Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Global Cancer Burden

1.2. Current Challenges in Cancer Treatment

1.3. Natural Products in Cancer Therapy

1.4. Historical Use of Venom in Medicine

1.5. The Promise of Scorpion Venom

2. Composition and Biochemistry of Scorpion Venom

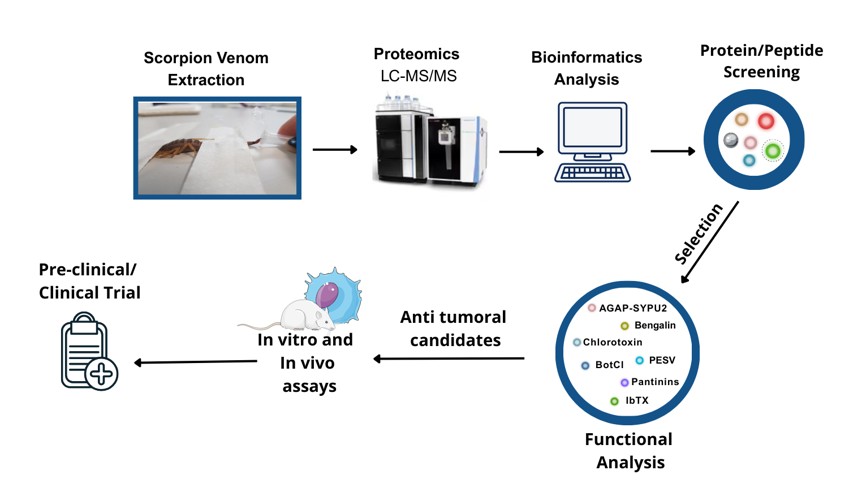

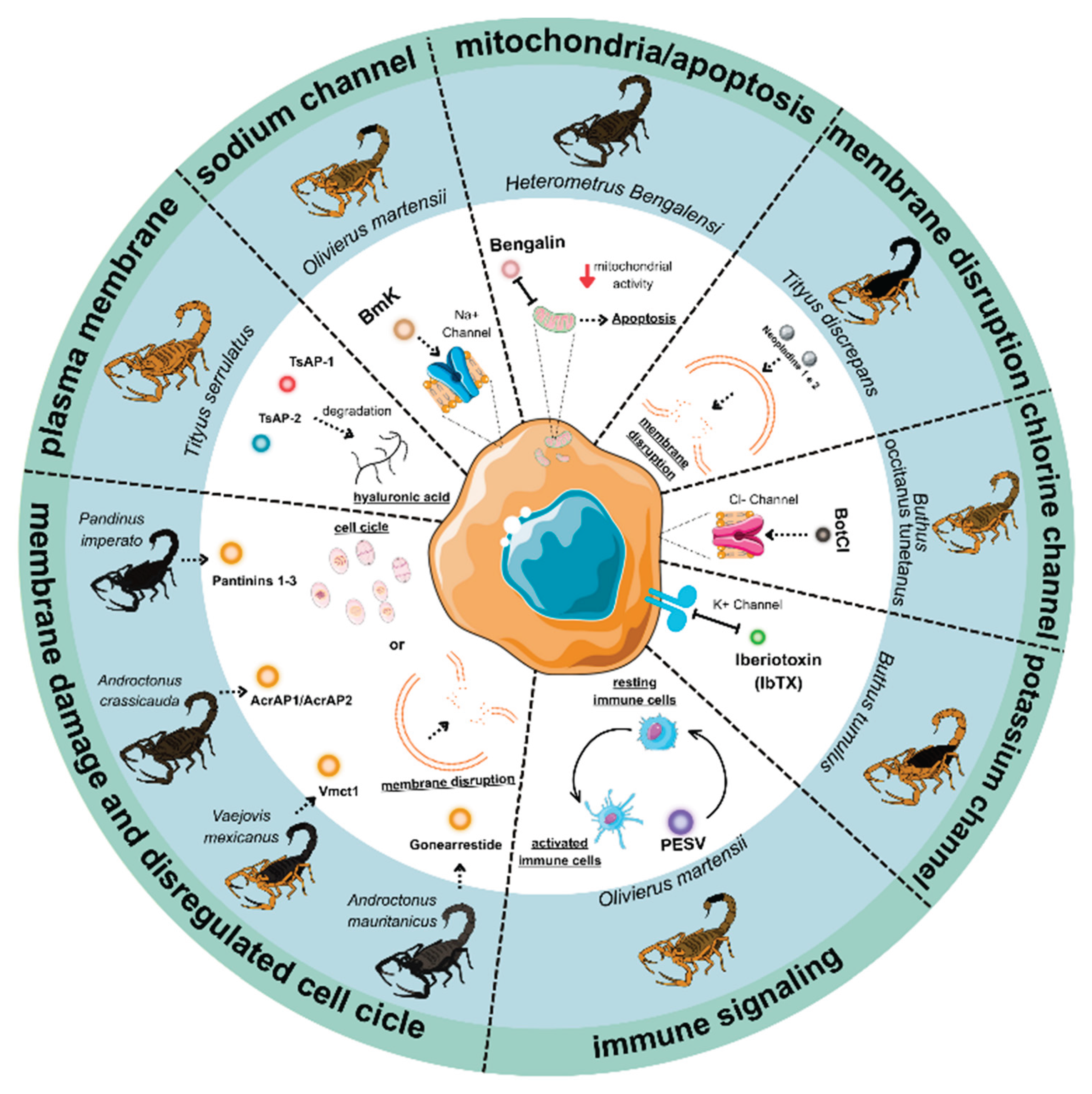

2.1. Proteomic Characterization of Scorpion Venom

2.2. Major Protein and Peptide Components of Scorpion Venom

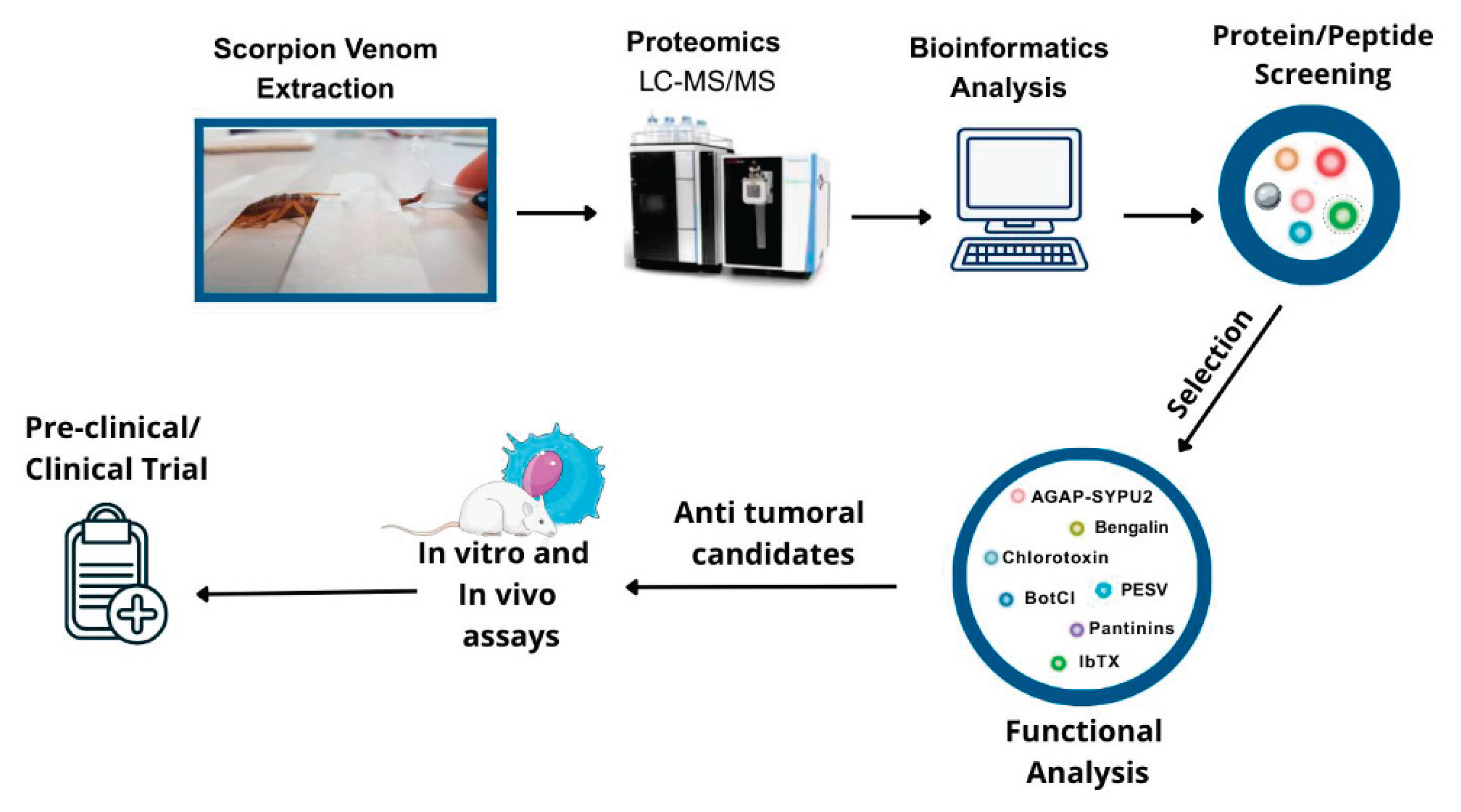

3. Molecular Mechanisms of Anticancer Activity

3.1. Induction of Apoptosis

3.2. Cellular Signaling and Cycle Disruption

4. Specific Anticancer Components in Scorpion Venom

4.1. Apoptosis induction

4.1.1. TsAP-1 and TsAP-2 from Tityus Serrulatus

4.1.2. Bengalin from Heterometrus Bengalensis and Other Novel Peptides

4.1.3. Neopladine 1 and Neopladine 2 from Tityus Discrepans

4.2. Ion Channel Modulation

4.2.1. AGAP-SYPU2 from Buthus Martensii Karsch

4.2.2. BotCl from Buthus Occitanus Tunetanus

4.2.3. Iberiotoxin (IbTX) from Hottentotta Tamulus

4.3. Cell Cycle Arrest

4.3.1. Gonearrestide from Androctonus Mauritanicus

4.3.2. PESV from Buthus Martensii Karsch

4.4. Membrane Disruption and Tumor Microenvironment

4.4.1. Hyaluronidase BmHYA1 from Buthus Martensii Karsch

4.4.2. RK1 from Buthus Occitanus Tunetanus

4.4.3. Vmct1 from Vaejovis Mexicanus

4.4.4. AcrAP1/AcrAP2 from Androctonus Crassicauda

4.4.5. Pantinins 1-3 from Pandinus Imperator

4.5. Multifunctional Peptides

4.5.1. Chlorotoxin from Leiurus Hebraeus and Derivatives

4.5.2. Maurocalcine from Scorpio Maurus Palmatus and Related Peptides

5. Cancer-Specific Targeting Mechanisms

5.1. Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

5.2. Molecular targeting Mechanisms

5.2.1. Ion Channel Interactions

5.2.2. Receptor-Mediated Effects

6. Immunomodulatory Effects

6.1. Innate Immune Response Modulation

6.2. Adaptive Immunity Enhancement

6.3. Cytokine Profile Alterations

6.4. Immune Cell Activation and Regulation

6.5. Potential for Immunotherapy Enhancement

7. Diagnostic Applications

7.1. Early Detection Methods

7.2. Biomarker Development

7.3. Therapeutic Monitoring

7.4. Integration with Current Diagnostic Tools

8. Drug Development and Delivery Systems

8.1. Peptide Modification Strategies

8.2. Nanoparticle-Based Delivery

8.3. Targeted Delivery Systems

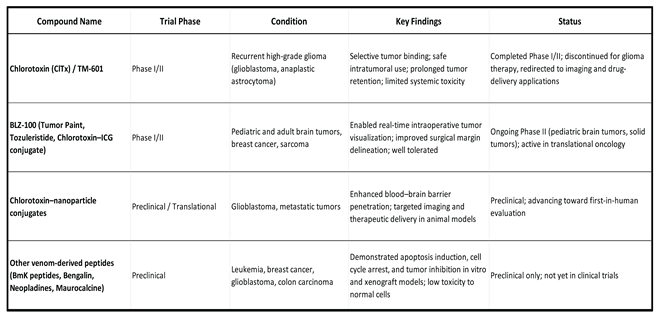

9. Clinical Studies and Trials

9.1. Preclinical Studies

9.2. Clinical Trials

9.2.1. TM-601 (131 I-chlorotoxin conjugate)

9.2.2. BLZ-100 (Tozuleristide, “Tumor Paint”)

10. Current Challenges and Future Directions

10.1. Production and Scale-up Issues

10.2. Regulatory Considerations

10.3. Cost and Accessibility

10.4. Research Gaps

10.5. Future Research Directions

11. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ΔΨm | Mitochondrial membrane potential. |

