1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a conversion that occurs when microorganisms are treated with antimicrobial drugs, which leads to the antimicrobials becoming ineffective [

1]. The WHO states that current antibiotics are becoming a very sparse source due to the growing rates of AMR worldwide and since very few new antibiotics are being produced [

1]. According to an analysis that was done about the burden of AMR globally it was found that the most prevalent resistant organisms which led to the biggest amount of deaths were

Escherichia coli, followed by

Staphylococcus aureus,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Acinetobacter baumannii, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

2].

In the surveillance report released by the National Department of Health (NDoH) of South Africa in 2024, it was reported that the most common organisms cultured from blood in the private and public sectors were

Klebsiella pneumoniae followed by

Staphylococcus aureus,

Escherichia coli,

Acinetobacter baumannii and then

Enterococcus faecalis. This report also states that in the last five years, South Africa has seen an average of 70% in the prevalence of ESBL-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae organisms [

3]. Resistance has developed against almost all classes of antibiotics, especially antibiotics that are frequently used to treat common bacterial infections [

4]. Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones was seen in

Escherichia coli, in five of the WHO regions and to

Klebsiella pneumonia, in six WHO regions [

5]. In two of the WHO regions, there was a rate of carbapenem resistance of more than 50% [

5].

In 2016, the Heads of State of the United Nations General Assembly sanctioned a political declaration to address the global problem of AMR [

6,

7]. It is very important that antibiotics are only given to patients who really need them and that last-resort antibiotics be preserved [

1]. Difficult-to-treat resistant organisms show resistance to most first-line antimicrobials, like fluoroquinolones and β-lactams, including carbapenems and treatment of these organisms are becoming an enormous challenge [

8].

Carbapenems are one of our last-line antimicrobials, therefore, it is important that we use them correctly [

9]. Carbapenems are ideal for treating resistant pathogens since they are not easily broken down by most β-lactamases and extended-spectrum β-lactamases [

10]. The WHO has placed carbapenems in the ‘Watch’ classification and these antibiotics are known to have a big chance of resistance [

11]. In the last few years, the use of carbapenems has increased and this has caused an increase in gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to carbapenems [

12]. In a global point prevalence survey done in 53 countries it was found that carbapenems were the most prescribed antibiotics in the 12 African hospitals which took part in this survey [

13]. A study that was conducted in the United States of America (USA), found that the unwarranted use of carbapenems in hospitals can increase the rates of carbapenem resistance amongst complicated gram-negative bacteria like

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

14]. Another study that was conducted in Greece found that there is a proven positive relationship between the use of carbapenem and carbapenem resistance [

15,

16]. In a study that was conducted in Africa it was found that the contributing factors for infections with carbapenem resistant enterobacterales (CREs) were the previous use of antimicrobials, indwelling devices, a prolonged hospital stay and intensive care unit admission, this is the same as those who are reported worldwide, 54,4% of the studies was done in North Africa [

17].

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA, describes carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria as “posing an urgent threat to global health” [

18,

19]. Therefore, ASPs have an objective to improve carbapenem utilisation which will include encouraging the de-escalation strategy to reduce carbapenem usage [

14].

In 2016, the Heads of State of the United Nations General Assembly sanctioned a political declaration to address the global problem of AMR [

6,

7]. The declaration stated that AMR requires a global response since it is threatening the achievement of sustainable development goals [

6]. A National AMR Strategy Framework was drafted in South Africa in 2015, by the NDoH, who acknowledged the threat of AMR. It is a comprehensive approach with roles and responsibilities that are aimed at addressing AMR [

7]. Minimising the occurrence of AMR is the main goal of ASPs [

20]. Studies conducted in Palestine, have shown that ASPs have a positive influence on correct antimicrobial prescribing and on the duration of hospital stay [

21]. Antimicrobial stewardship programs can refine the use of antimicrobials by using different strategies [

22] one of which is de-escalation [

20].

