1. Introduction.

As AR/VR technologies rapidly evolve, terminal devices are becoming increasingly heterogeneous and functionally integrated. System services are critical for maintaining platform stability and state awareness. However, the growing number of service modules and parallel development by multiple teams have introduced interface inconsistencies and complex collaboration challenges, limiting system performance and maintainability. To enable efficient, multi-platform service deployment and collaborative evolution, a unified and flexible system service convergence architecture is needed to overcome existing structural and operational limitations.

2 Analysis of AR/VR System Service Status Quo

As AR/VR terminals become more diverse and functionally complex, system service modules play an increasingly central role—handling bug logs, device monitoring, configuration sync, and more. However, most platforms still use loosely coupled or embedded deployment strategies, leading to inconsistent interfaces, low reusability, and high adaptation costs during cross-platform migration [

1]. Service modules are often maintained by separate teams without unified version control or deployment standards, complicating collaboration. Porting across Android, Windows, and embedded systems is hindered by inconsistent data structures and differing call mechanisms, limiting integration efficiency and system maintainability [

2]. Overall, current AR/VR system services face challenges of fragmented interfaces, duplicated resources, and escalating deployment costs in multi-platform development.

3. Converged System Service Architecture Design

3.1. Overall Architecture Design

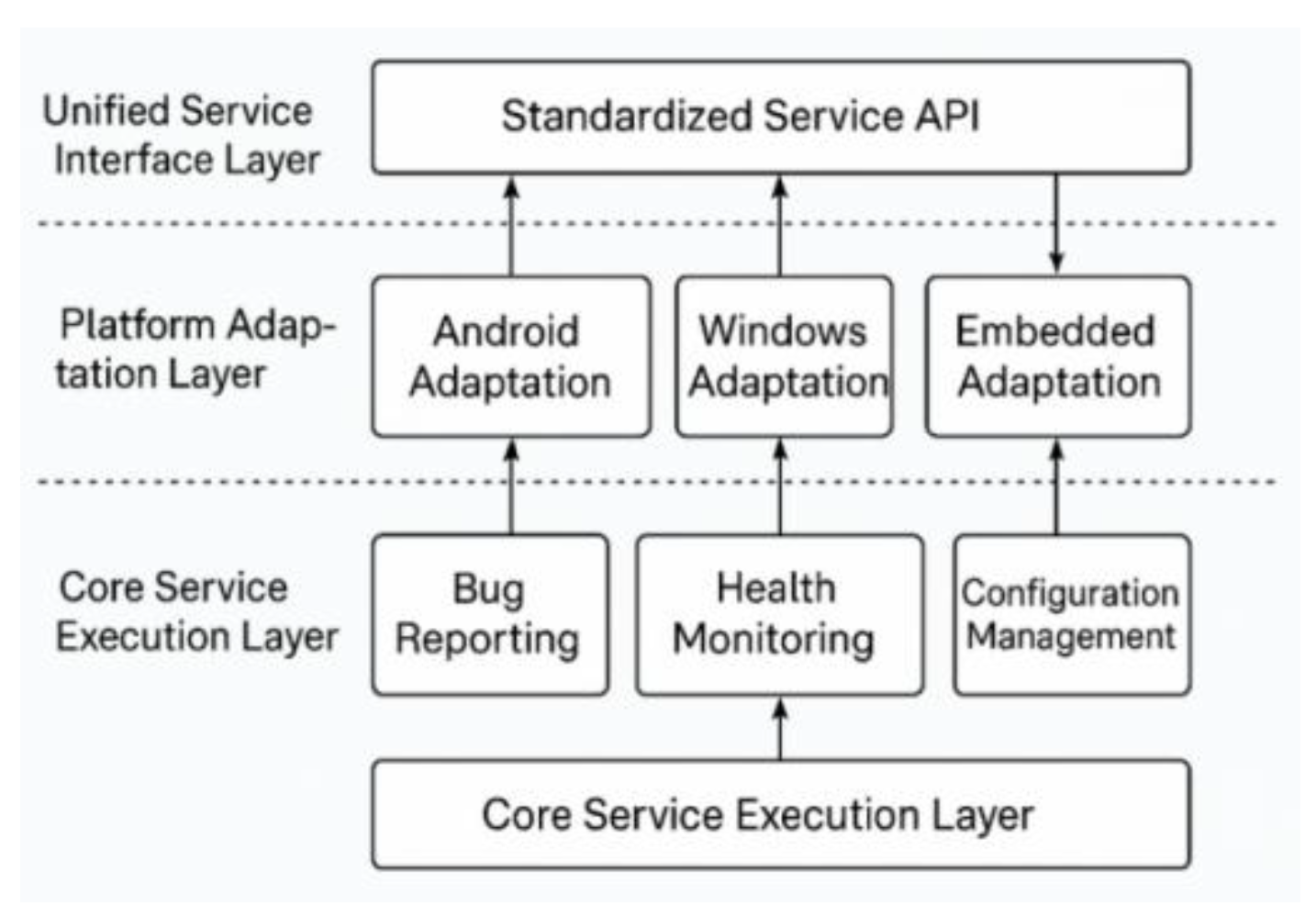

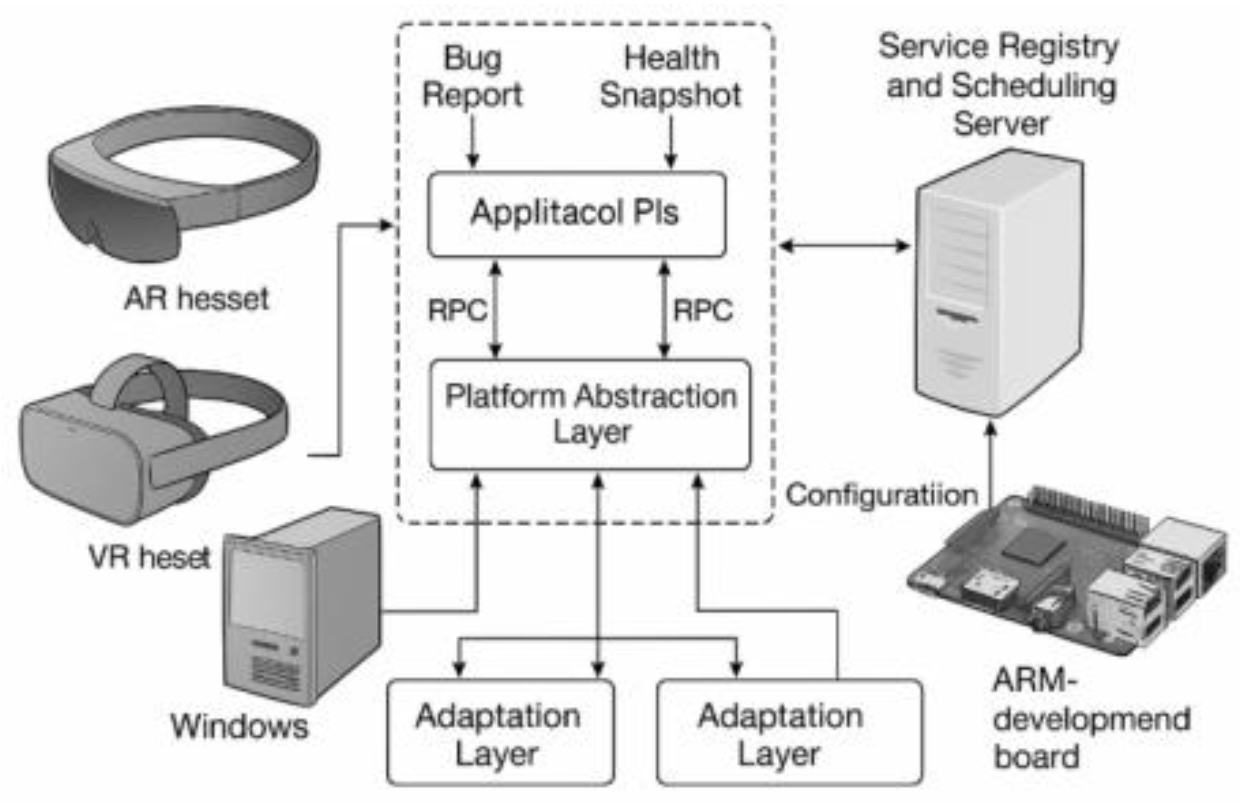

To address the growing complexity and limited portability of AR/VR system services in cross-platform deployment, a three-layer converged architecture is designed (

