1. Introduction

It is factual that economics shapes human lives and businesses (Choi et al., 2025). It is also true that there are factors that shape economics, and the economics of productivity, for productivity defines the core of economics. Productivity today constitutes as one of the most important attributes governing economic activities (Tangen, 2005). Productivity is also considered the core of business, economic, and organisational activities (Leoni, 2013). It is the foundational basis of the theory of firm (Roberts, 2007; Pashkevich and Haftor, 2018). The terms “productivity” and “performance” are correlated, and closely knitted, being most commonly used in organisational, business, academic, and personal circles (Herrera et al., 2018). It often seems that these two concepts are two sides of a same coin.

Improvement in productivity is considered as the primary target of most organisations, since it is the source of “competitive advantage” for business enterprises. At the individual level, productivity does matter as well. There are certain factors that constrain the human mind and make it less active, with resultant diminished productivity. One of the constraining factors like, for example, “ineffective communication channels” for dissemination of productive information, may act as obstacles to effective learning and acquisition of productive knowledge (Chatterjee, 2014), which needs be dealt with. Here, human productivity is perceived as an “objective” phenomena, but its origin is deeply “subjective” in character—the effect of a motivated, inspired mind. Motivation and productivity are, as a result, closely related terms in human psychological perspective, as most authors, including Mustafakulova et al., (2024) indicate. They signify that there are various means of improving both human motivation and productivity, since motivation leads to improved performance and productivity among the employees. Organisations, too, meticulously intervene to bring improvements in productivity at both the individual, collective, and managerial level using motivated networks of communication, including talks, dialog sessions, lectures, and interactive seminars, that prove to be illuminating for the working minds. Organisations also employ various strategies that focus on economic incentives, e.g., perks, bonuses, salary hikes, stock options, etc. to motivate and win over their employees to render them more productive (Mustafakulova et al., 2024).

At the individual level, it is believed that some people often lose their interests in works and become lazy or indolent (Srivastava and Barmola, 2011). They feel uninspired—demotivated. They often feel that they lack the positive energy which they require to push them forward to their set goals—goals that they need to achieve. But just having goals isn’t enough: actions are necessary to achieve goals. Motivating interventions trigger the inner human instincts to help individuals become proactive so that they can pursue their goals with cheerful mind and deep interest, i.e., wilful eagerness to achieve. On the other hand, some people are highly energetic but they lack definite “visions”, and are often not ambitious enough to pursue productive ends. Still yet, there exists individuals who neither lack the energy nor goals or ambitions, but lack in willpower to get engaged in active work. Often forced by circumstances, they are compelled to work without being motivated or inspired, these individuals fail to give their 100% in output and efficiency. They tend to be less productive, where productivity means the power to produce the desired effective outcomes (Srivastava & Barmola, 2011). Here, certain motivation strategies do their job in inspiring these individuals to give their best performance and put their best effort. Motivation is a need for these individuals to enable them to do their best which they couldn’t possibly imagine under normal circumstances (Maslow, 1943). Hence, understanding the intricacies of motivation help organisations harness its power, which can be utilised in promoting productivity and fostering creativity (Desai, 2024). In fact, many researchers, including Thomas (2009), Sabir (2017), and others believe that motivation is an excellent way to improve employee productivity and performance, and there are many different ways to motivate employees.

Smart managers and organisations do their best in turn to find different ways that act as “determinants” to motivate their workforces in performing better (Syverson, 2011). Better performance leads to improvement in productivity, where ‘productivity’ in economic or organisational sense means “the ratio of output as things produced to the things required to produce them.” The factors of motivation do play substantial role in promoting productivity while driving individuals towards efficiency (Abbas et al., 2023). These factors what we may call “determinants”, has the power to shape human productivity (Syverson, 2011). Besides, as Danlami et al., (2018) indicate, productivity has important implications for organisations and businesses. Increase in productivity, according to Danlami et al., (2018), signifies higher output, cost reduction through economies of scale, reduction in product price, more revenue and higher profits for the organisation, and higher wages for the employees. All these factors are correlated with each other, and motivation plays a crucial role in triggering productivity, which is associated with all these residual effects. Therefore, it may be assumed that motivation is a determining factor—the power of employee efficiency and productivity.

