Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

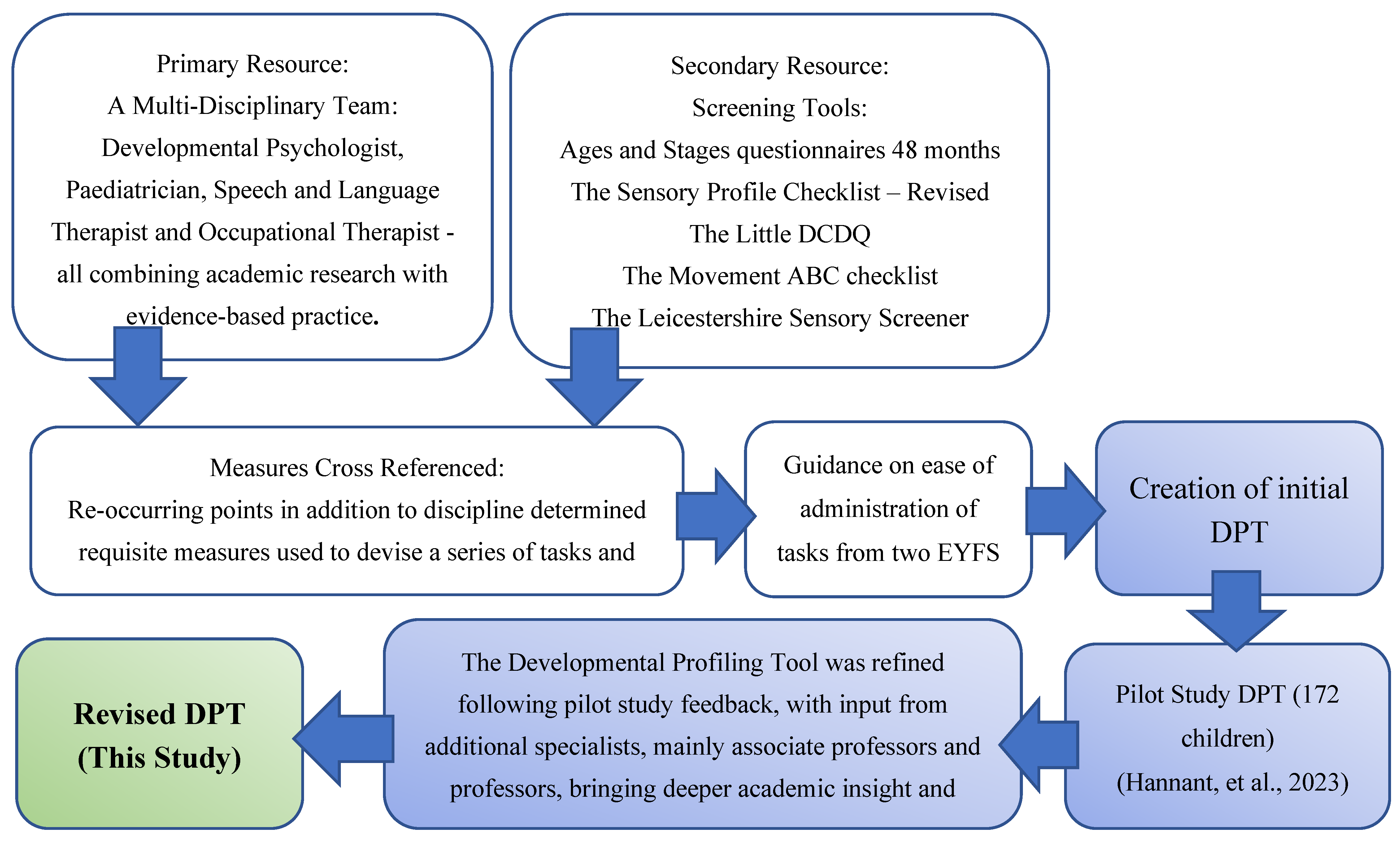

The Developmental Profiling Tool (DPT)

The Pilot Study

The Main Study

Aims

- 1)

