1. Introduction

Power steering fluids (PSFs) are essential components in hydraulic steering systems, facilitating smooth vehicle manoeuvrability and reducing driver effort [

1]. These fluids are exposed to various operational stresses, including mechanical wear and thermal degradation. However, there are evidence that suggest the potential of microbial contamination playing a significant role in lubricating fluids such as PSF [

2].

Microbial contamination in lubricants, including PSFs, is primarily caused by bacteria such as Pseudomonas species and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) [

3,

4]. These microorganisms can lead to biodegradation processes that alter fluid characteristics, potentially compromising the performance and longevity of steering systems. While the effects of microbial growth on lubricating fluids have been observed, including significant pH reductions and viscosity changes [

5], the full extent of microbial diversity in PSFs and its impact on fluid degradation remains poorly understood, particularly in comparison to other lubricants. The biodegradation of lubricants is also a critical environmental concern, especially in marine and agricultural settings where oil leaks can have severe ecological consequences [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Research on bioremediation of oil sludge has shown that microbial consortia can degrade up to 90% of hydrocarbons in 6 weeks, highlighting the potential for natural biodegradation processes [

10]. However, the rate and extent of biodegradation can vary significantly between different types of lubricants and environmental conditions [

11]. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) is an advanced analytical method used to analyze the full compositional profile of petroleum hydrocarbons and organic substances. It provides excellent selectivity by identifying individual compounds based on their unique mass spectra and retention times. This technique not only detects specific target compounds but also categorizes complex and simple hydrocarbon mixtures into distinct groups. As a result, GC-MS serves as a crucial tool for the detailed analysis of petroleum-derived substances, offering in-depth information about their chemical composition and structure [

12].

This study aims to address the following objectives: (1) identify the bacterial and fungi communities present in used PSFs. (2) Correlate the presence of specific microbial species with changes in PSF properties. (3) Confirm the biodegradation rate using gas chromatography. (4) Assess the potential environmental implications of PSF biodegradation in the context of lubricant leaks and disposal. We hypothesize that specific microbial species contribute to PSF degradation independently without external parameters like temperature, wear and tear particles, leading to accelerated deterioration of fluid performance. To test this hypothesis, we isolated microorganisms from PSFs collected from three vehicles with varying mileage and service histories, representing a range of real-world operating conditions. These isolates were then characterized and introduced into new, unused PSFs from different commercial brands to evaluate their biodegradation capabilities under controlled conditions, independent of other external factors such as temperature and mechanical wear. By analyzing the microbial community composition and tracking fluid property changes, this study aims to determine the microbial organism responsible for this process and the rate of biodegradation of the power steering fluids with respect to microorganism in automobiles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The present study was conducted to evaluate microbial biodegradation of unused power steering fluids during a 28-day incubation period with microbial species isolated from used power steering fluids. Biodegradation activity was assessed using microbiological and physicochemical techniques, including Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry(GC-MS). This method was adopted and modified from Maduka and Okpokwasili (2016) [

5].

2.2. Sample Collection

Used power steering fluids were aseptically collected with syringes into sterile bottles from vehicles in use for over two years, while unused fluids were purchased from retail stores. Fluid brands were labelled Abro Power Steering Fluid, Oando ATF Dexron II, and Sea Max ATF Dexron III.

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

2.3.1. Isolation and Identification of Oil Degrading Microorganisms

Microorganisms were isolated using Nutrient Agar (NA) and Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA). NA was supplemented with nystatin (50 µg/mL) to inhibit fungal growth, while PDA was supplemented with lactic acid (50 µg/mL) to inhibit bacterial growth. Used PSF samples were inoculated on agar plates, incubated at 30–31°C for 48 hours, and colony counts were recorded.

Selected bacterial isolates were subcultured and characterized using Gram staining, biochemical tests (oxidase, catalase, motility, indole, citrate utilization, and hydrogen sulphide production), and carbohydrate fermentation. Fungal isolates were identified through macroscopic and microscopic observation.

The utilization (screening) test for isolated microorganisms on power steering fluids was carried out in modified mineral salt medium similar to an earlier reported protocol [

4]. The MSM used for microbial growth contained the following components (per liter of distilled water): NaCl (10.0 g), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.42 g), KCl (0.29 g), KH₂PO₄ (0.83 g), NaHPO₄ (1.25 g), NaNO₃ (0.42 g), and agar (15.0 g). The pH was adjusted to 7, and the medium was autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes.

It should be noted that NA and PDA were used only for microbial isolation, while degradation ability was tested exclusively in MSM supplemented with PSF as the sole carbon source.

2.4. Biodegradation Experiments

2.4.1. Screening for Fluid Utilization

Isolated microorganisms were inoculated into MSM containing 0.1 mL of power steering fluid as the sole carbon source. Flasks were incubated at room temperature for 28 days, in accordance with the ASTM standard (ASTM D5864) for biodegradation testing [

13], with microbial growth monitored visually for turbidity.

2.4.2. Growth Monitoring

In separate experiments, 2ml power steering fluids were supplemented into MSM, and microbial growth parameters were monitored weekly over a 28-day incubation period, consistent with ASTM D5864 methodology [

13]. Measurements included optical density (OD₆₀₀), pH, and total viable counts. Biodegradation was analyzed by Gas Chromatography.

2.4.3. Mixed-Culture Studies

A microbial consortium was developed using the isolated strains. Mixed cultures were incubated in MSM with power steering fluids, and growth parameters were recorded as described above.

