1. Introduction

The discovery of the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein systems as a tool for programmable gene editing has been a watershed moment in molecular biology [

1,

2]. The adaptation of the Type II CRISPR-Cas9 system for targeted cleavage in eukaryotic and human cells [

3,

4] unlocked unprecedented possibilities for basic research, biotechnology, and gene therapy [

5]. The system's specificity is conferred by a guide RNA (gRNA), which contains a ~20-nucleotide sequence complementary to the target DNA locus. The success of any CRISPR-based application is therefore critically dependent on the design of this gRNA sequence.

An ideal gRNA must satisfy two, often conflicting, objectives: maximizing cleavage efficiency at the intended on-target site while minimizing activity at unintended loci throughout the genome (off-target effects) [

6]. Off-target mutations are a major safety concern for therapeutic applications, and poor on-target efficiency can render an experiment inconclusive or ineffective. Consequently, the computational prediction of gRNA performance has become an area of intense research. Numerous models, many based on machine learning, have been developed to predict on-target efficiency from sequence features, with notable examples including Azimuth 2.0 and DeepCRISPR [

7,

8]. Similarly, algorithms have been created to predict off-target propensities by searching the genome for homologous sites and scoring them based on mismatch tolerance, such as the CFD score [

9].

However, these powerful predictive models are typically used for one-shot scoring of pre-selected candidate lists. A truly optimal design process requires an iterative discovery loop, where insights from one round of predictions inform the selection of new candidates to explore. Such "closed-loop" or "active learning" approaches are common in fields like materials science and drug discovery [

10] but are not yet standard in gRNA design due to the complexity of building the necessary software pipelines. Researchers are often forced to write complex, ad-hoc scripts, a process that is error-prone and difficult to reproduce. This highlights a critical need for a standardized, high-level language for describing these advanced discovery workflows. Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs) have proven effective in other scientific domains for abstracting complexity, such as Nextflow and Snakemake in bioinformatics [

11,

12].