| A2780 | Human Ovarian Cancer Cell Line A2780. |

| Aah II | Aah II neurotoxin. |

| AaTs-1 | Androctonus australis Toxin-1. |

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette. |

| AcrAP1 | Androctonus crassicauda Antimicrobial Peptides 1. |

| AcrAP2 | Androctonus crassicauda Antimicrobial Peptides 2. |

| AGAP | Analgesic-Antitumor Peptide. |

| AGAP-SYPU2 | Analgesic-Antitumor Peptide Variant SYPU2. |

| AI | Artificial intelligence. |

| AK | Adenylate kinase. |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B. |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial Peptides. |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1. |

| Arg1 | Arginase-1. |

| ATMs | Tumor-Associated Macrophages. |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate. |

| AuNP-antibody | Gold nanoparticle conjugated to antibody. |

| B16-F10 | Murine Melanoma Cell Line B16-F10. |

| Bax | Bcl-2-Associated X Protein. |

| BBB | Blood-Brain Barrier. |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell Lymphoma 2. |

| BKCa | Large-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Channel. |

| BLZ-100 | Chlorotoxin-based Tumor Paint Bioconjugate. |

| BmHYA1 | Buthus martensii Karsch Hyaluronidase 1. |

| BmK | Buthus martensii Karsch. |

| BmKCT | Buthus martensii Karsch chlorotoxin. |

| BmKDfsin4 | Derived Defensin-4 peptide. |

| BmKn1 | Antimicrobial peptides derived from Buthus martensii Karsch venom. |

| BmKn2–7 | Anticancer peptides derived from Buthus martensii Karsch venom. |

| BotCl | Buthus occitanus tunetanus Chloride Channel Blocker. |

| BTB | Blood-tumor barrier. |

| Buthicyclin | Cyclic peptide derived from Defensin-4. |

| C3 | Complement component 3. |

| C6 | Glioma cell line. |

| Ca²⁺ | Calcium ion. |

| CAM | Chorioallantoic Membrane. |

| Caspase-3 | Effector caspase enzyme. |

| CD | Circular dichroism. |

| CD40L | CD40 ligand. |

| CD44 | Cluster of Differentiation 44. |

| CD44v6 | CD44 Variant Isoform 6. |

| CDK | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase. |

| CDK4 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4. |

| CDKI | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor. |

| CDKIs | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors. |

| CDKs | Cyclin-dependent kinases. |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA. |

| ChTX | Charybdotoxin. |

| CIF8 | Cancer Inhibitory Fractions 8. |

| CIF9 | Cancer Inhibitory Fractions 9. |

| ClC-3 | Chloride Channel Protein 3. |

| Cm28 | Centruroides margaritatus peptide/toxin. |

| CN | Chitosan nanoparticles. |

| CNS | Central nervous system. |

| CORT | Cortistatin. |

| Css54 | Cationic antimicrobial peptide 54. |

| CTX | Chlorotoxin. |

| D3 | Cyclin D3. |

| DISC | Death-inducing signaling complex. |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid. |

| DU145 | Human Prostate Carcinoma Cell Line DU145. |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix. |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases 1/2. |

| F3II | Murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell line F3II. |

| FasL | Apoptosis-inducing ligand binding to Fas receptor. |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration. |

| FoxO | Forkhead Box O. |

| FPRL-1 | Formyl Peptide Receptor-Like 1. |

| FTox-G50 | Scorpion venom fraction Toxin G50. |

| G0 | Cell cycle phases of resting. |

| G1 | Gap 1 phase of the Cell Cycle. |

| GK | Glucokinase. |

| H22 | Murine Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line H22. |

| H460 / NCI-H460 | Human Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Cell Line. |

| HA | Hyaluronic Acid. |

| HBsAg-specific | Hepatitis B surface antigen-specific. |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma. |

| HCT116 | Human Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Line HCT116. |

| HCT-8 | Colorectal cancer cell line. |

| HeLa | Human Cervical Cancer Cell Line HeLa. |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth receptor 2. |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. |

| HSP70 | Heat shock protein 70. |

| HSP90 | Heat shock protein 90. |

| HsTX1 | Heterometrus scaber toxin 1. |

| hTERTC27 | C-terminal 27 kDa polypeptide fragment of human telomerase reverse transcriptase. |

| HUVEC | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. |

| IbTX | Iberiotoxin. |

| IC₅₀ | Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration. |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma. |

| IGR39 | Human Melanoma Cell Line IGR39. |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10. |

| IL-12p40 | Interleukin-12 subunit p40. |

| IL-12p70 | Biologically active heterodimeric form of interleukin-12. |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta. |

| IL-23 | Interleukin-23. |

| IL-2R | Interleukin-2 receptor. |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4. |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6. |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8. |

| iTRAQ | Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification. |

| JAK | Janus kinase. |

| Kd | Equilibrium Dissociation Constant. |

| Kv1.1 | Voltage-gated Potassium Channel Subfamily A Member 1. |

| Kv1.3 | Voltage-gated Potassium Channel Subfamily A Member 3. |

| Kv10.1 | Voltage-gated potassium channel 10.1. |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. |

| LD50 | Median lethal dose. |

| LS174 | Human Colon Adenocarcinoma Cell Line LS174. |

| LSPR | Localized plasmon resonance. |

| M1 macrophages | Classically activated macrophages. |

| M2 macrophages | Alternatively activated macrophages. |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. |

| MAP kinases | Mitogen-activated protein kinases. |

| MAPK p38 | p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase. |

| MCa | Micaelase. |

| MCF-7 | Human Breast Cancer Cell Line MCF-7. |

| MDA-MB-231 | Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Line. |

| MDA-MB-435s | Human Breast Carcinoma Cell Line. |

| Meuk7–3 | Peptide fraction Meuk7–3. |

| MgTX | Margatoxin. |

| MiniCTX3 | Charybdotoxin analogue peptide. |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2. |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging. |

| MS | Mass spectrometry. |

| MS/MS | Tandem mass spectrometry. |

| MT1-MMP | Membrane-Type 1 Matrix Metalloproteinase. |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin. |

| MyD88 | Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response 88. |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate. |

| Nav1.4 | Voltage-gated Sodium Channel, Alpha Subunit 1.4. |

| Nav1.5 | Voltage-gated Sodium Channel, Alpha Subunit 1.5. |

| Nav1.7 | Voltage-gated Sodium Channel, Alpha Subunit 1.7. |

| Nav1.8 | Voltage-gated Sodium Channel, Alpha Subunit 1.8. |

| NCI-H460 | Human Lung Cancer Cell Line NCI-H460. |

| NDBP | Non-Disulfide Bridged Peptide. |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer. |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor. |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing. |

| NOS2 | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase. |

| NRP1 | Neuropilin-1. |

| OGFR | Opioid growth factor receptor. |

| FOXO3a | Forkhead box O3a. |

| p21 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A. |

| p27 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B. |

| p53 | Tumor suppressor protein. |

| PAMAM | Polyamidoamine. |

| PARP | Poly polymerase. |

| PC-3 | Human Prostate Carcinoma Cell Line PC-3. |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol. |

| PEG-CTX | Polyethylene glycol–chlorotoxin conjugate. |

| PEGylation | Polyethylene glycol conjugation. |

| PESV | Polypeptide Extract from Scorpion Venom. |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase. |

| PLA-PEG | Polylactic acid–polyethylene glycol copolymer. |

| PLA2 | Phospholipase A2. |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor. |

| PTEN | Fosfatase supressora tumoral. |

| PTMs | Post-translational modifications. |

| RAW264.7 | Macrophage-like cell line. |

| RK1 | Scorpion-derived Peptide from Buthus occitanus tunetanus. |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species. |

| S1 / S2 | Designations of Stigmurin analogues. |

| S180 | Murine Sarcoma Cell Line S180. |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis. |

| SEC | Size exclusion chromatography. |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy. |

| SHG-44 | Human Glioma Cell Line SHG-44. |

| SPECT | Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography. |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance. |

| STAT3 | Transcription factor. |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription. |

| SVS-1 | Anticancer Beta-Hairpin Peptide SVS-1. |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages. |

| tBid | Truncated Bid. |

| TfR | Transferrin receptor. |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta. |

| Th1 / Th2 / Th17 cells | T helper cell subsets. |

| TIMPs | Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases. |

| TLR2 | Toll-Like Receptors 2. |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptors 4. |

| TM-601 | Synthetic Chlorotoxin Derivative Radiolabeled with Iodine-131. |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment. |

| TMT | Tandem mass tags. |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha. |

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. |

| TRPV1+ | Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1–positive. |

| Ts1 | Major neurotoxin from Tityus serrulatus venom. |

| Tsv | Tityus stigmurus venom. |

| TzII | Tityus zulianus toxin isoforms II. |

| TzIII | Tityus zulianus toxin isoforms III. |

| U87 | Human Glioblastoma Cell Line U87. |

| UHPLC-QTOF-MS | Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. |

| VERO | African Green Monkey Kidney Epithelial Cell Line VERO. |

| Vm24 | Peptide from Vaejovis mexicanus. |

| Vmct1 | Vaejovis mexicanus cationic peptide 1. |

| Vmct1-K | Lysine-substituted variant of Vmct1. |

| VRE | Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus. |

| α1β1 | Alpha-1 Beta-1 Integrin. |

| αvβ3 | Alpha-V Beta-3 Integrin. |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46. [CrossRef]

- Mariotto, A.B.; Enewold, L.; Zhao, J.; Zeruto, C.A.; Yabroff, K.R. Medical Care Costs Associated with Cancer Survivorship in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2020, 29, 1304–1312. [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.T.; Chidharla, A.; Kasi, A. Cancer Chemotherapy; 2025;

- Nikolaou, M.; Pavlopoulou, A.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Kyrodimos, E. The Challenge of Drug Resistance in Cancer Treatment: A Current Overview. Clin Exp Metastasis 2018, 35, 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Haider, T.; Pandey, V.; Banjare, N.; Gupta, P.N.; Soni, V. Drug Resistance in Cancer: Mechanisms and Tackling Strategies. Pharmacological Reports 2020, 72, 1125–1151. [CrossRef]

- Emran, T. Bin; Shahriar, A.; Mahmud, A.R.; Rahman, T.; Abir, M.H.; Siddiquee, Mohd.F.-R.; Ahmed, H.; Rahman, N.; Nainu, F.; Wahyudin, E.; et al. Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms, Immunoprevention and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Ferraro, G.B.; Jain, R.K. The Blood–Brain Barrier and Blood–Tumour Barrier in Brain Tumours and Metastases. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 26–41. [CrossRef]

- Bérard, C.; Truillet, C.; Larrat, B.; Dhermain, F.; Estève, M.-A.; Correard, F.; Novell, A. Anticancer Drug Delivery by Focused Ultrasound-Mediated Blood-Brain/Tumor Barrier Disruption for Glioma Therapy: From Benchside to Bedside. Pharmacol Ther 2023, 250, 108518. [CrossRef]

- Kato, R.; Zhang, L.; Kinatukara, N.; Huang, R.; Asthana, A.; Weber, C.; Xia, M.; Xu, X.; Shah, P. Investigating Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration and Neurotoxicity of Natural Products for Central Nervous System Drug Development. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 7431. [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Dong, X. Current Status of In Vitro Models of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Curr Drug Deliv 2022, 19, 1034–1046. [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod 2020, 83, 770–803. [CrossRef]

- Bordon, K. de C.F.; Cologna, C.T.; Fornari-Baldo, E.C.; Pinheiro-Júnior, E.L.; Cerni, F.A.; Amorim, F.G.; Anjolette, F.A.P.; Cordeiro, F.A.; Wiezel, G.A.; Cardoso, I.A.; et al. From Animal Poisons and Venoms to Medicines: Achievements, Challenges and Perspectives in Drug Discovery. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Abd El-Aziz, T.; Soares, A.G.; Stockand, J.D. Snake Venoms in Drug Discovery: Valuable Therapeutic Tools for Life Saving. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 564. [CrossRef]

- Freuville, L.; Matthys, C.; Quinton, L.; Gillet, J.-P. Venom-Derived Peptides for Breaking through the Glass Ceiling of Drug Development. Front Chem 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Fekri, H.S.; Hashemi, F.; Hushmandi, K.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Garg, M. Venom Peptides in Cancer Therapy: An Updated Review on Cellular and Molecular Aspects. Pharmacol Res 2021, 164, 105327. [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, J.R.; Hasaballah, N.; Vetter, I. Pharmacological Screening Technologies for Venom Peptide Discovery. Neuropharmacology 2017, 127, 4–19. [CrossRef]

- King, G.F. Venoms as a Platform for Human Drugs: Translating Toxins into Therapeutics. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2011, 11, 1469–1484. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J.; Garcia, M.L. Therapeutic Potential of Venom Peptides. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003, 2, 790–802. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.H. A Bradykinin-Potentiating Factor (Bpf) Present in Venom of Bothrops Jararaca. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 1965, 24, 163-.