2.5. Physicochemical Analysis

The following physicochemical properties were analyzed:

2.6. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

Post-incubation, microbial cultures were centrifuged at 9,000 RPM for 1 hour to obtain cell-free supernatants. The residual hydrocarbon content was extracted with hexane, dried using a rotary evaporator at 80°C, and analyzed using a GC-MS device (Agilent 6890N coupled with a 5973N MSD) with a Restek VMS capillary column. Biodegradation efficiency was calculated based on hydrocarbon residue areas using established equations [

14] below:

2.7. Quality Control

A validated and standardized Laboratory procedure was followed to assure data quality at all stages of the investigation (preanalytical, analytical and post analytical). The culture media were produced following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The results were statistically evaluated following double sampling. The mean values were then obtained. One-way ANOVA was employed to examine the differences across the groups, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the microbial biodeterioration of power steering fluids (PSF) used in automobiles, specifically examining whether microorganisms are responsible for the spoilage of these fluids. The results of the research indicated that bacterial and fungal counts were higher in used fluids compared to unused fluids, with bacterial counts generally exceeding fungal counts across all the samples.

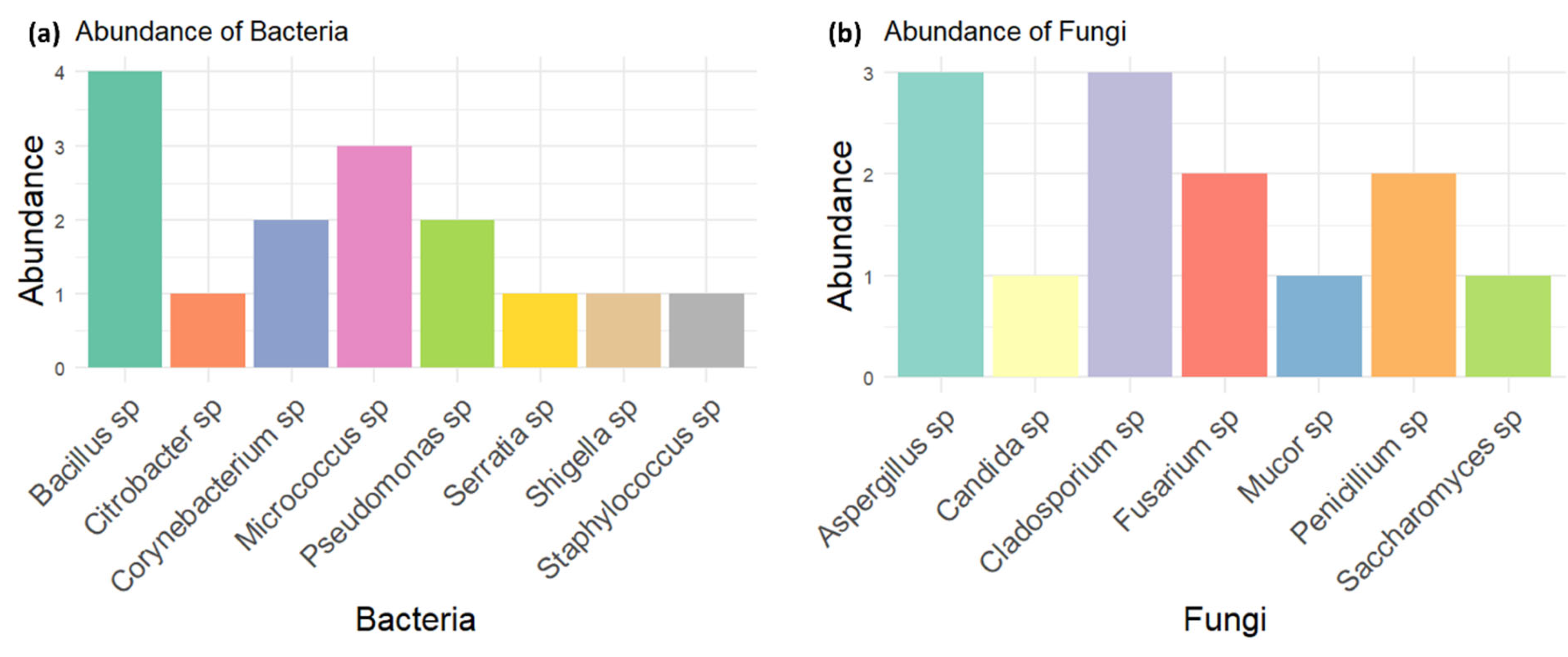

Figure 1.

Relative abundance of bacterial (a) and fungal (b) species identified in used power steering fluids. Bacillus sp. and Cladosporium sp. are the most prevalent among bacteria and fungi, respectively, while other species show varying levels of abundance.

Figure 1.

Relative abundance of bacterial (a) and fungal (b) species identified in used power steering fluids. Bacillus sp. and Cladosporium sp. are the most prevalent among bacteria and fungi, respectively, while other species show varying levels of abundance.