The aim of de-escalation is to decrease the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials [

23]. Some of the final anticipated outcomes for de-escalation include adapting the treatment in accordance with the clinical response; adapting the antibiotic treatment according to the results of the microbiological culture and/or susceptibility of the given bacteria; ceasing treatment and/or changing therapy from more than one antibiotic to monotherapy [

24,

25]. Targeted antibiotic therapy is very important, but this is only possible when the causative organism is provided by cultures with an antibiogram, which is a long procedure and can take up to 24 hours or more. Therefore, treatment with empiric antibiotics needs to be initiated [

26]. There are many factors that can influence the choice of empiric therapy, including the most likely pathogen, resistance patterns (based on local data and antibiograms), the degree of illness, the infection site and the co-morbidities of the host [

27]. Two biomarkers are commonly used to guide antimicrobial treatment, C-reactive protein (CRP), which is affordable and used in intensive care units for patients with infections that are life-threatening [

28] and procalcitonin (PCT), which is commonly used to help diagnose sepsis or bacterial infections [

29].

Once empiric antibiotic therapy has been started, the usefulness of the chosen empiric treatment should be assessed for the opportunity to practice de-escalation or to discontinue the antibiotic therapy [

30]. Even though de-escalation is one of the main elements of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS), it remains the most challenging [

20]. It is recommended to switch to an active antimicrobial when the microscopy, culture and sensitivity results show that an antimicrobial is not active against the causative organism and was started as empiric therapy [

31]. De Waele, et al., refer to antimicrobial de-escalation as the “streamlining of antimicrobial therapy” [

32]. Effective de-escalation leads to a decrease in AMR and antibiotic-related side-effects as well as a decrease in antimicrobial costs [

33]. Some of the barriers to de-escalation include, but are not limited to, a shortage of diagnostic facilities, scarcity of education and multidisciplinary collaboration and due to the indecision to de-escalate antimicrobials in patients who are critically ill and who are clinically improving with the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials [

24,

34]. If antibiotic de-escalation is not practiced for all eligible patients, there will be an increase in the overuse of antibiotics and it will lead to an increase in antimicrobial resistance [

34].

2. Materials and Methods

Study design, site and period: The study followed a retrospective, descriptive research approach. It was a quantitative study determining the number of patients who were prescribed carbapenems, how many of the prescribed carbapenems were used as empiric treatment, how many patients on empiric treatment were de-escalated and if not de-escalated, whether a reason could be obtained. This retrospective study was conducted for three consecutive months (16 February 2023 – 15 May 2023) in a private hospital in South Africa with a bed capacity of 231 patients.

Sample selection and study population: A purposive sampling method was used to choose the study population. The files of all the adult patients who were prescribed carbapenem therapy and were admitted to the hospital during the study period were reviewed. A sample size of 243 patients per month was calculated using Raosoft.

Inclusion criteria: All patients aged 18 and above, in the Intensive care unit (ICU), high care, medical and surgical wards who were started empirically on carbapenem therapy.

Exclusion criteria: All patients that were discharged/deceased within 3 days of starting carbapenem therapy.

Data collection and data collection instruments: Data was collected by retrospectively reviewing the patient files. The hospital uses software that compiles different reports that contain all medical reports and patient details called SAP. A report was drawn from SAP to identify all the patients who received carbapenem treatment in our study period. The files of the patients were then used to complete the data collection sheet. The data collection sheet was adopted from the study of Sadyrbaeva-Dolgova, et al.

, (2020) [

25]. Each carbapenem “course” was captured on a new datasheet. The data sheet contained the following information: the patient study number, the basic demographical information (age, gender), date of admission and discharge, the reason for admission, antibiotics used in the last three months (if known), infection markers on the day carbapenems were started and on day 3 of carbapenem use, if cultures were done and the susceptibility thereof, and if the carbapenem treatment were de-escalated or not and to which antimicrobial therapy was de-escalated to. De-escalation was seen as stopping antimicrobial treatment, de-escalating to an antimicrobial with a narrower spectrum, or changing treatment to targeted therapy (whether it was broader or narrower spectrum).

Statistical analysis: All the data sheets that were collected were captured on a Microsoft ExcelTM spreadsheet and double-checked to ensure accuracy. Data was cleaned and sent to a statistician for further analysis. The variables were summarised using a range of statistical measures, including frequencies, percentages, mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range, depending on the distribution of each variable. Associations between patients whose therapy was not de-escalated and those who were de-escalated and various categorical variables were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test, while independent t-tests were employed to compare continuous variables between the de-escalation and non-de-escalation groups. The significance level was set at a p-value of 0.05, as the study was conducted with a 95% confidence interval. All analyses were conducted utilising IBM SPSS v28. The data was presented in the form of graphs, charts and tables.

