2. Case Outline:

A 58 year old male presented to the emergency department three times over one week with symptoms of chest pain, blurred vision and a visual change similar to “watching a cartoon”. He had a background history of obesity, poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, chronic hazardous alcohol use and a 50 pack-year cigarette smoking history. No acute cardiac cause for his chest pain was found and no focal neurological signs were elicited. He was referred for outpatient coronary angiography, with neurology and endocrinology follow-up arranged.

He then represented, brought in by the police, found wandering the streets and behaving in an erratic and aggressive way, with disorientation and disordered speech and thought content. He was admitted under general medicine for a delirium work-up and was placed on an alcohol withdrawal management pathway. A psychiatry review was requested as was a CT brain.

The CT brain showed several lesions, most prominent in the right parieto-occipital area. These lesions had broad differential diagnoses including sub-acute cerebrovascular infarction and neoplasia. An MRI brain was recommended for better characterisation.

While awaiting the MRI brain, the patient developed an altered level of consciousness, with transient drop of GCS to 9, and then two grand mal seizures of up to 90 seconds each.

He was intubated and was admitted to the intensive care unit where he was treated with sodium valproate and midazolam.

CSF examination revealed no atypical lymphocytes or other malignant cells on cyto-spin and no clonal B lymphocytes on flow cytometry immunophenotyping studies. Total protein was elevated at 2.24 g/L (RR: 0.15 – 0.45 g/L); glucose was elevated at 5.6 mmol/L (RR: 2.5 – 4.5 mmol/L); normal serum ACE level at <8 U/L. Assessment for mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative by PCR for TB DNA and negative by culture after 8 weeks; fungal culture was also negative. CSF nucleic acid PCR did not detect Enterovirus, Herpes virus types 1 and 2, Neisseria meningitidis, Strep pneumoniae, Varicella zoster and Parechovirus.

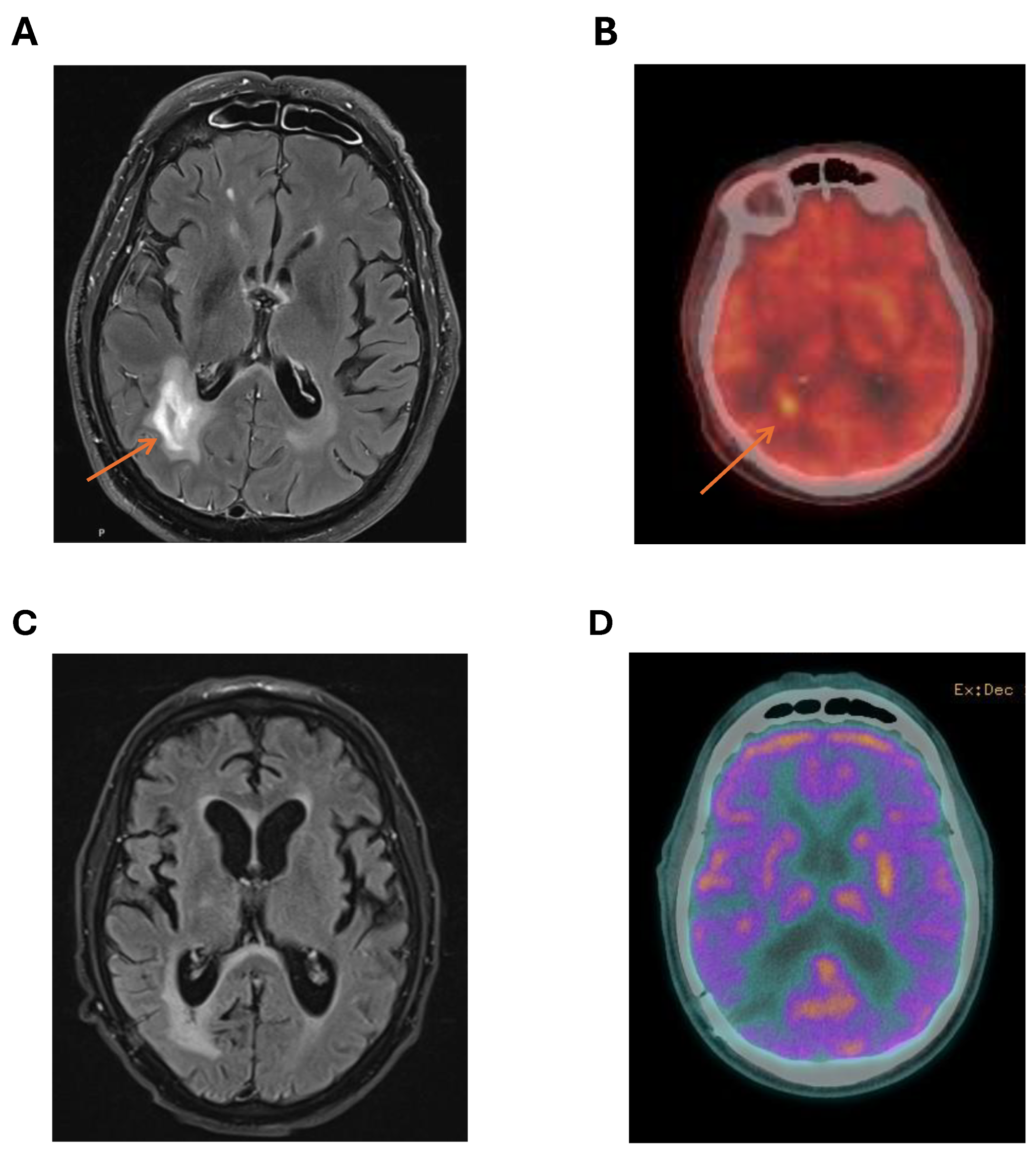

MRI brain provided better characterisation of the cerebral lesions with DWI and T2 flare enhancement of right parieto-occipital lesions (

figure 1A). The most favoured diagnosis was cerebral lymphoma. A PET scan showed no FDG avid lesions outside the CNS with marked FDG avidity of the right parieto-occipital lesions (

figure 1B). There was no ocular involvement with lymphoma. MRI spine was not performed. Testicular ultrasound showed no lesions suspicious for testicular lymphoma.