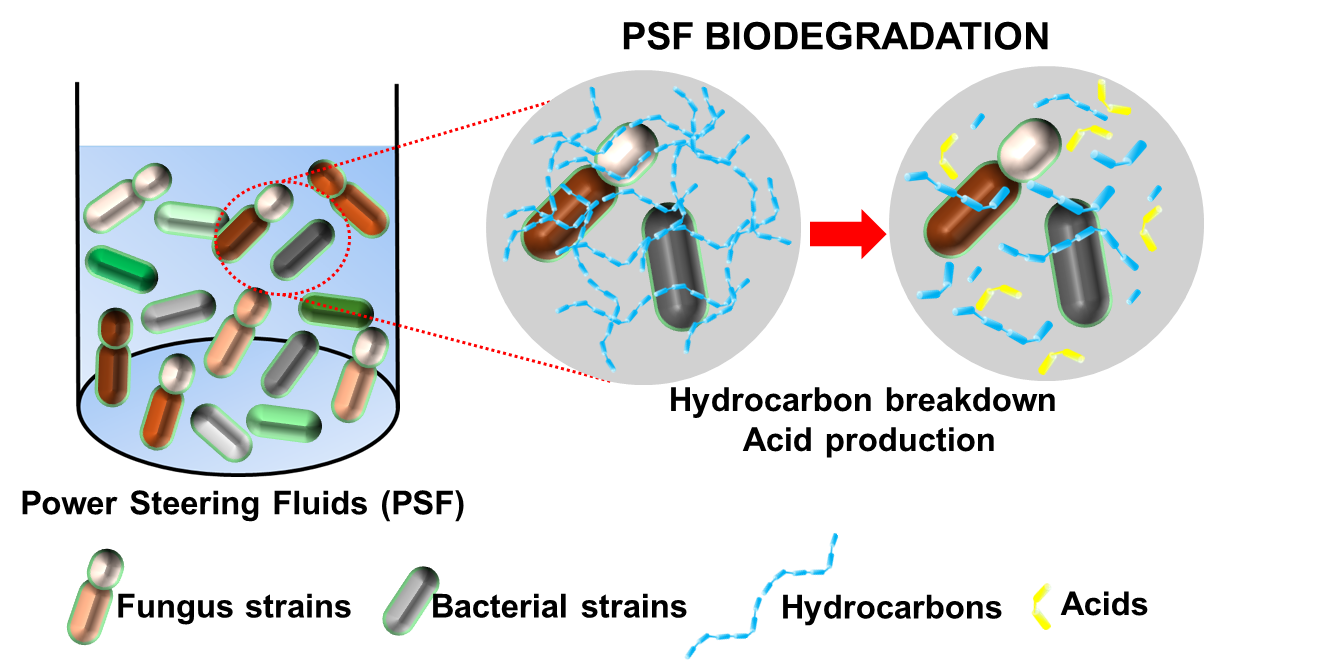

3.1. Microbial Degradation of Hydrocarbons

The presence of microorganisms in the fluids contributes to their involvement in the degradation process. Hydrocarbons, which are a major component of petroleum-based products such as power steering fluids, present unique challenges for both microorganisms and researchers. Hydrocarbons, being hydrophobic, require specialized metabolic pathways for their degradation [

15]. Malik and Ahmed [

16] emphasized that the degradation rate of hydrocarbons by microorganisms depends on various factors, including temperature, concentration of the substrate, and microbial concentrations. In this study, bacterial and fungal microorganisms were isolated from deteriorated power steering fluids that had been exposed to environmental conditions for over a year.

The microbial isolates identified in this study included several bacterial species such as Corynebacterium sp., Citrobacter sp., Bacillus sp., Serratia sp., Micrococcus sp., Pseudomonas sp., Shigella sp., and Staphylococcus sp., as well as fungal species like Candida sp., Aspergillus sp., Penicillium sp., Fusarium sp., Cladosporium sp., Saccharomyces sp., and Mucor sp (figure 1). This is in line with previous studies [

5], where similar bacterial and fungal species were isolated from lubricating and brake fluids.

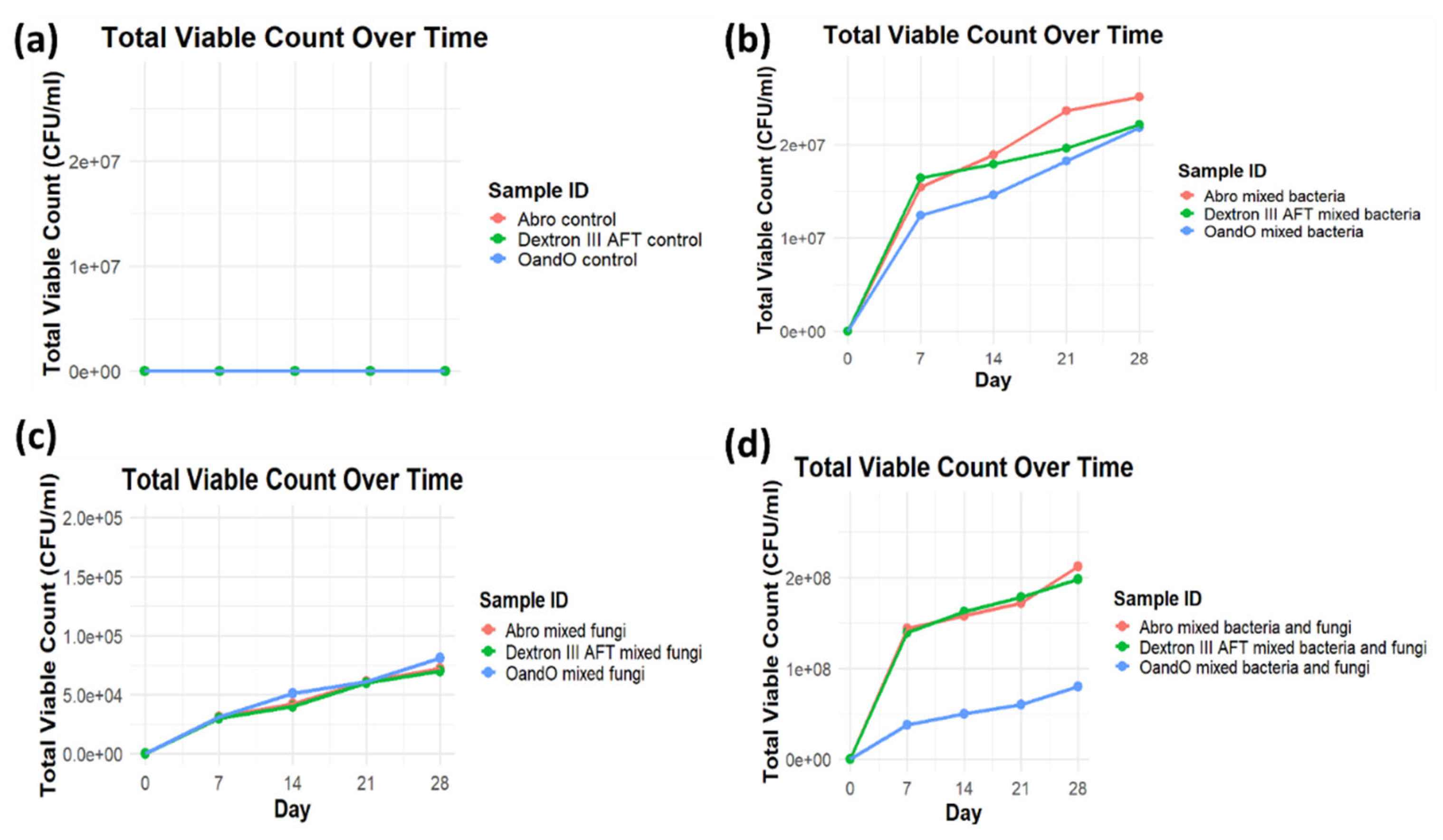

Figure 2.

