1. Introduction

Dysregulated lipid metabolism is associated with several human diseases, including cardiovascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [

1,

2,

3]. The steady rise of these diseases has created a global cardiometabolic health crisis, with wide-ranging health, social, and economic consequences [

4]. Whole-body lipid homeostasis relies on both dietary fat and

de novo synthesis, primarily in the liver, to supply structural lipids and energy substrates [

5]. White adipose tissue (WAT) stores triglycerides and releases fatty acids during fasting, whereas brown adipose tissue (BAT) oxidizes fatty acids to fuel thermogenesis [

6,

7]. The balance between lipid storage in WAT and lipid utilization in BAT is a central determinant of metabolic health. Lipid metabolism is coordinated by insulin signaling, which helps explain why diseases associated with dysfunctional insulin signaling, including obesity and T2D, are also characterized by dysregulated lipid metabolism [

8,

9,

10].

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP1a, SREBP1c, and SREBP2) are transcription factors that control the expression of genes involved in cholesterol, fatty acid, and triglyceride synthesis and metabolism [

11,

12,

13,

14]. SREBP1c and SREBP2 are expressed in most mammalian cells and control genes involved in fatty acid/triglyceride and cholesterol synthesis, respectively. SREBP1a is the strongest transcription factor of the family and activates most SREBP target genes. Thus, SREBP1a is highly expressed in rapidly dividing cells, including cancer cells, to ensure a sufficient supply of lipids to support cell growth/proliferation. All three SREBPs are synthesized as large precursor proteins that are inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and need to be proteolytically cleaved to generate the active transcription factors [

15,

16,

17]. The activation of SREBP1/2 is dependent on their transport from the ER to the Golgi, a process that is regulated by intracellular cholesterol levels and insulin signaling. In the ER, the SREBP precursor proteins interact with a sterol-sensing chaperone protein known as SREBP cleavage activating protein (SCAP). When mammalian cells are deprived of cholesterol, SCAP escorts SREBP1/2 in COPII vesicles from the ER to the Golgi. In the Golgi, two proteases (S1P and S2P) sequentially cleave SREBP1/2, releasing the N-terminal transcriptional domains, which translocate to the nucleus and activate genes involved in fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis and uptake [

11]. When the amount of cholesterol in the ER membrane exceeds a certain threshold, cholesterol binds to SCAP, and this induces the SCAP/SREBP complex to bind to specific ER retention proteins, insulin-induced gene (Insig) 1/2. The SREBP/SCAP/Insig complex is retained in the ER, and the expression of SREBP target genes drop. The most important SREBP target gene from a clinical perspective is the LDL receptor gene [

18]. This is illustrated by the fact that the SREBP-dependent induction of LDL receptor mRNA and protein in the liver is responsible for the LDL-cholesterol lowering activity of the statin family of drugs [

19], the most prescribed cholesterol-lowering drug globally. SREBP1c expression and activation are induced in response to insulin signaling [

20,

21].

Transcriptionally active SREBP1/2 molecules are unstable and degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in a phosphorylation-dependent manner [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Interestingly, the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of nuclear SREBP1/2 is negatively regulated by insulin signaling. We have proposed that the rapid degradation of transcriptionally active SREBP1/2 is part of a negative feedback loop that forces cells to re-sense their intracellular (cholesterol) and/or extracellular (insulin) environment before activating additional precursor proteins [

26].

The mRNA expression of SREBP1a and SREBP1c are induced during white adipogenesis

in vitro [

27,

28,

29]. The levels of SREBP1c mRNA and SREBP1 protein are also high in white adipose tissue (WAT). It has been shown that SREBP1c promotes/supports white adipogenesis

in vitro. This involves the SREBP-dependent activation of the PPARγ and fatty acid synthase genes, with the latter driving fatty acid synthesis and thereby the generation of PPARγ ligands/activators [

28,

30]. However, whether SREBP1c has a similar role in white adipogenesis

in vivo is unclear [

31]. Nevertheless, it is well established that SREBP1c plays important roles in maintaining lipid metabolism in mature WAT

in vivo, and that the activation of SREBP1c in this tissue can be modulated in obesity [

27,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

The functional role of SREBP1/2 in brown adipocytes has not been explored extensively. However, it has been reported that the expression and activation of SREBP1c are increased in BAT in response to chronic cold exposure [

37]. As a result, the expression of SREBP1c target genes involved in fatty acid synthesis was also induced under these conditions. Importantly, inactivating SREBP1/2 in BAT reduced the thermogenic capacity of mice in response to chronic cold. The authors concluded that SREBP1c-dependent fatty acid synthesis is induced in BAT to supply fatty acids to meet the increased demand for fatty acid β-oxidation and heat generation in response to long-term cold exposure, suggesting that SREBP1c has a functional role in mature brown adipocytes.

White adipocytes are characterized by the accumulation of a single triglyceride-rich lipid droplet that takes up most of the intracellular space. The triglycerides in this droplet are hydrolyzed during fasting, and the fatty acids enter the circulation to provide energy for other cells and tissues. Brown adipocytes contain several smaller lipid droplets and are characterized by their high mitochondrial content. The lipid droplets found in brown adipocytes are also hydrolyzed and the liberated fatty acids are transported to mitochondria and are converted to acetyl-CoA through β-oxidation. The acetyl-CoA feeds into the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain (ETC). Brown adipocytes express a specific uncoupling protein, UCP1, which dissipates the proton gradient created by the ETC in a manner independent of ATP synthesis. Instead, the energy contained in the gradient is converted to heat. Although white and brown adipocytes share many characteristics, their developmental origins are distinct [

38,

39]. Despite this, white and brown adipogenesis share many regulatory proteins, including PPARγ and members of the C/EBP family of transcription factors. A third cell type, known as beige adipocytes, is found within WAT and can adopt a more brown phenotype in response to various external signals, such as cold, exercise, and beta-adrenergic agonists [

40,

41]. This process, known as WAT browning, enhances thermogenic capacity and increases organismal energy consumption.

The transcription factor PPARγ is known as a master regulator of white adipogenesis [

42,

43]. The differentiation of white progenitor cells (preadipocytes) is a transcriptional cascade involving PPARγ and members of the C/EBP family of transcription factors. Together, PPARγ and C/EBPα/β/δ, activate the expression of multiple genes involved in adipocyte differentiation, including additional transcription factors and genes involved in lipid synthesis, and lipid and glucose uptake. This process is activated in response to insulin signaling and fully mature adipocytes are very insulin responsive [

44,

45]. PRDI-BF1 and RIZ homology domain containing 16 (PRDM16) is a transcriptional coregulator that promotes the expression of brown/beige-specific genes and suppresses myocyte- and WAT-specific genes [

46,

47,

48]. PRDM16 accomplishes this by interacting with other transcriptional regulators. The most important of these include PPARγ, C/EBPβ, PGC1α, CtBP1/2 and EHMT1 [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. The expression of PRDM16 and C/EBPβ is sufficient to drive brown adipogenesis in fibroblasts and myoblasts, and the activation of PGC1α and PPARα is important for mitochondrial biogenesis and for establishing the thermogenic program. Notably, PRDM16 function in WAT appears critical for overall thermogenic potential and energy expenditure [

41,

51]. This was elegantly illustrated using a mouse model in which PRDM16 was inactivated after the brown fat/muscle fate decision was established [

40]. Although these mice presented no obvious BAT phenotype, they displayed a dramatic reduction in WAT browning, most likely linked to blunted beige adipogenesis and/or function. The PRDM16-deficient animals developed obesity earlier than control animals in response to high-fat feeding and displayed severe insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis, even before any obvious weight gain [

40]. Thus, PRDM16, beige adipocytes, and the browning of WAT are critical for whole-body metabolic health by promoting thermogenesis and energy consumption.

