Introduction

Through pea hybridization experiments, Gregor Mendel proposed the concept of "hereditary factors" in 1865, speculating that biological traits are controlled by them. Since then, genes—as carriers of genetic information—have been central to biological research. Genes perform distinct functions and operate with a degree of autonomy. However, when their numbers reach a critical threshold, does a systemic controlling strategy needed? Absolutely! This is analogous to how a large corporation requires a management hierarchy to coordinate its workforce. The strategy we discuss here is not simply about "regulating" gene expression, as previously thought. Instead, it is a pure one-way restriction on genes, which is the essence.

Why is this the case? It stems from the characteristics of biological body structures. From viruses to humans, body structures become more and more intricate. Cells, tissues, and organs differentiate into more diverse types. Expression patterns also vary greatly between cells, enabling formation of specialized functions. Every cell (with the exception of some B lymphocytes) of the same individual generally contains the same genome. But in each, many genes must be silenced. For example, the human genome has ~20,000 protein-coding genes[

1,

2], but any given cell typically expresses only 10-20% (Human Protein Atlas data). Most genes never activate. Therefore, pre-restricting gene expression is the strategy’s primary role.

In fact, this systemic one-way restriction strategy is as ancient as genes themselves. Its complexity scales with gene numbers. Unfortunately, it has long been overlooked. The paper here suggests it likely pre-closes gene expression by setting up layers of "genetic fences."

Derivation of the Genetic Fence Concept

Introns, repetitive sequences, pseudogenes, transposons, and other non-protein-coding sequences are often labeled as "junk" DNA[

3,

4,

5], making up about 98% of the human genome[

6]. Research has linked junk DNA to diseases like cancer, autism, and neurodegenerative disorders[

3,

7,

8,

9]. Deleting introns in yeast affects metabolism[

10], and removing retrotransposons in mice disrupts development[

11]. These findings suggest junk DNA is vital for biological processes. Yet, why it occupies such a large genome proportion remains unclear.

The author, Y.g. Ren, noticed that junk DNA acts like a fence. For example, repetitive sequences, pseudogenes, and transposons space out adjacent genes by separating them over long distances. Meanwhile, introns divide a gene internally into multiple exons that are apart from each other. The transcribed intron sequences within the precursor messenger ribonucleic acids (pre-mRNAs) prevent the translation process unless being excised. Further observations showed that the nuclear membrane also serves as a fence, isolating the nuclear genome from transcription factors, ribosomes, and mitochondrial DNA in the cytoplasm, creating barriers for transcription, translation, and mitochondrial-nuclear communication. We thus hypothesize that pre-inserting fence-like elements around protein-coding sequence to pre-close its expression is a widely used strategy in the biosphere.

More Complex Organisms Have More Fences

Prions are self-replicating, infectious protein particles that pass genetic information from protein (P0) to protein (P1). In viruses and higher organisms, protein sequence information is first stored in an intermediate hub—the DNA/RNA genome—before being passed to offspring proteins. By comparison with prions, it can be found that the emergence of DNA or RNA genomes in other organisms is like adding an extra fence, complicating the replication of genetic information from parental to offspring proteins. Consequently, the genome, in essence, represents one manifestation of the genetic fence strategy. Simple viruses have RNA genomes that directly serve as protein translation templates. More complex viruses use DNA genomes, adding a transcription step that complicates genetic information transfer (