Total viable count (TVC) of microorganisms in different power steering fluids over 28 days. (a) Control samples showed no microbial growth. (b) Bacterial growth increased steadily over time. (c) Fungal growth was lower compared to bacterial growth but still showed a gradual increase. (d) Co-cultured bacteria and fungi exhibited the highest microbial proliferation, particularly in Abro and Dextron III AFT fluids.

Figure 2.

Total viable count (TVC) of microorganisms in different power steering fluids over 28 days. (a) Control samples showed no microbial growth. (b) Bacterial growth increased steadily over time. (c) Fungal growth was lower compared to bacterial growth but still showed a gradual increase. (d) Co-cultured bacteria and fungi exhibited the highest microbial proliferation, particularly in Abro and Dextron III AFT fluids.

3.1.1. Role of Bacteria in Biodeterioration

The dominance of Bacillus and Micrococcus species in this study aligns with earlier reports by Maduka and Okpokwasili [

4,

5] and Udeani et al., [

17], who identified these bacteria as prominent hydrocarbon utilizers and have demonstrated their ability to degrade lubricating fluids such as brake fluids [

18]. The formation of spores by these Gram-positive bacteria likely contributes to their survival in extreme environmental conditions, including elevated temperatures common in automobile systems. This is particularly relevant in the case of power steering fluids, which experience higher temperatures during vehicle operation, allowing these microorganisms to persist. Beyond spore formation, bacteria contribute directly to biodeterioration by metabolizing hydrocarbon components of the fluid, producing organic acids and biosurfactants that can alter fluid chemistry, emulsify oil–water mixtures, and accelerate corrosion of system components. In addition, biofilm formation on surfaces can enhance localized degradation and protect microbial consortia from fluid additives, thereby prolonging their activity in PSF environments. [

19,

20]

3.1.2. Role of Fungi in Biodeterioration

Fungal isolates such as Aspergillus, Candida, Saccharomyces, Fusarium, Penicillium, Cladosporium, and Mucor were also found in the used power steering fluids. The presence of fungi suggests their ability to utilize the fluid as a source of carbon and energy, leading to the deterioration of the fluid. Fungi, in particular, are known to produce extracellular enzymes that allow them to degrade hydrocarbons [

21]. In this study, Aspergillus and Cladosporium had the highest recurrence, followed by Penicillium and Fusarium. Conversely, Saccharomyces, Mucor, and Candida had the lowest occurrences in the fluids. These fungal species have been identified in other studies as efficient hydrocarbon degraders [

18].

