1. Introduction

The characteristics of functional materials may be dominated by a small amount of impurities in the intermediate materials [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. To date, we have developed numerous Si-based ceramics with characteristics dominated by impurities in their precursor materials [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

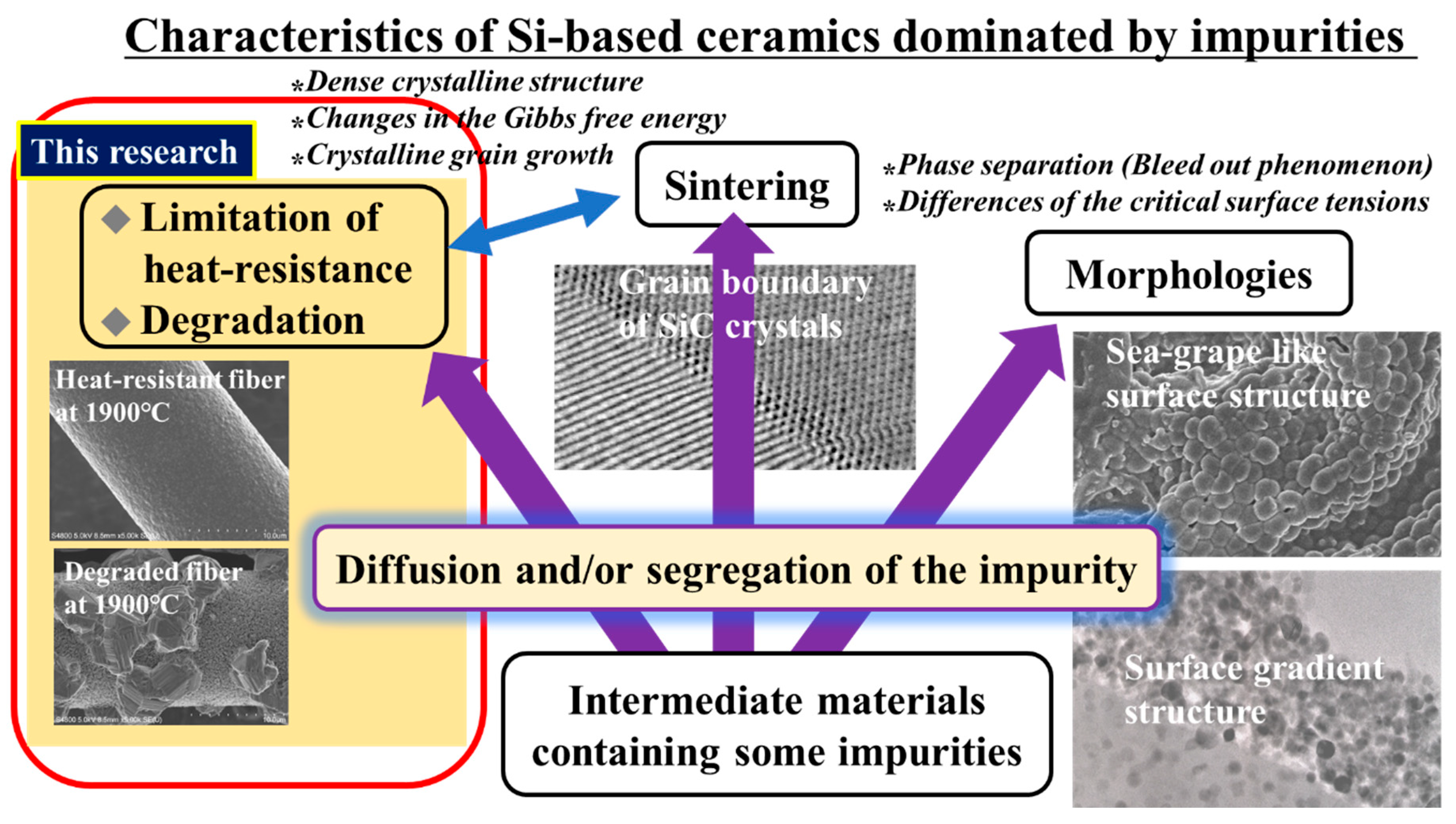

Figure 1 depicts some characteristics of Si-based ceramics dominated by impurities. The transformation of impurities can induce changes in the obtained morphology and triggers of the solid sintering process, and differences in the heat resistance of SiC polycrystalline fibers can be also caused by the transformation of impurities. SiC polycrystalline fibers are the highest heat-resistant polymer-derived SiC fibers. Since the first precursor ceramics were developed using polycarbosilane [

