Submitted:

30 August 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Metabolic Imperative in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy and Research

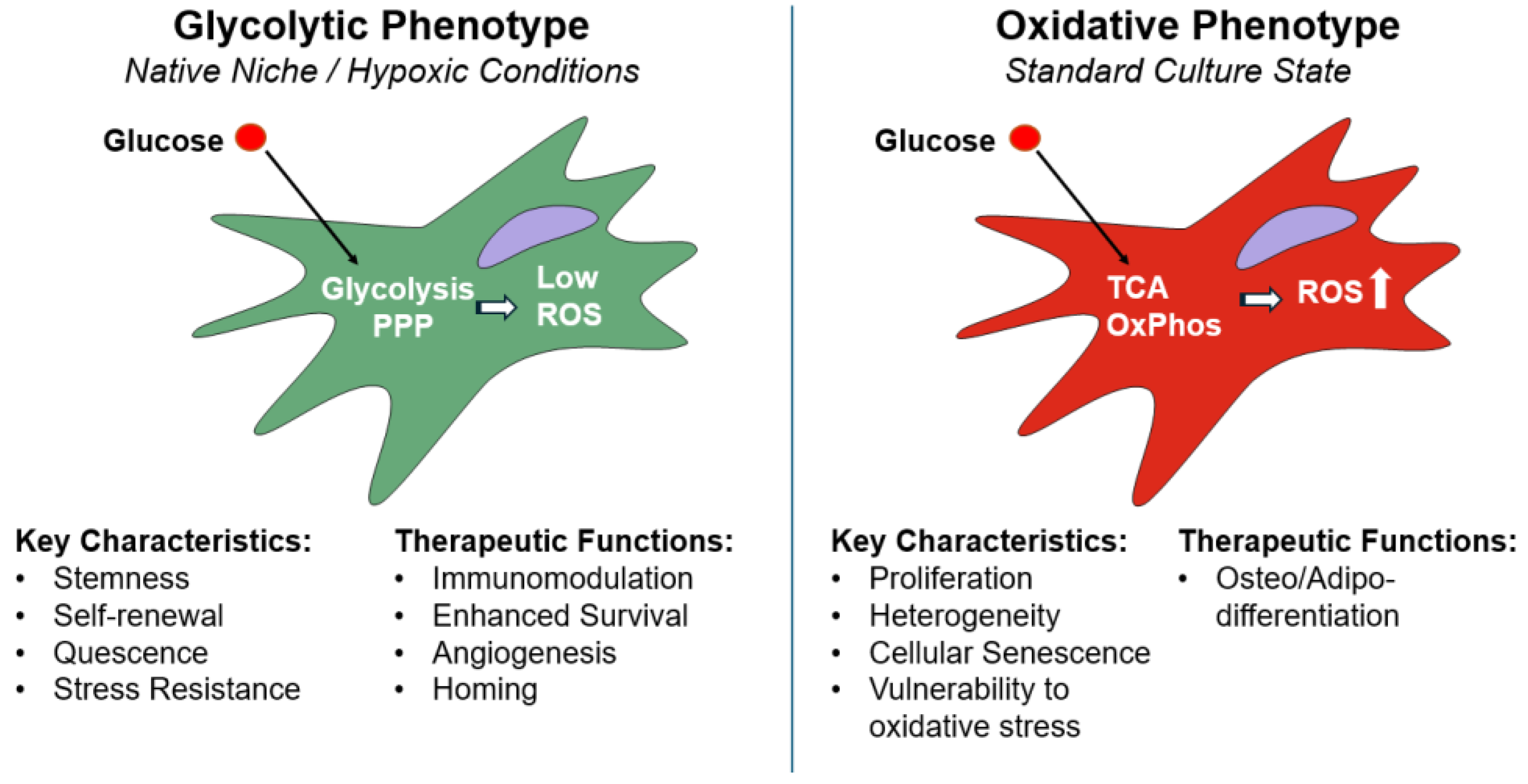

2. The Metabolic Landscape of MSCs: A Target for Engineering

2.1. The Native Niche's Metabolic Cues

2.2. Metabolic Changes Under Standard 2D Culture Expansion of MSCs

2.3. Metabolic "Switches" Dictate Function

2.3.1. Glycolytic Shift for Immunomodulation.

2.3.2. Metabolism and Differentiation.

2.3.3. Metabolic Adaptation to Stress.

3. Engineering MSC Metabolism Through Culture Parameter Modulation

3.1. Advanced Culture Systems: Mimicking the 3D Niche Physiological Complexity

3.2. Metabolic Modulation via Hypoxic Preconditioning

3.3. Nutrient and Media Composition

3.4. Cytokine Priming

3.5. Pharmacological Priming

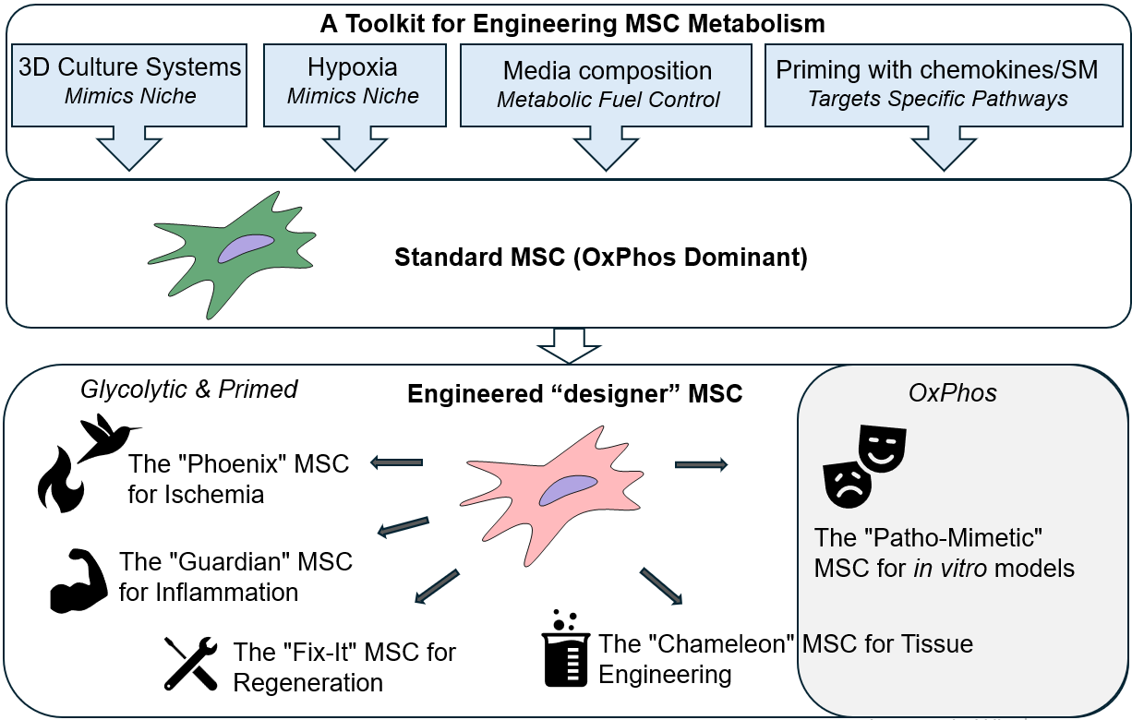

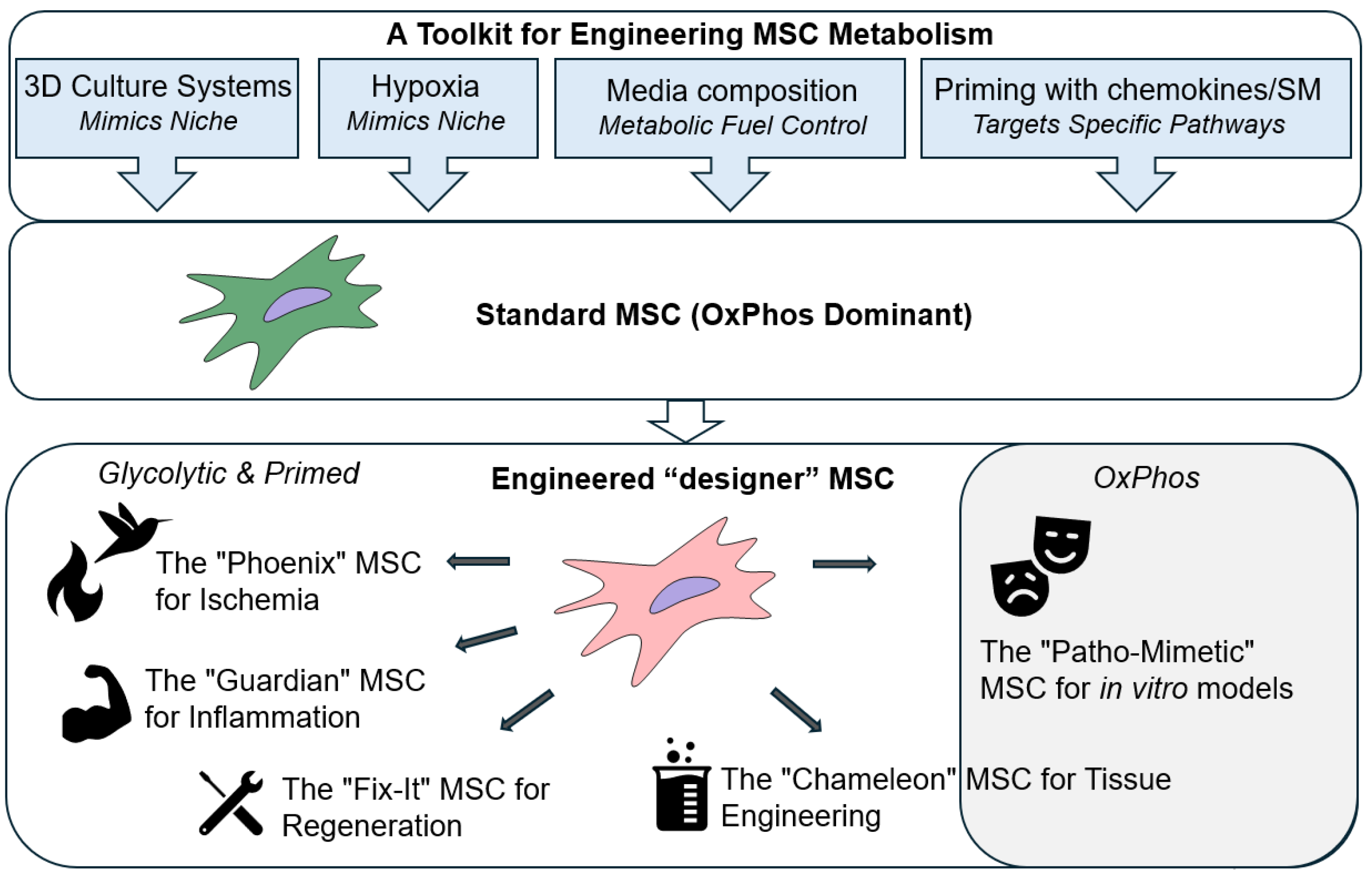

4. Future Directions: The Next Generations of "Smart" MSCs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Friedenstein, A. J.; Chailakhjan, R. K.; Lalykina, K. S. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell and tissue kinetics 1970, 3, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D. G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, V.; Pavelić, E.; Vrdoljak, K.; Čemerin, M.; Klarić, E.; Matišić, V.; Bjelica, R.; Brlek, P.; Kovačić, I.; Tremolada, C.; Primorac, D. Mesenchymal stem cell mechanisms of action and clinical effects in osteoarthritis: a narrative review. Genes 2022, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagno, L.L.; Salerno, A.G.; Balkan, W.; Hare, J. M. Mechanism of action of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): impact of delivery method. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2022, 22, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Gou, M.; Da, L.C.; Zhang, W.Q.; Xie, H.Q. Mesenchymal stem cells for chronic wound healing: current status of preclinical and clinical studies. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2020, 26, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Scholtemeijer, M.; Shah, K. Mesenchymal stem cell immunomodulation: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2020, 41, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira Paladino, F.; de Moraes Rodrigues, J.; da Silva, A.; Goldberg, A.C. The immunomodulatory potential of Wharton's jelly mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Stem cells Int 2019, 2019, 3548917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tam, P.K. H. immunomodulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cells and their potential clinical applications. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shi, Y. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs): origin, immune regulation, and clinical applications. Cell Mol Immunol 2023, 20, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Cho, S.G. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells. Korean J Intern Med 2013, 28, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afflerbach, A.K.; Kiri, M.D.; Detinis, T.; Maoz, B.M. mesenchymal stem cells as a promising cell source for integration in novel in vitro models. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, M.; Rožanc, J.; Vajda, J.; Činč Ćurić, L.; Paradiž, E.; Stožer, A.; Maver, U.; Vihar, B. In vitro disease models of the endocrine pancreas. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, J.; Sensébé, L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, K.P.; Galipeau, J.; Shi, Y.; Schuster, M.; Martin, I.; Viswanathan, S. Failure to launch commercially-approved mesenchymal stromal cell therapies: what's the path forward? Proceedings of the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) Annual Meeting Roundtable held in May 2023, Palais des Congrès de Paris, Organized by the ISCT MSC Scientific Committee. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folmes, C.D.; Dzeja, P.P.; Nelson, T.J.; Terzic, A. Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Menzies, K.J.; Auwerx, J. The role of mitochondria in stem cell fate and aging. Development 2018, 145, dev143420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, L.C.; White, N.S.; Mills, B.N.; Bentley, K.L.; Eliseev, R.A. Energy metabolism in mesenchymal stem cells during osteogenic differentiation. Stem Cells Dev 2016, 25, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Salamon, A.; Mispagel, S.; Kamp, G.; Peters, K. Energy metabolic capacities of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in vitro and their adaptations in osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Exp Cell Res 2018, 370, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmarsdottir, T.B.; McGarrity, S.; Yurkovich, J.T.; Rolfsson, Ó.; Sigurjónsson, Ó.E. Analyzing metabolic states of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells via genome scale metabolic model reconstruction. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 642681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadalipour, A.; Dumbali, S.P.; Wenzel, P.L. Mitochondrial transfer and regulators of mesenchymal stromal cell function and therapeutic efficacy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 603292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Chang, W.; Wei, H.; Zhang, K. Comparison of the biological characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and skin. Stem Cells Int 2016, 2016, 3658798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Su, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L. The heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells: an important issue to be addressed in cell therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.; Lin, M.; Miyazawa, B.; Nair, A.; Vivona, L.; Fang, X.; Bieback, K.; Schäfer, R.; Spohn, G.; McKenna, D.; Zhuo, H.; Matthay, M.A.; Pati, S. Inter- and intra-donor variability in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: implications for clinical applications. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareschi, K.; Ferrero, I.; Rustichelli, D.; Aschero, S.; Gammaitoni, L.; Aglietta, M.; Madon, E.; Fagioli, F. Expansion of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from pediatric and adult donor bone marrow. J Cell Biochem 2006, 97, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, K.; Dickinson, S.C.; Hollander, A.P. Changes in chondrogenic progenitor populations associated with aging and osteoarthritis. Cartilage 2015, 6, 30S–5S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, G.; Kluba, T.; Hermanutz-Klein, U.; Bieback, K.; Northoff, H.; Schäfer, R. Phenotype, donor age and gender affect function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Med 2013, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Nbaheen, M.; Vishnubalaji, R.; Ali, D.; Bouslimi, A.; Al-Jassir, F.; Megges, M.; Prigione, A.; Adjaye, J.; Kassem, M.; Aldahmash, A. Human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue and skin exhibit differences in molecular phenotype and differentiation potential. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2013, 9, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Tong, J.B.; Yang, X.X.; Zhao, J.L.; Zheng, Q.F.; Zhao, G.B.; Ma, Z.J. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue under xeno-free conditions for cell therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther 2015, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, M.; Sorjamaa, A.; Kangasniemi, M.; Sutinen, M.; Salo, T.; Liakka, A.; Lehenkari, P.; Tapanainen, J.S.; Vuolteenaho, O.; Chen, J.C.; Lehtonen, S.; Piltonen, T.T. Niche matters: The comparison between bone marrow stem cells and endometrial stem cells and stromal fibroblasts reveal distinct migration and cytokine profiles in response to inflammatory stimulus. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalloul, A. Hypoxia and visualization of the stem cell niche. Methods Mol Bio 2013, 1035, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattappa, G.; Heywood, H.K.; de Bruijn, J.D.; Lee, D.A. The metabolism of human mesenchymal stem cells during proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol 2011, 226, 2562–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyh-Chang, N.; Daley, G.Q.; Cantley, L.C. Stem cell metabolism in tissue development and aging. Development 2013, 140, 2535–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, T. Metabolic regulation of mesenchymal stem cell in expansion and therapeutic application. Biotechnol Prog 2015, 31, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Ito, K. Metabolism and the control of cell fate decisions and stem cell renewal. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2016, 32, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.T.; Shih, Y.R.; Kuo, T.K.; Lee, O.K.; Wei, Y.H. Coordinated changes of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Suda, T. Metabolic requirements for the maintenance of self-renewing stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Muñoz, N.; Bunnell, B.A.; Logan, T.M.; Ma, T. Density-dependent metabolic heterogeneity in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 3368–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bara, J.J.; Richards, R.G.; Alini, M.; Stoddart, M.J. Concise review: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells change phenotype following in vitro culture: implications for basic research and the clinic. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denu, R.A.; Hematti, P. Effects of oxidative stress on mesenchymal stem cell biology. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 2989076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denu, R.A.; Hematti, P. Optimization of oxidative stress for mesenchymal stromal/stem cell engraftment, function and longevity. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 167, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Lopez, R.; Elizondo-Vega, R.; Paredes, M.J.; Luque-Campos, N.; Torres, M.J.; Tejedor, G.; Vega-Letter, A.M.; Figueroa-Valdés, A.; Pradenas, C.; Oyarce, K.; Jorgensen, C.; Khoury, M.; Garcia-Robles, M.L.A.; Altamirano, C.; Djouad, F.; Luz-Crawford, P. HIF1α-dependent metabolic reprogramming governs mesenchymal stem/stromal cell immunoregulatory functions. FASEB J 2020, 34, 8250–8264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Muñoz, N.; Logan, T.M.; Ma, T. Commitment to aerobic glycolysis sustains immunosuppression of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med 2019, 8, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord-Dufour, S.; Copland, I.B.; Levros Jr, L.C.; Post, M.; Das, A.; Khosla, C.; Galipeau, J.; Rassart, E.; Annabi, B. Evidence for transcriptional regulation of the glucose-6-phosphate transporter by HIF-1alpha: Targeting G6PT with mumbaistatin analogs in hypoxic mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Lopez, R.A.; Elizondo-Vega, R.; Torres, M.J.; Vega-Letter, A.M.; Luque-Campos, N.; Paredes-Martinez, M.J.; Pradenas, C.; Tejedor, G.; Oyarce, K.; Salgado, M.; Jorgensen, C.; Khoury, M.; Kronke, G.; Garcia-Robles, M.A.; Altamirano, C.; Luz-Crawford, P.; Djouad, F. PPARβ/δ-dependent MSC metabolism determines their immunoregulatory properties. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 11423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wobma, H.M.; Tamargo, M.A.; Goeta, S.; Brown, LM.; Duran-Struuck, R.