interrupt onward transmission [

2].

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is often asymptomatic, with up to 90% of infected individuals unaware of their status [

3]. Many of they do not seek medical care, yet remain a source of potential transmission. Such individuals are typically identified incidentally, e.g., during medical visits for unrelated reasons, or through targeted screening of selected subpopulations within the conditionally healthy population.

Population-wide screening seems currently impractical; therefore, the focus shifts to identifying subgroups (defined by region, sex, age, or social characteristics) where the proportion of HCV carriers is highest. Data from such studies can be used for the development of targeted diagnostic and treatment programs.

The primary serological marker of HCV infection is the presence of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV), representing both IgG and IgM against viral antigens [

4]. Detection of HCV RNA by PCR serves two purposes: confirming chronic infection—an indication for initiating antiviral therapy according to clinical guidelines [

5], and identifying active viral replication. Individuals with detectable HCV RNA derive the greatest benefit from treatment and should be prioritized for it [

6].

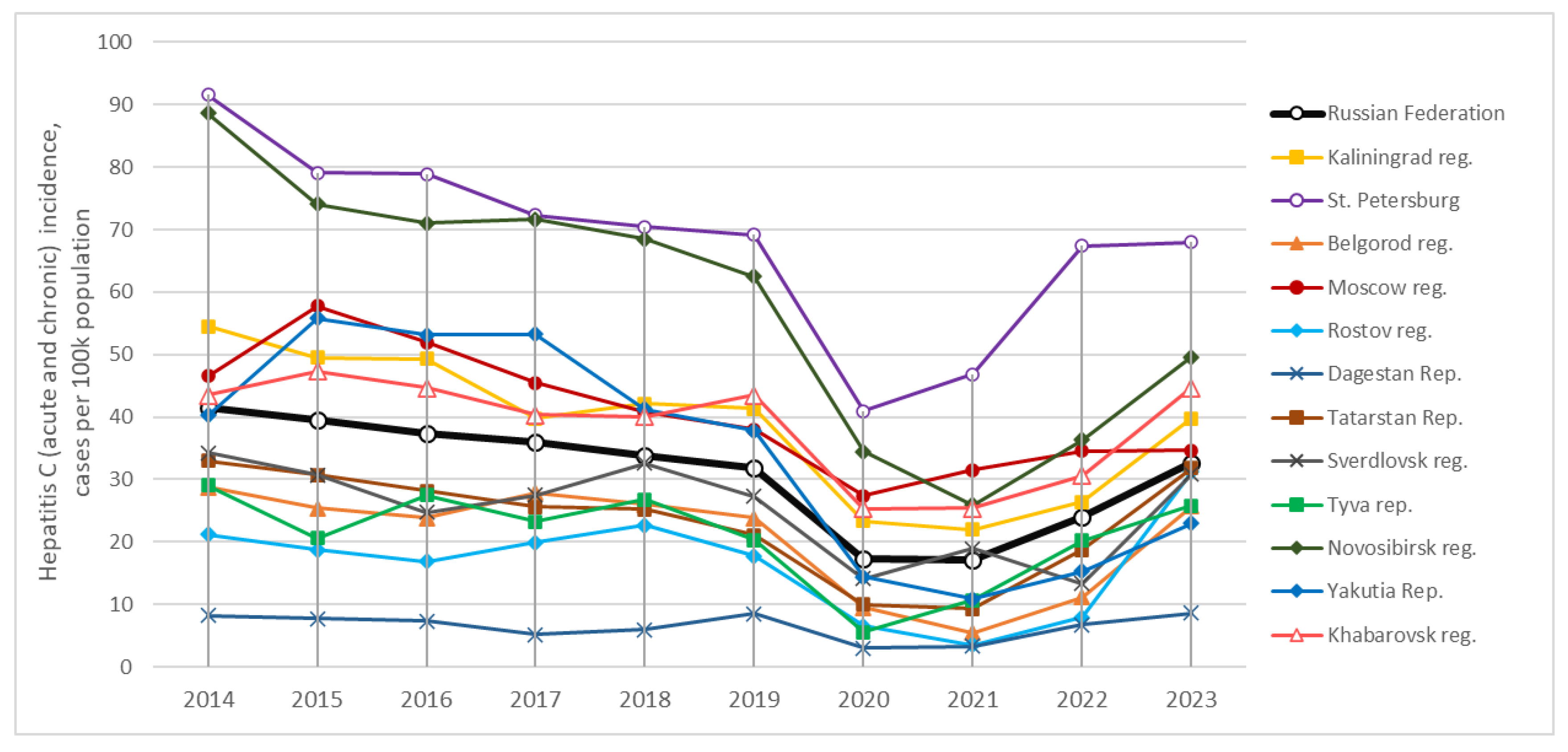

HCV remains a significant public health problem in the Russian Federation. National surveillance data show that, over the past decade (2014–2024), the incidence of acute hepatitis C (AHC) has remained stable at 1–1.5 cases per 100,000 annually, while CHC has been reported at 31–40 cases per 100,000 [

7,

8]. Long-term incidence trends show no consistent decline (

Figure 1); the transient drop during 2020–2021 likely reflects COVID-19–related disruptions to healthcare [

7]. Some estimates suggest that ~1.8% of the Russian population are HCV carriers [

9], that is a moderately high rate globally. For comparison, prevalence is estimated at 0.1–0.2% in Western Europe, 0.3–0.4% in China and India, and 0.7% in the United States; higher rates are reported in Ukraine (3.3%) and Pakistan (3.8%) [

9]. Given its population size, Russia ranks among the top five countries worldwide in absolute number of carriers, estimated at 2.7 million [

9]. Another estimates, based on the mathematical modelling [

10] suggests even higher numbers, up to 4.25 million (2.9%) in 2020.

National averages, however, mask substantial heterogeneity across Russia’s diverse geographic, economic, and demographic regions. Studies in conditionally healthy populations have reported anti-HCV prevalence both far below and well above the national average. Within the same Sakha Republic (Yakutia), for example, estimates have ranged from 0–1% to 10–13%, depending on climatic zone (Arctic or southern districts) and study period (1999–2002 vs. 2005–2006) [

11,

12].

In this context, we aimed to assess age- and sex-specific HCV prevalence in an conditionally healthy population across twelve Russian regions (

Table 1), drawing on both original data and published studies. Our findings are intended to help public health authorities better identify high-risk groups for targeted screening and to ensure timely access to antiviral therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Samples Collection

A total of 42,055 healthy volunteers from twelve regions across the Russian Federation, spanning west to east, participated in the serosurvey conducted over multiple years (

Table 1). Data from 30,724 of these participants are published here for the first time. The data obtained from another 8,937 volunteers have previously only appeared in Russian-language publications (see references in

Table 1). To compare our results with earlier findings, we also refer to studies by other authors, as cited throughout the text.