Figure 1). It consists of a unified service interface layer, a platform adaptation layer, and a core service execution layer, organized top-down [

3]. The unified service interface layer standardizes service calls using gRPC and REST, ensuring consistent access semantics across heterogeneous platforms. It hides platform-specific call differences and supports asynchronous invocation with error fallback logic. The platform adaptation layer bridges high-level interfaces and platform-specific implementations. It parses runtime configurations and binds interfaces via descriptor files and semantic mappings. This layer handles API remapping, data serialization, and callback adaptation for platforms such as Android, Windows, and embedded Linux. The core service execution layer contains functional modules like BugReport() and HealthSync(), containerized using lightweight frameworks (e.g., gVisor). These modules follow principles of single responsibility, exposed interfaces, and controlled resource access, with lifecycle-managed state transitions. A unified interface abstraction standard (

Table 1) ensures consistent interoperation across layers, defining I/O parameter formats, service dependencies, and exception strategies. The formalized structure is:

Where Si denotes the standardized encapsulated output of the ith service module, Mi is the internal state set of the module, Cp is the current platform running configuration parameters, and Dx is the upstream and downstream service dependency data. In order to enhance structural comprehensibility,

Figure 1 shows the logical composition and data flow of the overall architecture of converged system services, in which modules are interconnected through standard RPC channels, platform differences are uniformly encapsulated in the adaptation layer, and services can be deployed and extended on demand.

3.2. Core Service Module Design

3.2.1. Bug Reporting Service Module