16], many polymer-derived SiC fibers have been developed [

12,

17]. Through the developments, the heat-resistances of the SiC-based fibers were remarkably increased from 1300

oC to 2000

oC. Of these fibers, SiC-polycrystalline fibers (Tyranno SA and Hi-Nicalon Type S) show the highest heat-resistance up to 2000

oC, and have been actively evaluated for aerospace applications as SiC/SiC composites. The final target of aerospace engine manufacturers is development of uncooled engines. A critical parameter for high thermal efficiency of gas turbine aero engines is a high overall pressure ratio, which in turn drives high turbine flow path temperatures. Turbine inlet flow path temperatures are generally higher than the thermal limits of the metal-based component materials. Therefore, air from the compressor cools the components by a combination of internal and external flow path cooling. However, minimizing the required cooling flow increases the overall efficiency of the cycle. Hence the need for developing and maturing advanced material technologies with improved high-temperature capability, such as ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) using silicon carbide (SiC) fibers. Overall, the introduction of CMCs enables reduction of a fuel burn up to two percent. Few other technologies in today’s pipelines have this much capability for fuel burn reduction. Additionally, the material density of CMCs is one-third that of today’s nickel-based alloys, enabling over 50 percent reduction in the turbine component weight. Accordingly, CMC development using SiC fibers is very important. Aeroengine manufacturers are developing new technologies aiming for new types of aircraft engines which have CMC parts throughout the engine hot section. SiC fibers play an important role in the CMCs as the reinforcement, which can be used at very high temperatures up to 2000℃. If the SiC fibers would achieve the long-time usable temperature up to 2000℃, the development of future uncooled engines would make significant progress. However, remarkable differences in the heat resistance of present SiC polycrystalline fibers have been observed. In this study, we addressed the differences in heat resistance among SiC polycrystalline fibers aiming for the development of excellent heat-resistant SiC polycrystalline fibers.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we used two types of SiC polycrystalline fibers (Hi-Nicalon Type S and Tyranno SA). Tyranno SA was produced by heat-treating amorphous Si-Al-C-O fiber synthesized from polyaluminocarbosilane [

11]. Polyaluminocarbosilane was prepared by the reaction of polycarbosilane (-SiH(CH

3)-CH

2-)n with aluminum(III)acetylacetonate. The reaction of polycarbosilane with aluminum(III)acetylacetonate proceeded at 300°C in a nitrogen atmosphere by the condensation reaction of Si-H bonds in polycarbosilane and the ligands of aluminum(III)acetylacetonate accompanied by the evolution of acetylacetone, and then the molecular weight increased by the cross-linking reaction with the formation of a Si-Al-Si bond. Polyaluminocarbosilane was melt-spun at about 200°C, and then the spun fiber was cured in air at 160°C. The cured fiber was continuously fired in inert gas up to 1300 °C to obtain an amorphous Si-Al-C-O fiber (an intermediate fiber). This fiber contained non-stoichiometric excess carbon and oxygen of about 12wt%. The Si-Al-C-O fiber was converted into the SA fiber by way of decomposition accompanied by the release of CO gas at temperatures from 1500°C to 1700°C and sintering at temperatures over 1800°C. In this sintering process, aluminum plays a very important role as a sintering aid. Tyranno SA was commercialized by UBE Industries Ltd.

Hi Nicalon Type S was synthesized using melt spinning, electron beam irradiation in He, heat-treatment at 800℃ in hydrogen atmosphere (to eliminate excess carbon), and further heat-treatment in an argon atmosphere at higher temperatures [

17]. Intermediate fibers with various C/Si compositions were prepared by pyrolysis of electron beam cured polycarbosilane (PCS) fibers in hydrogen gas atmosphere. The cured PCS fibers were pyrolyzed in H

2 gas flow from room temperature to TH (the treatment temperature in H

2 gas) and in Ar gas flow at temperatures from TH to 1300°C with a heating rate of 10°C /min. The C/Si atomic ratio of the fibers ranged from 0.84 to 1.56. The higher TH yielded to a lower C/Si ratio, but at TH ≧ 950°C, the C/Si ratio was constant at 0.83. The C/Si ratio dramatically changed at approximately 800°C. Stoichiometric SiC fiber (Hi Nicalon Type S) can be obtained at TH of slightly higher than 800°C.

The fine structure of the heat-treated materials was observed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), model JSM-700F (JEOL, Ltd.) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in conjunction with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), model JEM-2100F (JEOL, Ltd.).

Heat-treatment of the SiC polycrystalline fibers was performed at high temperatures (1600~1900℃) for 10 hours in an argon atmosphere using NEWTONIAN Pascal-40 (NAGANO).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Differences in the Fine Structure and Oxygen Content of Polycristalline Fibers

