Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Blood Pressure

Renin-Angiotensin Aldosterone System:

What Leads to an Increase in Aldosterone?

Inflammation

RAAS and Inflammation

Role of Obesity and Metabolic Parameters

Clinical Relevance

Brain Imaging Studies

The Role of Childhood Trauma

Possible Therapeutic Interventions

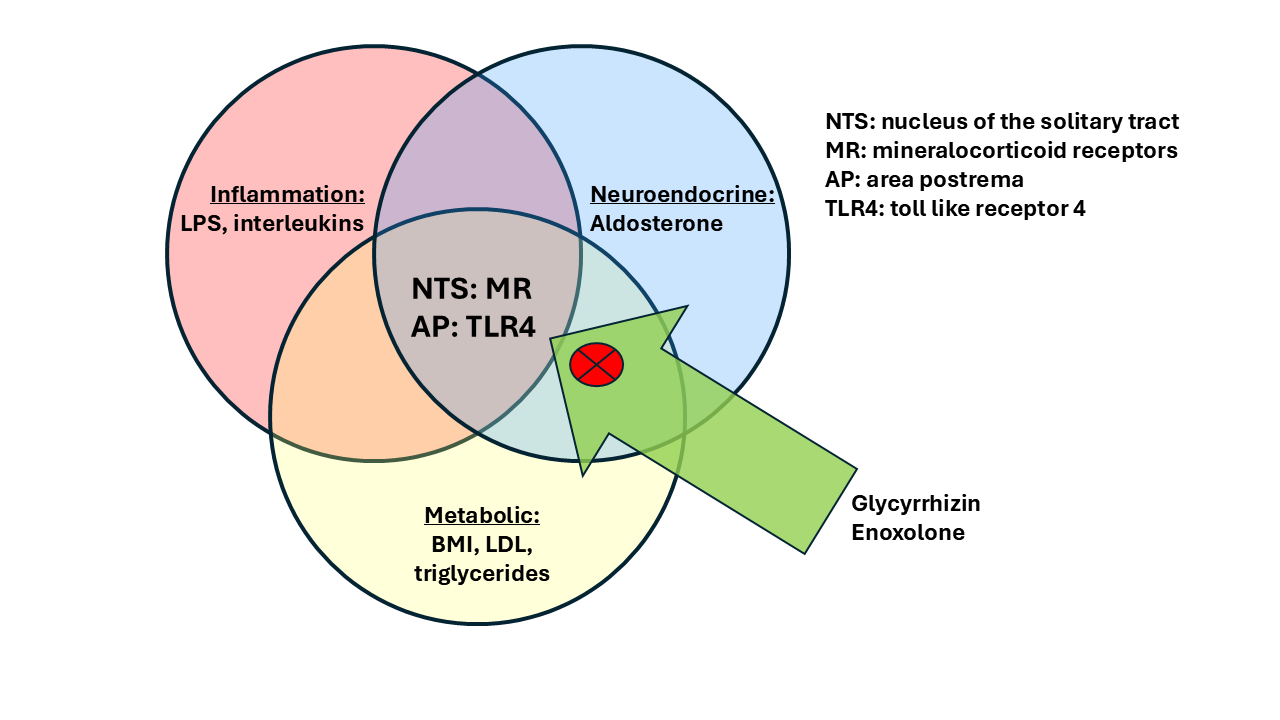

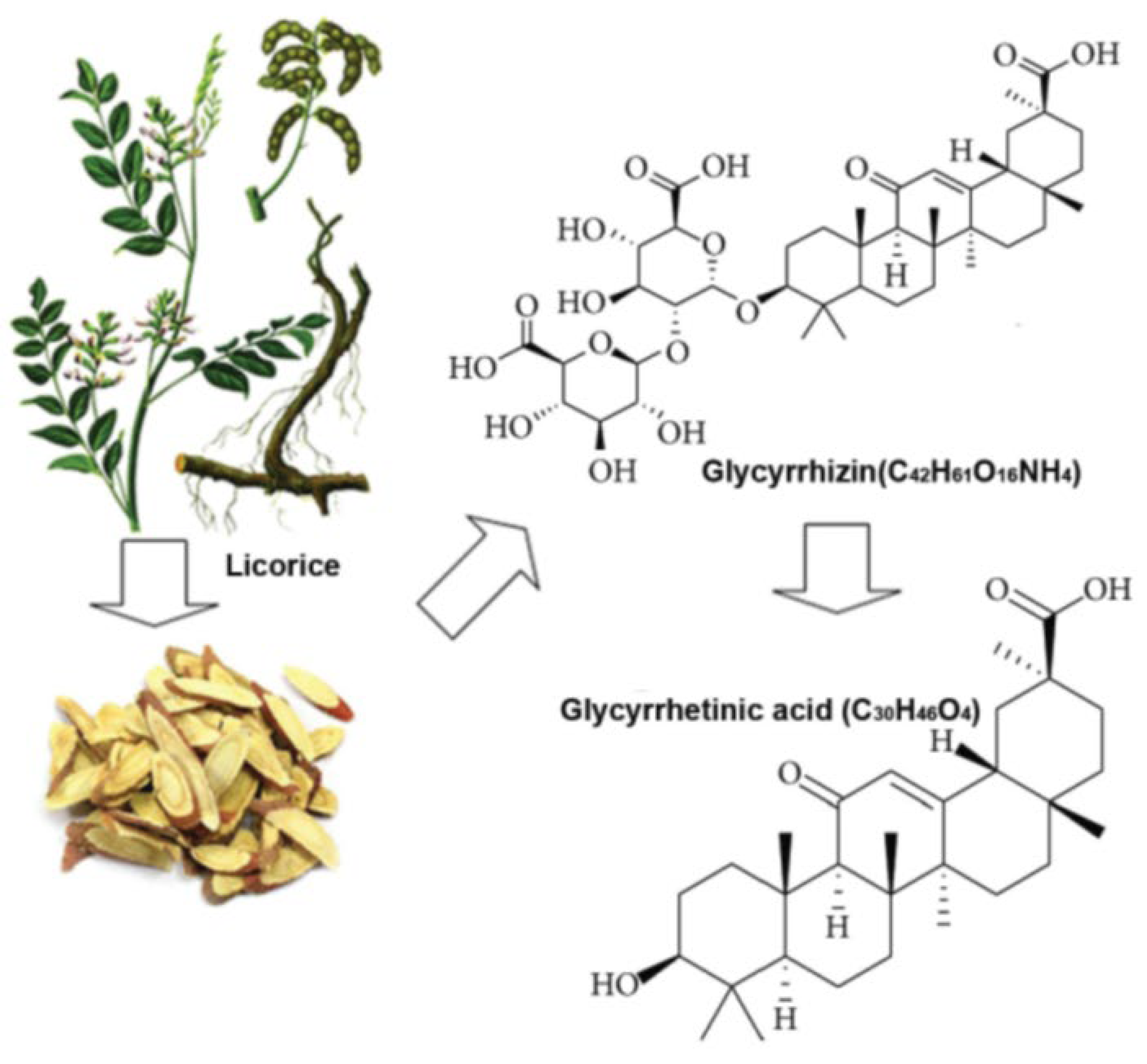

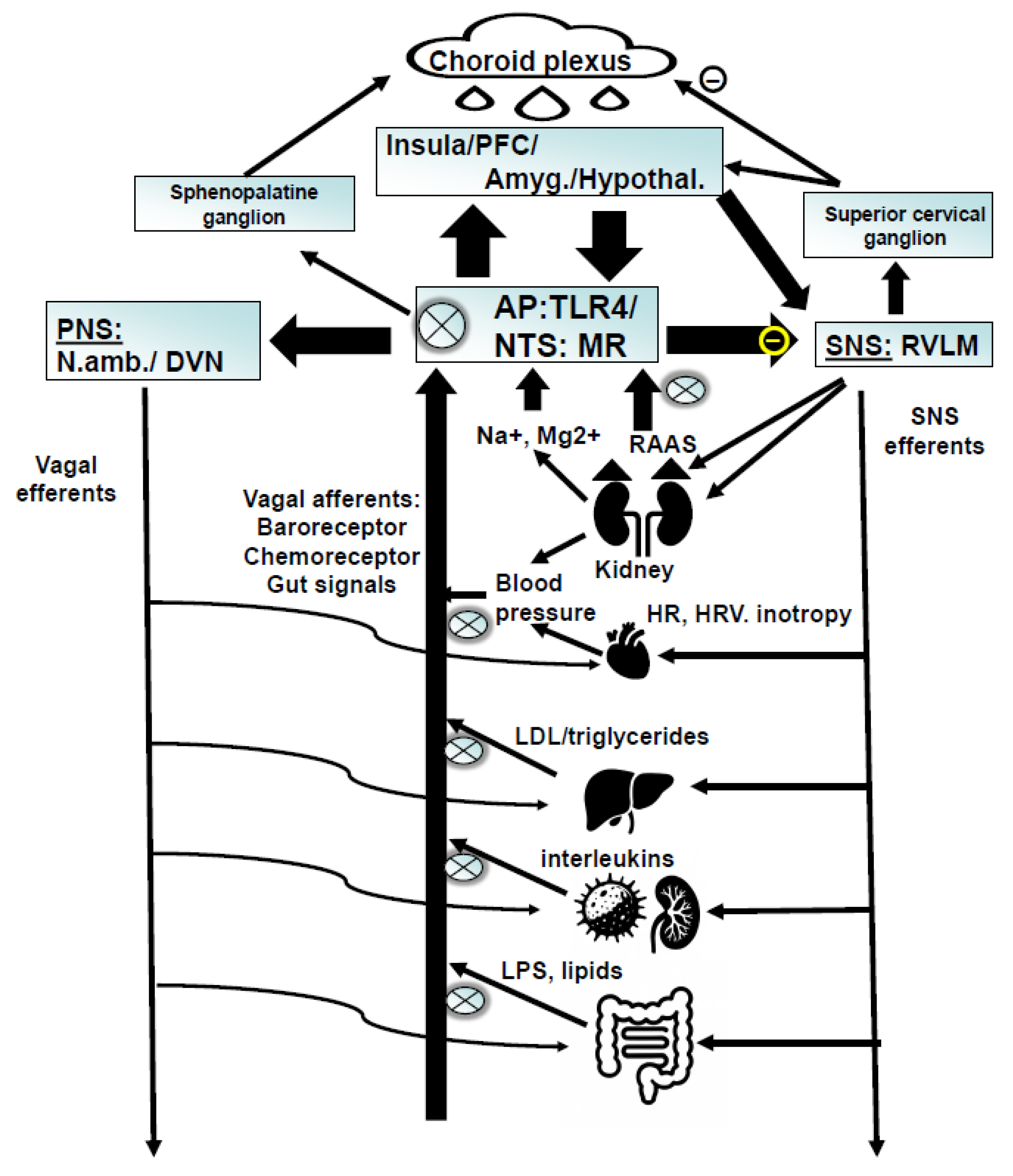

Glycyrrhizin/Enoxolone

Glycyrrhizin Reduces Aldosterone via Inhibition of the 11betaHSD2

Glycyrrhizin Reduces Inflammation via TLR4 Inhibition

Behavioral Effects of Glycyrrhizin/Enoxolone

Effect of Glycyrrhizin/Enoxolone on Metabolic Parameters

Glycyrrhizin Reverses Catecholamine Depletion – Autonomic Activity as Primary Driver?

Clinical Studies:

Limitation

Conclusion

References

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Warden, D.; Ritz, L.; Norquist, G.; Howland, R.H.; Lebowitz, B.; McGrath, P.J. , et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006, 163, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Rush, A.J.; Alpert, J.E.; Balasubramani, G.K.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Carmin, C.N.; Biggs, M.M.; Zisook, S.; Leuchter, A.; Howland, R. , et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2008, 165, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.W.; McGrath, P.J.; Fava, M.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Zisook, S.; Cook, I.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Trivedi, M.H.; Balasubramani, G.K.; Warden, D. , et al. Do atypical features affect outcome in depressed outpatients treated with citalopram? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H. Atypical depression spectrum disorder - neurobiology and treatment. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2003, 15, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, F.; Bot, M.; Jansen, R.; Chan, M.K.; Cooper, J.D.; Bahn, S.; Penninx, B.W. Serum proteomic profiles of depressive subtypes. Transl Psychiatry 2016, 6, e851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, F.; Vogelzangs, N.; Merikangas, K.R.; de Jonge, P.; Beekman, A.T.; Penninx, B.W. Evidence for a differential role of HPA-axis function, inflammation and metabolic syndrome in melancholic versus atypical depression. Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Lamers, F.; Berk, M.; Penninx, B. Depression Heterogeneity and Its Biological Underpinnings: Toward Immunometabolic Depression. Biol Psychiatry 2020, 88, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, P.W.; Wong, M.L. Re-assessing the catecholamine hypothesis of depression: the case of melancholic depression. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6121–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.L.; Kling, M.A.; Munson, P.J.; Listwak, S.; Licinio, J.; Prolo, P.; Karp, B.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Geracioti, T.D., Jr.; DeBellis, M.D. , et al. Pronounced and sustained central hypernoradrenergic function in major depression with melancholic features: relation to hypercortisolism and corticotropin-releasing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkraut, J.J. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. Am J Psychiatry 1965, 122, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorell, L.H. Valid electrodermal hyporeactivity for depressive suicidal propensity offers links to cognitive theory. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009, 119, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, N.G.; Doerr, H.O.; Storrie, M.C. Skin conductance: a potentially sensitive test for depression. Psychiatry Res 1983, 10, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestanikova, A.; Ondrejka, I.; Mestanik, M.; Hrtanek, I.; Snircova, E.; Tonhajzerova, I. Electrodermal Activity in Adolescent Depression. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016, 935, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, A.Z.; Rondon, M.U.; Trombetta, I.C.; Laterza, M.C.; Azul, J.B.; Pullenayegum, E.M.; Scalco, M.Z.; Kuniyoshi, F.H.; Wajngarten, M.; Negrao, C.E. , et al. Muscle sympathetic nervous activity in depressed patients before and after treatment with sertraline. J Hypertens 2009, 27, 2429–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, A.Z.; Scalco, M.Z.; Azul, J.B.; Lotufo Neto, F. Hypertension and depression. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2005, 60, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R.C.; Pencina, M.J.; Barrentine, L.W.; Ruiz, J.A.; Fava, M.; Zajecka, J.M.; Papakostas, G.I. Association of obesity and inflammatory marker levels on treatment outcome: results from a double-blind, randomized study of adjunctive L-methylfolate calcium in patients with MDD who are inadequate responders to SSRIs. J Clin Psychiatry 2015, 76, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreijling, S.R.; Chin Fatt, C.R.; Williams, L.M.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Usherwood, T.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Rush, A.J.; Uher, R.; Aitchison, K.J.; Kohler-Forsberg, O. , et al. Features of immunometabolic depression as predictors of antidepressant treatment outcomes: pooled analysis of four clinical trials. Br J Psychiatry 2024, 224, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.; Lamers, F.; Jansen, R.; Berk, M.; Khandaker, G.M.; De Picker, L.; Milaneschi, Y. Immuno-metabolic depression: from concept to implementation. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2025, 48, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, C.M.; de Geus, E.J.; Penninx, B.W. Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system predicts the development of the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 2484–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelzangs, N.; Duivis, H.E.; Beekman, A.T.; Kluft, C.; Neuteboom, J.; Hoogendijk, W.; Smit, J.H.; de Jonge, P.; Penninx, B.W. Association of depressive disorders, depression characteristics and antidepressant medication with inflammation. Transl Psychiatry 2012, 2, e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licht, C.M.; de Geus, E.J.; Seldenrijk, A.; van Hout, H.P.; Zitman, F.G.; van Dyck, R.; Penninx, B.W. Depression is associated with decreased blood pressure, but antidepressant use increases the risk for hypertension. Hypertension 2009, 53, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D. Depressive symptoms and blood pressure. Journal of Psychophysiology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildrum, B.; Mykletun, A.; Stordal, E.; Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Holmen, J. Association of low blood pressure with anxiety and depression: the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007, 61, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaare, H.L.; Blochl, M.; Kumral, D.; Uhlig, M.; Lemcke, L.; Valk, S.L.; Villringer, A. Associations between mental health, blood pressure and the development of hypertension. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup-Benham, C.A.; Markides, K.S.; Black, S.A.; Goodwin, J.S. Relationship between low blood pressure and depressive symptomatology in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000, 48, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.L.; Sheth, A.; Shin, J.; Pairman, J.; Wilton, K.; Burt, J.A.; Jones, D.E. Lower ambulatory blood pressure in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med 2009, 71, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halls Dally, J.F. Nervous exhaustion and low blood pressure. The British Medial Journal 1925, 634–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Meyer, T.; Bosbach, A.; Chavanon, M.L.; Hassoun, L.; Edelmann, F.; Wachter, R. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations of Systolic Blood Pressure With Quality of Life and Depressive Mood in Older Adults With Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Results From the Observational DIAST-CHF Study. Psychosom Med 2018, 80, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendes, A.; Meyer, T.; Hulpke-Wette, M.; Herrmann-Lingen, C. Association of elevated blood pressure with low distress and good quality of life: results from the nationwide representative German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents. Psychosom Med 2013, 75, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassoun, L.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Hapke, U.; Neuhauser, H.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Meyer, T. Association between chronic stress and blood pressure: findings from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults 2008-2011. Psychosom Med 2015, 77, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, B.R.; Filewich, R.J.; Miller, N.E.; Craigmyle, N.; Pickering, T.G. Baroreceptor activation reduces reactivity to noxious stimulation: implications for hypertension. Science 1979, 205, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, H.; Elbert, T. Psychophysiology of arterial baroreceptors and the etiology of hypertension. Biological psychology 2001, 57, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.W.; Chang, Y.; Lim, S.W.; Cho, J.; Kim, H.N.; Kim, K.B.