But what “power” are we referring to, and “how” they shape human productivity? In this paper, we examine these two aspects in some detail. Coupled with this, we also examine the role of “ambitions” in shaping human productivity, since it’s an important factor to consider in conjunction with motivation. Ambition is an aspiring sense of wilful desire for success and achievement. It is also a form of drive—i.e., motivation, in that sense that it pushes the individual towards achievements. According to Rhode (2021), ambition is a timeless concept, with people having it from very ancient times and utilising its power in fulfilling certain material or psychological needs.

2. Determinants of Productivity

There may exist as many determinants or factors of productivity, or those that shape the course of actions that lead to improvement in productivity levels (Syverson, 2011). But given all other determinants separately or in combination, there is one factor which is arguably the most relevant among them in promoting productivity. This factor is “inspiration” or “motivational drive”, which we often ignore or care less about, but it is too often talked about. Human inspiration is considered the “product” of a moment: it is a sudden upsurge of an instinct, which drives us to action (Maslow, 1943). Inspiration may lead to the development of ambitions—or aspirations of any other kind or other kinds of emotions that could be set on fire by an excited state of the mind. It is a cognitive booster which induces positive states that result in emotional drive. Inspiration fosters development of resilience (Desai, 2024). When inspiration drives us to action, it influences us to make a choice, which we should examine closely and earnestly while making a decision (Edwards, 1954), for we often need to make judgments under uncertainty, without having complete information at hand (Tversky, Kahneman & Slovic, 1982). Making decisions based on incomplete information may involve risk taking as well. Now, either individuals become overly optimistic or overly cautious while making decisions that involve risk, as observed by Kahneman & Lovallo (1993) from a cognitive viewpoint. Which means that, one is driven by emotional factors to make a decision. One should examine,—as well, the real motivation in making a choice, for it may lead to “poor” decision making—a failure, or catastrophe. On the other hand, inspirations and aspirations can make us become more productive, proactive, and a motivated go-getter. If an individual is motivated to take actions in order to become productive to achieve some definite ends, she must weigh the outcomes before taking the risk in making the decision to do so.

In short paper, we shall examine the role of aspiration, inspiration and ambition in shaping human productivity. We shall also inquire about how “inspirations” transform us to become productive and efficient. In consideration of choices while making decisions, we cannot leave productivity to the affairs of fate. When we have a productive aim, it is pertinent that we should follow the path to achieve that aim. In such instances, it is imperative to be guided by our innermost voice of wisdom and intelligence, i.e., what does our deepest instincts tell us to do. The ultimate goal is to make a productive choice based on which we can “maximize” the utility attached to an outcome. Herein, a productive choice is a functional probability—a state of possibility that needs be achieved by choosing an “option” to make a decision. The role of aspiration in this context, however, is nondiscretionary.

3. Productivity, Its Categorisation, Ambition, and Choice of Actions:

Productivity can be categorised into personal, organisational, socio-cultural, and national productivity. In this research, we shall consider personal and organisational productivity as our theme to examine the effect of as well as the impact of motivation on productivity levels. There are numerous factors and their sub-elements that determine productivity (Herrera et al., 2018), which may be classified into following six categories:

Individual factors: i.e., skills, competence, task habits, etc.

Endogenous factors: intelligence, focus, willpower, etc.

Exogenous/environmental factors: economic conditions, market trends, technology and socio-cultural factors,

Organisational factors: incentives, perks, leadership, work environment, management practice, work culture, technology adoption, communication network, etc.

Task-related factors: complexity of the work, goals, autonomy, positive work culture, innovation, etc.

Motivational factors: “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” motivational factors (Maslow, 1943; Thomas, 2009), enthusiasm to work, willingness, positive feedbacks, recognition and appraisal, promotions, career growth, sense of belonging, workforce support for wellbeing, salary, bonus and other non-pecuniary incentives, etc.