- Camargo, A.C.M.; Ianzer, D.; Guerreiro, J.R.; Serrano, S.M.T. Bradykinin-Potentiating Peptides: Beyond Captopril. Toxicon 2012, 59, 516–523. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.R.; Scarborough, R.M. Clinical Pharmacology of Eptifibatide. American Journal of Cardiology 1997, 80, B11–B20. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.; Cruz, L.J.; Hunkapiller, M.W.; Gray, W.R.; Olivera, B.M. Isolation and Structure of a Peptide Toxin from the Marine Snail Conus Magus. Arch Biochem Biophys 1982, 218, 329–334. [CrossRef]

- Eng, J.; Kleinman, W.A.; Singh, L.; Singh, G.; Raufman, J.P. Isolation and Characterization of Exendin-4, an Exendin-3 Analogue, from Heloderma Suspectum Venom. Further Evidence for an Exendin Receptor on Dispersed Acini from Guinea Pig Pancreas. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1992, 267, 7402–7405.

- Ahmadi, S.; Knerr, J.M.; Argemi, L.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Pucca, M.B.; Cerni, F.A.; Arantes, E.C.; Çalışkan, F.; Laustsen, A.H. Scorpion Venom: Detriments and Benefits. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 118. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, E.; Gurrola, G.B.; Schwartz, E.F.; Possani, L.D. Scorpion Venom Components as Potential Candidates for Drug Development. Toxicon 2015, 93, 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.; Ullah, Z.; Al Balowi, A.; Islam, M. In Vitro Determination of the Efficacy of Scorpion Venoms as Anti-Cancer Agents against Colorectal Cancer Cells: A Nano-Liposomal Delivery Approach. Int J Nanomedicine 2017, Volume 12, 559–574. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Dominguez, P.A.; Corzo, G. Characterization of the Coupling Mechanism of Scorpion β-Neurotoxins on the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel HNav1.6. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2023, 41, 14419–14427. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Quintero-Hernández, V.; Possani, L.D. Scorpion Venom Gland Transcriptomics and Proteomics: An Overview. In Venom Genomics and Proteomics; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2014; pp. 1–17.

- Marchi, F.C.; Mendes-Silva, E.; Rodrigues-Ribeiro, L.; Bolais-Ramos, L.G.; Verano-Braga, T. Toxinology in the Proteomics Era: A Review on Arachnid Venom Proteomics. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2022, 28. [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmari, A.K.; Riyasdeen, A.; Islam, M. Scorpion Venom Causes Upregulation of P53 and Downregulation of Bcl-x L and BID Protein Expression by Modulating Signaling Proteins Erk 1/2 and STAT3, and DNA Damage in Breast and Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. Integr Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 271–281. [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Hou, X.; Ge, L.; Li, R.; Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Wei, M.; Chen, T.; Shaw, C. Cationicity-Enhanced Analogues of the Antimicrobial Peptides, AcrAP1 and AcrAP2, from the Venom of the Scorpion, Androctonus crassicauda, Display Potent Growth Modulation Effects on Human Cancer Cell Lines. Int J Biol Sci 2014, 10, 1097–1107. [CrossRef]

- Pedron, C.N.; de Oliveira, C.S.; da Silva, A.F.; Andrade, G.P.; da Silva Pinhal, M.A.; Cerchiaro, G.; da Silva Junior, P.I.; da Silva, F.D.; Torres, M.D.T.; Oliveira, V.X. The Effect of Lysine Substitutions in the Biological Activities of the Scorpion Venom Peptide VmCT1. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2019, 136, 104952. [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.A.; Kampo, S.; Sackey, M.; Hechavarria, M.E.; Buunaaim, A.D.B. The Pivotal Potentials of Scorpion Buthus Martensii Karsch- Analgesic-Antitumor Peptide in Pain Management and Cancer. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.-H.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, M.-Y.; Wu, C.-F.; Liu, Y.-F.; Zhang, J.-H. Purification, Characterization, and Bioactivity of a New Analgesic-Antitumor Peptide from Chinese Scorpion Buthus Martensii Karsch. Peptides (N.Y.) 2014, 53, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cai, X.; Ye, T.; Huo, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Cao, P. Analgesic-Antitumor Peptide Inhibits Proliferation and Migration of SHG-44 Human Malignant Glioma Cells. J Cell Biochem 2011, 112, 2424–2434. [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, S.; Halder, B.; Gomes, A.; Gomes, A. Bengalin Initiates Autophagic Cell Death through ERK–MAPK Pathway Following Suppression of Apoptosis in Human Leukemic U937 Cells. Life Sci 2013, 93, 271–276. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. Das; Gomes, A.; Debnath, A.; Saha, A.; Gomes, A. Apoptosis Induction in Human Leukemic Cells by a Novel Protein Bengalin, Isolated from Indian Black Scorpion Venom: Through Mitochondrial Pathway and Inhibition of Heat Shock Proteins. Chem Biol Interact 2010, 183, 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Mahadevappa, R.; Kwok, H.F. Venom-Based Peptide Therapy: Insights into Anti-Cancer Mechanism. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 100908–100930. [CrossRef]

- Baradaran, M.; Pashmforoosh, N. Peptides with Diverse Functions from Scorpion Venom: A Great Opportunity for the Treatment of a Wide Variety of Diseases. The Payam-e-Marefat-Kabul Education University 2023, 27, 84–99. [CrossRef]

- Sarfo-Poku, C.; Eshun, O.; Lee, K.H. Medical Application of Scorpion Venom to Breast Cancer: A Mini-Review. Toxicon 2016, 122, 109–112. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.-D.; Yu, X.-N.; Wang, R.; Chen, X.-L. Upregulation of PTEN Involved in Scorpion Venom-Induced Apoptosis in a Lymphoma Cell Line. Leuk Lymphoma 2009, 50, 633–641. [CrossRef]

- Rapôso, C. Scorpion and Spider Venoms in Cancer Treatment: State of the Art, Challenges, and Perspectives. J Clin Transl Res 2017, 3, 233–249.

- Panja, K.; Buranapraditkun, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Kovitvadhi, A.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Nakagawa, T.; Limmanont, C.; Jaroensong, T. Scorpion Venom Peptide Effects on Inhibiting Proliferation and Inducing Apoptosis in Canine Mammary Gland Tumor Cell Lines. Animals 2021, 11, 2119. [CrossRef]

- Satitmanwiwat, S.; Changsangfa, C.; Khanuengthong, A.; Promthep, K.; Roytrakul, S.; Arpornsuwan, T.; Saikhun, K.; Sritanaudomchai, H. The Scorpion Venom Peptide BmKn2 Induces Apoptosis in Cancerous but Not in Normal Human Oral Cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2016, 84, 1042–1050. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Qiao, W.; Chen, K. Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment of Gliomas Using Chlorotoxin-Based Bioconjugates. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014, 4, 385–405.

- Jlassi, A.; Mekni-Toujani, M.; Ferchichi, A.; Gharsallah, C.; Malosse, C.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; ElAyeb, M.; Ghram, A.; Srairi-Abid, N.; Daoud, S. BotCl, the First Chlorotoxin-Like Peptide Inhibiting Newcastle Disease Virus: The Emergence of a New Scorpion Venom AMPs Family. Molecules 2023, 28, 4355. [CrossRef]

- Dardevet, L.; Rani, D.; Aziz, T.A. El; Bazin, I.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Fadl, M.; Brambilla, E.; De Waard, M. Chlorotoxin: A Helpful Natural Scorpion Peptide to Diagnose Glioma and Fight Tumor Invasion. Toxins (Basel) 2015, 7, 1079–1101. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Inbar, O.; Zaaroor, M. Glioblastoma Multiforme Targeted Therapy: The Chlorotoxin Story. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2016, 33, 52–58. [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.U.; Carcamo-Noriega, E.; Beltrán-Vidal, J.; Borrego, J.; Szanto, T.G.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Delgado-Prudencio, G.; Possani, L.D.; Panyi, G. Cm28, a Scorpion Toxin Having a Unique Primary Structure, Inhibits KV1.2 and KV1.3 with High Affinity. Journal of General Physiology 2022, 154. [CrossRef]

- Ghezellou, P.; Jakob, K.; Atashi, J.; Ghassempour, A.; Spengler, B. Mass-Spectrometry-Based Lipidome and Proteome Profiling of Hottentotta saulcyi (Scorpiones: Buthidae) Venom. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 370. [CrossRef]

- Nosouhian, M.; Rastegari, A.A.; Shahanipour, K.; Ahadi, A.M.; Sajjadieh, M.S. Anticancer Potentiality of Hottentotta saulcyi Scorpion Curd Venom against Breast Cancer: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 24607. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lyu, P.; Xi, X.; Ge, L.; Mahadevappa, R.; Shaw, C.; Kwok, H.F. Triggering of Cancer Cell Cycle Arrest by a Novel Scorpion Venom-derived Peptide—Gonearrestide. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 4460–4473. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Najafi, R.; Amini, R.; Solgi, R.; Tanzadehpanah, H.; Esfahani, A.M.; Saidijam, M. Remarkable Apoptotic Pathway of Hemiscorpius lepturus Scorpion Venom on CT26 Cell Line. Cell Biol Toxicol 2019, 35, 373–385. [CrossRef]

- LEBRUN, B.; ROMI-LEBRUN, R.; MARTIN-EAUCLAIRE, M.-F.; YASUDA, A.; ISHIGURO, M.; OYAMA, Y.; PONGS, O.; NAKAJIMA, T. A Four-Disulphide-Bridged Toxin, with High Affinity towards Voltage-Gated K+ Channels, Isolated from Heterometrus spinnifer (Scorpionidae) Venom. Biochemical Journal 1997, 328, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Candia, S.; Garcia, M.L.; Latorre, R. Mode of Action of Iberiotoxin, a Potent Blocker of the Large Conductance Ca(2+)-Activated K+ Channel. Biophys J 1992, 63, 583–590. [CrossRef]

- Roger, S.; Potier, M.; Vandier, C.; Le Guennec, J.-Y.; Besson, P. Description and Role in Proliferation of Iberiotoxin-Sensitive Currents in Different Human Mammary Epithelial Normal and Cancerous Cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004, 1667, 190–199. [CrossRef]

- Aissaoui, D.; Mlayah-Bellalouna, S.; Jebali, J.; Abdelkafi-Koubaa, Z.; Souid, S.; Moslah, W.; Othman, H.; Luis, J.; ElAyeb, M.; Marrakchi, N.; et al. Functional Role of Kv1.1 and Kv1.3 Channels in the Neoplastic Progression Steps of Three Cancer Cell Lines, Elucidated by Scorpion Peptides. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 111, 1146–1155. [CrossRef]