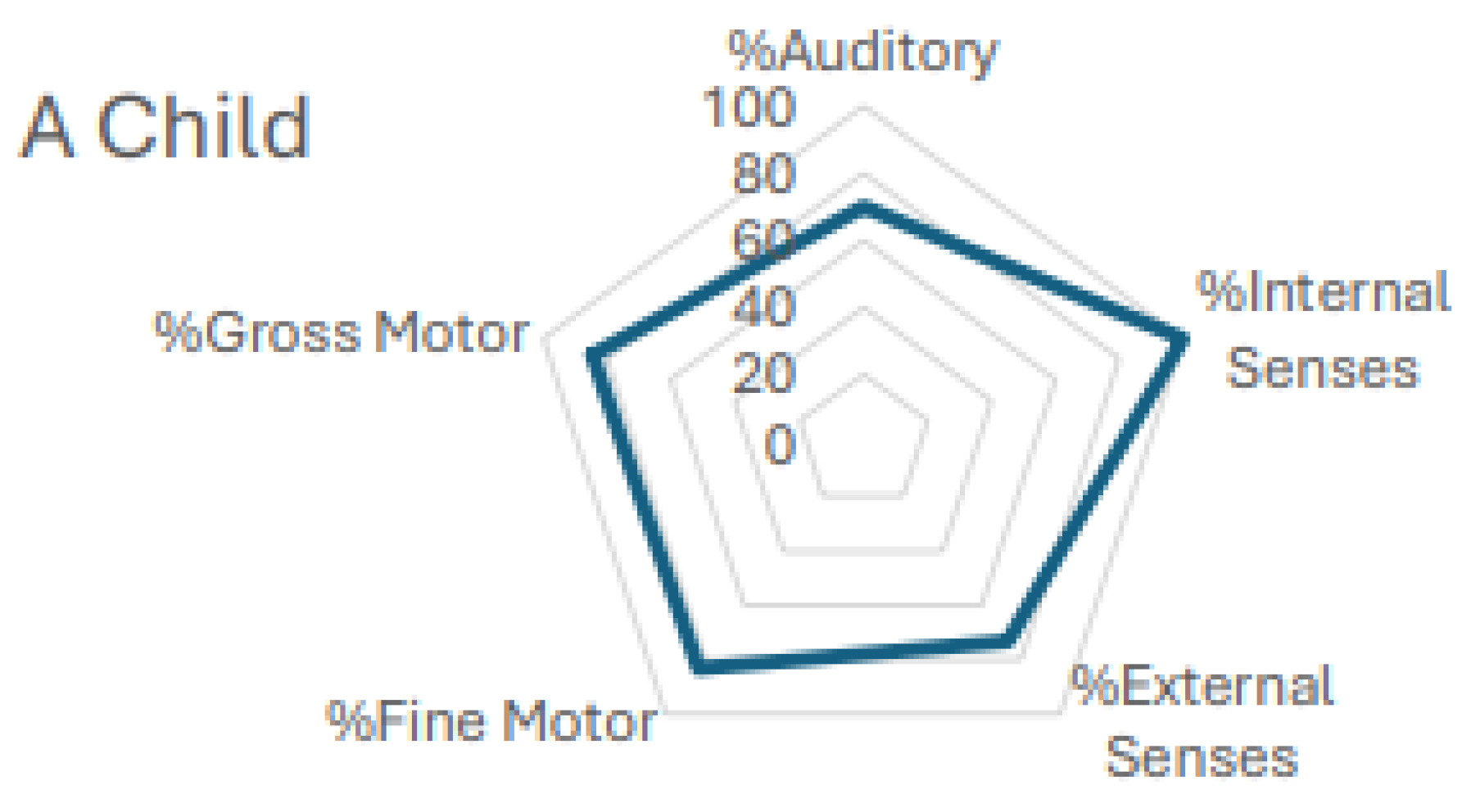

- Can the DPT reliably and validly assess multiple foundational constructs of child development at school entry?

- 2)

- Does the use of the DPT by Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) teachers support the early identification of developmental differences to enable timely intervention?

Participants

- What interested you the most?