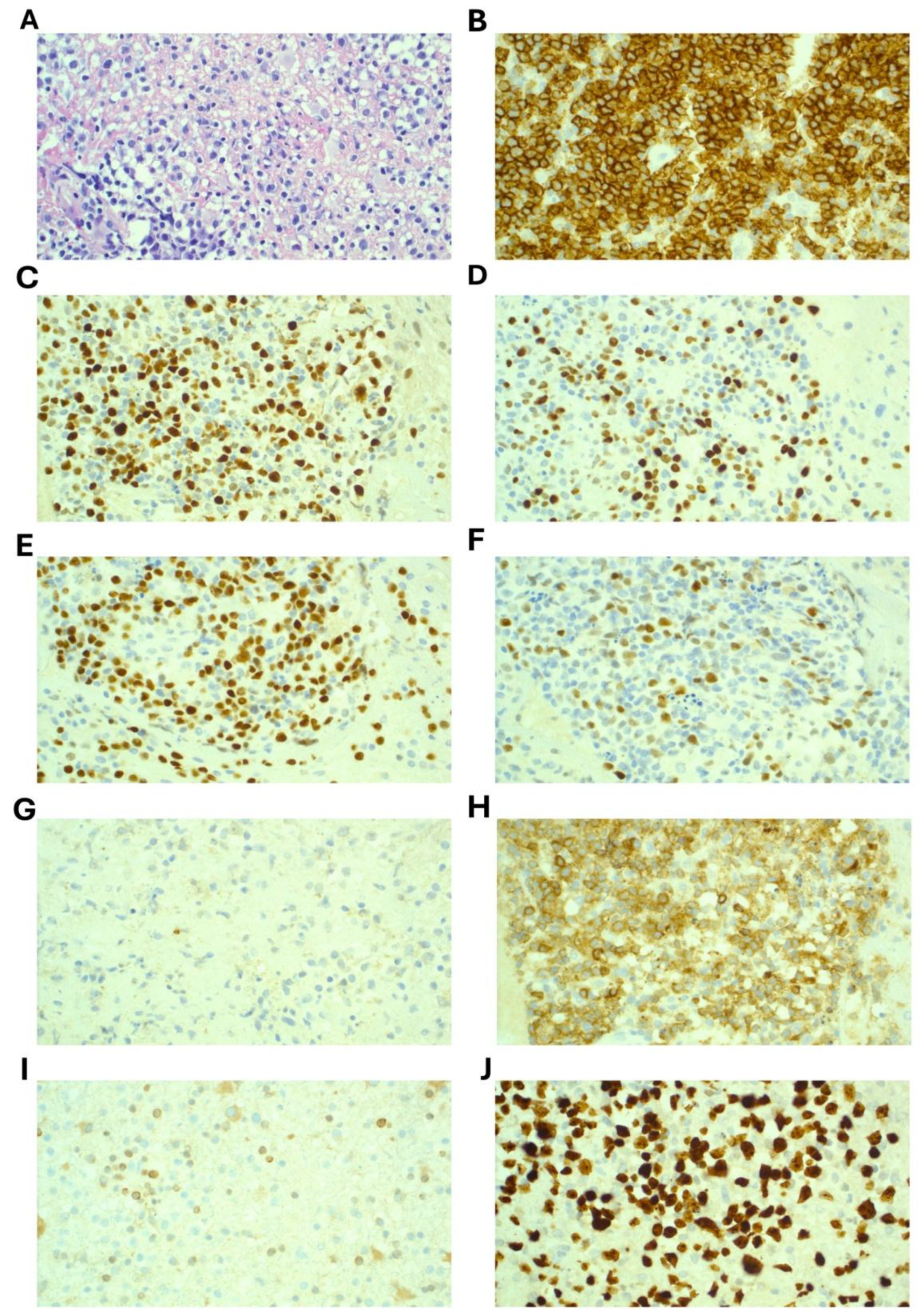

A stereotactic brain biopsy was performed which demonstrated sheets of large cells with immunohistochemistry positive for CD20, CD79a, CD45, BCL-6, PAX5 and MUM1. CD10 showed weak and cytoplasmic staining only and was considered negative. BCL-2 was negative and Ki67 was 90% (

Figure 2). EBER-ISH was negative. MYC was not rearranged on FISH analysis. A diagnosis of Primary CNS Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (PCNSL) was confirmed. Molecular testing revealed variants in these genes:

MYD88 (c.794 T>C; p.Leu265Pro) with VRF 13%;

CD79B (c.587 A>C; p.Tyr196Ser) with VRF 22%; and

CARD11 (c.1135 C>T; p.Arg379Trp) with VRF 9%.

Prior to treatment, neuropsychological testing revealed significant impairment in executive function. Baseline organ function was satisfactory with eGFR > 90 mL/min, normal liver function tests, normal left ventricular and systolic function with ejection fraction of approximately 60%. Baseline lung function was not performed. Plain chest x-ray was unremarkable. Charlson comorbidity index score was 7. Karnofsky performance scale score was 25. ECOG score was 2.

Following discussion at the institutional lymphoma multidisciplinary team meeting, treatment was commenced using the MATRix protocol (Methrotrexate, Ara-C, Thiotepa, Rituximab) with the plan to complete 4 cycles of induction therapy and then consolidate with carmustine and thiotepa conditioning therapy and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). MRI after 2 cycles showed significant reduction in the right parieto-occipital lesion. However, following cycle 3 of MATRix, the patient experienced significant therapy-limiting toxicities and complications including: severe renal impairment from methotrexate and delayed methotrexate clearance; moderate to severe lung-biopsy proven cryptogenic organising pneumonia (COP); pan-hypopituitarism; and COVID-19 infection. MRI (

Figure 1C) and cerebral PET (

Figure 1D) following cycle 3 showed further reduction in size of the right parieto-occipital lesion with reduced FDG avidity on PET (Deauville 3) suggestive of a complete metabolic response.

Continuing intensive chemotherapy was considered unsafe for the patient given the described complications and his medical co-morbidities. The consensus reached on repeat discussion in the lymphoma MDT meeting regarding best option for consolidation was that whole-brain radiotherapy was likely to cause significant cognitive morbidity given his poor performance status and his pre-existing neuropsychological impairment. Additionally, he was at high risk of death from complications of an autologous transplant given his COVID-19 infection and COP.

Emerging evidence supporting the efficacy of Bruton Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) inhibitors (BTKi) in relapsed and refractory PCNSL with evidence of good response, prompted us to initiate BTK inhibition as a consolidation and maintenance strategy. Our aim was to sustain the apparent complete remission achieved, facilitate rehabilitation, and thereby enable the possibility to proceed to an autologous stem cell transplant contingent on sufficient functional recovery. Given the patient had significant cardiovascular risk factors, a second-generation BTKi was preferred. As use in primary CNS lymphoma is not a recognised indication in Australia for funding through the pharmaceutical benefits scheme, we sought and were granted compassionate access to acalabrutinib (Astrazeneca, Australia). This was commenced at a dose of 100mg twice daily in February 2024. This dose was chosen as it is the standard dose when used in the chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and mantle cell lymphoma settings.

The patient tolerated acalabrutinib with no toxicity and has remained in clinical and radiological remission for 18 months following commencement of acalabrutinib. His COP was treated with prednisolone that was weaned slowly over 3 months with complete resolution of respiratory symptoms and radiological abnormalities. He became COVID-19 PCR negative after 2 months. Over 3 months he also underwent in-patient rehabilitation with significant improvement in physical function with mobility improving to be able to walk with a four-wheel walker. Cognitive and executive function has continued to slowly improve, though no formal neuropsychological testing has been repeated. He was discharged from hospital into a supported living facility, where he lives mostly independently, with on-site carers available if required. Karnofsky performance scale score at 18 months from commencing acalabrutinib was 65.

His ongoing treatment has been re-discussed in the lymphoma MDT with consensus that despite improvement in physical and cognitive function, an autologous stem cell transplant may be too high-risk with uncertain evidence for treatment consolidation with ASCT now he is over 12 months since induction therapy. Given he maintains remission taking acalabrutinib with no toxicity, and in the absence of evidence supporting cessation of acalabrutinib in this setting, the risk of relapse upon discontinuation remains a significant concern. The ongoing use of acalabrutinib will be re-discussed in relation to the patient’s progress moving forward and as further evidence of BTKi use in this setting continues to emerge.