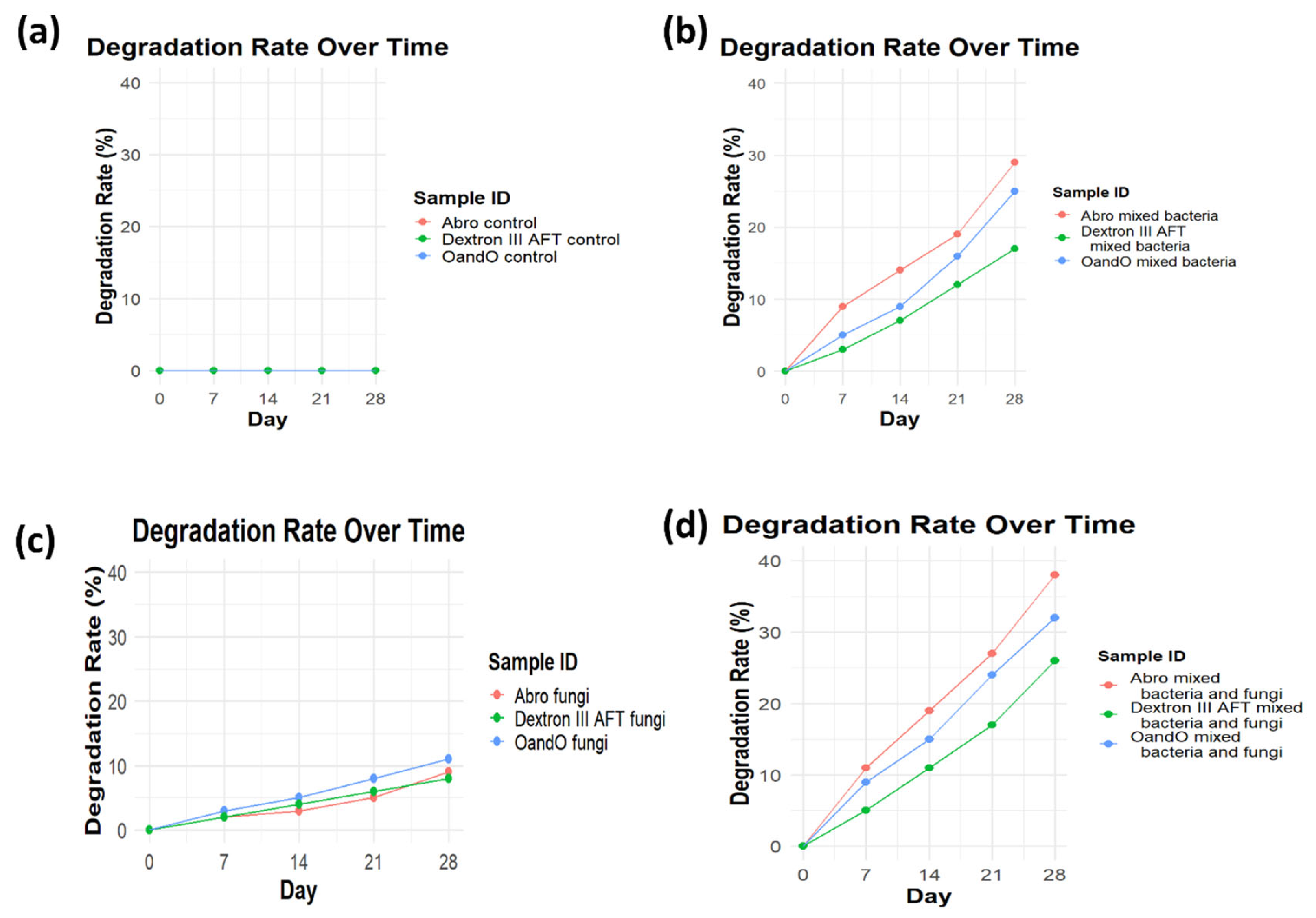

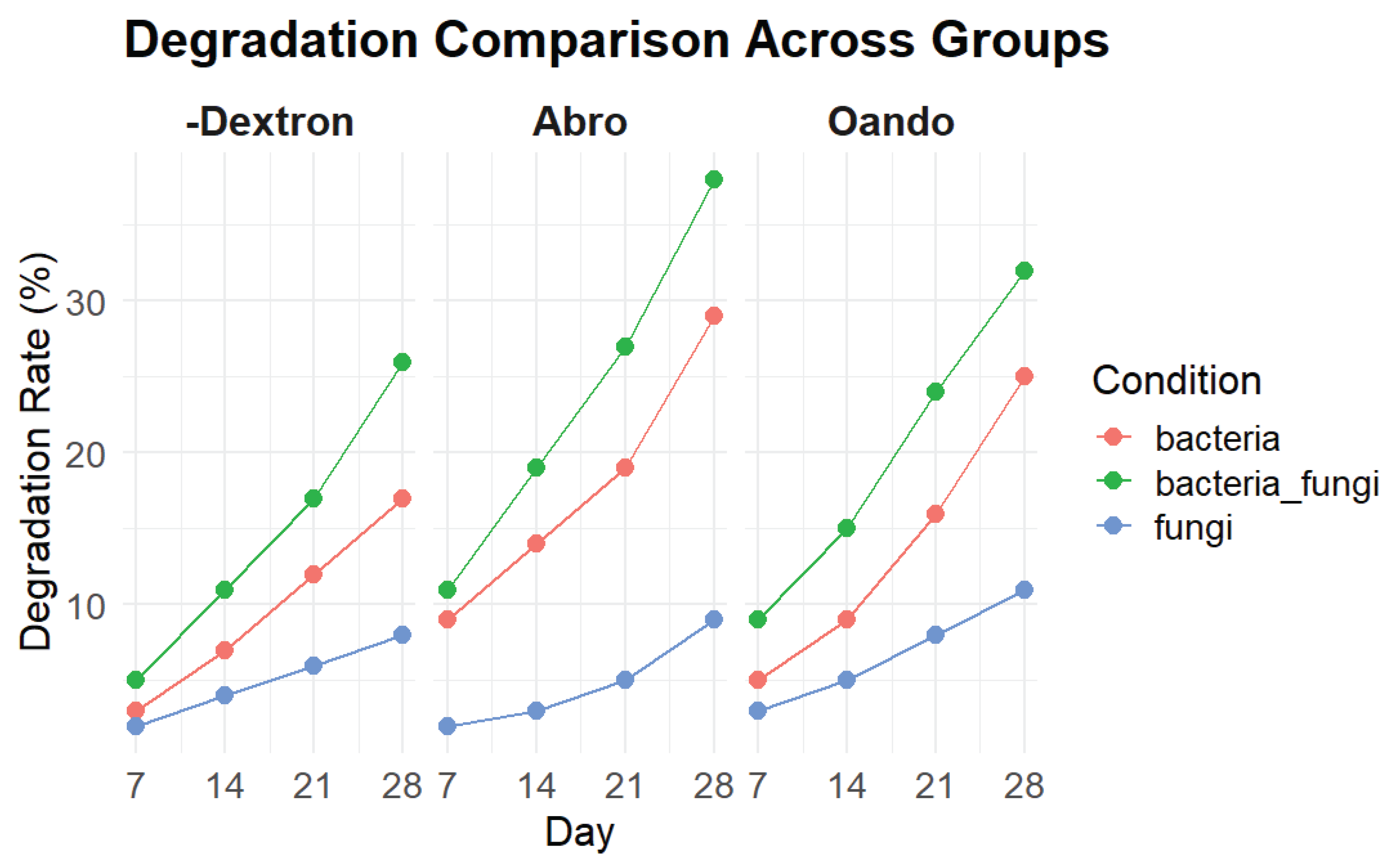

Figure 3.

Degradation rate (%) of power steering fluids (PSFs) over 28 days under different microbial conditions. (a) No degradation in control samples. (b) Bacteria accelerated degradation, with Abro PSF showing the highest rate. (c) Fungal degradation was lower than bacteria. (d) Combined bacteria and fungi led to the highest degradation, especially in Abro and OandO PSFs.

Figure 3.

Degradation rate (%) of power steering fluids (PSFs) over 28 days under different microbial conditions. (a) No degradation in control samples. (b) Bacteria accelerated degradation, with Abro PSF showing the highest rate. (c) Fungal degradation was lower than bacteria. (d) Combined bacteria and fungi led to the highest degradation, especially in Abro and OandO PSFs.

The higher occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium is significant, as these fungi are well-known for their ability to degrade complex hydrocarbons and are commonly associated with biodeterioration processes in various petroleum-based products. This aligns with the findings of Maduka and coworkers [

22] regarding Aspergillus flavus, a microorganism capable of degrading commercial brake fluid. Their study highlighted that the stability, viscosity, and pH of the fluid are key factors that can accelerate the degradation process. The degradation of power steering fluids by fungi and bacteria leads to the breakdown of the fluid’s composition, decreasing its integrity and making it less effective in its function.