As a core part of the service execution layer, the Bug Reporting Module enables unified collection, structured encoding, and asynchronous reporting of cross-platform error logs to improve system observability and maintainability. It employs an event-driven architecture and defines a common log structure based on the converged system framework. Error flows are decoupled via middleware queues (e.g., Kafka, ZeroMQ) [

4]. The module exposes a standardized API, BugReport(), which receives exceptions from platform adaptation layers. These are preprocessed, annotated, and encapsulated into protocol packets, then uploaded to a master node or centralized logging system. The log format includes:

Where L is the log entity, Ts is the timestamp, Pi is the device platform number, Ec is the abnormality category code, and Md is the diagnostic information content (JSON format, including stack, thread, memory status, etc.).

3.2.2. Health Monitoring Service Module

The health monitoring module performs real-time data collection, anomaly detection, and performance trend analysis—critical for system observability. Positioned between the execution and adaptation layers, it uses a modular probe mechanism to capture key metrics—CPU usage, memory consumption, frame rate jitter, and power draw—via lightweight sensing interfaces [

5]. These metrics are encoded into standardized Health Snapshot packages and periodically pushed to the main service node. The data structure (

Table 1) adopts field alignment and compression to reduce transmission delays and memory usage. The core model is defined as:

Where Ht is the health snapshot at moment t, Rc denotes the CPU load rate (%), Mu is the memory usage (MB), Fj denotes the variance of the rendering frame rate (a measure of lag), and Pd is the power consumption power (W). Each sampling point is smoothed and aggregated through an intermediate cache pool to adapt to high-frequency service scheduling scenarios.