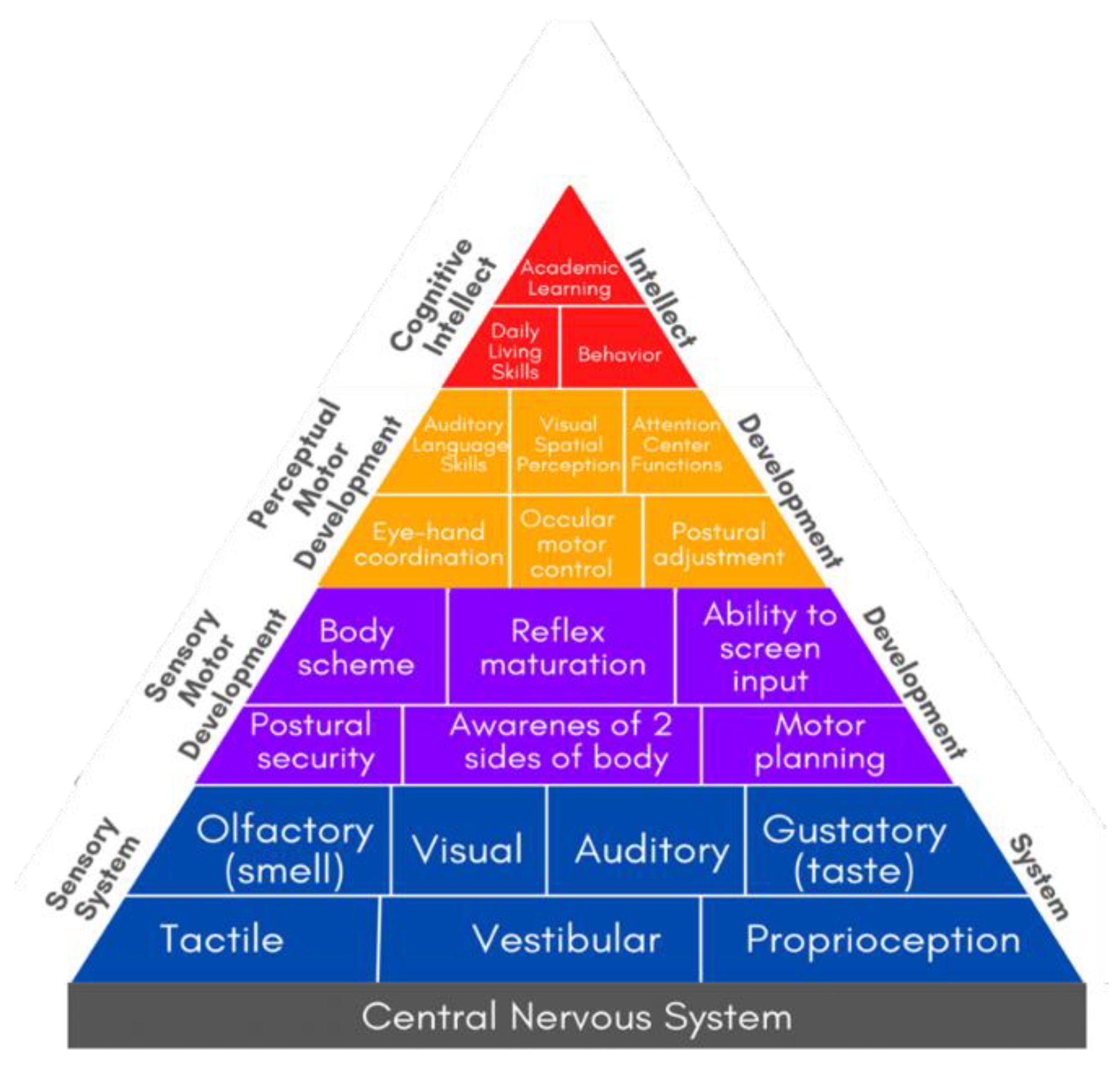

- Which area of the pyramid of learning might impact a child’s learning the most?

- What have you learnt that you did not know before?

- Has the training helped you to understand why children have barriers to learning?

- What might you do in the future as an outcome of this training?

- How has the training impacted your teaching pedagogy?

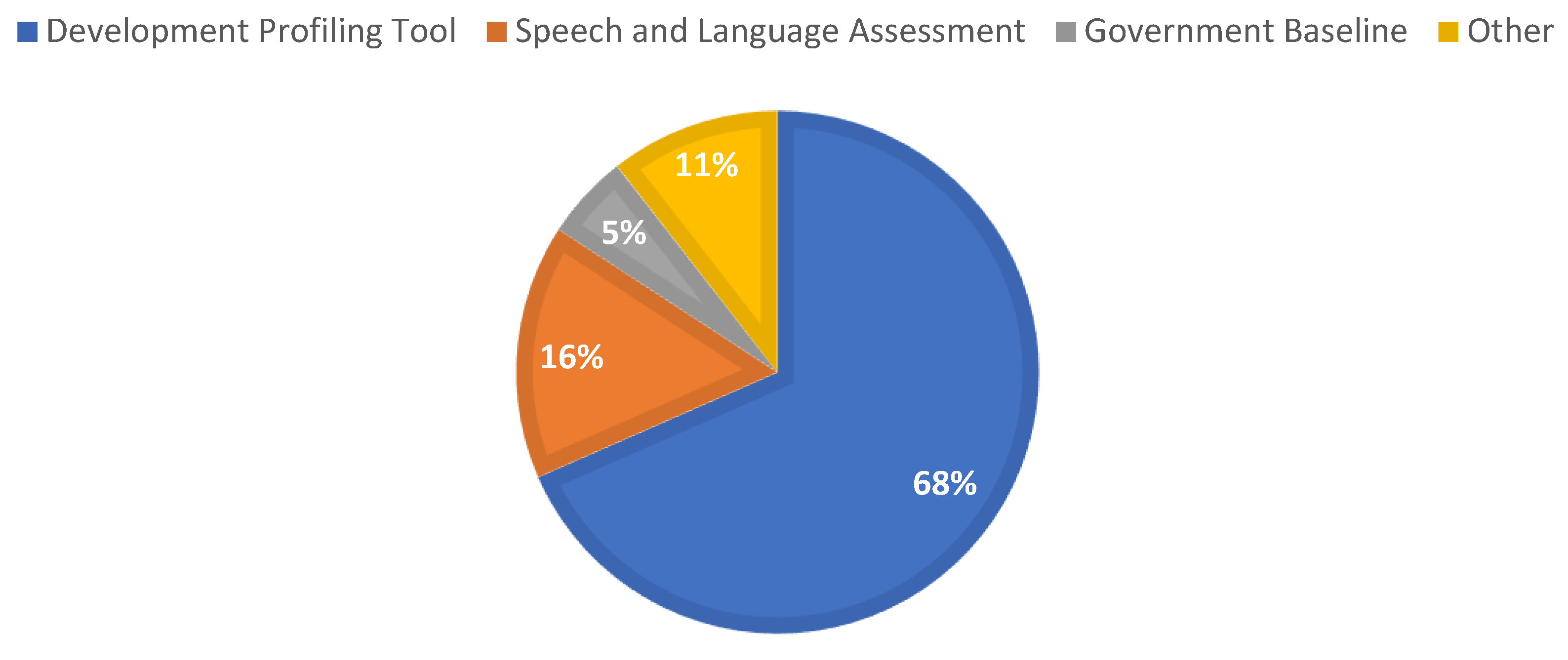

Methods

Analysis

Qualitative Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

- (a)

- Convergent validity, whether different measures of the same construct are closely aligned (Kemper, 2020) was assessed using data from the randomly selected sample of children (n=46). Paired samples correlations were conducted in SPSS (v29.0.1) to compare scores from standardised parent-reported questionnaires and SENCo-administered assessments with results from the DPT. This analysis aimed to determine the degree of alignment between external measures and the tool’s outputs

- (b)

- To assess construct validity, a bivariate correlation analysis was conducted using SPSS (v29.0.1) to explore relationships among the various constructs.