In the main text, as well as in the tables and figure captions, we use abbreviated names for the studied regions. Specifically, Kaliningrad, Belgorod, Rostov, Sverdlovsk, Novosibirsk, and Khabarovsk regions are referred to by the names of their capital cities. For the republics, we use the names Dagestan, Tatarstan, and Tyva. “Moscow” and “St. Petersburg” refer to the combined populations of Moscow city with Moscow Region, and St. Petersburg with Leningrad Region, respectively. In the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), we identified two distinct groups. The group generally referred to as “Yakutia” represents the population of the so-called “agricultural zone” (southern districts, including the major cities of Yakutsk and Neryungri), studied in 2008 and 2018 (

Table 1). The “Arctic zone of Yakutia” refers to the northern Momsky District, surveyed in 2022 (

Table 1). This distinction is important, as the southern and northern regions of Yakutia have shown marked differences in the epidemiology and prevalence of parenteral hepatitis [

11,

12].

The study included male and female participants aged 0 to 95 years, divided into nine age groups: under 1 year, 1–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years. The number of participants in each age group and region is shown in

Supplementary Table A-1. The male-to-female ratio ranged from 1:1 to 1:2.1, depending on the region (

Table 1 and

Table A-1).

All participants met the following inclusion criteria: apparently healthy, with no obvious symptoms of acute illness at the time of enrollment, and permanent residency in the study region. Exclusion criteria included a history of liver disease (infectious or non-infectious), any current acute illness/body temperature above 37.1 °C; as well as any surgery, blood transfusion, or treatment with blood products in the three months prior to enrollment (self-reported or, for participants under 15 years of age, reported by a parent or guardian).

All serum samples were coded, aliquoted, and stored at −70 °C until testing.

2.2. Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki for ethical medical research involving human subjects. Informed written consent was signed by all the participants or their legal guardians. The study protocol was approved by the Independent Interdisciplinary Ethics Committee for the Ethical Review of Clinical Research, Moscow, Russia (Approval No. 17, November 16, 2019), and by the Ethics Committee of the Mechnikov Research Institute for Vaccines and Sera, Moscow, Russia (Approval No. 1, February 28, 2018). The study conducted in 2008 was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chumakov Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis, Moscow, Russia (Approval No. 6, April 1, 2008).

2.3. ELISA Testing

Serum samples from Belgorod region (

Table 1) were tested for anti-HCV antibodies using the Architect Anti-HCV test (Abbott Laboratories). Samples reactive in the screening test were confirmed by immunoblotting for antibodies to structural and non-structural HCV proteins (INNO-LIA HCV, Fujirebio Europe N.V.). All other serum samples listed in

Table 1 were tested for anti-HCV (IgG + IgM) using commercial ELISA kits (Vector-Best, Russia). Samples that tested positive in the screening assay were subsequently analyzed using the anti-HCV confirmation test from the same manufacturer. A participant was classified as an anti-HCV-positive carrier if their sample tested positive in the confirmation ELISA.

2.4. PCR Testing

All samples that were found to be positive in the anti-HCV confirmation assay, were further examined using a commercial real-time PCR kit for qualitative detection of HCV RNA (AmpliSens, Russia). This assay has a detection limit of 10 IU/mL when nucleic acids are extracted from a 1 mL sample. Samples collected in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Dagestan, Novosibirsk, and Khabarovsk (2018–2020; see

Table 1) that were negative for anti-HCV by ELISA were also tested by PCR in pools of 10 samples using the same AmpliSens reagent kit. If a pooled sample tested positive for HCV RNA, each of the 10 individual samples in the pool was subsequently tested to identify the HCV RNA-positive sample.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis included assessment of differences in proportions of anti-HCV carriers in groups/cohorts using the Chi-square test with Yates’ correction, or Fisher’s exact test for small samples. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Confidence intervals (95% CI) for proportions were calculated using the binomial distribution. Correlation coefficients (r) between quantitative variables, such as the incidence of hepatitis C and anti-HCV prevalence, were determined using the two-tailed Spearman’s non-parametric test in Prism software (GraphPad, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Anti-HCV Prevalence Among Regional Groups

The prevalence of antibodies to the hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV prevalence) in the regional groups surveyed in 2018–2022 is summarized in

Table 2, with separate data for men and women. Detailed age stratification data are provided in

Supplementary Table A-1.

Table 3 presents the results of pairwise comparisons between regional groups from 2018–2022, based on the proportions of anti-HCV-positive individuals, using the chi-square test.

Based on these results, the 2018–2022 regional groups can be broadly classified into three categories. The regions with a relatively low prevalence of anti-HCV (1.1–1.4%) included Belgorod Region, Moscow (including Moscow City and Moscow Region), and Saint Petersburg (including Saint Petersburg City and Leningrad Region). Differences among these regions were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Moderate anti-HCV prevalence (1.8–2.1%) was found in Republic of Dagestan, Republic of Tatarstan, Novosibirsk Region, Republic of Tyva, and Republic of Sakha (Yakutia, southern districts). Differences within this group were also not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Finally, high prevalence (3.4–5.2%) was reported for Khabarovsk Region and Yakutia (Arctic zone). Differences between these two regions were not statistically significant (p > 0.05;

Table 3).

Kaliningrad Region occupied an intermediate position, statistically similar to both regions with the moderate prevalence (Republic of Tatarstan and Republic of Tyva) and to the high-prevalence region of Khabarovsk. Notably, two moderate-prevalence regions (Republic of Tatarstan and Republic of Tyva) did not differ significantly from low-prevalence regions (Saint Petersburg and Moscow). Apart from these overlaps, differences between the three prevalence categories were statistically significant (

Table 3).

Data for the 2008 survey are also presented in

Table 2 and

Supplementary Table A-1. In 2008, both low- and high-prevalence groups were identifiable: Moscow (1.7%) represented the lower end, while the Republic of Tyva and Yakutia (3.3%), were at the higher end (p < 0.05,

Table 2). Rostov Region and Sverdlovsk Region occupied intermediate positions (2.1–3.0%) and did not differ significantly from any of the other regions in 2008.

These findings indicate that, at least up to the recent 2018–2022 period, the prevalence of HCV infection in the Russian Federation has remained markedly heterogeneous across regions.

3.2. Dynamics of Anti-HCV Prevalence in Regional Groups Over Time

The anti-HCV prevalence in the conditionally healthy population across the surveyed regions at two time points (2008 and 2018–2022; see

Table 2 and

Table 3) made it possible to evaluate temporal trends. Additional conclusions were drawn by comparing our findings with similar studies performed by other researchers in the same regions.

In Moscow, the proportion of anti-HCV carriers decreased from 1.7% in 2008 to 1.2% in 2018–2019. However, this decrease was not statistically significant (see confidence intervals in

Table 2).