3.2.3. Service Interface Standardization Design

In order to solve the problems of incompatible interfaces, inconsistent parameter structure and redundant data encapsulation of multi-origin service modules in the converged architecture, this study designs a set of service interface standardization framework for AR/VR multi-platform environment. The design adopts a three-layer interface encapsulation strategy of protocol abstraction + sequence constraints + platform isolation, uniformly binds core services such as Bug Reporting and Health Monitoring to the Service Registry [

6], and defines interface attributes and data constraints through Unified Service Description Language (USDL). The service invocation is based on asynchronous non-blocking model, and the core interface design is abstracted as follows:

Where Isvc(t) denotes the service invocation process at moment t, Pin(t) is the set of interface input parameters, Φenc is the serialization and validation function, and Ψout is the standard response structure. The standardized interface definition adopts JSON Schema and gRPC IDL dual structure for constraints and translation, and establishes a unified index table in the service registry (

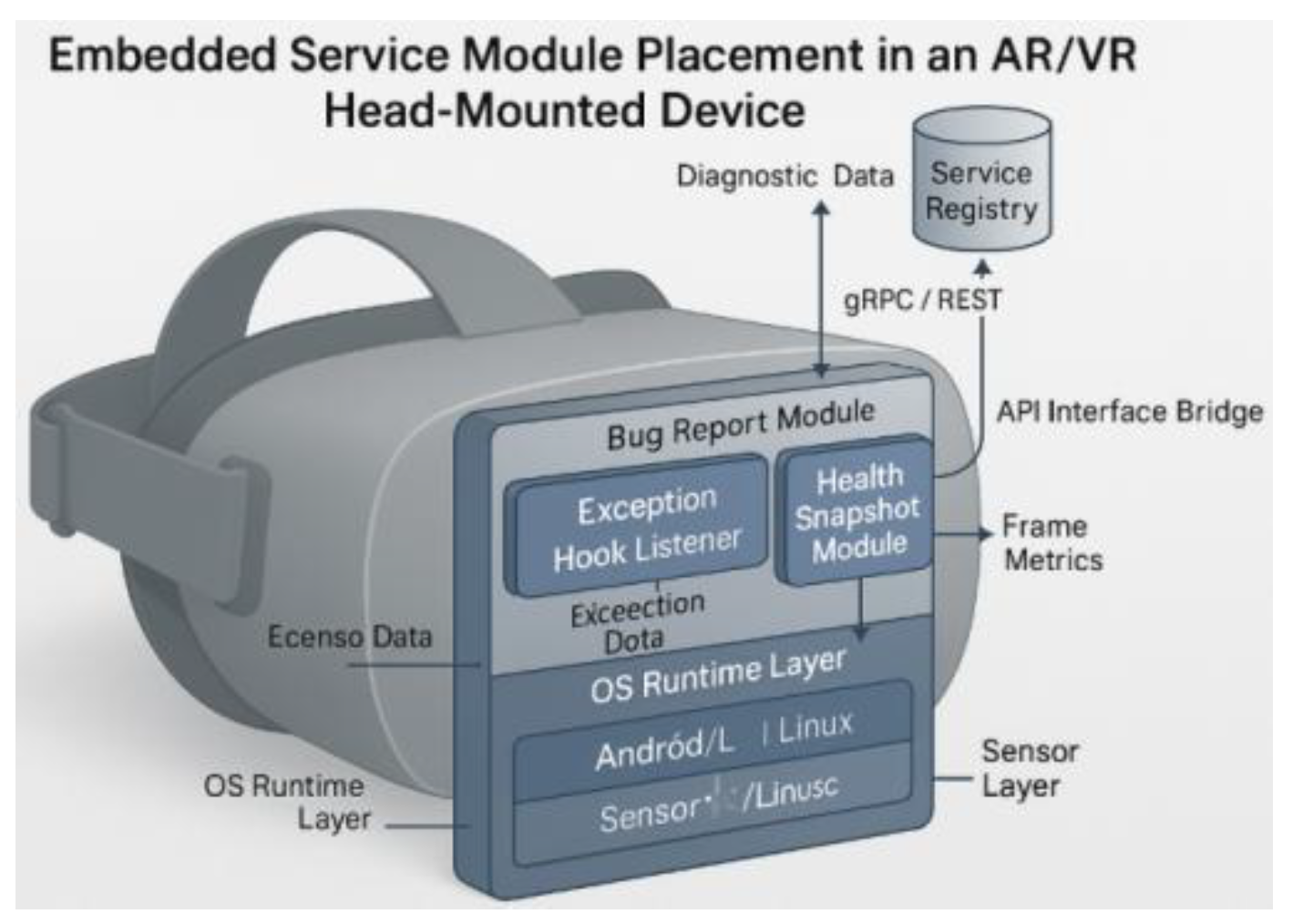

Table 2) to ensure that each module has seamless interoperability between different platform adaptation layers. In order to improve system observability and fault traceability in actual hardware deployment, the integration points of core service modules in AR/VR head mounted devices are further visualized. Figure 3 shows the embedded positioning of bug reporting and health monitoring modules in the VR headset system stack, highlighting the data capture layer, transmission pipeline, and platform specific interface mapping.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of service module embedding points in AR/VR headset devices.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of service module embedding points in AR/VR headset devices.

