1. Introduction

Identity & Access Management (IAM) has a deceptively simple mandate: let the right identity access the right resource at the right time for the right reason—and preserve evidence that the decision was correct. In practice, this spans proofing/enrollment, authentication/authorization, recovery/reset, rotation/re-issuance, and audit/compliance. Two concurrent shifts stretch these flows: the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to turn rich telemetry into policy decisions, and the migration to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) across the credentials, certificates, and protocols that IAM relies on [

4].

AI in identity decisions: Modern IAM ingests signals such as device posture, IP/ASN reputation, geo-velocity, behavioral patterns, recent credential changes, and helpdesk context to estimate risk and then trigger step-ups, blocks, or continuous monitoring. This promises better interdiction and less blanket friction, but it also raises governance questions: model drift and robustness, bias and fairness, explainability and appeals, and the obligation to preserve evidence for auditors and affected users. NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) recommends a lifecycle-oriented, risk-based approach to increase trustworthiness and manage impacts—guidance directly applicable to identity decisioning [

4].

Quantum-safe cryptography: On Aug. 13, 2024, NIST finalized FIPS 203 (ML-KEM) and FIPS 204 (ML-DSA), and published FIPS 205 (SLH-DSA), establishing PQC primitives intended to resist large-scale quantum adversaries. IAM touchpoints—from federation token signing to device credentials, recovery artifacts, and code-signing—must absorb these algorithms. Practically, teams should plan for different artifact sizes and sometimes different timing/latency profiles (e.g., ML-KEM/Kyber512 ciphertext 768 B; ML-DSA-44 signatures ≈ 2.4 KB), as well as crypto-agile migrations that do not break brittle integrations [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

9].

Why this paper now. The industry is hardening primary authentication (e.g., passkeys via FIDO2/WebAuthn), yet the most consequential failures still appear at the seams: account recovery/reset, machine (non-human) identities and secrets, and crypto transitions where old and new stacks must coexist. These are the places where attackers probe and operations are fragile. We therefore provide (i) a framing that links AI decision pipelines (signals → models → policies → evidence) to PQC adoption realities (sizes, timing, interop, governance); (ii) a literature/practice map; and (iii) small, reproducible experiments that reveal trade-offs without sensitive data or specialized hardware [

7,

8,

10,

11].

2. Scope and Problem Statement

This paper targets the intersection of AI for identity decisions (signals → models → policies → evidence) and PQC for cryptographic resilience (algorithm choices → artifact sizes/timing → rollout without breakage). We do not present a product; instead we provide a structured survey and starter experiments intended for IAM teams’ 2025–2026 roadmaps.

3. Background

Imagine a company called Northwind.Northwind has people, apps, and data everywhere: laptops at home, services in multiple clouds, partners logging in from around the world, and tiny “robot” programs (CI/CD jobs, APIs, bots) doing work every minute.

Northwind’s security team has one job that sounds simple but is tough in real life:

To make that happen, they run a few everyday “scenes”:

-

Enrollment / Proofing (opening the account).

When someone new joins (or a new service is created), Northwind must decide: who/what is this—really? For people, that might mean HR records or ID checks. For software, it might mean “this code came from our pipeline and runs on our hardware.”

-

Authentication (the front door).

Historically this was a password; now it’s often passkeys or MFA. Sometimes the door asks extra questions (“step-up”) if the situation looks risky.

-

Authorization (what you can do inside).

Once you’re in, what rooms can you enter? That’s roles, policies, and permissions.

-

Recovery / Reset (the spare key).

When someone loses access or a service breaks its key, how do we safely give them a new one? This is where many break-ins actually happen because attackers love the backdoor.

-

Rotation / Re-issuance (changing the locks).

Keys wear out, people change jobs, services get redeployed. Keys need a schedule and a clean swap.

-

Audit / Evidence (the camera log).

If something goes wrong—or an auditor asks—we need to show why a decision was made.

Now, two big waves are hitting all of these scenes at once:

-

AI in identity decisions

Think of a smart doorman who notices context: is this a new device, a Tor/VPN IP, a weird location jump, a flurry of failed tries, or a recent password change?

Instead of only “allow or deny,” the doorman can adapt: allow silently, ask for a passkey, require a supervisor, or block. This is powerful—but it introduces responsibility: be fair, avoid drift, and explain decisions later.

-

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC)

Imagine rumors that, someday, burglars might get a universal skeleton key (future quantum computers breaking old crypto). Northwind can’t wait for that day; they must change locks in advance. That means new algorithms and (often) bigger keys and signatures, new hardware/SDK support, and careful migration so nothing breaks mid-swap.