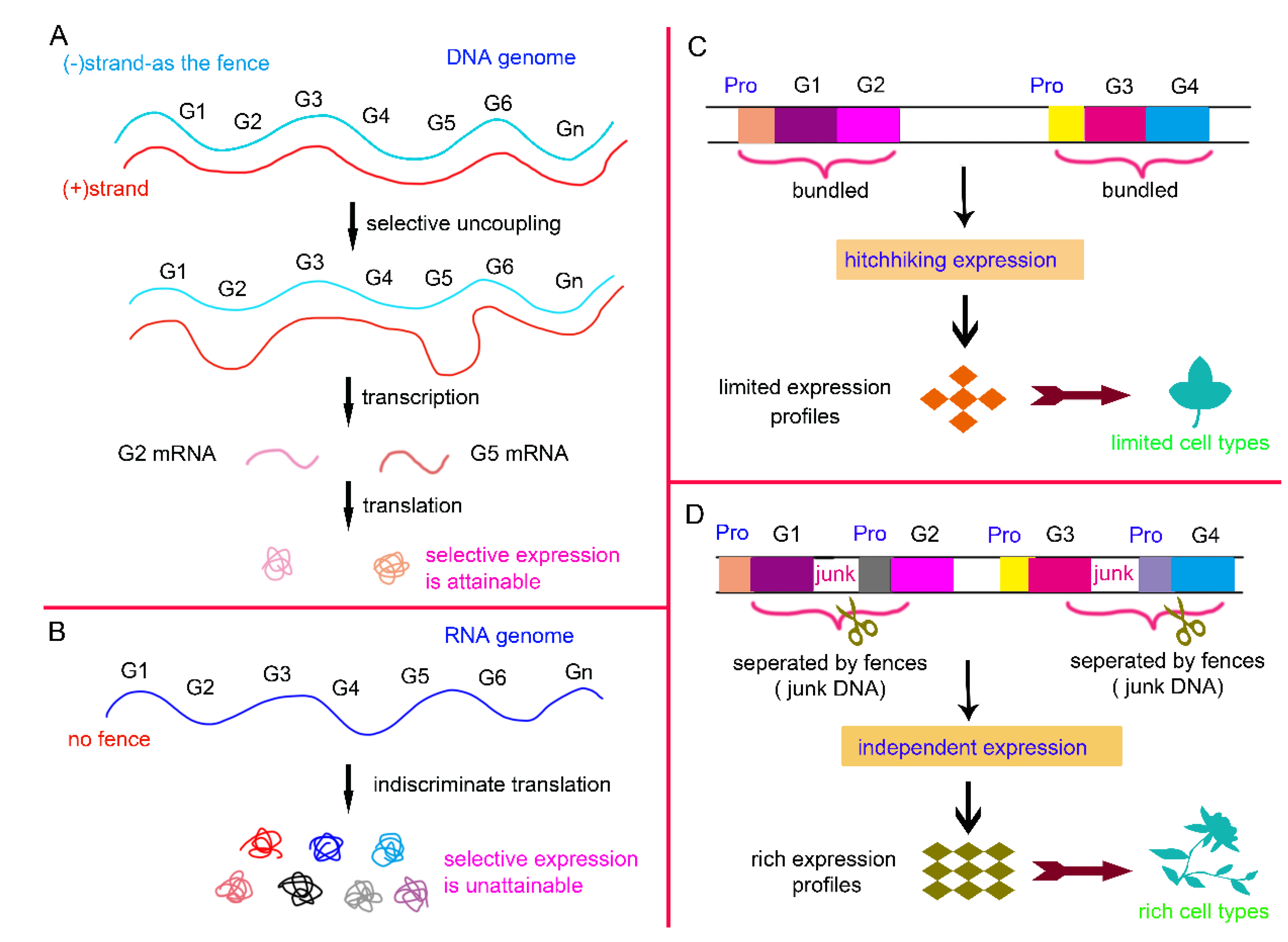

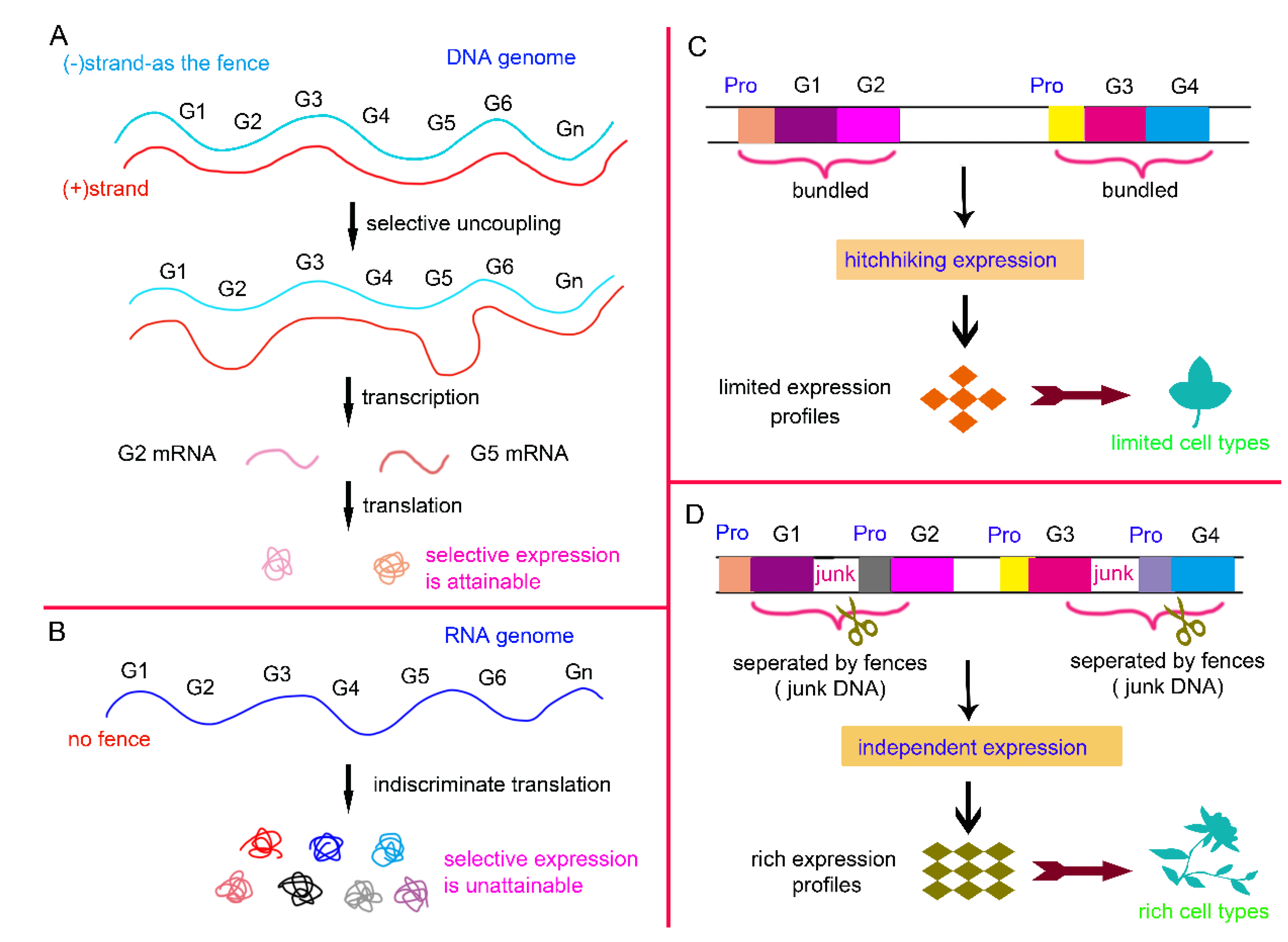

Figure 1A, B). Not all viral genomes are double-stranded, unlike bacterial genomes, which are. The double-stranded structure acts as a fence, requiring unzipping before transcription. The bacterial genome is circular, while the fungal genome is segmented, as if separated by fences. In comparison with those of bacteria, fungal chromosomes are wrapped in histones and are highly compressed, forming structures like heterochromatin. The dynamic DNA shapes such as compression, folding, and heterochromatization, along with surrounding structures like histones and nucleosomes, all act as fences. They encase genes, making them inaccessible to transcription factors or RNA polymerases.

In prokaryotes such as

E. coli, functionally related genes may cluster together and share a common promoter, forming operons (e.g., the lac operon). In more complex organisms like yeast, nematodes, and fruit flies, operons become less common. In mice and humans, they are nearly absent, with adjacent genes completely separated by non-coding regions (e.g., repetitive sequences, pseudogenes, and transposons) and each gene thus has its own promoter. In operons, adjacent genes can "hitch a ride" with each other during gene expression. When operon structures are disrupted, each gene must now have its own promoter pre-activated to initiate expression. Nevertheless, as genes become independent, they can freely form a greater variety of expression combinations, which contributes to the enrichment of gene expression profiles and the diversification of cell types (

Figure 1C, D).

In summary, from simple to complex organisms, there are increasingly stringent restrictions on gene expression, with more "fence-like" structures emerging.

The Genetic Fences Should Be Essential for Cellular Homeostasis

No cell in the human body expresses all genes. Instead, each expresses only a subset selectively. This allows cells to develop a unique protein expression profile, enabling them to perform specific physiological functions. For example, pancreatic beta cells predominantly express insulin but not salivary amylase, while salivary gland cells express high levels of amylase but not insulin. The human genome contains approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes. If all were simultaneously expressed in a single cell, the resulting proteins would inevitably interact through molecular forces, disrupting cellular homeostasis. Moreover, such indiscriminate expression would waste the cell’s biological resources and energy. Therefore, all cell types must possess shared mechanisms to prevent stochastic gene expression in advance. This phenomenon can undoubtedly be explained by the existence of genomic "fencing" mechanisms.

In bacteria and higher organisms, the DNA genome exists as a double-helix. Gene transcription requires pre-unwinding it. Thus, genes are in a "pre-off" state by default (

Figure 1A). In contrast, some simple viruses typically carry single-stranded DNA or RNA genomes. Lacking the double-helical fence, their genes are more directly expressed upon entering a host cell (

Figure 1B). This trait may facilitate rapid growth and replication for viruses.

Other genetic fences, such as introns, the nuclear membrane, histones, and higher-order DNA folding, also limit stochastic gene expression. In sum, these elements work together to reduce transcriptional noise, allowing specialized genes in differentiated cells to function efficiently without interference. Using the "genetic fence" concept, we can clarify why the dramatic expansion of genome size from viruses (usually with dozens of genes) to humans (with approximately 20,000 protein-coding genes) has not led to the collapse of cellular homeostasis.