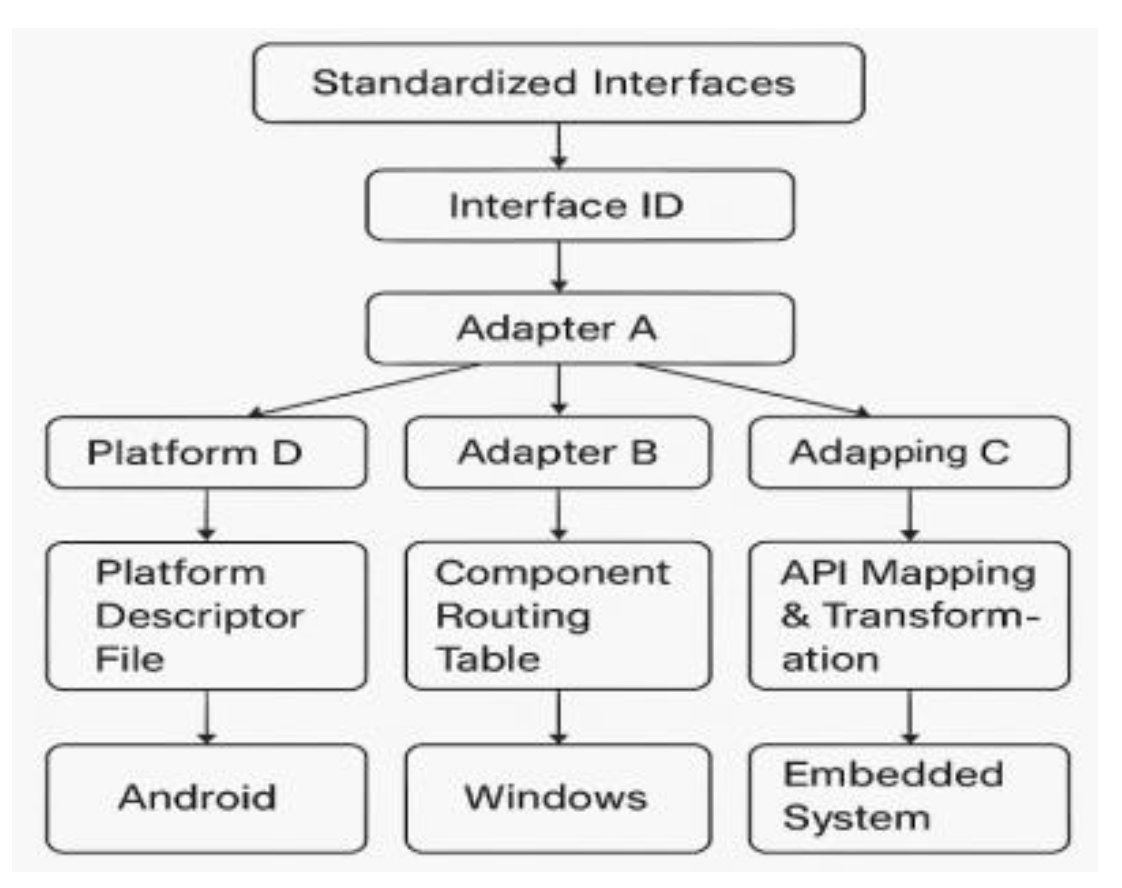

3.3. Cross-Platform Adaptation Layer Design

To enable unified deployment and flexible invocation across platforms, the adaptation layer employs a core strategy of bridge encapsulation, runtime parsing, and interface mapping to establish a platform-independent service path. Positioned between standardized interfaces and platform-specific implementations, it uses dynamic loading to connect with registered interfaces (

Table 3) and auto-maps platform-specific API semantics. The mechanism relies on a component routing table and Platform Descriptor File (PDF) to construct the interface bridge (

Figure 3), where each service is linked to a unique adapter object encapsulating API mapping rules, data conversion logic, and callback handling.

4. Key Technology Realization

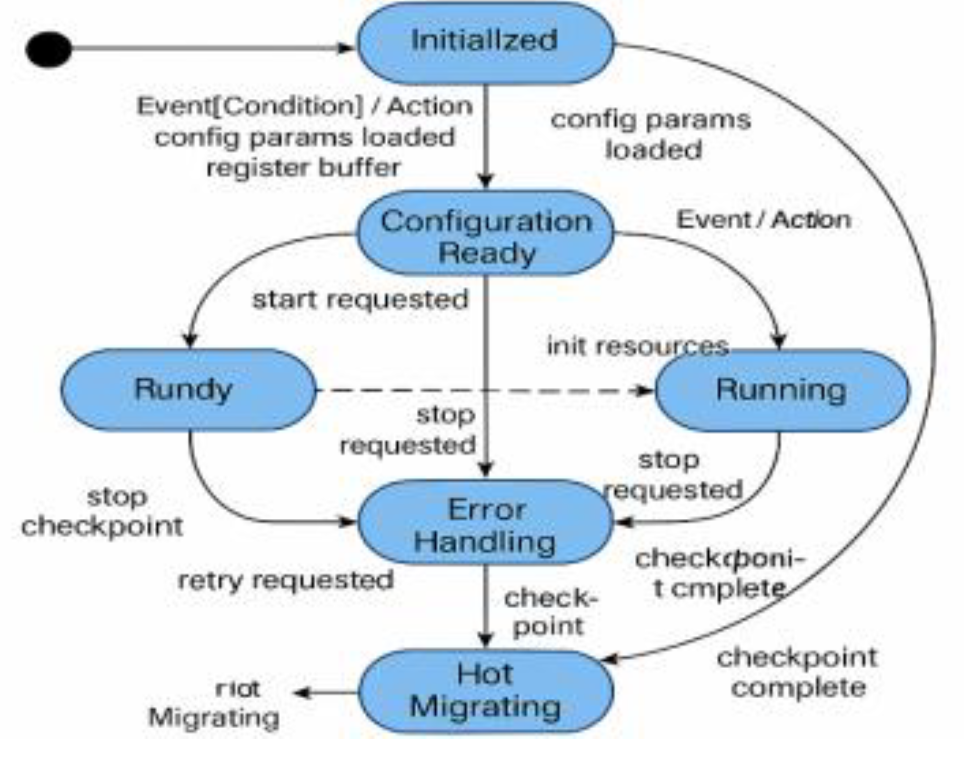

4.1 Service Module Encapsulation Technology

The architecture adopts a combination of explicit module boundary declarations and containerized abstraction to ensure consistency and reusability in cross-platform deployment. Each module is designed with logical granularity based on unified protocols (e.g., gRPC/REST), and its dependencies, entry points, and lifecycle policies are defined in a Module Descriptor (MD). Encapsulation follows the principle of single function, clear interface, and controllable state. Runtime isolation and resource control are achieved using lightweight container frameworks (e.g., gVisor) [

7]. Service state transitions are modeled as a directed graph (

Figure 4), where nodes represent states, and edges denote transitions triggered by specific events and constraints. For example, the BugReport module moves from initialization to ready only when configuration parameters are set and the log buffer is registered.

