I. Introduction

Contemporary telehealth platforms increasingly adopt multi-tenant architectures, where a single system serves multiple independent organizations over shared infrastructure. While this design improves efficiency, it also creates significant compliance challenges. Each tenant must meet distinct legal requirements, such as GDPR in Europe or HIPAA in the United States, and regulators demand clear evidence of tenant-level isolation, access control, and auditable decision records. Existing approaches, such as container-based isolation or static access control, lack semantic interpretability and cannot adapt to evolving legal norms [

1].

In high-stakes AI-assisted healthcare, compliance complexity is amplified by ambiguous inputs and stakeholder-specific interpretations. The same output, such as “high risk,” may be viewed by clinicians as a clinical threshold, by administrators as a system alert, and by regulators as a legal liability [

2]. Without a formal mathematical foundation, it is difficult to guarantee that compliance logic will behave consistently across such interpretive variations, evolving regulations, and jurisdictions, or to prove properties.

This research addresses that gap by establishing a mathematically grounded compliance reasoning framework that is provably consistent, adaptable across jurisdictions, and transparent in its decision-making logic. Such a framework enables healthcare providers to demonstrate regulatory adherence with formal proofs, supports regulators with verifiable audit trails, and offers a reusable decision model that can be extended to other high-stakes, compliance-intensive domains. To this end, this paper proposes a decision-theoretic semantic compliance framework that encodes legal obligations in OWL ontologies and SWRL rules, and derives compliance judgments through a mathematically grounded chain that spans prior probabilities, Bayesian updating, likelihood ratio testing, and log-likelihood ratio decomposition before instantiating them in the system architecture, as part of a broader doctoral research program on semantic compliance for AI systems in multi-tenant healthcare environments.

In simpler terms, the decision model first estimates the baseline risk for each tenant–jurisdiction pair, then adjusts it using case-specific evidence, applies a statistical decision rule, and finally breaks down the evidence into contributions from each legal rule.

Prior work [

3] introduced a modular AI framework for telehealth systems that treated compliance as an embedded, explainable process rather than an external checklist. The architecture combined structured legal rules with a fuzzy inference engine and a compliance reasoner to support legality checks in settings with ambiguity or semantic uncertainty. It could assign partial truth values, such as interpreting “I am almost 18” as both “minor” and “adult,” and prompt for clarification instead of applying rigid thresholds. While this approach addressed some interpretive ambiguity through role-aware explanations and contextual guidance, it was developed for single-tenant contexts and did not provide a formal mathematical basis for reasoning.Outside of this line of work, many compliance solutions for multi-tenant systems still rely on static rules or basic role-based access control (RBAC). These methods can handle simple authorizations but lack semantic understanding of higher-level legal concepts and do not scale well in heterogeneous environments. They also struggle to determine whether decisions meet abstract obligations such as “fair processing” or “data minimization,” which are context dependent and hard to encode directly. Moreover, they adapt poorly when regulations change, often requiring manual recoding.

Even with advances in modular and role-aware architectures, most systems still lack a formal mathematical foundation. Without it, there is no principled way to ensure that compliance logic remains consistent as laws evolve or interpretations differ, nor to verify provable properties. This motivates the integration of a decision-theoretic and probabilistic reasoning model that can derive compliance judgments formally and map them to operational rules in the system.

II. Methodology

A. Theoretical Framework

To ensure that compliance reasoning in a multi-tenant telehealth platform is both verifiable and generalizable, the framework formalize the decision process as a probabilistic hypothesis-testing problem. This formalization establishes a clear mapping from legal and regulatory requirements to a sequence of mathematical constructs, enabling transparent reasoning and rigorous validation. In particular, the framework connects four classic components—prior violation probability, Bayesian evidence updating, Neyman–Pearson optimal decision rule, and log-likelihood ratio decomposition—to the operational semantics of the rule-based compliance engine.

1). Prior Violation Probability via the Law of Total Probability

Let’s begin with the prior violation probability, which captures the heterogeneity of tenants and jurisdictions in the platform. Let T denote the set of tenants, J the set of jurisdictions, and the compliance state, where C denotes “compliant” and V denotes “violation.” Assuming that the collection of events forms a finite partition of the sample space, the overall probability of violation before observing any evidence follows from the law of total probability:

(1)

This expression aggregates the contribution of each tenant–jurisdiction combination to the global violation risk. For a given tenant t in jurisdiction j, the term measures the likelihood of violation if the action originates from that specific context. The weights and represent the probability that an action is initiated by tenant t and that tenant t operates under jurisdiction j. This decomposition not only aligns with the modular policy architecture of the system, where each jurisdiction’s rules are maintained independently, but also serves as the prior in the Bayesian updating step, where case-specific evidence will adjust the probability estimate for the current decision.

Equation (1) can be understood as setting the “starting line” for the compliance decision. It represents the likelihood of a violation before any evidence is observed, specific to each tenant–jurisdiction pair. A tenant with a strong compliance history would have a low starting-line probability, while one with prior violations would start higher. This prior value is derived from historical statistics or regulatory assessments, providing a baseline against which later evidence will be compared.

2). Posterior Violation Probability via Bayes’ Theorem

Once evidence E is obtained from the semantic reasoning layer, such as whether consent has been obtained, whether data are encrypted, and which jurisdiction’s rules apply, the prior probability in Eq. (1) can be updated to a posterior probability via Bayes’ theorem:

(2)

Here and denote the likelihoods of observing E under the violation and compliance states, respectively. This update adjusts the global prior to reflect case-specific conditions provided by the semantic reasoning layer. In practice, for the two representative scenarios, “no consent + no encryption” yields a high while “consent + encryption” yields a high .

3). Neyman–Pearson Likelihood Ratio Test for Compliance Decision

The posterior probability naturally leads to a decision problem: when should the system classify an action as a violation? Under the Neyman–Pearson lemma, the most powerful test between two simple hypotheses compares the likelihood ratio to a threshold:

(3)

4). Log-Likelihood Ratio Decomposition for Rule-Based Evidence

In the architecture, the evidence E is represented by a set of binary rule triggers indicating whether each active SWRL rule in the jurisdiction-specific set fires for the current action. To instantiate the likelihood ratio in this discrete feature space, we apply the log-likelihood ratio decomposition from statistical pattern recognition. Under the standard assumption of conditional independence of rule triggers given Y, the log-likelihood ratio can be written as:

(4)

This form expresses the overall strength of evidence as the sum of per-rule contributions, with positive terms indicating rules more likely under violation and negative terms indicating rules more likely under compliance. is the set of relevant features for case j, is the binary observation of feature r where (1=present, 0=absent), and denote the conditional probabilities under violation and compliance states. This analysis assumes conditional independence of rule triggers given the compliance state Y which allows (4) to be expressed as a sum of per-rule contributions. This assumption is reasonable in the multi-tenant architecture because each jurisdiction’s rules are loaded as a separate module, reducing cross-policy correlations. If high correlation is detected within a module, pairwise correction terms can be added to (4) without altering the overall decision structure. This design ensures that the decomposition remains both mathematically valid and operationally practical.

The mathematical formulation defines the compliance reasoning process in probabilistic terms, using rule triggers and likelihood ratios to determine whether an action violates tenant-specific obligations. In the system implementation, these variables and computations are embedded within the semantic compliance architecture. The ontology layer encodes the rules

and legal constraints, the runtime policy engine evaluates the likelihood ratio

and posterior probabilities in real time, and the responsibility-chain model records the accountable entities associated with each event.

