Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

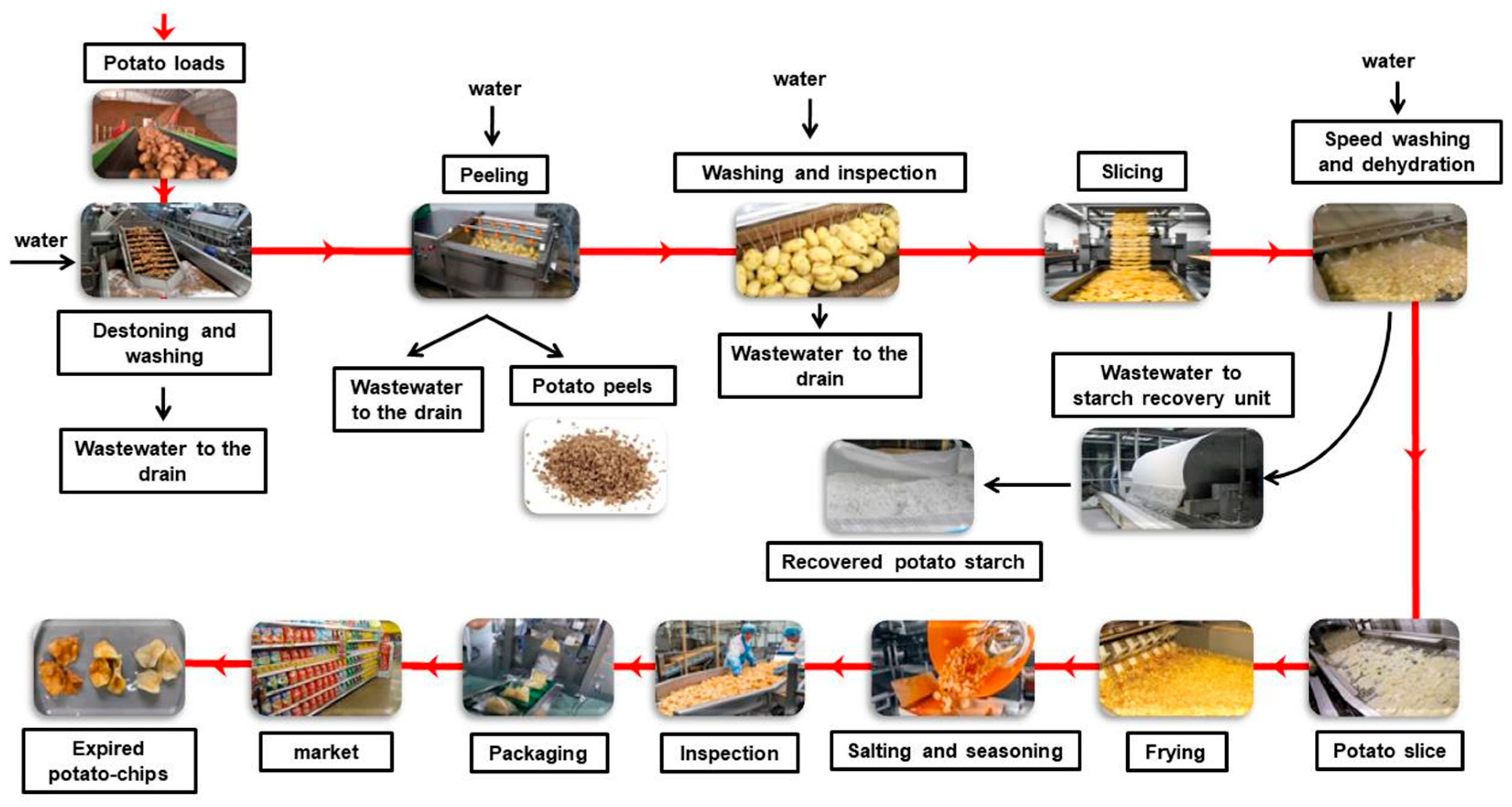

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Anaerobic Biodegradability and Methane Production with Experimental Set-Up

2.2. Source of the Sludge Inoculum

2.3. Sampling of PCP Wastes

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. Microbial Community Analysis: DNA Extraction and Metataxonomic Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Physicochemical Characteristics of PCP Wastes

