Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

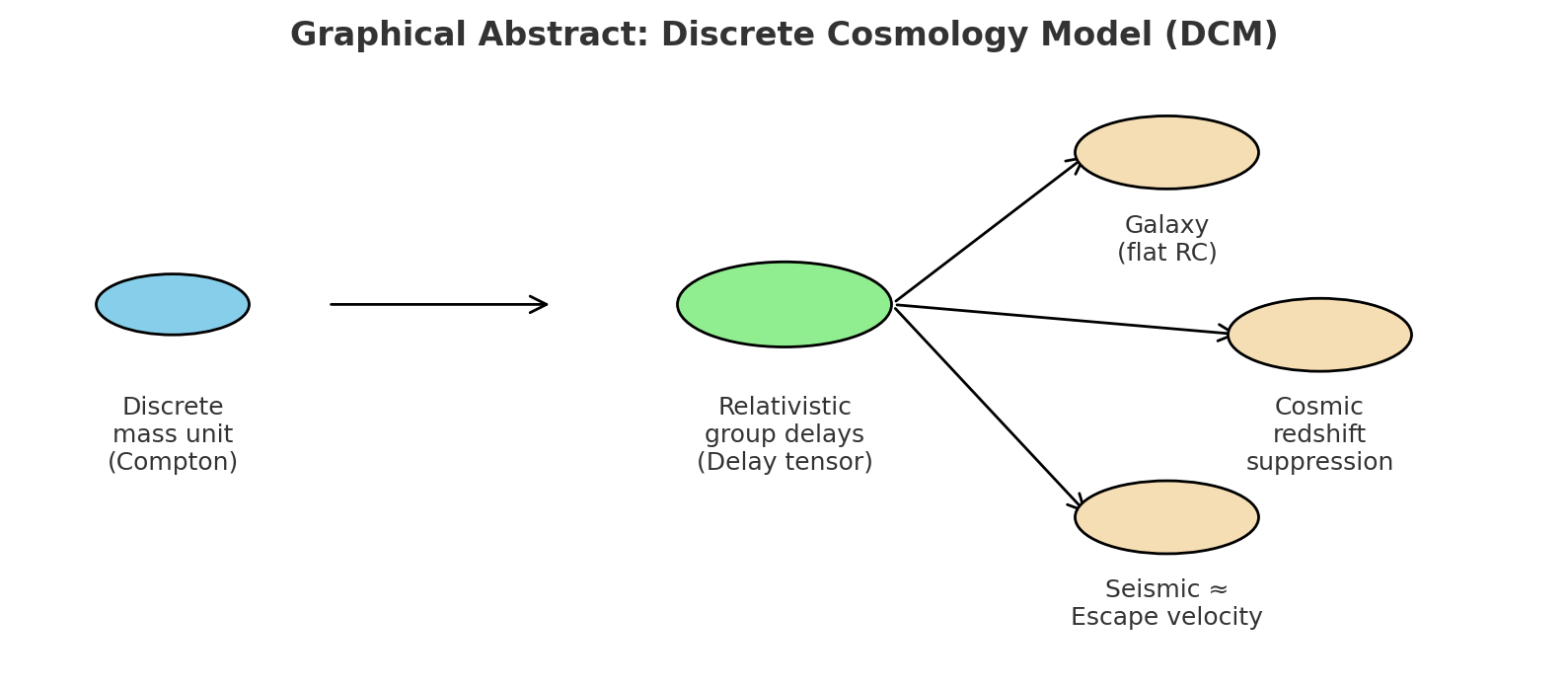

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Physical Principles

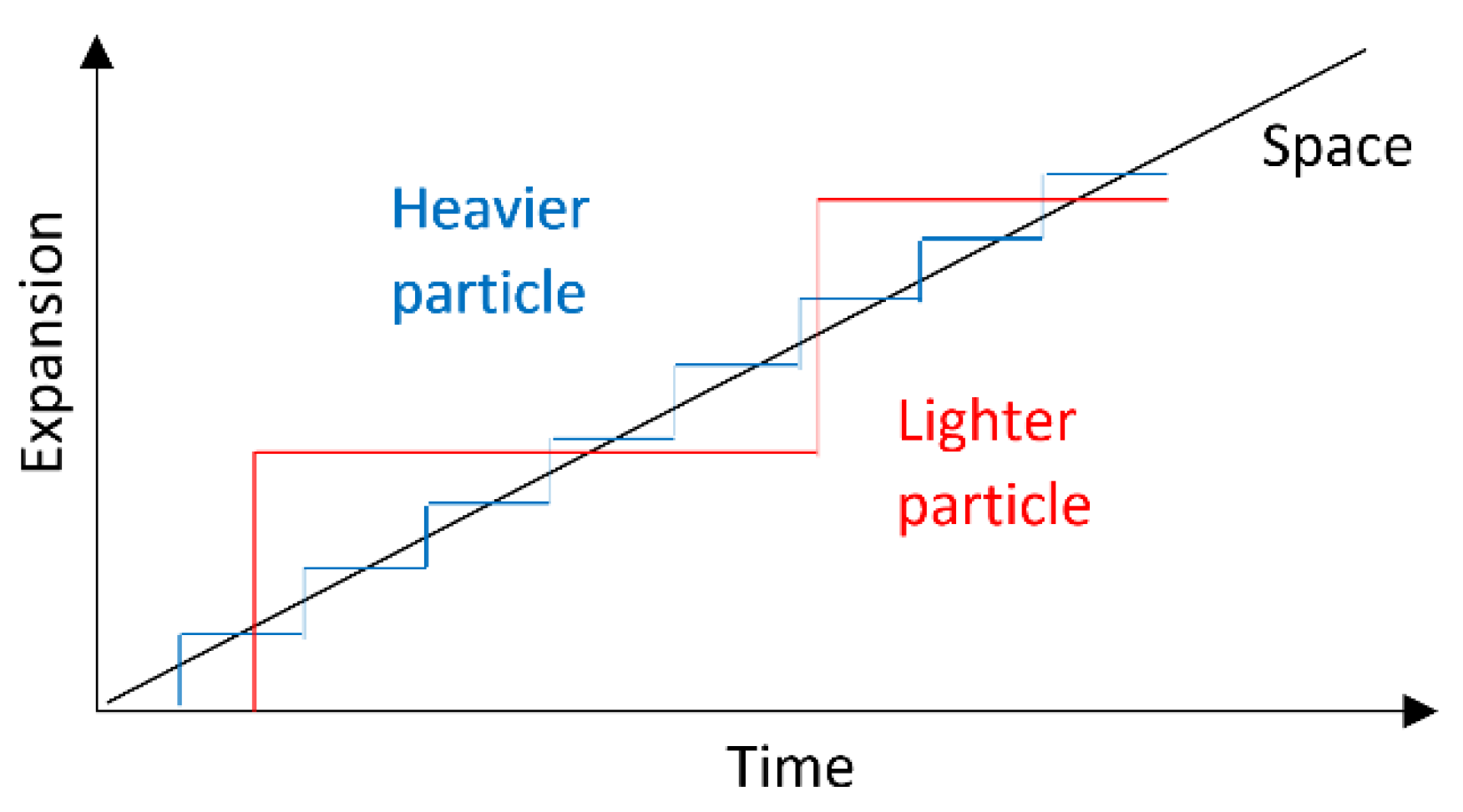

2.1. Discrete Expansion Lag

2.2. Expansion Delay and Group Phenomena