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. The influence of hypoxia and IFN-γ on the proteome and metabolome of therapeutic mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 2018, 167, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.O.; Eliseev, R.A. Energy metabolism during osteogenic differentiation: the role of Akt. Stem Cells Dev 2021, 30, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, C.; Khoury, M. Musculoskeletal progenitor/stromal cell-derived mitochondria modulate cell differentiation and therapeutical function. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 606781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.H.; Chang, C.C.; Shieh, M.J.; Wang, J.P.; Chen, Y.T.; Young, T.H.; Hung, S.C. . Hypoxia enhances chondrogenesis and prevents terminal differentiation through PI3K/Akt/FoxO dependent anti-apoptotic effect. Sci Rep, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschepper, M.; Oudina, K.; David, B.; Myrtil, V.; Collet, C.; Bensidhoum, M.; Logeart-Avramoglou, D.; Petite, H. Survival and function of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) depend on glucose to overcome exposure to long-term, severe and continuous hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med 2011, 15, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Ma, T. Compaction, fusion, and functional activation of three-dimensional human mesenchymal stem cell aggregate. Tissue Eng Part A 2015, 21, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.S.; Collins, J.J. Synthetic biology: applications come of age. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volarevic, V.; Markovic, B.S.; Gazdic, M.; Volarevic, A.; Jovicic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Armstrong, L.; Djonov, V.; Lako, M.; Stojkovic, M. Ethical and safety issues of stem cell-based therapy. Int J Med Sci 2018, 15, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, S.; Okada, H.; Hojo, H.; Ohba, S.; Iwata, J.; Komura, M.; Hikita, A.; Hoshi, K. Mesenchymal stromal cells in the bone marrow niche consist of multi-populations with distinct transcriptional and epigenetic properties. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 15811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.M.; Chen, C.S. Deconstructing the third dimension: how 3D culture microenvironments alter cellular cues. J Cell Sci 2012, 125, 3015–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Cekuc, M.S.; Ergul, Y.S.; Pius, A.K.; Shinohara, I.; Murayama, M.; Susuki, Y.; Ma, C.; Morita, M.; Chow, S.K.-H.; Goodman, S. B. 3D Culture of MSCs for Clinical Application. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, B.L.; Hsieh, C.C.; Hsu, P.J.; Chang, C.C.; Wang, L.T.; Yen, M.L. Three-Dimensional spheroid culture of human mesenchymal stem cells: offering therapeutic advantages and in vitro glimpses of the in vivo state. Stem Cells Transl Med 2023, 12, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroupis, D.; Correa, D. Increased mesenchymal stem cell functionalization in three-dimensional manufacturing settings for enhanced therapeutic applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 621748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Park, S.J.; Kang, S.K.; Kim, G.H.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, S.W.; Jeon, H.B.; Kim, H.S. Spherical bullet formation via E-cadherin promotes therapeutic potency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord blood for myocardial infarction. Mol Ther 2012, 20, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Pérez, J.; Ballesteros, P.; and Cerdán, S. Microscopic images of intraspheroidal pH by 1H magnetic resonance chemical shift imaging of pH sensitive indicators. Magma 2005, 18, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhang, S.H.; Lee, S.; Shin, J.-Y.; Lee, T.-J.; Kim, B.-S. Transplantation of cord blood mesenchymal stem cells as spheroids enhances vascularization. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 2138–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Yan, L.; Miao, Z.; Li, E.; Wong, K.H.; Xu, R.H. Spheroidal formation preserves human stem cells for prolonged time under ambient conditions for facile storage and transportation. Biomaterials 2017, 133, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trufanova, N.; Trufanov, O.; Bozhok, G.; Revenko, O.; Cherkashina, D.; Pakhomov, O.; Petrenko, O. Hypothermic storage of mesenchymal stromal cell-based spheroids at a temperature of 22°C. Probl Cryobiol Cryomed 2024, 34, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Muñoz, N.; Tsai, A.C.; Logan, T.M.; Ma, T. Metabolic reconfiguration supports reacquisition of primitive phenotype in human mesenchymal stem cell aggregates. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, P.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. The effects of spheroid formation of adipose-derived stem cells in a microgravity bioreactor on stemness properties and therapeutic potential. Biomaterials 2015, 41, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Li, J.R.; Young, T.H. Short-term spheroid formation enhances the regenerative capacity of adipose-derived stem cells by promoting stemness, angiogenesis, and chemotaxis. Stem Cells Transl Med 2013, 2, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.S.; Dai, L.G.; Yen, B.L.; Hsu, S.H. Spheroid formation of mesenchymal stem cells on chitosan and chitosan-hyaluronan membranes. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 6929–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.H.G.; McDevitt, T.C.; Cabral, J.M.S.; da Silva, C.L.; Ferreira, F.C. Tridimensional configurations of human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells to enhance cell paracrine potential towards wound healing processes. J Biotechnol 2017, 262, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhang, S.H.; Cho, S.W.; La, W.G.; Lee, T.J.; Yang, H.S.; Sun, A.Y.; Baek, S.H.; Rhie, J.W.; Kim, B.S. Angiogenesis in ischemic tissue produced by spheroid grafting of human adipose-derived stromal cells. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2734–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohori-Morita, Y.; Niibe, K.; Limraksasin, P.; Nattasit, P.; Miao, X.; Yamada, M.; Mabuchi, Y.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Egusa, H. Novel mesenchymal stem cell spheroids with enhanced stem cell characteristics and bone regeneration ability. Stem Cells Transl Med 2022, 11, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreda, M.; Hauptmann, N.; Lehner, V.; Biehl, C.; Liefeith, K.; Lips, K.S. Porous 3D Scaffolds enhance MSC vitality and reduce osteoclast activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trufanova, N.; Trufanov, O.; Bozhok, G.; Oberemok, R.; Revenko, O.; Petrenko, O. Bioengineering of mesenchymal-stromal-cell-based 3D constructs with different cell organizations. Eng Proc 2024, 81, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, Y. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-based vector biomaterials for clinical tissue engineering and inflammation research: a narrative mini review. J Inflamm Res 2023, 16, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Liu, W.; Li, J.J.; Liu, L.; Guo, A.; Wang, B.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; You, Z.; Lyu, C.; Li, W.; Liu, A.; Du, Y.; Lin, J. Engineering 3D functional tissue constructs using self-assembling cell-laden microniches. Acta Biomater 2020, 114, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangjantuk, A.; Kaokaen, P.; Kunhorm, P.; Chaicharoenaudomrung, N.; Noisa, P. 3D culture of alginate-hyaluronic acid hydrogel supports the stemness of human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malysz-Cymborska, I.; Golubczyk, D.; Walczak, P.; Stanaszek, L.; Janowski, M. Injectable, manganese-labeled alginate hydrogels as a matrix for longitudinal and rapidly retrievable 3D cell culture. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, C.S.; Fu, J. Forcing stem cells to behave: a biophysical perspective of the cellular microenvironment. Annu Rev Biophys 2012, 41, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, N.; Imran, S.A.M.; Ahmad Amin Noordin, K.B.; Zaman, W.S.W.K.; Nordin, F. Mechanotransduction in mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiation: a review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wright, B.; Sahoo, R.; Connon, C.J. A novel alternative to cryopreservation for the short-term storage of stem cells for use in cell therapy using alginate encapsulation. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2013, 19, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, J.B.; Rosa, G.D.S.; Rossi, M.C.; Stievani, F.C.; Pfeifer, J.P.H.; Krieck, A.M.T.; Bovolato, A.L.C.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; Borrás, V.A.; Alves, A.L.G. In vitro biological performance of alginate hydrogel capsules for stem cell delivery. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 674581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trufanova, N.; Hubenia, O.; Kot, Y.; Trufanov, O.; Kovalenko, I.; Kot, K.; Petrenko, O. Metabolic mode of alginate-encapsulated human mesenchymal stromal cells as a background for storage at ambient temperature. Biopreserv Biobank 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, A.; Tiago, A.L.; Laranjeira, P.; Carreira, M.C.; Milhano, J.C.; Dos Santos, F.; Cabral, J.M.S.; Paiva, A.; da Silva, C.L.; Fernandes-Platzgummer, A. Hypothermic Preservation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as a viable solution for the storage and distribution of cell therapy products. Bioengineering (Basel) 2022, 9, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klontzas, M.E.; Reakasame, S.; Silva, R.; Morais, J.C.F.; Vernardis, S.; MacFarlane, R.J.; Heliotis, M.; Tsiridis, E.; Panoskaltsis, N.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Mantalaris, A. Oxidized alginate hydrogels with the GHK peptide enhance cord blood mesenchymal stem cell osteogenesis: A paradigm for metabolomics-based evaluation of biomaterial design. Acta Biomater 2019, 88, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritz-Schiavi, J.; Charif, N.; Henrionnet, C.; de Isla, N.; Bensoussan, D.; Magdalou, J.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; Stoltz, J.F.; Huselstein, C. Original approach for cartilage tissue engineering with mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Mater Eng 2010, 20, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passanha, F.R.; Gomes, D.B.; Piotrowska, J.; Students of PRO3011; Moroni, L. ; Baker, M.B.; LaPointe, V.L.S. A comparative study of mesenchymal stem cells cultured as cell-only aggregates and in encapsulated hydrogels. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2022, 16, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, J.M.; Pucha, K.A.; Doan, T.N.; Wang, L.; Weinstock, L.D.; Tignor, B.T.; Fowle, K.L.; Levit, R.D.; Wood, L.B.; Willett, N.J. Sodium alginate microencapsulation of human mesenchymal stromal cells modulates paracrine signaling response and enhances efficacy for treatment of established osteoarthritis. Acta Biomater 2022, 141, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagneau, N.; Tournier, P.; Nativel, F.; Maugars, Y.; Guicheux, J.; Le Visage, C.; Delplace, V. Harnessing cell-material interactions to control stem cell secretion for osteoarthritis treatment. Biomaterials 2023, 296, 122091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Laurent, C.; Du, Q.; Targa, L.; Cauchois, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; de Isla, N. Mesenchymal stem cell interacted with PLCL braided scaffold coated with poly-l-lysine/hyaluronic acid for ligament tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A 2018, 106, 3042–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorodetsky, R.; Levdansky, L.; Gaberman, E.; Gurevitch, O.; Lubzens, E.; McBride, W.H. Fibrin microbeads loaded with mesenchymal cells support their long-term survival while sealed at room temperature. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2011, 17, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czosseck, A.; Chen, M.M.; Nguyen, H.; Meeson, A.; Hsu, C.C.; Chen, C.C.; George, T.A.; Ruan, S.C.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Lin, P.J.; Hsieh, P.C.H.; Lundy, D.J. Porous scaffold for mesenchymal cell encapsulation and exosome-based therapy of ischemic diseases. J Control Release 2022, 352, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Sun, B.; Han, Y.; Yu, B.; Xin, W.; Xu, R.; Ni, B.; Jiang, W.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Dai, K. A low-temperature-printed hierarchical porous sponge-like scaffold that promotes cell-material interaction and modulates paracrine activity of MSCs for vascularized bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2021, 274, 120841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, J.R.K.; Rangasami, V.K.; Samanta, S.; Varghese, O.P.; Oommen, O.P. Discrepancies on the role of oxygen gradient and culture condition on mesenchymal stem cell fate. Adv Healthc Mater 2021, 10, e2002058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, F.; Andrade, P.Z.; Boura, J.S.; Abecasis, M.M.; da Silva, C.L.; Cabral, J.M. Ex vivo expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells: a more effective cell proliferation kinetics and metabolism under hypoxia. J Cell Physiol 2010, 223, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, J.C.; Albo, C.; Benguría, A.; Dopazo, A.; López-Romero, P.; Carrera-Quintanar, L.; Roche, E.; Clemente, E.P.; Enríquez, J.A.; Bernad, A.; Samper, E. Culture of human mesenchymal stem cells at low oxygen tension improves growth and genetic stability by activating glycolysis. Cell Death Differ 2012, 19, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyette, L.B.; Creasey, O.A.; Guzik, L.; Lozito, T.; Tuan, R.S. Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells display enhanced clonogenicity but impaired differentiation with hypoxic preconditioning. Stem Cells Transl Med 2014, 3, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.S.; Ko, Y.J.; Lee, M.W.; Park, H.J.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, D.I.; Sung, K. W.; Koo, H.H.; Yoo, K.H. Effect of low oxygen tension on the biological characteristics of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, N.; Kim, J.; Liu, Y.; Logan, T.M.; Ma, T. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of human mesenchymal stem cell metabolism during proliferation and osteogenic differentiation under different oxygen tensions. J Biotechnol 2014, 169, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattappa, G.; Thorpe, S.D.; Jegard, N.C.; Heywood, H.K.; de Bruijn, J.D.; Lee, D.A. Continuous and uninterrupted oxygen tension influences the colony formation and oxidative metabolism of human mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2013, 19, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylotte, L.A.; Duffy, A.M.; Murphy, M.; O'Brien, T.; Samali, A.; Barry, F.; Szegezdi, E. Metabolic flexibility permits mesenchymal stem cell survival in an ischemic environment. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrer, C.; Brunauer, R.; Laschober, G.; Unterluggauer, H.; Reitinger, S.; Kloss, F.; Gülly, C.; Gassner, R.; Lepperdinger, G. Reduced oxygen tension attenuates differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells and prolongs their lifespan. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, I.; Cairns, R.A.; Fontana, L.; Lim, A.L.; Denko, N.C. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L.; Roth, P.H.; Fang, H.M.; Wang, G.L. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 1994, 269, 23757–23763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Tchernyshyov, I.; Semenza, G.L.; Dang, C.V. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, B.; Hua, T.; Li, F.; Han, J.; Fang, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Jiang, X. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α protects mesenchymal stem cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced injury via autophagy induction and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Am J Transl Res 2017, 9, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Beegle, J.; Lakatos, K.; Kalomoiris, S.; Stewart, H.; Isseroff, R.R.; Nolta, J.A.; Fierro, F.A. Hypoxic preconditioning of mesenchymal stromal cells induces metabolic changes, enhances survival, and promotes cell retention in vivo. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 1818–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Li, F.; Han, J.; Fang, J.; Xu, L; Sun, C. ; Hua, T.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Jiang, X. Hif-1α overexpression improves transplanted bone mesenchymal stem cells survival in rat MCAO stroke model. Front Mol Neurosci 2017, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Jiang, B.H.; Chin, B.Y.; Iyer, N.V.; Alam, J.; Semenza, G.L.; Choi, A.M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 5375–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, K.M.; Aly, A.; Lerman, A.; Lerman, L.O.; Rodriguez-Porcel, M. Improved survival of mesenchymal stromal cell after hypoxia preconditioning: role of oxidative stress. Life Sci 2011, 88, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, K.; Salim, A.; Hashim, Z.; Ilyas, A.; Syed, B.; Ahmed, A.; Zarina, S. Chemical hypoxic preconditioning improves survival and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2024, 196, 3719–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S.; Zhou, Y.N.; Li, L.; Li, S.F.; Long, D.; Chen, X.L.; Zhang, J.B.