- Koschak, A.; Koch, R.O.; Liu, J.; Kaczorowski, G.J.; Reinhart, P.H.; Garcia, M.L.; Knaus, H.-G. [ 125 I]Iberiotoxin-D19Y/Y36F, the First Selective, High Specific Activity Radioligand for High-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 1943–1952. [CrossRef]

- Nardi, A.; Calderone, V.; Chericoni, S.; Morelli, I. Natural Modulators of Large-Conductance Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels. Planta Med 2003, 69, 885–892. [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Ryu, P.D.; Lee, S.Y. Anti-Proliferative Effect of Kv1.3 Blockers in A549 Human Lung Adenocarcinoma in Vitro and in Vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 2011, 651, 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Boisseau, S.; Mabrouk, K.; Ram, N.; Garmy, N.; Collin, V.; Tadmouri, A.; Mikati, M.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Ronjat, M.; Fantini, J.; et al. Cell Penetration Properties of Maurocalcine, a Natural Venom Peptide Active on the Intracellular Ryanodine Receptor. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2006, 1758, 308–319. [CrossRef]

- Aroui, S.; Ram, N.; Appaix, F.; Ronjat, M.; Kenani, A.; Pirollet, F.; De Waard, M. Maurocalcine as a Non Toxic Drug Carrier Overcomes Doxorubicin Resistance in the Cancer Cell Line MDA-MB 231. Pharm Res 2009, 26, 836–845. [CrossRef]

- Aroui, S.; Dardevet, L.; Najlaoui, F.; Kammoun, M.; Laajimi, A.; Fetoui, H.; De Waard, M.; Kenani, A. PTEN-Regulated AKT/FoxO3a/Bim Signaling Contributes to Human Cell Glioblastoma Apoptosis by Platinum-Maurocalcin Conjugate. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2016, 77, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Ram, N.; Aroui, S.; Jaumain, E.; Bichraoui, H.; Mabrouk, K.; Ronjat, M.; Lortat-Jacob, H.; De Waard, M. Direct Peptide Interaction with Surface Glycosaminoglycans Contributes to the Cell Penetration of Maurocalcine. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 24274–24284. [CrossRef]

- D’Suze, G.; Rosales, A.; Salazar, V.; Sevcik, C. Apoptogenic Peptides from Tityus discrepans Scorpion Venom Acting against the SKBR3 Breast Cancer Cell Line. Toxicon 2010, 56, 1497–1505. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-C.; Zhou, L.; Shi, W.; Luo, X.; Zhang, L.; Nie, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Cao, B.; Cao, H. Three New Antimicrobial Peptides from the Scorpion Pandinus Imperator. Peptides (N.Y.) 2013, 45, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Crusca, E.; Basso, L.G.M.; Altei, W.F.; Marchetto, R. Biophysical Characterization and Antitumor Activity of Synthetic Pantinin Peptides from Scorpion’s Venom. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2018, 1860, 2155–2165. [CrossRef]

- Elrayess, R.A.; Mohallal, M.E.; Mobarak, Y.M.; Ebaid, H.M.; Haywood-Small, S.; Miller, K.; Strong, P.N.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A. Scorpion Venom Antimicrobial Peptides Induce Caspase-1 Dependant Pyroptotic Cell Death. Front Pharmacol 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Han, D.; Zhang, K.; Gai, C.; Chai, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zou, Y.; Yin, L. Optimization of Antimicrobial Peptide Smp43 as Novel Inhibitors of Cancer. Bioorg Chem 2025, 161, 108561. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Gao, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Chai, J.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Xu, X.; Chen, X. The Potent Antitumor Activity of Smp43 against Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer A549 Cells via Inducing Membranolysis and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Toxins (Basel) 2023, 15, 347. [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Yang, W.; Gao, Y.; Guo, R.; Peng, Q.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Xu, X. Antitumor Effects of Scorpion Peptide Smp43 through Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Membrane Disruption on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Nat Prod 2021, 84, 3147–3160. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Guo, R.; Chai, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Xia, H.; Xu, X. Smp24, a Scorpion-Venom Peptide, Exhibits Potent Antitumor Effects against Hepatoma HepG2 Cells via Multi-Mechanisms In Vivo and In Vitro. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 717. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Liu, J.; Chai, J.; Gao, Y.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Xu, X. Scorpion Peptide Smp24 Exhibits a Potent Antitumor Effect on Human Lung Cancer Cells by Damaging the Membrane and Cytoskeleton In Vivo and In Vitro. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 438. [CrossRef]

- Rates, B.; Ferraz, K.K.F.; Borges, M.H.; Richardson, M.; De Lima, M.E.; Pimenta, A.M.C. Tityus serrulatus Venom Peptidomics: Assessing Venom Peptide Diversity. Toxicon 2008, 52, 611–618. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ma, C.; Du, Q.; Wei, R.; Wang, L.; Zhou, M.; Chen, T.; Shaw, C. Two Peptides, TsAP-1 and TsAP-2, from the Venom of the Brazilian Yellow Scorpion, Tityus serrulatus: Evaluation of Their Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1784–1794. [CrossRef]

- Daniele-Silva, A.; Machado, R.J.A.; Monteiro, N.K. V; Estrela, A.B.; Santos, E.C.G.; Carvalho, E.; Araújo Júnior, R.F.; Melo-Silveira, R.F.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Silva-Júnior, A.A.; et al. Stigmurin and TsAP-2 from Tityus stigmurus Scorpion Venom: Assessment of Structure and Therapeutic Potential in Experimental Sepsis. Toxicon 2016, 121, 10–21. [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Gurrola-Briones, G.; Papp, F.; Rodríguez de la Vega, R.C.; Pedraza-Alva, G.; Tajhya, R.B.; Gaspar, R.; Cardenas, L.; Rosenstein, Y.; Beeton, C.; et al. Vm24, a Natural Immunosuppressive Peptide, Potently and Selectively Blocks Kv1.3 Potassium Channels of Human T Cells. Mol Pharmacol 2012, 82, 372–382. [CrossRef]

- Cid-Uribe, J.I.; Veytia-Bucheli, J.I.; Romero-Gutierrez, T.; Ortiz, E.; Possani, L.D. Scorpion Venomics: A 2019 Overview. Expert Rev Proteomics 2020, 17, 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez-López, C.; Cid-Uribe, J.; Batista, C.; Ortiz, E.; Possani, L. Venom Gland Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses of the Enigmatic Scorpion Superstitionia donensis (Scorpiones: Superstitioniidae), with Insights on the Evolution of Its Venom Components. Toxins (Basel) 2016, 8, 367. [CrossRef]

- So, W.L.; Leung, T.C.N.; Nong, W.; Bendena, W.G.; Ngai, S.M.; Hui, J.H.L. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses of Venom Glands from Scorpions Liocheles australasiae, Mesobuthus martensii, and Scorpio Maurus palmatus. Peptides (N.Y.) 2021, 146, 170643. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Prudencio, G.; Cid-Uribe, J.I.; Morales, J.A.; Possani, L.D.; Ortiz, E.; Romero-Gutiérrez, T. The Enzymatic Core of Scorpion Venoms. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 248. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-C.; Luo, F.; Li, W.-X. Molecular Dissection of Venom from Chinese Scorpion Mesobuthus Martensii: Identification and Characterization of Four Novel Disulfide-Bridged Venom Peptides. Peptides (N.Y.) 2006, 27, 1745–1754. [CrossRef]

- Verano-Braga, T.; Dutra, A.A.A.; León, I.R.; Melo-Braga, M.N.; Roepstorff, P.; Pimenta, A.M.C.; Kjeldsen, F. Moving Pieces in a Venomic Puzzle: Unveiling Post-Translationally Modified Toxins from Tityus serrulatus. J Proteome Res 2013, 12, 3460–3470. [CrossRef]

- Melo-Braga, M.N. de; Moreira, R. da S.; Gervásio, J.H.D.B.; Felicori, L.F. Overview of Protein Posttranslational Modifications in Arthropoda Venoms. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2022, 28. [CrossRef]

- Romey, G.; Chicheportiche, R.; Lazdunski, M.; Rochat, H.; Miranda, F.; Lissitzky, S. Scorpion Neurotoxin — A Presynaptic Toxin Which Affects Both Na+ and K+ Channels in Axons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1975, 64, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Romey, G.; Abita, J.P.; Chicheportiche, R.; Rochat, H.; Lazdunski, M. Scorpion Neurotoxin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1976, 448, 607–619. [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. Neurotoxins That Act on Voltage-Sensitive Sodium Channels in Excitable Membranes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1980, 20, 15–43. [CrossRef]

- Gurevitz, M.; Froy, O.; Zilberberg, N.; Turkov, M.; Strugatsky, D.; Gershburg, E.; Lee, D.; Adams, M.E.; Tugarinov, V.; Anglister, J.; et al. Sodium Channel Modifiers from Scorpion Venom: Structure–Activity Relationship, Mode of Action and Application. Toxicon 1998, 36, 1671–1682. [CrossRef]

- Cestèle, S.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; Qu, Y.; Sampieri, F.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Structure and Function of the Voltage Sensor of Sodium Channels Probed by a β-Scorpion Toxin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 21332–21344. [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A.; Cestèle, S.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; Yu, F.H.; Konoki, K.; Scheuer, T. Voltage-Gated Ion Channels and Gating Modifier Toxins. Toxicon 2007, 49, 124–141. [CrossRef]

- Kozminsky-Atias, A.; Somech, E.; Zilberberg, N. Isolation of the First Toxin from the Scorpion Buthus Occitanus Israelis Showing Preference for Shaker Potassium Channels. FEBS Lett 2007, 581, 2478–2484. [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Hernández, V.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Gurrola, G.B.; Valdivia, H.H.; Possani, L.D. Scorpion Venom Components That Affect Ion-Channels Function. Toxicon 2013, 76, 328–342. [CrossRef]

- Housley, D.M.; Housley, G.D.; Liddell, M.J.; Jennings, E.A. Scorpion Toxin Peptide Action at the Ion Channel Subunit Level. Neuropharmacology 2017, 127, 46–78. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, F.; Yu, B.; Cao, Z. Activation of Sodium Channel by a Novel α-Scorpion Toxin, BmK NT2, Stimulates ERK1/2 and CERB Phosphorylation through a Ca2+ Dependent Pathway in Neocortical Neurons. Int J Biol Macromol 2017, 104, 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Beraldo Neto, E.; Freitas, L.A. de; Pimenta, D.C.; Lebrun, I.; Nencioni, A.L.A. Tb1, a Neurotoxin from Tityus bahiensis Scorpion Venom, Induces Epileptic Seizures by Increasing Glutamate Release. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12, 65. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, A.; Varela, D. Voltage-Gated K+/Na+ Channels and Scorpion Venom Toxins in Cancer. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Wiezel, G.A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Reis, M.B.; Ferreira, I.G.; Cordeiro, K.R.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Arantes, E.C. The Complex Repertoire of Tityus Spp. Venoms: Advances on Their Composition and Pharmacological Potential of Their Toxins. Biochimie 2024, 220, 144–166. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Alam, M.; Abbasi, A.; Undheim, E.; Fry, B.; Kalbacher, H.; Voelter, W. Structure-Activity Relationship of Chlorotoxin-Like Peptides. Toxins (Basel) 2016, 8, 36. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Dietel, B.; Wu, Y.; Beckmann, M.W.; Wrosch, J.K.; Buchfelder, M.; Eyupoglu, I.Y.; Cao, Z.; et al. Identification of Two Novel Chlorotoxin Derivatives CA4 and CTX-23 with Chemotherapeutic and Anti-Angiogenic Potential. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19799. [CrossRef]