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, D.W.; Oh, K.S. , et al. Bidirectional association between blood pressure and depressive symptoms in young and middle-age adults: A cohort study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2020, 29, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.S.; Berntson, J.; Polanka, B.M.; Stewart, J.C. Cardiovascular Risk Factors as Differential Predictors of Incident Atypical and Typical Major Depressive Disorder in US Adults. Psychosom Med 2018, 80, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, M.; Jezova, D.; Greene, B.; Konrad, C.; Kircher, T.; Murck, H. Target-based biomarker selection - Mineralocorticoid receptor-related biomarkers and treatment outcome in major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2015, 66-67, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, J.; Murck, H.; Wagner, S.; Zillich, L.; Streit, F.; Herzog, D.P.; Braus, D.F.; Tadic, A.; Lieb, K.; Muller, M.B. Routinely accessible parameters of mineralocorticoid receptor function, depression subtypes and response prediction: a post-hoc analysis from the early medication change trial in major depressive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppino, F.S.; Bouvy, P.F.; Giltay, E.J.; Penninx, B.W.; Zitman, F.G. The metabolic syndrome and related characteristics in major depression: inpatients and outpatients compared: metabolic differences across treatment settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014, 36, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunbul, M.; Sunbul, E.A.; Kosker, S.D.; Durmus, E.; Kivrak, T.; Ileri, C.; Oguz, M.; Sari, I. Depression and anxiety are associated with abnormal nocturnal blood pressure fall in hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens 2014, 36, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Fu, S.; Ren, J.; Luo, L. Poor sleep is responsible for the impaired nocturnal blood pressure dipping in elderly hypertensive: A cross-sectional study of elderly. Clin Exp Hypertens 2018, 40, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, K.; Yamanaka, G.; Oinuma, S.; Kikichi, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Otsuka, K.; Cornelissen, G. Even mild depression is associated with among-day blood pressure variability, including masked non-dipping assessed by 7-d/24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Clin Exp Hypertens 2015, 37, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederbogen, F.; Gernoth, C.; Hamann, B.; Kniest, A.; Heuser, I.; Deuschle, M. Circadian blood pressure regulation in hospitalized depressed patients and non-depressed comparison subjects. Blood Press Monit 2003, 8, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.T.; Huang, C.C. Midodrine hydrochloride in patients on hemodialysis with chronic hypotension. Ren Fail 1996, 18, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medow, M.S.; Stewart, J.M.; Sanyal, S.; Mumtaz, A.; Sica, D.; Frishman, W.H. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of orthostatic hypotension and vasovagal syncope. Cardiol Rev 2008, 16, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracie, J.; Newton, J.L.; Norton, M.; Baker, C.; Freeston, M. The role of psychological factors in response to treatment in neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) syncope. Europace 2006, 8, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C.; Hinkelmann, K.; Moritz, S.; Yassouridis, A.; Jahn, H.; Wiedemann, K.; Kellner, M. Modulation of the mineralocorticoid receptor as add-on treatment in depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proof-of-concept study. J Psychiatr Res 2010, 44, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowska, J.; Ozhog, S.; Smith, E.; Perlmuter, L.C. Cognition and hopelessness in association with subsyndromal orthostatic hypotension. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010, 65, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmuter, L.C.; Sarda, G.; Casavant, V.; O’Hara, K.; Hindes, M.; Knott, P.T.; Mosnaim, A.D. A review of orthostatic blood pressure regulation and its association with mood and cognition. Clin Auton Res 2012, 22, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Schussler, P.; Steiger, A. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: the forgotten stress hormone system: relationship to depression and sleep. Pharmacopsychiatry 2012, 45, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kloet, E.R.; Van Acker, S.A.; Sibug, R.M.; Oitzl, M.S.; Meijer, O.C.; Rahmouni, K.; de Jong, W. Brain mineralocorticoid receptors and centrally regulated functions. Kidney Int 2000, 57, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress and inflammation. Am J Proctol 1953, 4, 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hlavacova, N.; Wes, P.D.; Ondrejcakova, M.; Flynn, M.E.; Poundstone, P.K.; Babic, S.; Murck, H.; Jezova, D. Subchronic treatment with aldosterone induces depression-like behaviours and gene expression changes relevant to major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012, 15, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joels, M.; de Kloet, E.R. 30 YEARS OF THE MINERALOCORTICOID RECEPTOR: The brain mineralocorticoid receptor: a saga in three episodes. J Endocrinol 2017, 234, T49–T66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S. Stress and the “extended” autonomic system. Auton Neurosci 2021, 236, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Sanchez, E.P. Mineralocorticoid receptors in the brain and cardiovascular regulation: minority rule? Trends Endocrinol Metab 2011, 22, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.; Bermudez, I.; Hlavacova, N.; Babic, S.; Murck, H.; Schmuckermair, C.; Singewald, N.; Gaburro, S.; Jezova, D. Aldosterone increases earlier than corticosterone in new animal models of depression: is this an early marker? J Psychiatr Res 2012, 46, 1394–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, M.; Bermudez, I.; Murck, H.; Singewald, N.; Gaburro, S. Sub-chronic dietary tryptophan depletion--an animal model of depression with improved face and good construct validity. J Psychiatr Res 2012, 46, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, M.; Hlavacova, N.; Babic, S.; Pokusa, M.; Bermudez, I.; Jezova, D. Aldosterone Signals the Onset of Depressive Behaviour in a Female Rat Model of Depression along with SSRI Treatment Resistance. Neuroendocrinology 2015, 102, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gideon, A.; Sauter, C.; Fieres, J.; Berger, T.; Renner, B.; Wirtz, P.H. Kinetics and Interrelations of the Renin Aldosterone Response to Acute Psychosocial Stress: A Neglected Stress System. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makatsori, A.; Duncko, R.; Moncek, F.; Loder, I.; Katina, S.; Jezova, D. Modulation of neuroendocrine response and non-verbal behavior during psychosocial stress in healthy volunteers by the glutamate release-inhibiting drug lamotrigine. Neuroendocrinology 2004, 79, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Held, K.; Ziegenbein, M.; Kunzel, H.; Koch, K.; Steiger, A. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in patients with depression compared to controls--a sleep endocrine study. BMC Psychiatry 2003, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, E.; Geroldi, D.; Minoretti, P.; Coen, E.; Politi, P. Increased plasma aldosterone in patients with clinical depression. Arch Med Res 2005, 36, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, J.; Wingenfeld, K.