- (c)

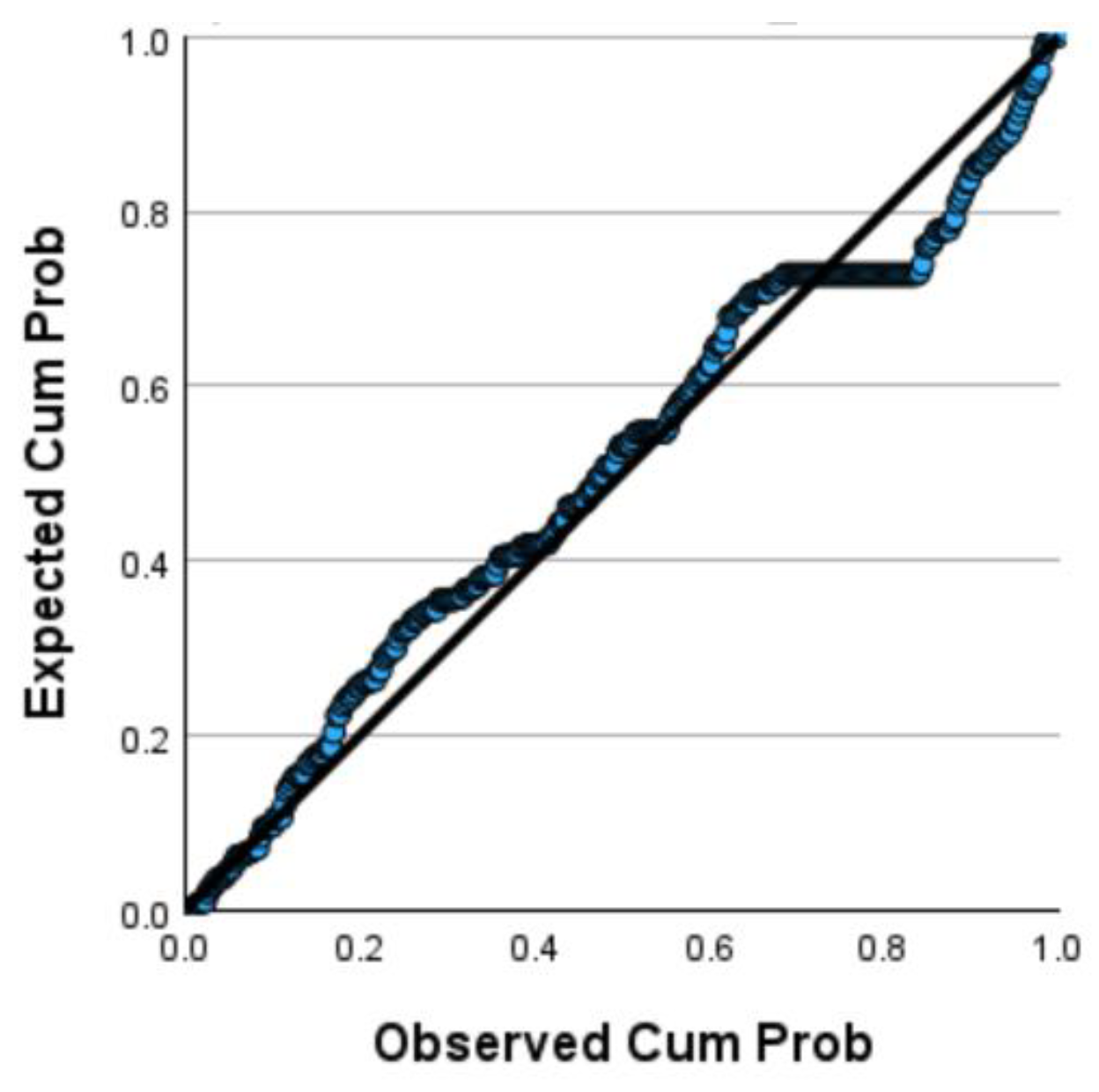

- Subsequently, a regression analysis was performed to explore whether scores on certain constructs within the tool could statistically predict outcomes on other constructs. This approach was used to examine the internal coherence of the tool and to assess whether it captured a broad and interconnected range of developmental domains. If constructs meaningfully predicted one another, it suggests that the tool reflects a comprehensive model of development, rather than isolated skills or traits. The assumptions for regression analysis were also thoroughly checked, including: outliers, identified using Cook’s Distance, with participants exceeding a value of 1.0 being excluded; multicollinearity, assessed using tolerance scores, which needed to be greater than 0.2; and homoscedasticity, examined through scatterplots of zresid versus zpred and sresid versus zpred, ensuring that PP plots did not exhibit a pronounced S-shaped curve.

- (d)

- Inter-rater reliability (evaluates the level of agreement between different raters) was measured by requesting the SENCo and EYFS teacher from each school to administer the tool to the same child so that outcomes could be compared. This was done by five schools (due to time commitments of the SENCo). Five children equated to 295 responses that were analysed using paired samples correlations in SPSS (v29.0.1).

- (e)

- Reliability - The Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20) was used in SPSS (v29.0.1) to measure how consistent responses were across all items on the tool. KR-20 is used to estimate the reliability of binary measurements, such as those used in the tool, noting whether a child was able to complete an activity successfully or not. Higher values, closer to 1.0 indicated higher reliability

Findings

EYFS teacher and SENCo Reflections on Training

Validity and Reliability of the Tool

Convergent Validity

Construct Validity

Internal Consistency

Discussion

Conclusion

Declaration of Interests

Acknowledgements

References

- Albuquerque, K. A., & Cunha, A. C. B. (2020). New trends in instruments for child development screening in Brazil: A systematic review. Journal of Human Growth and Development, 30(2), 88–196. Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP). [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. L., Hill, L. J. B., Pettinger, K. J., Wright, J., Hart, A. R., Dickerson, J., & Mon-Williams, M. (2022). Can holistic school readiness evaluations predict academic achievement and special educational needs status? Evidence from the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile. Learning and Instruction, 77, 101537. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Babu, A. G., & Sasikumar, N. (2019). Need for neurocognitive approach in teaching mathematics for children with dyscalculia. International Journal of Basic and Applied Research, 9(4), 194-200. Longman Publishing.