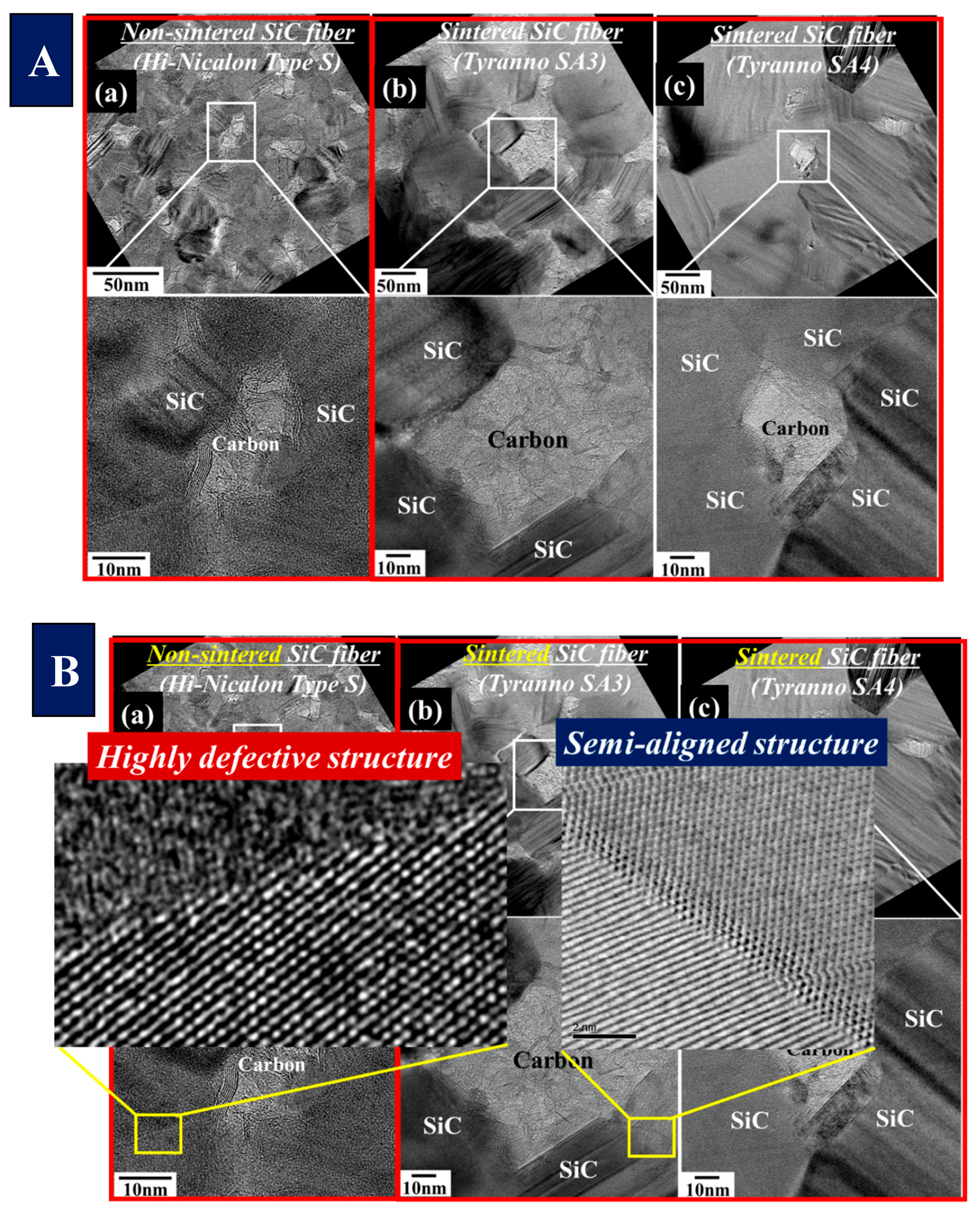

Figure 2 shows the TEM images of the internal structures of the SiC polycrystalline fibers. The images show dense structures containing excess carbon in the fibers. However, these fibers are classified into two categories: sintered fibers (Tyranno SA3 (b) and Tyranno SA4 (c)) and non-sintered fiber (Hi-Nicalon Type S (a)). Each of these grain boundary structures was unique. The grain boundaries of the sintered fibers exhibited dense structures composed of semi-aligned structures. In contrast, the grain boundaries of non-sintered fiber generally exhibit a highly defective nature [

18]. Although numerous SiC-based fiber types have been developed thus far aiming for heat-resistant materials, the characteristics of these fibers differ from one another [

19,

20,

21]. To clarify the differences in the heat resistance of SiC polycrystalline fibers, this study addresses the relationship between the abovementioned structural differences and their characteristics.