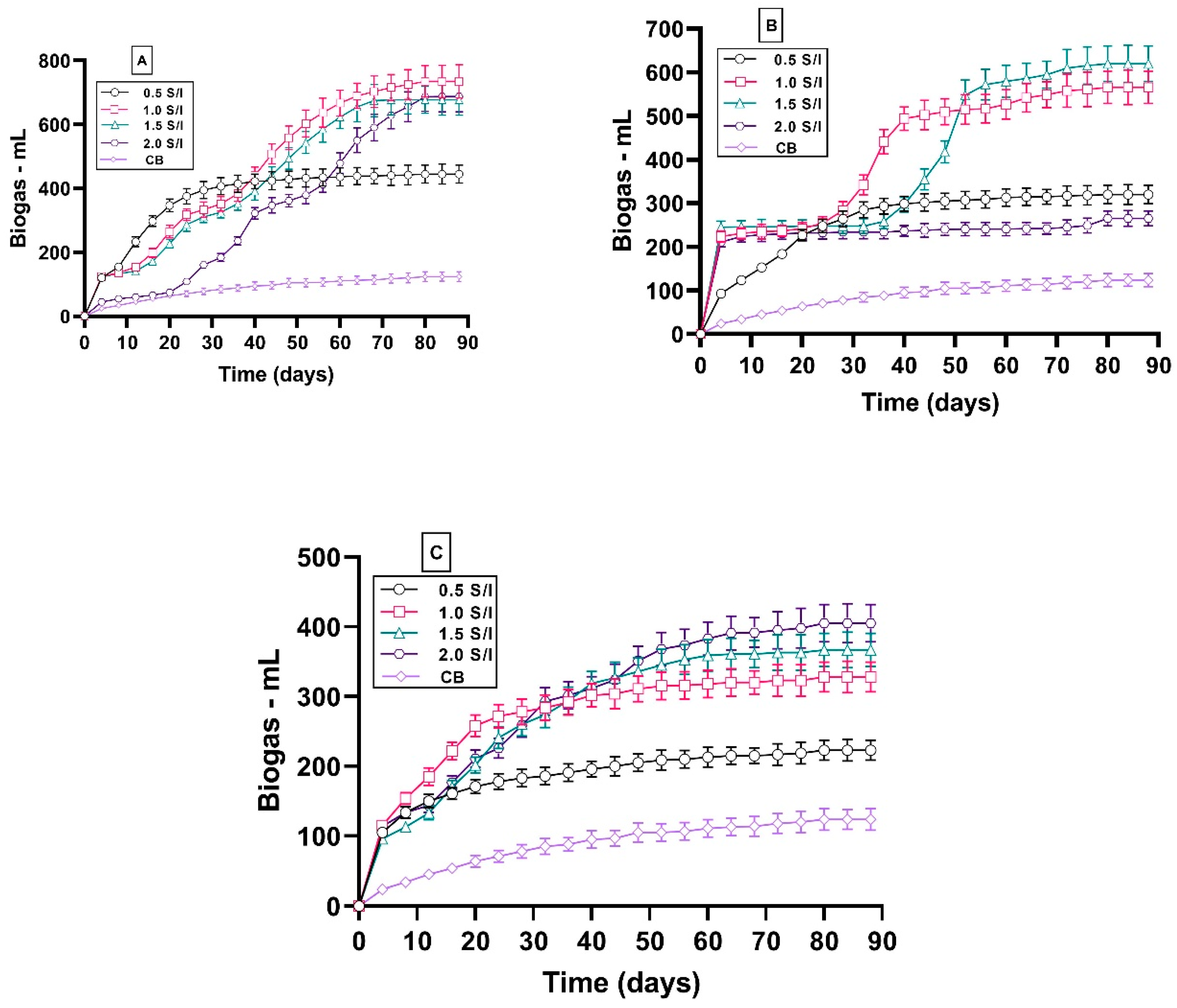

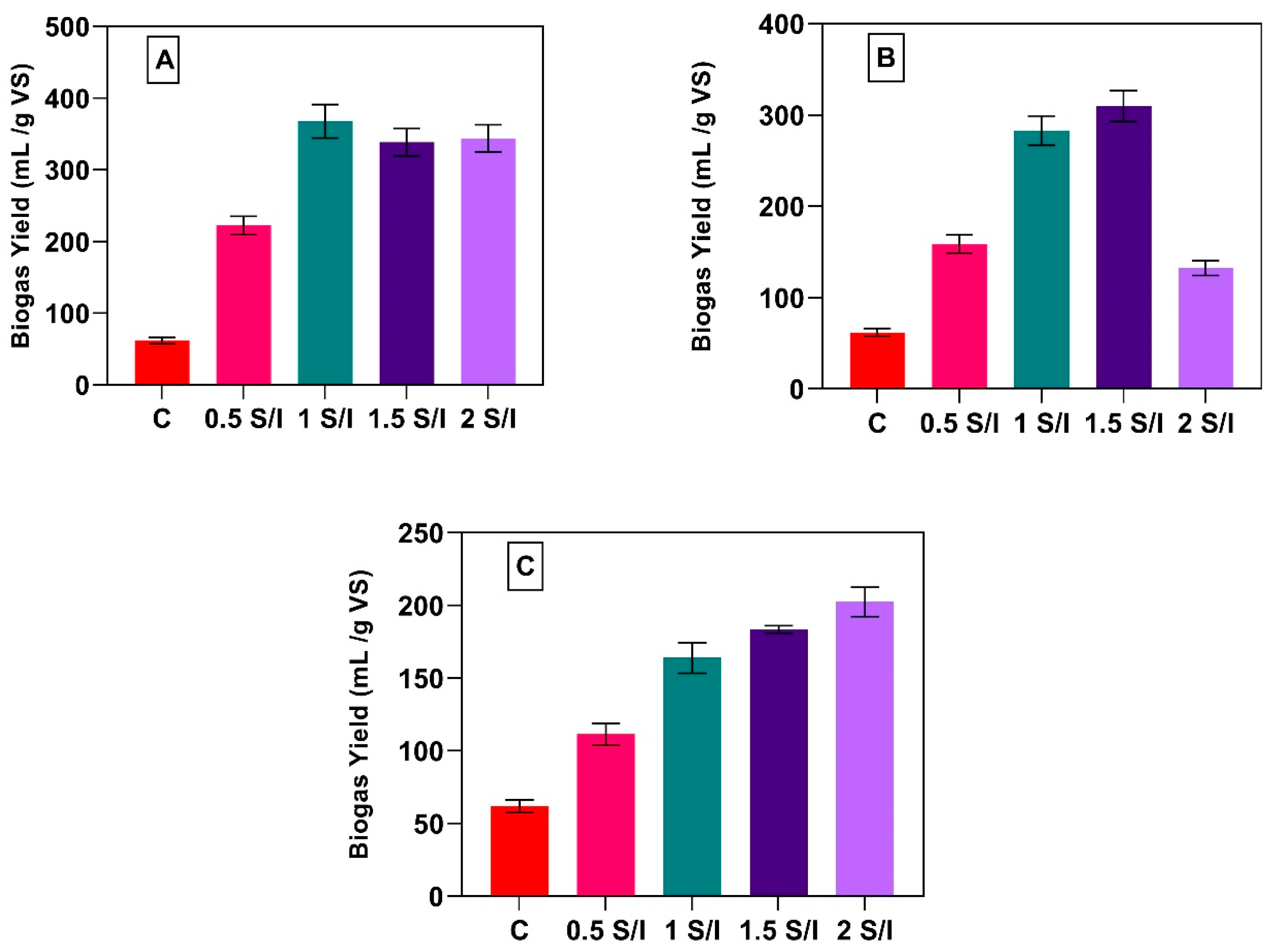

3.2. Impact of S/I Ratio on Biogas Yield

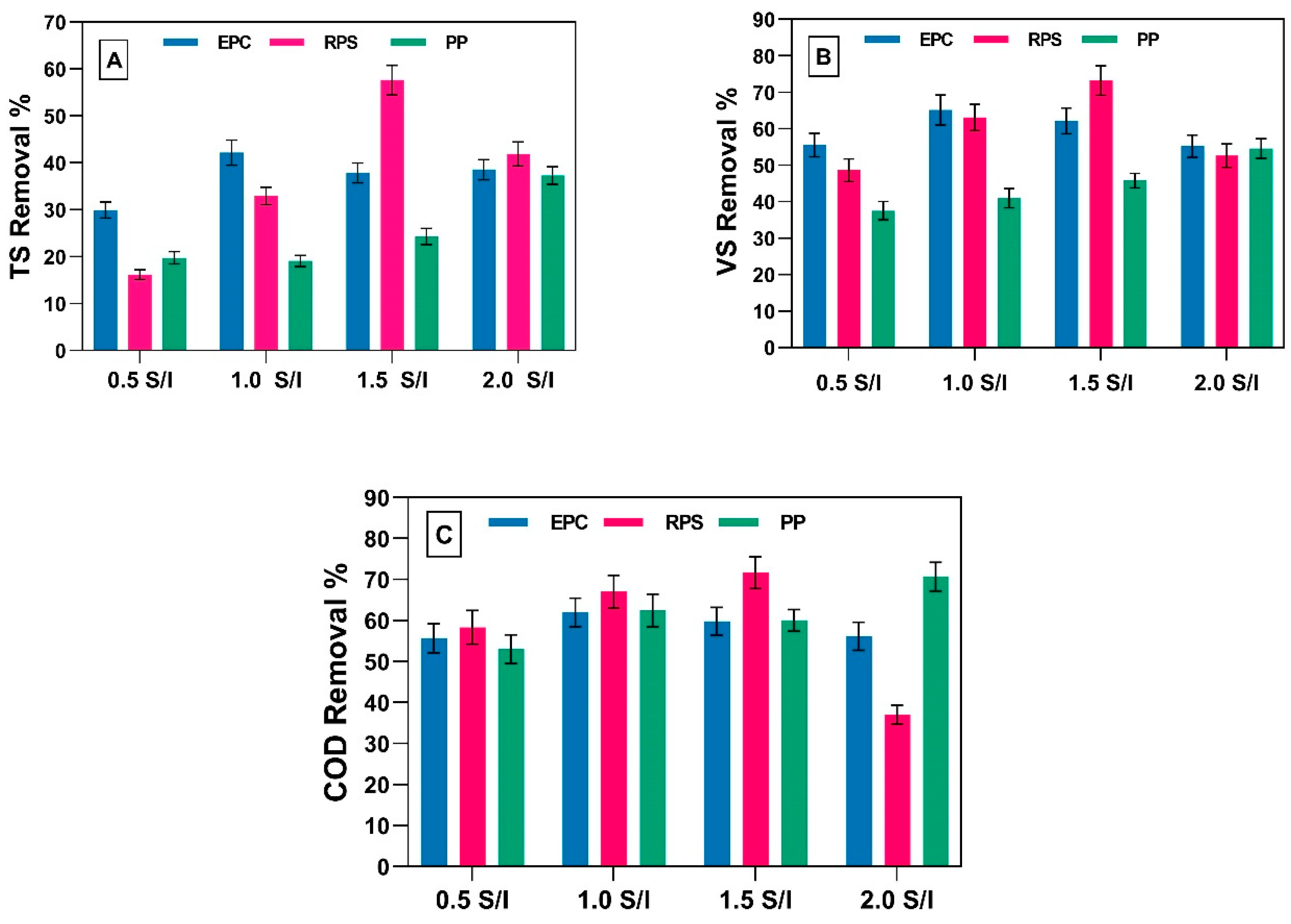

3.3. Effect of Using Different S/I Ratio on Treatment Efficiency and VFAs Degradation for EPC, RPS and PP

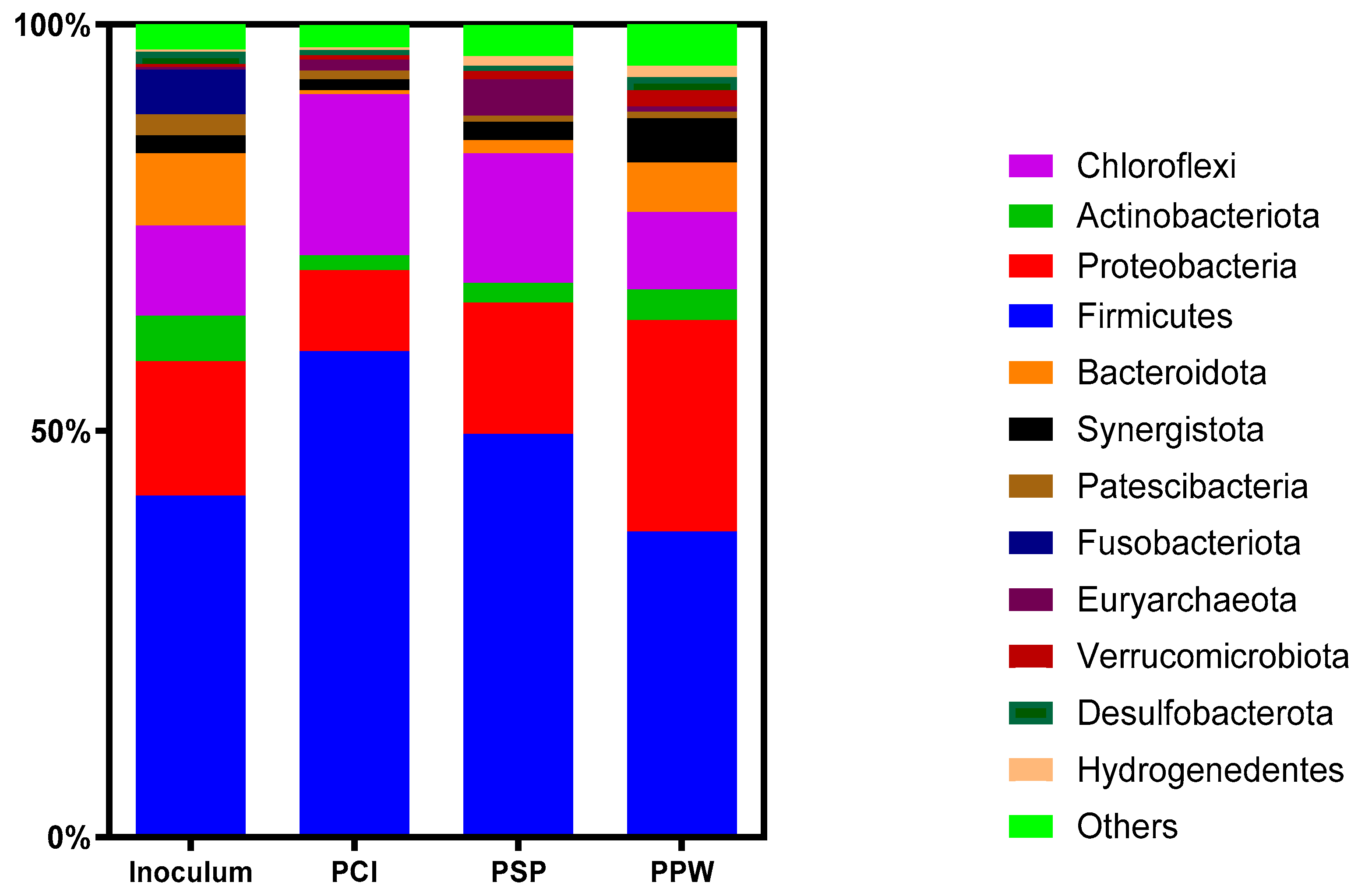

3.4. Microbial Community Shifts for AD of PCP Wastes at Optimum S/I Ratios

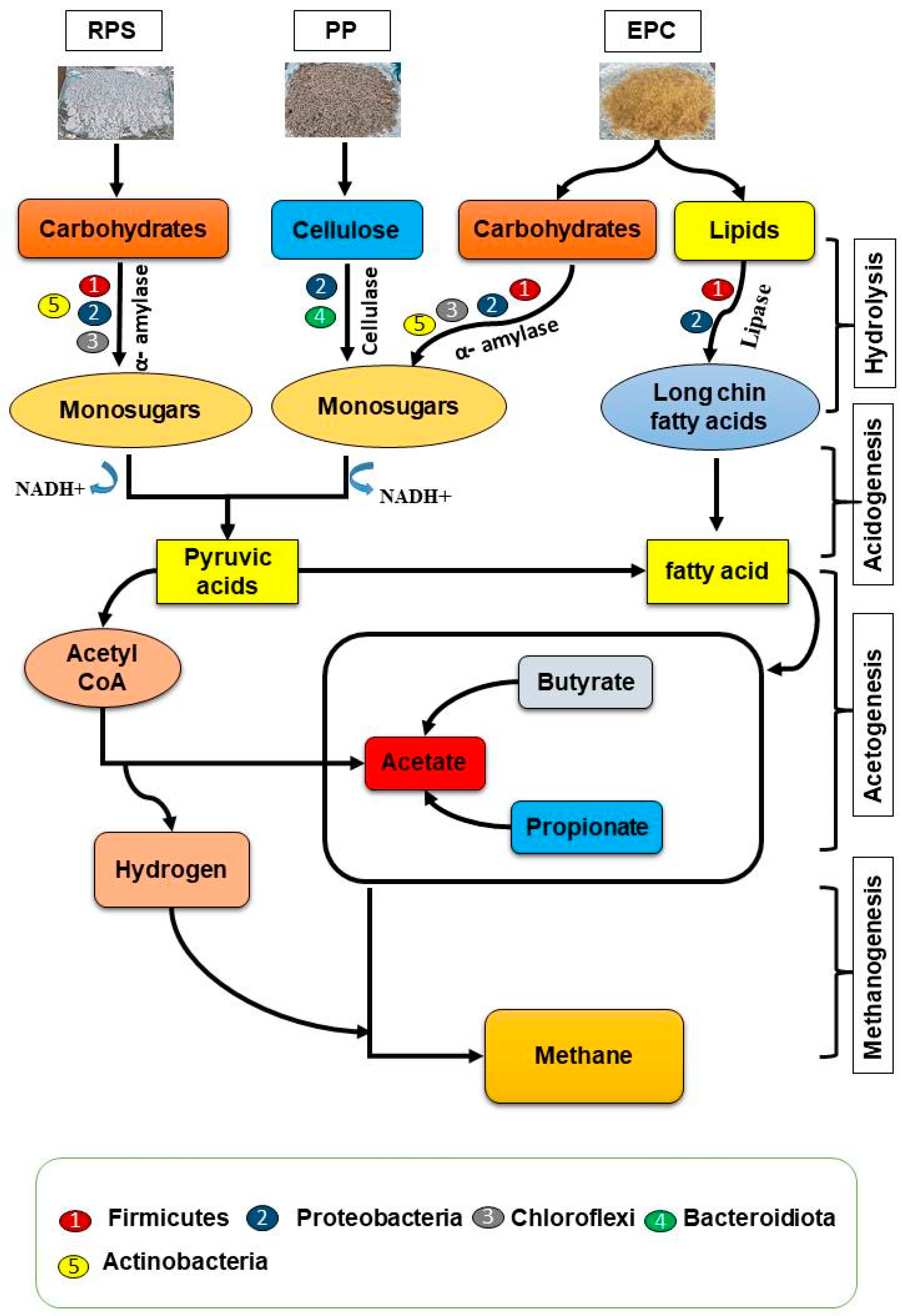

3.5. Biodegradation Pathways of PCP Wastes

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Data Availability