- Majc, B.; Novak, M.; Lah, T.T.; Križaj, I. Bioactive Peptides from Venoms against Glioma Progression. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Samat, R.; Sen, S.; Jash, M.; Ghosh, S.; Garg, S.; Sarkar, J.; Ghosh, S. Venom: A Promising Avenue for Antimicrobial Therapeutics. ACS Infect Dis 2024, 10, 3098–3125. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.L.; Heath, G.R.; Johnson, B.R.G.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Strong, P.N.; Evans, S.D.; Miller, K. Phospholipid Dependent Mechanism of Smp24, an α-Helical Antimicrobial Peptide from Scorpion Venom. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2016, 1858, 2737–2744. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.L.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Strong, P.N.; Tawfik, M.M.; Miller, K. Characterisation of Three Alpha-Helical Antimicrobial Peptides from the Venom of Scorpio maurus palmatus. Toxicon 2016, 117, 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; He, D.; Wu, Y.; Kwok, H.F.; Cao, Z. Scorpion Venom Peptides: Molecular Diversity, Structural Characteristics, and Therapeutic Use from Channelopathies to Viral Infections and Cancers. Pharmacol Res 2023, 197, 106978. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, B.; Hu, J.; Yang, W.; Cao, Z.; Zhuo, R.; Li, W.; Wu, Y. SjAPI, the First Functionally Characterized Ascaris-Type Protease Inhibitor from Animal Venoms. PLoS One 2013, 8, e57529–e57529. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Dai, H.; Qiu, S.; Li, T.; He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, Z. SdPI, The First Functionally Characterized Kunitz-Type Trypsin Inhibitor from Scorpion Venom. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27548–e27548. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gong, K.; Yan, H.; Hong, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Cao, Z. Sj7170, a Unique Dual-Function Peptide with a Specific α-Chymotrypsin Inhibitory Activity and a Potent Tumor-Activating Effect from Scorpion Venom. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 11667–11680. [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; San, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; et al. A New Kunitz-Type Plasmin Inhibitor from Scorpion Venom. Toxicon 2015, 106, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Xu, Y.; San, M.; Tang, W.; Yang, F.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; et al. Functional Characterization of a New Non-Kunitz Serine Protease Inhibitor from the Scorpion Lychas mucronatus. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 72, 158–162. [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M.A.; Yang, S. Discoveries of Serine Protease Inhibitors from Scorpions. J Proteomics Bioinform 2016, 04. [CrossRef]

- Petricevich, V.L. Scorpion Venom and the Inflammatory Response. Mediators Inflamm 2010, 2010, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- El-Benna, J.; Hurtado-Nedelec, M.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.-A.; Dang, P.M.-C. Effects of Venoms on Neutrophil Respiratory Burst: A Major Inflammatory Function. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2021, 27. [CrossRef]

- Soltan-Alinejad, P.; Alipour, H.; Soltani, A.; Asgari, Q.; Ramezani, A.; Mehrabani, D.; Azizi, K. Molecular Characterization and In Silico Analyses of Maurolipin Structure as a Secretory Phospholipase A2 (sPLA) from Venom Glands of Iranian Scorpio maurus (Arachnida: Scorpionida). J Trop Med 2022, 2022, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Baradaran, M.; Salabi, F. Genome-Wide Identification, Structural Homology Analysis, and Evolutionary Diversification of the Phospholipase D Gene Family in the Venom Gland of Three Scorpion Species. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 730. [CrossRef]

- Salabi, F.; Jafari, H. Whole Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals the Activity of the PLA2 Family Members in Androctonus Crassicauda (Scorpionida: Buthidae) Venom Gland. The FASEB Journal 2024, 38. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Lomonte, B.; Chang-Castillo, A.; Bonilla, F.; Alfaro-Chinchilla, A.; Triana, F.; Angulo, D.; Fernández, J.; Sasa, M. Venomics of Scorpion Ananteris platnicki (Lourenço, 1993), a New World Buthid That Inhabits Costa Rica and Panama. Toxins (Basel) 2024, 16, 327. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Tobar, L.L.; Clement, H.; Arenas, I.; Sepulveda-Arias, J.C.; Vargas, J.A.G.; Corzo, G. An Overview of Some Enzymes from Buthid Scorpion Venoms from Colombia: Centruroides margaritatus, Tityus pachyurus, and Tityus n. Sp. Aff. Metuendus. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- Possani, L. Peptides and Genes Coding for Scorpion Toxins That Affect Ion-Channels. Biochimie 2000, 82, 861–868. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, P.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y. Peptides with Therapeutic Potential in the Venom of the Scorpion Buthus Martensii Karsch. Peptides (N.Y.) 2019, 115, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Mikaelian, A.G.; Traboulay, E.; Zhang, X.M.; Yeritsyan, E.; Pedersen, P.L.; Ko, Y.H.; Matalka, K.Z. Pleiotropic Anticancer Properties of Scorpion Venom Peptides: Rhopalurus princeps Venom as an Anticancer Agent. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020, Volume 14, 881–893. [CrossRef]

- Aissaoui-Zid, D.; Saada, M.-C.; Moslah, W.; Potier-Cartereau, M.; Lemettre, A.; Othman, H.; Gaysinski, M.; Abdelkafi-Koubaa, Z.; Souid, S.; Marrakchi, N.; et al. AaTs-1: A Tetrapeptide from Androctonus australis Scorpion Venom, Inhibiting U87 Glioblastoma Cells Proliferation by P53 and FPRL-1 Up-Regulations. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, H.; Ren, F.; Huang, L.; Xu, J.; Li, F. Protective Effect of Scorpion Venom Heat-Resistant Synthetic Peptide against PM2.5-Induced Microglial Polarization via TLR4-Mediated Autophagy Activating PI3K/AKT/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. J Neuroimmunol 2021, 355, 577567. [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Sheng, W.; Zhou, Q.; Fu, W. Astragalus–Scorpion Drug Pair Inhibits the Development of Prostate Cancer by Regulating GDPD4-2/PI3K/AKT/MTOR Pathway and Autophagy. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; El-Asmar, M.F.; Osman, O.H. Pharmacological Studies with Scorpion (Palamneus Gravimanus) Venom: Evidence for the Presence of Histamine. Toxicon 1975, 13, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Gomes, A.; Gomes, A.; Dasgupta, S.C.; Lahiri, S.C. Histamine, 5-HT & Hyaluronidase in the Venom of the Scorpion Lychas laevifrons (Pock). Indian J Med Res 1990, 92, 371–373.

- Kwon, N.-Y.; Sung, H.-K.; Park, J.-K. Systematic Review of the Antitumor Activities and Mechanisms of Scorpion Venom on Human Breast Cancer Cells Lines (In Vitro Study). J Clin Med 2025, 14, 3181. [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.R.J.; McIntyre, L.; Northfield, T.D.; Daly, N.L.; Wilson, D.T. Small Molecules in the Venom of the Scorpion Hormurus waigiensis. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 259. [CrossRef]

- Ageitos, L.; Torres, M.D.T.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Biologically Active Peptides from Venoms: Applications in Antibiotic Resistance, Cancer, and Beyond. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Soares, K.S.R.; Formiga, A.L.D.; Uchôa, A.F.C.; Cardoso, A.L.M.R.; Rodrigues, J.P.C.G.; Leite, J. de P.F.B.; Silva, L.F.A.; Alves, Á.E.F.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Xavier-Junior, F.H. Beyond the Peril of Envenomation: A Nanotechnology Approach for Therapeutic Venom Delivery. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2025, 105, 106652. [CrossRef]

- Cajado-Carvalho, D.; da Silva, C.C.F.; Kodama, R.T.; Mariano, D.O.C.; Pimenta, D.C.; Duzzi, B.; Kuniyoshi, A.K.; Portaro, F.V. Purification and Biochemical Characterization of TsMS 3 and TsMS 4: Neuropeptide-Degrading Metallopeptidases in the Tityus serrulatus Venom. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 194. [CrossRef]

- Cajado Carvalho, D.; Kuniyoshi, A.K.; Kodama, R.T.; Oliveira, A.K.; Serrano, S.M.T.; Tambourgi, D. V.; Portaro, F. V. Neuropeptide Y Family-Degrading Metallopeptidases in the Tityus serrulatus Venom Partially Blocked by Commercial Antivenoms. Toxicological Sciences 2014, 142, 418–426. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Guo, L.; Li, W. Molecular Diversity of Toxic Components from the Scorpion Heterometrus Petersii Venom Revealed by Proteomic and Transcriptome Analysis. Proteomics 2010, 10, 2471–2485. [CrossRef]

- Venancio, E.J.; Portaro, F.C. V; Kuniyoshi, A.K.; Carvalho, D.C.; Pidde-Queiroz, G.; Tambourgi, D. V Enzymatic Properties of Venoms from Brazilian Scorpions of Tityus Genus and the Neutralisation Potential of Therapeutical Antivenoms. Toxicon 2013, 69, 180–190. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chua, P.-J.; Bay, B.-H.; Gopalakrishnakone, P. Scorpion Venoms as a Potential Source of Novel Cancer Therapeutic Compounds. Exp Biol Med 2014, 239, 387–393. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, J.-E.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Green, D.R. Caspase-Mediated Loss of Mitochondrial Function and Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species during Apoptosis. J Cell Biol 2003, 160, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Nicholson, D.W. Cross-Talk in Cell Death Signaling. J Exp Med 2000, 192, F21-5.

- Basu, A.; Castle, V.P.; Bouziane, M.; Bhalla, K.; Haldar, S. Crosstalk between Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cell Death Pathways in Pancreatic Cancer: Synergistic Action of Estrogen Metabolite and Ligands of Death Receptor Family. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 4309–4318. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, H.; Xu, C.; Yuan, J. Cleavage of BID by Caspase 8 Mediates the Mitochondrial Damage in the Fas Pathway of Apoptosis. Cell 1998, 94, 491–501. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-M.; Wang, K.; Gross, A.; Zhao, Y.; Zinkel, S.; Klocke, B.; Roth, K.A.; Korsmeyer, S.J. Bid-Deficient Mice Are Resistant to Fas-Induced Hepatocellular Apoptosis. Nature 1999, 400, 886–891. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Budihardjo, I.; Zou, H.; Slaughter, C.; Wang, X. Bid, a Bcl2 Interacting Protein, Mediates Cytochrome c Release from Mitochondria in Response to Activation of Cell Surface Death Receptors. Cell 1998, 94, 481–490. [CrossRef]

- Srairi-Abid, N.; Othman, H.; Aissaoui, D.; BenAissa, R. Anti-Tumoral Effect of Scorpion Peptides: Emerging New Cellular Targets and Signaling Pathways. Cell Calcium 2019, 80, 160–174. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Mishra, R.; Biswas, A.K.; Dasgupta, S.C.; Giri, B. Anticancer Potential of Animal Venoms and Toxins. Indian J Exp Biol 2010, 48, 93–103.

- Kampo, S.; Ahmmed, B.; Zhou, T.; Owusu, L.; Anabah, T.W.; Doudou, N.R.; Kuugbee, E.D.; Cui, Y.; Lu, Z.; Yan, Q.; et al. Scorpion Venom Analgesic Peptide, BmK AGAP Inhibits Stemness, and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Down-Regulating PTX3 in Breast Cancer. Front Oncol 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Dardevet, L.; Najlaoui, F.; Aroui, S.; Collot, M.; Tisseyre, C.; Pennington, M.W.; Mallet, J.-M.; De Waard, M. A Conjugate between Lqh-8/6, a Natural Peptide Analogue of Chlorotoxin, and Doxorubicin Efficiently Induces Glioma Cell Death. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2605. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, S.; Sun, P.; Pan, H.; Tian, C.; Zhang, L. Peptide Toxins and Small-Molecule Blockers of BK Channels. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2016, 37, 56–66. [CrossRef]

- Giangiacomo, K.M.; Sugg, E.E.; Garcia-Calvo, M.; Leonard, R.J.; McManus, O.B.; Kaczorowski, G.J.; Garcia, M.L. Synthetic Charybdotoxin-Iberiotoxin Chimeric Peptides Define Toxin Binding Sites on Calcium-Activated and Voltage-Dependent Potassium Channels. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 2363–2370. [CrossRef]

- Bingham, J.-P.; Bian, S.; Tan, Z.-Y.; Takacs, Z.; Moczydlowski, E. Synthesis of a Biotin Derivative of Iberiotoxin: Binding Interactions with Streptavidin and the BK Ca 2+ -Activated K + Channel Expressed in a Human Cell Line. Bioconjug Chem 2006, 17, 689–699. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-X.; Ji, Y.-H. Scorpion Venom Induces Glioma Cell Apoptosis in Vivo and Inhibits Glioma Tumor Growth in Vitro. J Neurooncol 2005, 73, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Sui, W.-W.; Zhang, W.-D.; Wu, L.-C.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Z.-P.; Wang, Z.-X.; Jia, Q. [Study on the Mechanism of Polypeptide Extract from Scorpion Venom on Inhibition of Angiogenesis of H 22 Hepatoma]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2014, 34, 581–586.