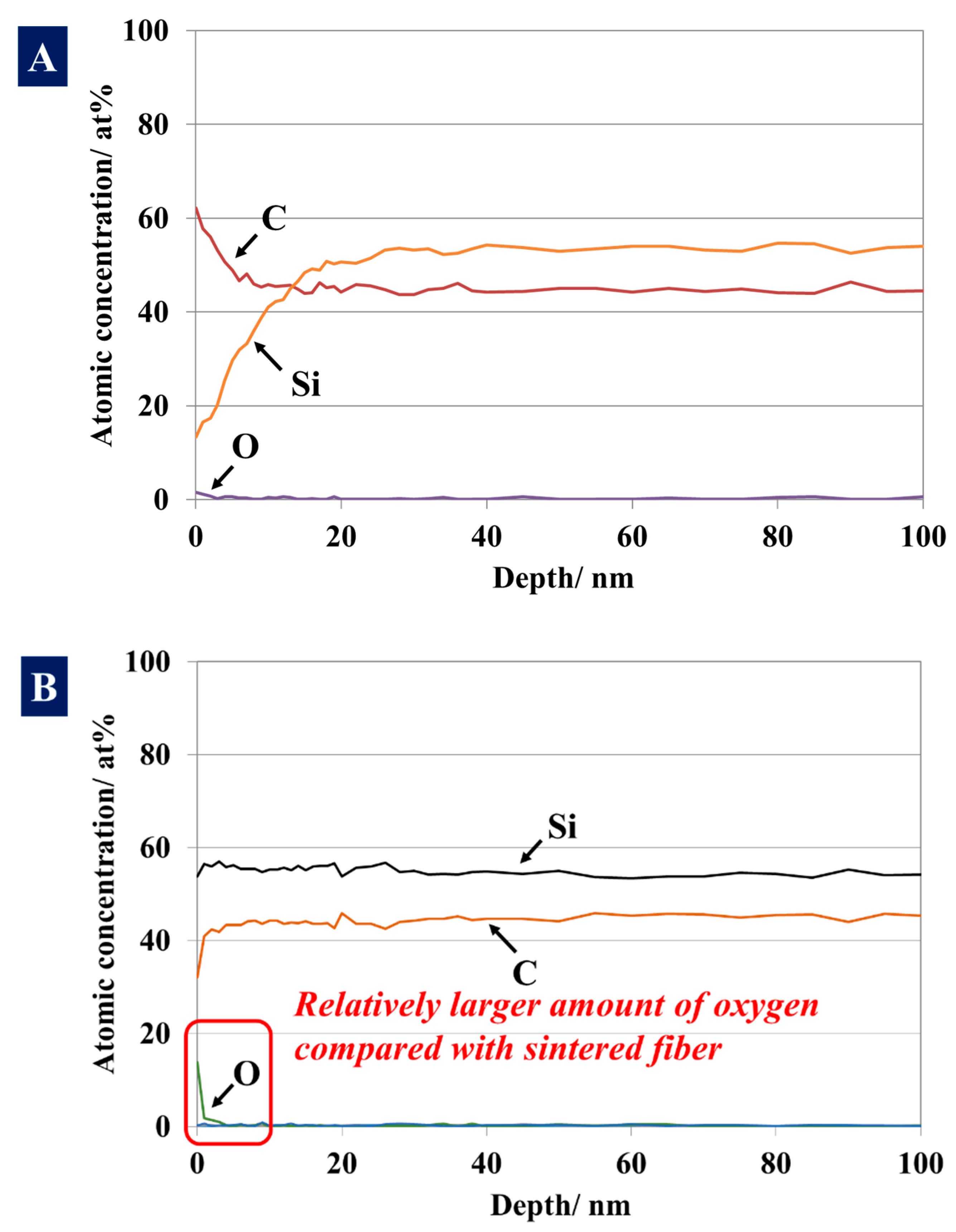

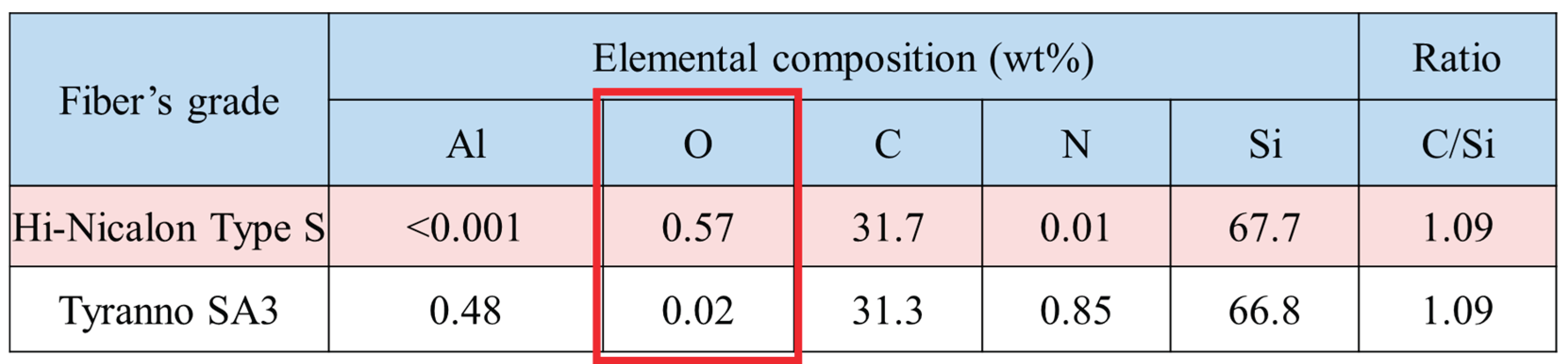

Table 1 shows the differences in the oxygen content of the sintered SiC polycrystalline fiber (Tyranno SA3) and non-sintered SIC polycrystalline fiber (Hi-Nicalon Type S). The oxygen content of the sintered fiber (Tyranno SA3: 0.02wt%) and the non-sintered fiber (Hi Nicalon Type S: 0.57wt%) differed. The surface regions of these fibers contain relatively higher amounts of oxygen than the inside (