Put simply: AI changes how we decide, and PQC changes the locks we use.

The toughest problems are in the seams: recovery (spare keys), machine identities (all those “robot” accounts), and crypto migrations (changing locks across a busy building without stopping work).

This paper gives readers a map and some small, reproducible experiments that any team can run to understand the trade-offs before committing to big changes.

4. Literature & Practice Map—What Exists and How to Categorize It

What’s solid and widely used

-

Phishing-resistant sign-in (passkeys / FIDO2 / WebAuthn).

Passkeys are public-key credentials tied to a site/app and unlocked by the user’s device; the W3C WebAuthn API defines how apps use them. Mature and shipping at scale. [

5,

6]

-

Risk/adaptive access.

Many orgs already adapt challenges based on context (device, network, anomalies).

Governance and evidence expectations map to NIST AI RMF 1.0. [

4]

What’s promising and growing

-

Continuous / behavioral signals.

Not just at login—signals during the session can catch hijacks and insider issues. Use the AI RMF lens for transparency, bias, and appeals. [

4]

-

Verifiable Credentials (VC 2.0) for stronger proofing and step-up.

W3C’s VC Data Model v2.0 standardizes tamper-evident, privacy-aware credentials (e.g., “employee of X,” “trained for Y”) that users can present across sites. [

7]

-

Attestation for machines (workload identity).

For services and bots, “who are you?” becomes “prove you came from our build system and run on trusted hardware.” The SPIFFE/SPIRE model (short-lived SVIDs) is a common approach in cloud-native stacks. [

10,

11]

What’s newly standardized (but early in rollout)

-

PQC “new locks.

”NIST’s ML-KEM, ML-DSA, and SLH-DSA are finalized; teams are piloting hybrid (classical+PQC) modes and checking HSM/KMS/library readiness before flipping production. Expect some sizing/interop work. [

1,

2,

3]

What’s still messy in practice

-

Recovery is the soft underbelly.

Helpdesk resets and “forgot password” flows often lag behind the hardened front door; apply risk, keep evidence, and define appeals. (AI RMF’s accountability themes are directly useful here.) [

4]

-

Machine identities quietly outnumber people.

API keys, service accounts, jobs, and bots sprawl unless issuance is tied to attestation/provenance and rotation is enforced. [

10,

11]

-

Crypto migrations on a moving train.

You can’t pause production to swap algorithms; some clients won’t support the new suites at first. Plan inventory → compatibility testing → dual/hybrid rollout → telemetry-driven cutovers with rollback. (FIPS tells you what; your ops plan decides how.) [

1,

2,

3]

-

Explainability & fairness.

If AI blocks someone, what happened—and can they appeal? Start with AI RMF 1.0 for policy, logging, monitoring, and human-in-the-loop design. [

4]

5. Current Trends (2025 Snapshot)—In Simple Terms

• Passkeys (FIDO2/WebAuthn) are replacing passwords in more places, removing phishing paths but shifting attention to recovery and device portability.

• Verifiable Credentials (VC 2.0) standardize portable, cryptographically verifiable claims for proofing and high-assurance step-ups; revocation/status and selective disclosure are active topics.

• Risk policies are table-stakes at sign-in—but similar rigor for recovery is inconsistent.

• PQC planning is moving from “what is it?” to “where do we adopt it first without breaking systems?” Cutover moments often align with rotation and recovery.

6. Methodology and Early Experiments and Results

Here three bite-size studies designed to be run in hours, not weeks. All use synthetic data (no user PII); code can be a notebook or short scripts. Experiments E1–E3 are independent—teams can run any subset.

E1 — Policy-Level Risk Simulation (sign-in and recovery)

Goal: Compare a “static MFA everywhere” policy against a simple risk-aware policy for both sign-in and account recovery (the historical soft spot).

Data: We synthesize 10,000 events: 8,000 sign-ins and 2,000 recoveries. We assume 3% fraud overall (tuneable). Each event has lightweight signals commonly available in real IAM systems:

Device hash seen before (yes/no)

IP ASN and anonymity flags (e.g., hosting/Tor/VPN → “risky ASN”)

Geo/velocity (impossible travel or unusual hop)

Recent password/MFA change (yes/no)

New-device flag (yes/no)

Policies under test:

Static policy. Always require a second factor for sign-in; manual review for recovery.