The emergence and applications of AI-based systems has redefined the definition and idea of productivity today. We have become more productive—no, we have programmed more capability into machines that has expanded their functional horizon, making them faster, efficient, and more productive than ever before. It has now become impossible for anyone to match the speed and efficiency of AI bots, in terms of productivity and knowledge generation. AI-driven systems now have the capability to turn a system of equations into a software program, create a program from an entire research paper, design games based on ideas inherent in research papers, and many other augmented capabilities. Their axis of productivity has tilted on the right and they have learned to become more productive and powerful. However, as human beings, we, too, do have some reservations about machine productivity as well. As human beings, we still value productive efforts, as previous studies have concluded (Stafford and Cohen, 1974). An individual is still highly valued for his or her intelligence power, wisdom, ideas, and productive capabilities. Why? Because “power” has value embedded in it. And there’s power in productivity. And the power of human intelligence is not yet fully realised.

On the other hand, we regard productive value as an asset, like that of a code, program, knowledge, wisdom, and of course, ideas. But beyond all these factors, there is another subjective factor seldom valued: Inspiration or Motivation. Inspiration has got a positive role to play in shaping human productivity (Uka and Prendi, 2012; Ilesanmi, 2016; Ahmed et al., 2024), a fact which is hard to ignore or disregard. To nurture a productive frame of mind, it is necessary for a human being to get inspired and motivated. Even if we do attribute higher values to actions and productivity, we cannot disregard the motivational instincts that have the power to transform us into more productive beings. For, it is productivity which reflects our actual “frame of mind”.

4. The Core of Productive Essence

The dominating influence of a productive frame cannot be imposed but it is voluntary in the context of making a choice based upon instincts and inspirations. Which means that there must be an ideal way to invoke our inspiration in transforming the latent potential to a dynamic state: i.e., a productive state. The goal is to understand on ‘what soil the seeds of productivity grows’. I strongly believe that we as humans possess inadequate knowledge of human potential and productivity. The elements of productive manifestations by which we understand output, efficiency, and yield lie beyond the realms of our simple understanding of productivity sensed or perceived in economic terms. That is one part of the story; the other part being that, we still do not have the “complete knowledge” of productive wisdom nor its essence, even though some of us might have become masters of productivity. The perfect knowledge of productivity is far from being found—, but it is continuously sought for. Human potential—in this respect, has a definite role to play in making us more productive given that it is invoked and triggered by inspiring thoughts and ambitions. Ambitions drive us forward. These may be in the way of pursuing certain goals which one has to attain. Ambitions shape human morality and guide actions.

The core of productive essence and value lie in its utility, not in any ideology, as it must be understood. On the other hand, productive decisions have definite utilities which must be understood with discretion to form judgments. But it is also true that its might not be possible to learn all about productivity and human potential—for such knowledge are unending, illimitable, and essentially vast, but measureable. But even if it possible to learn all about productivity than could be known or taught, there will still remain something to be learnt. This makes the fertility of the most powerful and learned minds accountable for being marked out as prominent—conspicuous, and which provides us with the clear perception of what is meant by productivity. The role of aspiration cannot be discounted in this context, and which is the subject of study in this research. In the next two sections, we explicate the role of aspiration in shaping human productivity, and how they are linked to the realisation of true human potential.

5. Role of Motivation in Shaping Human Productivity

Do we need to be inspired to act or become (more or less) productive? What’s the role of “inspiration” in driving us to actions? In this paper, we shall briefly examine the role played by inspiration (drives and motivations) in making us become more productive, proactive. Productivity can only be boosted if we possess the clear conception of the methods of production, i.e., how to do or accomplish certain tasks flawlessly and with confidence, without committing errors. This “how” means exactly ‘in what way’ one can achieve the set goals or accomplish a given task. This brings up confidence and inspiration to the forefront. Confidence breeds inspiration, and if one is inspired to do something, one gains the confidence necessary to approach the desired objective. But the interplay between these two factors are highly subtle, as there are other intermediate factors which come into purview, and needs be examined as well. For the share of this inquiry, we shall focus chiefly on the factor of motivation—i.e., inspiration or drive that is often a prime precondition to become more productive. We must not forget the impulse behind an action.