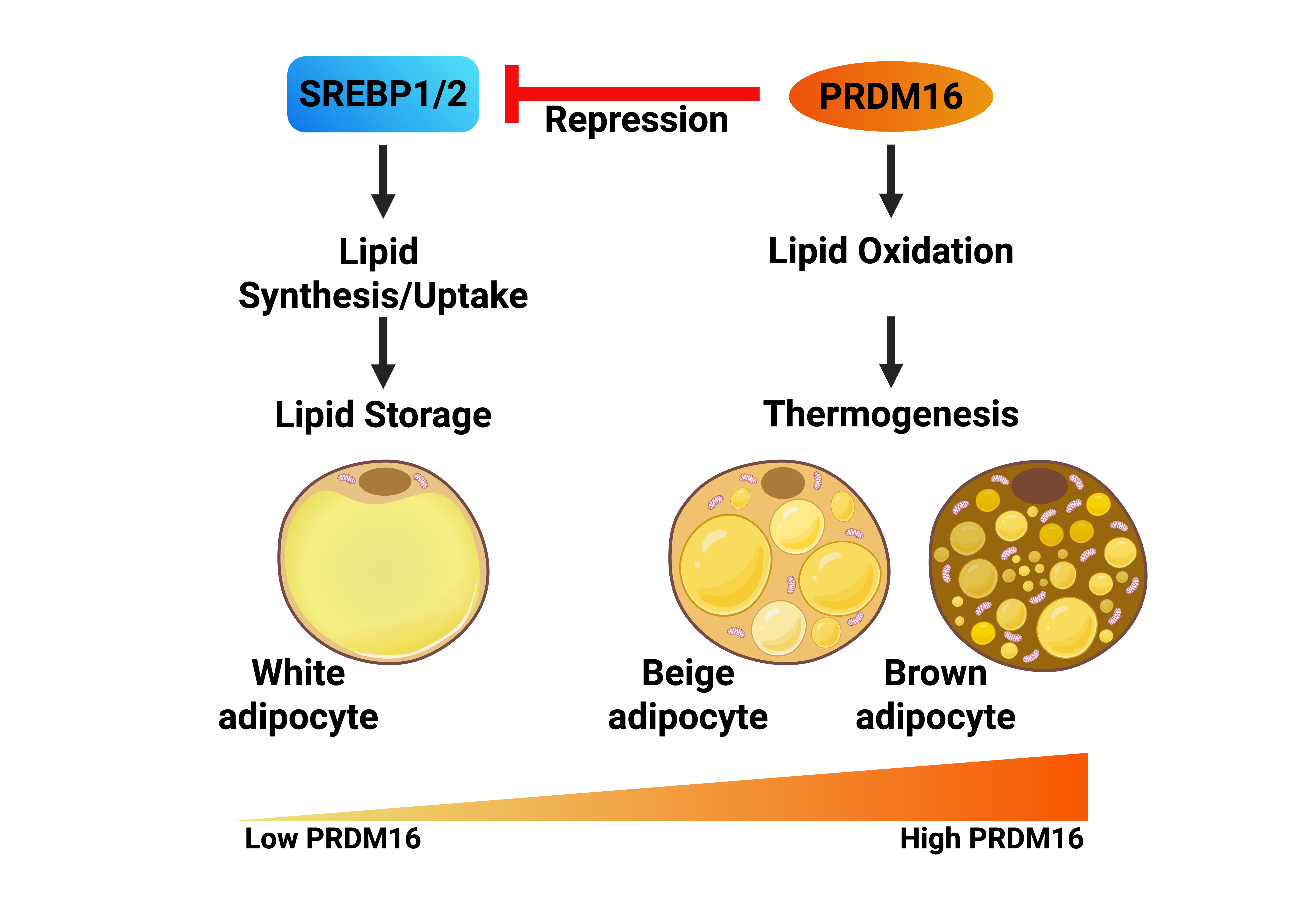

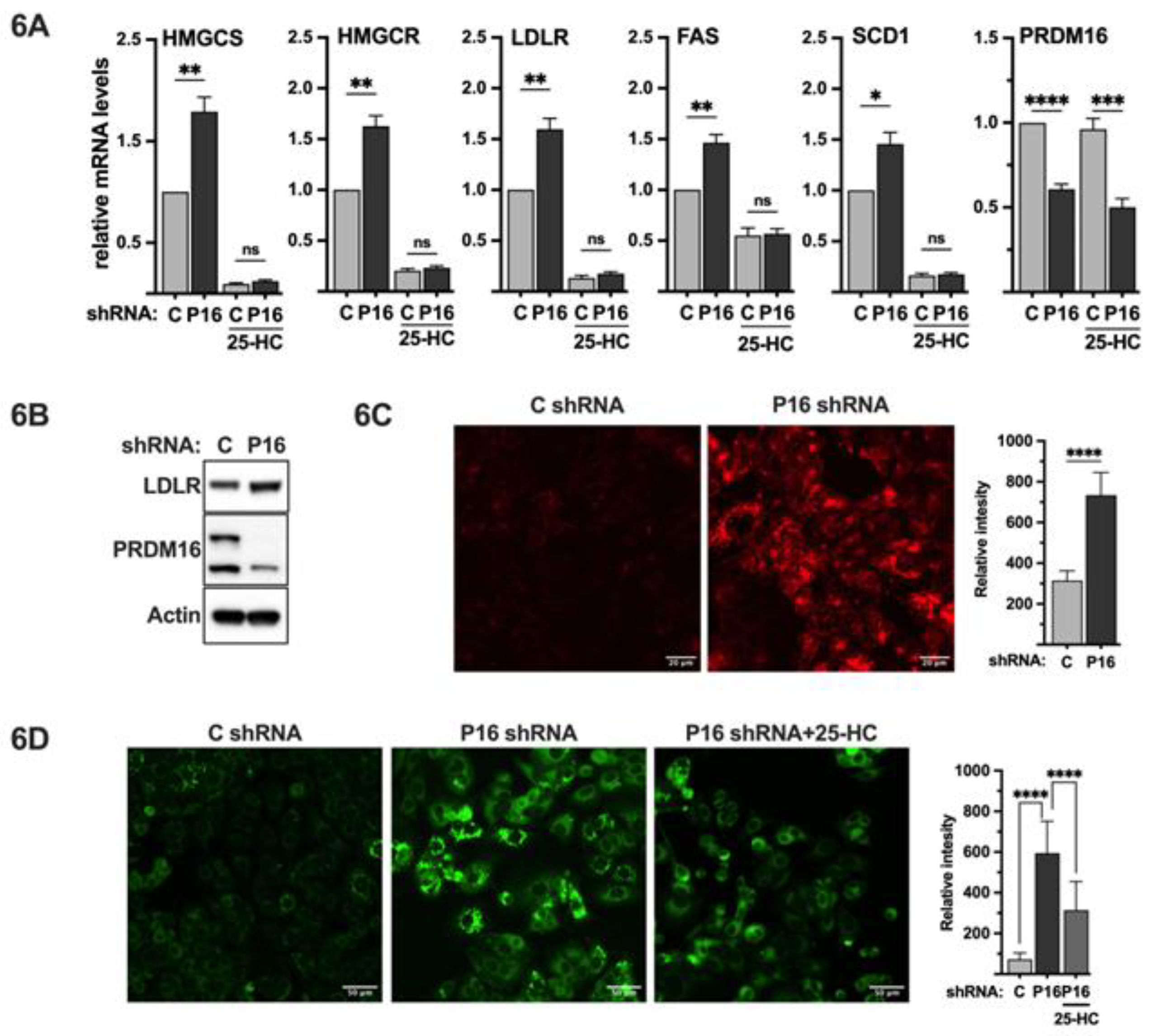

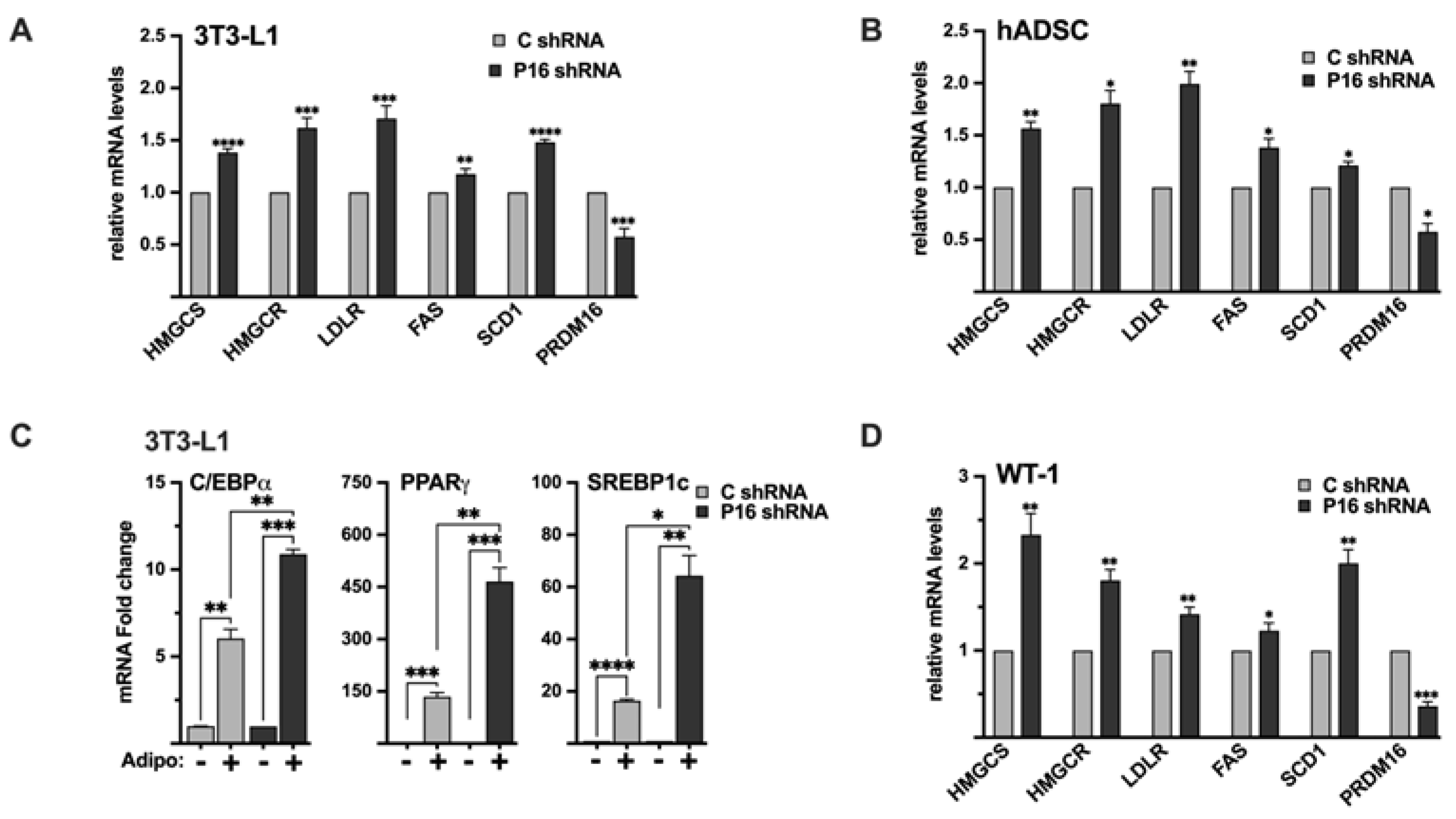

In this investigation, we set out to explore if there was any functional interaction(s) between SREBP1/2 and PRDM16. We demonstrate that PRDM16, the master regulator of brown adipogenesis, physically interacts with nuclear SREBP1/2. Using loss- and gain-of-function assays, we demonstrate that PRDM16 inhibits the transcriptional activities of SREBP1/2. As a result, inactivation of PRDM16 activates the expression of SREBP target genes involved in lipid synthesis and metabolism, resulting in the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets. Importantly, we demonstrate that the functional interaction between PRDM16 and SREBP1/2 extend to progenitors of both white and brown adipocytes, suggesting that this regulatory axis could affect adipocyte differentiation and/or function.