- Ballinger, L., (2024). New school starters not ready for learning. University of Leeds News. Date accessed [26th February 2024]. Available from: [https://tinyurl.com/ypauunyt].

- Banaschewski, T., Besmens, F., Zieger, H., & Rothenberger, A. (2001). Evaluation of sensorimotor training in children with ADHD. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 92(1), 137–149. Sage Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Barker, M., Brewer, R. and Murphy, J., 2021. What is Interoception and Why is it Important?. Front. Young Minds, 9, p.558246. Date accessed [26th February 2024]. Available from: [https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2021.558246].

- Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development, third edition: Administration manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt.

- Beery, K., Buktenica, N., Beery, N., & Keith, E. (2010). Developmental test of visual-motor integration 6th edition. Minneapolis, MN: NSC Pearson.

- Blair, C. (2002). School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. American psychologist, 57(2), 111. American Psychological Association (APA). [CrossRef]

- Boyle, T., Petriwskyj, A., & Grieshaber, S. (2018). Reframing transitions to school as continuity practices: the role of practice architectures. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(4), 419-434. Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Britto, P. R. (2012). Key to Equality: Early Childhood Development. [https://itacec.org/itadc/document/learning_resources/project_cd/International/Global%20Agreement%20-%20netotiations%20Key%20to%20Equality%20%20ECD%20Britto%20-%20Pia%20et%20al.pdf] (Accessed 5th August 2025).

- Chapman, E. (2023). Preventing unmet need from leading to school exclusion: Empowering schools to identify neurodiversity earlier (Doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds).

- Cibralic, S., Hawker, P., Khan, F., Mendoza Diaz, A., Woolfenden, S., Murphy, E., Deering, A., Schnelle, C., Townsend, S., Doyle, K., & Eapen, V. (2022). Developmental screening tools used with First Nations populations: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15627. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V. & Braun, V. (2013) Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120-123. British Psychological Society.

- Dehorter, N., & Del Pino, I. (2020). Shifting developmental trajectories during critical periods of brain formation. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 14, 283. Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Department for Education (2021), “Teachers’ Standards,” [https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/61b73d6c8fa8f50384489c9a/Teachers__Standards_Dec_2021.pdf] (Accessed: 11th March 2025).

- Department for Education (2024), Standards and Testing Agency. “Early years foundation stage profile handbook”, [https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6747436ba72d7eb7f348c08b/Early_years_foundation_stage_profile_handbook.pdf] (Accessed: 11th March 2025).

- Deprivation of Birmingham, (2019) https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/file/2533/index_of_deprivation_2019 [Accessed 11th March 2025].

- Dewey, D., Kaplan, B. J., Crawford, S. G., & Wilson, B. N. (2002). Developmental coordination disorder: Associated problems in attention, learning, and psychosocial adjustment. Human movement science, 21(5-6), 905-918. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Dizon-Ross, R. (2019). Parents’ beliefs about their children’s academic ability: Implications for educational investments. American Economic Review, 109(8), 2728-2765. American Economic Association. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W. (2014). Sensory profile 2. Bloomington, MN, USA: Psych Corporation.

- Egmose, I., Smith-Nielsen, J., Lange, T., Stougaard, M., Stuart, A. C., Guedeney, A., & Væver, M. S. (2021). How to screen for social withdrawal in primary care: An evaluation of the alarm distress baby scale using item response theory. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 3, 100038. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E., MacLennan, K., Mullally, S., & Rodgers, J. (2025). Neuro-Normative Epistemic Injustice–Consequences for the UK Education Crisis and School Anxiety. Neurodiversity, 3. SAGE Publications. [CrossRef]

- Garon-Carrier, G., Boivin, M., Lemelin, J. P., Kovas, Y., Parent, S., Seguin, J. R.,. & Dionne, G. (2018). Early developmental trajectories of number knowledge and math achievement from 4 to 10 years: Low-persistent profile and early-life predictors. Journal of school psychology, 68, 84-98. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Geffner, D., & Goldman, R. (2010). Auditory skills assessment. Pearson Assessments.

- Glascoe, F. P., Woods, S. K., & Mills, T. D. (2023). Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status - Revised (PEDS-R) Handbook. Nolensville, TN: PEDStest.com, LLC.

- Guldberg, K. (2020). Developing excellence in autism practice: Making a difference in education. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Hannant, P., Cassidy, S., Tavassoli, T., & Mann, F. (2016). Sensorimotor difficulties are associated with the severity of autism spectrum conditions. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 10, 28. Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- Hannant, P., Gartland, R., Eales, H. and Mooncey, S., 2023. A tool to profile neural, sensory and motor development in children at school entry, identifying possible barriers to learning and emotional well-being in early childhood. Support for Learning, 38(4), pp.167-177. Wiley-Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Harris, M., Franzsen, D., & De Witt, P. A. (2021). Relevance of norms and psychometric properties of three standardised visual perceptual tests for children attending mainstream schools in Gauteng. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(3), 4–13. Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA). [CrossRef]

- Hens, K., & Van Goidsenhoven, L. (2023). Developmental diversity: Putting the development back into research about developmental conditions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 986732. Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- High, P. C., & Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care and Council on School Health. (2008). School readiness. Pediatrics, 121(4), e1008-e1015.American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