Table 1 summarizes how each equation in the theoretical framework maps to specific implementation elements in the semantic compliance architecture and to the experimental scenarios used for validation. This mapping links the mathematical constructs to their operational realization and empirical evaluation.

5). Minimal Numerical Example

For clarity, consider a simple hypothetical calculation. Suppose two rules—R1 = “missing patient consent” and R2 = “data not encrypted”—have trigger probabilities of 0.9 and 0.8 in violation cases, and 0.1 and 0.2 in compliant cases. If both rules are triggered for a given event, (4) yields a log-likelihood ratio of

If the decision threshold α is set to 1.5, the accumulated evidence exceeds the threshold, leading to a violation classification and immediate responsibility-chain recording. These probabilities are hypothetical and provided solely for demonstration

C. Explainable AI for Role-Specific Compliance

In addition to formal compliance enforcement, the architecture incorporates a stakeholder-aware interpretability mechanism designed to address semantic mismatches in how AI outputs are understood. In real-world healthcare, the same result, such as a “high risk” label, may be interpreted as a numerical threshold by a developer, an urgent hospitalization warning by a patient, or a liability signal by a legal reviewer. These interpretive gaps can lead to misunderstanding, misaligned accountability, or legal risk. To mitigate this, the framework embeds role-specific expectations into the reasoning process, enabling it to detect potential semantic divergence and adjust explanations accordingly.

This design builds on prior use of fuzzy reasoning, where ambiguous inputs such as a stated age of 17.5 were assigned partial values (for example, 0.5 in both “minor” and “adult” categories) to reflect legal uncertainty. These intermediate scores triggered cautious prompts rather than binary decisions. While the current framework replaces fuzzy logic with predefined semantic categories, it retains the same interpretive principle. Inputs are now routed through explanation paths that are customized based on the user’s role, such as clinician, patient, or platform administrator. For example, a borderline consent case may activate different justification paths depending on whether the actor is a clinician, a patient, or a platform module. This ensures that AI decisions are not only legally valid, but also semantically aligned with the expectations of each stakeholder.

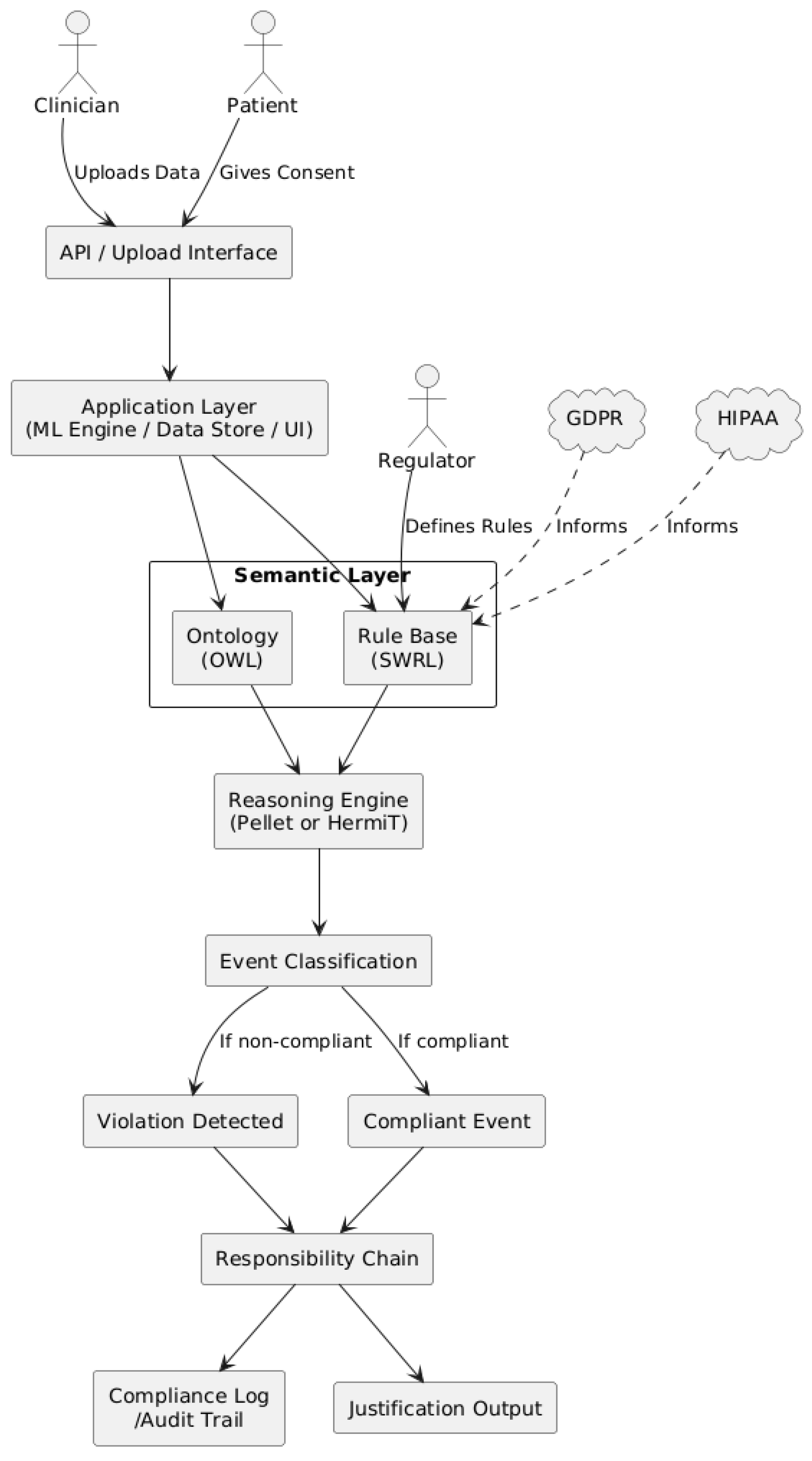

D. Legal and Application Layers

The legal layer serves as the source of normative obligations. It encompasses unstructured documents, such as national regulations, sector-specific laws, ethical guidelines, and contractual terms that may apply to one or more tenants. These may include globally recognized frameworks such as the GDPR in the EU, the HIPAA in the U.S., or internal organizational policy manuals. Information within this layer is typically expressed in natural language and interpreted by legal professionals. It defines high-level obligations (e.g., “data must be processed lawfully and fairly”) and prohibitions (e.g., “do not disclose without consent”); however, it lacks the precision and structure required for computational reasoning.

The other end of the spectrum is the application layer, which reflects the technical architecture and behavior of the AI architecture. These include components such as data sources and repositories, APIs, AI models and their input/output operations, user authentication and authorization controls, and audit logging mechanisms. Every user or tenant interaction occurs within this layer, including operations such as uploading datasets, executing predictive models, or retrieving results. These events are typically recorded in logs and are subject to access-control mechanisms. However, in the absence of a semantic link to higher-level rules, the architecture alone cannot determine whether these events meet the compliance requirements [

7].