References

- Zaky, A.S.; French, C.E.; Tucker, G.A.; Du, C. Improving the Productivity of Bioethanol Production Using Marine Yeast and Seawater-Based Media. Biomass and Bioenergy 2020, 139, 105615. [CrossRef]

- Monir, M.U.; Aziz, A.A.; Khatun, F.; Yousuf, A. Bioethanol Production through Syngas Fermentation in a Tar Free Bioreactor Using Clostridium Butyricum. Renew. Energy 2020, 157, 1116–1123. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Moreira, N.A.; Monteiro, E. Bioenergy Overview for Portugal. Biomass and Bioenergy 2009, 33, 1567–1576. [CrossRef]

- Hellal, M.S.; Gamon, F.; Cema, G.; Hassan, G.K.; Mohamed, G.G.; Ziembińska-Buczyńska, A. Nanoparticle-Assisted Biohydrogen Production from Pretreated Food Industry Wastewater Sludge: Microbial Community Shifts in Batch and Continuous Processes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299. [CrossRef]

- Moharram, N.A.; Tarek, A.; Gaber, M.; Bayoumi, S. Brief Review on Egypt’s Renewable Energy Current Status and Future Vision. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 165–172. [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, K.; Rehan, M.; Loizidou, M.; Nizami, A.S.; Naqvi, M. Energy and Resource Recovery through Integrated Sustainable Waste Management. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114372. [CrossRef]

- Nair, L.G.; Agrawal, K.; Verma, P. An Overview of Sustainable Approaches for Bioenergy Production from Agro-Industrial Wastes. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100086. [CrossRef]