4.2. Service Sharing Mechanism Implementation

The sharing mechanism adopts a centralized registration + distributed reference model, combining a Service Registry and lightweight discovery protocol to create a unified service channel [

8]. After encapsulation, each core module submits metadata—including service ID (SID), interface definition (IDL), and platform support attributes—to the registry [

9]. The registry builds a key-value mapping table. Platform adaptation layers retrieve service references via asynchronous subscriptions and bind them to local adapters. To prevent call conflicts and reentry issues, a Call Lease Model is applied, defined as:

Where Li(t) indicates whether service Si is allowed to be invoked at moment t; Tstarti and Tendi are the invocation effective and expiration timestamps respectively, and the state value of available indicates reusability.

4.3. Portability Assurance Technology

To enhance portability in multi-platform environments, the architecture introduces module-level improvements in three areas: interface design, dependency abstraction, and configuration isolation. At the interface level, a platform-neutral codec model is established using Unified Service Description Language (USDL) and a multi-protocol bridging strategy to eliminate platform-specific semantics in shared services [

10]; at the execution layer, the resources (including paths, permissions, and access rights) required for service operation are integrated into the service architecture by using Runtime Context Virtualization (RCV) mechanism. At the execution layer, the resources required for service operation (including paths, permissions, and dependency libraries) are abstracted as platform-independent configuration vectors

, and platform adaptation binding is accomplished through the following service binding function:

Where Bi(P) denotes the binding state of service Si on platform P, C⃗i is the service generic configuration vector, and DP is the platform descriptor information set. Binding is dynamically performed by the adaptation layer during deployment, supporting delayed loading and on-demand configuration to avoid hard-coded dependencies. To prevent version drift, a version freezing mechanism statically locks compilation dependencies using hash validation and symbolic links, ensuring consistent deployment.

5. Experiment and Verification

5.1. Experimental Environment and Design

To evaluate the proposed architecture, a controlled multi-platform testbed was built (

Figure 5), supporting both the new framework and a traditional loosely-coupled baseline. The hardware includes a virtualization-enabled x86 server (Intel i7-11700, 32GB RAM) as central registry and scheduler, connected to three nodes: Android 13 (ARM64 emulator), Windows 10 (x64), and Embedded Linux (Cortex-A55 board). All nodes register services via a unified configuration protocol and run containerized deployments using LXC and QEMU. Two deployment strategies were tested: Baseline: Monolithic, platform-specific services without interface abstraction, integrated via local daemons; Proposed: Modular services with standardized interfaces, adaptation layers, and centralized registry. Both setups ran under identical load conditions. A custom generator simulated 200 requests/min for logging and health snapshots to ensure equal operational intensity. Metrics—latency, deployment time, memory usage, and maintenance effort—were collected using ServiceTracer, perfstat, and systemd-analyze. Each test was repeated five times per platform to compute statistical averages. Deployment time was measured from package dispatch to full registration. Maintenance labor was estimated via task breakdowns across three real patch deployments.

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

Across all three platforms, the proposed architecture consistently improves deployment efficiency, runtime stability, and resource usage. Key results are shown in

Table 3, comparing the proposed and baseline implementations. BugReport response delay dropped by 19.3% on average (e.g., 91 ms to 74 ms on Android), enabled by decoupled event handling and optimized queues. HealthSnapshot packet loss remained below 1.4% at 10 Hz, over 50% better than the 2.5–3.1% baseline, due to buffered transmission and interface standardization. Deployment time was reduced by 38.7% across platforms, credited to containerization and unified descriptors. Maintenance workload dropped from 6 to 2 engineers per patch task, thanks to interface unification and automated version binding. Performance gains were consistent across five test cycles (standard deviation < 3.5%), confirming the architecture’s reliability under real-world conditions.