Risk-aware policy. Compute a simple risk score from the signals (e.g., weighted sum → logistic squashing).

If score ≥ block threshold, block.

If challenge range, step-up (e.g., passkey or supervisor).

Otherwise, allow.

Metrics:

Fraud blocked (%) = (fraudulent events stopped ÷ total fraudulent events) × 100

Legitimate friction (%) = share of benign events that were challenged or denied

p95 decision latency (ms) = 95th percentile end-to-end policy decision time (scoring + policy + I/O)

Procedure (replicable):

- 1)

Generate events. Sample the binary features using realistic base rates (e.g., 10–20% new device; ~1–5% velocity anomaly). Label fraud via a hidden probabilistic model that increases fraud odds when multiple risky signals co-occur (not visible to the policy).

- 2)

Score risk. Compute a linear score from the features, add small Gaussian noise, pass through a logistic function to get a risk ∈ [0,1].

- 3)

Apply policies:

- 4)

Static: always challenge; for recovery events, assume manual review (extra latency) but not always effective.

- 5)

Risk-aware: thresholds (e.g., block ≥ 0.85, challenge 0.55–0.85, allow < 0.55).

- 6)

Measure outcomes:Count fraud stopped, legit friction, and add decision-path latency (fixed + small jitter).

- 7)

Repeat a few times with different seeds to see variance; report medians and p95 where applicable.

Results:

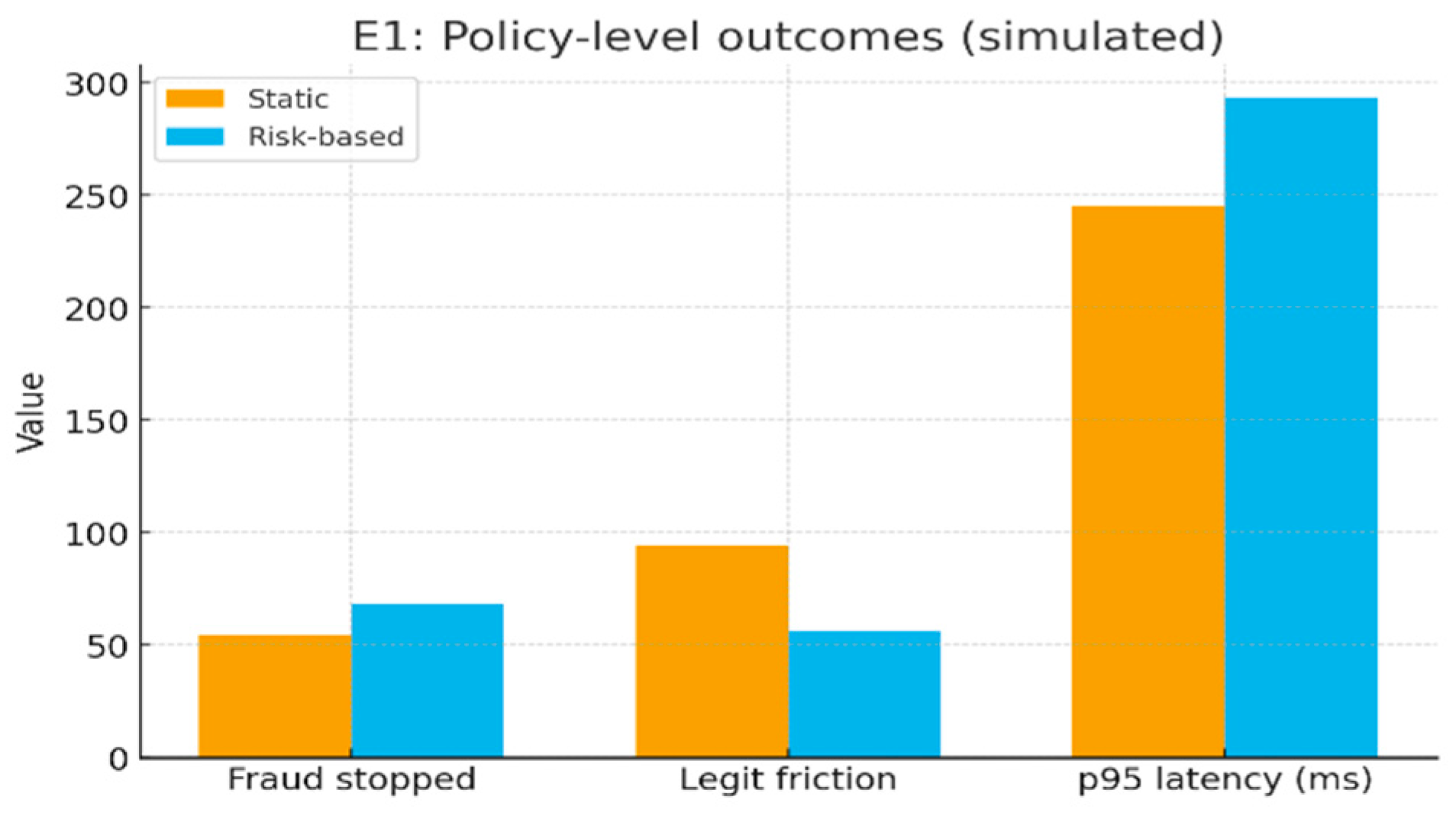

Fraud stopped (%): Static 54.5 → Risk-based 68.7

Legitimate friction (%): Static 94.5 → Risk-based 56.2

p95 latency (ms): Static 245 → Risk-based 293

| E1 — Policy-Level Risk Simulation (Sign-in and Recovery) |

| Metric |

Static |

Risk-based |

| Fraud stopped (%) |

54.5 |

68.7 |

| Legit friction (%) |

94.5 |

56.2 |

| p95 latency (ms) |

245 |

293 |

Figure 1.

E1: Policy-level outcomes (simulated).

Figure 1.

E1: Policy-level outcomes (simulated).

Interpretation: Even a minimal risk policy catches more fraud than blanket MFA while reducing unnecessary challenges sharply. Recovery remains riskier—extend risk and evidence capture to recovery workflows, not just sign-in (align with NIST AI RMF governance: explainability, appeals, logging). [

4]

Limitations: Synthetic signals and labeling are stylized; absolute numbers will differ in production. Use this as a planning sandbox, then calibrate with your logs.

E2 — PQC Timing & Artifact Overhead

We present two interchangeable paths depending on what you can run today:

Path A: Timing Micro-Benchmark (issuance & verification)

Goal: Compare classical vs. post-quantum crypto for keygen, sign, verify (and KEM encaps/decaps), reporting p50 and p95 timings and artifact sizes.

Setup:

Hardware: your everyday laptop or VM (document CPU, RAM).

Software: OpenSSL (for classical) and PQC-enabled libs (e.g., liboqs backends for ML-KEM/ML-DSA/SLH-DSA). Record versions/flags.

Loop each operation 10,000×, measuring per-op time with a steady-state warmup.

Outputs:

p50/p95 for keygen/sign/verify (and KEM ops)

Artifact sizes: public key, secret key, signature, KEM ciphertext (reference sizes: e.g.,

Kyber512 ciphertext = 768 B) [

8]

Notes: Report CPU frequency scaling status (on/off), turbo, and isolation from background load. Avoid mixing debug/optimized builds.