- Abanades, S.; Abbaspour, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Das, B.; Ehyaei, M.A.; Esmaeilion, F.; El Haj Assad, M.; Hajilounezhad, T.; Jamali, D.H.; Hmida, A.; et al. A Critical Review of Biogas Production and Usage with Legislations Framework across the Globe. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 3377–3400. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.K.; Mahmoud, W.H.; Al-sayed, A.; Ismail, S.H.; El-Sherif, A.A.; Abd El Wahab, S.M. Multi-Functional of TiO2@Ag Core–Shell Nanostructure to Prevent Hydrogen Sulfide Formation during Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge with Boosting of Bio-CH4 Production. Fuel 2023, 333, 126608. [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.Y.; Man, Y.B.; Wong, M.H. Use of Food Waste, Fish Waste and Food Processing Waste for China’s Aquaculture Industry: Needs and Challenge. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 635–643. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.K.; Al-Sayed, A.; Afify, A.A.; El-Liethy, M.A.; Elagroudy, S.; El-Gohary, F.A. Production of Biofuels (H2&CH4) from Food Leftovers via Dual-Stage Anaerobic Digestion: Enhancement of Bioenergy Production and Determination of Metabolic Fingerprinting of Microbial Communities. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 4105–4115. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Gao, H.; Li, Z. Bioconversion of Corn Straw by Coupling Ensiling and Solid-State Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 78, 277–280. [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.-P.; Kromann, P.; Andrade-Piedra, J.; Polar, V.; Hareau, G. Correction to: The Potato of the Future: Opportunities and Challenges in Sustainable Agri-Food Systems. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 209–210. [CrossRef]

- Goffart, J.-P.; Haverkort, A.; Storey, M.; Haase, N.; Martin, M.; Lebrun, P.; Ryckmans, D.; Florins, D.; Demeulemeester, K. Potato Production in Northwestern Europe (Germany, France, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium): Characteristics, Issues, Challenges and Opportunities. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 503–547. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.L.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Heleno, S.A.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Potato Peels as Sources of Functional Compounds for the Food Industry: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 103, 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Allam, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Mahmoud, S. An Analytical Study of the Production, Consumption and Exports of Potatoes in Egypt. Int. J. Environ. Stud. Res. 2022, 1, 274–284. [CrossRef]

- Achinas, S.; Li, Y.; Achinas, V.; Euverink, G.J.W. Biogas Potential from the Anaerobic Digestion of Potato Peels: Process Performance and Kinetics Evaluation. Energies 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Boe, K.; Angelidaki, I. Biogas Production from Potato-Juice, a by-Product from Potato-Starch Processing, in Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) and Expanded Granular Sludge Bed (EGSB) Reactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 5734–5741. [CrossRef]

- Bialek, K.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Collins, G.; Mahony, T.; O’Flaherty, V. Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of Methanogenic Community Development in High-Rate Anaerobic Bioreactors. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1298–1308. [CrossRef]

- Nielfa, A.; Cano, R.; Fdz-Polanco, M. Theoretical Methane Production Generated by the Co-Digestion of Organic Fraction Municipal Solid Waste and Biological Sludge. Biotechnol. Reports 2015, 5, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Achinas, S.; Euverink, G.J.W. Theoretical Analysis of Biogas Potential Prediction from Agricultural Waste. Resour. Technol. 2016, 2, 143–147. [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; McDonald, A.G. Anaerobic Digestion of Pre-Fermented Potato Peel Wastes for Methane Production. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 197–200. [CrossRef]

- Elbeshbishy, E.; Nakhla, G.; Hafez, H. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) of Food Waste and Primary Sludge: Influence of Inoculum Pre-Incubation and Inoculum Source. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.-R.; Frommert, I.; Jörg, R. Standardized Methods for Anaerobic Biodegradability Testing. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology 2004, 3, 141–158. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, J.; Qian, G.; Liu, J. Effective Anaerobic Biodegradation of Municipal Solid Waste Fresh Leachate Using a Novel Pilot-Scale Reactor: Comparison under Different Seeding Granular Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 165, 152–157. [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.; Oliveira, R.; Alves, M.M. Influence of Inoculum Activity on the Bio-Methanization of a Kitchen Waste under Different Waste/Inoculum Ratios. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 2019–2024. [CrossRef]

- Ponsá, S.; Gea, T.; Sánchez, A. Different Indices to Express Biodegradability in Organic Solid Wastes. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 706–712. [CrossRef]

- APHA Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; Lipps WC, Braun-Howland EB, Baxter TE, E., Ed.; 24th ed.; American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation ., 2023;

- El-Shafai, S.A.; Abdelfattah, I.; Nasr, F.A.; Fawzy, M.E. Lemna Gibba and Azolla Filiculoides for Sewage Treatment and Plant Protein Production. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016.