3. Outline of CNS Lymphoma: Primary vs Secondary

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is an extra-nodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma occurring exclusively within the CNS including the brain parenchyma, leptomeninges, spinal cord, cranial nerves or eyes [

1]. The majority are histologically classified as diffuse large B cell (DLBCL) and are aggressive tumours with generally poor prognosis [

2]. PCNSL is rare and accounts for only 4-6% of all extra-nodal lymphomas with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years [

3].

According to the 2022 WHO classification of lymphoid malignancies, PCNSL sits under the umbrella of primary large B-cell lymphomas of immune privileged sites since they share common biological, immunophenotypic and molecular features with lymphomas arising in immune sanctuary sites such as testicular and vitreoretinal lymphoma [

2]. A subset of PCNSL are associated with immunosuppression and/or HIV infection, the majority of which are positive for lymphotropic Epstein Barr Virus (EBV). These EBV-associated PCNSL are clinically, biologically and molecularly distinct from those arising de-novo [

1] and as such, treatment paradigms diverge significantly.

Distinct from PCNSL is secondary central nervous system lymphoma (SCNSL) which spreads to the CNS concurrently with systemic disease or CNS relapse during or after frontline treatment [

4]. Incidence of CNS involvement at diagnosis and incidence of CNS relapse varies depending on histologic type of lymphoma. Whilst 20% of those with Burkitt Lymphoma have CNS involvement at diagnosis, the majority of SCNSL cases are DLBCL, usually presenting at first relapse. [

4].

The clinical symptoms of PCNSL are dictated by the location of lesions. 65% of patients have a solitary lesion [

1]. Parenchymal involvement is present in most cases and classically presents with focal neurological deficits such as weakness, sensory change, visual disturbance, neuropsychiatric and behavioural changes, and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure such as headache or seizures [

1]. Isolated leptomeningeal or spinal cord disease is rare and symptoms typically overlap with that of parenchymal disease. Vitreoretinal lymphoma (VRL) usually occurs concomitant to parenchymal lesions and may be present even in the absence of visual disturbance [

1]. B-symptoms such as night sweats, weight loss and fever are rare.

Time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis is typically rapid after development of sudden focal neurologic symptoms but may be delayed in those presenting with insidious neurological decline. The gold standard for diagnostic imaging is gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain and spinal cord demonstrating T2 hypointense lesions, with surrounding vasogenic oedema and homogeneous diffuse contrast enhancement. Stereotactic biopsy of a lesion is highly desirable to confirm the diagnosis[

3,

5]. Those with isolated vitreo-retinal involvement should undergo vitrectomy. If it is safe, a diagnostic lumbar puncture should be performed, which may help with diagnosis if tissue is not available. CSF investigations often demonstrate elevated protein levels, reflecting a disrupted blood brain barrier, normal glucose and elevated lymphocyte count which may show clonality by flow cytometric lymphoid immunophenotyping. Raised CSF protein is a feature of poorer prognosis. FDG-PET scan is performed to complete conventional lymphoma staging and rule out systemic lymphoma. Additional investigations with bone marrow biopsy and testicular ultrasound should always be considered to exclude lymphoma involvement.

Treatment selection must involve an evaluation of medical comorbidities and functional status. Age and performance status are major predictors of outcome and will dictate the appropriate tolerable therapeutic options [

6,

7]. There are many tools to assist functional assessment including the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) and the comparatively shorter G8. Though widely advocated, holistic and comprehensive geriatric assessments are cumbersome and time-consuming to complete, translating to poor adherence in practice [

7]. Knowledge of function immediately prior to onset of neurological symptoms is important, as more intensive therapy regimens may be avoided if patients are thought to be too frail or whose ECOG is high, unless this is disease related and pre-morbid baseline function was good. Function and ECOG may improve with commencement of treatment. Dynamic decisions need to be made based on changes in function, ECOG and mentation. It is important to embed functional assessment into clinical practice for patients with CNS lymphoma and include repeat assessments over the course of therapy, at completion and into remission.

4. Molecular Characterisation:

Considerable advances in understanding the unique biology of PCNSL have been made in recent years. Tumour cells are invariably positive for CD20, CD79a and PAX5, and the vast majority are activated B-cell (ABC) subtype (by cell of origin), being CD10 negative, BCL6 and MUM1 positive [

1,

8]. The pathogenesis of PCNSL lies in the dysregulation of key cell signalling pathways that ultimately lead to NF-kB activation and B-cell proliferation and survival [

9]. There are typical recurrent mutations primarily affecting MYD88

L265P and CD79B, placing PCNSL in alignment with the MCD (

MYD88/

CD79B-mutated) lymphoma molecular subtype of DLBCL which is also characterized by poor prognosis and extra-nodal involvement, especially in immune-privileged sites [

4,

9]. Of significance, lymphoproliferative disorders with variants in these genes detected have been proven to be highly sensitive to the use of BTK inhibition [

10].

Genetic inactivation of MHC class I and II, and β 2-microglobulin, with subsequent loss of protein expression, together with a 9p24 gain, result in overexpression of PD-L1/2 in 30-50% of cases, enabling immune escape [

2,

9,

11,

12]. There are currently no established subtypes of PCNLS, but when taken altogether there is significant heterogeneity in the molecular signature. However, when grouped with respect to genomic characteristics (whole-exome sequencing, RNA-seq, copy number alterations, DNA methylation) and clinicoradiological data, there may emerge certain clusters with prognostic significance [

13]. Further research is required to validate these potential subtypes and translate them for clinical use.

5. Non-Invasive Diagnostics and Monitoring

While stereotactic brain biopsy is the diagnostic gold standard, this can be difficult to achieve safely given lesions are sometimes in anatomically challenging and high-risk locations. If a patient is commenced on corticosteroids prior to biopsy, this may obscure histological diagnosis by causing necrosis of the tumour. Traditional methods of CSF evaluation with cytology is often only positive in cases involving the leptomeninges or parts of the brain with intraventricular extension [

14]. Therefore, there remains a need to develop non-invasive techniques to diagnose PCNSL, that could either complement or, in certain circumstances, replace the need for a brain biopsy.

Identification of the MYD88

L265P mutation and elevated levels of IL-10 (>2pg/mL) in CSF or vitreous fluid may be diagnostic for those unfit to undergo a brain biopsy, particularly where samples are pauci-particulate [

9,

15,

16]. Elevated IL-10 at diagnosis has been show to correlate with worse overall survival, and persistent elevation at end of treatment may predict rapid relapse [

16]. Other proposed biomarkers include CSF CXCL13 (a B lymphocyte chemo-attractant that binds to the CXCR5 receptor) and neopterin (a nonspecific marker of the type 1 T-helper cell–related cellular immune response) which have showed sensitivity in the diagnosis of cerebral lymphoma. However, they lack specificity and may not differentiate PCNSL from SCNLS [

16]. Extrapolating from their emerging utility in other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, soluble CD19, soluble CD27, and immunoglobulin free light chains may also have merit in contributing to an overall diagnostic picture, but require further research [

16].