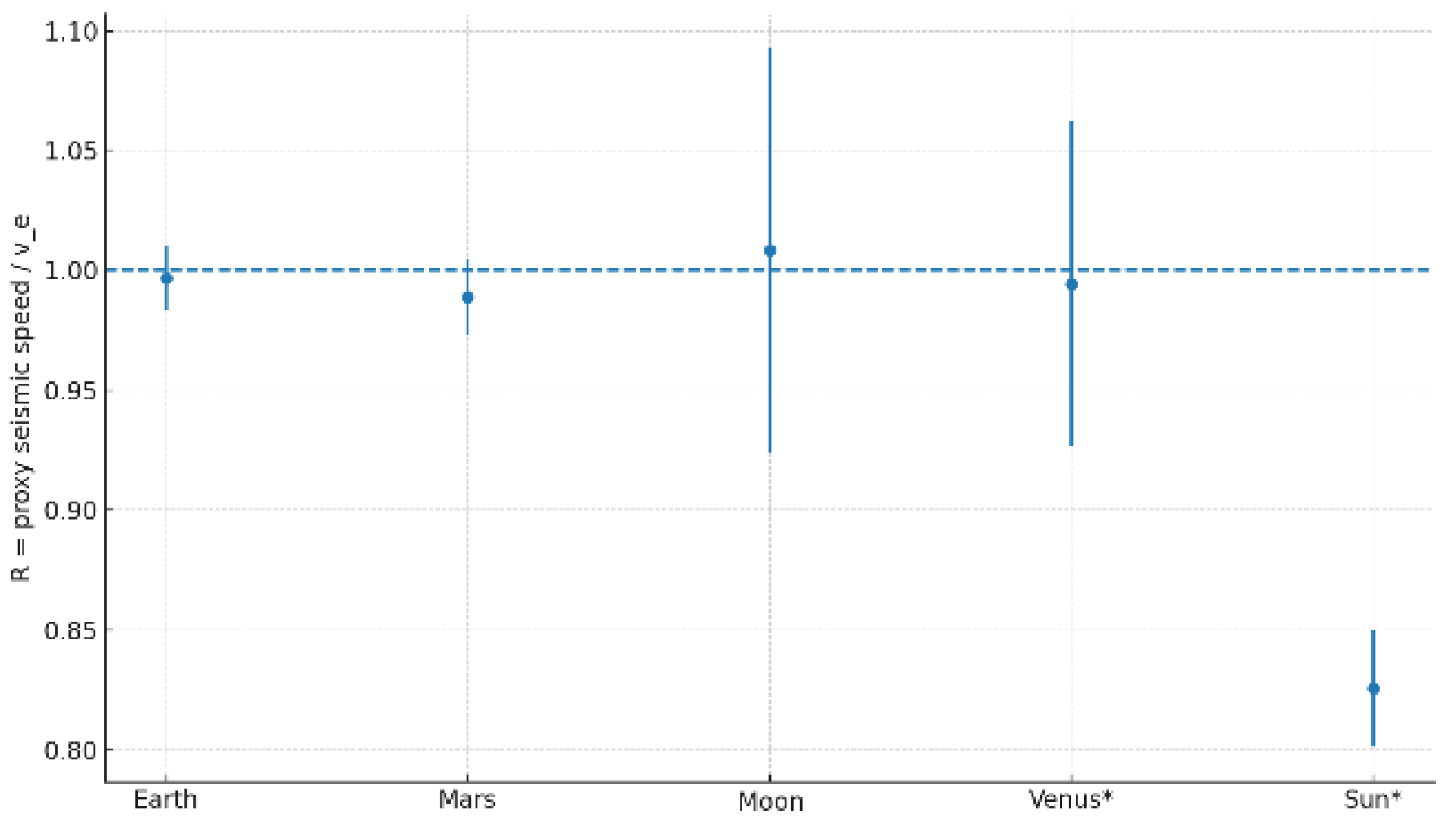

2.3. Seismic–Gravitational Velocity Convergence as Empirical Evidence for Relativistic Group Delay

2.3.1. Empirical Data Supporting the Law

2.3.2. Interpretation Within the DCM Framework

2.4. Cosmological Redshift as Expansion Delay

2.5. Redshift as Cumulative Gravitational Delay: A Minimal Derivation

- (i)

- a gravitational delay term determined by the mass distribution along the line of sight and

- (ii)

- a kinematic delay term accounting for the finite-speed support of expanding multi-body systems (see Section 2.7).