The Genetic Fences Lay Foundation for Cell Differentiation, Organism Development, and Species Diversification

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, harbors approximately 29 genes[

12]. For comparison, E. coli boasts a gene repertoire exceeding 4,000[

13,

14]. The yeast genome is more complex, containing around 6,000 genes[

15,

16]. Notably, the nematode

Caenorhabditis elegans contains roughly 20,000 genes[

17], a count that is also observed in mice and humans. This pattern suggests that gene numbers increase in tandem with organismal complexity. However, starting from nematodes to humans, the expansion of gene counts appears to plateau. This indicates that ~20,000 genes may mark an upper limit—or at least suffice. From nematodes to humans, continued bodily complexity likely stems from diversifying and expanding genetic fences, rather than from accumulating more genes. For example, the proportion of so-called "junk DNA" in the human genome is significantly higher than that in the nematode genome.

No single protein can independently carry out any fundamental cellular activity. Instead, multiple proteins must cooperate to accomplish these tasks. Take the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle as an example—it relies on the coordinated action of numerous enzymes. More complex organisms possess more intricate cellular activities or functions, which may be linked to the more flexible interactions among genes. In nematodes, sometimes several adjacent genes share a single promoter, thereby forming an operon. While this enables rapid coordinated gene activation, it restricts differential expression (gene-specific regulation). In the human genome, extensive noncoding intergenic sequences are inserted between adjacent genes. Each gene thus acquires its own promoter, which enhances its autonomy of expression and enables its proportional combinatorial interactions with other genes. This should facilitate emergence of new cellular functions, which serves as foundation for the expansion of cell types and the increase in biological complexity (

Figure 1C, D).

The ecosystem may use the genetic fences to differentially pre-repress expression of homologous genes, then distinct species can undergo a form of "differentiation," akin to how cellular differentiation occurs within an individual. That is why many organisms share remarkably high genetic homology with each other, yet their bodily structures and life habits differ significantly.

In sum, inserting genetic fences can pre-silence gene expression while leaving room for independent activation. This is the foundation for cell differentiation, organism development, and species diversification.

The Genetic Fences Safeguard Against Cellular Carcinogenesis

Complex animals, including humans, have a vast quantity and diverse types of cells. Even when a minuscule proportion of these cells become cancerous, it can prove lethal. Hence, preventing cellular carcinogenesis is an urgent priority for them.

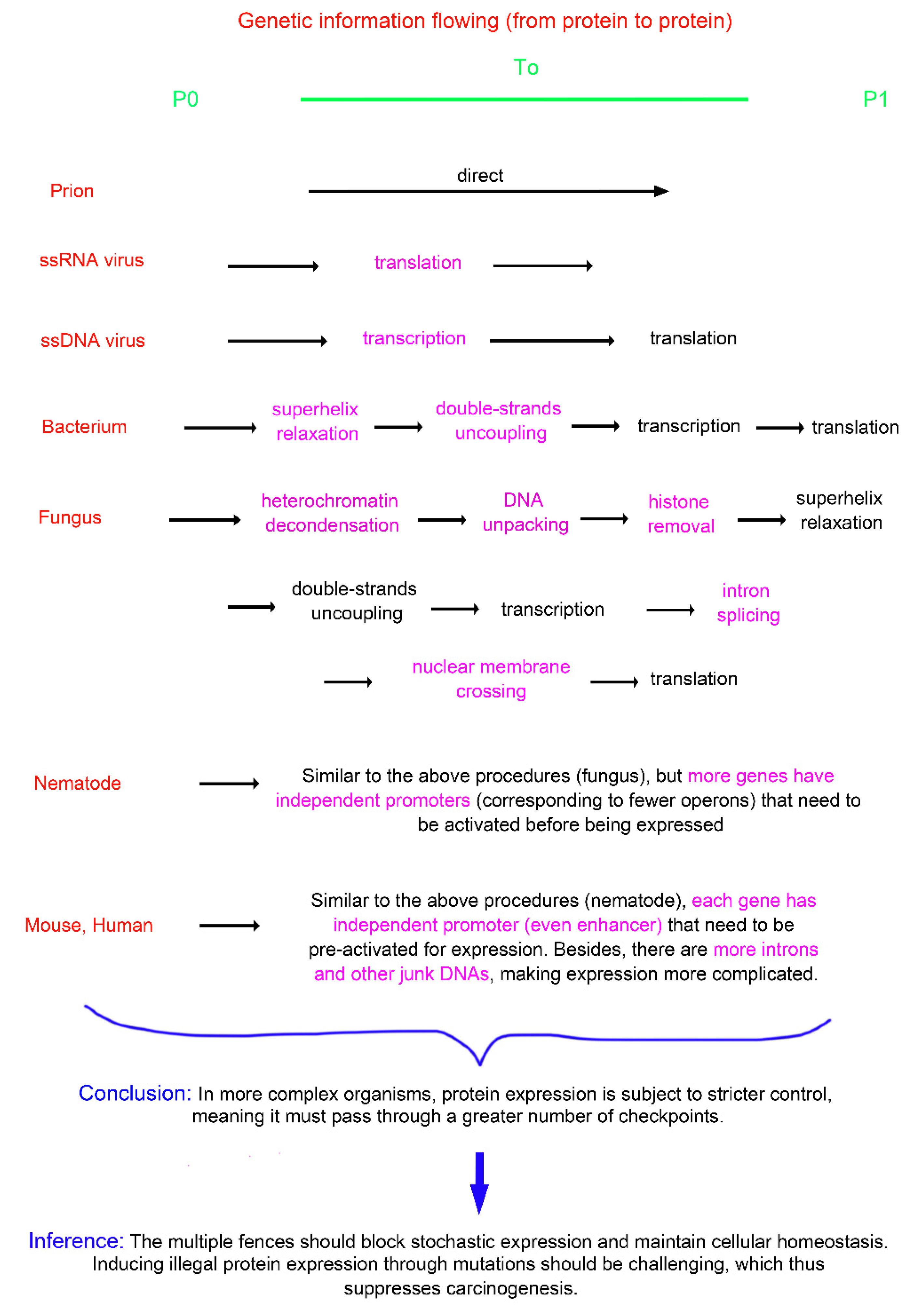

Under the joint influence of genetic factors, environmental exposures, aging processes, and other contributing elements, the genome gradually undergoes mutations. Over time, these mutations accumulate and, upon reaching a critical threshold, lead to cancer. Tumor cells exhibit rapid, uncontrolled proliferation. Consequently, they need rapid synthesis of a vast quantity of proteins. To meet this demand, a large number of relevant genes (encompassing not only cancer-related genes but also genes involved in cellular construction and metabolic maintenance) must undergo abnormally high-speed expression. As previously shown, the more complex an organism is, the greater the variety of its genetic fences—meaning there are more "bottlenecks" on the pathway of genetic information output. For example, to produce a protein, a mammalian cell must navigate through a series of intricate steps, including the translocation of transcription factor across nuclear membrane to activate gene promoter, the decondensation of heterochromatin, histone eviction, DNA double-strand unwinding, intron splicing, and mRNA export from the nucleus followed by association with ribosomes in the cytoplasm (

Figure 2). Each of these steps is guarded by a genetic fence that restricts gene expression rate. Achieving illegal rapid expression of genes through aberrant means such as mutations is exceedingly challenging, as these interventions must accumulate to a degree sufficient to simultaneously disrupt all rate-limiting checkpoints—an event with an astronomically low probability. This principle also elucidates why it is relatively straightforward to achieve overexpression of transgenes in E. coli but significantly more arduous (e.g., transgene silencing) in mouse[

18,

19], which possess more fences. Additionally, in complex organisms, each promoter typically regulates the expression of only a single gene, while in simpler organisms, it controls a cluster. Thus, when a mutation occurs within a promoter region, the resulting impact can also be minimized in the former. This represents another tumor-suppressing mechanism.