3. Results

3.1. Population and Prevalence of Carbapenem Prescription

During the study period, approximately 1 754 patients were admitted to the wards with a total of 197 (11.2%) patients started empirically on carbapenems, but 21 patients were excluded because they formed part of the exclusion criteria.

The study included 176 patients with a median age of 66 (IQR 54-77) years, 53.4% were female and 46.6% were male. The median length of stay in the hospital stay was 13 days for all patients. 77 patients (43.8%) received some type of antimicrobials within the past 90 days.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the total patients that were included in the study.

3.2. Carbapenems Used for Empiric Therapy

Ertapenem was the carbapenem prescribed the most (62.4%), followed by meropenem (25.4%) and then imipenem/cilastatin (12.2%).

3.3. Culture Availability

Cultures were conducted in 125 patients (71.1%) and 68 (38.6%) showed positive organism growth. Some patients cultured more than one organism giving a total of 75 organisms that was cultured.

E. coli was the most cultured organism 37.3%, followed by

K. pneumonia (26.7%). From all the positive cultures that were obtained, the Enterobacteriaceae family was cultured in 80% of positive cultures.

Table 2 shows whether cultures were obtained or not, as well as the results of the cultures. If cultures were obtained, were the patient’s therapy de-escalated or not, this will lead us to understanding why patients with positive cultures are not being de-escalated.

3.4. De-Escalation

De-escalation was practised in only 30 patients (17%). De-escalation was practiced in 93.3% (n=30) of patients who had culture results (p=0.003) and 92.9% (p=<0.001) of the patients who had positive cultures confirmed The p-value of <0.001 indicates that if there was a positive organism cultured it led to de-escalation of therapy.

Table 3.

De-escalation with regard to cultures.

Table 3.

De-escalation with regard to cultures.

| Variables |

Total (n=176,%) |

De-escalated (n= 30) |

Not

de-escalated

(n=146)

|

p-value |

Cultures

Yes, n (%)

No, n (%)

|

125 (71.1)

51 (28.9) |

28 (93.3)

2 (6.7) |

97 (66.4)

49 (33.6) |

0.003 |

Culture results

No growth, n (%)

Growth, n (%)

No cultures, n (%)

|

57 (32.4)

68 (38.6)

51 (29.0)

|

n=28

2 (7.1)a

26 (92.9) |

n=97

55 (56.7)

42 (43.3) |

<0.001 |

Table 4 shows how empiric therapy was de-escalated (stopped, narrower spectrum or targeted therapy). Targeted therapy after cultures were received, was conducted in 21 patients (70%) and some of these patients required a carbapenems (20/21patients) or a reserve antimicrobial, like tigecycline (1/21 patients) since they had an infection with by an MDR organism. The antimicrobial that was used mostly as targeted therapy was meropenem (59%).

3.5. Factors or Reasons for Not De-Escalating

The infection markers of the patients who were included in the study were obtained to see if there is a correlation between infection markers and de-escalation. The mean CRP of all patients started on empiric carbapenem treatment was 157.1mg/dL and on day three of treatment the mean CRP decreased to 112.4 mg/dL.

Table 5 shows the infection markers of all the patients in the study sample vs patients who were de-escalated and those who were not.