2.6. Interpreting from the Line-of-Sight Potential

2.7. Expansion of a Galactic Multi-Body System

2.7.1. Metric Ansatz and Lensing Check

2.7.2. Great Attractor and Laniakea: Curvature-Induced Apparent Flows

- (i)

- A predicted alignment of the reconstructed peculiar-velocity dipole with the gradient of inferred from the observed baryons plus kinematic support (flat-curve ,and

- (ii)

- a weak anisotropy in locally inferred H0 that follows lines of steepest (a curvature-induced Hubble dipole).

3. Potential Experimental Tests

3.1. Testing Spacetime Curvature

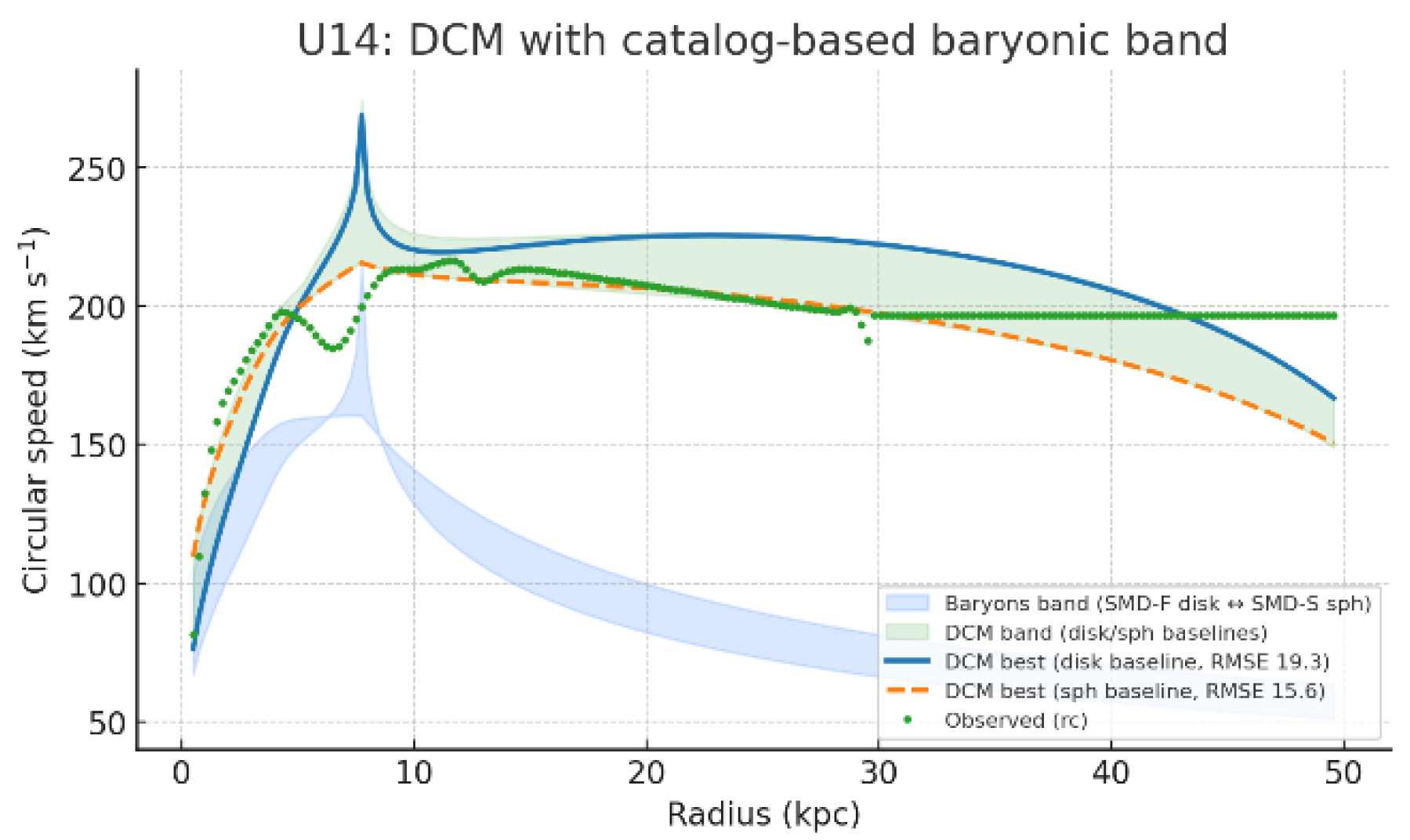

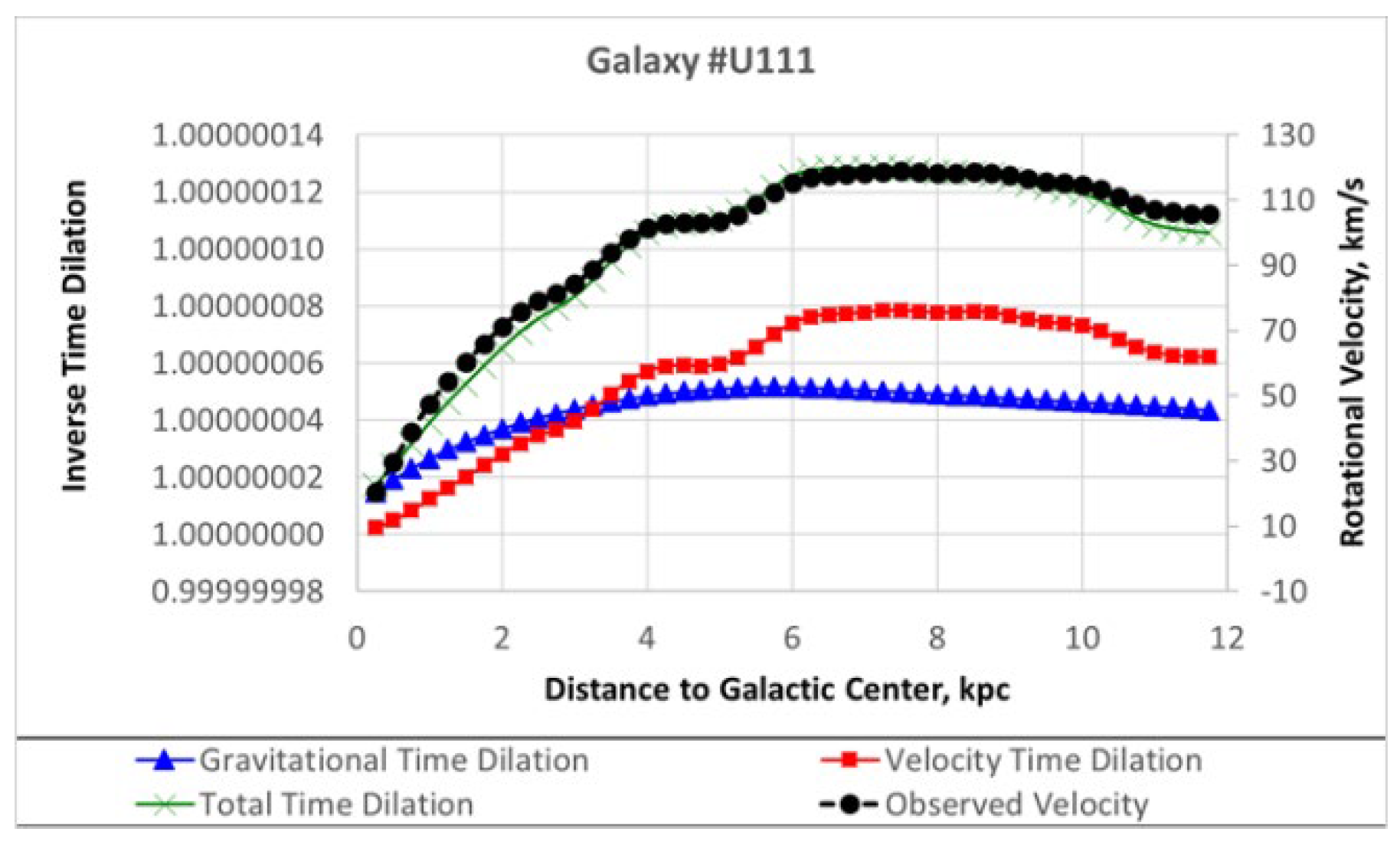

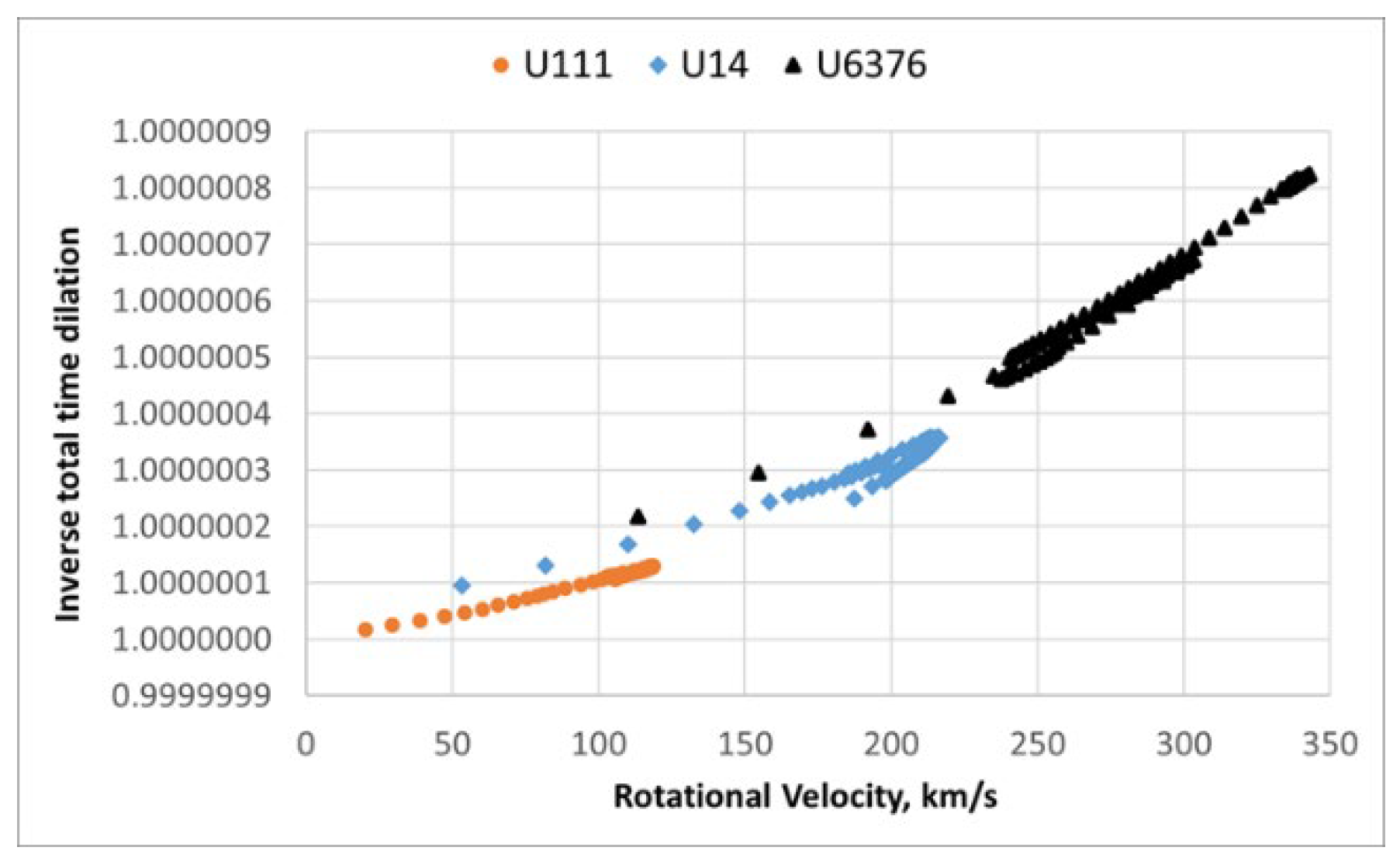

3.2. Testing Galactic Rotation

3.3. Testing Cosmological Redshift

4. Conclusions

- Seismic–gravitational law: a falsifiable diagnostic of gravity-shaped interiors, where seismic velocities converge with escape velocities.

- Flat galactic rotation curves: explained by the combined effect of gravitational and kinematic delays, without invoking dark matter.