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Wu, L.C.; Wang, Z.P.; Wang, Z.X.; Jia, Q.; Jiang, G.S.; Zhang, W.D. Anti-Proliferation Effect of Polypeptide Extracted from Scorpion Venom on Human Prostate Cancer Cells in Vitro. J Clin Med Res 2009, 1, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Marak, B.N.; Dowarah, J.; Khiangte, L.; Singh, V.P. A Comprehensive Insight on the Recent Development of Cyclic Dependent Kinase Inhibitors as Anticancer Agents. Eur J Med Chem 2020, 203, 112571. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Xu, C.; Chen, L.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Nie, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, E. Anti-Glioma Effect of Buthus Martensii Karsch (BmK) Scorpion by Inhibiting Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Activating T Cells in Tumor Microenvironment. J Funct Foods 2024, 116, 106163. [CrossRef]

- El-Qassas, J.; Abd El-Atti, M.; El-Badri, N. Harnessing the Potency of Scorpion Venom-Derived Proteins: Applications in Cancer Therapy. Bioresour Bioprocess 2024, 11, 93. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Gao, R.; Gopalakrishnakone, P. Isolation and Characterization of a Hyaluronidase from the Venom of Chinese Red Scorpion Buthus martensi. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2008, 148, 250–257. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Gao, R.; Meng, J.; Gopalakrishnakone, P. Cloning and Molecular Characterization of BmHYA1, a Novel Hyaluronidase from the Venom of Chinese Red Scorpion Buthus martensi Karsch. Toxicon 2010, 56, 474–479. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Xue, S.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, W.; Ding, K. Cloning and Molecular Characterization of Scorpion Buthus martensi Venom Hyaluronidases: A Novel Full-Length and Diversiform Noncoding Isoforms. Gene 2014, 547, 338–345. [CrossRef]

- DELPECH, B.; GIRARD, N.; BERTRAND, P.; COUREL, M. -N.; CHAUZY, C.; DELPECH, A. Hyaluronan: Fundamental Principles and Applications in Cancer. J Intern Med 1997, 242, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Naor, D.; Sionov, R.V.; Ish-Shalom, D. CD44: Structure, Function and Association with the Malignant Process. In; 1997; pp. 241–319.

- Khamessi, O.; Ben Mabrouk, H.; ElFessi-Magouri, R.; Kharrat, R. RK1, the First Very Short Peptide from Buthus occitanus tunetanus Inhibits Tumor Cell Migration, Proliferation and Angiogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 499, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Sinthuvanich, C.; Veiga, A.S.; Gupta, K.; Gaspar, D.; Blumenthal, R.; Schneider, J.P. Anticancer β-Hairpin Peptides: Membrane-Induced Folding Triggers Activity. J Am Chem Soc 2012, 134, 6210–6217. [CrossRef]

- Tolos (Vasii), A.M.; Moisa, C.; Dochia, M.; Popa, C.; Copolovici, L.; Copolovici, D.M. Anticancer Potential of Antimicrobial Peptides: Focus on Buforins. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16, 728. [CrossRef]

- DeBin, J.A.; Maggio, J.E.; Strichartz, G.R. Purification and Characterization of Chlorotoxin, a Chloride Channel Ligand from the Venom of the Scorpion. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 1993, 264, C361–C369. [CrossRef]

- Lippens, G.; Najib, J.; Wodak, S.J.; Tartar, A. NMR Sequential Assignments and Solution Structure of Chlorotoxin, a Small Scorpion Toxin That Blocks Chloride Channels. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Correnti, C.E.; Gewe, M.M.; Mehlin, C.; Bandaranayake, A.D.; Johnsen, W.A.; Rupert, P.B.; Brusniak, M.-Y.; Clarke, M.; Burke, S.E.; De Van Der Schueren, W.; et al. Screening, Large-Scale Production and Structure-Based Classification of Cystine-Dense Peptides. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 270–278. [CrossRef]

- Soroceanu, L.; Gillespie, Y.; Khazaeli, M.B.; Sontheimer, H. Use of Chlorotoxin for Targeting of Primary Brain Tumors. Cancer Res 1998, 58, 4871–4879.

- Lyons, S.A.; O’Neal, J.; Sontheimer, H. Chlorotoxin, a Scorpion-derived Peptide, Specifically Binds to Gliomas and Tumors of Neuroectodermal Origin. Glia 2002, 39, 162–173. [CrossRef]

- Deshane, J.; Garner, C.C.; Sontheimer, H. Chlorotoxin Inhibits Glioma Cell Invasion via Matrix Metalloproteinase-2. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 4135–4144. [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, N.; Bordey, A.; Gillespie, G.Y.; Sontheimer, H. Expression of Voltage-Activated Chloride Currents in Acute Slices of Human Gliomas. Neuroscience 1998, 83, 1161–1173. [CrossRef]

- McFerrin, M.B.; Sontheimer, H. A Role for Ion Channels in Glioma Cell Invasion. Neuron Glia Biol 2006, 2, 39–49.

- Dastpeyman, M.; Giacomin, P.; Wilson, D.; Nolan, M.J.; Bansal, P.S.; Daly, N.L. A C-Terminal Fragment of Chlorotoxin Retains Bioactivity and Inhibits Cell Migration. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 250. [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, K.; Ratliff, J.; Johnson, E.W.; Dahlberg, W.; Asara, J.M.; Misra, P.; Frangioni, J. V; Jacoby, D.B. Annexin A2 Is a Molecular Target for TM601, a Peptide with Tumor-Targeting and Anti-Angiogenic Effects. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 4366–4374. [CrossRef]

- Farkas, S.; Cioca, D.; Murányi, J.; Hornyák, P.; Brunyánszki, A.; Szekér, P.; Boros, E.; Horváth, P.; Hujber, Z.; Rácz, G.Z.; et al. Chlorotoxin Binds to Both Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 and Neuropilin 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299, 104998. [CrossRef]

- Mabunda, I.G.; Offor, B.C.; Muller, B.; Motadi, L.R.; Piater, L.A. Scorpion Venoms from the Buthidae Family: A Dual Study of Proteomic Composition and Anticancer Potentials. Toxicon 2025, 266, 108542. [CrossRef]

- Wiranowska, M.; Colina, L.O.; Johnson, J.O. Clathrin-Mediated Entry and Cellular Localization of Chlorotoxin in Human Glioma. Cancer Cell Int 2011, 11, 27. [CrossRef]

- Barish, M.E.; Aftabizadeh, M.; Hibbard, J.; Blanchard, M.S.; Ostberg, J.R.; Wagner, J.R.; Manchanda, M.; Paul, J.; Stiller, T.; Aguilar, B.; et al. Chlorotoxin-Directed CAR T Cell Therapy for Recurrent Glioblastoma: Interim Clinical Experience Demonstrating Feasibility and Safety. Cell Rep Med 2025, 6, 102302. [CrossRef]

- Mamelak, A.N.; Jacoby, D.B. Targeted Delivery of Antitumoral Therapy to Glioma and Other Malignancies with Synthetic Chlorotoxin (TM-601). Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2007, 4, 175–186. [CrossRef]

- Mamelak, A.N.; Rosenfeld, S.; Bucholz, R.; Raubitschek, A.; Nabors, L.B.; Fiveash, J.B.; Shen, S.; Khazaeli, M.B.; Colcher, D.; Liu, A.; et al. Phase I Single-Dose Study of Intracavitary-Administered Iodine-131-TM-601 in Adults With Recurrent High-Grade Glioma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2006, 24, 3644–3650. [CrossRef]

- Gribbin, T.E.; Senzer, N.; Raizer, J.J.; Shen, S.; Nabors, L.B.; Wiranowska, M.; Fiveash, J.B. A Phase I Evaluation of Intravenous (IV) 131 I-Chlorotoxin Delivery to Solid Peripheral and Intracranial Tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009, 27, e14507–e14507. [CrossRef]

- Patil, C.G.; Walker, D.G.; Miller, D.M.; Butte, P.; Morrison, B.; Kittle, D.S.; Hansen, S.J.; Nufer, K.L.; Byrnes-Blake, K.A.; Yamada, M.; et al. Phase 1 Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Fluorescence Imaging Study of Tozuleristide (BLZ-100) in Adults With Newly Diagnosed or Recurrent Gliomas. Neurosurgery 2019, 85, E641–E649. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Perlas, C.; Varese, M.; Guardiola, S.; García, J.; Sánchez-Navarro, M.; Giralt, E.; Teixidó, M. From Venoms to BBB-Shuttles. MiniCTX3: A Molecular Vector Derived from Scorpion Venom. Chem Commun (Camb) 2018, 54, 12738–12741. [CrossRef]

- Formicola, B.; Dal Magro, R.; Montefusco-Pereira, C. V; Lehr, C.-M.; Koch, M.; Russo, L.; Grasso, G.; Deriu, M.A.; Danani, A.; Bourdoulous, S.; et al. The Synergistic Effect of Chlorotoxin-MApoE in Boosting Drug-Loaded Liposomes across the BBB. J Nanobiotechnology 2019, 17, 115. [CrossRef]

- Reissmann, S.; Filatova, M.P. New Generation of Cell-penetrating Peptides: Functionality and Potential Clinical Application. Journal of Peptide Science 2021, 27. [CrossRef]

- Poillot, C.; Dridi, K.; Bichraoui, H.; Pêcher, J.; Alphonse, S.; Douzi, B.; Ronjat, M.; Darbon, H.; De Waard, M. D-Maurocalcine, a Pharmacologically Inert Efficient Cell-Penetrating Peptide Analogue. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 34168–34180. [CrossRef]

- Poillot, C.; Bichraoui, H.; Tisseyre, C.; Bahemberae, E.; Andreotti, N.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Ronjat, M.; De Waard, M. Small Efficient Cell-Penetrating Peptides Derived from Scorpion Toxin Maurocalcine. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 17331–17342. [CrossRef]

- Fajloun, Z.; Kharrat, R.; Chen, L.; Lecomte, C.; Di Luccio, E.; Bichet, D.; El Ayeb, M.; Rochat, H.; Allen, P.D.; Pessah, I.N.; et al. Chemical Synthesis and Characterization of Maurocalcine, a Scorpion Toxin That Activates Ca(2+) Release Channel/Ryanodine Receptors. FEBS Lett 2000, 469, 179–185. [CrossRef]

- Estève, E.; Mabrouk, K.; Dupuis, A.; Smida-Rezgui, S.; Altafaj, X.; Grunwald, D.; Platel, J.-C.; Andreotti, N.; Marty, I.; Sabatier, J.-M.; et al. Transduction of the Scorpion Toxin Maurocalcine into Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 12833–12839. [CrossRef]

- Ram, N.; Weiss, N.; Texier-Nogues, I.; Aroui, S.; Andreotti, N.; Pirollet, F.; Ronjat, M.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Darbon, H.; Jacquemond, V.; et al. Design of a Disulfide-Less, Pharmacologically Inert, and Chemically Competent Analog of Maurocalcine for the Efficient Transport of Impermeant Compounds into Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 27048–27056. [CrossRef]