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.P. HIF-1α protects against oxidative stress by directly targeting mitochondria. Redox Biol 2019, 25, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hao, H.; Xia, L.; Ti, D.; Huang, H.; Dong, L.; Tong, C.; Hou, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Fu, X.; Han, W. Hypoxia pretreatment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells facilitates angiogenesis by improving the function of endothelial cells in diabetic rats with lower ischemia. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0126715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Hao, H.; Xia, L.; Liu, J.; Ti, D.; Dong, L.; Hou, Q.; Song, H.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, X.; Han, W. Hypoxia pretreatment of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells seeded in a collagen-chitosan sponge scaffold promotes skin wound healing in diabetic rats with hindlimb ischemia. Wound Repair Regen 2016, 24, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; He, C.; Ma, B.; Lankford, L.; Reynaga, L.; Farmer, D.L.; Guo, F.; Wang, A. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances survival and proangiogenic capacity of human first trimester chorionic villus-derived mesenchymal stem cells for fetal tissue engineering. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 9695239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, F.M.; Nakashima, A.; Kawano, K.I.; Kajikawa, M.; Kishimoto, S.; Maruhashi, T.; Ishiuchi, N.; Abdul Wahid, S.F.S.; Higashi, Y. Implantation of hypoxia-induced mesenchymal stem cell advances therapeutic angiogenesis. Stem Cells Int 2022, 2022, 6795274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Liang, B.; Wang, H.; Hou, J.; Yuan, Q. Hypoxia pretreatment improves the therapeutic potential of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in hindlimb ischemia via upregulation of NRG-1. Cell Tissue Res 2022, 388, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jin, H.; Heo, J.; Ju, H.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lim, J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kwon, J.; Kim, M.; Choi, S.J.; Oh, W.; Yang, Y.S.; Hwang, H.H.; Yu, H.Y.; Ryu, C.M.; Jeon, H.B.; Shin, D.M. Small hypoxia-primed mesenchymal stem cells attenuate graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2672–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.M.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.Y.; Xiao, L.; An, S.; Gou, Y.C.; Quan, H.X.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; He, W.; Wang, Y. T.; Yu, W.J.; Huang, Y.F.; Yi, Y.T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of hypoxia on the immunomodulatory properties of human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Dent Res 2015, 94, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobma, H.M.; Kanai, M.; Ma, S.P.; Shih, Y.; Li, H.W.; Duran-Struuck, R.; Winchester, R.; Goeta, S.; Brown, L.M.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Dual IFN-γ/hypoxia priming enhances immunosuppression of mesenchymal stromal cells through regulatory proteins and metabolic mechanisms. J Immunol Regen Med 2018, 1, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bister, N.; Pistono, C.; Huremagic, B.; Jolkkonen, J.; Giugno, R.; Malm, T. Hypoxia and extracellular vesicles: a review on methods, vesicular cargo and functions. J Extracell Vesicles 2020, 10, e12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeria, C.; Weiss, R.; Roy, M.; Tripisciano, C.; Kasper, C.; Weber, V.; Egger, D. Hypoxia conditioned mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles induce increased vascular tube formation in vitro. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019, 7, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Xun, C.; Li, W.; Jin, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhuo, Y.; Duan, D.; Hu, Z.; Chen, P.; Lu, M. Extracellular vesicles derived from hypoxia-preconditioned olfactory mucosa mesenchymal stem cells enhance angiogenesis via miR-612. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, J.; Hart, D.A.; Mitha, A.P.; Duncan, N.A.; Sen, A. Physiological oxygen conditions enhance the angiogenic properties of extracellular vesicles from human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023, 14, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Escribano, V.; Torrecillas-Baena, B.; Camacho-Cardenosa, M.; Dorado, G.; Gálvez-Moreno, M.Á.; Casado-Díaz, A. Role of hypoxia preconditioning in therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem-cell-derived extracellular vesicles. World J Stem Cells 2022, 14, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, C.L.; da Silva, L.R.; Santos, R.T.; de Carvalho, L.R.P.; Mandacaru, S.C.; de Oliveira Trugilho, M.R.