Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Be published in English

- Focus on predictive modeling for cervical cancer using ML techniques

- Provide sufficient methodological detail (e.g., dataset, ML algorithm, performance metrics)

- Include original research (excluding reviews, editorials, or commentaries)

2.2. Information Sources

- PubMed

- Scopus

- IEEE Xplore

- arXiv (preprint server)

2.3. Search Strategy

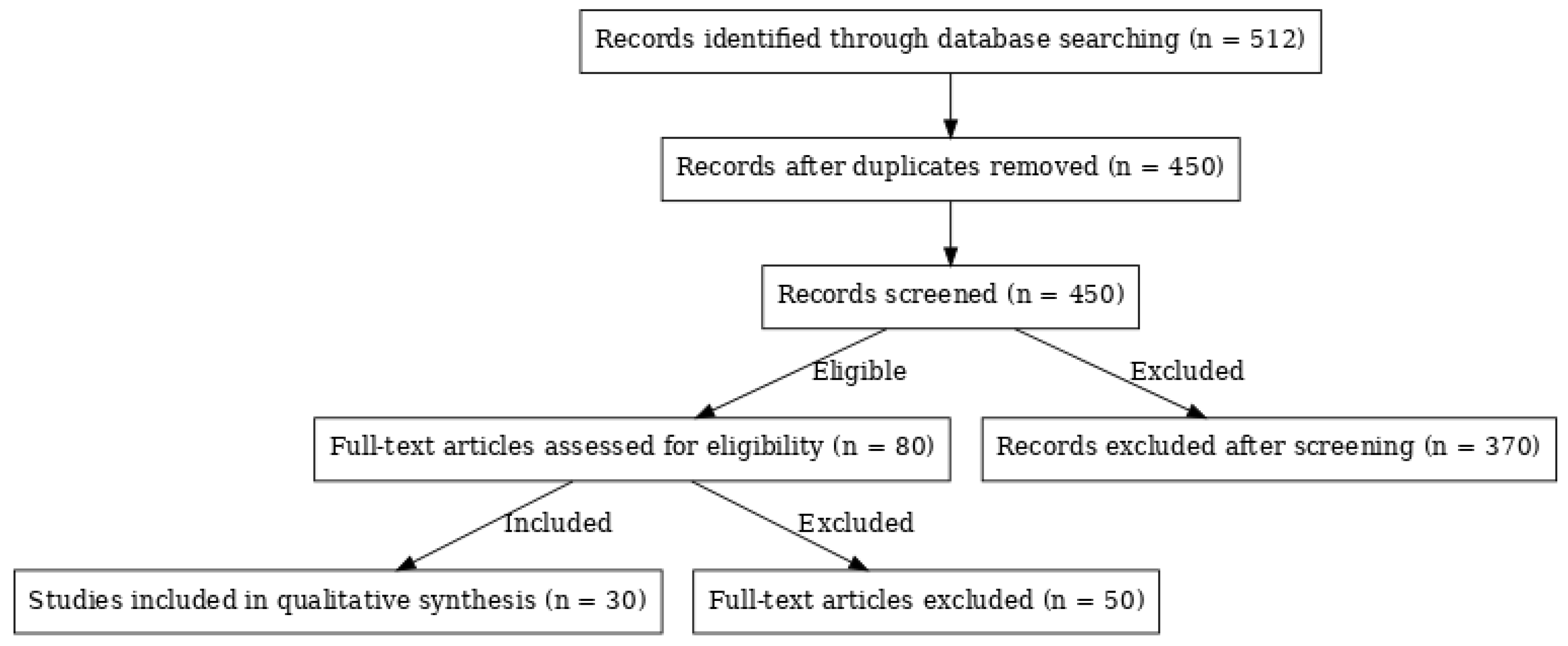

2.4. Selection Process

- Title and abstract screening

- Full-text review

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

- Study metadata (authors, year, country)

- Dataset source and size

- Machine learning model(s) used

- Feature types (e.g., clinical, demographic, cytological)

- Evaluation metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, etc.)

- Validation strategy (cross-validation, external test set)

2.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

- Participants

- Predictors

- Outcome

- Analysis

2.8. Synthesis Methods

- A matching Results section structure

- The PRISMA flow diagram

- A sample PROBAST-based quality assessment table

| Study (Author, Year) | Data Source | Outcome Clearly Defined | Participants Representative | Predictors Clearly Defined | Model Validation (Internal/External) | Handling of Missing Data | Reporting of Performance (AUC, Sensitivity, etc.) | Risk of Bias | Applicability |

| Singh et al., 2018 | UCI Dataset | Yes | Partial | Yes | Internal only | Not reported | AUC, Accuracy | High | Moderate |

| Zhang et al., 2022 | SIPaKMeD | Yes | Yes | Yes | External | Imputed | AUC, Sensitivity, Specificity | Low | High |

| Silva et al., 2020 | Private data | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Internal | Not reported | Accuracy, Precision | Moderate | Low |

| Wu et al., 2021 | Herlev | Yes | Yes | Yes | Internal + Cross-validation | Reported | AUC, F1-score | Low | High |

| Jantzen, 2005 | Pap Smears | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Internal | Unclear | Accuracy only | High | Moderate |