- Tisseyre, C.; Bahembera, E.; Dardevet, L.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Ronjat, M.; De Waard, M. Cell Penetration Properties of a Highly Efficient Mini Maurocalcine Peptide. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 320–339. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zou, X.; Cheng, K.; Zhong, S.; Su, Y.; Wu, T.; Tao, Y.; Cong, L.; Yan, B.; Jiang, Y. The Role of Cell-penetrating Peptides in Potential Anti-cancer Therapy. Clin Transl Med 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Prudencio, G.; Possani, L.D.; Becerril, B.; Ortiz, E. The Dual α-Amidation System in Scorpion Venom Glands. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 425. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, M.; Sun, J.; Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Qin, J.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Z. Unveiling the Diversity and Modifications of Short Peptides in Buthus martensii Scorpion Venom through Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Toxins (Basel) 2024, 16, 155. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The Blood–Brain Barrier: Structure, Regulation and Drug Delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 217. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Sun, Z.; Jiang, D.; Dai, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W. BmKCT Toxin Inhibits Glioma Proliferation and Tumor Metastasis. Cancer Lett 2010, 291, 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Mohamed, M.S.; Mizuki, T.; Maekawa, T.; Sakthi Kumar, D. Chlorotoxin Modified Morusin–PLGA Nanoparticles for Targeted Glioblastoma Therapy. J Mater Chem B 2019, 7, 5896–5919. [CrossRef]

- Veiseh, M.; Gabikian, P.; Bahrami, S.-B.; Veiseh, O.; Zhang, M.; Hackman, R.C.; Ravanpay, A.C.; Stroud, M.R.; Kusuma, Y.; Hansen, S.J.; et al. Tumor Paint: A Chlorotoxin:Cy5.5 Bioconjugate for Intraoperative Visualization of Cancer Foci. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 6882–6888. [CrossRef]

- Mata de los Rios, N.; Gastelum-Arellanez, A.; Clement, H.; Álvarez-Cruz, K.; Romero-Terrazas, D.; Alvarado-González, C.; Hinojos-Gallardo, L.C.; Corzo, G.; Espino-Solis, G.P. Ion-Channel-Targeting Scorpion Recombinant Toxin as Novel Therapeutic Agent for Breast Cancer. Toxins (Basel) 2025, 17, 166. [CrossRef]

- Pucca, M.B.; Peigneur, S.; Cologna, C.T.; Cerni, F.A.; Zoccal, K.F.; Bordon, K. de C.F.; Faccioli, L.H.; Tytgat, J.; Arantes, E.C. Electrophysiological Characterization of the First Tityus serrulatus Alpha-like Toxin, Ts5: Evidence of a pro-Inflammatory Toxin on Macrophages. Biochimie 2015, 115, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, P. Mechanistic Insights into Nav1.7-dependent Regulation of Rat Prostate Cancer Cell Invasiveness Revealed by Toxin Probes and Proteomic Analysis. FEBS J 2019, 286, 2549–2561. [CrossRef]

- Soroceanu, L.; Manning, T.J.; Sontheimer, H. Modulation of Glioma Cell Migration and Invasion Using Cl − and K + Ion Channel Blockers. The Journal of Neuroscience 1999, 19, 5942–5954. [CrossRef]

- Cota-Arce, J.M.; Zazueta-Favela, D.; Díaz-Castillo, F.; Jiménez, S.; Bernáldez-Sarabia, J.; Caram-Salas, N.L.; Dan, K.W.L.; Escobedo, G.; Licea-Navarro, A.F.; Possani, L.D.; et al. Venom Components of the Scorpion Centruroides Limpidus Modulate Cytokine Expression by T Helper Lymphocytes: Identification of Ion Channel-Related Toxins by Mass Spectrometry. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 84, 106505. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Oh, J.H.; Kang, H.K.; Choi, M.-C.; Seo, C.H.; Park, Y. Scorpion-Venom-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Css54 Exerts Potent Antimicrobial Activity by Disrupting Bacterial Membrane of Zoonotic Bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 831. [CrossRef]

- Zoccal, K.F.; Bitencourt, C. da S.; Paula-Silva, F.W.G.; Sorgi, C.A.; de Castro Figueiredo Bordon, K.; Arantes, E.C.; Faccioli, L.H. TLR2, TLR4 and CD14 Recognize Venom-Associated Molecular Patterns from Tityus serrulatus to Induce Macrophage-Derived Inflammatory Mediators. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88174. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Lin, N.; Guan, T.; Song, X.; Hong, S. Scorpion Venom Polypeptide Governs Alveolar Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization to Alleviate Pulmonary Fibrosis. Tissue Cell 2022, 79, 101939. [CrossRef]

- Yglesias-Rivera, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, H.; Soto-Febles, C.; Monzote, L. Heteroctenus junceus Scorpion Venom Modulates the Concentration of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in F3II Tumor Cells. Life 2023, 13, 2287. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, A.; Ruiz-Fuentes, J.L.; Frión-Herrera, Y.; Yglesias-Rivera, A.; Garlobo, Y.R.; Sánchez, H.R.; Aurrecochea, J.C.R.; López Fuentes, L.X. Rhopalurus junceus Scorpion Venom Induces Antitumor Effect in Vitro and in Vivo against a Murine Mammary Adenocarcinoma Model. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2019, 22, 759–765. [CrossRef]

- Zoccal, K.F.; Paula-Silva, F.W.G.; Bitencourt, C. da S.; Sorgi, C.A.; Bordon, K. de C.F.; Arantes, E.C.; Faccioli, L.H. PPAR-γ Activation by Tityus serrulatus Venom Regulates Lipid Body Formation and Lipid Mediator Production. Toxicon 2015, 93, 90–97. [CrossRef]

- Ait-Lounis, A.; Laraba-Djebari, F. TNF-Alpha Modulates Adipose Macrophage Polarization to M1 Phenotype in Response to Scorpion Venom. Inflamm Res 2015, 64, 929–936. [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, K.N.; Ramesh, D.; Ramesh, D.; Nagaraj, U.; Shrinidhi, S.; Thippeswamy, N.B. Scorpion Venom Exhibits Adjuvant Effect by Eliciting HBsAg-Specific Th1 Immunity through Neuro-Endocrine Interactions. Mol Immunol 2022, 147, 136–146. [CrossRef]

- Gurrola, G.B.; Hernández-López, R.A.; Rodríguez de la Vega, R.C.; Varga, Z.; Batista, C.V.F.; Salas-Castillo, S.P.; Panyi, G.; del Río-Portilla, F.; Possani, L.D. Structure, Function, and Chemical Synthesis of Vaejovis Mexicanus Peptide 24: A Novel Potent Blocker of Kv1.3 Potassium Channels of Human T Lymphocytes. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 4049–4061. [CrossRef]

- Veytia-Bucheli, J.I.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Melchy-Pérez, E.I.; Sandoval-Hernández, M.A.; Possani, L.D.; Rosenstein, Y. Kv1.3 Channel Blockade with the Vm24 Scorpion Toxin Attenuates the CD4+ Effector Memory T Cell Response to TCR Stimulation. Cell Communication and Signaling 2018, 16, 45. [CrossRef]

- Chimote, A.A.; Hajdu, P.; Sfyris, A.M.; Gleich, B.N.; Wise-Draper, T.; Casper, K.A.; Conforti, L. Kv1.3 Channels Mark Functionally Competent CD8+ Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, S.; Tang, J.; Hou, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Jin, M. Two Small Peptides from Buthus martensii Hydrolysates Exhibit Antitumor Activity Through Inhibition of TNF-α-Mediated Signal Transduction Pathways. Life 2025, 15, 105. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M.M.; Pereira, M.E.S.; Amaral, C.F.S.; Rezende, N.A.; Campolina, D.; Bucaretchi, F.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Cunha-Melo, J.R. Serum Levels of Cytokines in Patients Envenomed by Tityus serrulatus Scorpion Sting. Toxicon 1999, 37, 1155–1164. [CrossRef]

- Gunas, V.; Maievskyi, O.; Synelnyk, T.; Raksha, N.; Vovk, T.; Halenova, T.; Savchuk, O.; Gunas, I. Cytokines and Their Regulators in Rat Lung Following Scorpion Envenomation. Toxicon X 2024, 22, 100198. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yi, X.; Du, R.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Q. Scorpion Venom Peptides Enhance Immunity and Survival in Litopenaeus vannamei through Antibacterial Action against Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. Front Immunol 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; De Sanctis, J.B. Specific Activation of Human Neutrophils by Scorpion Venom: A Flow Cytometry Assessment. Toxicology in Vitro 2011, 25, 358–367. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahnia, A.; Bahmani, K.; Aliahmadi, A.; As’habi, M.A.; Ghassempour, A. Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Odonthobuthus doriae Scorpion Venom and Its Non-Neutralized Fractions after Interaction with Commercial Antivenom. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 10389. [CrossRef]

- Zoccal, K.F.; Bitencourt, C. da S.; Secatto, A.; Sorgi, C.A.; Bordon, K. de C.F.; Sampaio, S.V.; Arantes, E.C.; Faccioli, L.H. Tityus serrulatus Venom and Toxins Ts1, Ts2 and Ts6 Induce Macrophage Activation and Production of Immune Mediators. Toxicon 2011, 57, 1101–1108. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Eauclaire, M.-F.; Bougis, P.E.; de Lima, M.E. Ts1 from the Brazilian Scorpion Tityus serrulatus: A Half-Century of Studies on a Multifunctional Beta like-Toxin. Toxicon 2018, 152, 106–120. [CrossRef]

- Shariati, S.; Mafakher, L.; Shirani, M.; Baradaran, M. Unveiling New Kv1.3 Channel Blockers from Scorpion Venom: Characterization of Meuk7–3 and in Silico Design of Its Analogs for Enhanced Affinity and Therapeutic Potential. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 319, 145327. [CrossRef]

- López-Giraldo, E.; Carrillo, E.; Titaux-Delgado, G.; Cano-Sánchez, P.; Colorado, A.; Possani, L.D.; Río-Portilla, F. del Structural and Functional Studies of Scorpine: A Channel Blocker and Cytolytic Peptide. Toxicon 2023, 222, 106985. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, C.; Zhong, C.; Li, W.; Shang, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y. Engineered Bacteria-Mediated Delivery of Scorpion Venom Peptide AGAP for Targeted Breast Cancer Therapy. Curr Microbiol 2025, 82, 323. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Starr, R.; Chang, W.-C.; Aguilar, B.; Alizadeh, D.; Wright, S.L.; Yang, X.; Brito, A.; Sarkissian, A.; Ostberg, J.R.; et al. Chlorotoxin-Directed CAR T Cells for Specific and Effective Targeting of Glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zargan, J.; Sajad, M.; Umar, S.; Naime, M.; Ali, S.; Khan, H.A. Scorpion (Androctonus crassicauda) Venom Limits Growth of Transformed Cells (SH-SY5Y and MCF-7) by Cytotoxicity and Cell Cycle Arrest. Exp Mol Pathol 2011, 91, 447–454. [CrossRef]

- Salabi, F.; Jafari, H. Differential Venom Gland Gene Expression Analysis of Juvenile and Adult Scorpions Androctonus crassicauda. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 636. [CrossRef]

- Butte, P. V; Mamelak, A.; Parrish-Novak, J.; Drazin, D.; Shweikeh, F.; Gangalum, P.R.; Chesnokova, A.; Ljubimova, J.Y.; Black, K. Near-Infrared Imaging of Brain Tumors Using the Tumor Paint BLZ-100 to Achieve near-Complete Resection of Brain Tumors. Neurosurg Focus 2014, 36, E1–E1. [CrossRef]

- Fidel, J.; Kennedy, K.C.; Dernell, W.S.; Hansen, S.; Wiss, V.; Stroud, M.R.; Molho, J.I.; Knoblaugh, S.E.; Meganck, J.; Olson, J.M.; et al. Preclinical Validation of the Utility of BLZ-100 in Providing Fluorescence Contrast for Imaging Spontaneous Solid Tumors. Cancer Res 2015, 75, 4283–4291. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, I.; Paoloni, M.; Mazcko, C.; Khanna, C. The Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium: Using Spontaneously Occurring Cancers in Dogs to Inform the Cancer Drug Development Pathway. PLoS Med 2009, 6, e1000161–e1000161. [CrossRef]

- Parrish-Novak, J.; Byrnes-Blake, K.; Lalayeva, N.; Burleson, S.; Fidel, J.; Gilmore, R.; Gayheart-Walsten, P.; Bricker, G.A.; Crumb, W.J.; Tarlo, K.S.; et al. Nonclinical Profile of BLZ-100, a Tumor-Targeting Fluorescent Imaging Agent. Int J Toxicol 2017, 36, 104–112. [CrossRef]