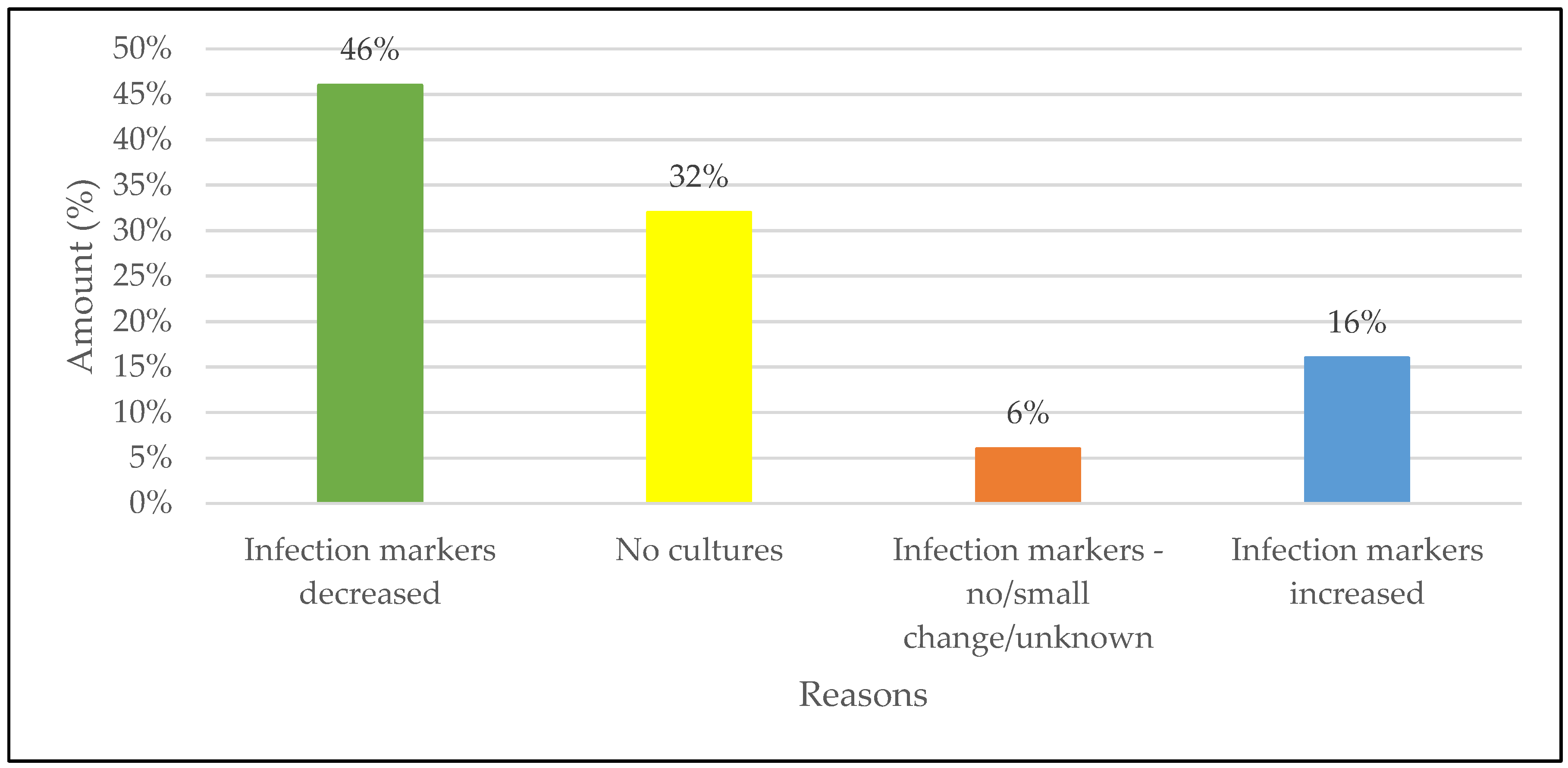

The highest reason for not de-escalating was patients who were improving clinically on empiric carbapenem therapy with 67 of the patients (46%) showing a decrease in infection markers which is seen as patient improvement. The second largest reason for not de-escalation was the unavailability of cultures in 32% of patients.

Figure 2 gives a schematic illustration of the reasons de-escalation was not practiced.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has been conducted to determine why prescribers do not practice empiric carbapenem therapy de-escalation in South Africa. The main findings was that prescribers did not want to de-escalate from empiric therapy, firstly, because according to the biomarkers and presentation, the patient was improving on the current carbapenem therapy followed by no cultures being done to guide therapy. When looking at the p-values of the study it can be stated that the availability of cultures, especially positive cultures, is one of the main factors that will lead to antimicrobial de-escalation., if no cultures are available there is a minimal chance that de-escalation will be practiced.

The right choice of empiric therapy is very important since it can lead to improved treatment outcomes and help to limit AMR [

27]. The first objective was to determine the prevalence of empiric carbapenem prescriptions. This study found that one-tenth of all patients admitted were started empirically on a course of carbapenem treatment. This is to be expected because according to the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Surveillance System (GLASS) report of 2022, it stated that because of the increasing resistance that has been seen in

Klebsiella pneumonia to third-generation cephalosporins, is causing an increase in empiric carbapenem use [

35]. Ertapenem was the empiric carbapenem of choice by 62.4% of the patients in our study similar to other studies done in the same setting [

36]. Other studies have shown that this is usually the carbapenem of choice in patients that’s not critically ill, who do not have a risk of being infected by

Pseudomonas spp or

Acinetobacter spp. and who have not been treated with other antimicrobials in the past 90 days [

37].