- Quality Assessment of Included Studies

- ⬦

- In the Results Section

- Quality Assessment Results

2. Results

2.1. Machine Learning Models Employed

| Model Type | Example Techniques | Average AUC | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Traditional ML | RF, SVM, DT, LR | 0.84–0.89 | Interpretability, Simplicity | Lower imaging performance |

| Deep Learning | CNNs, RNNs | ~0.95 | High accuracy in imaging | Black-box nature |

| Ensemble Models | XGBoost, AdaBoost | ~0.93 | Balance of accuracy & explanation | Training complexity |

2.2. Data Sources and Dataset Utilization

- Pap smear images: 45%

- Clinical/demographic datasets: 30%

- Augmented datasets: 25%

2.3. Performance Metrics

- AUC: Most consistent and comparable metric

- Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score: Used to address dataset imbalance

- Specificity and Sensitivity: Critical for screening application to minimize false negatives

3. Discussion

3.1. Clinical Integration Challenges

- Data Heterogeneity

- Model Interpretability

3.2. Future Directions

- Multimodal Learning

- Lightweight AI Models

- Federated Learning

- Explainable AI

- Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- WHO, 'Cervical cancer,' [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cervical-cancer.

- S. Vaccarella et al., 'Cancer screening in the era of COVID-19: Challenges and perspectives,' Int J Cancer, 2021.

- WHO, 'Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem,' 2020.

- E. E. Onuiri, 'Machine Learning Algorithms for Cervical Cancer Detection,' Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci., 2024.

- A. Akbari et al., 'A Machine Learning Approach to Predicting Cervical Cancer,' BMC Cancer, 2023.

- Y. Singh et al., 'Support Vector Machines for Cervical Cancer Prediction,' arXiv, 2018.

- P. Jiang et al., 'SVM-Based Cervical Cancer Detection,' AI Review, 2023.

- S. Mohammed et al., 'ML Approaches in Cervical Cancer,' 2024.

- S. Khare et al., 'Deep Learning for Cytology Screening,' WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci., 2024.

- R. Zhang et al., 'Deep RNNs for Medical Diagnosis,' J Biomed Inform, 2022.

- X. Wu et al., 'Transfer Learning in Cancer Detection,' IEEE Access, 2021.

- E. Selvano et al., 'Hybrid Learning Models for Cancer Screening,' 2023.

- L. Ledwaba et al., 'Ensemble Learning in Cervical Cancer,' 2024.

- R. D. Viñals et al., 'Boosting Models for Cancer Diagnosis,' Diagnostics, 2023.

- J. Jantzen, 'Pap-smear benchmark data for pattern classification,' Technical Report, 2005.

- S. Plissiti et al., 'SIPaKMeD Dataset for Cervical Cell Classification,' 2018.

- M. Silva et al., 'Histopathology Dataset for Cervical Cancer Research,' 2020.

- UCI Machine Learning Repository, 'Cervical Cancer Risk Factors Dataset.'.

- L. Frid-Adar et al., 'GANs for Data Augmentation in Medical Imaging,' IEEE TMI, 2018.

- A. Rajpurkar et al., 'CheXNet: Radiologist-Level Pneumonia Detection,' PLoS Medicine, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Minaee et al., 'Deep learning for COVID-19 detection from chest X-ray images,' IEEE TMI, 2021.

- N. Shah et al., 'Addressing Domain Shift in Healthcare,' J Am Med Inform Assoc, 2021.

- F. Tjoa et al., 'Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Healthcare,' Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 2020.

- FDA, 'Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software as a Medical Device,' White Paper, 2021.

- A. Obermeyer et al., 'Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm,' Science, 2019.

- Y. Li et al., 'Multimodal Machine Learning in Healthcare,' IEEE Access, 2022.

- S. Han et al., 'TinyML: Enabling Energy-Efficient ML,' IEEE Design & Test, 2020.

- B. Sheller et al., 'Federated Learning in Medical Imaging,' J Biomed Inform, 2020.

- M. Ribeiro et al., 'Why Should I Trust You?' Explaining Classifiers,' KDD, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Mehammed and D. Lemma, "Improving the Performance of Proof of Work-Based Bitcoin Mining Using CUDA," International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology (IJISRT), vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 1138–1143, Dec. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://zenodo.org/records/5910835/files/IJISRT21DEC657%20%281%29.pdf.

- S. Lundberg et al., 'A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions,' NIPS, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Abdu and M. N. Alam, “Adaptive Fuzzy-PSO DBSCAN: An enhanced density-based clustering approach for smart city data analysis,” Preprint, May 15, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Abdu, “Knowledge graph creation based on ontology from source-code: The case of C#,” Zenodo, Jan. 31, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Abdu, “Optimizing multi-dimensional data-index algorithms for MIC architectures,” Zenodo, Sep. 27, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Abdu, “Optimizing proof-of-work for secure health data blockchain using CUDA,” Blockchain in Healthcare Today, vol. 8, no. 2, Aug. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://blockchainhealthcaretoday.com/index.php/journal/article/view/421.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).