3. Discussion

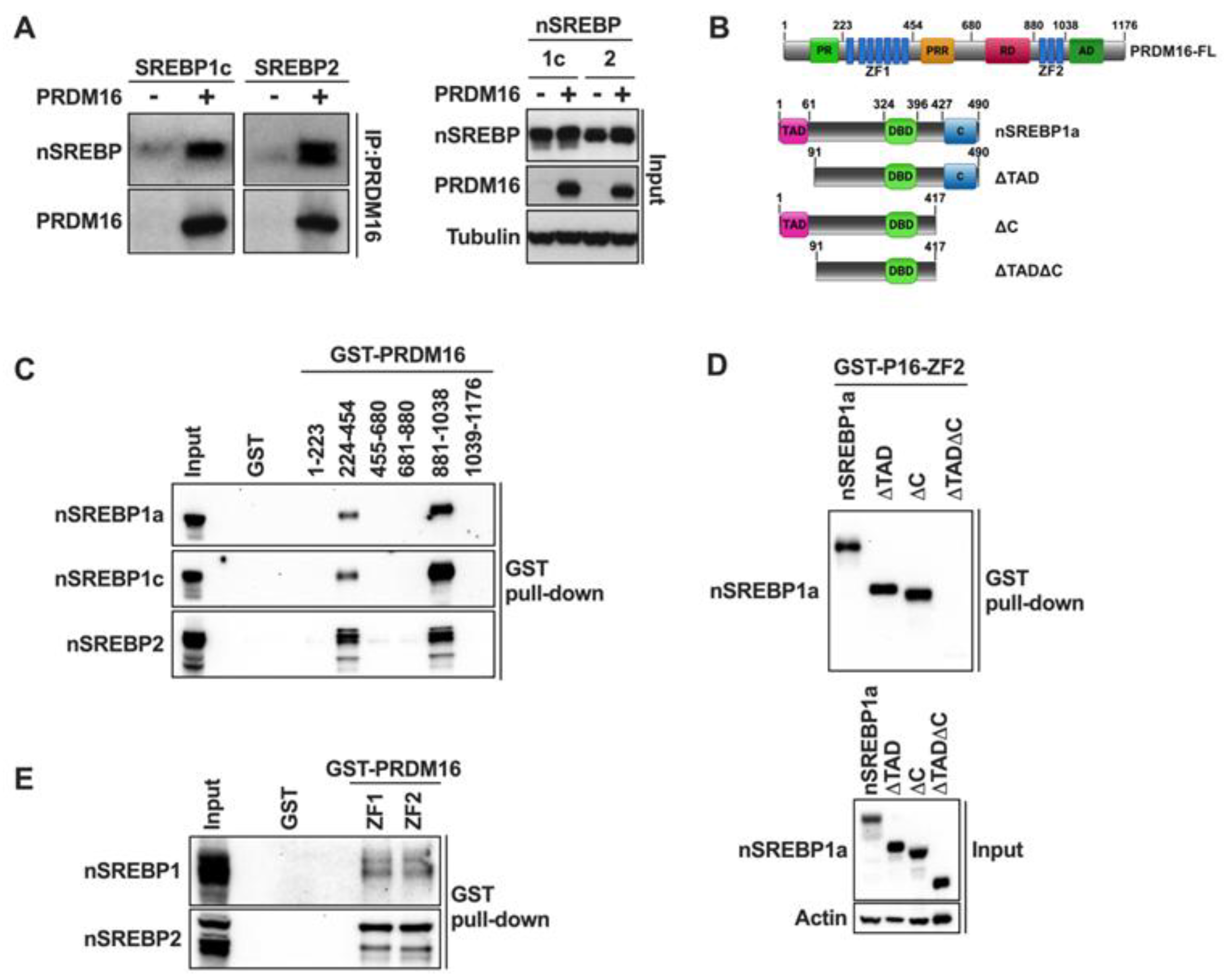

In the current manuscript, we demonstrate that PRDM16 interacts with the nuclear forms of all members of the SREBP family of transcription factors. The SREBPs interact with both zinc finger domains (ZFs) of PRDM16. These interaction domains are shared with many other transcriptional regulators that have been found to interact with PRDM16, e.g., C/EBPβ, PGC1α, MED1, and EHMT1 [

48,

49,

53,

54]. Both the N- and C-terminus of nuclear SREBP1 were required for its interaction with the ZFs in PRDM16, while deleting either domain individually had no effect on the interaction. This could indicate that SREBP1/2 and PRDM16 form multimeric complexes Another possibility is that the deletion of both the N- and C-terminus in nuclear SREBP1 affects its structure, thereby disrupting the SREBP-PRDM16 interaction. A third possibility is that the dual interaction domains in SREBP1/2 and PRDM16 are required to form stable complexes

in vivo, something that may not have been captured in our

in vitro protein-protein interaction assays. The latter possibility could be addressed using sensitive in-cell protein-protein interaction techniques, such as bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays. Although we believe that this is the first report of a direct interaction between SREBP1/2 and PRDM16, the nuclear forms of both SREBP1 and SREBP2 were identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for PRDM3-interacting proteins [

55]. PRDM3, also known as MECOM and EVI1, displays high homology with PRDM16 with a similar domain structure [

56]. Importantly, it has been shown that PRDM3 contributes to brown adipogenesis and maintenance, especially in the absence of PRDM16 [

52]. Thus, nuclear SREBP1/2 may interact with two PRDM proteins important for BAT formation and function. Exploring the functional interaction between SREBP1/2 and PRDM3 could broaden our understanding of the crosstalk between the SREBP and PRDM families of proteins.

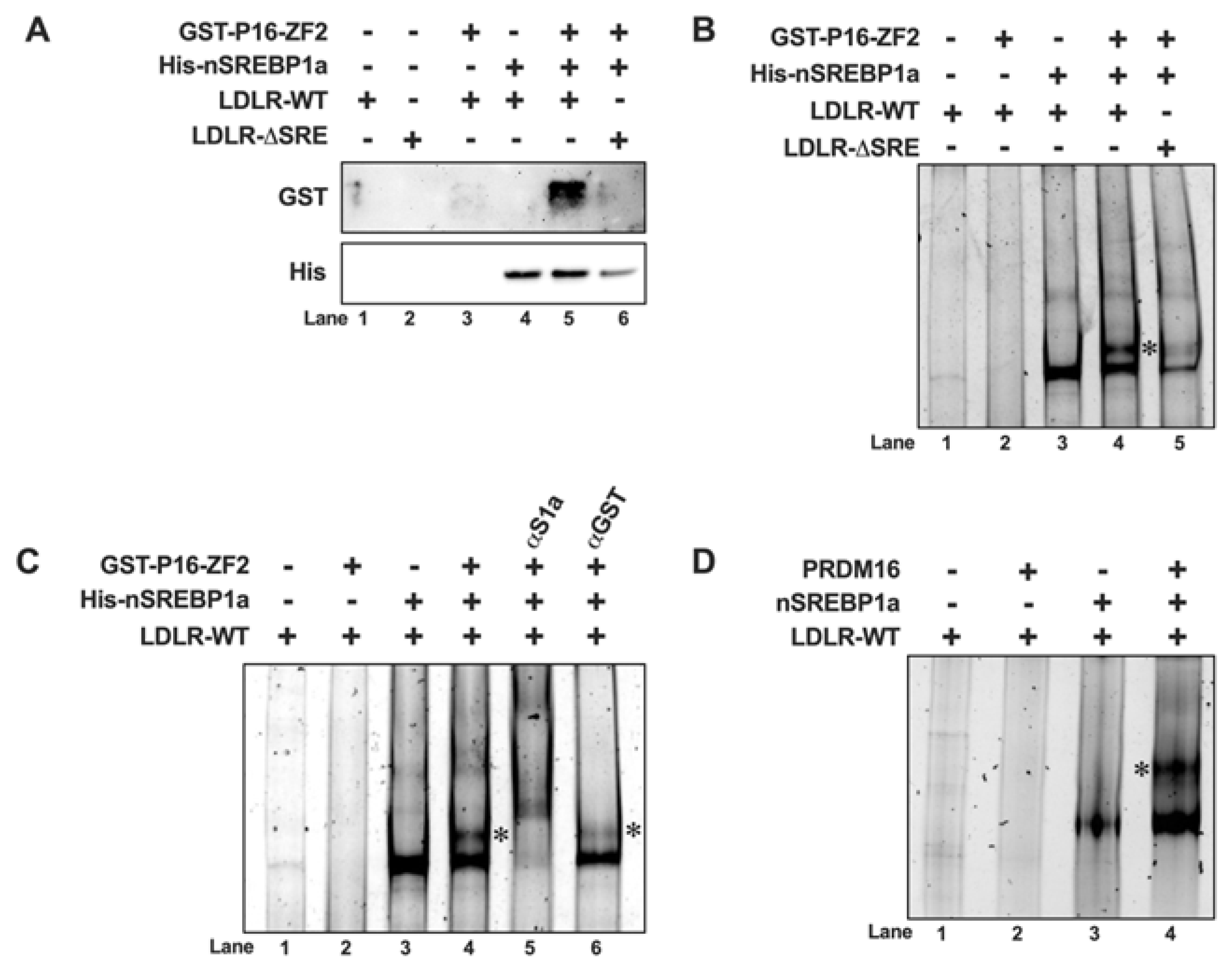

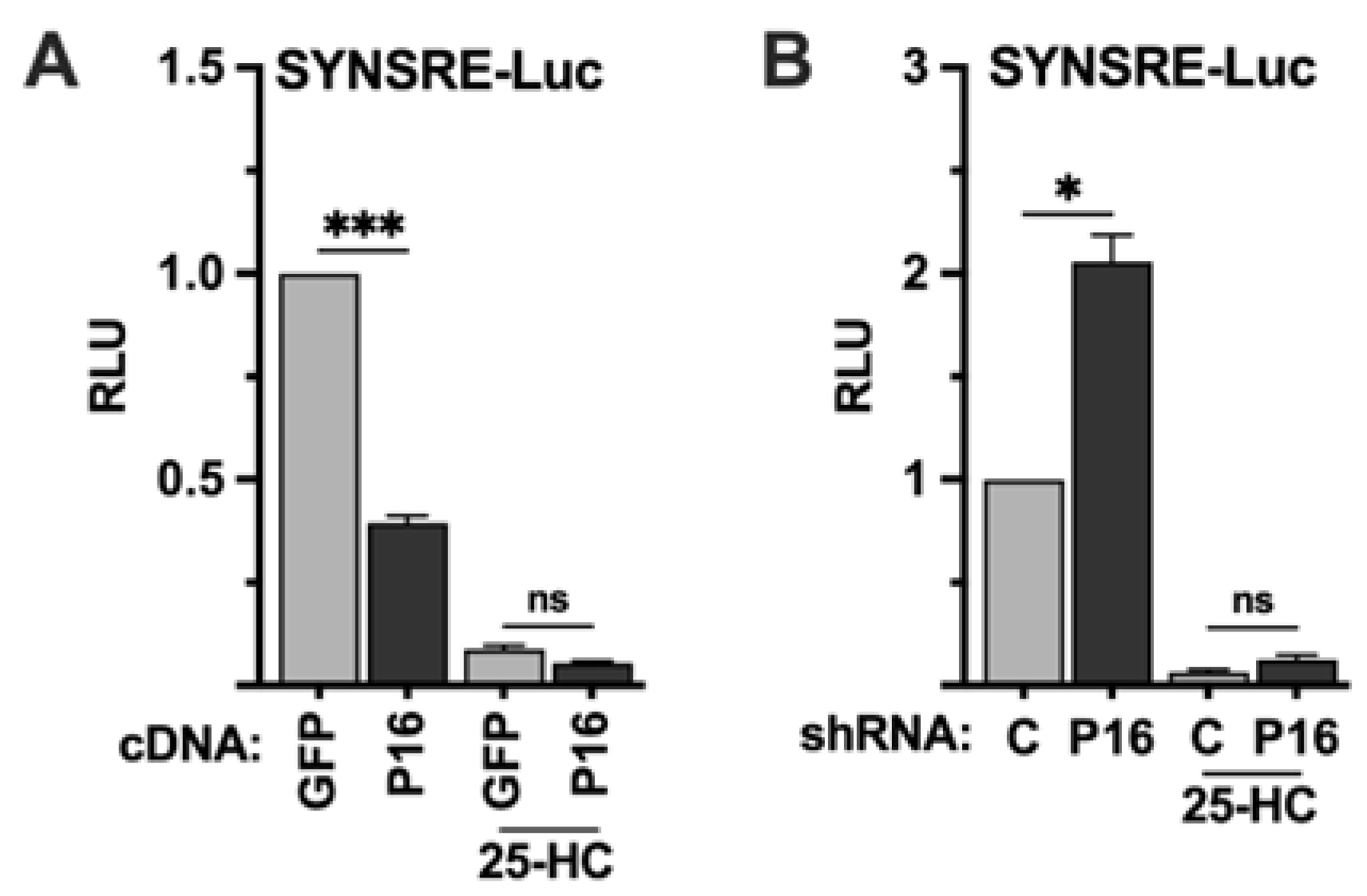

SREBP1/2 are synthesized as membrane bound precursor proteins that need to be cleaved in order to generate the transcriptional active forms of the proteins. In our experiments, PRDM16 behaved as a transcriptional repressor of nuclear SREBP1/2. This is illustrated by our observation that PRDM16 was able to repress the transcriptional activities of ectopically expressed nuclear SREBP1/2, and that PRDM16 failed to affect the expression of SREBP target genes in cells treated with 25-hydroxycholesterol, a potent inhibitor of SREBP1/2 activation. It will be important to identify the mechanism(s) involved in the PRDM16-mediated regulation of nuclear SREBP1/2. One possibility is that PRDM16 blocks the DNA binding of SREBP1/2. However, this is an unlikely scenario for several reasons. First, PRDM16 was able to repress the transcriptional activities of SREBP1/2 fused to the DNA binding domain of Gal4 in promoter-reporter assays that were independent of the intrinsic DNA binding activities of SREBP1/2. Secondly, we were unable to observe any effect of PRDM16 on the DNA binding of SREBP1 in our DNA binding assays. Rather, these assays suggested that PRDM16 is recruited to SREBP target promoters though its interaction with SREBP1/2. The physical and functional interactions between endogenous PRDM16 and nuclear SREBP1/2 on SREBP target promoters needs to be further explored using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. A more likely possibility is that PRDM16-interacting transcriptional co-repressors are recruited to SREBP1/2 target genes as a result of the SREBP-PRDM16 interaction. Of the repressors interacting with PRDM16, CtBP1/2 are of special interest. First, CtBP1/2 does not interact with the ZFs of PRDM16 [