- Ivanović, L., Ilić-Stošović, D., Nikolić, S., & Medenica, V. (2019). Does neuromotor immaturity represent a risk for acquiring basic academic skills in school-age children? Vojnosanitetski Pregled, 76(10), 1062–1070. University of Defence, Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Serbia. [CrossRef]

- Jahreie, J. (2022). The standard school-ready child: the social organization of ‘school-readiness’. British Journal of sociology of Education, 43(5), 661-679. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A. P., Chow, J. C., & Cunningham, J. E. (2022). A case for early language and behavior screening: Implications for policy and child development. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 9(1), 120-128. Sage Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Kautto, A., Railo, H., & Mainela-Arnold, E. (2024). Low-level auditory processing correlates with language abilities: An ERP study investigating sequence learning and auditory processing in school-aged children. Neurobiology of Language, 5(2), 341-359. MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Kay, L. (2024). ‘I feel like the Wicked Witch’: Identifying tensions between school readiness policy and teacher beliefs, knowledge and practice in Early Childhood Education. British Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 632-652. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C. J. (2020). Face validity. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp. 1540–1543). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Kindred Squared, 2023. School Readiness Report. https://kindredsquared.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Kindred-Squared-School-Readiness-Report-February-2024.pdf [Accessed 11th March 2025].

- Lipkin, P. H., Macias, M. M., Baer Chen, B., Coury, D., Gottschlich, E. A., Hyman, S. L.,. & Levy, S. E. (2020). Trends in pediatricians’ developmental screening: 2002–2016. Pediatrics, 145(4), e20190851. American Academy of Pediatrics. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L., Santos, R., Pereira, B., & Lopes, V. P. (2013). Associations between gross motor coordination and academic achievement in elementary school children. Human Movement Science, 32(1), 9–20. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P., & Soni, A. (2021). Widening the focus of school readiness for children with disabilities in Malawi: a critical review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 29(1), 97-111. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S. (2024). Sensorimotor stage of cognitive development. https://www.simplypsychology.org/sensorimotor.html [Accessed 3rd August 2025].

- Moens, M. A., Weeland, J., Van der Giessen, D., Chhangur, R. R., & Overbeek, G. (2018). In the eye of the beholder? Parent-observer discrepancies in parenting and child disruptive behavior assessments. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(6), 1147–1159. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Mon-Williams, M., Wood, M., & Taylor-Robinson, D. (2023). Addressing Education and Health Inequity: Perspectives from the North of England. A report prepared for the Child of the North APPG.

- Moodie, S., Daneri, P., Goldhagen, S., Halle, T., Green, K., & LaMonte, L. (2014). Early childhood developmental screening: A compendium of measures for children ages birth to five (OPRE Report 2014-11). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/compendium_2013_508_compliant_final_2_5_2014.pdf [Accessed March 2024].

- Mukherjee, S. B., Aneja, S., Sharma, S., & Kapoor, D. (2021). Early childhood development: A paradigm shift from developmental screening and surveillance to parent intervention programs. Indian Pediatrics, 58(Suppl 1), S64–S68. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X. S., Li, C., & Watts, T. W. (2023). Associations between preschool cognitive and behavioral skills and college enrollment: Evidence from the Chicago School Readiness Project. Developmental Psychology, 59(3), 474–486. American Psychological Association (APA). [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M., & Ríos, N. (2024). The effectiveness of early intervention programs for children with special needs. International Journal of Literacy and Education. https://www. educationjournal. [Accessed 3rd August 2025].

- Phillips, D. A., & Shonkoff, J. P. (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Academies Press.

- Portsmouth Local Offer. (2025). The Neurodiversity (ND) Profiling Tool. https://portsmouthlocaloffer.org/information/the-neurodiversity-nd-profiling-tool/ [Accessed February 2025].

- Powell, L., Spencer, S., Clegg, J., Wood, M. L., et al. (2024). A country that works for all children and young people: An evidence-based approach to supporting children in the preschool years. N8 Research Partnership.

- Rah, S. S., Jung, M., Lee, K., Kang, H., Jang, S., Park, J.,. & Hong, S. B. (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis: Real-world accuracy of children’s developmental screening tests. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(10), 1095–1109. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Rihtman, T., Wilson, B. N., & Parush, S. (2011). Development of the Little Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire for preschoolers and preliminary evidence of its psychometric properties in Israel. Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1378-1387. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, H., Lee, F., & Tomlinson, H. (2023). Leicestershire LFRMS SEA Environmental Report. https://www.leicestershire.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2024-02/Leicestershire-LFRMS-SEA-Environmental-Report.pdf [Accessed 30th October 2024].

- Sample, K. L., Hagtvedt, H., & Brasel, S. A. (2020). Components of visual perception in marketing contexts: A conceptual framework and review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 405–421. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Schonhaut, L., Maturana, A., Cepeda, O., & Serón, P. (2021). Predictive validity of developmental screening questionnaires for identifying children with later cognitive or educational difficulties: A systematic review. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 698549. Frontiers Media. [CrossRef]

- Squires, J., Bricker, D. D., & Twombly, E. (2009). Ages & stages questionnaires (3rd ed., pp. 257–182). Brookes Publishing Company. [CrossRef]

- Steinhoff, J. M. (2024). Supporting Interoceptive Learning Across Environments: A Guide For Educators And Caregivers. University of North Dakota.

- Taanila, A., Murray, G. K., Jokelainen, J., Isohanni, M., & Rantakallio, P. (2005). Infant developmental milestones: A 31-year follow-up. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 47(9), 581–586. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Torres, E. B., & Whyatt, C. (Eds.). (2017). Autism: the movement sensing perspective. CRC Press.