For Novosibirsk region, data on the anti-HCV prevalence in the conditionally healthy population were previously reported for the period 1995–1999 [

20]. In that study, a group of 1,073 individuals were examined, including schoolchildren, medical students, and randomly selected adults, with a mean anti-HCV prevalence of 4.2±1.2%. Another study [

21], conducted in 2000–2002, reported a prevalence of 5.6±2.1% among 500 patients attending a non-infectious outpatient clinic. The prevalence estimates from these two earlier studies did not differ significantly from each other, but both were significantly higher than the value obtained in our study for Novosibirsk Region in 2019–2020 (1.9 ± 0.3%, p-value < 0.01;

Table 2).

In the Republic of Tyva, the proportion of anti-HCV-positive carriers also declined from 3.3% in 2008 to 2.0% in 2019; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p-value > 0.05).

The proportion of anti-HCV carriers among the conditionally healthy population of Yakutia (excluding the Arctic zone; see below), as observed in our study in 2018, was 2.0%, which was lower than the 3.3% recorded in 2008 (

Table 2), although the difference was not statistically significant. At the same time, a comparison with earlier results reported from the same southern regions of Yakutia reveals a more pronounced downward trend. In particular, a study conducted between 1999 and 2002 [

11], which included 1,394 adolescents and adults from the southern “agricultural” districts of Yakutia (Namsky, Gorny, Vilyuisky), reported a high mean anti-HCV prevalence of 6.2±1.3% (ranging from 2.7% to 13.4% depending on age). A subsequent study carried out in 2005–2006 in the city of Neryungri, also located in southern Yakutia, examined 329 apparently healthy individuals and reported an even higher prevalence of 13.1±3.9% [

12]. Both of these values were significantly higher than those observed in our study for the same “agricultural” zone in 2008 (3.3%) and, especially, in 2018 (2.0%) (

Table 2; p-value < 0.01 for all comparisons).

Thus, the available data suggest a decreasing trend in the prevalence of antibodies to the HCV in these regions from 2008 (or earlier) to more recent years (2018–2020), although this trend was not always statistically significant.

However, this decline was not observed in all study groups. For example, in the same study cited above [

11], a very low prevalence of antibodies to the HCV was recorded in the Abyisky and Eveno-Byntaisky districts of the Arctic zone of Yakutia: 0% among 296 children and 162 adolescents, and 1.1% among 370 adults. It should be noted that these figures refer to the northern regions of Yakutia, in contrast to the southern areas discussed above.

This low prevalence was confirmed by another study conducted in 2005–2006 [

12], which reported the anti-HCV prevalence of only 1.3 ± 1.3% among 301 representatives of the Evenki ethnic group, who predominantly inhabit the northern territories of Yakutia. In contrast, our 2022 study revealed a markedly higher prevalence in residents of the Momsky district, also located in the Arctic zone and bordering the Abyisky district, with anti-HCV detected in 5.2 ± 2.3% of the examined individuals, that was the highest rate among all groups included in

Table 2. The reasons for this sharp increase remain unclear and require further investigation.

Similarly, the increase in anti-HCV prevalence over time was observed in the Republic of Dagestan (North Caucasus). In 2019–2020 our study found the anti-HCV prevalence of 1.8% in this region (

Table 2), whereas an earlier investigation of 10,682 blood donor samples collected in 1994–1996 reported a significantly lower rate of 0.9 ± 0.2% (p-value < 0.01) [

22]. One explanation for this difference may be that during the earlier period, the Republic of Dagestan had probably not yet experienced the surge in hepatitis C incidence that peaked in the Russian Federation in the late 1990s [

21,

23]. Additionally, donor cohorts (such as a studied in the cited investigation) typically have lower morbidity from parenterally transmitted infections than the general population [

23].

Overall, if we assume that the volunteer groups examined in our study are at least partially representative of the conditionally healthy population of the Russian Federation (taking into account the limitations discussed further in the “Discussion” section) it can be concluded that the proportion of anti-HCV carriers in the country has significantly declined over the past 10–12 years. In the combined group of volunteers studied in 2008 (4,764 individuals from five regions differing in economic, geographic, and climatic characteristics), the mean prevalence of anti-HCV was 2.6 ± 0.5% (see bottom lines of

Table 2). By 2018–2022 (37,291 participants from ten regions), this average prevalence had significantly decreased to 1.9 ± 0.1% (

Table 2, p-value < 0.01). However, as illustrated by the examples of rising anti-HCV prevalence in some regions, it cannot yet be concluded that the overall downward trend is consistent or stable across the entire country. This uncertainty is also reflected in the slow and gradual decline in the official number of newly registered cases of hepatitis C over the years (

Figure 1), that is discussed in the following section.

3.3. Correlation Between Hepatitis C Incidence and Anti-HCV Prevalence in Regional Groups

The pronounced regional heterogeneity described above is also reflected in the officially reported incidence rates of hepatitis C.

Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of long-term cumulative incidence, including both acute hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis C, while

Supplementary Table A-2 provides detailed data on the incidence in the surveyed regions for the year in which the samples were collected, presented separately for acute hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis C.

The data show that hepatitis C incidence rates do not always correspond to the prevalence of anti-HCV. For example, Saint Petersburg has consistently recorded the highest incidence of hepatitis C in the Russian Federation, 70 to 90 cases per 100,000 population annually (including both acute hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis C). However, the prevalence of anti-HCV in this region was among the lowest, at only 1.4% (

Table 2). Similarly high incidence rates were reported in Novosibirsk Region (50–90 per 100,000 annually), despite a moderate anti-HCV prevalence of 1.9%. In Moscow, where the prevalence of anti-HCV was low (1.2%), the long-term incidence of hepatitis C remained at 35–55 cases per 100,000 annually, exceeding the national average of 30–40 per 100,000 (

Figure 1).

In contrast, in the Republic of Dagestan, the incidence of hepatitis C has remained below 10 per 100,000 annually for more than a decade, yet the prevalence of anti-HCV was 1.8%—comparable to that of Novosibirsk Region, despite much higher incidence rate there.

Formal correlation analysis using the two-tailed Spearman rank test revealed no statistically significant association between anti-HCV prevalence and the regional incidence of either acute or chronic hepatitis C in the year of sample collection, or with their combined incidence. In all cases, correlation coefficients (r) ranged from –0.12 to –0.01, with corresponding p-values between 0.63 and 0.95 (see

Supplementary Table A-2).