In sum, the existence of genetic fences serves as a natural defense mechanism against cellular transformation into cancer. It accounts for why a substantial magnitude of severe genomic alterations is required to trigger carcinogenesis. In complex organisms, only a fraction of genes is actively expressed in any given cell type[

20,

21,

22], with the majority remaining in a "pre-silenced" state. Consequently, mutations have more room to activate rather than deactivate genes, thereby further accentuating the protective role of fences. The fences establish a pre-emptive firewall against carcinogenesis in every cell during early embryogenesis, unlike oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes which primarily exert regulatory effects post-development (such as during aging). Their significance is as indispensable as the air we rely on for survival, yet the unified strategy based on them for regulating biological activities, such as cancer prevention, remains unnoticed by scholars.

Permeability of the Genetic Fences

Although the genetic fences pose obstacles to the transmission of genetic information, they are not entirely impermeable. Instead, they all resemble semi-permeable membranes with adjustable permeability. For instance: nuclear membrane pores undergo expansion or contraction; introns are selectively spliced out from pre-mRNA with varying efficiencies by the spliceosomes; double-stranded DNA can further form super-helical structures or be unwound; and compressed DNA conformations, such as heterochromatinization, can be selectively loosened or tightened. Thus, the permeability of these fences is changeable. By selectively adjusting it according to different cell types, developmental stages, and pathological conditions, selective gene expression is achieved to meet specific needs in particular environments. For example, during the very early stage of blastocyst development, there is notable splicing repression[

23]. There are countless cases like this.

Notably, there are interactions between the genetic fence and gene. For instance, a certain gene may influence the expression of other genes by regulating the permeability of a fence. In turn, the genes affected may further impact that or other fences’ permeability, thereby forming positive or negative feedback loops. In short, the interactions between fence and gene are dynamic, meeting the complex biological needs for fine-tuned regulation of gene expression.

The Genetic Fences Not Only Sequester Genes But Also Protect Them

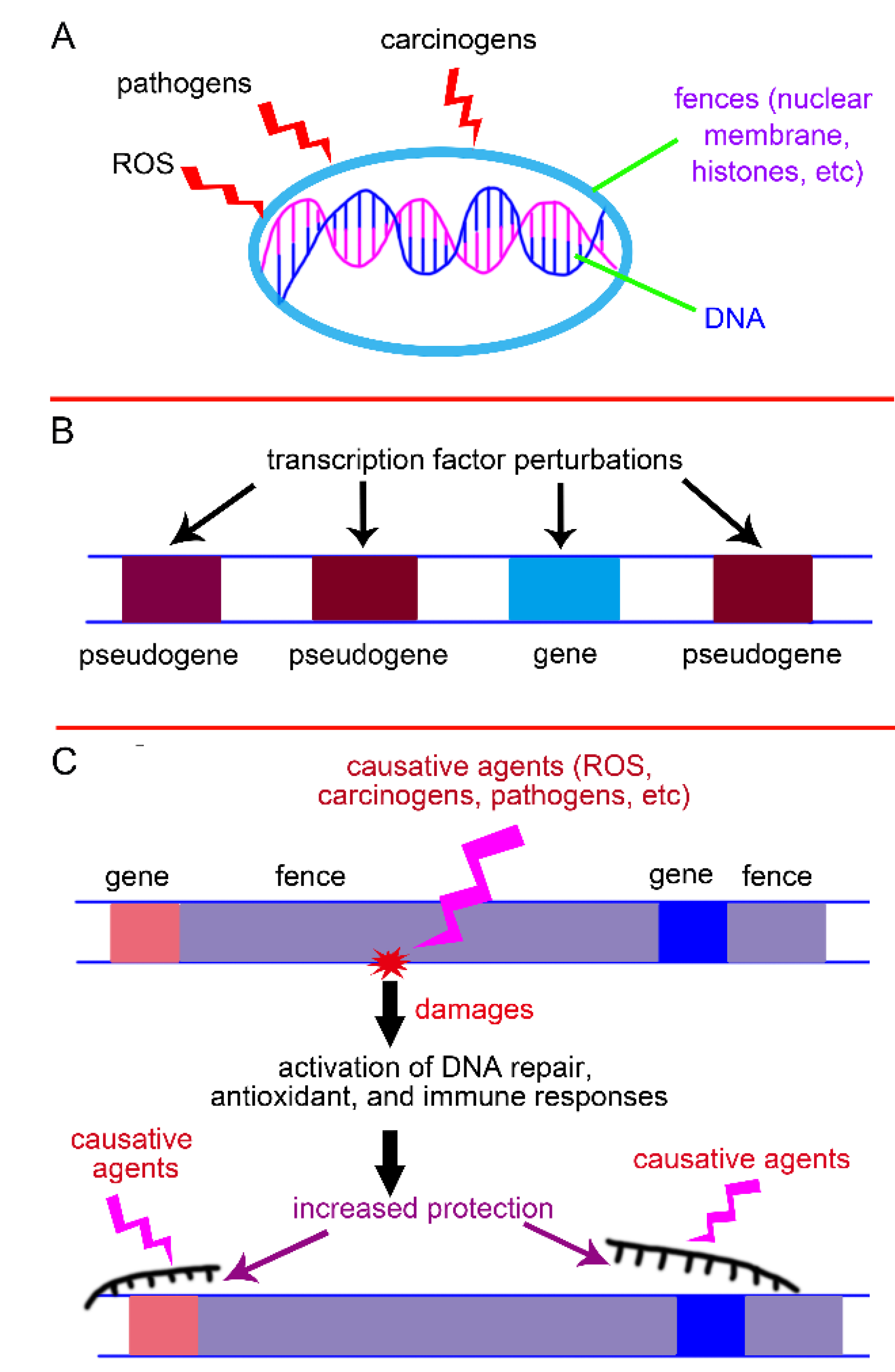

The genetic fences may protect genome from harmful factors: the nuclear membrane encloses the DNA in the nucleus, shielding it from carcinogens, pathogens, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cytoplasm; the antisense strand of a gene not only serves as a template to repair mutations that might occur in the sense strand but also protects it like clothing; DNA's supercoiling, high-order folding, and heterochromatinization morphologies wrap around genes, safeguarding them from harmful influences (

Figure 3A). These instances explain why viruses with fewer genetic fences, such as the novel coronavirus, have a much higher mutation rate[

24,

25].