5.3. Comparison with Existing Practices

While the proposed architecture addresses service fragmentation and cross-platform challenges, it's important to compare it with common DevOps and microservice orchestration solutions targeting deployment complexity. Traditional CI/CD tools (e.g., Jenkins, GitLab CI, GitHub Actions) automate build-test-deploy cycles but operate mainly at the application layer, relying on pre-defined modular structures. In contrast, the proposed architecture unifies system-level services (e.g., bug logging, health monitoring) across OS-level boundaries like Android, Windows, and Embedded Linux. Similarly, orchestration platforms (e.g., Kubernetes, Nomad) manage containers and dynamic discovery but assume stateless, loosely coupled services with minimal platform bindings. By contrast, this architecture emphasizes cross-platform bindings, lifecycle isolation, and descriptor-driven deployment for tightly coupled, stateful services. CI/CD tools don’t address interface inconsistency or semantic mismatches in heterogeneous runtimes—issues this work directly targets. Rather than replacing DevOps pipelines, the proposed framework complements them as a foundational system-level abstraction, bridging OS services and higher-level automation layers.

6. Conclusion

The proposed converged system service architecture effectively addresses service fragmentation, interface inconsistency, and deployment inefficiency in heterogeneous AR/VR environments. Through modular encapsulation, standardized interfaces, and dynamic adaptation, it significantly improves cross-platform portability and system observability. Validation across multiple platforms and simulated multi-team workflows confirms its applicability beyond single-use scenarios, with consistent gains in deployment time, fault traceability, and maintenance effort. These results support its generalizability across diverse AR/VR ecosystems. However, challenges remain—particularly on ultra-constrained platforms and under high-concurrency conditions. Multi-layer abstraction may introduce overhead in real-time contexts, and developers may face a learning curve when adopting unified protocols. Integration with legacy systems may also require substantial effort for API remapping and dependency alignment. Future work will explore adaptive scheduling and context-aware abstraction to further enhance performance in dynamic environments.

References

- Rajkumar R, Kashyap R, Posonia M. AR/VR based Campus Navigation System (CNS)[C]//2025 7th International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS). IEEE, 2025: 1265-1271.

- Herabad M G, Taheri J, Ahmed B S, et al. Optimizing service placement in edge-to-cloud ar/vr systems using a multi-objective genetic algorithm[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12849, 2024.

- Liu Y J, Du H, Niyato D, et al. Slicing4Meta: An intelligent integration architecture with multi-dimensional network resources for metaverse-as-a-service in web 3.0[J]. IEEE Communications Magazine, 2023, 61(8): 20-26.

- Adepoju A H, Eweje A, Collins A, et al. Framework for migrating legacy systems to nextgeneration data architectures while ensuring seamless integration and scalability[J]. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation, 2024, 5(6): 1462-1474. [CrossRef]

- Pillai B M. A Deployment Model for Digital Twin-Enabled: AR/VR Robotic Systems in Healthcare and Special Education[M]//Smart Healthcare, Clinical Diagnostics, and Bioprinting Solutions for Modern Medicine. IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2025: 1-16.

- Winter A, Ammenwerth E, Haux R, et al. Technological perspective: architecture, integration, and standards[M]//Health Information Systems: Technological and Management Perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023: 51-152.

- Li J, He J, Zhou X. Design of Museum Cultural Relics multi view virtual display system based on AR-VR fusion technology[C]//2021 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP). IEEE, 2021: 912-915.

- Hu,L.;Wu,Q.;Qi,R. (2025). Empowering smart app development with SolidGPT: an edge–cloud hybrid AI agent framework. Advances in Engineering Innovation,16(7),86-92. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Sheng Q Z, Benatallah B, et al. Metaverse services: The way of services towards the future[C]//2023 IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS). IEEE, 2023: 179-185.

- Rajput S, Yadav S. Cyber-physical fusion architecture: To mitigate risk for resilient supply chain[M]//Risk, Reliability and Resilience in Operations Management. Elsevier, 2025: 291-312.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).