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Chae, W.R.; Salchow, P.; Abu-Tir, I.; Piber, D.; Hellmann-Regen, J.; Otte, C. Cardiovascular risk and steroid hormone secretion after stimulation of mineralocorticoid and NMDA receptors in depressed patients. Translational Psychiatry 2020, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakova, L.; Hlavacova, N.; Segeda, V.; Kapsdorfer, D.; Morovicsova, E.; Jezova, D. Salivary aldosterone, cortisol and their morning to evening slopes in patients with depressive disorder and healthy subjects: acute episode and follow up six months after reaching remission. Neuroendocrinology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segeda, V.; Izakova, L.; Hlavacova, N.; Bednarova, A.; Jezova, D. Aldosterone concentrations in saliva reflect the duration and severity of depressive episode in a sex dependent manner. J Psychiatr Res 2017, 91, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Adolf, C.; Schneider, A.; Schlageter, L.; Heinrich, D.; Ritzel, K.; Sturm, L.; Quinkler, M.; Beuschlein, F.; Reincke, M. , et al. Differential effects of reduced mineralocorticoid receptor activation by unilateral adrenalectomy vs mineralocorticoid antagonist treatment in patients with primary aldosteronism - Implications for depression and anxiety. J Psychiatr Res 2021, 137, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzel, H.E. Psychopathological symptoms in patients with primary hyperaldosteronism--possible pathways. Horm Metab Res 2012, 44, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondy, B.; Baghai, T.C.; Zill, P.; Schule, C.; Eser, D.; Deiml, T.; Zwanzger, P.; Ella, R.; Rupprecht, R. Genetic variants in the angiotensin I-converting-enzyme (ACE) and angiotensin II receptor (AT1) gene and clinical outcome in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005, 29, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Schlageter, L.; Schneider, A.; Adolf, C.; Heinrich, D.; Quinkler, M.; Beuschlein, F.; Reincke, M.; Kunzel, H. The potential pathophysiological role of aldosterone and the mineralocorticoid receptor in anxiety and depression - Lessons from primary aldosteronism. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 130, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhtman, E.; Geerling, J.C.; Loewy, A.D. Aldosterone-sensitive neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract: multisynaptic pathway to the nucleus accumbens. J Comp Neurol 2007, 501, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstenpointner, J.; Maallo, A.M.S.; Elman, I.; Holmes, S.; Freeman, R.; Baron, R.; Borsook, D. The solitary nucleus connectivity to key autonomic regions in humans. Eur J Neurosci 2022, 56, 3938–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H.D.; Harrison, N.A. Visceral influences on brain and behavior. Neuron 2013, 77, 624–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.W.; Geerling, J.C.; Loewy, A.D. Vagal innervation of the aldosterone-sensitive HSD2 neurons in the NTS. Brain Res 2009, 1249, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerling, J.C.; Loewy, A.D. Sodium depletion activates the aldosterone-sensitive neurons in the NTS independently of thirst. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007, 292, R1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, P.; Leshem, M. Dietary sodium, added salt, and serum sodium associations with growth and depression in the U.S. general population. Appetite 2014, 79, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileri-Gurel, E.; Pehlivanoglu, B.; Dogan, M. Effect of acute stress on taste perception: in relation with baseline anxiety level and body weight. Chem Senses 2013, 38, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, T.P.; Melichar, J.K.; Nutt, D.J.; Donaldson, L.F. Human taste thresholds are modulated by serotonin and noradrenaline. J Neurosci 2006, 26, 12664–12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyenet, P.G.; Stornetta, R.L.; Souza, G.; Abbott, S.B.G.; Brooks, V.L. Neuronal Networks in Hypertension: Recent Advances. Hypertension 2020, 76, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, K.D.; Leuenberger, U.A.; Ray, C.A. Aldosterone impairs baroreflex sensitivity in healthy adults. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007, 292, H190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, G.S.; Brognara, F.; Castania, J.A.; Talbot, J.; Cunha, T.M.; Cunha, F.Q.; Ulloa, L.; Kanashiro, A.; Dias, D.P.; Salgado, H.C. Baroreflex activation in conscious rats modulates the joint inflammatory response via sympathetic function. Brain Behav Immun 2015, 49, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Kang, Y.M.; Yu, Y.; Wei, S.G.; Schmidt, T.J.; Johnson, A.K.; Felder, R.B. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 activity in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus modulates sympathetic excitation. Hypertension 2006, 48, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csecs, J.L.L.; Dowell, N.G.; Savage, G.K.; Iodice, V.; Mathias, C.J.; Critchley, H.D.; Eccles, J.A. Variant connective tissue (joint hypermobility) and dysautonomia are associated with multimorbidity at the intersection between physical and psychological health. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2021, 187, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juruena, M.F.; Cleare, A.J.; Papadopoulos, A.S.; Poon, L.; Lightman, S.; Pariante, C.M. Different responses to dexamethasone and prednisolone in the same depressed patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006, 189, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juruena, M.F.; Pariante, C.M.; Papadopoulos, A.S.; Poon, L.; Lightman, S.; Cleare, A.J. The role of mineralocorticoid receptor function in treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol 2013, 27, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, W.; Fischer, I.; Ebenroth, S.; Appel, S.; Knedel, M.; Lucker, P.W.; Rennekamp, H. [Pharmacokinetics of 9 -fluorhydrocortisone]. Arzneimittelforschung 1971, 21, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty, S.J.; Epstein, A.N. Sodium appetite elicited by intracerebroventricular infusion of angiotensin II in the rat: II. Synergistic interaction with systemic mineralocorticoids. Behav Neurosci 1983, 97, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G.; Handal, P.J. Aldosterone-induced sodium appetite: dose-response and specificity. Endocrinology 1966, 78, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, R.R.; McEwen, B.S.; Fluharty, S.J.; Ma, L.Y. The amygdala: site of genomic and nongenomic arousal of aldosterone-induced sodium intake. Kidney Int 2000, 57, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, R.R.; Nicolaidis, S.; Epstein, A.N. Salt appetite is suppressed by interference with angiotensin II and aldosterone. Am J Physiol 1986, 251, R762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graudal, N.A.; Hubeck-Graudal, T.; Jurgens, G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2020, 12, CD004022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, M. Low dietary sodium is anxiogenic in rats. Physiol Behav 2011, 103, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grippo, A.J.; Moffitt, J.A.; Beltz, T.G.; Johnson, A.K. Reduced hedonic behavior and altered cardiovascular function induced by mild sodium depletion in rats. Behav Neurosci 2006, 120, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Kadota, K.; Koyamatsu, J.; Yamanashi, H.; Nagayoshi, M.; Noda, M.; Nishimura, T.; Tayama, J.; Nagata, Y.; Maeda, T. Salt intake and mental distress among rural community-dwelling Japanese men. Journal of physiological anthropology 2015, 34, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Calvird, M.; Gordon, R.D.; Taylor, P.J.; Ward, G.; Pimenta, E.; Young, R.; Stowasser, M. Effects of two selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, sertraline and escitalopram, on aldosterone/renin ratio in normotensive depressed male patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, L.; Godino, A.; Dalmasso, C.; Caeiro, X.E.; Macchione, A.F.; Cambiasso, M.J. Neurochemical Circuits Subserving Fluid Balance and Baroreflex: A Role for Serotonin, Oxytocin, and Gonadal Steroids. In Neurobiology of Body Fluid Homeostasis: Transduction and Integration, De Luca, L.A., Jr., Menani, J.V., Johnson, A.K., Eds. Boca Raton (FL), 2014.