C-reactive protein can help to differentiate between bacterial and viral infections as well as to determine the bacterial infection’s severity [

38]. The CRP was >100 (raised) in 55.8% of the patients when empiric carbapenem therapy was started and the CRP after 3 days of carbapenem therapy was <100 in 48.2% of patients, which indicated that patients were improving on carbapenem therapy. PCT, which is a more sensitive marker for bacterial infections [

39], was raised in 26.9% of the patients at the start of carbapenem therapy, but PCT was not performed often since it is an expensive test. It was not performed in 72.1% of the study population. After 3 days of carbapenem therapy, PCT test was only conducted in 16.7% of the population. It has been shown that CRP and PCT can help to de-escalate antimicrobial therapy at an earlier stage [

40]. Therefore it is crucial to invest in ways where these tests can be conducted more often. De-escalation was not practiced in most of the patients (73.6%), mostly due to patients’ infection markers improving (decreasing) while on carbapenem treatment (46%) which was seen as clinical improvement – these patients did not have any positive cutures. Other factors, similar to other studies also played a role in patients not being de-escalated, for instance, infection markers increasing or a small change in infection markers after carbapenems have been started [

1]. Masterton also listed these as some of the barriers to de-escalation where it was found that de-escalation was not practiced due to the indecision to de-escalate antimicrobials in patients who are critically ill and who are clinically improving with the use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials [

24,

34].

The unavailability of cultures was the second highest contributor for patients not being de-escalated, which was seen in 32% of the patients that were not de-escalated. This is concerning because it results in the empirical use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials without definitive identification of the underlying pathogens. This correlates with the study that was done by Jacob et al.

, where the microscopy, culture and sensitivity tests were done for only 34% of the patients. From these patients, who had a positive culture, proper de-escalation only took place in 36% of the patients [

41]. For de-escalation to take place, cultures are needed to target the correct organism with the correct antimicrobial [

20]. This was a challenge as the cultures were not always done in this study setting, with 29% of patients did not have cultures done. Of the 71% of patients that had cultures taken, only 54.3% of cultures had bacterial growth. It is common to obtain high culture-negative rates when empiric antibiotic therapy is started before cultures are obtained [

42]. Obtaining blood cultures after a patient received antimicrobial therapy, could result in a lowered blood-culture yield [

43].

After the culture results became available, antimicrobial de-escalation was practiced in 15.7% of all the patients who were started on carbapenem therapy (n=197). This is quite a small number compared to the 73.6% that were not de-escalated. 10.7% of patients were discharged/deceased before 72 hours of carbapenem treatment. In the de-escalation group, 71% of the patients received targeted escalation therapy since they had an infection caused by a MDR organism, mostly

Klebsiella pneumoniae. Patients with ESBLs had to stay on the carbapenem or change to tigecycline. Most of the patients were treated with meropenem. Meropenem is more widely used than ertapenem because it also covers

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Acinetobacter baumanni [

44].

The Enterobacteriaceae family was the most prevalent organisms that were cultured with an occurrence rate of 77.4% of all positive cultures.

Escherichia coli was the most prevalent pathogen accounting for 31/84 isolates and secondly

Klebsiella pneumonia accounted for 21/84 isolates. This is similar to the information that was submitted by the NDoH, where it was found that Enterobacteriaceae

K. pneumonia was the most prevalent organism cultured from blood results, followed by

E. coli [

3]. It has been identified, globally, that Enterobacteriaceae has started to develop resistance to carbapenems and to other antimicrobials e.g., fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides and sulphonamides, making it harder to treat these infections [

45]. In 70% of the patients where de-escalation was practiced, therapy was de-escalated to targeted therapy where there was a need to receive a carbapenem or a last-resort antimicrobial since an MDR organism was cultured. There is also a rise in infections caused by CRE’s in South Africa, as seen in a study that reported a higher rate of resistance in Enterobacteriaceae like

Klebsiella pneumoniae than in

Escherichia coli in public facilities [

46].

With the 73.6% of patients not de-escalated, there was a resulted increase in the use of carbapenems and used for longer periods for an average of six days. A total of 42% of patients received carbapenem therapy for longer than 6 days.

