Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Government as an Institution and Sector for Research

2.1. Government Effectiveness: A Declining Trust

- -

- In the United States, the proportion of Americans who reply that they "trust the government in Washington to do the right thing" some or most of the time has fallen steadily from 70 percent in1966, to 25 percent in 1992 (Putnam, 1995), and to only 15 percent in 1995 (Nye, Zelikow, & King 1997).

- -

- Public confidence in government has also declined in Canada (Zussman, 1997), some European countries (OECD 2011; Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011), New Zealand (Barnes and Gill 2000) and other nations.

- -

- As summarized in The Trust Issue of Oxford Government Review in 2016, the developed countries’ populations are fed up with globalization for the benefit of the few, letting trade drive away jobs, and encouraging immigration so as to provide cheaper labor and to fill skills-gaps without having to invest in training. As a result, the ‘anti-government’, ‘anti-expert’, ‘anti-immigration’ movements are rapidly gathering support (Woods, 2016). So bridging the gap became a challenge in itself between citizens and their governments (Woods, 2017).

- -

- Over the same period, a wave of ongoing governmental reform has washed over much of the developed world (Kettl, 2002; Kickert, 1997; Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011).

- -

- Tax collection is emphasized but citizens don’t get our money’s worth.

- -

- Some government agencies pay scandalous prices for common goods, and there are million-dollar overruns on government contracts (inefficiency and corruption).

- -

- The nation’s public infrastructure (bridges, roads, etc.) is deteriorating in spite of road taxes (and we have roads without bridges and vice versa).

- -

- Public agencies are often slow and inflexible because of excessive bureaucracy and rules.

- -

- Public employees are overprotected even in the face of incompetence or unethical behavior.

- -

- Public schools and university failures lead to poor education that leads to poor workforce and that lead to poor human capacity of the nation.

- -

- Poorer citizens are given inadequate help to improve their conditions and to escape the cycle of poverty.

- -

- System problems create long waiting times, lost correspondence, dirty streets, and more.

- -

- Inept communications create confusion.

- -

- Lack of responsiveness creates anger, pessimism, distrust, and helplessness.

- -

- Being out of touch with citizenry creates programs doomed for failure and in turn wastes for the whole country and economy.

2.2. State of the Nation and Development: Bangladesh Conundrum

2.3. Development, Governance, and Government Effectiveness

| Governance Indicators | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|

| Voice and Accountability | the extent to which a country's citizens are able to participate in selecting their government; freedom of expression, association, and a free media. |

| Political Stability | the likelihood that the government will be destabilized by unconstitutional or violent means, including terrorism |

| Government Effectiveness | the quality of public services, quality of policy formulation, the capacity of the civil service and its independence from political pressures; |

| Regulatory Quality | the ability of the government to provide sound policies and regulations that enable and promote private sector development |

| Rule of Law | The extent to which agents have confidence in in and abide by the rules of society, including police and courts |

| Control of Corruption | the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests. |

| Indicator | Bangladesh | India | Pakistan | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Bhutan | Maldives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voice and accountability | 31 | 59 | 29 | 39 | 43 | 45 | 26 |

| Political stability and absence of violence | 10 | 14 | 1 | 19 | 50 | 83 | 60 |

| Government effectiveness | 25 | 57 | 29 | 20 | 45 | 70 | 41 |

| Regulatory quality | 22 | 42 | 27 | 24 | 51 | 27 | 35 |

| Rule of law | 31 | 52 | 20 | 20 | 54 | 68 | 36 |

| Control of Corruption | 21 | 47 | 19 | 24 | 48 | 83 | 29 |

| Year | Bangladesh | India | Pakistan | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Bhutan | Maldives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 25 | 55 | 22 | 18 | 51 | 72 | 45 |