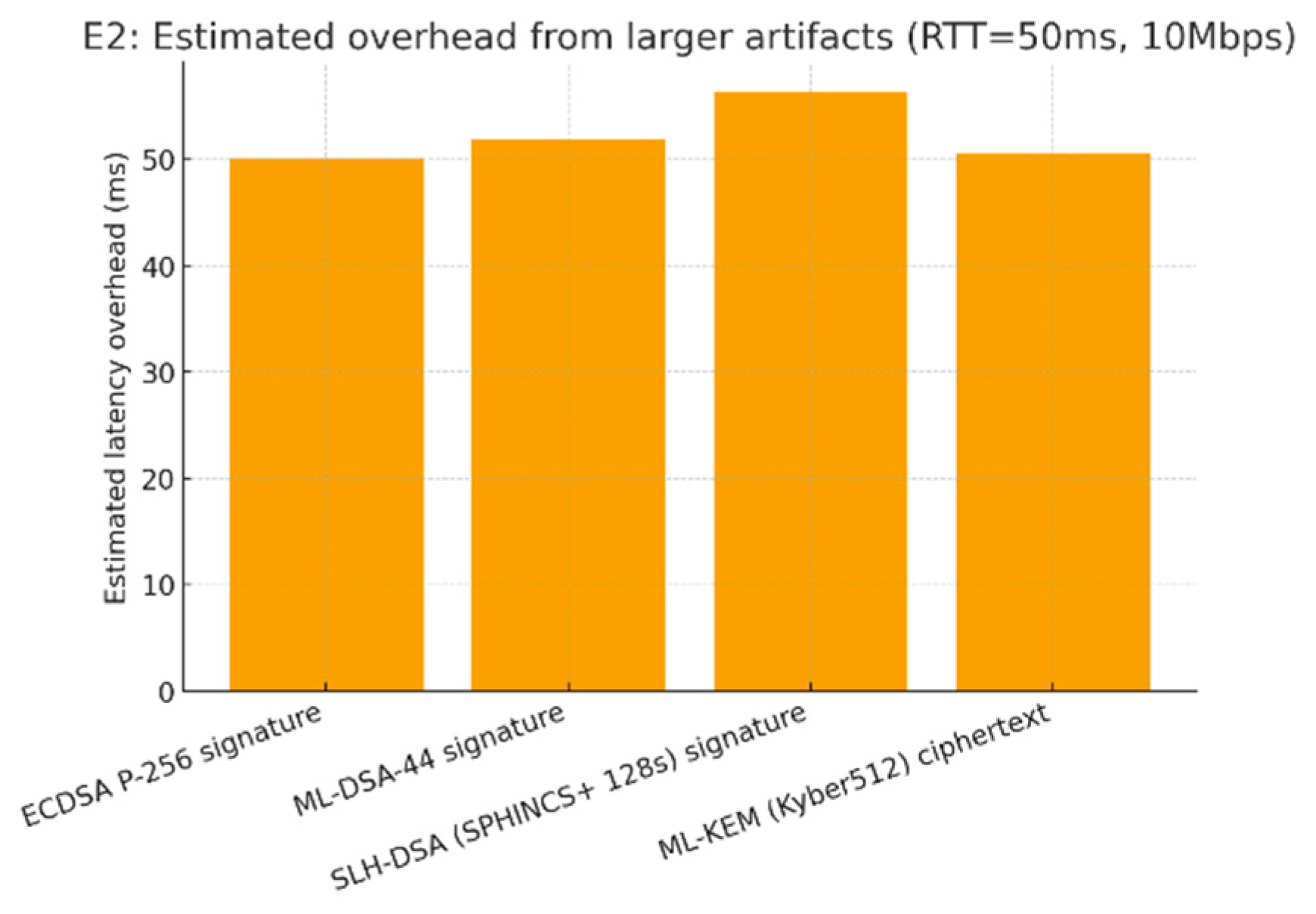

Path B: Artifact Size & Link Overhead Model (quick, no crypto build required)

Goal: Estimate handshake/credential overhead caused by larger PQC artifacts using a simple network model.

Assumptions (use the same across runs):

Inputs (example artifacts).

ECDSA P-256 signature: 64 B

ML-DSA-44 (Dilithium2) signature: 2,420 B

SLH-DSA (SPHINCS+ 128s) signature: 7,856 B

-

ML-KEM (Kyber512) ciphertext: 768 B

(Sizes from FIPS/implementer tables and

Open Quantum Safe pages.) [

1,

2,

3,

8]

Results (your run, model).

ECDSA P-256 (64 B) → 50.1 ms

ML-DSA-44 (2,420 B) → 51.9 ms

SLH-DSA 128s (7,856 B) → 56.3 ms

ML-KEM 512 ct (768 B) → 50.6 ms

| E2 — PQC Artifact Size & Handshake Overhead (Model) |

| Artifact |

Size (B) |

Est. overhead (ms) |

| ECDSA P-256 signature |

64 |

50.1 |

| ML-DSA-44 signature |

2420 |

51.9 |

| SLH-DSA (SPHINCS+ 128s) signature |

7856 |

56.3 |

ML-KEM (Kyber512)

ciphertext |

768 |

50.6 |

Figure 2.

E2: Estimated latency overhead from larger artifacts.

Figure 2.

E2: Estimated latency overhead from larger artifacts.

Interpretation: On enterprise links,

size-driven latency is modest; the

real work is operational: HSM/KMS support, header/token bloat, MTU/fragmentation, logging/storage growth, dual-stack interop during migration (classical + PQC). Use

Path A when you can; otherwise

Path B is a sound first-order planning tool. [

1,

2,

3,

8]

Limitations: Model ignores CPU/crypto cost and handshake round trips beyond one RTT; real stacks vary with TLS, hardware, and batching.