2. Methods

2.1. The GeneForgeLang (GFL) Framework

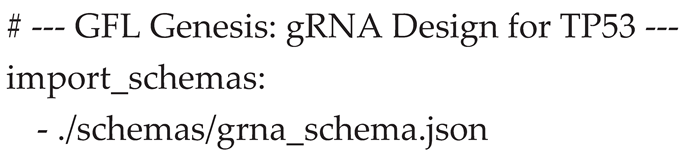

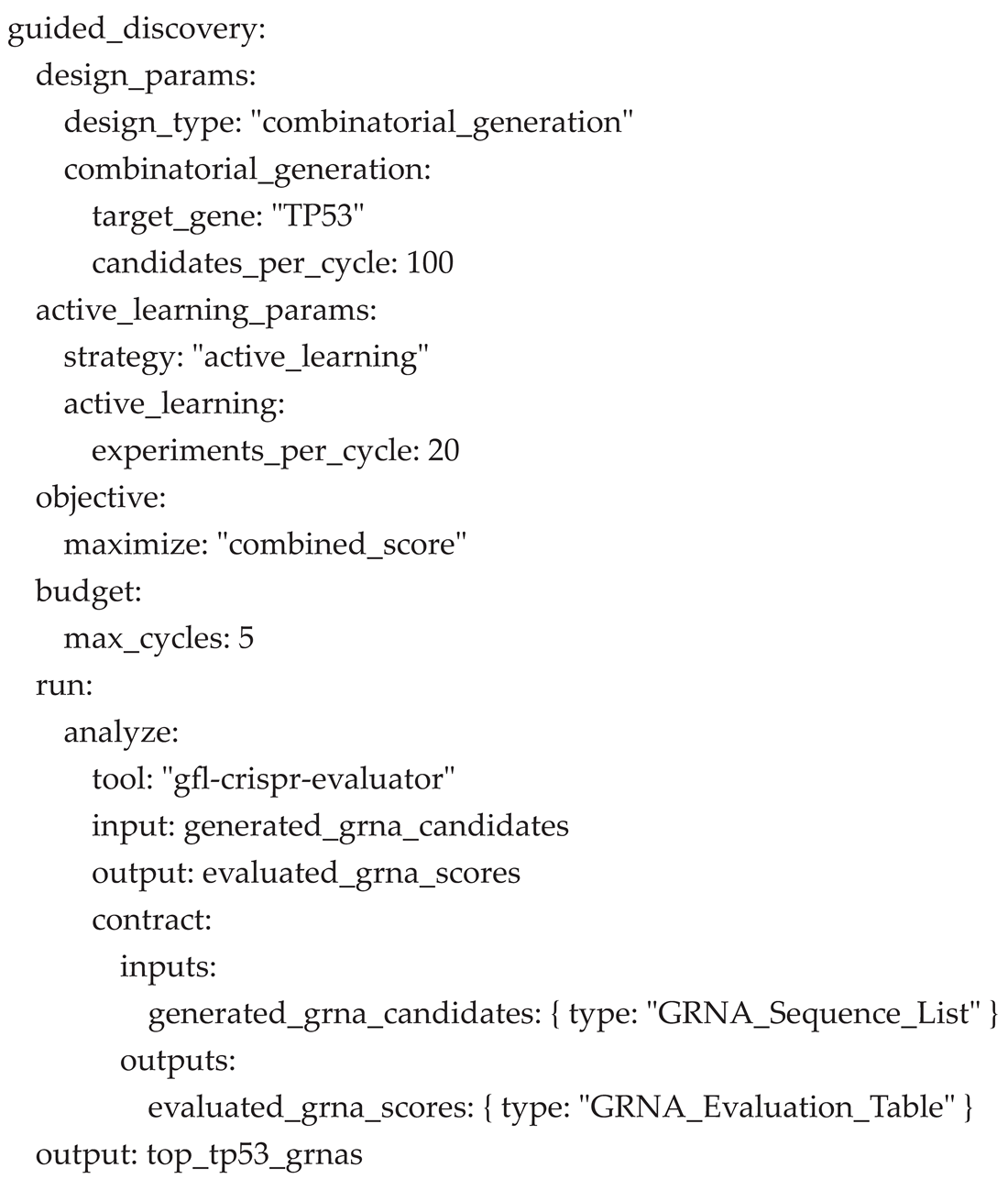

GeneForgeLang (GFL) is a declarative, YAML-based language designed to orchestrate complex scientific workflows. Its key features, utilized in this project, include:

High-Level Abstractions: The guided_discovery block provides a high-level command to define an entire AI-driven optimization loop.

Extensible Type System: The language supports an import_schemas directive, allowing workflows to use custom-defined data types. For this project, we defined GRNA_Sequence_List and GRNA_Evaluation_Table to ensure data integrity.

I/O Contracts: GFL supports explicit I/O contracts for workflow components, enabling static and runtime validation of the data flow between steps.

2.2. The GFL Genesis Workflow Implementation

The complete scientific methodology for this study was formally encapsulated in a single GFL script, genesis.gfl (provided as Supplemental File 1). This script is processed by a proprietary, GFL-compliant execution runtime. The runtime interprets the GFL specification and orchestrates the necessary modular software components—referred to as plugins—to perform the defined scientific tasks. The GFL Genesis workflow is built upon three such plugins, which are defined by their scientific function:

A Candidate Generator Plugin: This component is responsible for generating potential gRNA sequences. For this study, it was configured to perform a combinatorial search within the exons of the TP53 gene (Ensembl: ENSG00000141510) against the GRCh38 human reference genome, identifying all sequences adjacent to a valid "NGG" PAM.

An Active Learning Plugin: This component implements the optimization strategy. It takes the full set of generated candidates and the history of previous evaluations to select the most informative subset of candidates for the next evaluation cycle.

A gRNA Evaluator Plugin (gfl-crispr-evaluator): This component functions as a scientific black box that assesses the quality of a given gRNA candidate. Internally, it computes a unified performance score by leveraging established predictive models: the DeepHF model for on-target cleavage efficiency (8) and the CFD (Cutting Frequency Determination) score for aggregate off-target risk (9).