- Charloux, A.; Gronfier, C.; Lonsdorfer-Wolf, E.; Piquard, F.; Brandenberger, G. Aldosterone release during the sleep-wake cycle in humans. Am J Physiol 1999, 276, E43–E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, H.H.; Lim, Q.H.; Chai, C.S.; Goh, S.L.; Lim, L.L.; Yee, A.; Sukor, N. Influence and implications of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in obstructive sleep apnea: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res 2023, 32, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstad, P.K.; Oktedalen, O.; Aakvaag, A.; Fonnum, F.; Lund, P.K. Plasma renin activity and serum aldosterone during prolonged physical strain. The significance of sleep and energy deprivation. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1985, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, E.P.; Luborsky, L.; McKay, J.R.; Rosenthal, R.; Houldin, A.; Tax, A.; McCorkle, R.; Seligman, D.A.; Schmidt, K. The relationship of depression and stressors to immunological assays: a meta-analytic review. Brain Behav Immun 2001, 15, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Henriquez, G.; Simon, M.S.; Burger, B.; Weidinger, E.; Wijkhuijs, A.; Arolt, V.; Birkenhager, T.K.; Musil, R.; Muller, N.; Drexhage, H.A. Low-Grade Inflammation as a Predictor of Antidepressant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy Response in MDD Patients: A Systematic Review of the Literature in Combination With an Analysis of Experimental Data Collected in the EU-MOODINFLAME Consortium. Frontiers in psychiatry 2019, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howren, M.B.; Lamkin, D.M.; Suls, J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2009, 71, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, T.W.; Mletzko, T.C.; Alagbe, O.; Musselman, D.L.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Miller, A.H.; Heim, C.M. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1630–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Bueno, B.; Caso, J.R.; Madrigal, J.L.; Leza, J.C. Innate immune receptor Toll-like receptor 4 signalling in neuropsychiatric diseases. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016, 64, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay-Richter, C.; Janelidze, S.; Hallberg, L.; Brundin, L. Changes in behaviour and cytokine expression upon a peripheral immune challenge. Behav Brain Res 2011, 222, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenois, F.; Moreau, M.; O’Connor, J.; Lawson, M.; Micon, C.; Lestage, J.; Kelley, K.W.; Dantzer, R.; Castanon, N. Lipopolysaccharide induces delayed FosB/DeltaFosB immunostaining within the mouse extended amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus, that parallel the expression of depressive-like behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, R. Endotoxin produces a depressive-like episode in rats. Brain Res 1996, 711, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedder, H.; Schreiber, W.; Schuld, A.; Kainz, M.; Lauer, C.J.; Krieg, J.C.; Holsboer, F.; Pollmacher, T. Immune-endocrine host response to endotoxin in major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2007, 41, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Kubera, M.; Leunis, J.C. The gut-brain barrier in major depression: intestinal mucosal dysfunction with an increased translocation of LPS from gram negative enterobacteria (leaky gut) plays a role in the inflammatory pathophysiology of depression. Neuro endocrinology letters 2008, 29, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kizaki, T.; Shirato, K.; Sakurai, T.; Ogasawara, J.E.; Oh-ishi, S.; Matsuoka, T.; Izawa, T.; Imaizumi, K.; Haga, S.; Ohno, H. Beta2-adrenergic receptor regulate Toll-like receptor 4-induced late-phase NF-kappaB activation. Mol Immunol 2009, 46, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glezer, I.; Zekki, H.; Scavone, C.; Rivest, S. Modulation of the innate immune response by NMDA receptors has neuropathological consequences. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 11094–11103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glezer, I.; Simard, A.R.; Rivest, S. Neuroprotective role of the innate immune system by microglia. Neuroscience 2007, 147, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Z. Glycyrrhizin Treatment Facilitates Extinction of Conditioned Fear Responses After a Single Prolonged Stress Exposure in Rats. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 45, 2529–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Long, Z.; Zou, J. Ketamine Alleviates Depressive-Like Behaviors via Down-Regulating Inflammatory Cytokines Induced by Chronic Restraint Stress in Mice. Biol Pharm Bull 2017, 40, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garate, I.; Garcia-Bueno, B.; Madrigal, J.L.; Bravo, L.; Berrocoso, E.; Caso, J.R.; Mico, J.A.; Leza, J.C. Origin and consequences of brain Toll-like receptor 4 pathway stimulation in an experimental model of depression. J Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garate, I.; Garcia-Bueno, B.; Madrigal, J.L.; Caso, J.R.; Alou, L.; Gomez-Lus, M.L.; Mico, J.A.; Leza, J.C. Stress-induced neuroinflammation: role of the Toll-like receptor-4 pathway. Biol Psychiatry 2013, 73, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garate, I.; Garcia-Bueno, B.; Madrigal, J.L.; Caso, J.R.; Alou, L.; Gomez-Lus, M.L.; Leza, J.C. Toll-like 4 receptor inhibitor TAK-242 decreases neuroinflammation in rat brain frontal cortex after stress. J Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisor, J.P.; Clegern, W.C.; Schmidt, M.A. Toll-like receptor 4 is a regulator of monocyte and electroencephalographic responses to sleep loss. Sleep 2011, 34, 1335–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yamagata, K.; Krukoff, T.L. Differential expression of the CD14/TLR4 complex and inflammatory signaling molecules following i.c.v. administration of LPS. Brain Res 2006, 1095, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. Reflex control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2009, 9, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, K.M.; Ribnicky, D.M.; Hermann, G.E.; Rogers, R.C. St. John’s Wort enhances the synaptic activity of the nucleus of the solitary tract. Nutrition 2014, 30, S37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, D.M.; Verberne, A.J. The role of NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in the NTS in mediating three distinct sympathoinhibitory reflexes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2007, 376, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Furube, E.; Morita, S.; Wanaka, A.; Nakashima, T.; Miyata, S. Astrocytic TLR4 expression and LPS-induced nuclear translocation of STAT3 in the sensory circumventricular organs of adult mouse brain. J Neuroimmunol 2015, 278, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoi, T.; Okuma, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Nomura, Y. Novel pathway for LPS-induced afferent vagus nerve activation: possible role of nodose ganglion. Auton Neurosci 2005, 120, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaris, A. Inflammation and depression but where does the inflammation come from? Curr Opin Psychiatry 2019, 32, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, M.J.; Ganta, C.K. Autonomic nervous system and immune system interactions. Comprehensive Physiology 2014, 4, 1177–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, G.; Straub, R.H. The sympathetic nervous response in inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther 2014, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.N.; Tepper, P.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Woodard, G.A.; Sutton-Tyrrell, K. Serum aldosterone is associated with inflammation and aortic stiffness in normotensive overweight and obese young adults. Clin Exp Hypertens 2012, 34, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.N.; Fried, L.; Tepper, P.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Conroy, M.B.; Evans, R.W.; Mori Brooks, M.; Woodard, G.A.; Sutton-Tyrrell, K. Changes in serum aldosterone are associated with changes in obesity-related factors in normotensive overweight and obese young adults. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension 2013, 36, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bay-Richter, C.; Hallberg, L.; Ventorp, F.; Janelidze, S.; Brundin, L. Aldosterone synergizes with peripheral inflammation to induce brain IL-1beta expression and depressive-like effects. Cytokine 2012, 60, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lemus, E.; Murakami, Y.; Larrayoz-Roldan, I.M.; Moughamian, A.J.; Pavel, J.; Nishioku, T.; Saavedra, J.M. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade decreases lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in the rat adrenal gland. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 5177–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benicky, J.; Sanchez-Lemus, E.; Honda, M.; Pang, T.; Orecna, M.; Wang, J.; Leng, Y.; Chuang, D.M.; Saavedra, J.M. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade ameliorates brain inflammation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libianto, R.; Hu, J.; Chee, M.R.; Hoo, J.; Lim, Y.Y.; Shen, J.; Li, Q.; Young, M.J.; Fuller, P.J.; Yang, J. A Multicenter Study of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Primary Aldosteronism. J Endocr Soc 2020, 4, bvaa153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrada, A.A.; Contreras, F.J.; Marini, N.P.; Amador, C.A.; Gonzalez, P.A.; Cortes, C.M.; Riedel, C.A.; Carvajal, C.A.; Figueroa, F.; Michea, L.F. , et al. Aldosterone promotes autoimmune damage by enhancing Th17-mediated immunity. J Immunol 2010, 184, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odermatt, A.; Kratschmar, D.V. Tissue-specific modulation of mineralocorticoid receptor function by 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012, 350, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurel, E.; Toups, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Inflammation: Double Trouble. Neuron 2020, 107, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloiber, S.; Ising, M.; Reppermund, S.; Horstmann, S.; Dose, T.; Majer, M.; Zihl, J.; Pfister, H.; Unschuld, P.G.; Holsboer, F. , et al. Overweight and obesity affect treatment response in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2007, 62, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantaratnotai, N.; Mosikanon, K.; Lee, Y.; McIntyre, R.S. The interface of depression and obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract 2017, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasserre, A.M.; Glaus, J.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Vaucher, J.; Bastardot, F.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Preisig, M. Depression with atypical features and increase in obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, and fat mass: a prospective, population-based study. JAMA psychiatry 2014, 71, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasserre, A.M.; Strippoli, M.F.; Glaus, J.; Gholam-Rezaee, M.