50], suggesting that PRDM16 could interact with CtBP1/2 and SREBP1/2 simultaneously. Importantly, CtBP2 has been found to regulate the transcriptional activities of nuclear SREBP1/2, possibly in a cell type-specific manner [

57,

58]. CtBP2 was found to activate the expression of SREBP target genes in glioblastoma cells, while it repressed the expression of the same set of genes in liver cells. Interestingly, CtBP1/2 have been found to bind and be controlled by NADH and fatty acids [

58]. Thus, it would be interesting to explore the potential role of CtBP1/2 in the PRDM16-mediated repression of SREBP1/2. This possibility could be addressed by analyzing the recruitment of CtBP1/2 to SREBP target promoters

in vivo in response to either loss or gain of PRDM16.

In fact, nuclear SREBP1/2 and PRDM16 share several interaction partners and/or regulators, including CtBP1/2, PGC1α/β, SirT1, MED1, LSD1, and C/EBPβ, suggesting that the two proteins could compete for a limited amount of these factors. The Mediator complex is a multi-protein complex that has been shown to regulate many transcription factors. Through their N-terminal transactivation domains, SREBP1/2 have been found to interact with several components of this complex, including MED14, MED15 and MED1 [

27,

59,

60]. PRDM16 has also been shown to interact with MED1, and this interaction is important for the PRDM16-mediated control of BAT function [

53,

54]. Members of the C/EBP family of transcription factors play well-documented roles during adipogenesis, both white and brown/beige. C/EBPβ is involved in the expression of PRDM16 in brown adipocytes. In addition, it interacts with PRDM16 and to enhance the expression of PGC1α, thereby promoting mitochondrial biogenesis/function and the establishment of the thermogenic program. C/EBPβ is also an important regulator of SREBP1c expression and function, both in liver and during white adipogenesis [

61,

62]. In liver, C/EBPβ controls the insulin-dependent induction of SREBP1c mRNA [

61]. Since both SREBP1/2 and C/EBPβ interact with the two ZFs in PRDM16, one possibility could be that PRDM16 represses the expression of SREBP1c by sequestering C/EBPβ, thereby reducing the expression of SREBP target genes. Alternatively, the C/EBPβ-PRDM16 complex could be recruited to the SREBP1c promoter and repress SREBP1c mRNA expression. However, although very plausible, none of these options would require a direct interaction between SREBP1/2 and PRDM16. In addition, it would not explain how PRDM16 is able to repress the transcriptional activities of ectopically expressed nuclear SREBP1/2. Regardless, further studies of the functional interactions between PRDM16, SREBP1/2 and C/EBPβ are clearly warranted, especially in adipocytes.

PRDM16 possess intrinsic methyltransferase activity and has been found to methylate lysine 9 in histone H3 (H3K9) [

56,

63]. H3K9 methylation is a repressive epigenetic mark associated with gene silencing and/or heterochromatin. In addition, PRDM16 has been found to interact with other proteins that either add (EHMT1) or remove (LSD1) methyl groups from histones [

49,

64]. Thus, it is possible that PRDM16 could control the expression of SREBP target genes by controlling epigenetic histone modifications, including methylation, at the corresponding promoters. This could be explored using modification-specific histone antibodies in ChIP experiments.

SREBP1c has been shown to support white adipogenesis

in vitro and PRDM16 is a master regulator of brown and beige adipogenesis and function. The role of PRDM16 in the browning of WAT in response to external signals is of great clinical importance. This is exemplified by the observation that the inactivation of PRDM16 in WAT and BAT resulted in the development of obesity, severe insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis, and the investigators demonstrated that these phenotypes linked to a dramatic reduction in the browning of WAT, and thereby a significant reduction in energy expenditure [

40]. We have demonstrated that PRDM16 is a repressor of SREBP1/2 in preadipocytes, and that the overexpression of PRDM16 blocks the adipogenesis and expression of SREBP target genes in 3T3-L1 cells. We have also demonstrated that the inactivation of PRDM16 enhances the expression of SREBP target genes in white and brown preadipocyte cell lines, as well as in adipose-derived human stem cells. Importantly, the expression of adipogenic marker genes was enhanced in mature adipocytes generated from PRDM16 knockdown 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Based on our data, we propose that the PRDM16-dependent repression of SREBP1/2 could be especially important in brown/beige (pre)adipocytes and/or during the browning of WAT. This hypothesis is supported by the phenotype of transgenic mice expressing the nuclear forms of either SREBP1a or SREBP1c in adipose tissue [

65,

66]. Although the effects on WAT were different in these two transgenic lines, brown adipocytes in both models resembled white adipocytes and expressed high levels of classical SREBP target genes and accumulated very high levels of lipids. Importantly, the expression of UCP1, a classical BAT marker, was drastically reduced in BAT isolated from both transgenic models. Thus, the PRDM16-mediated repression of SREBP1/2 may be important to prevent lipid overload in brown/beige (pre)adipocytes and ensure that they maintain their thermogenic identity. Recent work has shown that the SREBP1c-dependent activation of fatty acid synthesis is essential to sustain BAT thermogenesis during chronic cold [

37]. A similar observation was made in beige adipocytes using singe-cell transcriptomics of adipose tissue from young and aged mice exposed to chronic cold [

67]. The expression of both SREBP1c and its target genes involved in fatty acid synthesis was increased in beige adipocytes isolated from young mice exposed to chronic cold. Interestingly, the cold-induced beige adipogenesis and the expression of SREBP1c and its target genes were blunted in aged mice [

67], suggesting that beige adipogenesis could be dependent on the reprograming of lipid metabolism. The dynamic relationship between lipid synthesis and utilization in beige and brown adipocytes may provide these fat depots with the plasticity needed to respond to metabolic/energy stress. Importantly, it suggests that this plasticity could be lost with increasing age, a condition associated with increased risk of developing metabolic disease. Thus, the functional link between PRDM16 and SREBP1/2 in adipose tissue warrants further exploration

in vivo.

Based on the results reported in this manuscript, we suggest that the PRDM16-mediated repression of nuclear SREBP1/2 represents a novel mechanism to regulate lipid synthesis and metabolism. We propose that the functional interactions between these transcriptional regulators could impact adipose biology, both WAT and BAT. The SREBP2-LDL receptor axis is already a well-established target for cholesterol-lowering therapeutics in cardiovascular disease, and PRDM16 is a very attractive target for obesity and T2D. However, PRDM16 regulates other important biological processes beyond adipogenesis, including in the brain, intestine and cancer. Thus, the different interactions involving PRDM16 has emerged as potential targets in metabolic disease. It will be interesting to see if the PRDM16-SREBP1/2 axis is a valid therapeutic target in metabolic disease.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Treatments

MCF7 (HTB-22), HepG2-C3A (CRL-10741), HEK293 (CRL-1573), and 3T3-L1 (MBX.CRL-3242) cells were obtained from American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC), and human adipose-derived stem cells were obtained from ThermoFisher (R7788110) and were cultivated in MesenPRO RS medium (12746012). WT-1 mouse brown preadipocytes cells (SCC255) were obtained from MilliporeSigma. All other cell culture media, supplements and reagents were from Gibco. HepG2-C3A cells were cultured in MEM media supplemented with 10% FBS, non-essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, Glutamax and antibiotic-antimycotic, and MCF7, HEK293, and 3T3-L1 cells were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS in addition to the supplements mentioned above. Where indicated, HepG2 and MCF7 cells were grown in media in which FBS was replaced by lipoprotein-deficient sera (Sigma-Aldridge) to promote activation of SREBP1/2.

4.2. Adipocyte Differentiation

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were allowed to reach confluency at which point the media was changed. Forty-eight hours after reaching confluency, the media was changed to adipocyte differentiation media, which was composed of regular growth media supplemented with 0.5 mM isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1 μM dexamethasone, and 4 μg/ml human insulin. Cells were left in differentiation media for 48 hours, after which the media was changed to regular media supplemented with insulin (4 μg/ml). The experiments were stopped 7 days after the addition of differentiation media. For the differentiation of WT-1, cells were incubated with an induction medium (DMEM high glucose, 2% FBS, 20 nM insulin, 1 nM triiodo-L-thyronine (T3), 0.125 mM indomethacin, 5 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) for 48 h, prepared fresh and sterile-filtered on the day of use. After 48 h, the induction medium was changed to differentiation medium (DMEM high glucose, 2% FBS, 20 nM insulin, 1 nM T3 and 1% penicillin/streptomycin). Differentiation medium was refreshed every other day, and the experiments were stopped 7 days post induction.