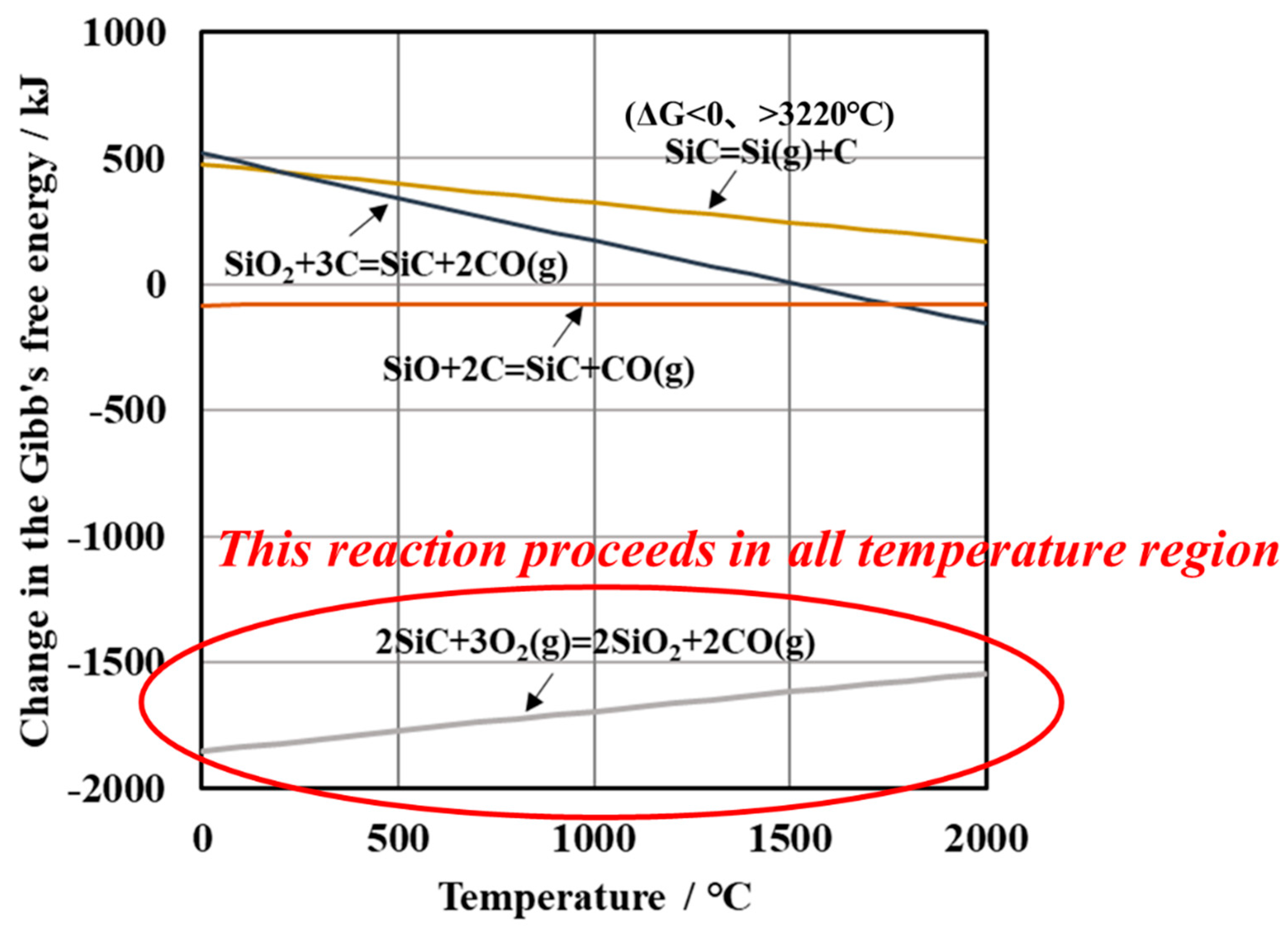

Figure 3(A) and 3(B)). This is because SiC crystal is readily oxidized in air, even at room temperature, as evidenced by the changes in the Gibbs free energy (

Figure 4) of the following reaction.

As mentioned above, the surface region of the non-sintered fiber (Hi Nicalon Type S) (

Figure 3(B)) contained more oxygen than that of the sintered fiber (Tyranno SA3) (

Figure 3(A)). In a selected area of the surface region of the non-sintered fiber (Hi Nicalon Type S), an oxygen-rich layer was observed at the SiC crystalline grain boundary (

Figure 5). These differences between the sintered and non-sintered fibers were thought to be caused by the difference in the production process, that is, the presence or absence of the sintering process. As mentioned previously, the grain boundary of the non-sintered fiber was defective compared to that of the sintered fiber. Accordingly, oxygen diffusion in the grain boundary region of the non-sintered fiber is thought to have occurred easily.