Use of cell free DNA (cfDNA) and the proportion of tumour-derived cfDNA (ctDNA) represents further opportunities for the non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring of malignancies. Targeted sequencing of ctDNA using a variety of highly sensitive methods including quantitative PCR, TaqMan PCR, next generation sequencing and digital droplet PCR, can identify somatic mutations and gene alterations that can then serve as a molecular marker of disease status [

16,

17]. The particular challenge of PCNSL lies in the relatively intact blood-brain barrier that limits the release of ctDNA into the bloodstream, but relatively concentrates it in the CSF. In a small study of 6 cases of CNS restricted lymphoma, detection of MYD88

L265P mutation in CSF ctDNA was more sensitive at detecting disease than traditional methods, predicting relapse even while CSF flow cytometry and cytology remained negative [

18]. Moreover, as a consequence of disease and treatment, the blood brain barrier in PCNSL is impaired allowing detection of ctDNA in the plasma and urine, though at reduced rates compared with CSF [

18,

19,

20,

21]. CtDNA could also serve as a biomarker for risk stratification and predicting outcome, as concentrations correlate with total radiographic tumour volumes measured by MRI, and higher ctDNA concentrations in any fluid at the time of diagnosis, and its persistence during treatment, correlates to poorer prognosis [

22,

23].

Response to treatment is currently based on serial MRI monitoring. However, there can sometimes be difficulty differentiating active disease from disease-free but damaged tissue, when assessing for small volumes of residual tumour. Identifying the molecular signature at diagnosis and subsequent measurement of ctDNA may represent further opportunities for accurate monitoring of response to treatment and detection of molecular relapse even in radiologic remission (or if there is uncertainty based on nonspecific image findings) [

18]. As in other lymphomas, further studies and validation are required before its translation into risk stratification and clinical management.

Identifying PCNSL as being of the MCD subtype, either by identifying a MYD88L265P mutation or variant of CD79B, may have potentially therapeutic implications, as tumours of this subtype are sensitive to treatment using BTK inhibitors.

6. Treatment Evolution

6.1. Induction

Historically, corticosteroids and whole-brain radiotherapy was the only treatment available for PCNSL. This translated to dismal survival outcomes with overall 5 year survival <5% [

24]. The introduction of high dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) at doses achieving cytotoxic CSF concentrations (>3 g/m

2) [

25], followed by the addition of high-dose cytarabine, improved outcomes [

26]. The addition of rituximab, the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, to chemotherapy combinations, further improved outcomes[

27]. The landmark IELSG32 trial [

28] proved the intensive 4-drug combination induction therapy with MATRix (HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa and rituximab) performed superiorly to 2-drug (HD-MTX/cytarabine) or 3-drug (rituximab/HD-MTX/Cytarabine[

28]) combinations. 7-year follow up demonstrated overall survival of 56%, rising to 70% for those who had MATRix followed by consolidation [

29]. A real world, multicentre retrospective analysis of 156 patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL treated with MATRix, recapitulated these findings, reporting a two year progression-free survival (PFS) of 56% and overall survival (OS) of 64.1% [

30]. The role of routine intrathecal chemotherapy has not been established and is not recommended [

3]. In patients deemed ineligible for high dose methotrexate treatment, but suitable for treatment with palliative intent, oral temozolomide and/or whole-brain radiotherapy and/or best supportive care remain options [

31,

32].

6.2. Consolidation

For fit patients who do not progress (i.e. in CR or PR) while on induction therapy, standard of care remains thiotepa-based high-dose conditioning chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). If a patient is not considered eligible for transplant, whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) can be considered. However, this comes with clinically significant toxicities, including impairment in attention, executive function and memory [

33]. A comparison of outcomes between WBRT and ASCT has been assessed in 2 randomised studies with Houllier et al [

34] demonstrating poorer long term survival in the WBRT group, but Ferreri et al [

35] suggested equipoise. Other options for those not eligible for transplant include maintenance with alkylating agent such as temozolamide or procarbazine.

6.3. Relapsed/Refractory Disease

Up to 25% of patients treated with best available therapy experience refractory disease and a further 25% of patients experience relapse after initial response. The outcomes for these patients are extremely poor [

3]. Salvage options include HD-cytarabine or HD-ifosfamide-based chemotherapy followed by consolidative ASCT. Where available, patients should be enrolled in clinical trials.

6.4. Treatment in the Elderly and Frail

Since its publication in 2016 [

28], MATRix has been adopted as first-line therapy for fit patients under the age of 70. However, with the median age of presentation in the seventh decade [

6], it is common for patients to need dose or treatment modification. The diagnosis in elderly patients is more likely to be delayed because subtle symptoms or mild cognitive decline are dismissed as age related changes [

33] or can be attributed to other health issues. This not only corresponds to poorer baseline functional status at diagnosis but delayed diagnosis is an independent predictor of inferior survival [

33].

There is strong evidence that outcomes are linked to the dose of methotrexate, with those treated with lower doses having considerably worse outcomes [

30]. An analysis of outcomes in elderly patients treated with methotrexate-based regimens found that the higher relative intensity of methotrexate dosing received resulted in better outcomes [

36]. Options for lower intensity therapy include the R-MP protocol (rituximab, high-dose methotrexate and procarbazine induction, followed by 4 weekly maintenance treatment with procarbazine) which demonstrated a 2-year progression-free survival of 34.9% in the PRIMAIN study [

37].

Treatment challenges in the elderly relate to balancing toxicity while maximising chemotherapy dose to ensure cytotoxic concentrations in the CNS. Issues include intolerance to the large volume of adjunct bicarbonate fluids required to facilitate renal excretion of high-dose methotrexate resulting in fluid overload and potentiating heart failure. Conversely, poorer baseline renal function makes patients more vulnerable to renal toxicity. Elderly patients are more vulnerable to the side effects of glucocorticoids including cognitive and behavioural disturbance as well as hyperglycaemia [

33]. In a retrospective review of 192 elderly patients (aged over 65 years) treated with a methotrexate-based regimen, treatment-related mortality was 6.8% which, while comparable to the 6% IELSG32 trial, around one-third of patients had significant dose modifications [

36].

While treatment for CNS lymphoma can be challenging, and the outcomes suboptimal, recent trials may provide more tolerable therapy with the hope of better outcomes. The single arm, phase 2 MARTA trial took 51 patients, 53% of whom had an ECOG of 2 or more, and a median age of 71 years, and administered a modified MATRix regimen by omitting thiotepa during a shortened induction followed by a modified busulfan and thiotepa conditioning for ASCT. While it did not meet its primary efficacy endpoint, it demonstrated a 1 year overall survival of 80.6% in those completing treatment which is comparable to younger cohorts [

38]. This challenges the traditional wisdom of avoiding transplant in older patients by minimising upfront toxicity and may serve as a backbone for future research. Furthermore, current research is underway investigating the efficacy of emerging therapies.

6.5. Emerging Novel Therapies

Given both the limitations and toxicities of current therapies, particularly in the elderly and in relapse, there has been much interest in novel therapies that may complement or even replace conventional chemotherapy. Among the most promising and well-studied therapies are the BTKis. However, there are a number of other clinical developments including immune-modulators such as lenalidomide, immune checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (CAR-T).