- Beshaw, T.; Demssie, K.; Tefera, M.; Guadie, A. Determination of Proximate Composition, Selected Essential and Heavy Metals in Sesame Seeds (Sesamum Indicum L.) from the Ethiopian Markets and Assessment of the Associated Health Risks. Toxicol. Reports 2022, 9, 1806–1812. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, N.I.H.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Mohamed Ali, M.Y. Sustainable Biogas Production from Agrowaste and Effluents – A Promising Step for Small-Scale Industry Income. Renew. Energy 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bücker, F.; Marder, M.; Peiter, M.R.; Lehn, D.N.; Esquerdo, V.M.; Antonio de Almeida Pinto, L.; Konrad, O. Fish Waste: An Efficient Alternative to Biogas and Methane Production in an Anaerobic Mono-Digestion System. Renew. Energy 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.H. Conditions of Lag-Phase Reduction during Anaerobic Digestion of Protein for High-Efficiency Biogas Production. Biomass and Bioenergy 2020. [CrossRef]

- Owamah, H.I.; Ikpeseni, S.C.; Alfa, M.I.; Oyebisi, S.O.; Gopikumar, S.; David Samuel, O.; Ilabor, S.C. Influence of Inoculum/Substrate Ratio on Biogas Yield and Kinetics from the Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste and Maize Husk. Environ. Nanotechnology, Monit. Manag. 2021, 16, 100558. [CrossRef]

- Raposo, F.; Borja, R.; Martín, M.A.; Martín, A.; de la Rubia, M.A.; Rincón, B. Influence of Inoculum-Substrate Ratio on the Anaerobic Digestion of Sunflower Oil Cake in Batch Mode: Process Stability and Kinetic Evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 149, 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Caldwell, G.S.; Zealand, A.M.; Sallis, P.J. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris and Potato Processing Waste: Effect of Mixing Ratio, Waste Type and Substrate to Inoculum Ratio. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 143, 91–100. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Banerjee, R. Modeling and Optimization of Anaerobic Codigestion of Potato Waste and Aquatic Weed by Response Surface Methodology and Artificial Neural Network Coupled Genetic Algorithm. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 386–395. [CrossRef]

- Antwi, P.; Li, J.; Boadi, P.O.; Meng, J.; Koblah Quashie, F.; Wang, X.; Ren, N.; Buelna, G. Efficiency of an Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor Treating Potato Starch Processing Wastewater and Related Process Kinetics, Functional Microbial Community and Sludge Morphology. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 105–116. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Kuittinen, S.; Zhang, J.; Vepsäläinen, J.; Keinänen, M.; Pappinen, A. Co-Fermentation of Hemicellulose and Starch from Barley Straw and Grain for Efficient Pentoses Utilization in Acetone–Butanol–Ethanol Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 179, 128–135. [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, G.; Fernández, B.; Bonmatí, A. Addition of Crude Glycerine as Strategy to Balance the C/N Ratio on Sewage Sludge Thermophilic and Mesophilic Anaerobic Co-Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 193, 377–385. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Fu, B.; Liu, H. Novel Insight into the Relationship between Organic Substrate Composition and Volatile Fatty Acids Distribution in Acidogenic Co-Fermentation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 137. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shemy, M.T.; Gamoń, F.; Al-Sayed, A.; Hellal, M.S.; Ziembińska-Buczyńska, A.; Hassan, G.K. Silver Nanoparticles Incorporated with Superior Silica Nanoparticles-Based Rice Straw to Maximize Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion of Landfill Leachate. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 365, 121715. [CrossRef]

- Barczynska, R.; Slizewska, K.; Litwin, M.; Szalecki, M.; Zarski, A.; Kapusniak, J. The Effect of Dietary Fibre Preparations from Potato Starch on the Growth and Activity of Bacterial Strains Belonging to the Phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 661–668. [CrossRef]

- Barczynska, R.; Jurgoński, A.; Slizewska, K.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Kapusniak, J. Effects of Potato Dextrin on the Composition and Metabolism of the Gut Microbiota in Rats Fed Standard and High-Fat Diets. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 34, 398–407. [CrossRef]

- Antwi, P.; Li, J.; Boadi, P.O.; Meng, J.; Shi, E.; Chi, X.; Deng, K.; Ayivi, F. Dosing Effect of Zero Valent Iron (ZVI) on Biomethanation and Microbial Community Distribution as Revealed by 16S RRNA High-Throughput Sequencing. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2017, 123, 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Antwi, P.; Li, J.; Opoku Boadi, P.; Meng, J.; Shi, E.; Xue, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ayivi, F. Functional Bacterial and Archaeal Diversity Revealed by 16S RRNA Gene Pyrosequencing during Potato Starch Processing Wastewater Treatment in an UASB. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 235, 348–357. [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Weimer, P.J.; van Zyl, W.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial Cellulose Utilization: Fundamentals and Biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 506–577. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, A.; Yang, C.; Liang, B.; Sangeetha, T.; He, Z.; Wang, L.; Cai, W.; Wang, A.; Liu, W. Enhanced Short Chain Fatty Acids Production from Waste Activated Sludge Conditioning with Typical Agricultural Residues: Carbon Source Composition Regulates Community Functions. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 192. [CrossRef]

- Puentes-Téllez, P.E.; Salles, J.F. Dynamics of Abundant and Rare Bacteria During Degradation of Lignocellulose from Sugarcane Biomass. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 79, 312–325. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Hassan, G.K.; Awad, H.; Hassan, M.; Rojas, P.; Sanz, J.L.; Elsamadony, M.; Pant, D.; Fujii, M. Strengthen “the Sustainable Farm” Concept via Efficacious Conversion of Farm Wastes into Methane. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Sethi, M. Phylogeny and Molecular Signatures for the Phylum Fusobacteria and Its Distinct Subclades. Anaerobe 2014, 28, 182–198. [CrossRef]

