Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

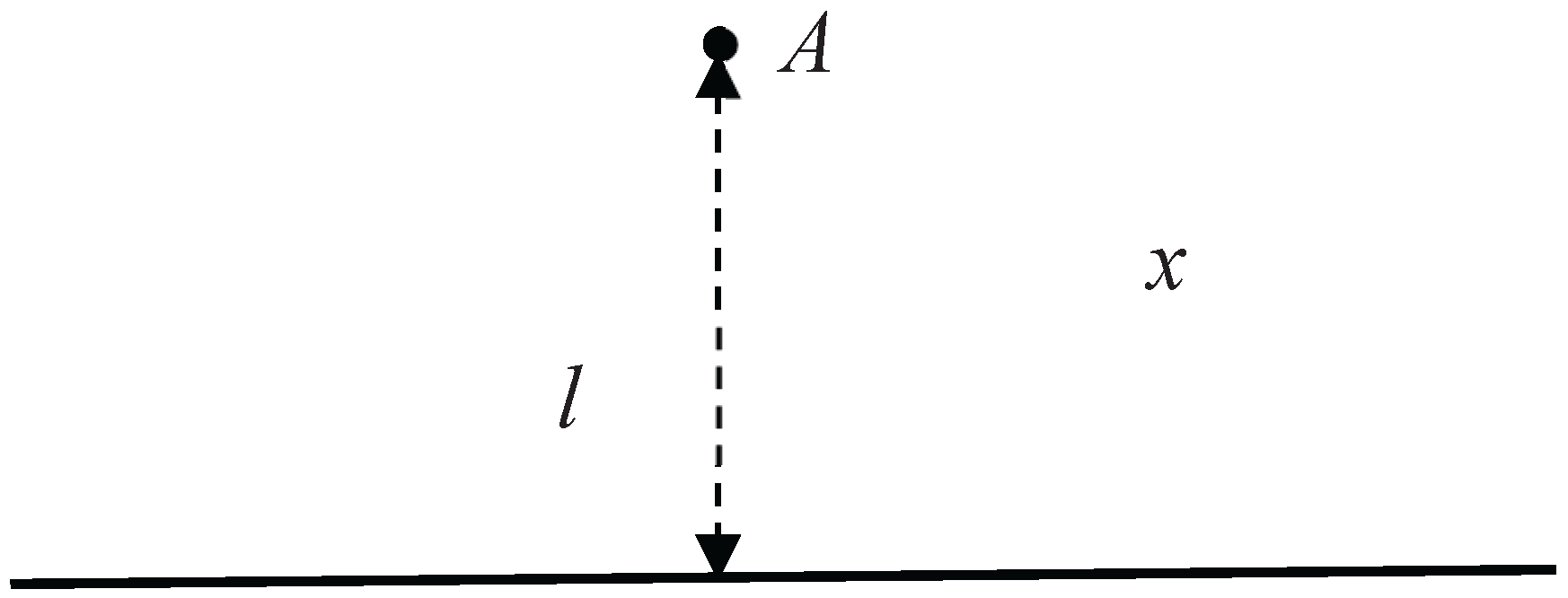

Probabilistic version of geometry is introduced. The fifth postulate of Euclid (Playfair’s axiom) is adopted in the following probabilistic form: consider a line and a point not an line, there is exactly one line through the point with probability P, where 0 ≤ P ≤ 1. Playfair’s axiom is logically independent of the rest of the Hilbert system of axioms of the Euclidian geometry. Thus, the probabilistic version of the Playfair axiom may be combined with other Hilbert axioms. P = 1 corresponds to the standard Euclidean geometry; P=0 corresponds to the elliptic- and hyperbolic-like geometries. 0 < P < 1 corresponds to the introduced probabilistic geometry. Parallel constructions in this case are Bernoulli trials. Theorems of the probabilistic geometry are discussed. Given a triangle and a line drawn from a vertex parallel to the opposite side, the event that this line is actually parallel occurs with probability P. Otherwise, the line may intersect the side or diverge. Parallelism is not transitive in the probabilistic geometry. Probabilistic geometry occurs on the surface with a stochastically variable Gaussian curvature. Alternative geometries adopting various versions of the probabilistic Playfair axiom are introduced. Probabilistic non-Archimedean geometry is addressed. Applications of the probabilistic geometry are discussed.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. System of Axioms of Hilbert-P Geometry and Its Consequences

- i)

- Group I: Axioms of Incidence. These axioms describe how points, lines, and planes relate.

- ii)

- Group II: Axioms of Order (“betweenness”). These axioms define the concept of one point lying between two others.

- i)

- corresponds to the standard Euclidean geometry: Playfair’s axiom holds always, All classical theorems of the Euclidian geometry (e.g., triangle angle sum remain valid).

- ii)

- corresponds to the elliptic-like geometry. No parallels through external points (like great circles on a sphere). holds.

- iii)

- corresponds to hyperbolic-like geometry, with the interpretation that multiple parallels are allowed. In hyperbolic geometry, through a point not one a line, but there are infinitely many lines that do not intersect the given line - i.e., infinitely many parallels. In the suggested probabilistic axiom only one parallel with probability P is possible, not multiple. So to properly correspond to hyperbolic geometry, we interpret

- iv)

- corresponds to the stochastic probabilistic geometry. Parallel constructions in this case are Bernoulli trials. Geometric consequences become probabilistic statements. Theorems take the form: with probability , there exist n successive parallels to a given line.