- Warburton, M., Wood, M. L., Sohal, K., Wright, J., Mon-Williams, M., & Atkinson, A. L. (2024). Risk of not being in employment, education or training (NEET) in late adolescence is signalled by school readiness measures at 4–5 years. BMC public health, 24(1), 1375. Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S. W., & Shellenberger, S. (1996). How does your engine run? A leader’s guide to the Alert Program for self-regulation. TherapyWorks, Inc.

- Yochman, A., Ornoy, A., & Parush, S. (2006). Co-occurrence of developmental delays among preschool children with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 48(6), 483–488. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Zubler, J. M., Wiggins, L. D., Macias, M. M., Whitaker, T. M., Shaw, J. S., Squires, J. K.,. & Lipkin, P. H. (2022). Evidence-informed milestones for developmental surveillance tools. Pediatrics, 149(3). American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). [CrossRef]

| Heritage | % of children |

|---|---|

| White | |

| English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British | 46 |

| Irish | 0 |

| Gypsy or Irish Traveller | 0 |

| Roma | 0 |

| Any other White background | 6 |

| Black | |

| African | 3 |

| Caribbean | 0 |

| Any other Black, Black British, or Caribbean background | 6 |

| Asian or Asian British | |

| Indian | 7 |

| Pakistani | 13 |

| Bangladeshi | 3 |

| Chinese | 3 |

| Any other Asian background | 2 |

| Mixed or Multiple Ethnic Groups | |

| White and Black Caribbean | 0 |

| White and Black African | 1 |

| White and Asian | 3 |

| Any other Mixed or Multiple Ethnic background | 1 |

| Other Ethnic Groups | |

| Arab | 2 |

| Any other ethnic group | 5 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 53 |

| Female | 47 |

| Construct | Parent-reported Questionnaire Measured Against | Psychometrics |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory responsivity | Sensory Profile-2 (Dunn, 2014) | Sample 1,791 children (birth to 14 years) Internal consistency (.60–.90); inter-rater reliability (.49–.89), test-retest reliability (.87–.97), and high content and construct validity (Licciardi & Brown, 2021). |

| Coordination | Little DCDQ (Rihtman et al., 2011) | Sample 353 children (3–4 years) .96 test-retest reliability, .94 internal consistency, and strong construct and concurrent validity (Wilson et al., 2015). |

| Interoception | Questionnaire (Steinhoff, 2024) | Not standardised – no standardised questionnaire availability. |

| Construct | SENCo-reported Assessment | Psychometrics |

| Auditory skills | Speech Discrimination in Noise and Mimicry subtests in the Auditory Skills Assessment (Geffner & Goldman, 2010) | 225 children (3 years 6 months to 4 years 11 months); Internal consistency of .60 and test-retest reliability of .64 Limited Auditory Discrimination Assessment availability. |

| Visual perception | Visual Perception form BEERY VI form (Beery, Buktenica, & Beery, 2010) | High reliability: Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency at 0.89, test-retest reliability at 0.88, and inter-scorer reliability at 0.93. (Harris et al., 2021). |

| Thematic Area | First Order Theme | Examples of Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Shifting Perspectives on Learning Barriers | Better Understanding of Barriers to Learning: Reflecting a shift in how educators recognise and interpret developmental challenges. | ‘…a better understanding of why some children have different barriers to learning.’ ‘I found it interesting to see how many barriers to learning there are.’ ‘I’ve spent time reflecting back to children I have taught previously, now recognising those difficulties’ |

| Additional considerations needed when teaching: Highlighting increased awareness of the complexity behind learning and the need for tailored support. | ‘Knowing how much you need to consider when supporting children with their listening skills…’ ‘…how you can’t have one skill without other skills, like building a house.’ ‘Think about each child and how each child can be scaffolded based on fundamental skills,’ |

|

| More confident to identify children with difficulties / delays in development: Indicating growing confidence in recognising early signs of developmental delay. | ‘I am grateful to have joined this training and feel confident and ready to identify and support these early signs within our new Reception intake this year.’ ‘I feel much more confident with the other areas and believe that in the classroom I will be able to see why there are potentially barriers to some children learning.’ ‘It made me think of several children I have known and taught over the years and wished I’d had this training sooner.’ |

|

| Deepening Professional Understanding of Child Development | Able to recount new learning and concepts: Showing internalisation of new developmental knowledge and frameworks. | ‘I was really interested in interception - how children are not aware when they are full or hurt.’ ‘The stages of the pyramid was really interesting to learn about’ ‘The amount of processes and stages required within the body to carry out seemingly simple tasks’ ‘Sensory responses and coordination are the foundations of development.’ ‘…a better understanding of the senses.’ ‘…how the brain and spinal cord work together (Sensory, Relay, and Motor neurons) to build a foundation for movement and coordination.’ |

| Valuable Learning Experience: Demonstrating the perceived relevance and impact of the training on professional practice. | ‘I shall now look closely at each of the pyramid stages when observing and making judgements on a child’s learning. It will impact my teaching going forward as I will be more aware of the classroom setting/environment.’ ‘It would be a valuable learning experience for all colleagues.’ ‘The training is very informative to the initial stages of development which most practitioners are unaware of. This training would be great to share with all staff so that they have a thorough understanding of the underpinning skills that need to be in place in order for children to learn effectively.’ ‘I found the training very interesting and could relate a lot of this to the children.’ |