| 2012 | 24 | 49 | 26 | 18 | 48 | 69 | 48 |

| 2013 | 24 | 48 | 24 | 18 | 48 | 65 | 45 |

| 2014 | 23 | 45 | 23 | 18 | 56 | 63 | 42 |

| 2015 | 24 | 56 | 28 | 13 | 53 | 68 | 41 |

| 2016 | 25 | 57 | 29 | 20 | 45 | 70 | 41 |

3. Management in Government: Doing More with Less

- -

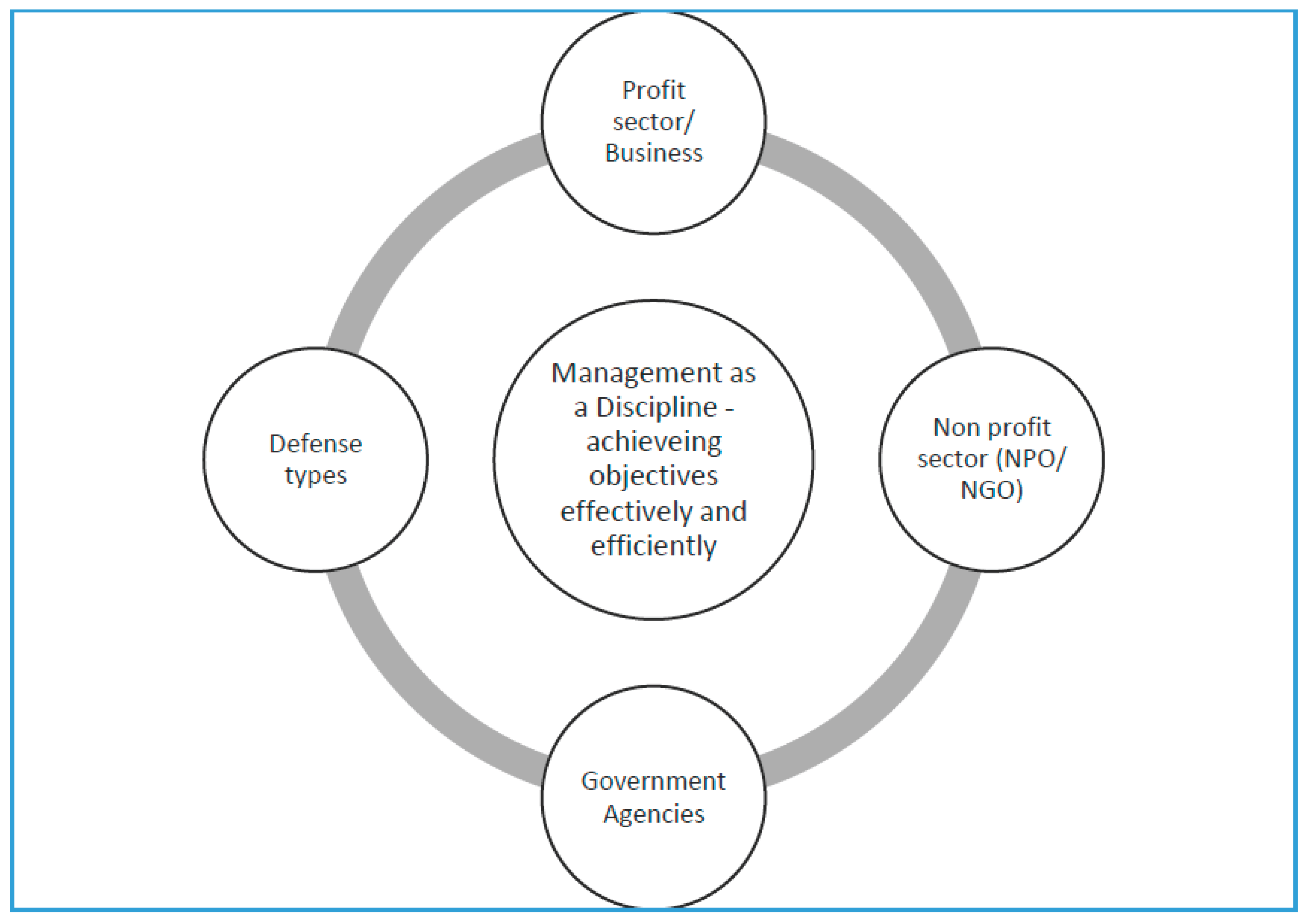

- If it is a business organization, that proposition is easy to conceive - ultimately leading to more profit, more revenue, less cost, more quality, and as a whole, value for shareholders. The objectives of businesses are profit, revenue, market share etc. The resources are made available by shareholders in expectation of return of investment (ROI).