2.2. Physical Realization of the Hilbert-P Probabilistic Geometry

2.3. Alternative Probabilistic Geometries

2.4. Probabilistic Geometry Adopting the Fuzzy Version of the First Axiom of the Hilbert Geometry

2.5. Geometry Emerging from the Probabilistic Version of the Axiom of Archimedes

- i)

- No infinitesimal segments exist.

- ii)

- Segment lengths can be compared meaningfully.

- ii)

- Triangle inequality and other classical theorems still hold.

- iv)

- The real number system underlies the segment-length arithmetic.

- i)

- CD is infinitesimal compared to AB.

- ii)

- No finite sum n⋅CD ever gets close to AB.

- iii)

- Segment length comparison fails: the field of segment lengths is now non-Archimedean. The geometry becomes non-Euclidean in a fundamental way.

- iv)

- Triangle inequality may break down or become trivial.

- v)

- This setting resembles non-standard analysis or hyperreal geometries, where infinitesimals exist.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FP | Fifth Postulate of Euclidian Geometry |

References

- De Risi, V. The development of Euclidean axiomatics, Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 2016, 70, 591–676.

- De Risi, V. Euclid’s Common Notions and the Theory of Equivalence. Found. Sci. 2021, 26, 301–324.

- Martijn, M. Proclus’ geometrical method. In Remes, P.; Slaveva-Griffin, S. The Routledge Handbook of Neoplatonism. Routledge, London/New York: 145-159, 2014.

- De Risi, V. Leibniz on the parallel postulate and the foundations of geometry. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2015.

- Ighbariah, A.; Wagner, R. Ibn al-Haytham’s revision of the euclidean foundations of mathematics. HOPOS: J. International Society History Philosophy Science, 2018, 8, 72-117.

- Bisom, T. The Works of Omar Khayyam in the History of Mathematics, The Mathematics Enthusiast, 2021, 18 (1), 290-305.

- Petrakis, I. The Role of the Fifth Postulate in the Euclidean Construction of Parallels, ARXIV, 2022, arXiv:2208.10835.

- Greenberg, M. J. Old and New Results in the Foundations of Elementary Plane Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries, The American Mathematical Monthly, 2010, 117, 198–219.

- Díaz J. E. M. Fifth postulate of Euclid and the non-Euclidean geometries. Implications with the spacetime, Int. J. Scientific & Eng. 2018, 9 (3), 530-541.

- Hilbert, D. Grundlagen der Geometrie. Leipzig, Teubner, 1968.

- Halsted, G. B. Lobachevsky. The American Mathematical Monthly, 2018, 2(5), 137–139.

- Popov, A. Lobachevsky Geometry and Modern Nonlinear Problems. Birkhäuser, Switzerland, 2014.

- Jenkovszky, L.; Lake, M. J.; Soloviev, V. János Bolyai, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Nikolai Lobachevsky and the New Geometry: Foreword, Symmetry 2023, 15(3), 707.

- Klingenberg, W. Riemannian geometry, 2nd ed. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Ge. 1995.

- Petersen, P. Riemannian geometry, 2nd ed. Springer, New York, USA, 2006.

- Mars, M. On local characterization results in geometry and gravitation, in: From Riemann to Differential Geometry and Relativity, L. Ji, A. Papadopoulos, and S. Yamada, eds., ch. 18, pp. 541–570. Springer, Berlin, 2017.

- Ghosh, D.; Chakraborty, D. An introduction to analytical fuzzy plane geometry Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing, volume 381, Springer (2019).

- Buckley, J.J.; Eslami, E. Fuzzy plane geometry I: points and lines. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1997, 86, 179–187.

- Buckley, J.J.; Eslami, E. Fuzzy plane geometry II: circles and polygons. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1997, 87, 79–85.

- Zadeh, L. A. Is there a need for fuzzy logic? Information Sciences, 2008, 178 (13), 2751-2779.

- Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy Logic. In: Lin, TY., Liau, CJ., Kacprzyk, J. (eds) Granular, Fuzzy, and Soft Computing. Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science Series. Springer, New York, 2009.

- Tozzi, A. Probabilistic Modal Logic for Quantum Dynamics, Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hajek, P. Metamathematics of Fuzzy Logic, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1998.

- M. A. Pinsky, Stochastic Riemannian geometry, in ``Probabilistic Analysis and Related Topics,’’ Vol. 1, pp. 199-236, Academic Press, New York, 1978.

- van der Duin, J.; Silva, A. Scalar curvature for metric spaces: Defining curvature for quantum gravity without coordinates, Phys. Rev. D 2024, 110, 026013.

- Wu, X. Probability and Curvature in Physics, J. Modern Physics, 2015, 6 (15), 2191-2197.

- Durrant-Whyte. H. F. Uncertain geometry in robotics, IEEE Journal Robotics & Automation, 1988, 4 (1), 23- 31.

| Geometry | P | ||

| Elliptic | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Euclidian | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hyperbolic | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).