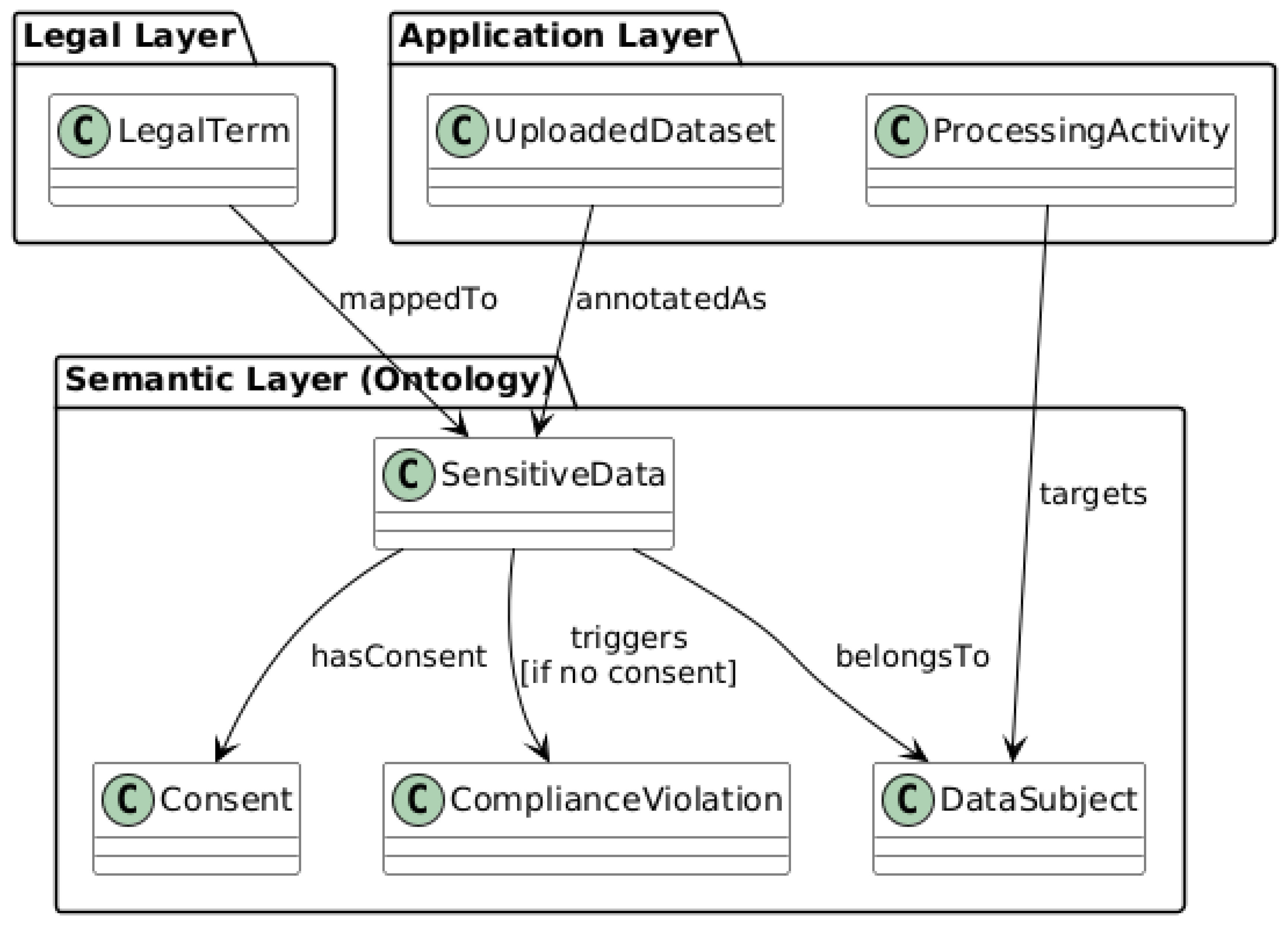

F. Semantic Mapping and Rule-Based Compliance Reasoning

The interaction among the three layers is facilitated via semantic mapping, which aligns legal terms with corresponding concepts in the ontology.

This mapping establishes a controlled vocabulary that standardizes interpretation across the regulatory and technical domains. For instance, the legal term “personal data” is linked to the ontology class PersonalData, which may carry properties such as hasOwner, hasPurpose, or hasConsent. Similarly, elements within the Application Layer, such as API calls or uploaded files, were annotated using the same ontological terms. A dataset received through an API can be classified as an instance of SensitiveData if it satisfies predefined schema patterns (e.g., inclusion of health records, identifiers, or geolocation).

Bidirectional mapping supports both top-down and bottom-up reasoning. From top down, the framework can derive operational obligations from high-level legal norms, for instance, by inferring that an API transaction must satisfy encryption or consent requirements based on the class of data involved. From the bottom up, the framework can evaluate an observed event, such as a dataset upload, and determine the regulatory consequences triggered by that action employing semantic annotations and mapped inference rules. This two-way reasoning mechanism is essential for proactive enforcement and retrospective auditability in complex, multi-tenant environments.

G. Obligation Embedding and Responsibility Chain Modeling

A key mechanism of this model is obligation embedding, which refers to pre-defining legal requirements within the semantic rule structure as conditional triggers linked to user actions or system events. Each legal requirement is statically represented and embedded within the semantic rule structure as a condition linked to the operations. For example, the obligation “user consent must be verified before data use” is encoded as a semantic rule that links the class DataSubject and property hasConsent to a required action (e.g., invoking the consent verification API before inference). These obligations become active in response to relevant events, enabling dynamic activation within the application layer.

To enable accountability and traceability, the semantic layer includes a responsibility chain model. This model assigns actors (tenants, platform operators, and regulators) to the obligations encoded in the rules. For example, if a tenant uploads unencrypted sensitive data, and the rule “sensitive data must be encrypted” is violated, the framework can infer that the tenant was responsible for the failed obligation. This attribution is logged into the Compliance Log, enabling downstream analysis, notification, or regulatory reporting. Because all rules and annotations are stored in a formal ontology, these responsibility chains are machine-readable and verifiable.

Another important feature is the integration of application-layer data, which flows with semantic rule checks. Every time an operation occurs, such as invoking a machine learning model with a particular dataset, the involved data objects are annotated with ontology classes, and the architecture evaluates the applicable obligations using the rule engine. The rule engine determines whether all the preconditions for a lawful operation are satisfied. Otherwise, the framework blocks the action, raises a flag, or logs a violation, depending on the enforcement policy.

The result is a compliance framework that can perform continuous automated reasoning over live system behavior using legally grounded obligations expressed in formal, semantically rich language. This approach enables enforcing complex policies that depend on user roles or resource types and contextual factors such as data categories, consent states, and jurisdiction. By embedding legal meaning into the semantic layer of the framework and connecting it to latency-sensitive runtime behavior, the platform achieves a level of compliance monitoring that is both dynamic and legally explainable.

In the experimental validation, one scenario involved a clinic uploading patient data without obtaining consent or applying encryption. The framework detected that both the hasConsent and isEncrypted conditions were missing, which triggered a violation rule in the SWRL rule base. The reasoning engine classified the event as non-compliant, and the responsibility-chain model assigned accountability to the uploading clinic while confirming that the platform had enforced the correct policy. In a contrasting scenario, another clinic accessed patient data only after valid consent had been obtained and proper encryption applied. The reasoning engine identified the conditions as compliant and marked the event accordingly. In this case, the responsibility-chain recorded that the obligations had been met, attributing correct behavior to both the clinic and the platform. These examples illustrate how the framework supports both violation detection and confirmation of lawful actions.