6.6. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase, B Cell Activation and BTK Inhibitors

Following antigen binding to the extracellular motif of the B cell receptor, a chain reaction of intracellular signalling commences including phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based active motifs, recruitment of SYK tyrosine kinase, phosphorylation of BLNK adaptor protein, which then recruits and activates BTK. BTK is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase, which when phosphorylated following this initial chain reaction, goes on to downstream activation of phospholipase Cy2 and subsequently inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol. These are both important second messengers in NF-kB transcription factor up-regulation leading to B cell proliferation, differentiation and antibody production [

39]. Small molecules that target and inhibit BTK and hence downstream B cell activation and proliferation have emerged as being highly effective to treat B cell malignancy and autoimmune diseases driven by dysfunction in B cells [

10,

40].

It has been recognised that variants in MYD88 and CD79B can predict sensitivity to BTK inhibition in B cell lymphoproliferative disorders [

41]. MYD88 is an adaptor protein that can be activated downstream of Toll-like receptors and IL1R family members, which activates B cells and play an important part in innate immunity. Variants in MYD88, particularly the hot spot L265P variant, are commonly found in B cell lymphoproliferative diseases, and thought to constitutively active NF-kB and hence B cell activation [

42]. CD79B is a subunit of the B cell receptor, forming a heterodimer with CD79A and is crucial for B cell activation. Mutations in CD79B are known to lead to constitutive B cell activation via activation of SYK, BTK, Pi3K and eventually NF-kB, and hence lymphoma development through uncontrolled B cell proliferation and survival [

43]. BTK is a common kinase to both MYD88 and CD79B activation pathways, therefore in lymphomas that are driven by constitutive activation of B cell survival, it can be exploited by using inhibitors to prevent unregulated B cell growth [

41].

BTK inhibitors are well established as treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, mantle cell lymphoma and Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia. Subsequently, interest has turned toward use in other types of lymphoproliferative disease. BTK inhibitors can penetrate the blood brain barrier and block the chronic B cell receptor signally that is occurring in PCNSL, which frequently have mutations of MYD88 and/or CD79B, therefore inducing apoptosis of these lymphoma cells. There is a rational place for BTK inhibition in PCNSL [

44,

45].

Ibrutinib was the first-in-class covalent BTK inhibitor, binding to Cys-481, the active site of BTK. It has less specificity to BTK compared with later generations, demonstrating binding of cysteine residues in other kinases including epidermal growth factor receptor family kinases, SRC kinases and TEC-kinases. These off-target binding may cause side effects such as diarrhoea, dermatitis, atrial fibrillation, hypertension and increased bleeding risk. Second generation BTKis include acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, tirabrutinib, and orelabrutinib. They exhibit higher target specificity than ibrutinib but still cause some noteworthy adverse effects including headache and cough with acalabrutinib and neutropenia with zanubrutinib [

10].

BTKis are small molecules and have been proven to cross the intact blood brain barrier with ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanabruitinb and tirabrutinib detectable in the CSF at concentrations associated with anti-tumour activity between 2-24 hours after oral dose [

46,

47,

48]. In animal models, ibrutinib and tirabrutinib have demonstrated higher and more sustained CSF concentrations than zanabrutinib [

49]. However, this has been refuted in humans following a case series of 13 patients with CNS involvement of DLBCL which reported excellent BBB penetration of zanubrutinib [

50]. Furthermore, rodent models of gliomas demonstrates that ibrutinib may also increase BBB permeability by causing junctional disruption and impairing efflux ports [

51]. This enables increased concentrations of chemotherapies at the tumour site while limiting systemic toxicity, lending strength to use of BKIs as upfront, adjunct therapy.

There have been 2 prospective studies evaluating ibrutinib monotherapy. In 2017, there was a phase 1/2 study of ibrutinib monotherapy in 13 patients with R/R PCNSL achieving a response rate of 77% and a complete response rate of 38% [

52]. Recent publication by the same group with additional patient enrolment and 3 year follow up showed there was response in 23/31 patients with PCNSL with median PFS of 4.5 months (95%CI: 2.8-9.2) and 1year PFS of 23.7% (95%CI: 12.4%-45.1%) [

53]. The iLOC study was a phase 2 study of 44 patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell primary oculo-cerebral lymphoma treated with ibrutinib monotherapy [

54] . Short-term overall response rate after 2 months of treatment was 59% including 10 complete responses (19%). Longer term follow up (median 66 months) showed a median overall survival of 20 months (IQR: 7-29months) and PFS of 4.8 months (IQR: 3–13 months) [

55].

Ibrutinib has also been studied in combination with chemoimmunotherapy (DA-TEDDi-R) (rituximab, liposomal doxorubicin, temozolomide, etoposide and dexamethasone). In 14 evaluable patients (median age 66 years of an initial cohort of 18 patients) with R/R PCNSL, ORR was 91% with 86% achieving CR/CRu. Of these, 57% had PFS at a median of 15.5 months of follow up (range 8-27 months). Median PFS was calculated at 15.3 months. With limited follow up at time of reporting, median OS was not reached with 51.3% alive at 1 year. Increased aspergillus infection was noted in this study [

45].

Tirabrutinib is approved for use for R/R PCNSL in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Three year follow up of 44 patients with R/R PCNSL treated with tirabrutinib monotherapy demonstrated an overall response rate of 63.6% (95% CI: 47.8–77.6) and median overall survival not reached [

56,

57]. The PROSPECT study (NCT04947319) have just presented their phase 2 data using tirabrutinib monotherapy in R/R PCNSL. 48 patients (median age 65.6 years) with median follow up 11.2 months showed ORR 66.7% with CR/CRu of 43.8%. Median DOR was 9.3 months. TRAEs of 3 or greater were experienced in 27.1% [

58].

Zanubrutinib has been used in combination with immunochemotherapy, with a case report of good response from the addition of zanubrutinib to HD-MTX and rituximab which had been refractory after 2 cycles, allowing the patient to proceed to ASCT, with survival at least 11 months after diagnosis [

59]. In a retrospective analysis of the up-front use of BTKi in newly diagnosed PCNSL, 19 patients (median age 57) were treated with zanubrutinib and HD-MTX. The median follow-up duration was 14.7 months with an ORR of 84.2%, and OS rates 94.1% [

60]. ctDNA was assessed in CSF throughout treatment and correlated with radiologic response and predicted progressive disease while on maintenance treatment. The selection criteria for the use of zanubrutinib was not clear. Although a small study, this robust survival rate merits further investigation with prospective study. The PRiZM+ study (ISRCTN90634455) have just presented their phase 2 data using zanubrutinib monotherapy in R/R PCNSL. Of 20 evaluable patients (median age 64 years), ORR was 55% and CR/CRu was 35% determined by central neuroradiological review. With median follow up of 19 months, median PFS was 53% and OS was 37%. 10 SAEs were reported [

61].