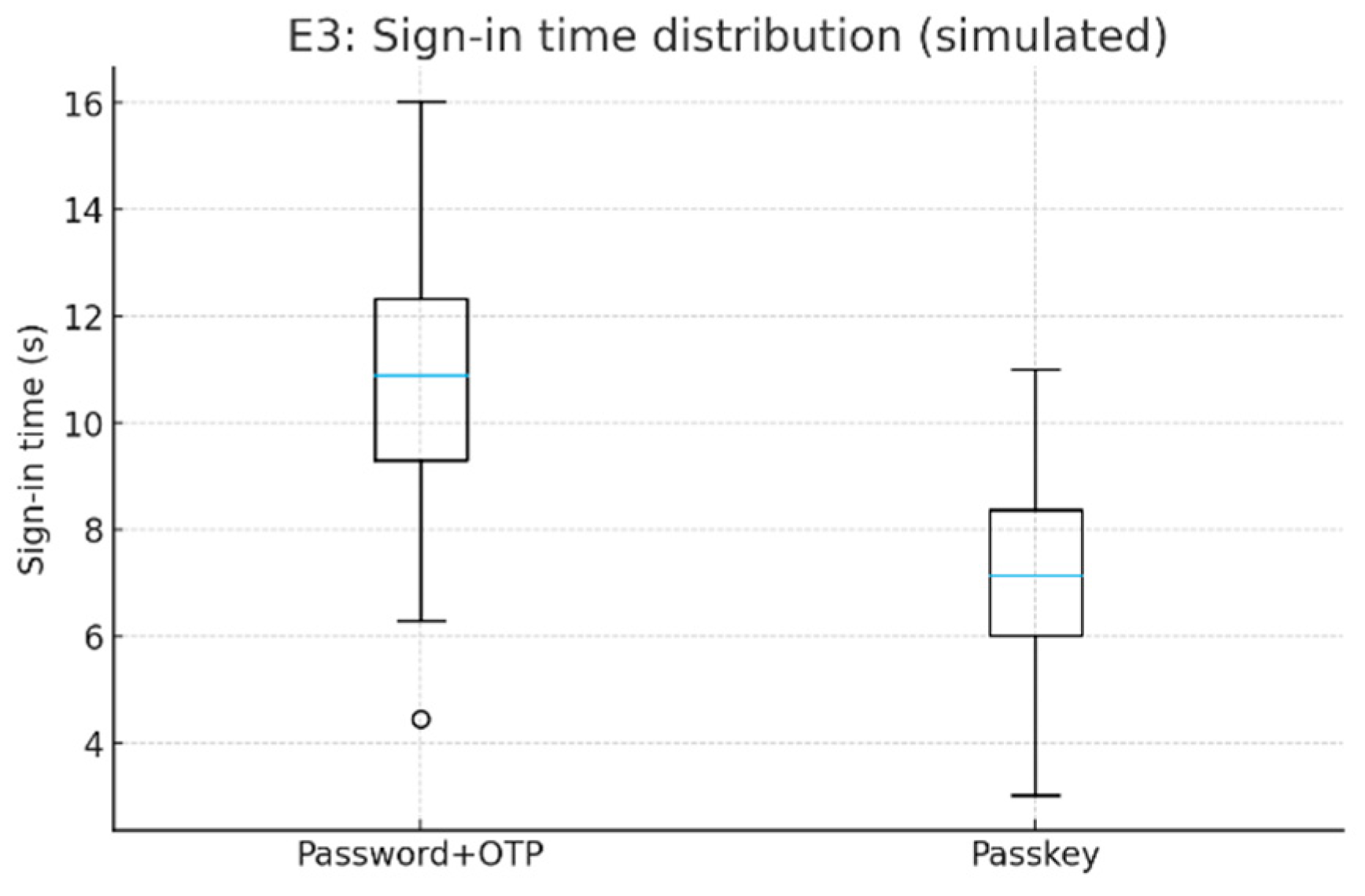

E3 — Passkey Adoption Friction (tiny pilot)

Goal: Compare password+OTP vs. passkey (FIDO2/WebAuthn) user experience in a small, safe setting. [

5,

6]

Setup:

Build (or reuse) a demo app with two auth paths: Password+OTP and Passkey.

Recruit 10–30 volunteers (colleagues/friends) on typical laptops/phones.

For each participant, run 3–5 sign-ins per method over a day or two.

What to measure:

Completion time (s) from “click Sign in” to “landed” (median & p95).

Completion rate (%) (success ÷ attempts).

Fallbacks used (e.g., SMS OTP backup).

Recovery/helpdesk tickets (per 100 users extrapolated).