3.2. Differences in the Heat Resistance of These Fibers

Figure 6 shows the SEM images of the specimen surfaces after heat-treatment at high temperatures (1600~1900℃) for 10 hours in an argon atmosphere. The figure illustrates that, at temperatures above 1800℃, particle formations were observed on the surface of non-sintered fiber (Hi-Nicalon Type S), while no changes were observed in the surfaces of the sintered fiber (Tyranno SA3 and Tyranno SA4). Furthermore, heat treatment at temperatures above 1800℃ resulted in the formation of a carbon layer in the surface region of the non-sintered fiber (Hi-Nicalon Type S) (

Figure 7). As mentioned above, the grain boundary of the non-sintered fiber is defective compared to that of the sintered fiber; this defect results in the transformation of the residual carbon contained inside the non-sintered fiber (Hi-Nicalon Type S). However, heat treatment at temperatures above 1800℃ did not result in the formation of a carbon layer in the surface regions of the sintered fibers (Tyranno SA3, Tyranno SA4) (

Figure 8).

These results show that although the fibers were composed of SiC polycrystalline structures, the heat resistances of the sintered and non-sintered fibers differed. The differences in heat resistance between the sintered and non-sintered fibers are believed to be caused by differences in their production processes and fine structures. Hi Nicalon Type S was synthesized using melt spinning, electron beam irradiation in He, heat-treatment at 800℃ in hydrogen atmosphere (to eliminate excess carbon), and further heat-treatment in argon atmosphere at higher temperatures [

17]. Sintering was not performed during the production process. This results in defective grain boundaries in Hi Nicalon Type S. Accordingly, the oxidation of each SiC grain constructing Hi Nicalon Type S easily proceeds in air. A thin SiO

2 layer formed at the grain boundaries of the SiC grains. The formed SiO

2 layer is crystalized at temperatures above 1470℃ to prevent carbothermal reduction (SiO

2+3C

→SiC+2CO(g)), and facilitate easy transformation of excess carbon from the interior to the surface throughout the grain boundary. However, at higher temperatures above 1740℃, SiO is vaporized from the molten SiO

2 layer. For these reasons, the following reaction is expected to proceed easily at the surface at temperatures above 1800℃ (

Figure 4)).