- -

- When it comes to non-profits it may lead to better resource utilization and endowment management for the greater benefit of targeted recipients of the society and value for the society, as a whole. The objectives of NGO/NPO are social welfare, health, education, etc. for poor. The resources are made available by trustees and philanthropists, or CSR funds (corporate social responsibility).

- -

- When it comes to government, the MAD proposition will lead to better government, efficient government, effective government, innovative government, engaged citizenry, and ultimately to better value for the citizens. The dominant objective of government as a whole, governmental units, and agencies is to protect and serve the citizen through various institutional and service delivery mechanism. The resources are made available by state budget and foreign aid, loan and grants, in case of government, and ultimately by citizens.

4. Studying Government from Management Perspective: A Paradigm Shift

- -

- How to make government work better regardless of its political dimensions or party in power

- -

- Given the past and ongoing reforms of government of Bangladesh so far, which are mostly top down, how to develop an alternative, effective, and complementary bottom-up approach to improving management in government agencies for ensuring better citizen service

- -

- What is a theory of government in terms of management in government (MIG), what are the theoretical paradigms of MIG within and beyond the traditional approach of public administration

- -

- What is the nature of management (lack of it) and poor services in government at the agency level (department, directorate, etc.) and at the field level (district, sub-district, union etc.)?

- -

- What are the ongoing initiatives like A2I (digital Bangladesh), GIU, Shebakunjo (service portal), and others – how and whether those are working?

- -

- What are the ongoing programs for different donor programs and work area? What are the status of those?

- -

- What are the experiences and perspectives of bottom level or field officers, at upazila and zila level, about top of the government, how it works, and how it should work from the top? How the policy and structural bottlenecks discourage initiatives or simply, perpetuate mediocre bureaucratic behavior both at the citizen level and at the organizational level?

- -

- What are the root cause and reasons of management bottlenecks of policies, incentives, and implementation at the bottom and at citizen level, according to the field officers at upazila and zila level? What are the structural imperatives at organizational level to make government work better for citizens at the bottom or at service delivery level?

- -

- What can be a framework for thoughts and action, to make meaningful qualitative change at the bottom? What can be a road map for MIG improvement, for political actors and bureaucratic actors?

4.1. Operational Terms: Definitions and Clarifications

- -

- Management: A systematic process involving Planning, Organizing, Leading, and Controlling (POLC) to achieve organizational objectives efficiently and effectively within resource constraints. While the objectives differ across sectors—profit in business, welfare in non-profits, and public value in government—the underlying principle remains the same: creating maximum value with minimum resources.

- -

- Management in Government (MIG): Refers to the application of management principles in public sector institutions. It focuses on improving service delivery, optimizing internal processes, and enhancing decision-making, leadership, coordination, and resource utilization in government agencies. MIG is distinct from traditional public administration in its emphasis on results, citizen orientation, and operational efficiency.

- -

- Government Agencies: The units and offices of government that serves the citizen or interacts with the citizens or are relatively more directly responsible for citizen service delivery and citizen satisfaction. There are different names that co-exists in the government machinery when it comes to different implementing or executing agencies of government functions under different ministries, including PMO. For example, Division – Department – Directorates - Subordinate office – Authority - Board – Corporation – Commission – Bureau – Academy – Center, etc.

- -

- Better Citizen Services: Citizens wants services from government without hassle, harassment. A2I program (Digital Bangladesh) of PMO terms it as less TCV (time, cost, visits) in getting service from government offices. Public mangers should not deny service showing them excuses of rules and regulations. They should facilitate citizens getting the right service in right way without making them move here to there. It needs commitment and know-how from the managers. Getting service is not a privilege, rather a right of the citizens. Providing ‘good service’ is not an option, rather a prerogatives for the managers. This simple idea is better citizen service in this research.