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Cruz, F.F.; Silva, P.L. Proteomics profile of mesenchymal stromal cells and extracellular vesicles in normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Cytotherapy 2022, 24, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y. Roles of hypoxia during the chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2014, 9, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.P.; Ho, J.H.; Shih, Y.R.; Lo, T.; Lee, O.K. Hypoxia promotes proliferation and osteogenic differentiation potentials of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res 2012, 30, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, D.P.; Edmison, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Cultivation of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in reduced oxygen tension: effects on in vitro and in vivo osteochondrogenesis. J Cell Physiol 2001, 187, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzwarth, C.; Vaegler, M.; Gieseke, F.; Pfister, S.M.; Handgretinger, R.; Kerst, G.; Müller, I. Low physiologic oxygen tensions reduce proliferation and differentiation of human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Cell Biol 2010, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, A.; Nacamuli, R.P.; Morgan, E.F.; Giaccia, A.J.; Longaker, M.T. Transient changes in oxygen tension inhibit osteogenic differentiation and Runx2 expression in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 40007–40016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malladi, P.; Xu, Y.; Chiou, M.; Giaccia, A.J.; Longaker, M.T. Effect of reduced oxygen tension on chondrogenesis and osteogenesis in adipose-derived mesenchymal cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006, 290, C1139–C1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosová, I.; Dao, M.; Capoccia, B.; Link, D.; Nolta, J.A. Hypoxic preconditioning results in increased motility and improved therapeutic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Peng, L.; Dai, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Zhu, C. Hypoxia preconditioning of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells enhances proliferation and migration and promotes their homing via the HGF/C-MET signaling axis to augment the repair of acute liver failure. Tissue Cell 2024, 87, 102326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-El-Rub, E.; Almahasneh, F.; Khasawneh, R.R.; Alzu'bi, A.; Ghorab, D.; Almazari, R; Magableh, H. ; Sanajleh, A.; Shlool, H.; Mazari, M.; Bader, N.S.; Al-Momani, J. Human mesenchymal stem cells exhibit altered mitochondrial dynamics and poor survival in high glucose microenvironment. World J Stem Cells 2023, 15, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahasneh, F.; Abu-El-Rub, E.; Khasawneh, R.R.; Almazari, R. Effects of high glucose and severe hypoxia on the biological behavior of mesenchymal stem cells at various passages. World J Stem Cells 2024, 16, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, C.; Freisinger, E.; Jones, R.K.; Slakey, D.P.; Dupin, C.L.; Newsome, E.R.; Alt, E.U.; Izadpanah, R. Persistent high glucose concentrations alter the regenerative potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2010, 19, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Lu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B.; Yuan, Z.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Pan, J. High glucose induces the aging of mesenchymal stem cells via Akt/mTOR signaling. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasawneh, R.R.; Abu-El-Rub, E.; Almahasneh, F.A.; Alzu'bi, A.; Zegallai, H.M.; Almazari, R.A.; Magableh, H.; Mazari, M.H.; Shlool, H.F.; Sanajleh, A.K. Addressing the impact of high glucose microenvironment on the immunosuppressive characteristics of human mesenchymal stem cells. IUBMB Life 2024, 76, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateen, M.A.; Alaagib, N.; Haider, K.H. High glucose microenvironment and human mesenchymal stem cell behavior. World J Stem Cells 2024, 16, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangprom, S.; Kheolamai, P.; Tantrawatpan, C.; Manochantr, S. High glucose inhibits proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 22512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yan, B.; Yu, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Pan, J. Coenzyme Q10 inhibits the aging of mesenchymal stem cells induced by D-galactose through Akt/mTOR signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 867293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, C.; Pardo, R.; Bou-Teen, D.; Ruiz-Meana, M.; Villena, J. A.; Ferreira-González, I.; Barba, I. Enhancing glycolysis protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing ros production. Metabolites 2020, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, B.R.; Abarbanell, A.M.; Herrmann, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Meldrum, D.R. High glucose concentration in cell culture medium does not acutely affect human mesenchymal stem cell growth factor production or proliferation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009, 296, R1735–R1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.; Scotchford, C.; Gran,t D. ; Sottile, V. Impact of serum source on human mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic differentiation in culture. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannasi, C.; Niada, S.; Della Morte, E.; Casati, S.R.; De Palma, C.; Brini, A.T. Serum starvation affects mitochondrial metabolism of adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Cytotherapy 2023, 25, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asti, A.L.; Croce, S.; Valsecchi, C.; Lenta, E.; Grignano, M.A.; Gregorini, M.; Carolei, A.; Comoli, P.; Zecca, M.; Avanzini, M.A.; Rampino, T. Characterization of mesenchymal stromal cells after serum starvation for extracellular vesicle production. Appl Sci 2024, 14, 5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, B.T.; Le, H.T.; Nguyen, K.N.; Van Pham, P. Hypoxia, serum starvation, and TNF-α can modify the immunomodulation potency of human adipose-derived stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol, 6 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskowitz, A.; McFerrin, H.; Gutschow, M.; Carter, M.L.; Pochampally, R. Serum-deprived human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are highly angiogenic. Stem Cell Res 2011, 6, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraszti, R.A.; Miller, R.; Dubuke, M.L.; Rockwell, H.E.; Coles, A.H.; Sapp, E.; Didiot, M.C.; Echeverria, D.; Stoppato, M.; Sere, Y.Y.; et al. Serum deprivation of mesenchymal stem cells improves exosome activity and alters lipid and protein composition. iScience 2019, 16, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochampally, R.R.; Smith, J.R.; Ylostalo, J.; Prockop, D.J. Serum deprivation of human marrow stromal cells (hMSCs) selects for a subpopulation of early progenitor cells with enhanced expression of OCT-4 and other embryonic genes. Blood 2004, 103, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, K.Y.C.