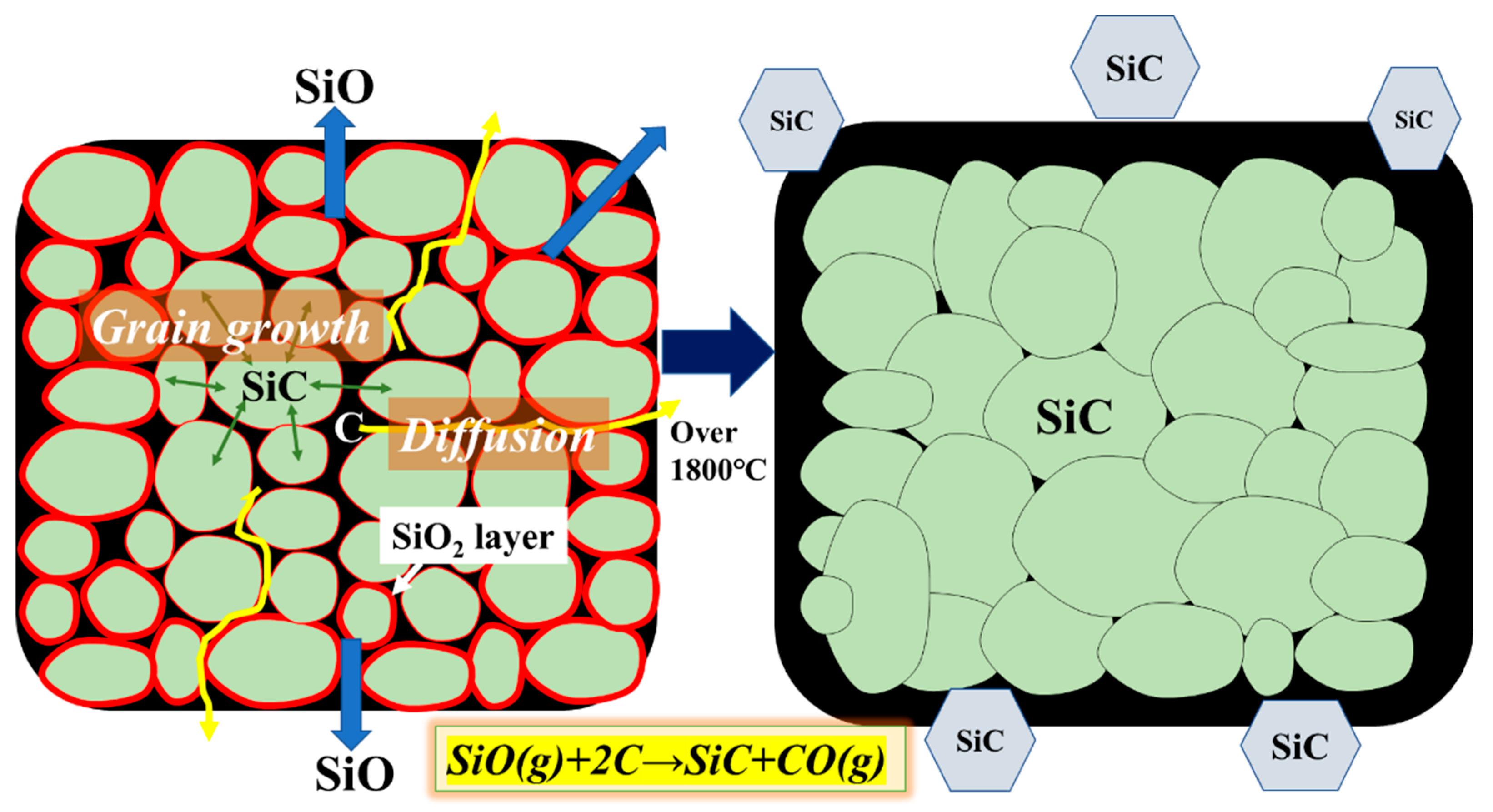

Figure 9 shows the estimated process of the morphological changes of Hi Nicalon Type S that occurred by the heat treatment at temperatures above 1800℃ for 10h in an argon atmosphere. As mentioned above, at temperatures above 1500℃, excess carbon was readily transported from the interior to the exterior through the oxidized SiC grain boundary covered with crystalized SiO

2 (cristobalite); at higher temperatures over 1740℃ a vaporized SiO gas from the molten SiO

2 layer reacted with surface carbon in accordance with the abovementioned reaction. We believed that the morphological changes of Hi Nicalon Type S at temperatures above 1800℃ were caused by the above-mentioned process. However, we concluded that the sintered, dense grain boundaries of the Tyranno SA fibers could maintain the fine structure at temperatures above 1800℃. Thus, the most crucial factor in establishing the highest heat resistance is a stable crystalline structure densified by the sintering process.

4. Perspective for Development of Future Heat-Resistant SiC Fibers

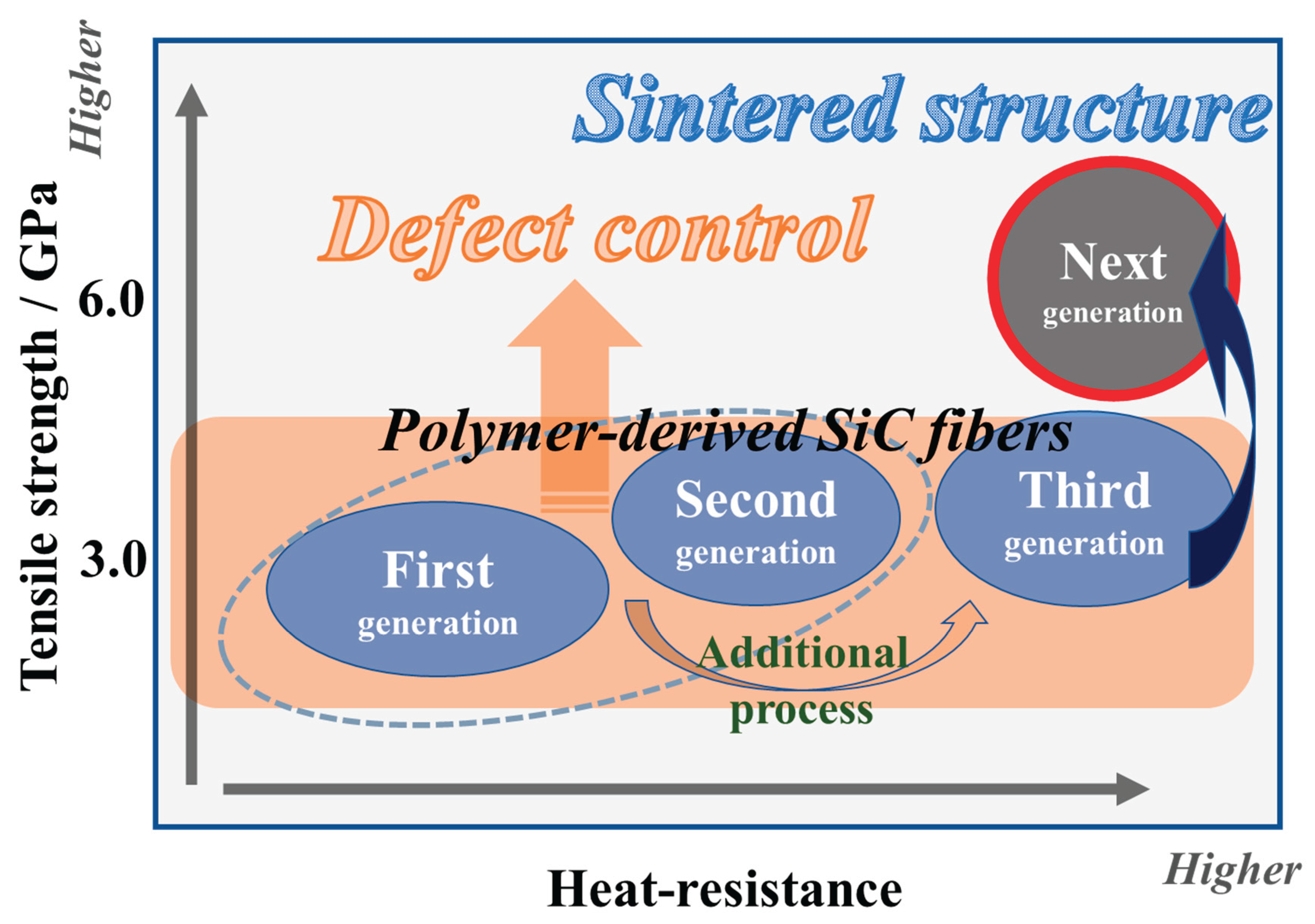

Finally, we present our perspective on the next generation of heat-resistant SiC fibers (

Figure 10). By reducing the defect size to less than 50nm, the tensile strength will increase to more than 6GPa. The sintering process is the most important factor for establishing the highest heat resistance.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We gratefully acknowledge this financial support.