| Thematic Area | First Order Theme | Examples of Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Reframing Assessment Priorities | Consideration as to what should be assessed at baseline: Reflecting a shift in educators’ thinking about the scope and purpose of baseline assessments. | ‘It has made me reconsider what we should assess during baseline assessments.’ ‘Using the development tool had initially helped with a baseline assessment when the children first started school.’ ‘As a teacher it has made me re-evaluate how we assess children at Baseline, taking more consideration of the children’s development.’ |

| Measurement of the fundamental skills needed to learn: Highlighting increased awareness of developmental foundations that underpin learning readiness. | ‘It has made me more aware of the fundamental developmental skills that children need in order to be able to access education.’ ‘It has given me insight further into the development of the children we have in our EYFS through assessment’ ‘The team were able to raise SEND concerns for some children after completing these assessments’ |

|

| Enhancing Early and Targeted Support | Early intervention is key: Emphasising the value of identifying needs early to enable timely and effective support. | ‘The earlier we learn how a child learns and what barriers they have to learning, the earlier we can intervene.’ ‘We have been able to deliver targeted intervention to children earlier than previous years and use the suggested resources for maximum impact’ ‘It has also helped to support and identify potential SEND monitoring concerns right from when the children start Primary School.’ |

| Tailored intervention: Showing how assessment outcomes informed more targeted, needs-based support strategies. | ‘The development tool has opened our eyes beyond the curriculum to help children through tailored interventions.’ ‘I was able to use the assessment outcomes, in some cases with the whole class, which was incredibly helpful, particularly in guiding our support in gross and fine motor skills, as well as spatial awareness.’ ‘The links once the assessment was completed to further support and resources have been invaluable.’ |

| Paired Sample (n = 46) | Correlation | Significance One-Side p |

|---|---|---|

| DPT Auditory Skills and ASA Auditory Discrimination | .116 | .22 |

| DPT Auditory Skills and ASA Mimicry | .061 | .35 |

| DPT Internal Senses and SP2 Internal Senses | -.680 | <.001 |

| DPT External Senses and SP2 External Senses | .802 | <.001 |

| DPT Interoception and Interoceptive Skills Questionnaire | -.243 | .05 |

| DPT Visual perception and BEERY VI Visual perception | .463 | <.001 |

| DPT Fine motor skills and DCDQ Fine Motor Skills | .509 | <.001 |

| DPT Gross motor skills and DCDQ Gross Motor Skills | .435 | .001 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 DPT Auditory Skills Total | 77.18 | 22.77 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 DPT Internal Senses Total | 90.58 | 16.87 | .384** | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 DPT Interception Total | 86.24 | 25.03 | .528** | .606** | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| 4 DPT External Senses Total | 87.64 | 21.82 | .477** | .735** | .669** | 1 | - | - | - |

| 5 DPT Visual Perception Total | 79.78 | 30.29 | .535** | .371** | .367** | .391** | 1 | - | - |

| 6 DPT Fine Motor Skills Total | 75.12 | 28.73 | .548** | .478** | .449** | .494** | .665** | 1 | - |

| 7 DPT Gross Motor Skills Total | 84.56 | 22.56 | .432** | .562** | .557** | .603** | .485** | .647** | 1 |

| Predicted Construct | Constructs Able to Predict Outcome with Significance | Multiple Regression Analysis Results When Combining All Constructs |

|---|---|---|

| Auditory skills | Interoception, external senses, visual perception and fine motor skills | R=.670, R2= .449 : F(6-291) = 39.55, p<.001 45 % of the variance explained. |

| Internal Senses | Interoception and external senses | R=.763, R2= .583 : F(6-291) = 67.77, p<.001 58% of variance explained |

| Interoception | Auditory skills, internal senses, external senses and gross motor skills | R=.738, R2= .554 : F(6-291) = 57.86, p<.001 55% of variance explained |

| External Senses | Auditory skills, internal senses, interoception and gross motor skills | R=.804, R2= .647 : F(6-291) = 88.79, p<.001 65% of variance explained |

| Visual Perception | Auditory skills and fine motor skills | R=.698, R2= .487 : F(6-291) = 45.98, p<.001 49% of variance explained |

| Fine Motor Skills | Auditory skills, visual perception and gross motor skills | R=.779, R2= .606 : F(6-291) = 74.64, p<.001 61% of variance explained |

| Gross Motor Skills | Interoception, external senses and fine motor skills | R=.743, R2= .552 : F(6-291) = 59.69, p<.001 55% of variance explained |

| Paired Sample (5 children, 59 items each: n = 59 for each pair) | Correlation | Significance One-Side p |

|---|---|---|

| School A SENCo _ School A EYFS Teacher | 1 | <001 |

| School B SENCo _ School B EYFS Teacher | .390 | .001 |

| School C SENCo _ School C EYFS Teacher | .894 | <.001 |

| School D SENCo _ School D EYFS Teacher | .331 | .005 |

| School E SENCo _ School E EYFS Teacher | .696 | <.001 |

| Construct | Items (n) | Cronbach’s alpha | Description. |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPT Auditory Skills | 12 | .835 | Good Internal Consistency |

| DPT Internal Senses | 13 | .810 (.801 before item removed) |

Good Internal Consistency |

| DPT Interoception | 4 | .695 | Acceptable Internal Consistency |

| DPT External Senses | 6 | .715 | Good Internal Consistency |

| DPT Visual Perception | 4 | .743 | Good Internal Consistency |

| DPT Fine Motor Skills | 7 | .796 | Good Internal Consistency |

| DPT Gross Motor Skills | 13 | .837 | Good Internal Consistency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).