Inpatient settings will continue to be an important target for AMS interventions and improvement of utilization of antimicrobials and this study has shown possible areas where a clinical pharmacist can play a role similar to other studies where the pharmacist played a role in improving utilization of antibiotics [

47,

48]. Pharmacists are seen as custodians of medicine, they are perfectly situated and need to play a principal role within a multidisciplinary team to promote and coordinate the implementation and monitoring of ASPs [

20]. According to the findings in this study, the pharmacist can play a role in advocating for cultures to be taken, encouraging de-escalation, and collaborating with a multi-disciplinary team to help guide the patient-specific treatment plan.

We are aware of some limitations in this study. The study was conducted in a private hospital and is not representative of SA as a whole. However, this hospital, as most private hospitals has similar prescribing patterns. With the study conducted by Engler

et al. it was noted that compliance to the National Strategic framework was less [

49], this study could be used as the initial study to try and create guidelines for de-escalation to try to implement and reduce the use of the carbapenem antibiotics as they are in the Watch category according to the AWaRe classification, meaning they are prone to resistance [

50].

In a national point prevelant survey conducted in South Africa, the antibiotics in the WATCH category were used mostly in the ICU and it is concerning that this practice is now in the whole hospital setting [

51]. It was a retrospective study and therefore, the patient’s clinical picture was not considered and the reasons for not de-escalating were solely based on the laboratory results. Some patients’ files had been closed and new files opened – this was not considered for the length of hospital stay. The same patient who was started on a new carbapenem course was seen as a new carbapenem prescription, this may increase the amount of empiric therapy. Despite these limitations, we believe our findings are robust providing direction for the future on de-escalation. This includes a key role for clinical pharmacists’ progressing antimicrobial stewardship program activities in critical patients admitted to the hospitals. We would recommend for future studies to be conducted wider and more de-escalation to be done.

5. Conclusions

The increasing use of carbapenems as empiric therapy is of concern considering the increasing rate of AMR. Prescribers were reluctant to de-escalate treatment once they see that their patient is clinically improving however this contributes more to the increased use of antibiotics which leads to increased antimicrobial resistance. Considering that the carbapenems are also part of the Watch antibiotics, this is a great concern. We will recommend to initiate empiric antimicrobial therapy based on patients’ symptoms, medical history, and local epidemiology, while awaiting culture results, because without cultures, de-escalation is not feasible and the treatment is “a shot in the dark”. With the growing rate of AMR, de-escalation will become of more importance to preserve the antibiotics that still work.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, P.P.S. and P.D.; methodology,., P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D.; formal analysis, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D.; investigation, P.D.; project administration, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D; resources, P.D.; data curation, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D.; writing—review and editing, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D.; visualization, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D.; supervision, P.P.S. and L.A.Z.M.; project administration, P.P.S., L.A.Z.M. and P.D All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University (SMUREC/P/331/2020:PG; 27/01/2021). Approval to conduct the study was also obtained from the head office of the private hospital. Patient confidentiality was maintained by excluding personal identifiers. Only the authors had access to the data collection instruments.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to no personal information being used where patients can be identified. Informed consent was received from the private hospital group to conduct this study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data can be obtained on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the statistician for the analysis, prompt feedback and explanations. The hospital group for the opportunity to conduct this study. Finally, we acknowledge the School of Pharmacy and the division of Clinical Pharmacy for the opportunity to conduct this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in health-care facilities in low-and middle-income countries [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Aug 16]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329404/9789241515481-eng.pdf.

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- National Department of Health. Surveillance and Consumption of Antimicrobials in South Africa. 2024.

- World Health Organization Antimicrobial resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed June 8).

- Zhen, X.; Lundborg, C.S.; Sun, X.; Hu, X.; Dong, H. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in ESKAPE organisms: a systematic review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. At UN, global leaders commit to act on antimicrobial resistance [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/21-09-2016-at-un-global-leaders-commit-to-act-on-antimicrobial-resistance.

- Chetty, S.; Reddy, M.; Ramsamy, Y.; Naidoo, A.; Essack, S. Antimicrobial stewardship in South Africa: a scoping review of the published literature. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2019, 1, dlz060. [CrossRef]

- Brink AJ, Coetzee J, Richards GA, Feldman C, Lowman W, Tootla HD, et al. Best practices: Appropriate use of the new β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations in South Africa. South Afr J Infect Dis. 2022;37(1):10.