- Kobets, A.J.; Nauen, D.; Lee, A.; Cohen, A.R. Unexpected Binding of Tozuleristide “Tumor Paint” to Cerebral Vascular Malformations: A Potentially Novel Application of Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. Neurosurgery 2021, 89, 204–211. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Miller, D.M.; Lowe, M.; Rowe, C.; Wood, D.; Soyer, H.P.; Byrnes-Blake, K.; Parrish-Novak, J.; Ishak, L.; Olson, J.M.; et al. A First-in-Human Study of BLZ-100 (Tozuleristide) Demonstrates Tolerability and Safety in Skin Cancer Patients. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2021, 23, 100830. [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Saviola, A.J.; Mukherjee, A.K. Biochemical and Proteomic Characterization, and Pharmacological Insights of Indian Red Scorpion Venom Toxins. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Puzari, U.; Das, B.; Mukherjee, A.K. Advancements in Diagnostic Techniques for Scorpion Venom Identification: A Comprehensive Review. Toxicon 2025, 253, 108191. [CrossRef]

- Puzari, U.; Khan, M.R.; Mukherjee, A.K. Development of a Gold Nanoparticle-Based Novel Diagnostic Prototype for in Vivo Detection of Indian Red Scorpion (Mesobuthus Tamulus) Venom. Toxicon X 2024, 23, 100203. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Mittal, R.; Kumar, M.; Mittal, A.; Kushwah, A.S. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Biosensors for Point-of-Care Diagnostics: A Review of Sensing Nanoparticle Applications and Future Prospects. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 2025, 28, 417–434. [CrossRef]

- Medley, C.D.; Smith, J.E.; Tang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Bamrungsap, S.; Tan, W. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Assay for the Direct Detection of Cancerous Cells. Anal Chem 2008, 80, 1067–1072. [CrossRef]

- Appidi, T.; Mudigunda, S. V; Kodandapani, S.; Rengan, A.K. Development of Label-Free Gold Nanoparticle Based Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Clinical/Point-of-Care Screening of Cervical Cancer. Nanoscale Adv 2020, 2, 5737–5745. [CrossRef]

- Pedarzani, P.; D’hoedt, D.; Doorty, K.B.; Wadsworth, J.D.F.; Joseph, J.S.; Jeyaseelan, K.; Kini, R.M.; Gadre, S.V.; Sapatnekar, S.M.; Stocker, M.; et al. Tamapin, a Venom Peptide from the Indian Red Scorpion (Mesobuthus Tamulus) That Targets Small Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels and Afterhyperpolarization Currents in Central Neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 46101–46109. [CrossRef]

- Luis, E.; Anaya-Hernández, A.; León-Sánchez, P.; Durán-Pastén, M.L. The Kv10.1 Channel: A Promising Target in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Ouadid-Ahidouch, H.; Ahidouch, A.; Pardo, L.A. Kv10.1 K+ Channel: From Physiology to Cancer. Pflugers Arch 2016, 468, 751–762. [CrossRef]

- Cázares-Ordoñez, V.; Pardo, L.A. Kv10.1 Potassium Channel: From the Brain to the Tumors. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2017, 95, 531–536. [CrossRef]

- Khamehchian, S.; Nikkhah, M.; Madani, R.; Hosseinkhani, S. Enhanced and Selective Permeability of Gold Nanoparticles Functionalized with Cell Penetrating Peptide Derived from Maurocalcine Animal Toxin. J Biomed Mater Res A 2016, 104, 2693–2700. [CrossRef]

- Kievit, F.M.; Veiseh, O.; Fang, C.; Bhattarai, N.; Lee, D.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Zhang, M. Chlorotoxin Labeled Magnetic Nanovectors for Targeted Gene Delivery to Glioma. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4587–4594. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Sun, N.; Song, N.; Xing, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhao, J. Chlorotoxin Peptide-Functionalized Polyethylenimine-Entrapped Gold Nanoparticles for Glioma SPECT/CT Imaging and Radionuclide Therapy. J Nanobiotechnology 2019, 17, 30. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Lyu, X.; Han, C. Investigation on the Mechanisms of Scorpion Venom in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Model Mice via Untargeted Metabolomics Profiling. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 138, 112578. [CrossRef]

- Mazhdi, Y.; Hamidi, S.M. Detection of Scorpion Venom by Optical Circular Dichroism Method. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 15854. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Veiseh, O.; Gunn, J.; Fang, C.; Hansen, S.; Lee, D.; Sze, R.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Olson, J.; Zhang, M. In Vivo MRI Detection of Gliomas by Chlorotoxin-Conjugated Superparamagnetic Nanoprobes. Small 2008, 4, 372–379. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shi, X.; Zhao, J. Chlorotoxin-Conjugated Nanoparticles for Targeted Imaging and Therapy of Glioma. Curr Top Med Chem 2015, 15, 1196–1208. [CrossRef]

- WANG, X.; GUO, Z. Chlorotoxin-Conjugated Onconase as a Potential Anti-Glioma Drug. Oncol Lett 2015, 9, 1337–1342. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.M.; Cardoso, A.L.; Mendonça, L.S.; Serani, A.; Custódia, C.; Conceição, M.; Simões, S.; Moreira, J.N.; Pereira de Almeida, L.; Pedroso de Lima, M.C. Tumor-Targeted Chlorotoxin-Coupled Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery to Glioblastoma Cells: A Promising System for Glioblastoma Treatment. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2013, 2, e100. [CrossRef]

- Amen, R.A.; Abd-Ellatef, G.E.F. Scorpion Venom and Its Different Peptides Aid in Treatment Focusing on Cancer Disease with the Mechanism of Action. Trends in Pharmacy 2025, 1, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Rjeibi, I.; Mabrouk, K.; Mosrati, H.; Berenguer, C.; Mejdoub, H.; Villard, C.; Laffitte, D.; Bertin, D.; Ouafik, L.; Luis, J.; et al. Purification, Synthesis and Characterization of AaCtx, the First Chlorotoxin-like Peptide from Androctonus australis Scorpion Venom. Peptides (N.Y.) 2011, 32, 656–663. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ke, W.; Han, L.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, C. Targeted Delivery of Chlorotoxin-Modified DNA-Loaded Nanoparticles to Glioma via Intravenous Administration. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2399–2406. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Alajangi, H.K.; Sharma, A.; Hwang, E.; Khajuria, A.; Kumari, L.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Lim, Y.; Singh, G.; Barnwal, R.P. Stigmurin Encapsulated PLA–PEG Ameliorates Its Therapeutic Potential, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activities. Discover Nano 2025, 20, 50. [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari, F.; Rahmati, S.; Ghanbari, A.; Madanchi, H.; Rashidy-Pour, A. Identification and Designing an Analgesic Opioid Cyclic Peptide from Defensin 4 of Mesobuthus martensii Karsch Scorpion Venom with More Effectiveness than Morphine. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2025, 188, 118139. [CrossRef]

- Ghodeif, S.K.; El-Fahla, N.A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; El-Shenawy, N.S. Arthropod Venom Peptides: Pioneering Nanotechnology in Cancer Treatment and Drug Delivery. Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy 2025. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.; Nicol, J.R.; Macias–Montero, M.; Burke, G.A.; Coulter, J.A.; Meenan, B.J.; Dixon, D. A Comparison of Gold Nanoparticle Surface Co-Functionalization Approaches Using Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) and the Effect on Stability, Non-Specific Protein Adsorption and Internalization. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2016, 62, 710–718. [CrossRef]

- Gláucia-Silva, F.; Torres, J.V.P.; Torres-Rêgo, M.; Daniele-Silva, A.; Furtado, A.A.; Ferreira, S. de S.; Chaves, G.M.; Xavier-Júnior, F.H.; Rocha Soares, K.S.; Silva-Júnior, A.A. da; et al. Tityus Stigmurus-Venom-Loaded Cross-Linked Chitosan Nanoparticles Improve Antimicrobial Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 9893. [CrossRef]

- Rebbouh, F.; Martin-Eauclaire, M.-F.; Laraba-Djebari, F. Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Delivery Platform for Neurotoxin II from Androctonus australis hector Scorpion Venom: Assessment of Toxicity and Immunogenicity. Acta Trop 2020, 205, 105353. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; An, N.; Li, K.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, A. Chlorotoxin-Conjugated Nanoparticles as Potential Glioma-Targeted Drugs. J Neurooncol 2012, 107, 457–462. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Yang, T.; Yang, J.; Fu, S.; Zhang, S. Targeting Strategies for Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Cancer Therapy. Acta Biomater 2020, 102, 13–34. [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; He, L.; Qiu, S.; Li, Y.; Liao, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, D.; Peng, Y. OX26/CTX-Conjugated PEGylated Liposome as a Dual-Targeting Gene Delivery System for Brain Glioma. Mol Cancer 2014, 13, 191. [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.J.; Ellsworth, S.A.; Nystrom, G.S. A Global Accounting of Medically Significant Scorpions: Epidemiology, Major Toxins, and Comparative Resources in Harmless Counterparts. Toxicon 2018, 151, 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shao, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, D.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Su, W.; Fang, L. Chlorotoxin-Derived Bicyclic Peptides for Targeted Imaging of Glioblastomas. Chemical Communications 2020, 56, 9537–9540. [CrossRef]

- Baik, F.M.; Hansen, S.; Knoblaugh, S.E.; Sahetya, D.; Mitchell, R.M.; Xu, C.; Olson, J.M.; Parrish-Novak, J.; Méndez, E. Fluorescence Identification of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and High-Risk Oral Dysplasia With BLZ-100, a Chlorotoxin-Indocyanine Green Conjugate. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2016, 142, 330. [CrossRef]

- Dintzis, S.M.; Hansen, S.; Harrington, K.M.; Tan, L.C.; Miller, D.M.; Ishak, L.; Parrish-Novak, J.; Kittle, D.; Perry, J.; Gombotz, C.; et al. Real-Time Visualization of Breast Carcinoma in Pathology Specimens From Patients Receiving Fluorescent Tumor-Marking Agent Tozuleristide. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019, 143, 1076–1083. [CrossRef]

- Klint, J.K.; Senff, S.; Saez, N.J.; Seshadri, R.; Lau, H.Y.; Bende, N.S.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Rash, L.D.; Mobli, M.; King, G.F. Production of Recombinant Disulfide-Rich Venom Peptides for Structural and Functional Analysis via Expression in the Periplasm of E. Coli. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63865–e63865. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lee, C.-J.; Park, J.-S. Strategies for Optimizing the Production of Proteins and Peptides with Multiple Disulfide Bonds. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 541. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Aziz, T.M.; Soares, A.G.; Stockand, J.D. Advances in Venomics: Modern Separation Techniques and Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B 2020, 1160, 122352. [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.B.; de Souza, B.M.; Cocchi, F.K.; Chalkidis, H.M.; Dorce, V.A.C.; Palma, M.S. Profiling the Short, Linear, Non-Disulfide Bond-Containing Peptidome from the Venom of the Scorpion Tityus obscurus. J Proteomics 2018, 170, 70–79. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, Z. Extreme Diversity of Scorpion Venom Peptides and Proteins Revealed by Transcriptomic Analysis: Implication for Proteome Evolution of Scorpion Venom Arsenal. J Proteomics 2012, 75, 1563–1576. [CrossRef]

- Bordon, K.; Santos, G.; Martins, J.; Wiezel, G.; Amorim, F.; Crasset, T.; Redureau, D.; Quinton, L.; Procópio, R.; Arantes, E. Pioneering Comparative Proteomic and Enzymatic Profiling of Amazonian Scorpion Venoms Enables the Isolation of Their First α-Ktx, Metalloprotease, and Phospholipase A2. Toxins (Basel) 2025, 17, 411. [CrossRef]

- García-Villalvazo, P.E.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Lino-López, G.J.; Meneses, E.P.; Bermúdez-Guzmán, M. de J.; Barajas-Saucedo, C.E.; Delgado Enciso, I.; Possani, L.D.; Valdez-Velazquez, L.L. Unveiling the Protein Components of the Secretory-Venom Gland and Venom of the Scorpion Centruroides Possanii (Buthidae) through Omic Technologies. Toxins (Basel) 2023, 15, 498. [CrossRef]