3.4. Dynamics of Anti-HCV Prevalence in Age Groups

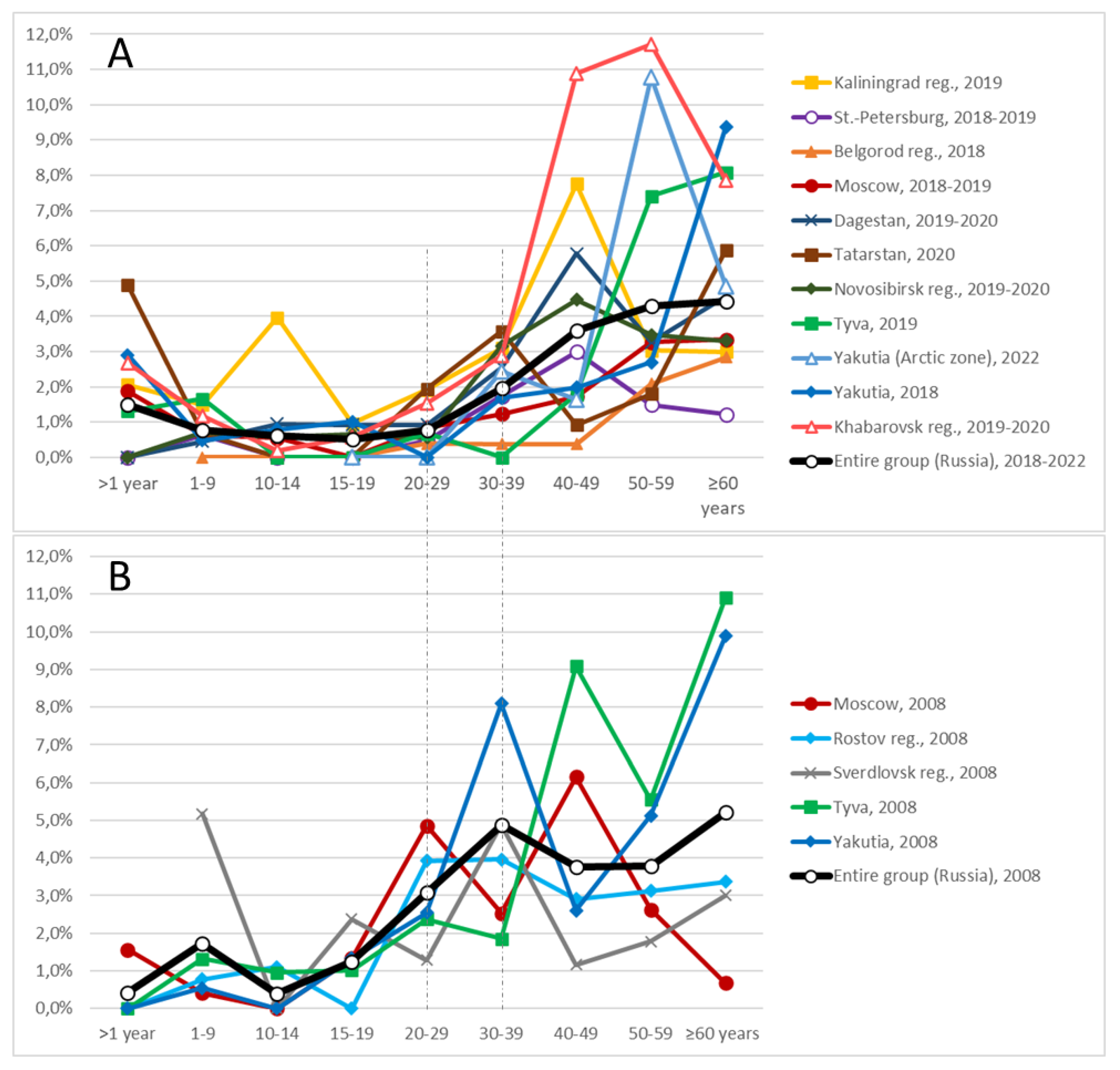

Supplementary Table A-1 presents data on the anti-HCV prevalence among participants in the following age categories: under 1 year, 1–9 years, 10–14 years, 15–19 years, 20–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and 60 years or older, across the surveyed regions. Based on these data, age-dependent prevalence curves were constructed and are shown in

Figure 2 (A: groups surveyed in 2018–2022; B: groups surveyed in 2008).

The graphs clearly demonstrate that anti-HCV prevalence increases with age. In the younger age groups, the proportion of positive carriers remains consistently low. Among participants aged 1 to 19 years, anti-HCV prevalence in almost all regions remained below 1%. Minor deviations from this trend, likely representing random fluctuations, were observed in the 1–9-year age group in Sverdlovsk Region (2008) and in the 10–14-year age group in Kaliningrad Region (2019) (

Figure 2).

A marked increase in anti-HCV prevalence begins in adulthood. In the 2008 cohort, this increase occurred starting from the 20–29-year age group, whereas in the 2018–2022 cohort it was delayed until the 30–39-year age group. This shift is evident not only visually in the graphs but is also supported by statistical analysis. For example, in the entire 2008 group (depicted as the thick black line in

Figure 2B), the differences in prevalence between adjacent younger age groups (for example, <1 year vs. 1–9 years, 1–9 years vs. 10–14 years, 10–14 years vs. 15–19 years) were not statistically significant. However, a significant difference was observed between the 15–19-year age group and the 20–29-year age group (1.2 ± 0.9% vs. 3.1 ± 1.5%, p-value < 0.05;

Supplementary Table A-1).

In contrast, for the 2018–2022 cohort, the first statistically significant increase occurred between the 20–29-year age group and the 30–39-year age group (0.8 ± 0.2% vs. 2.0 ± 0.3%, p-value < 0.01;

Supplementary Table A-1). No significant increases were observed in age groups younger than 20 years, with the exception of the <1-year group, which is discussed additionally below. Another statistically significant rise was observed after the age of 39 years: in the 40–49-year age group, anti-HCV prevalence reached 3.6 ± 0.6%, compared with 2.0 ± 0.3% in the 30–39-year age group (p-value < 0.01;

Supplementary Table A-1). Beyond the age of 49 years, changes in prevalence occurred more gradually (

Figure 2A).

As noted previously, in several regions surveyed in 2018–2022—including Kaliningrad Region, Moscow, Tatarstan, Yakutia (non-Arctic zone), and Khabarovsk—an unusually high proportion of anti-HCV carriers was identified among children younger than one year (

Figure 2 and

Table 2). Moreover, in the entire 2018–2022 cohort, the prevalence of anti-HCV among infants younger than one year was 1.5 ± 0.8% (

Table 2, line 17), which was significantly higher than the prevalence among children aged 1–9 years (0.8 ± 0.2%; p-value < 0.05). Since no reports of hepatitis C outbreaks specifically affecting newborns in the Russian Federation were identified, we believe that this elevated prevalence of antibodies in infants is most likely the result of passive transfer of maternal antibodies from anti-HCV-positive mothers. Supporting this interpretation, the prevalence of anti-HCV among infants in the regions mentioned (ranging from 1.9% to 2.9%, and reaching as high as 4.9% in Tatarstan) closely mirrored the prevalence observed among women of childbearing age (30–39 years) in the same regions (0.7–3.7%;

Supplementary Table A-2).

The absence of a similar peak in the <1-year age group in the 2008 data may be explained by the fact that, at that time, the number of women infected with the HCV (or carrying anti-HCV antibodies) who had recently given birth was likely too low for their infants to be represented in the study sample. In any case, based on the trends illustrated in

Figure 2, maternal antibodies appear to persist in newborns for approximately one year.