Acalabrutinib is a second generation BTKi currently being prospectively evaluated in clinical trials investigating the efficacy in R/R PCNSL as monotherapy (NCT04548648, NCT04906902) or in combination with the PD-1 inhibitor durvalumab (NCT04462328) and are ongoing. The latter trial reported phase 1 data on 10 patients (median 2 prior lines of therapy) with a 40% CR/CRu. Importantly, this communication had a correlative science arm testing ACP-196 (acalabrutinib) and ACP-5862 (the active metabolite of acalabrutinib) levels in plasma and CSF. ACP-196 was detected in CSF with median concentration 4.6ng/dl (range 2.75-10.6ng/dl) and ACP-5862 had median concentration of 7.06 ng/dl, indicating penetrance of acalabrutinib and its active metabolite into patients’ CSF [

62]. Though no case reports have yet been published for the use of acalabrutinib monotherapy in PCNSL, there are reports of its effective use in combination with immunochemotherapy and radiotherapy for EBV-positive post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease follow allogeneic stem cell transplant treating acute myeloid leukaemia [

63]; monotherapy leading to CR of mantle cell lymphoma with CNS involvement [

64]; and durable remission with acalabrutinib monotherapy in a patient with leptomeningeal disease secondary to relapsed mantle cell lymphoma [

65].

A retrospective review of 82 patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL treated across 3 Chinese hospitals found that the 26 patients who received BTKi combined with chemotherapy resulted in statistically significantly improved outcomes compared with 49 patients who had chemotherapy alone. At median follow up of 28 months, the median overall survival of the BTKi group was not reached, compared with the chemotherapy group at 47.8 months (IQR: 32.5–63.1 months) (p = 0.038) [

66]. Notwithstanding the limitations of the retrospective, uncontrolled nature of this review, it adds strength to the use of upfront BTKis.

Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of BTKis in all types of CNS lymphoma (primary and secondary) included 21 studies involving 368 patients [

67]. There were 7 studies (35 patients) that used BTKis in the upfront setting. However, due to the small sample size, no pooled analysis was undertaken. In the R/R setting, 10 studies (166 patients) using monotherapy showed a pooled overall response rate of 60% (95% CI: 50–71%) and in 12 studies (176 patients) using combination therapy pooled, ORR was 78% (95% CI: 68–86%). With regard to the significance of MYD88 or CD79B mutational status, a review found that the effect of BTK inhibitors was independent of MYD88 or CD79B mutational status [

68].

As the molecular landscape of PNCSL is further elucidated, there is a growing understanding of their effect on the variable response to BTKi. Mutations in caspase recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11) is found in 11-30% of PCNSL and can promote resistance to single agent ibrutinib [

69]. CD79B mutations may upregulate PI3K/mTOR signalling to convey resistance [

70]. Comprehensive genomic profiling is increasingly being used to identify biomarkers that may be predictive of immunotherapy efficacy. However, findings have been conflicting with some proposing that high tumour mutational burden is predictive of good response to immunotherapy [

71]; whereas others find patients with complex genomic features respond poorly to ibrutinib [

72].

6.7. Other Therapies

CAR-T therapy is an established treatment in relapsed and refractory DLBCL. CAR-T cell therapy is associated with immune effector associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). ICANS symptoms range from the mild: headache, fatigue and reversible aphasia; through to severe and life-threatening symptoms: seizures, cerebral oedema, and death. Patients with CNS involvement were excluded from the registration trials due to concerns for potential excess toxicity, owing to the primary site of the lesion, the disrupted blood brain barrier and the heavy burden of pre-treatment with CNS side effects such as whole-brain radiotherapy[

73]. CAR-T have been shown to cross the blood brain barrier and can be detected at therapeutic levels for over 6 months post-infusion[

44]. A 2022 meta-analysis of the toxicity and efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in 128 patients with relapsed or refractory primary (30) and secondary (98) CNS lymphoma, showed no increase in neurotoxicity when compared to that which was observed in the registration studies for DLBCL[

74]. In addition, there was encouraging efficacy in PCNSL with 56% achieving a complete remission, with 37% remaining in remission at 6 months.

Glofitamab, a CD20xCD3 bispecific antibody, has been shown to cross the blood brain barrier and has shown efficacy in 4 patients with R/R DLBCL with secondary CNS involvement[

75].

Pembrolizumab and nivolumab, both anti-PD1 antibodies, have demonstrated impressive results in case reports or small retrospective studies of patients with R/R PCNSL, but there are no prospective studies available[

76,

77,

78,

79,

80].

7. Discussion

PCNSL is a devastating disease with significant morbidity and mortality. Its impact is pronounced because it significantly compromises function, and although there have been advances in treatment, the blood brain barrier compromises treatment penetration. Also, the tolerability of intensive treatment in patients with functional impairment is limited.

Our case demonstrates how a relatively young patient was unable to tolerate the toxicity of intensive therapy and was considered unsuitable for consolidative autologous stem cell transplant or whole-brain radiotherapy. There are a considerable number of patients, either due to age, co-morbdities or toxicity from induction therapy, who are unsuitable to receive consolidative therapy following intensive induction therapy. Progression-free and overall survival are known to be compromised in those who do not receive both intensive induction and consolidative therapy.

This case demonstrates that acalabrutinib, the BTKi inhibitor, was able to be used with no toxicity, with the patient remaining in remission for 18 months on this monotherapy. This facilitated recovery from the toxicities associated with intensive induction therapy, with subsequent improvement of both physical and cognitive function. It is unknown whether this patient would have remained in remission without acalabrutinib, though given initial induction therapy was truncated and that no standard consolidation was given, it would have been very unlikely for this patient to have remained in remission without additional therapy. Furthermore, it is unclear whether it is now safe to stop the acalabrutinib without risk of disease relapse.

The data presented in this review shows that acalabrutinib and the other discussed BTKis have evidence for crossing the blood brain barrier and have shown promise in the refractory and relapsed disease setting, for use as monotherapy or in combination with other therapies, to improve outcomes. Certainly, using BTKis in PCNSL, which is largely of the MCD subtype (confirmed by MYD88 and/or CD79B molecular testing) is a rational drug choice, given the MCD subtype is highly sensitive to BTK inhibition although some studies suggest that BTKi benefit may be agnostic to MCD variants.

Whether BTKi can be used for those patients unable to have standard consolidation either due to age, functional status or due to toxicity from initial therapy, or whether it might be used for maintenance, is a tantalising question that should be answered by clinical trials. Certainly, use for the patient in our case report has been favourable without toxicity. If shown to be effective in the clinical trial setting, further research is required regarding duration of therapy: whether fixed duration will be sufficient; or if continuous therapy is necessary. Also, the importance of testing for the molecular variants of MYD88 and CD79B from CSF and brain biopsy tissue should be incorporated into clinical trial design of those trials using BTKi, to assess if these markers can enable more personalised therapy for patients to be determined, or whether therapeutic effect is agnostic to the presence of these variants. The use of these molecular markers by ctDNA may also be used to guide duration of therapy or predict those about to relapse, where early intervention may be of benefit.

8. Conclusions

There have been significant advances in the treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. However, there remains a need for additional therapies particularly for those patients who are unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy. BTKis seem to have a rational and promising role in this setting, and may provide less toxic consolidation or maintenance therapies, either as monotherapies or in combinations. Further research is needed.

Author Contributions

EMA and BB contributed to conception and design of work; EMA, AKC, AMW and BB provided acquisition and analysis of data of the case for reporting; EMA, AKC, AMW and BB were involved with drafting the work; EMA, AKC, AMW and BB approve and endorse this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement:.

Informed Consent Statement:.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Ferreri, A., et al., Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2023. 9.