3.2. Growth and Utilization of Power Steering Fluids

The study further investigated the rate of microbial utilization of unused power steering fluids. The results revealed that the utilization rate was highest in mixed bacterial and fungal cultures, followed by bacterial cultures alone and fungi alone. This pattern was reflected in the Total Viable Count (TVC), optical density, and pH readings. The increase in TVC and the degradation rate over time (figures 2a-d & 3a-d) and optical density indicated that the microorganisms were actively growing and multiplying as they utilized the power steering fluids as a carbon source. This was particularly evident in the mixed cultures, which exhibited the highest turbidity, suggesting that both bacteria and fungi together played a synergistic role in the biodegradation process. Individual microorganisms usually metabolize a limited range of hydrocarbon substrates. However, a diverse community of bacteria and fungi is often essential to provide the comprehensive metabolic capabilities required for the complete degradation of complex hydrocarbon mixtures [

23]. This study emphasizes the pivotal role of each member within a microbial community, which frequently depends on interactions with other species or strains for survival. Furthermore, this research demonstrated the bacterial consortium's remarkable efficiency in biodegrading engine oil hydrocarbons.

3.3. pH and Optical Density (OD) Changes in the Microbial Culture Media

The results of the study illustrate the dynamic interactions between microbial activity and the biodegradation of hydrocarbons in power steering fluids (PSFs), as reflected in changes in pH and optical density (OD) over time (

Table 1a-c). These findings emphasize the critical role of microbial communities in breaking down hydrocarbons and producing measurable by-products during the degradation process.

3.3.1. Changes in pH:

The pH of the culture media containing power steering fluids decreased as microbial growth progressed, reflecting the acidic by-products of hydrocarbon degradation. In the case of Oando PSF, the control group showed a minor pH reduction from 7.7 to 7.4, indicating minimal chemical changes in the absence of active microbial metabolism. However, in the bacterial cultures, the pH decreased significantly from 7.5 to 6.5, signifying robust hydrocarbon degradation. The fungal cultures experienced a similar pH decline from 7.4 to 6.6, while the mixed bacterial and fungal cultures exhibited the most pronounced change, with pH dropping from 7.1 to 6.1. This trend underscores the enhanced degradation capacity of mixed cultures, likely due to synergistic interactions between bacteria and fungi that amplify hydrocarbon breakdown.

In Abro PSF, similar to Oando, the control group also exhibited a slight pH reduction from 7.6 to 7.2, suggesting stability in the absence of microbial influence. In contrast, the bacterial cultures showed a substantial decrease in pH from 7.4 to 6.3, reflecting active microbial growth and hydrocarbon utilization. Similarly, the fungal cultures experienced a decline from 7.3 to 6.2. The mixed cultures demonstrated the greatest pH drop, from 7.4 to 6.0, indicating that the combined metabolic activities of bacteria and fungi enhance the efficiency of hydrocarbon degradation. These results are consistent with the patterns observed in Oando PSF and highlight the universal nature of microbial biodegradation processes across different fluid types.

For Dextron III ATF, the control group’s pH dropped modestly from 7.5 to 7.0, reflecting minimal chemical changes just as was observed in Oando’s and Abro’s PSF. Bacterial cultures also showed a significant reduction in pH from 7.4 to 6.5, and the fungal cultures followed a similar trend, with pH declining from 7.3 to 6.4. The mixed bacterial and fungal cultures exhibited the steepest decrease, from 7.3 to 6.0, affirming the superior degradation capabilities of mixed microbial populations.

Across all three PSFs studied, the observed pH changes reinforce the idea that microbial degradation produces organic acids as by-products, which lower the pH of the culture media.

Table 1a.

Changes in pH and Optical Density (OD) over 28 days in Oando power steering fluids under control, bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial cultures.

Table 1a.

Changes in pH and Optical Density (OD) over 28 days in Oando power steering fluids under control, bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial cultures.

| |

|

Control |

Bacteria |

Fungi |

Mixed bacteria and fungi |

| Day |

|

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

| 0 |

|

0.04 |

7.7 |

0.24 |

7.5 |

0.25 |

7.4 |

0.38 |

7.1 |

| 7 |

|

0.06 |

7.6 |

0.27 |

7.2 |

0.27 |

7.2 |

0.44 |

6.9 |

| 14 |

|

0.07 |

7.6 |

0.30 |

7.0 |

0.29 |

6.9 |

0.49 |

6.7 |

| 21 |

|

0.09 |

7.5 |

0.34 |

6.7 |

0.31 |

6.7 |

0.52 |

6.4 |

| 28 |

|

0.11 |

7.4 |

0.41 |

6.5 |

0.33 |

6.6 |

0.60 |

6.1 |

Table 1b.

Changes in pH and Optical Density (OD) over 28 days in Abro power steering fluids under control, bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial cultures.

Table 1b.

Changes in pH and Optical Density (OD) over 28 days in Abro power steering fluids under control, bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial cultures.

| |

Control |

Bacteria |

Fungi |

Mixed bacteria and fungi |

| Day |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

| 0 |

0.03 |

7.6 |

0.27 |

7.4 |

0.30 |

7.3 |

0.36 |

7.4 |

| 7 |

0.05 |

7.5 |

0.30 |

7.1 |

0.32 |

7.0 |

0.41 |

6.9 |

| 14 |

0.05 |

7.3 |

0.34 |

6.8 |

0.35 |

6.9 |

0.47 |

6.5 |

| 21 |

0.07 |

7.3 |

0.40 |

6.6 |

0.38 |

6.6 |

0.54 |

6.2 |

| 28 |

0.08 |

7.2 |

0.49 |

6.3 |

0.41 |

6.2 |

0.65 |

6.0 |

| Table 1c. Changes in pH and Optical Density (OD) over 28 days in Dexron III ATF power steering fluids under control, bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial cultures |

| |

Control |

Bacteria |

Fungi |

Mixed bacteria and fungi |

| Day |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

OD |

pH |

| 0 |

0.06 |

7.5 |

0.31 |

7.4 |

0.33 |

7.3 |

0.41 |

7.3 |

| 7 |

0.09 |

7.4 |

0.35 |

7.2 |

0.36 |

7.1 |

0.49 |

6.8 |

| 14 |

0.12 |

7.3 |

0.47 |

7.0 |

0.38 |

6.9 |

0.55 |

6.5 |

| 21 |

0.15 |

7.1 |

0.51 |

6.8 |

0.40 |

6.6 |

0.62 |

6.3 |

| 28 |

0.17 |

7.0 |

0.58 |

6.5 |

0.41 |

6.4 |

0.68 |

6.0 |

3.3.2. Changes in Optical Density (OD):

The OD data further supported these findings from the pH analysis, indicating the relationship between increase in turbidity and microbial growth in the PSF.