3.5. Anti-HCV Prevalence in Men and Women

Table 2 presents the anti-HCV prevalence separately for men and women in each surveyed regional group. More detailed information, including the number of male and female anti-HCV carriers in specific age groups, is provided in

Supplementary Table A-2.

In all regional groups surveyed in 2008, no statistically significant differences in anti-HCV prevalence between men and women were observed (

Table 2). On average, in the combined 2008 cohort, anti-HCV prevalence was 2.6 ± 0.7% among men and 2.7 ± 0.6% among women.

In contrast, in many of the regional groups surveyed during 2018–2022, the prevalence of anti-HCV was noticeably higher among men compared with women. Statistically significant differences were observed in the following groups: Saint Petersburg (2.4% versus 0.9%, p-value < 0.01), Belgorod (1.6% versus 0.7%, p-value < 0.05), Moscow (2.2% versus 0.9%, p-value < 0.01), Dagestan (2.2% versus 1.3%, p-value < 0.05), and Khabarovsk (4.2% versus 2.4%, p-value < 0.01). In the remaining regions, differences between male and female cohorts were not statistically significant (

Table 2).

In the entire 2018–2022 cohort, anti-HCV prevalence among men (2.5±0.2%) was significantly higher than among women (1.5±0.2%, p-value < 0.01;

Table 2). Although the identification of gender-specific risk factors for anti-HCV carriage was beyond the scope of this study, the observed data support the conclusion that, in contemporary Russian society, men are at a higher risk of infection with the HCV compared with women.

3.6. Results of PCR Testing

Data on participants who tested positive for HCV RNA by PCR are presented in

Table 2. In the vast majority of cases, individuals who were PCR-positive for HCV RNA were also positive for antibodies to the HCV. That was expected, since PCR testing in this study was primarily conducted for samples that were seropositive in anti-HCV screening and confirmation assays.

However, in a number of large regional groups surveyed between 2018 and 2020—specifically Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Dagestan, Novosibirsk, and Khabarovsk—PCR testing was also performed on anti-HCV-negative samples using pooled sample analysis (ten samples per pool). In total, 30,232 anti-HCV-negative samples were tested in this manner, which resulted in the detection of 30 additional HCV RNA-positive sera (0.1%). These RNA-positive individuals are not distinguished in

Table 2 from those identified through PCR testing of anti-HCV-positive samples.

Notably, all but one of these “seronegative” HCV RNA-positive samples were positive for antibodies to the hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBcAg), a serological marker of chronic or past hepatitis B virus infection, and lacked any other serological markers of parenterally transmitted hepatitis viruses (that is, they were negative for hepatitis B surface antigen—HBsAg, negative for antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen—anti-HBs IgG, and negative for antibodies to the HCV). Further details on the serological profiles of the studied groups with respect to hepatitis B virus infection can be found in our previous publication [

24].

Among individuals who were positive for anti-HCV, the proportion of those who were also positive for HCV RNA ranged from 20% to 62% across the different regional groups (

Table 2). When comparing the aggregated data from the 2008 and 2018–2022 cohorts, this proportion was similar: 27.8% and 32.5%, respectively. The relatively high number of individuals who were anti-HCV-positive but HCV RNA-negative is most likely explained by spontaneous clearance of the virus, which occurs in approximately 20–40% of individuals following an acute HCV infection [

25].

3.7. Estimation of the Current Number of Individuals Carrying Anti-HCV in the Russian Federation

Attempts to estimate the number of individuals carrying markers of infectious diseases at the national level based on limited sample data are, by their nature, speculative. The reasons for this are discussed in detail in the following section. Nevertheless, such estimates remain a common practice among epidemiologists and can be valuable, particularly for planning the economic resources required for the identification and treatment of infected individuals. In this context, we present our own estimate, while acknowledging its inherent limitations.

Supplement A contains both our complete experimental dataset and relevant demographic statistics, allowing other researchers to perform more refined calculations if new or additional information becomes available.

In the combined group studied in 2018–2022 (37,291 participants; see

Table 2 and

Table 3), the overall prevalence of antibodies to the HCV was found to be 1.9 ± 0.1%. Applying this prevalence rate to the total population of the Russian Federation—146.75 million people in 2019 [

26] (the last pre-COVID-19 year used throughout this discussion)—yields an estimated 2.79 million individuals carrying antibodies to the HCV. This figure corresponds closely to one of the expert estimates cited in the Introduction section, namely 2.7 million [

9].

However, our initial estimate, based directly on the prevalence observed in the experimental sample, is clearly biased. As shown in

Table A-1 (Supplement A), the age and sex composition of our surveyed groups differed substantially from that of the actual population. For example, individuals aged 30–39 years comprised 18% of the actual population in the Moscow region (including the city of Moscow) in 2019 [

26], but accounted for 36% of our surveyed group from 2018–2019 (

Tables A-1 and A-3). In the observed group of Dagestan, children aged 1–9 years represented 23% of the sample, compared with only 15% of the Republic of Dagestan’s actual population. The overall male-to-female ratio in the 2018–2022 sample was 1:1.3 (

Table 2), whereas the national ratio in 2019 was 1:1.15 [

26], and similar discrepancies were present in other regions.

Given that, as demonstrated in

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5, the ant-HCV prevalence varies significantly depending on age and sex, any estimate derived from the experimental sample must be adjusted to reflect the true demographic structure of the Russian population.

To refine our estimate, we applied the age-specific and sex-specific prevalence rates of antibodies to the HCV observed in our experimental sample to the actual demographic structure of each region. When this approach was applied to all regions included in the 2019–2022 study—covering a total population of 42 million in 2019—it yielded an estimated 937,000 individuals carrying antibodies to the HCV (see

Table A-3 in Supplement A for detailed calculations). This approach, however, does not allow the calculation of meaningful aggregated confidence intervals, as their combination would result in an excessively broad range. Additionally, we excluded data from the Momsky District of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) from this calculation due to its small population size (see

Table A-3 in Supplement A).

This refined method produces a higher estimated prevalence of antibodies to the HCV—2.2% (937,000 individuals out of 42 million)—compared with the prevalence observed directly in the experimental sample, which was 1.9 ± 0.1% (713 carriers out of 37,291 participants; see

Table 2). We believe that this higher estimate is more appropriate for the purposes of planning national HCV control strategies, particularly given the methodological soundness of the adjustment.

If we assume that this 2.2% prevalence is representative of the entire Russian Federation—implying that the regions not included in the study are epidemiologically similar to those surveyed—the estimated number of individuals carrying antibodies to the HCV nationwide would be approximately 3.23 million. This figure is consistent with previously published estimates, which range from 2.7 million to 4.5 million [

9,

10].