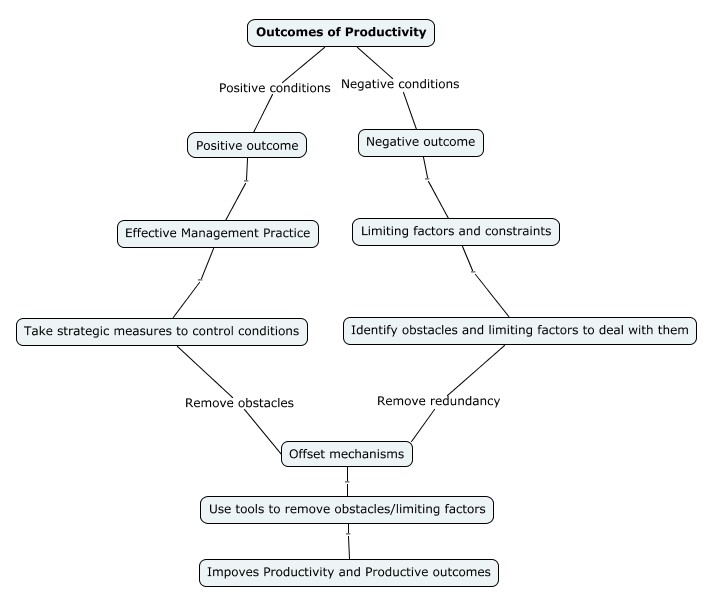

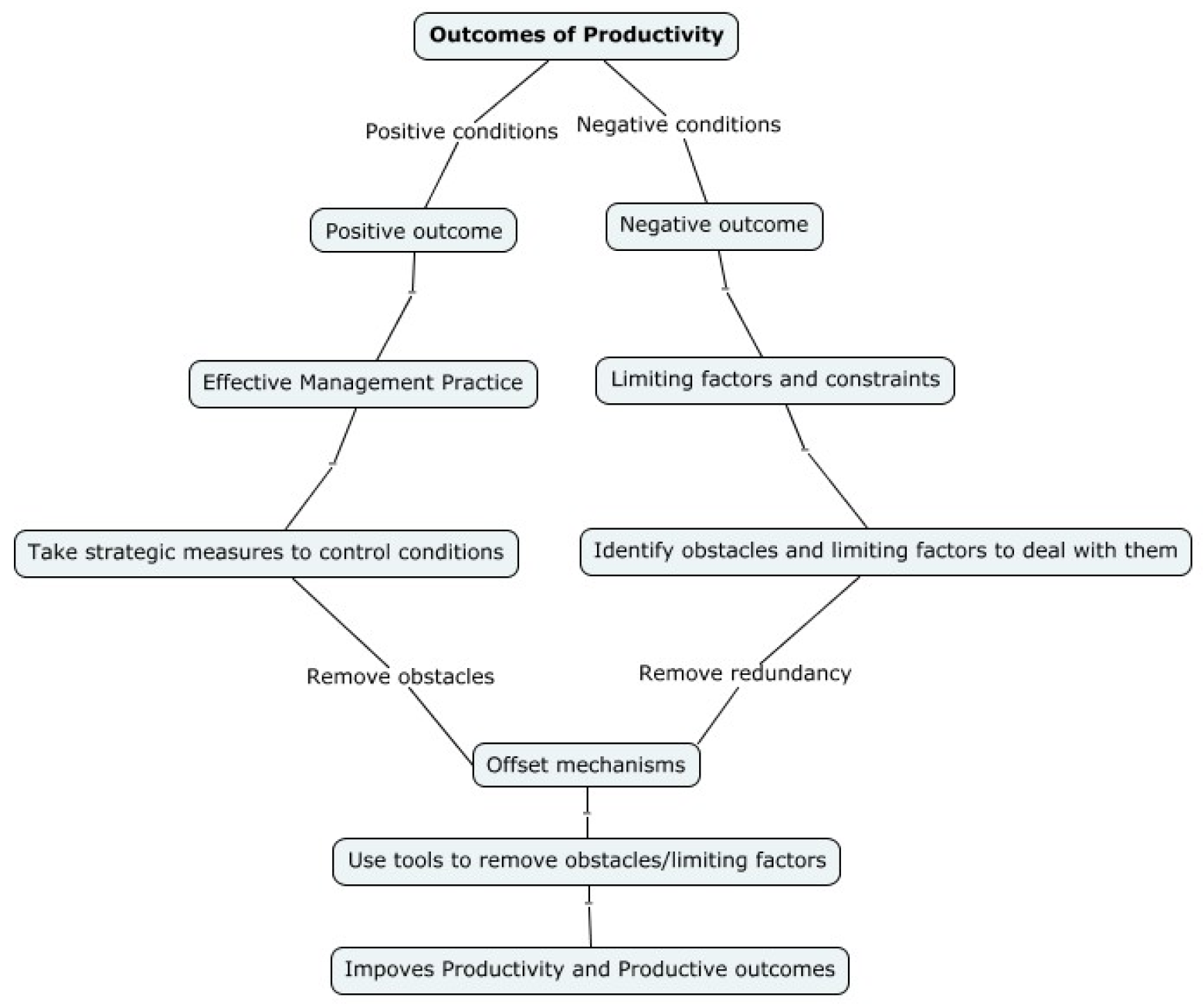

All things are controlled by conditions. The first “precondition” in promoting productivity is the identification and removal of

obstacles that act as “limiting factors” or

constraints (Chatterjee, 2014). The offsetting mechanism must be at hand to overcome these obstacles in order to deal effectively with the limiting factors, for these factors render us inert or unproductive, or simply, they cause to impede our efficiency level at work and practice. Equally important, removal of unnecessary actions and redundant processes often do a great deal to bring improvements in our productivity level. Besides, it is also a well knowledge fact that effective management practices help enhance productivity (Siebers et al., 2008). Better if, strategic measures could be devised to deal effectively with emerging obstacles to increasing productivity. We can control a problem if we are able to find a solution to it. Barriers to productive actions can be removed as well, by removing the known obstacles to improvement. This will help accrue good productive merit. In

Figure 1 below, using a chart, we have attempted to explain the productivity factors and how removing obstacles and redundancies can improve outcomes of productive processes.

It needs be remembered that a set of actions is connected with a method of practice. Productive activities lead to the acquisition of good experience of actions. Besides, mastering methods helps gain control over actions, and when we have control over actions, we can expect desirable results as well. Productivity is enhanced when we are able to master the methods that control actions. The pure concept of productivity should be clearly understood at first, for relationship is marked by “closeness” to related concepts. This entails connections, and there is power to be harnessed from a synchronised system of connections. It is also necessary to establish the range of all possible relations (connections) that can operate between concepts. It helps us to understand the general motif of a “method” of practice. The result being that, it leads to the emergence of position productive of good actions—aka increased output and efficiency. The entire mechanism is itself inspiring, since without this inspiration it might not be possible to delve deeper into the workings of a method. This inspiration is the material nature of thought resulting in positive vibes, or instincts—the necessary drive, which is the essence of our atomic existence. From such an actuality, the power of productivity emanates. The goal is to harness this power—the energy inherent within us in latent form as human potentiality, which must be triggered to effect positive actions. And without this essence of potentiality, nothing of value is conceivable. It this this factor of inspiration which we mostly disregard with regard to productivity of actions.