Higher organisms are rich in pseudogenes. For instance, in the human genome, their number ranges from approximately 12,000 to 20,000[

26,

27,

28]. Pseudogenes generally cannot be translated into proteins [

27,

29], raising the question of their biological significance. Given that many pseudogenes exist in multiple genomic copies and their promoters are frequently bound by transcription factors[

30], it can be hypothesized that they may function as transcriptional buffers, mitigating abrupt changes in transcription factor availability when cellular homeostasis is disrupted. Consequently, this mechanism likely stabilizes the expression of corresponding authentic genes (

Figure 3B), analogous to how a car's shock absorber reduces vibrations to ensure smooth driving. In genomes of higher organisms, the fences—such as junk DNA—far exceed protein-coding sequences in proportion and are therefore more susceptible to damage by causative agents (e.g., ROS, carcinogens, pathogens). Consequently, early warning signals should be triggered to protect protein-coding regions in advance (

Figure 3C).

In short, the genetic fences may shield gene-coding regions from harmful factors like an umbrella, buffer abnormal fluctuations in gene expression, and send early warning signals when damaged.

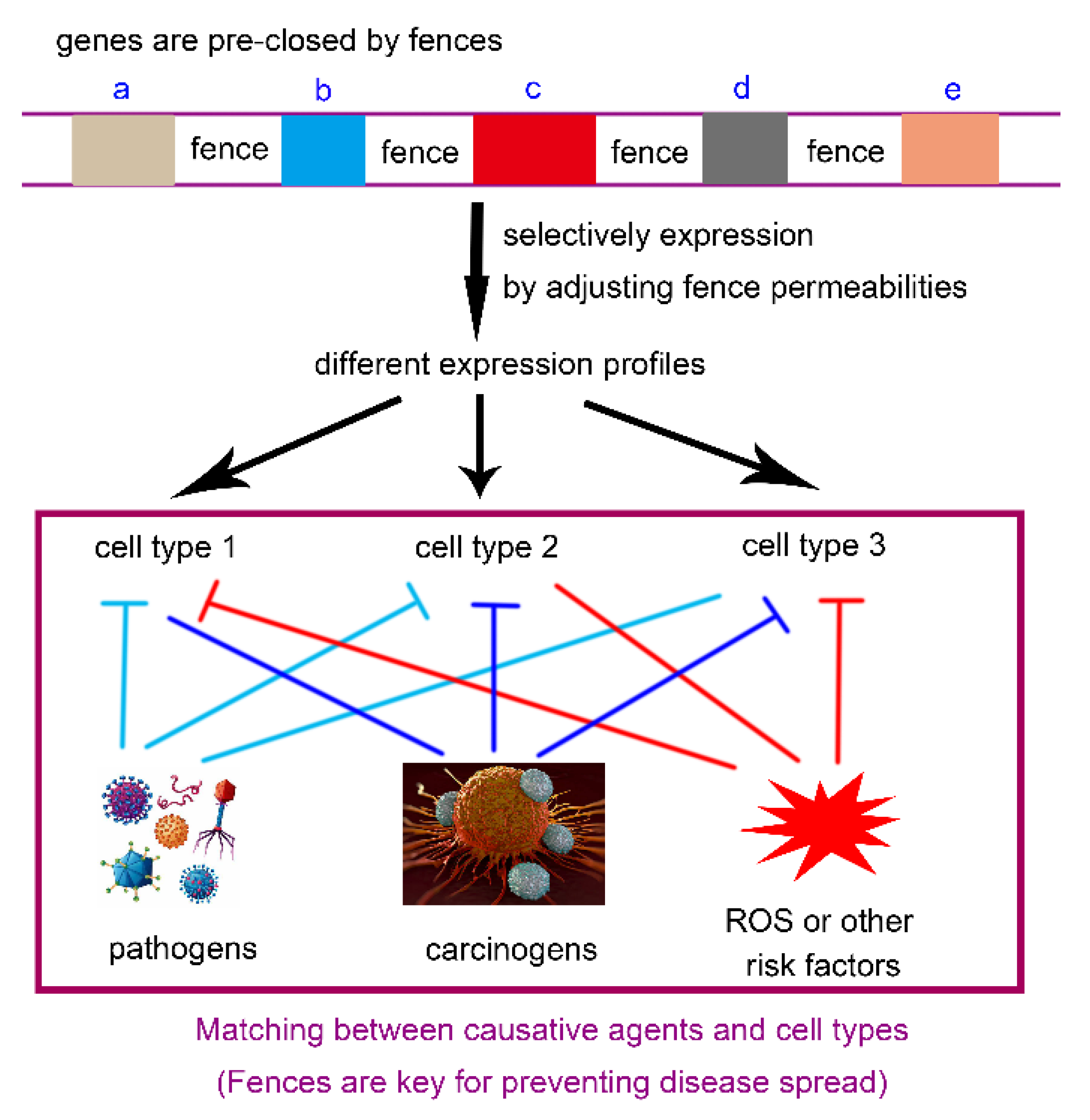

The Genetic Fences Are Key for Preventing the Spread of Diseases

Complex organisms are composed of countless cells, and it is crucial to prevent the transmission of diseases, such as viral infections, among them. The heterogeneity between cell types helps avoid the situation where "one piece of rat droppings ruins a whole pot of soup." The reason why COVID-19 primarily infects human lung tissues is that they have the target site, namely the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), for the virus's spike protein to bind[

31,

32]. Other tissues hardly express that target, thus are less affected. Therefore, preventing the spread of diseases among tissues should represent one of the critical significances of selective gene expression and cell differentiation. However, we must not overlook that the pre-emptive silencing of genes by fences serves as the foundational mechanism underlying all these processes.

Not only do different tissues exhibit varying sensitivities to viral infections. Expanding on this, different tissues, individuals, and species also demonstrate distinct sensitivities to a variety of causative factors (such as pathogens like viruses, bacteria, and fungi; carcinogens; and reactive oxygen species), toxins, and drugs. For instance: some individuals develop severe symptoms after COVID-19 infection, while others remain asymptomatic; COVID-19 has a significant impact on humans but exerts only a minimal effect on other animals; aflatoxin, a potent carcinogen, primarily induces liver cancer and has a much lower likelihood of causing cancers in other tissues; different individuals exhibit varying sensitivities to the same carcinogen or toxin; and different patients may experience differences in both the therapeutic effects and adverse reactions after taking the same medication. There are numerous similar examples.

Causative factors, toxins, and drugs often exert their effects by matching and binding to specific receptors on the cell membrane. However, the expression levels of these receptors vary among tissues, individuals, and species, contributing to diverse outcomes. Namely, there exists a selective matching between harmful factors and cell types with distinct expression profiles (

Figure 4). Taking the tissue-specific differences in cancer occurrence as an example: the VHL gene mutation is responsible for the human clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), but not for cancer in other tissues[

33,

34]; the SOX10 gene is mainly essential for the survival and proliferation of melanoma cells[

35,

36]; the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are primarily associated with breast and ovarian cancers, though they may also influence the risk of other malignancies to a lesser extent[

37,

38].