4. Discussion

The present work—or more precisely, a set of studies conducted in different years but united by a common objective and presented here under a single title—has several methodological limitations. These limitations are characteristic of many seroepidemiological studies and are primarily associated with methodological simplifications that should be explicitly acknowledged:

1. Enrollment of participants in the study was based on inviting apparently healthy volunteers rather than employing a randomized sampling strategy that would statistically represent different social, economic, and behavioral strata of the population. Such an approach may have led to an underestimation of the anti-HCV prevalence in the surveyed groups. Volunteer-based recruitment usually does not adequately capture marginalized or high-risk groups, which, although relatively small in number, often have a disproportionately high prevalence of HCV infection [

21]. Furthermore, the primary aim of the present work was to identify asymptomatic anti-HCV carriers “hidden” within the ostensibly healthy population. For this reason, individuals with a known diagnosis of HCV infection or with a history of other viral hepatitis or parenteral infections were deliberately excluded (self-reported or guards-reported hepatitis history served as the exclusion criterion for participants). Consequently, these individuals were not included in the statistical analyses of regional prevalence rates.

2. The regional cohorts presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2, although all derived from the “conditionally healthy” population, are not epidemiologically homogeneous with one another. While an effort was made to recruit a balanced distribution of participants across age and sex groups to ensure adequate statistical power for subgroup analysis, it was not feasible to perfectly match the demographic structure of the study samples to that of the actual population in each region. Moreover, it was not possible to refuse participation to volunteers who wished to be included, even if their demographic subgroup was already sufficiently represented. As a result, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table A-1 (Supplement A), the representation of specific age and sex categories varied between regions (see also

Section 3.7). This demographic imbalance should be considered when interpreting and comparing prevalence estimates across regions.

3. In this study, the primary analytical focus was on the prevalence of antibodies to the HCV, with the assumption that this marker correlates proportionally with the overall prevalence of HCV infection in the population. The results of PCR testing for HCV RNA were used only as information to indicate the proportion of “active”, that is, replicative, infections. As shown in

Table 2, the proportion of anti-HCV-positive samples that were also positive for HCV RNA varied between 30% and 70% depending on the region. As discussed in

Section 3.6, this discrepancy is most likely attributable to spontaneous clearance of the virus, which occurs in approximately 20–40% of individuals following acute infection [

25]. However, it cannot be ruled out that some of the PCR-negative results could be explained by the possible hyper sensitivity of the ELISA assays used, or conversely, by the limited sensitivity of the PCR assays applied in certain cases. In any case, prevalence estimates based solely on anti-HCV seropositivity tend to overstate the proportion of individuals with active, chronic infection.

These limitations inevitably complicate the determination of the absolute number of individuals infected with HCV in the Russian Federation as a whole and in individual regions. Nevertheless, the consistent application of the same methodology across all study groups allows for the assessment of temporal trends within the same population (where multiple time points are available) and enables qualitative comparison between different regions. This approach has yielded several important and noteworthy findings, which are presented above and elaborated upon here.

The prevalence of antibodies to the HCV was investigated in various population groups by direct serological testing of blood samples from volunteers. Between 2018 and 2022, a total of 37,291 unique samples were collected from the conditionally healthy population of all ages in ten geographical regions of the Russian Federation. Additionally, 4,764 samples collected in 2008 were analyzed. Based on this dataset, the average prevalence of anti-HCV was estimated at 1.9 ± 0.1% for the 2018–2022 cohort and 2.8 ± 0.5% for the 2008 cohort (

Table 2).

Notable regional differences in anti-HCV prevalence were found. In the 2018–2022 cohort, the lowest prevalence values were recorded in the Belgorod region, Moscow, and Saint Petersburg (1.1–1.4%), while the highest values were recorded in Khabarovsk region and the Arctic zone of Yakutia (3.4–5.2%). These differences were statistically significant (

Table 3).

Overall, the results indicate a general downward trend in HCV prevalence over time. However, this trend is not universal: in the Dagestan and the Arctic zone of Yakutia, the proportion of anti-HCV-positive individuals in 2018–2020 exceeded the levels reported in earlier studies by other authors.

An important finding was the absence of correlation between anti-HCV prevalence and the officially registered incidence of hepatitis C (see

Section 3.3). This suggests that official incidence rates are not reliable indicators of the true morbidity of infection in the population but instead reflect the extent of diagnostic testing coverage in different regions.

Substantial differences were also observed in the prevalence of anti-HCV across age groups. In most younger age groups examined in 2018–2022, the prevalence did not exceed 1%. However, starting from approximately 30 years of age, prevalence increased markedly to 2–4%, and in older age groups, it reached 4–10% (

Figure 2A,

Table A-1). In the 2008 cohort, this increase was already evident starting from the 20–29-year age group. It is plausible that individuals in this cohort were infected during adolescence or early adulthood in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when predominant risk factors (especially injection drug use) were more widespread [

21,

23]. Children and adolescents under 20 years of age examined in 2008, by contrast, likely had significantly lower lifetime exposure to these risk factors.

In the 2018–2022 cohort, the age-related increase in anti-HCV prevalence has shifted by approximately one decade compared to the 2008 data. This suggests that the same cohort of individuals likely infected in the late 1990s to early 2000s had aged by ten years and were now represented in older age groups. Meanwhile, individuals under 30 years of age in 2018–2022 continued to show relatively low infection rates, suggesting that high-risk factors prevalent among young people in the 1990s are no longer as influential for the younger generation. This shift may reflect positive changes in public health and behavioral patterns.

At that, in contemporary Russian society, certain as yet unidentified risk factors appear to be disproportionately associated with the male sex. In the entire 2018–2022 cohort, the prevalence of anti-HCV among men was significantly higher than among women (2.5% versus 1.5%; see

Section 3.5). No such sex-related difference was detected in the 2008 cohort, suggesting that before 2008, there were no risk factors disproportionately affecting one sex.

Taken together, these findings underscore the pronounced heterogeneity in the HCV epidemiology across the Russian Federation. Seroepidemiological studies such as ours help to identify demographic and regional groups most affected by the infection, which should be prioritized in prevention and control programs. Based on the age- and sex-specific patterns identified, it can be concluded that in modern Russia (2018–2022), the majority of infected individuals are men over 30 years of age (

Figure 2A,

Table 2). Detailed numerical data are provided in

Table A-1 (Supplement A), which can be regarded not only as reference material but also as a basis for designing targeted public health interventions.

In accordance with the aims outlined in the Introduction, diagnostic screening followed by antiviral treatment would be most effective if directed at groups with the highest concentration of seropositive individuals. Adjusting for the contribution of different age and sex cohorts in the study sample, we estimated that the total number of anti-HCV carriers in modern Russia is approximately 3.23 million individuals. As demonstrated in our study, only about one-third of individuals testing positive for anti-HCV also test positive for the HCV RNA and thus have a clinical indication for antiviral therapy [

5,

6].

The remaining anti-HCV-positive but RNA-negative individuals require only observation. According to current Russian guidelines, such individuals undergo two polymerase chain reaction tests six months apart, and if both results are negative, they are they are considered recovered and removed from the viral hepatitis register [

27].