The SWRL rules defined in this section correspond directly to the variables and evidence terms in the probabilistic formulation. Tenant and jurisdiction identifiers in rules such as Region(EU) or Region(US) map to the prior probability components in (1), where and define the initial compliance profile. Conditions such as hasConsent and isEncrypted form the elements of the evidence vector E in (2). When a rule’s antecedent is satisfied, it signals that the corresponding evidence component has been observed, and the Bayesian update adjusts the prior to a posterior violation probability .

At runtime, the set of triggered SWRL rules acts as the binary indicators in (4). For example, the rule (6) is equivalent to when the action and data meet its conditions. The likelihood ratio test in (3) aggregates these triggers, comparing the computed against the decision threshold to classify the action as compliant or non-compliant. The log-likelihood ratio decomposition in (4) then expresses the cumulative evidential weight of the active rules, where each rule’s contribution reflects its discriminative power between compliant and violation cases.

This mapping ensures that each semantic rule has a precise role in the mathematical decision process, linking the legal logic to its probabilistic execution. In practice, it allows the framework to maintain a one-to-one correspondence between the legal constructs embedded in the ontology and the quantitative reasoning steps that drive compliance judgments.

H. Role-Based Responsibility and Reasoning Paths

To enable machine-readable policy enforcement and automated compliance reasoning, the design adopted SWRL as the core representation language for modeling obligations, omissions, and violations. SWRL allows us to define if-then rules over OWL ontologies using logic-based structures, enabling the inference engine to detect patterns such as unmet obligations or failed policy enforcement.

Each SWRL rule in the architecture takes the form use (5):

Antecedent (Body) → Consequent (Head) (5)

In the framework, it directly encode compliance obligations using SWRL rules to ensure machine-executable reasoning for different roles. Each actor, Tenant, Platform, and Regulator was associated with a distinct set of rule-based responsibilities [

8] based on the context, action, and entity relationships. For example, the obligation of a tenant to encrypt sensitive data before uploading can be expressed as follows (6):

uploadsSensitive(?a,?d) → EncryptBeforeUpload(?a,?d) (6)

where the antecedent defines the triggering condition (e.g., user role, data type, or action) and the consequent specifies the inferred result (e.g., obligation created, violation recorded, and responsibility assigned).

SWRL rules can be evaluated at runtime by an OWL reasoner embedded within the compliance monitoring component, forming the basis for latency-sensitive runtime decision-making and accountability tracking across multiple tenants and jurisdictions.

Regulatory obligations may vary significantly in multi-tenant AI platforms depending on their jurisdiction. Different countries have enforced different data protection laws. For instance, the GDPR in the European Union emphasizes the rights of data subjects, such as the right to erasure. Contrarily, the HIPAA in the United States requires strict access control and audit logging. Owing to these legal differences, the platform must support jurisdictional flexibility.

Each compliance rule in the framework is annotated using a region-specific label to address this requirement. This allows the semantic reasoner to activate rules that correspond to the regulatory environment of the tenant. For example, in the European context, a platform is required to erase personal data upon request as follows (7):

Region(EU)^Data(?x)^RequestErase(?x) → Obligation(Platform,EraseData(?x)) (7)

Similarly, in the United States, HIPAA requires audit logs for all access events as follows (8):

Region(US) ^ CoveredEntity(?e) ^ Access(?a) → Obligation(?e,RecordLog(?a)) (8)

These SWRL rules are stored within a unified rule base. However, at runtime, only the applicable subset is loaded based on the tenant’s jurisdiction. This mechanism avoids the need to maintain multiple isolated rule architecture.

The platform determines the tenant’s jurisdiction using three data sources: the registration profile in which the tenant declares its country, the IP address of the API request, and user-selected preferences regarding compliance. If a tenant expands their services across regions, the framework detects changes and dynamically replaces the rule set. In such cases, the platform clears the cached obligations and reloads the relevant policies from the correct jurisdictional container.

This runtime switching process ensures that tenants remain compliant even as their geographical scope changes. Moreover, it supports multiregional deployment by maintaining alignment with local regulatory expectations.

III. Semantic Explainability and Experimental Validation

In this study, the experiments are intended as feasibility checks of the proposed decision-theoretic framework and modular rule-loading approach within a multi-tenant setting, rather than as a benchmark comparison. Specifically, this study aim to assess (i) whether the log-likelihood ratio (LLR)-based decision operates correctly under a fixed Type-I error rate α, (ii) whether the contributions of individual rules can be clearly interpreted, and (iii) whether the system maintains smooth scalability as the number of rules increases.