4.3. Plasmid DNA

The lentiviral shRNA constructs targeting human PRDM16 (RHS3979-201751161-TRCN0000020044, RHS3979-201751162-TRCN0000045, and RHS3979-201751163-TRCN0000046) were purchased from Horizon Discovery. The corresponding constructs targeting mouse PRDM16 (VB900137-6002rva and VB900137-6003bzy) and the lentiviral expression vector for human PRDM16 (NM-022114-4; VB900131-6471kkm) were purchased from VectorBuilder. pCaggs PRDM16-F/H was kindly provided by Thomas Jenuwein [

56]. GST-PRDM16-1-223 (#53346), GST-PRDM16-224-454 (#53347), GST-PRDM16-455-680 (# 53348), GST-PRDM16-681-880 (#53349), GST-PRDM16-880-1038 (# 53350), and GST-PRDM16-1039-1176 (#53351) constructs were kindly provided by Bruce Spiegelman [

50]. pGL2-SYNSRE-luciferase (#60444) and of pGL2-SYNSREΔSRE-luciferase (#60490) promoter-reporter constructs were kindly provided by Timothy Osborne [

68]. pGL4-LDLR-luciferase, pGL4-LDLRΔSRE-luciferase, pGL4-FAS-luciferase, and pGL3-G1E1B-luciferase have been described previously [

25,

69,

70]. The expression vectors for FLAG and MYC-tagged nSREBP1s (1a, 1c, and 2) and the deletion mutants of FLAG-nSREBP1a (FLAG-SREBP1a-ΔTAD (amino acids residues 90–490), FLAG-SREBP1a-ΔC (amino acid residues 2–417), and FLAG-SREBP1aΔTADΔC have been described previously [

69,

71]. The Gal-4 DNA binding domain (amino acid residues 1–147) cloned into pcDNA3 was used to develop Gal4-SREBP1/2 (1a, 1c, or 2) and Gal4-TAD (1a, 1c, or 2) as described previously [

72,

73].

4.4. Lentivirus Production and Transduction

HEK293 cells grown in 10 cm dishes were used to produce all lentiviruses. Twelve μg of lentiviral DNA was co-transfected with 15 μl Trans-Lentiviral shRNA Packaging Kit (Horizon Discovery, TLP5912) by the calcium phosphate precipitation transfection method. Forty-eight hours after transfection, media was collected and filtered through 0.45 μm syringe filters and the viruses were stored in aliquots at -80°C. Target cells were transduced in regular media containing 8μg/ml polybrene for 16 hours, followed by 3 to 4 days of puromycin selection (2 μg/ml). The viruses expressing shRNA targeting human and mouse PRDM16 were produced and used as pools consisting of three and two shRNAs, respectively (see 4.3).

4.5. Antibodies and Reagents

Antibodies against PRDM16 (16212) and SCD1 (2438S) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against HMG-CoA synthase (sc-271543), SREBP1 (sc-8984 and sc-13551), GST (sc-138), Myc (sc-40), and HA (sc-805) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and the SREBP2 antibody (AF7119) was purchased from R&D Systems. Anti-FLAG (F3165) antibody was obtained from Sigma-Aldridge. The LDL receptor antibody (PA5-22976) was purchased from Invitrogen, and the β-actin antibody (A5441) was purchased from Sigma-Aldridge. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (G21234) and anti-mouse IgG (62-6520) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-goat IgG (HAF019) antibody was purchased from R&D Systems. Chemical were obtained from Sigma-Aldridge, unless otherwise indicated.

4.6. Cell lysis and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in buffer A (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaF, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% (w/v) Triton X-100, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 mM sodium butyrate, 1% aprotinin, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (DOC)) and cleared by centrifugation. SDS and DOC were omitted from the lysis buffer for protein-protein and protein-DNA interaction assays. Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE (4–12% Bis-Tris; Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Cytiva). Membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, probed with primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and visualized by chemiluminescence on an iBright CL1500 (Invitrogen).

4.7. Protein Purification

Cultures of E. coli (BL21) transformed with expression vectors for 6xHis-nSREBP1a or GST-PRDM16 were induced with IPTG (0.75 mM) and incubated overnight at room temperature with shaking to allow protein expression. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the cell pellets resuspended in 20 ml PBS (ice-cold) containing protease inhibitors (PMSF and aprotinin) and sonicated on ice. Following sonication, Triton-X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1% and the suspension was kept in an end-over-end mixer for 30 minutes at 4°C. The solubilized material was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected in new tubes. Clarified lysates were used to purify the His- and GST-tagged proteins using Ni-NTA (Millipore, P661) and glutathione Sepharose (Cytiva, 17-5132-01), respectively, employing standard protocols. The GST-tagged proteins were either retained on the glutathione beads for GST pulldown assays or eluted with an excess of glutathione for electromobility shift assays. The purified 6xHis-SREBP1a protein was eluted from the Ni-NTA beads with imidazole. All eluted proteins were dialyzed against PBS containing 20% glycerol and protease inhibitors (PMSF and aprotinin), aliquoted and stored at -80oC.

4.8. GST Pulldown and Co-Immunoprecipitation Assays

GST pulldown assays were performed using GST-tagged PRDM16 fragments as bait and Myc-tagged nuclear SREBP1/2 (nSREBP1a, nSREBP1c, nSREBP2) expressed in HEK293 cells as prey. HEK293 cells were transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation with plasmids encoding Myc-tagged nuclear SREBP1/2, either wild-type or the indicated deletion mutants. Cell lysates were prepared in buffer A without SDS and DOC and pre-cleared using glutathione beads. The pre-cleared lysates (125 µl per reaction) were incubated with immobilized GST-PRDM16 fragments on glutathione beads for 1 hour at 4 °C with rotation. Beads were collected by centrifugation, and washed three times in buffer A, once in 0.5M NaCl, followed by a final wash in buffer A. The pulled-down material and inputs were resolved by SDS–PAGE and processed for Western blotting. For co-immunoprecipitation assays, HEK293 cells were transfected with expression vectors for Myc-tagged nuclear SREBP1c or SREBP2 in the absence or presence of HA-tagged PRDM16. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared in buffer A without SDS and DOC, and pre-cleared with protein A agarose beads (Millipore, P9424). The pre-cleared lysates were mixed with anti-HA antibodies (1 μg) and placed on an end-over-end mixer for three hours at 4 °C, followed by the addition of protein A agarose beads. The protein A agarose beads were collected by centrifugation, and washed three times in buffer A, once in 0.5M NaCl, followed by a final wash in buffer A. The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and processed for Western blotting.

4.9. DNA Pulldown Assay

Biotin-labeled DNA probes corresponding to wild-type or the ΔSRE version of the LDL receptor promoter were generated by PCR using biotin-labeled primers and the appropriate pGL4-LDLR templates. The primer sequences were as follows, Biotin-CTA GCA AAA TAG GCT GTC CC and CTT TAT GTT TTT GGC GTC TTC CA. DNAP reactions (typically 100 µl) were assembled in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1 μg sheared salmon sperm DNA (non-competitive DNA), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 μg bovine serum albumin (BSA). Biotin-DNA probes (100 ng) were incubated with purified GST-PRDM16 fragments (ZF1, aa 224–454; or ZF2, aa 881–1038) in the absence or presence of 6xHis-SREBP1a at 4°C for 90 min. Finally, the DNA probes were captured with streptavidin magnetic beads (Pierce, 8816), washed four times with cold binding buffer, and eluted in Laemmli buffer. The captured proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted with anti-His and anti-GST antibodies.

4.10. Electromobility Shift Assays

Unlabeled DNA probes corresponding to wild-type or the ΔSRE version of the LDL receptor promoter were generated by PCR using the appropriate pGL4-LDLR templates. The primer sequences were as follows, CTA GCA AAA TAG GCT GTC CC and CTT TAT GTT TTT GGC GTC TTC CA. The 10x binding buffer contains 200 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 and 500 mM NaCl. The final reaction mixture contained 2 μl 10x binding buffer, 20% glycerol, 1 μg sheared salmon sperm DNA (non-competitive DNA), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 μg bovine serum albumin (BSA). GST-ZF1 or GST-ZF2 were incubated with 500 ng of DNA probe in the absence or presence of 6xHis-SREBP1a. Where indicated, anti-His or anti-GST antibodies (0.5 μg) were added to the reaction. In the experiment illustrated in

Figure 5D, the recombinant proteins were replaced with nuclear extracts from HEK293 cells transfected with either empty vector, nuclear SREBP1a or PRDM16. The reactions were separated on 4% polyacrylamide gels with 0.5x TBE buffer, stained with SYBR Safe, and visualized on an iBright CL1500 Imaging System (Invitrogen).

4.11. Luciferase and β-Galactosidase Assays

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated promoter-reporter genes in the absence or presence of the indicated expression and/or shRNA vectors. Luciferase activities were determined in duplicate samples as described by the manufacturer (Promega). Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLUs) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates.

4.12. RNA Extraction and qPCR

RNA was extracted using Thermo GeneJet RNA Purification Kit. cDNA was generated using Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit. For qPCR, PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix was used (Applied Biosystems), using cyclophilin, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), and RPLP0 as references. The human and mouse primer sequences used to amplify target genes are provided in

Table S1 and S2, respectively.

4.13. Oil Red O Staining

Oil Red O staining of lipids was performed using a well-established protocol. Briefly, cells were washed twice in PBS, fixed in 4% (v/v) formaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature. The fixed cells were washed three times with PBS and once with 60% isopropanol. The fixed cells were treated with freshly prepared and filtered Oil Red O staining solution in 60% isopropanol for 60 minutes, followed by extensive washes with water. The stained cells were left immersed in water until imaging.

4.14. LipidTox Staining of Neutral Lipids

LipidTOX Green (H34475) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Briefly, cells grown in 12-well plates were fixed in 3.5 % (v/v) formaldehyde and washed extensively with PBS. The stain was used at a 1:1000 dilution in PBS. Cells were stained for 2 hours and kept in PBS at 4oC until imaging. At least 5 random fields/well were captured on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX73) using identical settings and exposure times. Representative images are displayed in the panels. The fluorescence in each image was quantified in Fiji and corrected for cell numbers. The mean fluorescence intensities -/+ SD across all images within each experimental group are provided in the figures.

4.15. LDL Uptake Assays

The pHrodo Red-LDL (Invitrogen, L34356) is dimly fluorescent at neutral pH but becomes brightly fluorescent after endocytosis. The cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated in media containing lipoprotein-deficient sera for 16 hours. pHrodo Red-LDL was added to a final concentration of 8μg/ml and followed by a 4-hour incubation at 37oC in a cell culture incubator. The cells were washed twice with PBS containing BSA (0.3%), and the pHrodo Red LDL-stained cells were imaged in the rhodamine red channel using appropriate filter sets. At least 5 random fields/well were captured on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX73) using identical settings and exposure times. Representative images are displayed in the panels. The fluorescence in each image was quantified in Fiji and corrected for cell numbers. The mean fluorescence intensities -/+ SD across all images within each experimental group are provided in the figures.