- Sheu, C.-C.; Chang, Y.-T.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hsueh, P.-R. Infections Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: An Update on Therapeutic Options. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 80. [CrossRef]

- Howatt M, Klompas M, Kalil AC, Metersky ML. Carbapenem antibiotics for the empiric treatment of nosocomial pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2021;150(3):1041-54.

- Gandra S, Kotwani A. Need to improve availability of “access” group antibiotics and reduce the use of “watch” group antibiotics in India. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2019;12:1-4.

- Peyclit, L.; Baron, S.A.; Rolain, J.-M. Drug Repurposing to Fight Colistin and Carbapenem-Resistant Bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 193. [CrossRef]

- Versporten, A.; Zarb, P.; Caniaux, I.; Gros, M.-F.; Drapier, N.; Miller, M.; Jarlier, V.; Nathwani, D.; Goossens, H.; Koraqi, A.; et al. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob. 2018, 6, e619–e629. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki A, et al. Impact of the multidisciplinary antimicrobial stewardship team intervention focussing on carbapenem de-escalation. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13693.

- Routsi, C.; Pratikaki, M.; Platsouka, E.; Sotiropoulou, C.; Papas, V.; Pitsiolis, T.; Tsakris, A.; Nanas, S.; Roussos, C. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteremia in intensive care unit patients. Intensiv. Care Med. 2013, 39, 1253–1261. [CrossRef]

- Garnier M, Gallah S, Vimont S, Benzerara Y, Labbe V, Constant AL, et al. Multicentre randomised controlled trial of βLACTA test for early de-escalation of carbapenems. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e024561.

- Kedišaletše, M.; Phumuzile, D.; Angela, D.; Andrew, W.; Mae, N.-F. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in Africa: A systematic review. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 35, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Alert Network. 2013.

- Peri, A.M.; Doi, Y.; Potoski, B.A.; Harris, P.N.; Paterson, D.L.; Righi, E. Antimicrobial treatment challenges in the era of carbapenem resistance. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 94, 413–425. [CrossRef]

- Schellack, N.; Bronkhorst, E.; Coetzee, R.; Godman, B.; Gous, A.G.S.; Kolman, S.; Labuschagne, Q.; Malan, L.; Messina, A.P.; Naested, C.; et al. SASOCP position statement on the pharmacist’s role in antibiotic stewardship 2018. South. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 33, 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Khdour MR, Hallak HO, Aldeyab MA, Nasif MA, Khalili AM, Dallashi AA, et al. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship programme on ICU patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(4):708-15.

- A Wells, D.; Johnson, A.J.; Lukas, J.G.; A Hobbs, D.; O Cleveland, K.; Twilla, J.D.; Hobbs, A.L.V. Can’t keep it SECRET: system evaluation of carbapenem restriction against empirical therapy. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2022, 5, dlac137. [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho FRT, Telles JP, Tuon FFB, Rabello Filho R, Caruso P, Correa TD. Antimicrobial stewardship strategies to avoid polymyxin and carbapenem misuse. Antibiotics. 2022;11(3):378.

- Masterton RG. Antibiotic de-escalation. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27(1):149-62.

- Sadyrbaeva-Dolgova S, Aznarte-Padial P, Pasquau-Liaño J, Expósito-Ruiz M, Hernández MÁC, Hidalgo-Tenorio C. Clinical outcomes of carbapenem de-escalation: a propensity score analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;85:80-7.

- Schuttevaer, R.; Alsma, J.; Brink, A.; van Dijk, W.; de Steenwinkel, J.E.M.; Lingsma, H.F.; Melles, D.C.; Schuit, S.C.E.; Lopez-Delgado, J.C. Appropriate empirical antibiotic therapy and mortality: Conflicting data explained by residual confounding. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0225478. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, T. “Rationalization of Empiric Antibiotic Therapy” – A Move Towards Preventing Emergence of Resistant Infections. Indian J. Pediatr. 2020, 87, 945–950. [CrossRef]

- Intensiva, O.B.O.N.–.N.I.d.I.E.M.; Borges, I.; Carneiro, R.; Bergo, R.; Martins, L.; Colosimo, E.; Oliveira, C.; Saturnino, S.; Andrade, M.V.; Ravetti, C.; et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial of a clinical and C-reactive protein-based protocol versus an evidence-based best practice strategy without biomarkers. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Seker YT, Yesilbag Z, Bilgi DO, Cukurova Z, Hergunsel O. The effects of de-escalation under procalcitonin guidance in sepsis. 2019.