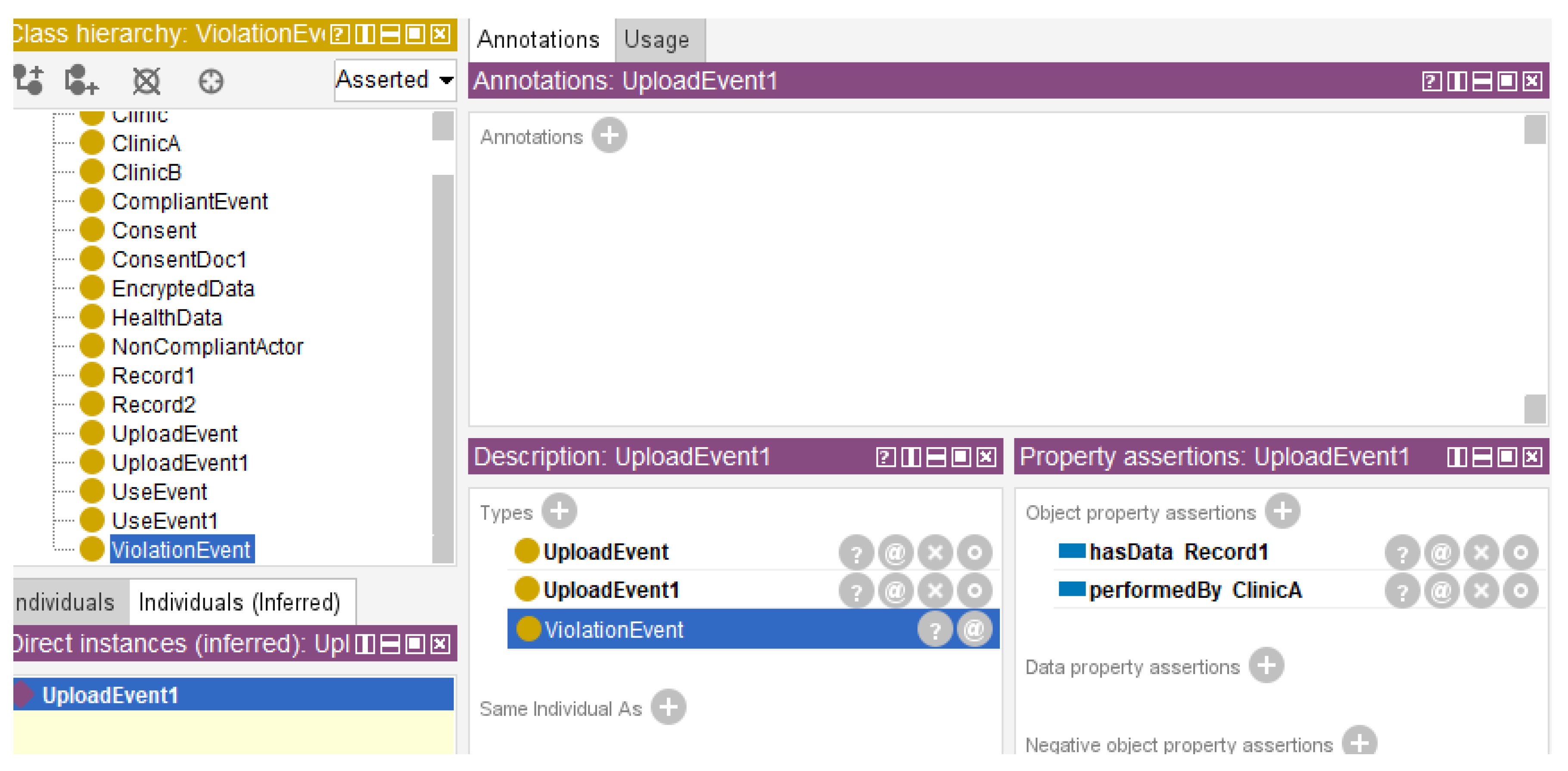

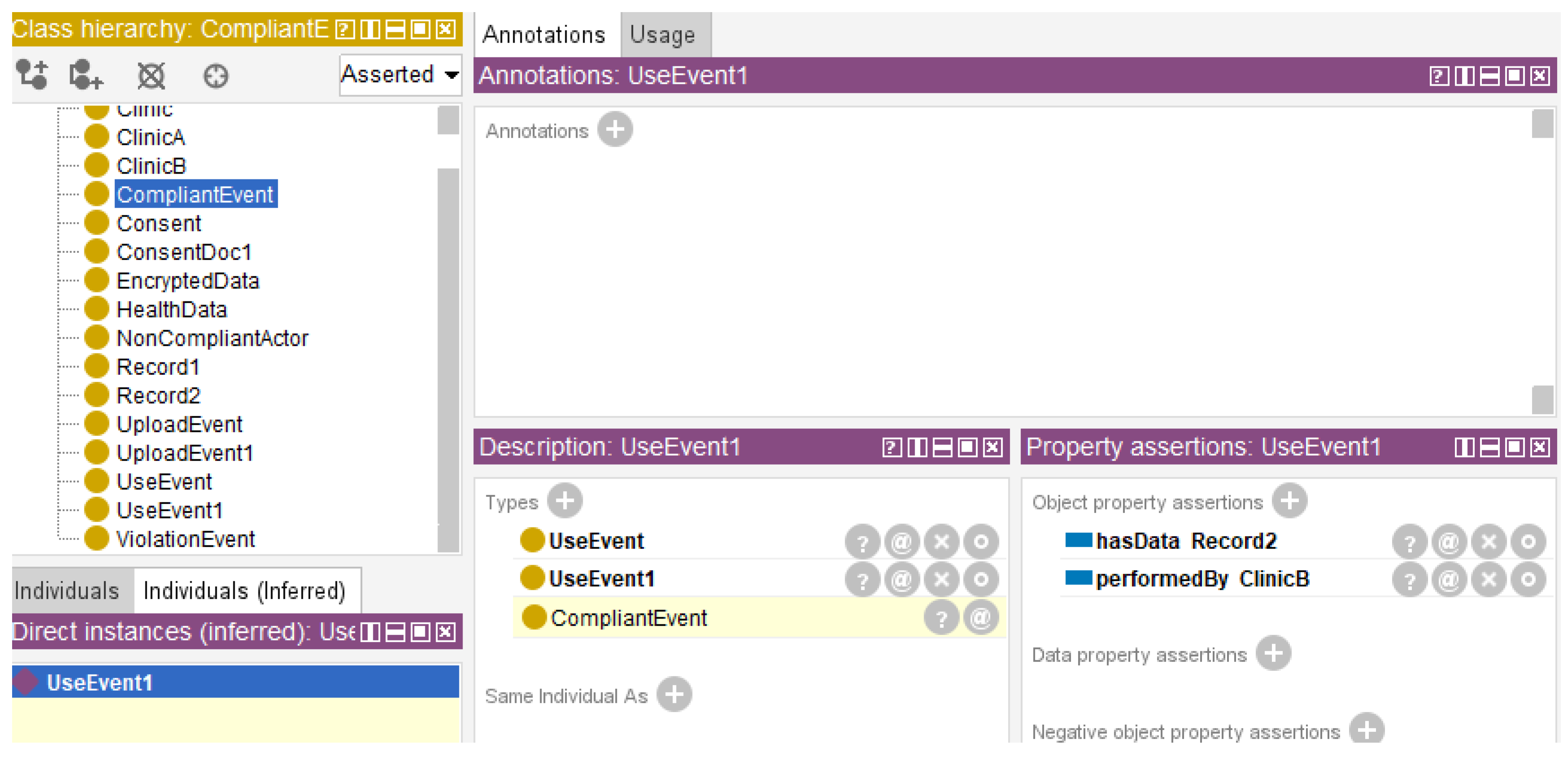

Experimental validation using open-source tools was conducted to assess the framework’s explainability and functionality. Two telehealth scenarios were simulated: a clinic uploads sensitive medical data without encryption or patient consent, representing a violation under HIPAA/GDPR, and another clinic accesses such data only with proper consent, representing compliance. The aim was to verify whether the framework correctly identifies violations and compliant actions and assigns accountability accordingly.

Two representative compliance scenarios were simulated. First, the clinic uploaded a health dataset without encryption or user consent. Second, a different clinic accessed the data explicitly, backed by a valid consent form. Using a small OWL ontology to define key classes (Clinic, HealthData, Consent, UploadEvent, UseEvent) and relationships (performedBy, hasData, hasConsent).

The corresponding SWRL rules were created to detect violations (ViolationEvent), recognize compliant actions (CompliantEvent), and assign accountability (NonCompliantActor). After loading the ontology and rules into Protégé, then executed Pellet reasoning to infer classifications based on defined semantic logic.