6. Motivation: Is It a Force more Potent than Action?

We come to know by “experience” what is required to increase our productivity levels. But how to acknowledge the fact about what makes us active, or what drives us to become productive? To attain more practical results by means of productive efforts, synchronicity is the key factor connecting productive events with purposes, and where time is synchronous with events that follow a particular order of sequence. Here again, beyond actions and purposes, inspiration is the key driving force constituting the symbol of productive essence. The essence of productivity is to establish synchronicity by connecting with time productive actions being undertaken with a definite purpose, the actions being motivated by “moments” of inspiration. Moment indicates time. The impulse of a particular ‘moment’ inspires one to become productive. If we can trace the source of this inspiration, a lot can be deduced about how it plays a significant role in shaping human productivity.

In fact, inspiration is a force more potent than action. But how is that possible? The arguments in favor of this assumption states that

“Without being motivated by the will to empower the mind with the urge to act, it is impossible to become active”.

But this theory has not been explicitly accepted as truth, but rather it has been preposterously rejected by many scholars, who prefer a more normative account of productivity. Just as there’s a difference between “is” and “ought”, so there exists a big difference between considering the origin of productive action being an act of psychological response to some teleological impulse, rather than it being a consequence of pure inspiration. Now, it appears that it is impossible to avoid the subjective aspects of the mind—the mental frame that also concerns the practice of self-discipline for productivity enhancement. Therefore, we cannot but avoid to exclude the two subjective states of the mind—“inspirational drive” and “self-control” (self-discipline) in defining the enhanced productivity frame, and which justifies the role of inspiration in shaping human productivity, albeit, to some extent. And it also explains why inspiration is a more potent force than action. However, it does leave the most esoteric subject on human productivity untouched: the wisdom that “inspires” the mind to become active.