4.16. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software). For comparisons involving more than two groups, Welch’s ANOVA was used. For comparisons between two groups, Welch’s t-test was used. Data are presented as mean -/+ SEM, unless otherwise indicated. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

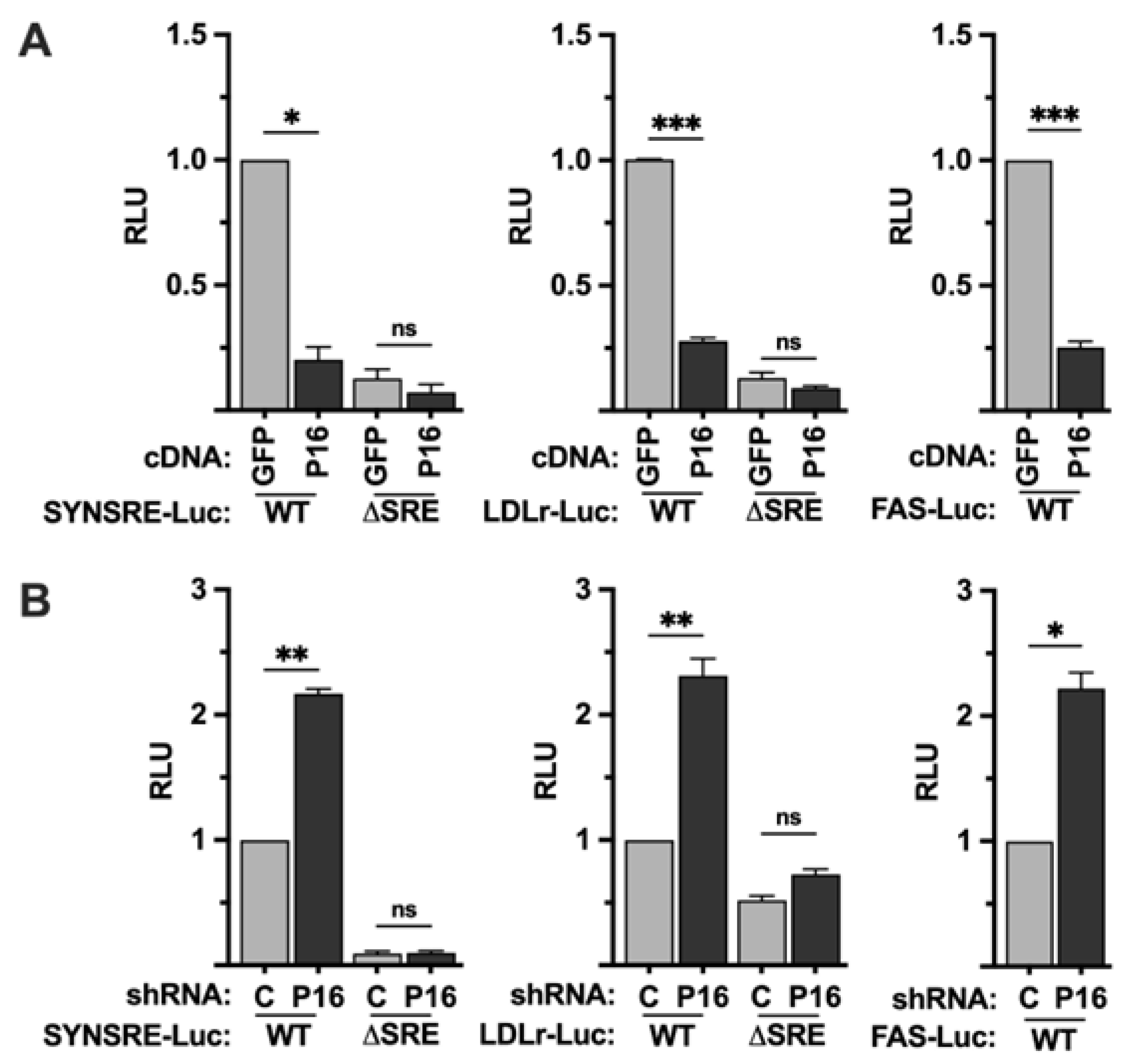

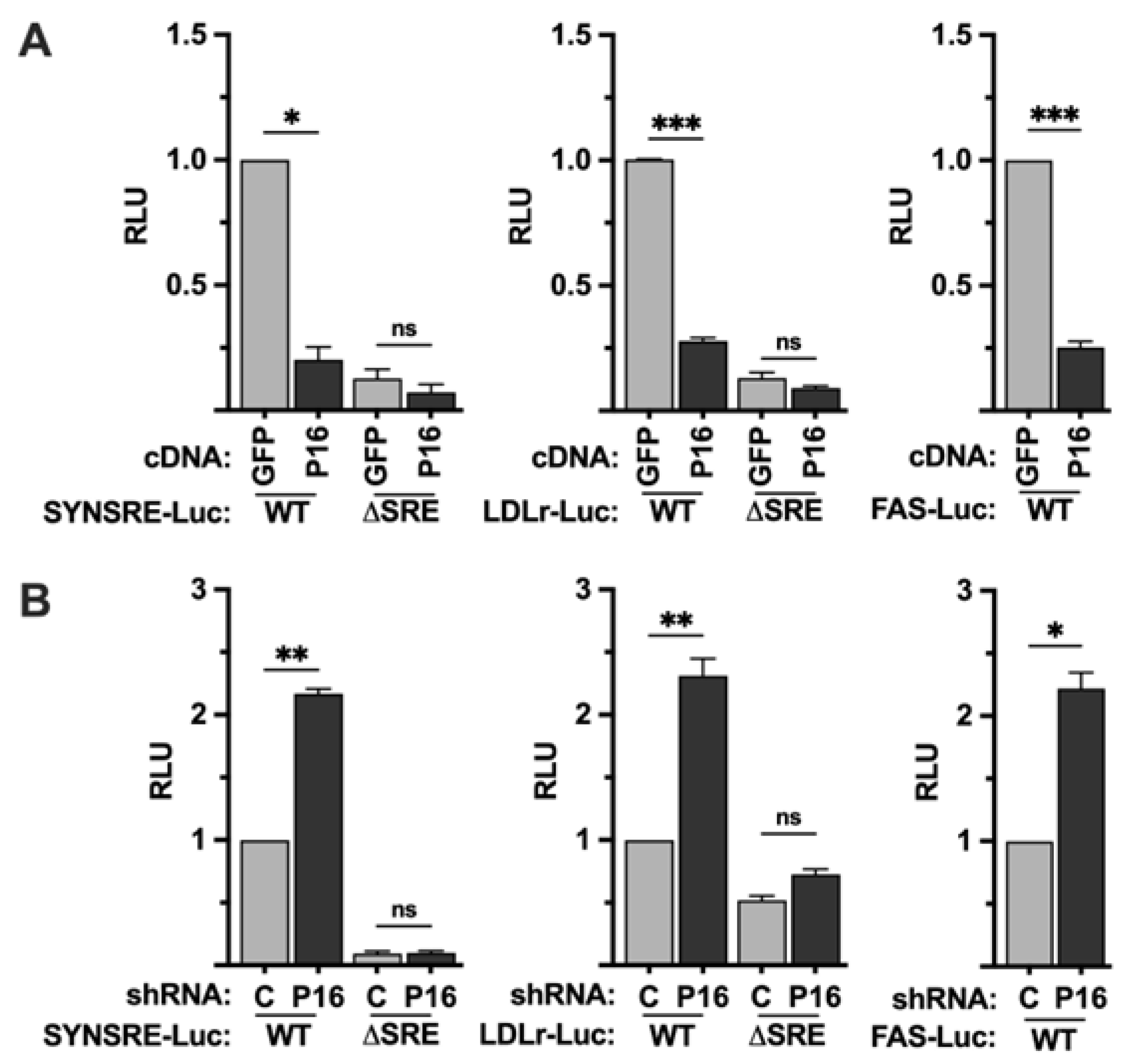

Figure 1.

PRDM16 represses SREBP target gene promoters. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with HMG-CoA synthase (SYNSRE), LDL receptor (LDLR) or fatty acid synthase (FAS) promoter-luciferase constructs together with either GFP or PRDM16 cDNA. In the case of HMG-CoA synthase and the LDL receptor promoter-reporter constructs, two constructs were used, either wild-type (WT) or a version in which the SREBP binding site was deleted (ΔSRE). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with the promoter-reporter constructs mentioned in (A) together with non-targeted (C) or PRDM16 (P16) shRNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLU) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The RLU of WT promoter-reporter constructs transfected with either GFP or non-targeted shRNA were set to 1. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

Figure 1.

PRDM16 represses SREBP target gene promoters. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with HMG-CoA synthase (SYNSRE), LDL receptor (LDLR) or fatty acid synthase (FAS) promoter-luciferase constructs together with either GFP or PRDM16 cDNA. In the case of HMG-CoA synthase and the LDL receptor promoter-reporter constructs, two constructs were used, either wild-type (WT) or a version in which the SREBP binding site was deleted (ΔSRE). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with the promoter-reporter constructs mentioned in (A) together with non-targeted (C) or PRDM16 (P16) shRNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLU) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The RLU of WT promoter-reporter constructs transfected with either GFP or non-targeted shRNA were set to 1. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

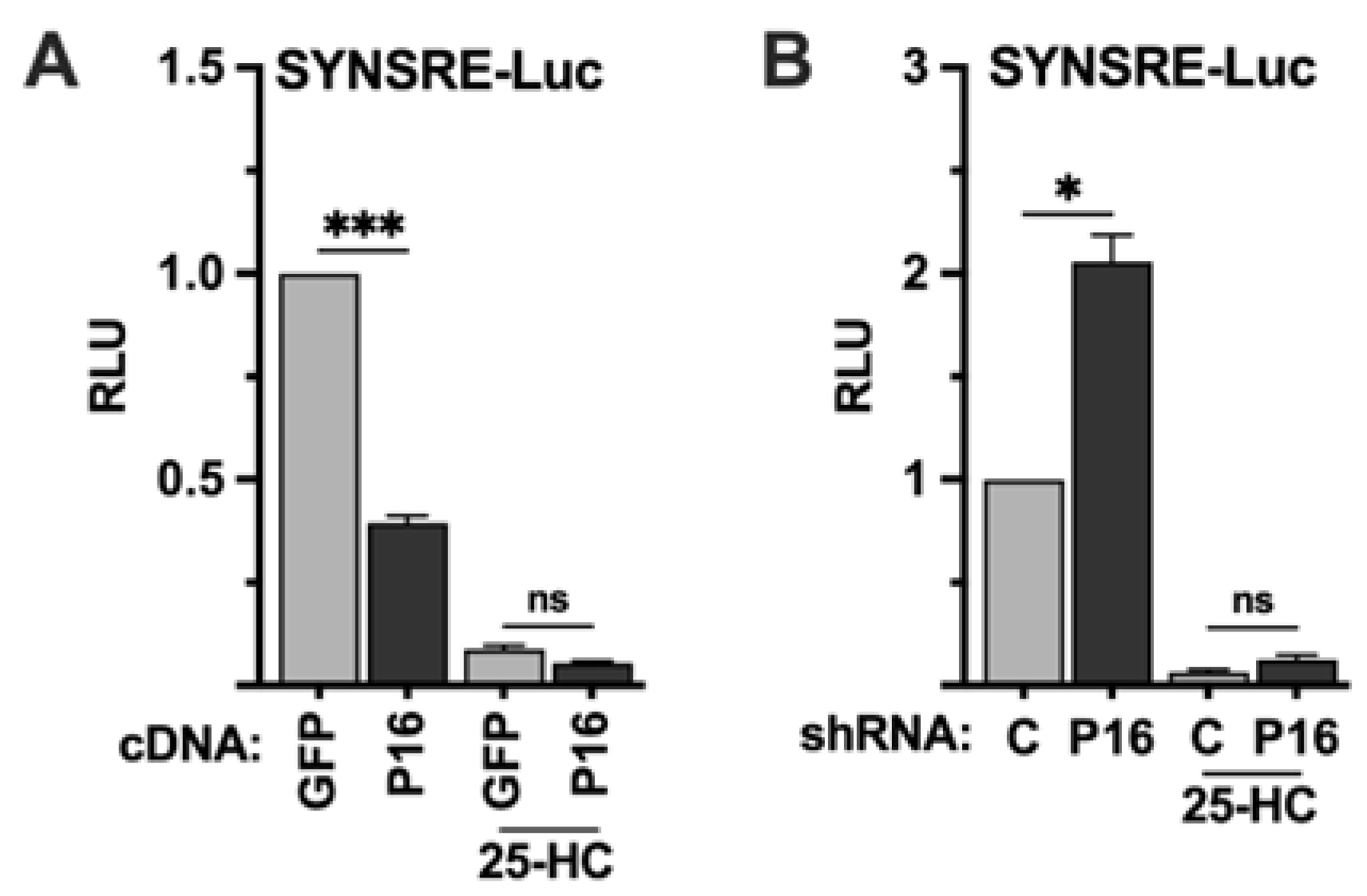

Figure 2.