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Castelao, E.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Preisig, M. Prospective associations of depression subtypes with cardio-metabolic risk factors in the general population. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.E.; Freedland, K.E.; Carney, R.M.; Stetler, C.A.; Banks, W.A. Pathways linking depression, adiposity, and inflammatory markers in healthy young adults. Brain Behav Immun 2003, 17, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reedt Dortland, A.K.; Vreeburg, S.A.; Giltay, E.J.; Licht, C.M.; Vogelzangs, N.; van Veen, T.; de Geus, E.J.; Penninx, B.W.; Zitman, F.G. The impact of stress systems and lifestyle on dyslipidemia and obesity in anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reedt Dortland, A.K.; Giltay, E.J.; van Veen, T.; van Pelt, J.; Zitman, F.G.; Penninx, B.W. Associations between serum lipids and major depressive disorder: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry 2010, 71, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reedt Dortland, A.K.; Giltay, E.J.; van Veen, T.; Zitman, F.G.; Penninx, B.W. Longitudinal relationship of depressive and anxiety symptoms with dyslipidemia and abdominal obesity. Psychosom Med 2013, 75, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gulbins, E.; Zhang, Y. Enhancement of endothelial permeability by free fatty acid through lysosomal cathepsin B-mediated Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 73229–73241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacurari, M.; Kafoury, R.; Tchounwou, P.B.; Ndebele, K. The Renin-Angiotensin-aldosterone system in vascular inflammation and remodeling. Int J Inflam 2014, 2014, 689360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprez, D.A. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in vascular remodeling and inflammation: a clinical review. J Hypertens 2006, 24, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kloet, A.D.; Pioquinto, D.J.; Nguyen, D.; Wang, L.; Smith, J.A.; Hiller, H.; Sumners, C. Obesity induces neuroinflammation mediated by altered expression of the renin-angiotensin system in mouse forebrain nuclei. Physiol Behav, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.W.; McClain, J.L.; Hayoz, S.F.; Dorrance, A.M. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism prevents obesity-induced cerebral artery remodeling and reduces white matter injury in rats. Microcirculation 2018, 25, e12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irani, H.; Abiri, B.; Khodami, B.; Yari, Z.; Lafzi Ghazi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; Saidpour, A. Effect of time restricted feeding on anthropometric measures, eating behavior, stress, serum levels of BDNF and LBP in overweight/obese women with food addiction: a randomized clinical trial. Nutr Neurosci 2024, 27, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.; Dong, S.; Zhou, F.; Zheng, D.; Wang, C.; Dong, Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1283621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterhansel, C.; Petroff, D.; Klinitzke, G.; Kersting, A.; Wagner, B. Risk of completed suicide after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2013, 14, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zade, D.; Beiser, A.; McGlinchey, R.; Au, R.; Seshadri, S.; Palumbo, C.; Wolf, P.A.; DeCarli, C.; Milberg, W. Apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele modifies waist-to-hip ratio effects on cognition and brain structure. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013, 22, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willette, A.A.; Kapogiannis, D. Does the brain shrink as the waist expands? Ageing Res Rev 2015, 20, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontiroli, A.E.; Merlotti, C.; Veronelli, A.; Lombardi, F. Effect of weight loss on sympatho-vagal balance in subjects with grade-3 obesity: restrictive surgery versus hypocaloric diet. Acta Diabetol 2013, 50, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenstab, J.J.; Sweet, L.H.; Del Parigi, A.; McCaffery, J.M.; Haley, A.P.; Demos, K.E.; Cohen, R.A.; Wing, R.R. Cortical thickness of the cognitive control network in obesity and successful weight loss maintenance: a preliminary MRI study. Psychiatry Res 2012, 202, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreimuller, N.; Lieb, K.; Tadic, A.; Engelmann, J.; Wollschlager, D.; Wagner, S. Body mass index (BMI) in major depressive disorder and its effects on depressive symptomatology and antidepressant response. J Affect Disord 2019, 256, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angst, J.; Gamma, A.; Benazzi, F.; Silverstein, B.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Eich, D.; Rossler, W. Atypical depressive syndromes in varying definitions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, J.S.; Stewart, J.W.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Cook, I.A.; Manev, R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Shores-Wilson, K.; Balasubramani, G.K.; Biggs, M.M. , et al. Clinical and demographic features of atypical depression in outpatients with major depressive disorder: preliminary findings from STAR*D. J Clin Psychiatry 2005, 66, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matza, L.S.; Revicki, D.A.; Davidson, J.R.; Stewart, J.W. Depression with atypical features in the National Comorbidity Survey: classification, description, and consequences. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003, 60, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quitkin, F.M.; Stewart, J.W.; McGrath, P.J.; Tricamo, E.; Rabkin, J.G.; Ocepek-Welikson, K.; Nunes, E.; Harrison, W.; Klein, D.F. Columbia atypical depression. A subgroup of depressives with better response to MAOI than to tricyclic antidepressants or placebo. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1993, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannel, M.; Kuhn, U.; Schmidt, U.; Ploch, M.; Murck, H. St. John’s wort extract LI160 for the treatment of depression with atypical features - a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res 2010, 44, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Fava, M.; Alpert, J.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Mischoulon, D.; Otto, M.W.; Zajecka, J.; Mannel, M.; Rosenbaum, J.F. Hypericum extract in patients with MDD and reversed vegetative signs: re-analysis from data of a double-blind, randomized trial of hypericum extract, fluoxetine, and placebo. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2005, 8, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.; Tank, J.; Goldstein, D.S.; Stoeter, M.; Haertter, S.; Luft, F.C.; Jordan, J. Influence of St John’s wort on catecholamine turnover and cardiovascular regulation in humans. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2004, 76, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhbat, M.; Li, Z.; Dunlop, B.W.; Treadway, M.T.; Mehta, N.D.; Revill, K.P.; Lucido, M.J.; Hong, C.; Ashchi, A.; Wommack, E.C. , et al. Sustained effects of repeated levodopa (L-DOPA) administration on reward circuitry, effort-based motivation, and anhedonia in depressed patients with higher inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2025, 125, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitman, M.F.; Patterson, T.A.; Sakai, R.R.; Bernstein, I.L.; Figlewicz, D.P. Sodium depletion and aldosterone decrease dopamine transporter activity in nucleus accumbens but not striatum. Am J Physiol 1999, 276, R1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.X.; Penninx, B.; de Geus, E.J.C.; Lamers, F.; Kuan, D.C.; Wright, A.G.C.; Marsland, A.L.; Muldoon, M.F.; Manuck, S.B.; Gianaros, P.J. Associations of immunometabolic risk factors with symptoms of depression and anxiety: The role of cardiac vagal activity. Brain Behav Immun 2018, 73, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licht, C.M.; Vreeburg, S.A.; van Reedt Dortland, A.K.; Giltay, E.J.; Hoogendijk, W.J.; DeRijk, R.H.; Vogelzangs, N.; Zitman, F.G.; de Geus, E.J.; Penninx, B.W. Increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activity rather than changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity is associated with metabolic abnormalities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, 2458–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warne, J.P.; Foster, M.T.; Horneman, H.F.; Pecoraro, N.C.; Ginsberg, A.B.; Akana, S.F.; Dallman, M.F. Afferent signalling through the common hepatic branch of the vagus inhibits voluntary lard intake and modifies plasma metabolite levels in rats. J Physiol 2007, 583, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windham, B.G.; Fumagalli, S.; Ble, A.; Sollers, J.J.; Thayer, J.F.; Najjar, S.S.; Griswold, M.E.; Ferrucci, L. The Relationship between Heart Rate Variability and Adiposity Differs for Central and Overall Adiposity. J Obes 2012, 2012, 149516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, D.; Strom, A.; Kupriyanova, Y.; Bierwagen, A.; Bonhof, G.J.; Bodis, K.; Mussig, K.; Szendroedi, J.; Bobrov, P.; Markgraf, D.F. , et al. Association of Lower Cardiovagal Tone and Baroreflex Sensitivity With Higher Liver Fat Content Early in Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 103, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Usichenko, T.; Cummings, M.; Bernatik, M.; Willich, S.N.; Brinkhaus, B.; Dietzel, J. Effects of auricular stimulation on weight- and obesity-related parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Front Neurosci 2024, 18, 1393826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apovian, C.M.; Shah, S.N.; Wolfe, B.M.; Ikramuddin, S.; Miller, C.J.; Tweden, K.S.; Billington, C.J.; Shikora, S.A. Two-Year Outcomes of Vagal Nerve Blocking (vBloc) for the Treatment of Obesity in the ReCharge Trial. Obes Surg 2017, 27, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catinis, A.M.; Hinojosa, A.J.; Leonardi, C.; Cook, M.W. Hepatic Vagotomy in Patients With Obesity Leads to Improvement of the Cholesterol to High-Density Lipoprotein Ratio. Obes Surg 2023, 33, 3740–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubaczeuski, C.; Balbo, S.L.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Vettorazzi, J.F.; Santos-Silva, J.C.; Carneiro, E.M.; Bonfleur, M.L. Vagotomy ameliorates islet morphofunction and body metabolic homeostasis in MSG-obese rats. Braz J Med Biol Res 2015, 48, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, D.; Chen, R. Neuroimmune modulation in liver pathophysiology. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geerling, J.J.; Boon, M.R.; Kooijman, S.; Parlevliet, E.T.; Havekes, L.M.; Romijn, J.A.; Meurs, I.M.; Rensen, P.C. Sympathetic nervous system control of triglyceride metabolism: novel concepts derived from recent studies. J Lipid Res 2014, 55, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H. Neuroendocrine and Autonomic Dysregulation in Affective Disorders. In Handbook of the Biology and Pathology of Mental Disorders, Springer: 2025; pp. 1-23.