7. Ideas Fuelling Human Productivity

Some ideas are compelling. The ‘power’ of productive ideas is compelling as well: it is an outcome of productive thinking. When ideas propel actions, it must be observed if those ideas themselves are productive in nature, i.e., if such ideas are capable of augmenting our productive capabilities. And now we are acquainting ourselves with the productive capabilities of AI Chatbots and AI-based systems, their speed, efficiency, and precision all packaged into a formidable “system of intelligence”,—far

faster and more

productive than any other machines we could think of. Besides, the widespread adoption of general artificial intelligence (GAI) in diverse professional fields indicate the critical role of AI-based applications in boosting human, industrial, and personal productivity (Naqbi, Bahroun and Ahmed, 2014). But we shall not forget that these artificial capabilities are the results of coding and programming,—human endeavors, and the results of fine-tuning the codes to expand the horizon of their productive capabilities. AI capabilities are also expanding the horizon of economic possibilities (Brynjolfsson, Rock, Syverson, 2018) and generating new business opportunities as is evident from the

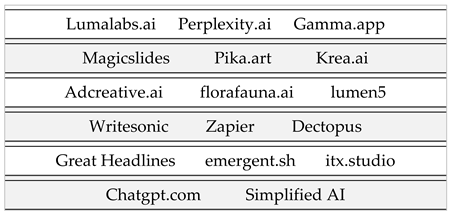

xyz.ai boom (AI start-ups) we are observing today (see

Table 1 below, which lists some AI-based tools of learning and productivity).

Now, the human mind is not programmable in a manner analogous to computers, but it is, nevertheless, a challenging issue for the humanity to draw near and match with the productive capability and speed and efficiency of machine intelligence. This factor need not be undermined nor worried about, because with the power of human creative thinking and ideation, things like these could be sorted out someday. However, when speed is an intrinsic factor of productivity, and viewed as a need to accomplish certain tasks, its requirements are restricted or limited to the performance of an individual or a system, since according to Witt and Cunningham (1979) speed requirements limit the performance of older people. Speed requirements also limits the productivity capacity and performance of individuals when compared to other advanced AI-based agents. But the way out of this problem is bonding and synergy: adoption of AI tools to boost and augment productivity.

So, concerning the speed of productivity, AI systems score far better when compared to humans. Now, this could be a possible scenario in near future where human beings, by the power of their cognitive abilities, could match the speed and efficiency of machines, where we can foresee the important role of ideas in powering human productivity. But this may not be a reality to be achieved sooner, or more willingly.

On the production frontiers, productive efficiency matters (Lovell, 1993). For example, a computer programming code or an algorithm can make a real difference today: it can make a program become more efficient, run faster, make it more error-free, or render a system more productive and precise. Codes can bring about diversity in functions in AI-based systems and expand their productive horizons. It may thus be assumed that the applications of AGI in most professional frontiers is increasing overall productive efficiency. In similar tune, Gao and Feng (2023) report about the effects of AI on industrial productivity, with adoption and penetration of AI technology resulting in substantial increase in total factor productivity (TFP). But what noetic tools of cognition do we, humans, have with us to match the efficiency of machine intelligence if we decide not to depend entirely on them? The answer to this question is—thinking, reasoning, and the power of ideation and our natural intellect. All AI tools and development of AI systems are the brainchild of human intrinsic intelligence.