The PRDM16-mediated repression of SREBP target promoters is dependent on SREBP1/2 activation. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with GFP or PRDM16 (P16) cDNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were placed in lipoprotein-deficient media. Where indicated, media was supplemented with 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC) to block SREBP1/2 activation. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with non-targeted (C) or PRDM16 (P16) shRNA and treated as in (A). Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLU) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The RLU of WT promoter-reporter constructs transfected with either GFP or non-targeted shRNA were set to 1. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

The PRDM16-mediated repression of SREBP target promoters is dependent on SREBP1/2 activation. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with GFP or PRDM16 (P16) cDNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were placed in lipoprotein-deficient media. Where indicated, media was supplemented with 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC) to block SREBP1/2 activation. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with non-targeted (C) or PRDM16 (P16) shRNA and treated as in (A). Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLU) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The RLU of WT promoter-reporter constructs transfected with either GFP or non-targeted shRNA were set to 1. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

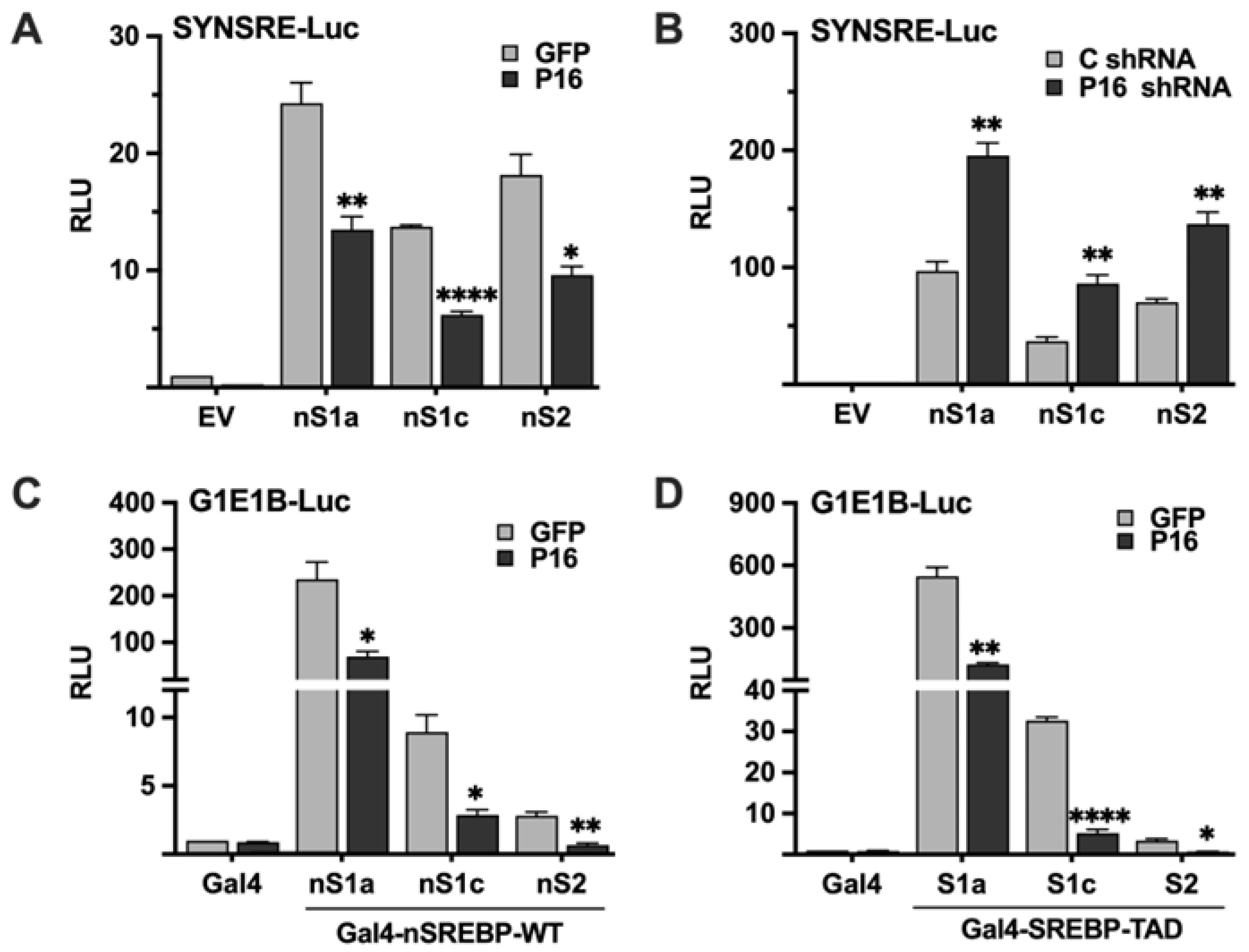

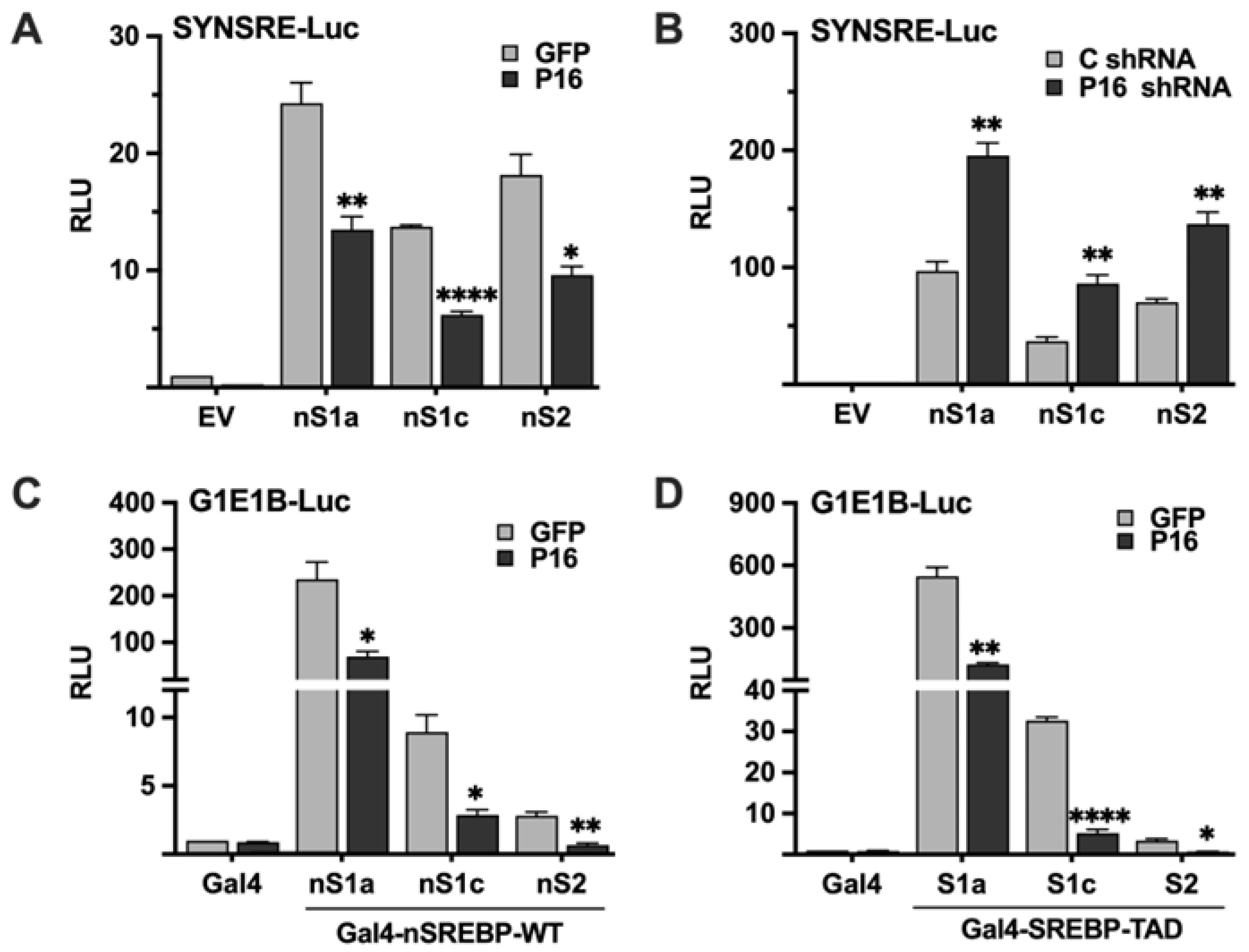

Figure 3.

PRDM16 targets the nuclear forms of SREBP1a, SREBP1c, and SREBP2. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with GFP or PRDM16 (P16) cDNA in the absence (EV) or presence of cDNA encoding the nuclear forms of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c) or SREBP2 (nS2). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with non-targeted (C) or PRDM16 (P16) shRNA in the absence (EV) or presence of cDNA encoding the nuclear forms of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c) or SREBP2 (nS2). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. EV, empty vector. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with a minimal promoter-luciferase construct containing a single binding site for the yeast transcription factor Gal4 (G1E1B-Luc) together with expression vectors for the DNA binding domain of Gal4 (Gal4), or the same DNA binding domain fused to the nuclear forms of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c), or SREBP2 (nS2), and either GFP or PRDM16 (P16). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (D). HepG2 cells were transfected with the same promoter-reporter construct as in (A) together with the DNA binding domain of Gal4 (Gal4), or the same DNA binding domain fused to the transactivation domain (TAD) of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c), or SREBP2 (nS2), and either GFP or PRDM16 (P16) cDNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLU) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The RLU of WT promoter-reporter constructs transfected with either GFP or non-targeted shRNA were set to 1. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

Figure 3.