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.Y.; Tse, W.Y.; Tong, C.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.M.; Ker, D.F.E. The Characterization of serum-free media on human mesenchymal stem cell fibrochondrogenesis. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, B.Y.; Sagun, J.E.; Leach, J.K. Reduced serum and hypoxic culture conditions enhance the osteogenic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2015, 11, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, C.A.; Roxby, D.N.; Othman, R.; Denslin, V.; Bhat, K.S.; Yang, Z.; Han, J.; Tucker-Kellogg, L.; Boyer, L.A. Metabolic modulation to improve MSC expansion and therapeutic potential for articular cartilage repair. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, N.C.; Mizukami, A.; Caliári-Oliveira, C.; Cominal, J.G.; Rocha, J.L.M.; Covas, D.T.; Swiech, K.; Malmegrim, K.C.R. Priming approaches to improve the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigo, T.; La Rocca, C.; Faicchia, D.; Procaccini, C.; Ruggieri, M.; Salvetti, M.; Centonze, D.; Matarese, G.; Uccelli, A.; MSRUN Network. IFNβ enhances mesenchymal stromal (Stem) cells immunomodulatory function through STAT1-3 activation and mTOR-associated promotion of glucose metabolism. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendt, M.; Daher, M.; Basar, R.; Shanley, M.; Kumar, B.; Wei Inng, F.L.; Acharya, S.; Shaim, H.; Fowlkes, N.; Tran, J.P.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming of GMP grade cord tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells enhances their suppressive potential in GVHD. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 631353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, J.; Yáñez, R.M.; Muntión, S.; Fernández-García, M.; Martín-Rufino, J.D.; Zapata, A.G.; Bueren, J.A.; Vicente, Á.; Sánchez-Guijo, F. Improving the therapeutic profile of MSCs: Cytokine priming reduces donor-dependent heterogeneity and enhances their immunomodulatory capacity. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1473788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Chen, Z.; He, X.; Long, J.; Xia, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ao, L.; Xing, W.; Lian, Q.; Liang, H.; Xu, X. Cross talk between glucose metabolism and immunosuppression in IFN-γ-primed mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci Alliance 2022, 5, e202201493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Lopez, R.; Elizondo-Vega, R.; Luque-Campos, N.; Torres, M.J.; Pradenas, C.; Tejedor, G.; Paredes-Martínez, M.J.; Vega-Letter, A.M.; Campos-Mora, M.; Rigual-Gonzalez, Y.; et al. The ATP synthase inhibition induces an AMPK-dependent glycolytic switch of mesenchymal stem cells that enhances their immunotherapeutic potential. Theranostics 2021, 11, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Jung, Y.H.; Choi, G.E.; Kim, J.S.; Chae, C.W.; Lim, J.R.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Park, M.C.; Yoon, J.H.; Choi, M.J.; Kim, K.S.; Han, H.J. O-cyclic phytosphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates HIF1α-dependent glycolytic reprogramming to enhance the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Coats, A.B.; Tuazon, J.P.; Jo, M.; Borlongan, C.V. Rhynchophylline promotes stem cell autonomous metabolic homeostasis. Cytotherapy 2020, 22, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Dai, J.; Pan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Y.; Qin, T.; Ouyang, H. Sodium lactate promotes stemness of human mesenchymal stem cells through KDM6B mediated glycolytic metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020, 532, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isildar, B.; Ozkan, S.; Neccar, D.; Koyuturk, M. Preconditioning and post-preconditioning states of mesenchymal stem cells with deferoxamine: a comprehensive analysis. Eur J Pharmacol 2025, 996, 177574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isildar, B.; Ozkan, S.; Sahin, H.; Ercin, M.; Gezginci-Oktayoglu, S.; Koyuturk, M. Preconditioning of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells with deferoxamine potentiates the capacity of the secretome released from the cells and promotes immunomodulation and beta cell regeneration in a rat model of type 1 diabetes. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 129, 111662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, K.; Takami, T.; Okada, S.; Hara, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Yamasaki, T.; Sakaida, I. Analysis of metabolomic changes in mesenchymal stem cells on treatment with desferrioxamine as a hypoxia mimetic compared with hypoxic conditions. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaraba-Álvarez, W.V.; Uscanga-Palomeque, A.C.; Sanchez-Giraldo, V.; Madrid, C.; Ortega-Arellano, H.; Halpert, K.; Quintero-Gil, C. Hypoxia-induced metabolic reprogramming in mesenchymal stem cells: unlocking the regenerative potential of secreted factors. Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13, 1609082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).