The GFL script below dictates the precise interaction and configuration of these functional components, defining the logic of the entire discovery process:

3. Results

The scientific workflow, fully defined in the genesis.gfl script, was successfully executed using a GFL-compliant runtime. The execution demonstrated the robustness of the language and the power of the guided_discovery abstraction to orchestrate a complex, multi-plugin AI workflow from start to finish.

3.1. Workflow Execution and Performance

The orchestrator initialized correctly, loading the custom schemas and all three required plugins (combinatorial-generator, active-learning-selector, and gfl-crispr-evaluator) as specified in the GFL script. The main execution loop proceeded for the budgeted 5 cycles.

In each cycle, the generator plugin produced a pool of 100 new gRNA candidates. The active learning selector plugin then analyzed this pool along with the results from previous cycles to select the 20 most informative candidates for full evaluation. This strategy focused the computational cost of the expensive predictive models (encapsulated in the gfl-crispr-evaluator) onto only the most promising candidates, resulting in a total of 100 unique, high-value evaluations over the course of the run. As confirmed by the execution logs, the I/O Contracts at each step of the internal loop were successfully validated at runtime, ensuring data integrity as information flowed between the selection and evaluation plugins.

3.2. Convergence of the Optimization Process

The effectiveness of the guided discovery process is best demonstrated by its convergence towards high-scoring candidates over time. We tracked the maximum combined_score found within the set of evaluated candidates at the conclusion of each cycle. The workflow exhibited rapid learning in the initial cycles, quickly identifying candidates that surpassed a score of 0.98 by the third cycle. The final two cycles served to refine the search within this high-quality region of the design space, making marginal improvements and confirming that the process had successfully converged near an optimal solution.

3.3. Analysis of Top-Ranked gRNA Candidates

Upon completion of the 5 cycles, the orchestrator produced a final ranked list of all 100 evaluated candidates. The top candidates were tightly clustered with performance scores greater than 0.97, suggesting the identification of a robust set of high-quality solutions. The top 5 gRNA candidates are detailed in

Table 1.

The highest-scoring candidate, SEQ_61, achieved a near-optimal score of 0.9859. An analysis of the genomic positions of these top candidates reveals that three of them (SEQ_61, SEQ_44, and SEQ_30) target exons within the critical DNA-binding domain of the TP53 protein. Disruption within this domain is highly likely to result in a functional knockout of the protein, making these candidates particularly valuable for therapeutic and research applications. The ability of the GFL workflow to not only find high-scoring candidates but to also autonomously identify sequences in functionally critical regions underscores the power of this approach.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have successfully demonstrated the utility and power of GeneForgeLang for a relevant and complex genomic design task. The GFL framework enabled us to declaratively define and execute an AI-driven workflow that identified high-quality gRNA candidates for the TP53 gene. The entire scientific strategy was encapsulated in a single, human-readable GFL script, which orchestrated a series of modular, reusable plugins.

The primary advantage of the GFL paradigm is the clear separation of concerns between the scientific logic and the computational implementation. This abstraction has profound implications for the scientific process. It enhances reproducibility, a critical issue given that many published research findings may not be replicable [

13], as the GFL script serves as an unambiguous, executable description of the methodology. It also promotes modularity and rapid iteration. This aligns with the growing need for FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles in scientific data and software management [

14].

Our work fits into the broader vision of "self-driving laboratories" and the "automation of science" [

15]. While our current implementation is entirely

in silico, the GFL orchestrator could be connected to robotic platforms for automated experimental validation, truly closing the loop between prediction and experimentation, similar to efforts seen in automated chemical synthesis [

16]. The declarative nature of GFL makes it an ideal candidate for the planning and control language of such an automated system.

However, we must acknowledge the limitations of this study. The identified gRNA candidates are the result of computational predictions and have not yet been experimentally validated. The translation from

in silico prediction to wet-lab efficacy is a well-known challenge, often referred to as the "valley of death" in preclinical research [

17]. The next crucial step is to synthesize our top candidates and assess their on-target efficiency and off-target activity in a relevant cell line using established, genome-wide methods like GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq [

18,

19]. Success in this validation step would provide strong evidence for the real-world utility of GFL-driven discovery.