References

- Z.C.Eckel, C.Zhou, H.M.Maetin, J.J.Alan, B.C.William, A.S.TObias, Additive manufacturing of polymer-derived ceramics. Science, 2016, 351, 58–62.

- E.Munch, M.E.Launey, D.H.Alsem, E.Saiz, A.P.Tomsia, R.O.Ritchie, Tough, Bio-Inspired Hybrid Materials. Science, 2008, 322, 1516–1520.

- S.Suresh, Graded Materials for Resistance to Contact Deformation and Damage. Science, 2001, 292, 2447–2451. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.Li, J.Rui, Y.Li, Y.Qiu, L.Hongli, H.Tian, Zr-doped SiOC ceramics fibers and the high-temperature thermal performance, Int.J.Appl.Ceram.Technol., 2023;1-11. [CrossRef]

- K.Shimoda, T.Hinoki, Effect of BN nanoparticle content in SiC matrix on microstructure and mechanical properties of SiC/SiC composites, Int.J.Appl.Ceram.Technol., 2023;1-12. [CrossRef]

- K.Terrani, B.Jolly, and M.Trammell, 3D printing of high-purity silicon carbide. J.Am.Ceram.Soc., 2020, 103, 1575–1581. [CrossRef]

- Y.Chen, S.Ai, P.Wang, and D.Fang, A physically based thermos-elastoplastic constitutive model for braided CMCs-SiC at ultra-high temperature. J.Am.Ceram.Soc., 2022, 105, 2196–2208. [CrossRef]

- L.C.M.Barbosa, C.Lorrette, S.L.Bras, E.Baranger, and J.Lamon, Tensile strength analysis and fractography on single nuclear grade SiC fibers at room temperature. J.Nucl.Mater., 2023, 576, 154256. [CrossRef]

- Z.C.Eckel, C.Zhou, J.H.Martin, A.J.Jacobsen, W.B.Carter, and T.A.Schaedler, Additive manufacturing of polymer-derived ceramics. Science, 2016, 351, 58–62.

- P.Wang, Y.Gou, H.Wang, and Y.Wang, Revealing the formation mechanism of the skin-core structure in nearly stoichiometric SiC fiber. J.Euro.Ceram.Soc., 2020, 40, 2295–2305. [CrossRef]

- T.Ishikawa, Y.Kohtoku, K.Kumagawa, T.Yamamura, and T.Nagasawa, High-strength alkali-resistant sintered SIC fibre stable to 2200℃. Nature, 1998, 391, 773–775. [CrossRef]

- T.Ishikawa, H.yamaoka, Y.Harada, T.Fujii, and T.Nagasawa, A general process for in situ formation of functional surface layers on ceramics. Nature, 2002, 416, 64–67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T.Ishikawa, S.Kajii, K.Matsunaga, T.Hogami, Y.Kohtoku, and T.Nagasawa, A tough, thermally conductive silicon carbide composite with high strength up to 1600℃ in air. Science, 1998, 282, 1295–1297. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryutaro Usukawa, Toshihiro Ishikawa, Effect of Al contained in polymer-derived SiC crystals on creating stable crystal grain boundaries, Int J Appl Ceram Technol, 2021, 18, 6-11.

- Toshihiro Ishikawa, Katsuya Niidome, “Easy control of surface morphology through a natural phenomenon”, Int J Appl Ceram Technol, 2023, 20, 1432-1441.

- S. Yajima, J. Hayashi, M. Omori, K. Okamura, Development of a silicon carbide fibre with high tensile strength. Nature, 1976, 261, 683–685. [CrossRef]

- H.Ichikawa, Polymer-derived ceramic fibers. Annu.Rev.Mater.Res., 2016, 46, 335–356. [CrossRef]

- M.N.Rahaman, Sintering of Ceramics (Taylor & Francis Group, 2008) pp.27-28.

- J.Braun, C.Sauder, Mechanical behavior of SiS/SiC composites reinforced with new Tyranno SA4 fibers: Effect of interface thickness and comparison with Tyranno SA3 and Hi-Nicalon S reinforced composites. J.Nucl.Mater., 2022, 558, 153367. [CrossRef]

- R.T.Bhatt, M.C.Halbig, Creep properties of melt infiltrated SiC/SiC composites with Sylramic-iBN and Hi-Nicalon S fibers. Int.J.Appl.Ceram.Tech., 2022, 19, 1074–1091. [CrossRef]

- J. Lamon, Handbook of Ceramic Composites, Springer US2005, pp. 55-76.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).