- -

-

Bottom-up Approach: It means two things in this thesis, complementary to each other:

- 1)

- that public managers at the bottom- local offices, can be proactive actors of change and improvement by applying various management concepts, which might be rather appreciated and replicated by the top of the government.

- 2)

- that the TOG (top of government) may develop a mechanism to get the instant and continuous flow of ideas from the bottom of government (BOG), who know their clients, here citizens, from their day to day experience.

Contrary to top-down approach or trickle-down reforms and innovation, bottom up approach give importance to ground level ‘stories’ – experiences of managers at the ground, facing the citizens. If we can consolidate the ‘stories’ and evidences (complex and holistic amalgamation of data in terms of citizens’ and managers’ interactional experience) from different citizen serving units of government, that can help change, improve, reinforce, and redesign of the typical top down policy reforms. - -

- Reforms: Reforms are, simply speaking, effort to redesigning the government structure and processes. Time to time, government take initiative to make government work or at least look good to the citizens. Different reforms commission is formed by government. Donor agencies and international organizations also bring forth their own studies for reform. All these reform efforts end up with piles of recommendations which are good on papers. But many of these reforms do not see the light of full-scale implementation either due to inability of government, inertia of status-quo civil service, or political unwillingness. But still new reforms commissions are needed, and they are commissioned usually with each subsequent change of power in government.

- -

-

Top-down and Trickle-down Approach: The reality of a less developed country like Bangladesh is most of its reforms efforts prescribed, or heavily influenced by developed country public administration or governmental reforms in terms of paradigms, assumptions, preoccupations, and contextual predispositions.Reforms and recommendations are made and celebrated the TOG (top of the government), - ministries and secretariats. Then those reforms start trickling down to divisions, districts, sub-districts, and union level. At each level the thrust of reforms may lose the originality. We, for this research, do not suppose, top-down reforms and associated innovation are all round ineffective. Rather our position is emphasis should be balanced, if not dramatically shifted, in favor of the bottom-up approach, ground view, or worm’s eye view. What does that mean- that will be detailed in the following chapters first through desk research and review of literature, and then through extensive field observation.

- -

- Idea of Management in Government (MIG): The core idea of management as a systematic process of organizational objective achievement, effectively and efficiently, first evolved in private sector as a fully developed construct. Eventually many scholars and practitioners believed that ‘management’ ideas, tools and techniques, can be and should be used in ‘management’ of other types of organizations, including in government. In management in government (MIG), this idea that private sector management can be applied in government, has been termed as New Public Management (NPM). After 1980s, scholars has used this term for the sake of identification of this paradigm, and since then the term has gone through long way of discussion and debates, paving the way for network organizations theory and much touted governance discourse along with other models like New Public administration (NPA), Strategic Management and pubic value model (PVM), Strategic Management, Public Value Management (PVM), Digital and Electronic Government (DEG), Governance, New Governance, etc.

4.2. Core Assumptions of the MIG-BD Paradigm

- MIG is currently weak: Management in government agencies is characterized by excessive rule-following, low responsiveness, and inefficiency. This is evident in public perceptions, media reports, and empirical observations.

- Private sector management is comparatively stronger: Though not without flaws, private sector organizations generally demonstrate clearer goal orientation, better accountability, and more flexible use of tools and resources.

- Political and institutional culture is resistant to change: Entrenched dynastic politics, weak intra-party democracy, and low civic awareness present long-term challenges to systemic reform.

- Educational progress has not translated into governance maturity: Although literacy has improved, quality of education and civic competence remain limited, constraining bottom-up accountability and collective rational choice.

- MIG can still be improved through internal reform: Despite unfavorable macro conditions, strategic application of management tools and leadership development can significantly enhance institutional performance and citizen satisfaction.

- Dual pathways to improvement are required: Both enabling policy environments (top-down) and empowered, capable local management (bottom-up) are essential for sustainable reform.

- A.

- Government needs to create enabling environment through policy and regulatory reforms and

- B.

- Government also needs to develop capacity to apply, in a customized form, business management principles and practices at the institutional level, from top to bottom, down the hierarchy.