In short, for species that are closely related, the varying responses to causative factors, toxins, and drugs are mainly caused by differences in receptor expression. For species with more distant relationships, differences in both the molecular structure and expression levels of receptors likely work together to produce these effects. Fundamentally, the distribution and permeability of the genetic fences are responsible for the disparities in protein expression profiles, particularly those of cell membrane receptors. The fences thus sequester risk factors locally, preventing the situation where "one piece of rat droppings ruins a whole pot of soup."

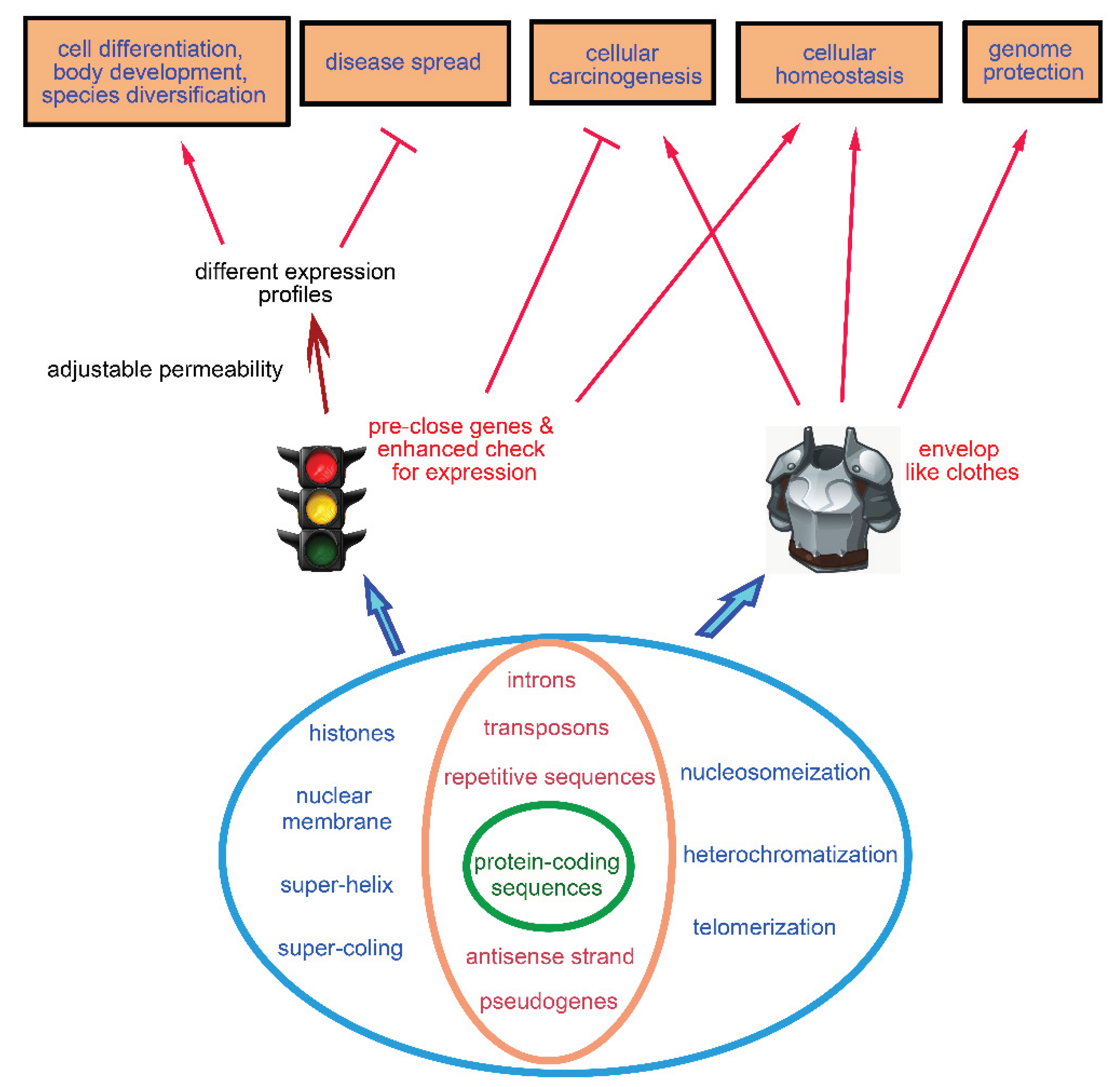

Classification of the Genetic Fences

Here, we classify them into two categories. Those composed entirely of ribonucleotides or deoxyribonucleotides are referred to as the internal genetic fences. Examples include introns, repetitive sequences, transposons, pseudogenes, telomeres, and the antisense strand of genes (

Figure 5). In comparison to prions, the entire DNA/RNA genomes in viruses and higher organisms also act as internal fences.

The others are classified as the external genetic fences, including nuclear membrane, histones, as well as the compacted "morphologies" of DNA-protein complexes such as double-helix, super-coiling, nucleosomeization, and heterochromatinization (

Figure 5).

In sum, these genetic fences are like inner and outer garments wrapping around protein-coding segments.

Discussion

Genes have always been a key focus of biological research. They can be likened to independent small balls, each possessing its own unique function. This paper describes a container that holds them—the genetic fence. The fence has a certain degree of permeability, allowing certain genes to be released when necessary. Scholars are already well-acquainted with structures or morphologies such as the nuclear envelope, histones, introns, repetitive sequences, heterochromatin, and DNA’s supercoiling. However, they have traditionally been viewed as relatively independent from each other. Nevertheless, this paper groups them under a single concept, namely the genetic fence. The fences become more complex as the organismal complexity increases. In humans, each cell type expresses only a small fraction of the genome's ~20,000 genes, with the vast majority remaining permanently silenced. While in lower organisms such as nematodes, a higher proportion of genes should be expressed per cell type. Because they have limited cell counts. Thus, we can deduce a general pattern: the more complex an organism, the lower the average proportion of genes "capable" of being expressed in its individual cell types. It follows that complex organisms have a greater need to pre-silence genes, explaining why they possess more genetic fences. In any case, the fence is a prerequisite for the formation of stable and diverse gene expression profiles, which in turn serve as the cornerstone for cell differentiation, organism development, and species diversification.

The fence acts as a water stop valve, allowing cells to stably prevent irrelevant genes—water that doesn't belong to them—from flooding their respective "homes." In other words, it effectively prevents random gene expressions, especially when the number is large. It's just like how red lights regulate traffic flow when there are too many vehicles. Moreover, as semi-permeable checkpoints, they should also be capable of stabilizing the expression of genes that are permitted to be expressed. Namely, maintain the status quo. In sum, they should play crucial roles in protecting cellular homeostasis.

As organismal aging intensifies, cellular homeostasis and gene expression patterns gradually become aberrant. Particularly under the influence of mutagenic agents, this dysregulation may trigger malignant transformation. Tumor cells exhibit hyperactive growth and proliferation, a phenotype sustained by the ultrarapid synthesis of vast quantities of proteins. Any illegal expression through mutations would necessitate breaking through all the fences along the genetic information flowing pathway—such as increasing nuclear membrane permeability, loosening heterochromatin regions, unwinding double-stranded DNA, and activating splicing complexes. Simultaneously opening all these rate-limiting steps is an extremely low-probability event. Therefore, the fence undoubtedly plays a fundamental role in pre-suppressing cancer (

Figure 5). For advanced organisms, this is of great significance. Since they have a vast number and a wide variety of cell types, even the carcinogenesis of a small portion can cause the collapse of the entire body. This also explains, from another perspective, why their genomes contain a higher proportion of fences (such as junk DNA).