Based on our estimates, approximately 1.1 million people in the Russian Federation require antiviral treatment. At an average cost of 200,000–300,000 rubles per course (equivalent to USD 2,000–3,000), the total projected cost of therapy would amount to 200–300 billion rubles (USD 2–3 billion). For comparison, official estimates place the annual economic burden of chronic hepatitis C in Russia at 65–75 billion rubles [

7,

8]. Therefore, the economic benefits of implementing large-scale screening and treatment programs could become apparent within five to ten years. A significant step in this direction is the inclusion of anti-HCV screening in the adult preventive medical examination program beginning in 2024 [

28] as well as the launch in 2024 of the federal project “Combating Hepatitis C” within the framework of the national program “Long and Active Life” [

29], which includes a substantial expansion of access to antiviral treatment funded by the federal budget.

5. Conclusions

In this large-scale seroepidemiological investigation, we examined the prevalence of antibodies to the HCV across diverse age, sex, and regional cohorts of the Russian Federation. The analysis was based on more than 42,000 serum samples collected over a fourteen-year period, from 2008 to 2022. This comprehensive dataset allowed for the assessment of both cross-sectional and temporal patterns in the HCV spreading.

Our results demonstrated substantial variation in the prevalence of antibodies to the hepatitis C virus between different geographic regions and demographic groups. These findings confirm the pronounced heterogeneity of the HCV epidemiology within the Russian Federation. The data indicate a gradual overall decline in the prevalence of anti-HCV virus over time; however, this trend was not consistent across all surveyed regions, with some areas showing stable or even increasing prevalence rates.

By applying an adjustment for the actual age and sex distribution of the Russian population, we estimated that approximately 3.23 million individuals in the country are positive for antibodies to the HCV. Of these, roughly one-third are expected to have detectable HCV RNA and, therefore, meet clinical criteria for antiviral therapy. This proportion translates to an estimated 1.1 million individuals who require antiviral treatment.

These results highlight the importance of prioritizing targeted screening and treatment interventions for demographic groups with the highest prevalence rates. In particular, the findings indicate that men over 30 years of age constitute a key high-risk group in modern Russia. The integration of anti-HCV screening into the national program of preventive medical examinations for adults, along with the significant expansion of treatment programs beginning in 2024, represents a timely and strategically important step toward reducing the burden of HCV infection, improving population health outcomes, and ensuring a more efficient allocation of healthcare resources.

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, File Supplement A (Table A1: Prevalence of the HCV Markers Across Sex and Age Groups of the Studied Regions; Table A2: Correlations between the prevalence of anti-HCV in the study groups and the incidence of hepatitis C in the corresponding regions; E; Table A3: Estimated number of anti-HCV carriers by age and sex groups in the studied regions of Russia, adjusted for their contribution to the actual population structure).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.M., V.A.G., A.P.T. and K.K.K.; methodology, V.A.M., V.A.G., V.P.C. and D.A.K.; validation, T.A.S.; formal analysis, Y.V.S.; investigation, O.V.I., D.A.K., A.A.P., E.P.M. and E.N.B.; resources, I.N.T. and Y.V.S.; data curation, O.V.I. and A.A.P.; writing—original draft, V.A.M., V.P.C. and K.K.K.; writing—review and editing, V.A.G., S.V.N., T.A.S. and A.L.G.; visualization, V.A.M. and O.V.I.; supervision, S.V.N., A.P.T., A.L.G, K.K.K. and M.I.M.; project administration, V.A.M. and A.P.T.; funding acquisition, V.A.G., A.P.T., A.L.G. and M.I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study of participants from Moscow and the Moscow Region, Saint Petersburg and the Leningrad Region, the Republic of Dagestan, the Novosibirsk Region, and the Khabarovsk Region during the period 2018–2020 was funded by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation under the state contract “Monitor-Bio.” The participation of V. Manuilov and S. Netesov was supported within the framework of the state assignment for research and development funding at Novosibirsk State University (Project No. FSUS-2025-0012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Independent Interdisciplinary Ethics Committee for the Ethical Review of Clinical Research, Moscow, Russia (Approval No. 17, November 16, 2019), and by the Ethics Committee of the Mechnikov Research Institute for Vaccines and Sera, Moscow, Russia (Approval No. 1, February 28, 2018). The study conducted in 2008 was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chumakov Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis, Moscow, Russia (Approval No. 6, April 1, 2008).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in

File Supplement A. Any additional data are available on request from the corresponding author: victormanuilov@yandex.ru.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to D. Ogarkova, T. Remizov, A. Zakharova, N. Soboleva, A. Karlsen, V. Kichatova, V. Klushkina, E. Malinnikova, F. Asadi-Mobkharan, M. Lopatukhina, E. Chub, A. Nozdracheva, R. Adgamov for their professional support and assistance during all stages of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HCV |