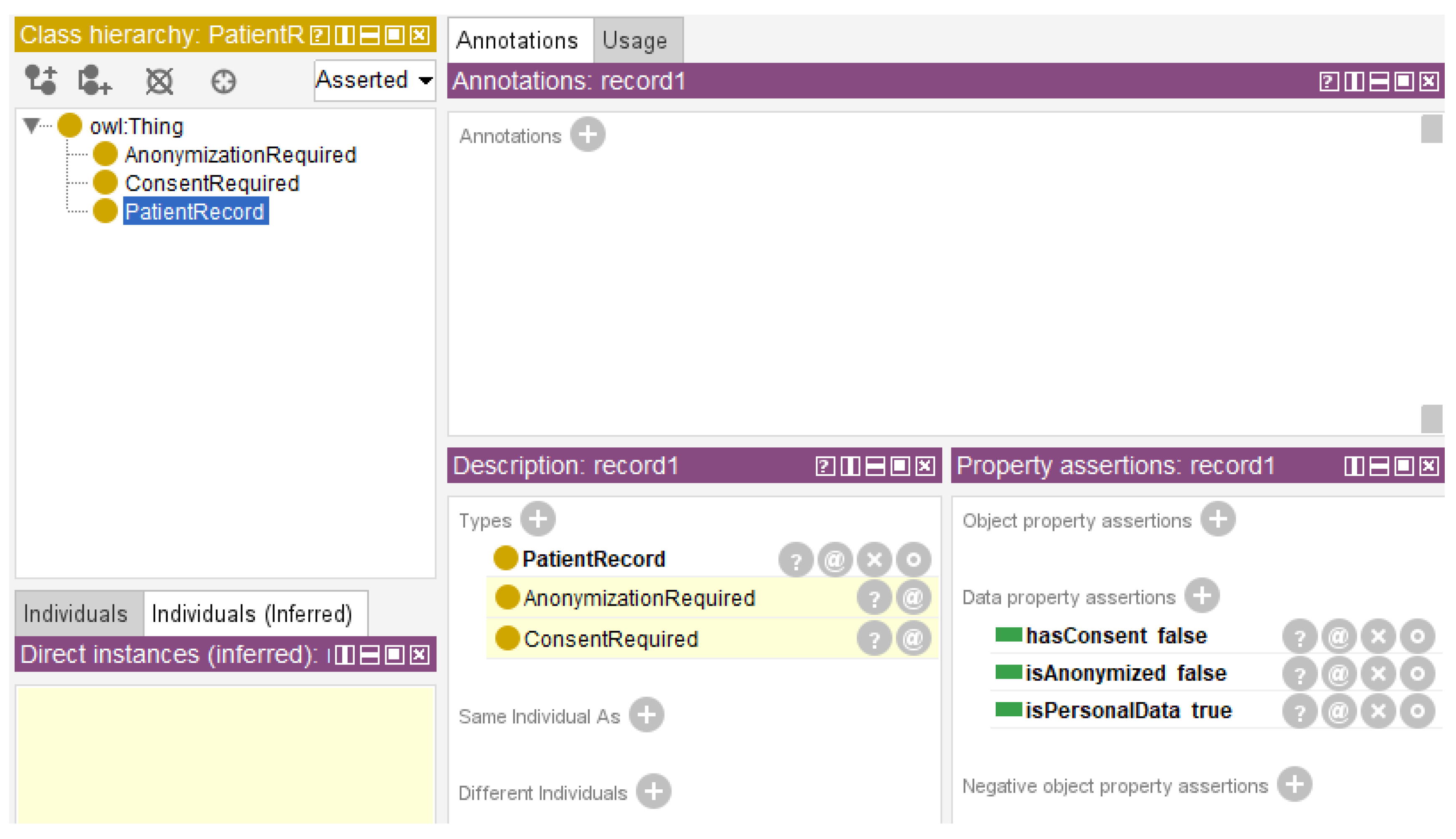

The results showed that the first scenario successfully validated the framework’s ability to detect non-compliance and trace responsibility. Specifically, the framework inferred that the data upload violated predefined rules and flagged it as a

ViolationEvent, assigning accountability to the uploading clinic (

Figure 3).

The second scenario demonstrated the framework’s support for compliant behavior under tenant-specific rules. When consent was present, the framework correctly inferred the event as a

CompliantEvent, confirming that data usage was permitted under the relevant policy. (

Figure 4).

These inferences provide a transparent, traceable explanatory path from input events to legal outcomes, allowing users and auditors to understand both what the architecture decided and why that decision was made.

The experiment confirmed that semantic reasoning paths defined in human-readable SWRL rules can serve as effective explanation mechanisms. Moreover, the architecture allows these paths to be visualized or exported, enabling the future development of graphical explanation tools such as rule-dependency graphs or semantic trace viewers. These outputs can further improve nontechnical users’ understanding and support legal and ethical auditing tasks.

To demonstrate these explainability features and evaluate policy separation, this framework implemented both the proposed semantic compliance architecture and a baseline static SWRL rule architecture in Protégé to demonstrate multi-tenant telehealth policy handling. In the setup, a single-based ontology represents generic clinical data. Two compliance rule sets were defined: a HIPAA policy, which requires patient consent before sharing personal health information, and a GDPR policy, which involves the anonymization of personal data before sharing. Under the static SWRL approach, all rules exist in one global ontology; switching policies require manual editing or replacement of SWRL rules. However, the semantic multi-tenant approach organizes each policy as a separate OWL module (importable ontology) that can be dynamically toggled per tenant. This reflects a standard multi-tenant design: one codebase serves multiple clients, with data and configurations partitioned such that each tenant’s policies can be customized. After running all the reasoning with the pellet reasoner in Protégé, observing the inferred class memberships and rule triggers.

Table 3 presents a conceptual comparison between the static and modular architectures for managing compliance rules in a multitenant telehealth framework. In the static architecture, all tenant-specific regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR are stored together in a shared ontology. The reasoning engine applies these rules globally without tenant-level separation. As a result, switching from one regulation to another requires manual editing of the combined rule set. Since all policies are active at the same time, there is a higher risk of rule interference.

In contrast, the modular architecture separates the shared ontology structure from tenant-specific policy rules. Each tenant’s rules are stored in an individual module, and the reasoning engine loads only the relevant module based on the current tenant context. This approach supports independent policy enforcement, avoids cross-tenant conflicts, and simplifies updates when new legal requirements are introduced.