Besides thinking, speed plays a defining part in determining success and efficiency of a system or an individual, or both—and AI systems are, in general, incredibly fast in the matters of promptness and rapidity in production and analysis. How do they acquire this incredible power of speed? What makes them so fast? On account of intelligent algorithms and systems design, their mode of operation occurs at lightning speed. AI systems are getting faster on account of Quantum computing, which is testing the boundaries of possibilities. Combination of quantum computing and AI have resulted in quantum leap in intelligence (Rayhan & Rayhan, 2023), as more faster and advanced systems are being designed or proposed to handle more complex problems. They work with invincible speed and accuracy. And then, we have already vibe coding in operation which has further expanded the capabilities of machines, thus creating more diverse opportunities for us as well. Vibe coding is based on the principles of agentic coding and autonomous generation of codes and programmes given a few directional prompts using common human–computer interface (Sapkota, Roumeliotis, & Karkee, 2025). The AI system is able to generate codes and create an entire executable program all on its own from given prompts. Here, technology plays the role of a motivating determinant of productivity (Yoo, 2021). Given all these power of precision, speed and efficiency, it must however be kept in mind that sometimes, AI agents and Chatbots do commit errors (Cao, Li, Jiang, 2024; Tan, Jiang, Zhu, 2024) under certain circumstances.

The Limits of Intelligence:

Do all these denote that human intelligence has reached the threshold of noetic (

intellectual,

cognitive) capability? Not likely so. For the very reason that humans are not designed exactly in a manner alike computers or AI-driven Chatbots, but in fact, the robots are being made to do their best in emulating human capabilities. Hence, we must acknowledge the productive power and value of programmes and codes, the codes encoded by human intelligence. So, where do we stand? We stand on the SHOULDER of IDEAS. Ideas can be turned into productive actions, digital apps, or programmes using codes;

Apps or applications boost our productivity levels, for these are tools of noetic-cognitive development. Enriched ideas can be used as a fuel to power human productivity. In fact, researchers like Ekwueme, et al., (2023) look with optimism about how AI tools can stimulate human productivity and bring efficiency in operations, by asking people to move beyond the fear of job losses and feel positive while embracing the emerging AI technologies.

There is wisdom and intelligence to be found in ideas. Ideas inspire and motivate us to act or become productive. One may reason it in this way: if AI capabilities are improving day by day with more and more powerful algorithms driving them (Growiec, 2023), why not human capabilities? This capability development differs from mechanisation and automation—that are straightforward, as Growiec (2023) clearly demarcates between these three forms of productive development: industrialisation, mechanisation, and automation. Indeed, human capabilities develop over a considerable period of time through persistence practice and effort (Kuklys, 2005), but not in a manner as the AI systems do. AI systems are able to improve their performances based on digital encoding of programs and datasets. However, AI-based machines, too, do not develop all the capabilities overnight. Advancement in machine vision, natural language processing (NLP) and other aspects took considerable amount of time before they have managed to reach today’s proficiency levels. Similarly, organisations, firms, and institutions of higher learning are deeply engaging in human capability development through organised dynamic training programs aimed at improving productive capabilities of their workforces, students, learners, etc. It needs be seen what more factors will drive global growth and productivity in this age of digital technology and artificial intelligence (Growiec, 2023). The one thing more that will always be required to stimulate productivity is motivation.

8. Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined the role of motivation in shaping human productivity. Motivation has always played an important role in triggering human passions, interests, and desires to achieve goals and objectives, and thereby pursuing people to follow their ambitions in becoming dynamic and more productive. On this frontier, the role of AI system in augmenting human productivity has been discussed, which too, is playing a role in shaping human productivity. Besides, the rationale for including AI as a determinant of productivity owes to the reason that technology and technological breakthroughs are highly motivating factors and technology greatly contributes to the growth of economic productivity (Solow, 1957). In this respect, the analysis directs to that frontier where motivation, coupled with technological advancements, are more likely to play an increasingly greater role in stimulating performance and productivity, and hence, it needs to be considered more diligently.

Acknowledgements

The author extends his gratitude to the V.S. Krishna Central Library, Andhra University for providing access to conduct this research.