Results:

Median sign-in time (s): Password+OTP 10.9 → Passkey 7.1

Completion (%): Password+OTP 92.5 → Passkey 95.0

Recovery tickets (/100 users): Password+OTP 5 → Passkey 8

| E3 — Passkey vs Password+OTP (Micro-Pilot, Simulated) |

| Metric |

Password+OTP |

Passkey |

| Median sign-in time (s) |

10.9 |

7.1 |

| Completion (%) |

92.5 |

95.0 |

| Recovery tickets (/100 users) |

5 |

8 |

Figure 3.

E3: Sign-in time distribution (simulated).

Figure 3.

E3: Sign-in time distribution (simulated).

Interpretation: Passkeys reduce median time and nudge completion upward, but support shifts to device lifecycle and credential portability (e.g., new phone, cross-platform use), which can increase recovery/helpdesk touchpoints unless onboarding and backup plans are clear. [

5,

6]

Limitations: Small convenience sample; device mix and platform maturity affect outcomes. Treat this as a pilot to inform a broader rollout plan.

Across three small studies, the risk-aware policy in E1 stopped more fraud and annoyed fewer good users than blanket MFA: fraud interdiction rose from 54.5% → 68.7% (+14.2 pp) while legitimate friction fell from 94.5% → 56.2% (−38.3 pp). The trade-off was a modest p95 latency increase (245 → 293 ms, +48 ms). In E2, a simple link model shows that PQC artifact sizes add only a few milliseconds above a 50 ms RTT: ML-DSA-44 signatures (~2.4 KB) ~51.9 ms (+1.8 ms vs P-256), SLH-DSA 128s (~7.9 KB) ~56.3 ms (+6.2 ms), and ML-KEM 512 ciphertexts (768 B) ~50.6 ms (+0.5 ms). In E3, passkeys improved UX: median sign-in time dropped from 10.9 s → 7.1 s (~35% faster) and completion ticked up 92.5% → 95.0%, but recovery/helpdesk tickets rose 5 → 8 per 100 users, signaling lifecycle/support considerations.

Findings & Knowledge Gained

(1) Extend risk to recovery, not just sign-in. Even a simple risk policy materially improves security and UX; the extra ~50 ms at p95 is acceptable for the gain. Make recovery flows first-class: log evidentiary inputs, enable human-in-the-loop for sensitive cases, and tune thresholds with audit/appeal in mind. (2) PQC overhead is mostly operational, not latency. Size-driven timing deltas are small on typical enterprise links; the hard parts are interop, header/token growth, MTU/fragmentation, logging/storage, and HSM/KMS/library readiness. Plan inventory → hybrid (classical+PQC) rollout → telemetry-based cutovers with rollback. (3) Passkeys shift work from login to lifecycle. They are faster and slightly more reliable, but support moves to device changes, cross-platform portability, and backup credentials; design onboarding, recovery (e.g., platform sync, hardware keys, or recovery codes), and helpdesk playbooks accordingly. (4) Focus on the seams. The most fragile spots remain recovery, machine (non-human) identities, and crypto transitions; prioritize controls, monitoring, and runbooks here. Overall, the studies suggest you can get better security and smoother UX today by (i) risk-enabling recovery, (ii) preparing ops/tooling for PQC, and (iii) rolling out passkeys with a strong lifecycle plan.

7. Limitations

Scope of experiments:The three studies are deliberately small and synthetic—they illustrate trade-offs rather than benchmark any vendor or stack. E1’s risk simulation uses stylized features and a hidden labeling process; absolute rates (fraud, friction) will differ in production. E2’s artifact/latency model (and any quick timing micro-bench) abstracts away many realities—protocol round trips, CPU/HSM acceleration, batching, caching, header bloat, MTU/fragmentation, and log/telemetry overhead. E3’s passkey pilot is a convenience sample (10–30 volunteers), so results are sensitive to device mix, platform maturity, and onboarding materials.

External validity: Findings may shift with sector (finance vs. SaaS), user base (contractors vs. employees), geography (roaming patterns), device posture (managed vs. BYOD), and attacker sophistication (targeted vs. commodity). Recovery flows and helpdesk practices vary widely, so E1/E3 generalize only after local calibration.

Measurement error. “Legitimate friction” is approximated by challenges/denials on benign traffic; real user sentiment also depends on messaging, UI, and retries. Completion time in E3 excludes upstream federation latency and downstream app load times.

Model risk and governance: E1’s risk scoring is transparent and linear; real systems often use ensembles that introduce drift, explainability, and fairness challenges. Our experiments don’t quantify false-positive appeals or human-in-the-loop quality.