- Otte, C.; Chae, W.R.; Dogan, D.Y.; Piber, D.; Roepke, S.; Cho, A.B.; Trumm, S.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Brasanac, J.; Wingenfeld, K. , et al. Simvastatin as Add-On Treatment to Escitalopram in Patients With Major Depression and Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA psychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Luerweg, B.; Hahn, J.; Braunisch, M.; Jezova, D.; Zavorotnyy, M.; Konrad, C.; Jansen, A.; Kircher, T. Ventricular volume, white matter alterations and outcome of major depression and their relationship to endocrine parameters - A pilot study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Fava, M.; Cusin, C.; Fatt, C.C.; Trivedi, M. Brain ventricle and choroid plexus morphology as predictor of treatment response in major depression: Findings from the EMBARC study. Brain Behav Immun Health 2024, 35, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischer, V.; Gonzalez-Escamilla, G.; Ciolac, D.; Albrecht, P.; Kury, P.; Gruchot, J.; Dietrich, M.; Hecker, C.; Muntefering, T.; Bock, S. , et al. Translational value of choroid plexus imaging for tracking neuroinflammation in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenberg, J.; Be, C.s.g.; group, O.s.; Bruckl, T.M.; Erhart, M.; Kopf-Beck, J.; Kodel, M.; Rehawi, G.; Roh-Karamihalev, S.; Sauer, S. , et al. Dissecting depression symptoms: Multi-omics clustering uncovers immune-related subgroups and cell-type specific dysregulation. Brain Behav Immun 2025, 123, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravi, B.; Melloni, E.M.T.; Paolini, M.; Palladini, M.; Calesella, F.; Servidio, L.; Agnoletto, E.; Poletti, S.; Lorenzi, C.; Colombo, C. , et al. Choroid plexus volume is increased in mood disorders and associates with circulating inflammatory cytokines. Brain Behav Immun 2023, 116, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lizano, P.; Deng, G.; Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Xie, H.; Zhan, Y.; Mu, J.; Long, X.; Xiao, H. , et al. Brain-derived subgroups of bipolar II depression associate with inflammation and choroid plexus morphology. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences 2023, 77, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubaity, N.; Schubert, J.; Martins, D.; Yousaf, T.; Nettis, M.A.; Mondelli, V.; Pariante, C.; Harrison, N.A.; Bullmore, E.T.; Dima, D. , et al. Choroid plexus enlargement is associated with neuroinflammation and reduction of blood brain barrier permeability in depression. Neuroimage Clin 2022, 33, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.A.; Thompson, R.C.; Bunney, W.E.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Barchas, J.D.; Myers, R.M.; Akil, H.; Watson, S.J. Altered choroid plexus gene expression in major depressive disorder. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2014, 8, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, C.A.; Herrada, A.A.; Castillo, C.R.; Contreras, F.J.; Stehr, C.B.; Mosso, L.M.; Kalergis, A.M.; Fardella, C.E. Primary aldosteronism can alter peripheral levels of transforming growth factor beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Endocrinol Invest 2009, 32, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmaster, F.P.; Carrey, N.; Marie Langevin, L. Corpus callosal morphology in early onset adolescent depression. J Affect Disord 2013, 145, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murck, H.; Lehr, L.; Jezova, D. A viewpoint on aldosterone and BMI related brain morphology in relation to treatment outcome in patients with major depression. J Neuroendocrinol 2023, 35, e13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempster, K.S.; O’Leary, D.D.; MacNeil, A.J.; Hodges, G.J.; Wade, T.J. Linking the hemodynamic consequences of adverse childhood experiences to an altered HPA axis and acute stress response. Brain Behav Immun 2021, 93, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terock, J.; Hannemann, A.; Klinger-Konig, J.; Janowitz, D.; Grabe, H.J.; Murck, H. The neurobiology of childhood trauma-aldosterone and blood pressure changes in a community sample. World J Biol Psychiatry 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellis, M.D.; Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2014, 23, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bellis, M.D.; Keshavan, M.S.; Shifflett, H.; Iyengar, S.; Beers, S.R.; Hall, J.; Moritz, G. Brain structures in pediatric maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a sociodemographically matched study. Biol Psychiatry 2002, 52, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lizano, P.; Li, M.; Colic, L.; Chand, T.; Javaheripour, N.; Sun, H.; Deng, G.; Zhou, X.; Long, X. Associations among bipolar II depression white matter subgroups, inflammation, symptoms and childhood maltreatment. Nature Mental Health 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.; Klumparendt, A.; Doebler, P.; Ehring, T. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2017, 210, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippard, E.T.C.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2020, 177, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gomez, D.; Taylor, P.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; van den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M. , et al. Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2024, 384, e075847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethorst, C.D.; Tu, J.; Carmody, T.J.; Greer, T.L.; Trivedi, M.H. Atypical depressive symptoms as a predictor of treatment response to exercise in Major Depressive Disorder. J Affect Disord 2016, 200, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, G.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Piepoli, M.; Zanetidou, S.; Cabassi, A.; Squatrito, S.; Bagnoli, L.; Piras, A.; Mussi, C.; Senaldi, R. , et al. Physical Exercise for Late-Life Depression: Effects on Heart Rate Variability. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016, 24, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffour-Awuah, B.; Man, M.; Goessler, K.F.; Cornelissen, V.A.; Dieberg, G.; Smart, N.A.; Pearson, M.J. Effect of exercise training on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: a meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens 2024, 38, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berney, M.; Vakilzadeh, N.; Maillard, M.; Faouzi, M.; Grouzmann, E.; Bonny, O.; Favre, L.; Wuerzner, G. Bariatric Surgery Induces a Differential Effect on Plasma Aldosterone in Comparison to Dietary Advice Alone. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 745045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, G.; Xu, M.; Cai, W.; Zhu, Q.; Qian, L.; Zhang, Y.E.; Yuan, K.; Liu, J.; Li, Q. , et al. Recovery of brain structural abnormalities in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016, 40, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Lehr, L.; Hahn, J.; Braunisch, M.C.; Jezova, D.; Zavorotnyy, M. Adjunct Therapy With Glycyrrhiza Glabra Rapidly Improves Outcome in Depression-A Pilot Study to Support 11-Beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2 Inhibition as a New Target. Frontiers in psychiatry 2020, 11, 605949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert, P. Final report on the safety assessment of Glycyrrhetinic Acid, Potassium Glycyrrhetinate, Disodium Succinoyl Glycyrrhetinate, Glyceryl Glycyrrhetinate, Glycyrrhetinyl Stearate, Stearyl Glycyrrhetinate, Glycyrrhizic Acid, Ammonium Glycyrrhizate, Dipotassium Glycyrrhizate, Disodium Glycyrrhizate, Trisodium Glycyrrhizate, Methyl Glycyrrhizate, and Potassium Glycyrrhizinate. Int J Toxicol 2007, 26 Suppl 2, 79–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, Y.; Kawakami, J.; Santa, T.; Kotaki, H.; Uchino, K.; Sawada, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Iga, T. Pharmacokinetic profile of glycyrrhizin in healthy volunteers by a new high-performance liquid chromatographic method. J Pharm Sci 1992, 81, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahenbuhl, S.; Hasler, F.; Frey, B.M.; Frey, F.J.; Brenneisen, R.; Krapf, R. Kinetics and dynamics of orally administered 18 beta-glycyrrhetinic acid in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994, 78, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbrucker, R.A.; Burdock, G.A. Risk and safety assessment on the consumption of Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza sp.), its extract and powder as a food ingredient, with emphasis on the pharmacology and toxicology of glycyrrhizin. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2006, 46, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelderen, C.E.; Bijlsma, J.A.; van Dokkum, W.; Savelkoul, T.J. Glycyrrhizic acid: the assessment of a no effect level. Hum Exp Toxicol 2000, 19, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurjonsdottir, H.A.; Franzson, L.; Manhem, K.; Ragnarsson, J.; Sigurdsson, G.; Wallerstedt, S. Liquorice-induced rise in blood pressure: a linear dose-response relationship. J Hum Hypertens 2001, 15, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, T.; Fyhrquist, F.; Froseth, B.; Tikkanen, I. Effects of licorice on plasma atrial natriuretic peptide in healthy volunteers. J Intern Med 1989, 225, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.T.; Espiner, E.A.; Donald, R.A.; Hughes, H. Effect of eating liquorice on the renin-angiotensin aldosterone axis in normal subjects. Br Med J 1977, 1, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanini, D.; Lewicka, S.; Pratesi, C.; Scali, M.; Zennaro, M.C.; Zovato, S.; Gottardo, C.; Simoncini, M.; Spigariol, A.; Zampollo, V. Further studies on the mechanism of the mineralocorticoid action of licorice in humans. J Endocrinol Invest 1996, 19, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Af Geijerstam, P.; Joelsson, A.; Radholm, K.; Nystrom, F.H. A low dose of daily licorice intake affects renin, aldosterone, and home blood pressure in a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2024, 119, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.R.; Connacher, A.A.; Webb, D.J.; Edwards, C.R. Glucocorticoids and blood pressure: a role for the cortisol/cortisone shuttle in the control of vascular tone in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992, 83, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hautaniemi, E.J.; Tahvanainen, A.M.; Koskela, J.K.; Tikkakoski, A.J.; Kahonen, M.; Uitto, M.; Sipila, K.; Niemela, O.; Mustonen, J.; Porsti, I.H. Voluntary liquorice ingestion increases blood pressure via increased volume load, elevated peripheral arterial resistance, and decreased aortic compliance. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabuchi, M.; Imamura, S.; Kawakami, Z.; Ikarashi, Y.; Kase, Y. The blood-brain barrier permeability of 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid, a major metabolite of glycyrrhizin in Glycyrrhiza root, a constituent of the traditional Japanese medicine yokukansan. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2012, 32, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iigaya, K.; Onimaru, H.; Ikeda, K.; Iizuka, M.; Izumizaki, M. Cellular mechanisms of synchronized rhythmic burst generation in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Pflugers Arch 2025, 477, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broncel, A.; Bocian, R.; Klos-Wojtczak, P.; Konopacki, J. Hippocampal theta rhythm induced by vagal nerve stimulation: The effect of modulation of electrical coupling. Brain Res Bull 2019, 152, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrofelbauer, B.; Raffetseder, J.; Hauner, M.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; Ernst, W.; Szolar, O.H. Glycyrrhizin, the main active compound in liquorice, attenuates pro-inflammatory responses by interfering with membrane-dependent receptor signalling. Biochem J 2009, 421, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.H.; Chen, X.; Hua, H.P.; Liang, L.; Liu, L.J. The Oral Pretreatment of Glycyrrhizin Prevents Surgery-Induced Cognitive Impairment in Aged Mice by Reducing Neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s-Related Pathology via HMGB1 Inhibition. J Mol Neurosci 2017, 63, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, F.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.C.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.H.; Zhou, M.; Hang, C.H. Glycyrrhizic acid confers neuroprotection after subarachnoid hemorrhage via inhibition of high mobility group box-1 protein: a hypothesis for novel therapy of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Med Hypotheses 2013, 81, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Wu, J.; Feng, Y.; Deng, P.; Zhang, H. Glycyrrhizin ameliorates inflammatory pain by inhibiting microglial activation-mediated inflammatory response via blockage of the HMGB1-TLR4-NF-kB pathway. Exp Cell Res 2018, 369, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Weng, Z.; Zhou, T.; Feng, T.; Lin, Y. Glycyrrhizin protects brain against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice through HMGB1-TLR4-IL-17A signaling pathway. Brain Res 2014, 1582, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, H.; Komura, J.; Asada, Y.; Niwa, Y. Mechanism of anti-inflammatory action of glycyrrhizin: effect on neutrophil functions including reactive oxygen species generation. Planta Med 1991, 57, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Wang, F.; Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Qin, Y.; Si, W.; Zhang, J. 18Beta-Glycyrrhetinic Acid Attenuates H(2)O(2)-Induced Oxidative Damage and Apoptosis in Intestinal Epithelial Cells via Activating the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Zhu, M.M.; Zhang, M.H.; Wang, R.S.; Tan, X.B.; Song, J.; Ding, S.M.; Jia, X.B.; Hu, S.Y. Protection of glycyrrhizic acid against AGEs-induced endothelial dysfunction through inhibiting RAGE/NF-kappaB pathway activation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Ethnopharmacol 2013, 148, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Z.A.; Babele, P.; Sadhu, S.; Madan, U.; Tripathy, M.R.; Goswami, S.; Mani, S.; Kumar, S.; Awasthi, A.; Dikshit, M. Prophylactic treatment of Glycyrrhiza glabra mitigates COVID-19 pathology through inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hamster model and NETosis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 945583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, N.; Karimi, M.H.; Amirghofran, Z. The effect of glycyrrhizin on maturation and T cell stimulating activity of dendritic cells. Cell Immunol 2012, 280, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsah, O.; Nabishah, B.M.; Osman, C.B.; Khalid, B.A. Short- and long-term effects of glycyrrhizic acid in repetitive stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1999, 26, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H.; Karailiev, P.; Karailievova, L.; Puhova, A.; Jezova, D. Treatment with Glycyrrhiza glabra Extract Induces Anxiolytic Effects Associated with Reduced Salt Preference and Changes in Barrier Protein Gene Expression. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezova, D.; Karailiev, P.; Karailievova, L.; Puhova, A.; Murck, H. Food Enrichment with Glycyrrhiza glabra Extract Suppresses ACE2 mRNA and Protein Expression in Rats-Possible Implications for COVID-19. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Shen, X.L.; Gong, H.; Yang, Y.Y.; Bi, X.Y.; Jiang, C.L. , et al. High-mobility group box-1 was released actively and involved in LPS induced depressive-like behavior. J Psychiatr Res 2015, 64, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisli, S.; Ciftci, O.; Taslidere, A.; Basak Turkmen, N.; Ozcan, C. The beneficial effects of 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid on the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in C57BL/6 mouse model. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2018, 40, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboldi, A.; Coisne, C.; Baumjohann, D.; Benvenuto, F.; Bottinelli, D.; Lira, S.; Uccelli, A.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Engelhardt, B.; Sallusto, F. C-C chemokine receptor 6-regulated entry of TH-17 cells into the CNS through the choroid plexus is required for the initiation of EAE. Nat Immunol 2009, 10, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Cai, T.T.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, X.B.; Chen, T.; Xu, Q. Si-Ni-San, a traditional Chinese prescription, and its active ingredient glycyrrhizin ameliorate experimental colitis through regulating cytokine balance. Int Immunopharmacol 2009, 9, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Fang, D.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Gong, F.; Fang, M. Glycyrrhizin ameliorates experimental colitis through attenuating interleukin-17-producing T cell responses via regulating antigen-presenting cells. Immunol Res 2017, 65, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan, R.; Houghton, M.J.; Williamson, G. Impact of Glucose, Inflammation and Phytochemicals on ACE2, TMPRSS2 and Glucose Transporter Gene Expression in Human Intestinal Cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, W.; Safwet, N.; El-Maraghy, N.N.; Zakaria, M.N. Candesartan and glycyrrhizin ameliorate ischemic brain damage through downregulation of the TLR signaling cascade. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 724, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Singhal, T.; Sharma, H. Cardioprotective effect of ammonium glycyrrhizinate against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in experimental animals. Indian J Pharmacol 2014, 46, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tang, X.; Mao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Cui, S.; Chen, W. Ethanol Extract of Licorice Alleviates HFD-Induced Liver Fat Accumulation in Association with Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Metabolites in Obesity Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, J.K.; Hong, Y.D.; Bae, I.H.; Lim, K.M.; Park, Y.H.; Ha, H. 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid attenuates anandamide-induced adiposity and high-fat diet induced obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yi, Y.; Lin, B.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Glycyrrhizic acid mitigates hepatocyte steatosis and inflammation through ACE2 stabilization via dual modulation of AMPK activation and MDM2 inhibition. Eur J Pharmacol 2025, 1002, 177817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seseke, F.G.; Gardemann, A.; Jungermann, K. Signal propagation via gap junctions, a key step in the regulation of liver metabolism by the sympathetic hepatic nerves. FEBS Lett 1992, 301, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.C.; Bou-Holaigah, I.; Kan, J.S.; Calkins, H. Is neurally mediated hypotension an unrecognised cause of chronic fatigue? Lancet 1995, 345, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otari, K.S.; Shete, R.V.; Bhutada, R.N.; Upasani, C.D. Effect of ammonium glycyrrhizinate on haloperidol- and reserpine- induced neurobehavioral alterations in experimental paradigms. Orient Pharm Exp Med 2011, 11, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, D.; Sharma, A. Antidepressant-like activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. in mouse models of immobility tests. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006, 30, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed-Farid, O.A.; Haredy, S.A.; Niazy, R.M.; Linhardt, R.J.; Warda, M. Dose-dependent neuroprotective effect of oriental phyto-derived glycyrrhizin on experimental neuroterminal norepinephrine depletion in a rat brain model. Chem Biol Interact 2019, 308, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, M.; Ozaki, Y.; Wada, H.; Yamakage, H.; Satoh-Asahara, N.; Yasoda, A.; Sunagawa, Y.; Morimoto, T.; Tamaki, S.; Masahiro, S. , et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial for the effects of a polyherbal remedy, Yokukansan (YiganSan), in smokers with depressive tendencies. BMC Complement Med Ther 2022, 22, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikarashi, Y.; Mizoguchi, K. Neuropharmacological efficacy of the traditional Japanese Kampo medicine yokukansan and its active ingredients. Pharmacol Ther 2016, 166, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Li, J.M.; Ruan, Y.M.; Yan, W.J.; Zhong, S.Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, L.L.; Wu, R.; Wang, B. , et al. Glycyrrhizic acid as an adjunctive treatment for depression through anti-inflammation: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Affect Disord 2020, 265, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murck, H.; Mahmoudi, S.T.; Jezova, D. Inhibition of the 11beta-Hydroxysteroid-Dehydrogenase Type 2 (11betaHSD2) Reduces Aldosterone/Cortisol Ratio and Affects Treatment Outcome Depending on Childhood Trauma History and Inflammation. Biological Psychiatry 2025, 97, S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C.; Chen, C.; Xu, W.; Guo, T.; Pan, H.; Gao, S. Study on Antiviral Activities of Glycyrrhizin. International Journal of Biomedical Engineering and Clinical Science 2020, 6, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckl, J. 11beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and the brain: Not (yet) lost in translation. J Intern Med 2024, 295, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Deng, W.; Ding, L.; Ye, X.; Yin, S.; Huang, W. Glycyrrhetinic acid and its derivatives as potential alternative medicine to relieve symptoms in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.C.; Wang, M.J.; Chen, X.M.; Yu, W.L.; Chu, Y.L.; He, X.H.; Huang, R.Y. Can active components of licorice, glycyrrhizin and glycyrrhetinic acid, lick rheumatoid arthritis? Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).