- Quadratic suppression of redshift: near the cosmic horizon, offering a potential resolution to the Hubble tension.

Concluding Highlights

- Seismic–gravitational law: Average seismic velocities converge with escape velocities across self-gravitating bodies, revealing a new empirical regularity.

- Delay-based mechanism: Gravity and cosmological redshift arise from cumulative relativistic group delays in discretely expanding matter.

- Flat rotation curves: Galactic dynamics are explained by combined gravitational and kinematic delays, without invoking dark matter.

- Hubble tension: Quadratic redshift suppression near the cosmic horizon naturally accounts for the observed discrepancy in H0.

- Falsifiability: Predictions can be tested with Artemis lunar seismology, galaxy rotation spectroscopy, and local-group redshift surveys.

5. Future Work

- Test the seismic wave correlation for other bodies with gravity shaped cores.

- Future DCM tests may explore stellar bodies, predicting the Sun’s P-wave velocity (~510 km/s) aligns with its escape velocity (618 km/s, ratio ~0.82) via radial projection, testable with advanced helioseismology.

- Confirm Moon’s circular S-wave propagation with Artemis [7].

- Upscale Q-Drive at low temperatures [16].

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. GR-Compatible Stress-Energy Tensor for the Discrete Cosmology Model (DCM)

A.1. Two-Scale Link: Discrete to Continuum

A.2. Decomposition of the Source

A.3. Stationary, Axisymmetric Systems (Galaxies)

A.4. Cosmological Closure

A.5. Seismic Calibration

A.6. Comparison to Other Theories

A.7. Prediction Algorithm for Galactic Rotation Curves

- Baryonic baseline: Surface brightness profiles are converted to stellar surface densities using catalog . Two limiting cases are considered:

- Initial velocities: An initial is formed by combining baryonic components.

- Delay kernel: The two-scale delay operator (Appendix A.3) is applied to , yielding an effective delay acceleration field .

- Iteration: is updated iteratively until convergence of both vcv_cvc and the associated escape velocity vev_eve.

- Ensemble band: Parameters are scanned within order-unity ranges. Models within 10% of the best RMSE relative to observed are retained, defining a predictive band.

Appendix B. Observer-Local Factors and Horizon Relay Lemma

B.1. No-Local-Cap Lemma

B.2. Relay (Penetration) Clarification

References

- Sahni, V., Dark matter and dark energy: The mystery deepens, Nat. Phys. 2, 635–637, (2006),.

- Planck Collaboration, Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters.

- Richard Lieu, Are dark matter and dark energy omnipresent?, Class. Quantum Grav. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M., A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis, Astrophys. J. 270, 365–370 (1983),. [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D., Relativistic gravitation theory for the MOND paradigm.

- Oppenheim J, et al. A postquantum theory of classical gravity? Nature Communications 14, 43348 2023. [CrossRef]

- Garcia R.F, et al. Lunar seismology: A data and instrumentation review. Icarus 332, 66–78 2019.