For Oando PSF, the control group showed a slight increase in OD from 0.04 to 0.11, indicating minimal changes in the absence of active microbial metabolism. The bacterial cultures exhibited a marked increase in OD from 0.24 to 0.41, while fungal cultures showed a rise from 0.25 to 0.33. The mixed bacterial and fungal cultures displayed the highest OD increase, from 0.38 to 0.60, highlighting the synergistic interactions that promote microbial proliferation and hydrocarbon utilization.

In Abro PSF, the control group exhibited a modest increase in OD from 0.03 to 0.08, reflecting the minimal presence of particles or microbial growth. In bacterial cultures, OD increased significantly from 0.27 to 0.49, while fungal cultures showed a rise from 0.30 to 0.41. The mixed cultures exhibited the highest OD increase, from 0.36 to 0.65, consistent with the trends observed in Oando PSF. This pattern underscores the enhanced biodegradation potential of mixed microbial populations, which leverage their combined metabolic pathways to degrade hydrocarbons more effectively.

Dextron III ATF followed a similar trajectory, with the control group showing a modest OD increase from 0.06 to 0.17. The bacterial cultures exhibited a significant rise from 0.31 to 0.58, while fungal cultures increased from 0.33 to 0.41. Mixed bacterial and fungal cultures demonstrated the highest OD increase, from 0.41 to 0.68, further reinforcing the superior biodegradation capacity of mixed cultures. These results across all three PSFs illustrate the robust microbial activity and hydrocarbon degradation potential in the presence of microbial populations, particularly in mixed cultures.

Overall, the trends in pH and OD changes highlight the critical role of microbial activity in the biodegradation of hydrocarbons in power steering fluids. The synergy between bacterial and fungal populations enhances the efficiency of these processes, as reflected in the more significant pH reductions and OD increases in mixed cultures. These findings have practical implications for understanding microbial contamination and developing strategies to mitigate the impact of microbial degradation in industrial fluids. These increases in OD reflect increased microbial activity, particularly in the mixed cultures, where both bacterial and fungal populations were actively growing and degrading the power steering fluid.

3.4. Comparison of Different Power Steering Fluids

The study found that the biodegradation rate of Abro and Oando power steering fluids was higher than that of Dexron III ATF (figure 4). This difference can be attributed to the composition of the fluids. Abro and Oando fluids, which are primarily composed of mineral oils and additives, are more conducive

to microbial growth, likely due to their nutrient content. In contrast, Dexron III ATF may contain more complex hydrocarbons, which are harder for microorganisms to degrade.

Mineral oils are widely used in industrial applications because they provide good viscosity characteristics. However, as these oils contain hydrocarbons that serve as nutrients for microbes, they can lead to biodeterioration and a decline in the quality of the fluid [

24].

Figure 4.

Comparison of degradation rates (%) of different power steering fluids (PSFs) over 28 days under bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial conditions. Mixed cultures resulted in the highest degradation, followed by bacteria alone, while fungal degradation was the lowest across all PSFs.

Figure 4.

Comparison of degradation rates (%) of different power steering fluids (PSFs) over 28 days under bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial conditions. Mixed cultures resulted in the highest degradation, followed by bacteria alone, while fungal degradation was the lowest across all PSFs.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of the role of microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi, in the biodeterioration of power steering fluids (PSFs). The results demonstrate that microbial activity significantly impacts the chemical and physical integrity of these fluids through hydrocarbon degradation. This biodegradation process involves the enzymatic breakdown of hydrocarbons, leading to the accumulation of acidic by-products and an increase in microbial populations, as evidenced by the observed changes in total viable counts, degradation rate, pH and optical density over time.

The findings are particularly significant in the context of automotive maintenance, as they highlight the vulnerability of PSFs to microbial contamination. The reduction in pH across bacterial, fungal, and mixed microbial cultures indicates a shift in the chemical environment of the fluids, which can compromise their lubricating properties and overall performance. This underscores the importance of regular fluid maintenance and the use of microbial-resistant formulations in PSFs to prevent contamination and degradation.

From a broader perspective, this study also underscores the potential of microorganisms for bioremediation of PSF-contaminated environments. The demonstrated ability of bacteria and fungi to degrade hydrocarbons suggests their application in cleaning up sites polluted with PSFs, contributing to sustainable environmental management. Mixed microbial cultures, in particular, exhibited enhanced biodegradation capabilities, likely due to synergistic interactions between bacteria and fungi. This finding suggests that mixed cultures could be optimized and harnessed in bioremediation strategies to efficiently degrade hydrocarbons in contaminated environments.

The study further highlights the need for continued research into microbial biodegradation of automotive fluids. Future studies could focus on identifying specific microbial strains or consortia with high degradation efficiency and elucidating the metabolic pathways involved in hydrocarbon breakdown. Additionally, research into the development of anti-microbial additives for PSFs could help mitigate the impact of microbial growth on fluid performance and prolong the operational lifespan of these critical automotive components. Equally important will be evaluating how existing industry-used antimicrobial agents interact with both isolated microbial species and mixed communities, to determine their practical effectiveness in reducing microbial decay. Based on our current dataset, some broad strategies may already be considered, including the incorporation of antimicrobial additives, improved monitoring of fluid quality during service, and the use of materials less prone to biofilm formation. These preliminary measures may help reduce contamination risk while more targeted, evidence-based strategies are developed through molecular-level studies.