Fences, akin to umbrellas (or underwear and outerwear), also shield the protein-coding regions from harmful factors, thereby reducing the mutation rate. Given their higher proportion in the genome (such as non-coding sequences), they can issue early warnings when damaged, aiding in the timely activation of defense mechanisms. Pseudogenes often exist in multiple copies, possess promoters, and are capable of binding transcription factors. Therefore, they should be able to buffer fluctuations caused by the deterioration of internal and external environments, thereby maintaining stable expression of authentic genes. This is analogous to how automotive shock absorbers mitigate bumps when driving on uneven roads.

Various causative factors, toxins, and drugs typically exert their effects by binding to specific receptors on the cell membrane. The fences confer cell-, tissue-, individual-, and species-specific expression patterns to these receptors, thereby localizing the detrimental effects (such as diseases) and preventing the collapse of the entire system (

Figure 5). Take SARS-CoV-2 and HIV as examples: these viruses can infect cells only if the cells display specific proteins on their surface (e.g., ACE2 for SARS-CoV-2, CD4 for HIV). There are numerous similar examples. In any way, the restriction on disease spread and the differentiated responses to causative agents, toxins, and drugs at the cellular, tissue, individual, and species levels, are closely related to differential distribution and varying permeability of the fences.

From viruses, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, mice, all the way to humans, the complexity of body structure progressively increases, manifesting as an increase in cell types and continuous differentiation of tissues and organs. It has long been believed that this is closely related to the growth in the number of genes and the involvement of certain regulatory proteins. However, nematodes have nearly the same number of genes as humans, both around twenty thousand. Yet, the human body structure is far more sophisticated. This suggests that relying solely on genes, particularly regulatory genes, may not be sufficient to explain this complexity. When nature first designed the biological world, it must have also adopted other strategies, or rather, non-genetic implementation plans. As shown in this paper, it is performed through the genetic fences. The sequential emergence of seemingly independent structures such as RNA, DNA with its double-stranded, supercoiled, and folded configurations, repetitive sequences, introns, pseudogenes, the nuclear membrane, histones, and heterochromatinization represents the continuous deepening of this underlying strategy. Their commonality lies in acting like checkpoints that impose multiple barriers to the transmission of genetic information. This strategy differs from the bidirectional regulatory mode employed by regulatory proteins—which can both activate and repress gene expression. Instead, it represents a unidirectional inhibitory approach. It is worth noting that genetic information is not synonymous with genes; while genes serve as one carrier of genetic information, they are not the sole carrier. For instance, the protein structure of prions can also carry genetic information and replicate it. Strictly speaking, the Central Dogma of genetics represents a manifestation of the fencing strategy, where DNA/RNA act as kinds of fences. From prions to humans, this strategy is consistent.

Setting up multiple layers of obstacles along the transmission pathway of genetic information and then selectively opening them for gene expression on an individual basis may seem like creating unnecessary trouble. However, considering that complex organisms possess hundreds or thousands of cell types, adopting a uniform strategy of pre-emptively shutting down genes across all cells must be a highly cost-effective regulatory approach.

As a mechanical structure, the fence is far more stable in its gene water stop valve function than implementation through "regulatory proteins." Pre-embedding various types of fences along the transmission pathway of genetic information represents nature's ingenious strategy for regulating life activities. This study aids in understanding how living organisms are designed from the original principles.

Author Contributions

Yaguang R. conceived the concept and wrote the manuscript. Jingyu L. contributed to data collection, image editing, and manuscript writing.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 20202BAB216023), and Project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (No.190922).

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Clamp, M.; et al. Distinguishing protein-coding and noncoding genes in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1943; -3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, P.; et al. The status of the human gene catalogue. ArXiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kritika, C. Transforming 'Junk' DNA into Cancer Warriors: The Role of Pseudogenes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Diagn Progn. [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, A. F. & Gregory, T. R. The case for junk DNA. PLoS Genet. [CrossRef]

- McNally, F. J. Competing chromosomes explain junk DNA. Science. [CrossRef]

- Orozco, G. , Schoenfelder, S., Walker, N., Eyre, S. & Fraser, P. 3D genome organization links non-coding disease-associated variants to genes. Front Cell Dev Biol. [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, V.; et al. The role of retrotransposable elements in ageing and age-associated diseases. Nature, -53. [CrossRef]

- Brandler, W. M.; et al. Paternally inherited cis-regulatory structural variants are associated with autism. Science. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; et al. Machine learning enables pan-cancer identification of mutational hotspots at persistent CTCF binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res, 8099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacisin, M. , Espinosa-Cantu, A. & Bollenbach, T. Intron-mediated induction of phenotypic heterogeneity. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Modzelewski, A. J.; et al. A mouse-specific retrotransposon drives a conserved Cdk2ap1 isoform essential for development. Cell, 5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. & Rao, Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Blattner, F. R.; et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goormans, A. R.; et al. Comprehensive study on Escherichia coli genomic expression: Does position really matter? Metab Eng. [CrossRef]

- Goffeau, A.; et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; et al. From Saccharomyces cerevisiae to human: The important gene co-expression modules. Biomed Rep. [CrossRef]

- Hobert, O. The neuronal genome of Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, A.; et al. The sound of silence: Transgene silencing in mammalian cell engineering. Cell Syst. [CrossRef]

- Calero-Nieto, F. J. , Bert, A. G. & Cockerill, P. N. Transcription-dependent silencing of inducible convergent transgenes in transgenic mice. Epigenetics Chromatin. [CrossRef]

- Ito, K. , Hirakawa, T., Shigenobu, S., Fujiyoshi, H. & Yamashita, T. Mouse-Geneformer: A deep learning model for mouse single-cell transcriptome and its cross-species utility. PLoS Genet. [CrossRef]

- Arduini, A.; et al. Transcriptional profile of the rat cardiovascular system at single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; et al. Proteoform profiling of endogenous single cells from rat hippocampus at scale. Nat Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; et al. Capturing totipotency in human cells through spliceosomal repression. Cell, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. Z. I.; et al. An overview of viral mutagenesis and the impact on pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Front Immunol, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, J.; et al. The mutational landscape of SARS-CoV-2 provides new insight into viral evolution and fitness. Nat Commun. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; et al. Pseudogene-mediated DNA demethylation leads to oncogene activation. Sci Adv, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmena, L. Pseudogenes: Four Decades of Discovery. Methods Mol Biol 2324, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrents, D. , Suyama, M., Zdobnov, E. & Bork, P. A genome-wide survey of human pseudogenes. Genome Res. [CrossRef]

- Poliseno, L. Pseudogenes: newly discovered players in human cancer. Sci Signal. [CrossRef]