PRDM16 targets the nuclear forms of SREBP1a, SREBP1c, and SREBP2. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with GFP or PRDM16 (P16) cDNA in the absence (EV) or presence of cDNA encoding the nuclear forms of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c) or SREBP2 (nS2). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with the HMG-CoA synthase promoter-luciferase construct (SYNSRE) together with non-targeted (C) or PRDM16 (P16) shRNA in the absence (EV) or presence of cDNA encoding the nuclear forms of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c) or SREBP2 (nS2). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. EV, empty vector. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected with a minimal promoter-luciferase construct containing a single binding site for the yeast transcription factor Gal4 (G1E1B-Luc) together with expression vectors for the DNA binding domain of Gal4 (Gal4), or the same DNA binding domain fused to the nuclear forms of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c), or SREBP2 (nS2), and either GFP or PRDM16 (P16). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. (D). HepG2 cells were transfected with the same promoter-reporter construct as in (A) together with the DNA binding domain of Gal4 (Gal4), or the same DNA binding domain fused to the transactivation domain (TAD) of SREBP1a (nS1a), SREBP1c (nS1c), or SREBP2 (nS2), and either GFP or PRDM16 (P16) cDNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Cells were also transfected with the β-galactosidase gene as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase values (relative light units, RLU) were calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by the β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The RLU of WT promoter-reporter constructs transfected with either GFP or non-targeted shRNA were set to 1. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

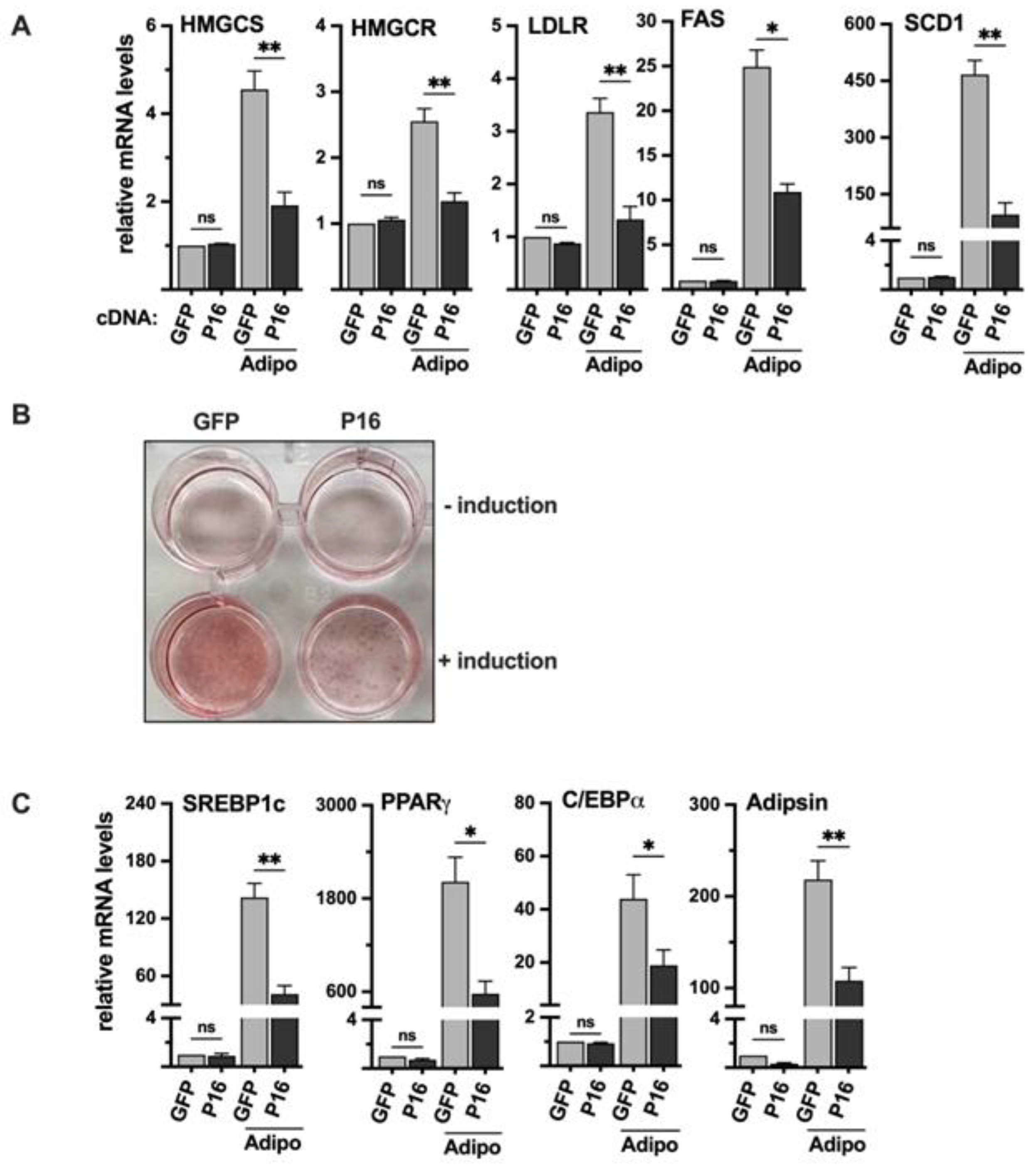

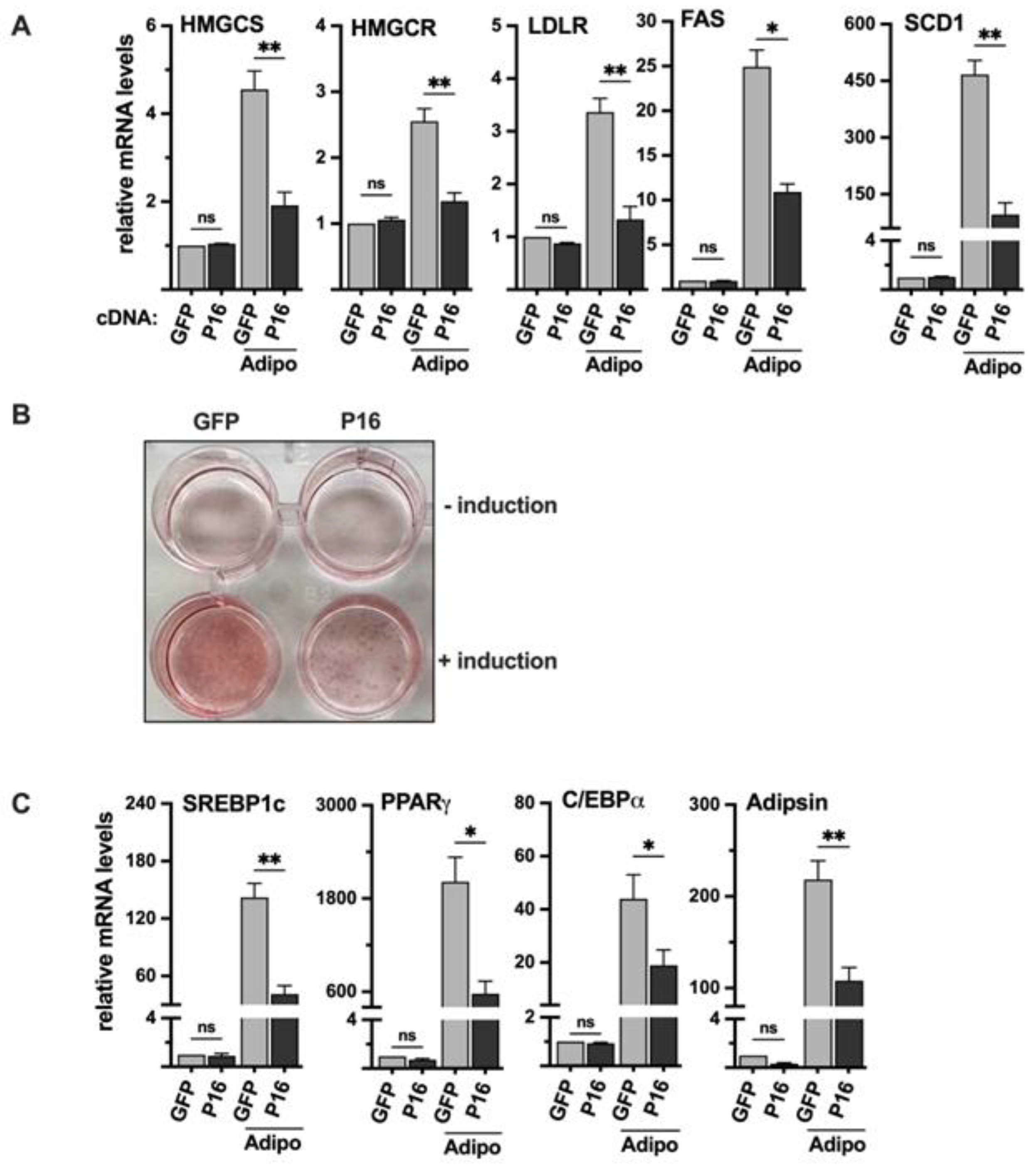

Figure 7.

Ectopic expression of PRDM16 attenuates adipogenesis. (A) 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were transduced with expression vectors for GFP or PRDM16 (P16) and left untreated or differentiated to mature adipocytes (Adipo). RNA was extracted and the expression of HMG-CoA synthase (HMGCS), HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR), the LDL receptor (LDLR), fatty acid synthase (FAS), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD1) was analyzed by qPCR. The relative expression of each gene in undifferentiated GFP-expressing cells was set to 1. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments (B) 3T3-L1 cells were transduced and treated as in (A), fixed and stained with oil red O to visualize the accumulation of lipids. The wells in the upper row are undifferentiated (- induction) and those in the lower row are differentiated (+ induction). (C) 3T3-L1 cells were transduced and treated as in (A). RNA was extracted and the expression of PPARγ, C/EBPα, adipsin, and SREBP1c in undifferentiated and differentiated (Adipo) cells was analyzed by qPCR. The relative expression of each gene in undifferentiated GFP-expressing cells was set to 1. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

Figure 7.

Ectopic expression of PRDM16 attenuates adipogenesis. (A) 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were transduced with expression vectors for GFP or PRDM16 (P16) and left untreated or differentiated to mature adipocytes (Adipo). RNA was extracted and the expression of HMG-CoA synthase (HMGCS), HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR), the LDL receptor (LDLR), fatty acid synthase (FAS), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD1) was analyzed by qPCR. The relative expression of each gene in undifferentiated GFP-expressing cells was set to 1. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments (B) 3T3-L1 cells were transduced and treated as in (A), fixed and stained with oil red O to visualize the accumulation of lipids. The wells in the upper row are undifferentiated (- induction) and those in the lower row are differentiated (+ induction). (C) 3T3-L1 cells were transduced and treated as in (A). RNA was extracted and the expression of PPARγ, C/EBPα, adipsin, and SREBP1c in undifferentiated and differentiated (Adipo) cells was analyzed by qPCR. The relative expression of each gene in undifferentiated GFP-expressing cells was set to 1. The data represent the average −/+ SEM of at least three independent experiments. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. *P < 0 .05, **P < 0 .01, ***P < 0 .001, and ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.