- Alaggio, R., et al., The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia, 2022. 36(7): p. 1720-1748. [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.M., et al., Primary central nervous system lymphomas: EHA–ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. HemaSphere, 2024. 8(6): p. e89. [CrossRef]

- Alderuccio, J.P., L. Nayak, and K. Cwynarski, How I treat secondary CNS involvement by aggressive lymphomas. Blood, 2023. 142(21): p. 1771-1783.

- de Koning, M., et al., Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Journal of Neurology, 2023. 271(5): p. 2906-2913.

- Khwaja, J., L. Nayak, and K. Cwynarski, Evidence-based management of primary and secondary CNS lymphoma. Seminars in Hematology, 2023. 60(5): p. 313-321.

- Martinez-Calle, N., et al., Treatment of elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma. Annals of Lymphoma, 2021. 5. [CrossRef]

- Schaff, L.R. and C. Grommes, Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Blood, 2022. 140(9): p. 971-979.

- Mo, S.S., J. Cleveland, and J.L. Rubenstein, Primary CNS lymphoma: update on molecular pathogenesis and therapy. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 2023. 64(1): p. 57-65.

- Alu, A., et al., BTK inhibitors in the treatment of hematological malignancies and inflammatory diseases: mechanisms and clinical studies. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 2022. 15(1): p. 138. [CrossRef]

- Marie de, C. and H. Roch, Hide or defend, the two strategies of lymphoma immune evasion: potential implications for immunotherapy. Haematologica, 2018. 103(8): p. 1256-1268.

- Kline, J., J. Godfrey, and S.M. Ansell, The immune landscape and response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in lymphoma. Blood, 2020. 135(8): p. 523-533.

- Hernández-Verdin, I., et al., Primary central nervous system lymphoma: advances in its pathogenesis, molecular markers and targeted therapies. Current Opinion in Neurology, 2022. 35(6): p. 779-786.

- Tivey, A., et al., Circulating tumour DNA — looking beyond the blood. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2022. 19(9): p. 600-612. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., et al., Effectiveness of digital PCR for MYD88L265P detection in vitreous fluid for primary central nervous system lymphoma diagnosis. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 2020. 20(1): p. 301-308.

- Nguyen-Them, L., et al., CSF biomarkers in primary CNS lymphoma. Revue Neurologique, 2023. 179(3): p. 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Fontanilles, M., et al., Non-invasive detection of somatic mutations using next-generation sequencing in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(29): p. 48157.

- Bobillo, S., et al., Cell free circulating tumor DNA in cerebrospinal fluid detects and monitors central nervous system involvement of B-cell lymphomas. Haematologica, 2021. 106(2): p. 513.

- Huang, J. and C.D. Gocke, Circulating Tumor DNA in Lymphoma, in Precision Molecular Pathology of Aggressive B-Cell Lymphomas, G.M. Crane and S. Loghavi, Editors. 2023, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 395-426.

- Kambhampati, S. and J. Zain, Circulating Tumor DNA in Lymphoma. Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports, 2022. 17(6): p. 298-305.

- Watanabe, J., et al., Comparison of circulating tumor DNA between body fluids in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 2019. 60(14): p. 3587-3589. [CrossRef]

- Heger, J.-M., et al., Noninvasive, dynamic risk profiling of primary central nervous system lymphoma by peripheral blood ctdna-sequencing. Blood, 2022. 140(Supplement 1): p. 3537-3538. [CrossRef]

- Mutter, J.A., et al., Profiling of circulating tumor DNA for noninvasive disease detection, risk stratification, and MRD monitoring in patients with CNS lymphoma. Blood, 2021. 138(Supplement 1): p. 6-6.

- Khwaja, J. and K. Cwynarski, Management of primary and secondary CNS lymphoma. Hematological Oncology, 2023. 41(S1): p. 25-35. [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, S., et al., Rapid infusion of high-dose methotrexate resulting in enhanced penetration into cerebrospinal fluid and intensified tumor response in primary central nervous system lymphomas. Journal of neurosurgery, 1999. 91(2): p. 221-230.

- Ferreri, A.J., et al., High-dose cytarabine plus high-dose methotrexate versus high-dose methotrexate alone in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a randomised phase 2 trial. The Lancet, 2009. 374(9700): p. 1512-1520. [CrossRef]

- Ollila, T.A., et al., Immunochemotherapy or chemotherapy alone in primary central nervous system lymphoma: a National Cancer Database analysis. Blood Advances, 2023. 7(18): p. 5470-5479. [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J., et al., Chemoimmunotherapy with methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the first randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 (IELSG32) phase 2 trial. The Lancet Haematology, 2016. 3(5): p. e217-e227.

- Ferreri, A.J.M., et al., Long-term efficacy, safety and neurotolerability of MATRix regimen followed by autologous transplant in primary CNS lymphoma: 7-year results of the IELSG32 randomized trial. Leukemia, 2022. 36(7): p. 1870-1878. [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E., et al., Induction therapy with the MATRix regimen in patients with newly diagnosed primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system–an international study of feasibility and efficacy in routine clinical practice. British Journal of Haematology, 2020. 189(5): p. 879-887. [CrossRef]

- Batara, J.M.F., et al., Use of rituximab, temozolomide, and radiation in recurrent and refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma in the Philippines: a retrospective analysis. Neuro-Oncology Advances, 2022. 4(1): p. vdac105.

- Enting, R.H., et al., Salvage therapy for primary CNS lymphoma with a combination of rituximab and temozolomide. Neurology, 2004. 63(5): p. 901-903. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calle, N., et al., Advances in treatment of elderly primary central nervous system lymphoma. British Journal of Haematology, 2022. 196(3): p. 473-487.

- Houillier, C., et al., Radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation for primary CNS lymphoma in patients age 60 years and younger: long-term results of the randomized phase II PRECIS study. Journal of clinical oncology, 2022. 40(32): p. 3692-3698.

- Ferreri, A.J., et al., Whole-brain radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation as consolidation strategies after high-dose methotrexate-based chemoimmunotherapy in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the second randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 phase 2 trial. The Lancet Haematology, 2017. 4(11): p. e510-e523. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calle, N., et al., Outcomes of older patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma treated in routine clinical practice in the UK: methotrexate dose intensity correlates with response and survival. British journal of haematology, 2020. 190(3): p. 394-404.

- Fritsch, K., et al., High-dose methotrexate-based immuno-chemotherapy for elderly primary CNS lymphoma patients (PRIMAIN study). Leukemia, 2017. 31(4): p. 846-852.

- Schorb, E., et al., High-dose chemotherapy and autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in older, fit patients with primary diffuse large B-cell CNS lymphoma (MARTA): a single-arm, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Haematology, 2024. 11(3): p. e196-e205.

- Satterthwaite1, A.B. and Witte1, Owen N, The role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B-cell development and function: a genetic perspective. Immunological reviews, 2000. 175(1): p. 120-127.

- Neys, S.F., R.W. Hendriks, and O.B. Corneth, Targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in inflammatory and autoimmune pathologies. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 2021. 9: p. 668131.

- Visco, C., et al., Oncogenic mutations of MYD88 and CD79B in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and implications for clinical practice. Cancers, 2020. 12(10): p. 2913.

- de Groen, R.A., et al., MYD88 in the driver’s seat of B-cell lymphomagenesis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical implications. haematologica, 2019. 104(12): p. 2337.