- Strich JR, Heil EL, Masur H. Considerations for empiric antimicrobial therapy in sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 2):S119-31.

- Aitken SL, Clancy CJ. IDSA guidance on the treatment of antimicrobial-resistant Gram-negative infections. 2020.

- De Waele JJ, Schouten J, Beovic B, Tabah A, Leone M. Antimicrobial de-escalation as part of stewardship in ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(2):236-44.

- Nandita EC. A study of antibiotic de-escalation practices in medical wards [dissertation]. Vellore: Christian Medical College; 2020.

- Haseeb A, Saleem Z, Altaf U, Batool N, Godman B, Ahsan U, et al. Impact of culture reports on de-escalation in a teaching hospital. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;13:77-86.

- World Health Organization. GLASS report 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 3].

- Bronkhorst, E.; Maboa, R.; Skosana, P. Antimicrobial stewardship principles in the evaluation of empirical carbapenem antibiotics in a private hospital in South Africa. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf025. [CrossRef]

- Puthran, S.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Murlidharan, P.; Nambi, S.; Pavithra, S.; Petigara, T. Efficacy and cost comparison of ertapenem as outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in acute pyelonephritis due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Indian J. Nephrol. 2018, 28, 351–357. [CrossRef]

- Largman-Chalamish M, Wasserman A, Silberman A, Levinson T, Ritter O, Berliner S, et al. Differentiating bacterial and viral infections by CRP velocity. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0277401.

- Samsudin, I.; Vasikaran, S.D. Clinical Utility and Measurement of Procalcitonin. Clin Biochem Rev. 2017, 38, 59–68.

- Albrich WC, Harbarth S. Biomarkers vs clinical decisions in antibiotic use. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1739-51.

- Jacob VT, Mahomed S. Antimicrobial prescribing in the surgical and medical wards at a private hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2019. South African Medical Journal. 2021 Jun 1;111(6):582-6.Giuliano C, Patel CR, Kale-Pradhan PB. Bacterial culture identification and result interpretation. Pharm Ther. 2019;44(4):192.

- Sigakis, M.J.G.; Jewell, E.; Maile, M.D.; Cinti, S.K.; Bateman, B.T.; Engoren, M. Culture-Negative and Culture-Positive Sepsis: A Comparison of Characteristics and Outcomes. Anesthesia Analg. 2019, 129, 1300–1309. [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, C.; Patel, C.R.; Kale-Pradhan, P.B. A Guide to Bacterial Culture Identification And Results Interpretation. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2019, 44, 192–200.

- Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy [Mobile app]. Version 6.4.8. 2021.

- Bitew A, Tsige E. Prevalence of MDR and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Trop Med. 2020;2020:6167234.

- Fourie, T.; Schellack, N.; Bronkhorst, E.; Coetzee, J.; Godman, B. Antibiotic prescribing practices in the presence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) positive organisms in an adult intensive care unit in South Africa – A pilot study. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 541–547. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood RK, Gillani SW, Saeed MW, Vippadapu P, Alzaabi MJ. Impact of pharmacist-led services on stewardship. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2021;12(4):615-25.

- Saleem, Z.; Godman, B.; Cook, A.; Khan, M.A.; Campbell, S.M.; Seaton, R.A.; Siachalinga, L.; Haseeb, A.; Amir, A.; Kurdi, A.; et al. Ongoing Efforts to Improve Antimicrobial Utilization in Hospitals among African Countries and Implications for the Future. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1824. [CrossRef]

- Engler, D.; Meyer, J.C.; Schellack, N.; Kurdi, A.; Godman, B. Compliance with South Africa’s Antimicrobial Resistance National Strategy Framework: are we there yet?. J. Chemother. 2020, 33, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) Classification of Antibiotics for Evaluation and Monitoring of Use. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/2021-aware-classification (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- Skosana, P.; Schellack, N.; Godman, B.; Kurdi, A.; Bennie, M.; Kruger, D.; Meyer, J. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilisation patterns and quality indices amongst hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti-infective Ther. 2021, 19, 1353–1366. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).