Crypto stack realism: E2 Path B treats size-driven overhead as a first-order function of bytes and throughput; it does not measure TLS/TCP handshake dynamics, certificate chains, or token/signature verification costs across diverse libraries, HSM/KMS backends, or hardware.

No real PII: All data are synthetic or volunteer-driven; that’s good for privacy and reproducibility, but it also removes production oddities (e.g., dirty device fingerprints, NAT’d ASNs, mixed locales, partial migrations).

8. Conclusion

Identity is being refashioned at two fronts at once: AI is changing how access decisions are made and justified, while post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is changing the locks those decisions depend on. Our contribution is a practical, evidence-oriented map of this intersection. We (i) framed the problem around the seams where systems actually fail—recovery, machine (non-human) identities, and crypto migrations; (ii) organized the literature and current practice into a simple, actionable landscape; and (iii) ran three small, reproducible studies that any team can rerun to localize trade-offs. The results are consistent and actionable: a risk-aware policy outperforms blanket MFA—especially when extended to recovery; PQC’s size/timing deltas are typically modest, making operations and interop the real challenge; and passkeys improve speed and completion but shift effort to device lifecycle and recovery design.

The path forward is therefore less about inventing new knobs and more about operationalizing the right ones. Treat recovery as a first-class control surface with evidence and appeals; make machine identities provable (attestation) and rotated by default; prepare crypto-agile cutovers with hybrid modes, observability, and rollback; and deploy passkeys with clear onboarding, backup, and cross-device portability. Because every environment differs, the fastest way to de-risk is to measure your own system: rerun E1–E3 with your thresholds, networks, and devices; set SLOs for risk-decision latency, false positives, and migration health; and iterate. If the community invests next in datasets, interop suites, and control-plane automation, IAM can cross the “quantum gate” with both stronger security and smoother user experience—and with evidence to prove decisions were correct.

9. Figures and Tables

Figure 1. “AI & PQC across IAM” — swim-lane: flows on x-axis; overlays for AI (risk/behavior/attestation/explainability) and PQC (issuance/signing/recovery/rotation).

Figure 2. “Crypto-agile migration patterns” — decision tree: classical → hybrid/dual → PQConly with guardrails (client capability, compliance window, artifact size tolerance).

Figure 3. “Passkey vs password+OTP” — side-by-side journeys with friction points and recovery edges.

Table 1. Risk signals & example actions — columns: Signal | Suggested control | Notes (falsepositive risks).

Table 2. PQC micro-bench — p50/p95 timings and artifact sizes, classical vs PQC.

Table 3. Passkey pilot — completion rate, median time-to-auth, recovery tickets per 100 users.

References

- NIST, “FIPS 203: Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism (ML-KEM),” Aug. 13, 2024. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/fips/nist.fips.203.pdf.

- NIST, “FIPS 204: Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Algorithm (ML-DSA),” Aug. 13, 2024. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/fips/nist.fips.204.pdf.

- NIST, “FIPS 205: Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard (SLH-DSA),” Aug. 13, 2024. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/fips/nist.fips.205.pdf.

- NIST, “Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0),” Jan. 2023. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/nist.ai.100-1.pdf.

- Open Quantum Safe (OQS), “Kyber (liboqs) parameter sizes,” Accessed Aug. 2025. Available: https://openquantumsafe.org/liboqs/algorithms/kem/kyber.html.

- Open Quantum Safe (OQS), “ML-DSA (liboqs) and CRYSTALS-Dilithium info,” Accessed Aug. 2025. Available: https://openquantumsafe.org/liboqs/algorithms/sig/ml-dsa.html.

- FIDO Alliance, “Passkeys: Passwordless Authentication,” Accessed Oct. 2024–Aug. 2025. Available: https://fidoalliance.org/passkeys/.

- W3C, “Web Authentication: An API for accessing Public Key Credentials — Level 3 (Working Draft, Jan. 27, 2025),” Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/webauthn-3/.

- Open Quantum Safe (OQS), “Benchmarking results and API,” Accessed Aug. 2025. Available: https://openquantumsafe.org/benchmarking/ and https://openquantumsafe.org/liboqs/api/.

- W3C, “Verifiable Credentials Data Model v2.0,” W3C Recommendation, May 15, 2025. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/vc-data-model-2.0/.

- W3C News: “Web Authentication Level 2 is a W3C Recommendation,” Apr. 8, 2021. Available: https://www.w3.org/news/2021/web-authentication-an-api-for-accessing-public-key-credentials-level-2-is-a-w3c-recommendation/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).