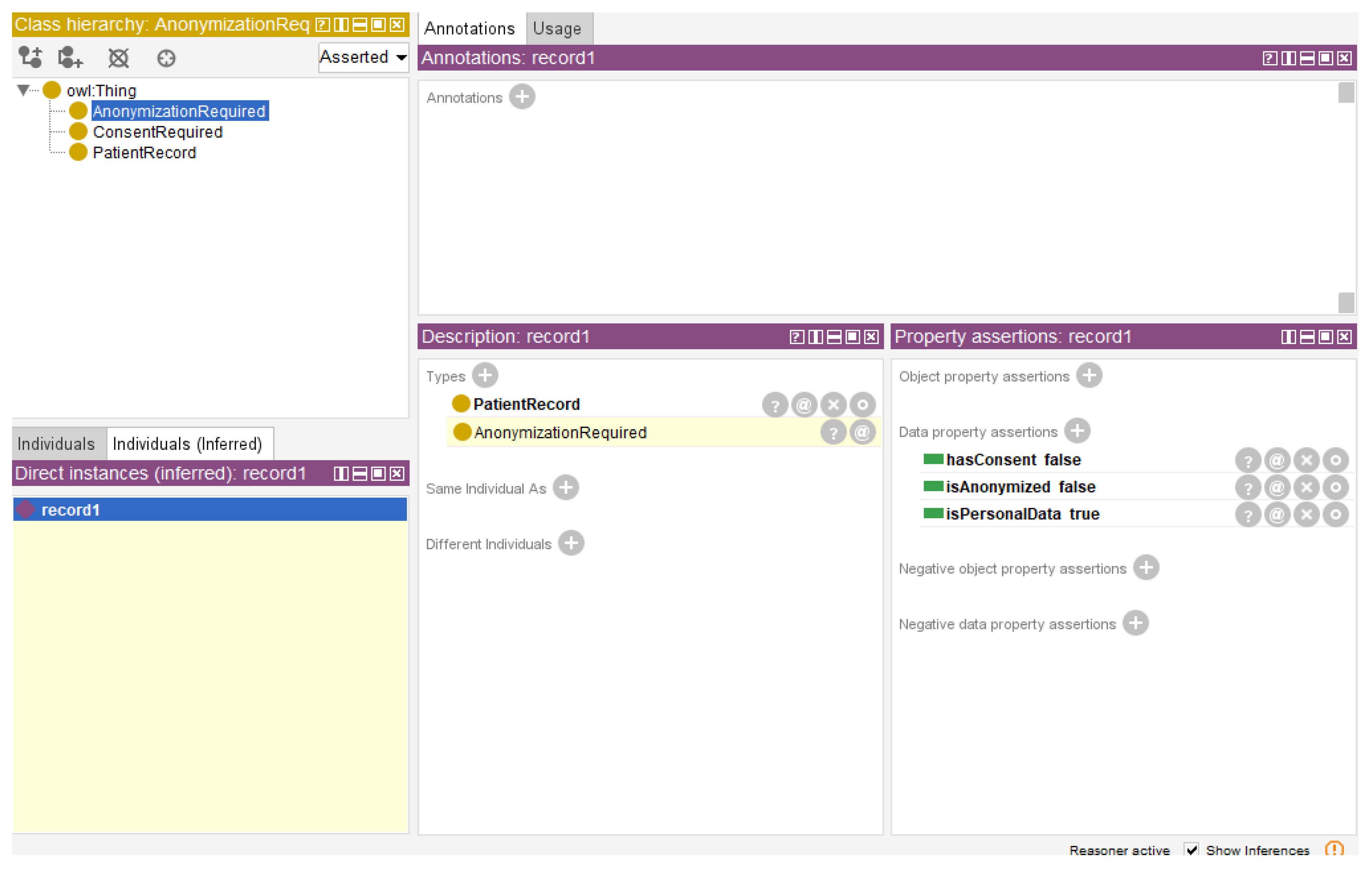

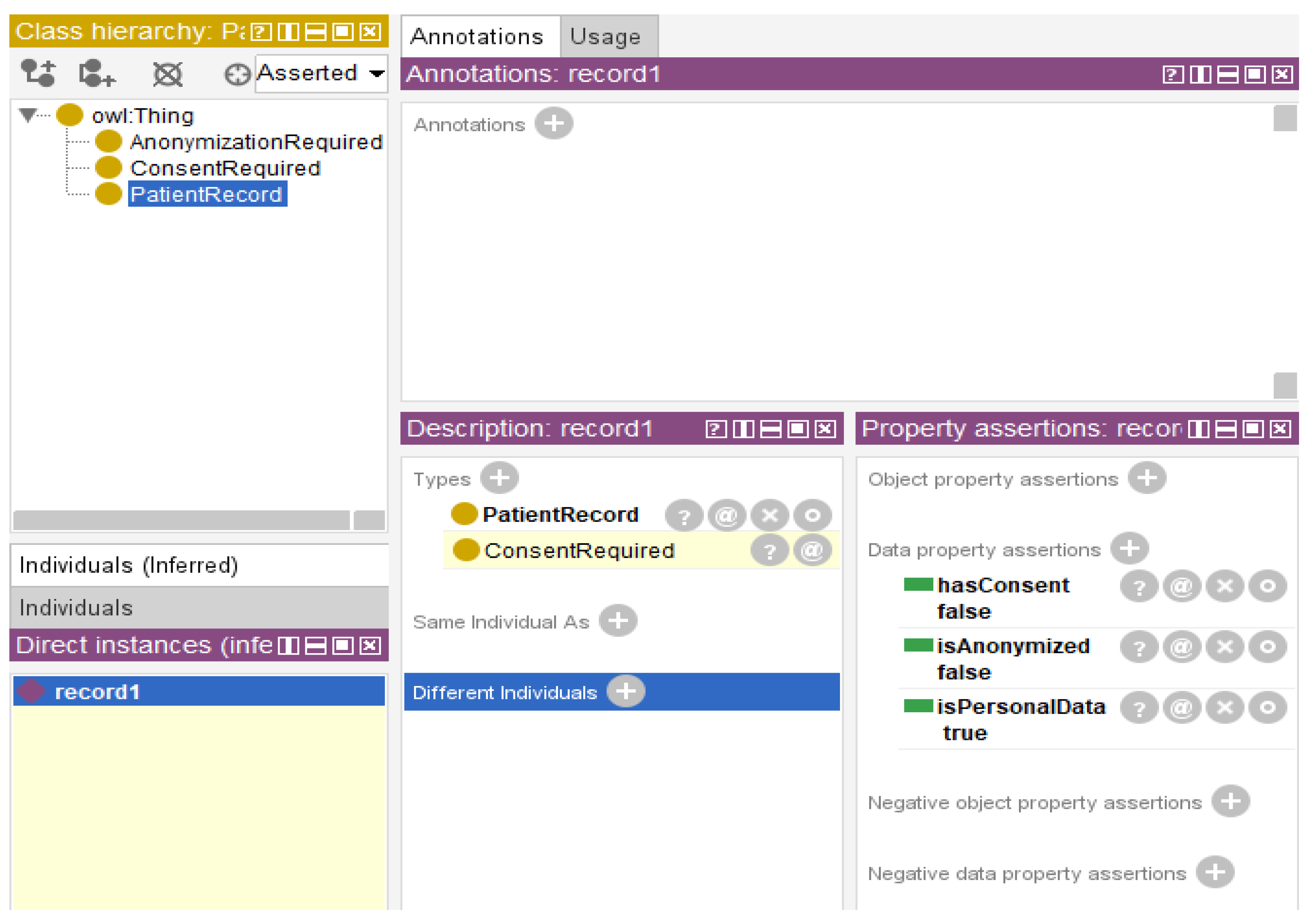

To evaluate the behavior of both static and modular rule architectures, the first step is create a base ontology named TelehealthPolicy, which defines a minimal but realistic structure for telehealth compliance reasoning. This ontology includes several core classes, such as PatientRecord, MedicalData, ConsentRequired, and AnonymizationRequired. Then define three Boolean data type properties: hasConsent, isAnonymized, and isPersonalData. As a sample data instance, then create an individual named record1, which was classified as Patient PatientRecord. Its properties were configured to simulate a non-consenting, non-anonymized personal health record; specifically, after setting hasConsent to false, isAnonymized to false, and isPersonalData to true.

With this foundation in place, this framework tested the static rule architecture by directly adding SWRL rules to the base ontology using Protégé’s SWRLTab plugin. To simulate HIPAA compliance, by creaing a rule stating that, if a patient record contains personal data and lacks consent, it should be classified as ConsentRequired. The rule is written in SWRL syntax as follows (5):

PatientRecord(?r) ^ hasConsent(?r, false) ^ isPersonalData(?r, true) → ConsentRequired(?r) (5)

This rule captures the common HIPAA requirement that patient consent should be obtained before handling personal data (

Figure 5).

Similarly, adding a second rule to reflect GDPR constraints

PatientRecord(?r) ^ isPersonalData(?r, true) ^ isAnonymized(?r, false) → AnonymizationRequired(?r) (6)

Under the GDPR, this rule represents the principle that personal data should be anonymized before sharing (

Figure 6).

To demonstrate the modular alternative, creating two additional ontologies: one containing only the HIPAA rule and the other containing only the GDPR rule. When testing the modular setup for Tenant A, only the HIPAA rule module was imported. As expected, Pellet inferred ConsentRequired(record1)—matching the earlier static result, but with the important distinction that GDPR rules were completely absent from the reasoning context. Tenant B was simulated by removing the HIPAA module and importing the GDPR module instead. Pellet now inferred AnonymizationRequired(record1), again consistent with the earlier outcome but isolated within its appropriate policy scope.

This demonstrates how the modular framework can dynamically switch tenant policies without modifying the main ontology or requiring the direct manipulation of SWRL rules. This architecture enables tenant-specific compliance reasoning with strong policy isolation and minimal maintenance efforts by encapsulating each policy within its rule module.