- Flümann, R., et al., An inducible Cd79b mutation confers ibrutinib sensitivity in mouse models of Myd88-driven diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Advances, 2024. 8(5): p. 1063-1074.

- Grupp, S.A., et al., Chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2013. 368(16): p. 1509-1518.

- Lionakis, M.S., et al., Inhibition of B cell receptor signaling by ibrutinib in primary CNS lymphoma. Cancer cell, 2017. 31(6): p. 833-843. e5.

- Schaff, L., L. Nayak, and C. Grommes, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors for the treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL): current progress and latest advances. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 2024: p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Goldwirt, L., et al., Ibrutinib brain distribution: a preclinical study. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, 2018. 81(4): p. 783-789.

- Bernard, S., et al., Activity of ibrutinib in mantle cell lymphoma patients with central nervous system relapse. Blood, 2015. 126(14): p. 1695-1698. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., et al., Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors in primary central nervous system lymphoma-evaluation of anti-tumor efficacy and brain distribution. Transl Cancer Res, 2021. 10(5): p. 1975-1983.

- Zhang, Y., et al., Preliminary Evaluation of Zanubrutinib-Containing Regimens in DLBCL and the Cerebrospinal Fluid Distribution of Zanubrutinib: A 13-Case Series. Frontiers in Oncology, 2021. 11: p. undefined-undefined.

- Lim, S., et al., Ibrutinib disrupts blood-tumor barrier integrity and prolongs survival in rodent glioma model. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2024. 12(1): p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Grommes, C., et al., Ibrutinib unmasks critical role of Bruton tyrosine kinase in primary CNS lymphoma. Cancer discovery, 2017. 7(9): p. 1018-1029.

- Grommes, C., et al., A Phase II study assessing Long-Term Response to Ibrutinib Monotherapy in recurrent or refractory CNS Lymphoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Soussain, C., et al., Ibrutinib monotherapy for relapse or refractory primary CNS lymphoma and primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: Final analysis of the phase II ‘proof-of-concept’ iLOC study by the Lymphoma study association (LYSA) and the French oculo-cerebral lymphoma (LOC) network. European Journal of Cancer, 2019. 117: p. 121-130.

- Soussain, C., et al., Long-lasting CRs after ibrutinib monotherapy for relapse or refractory primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) and primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL): Long-term results of the iLOC study by the Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) and the French Oculo-Cerebral Lymphoma (LOC) Network (clinical trial number: NCT02542514). European Journal of Cancer, 2023. 189: p. 112909.

- Yonezawa, H., et al., Three-year follow-up analysis of phase 1/2 study on tirabrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neuro-Oncology Advances, 2024. 6(1): p. vdae037. [CrossRef]

- Narita, Y., et al., Phase I/II study of tirabrutinib, a second-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neuro-oncology, 2021. 23(1): p. 122-133. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, L., et al., Tirabrutinib for the treatment of relapsed or refractory primary central nervous system lymphoma: Efficacy and safety from the phase II PROSPECT study. 2025, American Society of Clinical Oncology.

- Cheng, Q., et al., Successful Management of a Patient with Refractory Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma by Zanubrutinib. Onco Targets Ther, 2021. 14: p. 3367-3372.

- Wang, N., et al., Clinical outcomes of newly diagnosed primary central nervous system lymphoma treated with zanubrutinib-based combination therapy. World Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2023. 14(12): p. 606.

- Fox, C., et al., THE PRiZM+ PHASE II PLATFORM STUDY FOR RELAPSED AND REFRACTORY PRIMARY CNS LYMPHOMA: FIRST RESULTS FROM COHORT 1 ZANUBRUTINIB MONOTHERAPY. Hematological Oncology, 2025. 43: p. e87_70093. [CrossRef]

- Nizamuddin, I.A., et al., Phase I Results of Acalabrutinib in Combination with Durvalumab in Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma: Safety, Efficacy, and Central Nervous System Penetration. Blood, 2024. 144: p. 985.

- Zheng, P., et al., Central nervous system posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation successfully treated with combination therapy of acalabrutinib and immunochemotherapy: A case report and literature review. EJHaem, 2025. 6(1): p. e1078.

- Barrett, A., et al., Complete response of mantle cell lymphoma with central nervous system involvement at diagnosis with acalabrutinib–Case report. EJHaem, 2024. 5(1): p. 238-241. [CrossRef]

- Yohannan, B., et al., Durable remission with Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in a patient with leptomeningeal disease secondary to relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. BMJ Case Reports CP, 2022. 15(6): p. e249631. [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.-J., et al., Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with newly diagnosed primary central nervous system lymphoma: a multicentre retrospective analysis. Annals of Hematology, 2024: p. 1-12.

- Zhang, Y., et al., Efficacy and Safety of BTKis in Central Nervous System Lymphoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel), 2024. 16(5).

- Lv, L., et al., Efficacy and Safety of Ibrutinib in Central Nervous System Lymphoma: A PRISMA-Compliant Single-Arm Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Oncology, 2021. 11: p. undefined-undefined.

- Shen, J. and J. Liu, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma: A mini-review. Frontiers in oncology, 2022. 12: p. 1034668. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q., et al., Frequent gene mutations and their possible roles in the pathogenesis, treatment and prognosis of primary central nervous system lymphoma. World Neurosurgery, 2023. 170: p. 99-106.

- Severson, E.A., et al., Genomic profiling reveals differences in primary central nervous system lymphoma and large B-cell lymphoma, with subtyping suggesting sensitivity to BTK inhibition. The Oncologist, 2023. 28(1): p. e26-e35. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., The outcome of ibrutinib-based regimens in relapsed/refractory central nervous system lymphoma and the potential impact of genomic variants. Advances in Clinical & Experimental Medicine, 2023. 32(8).

- Karschnia, P., et al., CAR T-cells for CNS lymphoma: driving into new terrain? Cancers, 2021. 13(10): p. 2503.

- Cook, M.R., et al., Toxicity and efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in primary and secondary CNS lymphoma: a meta-analysis of 128 patients. Blood Advances, 2023. 7(1): p. 32-39.

- Godfrey, J.K., et al., Glofitamab stimulates immune cell infiltration of CNS tumors and induces clinical responses in secondary CNS lymphoma. Blood, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Furuse, M., et al., Immunotherapy of nivolumab with dendritic cell vaccination is effective against intractable recurrent primary central nervous system lymphoma: a case report. Neurologia medico-chirurgica, 2017. 57(4): p. 191-197.

- Nayak, L., et al., PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system and testicular lymphoma. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 2017. 129(23): p. 3071-3073. [CrossRef]

- Graber, J.J., et al., Pembrolizumab immunotherapy for relapsed CNS Lymphoma. Leukemia & lymphoma, 2020. 61(7): p. 1766-1768. [CrossRef]

- Ambady, P., et al., Combination immunotherapy as a non-chemotherapy alternative for refractory or recurrent CNS lymphoma. Leukemia & lymphoma, 2019. 60(2): p. 515-518.

- Gavrilenko, A.N., et al., Nivolumab in primary CNS lymphoma and primary testicular lymphoma with CNS involvement: single center experience. Blood, 2020. 136: p. 4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).