5. Conclusion: Improving Government Through Management Research

References

- Ahmed, N. (Ed.). (2016). Public policy and governance in Bangladesh: forty years of experience. Routledge. Routledge.

- Barnes, C., & Gill, D. (2000). Declining government performance? Why citizens don't trust government. New Zealand: State Services Commission.

- Behn, R. D. The big questions of public management. Public administration review 1995, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behn, R. D. The new public management paradigm and the search for democratic accountability. International Public Management Journal 1998, 1(2), 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlie, E., Lynn, L. E., & Pollitt, C. (Eds.). (2005). The Oxford handbook of public management. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press. Free Press.

- Goldman Sachs. (2005). The Next Eleven: A global growth market. Retrieved from https://www.goldmansachs.com.

- Grindle, M. S. (2011). Good enough governance revisited. Development Policy Review, 29(1).

- Huque, A.S. (2016). The ‘holy grail’ of governance. Routledge: London and New York.

- Kettl, D. F. (2002). The transformation of governance: Public administration for the 21st century (p. 119). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

- Khaled, M. C. (2013). Improving environment through policy and regulatory reforms and applying modern business management practices in government: Case of a developing country like Bangladesh. (Unpublished M. Phil. Thesis), University of Chittagong.

- Khaled, M. What is missing in government: Development theories or management basics? Cases from Bangladesh . Chittagong University Journal of Business Administration 2015, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Khaled, M. Reforms and improvement initiatives in government of Bangladesh: Field observation and analysis (2010–2018) . American Economic & Social Review 2019, 13(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Khaled, M. The idea of management in government: Evolution of the concepts and implications for reform . CIU Journal 2021, 4(1). [Google Scholar]

- Khaled, M. Making government work: An analysis of the regimes and reforms in Bangladesh, 1971–2021 . CIU Journal 2025, 7(1). [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. A. (2015). Gresham's law syndrome and beyond. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

- Khan, M. M. (2015). Administrative reforms in Bangladesh. Dhaka: University Press Limited.

- Kickert, W. J. M. (Ed.). (1997). Public management and administrative reform in Western Europe. Edward Elgar Pub.

- Kotler, P. & Lee, N. (2006). Marketing in the public sector: A roadmap for improved performance. Pearson Education.

- Langbein, L.; Knack, S. The worldwide governance indicators: Six, one, or none? The Journal of Development Studies 2010, 46(2), 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. (2012). Bangladesh: The next hot spot in apparel sourcing. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com.

- Newman, J. (2001). Modernizing governance: New labour, policy and society. Sage.

- Nye, J. S., Zelikow, P., & King, D. C. (Eds.). (1997). Why people don't trust government. Harvard University Press.

- Oman, C. P., & Arndt, C. (2010). Measuring governance. (No. 39). OECD Publishing.

- OECD (2011). Government at a glance. OECD publications.

- Olsen, J. P., & Peters, B. G. (Eds.). (1996). Lessons from experience: Experiential learning in administrative reforms in eight democracies. Scandinavian University Press.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform: A comparative analysis-new public management, governance, and the Neo-Weberian state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ruscio, K. P. Trust, democracy, and public management: A theoretical argument. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 1996, 6(3), 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, N. 2016. The trust issue: Introduction. Oxford government review number 1 / August 2016.

- Woods, N. 2017. Bridging the gap: Introduction. Oxford government review. Number 2 / October 2017.

- World Bank. (2002). Taming the leviathan: Reforming governance in Bangladesh. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2011). Governance matters. Washington, D.C.

- World Bank. (2017). Bangladesh Development Update: Breaking Barriers. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org.

- World Bank. (2022a). Bangladesh: Maternal and Reproductive Health at a Glance. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org.

- World Bank. (2022b). Bangladesh: World Bank Country-Level Engagement on Governance and Anticorruption. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org.

- World Bank. (2022c). Bangladesh: Curbing Corruption and Strengthening Governance: A Note on Strengthening Anticorruption Initiatives. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org.

- Zussman, D. Do citizens trust their governments? Canadian Public Administration 1997, 40(2), 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Worldwide Governance Indicators (www.govindicators.org) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).