- Irving J.C.E, et al. First observations of core-transiting seismic phases on Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120(18), e2217090120 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hartlep T, Mansour N.N. Acoustic wave propagation in the Sun. Center for Turbulence Research, Annual Research Briefs 2005.

- Riess, A. G. et al., The expansion of the Universe is faster than expected.

- Courteau S. The structure of spiral galaxies: I. Near-infrared properties of bulges and disks. ApJ Supplement Series 103, 363 1996. [CrossRef]

- Courteau S. Optical rotation curves and linewidths for Tully-Fisher applications. AJ 114, 2402 1997. [CrossRef]

- Sofue Y. Rotation curves of spiral galaxies. PASJ, 1–10 2014. [CrossRef]

- Sofue Y. Rotation curve of the Milky Way and the Galactic constants. PASJ, 1–10 2017. [CrossRef]

- Lynden-Bell, D. et al., Spectroscopy and photometry of elliptical galaxies. V. Galaxy streaming toward the new supergalactic center.

- Markov N. A quantum propulsion method. In: Proceedings of the International Maritime Association of the Mediterranean (IMAM2019), Varna, September 2019.

- Dziewonski, Adam M.; Anderson, Don L. 1981. “Preliminary reference Earth model”. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 25 (4): 297–356. Bibcode:1981PEPI...25..297D. ISSN 0031-9201. [CrossRef]

- Weber, Renee C.; Lin, Pei-Ying; Garnero, Edward J.; Williams, Quentin; Lognonné, Philippe (2011-01-21). “Seismic Detection of the Lunar Core”. Science. 331 (6015): 309–312. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..309W. ISSN 0036-8075. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, Yingcai; Nimmo, Francis; Lay, Thorne 2015. “Seismological implications of a lithospheric low seismic velocity zone in Mars”. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 240: 132–141. Bibcode:2015PEPI..240..132Z. ISSN 0031-9201. [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin T. et al. Tidal constraints on the interior of Venus. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 121, 1727–1743 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, F. “On the Red Shift of Spectral Lines,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 15 (1929).

- Lubin, L. M., & Sandage, A. “The Tolman Surface Brightness Test… IV,” AJ 122, 1084 (2001).

- Blondin, S. et al. “Time Dilation in Type Ia Supernova Spectra at High Redshift,” The Astrophysical Journal, Volume 682, Issue 2, pp. 724-736 (2008).

- Kocevski D.D., Ebeling H. 2006. On the origin of the Local Group’s peculiar velocity. Astrophys. J. 645, 1043–1053. [CrossRef]

- Lavaux G., Hudson M.J. 2011. The 2M++ galaxy redshift catalogue. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 416, 2840–2858. [CrossRef]

- Courtois H.M., Pomarède D., Tully R.B., Hoffman Y., Courtois D. 2013. Cosmography of the Local Universe. Astron. J. 146, 69. [CrossRef]

- Tully R.B., Courtois H., Hoffman Y., Pomarède D. 2014. The Laniakea supercluster of galaxies. Nature 513, 71–73. [CrossRef]

| Body |

km/s |

Wave |

km/s |

Ratio |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | 11.2 | P | 11.2 | 1.00 | [17] |

| Venus | 10.3 | P | 10.4 | 1.00 | [20] |

| Mars | 5.0 | P | 5.0 | 1.00 | [19] |

| Moon | 2.4 | S | 2.4 | 1.00 | [18] |

| Io | 2.2 | S | 2.4 | 0.92 | Estimated* |

| Asteroids | < 0.5 | P | < 0.1 | ≫ 1 (disordered) | Estimated* |

| Sun | 510 | P | 618 | 0.82 | [9] |

| Scale | Density vs. Mean | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| <10 Mpc | Overdense | 2MASS, SDSS |

| ~50 Mpc | Possibly overdense | Laniakea |

| 100–300 Mpc | Conflicting | Mixed claims |

| >300 Mpc | Cosmic mean | Planck CMB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).