- Bok, I. & Karreth, F. A. Strategies to Study the Functions of Pseudogenes in Mouse Models of Cancer. Methods Mol Biol 2324, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, S.; et al. The Renin-Angiotensin System Modulates SARS-CoV-2 Entry via ACE2 Receptor. Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Colyer, A.; et al. Allostery Links hACE2 Binding, Pan-variant Neutralization and Helical Extension in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. J Mol Biol, 9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; et al. Tumor heterogeneity in VHL drives metastasis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. [CrossRef]

- Arulraj, K.; et al. Impact of heavy metals, oxidative stress, expression of VHL, and antioxidant genes in the pathogenesis of renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol, e28. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, S. R.; et al. SOX10 requirement for melanoma tumor growth is due, in part, to immune-mediated effects. Cell Rep. [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; et al. SOX10, MITF, and microRNAs: Decoding their interplay in regulating melanoma plasticity. Int J Cancer, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohori, S.; et al. Hidden SVA retrotransposon insertion in BRCA1 revealed by nanopore targeted sequencing causes hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Hum Genet. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; et al. Human iPSC-based breast cancer model identifies S100P-dependent cancer stemness induced by BRCA1 mutation. Sci Adv, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The fence poses an obstacle to gene expression. (A) Double-stranded DNA is shown as an example. The presence of negative strand is akin to having an additional fence. By firstly unwinding it, selective gene expression can be achieved. (B) For comparison, the genomes of some simple viruses consist of single-stranded RNA, which can directly serve as a template for translation. This eliminates the need for the unwinding process and also skips the transcription step. However, it makes selective gene expression difficult to achieve. (C) In simple organisms such as bacteria, fungi, and nematodes, genes are often expressed in a bundled manner, forming operon structures. The expression of gene 1 drives the co-expression of gene 2, or vice versa, exhibiting a sort of "hitchhiking" behavior. (D) In mice and humans, the insertion of extensive non-coding regions (known as junk DNA) disrupts this gene bundling. Each gene must now have its promoter pre-activated to initiate expression. Although this eliminates the gene hitchhiking phenomenon and makes expression more challenging, it enhances the flexibility and autonomy of gene expression, facilitating proportional combinations and thereby enriching the gene expression profiles and increasing cellular diversities.

Figure 1.

The fence poses an obstacle to gene expression. (A) Double-stranded DNA is shown as an example. The presence of negative strand is akin to having an additional fence. By firstly unwinding it, selective gene expression can be achieved. (B) For comparison, the genomes of some simple viruses consist of single-stranded RNA, which can directly serve as a template for translation. This eliminates the need for the unwinding process and also skips the transcription step. However, it makes selective gene expression difficult to achieve. (C) In simple organisms such as bacteria, fungi, and nematodes, genes are often expressed in a bundled manner, forming operon structures. The expression of gene 1 drives the co-expression of gene 2, or vice versa, exhibiting a sort of "hitchhiking" behavior. (D) In mice and humans, the insertion of extensive non-coding regions (known as junk DNA) disrupts this gene bundling. Each gene must now have its promoter pre-activated to initiate expression. Although this eliminates the gene hitchhiking phenomenon and makes expression more challenging, it enhances the flexibility and autonomy of gene expression, facilitating proportional combinations and thereby enriching the gene expression profiles and increasing cellular diversities.

Figure 2.

Complex organisms have more types of fences to help maintain cellular homeostasis and prevent carcinogenesis. Fences act as checkpoints to prevent indiscriminate expression of genes, thus reduce expression noise and maintain cellular homeostasis. The multiple checkpoints also block and slow down the illegitimate expression of genes triggered by carcinogenic factors, thereby helping to prevent cancer. (Steps highlighted in purple represent incremental procedures).

Figure 2.

Complex organisms have more types of fences to help maintain cellular homeostasis and prevent carcinogenesis. Fences act as checkpoints to prevent indiscriminate expression of genes, thus reduce expression noise and maintain cellular homeostasis. The multiple checkpoints also block and slow down the illegitimate expression of genes triggered by carcinogenic factors, thereby helping to prevent cancer. (Steps highlighted in purple represent incremental procedures).

Figure 3.

Protective roles of the genetic fences. (A) They directly protect genes like umbrellas. (B) Fences such as pseudogenes can buffer against gene expression perturbations. (C) In genomes of higher organisms, the proportion of fences (e.g., junk DNA) far exceeds that of coding sequences. The fences may act as early warning systems when damaged, thereby protecting the coding sequences in advance.

Figure 3.

Protective roles of the genetic fences. (A) They directly protect genes like umbrellas. (B) Fences such as pseudogenes can buffer against gene expression perturbations. (C) In genomes of higher organisms, the proportion of fences (e.g., junk DNA) far exceeds that of coding sequences. The fences may act as early warning systems when damaged, thereby protecting the coding sequences in advance.

Figure 4.

The genetic fences prevent the spread of diseases. Causative agents (pathogens, carcinogens, ROS, etc.) typically initiate infection by binding to specific receptors on the cell membrane. Namely, there is a selective matching between them. However, such receptors are not universally expressed across all cell types. So, the agents can only infect cells with high expression of the corresponding receptors. If a tissue does not express such receptor, it will not be affected. Therefore, the diseases are sealed locally, preventing systemic collapse of the entire individual or species. Fundamentally, the fence-mediated pre-silencing of genes plays a critical role, as only through pre-silencing can selective activation be achieved (via permeability modulation).

Figure 4.

The genetic fences prevent the spread of diseases. Causative agents (pathogens, carcinogens, ROS, etc.) typically initiate infection by binding to specific receptors on the cell membrane. Namely, there is a selective matching between them. However, such receptors are not universally expressed across all cell types. So, the agents can only infect cells with high expression of the corresponding receptors. If a tissue does not express such receptor, it will not be affected. Therefore, the diseases are sealed locally, preventing systemic collapse of the entire individual or species. Fundamentally, the fence-mediated pre-silencing of genes plays a critical role, as only through pre-silencing can selective activation be achieved (via permeability modulation).

Figure 5.

Classification of the fences and summary of their common roles. The fences are categorized into internal and external types. They proactively silence genes and increase the number of checkpoints along their expression pathways. This helps prevent aberrant gene activation, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis and suppressing carcinogenesis. By modulating the permeability of the fences, the expression of specific genes is allowed, which serves as a prerequisite for cellular differentiation, organism development, and biodiversity. Additionally, with the help of fences, the establishment of distinct gene expression profiles across cell types is responsible for preventing disease transmission across cellular, tissue, individual, and interspecies boundaries.

Figure 5.

Classification of the fences and summary of their common roles. The fences are categorized into internal and external types. They proactively silence genes and increase the number of checkpoints along their expression pathways. This helps prevent aberrant gene activation, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis and suppressing carcinogenesis. By modulating the permeability of the fences, the expression of specific genes is allowed, which serves as a prerequisite for cellular differentiation, organism development, and biodiversity. Additionally, with the help of fences, the establishment of distinct gene expression profiles across cell types is responsible for preventing disease transmission across cellular, tissue, individual, and interspecies boundaries.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).