References

- Abbas, S.A.; Kusumawardani, Z.N.; Suprayitno, N.F.; Jafar, N. Driving Factors of Motivation and Its Contribution to Enhance Performance. Innovative: Journal Of Social Science Research 2023, 3, 7266–7280. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Wong, W.K.; Riaz, S.; Iqbal, A. The role of employee motivation and its impact on productivity in modern workplaces while applying human resource management policies. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (Kuwait Chapter) 2024, 13, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Al Naqbi, H.; Bahroun, Z.; Ahmed, V. Enhancing work productivity through generative artificial intelligence: A comprehensive literature review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Rock, D.; Syverson, C. Artificial intelligence and the modern productivity paradox: A clash of expectations and statistics. In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.C. When chatbots make errors: Cognitive and affective pathways to understanding forgiveness of chatbot errors. Telematics and Informatics 2024, 94, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Managing Constraints and Removing Obstacles to Knowledge Management. IUP Journal of Knowledge Management 2014, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W. C.; Lam, L. C.; Chang, C. I.; Jie, F. X. How Economics Shapes Life and Business. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. The psychology of inspiration: its impact on creative processes. Shodh Sagar Journal of Inspiration and Psychology 2024, 1, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, W. The theory of decision making. Psychological bulletin 1954, 51, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekwueme, F.; Areji, A.; Ugwu, A. Beyond the Fear of Artificial Intelligence and Loss of Job: a Case for Productivity and Efficiency. Qeios. July 2023, 24, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Feng, H. AI-driven productivity gains: Artificial intelligence and firm productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15(11), 8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growiec, J. What will drive global economic growth in the digital age? Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics & Econometrics 2023, 27, 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, T.F.; De la Hoz Granadillo, E.; Gómez, J.M. Productivity and its factors: impact on organizational improvement. Dimensión empresarial 2018, 16, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilesanmi, O.A. Role of motivation in enhancing productivity in Nigeria. behaviour, 8. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Lovallo, D. Timid choices and bold forecasts: A cognitive perspective on risk taking. Management science 1993, 39, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklys, W. Amartya Sen’s capability approach: Theoretical insights and empirical applications. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leoni, R. Organization of work practices and productivity: an assessment of research on world–class manufacturing. In Handbook of economic organization. Integrating economic and organization theory; Grandori, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar, 2013; pp. 312–334. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, C.A.K. Production Frontier and Productive Efficiency” The Measurement of Productive Efficiency, Oxford University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. “The Theory of Human Motivation”. Psychological Review 1943, 50, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafakulova, S.; Asrorova, A.; Ibragimov, K. How to Improve Employee Motivation and Productivity. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pashkevich, N.; Haftor, D. Complementarities of knowledge worker productivity: Insights from an online experiment of software programmers with innovative cognitive style. Contemporary Economics 2020, 14, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayhan, A.; & Rayhan, S. (2023). Quantum Computing and AI: A Quantum Leap in Intelligence. AI Odyssey: Unraveling the Past, Mastering the Present, and Charting the Future of Artificial Intelligence, 424.

- Rhode, D.L. Ambition: For What? Oxford University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J. The modern firm: Organizational design for performance and growth; Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sabir, A. Motivation: Outstanding way to promote productivity in employees. American Journal of Management Science and Engineering 2017, 2, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. Vibe coding vs. agentic coding: Fundamentals and practical implications of agentic ai. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.19443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebers, P.O.; Aickelin, U.; Battisti, G.; Celia, H.; Clegg, C.; Fu, X. ;... & Peixoto, A. Enhancing productivity: the role of management practices. Submitted to International Journal of Management Reviews, Forthcoming 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R.M. Technical change and the aggregate production function. The review of Economics and Statistics 1957, 39, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Barmola, K.C. (2011). Role of motivation in higher productivity. Management Insight, 7, 63-82. Uka, A.; & Prendi, A. (2021). Motivation as an indicator of performance and productivity from the perspective of employees. Management & Marketing, 16, 268-285.

- Stafford, F.P.; Cohen, M.S. A model of work effort and productive consumption. Journal of Economic Theory 1974, 7, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syverson, C. What determines productivity? Journal of Economic literature 2011, 49, 326–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Jiang, C.; Zhu, Y. To Err is Bot, Not Human: Asymmetric Reactions to Chatbot Service Failures. In Wuhan International Conference on E-business; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 396–407. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.T. Intrinsic Motivation at Work: What Really Drives Employee Engagement, 2nd ed.; Berrett-Koehler Store, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D.; Slovic, P. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. 1982; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Uka, A.; Prendi, A. Motivation as an indicator of performance and productivity from the perspective of employees. Management & Marketing 2021, 16, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, S.J.; Cunningham, W.R. Cognitive speed and subsequent intellectual development: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Gerontology 1979, 34, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S. Comparison of artificial intelligence and human motivation. Technium Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 25, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).