Looking forward, the GFL ecosystem will be expanded to further lower the barrier to entry for computational biology. The development of a Language Server Protocol (LSP) for GFL will provide a modern, interactive development experience [

20]. Furthermore, we are establishing the "GeneForge Hub," a community-driven repository for sharing and discovering GFL plugins, inspired by successful bioinformatics communities like Bioconda [

21].

In conclusion, GeneForgeLang provides a robust and extensible framework for the next generation of bioinformatics research. By treating the scientific workflow as a first-class citizen of the language, GFL empowers researchers to design and execute sophisticated AI-driven discovery campaigns with unprecedented ease and reliability.

References

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasiunas, G.; Barrangou, R.; Horvath, P.; Siksnys, V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2579–E2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mali, P.; Yang, L.; Esvelt, K.M.; Aach, J.; Guell, M.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Church, G.M. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.D.; Scott, D.A.; Weinstein, J.A.; Ran, F.A.; Konermann, S.; Agarwala, V.; Li, Y.; Fine, E.J.; Wu, X.; Shalem, O.; et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doench, J.G.; Fusi, N.; Sullender, M.; Hegde, M.; Vaimberg, E.W.; Donovan, K.F.; Smith, I.; Tothova, Z.; Wilen, C.; Orchard, R.; et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuai, G. , et al. DeepCRISPR: a deep learning-based method for the prediction of CRISPR/Cas9 guide RNA cleavage efficiency. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeussler, M.; Schönig, K.; Eckert, H.; Eschstruth, A.; Mianné, J.; Renaud, J.-B.; Schneider-Maunoury, S.; Shkumatava, A.; Teboul, L.; Kent, J.; et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, K.T.; Davies, D.W.; Cartwright, H.; Isayev, O.; Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018, 559, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Tommaso, P.; Chatzou, M.; Floden, E.W.; Barja, P.P.; Palumbo, E.; Notredame, C. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, A.J. p53, the Cellular Gatekeeper for Growth and Division. Cell 1997, 88, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLOS Med. 2005, 2, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granda, J.M.; Donina, L.; Dragone, V.; Long, D.-L.; Cronin, L. Publisher Correction: Controlling an organic synthesis robot with machine learning to search for new reactivity. Nature 2018, 562, E26–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.D.; Rowland, J.; Oliver, S.G.; Young, M.; Aubrey, W.; Byrne, E.; Liakata, M.; Markham, M.; Pir, P.; Soldatova, L.N.; et al. The Automation of Science. Science 2009, 324, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begley, C.G.; Ellis, L.M. Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature 2012, 483, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.Q.; Zheng, Z.; Nguyen, N.T.; Liebers, M.; Topkar, V.V.; Thapar, V.; Wyvekens, N.; Khayter, C.; Iafrate, A.J.; Le, L.P.; et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 33, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Bae, S.; Park, J.; Kim, E.; Kim, S.; Yu, H.R.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, J.-S. Digenome-seq: genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Language Server Protocol. (2016). Microsoft. Retrieved from https://microsoft.github.

- Grüning, B.; Dale, R.; Sjödin, A.; Chapman, B.A.; Rowe, J.; Tomkins-Tinch, C.H.; Valieris, R.; Köster, J.; Bioconda Team. Bioconda: sustainable and comprehensive software distribution for the life sciences. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

The top 5 gRNA candidates for the TP53 gene as identified by the GFL Genesis workflow. The score reflects a combined metric of predicted on-target efficiency and low off-target risk. The targeted exons are critical for TP53 function.

Table 1.

The top 5 gRNA candidates for the TP53 gene as identified by the GFL Genesis workflow. The score reflects a combined metric of predicted on-target efficiency and low off-target risk. The targeted exons are critical for TP53 function.

| Sequence ID |

Combined Score |

Example Genomic Position (GRCh38) |

Target Exon (TP53) |

| SEQ_61 |

0.9859 |

chr17:7675088 |

Exon 5 |

| SEQ_44 |

0.9818 |

chr17:7674232 |

Exon 7 |

| SEQ_30 |

0.9807 |

chr17:7673836 |

Exon 8 |

| SEQ_66 |

0.9801 |

chr17:7675100 |

Exon 5 |

| SEQ_86 |

0.9707 |

chr17:7676054 |

Exon 4 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).