In conclusion, while the biodegradation of PSFs presents challenges in automotive maintenance, it also offers opportunities for environmental remediation. The dual implications of microbial activity—both as a cause of fluid deterioration and as a tool for environmental cleanup—emphasize the importance of understanding and managing microbial interactions with PSFs. These findings pave the way for both improved automotive practices and innovative environmental applications.

Author Contributions

AUN: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft; PCI: methodology, supervision, validation, writing—original draft; MCO: methodology, validation, writing—review and editing. OAO: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor E.B. Essien (University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria) for help with the data visualization and interpretation. The authors also thank Karen Acurio-Cerda for help with the graphical abstract.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PSF |

Power steering fluid |

| GC-MS |

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| NaCl |

Sodium chloride |

| MgSO4

|

Magnesium sulfate |

| NaNO3

|

Sodium nitrate |

| KH2PO4

|

Potassium dihydrogen phosphate |

| NaH2PO4

|

Sodium dihydrogen phosphate |

| MSM |

Mineral salt medium |

| OD |

Optical Density |

| SOP |

Standard operating procedure |

| SRB |

Sulfate-reducing bacteria |

| NA |

Nutrient agar |

| PDA |

Potato dextrose agar |

| RPM |

Revolutions per minute |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| pH |

Potential of hydrogen |

| TVC |

Total viable count |

References

- R. Miller, “Is Power Steering Fluid Toxic ? Understanding Risks and Safety Guidelines,” Car Fluid Guide, pp. 1–22, 2024.

- C. M. Maduka and G. C. Okpokwasili, “Microbial growth in brake fluids,” Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad., vol. 114, pp. 31–38, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Yernazarova, U. Shaimerdenova, N. Akimbekov, G. Kaiyrmanova, M. Shaken, and A. Izmailova, “Exploring the use of microbial enhanced oil recovery in Kazakhstan: a review,” Front. Microbiol., vol. 15, no. August, pp. 1–12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. C. Okpokwasili and B. B. Okorie, “Biodeterioration potentials of microorganisms isolated from car engine lubricating oil,” Tribol. Int., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 215–220, Aug. 1988. [CrossRef]

- C. Maduka and G. Okpokwasili, “Biodeterioration Abilities of Microorganisms in Brake Fluids,” Br. Microbiol. Res. J., vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 276–287, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Madanhire and C. Mbohwa, Mitigating environmental impact of petroleum lubricants. 2016.

- Aa, A. Op, I. Ujj, and B. Mt, “A critical review of oil spills in the Niger Delta aquatic environment: causes, impacts, and bioremediation assessment,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 194, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Shah, K. Singhal, and V. Soni, “Comprehensive insights into the impact of oil pollution on the environment,” Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci., vol. 74, no. February, p. 103516, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Hazen, R. C. Prince, and N. Mahmoudi, “Marine Oil Biodegradation,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 2121–2129, 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. Swathi, R. Muneeswari, K. Ramani, and G. Sekaran, “Biodegradation of petroleum refining industry oil sludge by microbial-assisted biocarrier matrix: process optimization using response surface methodology,” Biodegradation, vol. 31, no. 4–6, pp. 385–405, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cao, W. Yan, M. Ding, and Y. Yuan, “Construction of microbial consortia for microbial degradation of complex compounds,” Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol., vol. 10, no. December, pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Alnuaimi, T. A. Taher, Z. Z. Aljanabi, and M. M. Adel, “High-resolution gc/ms study of biodegradation of crude oil by bacillus megaterium,” Res. Crop., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 650–657, 2020. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5864 (2023), “Standard Test Method for Determining Aerobic Aquatic Biodegradation of Lubricants or Their Components,” ASTM Int. West Conshohocken, PA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kates, “Techniques of lipidology: Isolation, analysis and identification of lipids,” Lab. Tech. Biochem. Mol. Biol., vol. 3, no. C, 1972. [CrossRef]

- C. B. Chikere, G. C. Okpokwasili, and B. O. Chikere, “Monitoring of microbial hydrocarbon remediation in the soil,” 3 Biotech, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 117–138, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Malik and S. Ahmed, “Degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons by oil field isolated bacterial consortium,” African J. Biotechnol., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 650–658, 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. K. C. Udeani, A. A. Obroh, C. N. Okwuosa, P. U. Achukwu, and N. Azubike, “Isolation of bacteria from mechanic workshops’ soil environment contaminated with used engine oil,” African J. Biotechnol., vol. 8, no. 22, pp. 6301–6303, 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. O. Okerentugba and O. U. Ezeronye, “Petroleum degrading potentials of single and mixed microbial cultures isolated from rivers and refinery effluent in Nigeria,” African J. Biotechnol., vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 312–319, 2003.

- F. Hossain, M. A. Akter, M. S. R. Sohan, D. N. Sultana, M. A. Reza, and K. M. F. Hoque, “Bioremediation potential of hydrocarbon degrading bacteria: isolation, characterization, and assessment,” Saudi J. Biol. Sci., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 211–216, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Pandolfo, A. Barra Caracciolo, and L. Rolando, “Recent Advances in Bacterial Degradation of Hydrocarbons,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Adekunle and O. Adebambo, “Petroleum Hydrocarbon Utilization by Fungi Isolated From Detarium Senegalense (J. F Gmelin) Seeds,” J. Am. Sci., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 69–76, 2007, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242158692.

- Chinonye Medline Maduka, Akuma Oji, and Gideon Chijioke Okpokwasili, “Aspergillus flavus: A degrader of commercial brake fluids,” GSC Adv. Res. Rev., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 129–135, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Fuentes, V. Méndez, P. Aguila, and M. Seeger, “Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons: Catabolic genes, microbial communities, and applications,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., vol. 98, no. 11, pp. 4781–4794, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Yemashova et al., “Biodeterioration of crude oil and oil derived products: A review,” Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 315–337, 2007. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).