- Palomba, A.; Tanca, A.; Fraumene, C.; Abbondio, M.; Fancello, F.; Atzori, A.; Uzzau, S. Multi-Omic Biogeography of the Gastrointestinal Microbiota of a Pre-Weaned Lamb. Proteomes 2017, 5, 36. [CrossRef]

- Hafez, R.M.; Tawfik, A.; Hassan, G.K.; Kandil Zahran, M.; Younes, A.A.; Ziembińska-Buczyńska, A.; Gamoń, F.; Nasr, M. Valorization of Paper-Mill Sludge Laden with 2-Chlorotoluene Using Hydroxyapatite@biochar Nanocomposite to Enrich Methanogenic Community: A Techno-Economic Approach. Biomass and Bioenergy 2024, 190. [CrossRef]

- Luiz, F.N.; Passarini, M.R.Z.; Magrini, F.E.; Gaio, J.; Somer, J.G.; Meyer, R.F.; Paesi, S. Metataxonomic Characterization of the Microbial Community Involved in the Production of Biogas with Microcrystalline Cellulose in Pilot and Laboratory Scale. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 184. [CrossRef]

- Al-Fadhli, F.M.; Alhajeri, N.S.; Osman, A.I.; Tawfik, A. Enhancing Hydrogen Production from Oily Sludge: A Novel Approach Using Household Waste Digestate to Overcome Mono-Ethylene Glycol Inhibition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024. [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, A.P.; Perotti, N.I.; Martínez, M.A. Cellulose Degrading Bacteria Isolated from Industrial Samples and the Gut of Native Insects from Northwest of Argentina. J. Basic Microbiol. 2015, 55, 1384–1393. [CrossRef]

| Feed | S/I Ratios | Key |

| Control Batch (solely sludge) | 100 % inoculum | CB |

| Expired Potato-Chips | 0.5 | EPC-O.5 |

| 1.0 | EPC-1.0 | |

| 1.5 | EPC-1.5 | |

| 2.0 | EPC-2.0 | |

| Recovered Potato Starch | 0.5 | RPS-O.5 |

| 1.0 | RPS-1.0 | |

| 1.5 | RPS-1.5 | |

| 2.0 | RPS-2.0 | |

| Potato Peels | 0.5 | PP-0.5 |

| 1.0 | PP-1.0 | |

| 1.5 | PP-1.5 | |

| 2.0 | PP-2.0 |

| Parameter | Dry solid | Volatile solids | VSS/TSS | TKN | TP |

| Unit | g/l | g/L | % | % DM | % DM |

| Anaerobic sludge | 35.0±0.2 | 27.0±0.5 | 77.2±1.7 | 4.48±0.06 | 0.9±0.02 |

| Parameter | % DM | OM | Protein | Ash | Fat&oil | Carbohydrates | TKN | TP |

| EPC | 97.4±0.05 | 96.97±0.24 | 5.55±0.02 | 3.03±0.06 | 39.00±0.84 | 49.82±0.29 | 0.89±0.03 | 0.50±0.01 |

| RPS | 63.6±0.06 | 99.57±0.03 | 0.28±0.01 | 0.43±0.01 | 0.87±0.01 | 98.14±0.30 | 0.045±0.00 | 0.17±0.01 |

| PP | 10.8±0.01 | 94.69±0.22 | 9.23±0.02 | 5.31±0.01 | 1.73±0.02 | 56.23±0.20 | 1.48±0.03 | 0.40±0.01 |

| Samples/ Parameters |

Acetic acid* | Butyric acid* | Propionic acid* | TVFAs* |

| EPC 0.5 | 98 ± 7.5 | 44 ± 4.2 | 45 ± 3.5 | 187 ± 12.3 |

| EPC 1.0 | 95 ± 6.8 | 43 ± 3.9 | 27 ± 1.6 | 165 ± 11.5 |

| EPC 1.5 | 89 ± 7.2 | 33 ± 3.5 | 13 ± 0.5 | 135 ± 10.7 |

| EPC 2.0 | 165 ± 10.5 | 77 ± 5.6 | 32 ± 1.9 | 274 ± 18.7 |

| RPS 0.5 | 166 ± 9.4 | 111 ± 8.5 | 98 ± 1.5 | 375 ± 22.7 |

| RPS 1.0 | 66 ± 3.2 | 12 ± 1.5 | 10 ± 0.6 | 88 ± 6.7 |

| RPS 1.5 | 111 ± 9.5 | 55 ± 3.5 | 22 ± 0.9 | 188 ± 11.8 |

| RPS 2.0 | 142 ± 10.9 | 55 ± 2.7 | 44 ± 3.7 | 241 ± 19.7 |

| PP 0.5 | 112 ± 8.5 | 33 ± 0.8 | 45 ± 2.5 | 190 ± 16.7 |

| PP 1.0 | 180 ± 12.3 | 22 ± 0.7 | 17 ± 1.0 | 119 ± 9.9 |

| PP 1.5 | 175 ± 9.6 | 18 ± 0.5 | 13 ± 0.9 | 106 ± 9.6 |

| PP 2.0 | 177 ± 9.7 | 17 ± 0.3 | 12 ± 0.8 | 106 ± 9.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).