hepatitis C virus |

| anti-HCV |

antibodies to hepatitis C virus |

| RNA |

ribonucleic acid |

| PCR |

polymerase chain reaction |

| DAA |

direct-acting antiviral (therapy) |

| CHC |

chronic hepatitis C |

| AHC |

acute hepatitis C |

| IgG |

immunoglobulin class G |

| IgM |

immunoglobulin class M |

| M |

male(s) |

| F |

female(s) |

| ELISA |

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| CI |

confidence interval |

References

- Falade-Nwulia, O.; Suarez-Cuervo, C.; Nelson, D.R.; Fried, M.W.; Segal, J.B.; Sulkowski, M.S. Oral direct-acting agent therapy for hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, D.P.; Skrip, L.A.; Bruce, R.D.; Vilarinho, S.; Elbasha, E.H.; Galvani, A.P.; Townsend, J.P. The impact of enhanced screening and treatment on hepatitis C in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrift, A.P.; El-Serag, H.B.; Kanwal, F. Global epidemiology and burden of HCV infection and HCV-related disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549981 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1170–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, J.T.; Diepolder, H.M.; Zachoval, R.; Gruener, N.H.; Jung, M.C.; Ulsenheimer, A.; Schraut, W.W.; Schirren, C.A.; Waechtler, M.; Backmund, M.; Pape, G.R. Acute hepatitis C: high rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing. State Report on the Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare of the Population in the Russian Federation in 2023; Rospotrebnadzor: Moscow, Russia, 2024; 364p, (In Russian). Available online: https://rospotrebnadzor.ru/documents/details.php?ELEMENT_ID=27779 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing. State Report on the Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare of the Population in the Russian Federation in 2024; Rospotrebnadzor: Moscow, Russia, 2025; 424p, (In Russian). Available online: https://rospotrebnadzor.ru/documents/details.php?ELEMENT_ID=30171 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- The CDA Foundation. Hepatitis C—[Russian Federation]. Lafayette, CO: CDA Foundation. 2024. Available online: https://cdafound.org/polaris-countries-database/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzin, S.N.; Pavlov, N.N.; Semenov, S.I.; Krivoshapkin, V.G.; Indeeva, L.D.; Savvin, R.G.; Nikolaev, A.V.; Chemezova, R.I.; Kozhevnikova, L.K.; Lavrov, V.F.; Alatortseva, G.; Kuzina, L.E.; Sadikova, N.V.; Zverev, V.V. The spread of viral hepatitis among various population groups in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). J. Microbiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 2004, 1, 18–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zotova, A.V. Parenteral Viral Hepatitis in South Yakutia. Ph.D. Thesis, Central Research Institute for Epidemiology of the Rospotrebnadzor, Moscow, Russia, 2010. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Kyuregyan, K.K.; Isaeva, O.V.; Kichatova, V.S.; Karlsen, A.A.; Lopatukhina, M.A.; Potemkin, I.A.; Asadi Mobarhan, F.A.; Malinnikova, E.Y.; Krasnova, O.G.; Ivanov, I.B.; Rukosueva, E.V.; Znoyko, O.O.; Yushchuk, N.D.; Mikhailov, M.I. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C markers among the apparently healthy population of the Kaliningrad Region. Epidemiol. Infect. Dis. Curr. Probl. 2020, 10, 13–20. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyuregyan, K.K.; Malinnikova, E.Y.; Soboleva, N.V.; Isaeva, O.V.; Karlsen, A.A.; Kichatova, V.S.; Potemkin, I.A.; Schibrik, E.V.; Gadjieva, O.A.; Bashiryan, B.A.; Lebedeva, N.N.; Serkov, I.L.; Yankina, A.; Galli, C.; Mikhailov, M.I. Community screening for hepatitis C virus infection in a low-prevalence population. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soboleva, N.V.; Karlsen, A.A.; Kozhanova, T.V.; Kichatova, V.S.; Klushkina, V.V.; Isaeva, O.V.; Ignatieva, M.E.; Romanenko, V.V.; Oorzhak, N.D.; Malinnikova, E.Y.; Kuregyan, K.K.; Mikhailov, M.I. The prevalence of the hepatitis C virus among the conditionally healthy population of the Russian Federation. J. Infectology 2017, 9, 56–64. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichatova, V.S.; Kyuregyan, K.K.; Karlsen, A.A.; Potemkin, I.A.; Asadi Mobarkhan, F.A.; Isaeva, O.V.; Lopatukhina, M.A.; Malinnikova, E.Y.; Kravchenko, I.E.; Znoyko, O.O.; Yuschuk, N.D.; Mikhailov, M.I. Frequency of detecting markers of hepatitis C among the conditionally healthy population of Tatarstan Republic. Therapy 2022, 2, 59–66. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saryglar, A.A.; Isaeva, O.V.; Kichatova, V.S.; Lopatukhina, M.A.; Potemkin, I.A.; Karlsen, A.A.; Il’chenko, L.Y.; Kyuregyan, K.K.; ikhailov, M.I. Dynamics of the prevalence of hepatitis C infection markers among the conditionally healthy population of the Republic of Tyva. J. Infectology 2023, 15, 95–101. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichatova, V.S.; Lopatukhina, M.A.; Potemkin, I.A.; Asadi Mobarkhan, F.A.; Isaeva, O.V.; Chanyshev, M.D.; Glushenko, A.G.; Khafizov, K.F.; Rumyantseva, T.D.; Semenov, S.I.; Kyuregyan, K.K.; Akimkin, V.G.; Mikhailov, M.I. Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis in the Indigenous Populations of the Arctic Zone of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Microorganisms 2024, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyuregyan, K.K.; Soboleva, N.V.; Karlsen, A.A.; Kichatova, V.S.; Potemkin, I.A.; Isaeva, O.V.; Lopatukhina, M.A.; Malinnikova, E.Y.; Gadjieva, O.V.; Bashiryan, B.A.; Lebedeva, N.N.; Serkov, I.L.; Ignatieva, M.E.; Sleptsova, S.S.; Znoyko, O.O.; Yushchuk, N.D.; Mikhaylov, M.I. Dynamic changes in the prevalence of hepatitis C virus in the general population in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) over the last 10 years. Infect. Dis. News, Opin., Train. 2019, 8, 16–26. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, O.V.; Khryanin, A.A.; Teinina, T.R.; Krivenchuk, N.A.; Zimina, I.Y. Hepatitis B and C seroprevalence in Novosibirsk, western Siberia. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2001, 77, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shustov, A.V.; Kochneva, G.V.; Sivolobova, G.F.; Grazhdantseva, A.A.; Gavrilova, I.V.; Akinfeeva, L.A.; Rakova, I.G.; Aleshina, M.V.; Bukin, V.N.; Orlovsky, V.G.; Bespalov, V.S.; Robertson, B.H.; Netesov, S.V. Molecular epidemiology of the hepatitis C virus in Western Siberia. J. Med. Virol. 2005, 77, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdourakhmanov, D.T.; Hasaev, A.S.; Castro, F.J.; Guardia, J. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of hepatitis C virus infection in the Russian Republic of Daghestan. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 14, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakhgil’dyan, I.V.; Mikhailov, M.I.; Onishchenko, G.G. Parenteral Viral Hepatitis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Prevention; State Educational Institution VUNMC of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2003; 384p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Asadi Mobarkhan, F.A.; Manuylov, V.A.; Karlsen, A.A.; Kichatova, V.S.; Potemkin, I.A.; Lopatukhina, M.A.; Isaeva, O.V.; Mullin, E.V.; Mazunina, E.P.; Bykonia, E.N.; Kleymenov, D.A.; Popova, L.I.; Gushchin, V.A.; Tkachuk, A.P.; Saryglar, A.A.; Kravchenko, I.E.; Sleptsova, S.S.; Romanenko, V.V.; Kuznetsova, A.V.; Solonin, S.A.; Semenenko, T.A.; Mikhailov, M.I. Kyuregyan, K.K. Post-vaccination and post-infection immunity to the hepatitis B virus and circulation of immune-escape variants in the Russian Federation 20 years after the start of mass vaccination. Vaccines 2023, 11, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aisyah, D.N.; Shallcross, L.; Hully, A.J.; O’Brien, A.; Hayward, A. Assessing hepatitis C spontaneous clearance and understanding associated factors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat). Population Size of the Russian Federation by Gender and Age as of January 1, 2019. Statistical Bulletin. Available online: https://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_reg_pop_y.php?year=2019®ion=0 (accessed on 18 August 2025). (In Russian).

- Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing. Sanitary Rules and Regulations 3.3686-21: Sanitary and Epidemiological Requirements for the Prevention of Infectious Diseases. Approved 28 January 2021. (In Russian).

- Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Order No. 378n of July 19, 2024 on Amendments to the Procedure for Preventive Medical Examination and Dispensary Monitoring Approved by Order No. 404n of April 27, 2021. (In Russian).

- Government of the Russian Federation. Decree No. 1888 of 25 December 2024 “On Amendments to the Government Decree No. 1640 of 26 December 2017.” Available online: https://minzdrav.gov.ru/documents/9819-postanovlenie-pravitelstva-rossiyskoy-federatsii-ot-25-12-2024-1888 (In Russian).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).