The experiments tested both rules simultaneously without separating them into modules. When both the HIPAA and GDPR rules were active simultaneously, the reasoner inferred that both

ConsentRequired and

AnonymizationRequired required the same individual. As shown in

Figure 7, individual

Record 1 was classified under both regulatory categories, although different legal frameworks controlled these requirements. The properties of

record1—including

hasConsent = false,

isAnonymized = false, and

isPersonalData = true—made it possible to trigger both rules at once.

This outcome demonstrates that static architecture applies all loaded rules globally without the ability to filter or isolate the tenant-specific compliance logic. In practical components, such behavior can lead to unintended rule collisions and misaligned enforcement, particularly when managing policies across jurisdictions.

Table 4 summarizes the key results of each scenario.

IV. Discussion

The experimental evaluation confirms that the semantic compliance framework operates in line with the probabilistic formulations. In each patient data scenario, the reasoning engine first initialized the prior violation probability according to the tenant–jurisdiction profile (1), implemented through the jurisdiction-specific policy modules in the ontology.

When case-specific evidence E was provided, such as consent status and encryption, the framework updated the prior to a posterior probability via Bayes’ theorem (2). This update was carried out in real time by the runtime policy engine, which evaluated the evidence vector against the active tenant’s rules.

Compliance decisions were then made using the Neyman–Pearson likelihood ratio test (3). In the modular configuration, the computation of was limited to the set of binary triggers in the active , consistent with the log-likelihood ratio decomposition under conditional independence (4). This ensured that the decision process aggregated only relevant evidence, preventing interference from unrelated regulations.

The benchmark comparison between modular and static configurations illustrates the impact of this scoped computation. In the static setup, where all GDPR and HIPAA rules were applied globally, overlapping triggers introduced contradictory evidence into the likelihood ratio calculation (4), resulting in inconsistent classifications. The modular design avoided this issue by maintaining isolated modules and dynamically importing only the relevant set for each tenant, preserving the validity of the Neyman–Pearson test (3) and its probabilistic interpretation.

Beyond consent and anonymization, the reasoning structure in this framework can accommodate other obligations, including access restrictions, geographic data residency, and multi-party approvals. Such requirements can be expressed as SWRL rules linked to ontology classes and integrated into the same probabilistic decision process without changes to the core architecture. The modular design also provides a foundation for role-sensitive explanations, enabling future extensions where outputs are adapted to the perspectives of different stakeholders.

From a performance standpoint, the present evaluation was conducted using a lightweight ontology and fewer than ten SWRL rules, comparable to a typical single-clinic consent workflow. The reasoning process, executed with the Pellet engine on a standard laptop (Intel i7, 16 GB RAM), completed within four seconds in all test scenarios. These results demonstrate the feasibility of latency-sensitive compliance enforcement under modest workloads. While full-scale benchmarking is beyond the current scope, the modular design avoids global rule loading by dynamically importing only the relevant tenant-specific policy modules. This scoped inference strategy is expected to scale linearly with the number of tenants, and because most rules operate on shallow logical conditions, performance is likely to remain acceptable even as the system expands. All ontologies, SWRL rules, and prototype scripts are publicly available at

https://anonymous.4open.science/r/conference-97F3/, enabling full reproducibility and further development by the research community.

V. Conclusion

This study examined the compliance challenges faced by multi-tenant AI platforms that operate under diverse legal jurisdictions and proposed a semantic compliance framework to address them. The framework uses OWL ontologies and SWRL rules to formalize obligations, permissions, and responsibilities in a structured form, making it possible to enforce rules for each tenant according to jurisdiction-specific policies. It combines semantic isolation, rule-based decision checks, and responsibility tracking to strengthen the accuracy of compliance enforcement and to provide verifiable audit trails. The compliance reasoning process was expressed in probabilistic terms, integrating prior violation probability, Bayesian updating, Neyman–Pearson likelihood ratio testing, and log-likelihood ratio decomposition. These components were implemented within the semantic architecture, ensuring that the decision logic is both theoretically grounded and operationally executable.

Evaluation with representative GDPR and HIPAA rules showed that the framework can detect violations, identify responsible entities, and explain the reasoning behind each decision. The modular design avoided cross-tenant policy interference and allowed new rules to be added without modifying the core system. Performance tests with a lightweight ontology and fewer than ten SWRL rules completed within four seconds on standard hardware, indicating that the approach can support latency-sensitive compliance enforcement.

The framework contributes to the development of transparent, modular, and extensible compliance systems for AI applications in regulated domains. By linking mathematical decision models to ontology-driven implementation, it provides a reproducible method for jurisdiction-aware, explainable compliance reasoning. Although the current evaluation focused on consent and anonymization, the same structure can be extended to other types of legal and operational constraints and adapted to provide role-sensitive explanations that align with the perspectives of different stakeholders.

In the longer term, such architecture may support automated legal auditing, facilitate cross-border data governance, and help to build trust in AI-assisted decision-making in sensitive fields such as healthcare and finance. This work offers both a framework for immediate application and a basis for further research on regulation-aware AI.

VI. Future Work

The scenarios in this study are intentionally small and representative, serving to validate the semantics-to-implementation mapping, the α-controlled operating point, and the modular isolation of jurisdictional rules. Scaling to larger datasets and additional clinics is planned for future work and will not alter the decision-theoretic core. Configuration files and scripts are available to reproduce the current results and the sensitivity/ablation analyses.

Future development of this framework may proceed in several directions. One potential extension is the integration of the semantic compliance layer with external components such as machine learning modules or decision support frameworks. A rule-based reasoning engine can assist in regulating and explaining the actions generated by the AI components. For example, if an external component produces a clinical-driven or data-driven outcome, the semantic layer can verify whether the action complies with the applicable legal constraints and document the justification for compliance or rejection. Because compliance reasoning is formalized through (1)–(4), the same mathematical process can be applied to a wider range of scenarios by defining appropriate rule triggers and evidence vectors, ensuring that new application domains inherit the same decision transparency and traceability.

References

- L. Xu, C. Zhao, W. Jiang, J. Ye, Y. Zhao and Z. Zhang, “Secure Encryption Scheme for Medical Data based on Homomorphic Encryption,” 2023 International Conference on Data Science and Network Security (ICDSNS), Tiptur, India, 2023, pp. 01-09. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, D. T. Liu, and P. Li, “Policy-driven security management for multi-tenant cloud applications,” IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1294–1307, Oct.–Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, “Building a Structured Reasoning AI Model for Legal Judgment in Telehealth Systems,” Preprints, Jul. 2025, preprint of paper presented at the 41st Int. RAIS Conf. on Social Sciences and Humanities, Washington, DC, USA, Aug. 2025. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, H. Wang, and H. Trimbach, “An OWL ontology representation for machine-learned functions using linked data,” 2016 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (BigData Congress), pp. 319–322, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Pandit, D. O’Sullivan, and D. Lewis, “GConsent: a consent ontology based on the GDPR,” Semantic Web, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 27–52, 2019.

- S. Batsakis et al., “A scalable reasoning engine for OWL 2 DL ontologies,” J. Web Semantics, vol. 43, pp. 55–74, 2017.

- Gyrard, S. Zimmermann, and I. Z. Álvarez, “Semantic Web technologies for the internet of things,” IEEE Internet Computing, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 54–63, Jul. 2019.

- S. Villata and F. Gandon, “Licentia: A linked data platform for licensing data,” Proc. International Semantic Web Conf., 2014, pp. 312–327.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).